Abstract

As Li-ion batteries are increasingly being deployed in electric vehicles and grid-level energy storage, the demand for Li is growing rapidly. Extracting lithium from alternative aqueous sources such as geothermal brines plays an important role in meeting this demand. Electrochemical intercalation emerges as a promising Li extraction technology due to its ability to offer high selectivity for Li and its avoidance of harsh chemical regenerants. In this work, we design an economically feasible electrochemical process that achieves selective lithium extraction from Salton Sea geothermal brine and purification of lithium chloride using intercalation materials, and conversion to battery grade (>99.5% purity) lithium hydroxide by bipolar membrane electrodialysis. We conduct techno-economic assessments using a parametric model and estimated the levelized cost of LiOH•H2O as 4.6 USD/kg at an electrode lifespan of 0.5 years. The results demonstrate the potential of our technology for electro-driven, chemical-free lithium extraction from alternative sources.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The electrification of the transportation sector drives the rapid growth of electric vehicles (EVs) and increasing demand for Li-ion batteries1,2,3. The International Energy Agency projects a 42-fold growth of Li demand during 2020–2040 to meet the climate goals set by the Paris Agreement4. Despite the critical role of lithium in clean energy transition5,6, current lithium mining supplies are insufficient to meet the dramatically rising lithium demand in the coming decades. Presently, lithium mining mainly relies on hard-rock pegmatites and salars (salt flats)7. Recent studies showed an estimated 538,000-metric-ton deficit in supply by 20308. This projected lithium deficit calls for technological advancements to extract lithium from alternative sources to help meet the rapidly growing lithium demand and prevent the depletion of continental Li resources9,10,11,12.

Considering energy consumption and extraction cost, several alternative aqueous sources containing relatively high lithium concentration are considered potential lithium sources, including geothermal brine, oil and gas produced water, and reject brines from desalination10,13. Geothermal brines are a particularly promising candidate for lithium sources, especially the Salton Sea in California. Minable lithium resource in the Salton Sea area is estimated at 600,000 tons annually, far exceeding U.S. annual lithium consumption14. There are also detected lithium-rich geothermal brine in deep tectonic sedimentary basins in Germany and France and in volcano-sedimentary environment in Italy15 and also Qinghai-Tibet Plateau in China16. There is an urgent need to develop robust, economic, environment-friendly technologies to extract lithium from geothermal brines.

Conventional Li mining from brines relies on solar evaporation followed by chemical precipitation methods, which waste large amounts of water resources. Recent developments of direct lithium extraction have focused on Li sorbent materials17,18,19,20, Li selective membranes21,22,23,24,25,26, and electrochemical technologies27,28,29,30,31,32. Electrochemical separation holds a great promise in resource recovery because of high recovery selectivity and environmental friendliness11. Electro-driven lithium extraction from brines enables the generation of raw materials for battery manufacturing with little or no chemical inputs, reducing the total environmental impacts and carbon footprint in lithium battery’s life cycle.

Inspired by Li-ion batteries, Li intercalation materials like lithium iron phosphate (LiFePO4) have been demonstrated as promising electrodes for selective lithium extraction from high salinity brines32,33 due to their unique lattice structure34,35. However, several key research gaps remain. First, most lithium extraction studies generate lithium chloride as a product and need further processing to produce raw lithium materials (Li2CO3 or LiOH) for battery manufacturing. Recently, lithium hydroxide (LiOH) has become a more desirable raw material than lithium carbonate (Li2CO3) for the nickel manganese cobalt battery cathode fabrication, because the former enables battery cathode synthesis at lower temperatures and thus results in longer lifespan and safer operation36. Bipolar membrane electrodialysis (BMED) is a commercial technology mainly used for chemical processing37 and acid and/or base production38 and holds a great potential in lithium hydroxide production. Second, while most studies of electrochemical intercalation have focused on salt flats and salt lakes for testing lithium selectivity, there are very few works39,40 testing realistic or synthetic geothermal brines with practical ion compositions and achieving lithium selectivity over other metal ions.

In this work, for the first time, we report an economically viable, electro-driven system to extract lithium from Salton Sea geothermal brines in Imperial Valley, California and directly produce battery-grade (99.5% purity) lithium hydroxide as the final product41. The system consists of an intercalation deionization cell (IDI) and a BMED cell. We designed a continuous-flow cell with an accurate control over intercalation potential. We achieved 91.2% ± 0.9% Li molar purity in released solution from a synthetic geothermal brine containing Li+, Na+, Ca2+, K+, Fe2+, and Mn2+. A second-step purification yielded a pure LiCl solution with other cations under detection limit. Further, we successfully produced 99.6% ± 0.2% purity of LiOH solution by feeding LiCl solution in BMED and produced LiOH·H2O powder via crystallization. Finally, we conducted techno-economic analysis (TEA) to evaluate the economic competitiveness of this technology and estimated the levelized cost of produced LiOH•H2O (LCOL) as 4.6 USD/kg LiOH•H2O which is about one-third of the market price as of January 202442,43.

Results

Design of the direct lithium extraction system

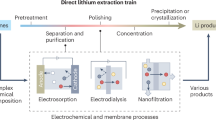

Figure 1a illustrates the proposed process of lithium extraction from geothermal brine. The hot brine is first pumped from the production well to the surface and stored in a flash tank. The hot steam generated during this stage is utilized by power turbines for electricity generation. The cooled brine, considered as a waste by the geothermal industry, serves as a source for lithium mining. The brine undergoes a lithium extraction and refinement process, selectively capturing lithium and leaving all other elements in the bulk solution, which is then re-injected into the underground reservoir via an injection well. The resultant lithium chloride solution is converted to produce a lithium hydroxide solution. Finally, the concentrated lithium hydroxide solution is crystallized to form LiOH•H2O solid powder, which serves as a raw material for battery manufacturing. The entire process employs renewable geothermal energy as the sole power input, eliminating the need for evaporation ponds, fossil fuels, or chemical reagents.

a Demonstration of the process train of lithium extraction from geothermal brine; b demonstration of IDI lithium extraction process from brines (Inset: crystal structure of LiFePO4 for lithium intercalation); c demonstration of IDI lithium chloride release process, and d BMED for LiOH solution production. CEM indicates cation exchange membrane and BPM indicates bipolar membrane.

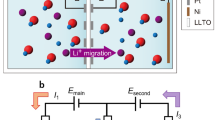

The working principle of extracting Li from geothermal brine using the integrated electrochemical process is also illustrated in Fig. 1. Figure 1b, c show the lithium chloride production by combining intercalative and capacitive electrodes. IDI is one of the configurations of electrosorption, an electric field-driven process to separate ions from water based on the principle of ion storage in charged electrodes. During the charging step, a potential bias is applied across the two electrodes, and ions migrate to and are stored capacitively in the electrical double layers within the porous carbonaceous electrodes or inserted into the intercalation electrodes. During the discharging step, the potential bias is released, and ions are released back to the bulk solution.

LiFePO4 (LFP) was chosen in this work as the working electrode because of its high Li selectivity, structural stability, and low Li intercalation energy barrier34,35,44. The crystalline structure of LiFePO4 is shown in Fig. 1b. Lithium ions can intercalate in the crystalline host materials and be stored in the lattice interstitial sites under electrical potential and released with reversed potential. Owing to the reversible intercalation and deintercalation, lithium intercalation materials can be used for lithium extraction in repeated cycles. During lithiation and delithiation, the electrode potential should be within the water stable window. Salton Sea geothermal brine for lithium extraction has a pH of around 5.514, which sets the water stable window between about −0.5 V versus Ag/AgCl electrode to avoid H2 evolution and 0.7 V versus Ag/AgCl to avoid O2 evolution (as shown in Fig. S1). Figure S2 shows the cyclic voltammetry (CV) results for FePO4 in 1 M LiCl solutions under 1 mV/s scan rate. The CV curve shows a pair of symmetric redox peaks indicating lithium capture and release. The theoretical potential plateau of lithiation and delithiation for FePO4 is about 3.5 V versus Li metal45, which is 0.26 V versus Ag/AgCl. The half-wave potential (E1/2 = 0.20 V vs. Ag/AgCl) is close to the theoretical thermodynamic values45. Figure S3 shows the flow cell system has a resistance of 6.8 Ω which is a small resistance similar to static beaker systems reported previously33. Based on the current density applied, the voltage drop caused by Ohmic resistance is ~5 mV, which is negligible relative to the applied potential; therefore, the potential reported in this study is not iR corrected.

As-fabricated LiFePO4 was first pre-delithiated to FePO4 confirmed by X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns (Fig. S4) and assembled in the cell together with activated carbon (AC) as the counter electrode. During the extraction stage, brine flows into the cell to allow lithium to be selectively intercalated in the FePO4 electrode and chloride capacitively stored on the AC electrode; in the release stage, by switching the feed source and reversing the potential, lithium ions are deintercalated and chloride ions are desorbed to obtain concentrated lithium chloride as effluent. Lithium hydroxide production process is schematically shown in Fig. 1d. BMED is one of the configurations of electrodialysis (ED), a continuous electric-field-driven process to separate opposite charged ions. With the potential bias applied, protons and hydroxide ions are generated from each side of the bipolar membranes. Lithium ions transport through the cation exchange membranes, forming lithium hydroxide in the concentrate channel.

High selectivity of Li extraction from brines

Geothermal brines contain complex compositions with more than ten elements detected46. This work examines Salton Sea brine as a representative lithium-rich geothermal brine. Table S1a shows the molar concentrations of major components for wellhead Salton Sea geothermal brine47. The molar concentration ratios of Li/Na, Li/Ca, Li/K are about 1:77, 1:23, and 1:14, respectively. Because sodium is a main competitor for lithium intercalation10, we employed Li and Na binary solution and two synthetic geothermal brines to study Li extraction performance. Four solutions were tested: 30 mM Li+ and 30 mM Na+ (Li/Na = 1:1); 30 mM Li+ and 2.3 M Na+ (Li/Na = 1:77); 30 mM Li+, 2.3 M Na+, 690 mM Ca2+, 430 mM K+, and 1.5 mM Mg2+ to simulate the main ion components of wellhead Salton Sea brine (synthetic geothermal brine A, Table S1a); and 42 mM Li+, 3.1 M Na+, 1070 mM Ca2+, 540 mM K+, 36 mM Fe2+, and 47 mM Mn2+ to simulate the Simbol feed Salton Sea brine after power generation and silica removal (synthetic geothermal brine B, supplied by the Idaho National Lab, Table S1b) which can be regarded as silica-free realistic geothermal brine for lithium extraction.

We started with 1:1 Li-Na binary solution for lithium extraction, using deionized (DI) water for lithium release to obtain LiCl. From specific capacity vs. potential curve (Fig. S5), the electrode potential increased to over 0.75 V vs. Ag/AgCl at the beginning of release process, which is attributed to the high electrical resistance of DI water. Voltage beyond water stability window will induce O2 evolution reaction and can cause the electrode to undergo structural degradation. Previous work used supporting electrolytes like magnesium chloride or ammonium chloride for lithium release to maintain a high electrical conductivity29. However, this approach requires further purification of LiCl from the mixed electrolyte and is undesirable in practice. Here, we replaced DI water with 5 mM LiCl, which maintains the electrical conductivity without introducing additional inpurities to the released solution. Using 5 mM LiCl as the solution for Li release, the initial electrode potential increases gradually (Fig. S5) and is thus more favorable for the electrode structural stability. We calculated lithium concentration percentage in the released solution \({{Li}}_{{released}}^{+} \% \) (the total selectivity coefficient48) as follows:

The lithium extraction selectivity (i.e., separation factor48) over sodium \({P}_{{{{\rm{Na}}}}^{+}}^{{{{\rm{Li}}}}^{+}}\) can be calculated as followed:

\({c}_{{feed},{{Li}}^{+}}\) and \({c}_{{feed},{{Na}}^{+}}\) are the lithium and sodium concentrations in the feed solution, respectively; \({c}_{{released},{{Na}}^{+}}\) is the sodium concentration detected in the released (or effluent) solution; \({c}_{{released},{{Li}}^{+}}\) is the lithium concentration detected in the released solution subtracting 5 mM.

With Li/Na = 1:1 feed solution, the molar fraction of Li reached 99.1% ± 0.5% in the released solution (Fig. 2a). The Li selectivity over sodium \({P}_{{{{\rm{Na}}}}^{+}}^{{{{\rm{Li}}}}^{+}}\) is calculated as 1.10 × 102 (Fig. 2c). This experiment confirmed that the hybrid IDI process can achieve highly selective lithium extraction similar to beaker system reported previously10.

Lithium and sodium concentration percentage at a 1:1 and b 1:77 concentration ratio feed solution; c lithium selectivity over sodium with different feed solution concentration ratios. Metal ion concentration percentage with synthetic geothermal brine A (d) and synthetic geothermal brine B feed solution (e); f lithium selectivity over sodium, calcium, and potassium with two synthetic geothermal brines. Error bars indicate the standard deviation of duplicate measurements using different electrodes. g a photo of synthetic geothermal brine B feed solution. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

We next tested the Li extraction performance in 1:77 Li-Na binary system; this molar ratio is the same as that in the Salton Sea wellhead geothermal brine. Li purity is 96.4% ± 1.2% in the released solution (Fig. 2b). The Li selectivity over sodium \({P}_{{{{\rm{Na}}}}^{+}}^{{{{\rm{Li}}}}^{+}}\) is calculated as 2.05 × 103 (Fig. 2c). From the comparison of \({P}_{{{{\rm{Na}}}}^{+}}^{{{{\rm{Li}}}}^{+}}\) with different feed solution concentration ratio, selectivity dramatically increased for the 1:77 Li-Na binary system because the Li concentration percentage in the feed solution decreased significantly but the Li percentage in the released solution remains higher than 95% enabled by the ultrahigh selectivity of LFP electrode.

Following successfully extracting lithium chloride from high sodium concentration brine in a flow cell, we conducted lithium selectivity test with synthetic geothermal brine A which contains sodium, calcium, potassium, and magnesium. Lithium molar fraction in the released solution, \({{Li}}_{{released}}^{+} \% \) (the total selectivity coefficient), can be calculated as follows:

The concentration percentage of other individual metal ions in the released solution \({M}_{{released}}^{n+} \% \) can be calculated as follows:

The lithium extraction selectivity (i.e., separation factor) over another metal ion \({P}_{{{{\rm{M}}}}^{{{\rm{n}}}+}}^{{{{\rm{Li}}}}^{+}}\) can be calculated as follows:

\({c}_{{feed},{M}^{n+}}\) and \({c}_{{released},{M}^{n+}}\) are concentrations of a metal ion in the feed solution and in the released solution, respectively.

Lithium molar fraction was around 0.9% in the feed solution and increased to about 92.3% ± 1.0% in the released solution. The concentration of Li+ in the feed and released solution was 30 mM and 9.6 mM, respectively. Note that a 5 mM LiCl solution was used as the release solution; after accounting for this, 4.6 mM Li+ was released from the electrode. The concentrations of the other four ions significantly decreased after the extraction process. Sodium decreased from 66.6% in the feed to 7.2% in the released solution, calcium decreased from 19.9% to 0.2%, potassium decreased from 12.5% to 0.3%, and since Salton Sea geothermal brine contains only 0.4% magnesium, magnesium was undetectable in the released solution (Fig. 2d). According to the selectivity calculation Eq. (5), lithium selectivity over sodium \({P}_{{{{\rm{Na}}}}^{+}}^{{{{\rm{Li}}}}^{+}}\) is 9.83 × 102, lithium selectivity over calcium \({P}_{{{{\rm{Ca}}}}^{2+}}^{{{{\rm{Li}}}}^{+}}\) is 1.48 × 104, and lithium selectivity over potassium \({P}_{{K}^{+}}^{{{{\rm{Li}}}}^{+}}\) is 4.41 × 103 (Fig. 2f), all are remarkably high and demonstrate the high selectivity of LFP.

We further conducted element mapping of the LFP electrodes at different extraction stages using transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Figure 3a shows that Li intensity is weak after pre-delithiation and before extraction. Li takes the majority of the intercalation sites after extraction as shown by the brighter Li mapping (Fig. 3b), and the electrodes become Li-depleted again after release (Fig. 3c). The electrode elemental composition percentage (Table S2) shows that sodium is always under 1% of the electrode mass in all extraction stages. The negligible presence of sodium in electrodes suggests that the sodium detected in the released solution may originate from a small fraction of feed brine that was trapped in the dead spaces in the flow channels, which can be reduced via improving reactor design and operation.

a Before Li extraction; b after Li extraction; c after Li release. From left to right: TEM image of FePO4 particle, Fe Energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX) elemental mapping, Na EDX elemental mapping, and Li Electron energy loss spectroscopy (EELS) elemental mapping (the color bar legend is only for Li elements).

To further evaluate the performance of the lithium extraction system in more complex brines, we tested synthetic geothermal brine B based on the Simbol Feed Brine (SFB; 04/20/2011 Report of Analysis, Table S1b). The brine contains iron, manganese, boron, strontium, and ammonia in addition to lithium, sodium, calcium, and potassium tested earlier. The brine preparation procedures are detailed in the Method section. By conducting the same extraction and release IDI experiments, lithium molar fraction is only around 0.7% in the feed solution and increased to about 91.2% ± 1.1% in the released solution according to Eq. (3) (Fig. 2e).

The robustness of electrochemical lithium intercalation is further demonstrated in two aspects. First, the high lithium selectivity is maintained at elevated temperature simulating geothermal brines. Geothermal brine produced from the reservoir (generally at a temperature of 230 °C to 370 °C for Salton Sea) is first used for power generation in a geothermal power plant using high-temperature steam and would cool down to 80 °C to 110 °C prior to direct lithium extraction49,50,51,52,53. To further evaluate the lithium selectivity with more mimic situations, we increased the synthetic brine B temperature from room temperature (RT) to 80 °C by conducting the same procedure. Lithium molar fraction still takes about 0.7% in the feed solution before the IDI extraction experiment and increased to 90.8% ± 1.2% in the release solution calculated from Eq. (3) (Fig. 2e). Second, the presence of scale-forming irons, including Fe and Mn, in the brine does not appreciably impact the lithium selectivity. In the presence of oxygen, oxidation of ferrous ions (FeII) to ferric ions (FeIII) in the brine can result in the precipitation of hydrous iron oxides. Since the whole system is partially exposed to air, the oxidation of some ferrous irons is expected to occur. Although the brine contains colloidal particles that are likely to cause scaling issues, lithium purity still remains over 90% in the released solution, demonstrating the robustness of the technology.

The Li extraction process needs to recover >80–90% Li in the geothermal brine to make the process economically viable. One technical barrier to achieving such a high extraction efficiency is that a sudden concentration change of over 50% will cause the electrochemical potential for Li intercalation to change abruptly, based on the Nernst equation. Therefore, to maintain a stable potential, the Li concentration change in the brine in each pass must be well controlled. To maximize the extraction efficiency while also maintaining stable electrical potential, we designed a stepwise extraction system with cells arranged in series (See Fig. S6). The brine with partial lithium extracted in the series 1 cell goes through the next series 2 extraction cell until most of the lithium in the brine is extracted. Using this design, we successfully achieved an extraction efficiency of over 85% in six cells in series (Fig. S7). Note that further improving the extraction efficiency to >90% is possible by including more cells, but the energy consumption will also increase due to the low concentration of Li left in the brine. Therefore, we opt to keep our extraction efficiency at 85% to maintain a good balance between high Li recovery and low energy consumption.

Mechanisms of Li selectivity revealed by density functional theory (DFT) calculations

The intrinsic selectivity of LFP toward Li+ has been attributed to its stronger bonding and/or smaller migration barrier than Na+, K+, Mg2+, Ca2+, based on molecular simulations performed in battery systems in the absence of water54. Here, we performed DFT calculations (detail in Method section) to gain a mechanistic understanding of the Li selectivity in aqueous solutions. Specifically, we simulated migration energy profiles of cations (initial state Fig. 4a, final state Fig. 4b, also see Supplementary Data 1) under the deintercalated limit along the [010] diffusion direction within the interfacial layer of an FePO4 slab immersed in water.

Initial (a) and final (b) states of nudged elastic band simulations for Li+ diffusion along the [010] axis direction in an FePO4 slab implicitly solvated by water. The oxygen, phosphorus, iron, and lithium atoms are colored red, ochre, pink, and purple, respectively. c Simulated energy profiles of cation diffusion along the [010] axis direction in a water-solvated FePO4 slab wherein the reaction coordinates of the initial and final states are designated as 0.0 and 1.0, respectively. d Calculated relative solvation energy profile of cations along the [010] axis direction in a water-solvated FePO4 slab wherein the reaction coordinates of the initial and final states are designated as 0.0 and 1.0, respectively. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

As shown in Fig. 4, Li+ not only exhibits a substantially smaller activation barrier, \(\Delta {E}_{{act}}={E}^{T}-{E}^{I}\), defined as the energy gap between the transition and initial states, than any other cations but also solely affords a negative enthalpy change, \(\Delta {H}_{{rxn}}={E}^{F}-{E}^{I}\), which is the energy difference between the initial and final states (Table S3). Its small \(\Delta {E}_{{act}}\) of 0.063 eV is comparable with the thermal fluctuation energy of \({k}_{b}T\) (i.e., ~0.025 eV) at room temperature, making its diffusion nearly dynamically effortless. Moreover, Li+’s negative \(\Delta {H}_{{rxn}}\) of −0.128 eV offers a moderate energetic driving force for its longitudinal inward diffusion thanks to the negligible distortion of the FePO4 inner layer, which forms shorter and stronger Li-O bonds than those on the outer layer that underwent surface reconstruction. For instance, the shortest Li-O in the final state is 1.97 Å, which is 0.04 Å shorter than its counterpart in the initial state (Table S4). Nevertheless, this cation-oxygen coordination that favors the inner-layer intercalation competes fiercely with the solvation effect that oppositely prefers the presence of interfacial cations through electrostatic interactions. As an example, when the bigger Na+ replaces Li+, the cation-oxygen coordination bonds become longer (i.e., from 1.97 to 2.13 Å), effectively reducing the favoritism of inner-layer interaction and resulting in a positive albeit small \(\Delta {H}_{{rxn}}\) of 0.082 eV. Similarly, a drastic increase of \(\Delta {E}_{{act}}\) to 0.404 eV was also observed because the weaker cation-oxygen coordination notably destabilizes the transition state of Na+. Interestingly, when an even bigger K+ is inserted, it cannot be stabilized at the topmost intercalation site. Instead, it leaks into the implicit water phase during geometry optimization, suggesting that the oxygen coordination cage of FePO4 is too small to host a K+ cation. Besides the cation size, its valency plays an important role, too. For instance, Ca2+ and Na+ are about the same size. But, the \(\Delta {H}_{{rxn}}\) of Ca2+ is significantly higher at 0.663 eV due to a much stronger solvation effect arising from its larger charge than Na+. This interplay between the size and valency effects is well demonstrated by Mg2+, which is smaller than Na+ yet has a higher valency. Specifically, the \(\Delta {H}_{{rxn}}\) of Mg2+ is remarkably larger than that of Na+ by 0.230 eV, while their \(\Delta {E}_{{act}}\) only differ by 0.119 eV. These distinct patterns can be ascribed to the dependency of \(\Delta {H}_{{rxn}}\) and \(\Delta {E}_{{act}}\) on a cation’s valency and size, respectively. Taken all together, our simulation results confirmed the exceptional extraction selectivity of Li+ over other common cations (Na+, K+, and Ca2+) in aqueous solutions by FePO4 observed in Fig. 2.

Moreover, the solvation effect on the cation diffusion along its pathway was quantified by the relative solvation energy, \(\Delta \Delta {E}_{{solv}}({r}_{c})\), defined as \({E}_{{solvent}}\left({r}_{c}\right)-{E}_{{vacuum}}\left({r}_{c}\right)-{E}_{{solvent}}\left(0\right)+{E}_{{vacuum}}(0)\) where \({r}_{c}\) is the reaction coordinate, \({E}_{{solvent}}\) and \({E}_{{vacuum}}\) are the system’s energies with and without the implicit water solvent, respectively. As shown in Fig. 4d, the values of \(\Delta \Delta {E}_{{solv}}({r}_{c})\) tend to be predominantly positive when \({r}_{c} \, > \, 0.5\), suggesting a well-stabilized initial state of all cations at the water interface by the solvation effect.

Generation of battery-grade lithium hydroxide using BMED

To produce battery-grade LiOH, pure LiCl solution is desired as feed into the BMED system. Therefore, we conducted a one-step purification with the same IDI system. When using 90% Li and 10% Na solution as the feed, Na was not detected in the released solution and therefore a pure LiCl solution was obtained (Fig. S8). When pure LiCl and DI water flow into the BMED system with a potential applied, electrolysis occurs on the bipolar membranes, H+ is released from the cation exchange layer and OH− is released from the anion exchange layer. Li+ migrates through the cation exchange membrane and forms LiOH with generated OH−. Figure 5a shows the concentration of ions in the dilute-in channel as a function of time. LiOH was gradually generated in the channel, and Cl− concentration is always negligible. The \({{Purity}}_{{LiOH}}\) was calculated as followed:

\({c}_{{{Cl}}^{-}}\) and \({c}_{{{OH}}^{-}}\) are the concentrations of Cl− and OH−; \({c}_{{{OH}}^{-}}\) was calculated from the pH value (Fig. S9). The average purity of LiOH produced is 99.6% ± 0.2% which reaches battery manufacturing grade. The collected LiOH solution was further subjected to rotary evaporation, which facilitates the crystallization process to form LiOH·H2O white power solid (Fig. 5b). The LiOH·H2O crystal structure was confirmed by XRD patterns (Fig. 5c).

Techno-economic assessment of the process

To understand the economic competitiveness of our technology, we further conducted techno-economic assessments (TEA) for our lithium extraction process using intercalation material by leveraging tools developed in our recent work on electrochemical desalination55 and lithium hydroxide conversion according to base production using BMED in previous work. The details for the TEA are presented below. We consider the contribution of both capital and operating costs to levelized cost of lithium (LCOL, USD/kg LiOH·H2O extracted).

Capital costs (Capex) include the costs of electrodes, IEMs, auxiliary module components (spacer, current collector, and housing), the balance of system components (sensors, pumps, valves and piping, electrical controls, and energy recovery devices), and indirect cost. Indirect cost is calculated from direct capital cost and total capital cost factor, which accounts for equipment installation, building and storage, design and engineering, and miscellaneous cost.

The actual Li adsorption capacity (LAC, mg/g LFP) of the electrode is calculated based on real experimental data using the following equation:

where \({C}_{{in},{expr}}\) is the concentration of the solution before the lithiation [mg L–1]; α is the extraction efficiency; \({V}_{{expr}}\) is the volume of the circulated solution [L], \({M}_{{LFP},{expr}}\) is the active LFP mass [g].

The mass-normalized average Li adsorption rate, \({ALA}{R}_{m}\) [mg g–1 h–1], is calculated using Eq. (8) from LAC, and the duration of a charge-discharge cycle (\(\tau\), h):

The productivity of the extraction unit [kg day–1], \({P}_{{{Li}}^{+}}\), or the mass of Li+ extracted by the plant per day could be calculated by Eq. (9):

where \({c}_{{in}}\) is the Li concentration in the inlet of DLE; \({Q}_{{out}}\) [m3/d] is the feed brine flow rate; \(R{{\rm{w}}}\) is brine recovery, defined as the percentage of brine volume recovered after DLE; and \({\eta }_{{LF}}\) is plant load factor, which is the ratio of average brine flow rate to an installed capacity of brine flow rate. The load factor accounts for the capacity utilization rate and downtime in the DLE plant.

The mass of electrodes (\({M}_{{elec}}\), kg) required for initial capital investment is calculated by:

Based on the estimated total electrode mass, we determined the electrode area in each module, which is then used to estimate the cost of IEMs and auxiliary module components.

Operating costs (Opex) include electricity, module replacement, maintenance, labor, and chemical costs. Electricity consumption includes electricity for charging the electrodes and pumping brine.

The energy consumed during extraction contains the energy used by cells and pumps:

The pumping energy consumption is calculated based on the water pumped during the process \({Q}_{{in}}\) and specific pumping energy, SPE [kWh/m3]:

The energy supplied to the IDI cells is calculated by the productivity \({P}_{{{Li}}^{+}}\) and the specific energy consumption (\({{SEC}}_{{extr}}\)), [kWh/kg Li+]:

The \({{SEC}}_{{extr}}\) is obtained using numerical integration of real-experimental energy consumed during lithiation and delithiation half-cycles.

where \({to}\) is the beginning of lithiation; \({te}\) is the end of the cycle; \(v\left(t\right)\) is the voltage profile during the cycle; \(I\) is the current [mA]. During delithiation, the current is reversed, and some supplied energy during the lithium capture stage can be recovered in the delithiation stage.

The productivity of the conversion unit is the mass of LiOH produced per day:

where β is the conversion rate from LiCl to LiOH; \({Q}_{{BMED}}\) is the influent flowrate of BMED process [m3/d]; \({c}_{{LiCl}}\) is the inlet LiCl concentration [mM]; \({\eta }_{{LF}}\) is the load factor of the plant; \({M}_{w}\) is the molar mass of LiOH•H2O[g/mol].

The total capital cost CC is the sum of the membrane stack cost and the peripherals cost

where the membrane stack cost is calculated as

where A is the area of cross-sectional area; \({C}_{{IEM}},{C}_{{BPM}},{C}_{{sp}}\) are the unit cost of IEM, BPM, and Spacer; \({n}_{{IEM}}\), \({n}_{{BPM}},{n}_{{SP}}\) are the numbers of IEMs, BPMs, and spacers.

The peripherals cost is calculated as \({C}_{{Peri}}={F}_{P}{C}_{{mem}}\), where Fp is the Peripherals factor.

The operational cost is calculated as

where the maintenance & labor cost is \({{OC}}_{{ML}}={F}_{{ML}}{CC}\), where \({F}_{{ML}}\) is maintenance & labor factor. The electricity cost per year is \({{OC}}_{{Elec}}=365V{C}_{{electri}}({P}_{{LiOH}}{{\cdot }}{{SEC}}_{{BMED}}+{Q}_{{BMED}}{{\cdot }}{SPE})\), where \(V{C}_{{electri}}\) is the unit price of electricity; \({{SEC}}_{{BMED}}\) is the specific conversion energy [kWh/kg LiOH•H2O], SPE is the specific pumping energy.

The annualized capital cost is \({{ATCC}}_{{BMED}}={{{\rm{CC}}}}_{{BMED}}{{\rm{\cdot }}}{CF}\), where CF is the capital factor. So, the annualized total cost is \({{TOC}}_{{BMED}}={{ATCC}}_{{BMED}}+{{OC}}_{{BMED}}\), and the levelized cost of Lithium conversion [$/kg LiOH•H2O] is \({{LCOL}}_{{conv}}=\frac{{{TOC}}_{{BMED}}}{{365P}_{{LiOH}}}.\)

Considering the freshwater usage for washing the flow cell system between extraction and release process, the water cost could be calculated by followings:

\({{LCOL}}_{{water}}\) is the levelized cost for washing in this process, in USD/kg. Freshwater consumption is estimated as 24.8 L/kg LiOH•H2O, and the cost of freshwater contributes to 0.04 USD/kg LiOH•H2O which is less than 1% of total cost.

Based on this analysis (see Tables 1, S5, and S6 for a full list of parameters), we estimated the unit cost for extracting Li (Fig. 6a, b). IEM and electrode are major contributors to the cost of Li extraction mainly due to the cost of replacement when the electrode comes to the end of life. The LCOL, with a unit of USD/kg LiOH•H2O, decreases with increasing Li extraction efficiency (i.e., the ratio of the moles of Li recovered to the moles of Li in the feed). LCOL strongly depends on the electrode lifespan; increasing the electrode lifespan from 0.2 to 1 year reduces LCOL by over 70%. With the system baseline parameters used in our analysis (electrode lifespan 0.5 years, see Tables S5, S6), the LCOL is 4.6 USD/kg LiOH•H2O and about one third of market price for LiOH•H2O as of January 202442,43.

Discussion

Our integrated electrochemical lithium extraction technology presents three unique advantages: (1) high selectivity for Li over monovalent and multivalent competing cations in geothermal brines; (2) the lithium capture and release processes are driven entirely by electricity, with no consumption of harsh chemicals; (3) electro-driven generation of battery-grade lithium hydroxide monohydrate at competitive costs.

As revealed by our DFT simulation, LiFePO4 electrochemical intercalation offers high Li selectivity owing to thermodynamic preference and small energy barrier for Li migration in the intercalation hosts. FePO4 has a unique lattice structure, and due to its channel dimensions, Li+ can be selectively separated from Ca2+, Mg2+ and K+ after full dehydration34,35. LiFePO4 possesses high intrinsic selectivity for Li in aqueous solutions. However, realizing high Li selectivity in a continuous flow cell necessitates system design that allows for accurate control of intercalation potential. We design a three-electrode flow system with lithium intercalation materials to achieve high lithium selectivity over competing ions under well-controlled potential. Three-electrode configuration is commonly used in static beaker system by previous studies27,29. In flow cell ion separation, two-electrode configuration is widely applied in capacitive deionization and IDI56,57. However, as both Li+ and Na+ are able to intercalate into FePO4 interstitial sites but at different plateau potentials10, it is difficult to control the working electrode potential when the counter electrode that captures anions is used as the reference. Our IDI system with a reference electrode allows accurate control over the potential for lithium intercalation and thus enables an ultrahigh selectivity over Na+ and other cations in the flow cell.

The electrification of lithium mining, or the substitution of chemically intensive lithium extraction processes with electricity-driven processes to produce battery raw materials with equivalent grade, will be critical to decarbonizing the battery manufacturing and electrical vehicle industry. Compared with other direct lithium extraction methods (Table S7) summarized in recent work9, IDI extraction shows outstanding lithium selectivity and minimizes the mining environmental impacts. Lithium sorbents/ion exchangers and some organic solvents have a high affinity for Li+ but suffer from drawbacks of using harsh acid for regeneration and the potential release of organic solvents to the environment, respectively58,59,60,61. Some lithium sorbents like layered double hydroxide can be regenerated by freshwater62, which, however, is a scarce resource in remote and arid locations where many lithium brines are found. Recently, there have been extensive studies on lithium separation by membrane-based technologies including pressure-driven and electrical-field-driven membrane process21,63,64,65,66,67. While most membrane-based lithium extraction technologies show selectivity for lithium over multivalent cations, they often struggle to achieve high selectivity (>5) for lithium over monovalent cations such as Na+ and K+ (see Table S7), which is needed to produce high-purity lithium hydroxide monohydrate.

Our integrated electrochemical process allows chemical-free production of high-quality lithium hydroxide monohydrate from geothermal brines using electricity as the input, thus enabling on-site lithium extraction and refinement within geothermal power plants. In addition, electrochemical cells can be fabricated as modular devices, and easily scaled up to fit the needs of desired brine flow rate and lithium extraction capacities. Continuous flow systems will reduce the brine storage burden within the geothermal power plants. We anticipate that our technology works not only for geothermal brines, but also holds promise in lithium extraction from continental salt flat brines as well as alternative lithium sources like oil/gas-produced water and desalination brines. The sources for electricity could vary by extraction sites; potential sources include geothermal, solar, wind, or other renewable energy sources, thus minimizing the environmental impacts of the lithium mining industry. Finally, our techno-economic assessment shows that our electrochemical lithium extraction processes can be cost-competitive against conventional lithium mining if the electrodes have sufficient longevity. Our recent work has demonstrated that the faradaic efficiency of LFP electrode was maintained at near 100% ± 2.5% after 100 cycles in simulated Atacama brine7.

To further commercialize electrochemical direct lithium extraction technologies, there are barriers needed to overcome for scaling up. First, electrode fabrication needs to be optimized for industrial-scale manufacturing. The drop casting method used in the lab is only capable of producing electrodes in the centimeter size range; for manufacturing electrodes with larger areas in the meter range, more scalable methods including roll-to-roll coating68, slot-die coating69, or spray coating70 should be employed. Second, the Li extraction cells need to have the ability to handle high-temperature brines for long periods of time, and automated control systems need to be added to maximize system efficiency. Third, the geothermal brine and other alternative lithium sources have complex water composition, containing foulants and mineral scalants which might cause deterioration of electrode performance over extended cycling. Further improving the capacity retention of the electrode while maintaining high Li selectivity through the optimization of electrode fabrication and device operation will be critical to enhancing the economic competitiveness of electrochemical Li extraction from geothermal and other alternative lithium brine sources.

Methods

Preparation of electrodes

All FePO4 electrodes were prepared by casting a slurry of LiFePO4 (MTI Corporation, Model Number: P198-S20), Super P carbon black (MTI Corporation; Item Number: Lib-SP; average particle size ~40 nm; purity ≥99.5%), and polyvinylidene fluoride (Thermo Fisher Scientific, CAS: 24937-79-9, MP: 155–160 °C) with a mass ratio of 80:10:10 in 1-methyl-2-pyrrolidone (Thermo Fisher Scientific, ACS grade, 99.0+%). The electrode slurry was drop-casted by adjustable volume dingle channel pipettor (eppendorf) on a 3 × 3 cm2 geometrical surface of a porous carbon cloth (ELAT-H, FuelCellEtc, 406 μm in thickness, 80% porosity) and dried in an oven at 80 °C overnight (Fig. S10). The active material mass loadings ranged between 5 ± 0.5 mg/cm2.

Brine preparation

The recipe-salts (Table S1b) were completely dissolved with stirring, after sparging deionized (DI) water (Millipore, Milli-Q, 18.2 MΩ cm resistivity) with nitrogen for 30 min. The brine pH was then adjusted to ~5.5 with sodium hydroxide (Sigma-Aldrich, ACS reagent, ≥97%) and hydrochloric acid solutions (Sigma-Aldrich, ACS reagent, 37%) (as needed).

Electrochemical methods

All electrochemical operations were performed on a potentiostat (Bio-Logic VSP) at room temperature (20~25 °C). During pre-delithiation process, a LiFePO4 (LFP) working electrode was paired with a Pt counter electrode (Sigma) and an Ag/AgCl (3 M KCl) reference electrode (BASi Research Product Inc, MF-2056) for galvanostatic Li-ion deintercalation in 100 mL 1 M LiCl with 0.1 C rate (1 C is equivalent to 147 mA/g specific current), i.e., 14.7 mA/g current density (Fig. S11). After pre-delithiation, electrodes were rinsed with DI water to remove adsorbed Li+ and ready for the intercalation process.

The IDI cell consists of rectangular acrylic plates (McMaster), rubber gaskets, a plastic mesh spacer, a pair of graphite plates as current collectors (McMaster-Carr), a piece of LFP electrode, a piece of carbon electrode and Ag/AgCl (3 M KCl) reference electrode (Edaq Inc, ET073-1). 3D schematic and assembling details of the device are shown in Fig. S12. The sizes of the electrodes were 3 × 3 cm. An anion exchange membrane (AMI-7001, Membrane International Inc., 3 cm × 3 cm × 0.46 mm) was placed between the positive electrode and the mesh separator.

All IDI experiments were performed in the flow-by (i.e., solution flows in parallel to the electrode pairs) mode with single-pass operation (i.e., effluent does not recirculate back to the feed). Prior to experiments, the carbon electrodes were infiltrated with the working solution in vacuum for 30 min. The assembled IDI cell was then equilibrated with the working solution for overnight. During the lithium extraction step, solutions were continuously flowed through the IDI cell at a flow rate of 0.5 mL/min with 0.1 C rate. During the lithium release step, 5 mM LiCl solution was continuously flowed through the IDI cell at a flow rate of 0.05 mL/min with 0.1 C rate. DI water flowed into the cell for washing between the lithium extraction and release processes. The cation concentrations after release process were measured using an inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectrometer (Agilent Technologies 5800 ICP-OES; Agilent Technologies SPS 4 Autosampler).

Potential Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy measurements were conducted to analyze the total resistance between working electrode (WE) and reference electrode (RE) in the cell system. A constant potential of 0.025 V was applied to imitate the lithiation reaction during the process and the impedance spectra were recorded over a frequency range from 100 kHz to 10 mHz with an AC amplitude of 10 mV. The data was obtained through fitting with the Bio-Logic EC-lab software, using the “Randomize + Simplex method” with 5000 iterations (Fig. S3).

BMED cell (PCCell ED 64004) was assembled with bipolar membranes (FuelCell, Fumasep FBM, 110 × 110 × 0.1 mm) and cation exchange membranes (PCCell, 110 × 110 × 0.1 mm) 10 mM LiCl and DI water was fed in as dilute-in and concentrate-out streams, respectively, at a flow rate of 5 mL/min. 2.0 V was applied as constant voltage for 2 h. N2 (purity > 99.998%) was continuously purged into the solution to minimize dissolved CO2 in the solution. The Li purity was measured using an inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectrometer (Agilent Technologies 5800 ICP-OES; Agilent Technologies SPS 4 Autosampler) and the anion concentrations were measured using an ion chromatograph (IC) (Dionex ICS-1100; Dionex IonPac AS18 column) with 10 mM NaOH as the eluent at 0.25 mL/min eluent flow rate.

Density functional theory (DFT) simulation methods

Since the extraction selectivity of various cations (i.e., Li+, Na+, K+, Mg2+, and Ca2+) from aqueous solutions by FePO4 is primarily decided by their associated migration energy profiles, they were calculated by the density functional theory (DFT)71 in conjunction with the nudged elastic band (NEB)72 method. In our simulation, a 2 × 2 supercell of FePO4 slab with a normal direction of [010] and a thickness of ~12.0 Å was adopted (Fig. 4), leading to a surface area of 9.72 Å × 19.83 Å given the experimental crystal structure of olivine FePO473. After adding a cation to the FePO4 slab, there are 193 atoms in our simulation system, where its top layer of oxygen is designated as the water/slab interface and thus is set as the plane ac with b = 0 as its longitudinal coordinate. Aiming to model the solvation effect on the interfacial layer, an implicit solvation model74 with a dielectric constant of 78.4 was applied to the region with b > 0 (Fig. 4). Unless otherwise specified, all simulations were performed using the open-source CP2K software75 with Perdew–Burke–Ernzehof (PBE) exchange-correlation functional76, Goedecker–Teter–Hutter (GTH) pseudopotential77, and polarized-valence-double-ζ (PVDZ) basis set78. Specifically, the NEB’s initial state is defined as the optimized structure with the added cation residing in one of the topmost intercalation sites (Fig. 4a), while its counterpart immediately along the [010] axis direction is the NEB’s final state (Fig. 4b). A total of 16 NEB images connected by a spring constant of 9.72 eV/Å2 were employed to search for the transition state using the doubly nudged elastic band (D-NEB) algorithm79.

Lithium hydroxide monohydrate crystallization

LiOH•H2O powder was collected under reduced pressure using a BUCHI rotavapor R-300. The solution was heated to 80 °C and placed under 0 mbar pressure to remove water. The damp solid was lyophilized for 48 h using as a labconco FreeZone benchtop freeze dryer system. The remaining LiOH•H2O solid was ground into a fine powder for imaging.

Materials characterization

Scanning transmission electron microscope-Energy dispersive spectroscopy (STEM-EDS) mapping was acquired using an Oxford X-Max 100TLE windowless SDD detector equipped with JEOL ARM 200F. Electron energy loss spectroscopy (EELS) spectra were acquired using a Gatan GIF Continuum ER with a dwell time of 0.03 s per pixel. XRD patterns were obtained with a Bruker D2 Phaser X-ray diffractometer using Cu Kα radiation and a LYNXEYE XE-T detector.

Data availability

Source data are provided in the Source Data file with this paper. The raw data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

McKerracher, C. et al. Electric Vehicle Outlook 2024 (Bloomberg NEF, 2024).

Martin, G., Rentsch, L., Höck, M. & Bertau, M. Lithium market research – global supply, future demand and price development. Energy Storage Mater. 6, 171–179 (2017).

Naumov, A. V. & Naumova, M. A. Modern state of the world lithium market. Russ. J. Non-Ferr. Met. 51, 324–330 (2010).

IEA. The Role of Critical Minerals in Clean Energy Transitions. https://www.iea.org/reports/the-role-of-critical-minerals-in-clean-energy-transitions (IEA, Paris, 2021).

Hund, K. L., Arrobas, D. L. P., Fabregas Masllovet, T. P., Laing, T. J. & Drexhage, J. R. Minerals for Climate Action: The Mineral Intensity of The Clean Energy Transition. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/099052423172525564/P16627806f5aa400508f8c0bdcba0878a3e (World Bank Group, Washington, D.C., 2020).

Goonan, T. G. Lithium use in batteries: U.S. Geological Survey Circular. 1371, 14 p., available at http://pubs.usgs.gov/circ/1371/ (U.S. Department of the Interior, 2012).

Kesler, S. E. et al. Global lithium resources: relative importance of pegmatite, brine and other deposits. Ore Geol. Rev. 48, 55–69 (2012).

Sun, K. Bank of America forecasts lithium oversupply in 2023; deficit set to resume in 2027. (https://www.marketindex.com.au/news/bank-of-america-forecasts-lithium-oversupply-in-2023-deficit-set-to-resume, 2022).

Vera, M. L., Torres, W. R., Galli, C. I., Chagnes, A. & Flexer, V. Environmental impact of direct lithium extraction from brines. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 4, 149–165 (2023).

Yan, G., Wang, M., Hill, G. T., Zou, S. & Liu, C. Defining the challenges of Li extraction with olivine host: the roles of competitor and spectator ions. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 119, e2200751119 (2022).

DuChanois, R. M. et al. Prospects of metal recovery from wastewater and brine. Nat. Water 1, 37–46 (2023).

Grosjean, C., Miranda, P. H., Perrin, M. & Poggi, P. Assessment of world lithium resources and consequences of their geographic distribution on the expected development of the electric vehicle industry. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 16, 1735–1744 (2012).

Swain, B. Recovery and recycling of lithium: a review. Sep. Purif. Technol. 172, 388–403 (2017).

Ventura, S., Bhamidi, S., Hornbostel, M. & Nagar, A. Selective Recovery of Lithium from Geothermal Brines (California Energy Commission, 2020).

Sanjuan, B. et al. Lithium-rich geothermal brines in Europe: an up-date about geochemical characteristics and implications for potential Li resources. Geothermics 101, 102385 (2022).

Gao, C., Yu, J., Min, X. & Cheng, A. Hydroclimatic and geothermal controls of lithium brine deposits on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. IOP Conf. Ser.: Mater. Sci. Eng. 780, 042062 (2020).

Chitrakar, R., Makita, Y., Ooi, K. & Sonoda, A. Synthesis of iron-doped manganese oxides with an ion-sieve property: lithium adsorption from Bolivian brine. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 53, 3682–3688 (2014).

Chitrakar, R., Makita, Y., Ooi, K. & Sonoda, A. Lithium recovery from salt lake brine by H2TiO3. Dalton Trans. 43, 8933–8939 (2014).

Wang, S., Li, P., Zhang, X., Zheng, S. & Zhang, Y. Selective adsorption of lithium from high Mg-containing brines using HxTiO3 ion sieve. Hydrometallurgy 174, 21–28 (2017).

Wu, X. et al. Sustainable lithium extraction enabled by responsive metal-organic frameworks with ion-sieving adsorption effects. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 121, e2309852121 (2024).

Warnock, S. J. et al. Engineering Li/Na selectivity in 12-Crown-4–functionalized polymer membranes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 118, e2022197118 (2021).

Hoshino, T. Preliminary studies of lithium recovery technology from seawater by electrodialysis using ionic liquid membrane. Desalination 317, 11–16 (2013).

Peng, Q. et al. Extreme Li-Mg selectivity via precise ion size differentiation of polyamide membrane. Nat. Commun. 15, 2505 (2024).

Razmjou, A., Asadnia, M., Hosseini, E., Habibnejad Korayem, A. & Chen, V. Design principles of ion selective nanostructured membranes for the extraction of lithium ions. Nat. Commun. 10, 5793 (2019).

Xiao, H. et al. A lithium ion selective membrane synthesized from a double layered Zrbased metalorganic framework (MOF-on-MOF) thin film. Desalination 532, 115733 (2022).

Wang, R. & Lin, S. Membrane design principles for ion-selective electrodialysis: an analysis for Li/Mg separation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 58, 3552–3563 (2024).

Kim, J.-S. et al. An electrochemical cell for selective lithium capture from seawater. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49, 9415–9422 (2015).

Pasta, M., Battistel, A. & La Mantia, F. Batteries for lithium recovery from brines. Energy Environ. Sci. 5, 9487–9491 (2012).

Liu, C. et al. Lithium extraction from seawater through pulsed electrochemical intercalation. Joule 4, 1459–1469 (2020).

Lee, J., Yu, S.-H., Kim, C., Sung, Y.-E. & Yoon, J. Highly selective lithium recovery from brine using a λ-MnO2–Ag battery. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 15, 7690–7695 (2013).

Kim, N., Su, X. & Kim, C. Electrochemical lithium recovery system through the simultaneous lithium enrichment via sustainable redox reaction. Chem. Eng. J. 420, 127715 (2021).

Trócoli, R., Battistel, A. & Mantia, F. L. Selectivity of a lithium-recovery process based on LiFePO4. Chem. A Eur. J. 20, 9888–9891 (2014).

Yan, G. et al. The role of solid solutions in iron phosphate-based electrodes for selective electrochemical lithium extraction. Nat. Commun. 13, 4579 (2022).

Delmas, C., Maccario, M., Croguennec, L., Le Cras, F. & Weill, F. Lithium deintercalation in LiFePO4 nanoparticles via a domino-cascade model. Nat. Mater. 7, 665–671 (2008).

Dong, Y. Z., Zhao, Y. M. & Duan, H. Crystal structure and lithium electrochemical extraction properties of olivine type LiFePO4. Mater. Chem. Phys. 129, 756–760 (2011).

Liu, H. & Azimi, G. Production of battery grade lithium hydroxide monohydrate using barium hydroxide causticizing agent. Resour., Conserv. Recycl. 179, 106115 (2022).

Huang, C. & Xu, T. Electrodialysis with bipolar membranes for sustainable development. Environ. Sci. Technol. 40, 5233–5243 (2006).

Davis, J. R., Chen, Y., Baygents, J. C. & Farrell, J. Production of acids and bases for ion exchange regeneration from dilute salt solutions using bipolar membrane electrodialysis. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 3, 2337–2342 (2015).

Siekierka, A., Tomaszewska, B. & Bryjak, M. Lithium capturing from geothermal water by hybrid capacitive deionization. Desalination 436, 8–14 (2018).

Paranthaman, M. P. et al. Recovery of lithium from geothermal brine with lithium–aluminum layered double hydroxide chloride sorbents. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51, 13481–13486 (2017).

Liu, X. & Kong, L. Chemical free extraction of lithium from brine. US patent (2023).

Lithium - Price - Chart - Historical Data, https://tradingeconomics.com/commodity/lithium (2024).

LME Lithium Hydroxide CIF (Fastmarkets MB), https://www.lme.com/en/metals/ev/lme-lithium-hydroxide-cif-fastmarkets-mb#Trading+day+summary (2024).

Nishimura, S.-i. et al. Experimental visualization of lithium diffusion in LixFePO4. Nat. Mater. 7, 707–711 (2008).

Padhi, A. K., Nanjundaswamy, K. S. & Goodenough, J. B. Phospho‐olivines as positive‐electrode materials for rechargeable lithium batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 144, 1188 (1997).

Stringfellow, W. T. & Dobson, P. F. Technology for the recovery of lithium from geothermal brines. Energies 14, 6805 (2021).

Salton Sea Brine Chemistry (U.S. Department of Energy, Geothermal Technologies Office, 2021).

Battistel, A., Palagonia, M. S., Brogioli, D., La Mantia, F. & Trócoli, R. Electrochemical methods for lithium recovery: a comprehensive and critical review. Adv. Mater. 32, 1905440 (2020).

Salton Sea Long-Range Plan Appendix C: Water Use and Availability for Lithium Extraction (California Natural Resources Agency, 2024).

White, D. E. Deep geothermal brine near Salton Sea, California. Bull. Volcanol. 27, 369–370 (1964).

Kamila, Z., Kaya, E. & Zarrouk, S. J. Reinjection in geothermal fields: an updated worldwide review 2020. Geothermics 89, 101970 (2021).

Newsom, G. Selective Recovery of Lithium from Geothermal Brines (California Energy Commission, 2020).

Inanli, M. & Atilla, V. Metal silicate formation at Tuzla geothermal brine lines. Proceedings International Workshop on Mineral Scaling. (Manila, Philippines, 2011).

Rong, Z. et al. Materials design rules for multivalent ion mobility in intercalation structures. Chem. Mater. 27, 6016–6021 (2015).

Liu, X., Shanbhag, S., Bartholomew, T. V., Whitacre, J. F. & Mauter, M. S. Cost comparison of capacitive deionization and reverse osmosis for brackish water desalination. ACS EST Eng. 1, 261–273 (2021).

Ryu, T. et al. Recovery of lithium by an electrostatic field-assisted desorption process. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 52, 13738–13742 (2013).

Kim, B., Seo, J. Y. & Chung, C.-H. Electrochemical desalination and recovery of lithium from saline water upon operation of a capacitive deionization cell combined with a redox flow battery. ACS EST Water 1, 1047–1054 (2021).

Li, X. et al. Amorphous TiO2-derived large-capacity lithium ion sieve for lithium recovery. Chem. Eng. Technol. 43, 1784–1791 (2020).

Marthi, R. & Smith, Y. R. Application and limitations of a H2TiO3 – Diatomaceous earth composite synthesized from titania slag as a selective lithium adsorbent. Sep. Purif. Technol. 254, 117580 (2021).

Shi, C. et al. Solvent extraction of lithium from aqueous solution using non-fluorinated functionalized ionic liquids as extraction agents. Sep. Purif. Technol. 172, 473–479 (2017).

Meng, Z. et al. Highly flexible interconnected Li+ ion-sieve porous hydrogels with self-regulating nanonetwork structure for marine lithium recovery. Chem. Eng. J. 445, 136780 (2022).

Zhong, J., Lin, S. & Yu, J. Li+ adsorption performance and mechanism using lithium/aluminum layered double hydroxides in low grade brines. Desalination 505, 114983 (2021).

He, R. et al. Unprecedented Mg2+/Li+ separation using layer-by-layer based nanofiltration hollow fiber membranes. Desalination 525, 115492 (2022).

Li, Q. et al. Efficiently rejecting and concentrating Li+ by nanofiltration membrane under a reversed electric field. Desalination 535, 115825 (2022).

Li, X. et al. Membrane-based technologies for lithium recovery from water lithium resources: a review. J. Membr. Sci. 591, 117317 (2019).

Wang, R., He, R., He, T., Elimelech, M. & Lin, S. Performance metrics for nanofiltration-based selective separation for resource extraction and recovery. Nat. Water 1, 291–300 (2023).

Yu, H. et al. Selective lithium extraction from diluted binary solutions using metal-organic frameworks (MOF)-based membrane capacitive deionization (MCDI). Desalination 556, 116569 (2023).

Nam, D.-H., Lumley, M. A. & Choi, K.-S. A seawater battery with desalination capabilities enabling a dual-purpose aqueous energy storage system. Energy Storage Mater. 37, 556–566 (2021).

Schmitt, M. et al. Slot-die processing of lithium-ion battery electrodes—Coating window characterization. Chem. Eng. Process. Process Intensif. 68, 32–37 (2013).

Liu, Y. et al. Roll-to-roll solvent-free manufactured electrodes for fast-charging batteries. Joule 7, 952–970 (2023).

Hohenberg, P. & Kohn, W. Inhomogeneous electron gas. Phys. Rev. 136, B864–B871 (1964).

Henkelman, G., Uberuaga, B. P. & Jónsson, H. A climbing image nudged elastic band method for finding saddle points and minimum energy paths. J. Chem. Phys. 113, 9901–9904 (2000).

Bergerhoff, G., Hundt, R., Sievers, R. & Brown, I. D. The inorganic crystal structure data base. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 23, 66–69 (1983).

Bani-Hashemian, M. H., Brück, S., Luisier, M. & VandeVondele, J. A generalized Poisson solver for first-principles device simulations. J. Chem. Phys. 144, 044113 (2016).

Kühne, T. D. et al. CP2K: An electronic structure and molecular dynamics software package - Quickstep: efficient and accurate electronic structure calculations. J. Chem. Phys. 152, 194103 (2020).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Goedecker, S., Teter, M. & Hutter, J. Separable dual-space Gaussian pseudopotentials. Phys. Rev. B 54, 1703–1710 (1996).

Woon, D. E. & Dunning, T. H. Jr Gaussian basis sets for use in correlated molecular calculations. IV. Calculation of static electrical response properties. J. Chem. Phys. 100, 2975–2988 (1994).

Trygubenko, S. A. & Wales, D. J. A doubly nudged elastic band method for finding transition states. J. Chem. Phys. 120, 2082–2094 (2004).

Poullikkas, A. Optimization algorithm for reverse osmosis desalination economics. Desalination 133, 75–81 (2001).

Strathmann, H., Grabowski, A. & Eigenberger, G. Ion-exchange membranes in the chemical process industry. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 52, 10364–10379 (2013).

Lei, C. et al. Comparative study on the production of gluconic acid by electrodialysis and bipolar membrane electrodialysis: effects of cell configurations. J. Membr. Sci. 608, 118192 (2020).

Li, W.-W., Yu, H.-Q. & He, Z. Towards sustainable wastewater treatment by using microbial fuel cells-centered technologies. Energy Environ. Sci. 7, 911–924 (2014).

Yee, R. S. L., Rozendal, R. A., Zhang, K. & Ladewig, B. P. Cost effective cation exchange membranes: a review. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 90, 950–959 (2012).

Guidelines for Preparing Economic Analyses. (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2010).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the financial support from the Geothermal Technologies Office in the U.S. Department of Energy via the Geothermal Lithium Extraction Prize, as well as a University Facilitating Fund (UFF), a startup fund, and a Technology Maturation Award (TMA) of X.L. received from the George Washington University. High-performance computing resources were provided by the Texas Advanced Computing Center (TACC) at the University of Texas at Austin on the Frontera supercomputer.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.L. conceived the idea. X.L., L.K., and C.L. designed the research. L.K., Y.Y., and N.C. conducted the sample preparation and experiments. L.K., G.Y., and K.M. conducted materials characterization. K.H. conducted the techno-economic analysis. H.C. carried out and interpreted the density functional theory (DFT) simulation. L.K. and X.L. conducted data analysis and wrote the paper. M.W. and C.L. supervised the materials characterization. S.B. supervised the crystallization experiments. X.L. supervised the work. All authors provided feedback and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

L.K. and X.L. declare competing interests: Aspects of the work reported in this article are the subject of a pending patent application (Xitong Liu and Lingchen Kong, Chemical free extraction of lithium from brine, Application No. PCT/US23/74577) filed by George Washington University (Washington DC, United States). The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Lena Kölbel, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kong, L., Yan, G., Hu, K. et al. Electro-driven direct lithium extraction from geothermal brines to generate battery-grade lithium hydroxide. Nat Commun 16, 806 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56071-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56071-x

This article is cited by

-

Membrane and electrochemical separations for direct lithium extraction

Nature Chemical Engineering (2025)

-

Lithium resources and novel strategies for their extraction and purification

npj Materials Sustainability (2025)