Abstract

Despite vast data support in DNA methylation (DNAm) biomarker discovery to facilitate health-care research, this field faces huge resource barriers due to preliminary unreliable candidates and the consequent compensations using expensive experiments. The underlying challenges lie in the confounding factors, especially measurement noise and individual characteristics. To achieve reliable identification of a candidate pool for DNAm biomarker discovery, we propose a Causality-driven Deep Regularization framework to reinforce correlations that are suggestive of causality with disease. It integrates causal thinking, deep learning, and biological priors to handle non-causal confounding factors, through a contrastive scheme and a spatial-relation regularization that reduces interferences from individual characteristics and noises, respectively. The comprehensive reliability of the proposed method was verified by simulations and applications involving various human diseases, sample origins, and sequencing technologies, highlighting its universal biomedical significance. Overall, this study offers a causal-deep-learning-based perspective with a compatible tool to identify reliable DNAm biomarker candidates, promoting resource-efficient biomarker discovery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The identification of disease-specific DNA methylation (DNAm) biomarkers holds substantial clinical significance in human health, encompassing areas such as molecular mechanisms, risk factors, and early detection1,2. Several DNAm biomarkers have been employed clinically or made commercially available for early diagnosis of specific cancers3. The field of DNAm biomarker discovery is witnessing a significant accumulation of techniques and data. High-throughput microarray platforms like the Illumina Infinium BeadChip4,5 provide extensive coverage of DNAm measurements at CpG sites. Many public databases, such as The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) for cancer and Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) for Alzheimer’s disease (AD), employ these platforms to contribute plentiful DNAm microarray data. Therefore, the wealth of data collections deserves significant efforts to unlock its full potential in DNAm biomarker discovery, thereby creating extensive opportunities for advancements in medicine.

The prevalent workflow for DNAm biomarker discovery mainly includes initial data-based screening algorithms6,7,8,9 to yield a pool of candidates, intermediate wet lab experiments to provide additional measurement10 for iterative screening, and ultimate clinical validations for final identification (Fig. 1a). The data screening methods for candidate identification mainly involve statistical differential analysis and traditional regression models1. Statistical testing methods employ P value thresholds to select differential methylation sites or regions between diseased and normal sample groups11. Regularized regression models select sites with high importance weights and use regularization terms to control selection preference. Typical representative models include the least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (Lasso)12, elastic net (ENet)13, and sparse-group Lasso (SGLasso)14. Additionally, certain methods incorporate biological knowledge about DNAm. For example, Sun et al. considered the co-methylation phenomenon, where adjacent CpG sites often exhibit similar methylation states15. They proposed a network-constrained regularization model named penalized conditional logistic (Pclogit) to favor similar weights for sites within a gene16,17.

a Challenges of DNAm biomarker discovery. Current data-based screening methods may generate a less reliable candidate pool, due to confounding factors such as measurement noises and individual characteristics. This deficiency necessitates compensation through subsequent multistep and costly experiments, leading to the overall resource-intensive workflow. b Overview of the proposed causality-driven deep regularization (CDReg) framework that integrates causal thinking, priori guidance, and deep learning. The spatial-relation regularization aligns weight differences with spatial distances to ensure sites with close distances receive similar weights, thereby excluding the spatially isolated noise sites. The contrastive scheme pushes apart paired diseased-normal samples from the same subject to encourage selecting disease-specific differential sites rather than subject-specific ones. c Comprehensive performance evaluation in this study. The experiments include simulations and applications, and the latter involves microarray data from lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) tissue samples and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) blood samples, as well as WGBS data of prostate cancer (PC) tissue samples. The results demonstrate the comprehensive advantages of CDReg across accurate identification, biological significance, and inter-class discrimination.

These data-driven or priori-guided methods, used sequentially or overlappingly, have been widely applied in DNAm biomarker studies6,7,8,9,18,19. However, the pool of DNAm biomarker candidates generated by these methods tends to be less reliable, mainly caused by their limited causality due to neglecting confounding factors, especially measurement noise and individual characteristics. Such unreliable preliminary screening necessitates compensation through subsequent multistep and costly wet lab experiments with iterative steps, consequently decelerating the pace of research. Such resource-intensive workflow imposes implementation barriers for many potential researchers to utilize the existing valuable data, thus limiting the opportunities for more research (Fig. 1a). Therefore, a novel data-based screening method is urgently required to generate a reliable pool of DNAm biomarker candidates by effectively addressing the challenge of confounding factors.

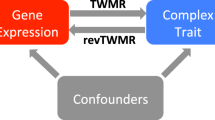

Deep learning technology, distinguished for its exceptional feature representation capability, has been widely applied20,21,22. The increasingly noticed concept of causality can further improve this by enabling the investigation of underlying causal features beyond superficial correlations23. Within the field of DNAm biomarker discovery, the ideal pools of candidate biomarkers should hold a consistent reliable correlation with the target disease and remain unaffected by confounding factors, potentially indicative of a causal relationship. Therefore, we integrate causal thinking, deep learning, and traditional priori-guided regularization to construct a Causality-driven Deep Regularization (CDReg) framework to ensure the reliability of the candidate pool during DNAm biomarker discovery workflow (Fig. 1b). It can reduce the search space for subsequent experimental stages, and ultimately enhance efficiency for overall workflow. Such reliability derives from the capability to address non-causal confounding factors. Specifically, a spatial-relation regularization term is designed to exclude spatially isolated sites caused by measurement noise and a deep-learning-based contrastive scheme is proposed to suppress subject-specific sites derived from individual characteristics (please refer to “Challenges, solutions, and evaluations” in Results for more details). Notably, our method is conceptually grounded in the principles of causality, yet it is not developed to directly recognize causality.

To validate the superiority of CDReg in the reliable identification of DNAm biomarker candidate pool, we conducted simulation experiments and real-world applications, involving microarray data from lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) tissues and AD blood samples and whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS) data of prostate cancer (PC) tissues (Fig. 1c). In simulations, CDReg accurately identified the gold standard sites. The applications in complex practice further highlight the dual advantages of CDReg in biological significance and discrimination, since the selected sites exhibited not only direct disease relevance as corroborated by antecedent biomedical investigations but also inter-class differentiation in cross-database independent testing. Additionally, the reasons for these advantages are revealed by the capability of CDReg to address confounding challenges from spatially isolated or subject-specific differential sites.

In summary, this study provides a compatible and universal tool for the data-based screening stage in DNAm biomarker discovery workflow. It pioneers an integration of causal thinking, deep learning, and priori guidance to solve challenges posed by confounding factors, thereby attaining a reliable pool of candidate biomarkers. The prospective application of this method has the potential to lessen the need for expensive and iterative experiments, thereby breaking down the long-standing resource barrier in DNAm biomarker discovery. It’s promising to establish a valuable link between the wealth of underexploited data and researchers facing limited resources, thereby maximizing the utility of both data and research potential to broaden the scope of resource-efficient research (Fig. 1a).

Results

Challenges, solutions, and evaluations

We propose the CDReg framework to identify a reliable candidate pool of DNAm biomarkers, which exhibit potential causal correlations with the disease rather than those affected by noise and individual characteristics. The reliability stems from the capacity to address particular challenges of confounding factors, involving three technological contributions (Fig. 1b and Fig. 2; see “Methods”): (1) a priori-guided spatial-relation regularization to mitigate the initial challenge of measurement noise confounding, (2) a deep contrastive scheme to address the challenge of individual characteristics, thereby further enhancing reliability, and (3) a contrast-guided shrinkage algorithm to solve the optimization issue of integrating these two strategies, thereby maximizing their efficacy.

The proposed CDReg can solve confounding factors of measurement noise (a) and individual characteristics (b) through the spatial-relation regularization and the contrastive scheme, respectively, with a contrast-guided shrinkage algorithm for integrating them. The difficulties in exclusion of spatially isolated sites and the influences of subject-specific sites on sample differences are further expounded in Supplementary Fig. 1.

Firstly, measurement noise can potentially generate spatially isolated differential sites, i.e., those display differences between the diseased and normal groups, but are not mirrored by their surrounding sites. Hence, they should be excluded. However, the exclusion faces detailed difficulties such as decreasing inter-site correlations with increasing distances24 (Supplementary Fig. 1a) and uneven site distribution25 (Supplementary Fig. 1b). To address this, we develop a spatial-relation regularization based on total variation26 to align the similarity of importance weights with the refined spatial correlation. Hence, isolated noise sites are eliminated and clustered discriminative sites are prioritized.

Secondly, individual characteristics, such as diet, exercise habits, and other diseases, can generate subject-specific differential sites, i.e., those display no differences between the diseased and normal samples from the same subject. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 1c, d, intra-class sample differences generally exceed inter-class ones. To handle this issue, we propose a contrastive scheme motivated by supervised contrastive learning27. Paired diseased-normal samples from the same subject, such as tumor and normal tissue samples or post- and pre-disease blood samples, are considered a natural randomized controlled trial from a causal view. They maintain the same subject-specific traits but show differences only at disease-specific differential sites1,28. Therefore, our contrastive scheme pushes apart their embeddings to amplify the weights of these disease-specific differential sites.

Thirdly, the integration of regularized regression and deep learning encounters the challenge of concurrent optimization of convex and nonconvex loss. A contrast-guided shrinkage algorithm is designed to utilize the nonconvex contrastive loss in the deep-learning-based contrastive scheme as guidance for the weight shrinkage in the regression model to facilitate iterative optimization.

Furthermore, we employ a sparse-group Lasso (SGLasso)14 model as a foundational component with grouped DNAm sites based on their gene associations, to yield a few effective sites within a limited number of crucial genes (see “Sparse-group Lasso (basis)” in “Method architecture” for more details). Ultimately, this foundational SGLasso model and the above-mentioned three technological innovations constitute the overall CDReg framework.

To comprehensively evaluate our proposed framework, we performed one simulation study and three real-world application studies on LUAD, AD, and PC (Supplementary Table 1). All the experiments illustrate the advantages of CDReg in addressing specific challenges to ensure its overall superiority, as reflected separately in each experiment. The simulation validates the remarkable quantitative performance of CDReg in identifying gold standard sites under controlled conditions. For practical applications, we use tissue samples from LUAD, a common and severe type of cancer, to illustrate the reliability of the candidate pool obtained by CDReg, including both biological reliability and inter-class discrimination. Such practical applicability of CDReg is further confirmed using blood samples from AD, a common neurodegenerative disease. This also highlights the clinical potential of CDReg in early disease diagnosis based on readily available blood samples. In addition to the above microarray data, CDReg has been applied to a WGBS dataset for PC patients and consistently demonstrates excellent performance to support the observations.

Simulation study

To quantitatively evaluate the effectiveness of CDReg in identifying reliable DNAm sites, we conducted simulation studies under two settings, where gold standard sites were present (Fig. 3a; please refer to “Simulation data generation” in Methods for details). The selection correctness can illustrate the overall performance of CDReg, largely attributed to its ability to exclude confounding sites.

a A schematic diagram for the weights and distributions of simulated DNAm sites, including truly effective sites, spatially isolated sites, subject-specific differential sites, and ineffective sites. b Feature selection correctness of different methods under two simulation settings. The digital values denote average value and the scatter points denote ten repetitions. The comparing methods contain four conventional feature selection methods, the proposed CDReg framework, and two ablated methods (without the spatial-relation regularization (w/o S) and without the contrastive scheme (w/o C)). The error bar is presented as mean value ± standard error of ten-time repetitions. The P values derived from the one-sided paired-sample T-test are listed on the right side. Vertical dashed lines denote hypothetical random performances for each metric. c Averaged normalized weights of subject-specific differential sites and isolated sites over ten repetitions on two simulation settings. Box plots indicate median (center line), upper and lower quartiles (box limits), 1.5× interquartile range from quartiles (whiskers), and outliers (points). d Weights of subject-specific differential sites and isolated sites in one of the repeated experiments. The x-axis of the heatmap denotes various DNAm sites, while the color blocks below the heatmap differentiate the groups (genes) to which these sites belong to. The numbers positioned beneath indicate the group indices. c, d The proposed CDReg framework demonstrates overwhelming advantages in both excluding subject-specific differential sites and isolated sites. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Selection correctness

We first evaluated the correctness of different methods in selecting significant sites by comparing the sites they assigned high weights to the simulated ground-truth sites. Specifically, the normalized importance weight of a DNAm site is regarded as the probability of identifying this site as a candidate biomarker. Hence, the DNAm site selection task is recast as a binary classification problem, to facilitate the application of common evaluation metrics. The area under the ROC curve (AUROC), area under the precision-recall curve (AUPRC), Accuracy, and Balanced Accuracy serve as evaluation metrics for selection correctness (see “Feature selection correctness” in the “Methods” section). As shown in Fig. 3b, under two simulation settings, all four evaluation metrics of CDReg have exceeded those of other comparing methods. This suggests the overall superiority of CDReg in correctly identifying pre-defined gold standard biomarkers.

Exclusion of confounding sites

The selection correctness of CDReg essentially comes from its advantages in addressing confounding factors, including (1) excluding isolated noise sites using the spatial-relation regularization and (2) excluding subject-specific differential sites using the contrastive scheme. As depicted in Fig. 3c, d, CDReg assigned the lowest weights for these confounding sites. Additionally, removing the spatial-relation regularization and the contrastive scheme from the complete framework resulted in both an increase in weights for confounding sites (Fig. 3c, d) and a decrease in selection correctness (Fig. 3b). These results suggest the targeted efficacy of CDReg in excluding confounding sites, thereby enhancing the selection reliability.

Application for lung adenocarcinoma

To assess the practical applicability and biomedical inspiration value of CDReg, we applied it to the tissue samples of a representative cancer, LUAD. As the most common and increasingly prevalent subtype of lung cancer29, increasing studies have revealed the role of DNAm in the development of LUAD. We utilized microarray DNAm data of LUAD from TCGA database. Tumor and normal tissue from the same subject were used as paired samples. The effectiveness of CDReg in discovering a reliable candidate pool of DNAm biomarkers is demonstrated from three aspects: biological reliability of the selected sites, their inter-class discrimination, and the ability to address challenges by encouraging disease-specific and clustered sites, which contributes to the former two aspects.

Gene function analysis

To explore the biological reliability, we investigate the corresponding gene functions of the selected sites, using existing biomedical literature as a reference. The top-ranked 25 DNAm sites selected by CDReg are listed in Fig. 4a. It was reported that Kir2.2 knockdown can induce senescence of cancer cells30. Voltage-gated potassium channels, particularly Kv1.1 and Kv1.3, are known to play a pivotal role in cancer progression, being expressed in various types of cancer cells31. Additionally, KCNQ1DN is thought to inhibit the growth of renal carcinoma cells32. Recent research indicated that the DNAm of EGFR acts as an epigenetic regulator in LUAD33. The gene CASC15 has been identified as a promoter of lung cancer34. These findings demonstrate a direct relevance between the identified candidate biomarkers and cancer, particularly lung cancer, thus highlighting the biological reliability of the proposed method.

a Top 25 CpG sites selected by the proposed method on LUAD data. Listed are the chromosomes (CHR), coordinates (MAPINFO), and genes, as well as BH-corrected P values derived from two-sided T-test between cancer samples and normal samples and the weights obtained by the model. Different colors distinct different genes. b Classification performance of reconstructed classification models on another GEO dataset based on the top-ranked 25 CpG sites. The error bar is presented as mean value ± standard error of ten-time repetitions. The P values derived from one-sided paired-sample T-test are listed on the right side. SVM support vector machine, RF random forest. c Comparison of the top 50 CpG sites and their corresponding genes with and without contrastive scheme (denoted by w C and w/o C, respectively). d A visualization of the contrastive embeddings that are compressed into a two-dimensional plane using Principal Component Analysis (PCA)71. The data points denote paired cancer (red) and paired normal (gray) samples at the start and end stages of training. e Euclidean distances between samples with different classes in the PCA space. Violin plots represent the kernel density distribution and the box plots inside represent the median (center line), upper and lower quartiles, and 1.5× the interquartile range (whiskers). The number of sample distances for all three groups are as follows: Paired-cancer-normal: n = 29, Paired Cancer and Paired Normal: n = 841, Individual Cancer and Individual Normal: n = 1293. f Visualization of a segment of clustered five CpG sites (their IlmnID are listed on the right) on the LUAD data. The horizontal axis represents the site coordinate, and the vertical axis represents the methylation level, the BH-corrected P value derived from a two-sided T-test, and the weight given by the proposed method. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

An overlap analysis of the top 25 DNAm sites identified by different methods is presented in Supplementary Note 1 with Supplementary Fig. 2 and Supplementary Data 1. It suggests that CDReg is capable of identifying a greater number of CpG sites that are strongly associated with lung adenocarcinoma.

Classification performance

To examine the reliability of selected biomarkers in differentiating between classes, we conducted an independent test on another dataset from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database and evaluated the classification performance of the selected sites. The top-ranked 25 DNAm sites were used to construct classification models. Specifically, the training set is the same as that used for biomarker discovery and the testing set is a 50% sampling without replacement of another GEO dataset (Supplementary Table 1). The sampling was repeated 10 times to evaluate the average classification performance. As shown in Fig. 4b, the sites selected by CDReg yield good classification performance (the best in the random forest classifier and the second-best in the support vector machine classifier), showing the competitive inter-class discrimination of these sites. Notably, SGLasso, which is comparable to our CDReg in disease relevance, exhibited suboptimal classification performance. DMP, which showed satisfactory classification performance, demonstrated limited disease specificity in Supplementary Data 1. This discrepancy highlights the advantage of CDReg in striking a balance between biological significance and classification performance.

Encouraging disease-specific sites

To demonstrate the reliability of CDReg in terms of addressing confounding challenges posed by individual characteristics, we compared the top-ranked 50 sites selected by CDReg with and without the contrastive scheme. The overlap and difference between the two sets, both at the site and gene levels, are displayed in Fig. 4c. Complete numerical values and associated diseases for each gene are provided in Supplementary Table 2. The genes JAZF1, RASGEF1A, and WIPI2, which are related to gastric cancer, papillary thyroid cancer, intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, and oral squamous cell carcinoma respectively35,36,37,38, are uniquely selected by CDReg without contrastive scheme (denoted by “w/o C”). In contrast, the genes SAMD4A and NgR3 which are related to lung cancer and nasopharyngeal carcinoma respectively39,40, are uniquely selected by the complete CDReg (denoted by “w C”), and they suggest a closer relevance to the target disease. A more comprehensive comparison is provided in Supplementary Note 2 with Supplementary Table 3. It shows segments of unreliable CpG sites and the weights assigned to them by various methods, and further underscores the effectiveness of CDReg in identifying disease-specific DNAm sites. Additionally, as shown in Fig. 4d, e, the distances between samples from different classes increase with the training process. These findings indicate that the contrastive scheme improves the reliability of CDReg by avoiding potential non-causal confounding factors associated with subject-specific characteristics.

Encouraging clustered sites

To demonstrate the reliability of CDReg in terms of addressing measurement noise challenges, we took a set of clustered sites as an example and visualized their locations, difference level between classes, and weights assigned by CDReg (Fig. 4f). The five CpG sites are closely located and are similarly discriminative, as illustrated by Benjamini-Hochberg41 (BH) corrected P values below 5e-3 and mean absolute differences above 0.03 between normal and cancer groups for each site. The CDReg framework assigns similar weights to these sites (ranging from 0.181 to 0.203), suggesting that spatial-relation regularization effectively aligns the similarity of site weights with the correlation based on spatial distances. Additionally, Supplementary Note 2 with Supplementary Table 3 provides additional evidence of CDReg’s efficacy in excluding spatially isolated sites. Thanks to this characteristic, CDReg can reduce measurement noise in DNAm biomarker discovery to facilitate more reliable selection.

Exploration for Alzheimer’s disease

In this section, we seek to explore potential AD DNAm biomarkers in peripheral blood using the ADNI database. Although AD is the most prevalent neurodegenerative disorder with much attention paid to its DNAm variations, the peripheral blood remains relatively unexplored. This is clinically important for early detection due to the accessibility of peripheral blood. The samples collected from the same subjects before and after the illness were used as paired samples for the contrastive scheme. Similar to the previous section, biological reliability was validated through gene function analysis, while inter-class discrimination was evaluated according to the classification performance of selected sites.

Gene function analysis

To explore the biological reliability of CDReg, especially derived from the efficacy in addressing confounding factors, we conducted gene function analysis for the selected sites. We compared the selection results of our proposed CDReg framework and its fundamental SGLasso model without spatial-relation regularization and contrastive scheme. Among the top-ranked 50 sites, the CDReg and SGLasso methods share 8 sites, with no overlap with other methods (Fig. 5a). The top-ranked 15 sites selected by CDReg and SGLasso are listed in Fig. 5b, with specific numerical values provided in Supplementary Table 4. Among these sites, those ranked highest by CDReg are concentrated in the AD-linked AGRN gene42, reflecting the weight smoothing of closely located sites due to spatial-relation regularization. The SGLasso model also selected sites on the AGRN gene. However, other sites selected uniquely by SGLasso, but not by CDReg, are mostly indirectly related or unrelated to AD. For instance, T1R3 acts as a member of candidate taste receptors43. The PLC(eta)2 gene is reported to be important for the biological neuronal network in the postnatal brain44, while the PRDM16 gene is suggested to control the cortical neuron position45. The CAMTA1 gene variants are implicated in episodic memory performance46. The PAX7 gene is identified as a muscle regulatory protein to orchestrate the myogenic process47. A recent study implicates S6K1 dysregulation as a molecular mechanism underlying synaptic and memory deficits in AD48. By contrast, the genes associated with most of the sites selected by CDReg have direct links to AD, such as ALDH1L149, GABRA150, and CRYAA51. Additionally, CRYBA2 is related to retina injury52, and overexpression of TFDP1 is associated with dystonia53, also showing certain connections to AD. Generally, CDReg tends to select sites directly associated with AD, while avoiding misidentifying sites related to other diseases, highlighting the pivotal role of the contrastive scheme, which contributes to the overall reliability of DNAm biomarker discovery.

a An UpSet plot to visualize the overlaps of the 50 top-ranked CpG sites obtained by different feature selection methods. DMRcate is skipped since it has a large number of sites with equivalent rankings. b Top-ranked 15 CpG sites selected by CDReg and SGLasso on AD data. Listed are the chromosomes (CHR), coordinates (MAPINFO) and genes, as well as BH-corrected P values derived from two-sided T-test between cancer samples and normal samples and the weights obtained by the two methods. In the IlmnID column, DNAm sites exclusively within the top 15 of SGLasso rankings are denoted in purple and those exclusively within the CDReg top 15 in red, while those appearing in the top 15 of both rankings are highlighted in gray. The Gene column is colored in a similar way. c Accuracies of support vector machine with increasing number of CpG sites selected by different methods. d Cumulative sum of the standard deviations of accuracy for the top 15 DNAm sites across ten repeated experiments. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Classification performance

To further validate the inter-class discrimination, as another aspect of reliability of the selected DNAm sites, we assessed their classification performance. The data was divided into training and testing sets using an 80/20 split ratio, and the results of 10 random splits were reported as the number of sites increased. As shown in Fig. 5c, CDReg consistently achieves high classification performance, with an accuracy of 0.725 for the top 15 ranked sites. SGLasso and DMRcate show competitive performance, and SGLasso briefly outperforms CDReg at eight sites, possibly due to their overlap of three sites out of top eight sites, with SGLasso’s eighth site being ranked first by CDReg (Fig. 5b). However, in Fig. 5d, CDReg demonstrates the most stable classification performance across ten repetitions, with the lowest cumulative standard deviation in accuracies for the top 15 sites, in contrast to the highest variability shown by SGLasso. This can be attributed to its proficiency in filtering out isolated noise sites and prioritizing disease-specific sites.

Extension to WGBS data of prostate cancer

Although the proposed CDReg was initially developed to harness the wealth of existing microarray data to further human health research, it can be also applicable to other platforms, such as high-precision next-generation sequencing. Technology advancements are yielding a growing body of novel DNA methylation datasets, highlighting the expansive potential applications of CDReg. We conducted a validation experiment on a WGBS dataset for a prostate cancer cohort, which reaffirmed the superiority of CDReg. Experimental results and discussions can be found in Supplementary Note 3, accompanied by Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Data 2.

Discussion

The wealth of DNAm microarray data available from well-established databases offers significant opportunities for DNAm biomarker discovery. For example, Xu et al10. firstly performed a statistical analysis based on liver cancer samples from TCGA and healthy human blood leukocyte samples from GEO to identify 1000 candidate markers, then designed padlock probes for new methylation detection data, and finally used the intersection of feature selection results from two methods as the final biomarkers to construct a hepatocellular carcinoma diagnosis model. Although such a multi-stage workflow can attain good results, it may demand high costs and long development cycles. The reason is that the unreliable DNAm biomarker candidates in the early stage, which lack causal correlation with the target disease, may give inappropriate direction for subsequent experimental phases. The difficulty of implementing these resource-intensive workflows not only hampers the full exploitation of valuable existing data but also impedes potential researchers with constrained resources from engaging in this field.

To achieve reliable DNAm biomarker discovery, we develop an intelligent screening framework termed CDReg. In the foreseeable future, the proposed framework might help to dismantle resource barriers and forge new links between underutilized data and potential researchers, thereby opening up research horizons for more large-scale, low-cost, and short-cycle commercial projects or clinical research.

Technologically, the CDReg framework preserves the foundation of traditional regularized regression models, utilizes prior knowledge to improve correlation modeling for noise reduction, and incorporates advanced deep learning and causality theory to further mitigate the impact of individual characteristics. Hence, it can discover reliable DNAm sites that possess putative causal correlations with the target disease, rather than those that merely exhibit spurious discriminations.

The most notable technological contribution of CDReg is the two innovations (i.e., a spatial-relation regularization and a contrastive scheme) that effectively exclude two major non-causal confounding factors (i.e., measurement noise and individual characteristics). On the one hand, inevitable measurement noise may lead to the inclusion of isolated sites that disrupt micromesh spatial correlation into the candidate pool. A spatial-relation regularization is designed for encouraging clustered sites and excluding isolated ones, which is verified by the weights assigned to these two types of sites (Figs. 3c, d, 4f). On the other hand, individual characteristics may generate subject-specific sites that mask expected disease-specific ones, especially in cases of biased sample selection1,28,54. For example, if the lung cancer patients in the data samples for the biomarker discovery phase are inclined to smoke, the smoking-related biomarkers may be incorrectly identified as lung cancer biomarkers. This can result in false positives during application, where healthy smokers are wrongly diagnosed as cancerous55. A contrastive scheme is proposed to exclude these subject-specific differential sites while encouraging disease-specific ones. The effectiveness is proved by the assigned weights (Fig. 3c, d) in simulations, as well as the biological function investigation (Figs. 4c, 5b, Supplementary Tables 2–4, and Supplementary Data 1–2) and sample difference analysis (Fig. 4d, e) in applications. These two components work in an integrated and progressive manner to ensure the reliability of the ultimate candidate pool.

Another technological contribution is the optimization algorithm termed contrast-guided shrinkage. It guarantees the perfect integration of the aforementioned two components, by incorporating the solutions of nonconvex contrastive loss into the convex optimization shrinkage process through a mathematical approximation. This process can be easily implemented using automatic differentiation engines available in various mature machine learning libraries.

More importantly, the proposed framework demonstrates excellent practical applicability in biomedical research inspiration and early disease diagnosis. In all application experiments, the selected DNAm sites hold close biological and pathological relationships with the target disease, meanwhile showcasing best or competitive classification performance. Certain candidate DNAm biomarkers, such as KCNQ1DN in LUAD experiments and CRYBA2 in AD experiments, are underexplored. Perhaps they deserve more biological or medical research. More importantly, the satisfactory performance of CDReg on AD peripheral blood provides optimism for further research into the early diagnosis of AD. Early diagnosis using easily accessible blood samples is clinically significant since it facilitates timely treatment to slow disease progression, thereby improving patients’ quality of life and reducing societal burden. Moreover, extended experiments on WGBS data demonstrate the potential of our CDReg framework to be applied to advanced emerging DNA methylation sequencing techniques.

Some mathematical modeling methods account for individual characteristics as random effects when given case-control paired samples16,17,56. However, these methods may not be expressly designed for feature selection tasks and can encounter intractable issues when a subject provides only one individual sample. In practical scenarios, procuring paired samples from the same subject across different classes can be challenging. Nevertheless, our CDReg framework can effectively reduce the impact of confounding feature interference even with a limited number of paired samples within the training set. Fundamentally, CDReg necessitates the inclusion of paired samples, but does not require a complete set of pairs, thus significantly lowering the data acquisition demands. Such a flexible mixture of both individual samples and case-control paired samples is more commonly encountered in practice.

A limitation of the proposed CDReg framework is the need for task-specific configuration of hyperparameters (see Eq. (10) in Methods). Nevertheless, such flexible hyperparameters allow for the adjustments of the strength of each loss term to facilitate effective collaboration. For instance, in situations with limited paired samples, intensifying the contrastive scheme can enhance the utilization of implicit matching relationships to reduce the adverse effects of individual characteristics. Furthermore, parameter sensitivity experiments reveal that a ± 10% variation in the tuning coefficients does not significantly affect the feature selection accuracy (Supplementary Fig. 4), showing little impact of this limitation.

This study has confirmed the efficacy of the proposed CDReg method using DNAm microarray data and WGBS sequencing data derived from human tissue and peripheral blood samples. Future research will extend to a broader range of sample sources and sequencing techniques. The exploitation of easily accessible, non-invasive samples, such as nasal mucus and urine, holds promise for facilitating the widespread adoption of early cancer screening protocols.

The proposed methodology could potentially be generalized or inspire approaches in various biomarker discovery fields. The issues of individual variability are ubiquitous in biomarker discovery, suggesting the generalizability of the contrastive scheme. Moreover, the spatial-relation regularization can be adapted to other bioinformatics areas that exhibit patterns analogous to co-methylation.

Methods

Preliminary

Let \(\left({\boldsymbol{X}},{\boldsymbol{y}}\right)\) represent a training data set, where \({\boldsymbol{X}}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{n\times d}\) denotes a DNAm matrix containing \(n\) samples and \(d\) DNAm sites, and \({\boldsymbol{y}}\in {\left\{\mathrm{0,1}\right\}}^{n}\) denotes the corresponding class label vector. For the m-th sample denoted by \({\boldsymbol{X}}\left[m,:\right]\) (\(m\)=\(1\),…,\(n\)), a value of \({y}_{m}\) = 0 represents normal control, while a value of \({y}_{m}\) = 1 represents diseased case. The total of \(n\) samples include \(p\) pairs of diseased-normal samples. The DNAm sites are divided into \(G\) groups according to their respective genes, with the g-th group containing \({d}_{g}\) sites (\({\sum }_{g=1}^{G}{d}_{g}\) = \(d\)), then the matrix \({\boldsymbol{X}}\) can be divided into column blocks as \({\boldsymbol{X}}=\left[{{\boldsymbol{X}}}_{1};\ldots ;{{\boldsymbol{X}}}_{G}\right]\), where \({{\boldsymbol{X}}}_{g}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{n\times {d}_{g}}\). A vector \({\boldsymbol{c}}\) denotes the coordinates of those DNAm sites, where \({{\boldsymbol{c}}}_{g}[i]\) denotes the coordinate of the i-th site in the g-th group.

In this study, the discovery of DNAm biomarkers is approached as a feature selection task based on a least-squares regression model with the following foundational objective function:

This model aims to optimally fit the predictors (DNAm sites) to an outcome (class label) by using corresponding weights \({\boldsymbol{\beta }}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{d}\), and \({\mathcal{R}}\) denotes the regularization terms for particular goals of feature selection. The weight magnitude, as determined by the absolute value \(\left|{\beta }_{i}\right|\), indicates the importance of each predictor. Hence, a small number of sites characterized by the largest \(\left|{\beta }_{i}\right|\) values can be selected as candidate DNAm biomarkers.

Simulation data generation

The simulated DNAm data comprised 3000 sites that are divided into 30 groups (\(G\)= 30, \(d\)= 3000). These groups (genes) contain 10 groups with a size of 150, 10 groups with a size of 100, and 10 groups with a size of 50. Following the approaches in refs. 16,57, the methylation level of the g-th group of sites in the m-th sample is calculated as

where \({s}_{1}\) = 4.0 and \({{\mathcal{N}}}_{{d}_{g}}\left({{\boldsymbol{\pi }}}_{g},{{\boldsymbol{\Sigma }}}_{g}\right)\) denotes a multivariate normal distribution with \({{\boldsymbol{\pi }}}_{g}\) as mean and \({{\boldsymbol{\Sigma }}}_{g}\) as covariance. We aimed to model the inherent spatial correlation of DNAm sites, characterized by the decrease in inter-site correlations with increasing distances15,24,58, using two approximation settings due to the lack of a precise definition. Additionally, diverse simulation settings help to highlight the universal efficacy of our proposed method. The following two settings were considered:

Here, \({s}_{2}\) = 0.1, \(\rho\)= 2.0, \({{\bf{I}}}_{{d}_{g}}\) denotes an identity matrix with length \({d}_{g}\), and \({\sigma }_{g}\) denotes the standard deviation of coordinate intervals within the group (See Supplementary Note 4 with Supplementary Fig. 5 for more details). The intervals between site coordinates were sampled from a uniform distribution ranging from 5 to 200, i.e., \({{\boldsymbol{c}}}_{g}[i+1]-{{\boldsymbol{c}}}_{g}\left[i\right]\sim {\mathcal{U}}\left(5,\,200\right)\).

The 10% of the clustered sites in each effective group with coordinates in the middle are set as truly effective sites, and their weights (\({\boldsymbol{\beta }}\)) are non-zero. Among the 10 genes with the same group size, the weights of truly effective sites in 3 genes are \(1/\sqrt{50}\) and those in the other 3 genes are \(-1/\sqrt{50}\); while the sites in the remaining 4 genes are all ineffective so that their weights are all zero.

The 2% isolated sites are separated by at least 4 sites and are randomly distributed up- and down-stream 10 sites away from the effective clustered sites. The symbols (positive or negative) are randomly selected while the absolute values are still \(1/\sqrt{50}\). Although the isolated sites have non-zero weights, they are not truly expected to be selected.

Additionally, some ineffective sites are distinguishable among the partial population, which means they are so-called subject-specific sites. Specifically, among the 12 ineffective genes, three genes (each has a group size of 150, 100, and 50, respectively) are selected and 10% of clustered sites in them are randomly selected as subject-specific sites. Their weights are zero for paired samples while are \(\pm 1/\sqrt{50}\) for other individual samples. A matched pair of samples simulated the cancerous and normal tissue from the same patient, and the subject-specific sites cannot distinguish these pairs, thus they should not be selected.

In general, 180 clustered sites with non-zero weights are gold standard sites; 36 isolated sites and a few subject-specific sites (which cannot be counted due to randomness) should not be selected, although their weights are not zero. Given the coefficients \({\boldsymbol{\beta }}\), the class labels \({\boldsymbol{y}}\) were simulated based on a linear regression model with Gaussian noise: \({\boldsymbol{y}}={{\bf{1}}}_{\left\{{\boldsymbol{X}}{\boldsymbol{\beta }}+{{\boldsymbol{\beta }}}_{0}+{\boldsymbol{\varepsilon }} > 0\right\}}\), \({\boldsymbol{\varepsilon }}{\mathcal{\sim }}{\mathcal{N}}(0,{\rm{std}}\left({\boldsymbol{\beta }}\right)/10)\), where \({{\boldsymbol{\beta }}}_{0}\) is an offset that balances the two class labels. Totally 500 samples were generated, including 250 samples without subject-specific sites and 125 pairs of samples with subject-specific sites within each pair (i.e., \(n\)= 500 and \(p\)= 125). The data generation process was randomly repeated ten times, with the experiments being conducted in accordance with each repetition.

Medical data collection and preprocessing

We conducted application experiments on DNAm biomarker discovery for lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD), Alzheimer’s disease (AD), and prostate cancer (PC).

In the LUAD experiments, DNAm microarray data from TCGA-LUAD was used as a training set, and data with series number GSE66836 from GEO was used for cross-dataset independent testing. The cancerous and normal tissue samples from the same subject were paired together. The used microarray is the Illumina Infinium HumanMethylation450 beadchip4, covering ~450,000 CpG sites. The data underwent several preprocessing steps. Firstly, probes from the X and Y chromosomes were removed to prevent sex bias. Then, CpG sites and samples with a missing ratio exceeding 30% were deleted, and the remaining missing values were imputed using the EMimpute_array algorithm from the LSimpute software59. To normalize the different methylation distributions and dynamic ranges of two types of designed probes in the beadchip, the Beta MIxture Quantile dilation (BMIQ)60 normalization method was employed. Then, sites with a T-test P value higher than 0.005 were filtered out. Additionally, the sites were required to correspond to a single gene that contains at least 20 sites.

The experimental data in AD experiments was downloaded from the repository of the ADNI study. The samples collected from a subject before and after the disease onset, at different time points, were used as matched pairs. DNA methylation levels were measured using the Illumina HumanMethylation EPIC beadchip5, covering ~866,000 CpG sites. The preprocessing pipeline adheres to the default procedures provided by the ChAMP R package61, which includes the removal of sex chromosome sites and normalization accounting for probe type differences. Then, sites with a T-test P value higher than 0.05 were filtered out. The sites were required to correspond to a single gene that contains at least 5 sites.

The WGBS DNA methylation data for PC was sourced from a previously published study named Chinese Prostate Cancer Genome and Epigenome Atlas (CPGEA)62. It comprises tumor samples and non-cancerous matched healthy prostate tissue from patients who underwent surgical treatment, providing paired samples for analysis. The initial preprocessing produced data in Bed format, which was downloaded for further processing. The first step involved merging the individual sample files into a matrix, analogous to array data. Only CpG sites with a sequencing depth of at least 20 were selected to ensure measurement reliability. Due to the vast number of CpG sites, we selected Chromosome 20 as a representative example for experiments. Subsequent steps were similar to those used for LUAD data.

Detailed descriptions of these datasets are provided in Supplementary Note 5. The specific preprocessing steps, including the rationales and implementations, can be found in Supplementary Note 6. Characteristics of the processed datasets are presented in Supplementary Table 1.

Method architecture

The proposed causality-driven deep regularization (CDReg) framework comprises four main components (Fig. 2c): (1) a foundation SGLasso model, (2) a spatial-relation regularization term to exclude spatially isolated sites caused by measurement noise, (3) a contrastive scheme to exclude subject-specific sites caused by individual characteristics, and (4) a contrast-guided shrinkage algorithm to address fusion issue between convex regression (involving SGLasso and spatial-relation regularization) and the nonconvex contrastive loss (involving contrastive scheme).

Sparse-group lasso (basis)

We adopted sparse group lasso (SGLasso)14 as the foundational model for our framework, because its mathematical assumptions align with the requirements for DNAm site discovery and SGLasso has been effectively utilized in bioinformatics analyses.

DNAm site discovery entails identifying a small number of key sites that are highly correlated with the disease-normal classes. These sites tend to be concentrated within a few genes (groups), which often share similar biological functions. From a mathematical perspective, the optimal solution to this problem should embody the principles of both inter-group and intra-group sparsity. Inter-group sparsity implies that only a few groups contain any non-zero coefficients, whereas intra-group sparsity signifies that within these groups, the number of non-zero coefficients is also limited.

To achieve this, we organized the DNAm sites by their respective genes and applied the SGLasso model. It is a regularized linear regression model that adopted L21 and L1 penalties to encourage inter-group and intra-group sparsity, respectively. The objective function is as follows:

This model has demonstrated efficacy in various applications, including the diagnosis of colitis and recurrence classification of breast cancer from gene expression data14, and the age prediction based on DNAm sites63. Building upon this foundation, we incorporate the spatial-relation regularization and contrastive scheme to enhance the identification of candidate DNAm site.

Spatial-relation regularization

The total variation was originally proposed as a regularization method for image denoising26. As a weighted version variant of it, the proposed spatial-relation regularization utilizes the degree of alignment between the weight difference and the spatial correlation to guide the smoothing of the weights. The mathematical expression is as follows:

where \({{\boldsymbol{S}}}_{g}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{{d}_{g}\times {d}_{g}}\) denotes the spatial correlation matrix, with each element calculated as follows:

The sites with shorter inter-site distances have larger Gaussian correlation (\({{\boldsymbol{S}}}_{g}\left[i,j\right]\)), so that minimizing this spatial-relation regularization leads to smaller weight differences between the two sites (\({({{\boldsymbol{\beta }}}_{g}\left[i\right]-{{\boldsymbol{\beta }}}_{g}\left[j\right])}^{2}\)). Hence, spatially isolated sites are excluded. Specifically, those sites are discriminative (with larger weight amplitude), but their adjacent sites lack discrimination (with weight approaching zero). It is noteworthy that \({\rm{SRR}}\left({{\boldsymbol{\beta }}}_{g};{{\boldsymbol{S}}}_{g}\right)\) is a smooth and convex function with respect to \({{\boldsymbol{\beta }}}_{g}\), allowing for an efficient model solution using block-coordinate gradient descent64 without significant computational overhead.

Contrastive scheme

Subject-specific DNAm sites such as those associated with other unrelated diseases in certain populations, may interfere with searching for discriminative sites that are truly relevant to the target disease. Therefore, a contrastive scheme is proposed to push apart paired samples from the same subject yet belong to opposite classes, which means they have common subject-specific characteristics, thereby avoiding selecting subject-specific spuriously discriminative sites.

Two samples with opposite labels collected from the same subject constitute a contrastive sample pair and are projected into the embedding space using a mapping denoted as \({{\mathcal{E}}}_{{\boldsymbol{\theta }}}\). The embedding of a sample \({{\boldsymbol{x}}}_{m}\) can be calculated as \({{\boldsymbol{z}}}_{m}={{\mathcal{E}}}_{{\boldsymbol{\theta }}}\left({{\boldsymbol{x}}}_{m}{\boldsymbol{\beta }}\right)\). The objective of the contrastive scheme is to maximize the difference between the embeddings of paired samples. Following the terminology of supervised contrastive learning27, the contrastive loss is defined as:

where \(\tau \in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{+}\) is an artificial temperature constant, and \(\circ\) denotes the inner (dot) product, M denotes the index set of subjects with matching sample pairs in a given dataset, and \({M}_{m}^{+}\) and \({M}_{m}^{-}\) denote the diseased and normal sample sets of the m-th subject, respectively. Minimizing contrastive loss implies minimizing the inner-product similarity between contrastive pairs. Consequently, the subject-specific common characteristics between case and control samples for each subject can be excluded.

Although the contrastive loss term in the proposed model is similar to that in original supervised contrastive learning, it must be declared that it is not a direct rigid application, but rather has a significant distinction. The original contrastive learning aims to learn well-embedded features that are beneficial for downstream tasks. By contrast, the contrastive scheme in this study serves as a guide for the feature selection process in model optimization. This guidance implicitly explores the features that exhibit differences between paired case-control samples and assigns appropriate weights to emphasize these features.

Entire model

Our proposed method, CDReg, builds upon the SGLasso model and incorporates a spatial-relation regularization constraint and a contrastive scheme to guide the optimization of the solution objective, namely the weight vector \({\boldsymbol{\beta }}\). Therefore, the loss function of CDReg is formulated as follows:

where \({\lambda }_{1}\), \({\lambda }_{2}\), \({\lambda }_{S}\), and \({\lambda }_{C}\) are predefined hyperparameters that control the trade-off between different terms.

Each component synergistically aids in the identification of reliable DNAm biomarker candidates that have a stronger causal association with the disease phenotype. Specifically, the L1 and L21 norms from SGLasso are designed to select a sparse set of influential DNAm sites within a limited number of key genes from a vast array of sites. The spatial-relation regularization, informed by biological prior knowledge, seeks to discover clusters of effective sites in close proximity rather than isolated ones, mitigating the effects of potential measurement noise. The contrastive scheme, inspired by randomized controlled trials in causal reasoning, aims to separate samples from the same subject but different classes in the latent space, thereby avoiding the selection of differential sites influenced by individual characteristics.

The interaction of these components is manifested in their collective role in determining the weight \({\boldsymbol{\beta }}\). The optimization process builds on the strategy employed by SGLasso, modified to incorporate the spatial-relation regularization, and includes the differentiation of the contrastive loss term. Details on the optimization process are provided in the following subsection.

Contrast-guided shrinkage

To address the nonconvexity problem of the contrastive loss, we proposed a contrast-guided shrinkage algorithm (see Supplementary Note 7 for the pseudocode). Firstly, the nonconvex contrastive loss is approximated to a differentiable quadratic function using a majorization trick65. Then the weights of the regression model (\({\boldsymbol{\beta }}\)) are iteratively updated by the outer and inner loops following the SGLasso solution. In the outer loop, the contrastive group shrinkage criterion is evaluated to determine whether to preserve a feature group, while in the inner loop, the contrastive individual shrinkage criterion is applied to update each feature weight in the remained group. Meanwhile, the parameters of deep contrastive mapping (\({\boldsymbol{\theta }}\)) is updated through gradient descent.

At the t-th iteration, the contrastive loss \({L}_{\text{C}}\left({\boldsymbol{\beta }};{\boldsymbol{\theta }}\right)\) is approximated by a quadratic surrogate \({L}_{C}^{S}\left({\boldsymbol{\beta }};{\boldsymbol{\theta }}\right)\).

where \(\Delta {\boldsymbol{\beta }}={\boldsymbol{\beta }}-{{\boldsymbol{\beta }}}^{t}\), \({\nabla }_{{\boldsymbol{\beta }}}\) denotes the gradient with respect to \({\boldsymbol{\beta }}\), and \({\alpha }_{t}\) is a scalar that satisfies

In practice, \({\alpha }_{t}\) is appropriately initialized and then incrementally enlarged through multiplication by a constant \(\gamma\) > 1.0, until Eq. (12) is satisfied. Based on the second-order Taylor expansion, a reasonable estimation of \({\alpha }_{t}\) is \(\text{tr}({\nabla }_{{\boldsymbol{\beta }}}^{2}{L}_{C}({{\boldsymbol{\beta }}}^{t};{{\boldsymbol{\theta }}}^{t}))\), which denotes the trace of the Hessian matrix. To avoid costly computations of second-order derivatives, \({\alpha }_{t}\) is initialized as \({\left\Vert{\nabla }_{{\boldsymbol{\beta }}}{L}_{C}({{\boldsymbol{\beta }}}^{t};{{\boldsymbol{\theta }}}^{t})\right\Vert}_{2}\), which is the first-order Gaussian-Newton approximation.

According to the critical point theory of convex optimization, the optimal value of \({{\boldsymbol{\beta }}}_{g}\) is \({\boldsymbol{0}}\) if and only if \({\boldsymbol{0}}\in {\partial }_{{{\boldsymbol{\beta }}}_{g}}{F}^{S}\left({\boldsymbol{\beta }};{\boldsymbol{\theta }}\right)\vert_{{\boldsymbol{\beta }}_{g}={\boldsymbol{0}}}\), where \({\partial }_{{{\boldsymbol{\beta }}}_{{\boldsymbol{g}}}}\) denotes the sub-gradient operator with respect to \({{\boldsymbol{\beta }}}_{g}\) and \({F}^{S}\left({\boldsymbol{\beta }};{\boldsymbol{\theta }}\right)\) is the new loss function after surrogating contrastive loss. Then, the optimal condition can be calculated as follows:

where \({{\boldsymbol{\beta }}}_{-g}\) denotes \({\boldsymbol{\beta }}\vert_{{\boldsymbol{\beta }}_{g}={\boldsymbol{0}}}\)). Given an element-wise shrinkage operator as \(\text{sof}{\text{t}}_{\lambda }({\boldsymbol{v}})[i]=\left({v}_{i}+\lambda \right)\left({{\boldsymbol{1}}}_{\{{v}_{i} < - \lambda \}} - {{\boldsymbol{1}}}_{\{{v}_{i} > \lambda \}}\right)\), this Equation can be further expanded as

Equation (14) is defined as the contrastive group shrinkage criterion. The gradient \({\nabla }_{{{\boldsymbol{\beta }}}_{g}}{L}_{C}\) provides guidance: if retaining the g-th group of sites does not yield a satisfactory contrastive embedding output, the gradient will make \({{\boldsymbol{\beta }}}_{g}\) decrease towards \({\boldsymbol{0}}\), leading to the exclusion of this site group.

After applying the contrastive group shrinkage criterion, the individual features of the surviving groups are updated. The optimal value of \({{\boldsymbol{\beta }}}_{g}\left[k\right]\) is attained at \(0\) if and only if

where \({{\boldsymbol{\beta }}}_{-{gk}}={\boldsymbol{\beta }}\vert_{{{\boldsymbol{\beta }}}_{g}\left[k\right]=0}\); and \({{\boldsymbol{D}}}_{g}={\mathrm{diag}}({D}_{g}^{1},\ldots,{D}_{g}^{{d}_{g}})\) is the degree matrix of \({{\boldsymbol{S}}}_{g}\) with \({D}_{g}^{i}\triangleq {\sum }_{j=1}^{{d}_{g}}{{\boldsymbol{S}}}_{g}\left[j,i\right]\). If Eq. (15) (denoted by \({{\rm{soft}}}_{{\lambda }_{1}}({C}_{g,k})\)) is not satisfied, \({{\boldsymbol{\beta }}}_{g}\left[k\right]\) will be explicitly calculated as a non-zero optimal value. Combining the two situations, \({{\boldsymbol{\beta }}}_{g}\left[k\right]\) is updated by the following contrastive individual shrinkage criterion:

Computational complexity of CDReg

When comparing to the classic sparse-group Lasso, for each iteration, the proposed contrast-guided shrinkage algorithm does an extra computation on the forward and backward phases of \({\mathcal{E}}\left(\cdot ;{\boldsymbol{\theta }}\right)\), with a computational complexity of \({\mathcal{O}}\left(p\left(p+d+D\right)\right)\), where \(p\) denotes the number of diseased-normal sample pairs, \(d\) denotes the number of DNAm sites, and \(D\) denotes the length of sample embeddings in the contrastive scheme. For each inner iteration, the dominant computational expense falls to the contrastive individual shrinkage with a complexity of \({\mathcal{O}}({d}_{g}(n+{d}_{g}))\), where \(n\) denotes the total sample number and \({d}_{g}\) denotes the number of DNAm sites in the g-th group (i.e., gene). Hence, the overall complexity of a single iteration is \({\mathcal{O}}\left(p\left(p+D+d\right)\right){\mathcal{+}}{\mathcal{O}}\left(d \,{{\rm{Max}}}_{g=1,\ldots,{\rm{G}}}\left({d}_{g}\left(n+{d}_{g}\right)\right)\right)\), which is comparable to that of the standard sparse-group Lasso and mainstream contrastive learning methods.

Comparing methods

The proposed method was compared with five state-of-the-art feature selection methods: (1) Lasso12 yields sparse solutions by using an L1-norm penalty to compress some coefficients to zeros. (2) ENet13 adds an L2-norm to Lasso to limit the scale of coefficients. When multiple features are related, Lasso tends to select a single feature while ENet promotes the smoothing of related features. Lasso and ENet were implemented using the glmnet R package66 (version 4.1.3), with the penalty term formulated as \(\alpha \lambda {\Vert{\boldsymbol{\beta }\Vert}}_{1}+\left(1-\alpha \right)\lambda {\Vert{\boldsymbol{\beta }\Vert}}_{2}^{2}/2\). For ENet, the hyperparameter \(\alpha\) was set to 0.8, and for Lasso, it was set to 1.0. The hyperparameter \(\lambda\) was automatedly determined using a built-in function based on cross-validation and a parameter search. (3) SGLasso14 adds a grouped L1-norm (L21-norm) to Lasso so that attains sparsity both on intra- and inter-group. The penalty term is defined as \(\alpha \lambda {\Vert{\boldsymbol{\beta }\Vert}}_{1}+(1-\alpha )\lambda {\sum }_{g=1}^{G}\sqrt {{d}_{g}}{\Vert{\boldsymbol{\beta }\Vert}}_{2}\). SGLasso was implemented using the SGL R package67 (version 1.3). The hyperparameter \(\alpha\) was set to the default value of 0.95, and \(\lambda\) was specified as 0.0001. (4) Pclogit16,17 is a logistic regression model based on network regularization, where CpG sites in the same gene are connected via identical edge weights. The penalty term is defined as \(\alpha \lambda {\Vert{\boldsymbol{\beta }\Vert}}_{1}+\,\left(1-\alpha \right)\, \lambda ({{\boldsymbol{\beta }}}^{T}{{\boldsymbol{S}}}^{T}{\boldsymbol{LS}}{\boldsymbol{\beta }})/2\), where \({\boldsymbol{S}}\) is a diagonal matrix with estimated signs of regression coefficients on its diagonal entries, and \({\boldsymbol{L}}\) is a Laplacian matrix that describes the covariations between variables. Pclogit was implemented using the pclogit R package (version 0.1), with \(\alpha\) set to 0.8 and \(\lambda\) automatedly determined using a built-in function. (5) Differentially methylated position (DMP) employs an F-test at each genomic site (i.e., DNAm site here) to assess the association between methylation levels and a categorical phenotype (i.e., diseased or normal). This method is executed using the dmpFinder function within the minfi R package68 (version 1.36.0) based on default hyperparameters. (6) DMRcate69,70 identifies and ranks the most significantly differentially methylated regions (DMR) by applying tunable kernel smoothing to the differential methylation signals. It is carried out using the dmrcate function in the DMRcate R package69,70 (version 2.4.1). The functions cpg.annotate and sequencing.annotate were used to organize input data for the microarray beadchip data in LUAD and AD experiments, and for the WGBS data in PC experiments, respectively.

Given that the DMP and DMRcate methods are specifically tailored for microarray and WGBS data, we include these two methods in application experiments. For the LUAD experiments, the Pclogit method was excluded from further comparison because its run time was far more than those of the other methods (exceeding 24 h).

Evaluation strategies

Feature selection correctness

In the simulation experiment, the ground-truth DNAm sites are known. To evaluate the ability of each method to discover the correct sites, we convert the regression task that estimates the importance weights of sites, into a binary classification problem that determines their selection probability.

In this binary classification evaluation framework, the ground-truth DNAm site for a candidate biomarker is labeled as positive, and all other sites are labeled as negative. We use the absolute value of the weights a model assigns to each site to denote its importance, and normalize these values to fall within the range [0.0, 1.0]. This normalization allows the values to represent the probability of a site being classified as a positive. The formula for this calculation is as follows:

where \({\rm{Abs}}\left(\cdot \right)\) denotes the absolute value operation, and \({\rm{Max}}\left(\cdot \right)\) and \({\rm{Min}}\left(\cdot \right)\) represent the calculation of the maximum and minimum values within a vector, respectively. For clarity, unless stated otherwise, the term weight refers to the normalized weight, \({{\boldsymbol{\beta }}}^{*}\).

In a classification framework with a threshold value of 0.5, a weight greater than 0.5 indicates that a site is selected (positive), and conversely, a weight less than or equal to 0.5 indicates non-selection (negative). Thus, common classification evaluation metrics can be employed to assess the performance of different methods in identifying ground-truth sites. Specifically, we used the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC), the area under the precision-recall curve (AUPRC), Accuracy, and Balanced Accuracy. In our feature selection simulation experiments, the ground-truth sites constitute a minority class, resulting in a class imbalance situation. The AUROC, AUPRC, and Balanced Accuracy are recognized to be informative for classification tasks in the presence of class imbalance.

Weights for spatially isolated or subject-specific sites

In simulation experiments, spatially isolated sites and subject-specific sites are predetermined. The weights a method assigns to these two types of sites serve as an indicator of its ability to filter out unreliable DNAm sites. When generating simulation data, these two types of DNAm sites possess the same absolute coefficients as the ground-truth sites but do not adhere to the principles of spatial clustering or disease specificity. Spatially isolated sites are those distanced from other significant sites, and assigning them smaller weights indicates a method’s ability to reinforce spatial clustering and mitigate noise. Subject-specific sites are those that exhibit variability among individuals but not between diseased and normal samples. Assigning smaller weights to these sites demonstrates a method’s effectiveness in enhancing disease specificity and reducing the interferences from individual characteristics.

Sample distances

In the LUAD experiment, we conducted both qualitative and quantitative comparisons of the distances within and between sample groups. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)71 was employed to visualize the sample distribution in a two-dimensional (2D) space.

Initially, each sample was denoted as a vector comprising methylation values from extensive number of DNAm sites. In our framework, it was also denoted as a vector in the hidden feature space. These high-dimensional samples were then projected onto a 2D plane using PCA. Additionally, we quantitatively measured the distances among samples in the PCA space using Euclidean distance.

Sample distances across groups were calculated as follows. Samples were divided into groups based on their origin from the same subject and their classification as cancerous or normal. Four groups were defined: (1) Paired, Cancer (\({S}_{{PC}}\)), (2) Paired, Normal (\({S}_{{PN}}\)), (3) Individual, Cancer (\({S}_{{IC}}\)), and (4) Individual, Normal (\({S}_{{IN}}\)). The distances between cross-class samples were computed as:

Here, \(p\) represents the number of paired samples, \({x}_{i}\) and \({x}_{{i}^{{\prime} }}\) denote a pair of cancer and normal samples from the same subjec\(\text{t}\). The distances between two sample groups of the same class but from different sources were computed as:

The values in each distance set were normalized into the range of 0.0–1.0 by \(\widetilde{d}\) = (d-Min)/Max-Min, to ensure comparability between the early and later stages of training (Fig. 4e, f). Here, Min and Max respectively represent the minimum and maximum values of the total distance set \({d}_{total}=\left\{i=1,\ldots,N;\,j=1,\ldots,N\,\vert\,{Dist}({x}_{i},{x}_{j})\right\}\), where \(N\) represents the total number of samples.

Qualitative evaluation for gene function

In application experiments, the identity of the ground-truth disease-specific DNAm biomarkers is unknown. To qualitatively assess the capacity of various methods to identify disease-specific DNAm biomarkers, we examined the biological functions of genes associated with the top-ranked sites. For DMRcate, DNAm sites are ranked according to Fisher values (ascending order) corresponding to each DMR, because DMRcate does not utilize a regression model and, therefore, does not assign weights. For all other methods, DNAm sites are ranked based on normalized weights (see “Feature selection correctness” for calculation details), in descending order. Sites that have identical weights are assigned the same ranking, and subsequent rankings are deferred.

Classification performance

We also evaluated methods’ ability to discover discriminative DNAm sites based on the classification performance of their top-ranked sites in the application experiments (Figs. 4b and 5c). Two traditional classifiers, support vector machine (SVM) and random forest (RF), were employed. The training data covering the top-ranked few DNAm sites were extracted and used to train the classifiers. These classifiers were then applied to the testing samples, covering the same set of sites, to evaluate classification performance. Accuracy and F1-score were adopted as evaluation metrics. Figure 5c depicts a curve generated by incrementally increasing the number of sites used. Moreover, the classification experiments were repeated ten times with either random sampling from an out-of-domain testing set (in LUAD experiments) or a random in-domain split of the training and testing sets from the complete dataset (in AD and PC experiments).

Implementation details

Python (version 3.8.19) served as the programming language for most experiments and analyses within this study, while R (version 4.0.4) was employed for DNAm data preprocessing or certain comparative methods implementation.

In preprocessing of HumanMethylation450 data, BMIQ R package60 (version 1.3) was adopted for type-2 probe bias correction, the EMimpute_array algorithm of LSimpute software was adopted for missing data imputation. ChAMP R package61 (version 1.3) was used for preprocessing of HumanMethylation EPIC data. Additionally, t.test and p.adjust functions in R were used for calculating P values for initial screening of DNAm sites. Details regarding the specific R packages and parameters used for the comparative methods are provided in the “Comparing Methods” section.

Seaborn (version 0.12.2) and matplotlib (version 3.6.2) were used to generate plots. Additional Python libraries that supported data processing and analysis include NumPy (version 1.19.2), pandas (version 1.3.5), scikit-learn (version 1.0.2), and SciPy (version 1.5.0). For the evaluation of classification performance, the classification models, Support Vector Machine (SVM) and Random Forest (RF), were implemented using the svm.SVC and ensemble.RandomForestClassifier functions from the scikit-learn library, respectively, with default parameters. Specifically, in SVM, the kernel function was set to radial basis function, and the strength of L2 regularization penalty was set to 1.0. In RF, the number of trees in the forest was set to 100, and the criterion to measure the quality of a split was set to Gini impurity.

The proposed CDReg model was developed using the PyTorch framework (version 1.10.1, CUDA 10.2). Simulation experiments were performed on a standard NVIDIA GeForce GTX 2080Ti graphics card with an 11-GB memory. The real-world application experiments utilized 20 CPUs (Intel(R) Core(TM) i9-10900X CPU @ 3.70 GHz). In the CDReg framework, the weights assigned to DNAm sites are represented as a learnable vector, the length of which is the total number of DNAm sites plus one additional element for the bias term. The data matrix, dimensions being the sample size by the number of DNAm sites plus one, is multiplied by the diagonalized weight vector to form the input for the contrastive scheme. The contrastive scheme’s mapping function, \({{\mathcal{E}}}_{{\boldsymbol{\theta }}}\), is implemented as a single-layer neural network, comprising a linear layer followed by a ReLU activation layer. The input dimension is the number of DNAm sites plus one. Its output dimension is set to 0.2 times the number of DNAm sites (rounded down to the nearest integer). The temperature constant \(\tau\) in the contrastive loss is set as 0.07. The multiplier \(\gamma\) used to enlarge \({\alpha }_{t}\) in Eq. (12) is fixed at 1.5. Training proceeds for 50 epochs using a stochastic gradient descent optimizer with a momentum of 0.99, weight decay of 1e-4, and a batch size of 500. Variable hyper-parameters across experiments, including \({\lambda }_{1}\), \({\lambda }_{2}\), \({\lambda }_{S}\), and \({\lambda }_{C}\) in Eq. (10), and the learning rate, are specified in Supplementary Table 5.

Statistical analysis

In the simulation experiments, the data generation process is randomly repeated ten times. In the classification validation on the LUAD experiments, the testing set sampling is randomly repeated ten times. In the classification validation on the AD and PC experiments, the training-testing data split is randomly repeated ten times. These repetitions guarantee the stability of our reported results. We used the one-sided paired-sample T-test to assess the statistical significance of the performance difference between our method and other comparing methods. This test aimed to reject the null hypothesis that the average evaluation metric of CDReg is not higher than another method. Differences with P values smaller than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The stats.ttest_rel function from the SciPy library was used to calculate the P values.

In Supplementary Fig. 1c, a two-sided T-test is utilized to evaluate the differences between diseased and normal samples, as well as between samples within the same class, by comparing sample’s coordinates along the y-axis. Since the samples are independent, the P values do not require correction. The stats.ttest_ind function from the SciPy library was used to calculate the P values.

Additionally, the two-sided T-test was conducted to evaluate the differences in average methylation levels at sites between diseased and the normal samples. These uncorrected P values were used for pre-screening DNAm sites. P values corrected using Benjamini-Hochberg41 method are shown in Figs. 4a, f, 5b to demonstrate the inter-class differences of DNAm sites under conditions of reduced false positives. The t.test and p.adjust functions in R were used to calculate the P value and BH-corrected P value for each site, respectively.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The simulation data are built dynamically in Python. The scripts that generate the data are publicly available in our source code. The DNA methylation array data of LUAD which is used as a training set was obtained from TCGA database through the UCSC Xena platform (https://xenabrowser.net/datapages/?hub=https://tcga.xenahubs.net:443) under accession code TCGA Lung Adenocarcinoma (LUAD). The corresponding testing set was collected from the GEO database under accession code GSE66836. The DNA methylation profiles of AD peripheral blood were downloaded from the repository of the ADNI database (http://adni.loni.usc.edu). Access requires registration and requestion, which includes institutional support and justification of data use. The PC data profiled by WGBS was obtained from MethBank (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/methbank/) with the Project ID HRA000099. Source data for figures are provided with this paper. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The source codes of this work are publicly available on GitHub at https://github.com/SJTUBME-QianLab/CDReg/.

References

Yousefi, P. D. et al. DNA methylation-based predictors of health: applications and statistical considerations. Nat. Rev. Genet. 23, 369–383 (2022).

Baylin, S. B. & Jones, P. A. Epigenetic determinants of cancer. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 8, a019505 (2016).

Roy, D. & Tiirikainen, M. Diagnostic power of DNA methylation classifiers for early detection of cancer. Trends Cancer 6, 78–81 (2020).

Bibikova, M. et al. High density DNA methylation array with single CpG site resolution. Genomics 98, 288–295 (2011).

Pidsley, R. et al. Critical evaluation of the Illumina MethylationEPIC BeadChip microarray for whole-genome DNA methylation profiling. Genome. Biol. 17, 1–17 (2016).

Espín-Pérez, A. et al. Peripheral blood DNA methylation profiles predict future development of B-cell Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma. NPJ Precis. Oncol. 6, 53 (2022).

Long, J. et al. DNA methylation-driven genes for constructing diagnostic, prognostic, and recurrence models for hepatocellular carcinoma. Theranostics 9, 7251 (2019).

Li, M. et al. A DNA methylation signature for the prediction of tumour recurrence in stage II colorectal cancer. Br. J. Cancer 128, 1681–1689 (2023).

Wang, T. et al. A multiplex blood-based assay targeting DNA methylation in PBMCs enables early detection of breast cancer. Nat. Commun. 14, 4724 (2023).

Xu, R.-h et al. Circulating tumour DNA methylation markers for diagnosis and prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat. Mater. 16, 1155–1161 (2017).

Mallik, S. et al. An evaluation of supervised methods for identifying differentially methylated regions in Illumina methylation arrays. Brief. Bioinforma. 20, 2224–2235 (2019).

Tibshirani, R. Regression shrinkage and selection via the lasso. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: series B. Methodological 58, 267–288 (1996).

Zou, H. & Hastie, T. Regularization and variable selection via the elastic net. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B 67, 301–320 (2005).