Abstract

The incorporation of thermal dynamics alongside conventional optoelectronic principles holds immense promise for advancing technology. Here, we introduce a GaON/GaN heterostructure-nanowire ultraviolet electrochemical cell of observing a photothermoelectric bipolar impulse characteristic. By leveraging the distinct thermoelectric properties of GaON/GaN, rapid generation of hot carriers establishes bidirectional instantaneous gradients in concentration and temperature within the nanoscale heterostructure via light on/off modulation. The thermoelectromotive force induced by these gradients, combined with the type-II heterojunction band structure, facilitates carrier transport, resulting in transient bidirectional photothermal currents. The device achieves exceptional responsivity (17.1 mA/W) and remarkably fast speed (8.8 ms) at 0 V, surpassing existing semiconductor electrochemical cells. This bipolar ultraviolet impulse detection mode harnesses light-induced heat for electricity generation, enabling innovative bidirectional encryption communication capabilities. Anticipated applications encompass future sensing, switchable light imaging, and energy conversion systems, thereby laying a foundation for diverse optoelectronic technological advancements.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The photothermoelectric (PTE) effect represents a crucial pathway for directly converting light energy into electrical energy1,2. When light irradiates thermoelectric materials non-uniformly, the photothermal effect induces localized temperature changing and creates a temperature gradient. This gradient causes photogenerated carriers to redistribute towards both colder and the hotter ends, establishing a potential difference along the gradient and facilitating thermoelectric conversion. Leveraging interaction between photothermal and thermoelectric processes, the PTE effect holds promise for applications in high-efficiency photoelectric energy harvesting and high-performance photoelectric detection3,4. As semiconductor devices shrink to nanometer scales, nanowire (NW) materials have garnered significant attention in nanophotonics and nanoelectronics5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12. The larger surface area of NWs provides more active sites for reactions in electrochemical cell, facilitating a greater number of reactants to interact with the electrode surface, which in turn enhances the reaction rate. Additionally, the increased surface area reduces the resistance to ion diffusion in the electrolyte, improving the response time of photoelectrochemical (PEC) devices. III-V group compound semiconductor NWs, in particular, exhibit unique physical and chemical properties alongside excellent photoelectric characteristic such as large specific surface area, lattice anisotropy, tunable size, high crystallinity, and controllable optical and electrical properties13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26. The thermoelectric response of NWs structures is highly sensitive to surface conditions, making them invaluable for applications in PEC detection.

In PEC cell, photogenerated carriers migrate to the semiconductor/electrolyte interface where they catalyze chemical reactions at active sites, enabling photoelectric conversion27,28. Enhancing these transport processes can significantly improve detection performance. Nanowires offer a large specific surface area that enhances light absorption efficiency. Furthermore, integrating heterojunction energy band engineering enhances separation and transport of photogenerated carriers. Meanwhile, the asymmetric crystal structure of materials like wurtzite gallium nitride (GaN) NWs induces an instantaneous temperature gradient under ultraviolet (UV) light, creating a thermoelectric potential along the NWs29. Nevertheless, the transient response characteristics of UV-induced thermoelectric phenomena have been overlooked for an extended period. Exploring these phenomena could unveil applications in optical detection.

In this study, we develop a rapid-response UV electrochemical cell by constructing p-type GaN NWs arrays on silicon (Si) and integrating a GaON/GaN heterostructure interface through oxidative reconstruction. This device demonstrates distinctive PTE bipolar impulse detection characteristics. GaON serves as both a protective layer for GaN NWs and as part of a type-II GaON/GaN heterojunction that modulates carrier transport dynamics, thereby enhancing carrier separation and extraction efficiency. The GaON/GaN heterostructure NWs exhibit remarkable PTE effects under UV stimulation, showcasing rapid UV detection and high responsivity capabilities. The light-induced thermoelectric bipolar impulse generates at the moments of light on/off transitions dramatically enhanced the UV response speed of devices. Without external bias, the response/recovery time of the GaON/GaN electrochemical cell is reduced to 23.5% and 9.3%, respectively, compared to pristine GaN devices. Under weak UV light (0.2 mW/cm2), the devices exhibit a notable 1900% increase in responsivity and a 266% improvement in specific detectivity. This enhancement in photoresponse characteristics due to the PTE effect is thoroughly expounded. Ultimately, the development of this fast-response UV electrochemical cell, based on the PTE bipolar impulse detection of GaON/GaN NWs, lays the foundation for optical communication systems with inverse encrypted communication capabilities. These advancements are poised to provide the possibility for applications in future UV photodetection in extreme environments.

Results

Morphology and structure characterization

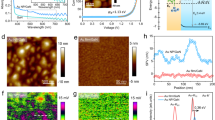

Epitaxial growth of GaN NWs on highly doped n-type Si substrates is achieved using molecular beam epitaxy (MBE), with magnesium (Mg) serving as an acceptor for effective p-type doping of GaN. Figure 1a depicts a scanning electron microscope (SEM) cross-section at a 30° tilt angle, clearly showing GaON/GaN NWs ranging in height from 200 nm to 300 nm. The schematic on the right illustrates a single NW, highlighting GaON/GaN heterojunction NWs on n-type Si. These NW arrays, uniformly distributed and with diameters of approximately 100–200 nm (Supplementary Fig. 1–4), are vertically aligned on the Si substrate. Following treatment with oxygen plasma and high-temperature annealing in a nitrogen environment, GaON protective layer surrounds the GaN NWs, resulting in core-shell GaON/GaN heterojunction NWs. The oxygen plasma treatment enhances oxygen penetration into the GaN NW surfaces, while subsequent high-temperature annealing induces recrystallization, repairing surface damage caused by plasma bombardment. Transmission electron microscope (TEM) images in Fig. 1b confirm the successful deposition of approximately 25 nm thick GaON on GaN NWs. Photoluminescence (PL) spectrums shown in Fig. 1c reveal the narrow full width at half maximum (FWHM) of both GaN and GaON/GaN materials, indicating excellent crystal quality. Although the introduction of GaON does not significantly shift the PL emission peak position following due to the dominant influence of the GaN layer, the intensity of PL emission from the GaON/GaN material decreases after oxidation reconstruction. This reduction suggests a wider band gap under identical excitation conditions, resulting in fewer carriers transitions to the conduction band (CB). When the GaN NWs are immersed in a 0.5 M sulfuric acid (H2SO4) solution, photogenerated holes migrate to the top interface to participate in the oxygen evolution reactions (OER), while photogenerated electrons move in the opposite direction as shown in Fig. 1d. According to the energy band diagram shown in Supplementary Fig. 5, the reason for the positive photocurrent of GaN NWs devices is analyzed. However, in the case of GaON/GaN heterojunctions, a distinct bipolar impulse phenomenon occurs.

a 30° tilt angle scanning electron microscope (SEM) images of GaON/GaN NWs on Si. The red frame shows the core-shell structure diagram of a single GaON/GaN heterojunction NW. The yellow frame marks the region of transmission electron microscope (TEM) testing. b TEM images of the top region for single GaON/GaN NW on Si with a white dotted wire frame encircling the region of the GaON layer at the top of the NW. c Photoluminescence (PL) spectrum at room temperature of GaN and GaON/GaN material. d The charge transport process and chemical reaction diagram of GaN and GaON/GaN NWs under illumination. The bending arrows denote the process of oxygen evolution reactions (OER). e The X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) spectra of the pristine GaN and the GaON material obtained after oxidation reconstruction. The valence band (VB) offset of GaON/GaN heterojunction is determined by the VB spectrum and the peak position of N 1 s. The black dotted line framed the position of the Ga LMM Auger spectrum. f O 1 s and g N 1 s core level spectra, N energy loss peak spectra of GaON material. h The energy band offset of GaON/GaN interface is described. CBM and VBM represent conduction band minimum and valence band maximum, respectively.

To accurately determine the energy band distribution of GaON/GaN heterojunction, we measured the X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) valence band (VB) spectrum, N 1 s core level spectrum (Fig. 1e) and full spectrum (Supplementary Fig. 6) of GaN and GaON materials. Using the binding energy of N 1 s as a reference, we observed VB difference of 0.24 eV between GaON and GaN. The flat VB edge of GaON suggests it is a homogeneous compound rather than a mere mixture of compounds30. Figures 1f and 1g show the XPS fine spectra of N 1 s, N energy loss peak and O 1 s core level spectra of GaON material. The N energy loss peak arises from energy loss and increased binding energy during the photoelectron escape process. Utilizing the formula I = n×S, where I represents the characteristic peak area of the element, n denotes the atomic concentration, and S signifies the sensitivity factor of the corresponding element, it can be deduced that the ratio of N to O atoms in the GaON layer is 7:1. The CB difference between pure GaN and Ga2O3 is approximately 0.1 eV30, indicating that the CB difference at the GaON/GaN interface is less than 0.1 eV. Therefore, the introduction of GaON layer into the GaN NWs through oxidative reconstruction initiates the formation of a type-II GaON/GaN heterojunction interface (Fig. 1h), facilitating the transfer of photogenerated carriers.

Photoelectrochemical measurements of GaON/GaN NWs ultraviolet detector

The electrochemical cell test system comprises a GaON/GaN NWs photoelectrode, Pt mesh counter electrode, an Ag/AgCl reference electrode and an electrochemical workstation, as depicted in Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 7. The electrochemical workstation applies bias voltage to the photoelectrode while recording real-time current signals in the circuit. The electrolyte is 0.5 M H2SO4. Under UV light irradiation, photogenerated holes migrate to the GaON/electrolyte interface for OER, while the photogenerated electrons move towards the NWs substrate and then to the counter electrode for hydrogen evolution reaction (HER), completing the closed current loop. Figure 2b illustrates the photocurrent characteristics of the device using GaN and GaON/GaN NWs as photoelectrodes under 365 nm illumination (255 nm shown in Supplementary Fig. 8), varying optical power from 3 mW/cm2 to 0.2 mW/cm2. The pristine GaN NWs device exhibits low positive photocurrent, with a maximum photocurrent density of only 1.1 μA/cm2 under 3 mW/cm2 illumination. Introducing the GaON layer through oxidative reconstruction significantly enhances the photoresponse characteristics. The maximum photocurrent density of GaON/GaN NWs devices under optical power of 3, 2, 1, 0.5, 0.2 mW/cm2 are found to be 21.39 μA/cm2 (increased to 1945%), 16.34 μA/cm2 (1969%), 10.02 μA/cm2 (1304%), 8.37 μA/cm2 (2262%) and 6.65 μA/cm2 (2271%), respectively. Additionally, peculiar PTE bipolar impulse detection characteristics are observed in GaON/GaN NWs electrochemical cell according Fig. 2b and enlarged curves in Supplementary Fig. 9, demonstrating a distinct two-stage photocurrent behavior. In the first stage, a prominent photocurrent pulse attributed to both the photovoltaic effect (Ipv) and the PTE effect (Ite) is observed, stemming from transient temperature differences along the NWs upon light activation. In the second stage, with constant temperature maintained under continuous UV light irradiation, the photocurrent stabilizes at a lower level after the thermoelectric effect diminishes, primarily reflecting Ipv. Additionally, we conducted a detailed analysis of the factors contributing to the difference in dark current between the two devices. The difference in dark current between the two devices is primarily attributed to several factors. Firstly, the GaON/GaN heterojunction exhibits a type-II band structure, which significantly influences the dark current characteristics of the devices. Secondly, the energy band structure of the type-II GaON/GaN heterojunction enables carrier tunneling across the junction, further increasing the dark current density. Thirdly, the introduction of GaON via post-annealing with oxygen plasma treatment could induce surface states in the NWs and defects at the GaON/GaN heterojunction interface. These surface states participate in electrochemical reactions, further accounting for an increase in dark current density. The linear relationship observed between photocurrent and incident light power (Fig. 2c) across the two stages suggests that GaON/GaN NWs electrochemical cells hold promise for UV light detection. Furthermore, the self-powered characteristics revealed by the I-V curves (Supplementary Fig. 10) indicate their suitability for low-power applications. We also investigated the I-t characteristic curves of both GaN and GaON/GaN devices after prolonged operation and 14 days storage period, as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 11 and Supplementary Figs. 12–13, respectively. The stability test results demonstrate that the devices maintain clear bipolar photocurrent impulses even after long-term operation and storage period, preserving the initial stable current waveform and amplitude. These behaviors underscore the stability of the devices.

a Electrochemical cell design schematic. The blue square region represents the electrolyte. b Switching diagram of light source and I-t characteristics of GaN and GaON/GaN devices under varying optical power illumination, ranging from 3 mW/cm2 to 0.2 mW/cm2. The GaON/GaN devices exhibit photothermoelectric (PTE) bipolar impulse detection characteristics. c Two-stage photocurrent density versus optical power curves. Ipv and Ite represent the current attributed to photovoltaic effect and PTE effect, respectively. Error bars represent the standard deviation of the current density. d The responsivity (R) and specific detectivity (D*) of the two devices are displayed as a function of optical power, with the blue line representing GaN NWs devices and the orange line corresponding to GaON/GaN NWs devices. Error bars represent the standard deviation of the R and D*. e Performance comparison of responsivity and response time between the device in this work and the recently reported electrochemical cells31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42. The yellow, gray and green region represent the Ga2O3-based cells, 1D/2D material cells and III-V group NWs-based cells, respectively.

To further evaluate the enhancement of PTE effect following the incorporation of GaON layer, the responsivity (R) and specific detectivity (D*) of both devices under varying optical power illuminations are presented in Fig. 2d. Responsivity is given by R = (Ilight-Idark)/Pop, quantifying the photoelectric conversion capability of the devices, with Ilight and Idark representing the photocurrent measured during illumination and dark condition, respectively, and Pop is incident light power. Specific detectivity defined as D* = R/(2e×Idark/S)1/2 is used to characterize the detection sensitivity of the device per unit area under unit power illumination, where e is the elementary charge, and S is the effective detector area. The introduction of GaON layer in the electrochemical cell leads to significant enhancements in R and D*. Specially, at an incident light power of 0.2 mW/cm2, R increases from 0.9 mA/W for the GaN device to 17.1 mA/W for the GaON/GaN device. Concurrently, D* increases from 6.4 × 107 Jones to 1.7 × 108 Jones, marking a 266% improvement. The observed increase of approximately 266% does not scale proportionally with the enhancement in responsivity. The specific detectivity is mainly restricted by the dark current of PEC NW devices. The operational environment of the NW device primarily involves an acidic electrolyte with a high ion concentration, which facilitates continuous carrier transport even in the dark state, resulting in an increase in dark current. Furthermore, vacancy defects on the surface of the GaN NWs can negatively impact the quality of the GaON/GaN interface, exacerbating the dark current. As indicated in Supplementary Table 1, although specific detectivity is typically not the primary performance metric for PEC detectors, the GaON/GaN device remains competitive when compared to other similar devices. Figure 2e and Supplementary Table 1 compare the photoresponse performance of GaON/GaN NWs electrochemical cells in this work with those of other recently reported electrochemical cells. Obviously, compared to one-dimensional (1D) or two-dimensional (2D) electrochemical cells31,32,33,34,35, Ga2O3-based electrochemical cells36,37,38,39,40 and other III-V group NWs-based electrochemical cells41,42, the fabricated photodetectors in this work demonstrate high responsivity and high-speed photoresponse. Hence, these findings indicate the exceptional detection capabilities of GaON/GaN NWs electrochemical cells for detecting UV signals.

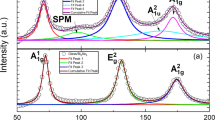

Photothermoelectric effect improves the response speed of electrochemical cells

Figure 3a depicts the I-t characteristic curves of GaN and GaON/GaN NWs electrochemical cells under 365 nm illumination at an optical power of 1 mW/cm2. Additionally, Supplementary Fig. 14 and Supplementary Fig. 15 illustrate the I-t characteristic curves of the two devices under different illumination conditions (255-310 nm). Notably, GaON/GaN NWs devices exhibit higher thermoelectric bipolar pulse photocurrent spikes compared to GaN NWs devices under identical UV light illumination. This enhancement is attributed to the higher electric field within the GaON layer (refer to Fig. 3i), facilitating increased transport of photogenerated carriers to the NWs both ends, thereby increasing the photocurrent density. From the I-t characteristic in Fig. 3a, a pulse detection cycle is identified, delineated into four phases: a sharp rise, a stable plateau, a sharp decline, and another stable plateau, marked as I, II, III, and IV, respectively, as indicated in Fig. 3b. Furthermore, Fig. 3c, d distinctly illustrate transient (Phases I and III) and steady-state (Phase II) photoresponse characteristics across the 255 nm to 365 nm range. Keithley 2611B source-meter drives light emitting diodes (LEDs) to maintain a relatively stable optical power output, calibrated at 1 mW/cm2 across these wavelengths by using Thorlabs PM100D optical power meter. In GaON/GaN NW devices, the current density in phase I and III is primarily governed by the thermoelectric current arising from the photothermoelectric effect. Since the output power of LEDs is identical, the thermoelectric responsivity remains constant, leading to a negligible variation in current with respect to wavelength. In phase II, under UV illumination, the current density is mainly governed by the photovoltaic effect, with photogenerated carriers influenced by the material’s band gap. The larger band gap of GaON makes it more difficult to absorb UV light at 365 nm, resulting in a notable decrease in current. As the wavelength decreases and photon energy increases, GaON is capable of absorbing higher-energy photons, which causes the current behavior at shorter wavelengths to remain relatively stable. Notably, within this wavelength band, the photocurrent amplitudes of phases I/III and phase II in GaON/GaN electrochemical cells are higher than those of GaN devices, underscoring their potential for operation in the UVA-UVC spectrum.

a Under self-powered condition, I-t characteristic curves of GaN and GaON/GaN photoelectrochemical (PEC) devices under 365 nm illumination with an optical power of 1 mW/cm2. b An output current cycle of GaN electrochemical cell and a pulse detection process of GaON/GaN electrochemical cell is illustrated, ‘on’ is the light-on time and ‘off’ signifies the light-off time. One pulse detection cycle can be divided into I-IV phases. c The transient photocurrent density in phase I/III and d stable-state photocurrent density in phase II as a function of wavelengths at 255-365 nm with an optical power of 1 mW/cm2. Error bars represent the standard deviation of the current density in Phases I-III. The PTE pulses in phase I and III of the e GaON/GaN electrochemical cells and the f GaN electrochemical cells at the applied bias voltage of 0 V, 0.2 V and 0.5 V are used to calculate the response time. The response time of the photocurrent pulse spikes of the two devices in g phase I and h phase III varies with the applied bias voltage. The blue line represents GaN NWs electrochemical cells, and the red line corresponds to GaON/GaN NWs electrochemical cells. Res and rec represent the response time and recovery time of devices, respectively. i The electric field distribution diagram in GaON/GaN NW is obtained by COMSOL simulation.

To further investigate the impact of PTE effect on response speed, the response time and recovery time of GaON/GaN NWs and GaN NWs devices under varying bias voltages (0 V, 0.2 V, 0.5 V) are illustrated in Fig. 3e-h. The response time and recovery time in the I-t characteristic refer to the duration for the photocurrent to rise from 10% to 90% of its peak and decline from 90% back to 10%, respectively. Under self-powered conditions, when irradiated with 365 nm light at 1 mW/cm2, the GaN NWs electrochemical cell shows response time and recovery time of 41.3 ms/37.4 ms and 886 ms/529.4 ms for the phases I/III photocurrent spikes. Upon introducing the GaON layer, these times decrease to 16.0 ms/8.8 ms and 82.1 ms/112.2 ms, respectively, owing to the higher electric field in GaON layer expediting the transport of photogenerated carriers. Furthermore, with an applied external bias to the NWs, the photocurrent pulse spikes due to thermoelectric effect in the GaON/GaN device progressively increase with increasing bias voltage. This demonstrates that the electric field profile effectively enhances the photoresponse of the electrochemical cells. Consetquently, under the combined influence of external bias and photothermoelectric effect, a greater number of photogenerated carriers migrate to the NWs ends, thereby amplifying the photocurrent.

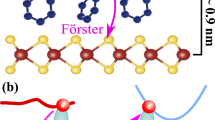

Working mechanism of GaON/GaN NWs photothermoelectric cell

To elucidate the internal physical mechanism underlying the correlation between thermoelectric potential and bipolar current response, simulation analysis is performed using COMSOL Multiphysics, integrating electromagnetic and heat transfer modules. Figure 4a–d illustrates the transient temperature and potential distributions along a single GaON/GaN NW upon the initiation and termination of illumination, respectively. Upon the onset of UV light (Phase I), a temperature gradient generates from GaON side to GaN side. Based on the simulation results from Fig. 4h, i, GaON exhibits a higher Seebeck coefficient than GaN under similar temperature and doping conditions. This higher Seebeck coefficient contributes to a larger thermoelectric figure of merit (ZT) according to the formula ZT = S2σT/k, where S, σ, T and k denote the Seebeck coefficient, electrical conductivity, absolute temperature and thermal conductivity, respectively. The elevated Seebeck coefficient of GaON accelerates temperature increase under UV irradiation, establishing a hot end at the GaON side and a cold end at the bottom of GaN side. The resulting thermoelectric electromotive force directs energy from the substrate toward the GaON side (Fig. 4b), inducing an upward tilt in the energy band, as shown in Fig. 4e. Upon the cessation of UV illumination (Phase III), the bottom region becomes the hot end while the GaON region of NW serves as the cold end, generating a thermoelectric electromotive force from the GaON side toward the substrate (Fig. 4d). This causes a downward tilt in the energy band, illustrated in Fig. 4f. Additionally, the relationship between the thermoelectric response of GaON/GaN device and the temperature distribution is experimentally verified as shown in Supplementary Fig. 16, the overall trend indicates that the GaON/GaN heterojunction NWs device effectively generates a significant temperature gradient, further supporting the thermoelectric effect induced by the temperature variation during light switching.

a The temperature distribution and b potential distribution of GaON/GaN NW upon the onset of ultraviolet (UV) light (Phase I). c The temperature distribution and d potential distribution of NW upon the termination of illumination (Phase III). The energy band distribution diagram of GaON/GaN NW in e Phase I and f Phase III. g The schematic diagram of the PTE effect regulating the carrier transport process and the thermoelectric potential distribution. The color on the NWs represents the temperature distribution. The blue square box represents the electrolyte region. h GaN and GaON supercells under different relaxed states. N, Ga, and O atoms are represented by yellow, purple and red balls, respectively. Four possible structures of GaON in unrelaxed state and the corresponding supercell structures after lattice relaxation are listed. The fourth GaON supercell exhibits the lowest energy after relaxation. The numbers in the figure exhibit the difference of bond length and angle between unrelaxed state and relaxed state. i The Seebeck coefficient calculated according to the GaN supercell structure and the fourth GaON supercell structure under relaxed state.

Figure 4g illustrates the PTE effect governing carrier transport processes and the thermoelectric potential distribution of GaON/GaN NWs electrochemical cells across phases I-IV. Due to the higher electron energy at the hot end, more electrons migrate from the high-temperature region to the low-temperature region. In phase I, the photogenerated holes migrate to GaON side of GaON/GaN NWs under illumination, while electrons are transported to GaN side and collected by the substrate electrode. The resulting thermoelectric electromotive force promotes holes transfer towards the GaON surface to participate in the OER, enhancing the positive current signal. At this stage, photocurrent density (Ipv+Ite1) dominants in phase I. Subsequent stable UV radiation light equalizes temperatures at GaON/GaN NWs, eliminating the light-induced temperature gradient and the thermoelectric force in phase II. As a result, photocurrent rapidly stabilizes to a plateau dominated by photovoltaic effect. Due to the high level of dark current, the current produced by the photovoltaic effect becomes overwhelmed by this background current. In phase III, the GaON/GaN NWs undergo a prolonged steady-state process during phase II before the light is turned off. Upon cessation of illumination, transient temperature differences reverse thermoelectric potential from phase I, resulting in a thermoelectric electromotive force from the GaON to the GaN and generating a negative current spike. Under the influence of the thermoelectric field, both the direction and amplitude of the current are different from the process I, and marked as Ite2. Notably, the change in the temperature gradient between these phases leads to different thermoelectric behaviors, meaning that Ite1≠Ite2. This reverse pulse current serves as a crucial feature upon UV light termination. Finally, in phase IV, as the temperature difference diminishes between NW ends, thermoelectric potential dissipates, sustaining current at the dark current level, marked as Idark.

Electrolyte-assisted inverse encrypted optical communication

Figure 5a illustrates an electrolyte-assisted inverse optical communication system based on GaON/GaN NWs electrochemical cells, demonstrating significant potential for encrypted communication and secure signal transmission. The optical communication system consists of three key components: a signal transmitter, a signal receiver and a display unit. The signal transmitter utilizes a 365 nm LED with adjustable output waveforms, where the states ‘0’ and ‘1’ correspond to the LED being off and on, respectively. The GaON/GaN NWs arrays serve crucially as signal receivers, with the electrochemical workstation capturing and displaying received optical signals on the display screen. Figure 5c illustrates received photocurrent signals decoded as American Standard Code for Information Interchange (ASCII) code ‘N’, ‘J’, ‘U’ sequentially at the signal receiver. In these signals, a forward current spike appears and the subsequent signals are recorded as ‘1’, while a reverse spike appears and the subsequent signals are interpreted as ‘0’. Using codebook 1 in Fig. 5b, the input ‘NJU’ string is correctly decoded. Conversely, intentionally recording ‘0’ after a forward spike and ‘1’ after a reverse spike generates an inverse output signal code, corresponding to the ACSII code is ‘±μa’. The inverse code enables interference encryption for secure communication using a unique key. Thus, the GaON/GaN NWs electrochemical cells successfully achieve electrolyte-assisted encrypted optical communication, showcasing bidirectional communication capabilities with reverse decoding ability.

a A comprehensive schematic diagram of the encrypted optical communication system. b The codebook used for decoding after the electrochemical cell receives the signal. Among them, codebook 1 can correctly decipher the signal, and codebook 2 represents the inverse encrypted code. The American Standard Code for Information Interchange (ASCII) codes corresponding to the string ‘N’, ‘J’, ‘U’ as the input signal is ‘01001110’, ‘01001010’ and ‘01010101’, respectively. c The photocurrent signal received by the electrochemical cell receiver and decode used codebook 1 and codebook 2. The red and purple regions represent the signals decrypted according to codebook 1 and 2, respectively. The ACSII code obtained after decoding ‘01001110’, ‘01001010’ and ‘01010101’ (‘10110001’, ‘10110101’ and ‘10101010’) correspond to the string ‘NJU’ (‘±μa’).

Discussion

In summary, we develop a high-speed and high-response ultraviolet electrochemical cell based on GaON/GaN heterojunction NWs, demonstrating PTE bipolar impulse detection characteristics. The introduction of a GaON layer within the GaON/GaN type-II band structure facilitates efficient transfer of photogenerated carriers. Significantly, transient bipolar impulse photoresponses are observed in GaON/GaN NWs, effectively enhancing device responsivity and accelerating response speed. Without external bias, the response and recovery times of the GaON/GaN PTE detector are reduced to 23.5% and 9.3% respectively compared to pristine devices. The device responsivity shows a 1900% enhancement under weak light irradiation, with a 266% increase in specific detectivity. Furthermore, the thermoelectric mechanism in GaON/GaN NWs is theoretically and experimentally elucidated, highlighting the light-induced Seebeck effect generating transient temperature differences across the NWs upon light activation and deactivation. This leads to significant variations in thermoelectric potential, thereby influencing the transfer and transport process of photogenerated carriers. Consequently, GaON/GaN NW arrays enable the establishment of an electrolyte-assisted inverse encrypted optical communication system, underscoring the potential of PTE impulse detection for future communication and optoelectronic applications.

Methods

Growth of GaN nanowires

GaN NWs were grown on Si (111) substrates by MBE under nitrogen-rich conditions. The oxide on the surface of the substrate was completely removed by buffered oxide etch (BOE) and then placed in the MBE chamber. Subsequently, the substrate was cleaned again by pre-heating to remove surface organic pollutants and hydrophilic groups. Furthermore, the growth of p-GaN NWs is regulated by controlling the flow of Ga source and Mg source through thermal effusion cells.

Construction of GaON/GaN heterojunction

GaON is formed by annealing after oxygen plasma treatment. Before the introduction of GaON layer, GaN NWs were immersed in acetone, ethanol and deionized water for cleaning and blow-dried with a nitrogen gun. Then the GaN NWs were placed in the RIE chamber (Samco, RIE-10NR), the oxygen flow rate was set to 30 sccm, the source power was set to 50 W, and the etching time was 5 min. Furthermore, the samples treated by oxygen plasma were placed in a tube annealing furnace (GSL-1700X-II) and annealed at 800 °C for 30 min in a nitrogen atmosphere to obtain GaON/GaN NWs.

Structural characterization

The morphology of GaON/GaN NWs was obtained by SEM (CARL ZEISS, sigma 500) under the operating voltage of 3 kV. The type of the instrument used in the TEM test is PEI Talos F200x G2, and the operating voltage is 200 kV. The XPS test instrument is Thermo Scientific Nexsa with a monochromatic Al target (E = 1486.68 eV) at an operating voltage of 12 kV, and the vacuum in the sample chamber is less than 10-9 mbar. XPS data were processed and analyzed by Thermo Avantage software. In the room temperature PL test, a 325 nm He-Cd laser was used as the excitation light source and combined with a fluorescence spectrophotometer (Edinburgh Photonics, FLS980) to receive the PL signals.

Photoelectrode preparation and demonstration of electrochemical cell

The original GaN NWs and the GaON/GaN NWs obtained after oxidation reconstruction were washed with acetone, ethanol, and deionized water, and then cut into small pieces with an area of 3 mm2 to start the preparation of the photoelectrode. The oxide layer on the back of the Si substrate is scraped off with a diamond knife to prevent the oxide layer from hindering the formation of ohmic contact. Subsequently, the In-Ga alloy (SPI Supplies) was uniformly coated on the back of the pretreated substrate, and the silver paste was tightly adhered to the copper sheet. The connection area and side wall of Si substrate and copper sheet were sealed with epoxy resin to prevent current leakage, and the performance test was carried out after curing in air for 24 h.

The prepared photoelectrode, Pt mesh counter electrode, Ag/AgCl reference electrode, electrochemical workstation and electrolyte (0.5 M H2SO4) together constitute the PEC detector. The 365 nm LED light is used as the light source to illuminate the photoelectrode, and the light responses of other wavelength LED lights are also tested. The light intensity of the 365 nm LED is calibrated by an optical power meter. In the I-t test, the chopper is used to realize the pulse input of light wave. Finally, the electrochemical workstation (CHI660E) was used to record the photoresponse signals in the loop under light conditions using a three-electrode system.

DFT calculation

The density functional theory (DFT) calculation of ab initio molecular dynamics is carried out by Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP) combined with pseudopotential and projected augmented-planewave. The projector augmented wave (PAW) method is used to illustrate the pseudopotential. The generalized gradient approximation (GGA) with Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) exchange correlation functional is used to describe the electrons correlation. The cutoff energy of the plane wave basis set is set to 700 eV. The K-point sampling grid in the Brillouin zone is set to 9 × 9 × 3 with spacing 0.03 Å. The energy and force convergence criteria of electronic relaxation and ionic relaxation are set to 1 × 10–7 eV and 0.005 eV/Å. The GaN structure is composed of four layers of N atoms and four layers of Ga atoms stacked periodically. According to the relative content of N atom and O atom measured by XPS, the atomic structure of GaON is obtained by setting the ratio of O atoms to N atoms to 1:7 and performing lattice relaxation. The lattice relaxation process allows atoms to spontaneously adjust their positions based on these interaction forces in the calculation until the system reaches its minimum energy state. The lattice structure information obtained by lattice relaxation is utilized as input files, and the electrons in the system are modulated by static self-consistent method under the condition of fixed atomic position coordinates to achieve the lowest energy of the system. BoltzTrap software uses some of the calculation results of VASP as input files, and uses star function and rigid band model to calculate the Seebeck coefficients of GaON and GaN at different carrier concentrations and temperatures.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data generated in this study are provided in the Supplementary Information/Source Data file.

References

Lv, B. C. et al. Local large temperature difference and ultra-wideband photothermoelectric response of the silver nanostructure film/carbon nanotube film heterostructure. Nat. Commun. 13, 1835 (2022).

Zhang, Y. X. et al. Pulse irradiation synthesis of metal chalcogenides on flexible substrates for enhanced photothermoelectric performance. Nat. Commun. 15, 728 (2024).

Lu, X. W. et al. Phonon-enhanced photothermoelectric effect in SrTiO3 ultra-broadband photodetector. Nat. Commun. 10, 138 (2019).

Dai, M. J. et al. On-chip mid-infrared photothermoelectric detectors for full-Stokes detection. Nat. Commun. 13, 4560 (2022).

Teitsworth, T. S. et al. Water splitting with silicon p-i-n superlattices suspended in solution. Nature 614, 270–274 (2023).

Sutter, P., Wimer, S. & Sutter, E. Chiral twisted van der Waals nanowires. Nature 570, 354–357 (2019).

Kim, J. et al. Photon-triggered nanowire transistors. Nat. Nanotechnol. 12, 963–968 (2017).

Kim, Y. M. et al. Short-wave infrared cavity resonances in a single GeSn nanowire. Nat. Commun. 14, 4393 (2023).

Liao, J. W. et al. Highly localized surface plasmon nanolasers via strong coupling. Nano Lett. 23, 4359–4366 (2023).

Liu, T. J. et al. Photonic metamaterial analogue of a continuous time crystal. Nat. Phys. 19, 986–991 (2023).

Yi, R. X. et al. Integrating a nanowire laser in an on-chip photonic waveguide. Nano Lett. 22, 9920–9927 (2022).

Li, J. G. et al. Tunable strong coupling in transition metal dichalcogenide nanowires. Adv. Mater. 34, 2200656 (2022).

Ram, M. S. et al. High-density logic-in-memory devices using vertical indium arsenide nanowires on silicon. Nat. Electron. 4, 914–920 (2021).

Vukajlovic-Plestina, J. et al. Fundamental aspects to localize self-catalyzed III-V nanowires on silicon. Nat. Commun. 10, 869 (2019).

Liu, F. J. et al. Lattice-mismatch-free construction of III-V/chalcogenide core-shell heterostructure nanowires. Nat. Commun. 14, 7480 (2023).

Kolhep, M. et al. Atomic layer deposition and strain analysis of epitaxial GaN-ZnO core-shell nanowires. Nano Lett. 23, 6920–6926 (2023).

Haseman, M. S. et al. Electric field manipulation of defects and Schottky barrier control inside ZnO nanowires. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 15, 30944–30955 (2023).

Chen, H. et al. High-responsivity natural-electrolyte undersea photoelectrochemical photodetector with self-powered Cu@GaN nanowires network. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2302872 (2023).

Fu, J. et al. Interface engineering of Ta3N5 thin film photoanode for highly efficient photoelectrochemical water splitting. Nat. Commun. 13, 729 (2022).

Wang, D. H. et al. Bidirectional photocurrent in p-n heterojunction nanowires. Nat. Electron. 4, 645–652 (2021).

Varadhan, P. et al. An efficient and stable photoelectrochemical system with 9% solar-to-hydrogen conversion efficiency via InGaP/GaAs double junction. Nat. Commun. 10, 5282 (2019).

Fathabadi, M. & Zhao, S. R. Tunnel junction engineered photocarrier dynamics in epitaxial semiconductor nanowires for efficient and ultrafast photoelectrochemical photodetectors. ACS Photonics 10, 1969–1975 (2023).

Ma, H. P. et al. Low-temperature epitaxial growth of high-quality GaON films on ZnO nanowires for superior photoelectrochemical water splitting. Nano Energy 66, 104089 (2019).

Zhang, M. X. et al. High performance self-powered ultraviolet photodetectors based on electrospun gallium nitride nanowires. Appl. Surf. Sci. 452, 43–48 (2018).

Liu, X. et al. Achieving record high external quantum efficiency 86.7% in solar blind photoelectrochemical photodetection. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2201604 (2022).

Fang, S. et al. Balancing the photo-induced carrier transport behavior at two semiconductor interfaces for dual-polarity photodetection. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2202524 (2022).

Chen, S. S., Takata, T. & Domen, K. Particulate photocatalysts for overall water splitting. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2, 17050 (2017).

Li, Z. S. et al. Photoelectrochemical cells for solar hydrogen production: current state of promising photoelectrodes, methods to improve their properties, and outlook. Energy Environ. Sci. 6, 347–370 (2013).

Tian, S. et al. Piezo-phototronic and pyro-phototronic effects enhanced broadband photosensing. Mater. Today 68, 254–274 (2023).

Chen, J. T. et al. Formation and applications in electronic devices of lattice-aligned gallium oxynitride nanolayer on gallium nitride. Adv. Mater. 35, 2208960 (2023).

Xing, C. Y. et al. Ultrasmall bismuth quantum dots: facile liquid-phase exfoliation, characterization, and application in high-performance UV-vis photodetector. ACS Photonics 5, 621–629 (2018).

Li, Z. J. et al. High-performance photo-electrochemical photodetector based on liquid-exfoliated few-layered InSe nanosheets with enhanced stability. Adv. Funct. Mater. 28, 1705237 (2018).

Qiao, H. et al. Self-powered photodetectors based on 0D/2D mixed dimensional heterojunction with black phosphorus quantum dots as hole accepters. Appl. Mater. Today 20, 100765 (2020).

Ma, D. T. et al. Ultrathin GeSe nanosheets: from systematic synthesis to studies of carrier dynamics and applications for a high-performance UV-vis photodetector. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 11, 4278–4287 (2019).

Gao, L. F. et al. Ultra-small 2D PbS nanoplatelets: liquid-phase exfoliation and emerging applications for photo-electrochemical photodetectors. Small 17, 2005913 (2021).

Chen, K. et al. Photoelectrochemical self-powered solar-blind photodetectors based on Ga2O3 nanorod array/electrolyte solid/liquid heterojunctions with a large separation interface of photogenerated carriers. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2, 6169–6177 (2019).

Ni, D. U. et al. ALD oxygen vacancy-rich amorphous Ga2O3 on three-dimensional urchin-like ZnO arrays for high-performance self-powered solar-blind photodetectors. Nanoscale 14, 3159–3165 (2022).

He, C. R. et al. α‑Ga2O3 nanorod array-Cu2O microsphere p-n junctions for self-powered spectrum-distinguishable photodetectors. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2, 4095–4103 (2019).

Zhang, J. H. et al. Solar-blind ultraviolet photodetection of an α-Ga2O3 nanorod array based on photoelectrochemical self-powered detectors with a simple, newly-designed structure. J. Mater. Chem. C. 7, 6867–6871 (2019).

Huang, L. J. et al. A simple, repeatable and highly stable self-powered solar-blind photoelectrochemical-type photodetector using amorphous Ga2O3 films grown on 3D carbon fiber paper. J. Mater. Chem. C. 9, 10354–10360 (2021).

Jiang, M. et al. Self-powered visible photodetector with fast-response speed and high stability based on vertical (In,Ga)N nanowires. OSA Contin. 4, 2381–2390 (2021).

Wang, D. H. et al. Highly uniform, self-assembled AlGaN nanowires for self-powered solar-blind photodetector with fast-response speed and high responsivity. Adv. Opt. Mater. 9, 2000893 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the National Key R&D Program of China (No. 2022YFB3604900) (D.C.), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 62474089, 62104095) (Q.C.), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. U2141241) (D.C.), Provincial Science and Technology Major Project of Jiangsu (No. BG2024030) (H.Y.), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. 021014380239) (Q.C.). The authors acknowledge support from the Ministry of Education Engineering Research Center for Optoelectronic Materials and Chip Technology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.J.C. developed the idea and designed the experiments. J.J.Z. performed device design and fabrication. J.J.Z. and Q.C. carried out data collection and analysis. Q.C., P.F.S., H.F.Y., H.G., B.L., H.L., Y.D.Z. and R.Z. performed the MBE growth and characterizations. J.J.Z., Q.C., S.J.Z., J.W. and J.J.X. conducted and discussed the theoretical calculations. J.J.Z., Q.C. and D.J.C. co-wrote the paper. All the authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Jinyou Xu, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, J., Cai, Q., Shao, P. et al. Observation of ultraviolet photothermoelectric bipolar impulse in gallium-based heterostructure nanowires. Nat Commun 16, 1186 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56617-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56617-z

This article is cited by

-

Facile synthesis of magnetic molecularly imprinted polymer-based electrochemical sensor for enhanced detection of sunset yellow dye

Journal of Materials Science (2026)