Abstract

Bending loss is one of the serious problems for constructing nanophotonic integrated circuits. Recently, many works reported that valley photonic crystals (VPhCs) enable significantly high transmission via 120-degree sharp bends. However, it is unclear whether the high bend-transmission results directly from the valley-photonic effects, which are based on the breaking of inversion symmetry. In this study, we conduct a series of comparative numerical and experimental investigations of bend-transmission in various triangular PhCs with and without inversion symmetry and reveal that the high bend-transmission is solely determined by the domain-wall configuration and independent of the existence of the inversion symmetry. Preliminary analysis of the polarization distribution indicates that high bend-transmissions are closely related to the appearance of local topological polarization singularities near the bending section. Our work demonstrates that high transmission can be achieved in a much wider family of PhC waveguides, which may provide novel designs for low-loss nanophotonic integrated circuits with enhanced flexibility and a new understanding of the nature of valley-photonics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

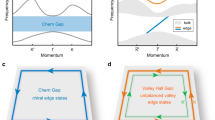

Photonic crystal waveguides (PhCWGs) that support highly confined light modes have wide applications in telecommunication and data processing1,2,3,4. Recently, valley photonic crystals (VPhCs), an optic implementation of valley Hall effect (VHE)5,6,7, have offered large-scale, all-dielectric designs for PhCWGs. VHE describes that two-dimensional honeycomb lattice crystals possess a valley degree of freedom (DOF). The valley DOF is hosted at the corners (K and \({K}^{{\prime} }\) points) in the first Brillouin zone, connected by time-reversal-symmetry (TRS) and inversion symmetry. Valley-dependent physics can be extracted by breaking the inversion symmetry of the two-dimensional lattice, which introduces opposite, non-zero Berry curvatures to different valleys8,9,10. Inspired by this idea, the photonic version VHE has been explored in two-dimensional photonic systems11,12,13. Opposite Berry curvature and angular momentum can be observed for photonic states with different valley indices11,12,13,14,15,16,17. The usual Chern number, defined with the integration of Berry curvature over the first Brillouin zone, vanishes to zero in a VPhC due to the TRS. However, since there exist local Berry curvatures around K and \({K}^{{\prime} }\) points, a non-zero valley Chern number can be defined as \({C}_{v}={C}_{K}-{C}_{{K}^{{\prime} }}\), where CK (\({C}_{{K}^{{\prime} }}\)) is integrated over half-Brillouin-zone around the K (\({K}^{{\prime} }\)) valley16,17,18.

Bending loss is one of the most serious problems in constructing photonic integrated circuits employing nanophotonics19,20,21,22. This is because sharp bends exhibit significantly large reflections when the bending radius is comparable to the wavelength of light. For example, a simple single-missing-hole line defect waveguide (so-called, W1), the most widely-used PhC waveguides, have large reflections at 120-degree bends unless sophisticatedly modified at the corners19,20,21. In contrast, many recent reports showed that VPhC waveguides, constructed by connecting two VPhCs with opposite valley Chern numbers, exhibit extraordinarily high transmission through 120-degree bends within a wide frequency range14,15,16,17,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39. This interesting property of VPhCs has attracted considerable attention. Since backscattering suppression is generally expected for edge or domain-wall modes in topological insulators, reflection-free transmission has been considered a topological feature of VPhCs. Naively, if one assumes that inter-valley scattering is prohibited, valley spins should be conserved, and thus the back reflection should be suppressed.

However, no unambiguous demonstration proves the direct relationship between high transmission in bends and the topological properties. In fact, we believe some ambiguities remain. (1) In valley-photonics, backscattering suppression requires the conversation of valley pseudospins. However, it has not been theoretically clarified whether inter-valley scattering could be prohibited or valley pseudospins could be conserved at bends. In the usual situation, valley spin can be easily flipped upon reflection. For example, Arregui et al.40 numerically showed that the suppression of backscattering occurs only at ultraslow light modes in straight VPhCWGs with minimal disorders, and a recent experimental work supported their conclusion41. This minimal perturbation condition is hardly satisfied in the transmission in 120-degree bends, which one may treat as a strong disorder that breaks the translational symmetry. (2) Experimentally or numerically, it has not been directly proved that the high transmission is due to the valley-photonic effects. In some previous studies27,31, W1WGs are used as the reference to verify the high transmission in VPhCWGs. However, the domain-wall configurations of W1WGs and VPhCWGs are largely different. Besides the inversion symmetry in the bulk lattice, W1WGs also have larger waveguide widths and their domain-wall configuration is not compatible with a honeycomb structure. Therefore, there remain possibilities that the high transmissions result from the difference in the domain-wall configuration instead of the topological effect.

In this study, to identify the origin of high transmission in 120-degree bent PhCWGs, we separate the effect of inversion symmetry and the domain-wall configuration by employing a specific model structure in which we can vary the interface condition and the inversion symmetry separately. We show theoretical treatments first, followed by extensive experimental works. Our theoretical and experimental studies reveal a surprising result in which the high bend-transmittance appears irrespective of the existence of the inversion symmetry. It is shown that the high bend-transmission can be realized in a much wider range of structures than previously expected. Since the breaking inversion symmetry is the origin of the valley photonic effect, our finding indicates that the high bend-transmittance does not originate from the valley effect. Furthermore, we carefully investigate the appearance condition of the high bend-transmission for various interface structures, and finally give an intriguing insight into the origin of the high bend-transmission.

Results

Model structures

We propose to employ a systematic model representing various domain-wall configurations with and without the inversion symmetry. In a honeycomb lattice, restoring the inversion symmetry closes the bandgap and thus no domain-wall modes remain. Here, we adopt triangular-lattice air-hole PhCs as shown in the inset image of Fig. 1a, b. We manipulate the inversion symmetry by changing the hole shapes. The PhC is inversion-symmetric (IS-PhC) w.r.t. the lattice site when the air holes are circular; and is inversion-asymmetric (IA-PhC) w.r.t. any on-plane point when the air holes are triangular. In valley-photonics, a triangular lattice is sometimes treated as an extreme case of honeycomb lattice with one sublattice disappearing, which is demonstrated by a continuous evolution of sublattice size using the unit cell for the honeycomb lattice25,42,43. Even if the structure looks asymmetric in the honeycomb unit cell, rigorous inversion symmetry is still not broken in a triangular lattice. It is worth noting that such a continuous evolution process does not always preserve the lattice symmetry.

a with and b without inversion symmetry. Inset in a shows the IS-PhC with circular air holes in the silicon slab. The lattice constant is 400 nm. The radius of air holes is 102 nm. Inset in b shows the A-type and B-type IA-PhC with triangular holes. The lattice constant is 400 nm. The side length of air holes is 277 nm. The effective refractive index of silicon is 2.65. c Conceptual illustration of the universal design of triangular lattice waveguides that are compatible with 120-degree sharp bends. This large picture shows a bulk triangular lattice (S = 0) with inversion symmetry (circular holes). The bent interface forms a 60-degree angle. The red dotted line is the angle bisector. The smaller pictures show the five domain-wall configurations obtained by shifting the red region when the shifting parameter S is −2, −1, 1, 2, and 3.

The IS-PhC preserves inversion symmetry and is topologically trivial. The valley topology of IA-PhCs have been demonstrated in both hole-type34,37,44 and pillar-type designs.13,16,35,36,38. Here we focus on the first bandgap of TE-polarization in hole-type PhCs (Fig. 1a, b). This first bandgap is most widely used in PhC waveguides, including W1WGs. Since the Dirac degeneracy occurs between the second and third bands at K points, the first bandgap always exists even with the inversion symmetry. Therefore, one can easily alternate the inversion symmetry without closing the first bandgap. The crucial point is that the valley-photonic effect exists in a triangular IA-PhC. The band topology is characterized by Berry curvature Ωnk defined as:45,46,47

where unk is the periodic part of the Bloch wavefunction and n is the band index.

To date, all established valley PhCs exhibit non-trivial Berry curvature, which arises from the anomaly at the K (\({K}^{{\prime} }\)) point. This Berry curvature leads to novel valley-dependent phenomena, such as angular momentum. Thus, valley-dependent physics is intrinsically linked to non-trivial Berry curvature, a concept widely regarded as fundamental across various areas of topological physics48,49,50. To verify the topological properties of IS- and IA-PhCs, we calculate their Berry curvatures near K point via Wilson loop and k ⋅ p perturbation method (see Supplementary Information (2) for details). IA-PhC has nontrivial Berry curvatures around the K and \({K}^{{\prime} }\) points at the first two bands. Moreover, the Berry curvatures at the first and the second bands have opposite signs. Thus the first TE bandgap is topological and the valley-dependent properties should be observable at the IA-PhC. In contrast, the IS-PhCs have zero Berry curvature around the K and \({K}^{{\prime} }\) points. Thus, the topology of the first TE bandgap can be manipulated by simply changing the hole shape.

Starting from this bulk design, a wide variety of domain-walls can be constructed by shifting the lattice in the half-space. As shown in Fig. 1c, we divide the triangular lattice PhC with a 60-degree angle boundary into the blue and red regions. We can shift the two divided regions along the angle bisector (dotted red line) to introduce a line defect to the bulk lattice and thus construct a 120-degree bent waveguide. Waveguides constructed in this manner can be characterized by the shift direction and shift distance D. Here, we define a shifting parameter \(S=\sqrt{3}D/a\). S is positive (negative) when the red region is shifted away from (towards) the blue region. When S = 3, the waveguide is a conventional W1WG with circular holes. When S = ±1, the domain wall is a zigzag interface. When S = ±2, the domain wall is a bearded interface. Note that when S is even, the waveguide is mirror-symmetric. When S is odd, the waveguide is glide-symmetric. When S is a non-integer, the interface has neither mirror symmetry nor glide symmetry.

We can also classify the domain-wall configuration of other types of VPhCs previously reported in a similar manner. For example, the zigzag interface in reference [25]25 corresponds to S = −1, and the bearded interface in reference [28]28 corresponds to S = −2. In addition, honeycomb lattice VPhCs can be classified in the same manner if we focus on the configuration of large holes (or pillars). When S = ±1, the lattice becomes one of the sublattices of a zigzag interface honeycomb lattice14,15,23,24,25,26,40. When S = ±2, the lattice becomes one of the sublattices of a bearded interface honeycomb lattice17,28,29,30,31,32. The sign change of S corresponds to the sublattice exchange in a honeycomb lattice. We assume that the broken inversion symmetry and domain-wall types (parameter S) would both be able to affect the high transmission through sharp bends. The comparison between VPhCWGs and W1WGs alone cannot distinguish between the two factors. Therefore, in this study, we compare the light transmission through 120-degree sharp bends between IS-PhCWGs and IA-PhCWGs having the same domain-wall type and then examine different domain-wall types. We mainly investigate the aforementioned five types of interfaces: S = −2, −1, 1, 2, 3.

Numerical studies of Z-shaped waveguides

(i) W1WG (S = 3, mirror-symmetric waveguides with inversion symmetry)

Here we numerically investigate Z-shaped waveguides in Si PhC slabs, consisting of a pair of 120-degree bends with the middle segment length of 20a. Firstly, we investigate the configuration of S = 3 with circular holes, corresponding to W1WG, which is mirror-symmetric and possesses inversion symmetry. It has an even and an odd band in the PBG (Fig. 2a), and here we focus on the even modes in the lower-frequency band. As shown in Fig. 2a with a black arrow, there is a single-mode region in the frequency range a/λ = 0.265–0.282. Within this single-mode region, we can see a clear transmission contrast between the straight (Fig. 2b, black curve) and the bent (Fig. 2b, red curve) waveguides. There are strong ripples in the spectrum of the bent waveguide. We calculate the corresponding cavity length to be around 21.5a from the free spectral range (FSR) of the ripples. This length is very close to the middle segment’s length 20a in the Z-shaped waveguide. Therefore, we confirm that these are Fabry-Pérot (F-P) ripples resulting from strong reflection at the two bends. Suppose bend reflection is the only source of energy loss in the waveguide, one can approximate the transmittance spectra with the transmission function of a simple Fabry-Perot interferometer: \(T=\frac{1}{1+\frac{4R}{{(1-R)}^{2}}{(\sin \frac{\sigma }{2})}^{2}}\), where R is the reflectivity at each bend. We call R the F-P reflectivity and label it RFP. To quantitatively analyze the transmission property of a Z-shaped waveguide, we calculate the average transmittance Tav and the F-P reflectivity RFP from the simulated spectrum. The calculation is conducted within the single-mode region omitting ultraslow-light frequencies (see “Method” section for details). For the W1WG the frequency range is a/λ = 0.269–0.278. The calculated Tav and RFP are 0.47 and 0.40.

a The 2-dimensional band structure. The black arrow shows the single-mode region. The inset shows one corner of the bent waveguide. b The transmittance spectra of the straight W1WG (black curve) and Z-shaped W1WG. The average transmittance is 0.47, and the F-P reflectivity is 0.40. c The out-of-plane magnetic field Hz of the Z-shaped W1WG at a/λ = 0.270. The transmittance is 0.39. The five-pointed star indicates the location of the wave source. The arrow points toward the propagation direction.

As a typical example of the field distribution for the Z-shaped waveguide, Hz near a bend at a/λ = 0.270 is shown in Fig. 2c where the transmittance is 0.39. The five-pointed star indicates the location of the light source, exciting a rightward propagating mode. The light intensity is fairly reduced at the output port, and there is significant reflected intensity behind the excitation source. Hereafter, we investigate other types of waveguides focusing on their Tav and RFP.

(ii) S = −2, glide-symmetric waveguides

Here we investigate the S = −2 IA-PhCWGs without inversion symmetry (inset of Fig. 3a). As described before, this lattice and its domain-wall structure possess typical VPhC properties, such as non-trivial Berry curvature and angular momentum. In addition, due to the glide symmetry of this waveguide, two bands degenerate at the edge of the Brillouin zone (BZ), as shown in Fig. 3a. The modes have a mixed spatial parity at the waveguide’s interface. The band above the degenerate frequency (upper band) has a broad single-mode region (a/λ = 0.267–0.301). However, the band below the degenerate frequency (lower band) overlaps with the bulk modes, making it impossible to excite the lower band. Here we focus on the upper band only. The upper band exhibits a very high transmission, as shown in Fig. 3b. Tav and RFP in this Z-shaped waveguide are estimated to be 0.97 and 0.03. Figure 3c shows the Hz distribution at a/λ = 0.270, where the transmittance is 0.97. There is no indication of attenuation during the propagation. In addition, there is no apparent reflected intensity behind the excitation source, indicating very weak backscattering. These results show that the reflection at bends is significantly small. This configuration (S = −2) corresponds to a bearded interface in a honeycomb lattice VPhC waveguide17. This result of high transmission is essentially similar to those reported in ref. 17.

a The PBS of S = −2 IA-PhCWG. The black arrow shows the single-mode region. The inset shows one corner of the bent waveguide. b The transmittance spectra of the straight S = −2 IA-PhCWG (black curve) and Z-shaped S = −2 IA-PhCWG (red curve). The average transmittance is 0.97. The F-P reflectivity is 0.03. c The out-of-plane magnetic field Hz of the Z-shaped S = −2 IA-PhCWG at a/λ = 0.280, with a transmittance of 0.97. The Hz has mixed spatial parity and meanders along the glide-symmetric interface. d The PBS of S = −2 IS-PhCWG. The black arrow shows the single-mode region. The inset shows one corner of the bent waveguide. e The transmittance spectra of the straight S = −2 IS-PhCWG (black curve) and Z-shaped S = −2 IS-PhCWG (red curve). The average transmittance of the upper band is 0.94. The F-P reflectivity of the upper band is 0.06. The average transmittance of the lower band is 0.40. The F-P reflectivity of the lower band is 0.52. f The out-of-plane magnetic field Hz of the Z-shaped S = −2 IS-PhCWG at a/λ = 0.283, with transmittance 0.93.

Next, we investigate S = −2 waveguides with inversion symmetry by changing the air hole shape from triangular to circular. That is, we keep the same lattice configuration but restore the inversion symmetry. As shown in Fig. 3d, S = −2 IS-PhCWG has a wide single-mode region (a/λ = 0.261–0.293) with a degeneracy point at the BZ edge (a/λ = 0.270). Since the degeneracy point is located within the bandgap, both upper and lower bands have sufficient single-mode regions. Surprisingly, the Z-shaped waveguide shows also very high transmission (Fig. 3b) with Tav of 0.94 in the upper band, even though the inversion symmetry is NOT broken. The RFP is 0.06. This high transmittance is comparable to that of the upper band in S = −2 IA-PhCWG and other reported results in Z-shaped VPhCWGs11,12,13,14,15,16,17,23,24,25,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39. Figure 3c shows the Hz distribution at a/λ = 0.283 (upper band), where the transmittance is 0.93. Same as that of S = −2 IA-PhCWG, there is no indication of attenuation during the propagation. The present result implies an important consequence. Because the inversion symmetry is not broken in this waveguide (S = −2 IS-PhCWG), it suggests that the observed high transmission may not be caused by the valley-photonic effect, which essentially requires the broken inversion symmetry.

Interestingly, the transmittance of the lower band differs significantly from that of the upper band in S = −2 IS-PhCWGs. The Tav of only 0.40. The RFP is 0.52 which is even larger than that of the W1WG. It should be noted that similar transmission contrast between upper and lower modes has been reported for glide-symmetric honeycomb-lattice VPhC waveguides. Yoshimi et al.30 have reported a distinctive transmission contrast in a bearded-interface glide-symmetric PhCWG with a honeycomb lattice (S = 2 waveguide in the terminology of the present paper). Although the high bend-transmission was recently confirmed for the upper band of an S = −2 triangular-lattice IS-PhCWG42,43, it has not been reported that the similar high contrast between upper and lower modes exists in the triangular-lattice IS-PhCWG, which we believe is important for understanding the nature of the transmission through sharp bends. Since the upper/lower band transmission contrast has been observed in Z-shaped glide-symmetric PhCWGs irrespective of the inversion symmetry, we speculate that this phenomenon originates from the domain-wall configuration instead of the symmetry-breaking in the bulk lattice.

(iii) Other S-value waveguides and summary of numerical studies

Following the same method as W1WGs and S = −2 PhCWGs, we have also numerically investigated S = −1 IA-PhCWGs, S = −1 IS-PhCWGs, S = 1 IA-PhCWGs, S = 1 IS-PhCWGs, S = 2 IA-PhCWGs, S = 2 IS-PhCWGs, and S = 3 IA-PhCWGs. For these waveguide types, we only report a brief result here and leave a detailed discussion in the Supplementary Information (3).

Table 1 summarizes Tav and RFP for each S with and without inversion symmetry. When S is even, the results of both the upper and lower bands are shown. This table shows that S = 1, the upper band of S = −2, and the lower band of S = 2 have high Tav and low RFP. Most importantly, these characteristics do not depend on the existence of the inversion symmetry. It is worth noting that a large transmission contrast between the upper and lower bands for glide-symmetric waveguides, which was previously noted as proof of “topological property” for one of the bands, is also seen for inversion-symmetric waveguides. The fourth column in Table 1 shows the classification of previously reported VPhCs by the S parameter. All previous results can be classified in the same manner, and agree with our result. This table strongly suggests that this high transmission behavior does not originate from the broken inversion symmetry, but possibly originated from the domain configuration. Before concluding this speculation, we check other possible causes. In Supplementary Information (4), we examine the parity of modes, the group refractive index, and the sign of the group velocity for each case. We find no correlation between these variables and the observed distinctive difference in the bend-transmittance.

To conclude, we have investigated the transmittance of various Z-shaped PhC waveguides constructed from the valley-topological IA-PhCs and the trivial IS-PhCs. Our results strongly suggest that the observed high bend-transmittance and low reflectivity are not dependent on the inversion symmetry but attributed to the domain-wall configuration.

Experimental studies of Z-shaped waveguides

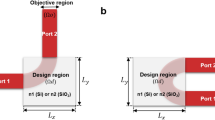

In this part, we experimentally examine the transmission properties of bent PhCWGs. We implement the PhC structures in Si slabs fabricated by highly accurate lithography and etching process. The fabrication details are described in “Methods”. We couple the waveguides to the incident light from a wavelength-tunable laser with 5dBm power and measure the transmission spectra from 1355 to 1640 nm.

Figure 4a shows the optical microscope image of the fabricated Z-shaped waveguide. The TE-polarized light is guided through a silicon taper and is coupled to the PhCWG via a silicon nanowire. The three segments of Z-shaped waveguides have lengths of 100a, 30a, and 100a respectively. Figure 4b shows the bending part of a S = −2 IS-PhCWG and Fig. 4c shows the straight part of a S = 1 IA-PhCWG. The length of the straight waveguides is 230a. In a straight waveguide, there are reflections between the PhCWG and the silicon waveguide, making the whole waveguide an F-P cavity. F-P resonances may occur inside both the 100a segment and the 30a segment in a Z-shaped waveguide. As a typical example in our measurement, for a waveguide with a = 400 nm, and the waveguide mode with a group velocity of 0.1c and wavelength of 1500 nm, the wavelength FSR is 1.2 nm, 2.8 nm, and 9.4 nm in the 230a, 100a and 30a cavity respectively.

Here we show the measured transmitted intensity. We begin with S = 3 IS-PhCWGs (W1WGs). The lattice constant a is 424 nm. The radius of air holes r is 97 nm. As shown in Fig. 5a, S = 3 IS-PhCWGs have single waveguide modes between 1515 and 1574 nm (yellow region). We evaluate Tav in the single mode region. For S = 3 IS-PhCWGs, Tav = 0.31. Note that this Z-shaped waveguide shows ripples in the spectrum, whose FSR is 3–10 nm. The observed FSR seems to roughly correspond to the FP resonance of the 30a segment, but the ripple is complicated especially in the longer wavelength region. Figure 5b shows the spectra of S = 3 IA-PhCWGs (a = 416 nm), which have the same domain-wall configuration as W1WG but triangular air holes that break the inversion symmetry. The side length of the triangular air holes s is 232 nm. The S = 3 IA-PhCWGs have single modes between 1463 and 1532 nm. The evaluated Tav is also low, 0.48. These results agree with our theoretical simulation. Similar to S = 3 IS-PhCWGs, there are strong ripples in the spectrum. However, the ripples are rather complicated and hard to analyze. This trend is seen in all samples shown below. We regard that these complicated spectra result from the complex multiple reflections at section boundaries which exist in the fabricated devices but do not in the simulated structures. Hence, we could not evaluate RFP from the measured spectra.

a, b S = 3 PhCWG, c, d S = 2 PhCWG, e, f S = 1 PhCWG, g, h S = −1 PhCWG and i, j S = −2 PhCWG. Black lines indicate the straight waveguides and red lines indicate the Z-shaped waveguides with two bends. Yellow and green boxes show the single-mode regions. Tav shows the relative average transmittance of the Z-shaped waveguides. A SEM image of the corresponding waveguide is shown on the right side of each plot.

Hereafter, we investigate other domain-wall configurations one by one and evaluate Tav. Figure 5c shows S = 2 IS-PhCWGs (a = 441 nm, r = 92 nm). As discussed in the simulation section, the S = 2 PhCWGs have glide-symmetric interfaces and have two touching bands in the photonic bandgap. However, the single-mode region (1410–1580 nm) only exists in the (frequency-wise) upper band. The upper band has an average bend-transmittance Tav of 0.19, lower than that of the W1WG. Figure 5d shows the spectra of S = 2 IA-PhCWGs (a = 418 nm, s = 342 nm), which corresponds to a bearded interface in honeycomb lattice VPhCWG29,30,31,32,40. Like its inversion-symmetric counterpart, S = 2 IA-PhCWG has single modes (1405–1530 nm) in the upper band. The Tav is 0.15. The extremely low transmittance in the upper band of S = 2 PhCWGs agrees with the previous reports29,30,31,32 as well as our simulation results.

Figure 5e shows the result for S = 1 IS-PhCWGs (a = 427 nm, r = 120 nm). The overall transmission in the Z-shaped S = 1 IS-PhCWGs (red) is comparable to that of the straight waveguide. Tav is as high as 0.85 in the single-mode range 1437–1504 nm. S = 1 IA-PhCWGs (a = 441 nm, s = 314 nm) corresponds to a zigzag interface VPhCWG. The previous reports are all based on the honeycomb lattice12,14,15,23,24,51. Similar to its IS- counterpart, the Z-shaped S = 1 IA-PhCWGs have transmission comparable to that of the straight waveguides (Fig. 5f). Tav is 0.86 in the single-mode region 1464-1553 nm.

Figure 5g shows the measured spectra of S = −1 IS-PhCWG (a = 419 nm, r = 92 nm) has a narrow single-mode region from 1420 to 1448 nm. The Tav is 0.74. The amplitude of F-P resonances in the Z-shaped S = −1 IS-PhCWG’s spectrum is as small as that of the straight waveguide. S = − 1 IA-PhCWG (Fig. 5h, a = 442 nm, s = 268 nm) corresponds to another type of zigzag VPhCW25. It also has a narrow single-mode region from 1355 to 1404 nm. The Tav is 0.83.

Finally, we investigate the S = −2 PhCWGs with glide-symmetry interface. Figure 5i shows the result for S = −2 IS-PhCWGs (a = 418 nm, r = 115 nm). Both the straight and the Z-shaped waveguides have a transmission gap near 1500 nm. We speculate that fabrication errors in the air holes’ size break the glide-symmetry, opening a bandgap and creating flat-band regions near the edges of the upper/lower bands. The upper band (green, 1379–1486 nm) shows higher transmission in the Z-shaped waveguide than in the straight waveguide. Therefore we set the Tav to be 1.00. The lower band (yellow, 1516–1610 nm) shows low transmittance in the Z-shaped waveguide. The Tav is 0.38. Figure 5j shows the spectra of the S = −2 IA-PhCWGs (a = 469 nm, s = 287 nm). In the numerical calculations, only the upper band of the S = −2 PhCWGs have single modes. Actually, the lower band also lies within the bandgap in the 3-dimensional device. Here only the lower band can be observed possibly owing to the fabrication errors that separate the two bands with a large bandgap. Like the S = −2 IA-PhCWGs, the lower band has low transmittance in the Z-shaped bends. The Tav is 0.41.

To summarize, the experimental results clearly show a significant difference in the transmission properties among different domain-wall configurations. The waveguide modes in S = 1, S = −1 PhCWGs, and the upper band of S = −2 PhCWG have high bend-transmittance, which agrees well with the numerical calculation results. Our experimental results support our proposal that the bend-transmittance is dominantly determined by the domain-wall configuration.

Waveguide band classification

We have numerically and experimentally demonstrated high bend-transmission through 120-degree sharp bends for PhCWGs with various S regardless of the existence of the inversion symmetry. In addition, the high transmission appears regardless of the mode parity and the group velocity. To observe the correlation between S and the bend-transmittance more intuitively, we plot Tav against RFP for each simulation result in Fig. 6a. If S changes continuously, the waveguide bands will accordingly evolve in the bandgap, until they disappear into the bulk mode regions. Different bands can be traced to one another in this process before disappearing. We classify such bands into the same group as S changes from 3 to −2 (see Supplementary (7) for detailed explanations). Thus we can classify the investigated waveguide bands into four different groups. We label each band group with different colors in Fig. 6. The even mode of W1WG and the upper band of S = 2 glide-symmetric PhCWG belong to group 1 (green). The lower band of S = 2 glide-symmetric PhCWG and the even band of S = 1 PhCWG belong to group 2 (blue). The odd mode of S = −1 PhCWG and the upper band of S = −2 glide-symmetric PhCWG belong to group 3 (orange). Finally, the lower band of S = −2 glide-symmetric PhCWG belongs to group 4 (gray).

a Average bend-transmittance against F-P reflectivity for simulation results. The circles indicate the results of waveguide modes in IS-PhCWGs, and the triangles indicate that of IA-PhCWGs. Colors indicate the band classification. Black texts show the shifting parameters of each waveguide, where U indicates the upper band, and L indicates the lower band for a glide-symmetric interface. b Average bend-transmittance against shifting parameters for simulation and experiment results. Solid markers indicate the simulation results. Hollow markers indicate the experiment results.

Now we focus on the transmission properties of each band group. As shown in Fig. 6a, group 2 (blue) and group 3 (orange) have high bend-transmittance and low F-P reflectivity, and group 1 (green) and group 4 (gray) have low bend-transmittance and high F-P reflectivity. This shows that the band classification corresponds with the transmission property of the Z-shaped waveguide very well. In addition, each group includes waveguide bands of both IS-PhCWGs and IA-PhCWGs, meaning that the existence of inversion symmetry has no significant influence.

It is worth noting that when continuously changing S, groups 1 and 2 are connected at the BZ edge degeneracy point of the S = 2 PhCWG, and groups 3 and 4 are connected at the BZ-edge degeneracy point of the S = −2 PhCWG. Interestingly, a degeneracy point of glide-symmetric waveguides connects two different band groups having high and low transmissions.

Next, we summarize the Tav obtained in simulation and measurement in Fig. 6b. We plot Tav against the shifting parameters. Solid markers show the simulation results and hollow markers show the experiment results. The experiment results agree well with the simulation results, showing that group 1 and group 4 have low bend-transmittance, and group 2 and group 3 have high bend-transmittance.

The effect of circular polarization singularities

To account for the physical mechanism of the high bend transmission in these groups of waveguides, we propose a model shown in Fig. 7a, b. Suppose the light is linearly polarized at the mirror-symmetric line of a 120-degree bend (broken lines in Fig. 7a). Then, the polarization orientation differs across the line, and polarization mismatch occurs, which leads to a large modification of the field profile and may generate local resonances and high reflection. This mismatch may be resolved when the orientation of polarization is uncertain along the mirror-symmetric line. In Fig. 7b, the light is circularly-polarized at this line. Since there is no specific direction of the linear polarization for circularly-polarized states, changing the propagation direction by 120 degrees does not cause polarization mismatch. In fact, such states where the polarization direction is uncertain exist in various types of PhCWGs, and are called topological polarization singular points, including the circular polarization singularities (C-points or CPs) and vortex singularities (V-points or VPs)52,53,54,55 of the electric/magnetic fields. These singular points exhibit various topological properties and can be employed for controlling the propagation direction. For example, unidirectional excitation of waveguide modes can be realized by exciting the CPs29,42,53,54. It may be worth noting that they are based on vectorial topology of light, which is fundamentally different from the scalar topology discussed in valley photonics. We speculate that if these polarization singular points exist at the mirror-symmetric line, and the field intensity at this line is mostly concentrated at the singular points, the high bend transmission may appear. We have noticed that some recent works have demonstrated high bend-transmittance via S = −2 IS-PhCWGs, and explained the high bend-transmission as a result of the valley-photonic effect featured by phase vortices in the bulk lattice42,43. We note that their model is fundamentally different from the present model since our results cannot be explained by the bulk properties, as we have already emphasized.

a Schematic illustration of linear polarization causing low transmittance via the bend of a conventional W1WG, b Schematic illustration of polarization singularities causing high transmittance via the bend of an S = −2 IS-PhCWG (in the upper band). The red and blue arrows represent the directions of polarization. Black dotted lines indicate the connection interface of the 120-degree bend. c The simulation results of CP distributions in S = −2 IS-PhCWG. Red, green, and blue lines show the zero values of S1, S2, and S3, respectively. Black boxes show the location of CPs. Gray boxes show the location of VPs. Color maps show the amplitude of electric fields in the waveguide. Black dotted lines show the connection interfaces of a 120-degree bend. The normalized frequencies, the normalized amplitudes of the electric field, and the bend-transmittances are shown below each plot.

Here we examine this speculation by analyzing the polarization profile of the simulation results and investigating the distribution of CPs. We first investigate the S = −2 IS-PhCWG, whose large transmission contrast between the upper and lower waveguide band is intriguing yet poorly understood. In Fig. 7c, we plot the CP distributions in unit cells of S = −2 IS-PhCWG at several frequencies. To identify the location of CPs, we plot the zero-value isolines of Stokes parameters55,56. The crossing nodes of the S1 = 0 (red) andS2 = 0 (green) lines indicate C-points (CPs). The crossing nodes of the S1 = 0, S2 = 0, and S3 = 0 (blue) lines indicate VPs.

In Fig. 7c, the first three columns show the high-transmittance band, and the last two columns show the low-transmittance band. The high-transmittance band has CPs (black boxes) close to the mirror-symmetric interface (black broken lines). The calculated degree of polarization (S3/S0) is over 0.99 at each CP. The normalized electric field amplitude (∣E∣/∣E∣max) is over 0.5 at each CP. Bright CPs’ existence agrees with the high bend-transmittance. These CPs are located inside the air holes. As we change the frequency, we observe that these CPs gradually move away from the hole centers and disappear exactly at the degeneracy point.

Now we investigate the low-transmittance band. As shown in the fourth and fifth columns in Fig. 7c, the low-transmittance band has no bright CPs near the broken lines. There are only dark CPs in the silicon area where ∣E∣/∣E∣max is lower than 0.1. Instead, VPs (gray boxes) appear near the broken lines. The sudden disappearance of bright air-hole CPs is consistent with the abrupt change in bend-transmittance across the degeneracy point. The absence of bright CPs agrees with the low bend-transmittance throughout the lower band.

We have also investigated other domain-wall types of IS- and IA- PhCWGs (Supplementary Information (8). We have confirmed the existence of bright air-hole CPs in most of the high bend-transmission bands and their disappearance in the low bend-transmission bands. For the glide-symmetric S = 2 PhCWGs, we have also observed that CPs located inside the air holes disappear around the position where the bend-transmission abruptly decreases. These results suggest some correlation between the high bend-transmission and the existence of CPs near the mirror-symmetric line. Another important point is that for all the investigated domain walls, the CP distribution in IA- and IS- PhCWGs have no significant difference. This means that the inversion symmetry does not alter the CP properties. We admit that these arguments are still speculative because it is difficult to estimate the transmittance quantitatively from the distribution and brightness of CPs. We leave a more rigorous theoretical explanation to future works.

As a final remark, we would like to address the influence of breaking inversion symmetry on bend-transmissions. Notably, we have observed a marginal enhancement in bend-transmission for certain IA-PhCWGs when compared to IS-PhCWGs, as evidenced by both numerical calculations and experimental data. It is important to note that this modest variation should be distinguished from the primary transmission contrast discussed in this study. Nevertheless, there exists the possibility that this slight improvement can be attributed to the valley-photonic effect. However, it is currently beyond the scope of this study to conduct a quantitative analysis of this subtle difference with our waveguide design, and we leave it for future works. Since the recent works40,41 indicate that the suppression of the backscattering may occur in a slow light region with a small disorder, one needs to analyze this issue in sharp bends in a meticulous manner.

Discussion

In summary, we have investigated the bend-transmission in a series of triangular-lattice PhCWGs compatible with 120-degree sharp bends. We systematically investigated different domain-wall configurations by adjusting S for waveguides with and without the inversion symmetry. Our numerical and experimental results demonstrate that significantly high bend-transmission can be achieved for certain domain-wall types, including typical VPhCWGs. Surprisingly, the presence of the inversion symmetry does not affect the emergence of high bend-transmission, which contradicts the previous understanding of the VPhCWGs. Our findings provide new possibilities for achieving uniquely high bend-transmission in a broader range of PhCs, not restricted to VPhCWGs. Since bending loss is one of the serious issues for nanophotonic integrated circuits, this work carries significant implications for constructing flexible low-loss nanophotonic circuits. As an empirical explanation, we propose a band classification that links the high bend-transmission to specific groups of waveguide modes. Regarding the origin of the high bend-transmission, a preliminary study suggests that the abrupt change in bend-transmission is accompanied by the emergence or disappearance of topologically-protected CPs near the bending interface. Therefore, we speculate that the high bend-transmission phenomenon is related to the existence of CPs at the interface, whose behavior is mostly determined by the domain lattice configuration and is minimally influenced by the presence of the inversion symmetry. It remains possible that the observed slight difference in the bend-transmission between the PhCWGs with and without the inversion symmetry can be attributed to the suppression of backscattering due to the valley-photonic effect. However, an unambiguous conclusion requires more detailed and deliberate work. Our present work may pave the way to open up novel designs of nano-waveguides for low-loss nanophotonic integrated circuits and shed new light on the nature of valley-photonic properties.

Methods

Simulations

The thickness of the photonic slab is 220 nm. The lattice constant is 400 nm. The radii of circular air holes are 102 nm, and the length of one side of the triangular air holes is 277 nm. The area of each circular and triangular air hole is approximately the same. The simulations were conducted using finite element method in commercial software (COMSOL). We first calculated the three-dimensional (3D) photonic band structure (PBS) and then approximate the 3D PBS in two-dimensional (2D) models. In 3D calculation, the refractive index of silicon was 3.48. In 2D calculation, the effective refractive index of silicon was set to be 2.65 to keep the photonic bandgap within approximately the same wavelength range as the 3D results.

By connecting the bulk PhCs with an arbitrary interface, we could construct PhCWGs that support interface modes. The broken inversion symmetry that causes the coupling between the chirality of modes and valley DoF is the foundation of the valley-photonic explanation of high transmission in sharp bends. This explanation will remain valid if we observe low transmission in IS-PhCWGs and high transmission in IA-PhCWGs. Otherwise, if we observe relatively high transmission in some IS-PhCWGs or relatively low transmission in some IA-PhCWGs, we should consider other factors affecting the transmission other than inversion symmetry. For each domain-wall type in Fig. 1c, we constructed the IA-PhCWGs and the IS-PhCWGs. We connected domains constructed from patterns A and B to construct the IA-PhCWGs with broken inversion symmetry. We had numerically confirmed that the A-B and B-A type waveguides have no essential difference in their transmission properties. Here we set most of the IA-PhCWGs to be the A-B type interface for convenience. S = −1 IA-PhCWGs were exceptions and have a B-A type interface because the air holes overlap with each other at the A-B type interface. We calculated the light transmittance through a straight waveguide and a Z-shaped waveguide of the same length for each type of waveguide design. Details of the settings of the wave source are described in the Supplementary Information (1).

For each waveguide band, we calculated the average transmittance and estimate the reflectivity at bends from the amplitude of the F-P ripples. Given the reflectivity at each bend R, the transmittance through an F-P cavity is \(T=\frac{1}{1+F{(\sin \frac{\sigma }{2})}^{2}}\), where \(F=\frac{4R}{{(1-R)}^{2}}\) is the coefficient of finesse. F is estimated as F = Tmax/Tmin − 1, where Tmax and Tmin are the maximum and minimum transmittance in the single-mode region. Thus we can calculate R as \(R=\frac{F+2-2\sqrt{F+1}}{F}\). We call the calculated R the F-P reflectivity and use this value to evaluate the bend-transmission in addition to the average transmittance.

Undesirable mode conversions may occur if other waveguide modes or bulk modes are near the edge of the single-mode region. In addition, we disregarded the ultraslow light region near the mode edge where large reflection makes the analysis difficult. Thus, the actual frequency range where the transmittance can be accurately evaluated is slightly narrower than that calculated in the PBS. In our calculation, the frequency range in which the average transmittance and F-P reflectivity are calculated was set to be narrower than the single mode region of the waveguide band by 6 THz (0.08a/λ) when the lattice constant is 400 nm.

Fabrication and experiments

The PhCWGs were fabricated from an silicon-on-insulator wafer. The top silicon layer is 220 nm thick. The middle SiO2 layer is 3000 nm thick. The substrate silicon layer is 525 μm thick. The photonic crystal patterns were defined by electron-beam lithography, using ZEP-530 as resist. The resist layer patterns were transferred to the top silicon slab by inductively coupled plasma dry-etching. The air-bridge structure was formed by wet-etching the SiO2 layer with buffered hydrogen fluoride acid.

To measure the transmittance spectrum, light from a wavelength-tunable laser (Santec TSL-710) was launched into an input silicon waveguide with a width of 8 μm. The output intensity is 5 dBm. The silicon waveguide is connected with an appropriate taper to a silicon nanowire, which is 400–700 nm in width and 12.5 μm in length. Light was coupled to the PhC region via the silicon nanowire. The transmitted light is collected from an output silicon waveguide of the same design. The transmitted intensity was measured by a lightwave multimeter (Keysight 8163B). Due to fabrication errors, the transmitting wavelength ranges in most waveguides deviate from those predicted by the band calculation of a 3-dimensional waveguide. Therefore we determine the single-mode region directly from the transmission spectra. Considering that multi-modes can have relatively high transmission through a straight waveguide, we determine the cut-off wavelength of the single modes using the Z-shaped waveguide’s spectra. Suppose the peak transmitted intensity is Imax at wavelength λmax we defined the single-mode range as (λ1, λ2) where λ1 = max({λ∣λ < λmax, I(λ) < 0.1Imax}), and λ2 = min({λ∣λ > λmax, I(λ) < 0.1Imax}). For waveguide bands that have extremely low transmittance via 120-degree bends, like the upper band of S = 2 PhCWGs, we calculate (λ1, λ2) using the straight waveguides’ spectra in the same manner.

To eliminate the influences of insertion loss and coupling loss, we used the measured intensities of straight PhCWGs as the reference to calculate the average transmittance of the bent PhCWGs. We converted the transmitted intensities of the straight and bent waveguides into the linear scale (in milliwatts) and respectively calculated their average intensities in the single-mode region. The average transmittance of the bent waveguide was derived as the division of the bent waveguides’ average intensity and the straight waveguides’ average intensity. One may also calculate the relative transmittance of the bent waveguides before taking the average. However, due to fluctuations in the spectra, the bent waveguides’ intensities can be larger than that of the straight waveguides’ at some wavelengths, which is amplified in linear scale and brings unnecessary errors to the results. Most of the measured transmission spectra of the Z-shaped waveguides had complicated resonance ripples in addition to the simple pattern of the 30a cavity F-P resonance. Therefore it was difficult to calculate the FP reflectivity from the measured data in the same manner as in the numerical studies.

Data availability

The source data of waveguide transmittance in simulation and experiment, the processed average transmittance data, and Fabry-Perot reflectivity data have been deposited in FigShare (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.27490629).

References

Notomi, M. et al. Extremely large group-velocity dispersion of line-defect waveguides in photonic crystal slabs. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 253902 (2001).

McNab, S. J., Moll, N. & Vlasov, Y. A. Ultra-low loss photonic integrated circuit with membrane-type photonic crystal waveguides. Opt. Express 11, 2927–2939 (2003).

Kuramochi, E. et al. Disorder-induced scattering loss of line-defect waveguides in photonic crystal slabs. Phys. Rev. B 72, 161318 (2005).

Notomi, M., Nozaki, K., Shinya, A., Matsuo, S. & Kuramochi, E. Toward fJ/bit optical communication in a chip. Opt. Commun. 314, 3–17 (2014).

Vitale, S. A. et al. Valleytronics: opportunities, challenges, and paths forward. Small 14, 1801483 (2018).

Xiao, D., Liu, G.-B., Feng, W., Xu, X. & Yao, W. Coupled spin and valley physics in monolayers of mos2 and other group-vi dichalcogenides. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 196802 (2012).

Mak, K. F., McGill, K. L., Park, J. & McEuen, P. L. The valley hall effect in mos2 transistors. Science 344, 1489–1492 (2014).

Xiao, D., Yao, W. & Niu, Q. Valley-contrasting physics in graphene: magnetic moment and topological transport. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 236809 (2007).

Xu, X., Yao, W., Xiao, D. & Heinz, T. F. Spin and pseudospins in layered transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Phys. 10, 343–350 (2014).

Ren, Y., Qiao, Z. & Niu, Q. Topological phases in two-dimensional materials: a review. Rep. Prog. Phys. 79, 066501 (2016).

Dong, J.-W., Chen, X.-D., Zhu, H., Wang, Y. & Zhang, X. Valley photonic crystals for control of spin and topology. Nat. Mater. 16, 298–302 (2017).

Yang, Y., Jiang, H. & Hang, Z. H. Topological valley transport in two-dimensional honeycomb photonic crystals. Sci. Rep. 8, 1588 (2018).

Ma, T. & Shvets, G. All-si valley-hall photonic topological insulator. N. J. Phys. 18, 025012 (2016).

Shalaev, M. I., Walasik, W., Tsukernik, A., Xu, Y. & Litchinitser, N. M. Robust topologically protected transport in photonic crystals at telecommunication wavelengths. Nat. Nanotechnol. 14, 31–34 (2019).

Chen, X.-D., Zhao, F.-L., Chen, M. & Dong, J.-W. Valley-contrasting physics in all-dielectric photonic crystals: Orbital angular momentum and topological propagation. Phys. Rev. B 96, 020202 (2017).

Wu, X. et al. Direct observation of valley-polarized topological edge states in designer surface plasmon crystals. Nat. Commun. 8, 1304 (2017).

He, X.-T. et al. A silicon-on-insulator slab for topological valley transport. Nat. Commun. 10, 872 (2019).

Liu, J.-W. et al. Valley photonic crystals. Adv. Phys. X 6, 1905546 (2021).

Strasser, P. et al. Optimization of a 60∘ waveguide bend in inp-based 2d planar photonic crystals. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 25, 67–73 (2008).

Ntakis, I., Pottier, P. & De La Rue, R. M. Optimization of transmission properties of two-dimensional photonic crystal channel waveguide bends through local lattice deformation. J. Appl. Phys. 96, 12–18 (2004).

Tokushima, M., Kosaka, H., Tomita, A. & Yamada, H. Lightwave propagation through a 120° sharply bent single-line-defect photonic crystal waveguide. Appl. Phys. Lett. 76, 952–954 (2000).

Borel, P. I. et al. Topology optimization and fabrication of photonic crystal structures. Opt. Express 12, 1996–2001 (2004).

Ma, J., Xi, X. & Sun, X. Topological photonic integrated circuits based on valley kink states. Laser Photonics Rev. 13, 1900087 (2019).

Yamaguchi, T. et al. Gaas valley photonic crystal waveguide with light-emitting inas quantum dots. Appl. Phys. Express 12, 062005 (2019).

He, X.-T. et al. Topological polarization beam splitter in dual-polarization all-dielectric valley photonic crystals. Phys. Rev. Appl. 18, 044080 (2022).

Kumar, A. et al. Phototunable chip-scale topological photonics: 160 gbps waveguide and demultiplexer for THz 6G communication. Nat. Commun. 13, 5404 (2022).

Arora, S., Bauer, T., Barczyk, R., Verhagen, E. & Kuipers, L. Direct quantification of topological protection in symmetry-protected photonic edge states at telecom wavelengths. Light Sci. Appl. 10, 9 (2021).

Han, Y. et al. Design of broadband all-dielectric valley photonic crystals at telecommunication wavelength. Opt. Commun. 488, 126847 (2021).

Mehrabad, M. J. et al. Chiral topological photonics with an embedded quantum emitter. Optica 7, 1690–1696 (2020).

Yoshimi, H. et al. Experimental demonstration of topological slow light waveguides in valley photonic crystals. Opt. Express 29, 13441–13450 (2021).

Yoshimi, H., Yamaguchi, T., Ota, Y., Arakawa, Y. & Iwamoto, S. Slow light waveguides in topological valley photonic crystals. Opt. Lett. 45, 2648–2651 (2020).

Gao, Z. et al. Valley surface-wave photonic crystal and its bulk/edge transport. Phys. Rev. B 96, 201402 (2017).

Chen, Q. et al. Valley-hall photonic topological insulators with dual-band kink states. Adv. Opt. Mater. 7, 1900036 (2019).

Zhang, Z. et al. Broadband photonic topological insulator based on triangular-holes array with higher energy filling efficiency. Nanophotonics 9, 2839–2846 (2020).

Kang, Y., Ni, X., Cheng, X., Khanikaev, A. B. & Genack, A. Z. Pseudo-spin–valley coupled edge states in a photonic topological insulator. Nat. Commun. 9, 3029 (2018).

Zeng, Y. et al. Electrically pumped topological laser with valley edge modes. Nature 578, 246–250 (2020).

Du, Z., Chen, H. & Huang, G. Optimal quantum valley hall insulators by rationally engineering berry curvature and band structure. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 135, 103784 (2020).

Wang, Y., Zhang, W. & Zhang, X. Tunable topological valley transport in two-dimensional photonic crystals. New J. Phys. 21, 093020 (2019).

Xi, X., Ma, J., Wan, S., Dong, C.-H. & Sun, X. Observation of chiral edge states in gapped nanomechanical graphene. Sci. Adv. 7, eabe1398 (2021).

Arregui, G., Gomis-Bresco, J., Sotomayor-Torres, C. M. & Garcia, P. D. Quantifying the robustness of topological slow light. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 027403 (2021).

Rosiek, C. A. et al. Observation of strong backscattering in valley-hall photonic topological interface modes. Nat. Photonics 17, 386–392 (2023).

Yang, J.-K., Hwang, Y. & Oh, S. S. Evolution of topological edge modes from honeycomb photonic crystals to triangular-lattice photonic crystals. Phys. Rev. Res. 3, L022025 (2021).

Gao, Z.-X. et al. Observation of unidirectional bulk modes and robust edge modes in triangular photonic crystals. Laser Photonics Rev. 17, 2201026 (2023).

Yoda, T. & Notomi, M. Air-hole-type valley photonic crystal slab with simple triangular lattice for valley-contrasting physics. In Proc. Conference on Lasers and Electro-Optics, JTh2A.10 (Optica, formerly Optical Society of America, 2019).

Haldane, F. D. M. & Raghu, S. Possible realization of directional optical waveguides in photonic crystals with broken time-reversal symmetry. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 013904 (2008).

Raghu, S. & Haldane, F. D. M. Analogs of quantum-hall-effect edge states in photonic crystals. Phys. Rev. A 78, 033834 (2008).

Silveirinha, M. G. Chern invariants for continuous media. Phys. Rev. B 92, 125153 (2015).

Bernevig, B. A. & Hughes, T. L. Topological Insulators and Topological Superconductors (Princeton University Press, 2013).

Xiao, D., Chang, M.-C. & Niu, Q. Berry phase effects on electronic properties. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 1959–2007 (2010).

Ozawa, T. et al. Topological photonics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 91, 015006 (2019).

Chen, Q. et al. Photonic topological valley-locked waveguides. ACS Photonics 8, 1400–1406 (2021).

Burresi, M. et al. Observation of polarization singularities at the nanoscale. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 033902 (2009).

Young, A. B. et al. Polarization engineering in photonic crystal waveguides for spin-photon entanglers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 153901 (2015).

Söllner, I. et al. Deterministic photon–emitter coupling in chiral photonic circuits. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 775–778 (2015).

Lang, B., Beggs, D. M., Young, A. B., Rarity, J. G. & Oulton, R. Stability of polarization singularities in disordered photonic crystal waveguides. Phys. Rev. A 92, 063819 (2015).

Arora, G., Ruchi & Senthilkumaran, P. Full poincaré beam with all the stokes vortices. Opt. Lett. 44, 5638–5641 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (No. 20H05641(M.N.), 24K01377(Y.M.), 24H02232(Y.M.) and 24H00400(Y.M.)); and the Japan Science and Technology Agency (No. JPMJSP2106 (W.D.)). The authors would like to thank Takahiro Uemura for fruitful discussions, Masato Takiguchi for his help in the experimental setup, and Toshiaki Tamamura for his help in the fabrication process.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.N. conceived the ideas. M.N. and Y.M. supervised the project. M.N. and T.Y. proposed the theoretical background. W.D., M.O., and E.K. conducted the fabrication process. W.D. conducted the simulations and experimental measurements. Y.M. and T.Y. helped with simulations. W.D., T.Y., and M.N. wrote the manuscript with feedback from other authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Pedro David García, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dai, W., Yoda, T., Moritake, Y. et al. High transmission in 120-degree sharp bends of inversion-symmetric and inversion-asymmetric photonic crystal waveguides. Nat Commun 16, 796 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56020-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56020-8