Abstract

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), the most common childhood muscular dystrophy, arises from DMD gene mutations, affecting the production of muscle dystrophin protein. Brain dystrophin-gene products are also transcribed via internal promoters. Their deficiency contributes to comorbidities, including intellectual disability ( ~ 22% of patients), autism ( ~ 6%) and attention deficit disorders ( ~ 18%), representing a major unmet need for patients and families. Thus, improvement of their diagnosis and treatment is needed. Dystrophic mouse models exhibit similar phenotypes, where genetic therapies restoring brain dystrophins improve their behaviour. This suggests that future genetic therapies could address both muscle and brain dysfunction in DMD patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is the most common muscular dystrophy affecting children. With an incidence between 1:3500-1:5000 live male births1, the high frequency of de-novo mutations in the X-linked DMD gene is an obstacle to its eradication.

The DMD neuromuscular and cardiac manifestations are well recognised: affected children are diagnosed in the first few years of life and weakness progresses rapidly, leading to loss of ability to walk by the early teens, and subsequent respiratory and cardiac insufficiency resulting in shortened life span. The course is secondary to the loss of dystrophin, a crucial protein that protects the sarcolemma from contraction-induced damage leading to progressive muscle fibres loss. In the last decade, a few pharmacological and genetic therapies that reduce muscle damage have demonstrated efficacy in clinical trials and are at different stages of approval2.

However, DMD is much more than a pure neuromuscular disease: already in 1868, the French neurologist Duchenne De Boulogne in his original report of 13 boys with DMD indicated that six of them had a low IQ, two had language problems and another two had epilepsy3.

These observations have been confirmed in subsequent studies reporting that nearly half of individuals affected by DMD may have a complex neurobehavioural and neurocognitive phenotype. This can variably manifest with specific language disorders, intellectual disability, reading disorder, autism spectrum disorder (ASD), attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), emotional disorders and obsessive-compulsive disorders (OCD)4,5,6.

Work performed in the last decade has shed further light on the variable brain involvement: this largely relates to the location of the DMD mutation along this large gene. We are now aware that the DMD locus produces multiple dystrophin isoforms, which can be differentially affected depending on where the pathogenic variant is located7.

More recent work has improved the understanding of the role of individual isoforms on the brain phenotypes observed, both in the human and mouse models; and on the biological role of these dystrophins8.

Ongoing work is exploring the role of genetic therapy administration, not to the muscle but to the brain, in improving the brain comorbidities in animal models of DMD, potentially paving the way to their future root cause correction.

While these basic research efforts continue, improvement in the screening, assessment, and diagnosis of the brain comorbidities in patients with DMD need to be implemented, together with a systematic assessment of the role that psychotherapy and psychopharmaca may play in managing some of the neurobehavioural consequences. This is not sufficiently addressed by the current standards of care for DMD9, and continues to be a major and growing unmet need for this patient population, especially as life expectancy increases.

The DMD locus, brain DMD isoforms and their pattern of expression

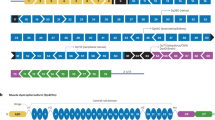

The Xp21.1-p21.2 DMD gene, the largest gene in the human genome, spans nearly 2.5 Mb. It consists of 79 exons and seven internal promoters, each linked to unique first exons giving rise to at least 7 protein products of different sizes7. The full-length isoform (Dp427) is transcribed through 3 different tissue-specific promoters upstream of their first exon sequences, namely Purkinje (P), muscle (M), and cortical (C); they are expressed in different cell types and/or cell compartments in association with different molecular partners, as indicated by transcriptomic studies from Allen Human Brain and BrainSpan atlases (https://atlas.brain-map.org; http://www.brainspan.org) and mouse tissue8,10. While Dp427m is mainly expressed in muscles, likely including smooth muscles of brain arterioles, Dp427c is mainly present in the forebrain and cerebellar neurons. The shorter isoforms named according to their molecular weight, Dp260, Dp140, Dp116, Dp71, and Dp40, are produced by independent downstream promoters and exhibit tissue-specific expression patterns as shown in studies on murine and canine embryos and PC12 cell lines11,12 (Fig. 1). Of note, some of these isoforms also express different alternative splicing that may regulate their subcellular location12. While Dp260 and Dp116 are expressed in the retina and peripheral nerve, respectively, transcriptomic analysis from Allen Human Brain and BrainSpan atlases demonstrated that Dp140 and Dp71/Dp40 are expressed in the brain with larger expression in hippocampus and amygdala8. Dp71 and Dp140 are also expressed outside the central nervous system (CNS). In particular, Dp71 is expressed in many human adult tissues including liver, lung, kidney, and muscle progenitor cells, and skeletal muscle13,14, while Dp140 is also transiently expressed during kidney development15.

The full-length dystrophins (Dp427m,c,p) have a modular structure containing the N-terminus (NT) with F-actin binding sites, an extensive central rod domain that consists of β-spectrin-like repeats (oval shape symbols) with binding sites for F-actin, sarcolemma and multiple cellular proteins, and proline-rich hinge regions (H1-H4) predicted to form triple-helical coiled coils, followed by cysteine-rich (CR) and C-terminal (CT) domains. The shorter dystrophin isoforms (Dp260, Dp140, Dp116, Dp71) exhibit at least the cysteine-rich (CR) and C-terminal (CT) domains, except Dp40 that share the Dp71 first exon but misses the CT domain due to an alternative polyadenylation that generates a stop codon. The CR region contains a WW domain, two EF-hands, a β−dystroglycan binding site, and one ZZ domain. The C-terminal region contains two syntrophin binding sites and a coiled-coil domain interacting with dystrobrevins. The light blue rectangular boxes indicate the position of the promoter region of each isoform. The main tissues expressing the distinct dystrophin isoforms are indicated on the right. The figure was Created in BioRender101.

The expression of these dystrophin isoforms changes during development. Dp140 is more abundant in the foetal brain; Dp427c and to a less extent Dp427m are more highly expressed in adults compared to foetal brain, while Dp71/Dp40 expression is high both during foetal stages and later in human life8. More recently it has been found that Dp427p was absent throughout the development of the brain as shown in transcriptomic analysis from Allen Human Brain and BrainSpan atlases, which is contrast with previous studies8,16.

Pathogenic DMD gene variants, more frequently out-of-frame deletions (65%) or duplication (15%), lead to the absence of dystrophin in muscle resulting in DMD. Allelic variants, often in-frame deletions, can also induce the production of a partially functional dystrophin protein and cause the milder and later onset Becker muscular dystrophy (BMD). The location of the mutation along the DMD gene may differentially impact the multiple dystrophin isoforms (Fig. 1). While all mutations affect muscle and brain production of Dp427, the additional involvement of Dp140 and/or Dp71/40 is related to how further downstream in the DMD gene the mutations are located (Fig. 1).

Role of the different isoforms in the brain

Recent advances in cellular and molecular neuroscience have shed light on the pivotal role of dystrophin isoforms in modulating synaptic transmission and ion channel functioning. The Dp427 isoforms have been implicated in the localisation and functioning of central γ-Aminobutyric acid type A (GABAA) receptors, which has been indirectly confirmed by brain imaging in adults with DMD, although it is not clear if all three full length isoforms contribute to the GABA synaptic functioning17. Immunofluorescence studies in the dystrophic mdx mice carrying a nonsense mutation in exon 23 have demonstrated that the Dp427 deficiency reduces the expression of GABAA receptors in key brain regions, including the amygdala, hippocampus, cerebral cortex, and cerebellum18,19. This disrupts GABAergic inhibitory postsynaptic currents, particularly in the neurons of the basolateral nucleus of the amygdala in response to norepinephrine inputs, which has been associated with abnormal defensive/fear and anxiety behaviours. In hippocampus, altered GABAergic inhibition is posited to enhance NMDA receptor-dependent synaptic plasticity and impacts memory consolidation, as well as synaptic plasticity in cerebellum, with putative impact on both motor and cognitive functions19,20,21,22,23. Recent behavioural studies in mdx mouse models highlighted that Dp427 deficiency may alter the subunit composition of GABAA receptor subtypes at both synaptic and extrasynaptic sites, with a differential impact on distinct brain structures24,25. Using a different strain of dystrophic mice (DBA/2 J mdx mouse), and a different stimulation protocol, Bianchi et al could not fully replicate the findings on synaptic plasticity, highlighting the importance of standardising the experimental procedures related to these assessments26. As these mouse models are deficient in all three Dp427 isoforms, it is not possible to conclude from these studies which one is relevant for the observed phenotypes, or if they all contribute to this.

Regarding Dp140, gene ontology analysis suggested a role during the early stages of neurodevelopment8. The combined absence of both Dp427 and Dp140 in the exon52-deleted mdx52 mouse model has been associated with abnormal social behaviours and diminished glutamatergic transmission, paralleling the ASD-like symptoms of DMD children lacking this isoform27,28. A recent study demonstrated a direct interaction of Dp140 with neuronal voltage-gated Ca2+ channels of the CaV2 subfamily in the mouse brain, using immunoprecipitation and proximity ligation assay techniques, thus providing new avenues for understanding the neurobiology of cognitive dysfunctions in DMD29.

Dp71, the most abundant isoform in the brain, plays a crucial role in the functioning of astrocytes, as demonstrated in mouse brain and human astrocytes’ studies using immunofluorescence and immunocytochemistry techniques30,31. Figure 2 provides a schematic representation of the different brain protein complexes involved with the different dystrophin isoforms.

A Dp427 and Postsynaptic Complexes in Central Inhibitory Synapses. This diagram illustrates the Dp427-associated complex, including α and β dystroglycans, and its role in postsynaptic scaffolding (the black U-shape form represents dystrobrevin). The interaction with key proteins such as Neuroligin-2 (NLGN2), neurexin, S-SCAM, and IQsec3, which are crucial for GABAAR clustering, is depicted. The GABAAR subunits are colour-coded to identify α subunits in light blue, β subunits in purple, and γ2 subunits in red24. B Dp140 complexes in Synapses. This illustration shows the Dp140 complex associated with Cav2.1 and glutamate axis. C Dp71 and its Association with AQP4 and Kir4.1 Channels in Astrocyte Endfeet. This panel demonstrates the interaction of Dp71 with AQP4 and Kir4.1 channels within the perivascular astrocyte endfeet, indicating its potential role in neurovascular coupling102. α-DG α-dystroglycan, β-DG β-dystroglycan, nNOS neuronal nitric oxide synthase, NLGN2 neuroligin 2, IQsec3 gephyrin-associated IQ motif and SEC7 domain-containing protein 3 (also called SynArfGEF), S-SCAM synaptic scaffolding molecule (also called MAGI-2 for membrane-associated guanylate kinase inverted 2); CaV2.1 calcium channels Kir: potassium channels, AQP-4 aquaporin-4, α-Dbv-1 α-dystrobrevin-1, DG dystroglycan, Syn syntrophin. Created in BioRender103.

Genotype/phenotype correlations for DMD patients with mutations affecting the different DMD isoforms

Several studies reported the prevalence of brain related comorbidities in DMD, suggesting a role for the site of mutations and their effect on the expression of the different brain dystrophin isoforms. There is a large variability in the reported prevalence of the individual brain related symptoms due to differences in sample sizes, assessment instruments, and data collection methods4,32,33.

Assessment of neurocognitive and neurobehavioral functioning can be complicated in patients with DMD because of severe motor impairments and consequentially limited social interactions. Normative instruments being used are based on non-motor impaired persons and DMD-specific instruments are not available. However, patients with other severe neuromuscular conditions, such as Spinal Muscular Atrophy34, glycogen storage disorders, neuropathies and muscular dystrophies due to involvement of dystrophin complex members exclusively expressed in muscle35 are not associated with the brain comorbidities observed in DMD. Furthermore, the behavioural and neurocognitive defects in the form of autistic spectrum disorder can often manifest before the occurrence of clear muscle weakness in DMD36.

This, together with clear genotype/phenotype/brain isoforms correlation and the supportive evidence from dystrophic animal models, strongly supports the view that CNS involvement in DMD is a primary consequence of brain dystrophin deficiency, not a secondary phenomenon. Furthermore, in clinical practice and scientific research normative instruments such as the Wechsler intelligence scales prove to be useful33,37. An important challenge for future research is to make a DMD specific and sensitive battery of instruments based on currently available instruments.

Despite these methodological considerations, there is overall consistency in phenotype/genotype correlation concerning specific pathological aspects:

Early development. Developmental milestones in DMD children demonstrate that the milestones requiring more cortical involvement, such as sitting or walking, are typically delayed38, with a gradient that directly correlates with the number of isoforms affected in the CNS and the associated cognitive function39,40. Studies using the Griffiths and the Baileys neurodevelopmental scales suggest that DMD children have a developmental quotient that is on average 1 standard deviation below population mean41. The scores in the subscales such as language, personal, social and eye and hand coordination, are lower in patients with involvement of Dp140 and Dp7141.

Motor function in relation to CNS involvement. Several studies using the North Star Ambulatory Assessment (NSAA) motor function scale that also includes timed items, have demonstrated significantly lower peak achievement in children lacking Dp140 and even lower in those also lacking Dp7139,40,42,43,44. Importantly similar differences in motor function can also be observed in the different mdx mouse models lacking different dystrophin isoforms39.

Intellectual functioning, cognitive and academic abilities. A recent meta-analysis of 32 studies using the Wechsler intelligence scale (preschool, child and adult studies) in 1234 DMD individuals found that the mean full-scale IQ is approximately 1 standard deviation below average norm, i.e full-scale IQ of 84.7633. A review of the global prevalence of intellectual developmental disorder, operationalized as a full-scale IQ of less than 70 (2 standard deviations below the mean of 100), was found in 22% of DMD patients with lower prevalence (12%) in patients with exclusive involvement of Dp427, and 2.5 and 6 fold higher prevalence when Dp140 and Dp71 were also involved45. Neurocognitive functions such as working memory and executive functions (inhibition, switching, problem solving and planning) are often impaired even in boys with a normal full-scale IQ46,47. Other studies have specifically assessed academic abilities, demonstrating a higher prevalence of reading disabilities46,48,49,50 and reduced arithmetic skills51. Academic performances were also lower for mutations affecting both Dp140 and Dp7146. Longitudinal studies have shown that using the Wechsler scales the full-scale IQ is consistent over time37. However, DMD boys with attention and behavioural disorders often had less consistent results with larger full-scale IQ changes over consecutive assessments.

Neuropsychiatric comorbidities. Prevalence rates of these disorders are significantly higher than in the general population. There is, however, a large degree of heterogeneity in reported prevalence rates over different studies32 with prevalence of 0.00 indicating a 0% prevalence and prevalence of 1.00 indicating a 100% prevalence: ASD (13 studies; 0.01 to 0.21 with a mean of 0.06 and 0,0076 in general population), ADHD (10 studies; 0.03 to 0.50 with a mean of 0.18 and 0,034 in general population) and OCD (6 studies; 0.05 to 0.33 with a mean 0.12 and 0,012 in general population). Interestingly, data on the milder BMD variant describes comparable prevalence rates: ASD 0.06, ADHD 0.28 and OCD 0.0732.

While intellectual function is clearly linked to the integrity of the two shorter Dp140 and Dp71 isoforms, the correlation for the behavioural comorbidities is less consistently linked to these isoforms. Indeed, neuropsychiatric aspects such as ASD and to a certain extent also ADHD, can be found across the spectrum of mutations, pointing towards a role for Dp4274,32,52,53. A recent metanalysis has nevertheless suggested that ADHD might be more often associated with boys lacking all the isoforms, i.e. Dp427, Dp140 and Dp7132.

Other studies have more specifically addressed anxiety and fear-based disorders (such as social and separation anxiety, panic disorder and specific phobias) that are reported in 24% to 33% of people with DMD54, hence more common than in the general population5,55,56. Obtaining objective measures of anxiety using behavioural startle responses, children with DMD presented increased unconditioned startle responses to threats. This pathological response is a feature of all DMD children hence likely related to lack of the Dp427 isoforms; in addition, there was evidence that the additional involvement of the Dp140 isoform further increased the abnormal startle response and the risk of anxiety56. Figure 3 gives a schematic representation of ten areas of brain related comorbidities (big ten of Duchenne). It is important to recognise that in clinical practice there may be a complex overlap of these areas. This complexity may hinder adequate screening and assessment57.

Systematic overview of brain related comorbidities in DMD (Big ten of Duchenne) representing four domains and ten areas of (dys)functioning: A neurocognitive (executive functions, working memory and intellectual functioning); B Academics (reading and arithmetic); C emotional: (anxiety and depression; D neuropsychiatric (autism, Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: ADHD, Obsessive Compulsive Disorder: OCD).

Brain Imaging. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) reveals no structural abnormalities; however total brain and grey matter volumes are reduced compared to healthy controls58. Measurements of the white matter show lower fractional anisotropy, and higher diffusivity in DMD children than in healthy controls. Genotype/phenotype correlation revealed that children lacking both Dp427 and Dp140 had more obvious grey matter volume differences and reduced cerebral blood flow compared to those with involvement of Dp427 only58. The connectomic disturbances have been confirmed by tractography and functional MRI studies using a resting state and suggest an over-activation of the default mode network and executive control network, with suppression of primary sensorimotor cortex and cerebellum-visual circuit58,59. The combination of functional and structural MRI together with neuropsychological tests has also allowed one to collect information on the relationship between function and structures and the involvement of neural networks including the cerebellar-thalamo-cortical loop. The pathological white matter connectivity and fibre organization in cerebellar tracts may both contribute to neurocognitive dysfunctions observed in children with DMD59,60,61,62.

Brain comorbidities in DMD female carriers. As DMD is an X-linked disorder, female carriers are typically asymptomatic. However, a recent report found that carrier mothers had poorer cognition performance in attention, working memory, verbal memory, visuospatial skills, and executive functions63. This suggests that there may be a degree of brain involvement in carrier mothers of children with DMD, an aspect that requires further investigation.

Management of neurobehavioural comorbidities in DMD

Management and treatment of the neurobehavioural and neurocognitive comorbidities is of great interest for clinical practice, especially as life expectancy of people affected by DMD increases. It first requires establishing a firm diagnosis, as in clinical practice there is an enormous overlap of neurobehavioral and cognitive symptoms57. Scientific evidence on how to manage these problems or which psychological interventions are recommended is scarce. The international guidelines on diagnosis and management of DMD9 recommend regular screening, psychotherapy and pharmacological treatment, but there is a lack of concrete evidence-based guidelines or standard operating procedures.

The first step in management is psycho-education of affected individuals and families on understanding symptoms, their implications for daily functioning and treatment options. Additionally, educating teachers, physicians and allied professionals on the typical profile of neurocognitive and behavioural problems will result in early detection, prevention and intervention.

Non-pharmacological treatment for DMD have not yet been described. Various psychotherapy approaches such as cognitive behaviour therapy and problem-solving therapy could be effective in influencing the emotional and neuropsychiatric domain of the big ten (domains C and D in Fig. 3). Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) has successfully been used in adult individuals with various muscle diseases such as myotonic dystrophy and proven effective in improving Quality of Life64. Given the brain-related comorbidities in DMD one might speculate on the effectiveness of nutritional interventions as in nutritional psychiatry65, and potentially medical hypnosis contributing to functional changes in brain activities66. Training of neurocognitive disabilities, another domain of the big ten (A in Fig. 3), has proven to be effective in DMD children by using a computerised working memory training67.

An interventional step aimed at domains C and D (Fig. 3) is psychopharmacology. Interestingly and in contrast to the experience of this therapeutic strategy for other similar comorbidities68, this treatment option has not been well documented in the DMD literature69. Brusa, Gadaleta et al. (2022) reviewed all studies between 2000 and 2021 on psychopharmacological treatments for mental disorders in neuromuscular diseases69. They found five studies in DMD: two case reports, two case series (one of them not reporting on symptom improvement) and one observational study without a control group. The observational study on methylphenidate70 in 10 boys with DMD (mean age 8 years) and comorbid ADHD reported a 70% clinical improvement and no significant side effects. The case series of 15 individuals with DMD and OCD71 found a significant effect of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) in 67%; however, side effects were not reported in this study. A recent observational retrospective study72 describes real-world data of 52 males with DMD (mean age 11 years) from two neuromuscular centres treated with psychopharmacology for ADHD, OCD, ASD and anxiety. The clinical condition improved in 54.2% treated with methylphenidate, in 38.9% of the individuals treated with fluoxetine, and in 22.2% treated with risperidone. Anxiolytics were prescribed in two adults (mean age 21) with severe anxiety, with good clinical response. In another more recent study on 19 adult individuals with DMD (mean age 34 years), 42% of them experienced psychiatric symptoms requiring psychoactive drug treatment73. However, this intervention is not readily available to the majority of individuals with DMD, due to lack of evidence-based management recommendations and clear risk/ benefit analyses in patients with additional cardiorespiratory comorbidities. This is becoming increasingly acute as recent evidence suggests that DMD adults with neurodevelopmental comorbidities have poorer survival than those without74. Indeed, the mean age of death in a cohort of 37 young adults with DMD and comorbid neurodevelopmental disorders was 22.5 years, at least 7 years less than the general DMD population, likely related to less compliance with standards of care surveillance and intervention for the myopathy74.

In view of the common cardiac involvement in DMD, there have been concerns for cardiac complications due to stimulant medication which may have important implications in DMD, especially ventricular arrhythmia and sudden cardiac death and SSRIs which may decrease heart rate and systolic blood pressure. No systematic data in DMD has been reported on these issues. In an expert meeting on psychiatric prescribing in DMD75 reassuring data from general populations were described.

Finally, it is worth noting that a combination of psychopharmacological treatment and psychotherapy has been shown to be superior in improving quality of life in depression76,77, but there is no experience of this combinatorial approach as yet in DMD.

Deep phenotyping of DMD mouse models with mutations affecting differently the different isoforms

A variety of dystrophic animal models has provided invaluable insights into the aetiology and neurobiology of DMD78. DMD mouse models carry a variety of spontaneous, chemically- and transgenically-induced mutations along the DMD gene, leading to differential loss of one, several or all brain dystrophins, thus offering relevant tools to decipher the specific behavioural profile of animals missing different isoforms (Fig. 4A).

A Expression pattern of brain dystrophins in dystrophin-deficient mouse lines. Mutation position and differential expression of the three brain dystrophins are shown for mouse lines carrying spontaneous mutations (mdx), chemically-induced mutations (mdx4cv, mdx3cv), transgenic deletion of a specific exon (mdx52) or whole dmd gene (dmd-null), and transgenic insertion (Dp71-null). E: exon; I: intron; del-: deletion; ( + ) protein expressed; (-) protein absent. B–E Illustrative images of the main behavioural tests that revealed key phenotypes in DMD mouse models. The tests tackled distinct brain-related functions including: B motor functions using the inverted grid (left) and rotarod (right) tests; C emtional and stress reactivity following scruff restraint (left drawing) or using elevated plus maze, light-dark choice and open-field anxiety tests (three last drawings, respectively); D social behaviour during social approach test (left) and socially-induced ultrasonic vocalisations (right); E cognitive functions using, respectively from top to bottom drawings, an object recognition test, fear conditioning, spatial working memory tasks in radial or T mazes, and spatial learning tasks in water maze. Created in BioRender104.

Behavioural studies involve controlled conditions, comparisons to wild-type littermate mice and standardised experimental tests designed to tackle specific cognitive and behavioural processes, and previously validated by the neuroscience community using brain lesions, pharmacology, optogenetics and mouse models of other neurodevelopmental diseases (Fig. 4B). The Dp427-deficient mdx mouse model, the most widely studied model, exhibits delays in some learning tasks and selective long-term memory deficits implicating memory consolidation, and behavioural alterations79,80. Mdx mice have deficits in tests involving hippocampal or amygdala-dependent recognition, spatial and fear memories, and exhibit behavioural disturbances including changes in emotional, depression-related and social behaviour. Their most robust phenotype is a dramatically enhanced stress reactivity, characterized by abnormal defensive behaviour referred to as an unconditioned fear in response to mild stressors such as scruff restraint. This was attributed to amygdala dysfunction and GABAergic disinhibition19,25,81. The abnormal fear response is conserved in mammalian dystrophic models (pigs, in which dystrophin deficiency causes a severe porcine stress syndrome, rats)82,83 and occurs in boys with DMD5,56. While moderate stress in the mdx mice manifests itself with the temporary immobility (unconditioned fear response), more severe stressors are associated with lethality in these dystrophic mice, likely related to their exaggerated neuroendocrine sensitivity to stressors84.

Recent studies compared behavioural performance of mdx mice lacking Dp427 alone to that of mdx52 or mdx4cv mice lacking both Dp427 and Dp140, and to mdx3cv and Dmd-null mice lacking all dystrophins (Table 1). All dystrophic mouse models display enhanced anxiety, in line with the enhanced anxiety also reported in children with DMD regardless of their genotype, supporting a role for the Dp427 isoforms in emotional disturbances52. However, mdx52 mice exhibit higher anxiety and more impaired fear learning and memory compared to mdx mice, suggesting that Dp140 loss aggravates emotional disturbances85. In mdx mice and another model lacking Dp427 and Dp140 (mdx4cv), mild changes in short-term memory, discrimination learning, and movement patterns have also been reported, suggesting a role for Dp427 in these functions86. A study highlighted the ASD-like behaviours present in mdx52 mice lacking Dp140, with reduced glutamatergic transmission in basolateral amygdala (BLA) pyramidal neurons compared to wild-type and mdx mice, suggesting a role for Dp140 in ASD-related behaviour28. Along similar lines to what is described in humans, the dystrophic mice lacking both Dp427 and Dp140 (mdx52) or all dystrophins (Dmd-null) have more severe motor dysfunction compared to Dp427-deficient mdx mice, suggesting a role for Dp140 in contributing to coordination and motor performance39. The studies in Dmd-null mice are scarce and inconclusive regarding the functional impact of Dp71 deficiency39,87,88. However, mice with a selective loss of Dp71 (Dp71-null) display alterations in working memory, cognitive flexibility and social behaviour89,90, in line with what is observed in children with distal mutations.

Mouse studies thus provide critical and translational insights into the genotype-phenotype relationships, the nature of altered cognitive processes and the brain circuits underlying brain-related comorbidities in DMD (Table 1). Moreover, preclinical rescue studies confirmed the central origin of several phenotypes of DMD mouse models and validated their use as biomarkers for preclinical evaluations of therapies (Fig. 5).

A Possible exon skipping strategies to restore the open reading frame in DMD mouse model carrying a deletion of exon 52. Exon 52 deleted dmd mRNA is out of frame and no functional Dp427 and Dp140 are thus produced. Skipping of exon 51 can restore Dp427 expression but not Dp140 expression because exon 51 contains Dp140 start codon. In contrast, exon 53 skipping offers the opportunity to restore both Dp427 and Dp140. B The brain delivery of genetic tools allowing dystrophin isoforms restoration improves key neurobehavioural phenotypes in DMD mouse models including emotional and stress reactivity (e.g. using fear response, elevated plus maze, light-dark choice tests), cognitive functions using a fear conditioning test and social behaviour during social approach test. This figure was created using Biorender.com, panel A and105 B (Created in BioRender106).

Dp427-deficient DE50-MD dogs have been deeply phenotyped with the demonstration of subtle structural abnormalities in the grey matter91 as detected by brain MRI associated with a neurocognitive phenotype including reduced attention, problem solving and exploration of novel objects92. Likewise, an exon52-deleted pig model was shown to display some impairments in cognitive abilities93. The presence of brain anomalies, abnormal stress reactivity and cognitive deficits in large animal models supports part of the data reported in mouse models and have translational significance. However, the variety of mutations expressed in large animal models remains limited, and the generation of new dog or pig models holding distinct mutations would help address genotype-phenotype relationships and efficacy of therapeutic interventions, as in the studies of mouse models. The functional data on animal models should be interpreted with caution, perhaps particularly mouse data since DMD mouse models fail to reproduce major DMD skeletal muscle and heart manifestations. This, however, is advantageous to carry out behavioural studies with limited influence of motor functions on cognitive performance. The current mouse data suggest Dp427-dependent emotional disturbances, which are conserved in various animal models and present but still underrated in patient studies. The loss of Dp140 appears to worsen some phenotypes, such as emotional disturbances and motor performance, which seems relevant to the global increase in the severity of central alterations in patients. In contrast, extending mouse data to genotype/phenotype correlations in patients for social behaviour disturbances and cognitive/executive performance is still premature and may require additional studies. Despite the limitations of the mouse models, it would undoubtedly be beneficial to continue phenotyping of patients and animal models in parallel, and to encourage cross-fertilisation between these two fields of research.

Genetic therapies for restoring brain dystrophin production in the different mouse models

Therapeutic approaches based on RNA therapies (i.e. antisense oligonucleotides [ASO] to induce exon-skipping and restoration of the reading frame in individuals with DMD with deletions) or adeno-associated viral gene therapies have made tremendous progress for the treatment of DMD in the past few years and reached market approval in the US and Japan. However, none of these therapies addresses the brain comorbidities associated with DMD, mostly due to their inability to cross the blood brain barrier (BBB). Until recently the therapeutic development has focused on addressing the DMD muscle pathology. However, several studies have recently demonstrated encouraging neurobehavioural improvements following genetic treatments in mouse models of DMD. Work in the mdx mouse model lacking only the Dp427 isoform showed that direct intracerebroventricular (ICV) infusion of an ASO made of phosphorodiamidate morpholino oligomer (PMO) lead to a partial restoration of brain Dp427 and an improvement of the characteristic fear-motivated defensive behaviour in these mice19. This was further confirmed using a different type of ASO made of tricyclo-DNA, administered intravenously and capable of normalising the unconditioned fear response thanks to its ability to cross the BBB albeit at very low levels94. Other studies in mdx mice reported recovery of GABAA-receptor clustering and normalisation of hippocampal synaptic plasticity, following partial rescue of hippocampal dystrophin induced by intra-hippocampal administration of adeno-associated virus vectors encoding a specific U7snRNA that induced continuous production of the exon skipping ASO95. These earlier studies focused on the exaggerated fear response but not on the memory deficits that also characterise this model. In 2022, however, ICV administration of tricyclo-DNA-ASO not only rescued expression brain Dp427 isoforms expression but also significantly restored long-term memory retention of mdx mice in an object recognition task. These novel findings suggest for the first time that postnatal re-expression of brain dystrophin could reverse or at least alleviate some cognitive deficits associated with DMD24. These studies also highlighted a dose-dependent restoration of Dp427 following administration of various doses of ASO, associated with a dose-dependent decrease of the abnormal unconditioned fear responses.

Given that the combined loss of both Dp427 and Dp140 in mdx52 mice may be associated with higher emotional disturbances as compared to Dp427-only deficient mdx mice85, and because this also induces abnormal social behaviour28, further experiments were recently performed in the mdx52 mouse model. The evaluation of therapeutic approaches in this model is particularly relevant, as it holds a deletion of exon 52, a region frequently found mutated in individuals with DMD. Moreover, this particular exon deletion is amenable to two possible exon-skipping strategies for which exon skipping drugs are already approved (for systemic treatment). Skipping of exon 51 will restore solely Dp427 expression, leaving the Dp140 isoform absent due to its reliance on exon 51 for the start codon. In contrast, exon 53 skipping offers the opportunity to restore both Dp427 and Dp140 isoforms (Fig. 5A). Recent studies exhibited that ICV administration of tricycloDNA-ASO targeting the Dmd exon 51 resulted in partial Dp427 restoration in the brain of mdx52 mice and significantly reduced anxiety and unconditioned fear96. Additionally, this partial rescue of Dp427 fully normalised the acquisition of fear conditioning, while fear memory tested 24 h later was only partially improved. Another study on the same mouse model, demonstrated that either injecting a PMO-ASO targeting Dmd exon 53 directly into the basolateral amygdala (BLA) or administering directly in the same region Dp140 mRNA-loaded polyplex nanomicelles restored Dp140 expression. This intervention also ameliorated the deficits in glutamatergic transmission and improved the abnormal social behaviour in 8-week-old mdx52 mice, corresponding to late adolescent / young adult stages in humans28. Altogether, these studies provide encouraging data and reveal that postnatal partial restoration of the two most commonly affected dystrophin isoforms, Dp427 and Dp140, can improve the neurocognitive and neurobehavioral and emotional deficits associated with their absence in the brain of DMD mouse models. Although this offers promising avenues for future treatment of brain comorbidities in individuals with DMD, the translational gap between mouse and human remains a significant challenge, as illustrated by the incomplete functional benefit induced by these genetic therapies in muscles.

Conclusion and future directions

In the last decade, there has been very considerable progress in addressing the molecular basis for the brain involvement which characterises people affected by DMD. A clear role for the different dystrophin isoforms in regulating GABAergic and glutamergic synaptic transmission and ion channel activity, and maintaining a physiological neural balance, has emerged. Deep phenotyping of different dystrophic models is allowing us to dissect the contribution of the individual dystrophin isoforms on discrete neurobehavioural aspects of the condition, and genetic therapies provide clear evidence for postnatal improvement of at least some of the comorbidities. This suggests that the brain phenotype induced by dystrophin deficiency is not exclusively developmental in origin, providing hope for future development of these brain targeted approaches.

The considerable neurobiological advances on the role of dystrophins in the brain are largely related to the studies on the dystrophic mouse models. Linking mouse model data to human neurobehavioral functioning is an important challenge. The human neurobehavioral data are more complex and while some traits found in the mouse can be clearly recognised in the affected boys, there is variability of their severity and prevalence. Nevertheless, several symptoms are now well recognised and both screening and diagnostic assessment of ASD, ADHD, OCD, anxiety, depression, reading and arithmetic disorders and neurocognitive disorders such as working memory and executive function problems should be systematically performed in affected children. It is possible that in the future genetic therapies focused on brain dystrophin deficiency could provide an exciting resource to address the root cause of these comorbidities, although their modality of administration, efficacy and biodistribution in larger animal models requires further work. In the meantime, the current psychopharmaceutic should be more systematically used, to address the current unmet needs for these individuals. Furthermore, the characterisation of the links between DMD and other conditions, i.e. OCD, ADHD, intellectual disability may result in further insight on the role that specific neurotransmission pathways play in these comorbidities.

Search strategy

We searched PubMed for articles published in English from 1st January 2019, to January 1st, 2024, with the search terms “Duchenne”, “dystrophinopathy” “mdx” or the causative gene, “DMD”, and “brain”. This resulted in 133 publications in Pubmed in the last 5 years.

We generated the final reference list based on topics that fit the scope of this review and included landmark papers as well.

References

Crisafulli, S. et al. Global epidemiology of Duchenne muscular dystrophy: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Orphanet. J. Rare Dis. 15, 141 (2020).

Markati, T. et al. Emerging therapies for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Lancet Neurol. 21, 814–829 (2022).

Duchenne, G.-B. (1806-1875). A. du texte. De la paralysie musculaire pseudo-hypertrophique, ou paralysie myo-sclérosique / par le Dr Duchenne (de Boulogne). (1868).

Pascual-Morena, C. et al. Global prevalence of intellectual developmental disorder in dystrophinopathies: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Dev. Med Child Neurol. 65, 734–744 (2023).

Darmahkasih, A. J. et al. Neurodevelopmental, behavioral, and emotional symptoms common in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Muscle Nerve 61, 466–474 (2020).

Hendriksen, J. G. M. & Vles, J. S. H. Neuropsychiatric Disorders in Males With Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy: Frequency Rate of Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), Autism Spectrum Disorder, and Obsessive—Compulsive Disorder. 10.1177/0883073807309775 23, 477–481 (2008).

Muntoni, F., Torelli, S. & Ferlini, A. Dystrophin and mutations: One gene, several proteins, multiple phenotypes. Lancet Neurol. 2, 731–740 (2003).

Doorenweerd, N. et al. Timing and localization of human dystrophin isoform expression provide insights into the cognitive phenotype of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Sci. Rep. 7, 12575(2017).

Birnkrant, D. J. et al. Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 1: diagnosis, and neuromuscular, rehabilitation, endocrine, and gastrointestinal and nutritional management. Lancet Neurol. 17, 251 (2018).

García-Cruz, C. et al. Tissue-and cell-specific whole-transcriptome meta-analysis from brain and retina reveals differential expression of dystrophin complexes and new dystrophin spliced isoforms. Hum. Mol. Genet 32, 659–676 (2023).

Hildyard, J. C. W. et al. Single-transcript multiplex in situ hybridisation reveals unique patterns of dystrophin isoform expression in the developing mammalian embryo. Wellcome Open Res 5, 32724863 (2020).

Sánchez, A., Aragón, J., Ceja, V., Rendon, A. & Montanez, C. Nuclear transport and subcellular localization of the dystrophin Dp71 and Dp40 isoforms in the PC12 cell line. Biochem Biophys. Res Commun. 630, 125–132 (2022).

Bar, S. et al. A novel product of the Duchenne muscular dystrophy gene which greatly differs from the known isoforms in its structure and tissue distribution. Biochem. J. 272, 557–560 (1990).

Tennyson, C. N., Dally, G. Y., Ray, P. N. & Worton, R. G. Expression of the dystrophin isoform Dp71 in differentiating human fetal myogenic cultures. Hum. Mol. Genet 5, 1559–1566 (1996).

Durbeej, M., Jung, D., Hjalt, T., Campbell, K. P. & Ekblom, P. Transient expression of Dp140, a product of the Duchenne muscular dystrophy locus, during kidney tubulogenesis. Dev. Biol. 181, 156–167 (1997).

Holder -Masato Maeda, E. & Bies, R. D. Expression and regulation of the dystrophin Purkinje promoter in human skeletal muscle, heart, and brain. Hum. Genet 97, 232–239 (1996).

Suzuki, Y., Higuchi, S., Aida, I., Nakajima, T. & Nakada, T. Abnormal distribution of GABAA receptors in brain of duchenne muscular dystrophy patients. Muscle Nerve 55, 591–595 (2017).

Knuesel, I. et al. Short communication: altered synaptic clustering of GABAA receptors in mice lacking dystrophin (mdx mice). Eur. J. Neurosci. 11, 4457–4462 (1999).

Sekiguchi, M. et al. A deficit of brain dystrophin impairs specific amygdala GABAergic transmission and enhances defensive behaviour in mice. Brain 132, 124–135 (2009).

Pereira da Silva, J. D. et al. Altered release and uptake of gamma-aminobutyric acid in the cerebellum of dystrophin-deficient mice. Neurochem. Int. 118, 105–114 (2018).

Vaillend, C. & Billard, J. M. Facilitated CA1 hippocampal synaptic plasticity in dystrophin-deficient mice: Role for GABAA receptors? Hippocampus 12, 713–717 (2002).

Wu, W. C., Bradley, S. P., Christie, J. M. & Pugh, J. R. Mechanisms and consequences of cerebellar purkinje cell disinhibition in a mouse model of duchenne muscular dystrophy. J. Neurosci. 42, 2103–2115 (2022).

Kreko-Pierce, T. & Pugh, J. R. Altered synaptic transmission and excitability of cerebellar nuclear neurons in a mouse model of duchenne muscular dystrophy. Front Cell Neurosci. 16, 926518 (2022).

Zarrouki, F. et al. Abnormal expression of synaptic and extrasynaptic gabaa receptor subunits in the dystrophin-deficient mdx mouse. Int J. Mol. Sci. 23, 23 (2022).

Vaillend, C. & Chaussenot, R. Relationships linking emotional, motor, cognitive and GABAergic dysfunctions in dystrophin-deficient mdx mice. Hum. Mol. Genet 26, 1041–1055 (2017).

Bianchi, R. et al. Hippocampal synaptic and membrane function in the DBA/2J-mdx mouse model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 104, 103482 (2020).

Araki, E. et al. Targeted Disruption of Exon 52 in the Mouse Dystrophin Gene Induced Muscle Degeneration Similar to That Observed in Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. Biochem Biophys. Res Commun. 238, 492–497 (1997).

Hashimoto, Y. et al. Brain Dp140 alters glutamatergic transmission and social behaviour in the mdx52 mouse model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Prog. Neurobiol. 216, 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2022.102288 (2022).

Leyva-Leyva, M. et al. Identification of Dp140 and α1-syntrophin as novel molecular interactors of the neuronal CaV2.1 channel. Pflug. Arch. 475, 595–606 (2023).

Belmaati Cherkaoui, M. et al. Dp71 contribution to the molecular scaffold anchoring aquaporine-4 channels in brain macroglial cells. Glia 69, 954–970 (2021).

Lange, J. et al. Dystrophin deficiency affects human astrocyte properties and response to damage. Glia 70, 466–490 (2022).

Pascual-Morena, C. et al. Dystrophin genotype and risk of neuropsychiatric disorders in dystrophinopathies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Neuromuscul. Dis. 10, 159 (2023).

Weerkamp, P. M. M. et al. Wechsler scale intelligence testing in males with dystrophinopathies: a review and meta-analysis. Brain Sci 12, 10.3390/brainsci12111544 (2022).

von Gontard, A. et al. Intelligence and cognitive function in children and adolescents with spinal muscular atrophy. Neuromuscul. Disord. 12, 130–136 (2002).

D’alessandro, R. et al. Assessing cognitive function in neuromuscular diseases: A pilot study in a sample of children and adolescents. J. Clin. Med 10, 10 (2021).

Lee, I. et al. The hidden disease: delayed diagnosis in duchenne muscular dystrophy and co-occurring conditions. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 43, e541–e545 (2022).

Chieffo, D. P. R. et al. A longitudinal follow-up study of intellectual function in duchenne muscular dystrophy over age: is it really stable? J. Clin. Med 12, 12 (2023).

Norcia, G. et al. Early gross motor milestones in duchenne muscular dystrophy. J. Neuromuscul. Dis. 8, 453 (2021).

Chesshyre, M. et al. Investigating the role of dystrophin isoform deficiency in motor function in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 13, 1360 (2022).

Coratti, G. et al. Longitudinal natural history in young boys with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Neuromuscul. Disord. 29, 857–862 (2019).

Pane, M. et al. Early neurodevelopmental assessment in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Neuromuscul. Disord. 23, 451–455 (2013).

Wijekoon, N. et al. Duchenne muscular dystrophy from brain to muscle: the role of brain dystrophin isoforms in motor functions. J. Clin. Med 12, 5637 (2023).

Zambon, A. A. et al. Peak functional ability and age at loss of ambulation in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Dev. Med Child Neurol. 64, 979 (2022).

Coratti, G. et al. Age, corticosteroid treatment and site of mutations affect motor functional changes in young boys with Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. PLoS One 17, N/A-N/A (2022).

Pascual-Morena, C. et al. Intelligence quotient–genotype association in dystrophinopathies: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuropathol. Appl Neurobiol. 49, e12914 (2023).

Fee, R. J., Montes, J., Stewart, J. L. & Hinton, V. J. Executive Skills and Academic Achievement in the Dystrophinopathies. J. Int. Neuropsychological Soc. 24, 928–938 (2018).

Battini, R. et al. Longitudinal data of neuropsychological profile in a cohort of Duchenne muscular dystrophy boys without cognitive impairment. Neuromuscul. Disord. 31, 319–327 (2021).

Billard, C., Gillet, P., Barthez, M. A., Hommet, C. & Bertrand, P. Reading ability and processing in Duchenne muscular dystrophy and spinal muscular atrophy. Dev. Med Child Neurol. 40, 12–20 (1998).

Hendriksen, J. G. M. & Vles, J. S. H. Are Males With Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy at Risk for Reading Disabilities? Pediatr. Neurol. 34, 296–300 (2006).

Astrea, G. et al. Reading impairment in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: A pilot study to investigate similarities and differences with developmental dyslexia. Res Dev. Disabil. 45–46, 168–177 (2015).

Schmidt-Kastner, R. Genomic approach to selective vulnerability of the hippocampus in brain ischemia-hypoxia. Neuroscience 309, 259–279 (2015).

Ricotti, V. et al. Neurodevelopmental, emotional, and behavioural problems in Duchenne muscular dystrophy in relation to underlying dystrophin gene mutations. Dev. Med Child Neurol. 58, 77–84 (2016).

Pane, M. et al. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and cognitive function in duchenne muscular dystrophy: Phenotype-genotype correlation. J. Pediatrics 161, 705–709.e1 (2012).

Pascual-Morena, C. et al. Prevalence of Neuropsychiatric Disorders in Duchenne and Becker Muscular Dystrophies: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Arch. Phys. Med Rehabil. 103, 2444–2453 (2022).

Trimmer, R. E., Mandy, W. P. L., Muntoni, F. & Maresh, K. E. Understanding anxiety experienced by young males with Duchenne muscular dystrophy: a qualitative focus group study. Neuromuscul. Disord. 34, 95–104 (2024).

Maresh, K. et al. Startle responses in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: a novel biomarker of brain dystrophin deficiency. Brain 146, 252–265 (2023).

Hendriksen, J. G. M. et al. 249th ENMC International Workshop: The role of brain dystrophin in muscular dystrophy: Implications for clinical care and translational research, Hoofddorp, The Netherlands, November 29th–December 1st 2019. Neuromuscul. Disord. 30, 782–794 (2020).

Doorenweerd, N. et al. Reduced cerebral gray matter and altered white matter in boys with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Ann. Neurol. 76, 403–411 (2014).

Cheng, B. et al. Connectomic disturbances in Duchenne muscular dystrophy with mild cognitive impairment. Cereb. Cortex 33, 6785–6791 (2023).

Biagi, L. et al. Neural substrates of neuropsychological profiles in dystrophynopathies: A pilot study of diffusion tractography imaging. PLoS One 16, 10.1371/journal.pone.0250420 (2021).

Doorenweerd, N. et al. Resting-state functional MRI shows altered default-mode network functional connectivity in Duchenne muscular dystrophy patients. Brain Imaging Behav. 15, 2297 (2021).

Preethish-Kumar, V. et al. In Vivo Evaluation of White Matter Abnormalities in Children with Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy Using DTI. https://doi.org/10.3174/ajnr.A6604.

Demirci, H. et al. Cognition of the mothers of patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Muscle Nerve 62, 710–716 (2020).

Rose, M. et al. A randomised controlled trial of acceptance and commitment therapy for improving quality of life in people with muscle diseases. Psychol. Med 53, 3511 (2023).

Adan, R. A. H. et al. Nutritional psychiatry: Towards improving mental health by what you eat. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 29, 1321–1332 (2019).

Wolf, T. G., Faerber, K. A., Rummel, C., Halsband, U. & Campus, G. Functional changes in brain activity using hypnosis: a systematic review. Brain Sci 12, 10.3390/brainsci12010108 (2022).

Hellebrekers, D. M. J. et al. Computerized working memory training in males with Duchenne muscular dystrophy: A single case experimental design study. Neuropsychol. Rehabil. 33, 1325–1348 (2023).

Cortese, S. et al. Psychopharmacology in children and adolescents: unmet needs and opportunities. Lancet Psychiatry 11, 143–154 (2024).

Brusa, C. et al. Psychopharmacological treatments for mental disorders in patients with neuromuscular diseases: a scoping review. Brain Sci. 12, 10.3390/brainsci12020176 (2022).

Lionarons, J. M. et al. Methylphenidate use in males with Duchenne muscular dystrophy and a comorbid attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 23, 152–157 (2019).

Lee, A. J., Buckingham, E. T., Kauer, A. J. & Mathews, K. D. Descriptive phenotype of obsessive compulsive symptoms in males with Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. J. Child Neurol. 33, 572 (2018).

Weerkamp, P. M. M. et al. Psychopharmaceutical treatment for neurobehavioral problems in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: a descriptive study using real-world data. Neuromuscul. Disord. 33, 619–626 (2023).

Gadaleta, G. et al. Adults living with Duchenne muscular dystrophy: old and new challenges in a cohort of 19 patients in their third to fifth decade. Eur. J. Neurol. 31, e16060 (2024).

Nart, L., Desikan, M., Pietrusz, A., Savvatis, K. & Quinlivan, R. Neurodiversity, treatment compliance and survival in adults with Duchenne muscular dystrophy: a single-centre retrospective cohort review. Neuromuscul. Disord. 35, 13–18 (2024).

Bouquillon, L. et al. Workshop report: Workshop on psychiatric prescribing and psychology testing and intervention in children and adults with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Res. Ideas Outcomes 10 10, e119243 (2024).

Kamenov, K., Twomey, C., Cabello, M., Prina, A. M. & Ayuso-Mateos, J. L. The efficacy of psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy and their combination on functioning and quality of life in depression: a meta-analysis. Psychol. Med 47, 414–425 (2017).

DeRubeis, R. J., Siegle, G. J. & Hollon, S. D. Cognitive therapy versus medication for depression: treatment outcomes and neural mechanisms. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 9, 788–796 (2008).

Van Putten, M. et al. Mouse models for muscular dystrophies: an overview. https://doi.org/10.1242/dmm.043562 (2020).

Vaillend, C., Billard, J. M. & Laroche, S. Impaired long-term spatial and recognition memory and enhanced CA1 hippocampal LTP in the dystrophin-deficient Dmdmdx mouse. Neurobiol. Dis. 17, 10–20 (2004).

Bellissimo, C. A. et al. Memory impairment in the D2.mdx mouse model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy is prevented by the adiponectin receptor agonist ALY688. Exp. Physiol. 108, 1108–1117 (2023).

Phillips, R. G. & LeDoux, J. E. Differential contribution of amygdala and hippocampus to cued and contextual fear conditioning. Behav. Neurosci. 106, 274–285 (1992).

Nonneman, D. J., Brown-Brandl, T., Jones, S. A., Wiedmann, R. T. & Rohrer, G. A. A defect in dystrophin causes a novel porcine stress syndrome. BMC Genomics 13, 1–9 (2012).

Caudal, D. et al. Characterization of brain dystrophins absence and impact in dystrophin-deficient Dmdmdx rat model. PLoS One 15, e0230083 (2020).

Razzoli, M. et al. Social stress is lethal in the mdx model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. EBioMedicine 55, 102700 (2020).

Saoudi, A. et al. Emotional behavior and brain anatomy of the mdx52 mouse model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Dis. Model Mech. 14, dmm049028 (2021).

Verhaeg, M. et al. Learning, memory and blood–brain barrier pathology in Duchenne muscular dystrophy mice lacking Dp427, or Dp427 and Dp140. Genes Brain Behav. 23, 10.1111/gbb.12895 (2024).

Vaillend, C. et al. Spatial discrimination learning and CA1 hippocampal synaptic plasticity in mdx and mdx3cv mice lacking dystrophin gene products. Neuroscience 86, 53–66 (1998).

Vaillend, C. & Ungerer, A. Behavioral characterization of mdx3cv mice deficient in C-terminal dystrophins. Neuromuscul. Disord. 9, 296–304 (1999).

Chaussenot, R., Amar, M., Fossier, P. & Vaillend, C. Dp71-dystrophin deficiency alters prefrontal cortex excitation-inhibition balance and executive functions. Mol. Neurobiol. 56, 2670–2684 (2019).

Miranda, R. et al. Social and emotional alterations in mice lacking the short dystrophin-gene product, Dp71. Behav. Brain Funct. 20, 10.1186/s12993-024-00246-x (2024).

Crawford, A. H., Hornby, N. L., de la Fuente, A. G. & Piercy, R. J. Brain magnetic resonance imaging in the DE50-MD dog model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy reveals regional reductions in cerebral gray matter. BMC Neurosci. 24, 1–9 (2023).

Crawford, A. H. et al. Validation of DE50-MD dogs as a model for the brain phenotype of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. DMM Dis. Model. Mech. 15, dmm049291 (2022).

Stirm, M. et al. A scalable, clinically severe pig model for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. DMM Dis. Model. Mech. 14, dmm049285 (2021).

Goyenvalle, A. et al. Functional correction in mouse models of muscular dystrophy using exon-skipping tricyclo-DNA oligomers. Nat. Med. 2015 21:3 21, 270–275 (2015).

Dallérac, G. et al. Rescue of a dystrophin-like protein by exon skipping normalizes synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus of the mdx mouse. Neurobiol. Dis. 43, 635–641 (2011).

Saoudi, A. et al. Partial restoration of brain dystrophin by tricyclo-DNA antisense oligonucleotides alleviates emotional deficits in mdx52 mice. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 32, 173–188 (2023).

Helleringer, R. et al. Cerebellar synapse properties and cerebellum-dependent motor and non-motor performance in Dp71-null mice. DMM Disease Models and Mechanisms 11, 10.1242/dmm.033258 (2018).

Miranda, R. et al. Altered social behavior and ultrasonic communication in the dystrophin-deficient mdx mouse model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Mol. Autism 6, 10.1186/s13229-015-0053-9 (2015).

Daoud, F. et al. Role of mental retardation-associated dystrophin-gene product dp71 in excitatory synapse organization, synaptic plasticity and behavioral functions. PLoS One 4, e6574 (2009).

Chaussenot, R. et al. Cognitive dysfunction in the dystrophin-deficient mouse model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy: A reappraisal from sensory to executive processes. Neurobiol. Learn Mem. 124, 111–122 (2015).

Tetorou, K. Created in BioRender. https://BioRender.com/u06g263 (2024).

Michael, N. & Karen, A. Dystrophin Dp71 and the Neuropathophysiology of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. Mol Neurobiol. 57, 1748–1767 (2020).

Tetorou, K. Created in BioRender. https://BioRender.com/w86l794 (2024).

Tetorou, K. Created in BioRender. https://BioRender.com/y58j574 (2024).

Tetorou, K. Created in BioRender. https://BioRender.com/q88i529 (2024).

Tetorou, K. Created in BioRender. https://BioRender.com/b76v061 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The partial support of EUH2020 grant 83245 Brain Involvement iN Dystrophinopathies to all the authors is gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors, C.V., Y.A., E.M., J.H., K.T., A.G., and F.M. contributed to the literature search and wrote the article. Y.A., C.V., A.G. and K.T. prepared the figures.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare the following competing interests. F.M. has received grants, speaker, and consultancy honoraria from Sarepta Therapeutics, Roche, PTC Therapeutics, Dyne Therapeutics, and Pfizer. E.M. has received grants, speaker, and consultancy honoraria from Sarepta Therapeutics, Roche, Italfarmaco. Y.A. has received grants and consultancy honoraria from Nippon Shinyaku Co., Ltd. and grants from Shionogi & Co., Ltd. C.V., J.H., K.T. and A.G., declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Dongsheng Duan who co-reviewed with Matthew Burke; and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Vaillend, C., Aoki, Y., Mercuri, E. et al. Duchenne muscular dystrophy: recent insights in brain related comorbidities. Nat Commun 16, 1298 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56644-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56644-w

This article is cited by

-

The rise of rat models for Duchenne muscular dystrophy and therapeutic evaluations

Skeletal Muscle (2025)

-

Conditional Dmd ablation in muscle and brain causes profound effects on muscle function and neurobehavior

Communications Biology (2025)

-

Deficient Astrocyte Homeostatic Support Contributes to Brain Impairment in Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy

Neurochemical Research (2025)

-

Brain dystrophinopathies and cognitive impairment: Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and therapies

Journal of Biosciences (2025)

-

Identification of key regulators in Duchenne muscular dystrophy combinatorial network: a systems biology approach

Network Modeling Analysis in Health Informatics and Bioinformatics (2025)