Abstract

The takeover issue, especially the setting of the takeover time budget, is a critical factor restricting the implementation and development of conditionally automated vehicles. The general fixed takeover time budget has certain limitations, as it does not take into account the driver’s non-driving behaviors. Here, we propose an intelligent takeover assistance system consisting of all-round sensing gloves, a non-driving behavior identification module, and a takeover time budget determination module. All-round sensing gloves based on triboelectric sensors seamlessly detect delicate motions of hands and interactions between hands and other objects, and then transfer the electrical signals to the non-driving behavior identification module, which achieves an accuracy of 94.72% for six non-driving behaviors. Finally, combining the identification result and its corresponding minimum takeover time budget obtained through the takeover time budget determination module, our system dynamically adjusts the takeover time budget based on the driver’s current non-driving behavior, significantly improving takeover performance in terms of safety and stability. Our work presents a potential value in the application and implementation of conditionally automated vehicles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

According to J3016_202104 published by the Society of automotive engineers (SAE), driving automation falls into six levels, ranging from no automated to fully automated, namely, no driving automation (L0), driver assistance (L1), partial driving automation (L2), conditional driving automation (L3), high driving automation (L4), and full driving (L5)1. As more and more mass-produced vehicles are equipped with a series of advanced auxiliary driving systems such as adaptive cruise control (ACC) systems, lane keeping assist (LKA) systems, and autonomous emergency braking (AEB) systems, the development of L1 and L2 driving automation systems is becoming increasingly mature2. However, limited by the current technological development, infrastructure construction, relevant regulations and legislation, ethics, and other factors, L4 and L5 driving automation systems cannot be realized and implemented in the short term3. As a result, L3 considered to be the key to the leap from low-level to high-level driving automation systems, has received widespread attention and is key research object of current autonomous driving systems4. As for the L3 driving automation system, the takeover is a key issue5,6. If the takeover issue can be effectively addressed, it will greatly promote the implementation and popularization of the L3 driving automation system and lay a solid technical reserve and foundation for L4 and L5 driving automation systems.

Unlike L0, L1, and L2 driving automation systems, when the L3 driving automation system is running, the driving subject shifts from the driver to the driving automation system7. Because of this change in the role of drivers, drivers no longer need to participate in or monitor driving tasks all the time. At this time, drivers intend to perform various types of non-driving behaviors, such as playing with smartphones, interacting with console pads, and so on8,9,10. Nonetheless, when the L3 driving automation system launches the takeover request (TOR) due to its failure to continue operating under the defined conditions, the driver must respond quickly to the TOR for intervention within a limited time (takeover time budget (TOTB))11,12. During this time, drivers need to withdraw from non-driving behaviors to take over control of the vehicle and ensure safe driving of the vehicle. In current studies, TOTB is set to a fixed duration13,14, but this setting is not reasonable. Taking the TOTB set to 6 s as an example, when an emergency occurs, and the driver is supposed to take over the vehicle, the L3 driving automation system believes that the driver has enough time to complete the takeover task within 6 s smoothly, so it is appropriate to issue TOR 6 s in advance. Considering of variety and diversity of non-driving behaviors and varied degrees of driver immersion in different non-driving behaviors15, TOTB set to 6 s may be redundant for some non-driving behaviors such as a driver holding the steering wheel, but it is not enough for other non-driving behaviors like playing games on the smartphone16. Insufficient TOTB will greatly affect the quality of the takeover and even lead to traffic accidents, and, in severe cases, casualties17. Therefore, it is of great necessity for the L3 driving automation system to perceive the non-driving behavior currently performed by the driver in real-time and the minimum TOTB it requires, so that when an emergency takeover occurs, the L3 driving automation system can dynamically adjust the TOTB or take some emergency response measures (for the specific situation when the time to crush less than minimum TOTB, drivers are unable to safely complete the takeover), making the L3 driving automation system safer and smarter than ever. It can be seen that the L3 driving automation system’s real-time identification of non-driving behaviors and dynamic adjustment of TOTB based on different non-driving behaviors are essential for overcoming the takeover dilemma.

To dynamically adjust TOTB, the L3 driving automation system first needs to identify non-driving behaviors in real-time. Currently, the sensors used to identify non-driving behaviors mainly fall into two categories: contacting sensors and non-contact sensors. Cameras are the most widely used and representative non-contact sensors. The advantage of cameras is that it does not interfere with the driver or affect the driver’s normal operation. However, the intensity of light, the bumpiness of the vehicle, and blocking objects lay varying degrees of interference to cameras18,19. Furthermore, for privacy reasons, drivers may not be willing to be monitored by cameras, or they may avoid camera surveillance in some way20. Physiological acquisition devices such as electrocardiogram (ECG), electroencephalogram (EEG), and electromyography (EMG) are representative non-contact sensors21,22,23,24, which are not susceptible to environmental factors. Yet physiological acquisition devices cause great interference and discomfort to drivers, and they cannot effectively and accurately identify diverse non-driving behaviors25. Due to the compelling characteristics of simple manufacturing, high scalability, self-power, low-power consumption, high sensitivity, and environmental friendliness, triboelectric nanogenerators (TENGs)26,27, invented in 2012, have been widely used in biomechanical energy harvesting28,29,30, health monitoring31,32,33,34, human-machine interaction (HMI)35,36,37,38, human motion tracking39,40,41, etc. Considering that hands are the main expression carrier of non-driving behaviors and the progress TENGs have made in finger movement tracking42,43,44, hand gesture recognition45,46,47,48, sign language recognition49,50, tactile perception51,52,53, etc. TENGs, with their high sensitivity and micro-scale motion detection capability, show great potential in the identification of non-driving behaviors.

This study develops an intelligent takeover assistance system (ITAS) to enable the L3 driving automation system to identify the driver’s non-driving behaviors in real time and dynamically match the TOTB based on different non-driving behaviors. First, we design all-round sensing gloves (AS-Gloves) with flexible, high-sensitivity, fast-response, and low-power triboelectric sensors, which enable the AS-Gloves to capture the driver’s hand movements and hand interaction information between hands and other objects in the vehicle without affecting driver’s operations or causing discomfort. Then real-time non-driving behavior identification module with a time-distributed CNN-LSTM (TCNN-LSTM) model based on deep learning is introduced to deal with the diversity, complexity, variability, and individual difference of signals generated by AS-Gloves to identify non-driving behaviors. Meanwhile, during the model training, by leveraging Recursive Feature Addition (RFA), we explore changes in model identification accuracy with different combinations of triboelectric sensors on the AS-Gloves. Based on the identification accuracy of target non-driving behaviors, we, in turn, optimize the configuration of the AS-Gloves. Subsequently, through a series of personalized exploratory experiments, the minimum takeover time budget (TOTB) required by the driver when performing non-driving behaviors is determined. Finally, combined with the minimum TOTB, our ITAS can dynamically adjust the TOTB on the basis of the driver’s current non-driving behaviors in real time. This work makes it possible for the L3 driving automation system to be smarter and safer when facing an emergency takeover and also further promotes the implementation and application of conditionally automated vehicles.

Results

Design of the intelligent takeover assistance system

We propose an intelligent takeover assistance system (ITAS) that incorporates three parts, AS-Gloves, a real-time non-driving identification module, and a TOTB determination module, as shown in Fig. 1. AS-Gloves integrate triboelectric sensors not only to perceive the movements of the hand itself but also the interaction between the hands and other in-vehicle objects. When the driver performs certain non-driving behavior, the AS-Gloves generate a series of electrical signals. With electrical signals generated by the AS-Gloves, calculations are performed inside a real-time non-driving identification module, leading to the identification result. According to the identification result and required minimum TOTB determined by the TOTB determination module, ITAS dynamically matches TOTB under the current non-driving behavior to ensure the safe operation of the vehicle. One can take a driver drinking a bottle of water as an example. When he or she is drinking water, his or her hand movement can be detected and captured by triboelectric sensors integrated AS-Gloves, which generate a series of electrical signals. A microcontroller unit (MCU), Arduino Nano, with embedded analog-to-digital (ADC) converters, reads out electrical signals generated by AS-Gloves and then transfers those signals to the real-time non-driving identification module. Subsequently, a deep learning-assisted TCNN-LSTM model inside the real-time non-driving identification module identifies the driver as drinking, and the TOTB determination module determines the minimum TOTB required for drinking. According to the current non-driving behavior─drinking and its required minimum TOTB, ITAS dynamically adjusts TOTB in real time. Compared to the vehicles that currently give a fixed TOTB regardless of the driver’s non-driving behaviors, the vehicles mounted with our ITAS are capable of dynamically adjusting TOR based on the driver’s non-driving behaviors, which greatly improves the safety of takeover for L3 driving automation system.

Design and characterization of F-TENG and all-round sensing gloves

For the sake of capturing delicate hand movements and interactions between hands and other objects in the vehicle without causing much interference to drivers, the triboelectric sensors integrated into the AS-Gloves need to meet multiple requirements to ensure their functionality and performance. First, the sensor must be lightweight, soft, and stretchable to provide driver comfort, and wearability. These properties enable the AS-Gloves to naturally coordinate with hand movements without causing discomfort and interference with the driving task. Meanwhile, it is crucial to ensure that triboelectric sensors with low-power consumption to extend sensors’ lifespan, reduce maintenance costs, and minimize the environmental impact of battery pollutants. Additionally, AS-Gloves intended for non-driving behaviors identification of drivers require sensors with high sensitivity to capture subtle movements of hands. Finally, low latency (response time) is also necessary to meet real-time requirements for the dynamic decision of ITAS.

Based on the described requirements, we employed a simple process to create a flexible triboelectric nanogenerator (F-TENG) with high sensitivity, rapid response, and low-power consumption. The friction layer of the F-TENG utilizes silicone doped with BaTiO3 nanoparticles (BT NPs), with embedded branching silver fibers serving as the collection electrode. The detailed production process can be found in Supplementary Note 1. To enhance the electrical output performance of the F-TENG, we explored and optimized three key parameters involved in fabricating TENG, including the doping ratio of BT NPs, the number of branches in silver fibers, and the proportion of surface structure. Through experimental results shown in Supplementary Note 2, it was found that the performance was best when the doping ratio of BT NPs was 10%, the number of branches in silver fibers was 3, and the proportion of surface structure was 40%. Subsequently, F-TENG made with this parameter was selected as the basic sensing unit for AS-Gloves. The electrical signal generation principle of F-TENG is based on the coupling of frictional electrification and electrostatic induction (For details, please refer to Supplementary Note 3). Moreover, we verified the basic electrical performance of the F-TENG. Firstly, we investigated the impact of frequency on the F-TENG electrical signal, as shown in Fig. 2a, b. The results indicate that short-circuit current increases with frequency, while open-circuit voltage remains almost constant at different frequencies. Subsequently, we validated the performance of the F-TENG sensor under different environmental conditions, including temperature and humidity. As shown in Fig. 2c, with increasing humidity, the voltage gradually decreases, reducing by ~50%. Conversely, with rising temperatures, the voltage increases by around 17%. Although the F-TENG is influenced to some extent by temperature and humidity, our subsequent data collection and algorithm construction fully considered the impact caused by temperature and humidity. Furthermore, the sensitivity of F-TENG under different pressures is shown in Fig. 2d. The F-TENG exhibits different linear response trends in various pressure ranges. In the 0–3.5 N range, the R2 value is 0.99788, and the sensitivity is 3.257 V/N. In the 3.5–6 N range, the R2 value is 0.99902, with a sensitivity of 0.706 V/N. To verify the low-power consumption performance of the F-TENG, we connected resistors of different values to the F-TENG, measuring the load voltage, current, and power output, as shown in Fig. 2e, f. When the resistor value is 16 MΩ, the output power reaches its maximum value at 4.59 mW, with a voltage of 8.57 V and a current of 0.53 μA. Finally, we tested the durability of the F-TENG by subjecting it to 25,000 impact tests using a linear motor. The results, provided in Supplementary Note 4, indicate no significant attenuation in the voltage amplitude.

a, b The impact of frequency on F-TENG’s short-circuit current (Isc) and open-circuit voltage (Voc). c The influence of temperature and humidity on the output performance of F-TENG. d Linear relationship between applied force and F-TENG Voc. e, f As the external load increases, the trend of changes in voltage, current, and power of F-TENG. g Comparison of Voc amplitude generated by contact between F-TENG and different vehicle materials. h The impact of initial distance between F-TENG and electronic screen on Voc. i The trend of F-TENG Voc as the touch screen intensity increases and j The differences in F-TENG Voc caused by the speed change of touching the screen, the illustration shows the response time of F-TENG when touched at normal speed. k, l The Voc waveform corresponds to bending angle and bending speed.

Generally, hand movements of drivers’ non-driving behaviors fall into three categories, finger bending, interaction with fingertips, and interaction with palm, respectively. Accordingly, five triboelectric sensors are placed on the knuckles of the AS-Glove for finger bending detection, five triboelectric sensors are fastened to fingertips for fingertip interaction perception. One triboelectric sensor, meanwhile, is mounted on the palm and used for the measurement of palm interaction. The specific design information of the AS-Gloves can be found in Supplementary Note 5. Figure 2g shows the electrical characteristics of the F-TENG contacting with five types of common objects in vehicles, including fabric, iron products, electronic screens, leather, and plastic bottles. The arranged order of voltage from low to high corresponds to fabric, iron products, electronic screens, leather, and plastic bottles. To validate the performance of the AS-Gloves in terms of interaction, we used an electronic screen as the touched object and investigated the impact of distance, force, and speed on the electrical signals. Figure 2h illustrates the relationship between distance and voltage, indicating an increase in voltage with an initial increase in distance, and after the initial distance exceeds 30 mm, the voltage stabilizes. Figure 2i displays voltage waveforms when touching the electronic screen with different force intensities, showing an increase in voltage amplitude with increasing force. Figure 2j demonstrates the relationship between touch speed and voltage, revealing that higher touch speeds result in larger voltage amplitudes, accompanied by a shorter response time. The corresponding voltage integration remains constant, which can be utilized for measuring sustained force, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 6a. The illustration in Fig. 2j exhibits a response time of 27.4 ms during normal-speed touch, demonstrating its compliance with real-time requirements. Additionally, we investigated the relationship between joint bending angles and voltage, as depicted in Fig. 2k. The results indicate that larger bending angles correspond to higher voltage amplitudes. Simultaneously, as the bending speed increases, the voltage amplitude also increases, while the voltage integration remains constant, as shown in Fig. 2l and Supplementary Fig. 6b. By combining these 11 sensors, we demonstrated the ability of AS-Gloves for gesture recognition, as shown in Supplementary Note 7.

The above design and characterization endow our AS-Gloves with the capability of capturing the hand movements and interaction information between hands and other objects, laying a foundation for identifying the driver’s non-driving behaviors in real time.

Experiments and data collection

Considering the role change of the driver in conditionally automated (L3) vehicles, the driver no longer needs to monitor the vehicle driving as before. Instead, drivers will pay more attention to non-driving behaviors54. Here, we adopted six representative non-driving behaviors55, four of which are frequently found in previous studies on non-driving behaviors, namely interacting with the phone (denoted as Phone), interacting with the console touchpad (denoted as Console), holding the steering wheel to monitor driving (denoted as Wheel), and doing nothing (denoted as No Operation)1,2,3,4, and the remaining two are frequently found in daily driving, namely smoking (denoted as Smoke), drinking a bottle of water (denoted as Drink). The above six types of non-driving behaviors not only involve hand movements and interaction with other objects but also impact drivers at different levels when drivers are immersed in these six types of non-driving behaviors. These six non-driving behaviors are described in detail below:

Phone: Interacting with the phone comprises two subcategories, Phone (Tap) and Phone (Scroll). For Phone (Tap), participants need to text someone by tapping through WeChat. As for Phone (Scroll), participants are assigned to scroll through TikTok.

Smoke: Participants are required to smoke with an e-cigarette, and the entire process includes picking up and putting down the e-cigarette.

Drink: Participants are asked to pick up the bottle of water, take a sip, and return the bottle to its original position.

Console: Like the Phone, the Console also contains two subcategories, namely Console (Tap) and Console (Scroll). For Console (Tap), participants are requested to input Beijing Institute of Technology by tapping on the navigation system of the console touchpad. The console (Scroll) needs participants to scroll on the map to locate a certain place through the console touchpad.

Wheel: Participants are told to hold the steering wheel with both hands and monitor vehicle driving and external situations.

No Operation: Participants are supposed to place their hands still on their legs.

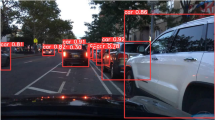

Aiming to build a generalized non-driving behavior identification model, 40 participants, 24 males and 16 females, ranging from 22 to 35 years of age (mean = 27.35, SD = 2.33) with valid Chinese driving licenses were recruited via online WeChat posters. Participants reported that they usually drive 3 to 10 times per week (mean = 5.625, SD = 2.24), and have a range from 4 to 11 years of driving experience (mean = 5.93, SD = 1.60). Half of the participants (20 participants) were asked to wear the AS-Gloves to conduct the experiment in a simulated driving environment, and the other half were asked to complete the experiment in a real car environment. Above experiments are named non-driving behavior data acquisition experiment (Experiment A). Figure 3a illustrates the real car experiment platform, including an electric vehicle, AS-Gloves, and signal acquisition devices (Arduino Uno and laptop). Figure 3b shows the simulated driving experiment platform, including a driving simulator (visualization of driving scenarios, steering wheel, and pedals), AS-Gloves, and signal acquisition devices (Arduino Uno and laptop). For both real car experiments and simulated experiments, the experiments last approximately 60 min. Before the formal start of the experiments, participants had 20 min to familiarize themselves with driving simulator or the power response system of the electric vehicle. During the experiments, participants first performed six non-driving behaviors (including Phone, Smoking, Drinking, Console, Wheel, and No Operation) with their left hand according to random verbal instructions, and then performed these behaviors with their right hand. The simulated experiments were conducted in a simulated environment without any risk via a driving simulator supported by SCANeR studio. The real car experiments were completed at a closed, interference-free site (a 400 × 500 m open space). Throughout the real car experiments, the vehicle had to maintain a low speed, and a safety officer was arranged to be the co-pilot to ensure experiment safety. Simultaneously, AS-Gloves worn on hands did not cause any health issues and participants were entitled to terminate the experiment at any time according to their wishes.

The electrical signals generated by No Operation, Drink, Smoke, Wheel, Console, and Phone, respectively, in a simulated driving environment are shown in Fig. 3c–h and Supplementary Movie 1 (see Supplementary Fig. 8 and Supplementary Movie 2 for real car environment). There is no obvious fluctuation in the electrical signals of No Operation. The electrical signals of the Wheel share similarities with No Operation, but there are some subtle fluctuations. For Drink and Smoke, the amplitude, holding time, and frequency of the electrical signals are reflected to varying degrees with the behavior. Console contains two sub-behaviors, Console (tap) and Console(scroll). The electrical signals of Console (tap) and Console (scroll) show a similar overall trend, however, the amplitude of Console (scroll) is larger than Console(tap). The electrical signals of the Phone are similar to those of the Console.

Real-time non-driving behavior identification module

Some typical features of F-TENGs, such as amplitude, frequency, holding time, etc., manually extracted from the frequency domain and time domain, can describe non-driving behaviors to a certain extent. However, considering the complexity, variability, environmental factors (temperature, humidity, etc.), and individual differences of non-driving behaviors56,57,58, traditional manually extracted features are too shallow to characterize intact patterns of non-driving behaviors, especially in the temporal dimension. In addition, fundamentally, the manually extracted features from the time domain and frequency domain are calculated in a sensor-wise manner. In other words, the manually extracted time domain and frequency domain features are calculated individually on each sensor, rather than integrating all sensors into one organism and calculating them. Therefore, the spatial correlation between the sensors will be overlooked. When completing non-driving behaviors, there are often a bunch of synergies as well as linkages between the knuckles, fingers, and palms. The spatial correlation of these synergies and linkages is crucial to identify non-driving behaviors. Since the manually extracted features lack spatial correlation and deep features in the time and frequency domain are not capable of comprehensively characterizing non-driving behaviors, it is necessary to introduce deep learning algorithms to extract deep features to accomplish the identification of non-driving behaviors.

To effectively identify non-driving behaviors, we propose a real-time non-driving behavior identification model based on deep learning. This model is a general non-driving behavior identification model, which enables the vehicle to effectively identify any drive’s non-driving behavior, rather than spending a lot of time training the model for each driver. Figure 4a schematically illustrates the processing flow of our real-time non-driving behavior identification model in both the training stage and practical identification stage for real-time data. As for the training stage, the model consists of four modules, namely, data preprocessing, dataset, model training, and AS-Gloves optimization. With a series of sub-modules, data preprocessing is conducted to convert raw data from F-TENGs on AS-Gloves to image data, which are suitable for further dataset \(\left(X,\,Y\right)\) construction and model training. Next, the supervised deep learning algorithm model starts training with Dataset \(\left(X,\,Y\right)\). Finally, AS-Gloves optimization is set to screen F-TENGs with lower or negative contributions to the accuracy of non-driving behavior identification and improve the real-time nature of the model.

a Schematic diagram of the overall workflow of the real-time non-driving behavior identification module in both the training stage and practical identification stage. b Structure of detailed TCNN-LSTM model. c Results of AS-Gloves optimization through RFA. d The confusion matrix for identification accuracy of six non-driving behaviors.

Data preprocessing incorporates five sub-modules, which are low-pass filter, data fusion, normalization, sliding window, and image representation. A low-pass filter with a cutoff frequency of 20 Hz is used to attenuate noisy and redundant data, which are harmful to follow-up model training. A comparison of signals before and after the low-pass filter is shown in Supplementary Fig. 9. To dig deeper into the spatial correlation between fingers, knuckles, and the palm, we fuse the data of 11 F-TENGs. Since the F-TENGs involved in the AS-Gloves are homogeneous, connected in parallel, and measuring the same non-driving behavior, data of each F-TENG can be fused directly at the data level. Concretely, this data fusion process is conducted by a general concatenation function as shown in Eq. (1):

Where \({D}_{1},{D}_{2},{D}_{3},{D}_{4},{D}_{5}\) stand for data of F-TENGs on the knuckle of small finger, ring finger, middle finger, index finger, and thumb, respectively. \({D}_{6},{D}_{7},{D}_{8},{D}_{9},{D}_{10}\) are data of F-TENGs on the fingertips of small finger, ring finger, middle finger, index finger, and thumb, respectively. \({D}_{11}\) refers to F-TENG data gathered from the palm. Given a sequence of F-TENG data \({D}_{j}=\{{d}_{1},{d}_{2},\cdots,{d}_{n}\}\) including n samples, the normalization process is applied for different sensors separately using the following Eqs. (2), (3), (4):

Wherein, \(\mu\), \(\sigma\) represent the mean and standard deviation of \({D}_{j}\) respectively, and n represents the number of samples of \({D}_{j}\). With the help of a sliding window, the data of F-TENGs are converted to a set of samples. The label of each sample is determined by the image information corresponding to the last moment of \({D}_{j}\). Window width (W) and stride (S) are two hyperparameters, the optimal value of which will be determined in subsequent model training. Different from some previous works, where the data of the sensor are directly plotted as a graph and then used as input in the form of an image file for model training59. We first plot each sample as a line chart and then further divide each sample equally into m (m is a hyperparameter determined in model training) frames, which simulates the progressive process of generating a line chart from F-TENGs and provides more context information among the sample as a basis for subsequent model to seize deep features in the temporal dimension. Compared with the traditional method of throwing images directly into model training, this segmentation method is more effective.

The raw data of F-TENGs are passed through the data preprocessing module to obtain the dataset \(\left(X,\,Y\right)\) as shown in Eqs. (5), (6):

wherein \(X=\{{x}_{1},{x}_{2},\cdots,{x}_{n}\}\) represents a total of n samples, and \({x}_{i}=\{{x}_{i}^{1},{x}_{i}^{2},\cdots,{x}_{i}^{m}\}\) indicates m frames are involved within a single sample. \(Y=\{{y}_{1},{y}_{2},\cdots,{y}_{n}\}\) is a set of labels corresponding to n samples in \(X\), and six values of \({y}_{i}\in \{0,1,2,3,4,5\}\) correspond to six kinds of non-driving behaviors, respectively. Specifically, 0 denotes Phone, 1 denotes Console, 2 denotes Drink, 3 denotes Smoke, 4 denotes No Operation, and 5 denotes Wheel.

Unlike some past works, where a sequence of sensor signals directly used as input data or plotted as input images are passed into deep convolutional neural networks (DCNN)60 or deep long-short term memory (LSTM)61 to train from scratch or predict using pre-trained weights by transfer learning. In this paper, we propose a novel deep network named time-distributed CNN-LSTM networks (TCNN-LSTM), wherein combines CNN and LSTM networks. Through CNN networks, deep local features can be effectively extracted by convolution kernels from low-level to high-level, and have good spatial invariance. However, these ordinary CNN networks lack the ability to mine the time domain correlation in sensor signals. To prevent the CNN networks from missing important information in the time domain, time-distributed CNN networks wrapping the ordinary CNN networks up in a time-distributed layer fulfills CNN networks with the capability of extracting important information in both spatial correlation and time domain. Besides, we introduce bidirectional LSTM to further extract information in the temporal dimension. Figure 4b illustrates the schematic diagram of the TCNN-LSTM structure in detail, and the specific parameters of the feature layer are presented in Supplementary Table 1.

We initially designed AS-Glove with 11 F-TENG sensors to capture the bending-stretching, contact-separation information of the hand in a round way. However, 11 sensors are not necessarily the best, the raw data collected by 11 F-TENG sensors as raw features may have high redundancy among features, leading to the following results62,63: (1) Redundant features increase the complexity of the model and may lead to overfitting, that is, the model performs well on the training set but poorly on the test set, leading to a decrease in accuracy of identification. (2) Redundant features may also affect the generalization ability of the model, making it unable to correctly predict new data, resulting in a decline in the accuracy of identification. (3) Redundant features increase computational costs. Therefore, in order to eliminate redundant features and improve the real-time performance of the model and the comfort of the drivers’ hands, we further perform recursive feature addition (RFA)64 on 11 F-TENGs of the AS-Glove. Details of model performance with different numbers of F-TENGs are shown in Fig. 4c. When there are seven F-TENGs (index finger, thumb knuckle, middle finger, thumb finger, index knuckle, palm, and middle knuckle) of the AS-Glove, the model achieves the highest identification accuracy under the optimal hyperparameter combination (width (W) = 10, stride (S) = 5, and number of frames (m) = 2), reaching an average of 94.72% and an average F1 of 0.949 (see details in Supplementary Table 2). The identification accuracy under different hyperparameter combinations is described in Supplementary Note 8. Figure 4d is the confusion matrix of the identification result among 6 non-driving behaviors. The total identification accuracy of the model is 94.72%, while each behavior possesses a different identification accuracy on the diagonal. The identification accuracy of Console, Phone, Drink, and Smoke all exceeds 95%, however, No Operation and Wheel show relatively lower accuracy, 93 and 91%, respectively.

In summary, after RFA, a total of seven F-TENGs on the index finger, thumb knuckle, middle finger, thumb finger, index knuckle, palm, and middle knuckle, respectively are retained. The proposed TCNN-LSTM networks achieve an accuracy of 94.72%, showing a great capability of identifying non-driving behaviors.

Minimum TOTB determination module and application of ITAS

When a driver withdraws from non-driving behaviors, it takes a period of time to restore situation awareness (SA), physical preparation, and a series of preparations before he or she is able to complete the takeover65. However, this period of time varies with the driver’s engagement and immersion in different non-driving behaviors56,57,58. A universal TOTB solution for all drivers is susceptible to individual factors such as age, gender, driving experience, automation familiarity, habits, occupation, and personality. These numerous variations can significantly impact TOTB, making practical application difficult. Therefore, it is necessary to find the tailored minimum TOTB for each driver corresponding to different non-driving behaviors. Then, an experiment (Experiment B), including the takeover event, is designed. The experiment is based on a two-way four-lane highway with a lane width of 3.75 m and a median width of 2.0 m. To restore the real road scene as much as possible, trees, buildings, and traffic signs are arranged on both sides of the road. The fixed obstacle ahead scenario has attracted much attention in the above studies due to its high degree of danger and urgency66. In addition, the fixed obstacle ahead scenario also accounts for a high proportion of takeover events in the public self-driving car test reports. As a result, we constructed the takeover scenario with fixed obstacles ahead (accident vehicle).

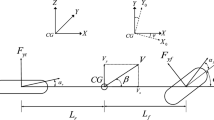

Figure 5a describes the whole process of the takeover event in detail. The experiment is composed of three stages. During Stage I, the ego-vehicle with the L3 driving automation system activates auto-drive mode. The ego-vehicle accelerates from 0 to 100 km/h and travels at a constant speed of 100 km/h. At this time, participants do not need to control the ego-vehicle and are allowed to take their eyes off the road and hands and feet off the ego-vehicle’s input devices such as the wheel and pedals. When audio instruction sounds, participants are designated to perform one of the seven non-driving behaviors (Smoking, Drinking, Phone, Console, Wheel, No Operation, Phone & Smoke). Detailed descriptions of the seven non-driving behaviors can be found in Supplementary Note 9. This is to ensure that when the L3 driving automation system issues a TOR to participants, the participants are performing specific non-driving behaviors to guarantee the validity of the sample. In Stage II, when the Time to Collision (TTC) between the ego-vehicle and the stationary broken vehicle ahead reaches the pre-set TOTB, the L3 driving automation system launches a TOR in the form of beeps to simulate system-limit failure or system-malfunction failure. After the TOR is issued, the participants need to take over control of the ego-vehicle and change lanes to the left to avoid the broken vehicle in the same lane ahead. After participants complete the takeover event, they are asked to return control to the L3 driving automation system through one-click switching. At this stage, the experiment enters Stage III. The L3 driving automation system drives the ego-vehicle until the end of the experiment. Before the formal experiment, participants need thorough training to become skilled in the procedures of taking over with and without AS-Gloves. This training should also include mastering the takeover procedures under the six different non-driving behaviors in this study. Sufficient practice is crucial to reduce the negative impact of the learning effect on the experimental results.

a An illustration of the flow of takeover experiment. b–d Takeover performance of non-driving behaviors (including Wheel, No Operation, Console, Smoke, Drink, Phone, Phone, and Smoke) under different TOTBs of Participants A, B, and C. e The interface of ITAS. f–h Comparison of takeover performance of three participants in conditions with and without ITAS.

To determine the minimum TOTB for each participant corresponding to different non-driving behaviors, a total of 24 participants recruited through online WeChat push were asked to complete a series of takeover experiments containing six non-driving behaviors. For each non-driving behavior, the TOTB of the takeover experiment starts from 3 s and gradually increases in units of one second until the takeover performance of three consecutive experiments no longer increases significantly. Previous studies have shown that these four indicators, minimum time to collision (TTC), maximum lateral acceleration (MLA), maximum longitudinal deceleration (MLD), and lane excursion (LE), can effectively evaluate the takeover performance of fixed obstacle scenes67. In this study, four indicators (TTC, MLA, MLD, and LE) are selected for evaluation of the takeover performance from both safety and stability aspects (Details of the takeover performance evaluation method based on these four indicators are given in Supplementary Note 10). Among these four indicators, the safety evaluation corresponds to minimum TTC, and the stability evaluation corresponds to MLA, MLD, and LE. Based on the above four indicators, takeover performance is further calculated by following Eq. (7):

where \(\sigma\) stands for min-max normalization function.

First, minimum TTC is used to evaluate whether the takeover failed from a safety perspective. When the minimum TTC is less than 1 sec, it is deemed that the ego-vehicle has collided with the broken vehicle in front, and the takeover failed. At this time, the stability evaluation indicators are no longer meaningful, and the takeover performance is 0. On the premise of meeting the basic safety (when minimum TTC is greater than 1), takeover performance is calculated by summing the three stability indicators MLA, MLD, and LE after min-max normalization. Takeover performance ranges from 0 to 3, where 0 means the takeover fails and 3 means the takeover is very good. The minimum TOTB required by Participant 1 under seven non-driving behaviors (Wheel, No Operation, Console, Smoke, Drink, Phone, and Phone & Smoke) are 4, 5, 6, 6, 7, 8, and 11 s, respectively, as shown in Fig. 5b. The minimum TOTB required by Participant 2 under seven non-driving behaviors are 5 s, 5 s, 7 s, 8 s, 9 s, 9 s, and 11 s, respectively, as shown in Fig. 5c. The minimum TOTB required by Participant 3 under seven non-driving behavior are 4 s, 5 s, 6 s, 7 s, 8 s, 8 s, and 10 s, respectively, as shown in Fig. 5d. The minimum TOTB required by other 21 participants are shown in Supplementary Table 3 and Supplementary Fig. 11. It can be seen that the minimum TOTB required for different non-driving behaviors is different. As for the same non-driving behavior, the minimum TOTB required for different participants is also somewhat different.

After determining the minimum TOTB required for different non-driving behaviors, combining real-time non-driving behavior identification module and AS-Gloves, our ITAS is capable of dynamically adjusting the TOTB based on the driver’s current non-driving behavior. Figure 5e illustrates the interface of ITAS, which shows real-time electrical signals from optimized AS-Gloves, non-driving behavior identification results of left and right hands, drive mode of the vehicle, and dynamically matched TOTB (see Supplementary Movies 3–6). To verify the effectiveness of the system, comparative experiments (Experiment C) were conducted. Each participant was asked to complete 2 takeover tasks for each non-driving behavior with and without the ITAS. To prevent the learning effect, first, the takeover scenario remains the same as in minimum TOTB determination experiment, except that the fixed obstacle is changed from a broken vehicle to a construction road. Second, to counterbalance the impact of the sequence effect, the participants performed the 7 non-driving behaviors in the order sorted according to the Latin method, shown in the following Supplementary Information Table 4 (1 denotes Wheel, 2 denotes No Operation, 3 denotes Console, 4 denotes Smoke, 5 denotes Drink, 6 denotes Phone, and 7 denotes Phone & Smoke). In addition, considering the effectiveness of comparison, the order of the 7 non-driving behaviors with gloves and without gloves was consistent for each participant. The takeover performance of Participant 1, Participant 2, and Participant 3 is depicted in Fig. 5f–h. Paired samples T-test (see Supplementary Table 7) statistically shows that all participants with ITAS significantly (p < 0.05) improved the takeover performance than those without ITAS. This result indicates that, ITAS incorporated with AS-Gloves, a general non-driving behavior identification model, and a tailored minimum TOTB determination method is capable of enhancing takeover performance.

Discussion

The takeover issue is a key factor restricting the implementation and development of L3 autonomous vehicles. When the vehicle launches a takeover request (TOR), how much TOTB is left for the driver to complete the takeover becomes extremely important. Currently, TOTB in many takeover-related studies is set to a fixed value. However, considering the degree of immersion of drivers in performing different non-driving behaviors, drivers need different TOTB to complete takeover preparation, including situation awareness recovery, physical preparation, etc. Therefore, a fixed TOTB is still limited to the above situations. To enable the L3 driving automation system to dynamically adjust TOTB based on the driver’s current non-driving behavior, we developed an intelligent takeover assistance system (ITAS) containing three modules, namely all-round sensing gloves (AS-Gloves), non-driving behavior identification, and TOTB determination. Flexible triboelectric sensors (F-TENGs) operated in single-electrode mode on AS-Gloves seamlessly detected delicate motions of hands and interactions between hands and other objects. The working principles and fundamental properties of the F-TENGs, and characteristics of the AS-Gloves were investigated. Then the AS-Gloves transferred the electrical signals to the non-driving behavior identification module, which outputs the driver’s current non-driving behavior. A TCNN-LSTM model based on supervised learning was proposed and employed in the non-driving behavior identification module. Based on the training accuracy of TCNN-LSTM, we further optimized the configuration of AS-Gloves. Finally, the TCNN-LSTM model reaches an accuracy of 94.72% and an average F1 of 0.949 for six common non-driving behaviors. Combining the driver’s current non-driving behavior identified by the non-driving behavior identification module and his or her suitable TOTB, which was obtained through the tailored minimum TOTB determination module, corresponding to that non-driving behavior, ITAS dynamically adjusted TOTB based on the driver’s current non-driving behavior, significantly improving takeover performance in terms of safety and stability.

To ensure the effectiveness and generalization of the non-driving behavior identification model in real car environment, a large number of non-driving behavior data were collected in a real car. Given China’s current regulations requiring drivers to hold the steering wheel and focus on the road without engaging in non-driving behaviors, we selected a closed, interference-free site to simulate a real driving environment. For safety reasons, we have limited the randomness and spontaneity to a certain extent, and specified that the participant completes the above six representative non-driving behaviors. In addition, this paper built a supervised non-driving behavior identification model, which required a large number of evenly distributed samples with different labels. Therefore, we limited the randomness and spontaneity in order to effectively obtain a large number of evenly distributed samples with different labels. Meanwhile Considering that building a supervised deep learning algorithm-based non-driving behavior recognition model that can identify all possible non-driving behaviors requires collecting a large amount of training data covering various behaviors, this is difficult in practice. In this paper, when constructing the non-driving behavior identification model in this paper, we did select only six representative and common behavior categories, four of which were frequently found in previous studies on non-driving behaviors, and the remaining two were drinking and smoking, were frequently found in daily driving9,54,68.

In the future, we will try to develop more advanced triboelectric sensors to address environmental impacts such as temperature and humidity. As L3 autonomous vehicles and related regulations develop, we will enrich the categories of non-driving behaviors and takeover scenarios, and conduct spontaneous and less limited non-driving behavior data collection and attempt to carry out real-car takeover.

Methods

Participants of experiments

This paper mainly involves three experiments, namely Experiments A, B, and C. A total of 64 participants (39 males, with an average age of 27.44 years and an SD of 2.01 years) were recruited. 40 participants, 24 males and 16 females, ranging from 22 to 35 years of age (mean = 27.35, SD = 2.33) were recruited for Experiment A. Another 24 participants, 15 males, 9 females, ranging from 24 to 32 (mean = 27.58, SD = 2.63), took part in Experiment B and C. Informed consent approved by the Ethics Committee of Science and Technology, Shanghai University (YS 2023–275) was obtained from all participants. All participants participated in the experiment voluntarily. After the experiment, the participants could choose snacks as compensation.

Source of materials

Ecoflex 0030A and B were purchased from Guoyuan Silicone Company, Conductive silver fiber was supplied by Tech Silver Fiber Company, and BT NPs were bought from Bohuasi Nanotechnology Company. White gloves were purchased from JD.com.

Fabrication of F-TENG

Combine Ecoflex A and B in a 1:1 ratio in a beaker, ensuring thorough mixing to create an Ecoflex pre-solution. Introduce BT NPs into the beaker and mechanically stir for 3 min (maintaining a weight ratio of 10:1 for Ecoflex pre-solution to BT NPs). Place the mixture in a vacuum environment to eliminate bubbles, forming a well-mixed Ecoflex solution. Utilize a UV curing printer to create a surface structure template. Pour the mixed Ecoflex solution into the template, introducing branched conductive fibers into the solution. After allowing for natural air drying, carefully peel off the silicone composite film from the mold, yielding the fundamental unit of the F-TENG.

Performance measurements of F-TENG

To assess the temperature sensing capabilities of the F-TENG, we employed a precision heating plate to control the sensor’s temperature accurately. For evaluating humidity sensing features, we utilized an Acrylic square hood, a humidifier, and a humidity monitor. The humidifier regulated humidity levels within the square hood, while real-time humidity levels were monitored using the humidity monitor. The electrical characteristics of the F-TENG were recorded using the Keithley-6514 and displayed on an oscilloscope.

Characterization of F-TENG

The morphology and microstructure of samples were characterized with a Nikon electron microscope.

Fabrication of AS-Gloves

Create a 1 × 1 cm2 square aperture on the fingertips of the designated thumb and index finger on the AS-Gloves to facilitate subsequent interaction with the electronic screen. Attach the 1.5 × 1.5 cm2 F-TENG onto the fingertips of the AS-Gloves, ensuring the surface structure faces outward. Attach the 3.5 × 3.5 cm2 F-TENG onto the palm area of the AS-Gloves, with the surface structure facing outward. Attach the 1.5 × 4 cm2 F-TENG onto the finger joint on the back of the AS-Gloves, positioning the surface structure to face inward.

Data acquisition of AS-Gloves

All F-TENG on AS-Gloves were interconnected with an Arduino multi-channel data acquisition device, which, in turn, was connected to a laptop.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All technical details for producing the figures are enclosed in Methods and Supplementary Information. The data generated in this study are provided in the Supplementary Information/Source Data file. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

All codes are for academic use only and available on Code Ocean: https://doi.org/10.24433/CO.9781291.v1.

References

S. A. E. Taxonomy and definitions for terms related to driving automation systems for on-road motor vehicles. Society of Automotive Engineers (2021).

Raposo, M. A. et al. Economic implications of a connected and automated mobility in Europe. Res. Transport. Econ. 92, 101072 (2022).

Li, S. et al. Remote driving as the failsafe: qualitative investigation of users’ perceptions and requirements towards the 5G-enabled level 4 automated vehicles. Transport. Res. F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 100, 211–230 (2024).

Dokic, J., Müller, B., Meyer, G., European roadmap smart systems for automated driving. Eur. Technol. Platform Smart Syst. Int. 39 (2015).

Naujoks, F. et al. Noncritical state transitions during conditionally automated driving on german freeways: effects of non–driving related tasks on takeover time and takeover quality. Hum. Factors 61, 596–613 (2019).

Claybrook J. & Kildare S. Autonomous vehicles: No driver… no regulation? Science 361, 36–37 (2018).

Kerschbaum, P., Lorenz, L. & Bengler, K. A transforming steering wheel for highly automated cars. In 2015 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV) 1287–1292 (2015).

Chen, F. et al. Are novice drivers competent to take over control from level 3 automated vehicles? A comparative study with experienced drivers. Transport. Res. F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 81, 65–81 (2021).

Zhang, B. et al. Determinants of take-over time from automated driving: a meta-analysis of 129 studies. Transport. Res. F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 64, 285–307 (2019).

Zeeb, K., Buchner, A. & Schrauf, M. Is take-over time all that matters? The impact of visual-cognitive load on driver take-over quality after conditionally automated driving. Accid. Anal. Prev. 92, 230–239, (2016).

Gold, C., Happee, R. & Bengler, K. Modeling take-over performance in level 3 conditionally automated vehicles. Accid. Anal. Prev. 116, 3–13 (2018).

Braunagel, C., Rosenstiel, W. & Kasneci, E. Ready for take-over? A new driver assistance system for an automated classification of driver take-over readiness. IEEE Intell. Transport. Syst. Mag. 9, 10–22 (2017).

Shahini, F. et al. Effects of unreliable automation, non-driving related task, and takeover time budget on drivers’ takeover performance and workload. Ergonomics 66, 182–197 (2023).

Gong, J. et al. Measuring takeover performance in different driving scenarios: considering the influence of non-driving-related tasks and takeover request lead time. Transport. Res. F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 97, 411–421 (2023).

Du, N. et al. Predicting driver takeover performance in conditionally automated driving. Accid. Anal. Prev. 148, 105748 (2020).

Lu, Z., Coster, X. & De, J. How much time do drivers need to obtain situation awareness? A laboratory-based study of automated driving. Appl. Ergonomics 60, 293–304 (2017).

Ayoub, J. et al. Predicting driver takeover time in conditionally automated driving. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transport. Syst. 23, 9580–9589 (2022).

Kańtoch, E. & Augustyniak, P. Human activity surveillance based on wearable body sensor network. Comput. Cardiol. 39, 325–328 (2012).

Zhang, H. D. et al. Detection of driving actions on steering wheel using triboelectric nanogenerator via machine learning. Nano Energy 79, 105455 (2021).

Koesdwiady, A. et al. Recent trends in driver safety monitoring systems: state of the art and challenges. IEEE Trans. veh. Technol. 66, 4550–4563 (2016).

Huang, J., Liu, Y. & Peng, X. Recognition of driver’s mental workload based on physiological signals, a comparative study. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 71, 103094 (2022).

Chen, J. et al. Driver vigilance detection for high-speed rail using fusion of multiple physiological signals and deep learning. Appl. Soft Comput. 123, 108982 (2022).

Fan, Y. et al. SafeDriving: an effective abnormal driving behavior detection system based on EMG signals. IEEE Internet Things J. 9, 12338–12350 (2021).

Wang, D. et al. Detection of the driver’s mental workload level in smart and autonomous systems using physiological signals. Math. Prob. Eng. 19, 1–13 (2022).

Esposito, D. et al. A piezoresistive array armband with reduced number of sensors for hand gesture recognition. Front. Neurorobotics 13, 114 (2020).

Zhu, G. et al. Triboelectric-generator-driven pulse electrodeposition for micropatterning. Nano Lett. 12, 4960–4965 (2012).

Fan, F. R., Tian, Z. Q. & Wang, Z. L. Flexible triboelectric generator. Nano Energy 1, 328–334 (2012).

Xia, X. et al. Metallic glass-based triboelectric nanogenerators. Nat. Commun. 14, 1023 (2023).

Xu, W. et al. A droplet-based electricity generator with high instantaneous power density. Nature 578, 392–396 (2020).

Tian, X. et al. 3D printing‐directed synergistic design of high‐performance zinc‐ion hybrid capacitors and nanogenerators for all‐in‐one self‐powered energy wristband. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2300381 (2023).

An, S. et al. Deep learning enabled neck motion detection using a triboelectric nanogenerator. ACS Nano 16, 9359–9367 (2022).

Sheng, F. et al. Ultrastretchable organogel/silicone fiber-helical sensors for self-powered implantable ligament strain monitoring. ACS Nano 16, 10958–10967 (2022).

Wei, C. et al. A self‐powered body motion sensing network integrated with multiple triboelectric fabrics for biometric gait recognition and auxiliary rehabilitation training. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2303562 (2023).

Zu, L. et al. Multiangle, self-powered sensor array for monitoring head impacts[J]. Sci. Adv. 9, eadg5152 (2023).

Lu, Y. et al. Decoding lip language using triboelectric sensors with deep learning. Nat. Commun. 13, 1401 (2022).

Pu, X. et al. Eye motion triggered self-powered mechnosensational communication system using triboelectric nanogenerator. Sci. Adv. 3, e1700694 (2017).

Zhang, S. et al. Wearable integrated self‐powered electroluminescence display device based on all‐in‐one MXene electrode for information encryption. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2307609 (2023).

Zhu, M. et al. Haptic-feedback smart glove as a creative human-machine interface (HMI) for virtual/augmented reality applications. Sci. Adv. 6, eaaz8693 (2020).

Chen, K. et al. Fabric‐based TENG woven with bio‐fabricated superhydrophobic bacterial cellulose fiber for energy harvesting and motion detection. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2304809 (2023).

Hu, S. et al. Triboelectric insoles with normal‐shear plantar stress perception. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2313458, (2024).

Zhao, L. et al. Triboelectric gait sensing analysis system for self‐powered IoT‐based human motion monitoring. InfoMat. 6, e12520, (2024).

Sun, Z. et al. Augmented tactile-perception and haptic-feedback rings as human-machine interfaces aiming for immersive interactions. Nat. Commun. 13, 5224 (2022).

Lin, M. et al. A high‐performance, sensitive, wearable multifunctional sensor based on rubber/CNT for human motion and skin temperature detection. Adv. Mater. 34, 2107309 (2022).

Yao, G. et al. Bioinspired triboelectric nanogenerators as self‐powered electronic skin for robotic tactile sensing. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 1907312 (2020).

Tao, K. et al. Deep-learning enabled active biomimetic multifunctional hydrogel electronic skin[J]. ACS Nano 17, 16160–16173 (2023).

Tang, Y. et al. Triboelectric touch‐free screen sensor for noncontact gesture recognizing. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 1907893 (2020).

Qin, K. et al. Magnetic array assisted triboelectric nanogenerator sensor for real-time gesture interaction. Nanomicro Lett. 13, 1–9 (2021).

Yang, J. et al. Self-powered tactile sensor for gesture recognition using deep learning algorithms. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14, 25629–25637 (2022).

Wen, F. et al. AI enabled sign language recognition and VR space bidirectional communication using triboelectric smart glove. Nat. Commun. 12, 5378 (2021).

Salauddin, M. et al. Highly electronegative V2CTx/silicone nanocomposite‐based serpentine triboelectric nanogenerator for wearable self‐powered sensors and sign language interpretation. Adv. Energy Mater. 13, 2203812 (2023).

Qu, X. et al. Artificial tactile perception smart finger for material identification based on triboelectric sensing. Sci. Adv. 8, eabq2521 (2022).

Wei, X. et al. An open‐environment tactile sensing system: toward simple and efficient material identification. Adv. Mater. 34, 2203073 (2022).

Sharma, S. et al. Stretchable and all-directional strain-insensitive electronic glove for robotic skins and human–machine interfacing. ACS Nano 17, 8355–8366 (2023).

Wandtner, B., Schömig, N. & Schmidt, G. Effects of non-driving related task modalities on takeover performance in highly automated driving. Hum. Factors 60, 870–881 (2018).

Xie, Z., Li, L. & Xu, X. Real-time driving distraction recognition through a wrist-mounted accelerometer. Hum. Factors 64, 1412–1428 (2022).

Dunn, N. J. et al. Investigating the impact of driving automation systems on distracted driving behaviors. Accid. Anal. Prev. 156, 106152 (2021).

Hungund, A. P. & Pradhan, A. K. Impact of non-driving related tasks while operating automated driving systems (ADS): a systematic review. Accid. Anal. Prev. 188, 107076 (2023).

Shi, E. & Bengler, K. Non-driving related tasks’ effects on takeover and manual driving behavior in a real driving setting: A differentiation approach based on task switching and modality shifting. Accid. Anal. Prev. 178, 106844 (2022).

Huynh-The, T. et al. Physical activity recognition with statistical-deep fusion model using multiple sensory data for smart health. IEEE Internet Things J. 8, 1533–1543 (2020).

Bianchi, V. et al. IoT wearable sensor and deep learning: an integrated approach for personalized human activity recognition in a smart home environment. IEEE Internet Things J. 6, 8553–8562 (2019).

Zhang, H. et al. Real‐time non‐driving behavior recognition using deep learning‐assisted triboelectric sensors in conditionally automated driving. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2210580 (2023).

Nielsen, M. A. Neural Networks and Deep Learning (Determination Press, 2015).

Xie, J., Sage, M. & Zhao, Y. F. Feature selection and feature learning in machine learning applications for gas turbines: a review. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 117, 105591 (2023).

Hamed, T., Dara, R. & Kremer, S. C. Network intrusion detection system based on recursive feature addition and bigram technique. Comput. Secur. 73, 137–155 (2018).

Zhou, F. et al. Using eye-tracking data to predict situation awareness in real time during takeover transitions in conditionally automated driving. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transport. Syst. 23, 2284–2295 (2021).

McDonald, A. D. et al. Toward computational simulations of behavior during automated driving takeovers: a review of the empirical and modeling literatures. Hum. Factors 61, 642–688 (2019).

Weaver, B. W. & DeLucia, P. R. A systematic review and meta-analysis of takeover performance during conditionally automated driving. Hum. Factors 64, 1227–1260 (2022).

Lu, G. et al. Measuring drivers’ takeover performance in varying levels of automation: considering the influence of cognitive secondary task. Transport. Res. F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 82, 96–110 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the Program of National Natural Science Foundation of China Grant No. 62373235, 61991415, Shanghai Science and Technology Committee Natural Science Program Grant No.23ZR1423700, China National Postdoctoral Program for Innovative Talents Grant No. BX20240199, and Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities of China Grant No. 2023JKF02ZK05.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.L., H.T., and H.Z. contribute equally to this work. X.L., H.T., and H.Z. conceived the idea, fabricated the device, conducted the experiment, collected and analyzed the data, constructed the deep learning model, rendered the figures, and wrote the manuscript. W.W., S.X., T.Y., and F.C. guided and supervised this work.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Tianyiyi He and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lu, X., Tan, H., Zhang, H. et al. Triboelectric sensor gloves for real-time behavior identification and takeover time adjustment in conditionally automated vehicles. Nat Commun 16, 1080 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56169-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56169-2