Abstract

The difluoromethyl group is a crucial fluorinated moiety with distinctive biological properties, and the synthesis of chiral CF₂H-containing analogs has been recognized as a powerful strategy in drug design. To date, the most established method for accessing enantioenriched difluoromethyl compounds involves the enantioselective functionalization of nucleophilic and electrophilic CF₂H synthons. However, this approach is limited by lower reactivity and reduced enantioselectivity. Leveraging the unique fluorine effect, we design and synthesize a radical CF₂H synthon by incorporating isoindolinone into alkyl halides for asymmetric radical transformation. Here, we report an efficient strategy for the asymmetric construction of carbon stereocenters featuring a difluoromethyl group via nickel-catalyzed Negishi cross-coupling. This approach demonstrates mild reaction conditions and excellent enantioselectivity. Given that optically pure difluoromethylated amines and isoindolinones are key structural motifs in bioactive compounds, this strategy offers a practical solution for the efficient synthesis of CF₂H-containing chiral drug-like molecules.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

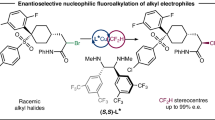

Organofluorine chemistry has emerged as a highly significant field over the past few decades, enabling the on-demand synthesis of a wide range of unnatural fluorinated molecules, which has garnered considerable research interest, particularly in pharmaceuticals, agrochemicals, and specialized materials1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12. Standing out as one of the most significant fluorinated moieties due to its unique biological properties, the difluoromethyl group (CF₂H) has been recognized as an excellent bioisostere for hydroxyl, thiol, or amide groups, and as a lipophilic hydrogen-bond donor which could significantly enhance binding affinity, membrane permeability, and bioavailability while incorporated into parent molecules2,13, thus attracting increasing interest in drug design and screening. Indeed, several CF₂H-containing drugs and bioactive molecules have been developed14,15,16, including FDA-approved drugs and others in clinical trials (Fig. 1a). Given the inherent chiral nature of biological systems, drug chirality is widely recognized as a crucial aspect of medicinal research. Under these contexts, the synthesis of drug-like molecules with optically active CF₂H groups has been shown to be a very effective way to improve lead optimization in drug development.

Besides a few notable examples exist for the asymmetric construction of difluoromethylated stereocenters via fluorination17 or hydrogenation18,19,20,21, the most common approaches for obtaining enantioenriched difluoromethyl compounds have focused on direct asymmetric difluoromethylation22,23 and the functionalization of CF₂H-containing starting materials. Interestingly, nucleophilic addition with Me₃SiCF₂H, relying on chiral auxiliaries covalently linked to imines, has typically resulted in only moderate diastereoselectivities, even at low temperatures (−78 °C)24. In contrast, similar additions of carbanion nucleophiles to CF₂H-imines have shown significantly higher diastereoselectivity25,26,27,28. Consequently, various CF₂H synthons have been designed and applied in the enantioselective synthesis of chiral difluoromethylated compounds, employing both chiral auxiliary and asymmetric catalytic strategies. The most widely used electrophilic CF₂H synthons include difluoromethylated imines25,26,27,28, aldehydes/ketones29,30,31,32,33, and olefins34,35,36,37,38, where different nucleophiles attack C = X double bonds enantioselectively to form chiral stereogenic centers featuring a difluoromethyl group. Additionally, the only nucleophilic CF₂H synthon designed so far is a heterocyclic α-imino ketone, utilized as a bidentate directing group for asymmetric 1,4-additions39. However, these CF₂H synthons generally exhibit limited reactivity and enantioselectivity, especially compared to their trifluoromethylated analogs, and the reaction types are restricted. Therefore, a highly efficient and general strategy for the diversity-oriented synthesis of difluoromethylated compounds remains underdeveloped and is urgently needed.

Owing to their unique reactivity, structural diversity, and broad functional group tolerance, highly reactive radicals have facilitated a range of mild and efficient transformations, enabling the rapid assembly of functionalized, complex molecules, particularly through multi-step cascade reactions. Over the past few decades, catalytic enantioselective fluoroalkylation has seen remarkable progress, largely due to the relative stability of fluoroalkyl radicals conferred by the distinctive effects of fluorine. However, while asymmetric radical trifluoroalkylation has advanced rapidly40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47, transition-metal-catalyzed enantioselective radical difluoroalkylation has lagged behind, likely because of the weaker electron-withdrawing nature and smaller steric bulk of the difluoromethyl group. The only reported radical CF₂H synthon, described by Shen, enabled a nickel-catalyzed asymmetric arylation, yielding difluoromethylated 1,1-diarylalkanes with typically moderate enantiomeric excesses (ees), which were noticeably lower than those of their trifluoromethylated counterparts (Fig. 1b)48. There are various strategies to promote enantioselective control in the asymmetric transformation of radicals. As suggested, enhancing the stability of the radicals could offer sufficient recognition time within the chiral pocket of a metal complex, thereby improving the enantioselectivity (if oxidative addition is the enantio-determining step in the reaction). In addition, the application of directing groups is quite common in asymmetric transformations of radicals, where coordination between the metal center and the directing group often facilitates enantioselective control. Therefore, we aimed to design a CF₂H synthon that contains a directing group and can generate a stable radical in situ, to achieve the construction of a CF2H-substituted stereocenter via a radical pathway.

Based on the summary and proposed conception above, we have incorporated isoindolinone—a key structural motif widely used in various biologically active compounds49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56 into alkyl halides to create a CF₂H synthon for asymmetric radical transformations. Our design is based on the following considerations: (1) the nitrogen atom can stabilize the in situ-formed difluoromethylated α-radical, enhancing chiral recognition during the radical oxidation step; (2) the carbonyl oxygen serves as a coordination site for the metal center, facilitating control over the preferential geometry of the lower-energy enantiomeric transition state; and (3) the isoindolinone ring acts as a sterically hindered group to discriminate the CF₂H moiety. Moreover, this CF₂H synthon offers several advantages, including simple preparation, bench stability, low cost, and convenient removal.

Herein, we present an efficient strategy for the general and asymmetric construction of carbon stereocenters containing a difluoromethyl group via a nickel-catalyzed enantioconvergent Negishi cross-coupling with arylzinc reagents. This method features mild reaction conditions, a broad substrate scope, good catalytic efficiency, and excellent enantioselectivity. The resulting difluoromethylated isoindolinone derivatives could be further converted into chiral difluoromethylated amines, allowing for the straightforward synthesis of chiral analogs bearing CF₂H-substituted stereogenic centers found in various known bioactive molecules. This strategy presents an innovative and practical method for the efficient synthesis of CF₂H-containing chiral drug-like molecules, as both optically pure difluoromethylated amines and isoindolinones are significant structural motifs in various biologically active compounds, thereby holding significant potential for drug research and development.

Results and discussion

Optimization of reaction conditions

Our initial study commenced with 2-(1-chloro-2,2-difluoroethyl) isoindolin-1-one (1) as the CF2H-containing coupling partner and arylzinc reagent bearing CO2Me at the para position (2) as the nucleophile to optimize conditions for this nickel-catalyzed stereoconvergent Negishi arylation (Table 1). Given their critical role in asymmetric reactions, several chiral bis-oxazoline ligands were initially evaluated under catalytic conditions, using NiBr2•DME (10 mol%) and NaBr (2.0 equiv) in THF at −20 °C (Table 1); for more details see Table S1 in the SI). To our delight, bis-oxazoline (Box) ligand L7 could deliver the desired product 3a with moderate yield (35%) and acceptable ee value (59%), whereas the 2,2-bis(2-oxazoline) (Bi-ox) ligand L1 was less effective in asymmetric induction. When sterically bulkier ligands L8 and L9 were employed, the reaction proceeded smoothly to furnish the CF2H-containing amide with higher yields and ee (46% yield, 76% ee and 48% yield, 88% ee), respectively. The use of L10, which carries a bulkier substituent, led to a significant loss in enantioselective control, resulting in a decrease in the ee value to 35%. Subsequently, different kinds of solvents have been carefully tested in this reaction (Table 1, entries 1–4;). Notably, the ee value increased to 90% while maintaining a comparable yield when 2-Me-THF was used in place of THF. Based on this outcome of solvent screening, 2-Me-THF was selected as a co-solvent with THF and a promising result was achieved. (entry 3; 64% yield, 91% ee). After the careful evaluation of additives and nickel catalysts, 0.5 equivalent of NaI was proved to be the best choice, providing the desired arylation product in 66% yield with slightly higher enantioselectivity (93% ee, entry 8) while NiCl2•DME or NiBr2 decreased the reactivity of this coupling process obviously. (Table 1, entries 9 and 10). Finally, extending the reaction time to 48 h, the α-CF2H amide could be obtained in acceptable yield without diminishing the enantioselectivity (Table 1, entries 11; 88% yield, 93% ee).

Enantioselective Construction of Difluoromethylated Tertiary Stereocenters by Nickel-catalyzed C-C Coupling Reaction

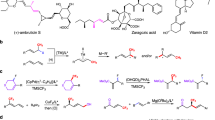

With the optimized conditions established, we proceeded to investigate the substrate scope of this enantioselective Negishi cross-coupling. As illustrated in Fig. 2, a diverse array of arylzinc reagents was initially examined in this reaction, coupling with 1a to yield products with excellent enantioselective control (Fig. 2). Notably, both electron-withdrawing groups such as ester (3a, 3b), trifluoromethyl (3c, 3d), fluoro (3e), chloride (3f) and electron-donating groups, including OMe (3g, 3h), OBz (3i), methyl (3k), phenyl (3 m) were well tolerated under the standard conditions. Besides, fused ring derivatives such as phenyl (3n) and naphthyl (3o), were also smoothly difluoroalkylated to afford the desired products. Furthermore, Polysubstituted benzenes were successfully obtained under these optimized conditions(3p, 3q, 3r, 3s), yielding 59–75% with 90%-95% ee. Notably, the Rivastigmine intermediate(3j) was synthesized with a yield of 61% and an ee of 95%.

Next, CF2H-substituted alkyl chlorides 1 were investigated in this Negishi cross-coupling reaction. As shown in Fig. 2, secondary α-CF2H chlorides with electron-withdrawing substituents were examed, such as fluorine (3t, 3u), chloride (3 v,3w), bpin(3x) and CF3(3 y), furnishing the coupling products with excellent ee values. Additionally, electron-donating groups such as OMe(3z), TMS (4a) and tBu (4b) were also tested, yielding corresponding products with good yields and enantioselectivity. Notably, this reaction is compatible with 3,4-dihydro-2H-isoquinolin-1-one (4cb–4h), resulting in moderate yields (55–75%) and excellent ee values (97–98%).

Motivated by the favorable functional group compatibility demonstrated in our reactions, we set out to explore the potential application of this asymmertic difluoroalkylation in modifying biologically active molecules. Notably, the desired products were obtained with good yields and excellent enantiomeric excess (ee) values in all cases, including (L)-menthol (4i), (L)-borneol (4j), majantol (4k), (S)-ibuprofen (4l), canagliflozin (4m), leaf alcohol (4n), and gemfibrozil (4o), which demonstrates the applicational potential of incorporating CF2H-substituted stereogenic centers in commercially available drugs and natural products.

Synthetic applications

To further illustrate the synthetic utility of this transformation, we conducted a large-scale experiment under the optimized condition. The corresponding product 3b was obtained with a 68% yield accompanied by an excellent ee value (95%) (Fig. 3a). Additionally, given the modification potential of substituting a methyl group with a difluoromethyl group in drug molecules, we achieved a 0.5 mmol-scale synthesis of α-CF2H amide 3j via this asymmetric Negishi cross-coupling, achieving a 58% yield with 95% ee. This intermediate could be further converted into a Rivastigmine analogue in three steps, with an overall yield of 49% while maintaining enantiocontrol (Fig. 3b).

Mechanism investigation

To gain a deeper understanding of the mechanism underlying this reaction, a series of control experiments were conducted. Firstly, the reaction was inhibited by the addition of radical scavenger 2,2,6,6-Tetramethylpiperidinooxy (TEMPO), high-resolution mass spectra (HRMS) indicated the presence of 5n, suggesting a radical pathway in the catalytic cycle (Fig. 3c). As illustrated in Fig. 3d, the addition of 0.02 equivalents of TEMPO to the reaction (green line) resulted in an induction period of approximately 40 hours, continuing beyond 48 hours. This observation suggests that a radical process might be involved in the catalytic cycle. Furthermore, the addition of Ni(cod)₂ significantly reduced the induction period induced by TEMPO (red line) while Ni(cod)₂ was unable to initiate the reaction (black line) in the absence of NiBr₂•DME. Based on these results, the Ni(I) species that is created when Ni(II) and Ni(0) react with each other might make it easier for radicals to form.

Based on the experimental results and previous literature57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69, we hypothesize a plausible reaction mechanism. Firstly, the alkyl radicals E may be generated by the reduction of the alkyl chloride 1 by Ni(I) species (D), and then E is captured by the aryl nickel species to form Ni (III) species C. Finally, the Ni (III) species C undergoes a reduction elimination process to produce product 3 and regenerates Ni(I) species D into the next catalytic cycle (Fig. 3e).

In conclusion, we have developed an efficient and versatile nickel-catalyzed asymmetric Negishi cross-coupling for difluoroalkylation, utilizing designed radical CF2H synthons. This approach allows the synthesis of a diverse array of chiral amines with difluoromethylated stereogenic centers. The method is characterized by straightforward operations, mild reaction conditions, excellent functional group tolerance, and high catalytic activity with exceptional enantioselectivity. It facilitates the late-stage modification of complex bioactive molecules and the synthesis of chiral analogues with CF2H-substituted stereogenic centers from known bioactive amines. This asymmetric radical transformation provides a practical and efficient solution for the synthesis of chiral difluoromethylated drug-like molecules, offering significant potential for drug discovery and development. Ongoing work in our laboratory focuses on the design, synthesis, and application of various fluorine-containing synthons for asymmetric radical fluoroalkylation to enable the rapid and efficient construction of biologically active chiral fluorinated compounds.

Methods

General procedure C for enantioselective construction of difluoromethylated tertiary stereocenters by Nickel-catalyzed C–C coupling reaction

NiBr2•DME (10 mol%, 0.02 mmol), L9 (13 mol%, 0.026 mmol) were firstly combined in a 25 mL oven-dried sealing tube. The vessel was evacuated and backfilled with Ar (repeated for 3 times), 2 mL 2-MeTHF was added via syringe and the complex was allowed to pre-stir at 25 °C for 30 min. Then CF2H-substituted secondary alkyl chloride 1 (1.0 equiv, 0.20 mmol) and NaI (0.5 equiv. 0.10 mmol) was added and the tube was cooled to −20 °C. And arylzinc reagent 2 (1.8 equiv, 0.36 mmol) was added dropwise. The tube was sealed with a Teflon lined cap and stired at −20 °C for 48 h. The reaction mixture was then diluted with EtOAc (~10 mL) and filtered through a pad of celite. The filtrate was added to brine (20 mL) and extracted with EtOAc (3 × 15 mL), the combined organic layer was dried over Na2SO4, filtrated and concentrated under vacuum. The residue was then purified by flash column chromatography to give the desired products.

Data availability

All data needed to support the conclusions of this manuscript are included in the main text or supplementary information. Data supporting the findings of this manuscript are also available from the authors upon request. X-ray crystallographic data for 3k (CCDC 2383618) has been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center. Copies of the data can be obtained free of charge via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

References

Mueller, K., Faeh, C. & Diederich, F. Fluorine in pharmaceuticals:: looking beyond intuition. Science 317, 1881–1886 (2007).

Zafrani, Y. et al. Difluoromethyl bioisostere: examining the “lipophilic hydrogen bond donor” concept. J. Med. Chem. 60, 797–804 (2017).

Purser, S., Moore, P. R., Swallow, S. & Gouverneur, V. Fluorine in medicinal chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 37, 320–330 (2008).

O’Hagan, D. Understanding organofluorine chemistry. an introduction to the C-F bond. Chem. Soc. Rev. 37, 308–319 (2008).

Berger, R., Resnati, G., Metrangolo, P., Weber, E. & Hulliger, J. Organic fluorine compounds: a great opportunity for enhanced materials properties. Chem. Soc. Rev. 40, 3496–3508 (2011).

Wang, J. et al. Fluorine in pharmaceutical industry: fluorine-containing drugs introduced to the market in the last decade (2001-2011). Chem. Rev. 114, 2432–2506 (2014).

Gillis, E. P., Eastman, K. J., Hill, M. D., Donnelly, D. J. & Meanwell, N. A. Applications of fluorine in medicinal chemistry. J. Med. Chem. 58, 8315–8359 (2015).

Champagne, P. A., Desroches, J., Hamel, J.-D., Vandamme, M. & Paquin, J.-F. Monofluorination of organic compounds: 10 years of innovation. Chem. Rev. 115, 9073–9174 (2015).

Ni, C. & Hu, J. The unique fluorine effects in organic reactions: recent facts and insights into fluoroalkylations. Chem. Soc. Rev. 45, 5441–5454 (2016).

Zhou, Y. et al. Next generation of fluorine-containing pharmaceuticals, compounds currently in phase II-III Clinical trials of major pharmaceutical companies: new structural trends and therapeutic areas. Chem. Rev. 116, 422–518 (2016).

Meanwell, N. A. Fluorine and fluorinated motifs in the design and application of bioisosteres for drug design. J. Med. Chem. 61, 5822–5880 (2018).

Jeffries, B. et al. Systematic investigation of lipophilicity modulation by aliphatic fluorination motifs. J. Med. Chem. 63, 1002–1031 (2020).

Glyn, R. J. & Pattison, G. Effects of replacing oxygenated functionality with fluorine on lipophilicity. J. Med. Chem. 64, 10246–10259 (2021).

Erickson, J. A. & McLoughlin, J. I. Hydrogen-bond donor properties of the difluoromethyl group. J. Org. Chem. 60, 1626–1631 (1995).

Narjes, F. et al. A designed P1 cysteine mimetic for covalent and non-covalent inhibitors of HCV/NS3 protease. Bioorg. Med Chem. Lett. 12, 701–704 (2002).

Meanwell, N. A. Synopsis of some recent tactical application of bioisosteres in drug design. J. Med. Chem. 54, 2529–2591 (2011).

Banik, S. M., Medley, J. W. & Jacobsen, E. N. Catalytic, asymmetric difluorination of alkenes to generate difluoromethylated stereocenters. Science 353, 51–54 (2016).

Chen, M.-W. et al. Enantioselective Pd-catalyzed hydrogenation of fluorinated imines: facile access to chiral fluorinated amines. Org. Lett. 12, 5075–5077 (2010).

Abe, H., Amii, H. & Uneyama, K. Pd-catalyzed asymmetric hydrogenation of α-fluorinated iminoesters in fluorinated alcohol: A new and catalytic enantioselective synthesis of fluoro α-amino acid derivatives. Org. Lett. 3, 313–315 (2001).

Sakamoto, T., Horiguchi, K., Saito, K., Mori, K. & Akiyama, T. Enantioselective transfer hydrogenation of difluoromethyl ketimines using benzothiazoline as a hydrogen donor in combination with a chiral phosphoric Acid. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2, 943–946 (2013).

Bai, D. et al. Highly regio- and enantioselective hydrosilylation of gem-difluoroalkenes by nickel catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202114918 (2022).

Zhao, X., Wang, C., Yin, L. & Liu, W. Highly enantioselective decarboxylative difluoromethylation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 29297–29304 (2024).

Ding, D., et al. Enantioconvergent copper-catalysed difluoromethylation of alkyl halides, Nat. Catal. 7, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41929-41024-01253-x (2024).

Zhao, Y., Huang, W., Zheng, J. & Hu, J. Efficient and direct nucleophilic difluoromethylation of carbonyl compounds and imines with TMSCF2H at ambient or low temperature. Org. Lett. 13, 5342–5345 (2011).

Funabiki, K., Nagamori, M., Goushi, S. & Matsui, M. First catalytic asymmetric synthesis of β-amino-β-polyfluoroalkyl ketones via proline-catalysed direct asymmetric carbon-carbon bond formation reaction of polyfluoroalkylated aldimines. Chem. Commun. 7, 1928–1929 (2004).

Liu, Y.-L. et al. Organocatalytic asymmetric Strecker reaction of di- and trifluoromethyl ketoimines. Remarkable fluorine effect. Org. Lett. 13, 3826–3829 (2011).

Liu, Y., Liu, J., Huang, Y. & Qing, F.-L. Lewis acid-catalyzed regioselective synthesis of chiral α-fluoroalkyl amines via asymmetric addition of silyl dienolates to fluorinated sulfinylimines. Chem. Commun. 49, 7492–7494 (2013).

Aparici, I. et al. Diastereodivergent synthesis of fluorinated cyclic β3-amino acid derivatives. Org. Lett. 17, 5412–5415 (2015).

Nie, J. et al. A perfect double role of CF3 groups in activating substrates and stabilizing adducts: the chiral Bronsted acid-catalyzed direct arylation of trifluoromethyl ketones. Chem. Commun. 2356–2358 (2009).

Aikawa, K., Yoshida, S., Kondo, D., Asai, Y. & Mikami, K. Catalytic asymmetric synthesis of tertiary alcohols and oxetenes bearing a difluoromethyl group. Org. Lett. 17, 5108–5111 (2015).

van der Mei, F. W., Qin, C., Morrison, R. J. & Hoveyda, A. H. Practical, broadly applicable, α-Selective, Z-Selective, diastereoselective, and enantioselective addition of allylboron compounds to mono-, di-, tri-, and polyfluoroalkyl ketones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 9053–9065 (2017).

Pluta, R., Kumagai, N. & Shibasaki, M. Direct catalytic asymmetric aldol reaction of α-alkoxyamides to α-fluorinated ketones. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 2459–2463 (2019).

Murata, R., Matsumoto, A., Asano, K. & Matsubara, S. Desymmetrization of gem-diols via water-assisted organocatalytic enantio- and diastereoselective cycloetherification. Chem. Commun. 56, 12335–12338 (2020).

Grassi, D., Li, H. & Alexakis, A. Formation of chiral fluoroalkyl products through copper-free enantioselective allylic alkylation catalyzed by an NHC ligand. Chem. Commun. 48, 11404–11406 (2012).

Yu, X. et al. A convenient approach to difluoromethylated all-carbon quaternary centers via Ni(ii)-catalyzed enantioselective Michael addition. Rsc Adv. 8, 19402–19408 (2018).

Bigotti, S. et al. Functionalized fluoroalkyl heterocycles by 1,3-dipolar cycloadditions with γ-fluoro-α-nitroalkenes. Tetrahedron Lett. 50, 2540–2542 (2009).

Huang, W.-S. et al. Catalytic asymmetric synthesis of α,α-difluoromethylated and α-fluoromethylated tertiary alcohols. Org. Lett. 21, 7509–7513 (2019).

Hu, M., Tan, B. B. & Ge, S. Enantioselective Cobalt-catalyzed hydroboration of fluoroalkyl-Substituted alkenes to access chiral fluoroalkylboronates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 15333–15338 (2022).

Gao, F. et al. Catalytic asymmetric construction of tertiary carbon centers featuring an α-difluoromethyl group with CF2H-CH2-NH2 as the “Building Block. Org. Lett. 23, 2584–2589 (2021).

Min, Y. et al. Diverse synthesis of chiral trifluoromethylated alkanes via Nickel-catalyzed asymmetric reductive cross-coupling fluoroalkylation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 9947–9952 (2021).

Zhou, P., Li, X., Wang, D. & Xu, T. Dual Nickel- and photoredox-catalyzed reductive cross-coupling to access chiral trifluoromethylated alkanes. Org. Lett. 23, 4683–4687 (2021).

He, Y. et al. Ligand-promoted, enantioconvergent synthesis of aliphatic alkanes bearing trifluoromethylated stereocenters via hydrotrifluoroalkylation of unactivated alkenes. Chin. J. Chem. 40, 1531–1536 (2022).

Wu, B.-B., Xu, J., Bian, K.-J., Gao, Q. & Wang, X.-S. Enantioselective synthesis of secondary β-trifluoromethyl alcohols via catalytic asymmetric reductive trifluoroalkylation and diastereoselective reduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 6543–6550 (2022).

Zhou, P., Lu, S., Wu, X., Zhong, W. & Xu, T. Selectively Tunable Synthesis of α-Trifluoromethyl Ketones. Org. Lett. 25, 2344–2348 (2023).

Jin, R.-X. et al. Asymmetric construction of allylicstereogenic carbon center featuring atrifluoromethyl group via enantioselective reductive fluoroalkylation. Nat. Commun. 13, 7035 (2022).

Lu, S., Hu, Z., Wang, D. & Xu, T. Halogen-atom transfer enabled catalytic enantioselective coupling to chiral trifluoromethylated alkynes via dual Nickel and photocatalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202406064 (2024).

Hossain, A., Anderson, R. L., Zhang, C. S., Chen, P.-J. & Fu, G. C. Nickel-catalyzed enantioconvergent and diastereoselective allenylation of alkyl electrophiles: simultaneous control of central and axial chirality. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 7173–7177 (2024).

Huang, W., Hu, M., Wan, X. & Shen, Q. Facilitating the transmetalation step with aryl-zincates in nickel-catalyzed enantioselective arylation of secondary benzylic halides. Nat. Commun. 10, 2963 (2019).

Cui, H. et al. Three isoprenylisoindole alkaloid derivatives from the aangrove endophytic fungus Diaporthe sp SYSU-HQ3. Org. Lett. 19, 5621–5624 (2017).

Hwang, G. J. et al. Ulleungdolin, a polyketide-peptide hybrid bearing a 2,4-Di-O-methyl-β-D-antiarose from Streptomyces sp. 13F051 Co- cultured with Leohumicola minima 15S071. J. Nat. Prod. 85, 2445–2453 (2022).

Sala, S. et al. Dendrillic acids A and B: nitrogenous, rearranged spongian nor- diterpenes from a Dendrillasp. Mar. Sponge. J. Nat. Prod. 86, 482–489 (2023).

Belliotti, T. R. et al. Isoindolinone enantiomers having affinity for the dopamine D4 receptor. Bioorg. Med Chem. Lett. 8, 1499–1502 (1998).

Uemura, S., Fujita, T., Sakaguchi, Y. & Kumamoto, E. Actions of a novel water-soluble benzodiazepine-receptor agonist JM-1232(-) on synaptic transmission in adult rat spinal substantia gelatinosa neurons. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 418, 695–700 (2012).

Nishiyama, T., Chiba, S. & Yamada, Y. Antinociceptive property of intrathecal and intraperitoneal administration of a novel water-soluble isoindolin-1-one derivative, JM 1232 (-) in rats. Eur. J. Pharm. 596, 56–61 (2008).

Kanamitsu, N. et al. Novel water-soluble sedative-hypnotic agents: Isoindolin-1-one derivatives. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 55, 1682–1688 (2007).

Zhang, H. et al. Novel isoindolinone-based analogs of the natural cyclic peptide fenestin a: synthesis and antitumor activity. Acs Med. Chem. Lett. 13, 1118–1124 (2022).

Son, S. & Fu, G. C. Nickel-catalyzed asymmetric Negishi cross-couplings of secondary allylic chlorides with alkylzincs. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 2756 (2008).

Rudolph, A. & Lautens, M. Secondary alkyl halides in transition-metal-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 48, 2656–2670 (2009).

Liang, Y. & Fu, G. C. Catalytic asymmetric synthesis of tertiary alkyl fluorides: negishi cross-couplings of racemic α,α-dihaloketones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 5520–5524 (2014).

Cherney, A. H., Kadunce, N. T. & Reisman, S. E. Enantioselective and enantiospecific transition-metal-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions of organometallic reagents to construct C–C Bonds. Chem. Rev. 115, 9587–9652 (2015).

Liang, Y. & Fu, G. C. Nickel-catalyzed alkyl-alkyl cross-couplings of fluorinated secondary electrophiles: a general approach to the synthesis of compounds having a perfluoroalkyl substituent. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 9047–9051 (2015).

Liang, Y. & Fu, G. C. Stereoconvergent Negishi arylations of racemic secondary alkyl electrophiles: differentiating between a CF3 and an alkyl group. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 9523–9526 (2015).

Iwasaki, T. & Kambe, N. Ni-Catalyzed C-C couplings using alkyl electrophiles. Top. Curr. Chem. (Z.) 374, 66 (2016).

Schmidt, J., Choi, J., Liu, A. T., Slusarczyk, M. & Fu, G. C. A general, modular method for the catalytic asymmetric synthesis of alkylboronate esters. Science 354, 1265–1269 (2016).

Fu, G. C. Transition-metal catalysis of nucleophilic substitution reactions: a radical alternative to SN1 and SN2 processes. Acs Cent. Sci. 3, 692–700 (2017).

Schwarzwalder, G. M., Matier, C. D. & Fu, G. C. Enantioconvergent cross-couplings of alkyl electrophiles: The catalytic asymmetric synthesis of organosilanes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 3571–3574 (2019).

Huo, H., Gorsline, B. J. & Fu, G. C. Catalyst-controlled doubly enantioconvergent coupling of racemic alkyl nucleophiles and electrophiles. Science 367, 559 (2020).

Yang, Z.-P., Freas, D. J. & Fu, G. C. The Asymmetric synthesis of amines via Nickel-catalyzed enantioconvergent substitution reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 2930–2937 (2021).

Tong, X., Schneck, F. & Fu, G. C. Catalytic enantioselective α-alkylation of amides by unactivated alkyl electrophiles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 14856–14863 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the National Key R&D Program of China (2021YFF0701700) and the National Science Foundation of China (22271264, 2197128) for financial support. Part of this research was conducted at the Instruments Center for Physical Science at the University of Science and Technology of China.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.-S.W. designed the experiments and directed the project. P.L., Y.H. performed chemical experiments and prepared the supplemental information. C.-H.J., W.-X.C., and T.Z. prepared several ligands and substrates. X.N. performed chemical experiments in the revision process. X.-S.W., R.-X.J., and W.-R.R. co-wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, P., He, Y., Jiang, CH. et al. CF2H-synthon enables asymmetric radical difluoroalkylation for synthesis of chiral difluoromethylated amines. Nat Commun 16, 599 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-55912-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-55912-z