Abstract

The main obstacle to large scale quantum computing are the errors present in every physical qubit realization. Correcting these errors requires a large number of additional qubits. Two main avenues to reduce this overhead are (i) low-density parity check (LDPC) codes requiring very few additional qubits to correct errors (ii) cat qubits where bit-flip errors are exponentially suppressed by design. In this work, we combine both approaches to obtain an extremely low overhead architecture. Assuming a physical phase-flip error probability ϵ ≈ 0.1% per qubit and operation, one hundred logical qubits can be implemented on a 758 cat qubit chip, with a total logical error probability per cycle and per logical qubit ϵL ≤ 10−8. Our architecture also features two major advantages. First, the hardware implementation of the code can be realised with short-range qubit interactions in 2D and low-weight stabilizers, under constraints similar to those of the popular surface code architecture. Second, we demonstrate how to implement a fault-tolerant universal set of logical gates with an additional layer of routing cat qubits stacked on top of the LDPC layer, while maintaining the local connectivity. Furthermore, our architecture benefits from a high capacity of parallelization for these logical gates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The discovery of quantum algorithms capable of solving certain computational problems super-polynomially faster than their classical counterparts has ignited a race to develop quantum computers1,2. However, current quantum processors, constrained by quantum decoherence to error rates around 10−3 − 10−4 per qubit and per operation3,4,5, cannot yet solve practical problems that require 107 − 1011 quantum gates6,7,8.

The theory of fault-tolerant quantum computing9,10,11,12, in principle, offers a solution to this problem. The logical quantum information is encoded with a collection of physical quantum systems using error-correcting codes. Below their fault-tolerance threshold12,13, logical qubit errors can be arbitrarily suppressed by increasing the code distance d (the minimum number of errors not detected by the code). However, in practice, the implementation of error correction incurs a significant hardware overhead.

For instance, the surface code, despite its high threshold and experimental practicality, demands a significant qubit overhead for the required logical error rate of quantum algorithms6,14. This is explained by its relatively poor encoding rate. For a quantum code encoding k logical qubits in n physical qubits with distance d, the encoding rate is defined as the ratio of the number of logical qubits to physical qubits k/n. The encoding rate of the surface code is given by 1/d2. For the practical distances of interest falling within the range of 10−30, this leads to a 1% to 0.1% rate. Thus, between 100s and 1000s of physical qubits are needed per logical qubit.

One direction pursued to reduce this overhead is the use of quantum low-density parity-check (qLDPC) codes, which has been the focus of recent intensive research15, leading to the discovery of “good” qLDPC codes16,17,18 with a non-vanishing encoding rate and a distance growing linearly with the block size n. These theoretical advances have inspired the systematic search and the discovery of small qLDPC codes with higher encoding rates than the surface code19,20,21. However, implementing these superior codes incurs a higher technological cost than the surface code for a fundamental reason22. Indeed, Bravyi, Poulin and Terhal showed that the performance of a local quantum error correcting code on a 2D lattice is upper bounded by kd2 = O(n) (BPT bound)23. Because the surface code saturates this bound, improving upon it with a 2D architecture necessarily requires non-local i.e. long-range interactions in the processor. While this property is feasible for certain physical platforms like neutral atoms24,25, it is more challenging to realize with superconducting circuits, although the biplanarity property of some qLDPC codes may help20. Finally, the fault-tolerant construction of a universal set of logical gates, which can be reasonably parallelized on these qLDPC codes is still an active research problem26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36.

Another approach to reduce the footprint of the architecture is to optimize the synergy between the error-correcting code and its physical component noise structure37,38,39,40,41,42. In particular, dissipatively stabilized cat qubits43,44 stand out among bosonic qubits due to their remarkable property that the bit-flip error rate is exponentially suppressed with the average number of photons in the cat qubit, at the cost of a linear increase in the phase-flip error rate. This drastic scaling difference between these two types of errors leads to qubits with extremely biased noise of \(\eta \,\dot{=}\,{p}_{Z}/({p}_{Y}+{p}_{X})\,\gtrsim \,1{0}^{8}\) even for modest numbers of photons, as demonstrated experimentally with a 15 s bit-flip lifetime for a corresponding phase-flip lifetime of 4.9 × 10−7 s45,46,47,48. Such macroscopic bit-flip lifetimes pave the way to build logical qubits with applications-relevant logical error rates by correcting only phase-flip errors, thereby reducing the overhead of quantum error correction. The simplest way to achieve this is to concatenate cat qubits in a repetition code protecting against phase-flip errors, an architecture that has been the focus of many recent theoretical proposals and optimizations41,49,50,51,52,53 (Supplementary Discussion IA).

In this paper, we propose an LDPC architecture of cat qubits. This combines the improved encoding rate of LDPC codes and the hardware-efficient intrinsic protection of cat qubits. This leads to a fault-tolerant quantum computing architecture with extremely low qubit overhead, and a hardware complexity similar to the surface code architecture. The central idea we exploit is that it is possible to construct 2D codes outperforming the 1D repetition code without sacrificing locality. Indeed, the “classical version” of the BPT bound23 is \(k\sqrt{d}=O(n)\) for 2D codes, which repetition codes (k = 1, d = n) are far from saturating. Note that, similar to the assumptions leading to the BPT bound, 2D local means that the stabilizers of the code act locally on the qubits arranged in a 2D grid (here, at most next-nearest neighbour) which does not necessarily imply that the connectivity graph is planar. While some of the codes we propose do not have planar connectivity graphs, the locality property still makes it relatively easy to implement using a flip-chip technology (as discussed in Supplementary Discussion IV). Our numerical search for 2D local LDPC codes with favorable parameters allows us to identify codes with the desired distances ≈ 10 − 30 that exhibit up to 5.5 × higher encoding rates than the repetition code, at the cost of increasing the weight of stabilizers from two to four. Furthermore, we show how the lattice surgery schemes of the repetition code architecture51 can be adapted to these codes to perform a universal set of fault-tolerant logical gates without sacrificing locality. We provide in Table 1 a comparison of the footprint and the key technological assumptions of our architecture alongside some of the best alternatives to build a 100-logical qubit quantum processor with a logical error rate ϵL ≤ 10−8 using superconducting circuits. These numbers correspond to the entrance into the “fault-tolerant” regime where quantum hardware becomes able to solve useful computational problems that are beyond the reach of classical methods, such as open problems in quantum materials54, the simulation of the dynamics of a 2D Hubbard model with 10 × 10 lattice sites7 or the simulation of 3D spinful jellium55.

Results

High-rate local phase-flip codes

We turn our attention to the search for small phase-flip LDPC codes with higher encoding rates than repetition codes for relevant code distances. As cat qubits are protected against bit-flip errors, only Z-type errors need to be corrected. Thus we look for codes for which the stabilizer group is a subgroup of the Pauli group with X-type stabilizers exclusively and where codestates can be naturally expressed in the \(\left\vert \pm \right\rangle\) basis.

We impose the 2D local constraint and consider stabilizers limited by next-nearest neighbor interactions only. This is in contrast with previous approaches20,25 that required long-range interactions. We first consider codes where all the stabilizers are generated by horizontal and vertical translations of a single generator stabilizer on the 2D lattice, so that the “shape” of the stabilizer is unique (for instance,  is the repetition code X stabilizer shape and

is the repetition code X stabilizer shape and  corresponds to the X stabilizer shape of the surface code). The results are depicted in Fig. 1(a), where the best codes are shown. We evaluate the merit of the different codes using the value of kd/n, quantifying the overhead improvement over the repetition code, for which kd/n = 1. Therefore, the value of kd/n for other phase-flip codes can be interpreted as the overhead reduction factor of the number of physical qubits to implement a given number of logical qubits with a specific distance.

corresponds to the X stabilizer shape of the surface code). The results are depicted in Fig. 1(a), where the best codes are shown. We evaluate the merit of the different codes using the value of kd/n, quantifying the overhead improvement over the repetition code, for which kd/n = 1. Therefore, the value of kd/n for other phase-flip codes can be interpreted as the overhead reduction factor of the number of physical qubits to implement a given number of logical qubits with a specific distance.

a Each marker represents a single code, and the color indicates the stabilizer weight. The circular and triangular markers indicate codes with local stabilizers fitting within a 3 × 3 grid of data qubits, which are invariant under vertical and horizontal translations on the grid of qubits. By construction, the stabilizers have weight at most 9, and at most next-nearest neighbor physical extension. We systematically test all possible stabilizer shapes among the 512 possibilities {I, X}⊗9 but only the best codes are displayed. The triangles highlight the family of cellular automaton codes, which feature attractive properties for the quantum architecture (see main text). All codes are constructed on lattices of size H × L ≤ 17 × 17 with n = HL data qubits, with periodic boundary conditions on the lateral sides which allows us to avoid specifying the precise shape of the code lateral boundaries. However, this condition can be removed to retrieve local codes (Supplementary Discussion IIA). The codes identified by a cross have been found by allowing the shape of the (weight-4) stabilizers to differ at each row of the lattice. The 2D code performance upper bound is also indicated23. Markers with an outline indicate stabilizer shapes spanning three rows which tend to exhibit superior performance for almost all distances. b Performance of 2D local phase-flip codes encoding k = 22 logical qubits as a function of the code distance. The codes are constructed on lattices of size up to L = H = 34, with periodic boundary conditions on the lateral sides. To compare the performance of our local codes in an absolute sense, we represent, for a fixed number of logical qubits, the theoretical upper bound for the overhead reduction factor together with the best-known classical codes79 (thick blue curve, where the top part indicates the best possible code and the bottom part the best-known code). Quite remarkably, for the parameters k and d considered, our local codes are close to the best (potentially non-local) existing classical codes.

Unsurprisingly, codes with high stabilizer weights generally exhibit superior performance. Interestingly, many of the best codes we identified belong to the family of cellular automaton codes23,56,57,58,59,60 which are known to have a better asymptotic scaling than repetition codes23,59. These codes, identified by triangles in Fig. 1, are characterized by a “pointed” stabilizer shape, i.e. the stabilizer non-trivially acts on only one of the qubits in the top row of its support as illustrated in Fig. 2a, b. This property implies a systematic construction of the logical codewords using a cellular automaton rule corresponding to the stabilizer’s shape. The number of encoded logical qubits k can then be arbitrarily tuned by varying the width of the lattice.

Cellular automaton codes are a family of local codes characterized by “pointed''-shape stabilizers, acting on a single qubit of the top row of their support. Thus, for a stabilizer shape spanning m rows, the 2k codewords are uniquely determined by the \(\left\vert \pm \right\rangle\) states of the bottom (m−1) rows of qubits and therefore correspond to a code of dimension k = (m − 1)L. Indeed, an entire codeword can be constructed row by row by successive applications of the cellular automaton rule corresponding to the stabilizer, as depicted (yellow arrow) for (a) a (m = 2, L = 4) code encoding 4 logical qubits and (b) a (m = 3, L = 4) code encoding 8 logical qubits. Consequently, the codewords can be interpreted as the vertical evolution of a 1D cellular automaton, with time progressing upwards and the stabilizers dictating the evolution rule. In (c-d), we represent a ZL logical operator of minimal weight for the two codes corresponding to the stabilizer shapes in a, b, respectively. The corresponding XL logical operator corresponds to a single X on the physical qubit at the bottom row of the lattice in the ZL support. We numerically observe that, for a lattice with sufficient width (about twice its height) or when periodic boundary conditions are removed (Supplementary Discussion IIA), the codewords with the smallest Hamming weight, which determine the distance, are the ones with a single \(\left\vert -\right\rangle\) state in the bottom row for most cellular automaton codes. Note that any horizontal shift of this logical operator remains a valid logical operator, thus defining a basis of minimum-weight logical operators. The (m − 1)L logical qubit ZL supports of this basis consist of a single \(\left\vert -\right\rangle\) state in the m − 1 bottom rows and extend in a “fractal” manner to the rows above, justifying the occasional reference to cellular automaton codes as fractal codes59. Note that the code (d) has a smaller distance than the code (c) but this is compensated by a doubled encoding rate, such that the overall overhead reduction factor is larger for the same distance.

Cellular automaton codes have been known to achieve a good performance, due to the “fractal” nature of the support of logical operators, which yields large distances compactly23,59,60 as shown in Fig. 2c, d. A minimal-weight logical basis of the code can be formed by horizontally translating the logical operator. Increasing the height of the lattice increases the support of the logical operators, and thus the distance, maintaining a constant number of logical qubits as long as the width remains unchanged. Remarkably, for a small number of logical qubits and relevant distances, the codes we found are close to the best (potentially non-local) existing codes, see Fig. 1b.

We introduce two improvements over previously existing cellular automaton codes. First, by selecting a stabilizer shape extending over m = 3 rows instead of m = 2, the number of logical qubits is equal to twice the width of the lattice, doubling the rate of the code. For these codes, the distance increases more slowly with the height, as can be seen in Fig. 2d where the support of the logical operators ZL is smaller. However, as more logical qubits are encoded, the overall code parameters are improved as identified in Fig. 1 by markers with an outline for codes where m = 3. Second, we extended the search to cellular automaton codes for which the stabilizer shape in each row of the lattice is allowed to differ. We focused on weight-4 stabilizers, which we deem to be the best compromise between stabilizer weight and the overhead reduction factor kd/n based on the search results. We identified the optimal stabilizer shapes maximizing the cellular automaton codes performance. To assess the gain in performance due to these optimizations, these new codes are shown (marked by crosses) in Fig. 1. The optimization significantly improves the performance: the codes with weight-4 stabilizers of varying shapes achieve comparable performances as codes with a single stabilizer shape of weights 5 to 7. Their specific structure can be found in Table 2. In particular, the [136, 34, 22] code reduces the overhead by a factor kd/n = 5.5 for distance d = 22, nearly doubling the performance over the previously existing cellular automaton codes with only 4 physical qubits per logical qubits.

Numerical estimation of the logical error probability

We now quantify more precisely the logical error probability of the optimized codes which exhibit the most favorable overhead reduction factor kd/n. The total logical error probability is given by \({\epsilon }_{L}\approx {p}_{{X}_{L}}+{p}_{{Z}_{L}}\) (as \({p}_{{Y}_{L}}={p}_{{X}_{L}}{p}_{{Z}_{L}}\ll {p}_{{X}_{L}},{p}_{{Z}_{L}}\)), where \({p}_{{X}_{L}}\) and \({p}_{{Z}_{L}}\) are the probabilities of logical bit-flip and phase-flip errors per code cycle. To compare the different codes, the logical errors \({p}_{{X}_{L}}\) and \({p}_{{Z}_{L}}\) are normalized by the number of logical qubits encoded. Since phase-flip codes do not protect against bit-flip errors, we estimate the logical phase-flip and bit-flip probability separately. \({p}_{{X}_{L}}\) is simply given by Ncat qubits × pX/k, where Ncat qubits is the total number of cat qubits and pX is the physical bit-flip error probability per error correction cycle. We evaluate \({p}_{{Z}_{L}}\) with a Monte Carlo method and derive a phase-flip threshold. Note that overall this architecture does not have a conventional threshold, as the physical phase-flip rate of cat qubits increases linearly with the average photon number \(\bar{n}\), eventually surpassing the phase-flip threshold of the code. But in practice it enables us to reach sufficiently low logical error rates with a competitive overhead compared to other approaches (Supplementary Discussion IA).

We compare the optimized codes of Table 2 to the repetition code family under a cat qubit circuit-level error model, which includes errors at all locations in the circuit. The precise error models are obtained using master equation simulations of noisy operations on cat qubits41,50 parameterized by the relevant ratio κ1/κ2, where κ1 is the single-photon loss rate of cat qubits and κ2 is the two-photon stabilization rate (Supplementary Discussion IB).

We plot the logical phase-flip error probability as a function of physical error probability in Fig. 3. The phase-flip threshold of cellular automaton codes is approximately 3 times lower, fitting to the ansatz \({p}_{{Z}_{L}}=0.1{(1613{\kappa }_{1}/{\kappa }_{2})}^{0.94\lfloor \frac{d+1}{2}\rfloor }\) compared to \(0.07{(486{\kappa }_{1}/{\kappa }_{2})}^{0.94\lfloor \frac{d+1}{2}\rfloor }\) for the repetition code. We attribute this to the fact that the syndrome measurement circuit is deeper for these codes, as the weight-four stabilizers require four CNOT gates to be measured instead of two for the weight-two repetition code (Supplementary Discussion IIB). However, for a targeted logical error rate ϵL = 10−8, cellular automaton codes still provide a significant overhead advantage over repetition codes. Indeed, at κ1/κ2 = 10−4, we estimate the logical phase-flip error probability per cycle and normalized by the number of logical qubits at \({p}_{{Z}_{L}}=6.4\times 1{0}^{-10}\) with the [136, 34, 22] code. The simulations were performed with a number of photons \(\bar{n}=11\) so that the logical bit-flip probability is given by \({p}_{{X}_{L}}=1.8\times 1{0}^{-9}\).

The probability is normalized by the number of logical qubits, calculated after d error correction cycles (\({p}_{{Z}_{L}}^{{{{\rm{tot}}}}}\)) and plotted as a function of the physical error probability, under a cat qubit circuit-level error model. Repetition codes are identified by circles and optimized codes from Table 2 by crosses. The d rounds are decoded using the belief propagation + ordered statistics decoding (BP+OSD) decoder73,74. The decoder succeeds if the proposed correction successfully removes the errors, otherwise it introduces a logical error. The circuit is sampled until 100 logical errors are observed, and the probability of a logical phase-flip error after d rounds is estimated as \({p}_{{Z}_{L}}^{{{{\rm{tot}}}}}=1-{(1-100/N)}^{1/k}\) where N is the total number of samples (the standard deviations, not depicted in the figure, are approximately equal to \({p}_{{Z}_{L}}^{{{{\rm{tot}}}}}/10\), smaller than the marker size). The logical phase-flip error per round is then estimated as \({p}_{{Z}_{L}}\approx {p}_{{Z}_{L}}^{{{{\rm{tot}}}}}/d\). We observe that codes with identical distances have a similar scaling but the phase-flip threshold is lower for the cellular automaton codes. We attribute this effect to the depth of the weight-4 stabilizer measurement circuits compared to the weight-2 stabilizers of the repetition codes. The fit is used to extrapolate the logical error rate of the d = 22 code to κ1/κ2 = 10−4 (Supplementary Discussion IIB).

As the number of logical qubits can be arbitrarily tuned with cellular automaton codes, the [165 + 8ℓ, 34 + 2ℓ, 22] code family, the extended version of the [136, 34, 22] code without periodic boundary conditions (Supplementary Discussion IIA), can be used to encode 100 logical qubits in a [429, 100, 22] code, for a total number of 758 cat qubits including ancilla qubits compared to 2100 for the repetition code. The code is expected to achieve a total error probability ϵL = 2.5 × 10−9. Note that a lower value of κ1/κ2 would increase the overhead advantage on the repetition code. However, the number of physical data cat qubits per logical qubit of this code is 4.3 (for a code of distance 22), such that this code is already extremely efficient.

Fault-tolerant universal logical gate implementation

"Block” codes, where the coding blocks contain several logical qubits, allow for a compact encoding, but the price to pay is that it is more difficult to manipulate logical information. Indeed, unlike the case where only one logical qubit is encoded per block, here the supports of the logical operators corresponding to different logical qubits overlap, such that each physical qubit belong to the logical operator support of distinct logical qubits. Therefore, it is not straightforward to individually address logical qubits.

The initial proposals for “block” codes were based on teleportation61,62. In order to reduce the overhead of these protocols, more recent works propose to use state preparation and teleportation26,63 or, more efficiently, to adapt the lattice surgery techniques29,33 developed for the surface code64. Alternatively, code deformation methods can be used27,28.

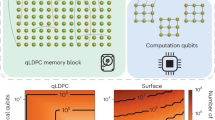

Here, we propose to implement a universal set of logical gates on our phase-flip LDPC codes with a two-layer architecture, which can be realized with existing flip-chip technologies (Supplementary Discussion IV). The lower layer is a “memory” layer that contains the logical qubits encoded in high-rate local phase-flip codes, and the upper layer is a “computing” layer that contains logical routing qubits and magic state factories encoded in repetition codes, as depicted in Fig. 4c. Each of the data qubits of the memory layer is connected to the corresponding data qubit of the computing layer, in order to implement physical CNOT gates. This construction only increases the connectivity of the logical data qubit of the memory layer by one while retaining locality. The ancillary logical qubits encoded in repetition codes are used to implement a universal set of logical gates on the qubits of the memory layer by adapting the schemes proposed for the repetition code architecture. We redirect the reader to the refs. 41,50,51 for a detailed description of the logical operations and here focus only on the differences due to the block code encoding. More precisely, the set of logical states \(\{{\left\vert+i\right\rangle }_{L},{\left\vert {\mbox{C}}Z\right\rangle }_{L},{\left\vert {{\mbox{CC}}}X\right\rangle }_{L}\}\) can be prepared using fault-tolerant logical measurements on repetition codes50. This set of states allows for a universal gate set when supplemented with the set of operations \(\{{{{{\mathcal{P}}}}}_{{\left\vert 0\right\rangle }_{L}},{{{{\mathcal{P}}}}}_{{\left\vert+\right\rangle }_{L}},{Z}_{L},{X}_{L},\,{{\mbox{C}}}\,{X}_{L},{{{{\mathcal{M}}}}}_{{Z}_{L}},{{{{\mathcal{M}}}}}_{{X}_{L}}\}\), some of which can be directly realized in the memory layer, as we now detail. We focus on cellular automaton codes with the stabilizer shape  as in Fig. 2a for simplicity but the schemes are general and can be realized for all of the codes of Fig. 1.

as in Fig. 2a for simplicity but the schemes are general and can be realized for all of the codes of Fig. 1.

Figure b presents the lattice surgery circuit used64. As depicted in Figure a, the implementation requires routing qubits encoded in the repetition code. First, a logical \({\left\vert 0\right\rangle }_{L}\) repetition code is prepared. A logical CNOT gate is performed between the control logical qubit and the logical \({\left\vert 0\right\rangle }_{L}\). This is followed by an MXX measurement between the logical \({\left\vert 0\right\rangle }_{L}\) and the target logical qubit. This process includes preparing a routing ancilla (dashed circle) in the \(\left\vert+\right\rangle\) state, performing two CNOTs with the logical \({\left\vert 0\right\rangle }_{L}\) and the logical \({X}_{L}^{t}\) of the target logical qubit, and finally measuring the ancilla. The result is the MXX measurement and the procedure is repeated d times to ensure fault-tolerance. Finally, the logical ancilla is measured in the Z basis and some Pauli corrections are applied depending on the MXX and MZ measurements. c Layout overview of the quantum processor with a bilayer architecture required for performing operations on 2D local phase-flip codes. CNOT gates are allowed between corresponding vertical qubits in the memory layer and the computing layer. Magic state factories are located on the side of the computing layer, and the states can be used to perform the corresponding gates in the memory layer through Clifford circuits via the computing layer. d Layout of a [165, 34, 22]⋆ cellular automaton code corresponding to the optimized code of Table 2 for H = 8 but without periodic boundary conditions. Flip chip technology enables connections between corresponding qubits in the memory layer and the computing layer. The weight-4 stabilizers of the code feature crossing cables but this can be circumvented by passing through the other plane. The trapezoidal shape enables to remove the periodic boundary conditions and ensures that the support of the ZL logical operators on the side (in red and yellow) achieve full distance in order to preserve the code parameters (Supplementary Discussion IIA). All data qubits and ancilla qubits are represented (except for the magic state factories) for a total of 296 qubits for the memory layer and 311 for the computing layer.

Pauli preparations and measurements can be performed on every logical qubit by leveraging stabilizer measurements65 or by utilizing ancilla qubits (Supplementary Discussion IIIA). A logical CNOT gate between two logical qubits of the memory layer can be directly implemented using the computing layer, as shown in Fig. 4a, with the lattice surgery scheme described in64, depicted in Fig. 4b. Note that this scheme can be extended to realize multiple-target controlled NOT gates \(\,{{\mbox{C}}}\,{X}_{L}^{k}\)51, or several CNOT gates sharing the same target in parallel. However, two CNOTs with overlapping control qubits and different target qubits cannot be realized simultaneously as the routing qubits used for one CNOT are unavailable for the other. As a consequence, a high level of parallelization is possible, but with some minor constraints. Finally, logical magic states are prepared in dedicated magic state factories in the computing layer as depicted in Fig. 4c and teleported to perform the operations required to complete the universal set of gates with minor adaptations of the techniques used for the intra-block CXL gate (Supplementary Discussion IIIB).

Discussion

The use of extremely biased-noise qubits concatenated in high-rate phase-flip LDPC codes opens a new path towards hardware-efficient quantum computing. The proposed architecture is local in 2D with low-weight stabilizers, constraints similar to the surface code. This contrasts with standard non-biased qubits which necessarily require technologically challenging long-range connectivity to exploit high-encoding rate quantum LDPC codes. A universal and fault-tolerant set of logical gates can be implemented using local physical operations by adapting lattice surgery schemes. An important assumption is that the bit-flip error rate is suppressed at the desired level by the cat qubits alone. This has already been demonstrated during idling and Z gates46,47,48, and recent promising experimental results demonstrated a bias-preserving CNOT gate66. Rapid progress in cat qubit engineering has allowed to achieve a ratio κ1/κ2 = 6.5 × 10−3 48 and we deem a value around κ1/κ2 = 10−4 may be achieved when the platform reaches its experimental maturity (see Supplementary Discussion IB for details about the hardware hypothesis). Furthermore, this assumption could be relaxed due to recent theoretical progress (Supplementary Discussion IC). The two layers of the architecture can be realized with a flip-chip technology67,68 (Supplementary Discussion IV) as shown in Fig. 4d. In order to quantify how the gains in memory reduce resources requirements for fault-tolerant quantum algorithms, we benchmark our architecture against the repetition cat code architecture which can be used to factorize RSA-2048 integers in 4 days using 350000 cat qubits51. We estimate that, under the same hardware assumptions (κ1/κ2 = 10−5), the improvements proposed in this paper would reduce this number to less than 100000 cat qubits, and 7 days of computation.

Methods

Architectures comparison

Comparing architectures that do not rely on the same types of qubit is a somewhat difficult task because one cannot directly use the same error models to make an apples-to-apples comparison. However, it remains an interesting exercise that sheds light on the importance of the assumptions made for each architecture, and allows for a better understanding of the significance of experimental progress for each physical platform. We first detail how the figures in Table 1 were obtained, before discussing several recent theoretical proposals to further optimise the performance of the cat qubit architecture.

Surface code

Assuming a circuit-level depolarizing noise where all of the operations in the syndrome measurements circuits are noisy, with identical infidelity ϵ, and using a minimum-weight perfect matching decoder, the logical error probability per code cycle ϵL is well approximated by69,70

For ϵ = 10−3, a logical error rate ϵL = 10−8 is achieved for a code distance d = 13. With these numbers, one can encode NL = 100 logical qubits with N = NL(2d2 − 1) = 33,700 physical qubits (including ancilla qubits).

Small qLDPC code

We focus for this example on the [[144, 12, 12]] qLDPC code introduced in ref. 20. This code is a quasi-cyclic code of CSS type with stabilizer operators of weight 6. The Tanner graph of this code has thickness two, which implies from a technological point of view that the code can be implemented using two planar layers of couplers that do not intersect (see ref. 20 for a detailed discussion). Under a circuit-level depolarizing noise of strength ϵ and using a BP+OSD decoder, the logical error probability per code cycle and normalized by the number of logical qubits ϵL is well approximated by20

where c0 = 18.04, c1 = 1337, c2 = − 96007. Thus, ϵ = 10−3 corresponds to a logical error rate ϵL = 2 × 10−8 and the total number of physical qubits required to implement NL = 100 logical qubits is N = 2nNL/12 = 2400.

Cat qubits and repetition codes

Assuming all of the operations of the repetition code (ancilla cat state preparation, CNOT gates, and ancilla measurement, see41,44 for a detailed review) are realized in time T = 1/κ2, where κ2 is the two-photon dissipation rate, and assuming that the only error channel is single-photon loss at a rate κ1, the logical error probability per code cycle ϵL is well-approximated by51

where d is the repetition code distance (against phase-flip) and \(\bar{n}\) is the mean photon number of the cat, playing the role of the “distance” against bit-flips. Note that here \({\epsilon }_{L}={\epsilon }_{L}^{Z}+{\epsilon }_{L}^{X}\) corresponds to the total logical error rate, while in the two previous examples ϵL is the logical error probability of either logical bit-flips or phase-flips (identical). Assuming a ratio κ1/κ2 = 10−4, one achieves a logical error rate ϵL = 2.8 × 10−9 + 2.7 × 10−9 = 5.5 × 10−9 using code distances \((\bar{n},d)=(11,11)\), which corresponds to a total number of cat qubits N = (2d − 1)NL = 2, 100. Note that these assumptions translate (see Supplementary Table 1) into state preparation and measurement infidelities of ϵSPAM = 1.1 × 10−3, CNOT gate infidelity of ϵCNOT = 1.6 × 10−2 and idling errors of ϵidling = 1.1 × 10−3, that is, all operations are noisier than for a depolarizing error model with strength ϵ = 10−3.

Efficient computation of the code distance

In the exhaustive numerical search for the best phase-flip local LDPC codes, we considered all 511 possible stabilizer shapes fitting withing a 3 × 3 square of data qubits. We also varied the dimension of the 2D grid up to H × L ≤ 17 × 17. Each possible stabilizer shape yields a code for which we calculate the dimension k and distance d. Since these codes are linear, one can put their parity-check matrix (defined by the stabilizers) into normal form to obtain a basis of k codewords of the codespace. The distance of the code may then be computed exactly by constructing the 2k codewords, as the code distance corresponds to the minimal non-zero Hamming weight of the codewords.

Computing the exact distance of a classical code is known to be an NP-hard problem71. In this work, we relied on two approaches: the first one simply consists in enumerating all of the 2k − 1 nonzero codewords and computing the minimum Hamming weight. This method becomes very costly for k ≥ 34, even if cellular automaton codes have the nice advantage that the systematic construction of the codewords increases the computation speed.

The second method is to use a SAT solver. SAT solvers have been optimized to solve the boolean satisfiability problem, i.e. finding possible values for boolean variables to satisfy a set of constraints. We define these variables and constraints with the generator matrix G of the code, which gives a basis of k codewords, where any codeword c can be written as \(c=\mathop{\sum }_{i=1}^{k}{b}_{i}{G}_{i}\). Gi is the codeword corresponding the i-th row of the matrix G and bi are the boolean variables of our problem.

Given that the goal is to find the minimal Hamming weight of a codeword, we impose the following constraints for a given tested distance \({d}^{{\prime} }\): at least one bi must be non-zero and the \(\mathop{\sum }_{i=1}^{k}{b}_{i}{G}_{i}\) must be at most \({d}^{{\prime} }\). If the SAT solver finds a combination of bi which is a solution, then the distance of the code \(d\le {d}^{{\prime} }\), otherwise \(d > {d}^{{\prime} }\). The minimal value \({d}^{{\prime} }\) for which the problem is satisfied is the code distance d, found using a dichotomic search over \({d}^{{\prime} }\).

Using this method and the z3 SAT solver72, we were able to compute the exact distance of some codes up to k = 62. This is possible because the SAT solver does not go through the entire code space but explores the space of possibilities given the constraints in a more subtle way. We numerically observed that the SAT solver is not always faster than the brute force method, however, we did not find any simple criteria to predict which method is most efficient for a given code, as SAT solvers are complex algorithms.

Efficient code optimisation

In this section, we detail the procedure to find the optimal stabilizer shapes of cellular automaton codes. The search space consists only of codes with “pointed” stabilizer shapes so that any codeword is uniquely determined by its values at the bottom rows of the lattice.

Varying the stabilizer shapes of the code will not change the number of encoded logical qubits for a given width and height but can increase the distance of the code. This can be understood from Fig. 2c-d, showing a codeword of minimal Hamming weight, which consists of a single \(\left\vert -\right\rangle\) state in the bottom rows. The Hamming weight, i.e. the number of \(\left\vert -\right\rangle\) states, in this codeword will never exceed the number of qubits within the triangle area. But by changing the stabilizer shapes (i.e. the rules of the cellular automaton), we may increase the number of \(\left\vert -\right\rangle\) states.

We further restrict the search space to a unique stabilizer shape in each row of the lattice. This guarantees that the search remains tractable, while we empirically found that, for smaller instances, removing this constraint does not bring a significant advantage. Brute-forcing the problem becomes quickly intractable, so we used a SAT solver for the largest instances72.

We first fix the width and height of the lattice. The boolean variables correspond to the allowed stabilizer shapes (with several boolean variables per shape) and 2k constraints impose that all codewords have a Hamming weight larger than a tested distance \({d}^{{\prime} }\). If the solver is able to find stabilizer shapes, which verify all the constraints, it corresponds to a code with distance \({d}^{{\prime} }\ge d\). By progressively increasing \({d}^{{\prime} }\), we are able to find the maximum distance attainable for a cellular automaton code of a given height.

The constraints (i.e. the Hamming weight of the codewords) need to be expressed with boolean variables. Thanks to the structure of cellular automaton codes, this task just consists of applying the cellular automaton rules from a given bit-string in the bottom rows conditionally on the boolean variables. This method gives relatively simple expressions compared to a general code.

BP+OSD decoding

In this section, we briefly present the BP+OSD decoder and the parameters we chose. This decoder was first introduced in73 and a more efficient variant of the ordered statistics decoding (OSD) was proposed in74. The first step of the decoding process is belief propagation where an error probability is assigned to every qubit knowing the syndrome. This marginal probability is calculated iteratively until a maximum number of steps. If the proposed correction is in agreement with the given syndrome, the decoding process stops there. Otherwise, the OSD routine is called. The qubits for which the value is the most reliable at the end of BP are fixed, and a greedy search is performed on the other qubits for the codeword with the smallest Hamming weight and which is in agreement with the syndrome. The OSD order designates the number of qubits involved in this greedy search and the number of combinations tested increases exponentially with the order.

We chose the “min-sum” variant of belief propagation and we have observed no significant difference between the various methods ("product-sum”,"min-sum”) in the case of the cellular automaton code decoding process. Additionally, the decoding is slightly better when the scaling factor is chosen at 0.625 as proposed in73 when the “min-sum” method is used. Finally, the number of iterations does not appear to play a significant role either (even when set to 4, which corresponds to the cycle length in the Tanner graph of the code) as shown in Fig. 5. The numerical results reported in our figures are obtained with a maximum number of iterations of 10,000.

The lattice size is set as H = 3 and L = 10 which corresponds to a code of distance 7. The circuit-level noise model is considered and p designates the physical error rate on every gate and idle location in the circuit. The maximum number of iterations of the belief propagation varies showing that this parameter does not play a significant role in the decoding process. The min-sum method is used and the scaling factor is set to 0.625.

Regarding the OSD routine, increasing the OSD order increases the performance of the decoder but at an exponential cost in time. We confirm, as that was stated in74, that the “combination sweep” method surpasses the “exhaustive method” for an equivalent number of configurations tested. We set the OSD order to 60, which gives a number of configurations to search through of 1770. The question of real-time decoding and a possibly faster or more efficient decoder for these very structured codes remains an open question.

Factoring 2048-bit RSA integers

In order to estimate the total number of cat qubits required to factorize 2048-bit RSA integers, we rely on the implementation of Shor’s algorithm described in75 and adapted to the cat qubit architectures in51, as the set of logical gates is identical. In this previous work, logical gates are not parallelized, in order to minimize as much as possible the space overhead (number of logical qubits) at the cost of increasing the time overhead (the runtime of the algorithm). We follow the same implementation, such that the fact that some logical CNOT gates might not be executed in parallel on our codes is not an issue here.

In order to provide a fair comparison of the reduction in overhead, we use the exact same hardware assumptions and error models as in51. We therefore assume a ratio κ1/κ2 = 10−5, and an average photon number \(\bar{n}=21\), in order to reach the extremely low logical error probability ϵL ≈ 10−17 per logical qubit and per code cycle required to run Shor’s algorithm.

Replacing the distance d = 15 repetition codes by the dense [24885, 6214, 22] code of the [165 + 8ℓ, 34 + 2ℓ, 22] family in the memory block, the total number of cat qubits in the architecture decreases from 349133 cat qubits51 to 95941 cat qubits (code available here76). The computation time increases from 4 to 7 days, as a consequence of the weight-4 stabilizers (instead of weight-2) that increases the error correction cycle time from Tcycle = 500 ns to Tcycle = 900 ns.

Data availability

The data used in this study are available here77.

References

Simon, D. R. On the power of quantum computation. SIAM J. Comput. 26, 1474–1483 (1997).

Shor, P. W. Polynomial-time algorithms for prime factorization and discrete logarithms on a quantum computer. SIAM J. Comput. 26, 1484–1509 (1997).

Quantinuum. A race-track trapped-ion quantum processor. Phys. Rev. X 13, 041052 (2023).

Google Quantum AI. Suppressing quantum errors by scaling a surface code logical qubit. Nature 614, 676–681 (2023).

Kim, Y. et al. Evidence for the utility of quantum computing before fault tolerance. Nature 618, 500–505 (2023).

Beverland, M. E. et al. Assessing requirements to scale to practical quantum advantage, URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2211.07629 (2022).

Daley, A. J. et al. Practical quantum advantage in quantum simulation. Nature 607, 667–676 (2022).

Dalzell, A. M. et al. Quantum algorithms: A survey of applications and end-to-end complexities, URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2310.03011 (2023).

Shor, P. W. Scheme for reducing decoherence in quantum computer memory. Phys. Rev. A 52, R2493–R2496 (1995).

Shor, P. W. Fault-tolerant quantum computation. FOCS ’96, page 56, USA, IEEE Computer Society. (1996).

Steane, A. Multiple-particle interference and quantum error correction. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A: Math., Phys. Eng. Sci. 452, 2551–2577 (1996).

Knill, E., Laflamme, R. & Zurek, W. H. Resilient quantum computation. Science 279, 342–345 (1998).

Kitaev, A. Y. Fault-tolerant quantum computation by anyons. Ann. Phys. 303, 2–30 (2003).

Gidney, C. & Ekerå, M. How to factor 2048 bit rsa integers in 8 hours using 20 million noisy qubits. Quantum 5, 433 (2021).

Breuckmann, N. P. & Eberhardt, JensNiklas Quantum low-density parity-check codes. PRX Quantum 2, 040101 (2021).

Panteleev, P. & Kalachev, G. Asymptotically good quantum and locally testable classical LDPC codes. In Proceedings of the 54th Annual ACM SIGACT Symposium on Theory of Computing, pages 375–388, (2022).

Leverrier, A. & Zémor, G. Quantum Tanner codes. In 2022 IEEE 63rd Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science (FOCS), pages 872–883, https://doi.org/10.1109/FOCS54457.2022.00117 (2022).

Dinur, I., Hsieh, M.-H., Lin, T.-C. & Vidick, T. Good Quantum LDPC Codes with Linear Time Decoders. In Proceedings of the 55th Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing, STOC 2023, page 905-918, New York, NY, USA, Association for Computing Machinery. ISBN 9781450399135. https://doi.org/10.1145/3564246.3585101 (2023).

Higgott, O. & Breuckmann, N. P. Subsystem codes with high thresholds by gauge fixing and reduced qubit overhead. Phys. Rev. X 11, 031039 (2021).

Bravyi, S., Cross, A. W., Gambetta, J. M. et al. High-threshold and low-overhead fault-tolerant quantum memory. Nature 627, 778–782 (2024).

Higgott, O. & Breuckmann, N. P. Constructions and performance of hyperbolic and semi-hyperbolic floquet codes. PRX Quantum 5, 040327. (2024)

Baspin, Nouédyn & Krishna, A. Connectivity constrains quantum codes. Quantum 6, 711 (2022).

Bravyi, S., Poulin, D. & Terhal, B. Tradeoffs for reliable quantum information storage in 2d systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 050503 (2010).

Bluvstein, D. et al. Logical quantum processor based on reconfigurable atom arrays. Nature, pages 1–3, (2023).

Xu, Q. et al. Constant-overhead fault-tolerant quantum computation with reconfigurable atom arrays, URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2308.08648 (2023).

Gottesman, D. Fault-tolerant quantum computation with constant overhead. Quantum Info. Comput. 14, 1338 (2013).

Breuckmann, N. P., Vuillot, C., Campbell, E., Krishna, A. & Terhal, B. M. Hyperbolic and semi-hyperbolic surface codes for quantum storage. Quantum Sci. Technol. 2, 035007 (2017).

Krishna, A. & Poulin, D. Fault-tolerant gates on hypergraph product codes. Phys. Rev. X 11, 011023 (2021).

Cohen, L. Z., Kim, I. H., Bartlett, S. D. & Brown, B. J. Low-overhead fault-tolerant quantum computing using long-range connectivity. Sci. Adv. 8, eabn1717 (2022).

Jochym-O’Connor, T. Fault-tolerant gates via homological product codes. Quantum 3, 120 (2019).

Quintavalle, A. O., Webster, P. & Vasmer, M. Partitioning qubits in hypergraph product codes to implement logical gates. Quantum 7, 1153 (2023).

Breuckmann, N. P. & Burton, S. Fold-transversal clifford gates for quantum codes. Quantum 8, 1372 (2024).

Cowtan, A. & Burton, S. Css code surgery as a universal construction, URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2301.13738 (2023).

Zhu, G., Sikander, S., Portnoy, E., Cross, A. W. & Brown, B. J. Non-Clifford and parallelizable fault-tolerant logical gates on constant and almost-constant rate homological quantum LDPC codes via higher symmetries. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.16982, (2023).

Barkeshli, M., Hsin, P.-S. & Kobayashi, R. Higher-group symmetry of (3+ 1) d fermionic \({{\mathbb{Z}}}_{2}\) gauge theory: logical ccz, cs, and t gates from higher symmetry. SciPost Phys. 16, 122 (2024)

Lavasani, A., Zhu, G. & Barkeshli, M. Universal logical gates with constant overhead: instantaneous dehn twists for hyperbolic quantum codes. Quantum 3, 180 (2019).

Fukui, K., Tomita, A., Okamoto, A. & Fujii, K. High-Threshold Fault-Tolerant Quantum Computation with Analog Quantum Error Correction. Phys. Rev. X 8, 021054 (2018).

Vuillot, C., Asasi, H., Wang, Y., Pryadko, L. P. & Terhal, B. M. Quantum error correction with the toric Gottesman-Kitaev-Preskill code. Phys. Rev. A 99, 032344 (2019).

Noh, K. & Chamberland, C. Fault-tolerant bosonic quantum error correction with the surface–gottesman-kitaev-preskill code. Phys. Rev. A 101, 012316 (2020).

Joshi, A., Noh, K. & Gao, Y. Y. Quantum information processing with bosonic qubits in circuit qed. Quantum Sci. Technol. 6, 033001 (2021).

Guillaud, J. érémie & Mirrahimi, M. Repetition cat qubits for fault-tolerant quantum computation. Phys. Rev. X 9, 041053 (2019).

Kubica, A., Haim, A., Vaknin, Y., Brandao, F. & Retzker, A. Erasure qubits: Overcoming the t1 limit in superconducting circuits, (2022).

Leghtas, Z. et al. Confining the state of light to a quantum manifold by engineered two-photon loss. Science 347, 853–857 (2015).

Mirrahimi, M. et al. Dynamically protected cat-qubits: a new paradigm for universal quantum computation. N. J. Phys. 16, 045014 (2014).

Lescanne, Raphaël et al. Exponential suppression of bit-flips in a qubit encoded in an oscillator. Nat. Phys. 16, 509–513 (2020).

Berdou, C. et al. One hundred second bit-flip time in a two-photon dissipative oscillator. PRX Quantum 4, 020350 (2023).

Réglade, U. et al. Quantum control of a cat-qubit with bit-flip times exceeding ten seconds. Nature 629, 778–783 (2024)

Marquet, A. et al. Autoparametric resonance extending the bit-flip time of a cat qubit up to 0.3 s. Phys. Rev. X 14, 021019 (2024)

Guillaud, J. érémie & Mirrahimi, M. Error rates and resource overheads of repetition cat qubits. Phys. Rev. A 103, 042413 (2021).

Chamberland, C. et al. Building a fault-tolerant quantum computer using concatenated cat codes. PRX Quantum 3, 010329 (2022).

Gouzien, Élie, Ruiz, D., Le Régent, Francois-Marie, Guillaud, J. érémie & Sangouard, N. Performance analysis of a repetition cat code architecture: Computing 256-bit elliptic curve logarithm in 9 hours with 126133 cat qubits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 040602 (2023).

Xu, Q. et al. Autonomous quantum error correction and fault-tolerant quantum computation with squeezed cat qubits. npj Quantum Inf. 9, 78 (2023).

Régent, Francois-MarieLe, Berdou, C., Leghtas, Z., Guillaud, J. érémie & Mirrahimi, M. High-performance repetition cat code using fast noisy operations. Quantum 7, 1198 (2023).

Bauer, B., Wecker, D., Millis, A. J., Hastings, M. B. & Troyer, M. Hybrid quantum-classical approach to correlated materials. Phys. Rev. X 6, 031045 (2016).

Babbush, R. et al. Encoding electronic spectra in quantum circuits with linear t complexity. Phys. Rev. X 8, 041015 (2018).

Newman, M. E. J. & Moore, C. Glassy dynamics and aging in an exactly solvable spin model. Phys. Rev. E 60, 5068 (1999).

Chowdhury, DipanwitaRoy, Basu, S., Gupta, IdranilSen & Chaudhuri, ParimalPal Design of caecc-cellular automata based error correcting code. IEEE Trans. Comput. 43, 759–764 (1994).

San Miguel, J. F., Williamson, D. J. & Brown, B. J. A cellular automaton decoder for a noise-bias tailored color code. Quantum 7, 940 (2023).

Yoshida, B. Information storage capacity of discrete spin systems. Ann. Phys. 338, 134–166 (2013).

Nixon, G. M. & Brown, B. J. Correcting spanning errors with a fractal code. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 67, 4504–4516 (2021).

Gottesman, D. Theory of fault-tolerant quantum computation. Phys. Rev. A 57, 127 (1998).

Steane, A. M. Efficient fault-tolerant quantum computing. Nature 399, 124–126 (1999).

Steane, A. M. & Ibinson, B. Fault-tolerant logical gate networks for calderbank-shor-steane codes. Phys. Rev. A 72, 052335 (2005).

Horsman, C., Fowler, A. G., Devitt, S. & Meter, R. V. Surface code quantum computing by lattice surgery. N. J. Phys. 14, 123011 (2012).

Fowler, A. G., Mariantoni, M., Martinis, J. M. & Cleland, A. N. Surface codes: Towards practical large-scale quantum computation. Phys. Rev. A 86, 032324 (2012).

Jezouin, S. Dissipative cat qubits for quantum computing. Bulletin of the American Physical Society, (2024).

Putterman, H. et al. Hardware-efficient quantum error correction using concatenated bosonic qubits. arXiv preprint arXiv:2409.13025, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2409.13025 (2024).

Putterman, H. et al. Preserving phase coherence and linearity in cat qubits with exponential bit-flip suppression. arXiv preprint arXiv:2409.17556, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2409.17556 (2024).

Fowler, A. G., Devitt, S. J. & Jones, C. Surface code implementation of block code state distillation. Sci. Rep. 3, 1939 (2013).

Fowler, A. G. & Gidney, C. Low overhead quantum computation using lattice surgery, URL https://arxiv.org/abs/1808.06709 (2018).

Vardy, A. The intractability of computing the minimum distance of a code. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 43, 1757–1766 (1997).

Bjorner, N. et al. Z3 theorem prover. https://github.com/Z3Prover/z3.

Panteleev, P. & Kalachev, G. Degenerate quantum LDPC codes with good finite length performance. Quantum 5, 585 (2021).

Roffe, J., White, D. R., Burton, S. & Campbell, E. Decoding across the quantum low-density parity-check code landscape. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 043423 (2020).

Gouzien, Élie & Sangouard, N. Factoring 2048-bit RSA integers in 177 days with 13436 qubits and a multimode memory. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 140503 (2021).

Code is available at https://github.com/ElieGouzien/elliptic_log_cat, Gouzien, É. version 2.0, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10523899 (2023).

Code is available at https://github.com/DiegoRuiz-Git/LDPCat, Ruiz, D. version 1.0, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14717917 (2024)

McEwen, M., Bacon, D. & Gidney, C. Relaxing hardware requirements for surface code circuits using time-dynamics. Quantum 7, 1172 (2023).

Grassl, M. Bounds on the minimum distance of linear codes and quantum codes. Online available at http://www.codetables.de, (2007).

Acknowledgements

D.R. and J.G. would like to thank Paul Magnard for discussions about the feasibility of our proposal and for helping with the Figures. All authors thank Barbara Terhal, Benjamin Brown and Theodore Yoder for their comments on a previous version of the manuscript, and Élie Gouzien for computing the resources needed to factor a 2048-RSA integer and for helping with the use of SAT solvers. We acknowledge funding from the Plan France 2030 through the project ANR-22-PETQ-0006. M.M. thanks funding from QuantERA grant QuCOS, by ANR 19-QUAN-0006-04.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.M., J.G., A.L. and C.V. supervised the project. D.R. performed numerical simulations, data analysis and visualization. All authors contributed to improve the scheme. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Authors affiliated with Alice & Bob have financial interest in the company. M.M is shareholder of A&B. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ruiz, D., Guillaud, J., Leverrier, A. et al. LDPC-cat codes for low-overhead quantum computing in 2D. Nat Commun 16, 1040 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56298-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56298-8

This article is cited by

-

Opportunities in full-stack design of low-overhead fault-tolerant quantum computation

Nature Computational Science (2025)

-

Hardware-efficient quantum error correction via concatenated bosonic qubits

Nature (2025)