Abstract

Cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM), X-ray crystallography, and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) contribute structural data that are interchangeable, cross-verifiable, and visualizable on common platforms, making them powerful tools for our understanding of protein structures. Unfortunately, atomic force microscopy (AFM) has so far failed to interface with these structural biology methods, despite the recent development of localization AFM (LAFM) that allows extracting high-resolution structural information from AFM data. Here, we build on LAFM and develop a pipeline that transforms AFM data into 3D-density files (.afm) that are readable by programs commonly used to visualize, analyze, and interpret structural data. We show that 3D-LAFM densities can serve as force fields to steer molecular dynamics flexible fitting (MDFF) to obtain structural models of previously unresolved states based on AFM observations in close-to-native environment. Besides, the .afm format enables direct 3D or 2D visualization and analysis of conventional AFM images. We anticipate that the file format will find wide usage and embed AFM in the repertoire of methods routinely used by the structural biology community, allowing AFM researchers to deposit data in repositories in a format that allows comparison and cross-verification with data from other techniques.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM)1, X-ray crystallography2, and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR)3 solve three-dimensional (3D) structures of biomolecules, i.e., proteins, DNA, RNA, and mixed complexes thereof, at high-resolution through averaging of thousands of molecules. These 3D structures, deposited as density in EM Data Bank (EMDB)4 and as atomic coordinate models in Protein Data Bank (PDB)5 files, form the basis of our understanding of biomolecular structure and often provide insights into the chemistry of biomolecular function. In contrast, atomic force microscopy (AFM)6 is a surface technique and therefore is unlikely to ever provide a complete 3D structure independently, without an integrative and cross-methodology approach.

However, AFM is unique in providing structural information of single molecules under close-to-physiological and dynamic conditions and has several strengths compared to other structural biology techniques. As an advantage, to study biomolecules or cells, AFM operates in physiological buffers and at ambient temperature and pressure. For the study of membrane proteins, e.g., channels, transporters, and receptors, these molecules can be reconstituted in a lipid membrane of controlled composition7. Thus, AFM allows the structural analysis of proteins under conditions arguably more native than the conditions necessary for X-ray diffraction, i.e., proteins in 3D-crystals, or cryo-EM, i.e., proteins in an ~50 nm thin liquid layer imaged at liquid nitrogen temperature (77 K). In addition, for the study of membrane proteins, the molecules are typically analyzed in environments less-native than a reconstituted membrane, namely in micelles, bicelles, or nanodiscs; though recently, membrane protein structures were solved in vesicles by cryo-EM8. Another advantage of AFM is its more recent speed-enhanced version, termed high-speed atomic force microscopy (HS-AFM)9. The term HS-AFM typically refers to image acquisition speeds between 1 and 100 frames per second. These devices have already provided invaluable dynamic information on conformational changes10, conformational transition pathways11,12, and rare conformational states of proteins13. In addition, HS-AFM operates with short cantilevers that have low hydrodynamic drag and large angular change when deflected14, as well as faster feedback operation15, and is, therefore, substantially more sensitive and less invasive than conventional AFM.

As briefly mentioned above, a disadvantage of AFM and HS-AFM data is that it is restricted to surface contouring and thus provides only pseudo-three-dimensional (pseudo-3D) information. While true 3D data associates a density value to all voxels used to describe a structure in x,y,z-space as data from X-ray diffraction and cryo-EM imaging, AFM only associates a single h-value (height) to each x,y-position, where the tip interacted with the sample surface. Another disadvantage of AFM and HS-AFM is that molecules have to be surface-adsorbed in order to be analyzed. This is, however, not as limiting as one may think, especially for a 2-dimensional (2D) membrane with inserted membrane proteins that naturally only expose their two hydrophilic faces to the liquid environment and when using atomically flat mica as a sample surface. On a freshly cleaved mica surface, i.e., a clean and atomic layer, it has repeatedly been shown that channels and transporters are free to undergo conformational changes12,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24, and diffuse freely with diffusion coefficients of up to ~0.7 µm2/s (7), especially membrane proteins that do not protrude strongly from the membrane.

Finally, AFM and HS-AFM topographic data are convoluted by the tip shape, enlarging and convoluting the protein topographies with the AFM tip radius. This limitation was overcome by the introduction of localization atomic force microscopy (LAFM), a super-resolution method that extracts topographic peak positions from individual particle observations and merges them into a topography probability map that can reach a quasi-atomic resolution on protein surfaces25. The fact that only topographic peaks are merged restricts the data content to true tip-sample interactions only, while eliminating data that is prone to emerge from tip convolution. Thus, LAFM is poised to become a standard AFM data processing method to produce data that can interface with other structural biology techniques.

X-ray diffraction and cryo-EM result in electron- or nuclear-density maps, respectively. Subsequently, the known amino acid sequence chain of the protein under investigation is built into these density maps so as to best fit the density while respecting the angular constraints of peptide bonds and their interactions in 3D space26. Thus, X-ray diffraction and cryo-EM data provide the basis for building atomic models of protein structures. AFM cannot provide such constraints, and will likely never be able to provide data that allows building a protein structural model because the volumetric information is missing, but it can provide unique information about the conformational transitions occurring on the surface of a protein along the timeline of a protein in action10. As we have recently shown, HS-AFM allows single-molecule structural biology, providing multiple structures that can be associated with the states of a molecule at work. Thus, the data is not only acquired in physiological buffers and at ambient temperature and pressure, but it can also provide the spatial and temporal constraints to dock, model, and order atomic models, to result in real movies of proteins in action.

However, so far, AFM data has been published as figure panel images only and remained quite anecdotal because there was no generally usable data nor file format output (such as the EMDB or PDB files) that could be exchanged with, analyzed, cross-validated, or used as input by other techniques. To achieve this goal and establish AFM as a complementary tool for dynamic structural biology, we need to extract data that is of high enough resolution to inform and be comparable to data from other methods, and that is readily readable and accessible in most common structural biology software. Here, we developed a pipeline that transforms AFM data into 3D probability density maps that are compatible with data from other structural biology methods. To achieve this, we automatized and unbiased LAFM peak detection and 3D-space merging, resulting in a 3D surface probability density map encoded in a ‘.afm’ file that is structured like the corresponding density maps from X-ray diffraction and cryo-EM and can be directly read (drag-and-drop) in structural biology software (e.g., Chimera27).

Modeling atomic structures into AFM topographs, to acquire an atomistic model of what AFM images in buffer solution and at ambient temperature and pressure reveal, has been done since the very first sub-molecular resolution AFM images of OmpF in 2D-crystals28. Later, cross-correlation searches of atomic structure surface representations, for the determination of the positional and rotational degrees of freedom of the molecules in AFM images of native photosynthetic membranes, were used to build atomic models of super-complexes29. This approach was extended for further structural insights using 2D image comparisons between AFM images and pseudo-AFM images computed from either PDB structures, simulated structures, or 3D densities generated from the PDB structures using the Gaussian mixture model30,31,32, and image correlation was also used as a force field to drive simulations33,34,35,36. Though limited, these applications demonstrate that an integrative approach employing a combination of AFM, structure integration, and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations can advance biophysics and structural biology.

Here, we transform AFM data into 3D probability densities that relate the spatial free energy distribution to the physical (topographical) boundaries for the underlying protein structure and dynamics by the Boltzmann relationship and encode them in ‘.afm’ files. We use the ‘.afm’ 3D-density map files to generate force fields for MD flexible fitting (MDFF)37, taking advantage of the fundamental principle of MDFF where the gradient of the density is related to force. This strategy allows us to apply a physically meaningful bias to the input structure, steering X-ray crystallography, and cryo-EM structures of a protein to obtain models that reflect the observed structural features in the AFM experiment. The data treatment pipeline and file format allow AFM data to be deposited, opened, compared, and analyzed by any researcher in common software, bringing AFM into the toolbox of structural biology.

Results

Construction and evaluation of 3D-LAFM detections

The recent development of LAFM (Methods) allowed us to break resolution limitations set by pixel sampling and tip convolution25. Image expansion permitted translational and rotational fine alignment of particles and extraction of LAFM detections with great spatial precision, which were then merged into high-resolution LAFM maps25. The canonical LAFM algorithm is capable of resolving fine structural details on the molecular surfaces of proteins25, but direct comparisons of LAFM maps to data from other structural biology methods are impractical, primarily because LAFM maps were 2D images while other structural methods generate 3D density or coordinate files. Therefore, it is of utmost importance to transform LAFM maps (and AFM data in general) into a 3D format to propose AFM as a complementary tool for dynamic structural biology. To this end, we extracted LAFM detections through local image expansion38, and subsequently aligned and allocated these detections into a 3D-volume space (Fig. 1a, Supplementary Fig. 1, Methods). Here, we used annexin V (A5), a peripheral membrane protein that assembles into membrane-bound 2D-lattices and has been widely studied using HS-AFM39,40,41, as an example dataset (2.5 Å/pixel).

a LAFM detections extracted from each particle (bottom, unaligned coordinates) were translationally and rotationally revised according to the results of the global particle fine alignment in a parallel pipeline (top, alignment information), giving aligned LAFM detections. b Transformation of the aligned LAFM detections (middle) extracted from the raw AFM particles (left, n particles) to the 3D-LAFM detection stack (right). The raw AFM frames and the aligned LAFM detections (before merging) are x-y-n data recording height h (left schematic). After transformation, the 3D-LAFM detection stack is an i-j-k (x-y-h) volume space recording the count of aligned LAFM detections (right schematic). Yellow dots: Three local maxima with different h-values (low, medium, and high) from the first particle in the raw AFM frames, and their corresponding locations in the aligned LAFM detections and the 3D-LAFM detection stack. c Top-view (top, i-j plane) and a side-view (bottom, j-k plane) projections of the 3D-LAFM detection stack (voxels with 0 detections are represented in white, while voxels with 1, 2, 3, etc, detections are represented by increasingly darker gray values). d Fourier Shell Correlation (FSC) analysis of masked 3D-LAFM detection half-stacks (Methods). Inset: Masked 3D-LAFM detection stack (voxel size dv = 0.3 Å/voxel). e FSC analyses of masked 3D-LAFM detection half-stacks of various voxel sizes. Red dashed lines: half-bit threshold.

The AFM particle stack, the initial dataset from which aligned LAFM detections were extracted, is a stack of n particles containing structural data as x,y-coordinates, each informing about the height, h, of the sample surface. Thus, the particle stack represents an x-y-n matrix recording h (Fig. 1b, raw AFM frames). The local extraction and merging of LAFM detections from n particles retained the height values of each detection, at coordinates x’,y’ with sub-pixel spatial precision (Fig. 1b, aligned LAFM detections, Methods). The 3D-LAFM volume space, instead, is an i-j-k matrix (corresponding to x-y-h axes) merging the count of LAFM detections. This requires voxelization of the spatial x’, y’, and h values. Consequently, we defined a voxel size dv and allocated the aligned LAFM detections into the corresponding voxels in the 3D-LAFM volume space (Fig. 1b, 3D-LAFM detection stack, see Methods). As expected, the LAFM detections localized mostly in voxels characterizing the A5 molecular surface (Fig. 1c, dark voxels), whereas other voxels had 0 or 1 detections. No LAFM detections were excluded by a user-defined, arbitrary, prominence threshold; in contrast, all detections were merged into the 3D-space (1.1 × 105 detections in the A5 example). We reason that local maxima that resulted from imaging noise would be sparsely and equally distributed in the 3D space and, therefore, would not influence the further density-weighted treatment of the data.

To evaluate the distribution of the aligned LAFM detections in 3D space, we allocated them into two independent half-stacks (each had ~5.3 × 104 detections), then masked the voxels characterizing the A5 molecular surface (Supplementary Fig. 2, Methods), and calculated the Fourier shell correlation (FSC) of the two half-stacks (Fig. 1d). Since distinct procedures were applied to determine the k-value (height dimension) and the i,j-values (lateral dimensions) of 3D-LAFM detections, we interpret the FSC signal as an objective evaluation of the spatial distribution of 3D-LAFM detection data and not as an isotropic ‘spatial resolution’ as is the case for canonical volume data42. Therefore, we use, instead of ‘spatial resolution’, the term ‘half-bit wavelength’, λhb, for further discussion of the 3D-LAFM data quality43.

The two 3D-LAFM detection half-stacks had a λhb of ~1.1 Å while the voxel size was dv = 0.3 Å/voxel (Fig. 1c, d). We found that the data quality increased with finer voxelization, i.e., decreasing voxel size dv, of the aligned LAFM detections in 3D space, as expected. λhb saturated at ~0.3 Å/voxel (Fig. 1e, Supplementary Fig. 3a), before being limited by the local expansion LAFM detection extraction (0.167 Å/pixel, Methods). Therefore, a 15× bicubic expansion coefficient (2.5 Å/pixel to 0.167 Å/pixel) was reasonable for the local expansion LAFM detection extraction for the A5 example data. In addition, the 3D-LAFM detection stack quality also depended on the total count of detections, i.e., the number of raw AFM data particles n that were integrated into the process, as λhb increased as more detections were pooled and then saturated at ~2 × 104 detections (~6 × 104 considering the three-fold symmetry of the A5 trimer) (Supplementary Fig. 3b).

Transformation of 3D-LAFM detections to density map

In localization-based super-resolution techniques, including LAFM, a point spread function or density function informs the likelihood of an observable, e.g., a fluorophore in fluorescence microscopy44,45 or a peak topographic feature in AFM25, to be detected at its location. To transform these detections (Fig. 2a) into a spatial density distribution (Fig. 2b), we must apply a probability function that characterizes the localization precision of the tip-sample interaction coordinates. In the canonical LAFM algorithm, a 2D Gaussian density function, usually with σ = 1.4 Å, was assigned to each detection, accounting for the solvent-accessible surface of an atom from which the tip-sample interaction on the protein surface originated25.

a, b 2D slices of the 3D-LAFM detection stack (a) (see Fig. 1b, right, Supplementary Movie 1) and the 3D-LAFM density map (b) (Supplementary Movie 2). Selected i-j planes (blue) and j-k planes (red) are displayed. Yellow dots: Positions of the three example local maxima with different h-values (low, medium, and high) from the first particle in the raw AFM frame (see Fig. 1b, yellow dots). Left: Schematics of the i-j and j-k plane 2D slices. c Cartoon of A5-monomer crystal structure (PDB 1AVR) from the liquid-facing side (top) and in a side view (bottom). d Surface presentation of A5-trimer from the liquid-facing side. Dashed line: A5-monomer. e 3D-LAFM density map in Chimera, viewed in top-view (i-j plane) projection. Grayscale: probability density. f High-density surface (top-view) presentation of the 3D-LAFM density map. False-color scale represents height values, similar to the surface presentation of the structure in (d). g Comparison of the A5-monomer liquid-facing surface in the crystal structure (left), 3D-LAFM density map (middle), and the 3D-LAFM high-density surface (right). h Fourier Shell Correlation (FSC) analysis of masked 3D-LAFM half-density maps. Arrowheads in c–f: Annexin-repeats I, II, III, and IV.

To transform detection coordinates into density in the 3D-LAFM pipeline, we applied a 3D Gaussian density function to each aligned LAFM detection in the 3D-LAFM detection stack, using the computationally derived σ value equivalent to λhb determined from the FSC analysis of the 3D-LAFM detection half-stacks. This step transforms a 3D-LAFM detection stack (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Movie 1) into a 3D-LAFM density map (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Movie 2), and thus concludes the objective 3D-LAFM pipeline from raw AFM images to 3D-density data (Fig. 1b to Fig. 2a, b, follow the yellow dots showing the trajectories of local maxima with low, middle, and high h-values in the first particle in the raw AFM frames). Slices through the A5 3D-density map highlight the high-resolution features that are resolved on the protein surface at the various levels of protrusion height (Fig. 2b, from low (right) to high (left) topographical features).

The A5 monomer consists of four domains, aka annexin-repeats (Fig. 2c, I, II, III, IV), of which repeats I, III, and IV protrude further and are well exposed to AFM contouring (once A5 is trimerized and membrane-bound, Fig. 2d)46. Substantial height differences were observed in the 3D-LAFM density map of the A5-trimers where repeats I, III, and IV are located, while repeat II gave only a minor topography signal (Fig. 2b–e, arrowheads I, II, III, IV), reported by a counter-clockwise topographical height decrease, i.e., the height of repeat III > IV > I in HS-AFM data. Precise height differences, Δh, between the repeats could be measured from the i-j planes in the 3D-LAFM density map (Fig. 2b, blue). Considering the voxels with the highest density values, i.e., the most likely 3D location of the repeat of interest, we found that repeat III topped IV by a Δh of ~2 Å while repeat IV topped I by a Δh of ~1 Å. Similarly, the relative distance, Δd, between the repeat protrusions can be measured with high confidence in the j-k (red, for Δdy measurement) and i-k planes (for Δdx measurement), such that repeats III and IV had a Δd of ~26–27 Å and repeats IV and I had Δd of ~24–25 Å. These measurements provide insightful information about the general structural features of the molecules in the HS-AFM experiments under close-to-physiological conditions and showcase the potential of 3D-LAFM to analyze Angstrom-scale conformational changes in enzymatically active proteins.

To make 3D-LAFM density map data interpretable and comparable to results from other structural biology techniques, we compile the 3D-LAFM density map into a ‘.afm’ file which has a file structure similar to the MRC2014 file format that is commonly used for cryo-EM density maps47 (Table 1, metadata code for 3D-LAFM density map: AFM1, Methods). Thus, the ‘.afm’ file format is fully compatible with general structural biology software and can be opened using drag-and-drop in e.g. Chimera27 (Fig. 2e). As a consequence, the 3D-LAFM density map is generally compatible with the built-in tools in Chimera for in-depth analysis of the AFM data, which will be discussed later. For 2D visualization of the 3D probability density (for print panels and convenience for the human eye), we developed a pipeline to generate a high-density surface presentation of the 3D-LAFM density map (Fig. 2f, Methods), in which height is assigned an RGB color according to the LAFM false-color scale25. This is useful for the generation of figure panels to communicate the characteristic topography information of AFM. The topographical features of the membrane-bound A5-trimer in the AFM experiment under close-to-physiological conditions were comparable to the A5 X-ray structure solved from proteins in less-physiological 3D-crystal lattices46 (Fig. 2g, compare X-ray structure (left) and 3D-LAFM (right two panels)): A5 has overall a concave shape in both methods (Fig. 2c, bottom). In addition, the fine structural features along the backbone on the protein surface, i.e., the surface protruding residues, were resolved in the 3D-LAFM density (Fig. 2g, compare X-ray structure (left) and 3D-LAFM (right two panels)). Finally, we constructed 3D-LAFM density maps from half datasets for FSC analysis, which revealed a surface λhb of ~1.4 Å for the A5-trimer 3D-LAFM density map.

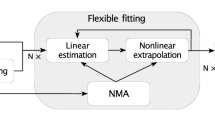

3D-LAFM density as force field for flexible fitting

MDs flexible fitting (MDFF) has been widely used to fit atomic structures into density maps37,48,49,50,51. MDFF allows all-atom MD simulations of a known structure, i.e., atomic coordinates, under an external force field proportional to the gradient of a density map37, e.g., a cryo-EM density map, in addition to classic MD force fields characterizing the physical laws, UMD, and the secondary structure restraints, USS, e.g., CHARMM force fields52. Although only providing surface information, the high-resolution 3D-LAFM density maps (λhb ~ 1–2 Å−1) can serve as an MDFF force field, UAFM, to steer MD simulations of an atomic structure solved by another method, towards the most probable conformation that matches the topographical features obtained in AFM experiments under close-to-physiological conditions (Fig. 3a, Methods).

a 3D-LAFM density force field UAFM for A5. An i-j plane cross-section of the force field is colored according to the local energy density (red to blue: Low to high energy level), the gradient of which is proportional to the force field (black arrows). Inset: surface representation of the 3D-LAFM density map where the red dashed box indicates the cross-section site. b MDFF trajectory of A5 (Supplementary Movie 3). Cyan: Selected frames displayed in a side view. Gray: 3D-LAFM density map. Selected frames: t = 0 ns (initial PDB structure), t ~ 0.5 ns, t ~ 10 ns and t ~ 20 ns (md cycle 1), t ~ 40 ns (md cycle 2), and t ~ 60 ns (md cycle 3, end of MDFF, Methods). c–e Evaluation of the A5 MDFF trajectory. Time-evolution of internal energy (E) (c), root-mean-squared deviation (rmsd) to the initial structure (d), and normalized correlation between structure and density map (e) during MDFF (Methods). Red dashed lines: ends of each MDFF cycle. f Superimposed structures of initial model (purple, PDB 1AVR, t = 0 ns) and final model (scarlet, t ~ 60 ns). A5-monomer in top view (top) and from a side view (bottom). g Time-evolution of annexin-repeat movements during the MDFF trajectory. Left and middle: Height of repeats I (blue), III (green), and IV (yellow) relative to repeat II (black arrowheads in (f) for annexin-repeat assignment). The repeat height was measured as the center-of-mass of either all repeat atoms (left), characterizing the repeat rigid body, or all atoms in the top 20 Å of the liquid-facing side (middle), characterizing the repeat surfaces. Right: Height differences (Mean ± SD) of repeat III relative to IV (clear) as well as repeat IV relative to I (striped) in the initial structure (PDB 1AVR), near the end of cycle 1 (md1), cycle 2 (md2), cycle 3 (md3), and the 3D-LAFM density map (afm) (Methods). For each measurement, 21 structures, giving n = 63 protomers, were selected from each MD cycle (md1, md2, and md3).

The AFM force field, UAFM, contains both an active fraction where the force is proportional to the gradient of the 3D-LAFM density map (Fig. 3a), covering the molecular surface as an ~20 Å thick density cushion in the A5 example (Fig. 3b, t = 0 ns, gray), as well as an inactive fraction in the space covering the rest of the molecule below the 3D-LAFM density map filled with a background-matching density value (Methods). Using this force field, we ran a ~60 ns MDFF simulation, consisting of three ~20 ns simulation cycles at 300 K, interspersed by an energy minimization step (Fig. 3b–e, Supplementary Movie 3, Methods). To improve convergence of the MDFF simulations and avoid overfitting (Methods), we applied symmetry restraint in all three simulation cycles so that the subunits evolve towards the same conformation (as the 3D-LAFM map is also n-fold symmetric), divided the structured regions into individual domains and applied domain restraint in the first two simulation cycles, and, in the final MDFF cycle, allowed the structure to freely explore its local energy landscape free of the domain restraint to adopt a low energy conformation.

We observed, that the rigid body of the A5 structure moved rapidly into the 3D-LAFM density map within the first ~0.5 ns of the simulation (Fig. 3b, compare t = 0 ns and t = 0.5 ns), and reached an equilibrium conformation after ~10 ns (Fig. 3b, t = 10 ns). This was reported by the internal energy (E) that relaxed to ~1.55 × 103 kcal/mol (Fig. 3c), the root-mean-squared distance (rmsd) to the initial structure that plateaued at ~9 Å (Fig. 3d), and the normalized correlation of the structure to the density map that flattened at ~0.58 (Fig. 3e), whereas the initial roughly fitted model had a correlation value of ~0.3. Large annexin-repeat movements were completed in the first MDFF cycle (Fig. 3b, t = 20 ns), while the additional MDFF cycles involved local structural adjustment (Fig. 3b), further lowering the internal energy to ~1.48 × 103 kcal/mol, and improving the correlation coefficient to ~0.61 (Fig. 3c, e, t ~ 40 ns and t ~ 60 ns). It is worth noting that the AFM tip interaction with the sample surface may not always resolve flexible loops on the molecular surface, which is why we focused our analysis of 3D-LAFM MDFF results predominantly on the structured regions.

Compared to the initial crystal structure (Fig. 3f, purple), the final model from 3D-LAFM MDFF (Fig. 3f, scarlet) preserved the overall tertiary annexin-repeats structure, while rigid-body movements of repeats I and III were evident. To quantify the movements, we tracked the relative annexin-repeat height differences Δh over the simulation trajectory (Fig. 3g). We restricted this analysis to all the atoms in regions with secondary structure in the annexin-repeats, because the 3D-LAFM density that served as force field might comprise tip-sample interaction deformations in the flexible loops. Using repeat II (closest to the membrane) as a reference point, we found that repeats I, III, and IV all moved closer to the membrane during MDFF, to a final Δh(III–II) ~ 4.4 Å, Δh(IV–II) ~ 2.5 Å, and Δh(I–II) ~ 2.5 Å, respectively (Fig. 3g, left). Alternatively, since the 3D-LAFM density map covered ~20 Å of the A5 liquid-facing surface, we estimated Δh using all surface atoms within this range (Fig. 3g, middle), and found a Δh(III–II) ~ 4.9 Å, Δh(IV–II) ~ 2.4 Å, and Δh(I–II) ~ 1.4 Å, respectively.

Excitingly, the MDFF models captured essential structural features in the 3D-LAFM density map, where repeats III and IV shared a Δh of ~2.8 Å and repeats I and IV shared a Δh of ~0.8 Å (Fig. 3g, right, Fig. 2e). In contrast, a Δh of ~5.1 Å between repeats III and IV as well as a Δh of ~1.7 Å between repeats I and IV were estimated from the A5 crystal structure (Fig. 3g, right). Therefore, using the 3D-LAFM MDFF strategy, we obtained the most probable conformation underlying the AFM observation under close-to-physiological conditions. As detected by the Δh values, this A5 conformation adopts an overall flatter annexin-repeat arrangement that is less concave than the X-ray structure. We reason that, unlike the X-ray crystal where A5 is not membrane-bound, and thus no force is acting on the structure, the membrane to which A5 is attached in the HS-AFM experiments may exert a flattening force on the A5 molecules. Therefore a slightly flatter A5 structure, as compared to the X-ray structure, when A5 is membrane surface-associated, appears as a probable structure refinement under native conditions.

3D-LAFM MDFF conformational changes in a transporter

HS-AFM has recently allowed single-molecule structural biology, in which the conformational changes of a single GltPh membrane transporter molecule were tracked under close-to-physiological conditions with high spatio-temporal resolution10. GltPh comprises three functionally independent transport domains associated with a central scaffold- or trimerization domain (Fig. 4a, top)53. Related to the release of the transport substrate on the intracellular side, large transport domain rearrangements between the inward-facing state (IFS) closed, IFSclosed, and open, IFSopen, conformations were reported in structural studies using X-ray crystallography54,55,56, cryo-EM57, and HS-AFM10 where IFSopen adopts a conformation with a more tilted (thus opened) transport domain than IFSclosed (Fig. 4a, bottom). In contrast, the trimerization domain is essentially static in the IFSopen–IFSclosed transition. In the HS-AFM single-molecule analysis, ~1000 protomer observations (POs) were obtained from an HS-AFM movie of an individual membrane-reconstituted GltPh from the cytoplasmic side in apo condition, and subsequently sorted using principal component analysis (PCA) into outward-facing, OFS, IFSopen, and IFSclosed conformations10. Thus, calculating LAFM maps of these states and combining them with conformation-time traces of individual transport domains allowed HS-AFM single-molecule structural biology reporting about the structural interconversions of a single molecule over time10.

a PDB structure of GltPh IFS (PDB 6X12). A GltPh trimer consists of three functionally independent transport domains (green) and a central trimerization domain (blue). Top: GltPh trimer viewed from the cytoplasmic side (left) and GltPh monomer displayed in side view (right). Bottom: Cartoon representation of GltPh monomer, where transport domain tilt change with respect to the z-axis is a characteristic distinguishing IFSopen (left) and IFSclosed (right) conformations. b Structures (left, surface representation from the cytoplasmic side) of IFSopen (top, PDB 6X12) and IFSclosed (bottom, PDB 4P19) GltPh, and high-density 3D-LAFM surfaces (right). 3D-LAFM data were modified from ref. 10. c CVs tracked during MDFF: Top left: angle between transport domain and z-axis (angle θ). Bottom left: Height difference between transport and trimerization domains on the cytoplasmic side (Δz). Right: Angle between trimerization domain and z-axis (angle φ). d–i Analyses of ‘trans-fitting’ 3D-LAFM MDFF trajectories: d, g: UAFM–IFSo used to steer IFSc-apo-X-ray. e, h: UAFM–IFSo used to steer IFSc-trsp-EM, and f, i: UAFM–IFSc used to steer IFSo-apo-EM (Methods). d–f Gray: UAFM force fields derived from 3D-LAFM density maps. Scarlet: MDFF structural models displayed from the cytoplasmic side (top) and in a side view (bottom). Left: Initial model (t = 0 ns). Right: Final model (t ~ 60 ns). g–i 1st, 2nd, and 3rd panel: CVs φ, θ, Δz, where the gray lines represent the evolution of the three individual transporter domains (protomers 1, 2, and 3). Reference structures: IFSo-apo-EM (red dashed line), IFSc-apo-X-ray (black dashed line), and IFSc-trsp-EM (blue dashed line). 4th panel: rmsd of the MDFF structures to the initial PDB structure (black) and the ‘target’ structure (gray). The ‘cis-fitting’ 3D-LAFM MDFF trajectories are reported in Supplementary Fig. 5.

Here, taking advantage of the PO-sorting results, we constructed 3D-LAFM density maps of IFSclosed and IFSopen (Fig. 4b, Supplementary Fig. 4, Supplementary Movies 4 and 5) and used them to generate force fields (UAFM–IFSc and UAFM–IFSo) to steer 3D-LAFM MDFF (Fig. 4c–f, Supplementary Fig. 5). To obtain the most probable atomic models of the states determined in the HS-AFM experiment, we used PDB structures resolved in apo condition as the initial MDFF input, namely an IFSopen cryo-EM structure (PDBIFSo–apo–EM, PDB 6X12) and an IFSclosed crystal structure (PDBIFSc–apo–Xray, PDB 4P19). To account for the different methods used in the structure determination, an additional IFSclosed cryo-EM structure was used (PDBIFSc–trsp–EM, PDB 6X15), though it was acquired in the presence of Na+ and Asp (transport condition), unlike the AFM experiments. To assess the transport domain movement, we defined three collective variables (CVs) to characterize the structure and measure the changes of the transport domain in the MDFF trajectories (as well as in the PDB structures), including: (1) The angle between the trimerization domain and the z-axis (angle φ). (2) The angle between the transport domain and the z-axis (angle θ). And, (3) the height difference between the transport- and trimerization domain from the cytoplasmic side (Δz) (Fig. 4c).

As control, we started the MDFF setup with the UAFM-matching PDB structures—the ‘cis-fitting’ strategy—where UAFM–IFSc was used as force field to steer PDBIFSc–apo–Xray and PDBIFSc–trsp–EM in MDFF (Supplementary Fig. 5a, b), and UAFM–IFSo was used as force field to steer PDBIFSo–apo–EM in MDFF (Supplementary Fig. 5c). After ~60 ns simulations, the ‘cis-fitting’ strategy led to an IFSopen structural model from UAFM–IFSo with CV measurements matching PDBIFSo–apo–EM. Interestingly, UAFM–IFSc generated an IFSclosed structural model that was conformationally more akin to PDBIFSc–trsp–EM than PDBIFSc–apo–Xray, indicating that the HS-AFM IFSclosed 3D-LAFM data was conformationally more similar to the closed conformation resolved by cryo-EM, where GltPh was reconstituted into a membrane nanodiscs in transport condition, than to the X-ray crystallography structure from GltPh in 3D-crystals in the absence of membrane yet in apo condition.

Although the ‘cis-fitting’ MDFF strategy allowed us to obtain structural models of both IFSopen and IFSclosed GltPh that incorporated the AFM structural features under close-to-physiological conditions, the approach requires prior knowledge about which initial PDB structure best matches the AFM force fields. Therefore, as the essential MDFF simulation, we engaged in the ‘trans-fitting’ strategy—intentionally starting with the ‘wrong’ PDB structures (Fig. 4d–i)—where UAFM–IFSo was used as a force field to steer PDBIFSc–apo–Xray (Fig. 4d, g, Supplementary Movie 6) and PDBIFSc–trsp–EM (Fig. 4e, h, Supplementary Movie 7) in MDFF; and UAFM–IFSc was used as a force field to steer PDBIFSo–apo–EM (Fig. 4f, i, Supplementary Movie 8). Excitingly, the ‘trans-fitting’ strategy yielded similar structural models as obtained using the ‘cis-fitting’ strategy, as evaluated from the CV measurements in the final ~20 ns of the simulation trajectories, meaning that closed structures opened and the open structure closed their intracellular gate (compare Fig. 4g, h to Supplementary Fig. 5a, b, and compare Fig. 4i to Supplementary Fig. 5c). An expected transport domain opening, with a θ increase of ~12° and ~6° and a Δz reduction of ~7 Å and ~5 Å, was observed at t ~ 5 ns in the MDFF trajectories using UAFM–IFSo as force field, indicative of a transition from PDBIFSc–apo–Xray (Fig. 4d) and PDBIFSc–trsp–EM (Fig. 4e) towards PDBIFSo–apo–EM. Similarly, an expected transport domain closing, with a θ reduction of ~8° and a Δz increase of ~4 Å, was evident in the MDFF trajectories using UAFM–IFSc as force field (Fig. 4f). Besides, the rmsd measurements of the ‘trans-fitting’ trajectories (Fig. 4g–1, right) further corroborated that structural models analogous to PDBIFSo–apo–EM and PDBIFSc–trsp–EM were obtained from MDFFs with UAFM–IFSo and UAFM–IFSc as force fields, respectively. Hence, the ‘cis-fitting’ and ‘trans-fitting’ MDFF simulation runs demonstrated the feasibility of using 3D-LAFM density map to generate force fields to steer a structure into another meaningful conformation.

Structural analysis of 3D-LAFM MDFF and experimental structures

The converging outcomes of the ‘cis-fitting’ and ‘trans-fitting’ strategies encouraged us to further explore the power of 3D-LAFM MDFF using an objective ‘blind-fitting’ strategy: Indeed, in addition to IFSclosed and IFSopen, we discovered a kinetically locked state in our recent HS-AFM single-molecule study, which we termed IFSopen1 (since its 3D-LAFM map resembled more IFSopen than IFSclosed) that has no structural correspondent in cryo-EM yet (Supplementary Movie 9). Thus, in the ‘blind-fitting’ approach, we used all three input structures (PDBIFSo–apo–EM, PDBIFSc–apo–Xray, and PDBIFSc–trsp–EM) and steered them in MDFF simulations using UAFM–IFSo, UAFM–IFSc, and the uncharted UAFM–IFSo1 that is so far only described by AFM (Methods).

For a comprehensive analysis of the 3D-LAFM MDFF results, we inspected the models from the last 20 ns of all MD trajectories (MDIFSo–apo–AFM, MDIFSc–apo–AFM, MDIFSo1–apo–AFM) starting from any of the experimental structures (PDBIFSo–apo–EM, PDBIFSc–apo–Xray, and PDBIFSc–trsp–EM), as well as these original experimental PDB structures (Fig. 5, Supplementary Fig. 6, n = 1116 protomers, Methods). We then created a CV (Fig. 4c) dataset from all structures, an 1116 × 3 matrix (Methods), and performed PCA on this matrix (Fig. 5a, Supplementary Fig. 6a). As expected, the MDFF results clustered in the pc1-pc2 space, where MDIFSo–apo–AFM was close to PDBIFSo–apo–EM and MDIFSc–apo–AFM was close to PDBIFSc–trsp–EM (quite a bit further away from PDBIFSc–apo–Xray) (Fig. 5a, left). Interestingly, MDIFSo1–apo–AFM structures had a slight overlap with MDIFSo–apo–AFM structures but formed a clear cluster at a nearby location. To evaluate the structural similarity, we defined a similarity score (ss) which is inversely related to the pairwise distances between all structures from each species in the pc1-pc2 space (Fig. 5a, right, Methods). MDIFSo1–apo–AFM had a ss ~ 0.55, ~0.38, and ~0.58 to MDIFSo–apo–AFM, MDIFSc–apo–AFM, and PDBIFSo–apo–EM, respectively, reflecting an overall open transport domain arrangement but in a clearly distinctive conformation for the kinetically inactive IFSopen1 in the transport cycle of GltPh. Overall, these 3D-LAFM MDFF results show that the 3D-LAFM density maps can be used as a force field for MDFF that steers any structure into a coherent conformational cluster, and that the method can produce a model of a so far structurally unknown state, from any starting conformation.

a Principal component analysis (PCA) of MD collective variables (CVs). b Autoencoder (AE) analysis of all-atom coordinates. Left: distributions of GltPh 3D-LAFM MDFF (MD) models and PDB structures in the pc1-pc2 (a) and latent (b) spaces. Right: Heat maps of structural similarity (Methods), where each number is related to the similarity between all data point pairs. MDFF models steered with closed UAFM–IFSc (red), with open UAFM–IFSo (blue), and with kinetically locked UAFM–IFSo1 (green) states. The AFM data was collected in apo condition. IFSc-apo-X-ray (black dimond), IFSc-trsp-EM (black triange), and IFSo-apo-EM (black square) PDB structures were used as initial structures for all 3D-LAFM MDFF simulations (and for final comparison). Overall, the dataset has 1116 protomers from 9 MDFF simulations of 123 protomers (41 trimers) each, plus 9 protomers from the 3 PDB structures. A total of 390 Cα atoms were used, giving 1170 coordinate values for each protomer. The data points are displayed in 3 different shades of red, blue, and green, where the most intense hue corresponds to MDFF from IFSo-apo-EM, the medium hue from IFSc-apo-X-ray, and the lightest hue from IFSc-trsp-EM. Note that independent of the starting structure, all MDFF simulations swarm towards similar 3D-LAFM MDFF models. The detailed structure distribution in the pc1-pc2 and latent spaces for individual simulations is reported in Supplementary Fig. 6.

Complementary to the CVs depicting local structural features, we alternatively built an autoencoder (AE) neural network58 for an unsupervised all-atom analysis (Fig. 5b, Supplementary Fig. 6b) to further analyze the structural changes during the GltPh IFSopen–IFSclosed transition. AE networks are trained to project high-dimension data onto a low-dimension latent space and then use the latent space information to re-generate the high-dimension data with minimal errors. Owing to its efficacy in learning essential features from high-dimension data, AE networks are widely used to analyze MD trajectories59,60,61,62,63,64, using all-atom coordinates as a training dataset to build 2D latent spaces that reflect the most distinctive structural features inherent to the dataset structures. To this end, we trained an AE using the IFS GltPh derived training dataset (1116 × 1170 matrix, for 1116 protomers of 390 Cα atoms, Methods). Remarkably, the MDFF results were distributed in the trained 2D latent space in a comparable pattern to the PCA of CVs (compare Fig. 5a, left with Fig. 5b, left), where MDIFSo–apo–AFM, MDIFSo1–apo–AFM clustered near PDBIFSo–apo–EM, while MDIFSc–apo–AFM clustered near PDBIFSc–apo–Xray and PDBIFSc–trsp–EM. Hence, the AE-based all-atom approach provided an unsupervised and complementary corroboration of the PCA of CVs.

The presented analysis methods allowed direct and quantitative comparisons between structures obtained from AFM experiments (3D-LAFM MDFF structures) as well as between AFM and other structural biology methods. Thus, 3D-LAFM combined with MDFF offers an avenue to refine conformational states, and to describe transition states and conformations observed in the membrane, at ambient temperature and pressure, as well as in a physiological buffer.

Discussion

AFM has long been struggling to be truly complementary and to interface with other structural biology methods, e.g., X-ray crystallography, cyro-EM, and NMR, because AFM did not produce data that was visualizable, analyzable, interpretable, and comparable to commonly used structural biology platforms with data from these other structural biology methods. Here, we built on LAFM and introduced a pipeline to convert AFM single-particle data into 3D density files, i.e., 3D-LAFM density maps, which are encoded in a ‘.afm’ file that has a structure reminiscent of the MRC2014 file format usually used for cryo-EM data (Table 1). The ‘.afm’ file is readable by commonly used structural biology software, e.g., Chimera, allowing direct visualization and interpretation of 3D-LAFM density maps concomitantly with other structural data. Besides, structural features of the protein under investigation can be measured directly in the 3D-LAFM density maps, as showcased here on A5 as well as on IFS GltPh10, and compared with data from other structural methods.

Moreover, we used the 3D-LAFM density maps to generate external force fields, UAFM, for MDFF simulations to steer cryo-EM and crystal structures toward the conformational states observed by HS-AFM. This application makes AFM data complementary to other structural methods and potentially enhances our current structural understanding of proteins. Although AFM data does not allow the construction of complete 3D densities, and as a consequence does not allow the structure determination per se, the 3D-LAFM density maps are structurally informative: Indeed, the use of 3D-LAFM density maps to drive MDFF allowed us to obtain models that reflect the structural features observed in the AFM experiments under close-to-physiological conditions, which complements, yet obligatorily builds on, the structures resolved in less physiological conditions by the other methods. Using ‘cis’ and ‘trans’ conformational 3D-LAFM MDFF, we could quantitatively assess the robustness of the approach. Indeed, the IFS GltPh 3D-LAFM MDFF simulations worked successfully: both the ‘cis-fitting’ strategy, where PDB structures in conformations matching the 3D-LAFM density maps were used as the MDFF input models, and the ‘trans-fitting’ strategy, where PDB structures in conformations different from the 3D-LAFM density maps were intentionally used as the MDFF input models, led to indistinguishable structural models at the end of the simulations. Therefore, a ‘blind-fitting’ strategy could be used for 3D-LAFM MDFF for an unbiased search of structural models that match the 3D-LAFM density maps, enabling the potential discovery of so-far unknown conformations.

The structural models obtained from 3D-LAFM MDFF, as well as between 3D-LAFM MDFF and experimental structures, could be directly and quantitatively compared using PCA of CVs as well as AE neural networks of all-atom coordinates. Thus, the 3D-LAFM pipeline (Supplementary Fig. 7), from raw AFM frames, to 3D-LAFM density maps, and finally to 3D-LAFM MDFF structural models, has the potential to incorporate AFM into the sets of methods routinely employed by the structural biology community. In addition to MDFF, alternative simulation methods such as coarse-grained simulations could potentially be employed, for example, in cases of limited-resolution 3D-LAFM density fitting or for modeling large protein complexes to avoid overfitting or reduce computational demand. AFM experiments and MD simulations are becoming an emergent combination in biophysical studies, allowing for the comparisons of measurables, such as inter-molecular interactions and distances39,65,66.

Furthermore, with an appropriate single-particle sorting strategy such as PCA, as we introduced in the single-molecule structural analysis of GltPh10, multiple structural models could be obtained from AFM and HS-AFM experiments to study the conformational dynamics of a protein at work (Supplementary Fig. 8, Supplementary Note 1), potentially resulting in atomic scale movies of individual proteins in action. In summary, we take a structural biology approach by (1) analyzing AFM data (picking AFM single-particles, classifying the particles in the case of GltPh, and aligning the particles), subsequently (2) building 3D densities from the AFM data, and finally (3) using these 3D densities as physically meaningful force fields to drive PDB structures into unknown conformations.

These datasets could be deposited into suitable repositories in structural biology compatible formats (3D-LAFM densities in ‘.afm’ format, and 3D-LAFM MDFF models in PDB format), for cross-methodology comparison and structural analysis. In analogy to the EMDB where EM densities are deposited, we have initiated the establishment of an AFM Data Bank (AFMDB) with deposits of current “.afm” files (Methods). Besides single-molecule structural data, other AFM data, e.g., the assembly configuration of tens of aquaporins in a membrane7 (Supplementary Fig. 9), or the surface topography and the mechanical properties of a cell (Supplementary Fig. 10), can be encoded in ‘.afm’ files following the ‘AFMx’ code format, facilitating data interpretation, comparison, and cross-validation between AFM and other relevant methods and opening possibilities (Supplementary Note 2). We anticipate that the presented methods will integrate AFM into the toolbox of structural biology and advance our understanding of protein structure and dynamics at a single-molecule level under close-to-physiological conditions.

Methods

HS-AFM sample preparation

The A5 used in the study was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Annexin-V, 33kD from human placenta). GltPh was purified as previously described10,18,57. All lipids (1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DOPC), 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (DOPE) and 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-L-serine (DOPS)) were purchased from Avanti polar lipid. To prepare small unilamellar vesicles (SUVs), for both A5 and GltPh experiments, lipids were first dissolved in chloroform at a ratio of DOPC:DOPS = 3:2 (w:w, for A5) or DOPC:DOPE:DOPS = 8:1:1 (w:w:w, for GltPh), and then dried by a nitrogen flow and kept in a vacuum chamber overnight for further drying. The dried lipid mixture was resuspended into buffer solutions (For A5: 20 mM HEPES at pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, and 2 mM CaCl2. For GltPh: 10 mM Tris-HCl at pH 7.6, 100 mM NaCl, and 10 mM MgCl2), and subsequently sonicated to obtain SUVs.

For A5 experiments39,41, 1.5 μL of diluted SUV (DOPC:DOPS = 3:2, w:w) solution at a lipid concentration of 0.1 mg ml−1 was deposited onto freshly cleaved mica for ~1 min to form supported lipid bilayers, and then rinsed with A5 imaging buffer (20 mM HEPES at pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, and 2 mM CaCl2). During HS-AFM imaging, A5 molecules were added to the HS-AFM fluid chamber and growth of 2D-crystals on preformed membranes could later be observed.

For GltPh reconstitution10, purified GltPh was diluted to a final protein concentration of 0.5 mg ml−1 with the reconstitution buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl at pH 7.6, 100 mM NaCl, and 10 mM MgCl2). SUV solution (DOPC:DOPE:DOPS = 8:1:1, w:w:w) with 2% DDM was then supplemented to the protein at a lipid-to-protein ratio of 0.7. This mixture was allowed to equilibrate overnight before the addition of ~5 mg wet Bio-Beads (Bio-Rad) for overnight detergent removal. The reconstitutions were checked by negative-stain electron microscopy for the presence of densely-packed proteo-liposomes. For poly-L-lysine (poly-lys) coating, 2 μL of poly-lys at a concentration of 0.001% (0.01 mg ml−1) was deposited onto freshly cleaved mica and incubated for 30 s. The excessive poly-lys were rinsed with the imaging buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl at pH 7.6, 150 mM NaCl, apo condition for GltPh), and the poly-lys coated mica was allowed to air dry before the sample physisorption. For HS-AFM imaging of immobilized GltPh molecules, the membrane-extension membrane protein reconstitution (MEMPR) strategy was applied. In brief, the GltPh reconstitution was diluted in the reconstitution buffer with an additional 1 × CMC DDM, to a final protein concentration of ~25 μg ml−1, the SUVs (DOPC:DOPE:DOPS = 8:1:1, w:w:w) was diluted in the same buffer to a final lipid concentration of 1 mg ml−1. The diluted GltPh reconstitutions (~1× CMC DDM) and the diluted SUVs (~1× CMC DDM) were mixed at a ratio of 1:1 to give the prephysisorption mixture. After equilibration for >15 min, 2 μL of the prephysisorption mixture was deposited onto the poly-lys coated mica for 10 min, and then extensively washed with the imaging buffer more than five times to dilute the detergent and remove excessive proteo-liposomes that were not physisorbed.

HS-AFM imaging and data analysis

HS-AFM measurements were performed with an HS-AFM (RIBM) operated in amplitude modulation mode. Igor Pro version 7 was used for HS-AFM data collection. In brief, we used short cantilevers (USC-F1.2-k0.15, NanoWorld) with a nominal spring constant of 0.15 N m–1, a resonance frequency of ~0.6 MHz, and a quality factor of ~1.5 in the imaging buffers10,39. All data were acquired at standard laboratory temperature (298 K). HS-AFM movies were flattened and aligned using home-written ImageJ plugins (ImageJ, NIH).

Construction of raw AFM single-particle frames

Particles from the flattened and aligned HS-AFM movies (2.5 Å/pixel in the A5 example) were picked using a home-written ImageJ plugin ‘Particle Picker’, utilizing a 2D cross-correlation-based pattern recognition algorithm. In brief, a reference particle with a user-defined size (64 × 64 pixels in the A5 example) was manually selected from a reference frame and then symmetrized using the molecular symmetry information (3-fold symmetry average in the A5 example). The symmetrized particle served as the reference for particle recognition and picking in the reference frame, after which the average of all picked particles from this step (aligned and symmetrized) was used as the updated reference for particle recognition and picking for the entire movie. During the image recognition process, the algorithm applies a sliding window to each HS-AFM frame, calculating the 2D cross-correlation coefficient value (CCV) between the reference particle (R) and the window (W), both symmetrized, as:

where μW and μR are the standard deviations and μW and μR the mean measurements of the image height values. Since the particles could be randomly or multi-directionally oriented, the sliding window also rotates to seek the angle giving the highest CCV at each sliding step. Windows with a CCV larger than a user-defined threshold value were marked as ‘pattern-containing’. Since densely packed proteins, especially those forming 2D protein lattice on the membranes were common in AFM experiments, a ‘minimal particle-particle distance’ value (usually proportional to the 2D lattice unit-cell size) was applied to further eliminate windows that are too close to a pattern-containing window with a higher CCV. At last, all particles that met the criteria were merged, without rotation adjustment (to avoid pixel interpolation), to construct a stack of raw AFM single-particle frames in Fig. 1a. The angle information was recorded as a separate output for 3D-LAFM detection coordinates alignment. The procedure ensures that all local maxima from these particles contain real AFM height measurements.

Rationale of automatized and unbiased LAFM

AFM images are pseudo-3D maps, where the image plane represents the x- and y-dimensions, and the pixel intensity (often displayed by a false-color scale) represents the topographical height, h, of the sample surface. However, the convolution of the tip shape compromises the accuracy of sample contouring, affecting the data resolution. The recent development of the LAFM algorithm solved this problem by exclusively extracting the peak detections in AFM images (LAFM detections), where a peak pixel is a local maximum, i.e., is higher than all surrounding pixels in a 3 × 3 kernel, represents therefore a real tip-sample interaction, and is free from tip convolution25. In the canonical LAFM pipeline, single molecules were picked from a raw AFM image or HS-AFM movie to give a raw data particle stack. These particles were expanded, usually from ~2–5 Å/pixel to ~0.5–1 Å/pixel, and translationally and rotationally fine-aligned, to generate a particle stack from which LAFM detections were extracted. Image expansion is necessary to detect local maxima with greater spatial precision, thus effectively breaking the lateral resolution limitations of the pixel sampling and the tip convolution of the raw data. Besides, image expansion enables translational and rotational alignment of the particles with greater precision than the original pixel sampling would allow, facilitating the merging of LAFM detections that characterize identical structural features, e.g., a surface exposed amino acid, from all particles25.

However, both particle expansion and fine alignment relied on bicubic interpolation. This operation inevitably creates additional local maxima, as well as loses track of precise absolute height values of the local maxima, despite yielding higher precision of their lateral position. Besides, in the canonical LAFM pipeline, local maxima were selected based on their prominence, i.e., their height over the surrounding pixels, to avoid the selection of maxima that potentially emerged from noise, where the local maxima prominence threshold was user-defined. We consider these aspects as limitations that challenge the standardization and generalization of LAFM for dynamic structural biology. To this end, we developed a computational pipeline for objective extraction of LAFM detections from raw AFM data (Supplementary Fig. 1). First, we obtained an HS-AFM movie of A5 trimers as an example dataset (Supplementary Fig. 1a). Second, we picked single particles of A5 trimers from the raw data, and, third, extracted local maxima from these raw particles (Supplementary Fig. 1b). Fourth, we used bicubic interpolation, but only to expand pixels surrounding individual maxima (Supplementary Fig. 1c, step 1, 15 × expansion in the A5 example) for lateral peak localization with sub-pixel precision (Supplementary Fig. 1c, steps 2 and 3), where the new local maxima x,y-position (Supplementary Fig. 1c, d, pink cross) must reside within the 3 × 3 pixel kernel (Fig. 1c, box) that defined the original maxima (Fig. 1c, blue cross). Fifth, we recorded the localized maxima x,y coordinates and their original height (h) as unaligned coordinates of the LAFM detections of each particle (Fig. 1a, bottom).

This pipeline takes advantage of the bicubic interpolation to acquire greater spatial precision of the LAFM detections without introducing additional detections. Indeed, an average of ~4.1 × 103 detections was extracted from a single A5 particle (64 × 64 pixels, n = 171), while a ten-fold increased number of detections, ~3.7 × 104, was extracted from the same particles after three-fold bicubic expansion (192 × 192 pixels) in the canonical LAFM pipeline. Moreover, because in our approach the height (h) of the local maxima was determined from the raw data AFM particles before expansion, absolute height values were retained for LAFM detection processing. A similar strategy was also reported in another AFM analysis software that allows LAFM map construction38. In parallel to LAFM detection extraction (Fig. 1a, unaligned coordinates), we obtained the AFM particle alignment information, i.e., translational and rotational particle repositioning with sub-pixel precision, of individual particles with respect to each other from aligning globally expanded particles, as in the canonical LAFM pipeline (Fig. 1a, top, alignment information). The fine alignment information provides the relative spatial relationship of unaligned LAFM detections in the particles to a consensus alignment. Hence, supplementing this information to the LAFM detection extraction pipeline results in aligning LAFM detections bypassing the drawbacks of bicubic interpolation. Since LAFM detections were obtained from only locally expanded images, this pipeline was termed local expansion LAFM detection extraction.

Local expansion LAFM detection extraction

In our method, a local maximum position (Supplementary Fig. 1b) is defined as a pixel that is higher than all the surrounding pixels in its 3 × 3 pixel kernel. Accordingly, we selected all local maxima from the raw AFM single-particle frames and then cropped their 9 × 9 pixel neighborhood images to facilitate sub-pixel localization of the detection positions. Thereafter, we expanded the 9 × 9 pixel neighborhood images using bicubic interpolation (Catmull–Rom interpolation67). This method utilizes a 16-pixel surface (4 × 4 pixel grid) to calculate the intermediate pixel values in the central 2 × 2 area, through 3rd-order 2D polynomial interpolation. The choice of the 9 × 9 pixel neighborhood (before expansion) around each local maximum position ensures the accuracy of the bicubic interpolation calculation in the central 3 × 3 pixel neighborhood (before expansion), where the sub-pixel position of the local maximum detection must reside. Using this method with an expansion scale of 15× (from 2.5 Å/pixel to 0.167 Å/pixel in the A5 example), we generated a series of 135 × 135 pixel local maximum neighborhood images, where the sub-pixel localized detection coordinates could be found in the corresponding central 45 × 45 pixel target regions (Supplementary Fig. 1c, step 1). The sub-pixel localized detection must be a local maximum detection in the target region after expansion. In most cases, there exists a single local maximum position within this region. However, the local maximum that is closest to the image center (in the x-y plane) was selected if multiple positions were observed (Supplementary Fig. 1c, step 2). The integer pixel x,y coordinates of the detection were then adjusted by the expansion scale to give the final sub-pixel localized coordinate pair, x’and y’, of the local maximum position (Supplementary Fig. 1c, step 3). The local maximum h-value, measured from the AFM experiments, and the sub-pixel x’,y’-coordinates (all in decimal format) were then exported as an unaligned LAFM detection (Fig. 1a, bottom row). Finally, all (N) detection pairs were pooled to a stack D, a N × 3 matrix where columns 1, 2, and 3 correspond to x’, y’, h values of each detection, respectively. The local expansion LAFM detection extraction was developed in MATLAB (MatLab, Mathworks). The usage of raw height measurements via the automatized and unbiased LAFM extraction workflow further warrants the accuracy of the final 3D-LAFM densities, and ensures the effectiveness of the overall method.

Alignment of the LAFM detection coordinates

The raw AFM single-particle frames were expanded (5× in the A5 example) using bicubic interpolation. The expanded particles were rotation-adjusted (using the angle output from ‘Particle Picker’) and averaged to generate an alignment reference particle. Then a sliding-window strategy to calculate CCV between expanded particles and the reference particle, both symmetrized before CCV calculation, was applied to find the optimal translation and rotation (based on the angle output from ‘Particle Picker’) of each expanded AFM single-particle frame with respect to the reference particle (for convenience, the particle center is moved to (0, 0) at this step). The particle translation and rotation information was then adjusted by the expansion scale and used to align all LAFM detection coordinates in their x,y dimension (the first two columns in matrix D) (Fig. 1a, top row). In the A5 example, the adjusted coordinate values in D1 (all x’ values) and D2 (all y’ values) were distributed within ±80 Å (particle size is 160 × 160 Å), the height values in D3 (all h values) had a range of ~30 Å, and the total count of detections N is ~42,000.

In the A5 example, the aligned LAFM detections have a lateral resolution of 0.167 Å/pixel and a height resolution <0.25 Å/pixel (depending on the z-piezo sensitivity, ~10 nm/V, the digital-to-analog resolution, 12 bit, and data acquisition range, ±5 V, in the AFM experiments). This z-dimension resolution imaging could be easily boosted to <0.1 Å/pixel by setting the data acquisition range to ±1 V using HS-AFM gain multiplier10. The alignment of the LAFM detections was developed in MATLAB.

3D-LAFM detection stack construction

The aligned LAFM detections with extreme height values should be removed by setting height thresholds hmin and hmax for the following reasons: (1) Including extremely high detections likely due to the tip moving away from the surface may require too much computation power and is unnecessary. (2) Including too many membrane- (for imaging on extended lipid bilayers) or mica-detection may bias the density distribution toward the membrane rather than the protein of interest. Thresholds in the x- and y-dimensions could also be applied to furtherly clean the peripheral detections. In our setup, detections with a 2D-distance of >0.5 × particle-size (80 Å in the A5 example) were removed. In the A5 exmaple, D had a total count of N ~ 36,000 detections after cleaning.

The aligned LAFM detection coordinates, D, were then allocated into a 3D-matrix, the 3D-LAFM detection stack V, with a user-defined voxel size, dv, and a size of I × J × K. The voxel size dv (0.3 Å/voxel used in the A5 example) must be larger than the resolution limit of the detections. Dimensions i and j correspond to the lateral dimensions x (fast-scan) and y (slow-scan) of the AFM particles, while dimension k corresponds to the vertical dimension h of the AFM particles. Voxels in stack V should record the total count of the local detections. Thus, the value of voxel i,j,k, Vi,j,k, is:

Then, 2D molecular symmetry addition (3-fold symmetry addition in the A5 example) was applied to each i-j plane of stack V to conclude the construction of the 3D-LAFM detection stack (V contained ~100,000 detections in the A5 example). The 3D-LAFM detection stack construction was developed in MATLAB.

3D-LAFM detection stack evaluation

To evaluate the 3D-LAFM detection stack V, a 3D mask that covers the detections characterizing the molecular surface (on-target detections) must be created (Supplementary Fig. 3). To this end, we first projected all detections in V along its k-axis onto a 2D i-j plane (k-projection map). Then, a 2D moving-mean filter was applied to the k-projection map, so the region of the molecular surface became outstanding. Using a user-defined threshold, we generated an initial i-j plane mask for the molecular surface 2D geometry. Next, we shrank and/or grew the initial i-j plane mask, pixel by pixel along its circumference, and measured the detection coverage by the mask at each step to search for an optimal mask size. Usually, a decreasing Δcoverage/Δstep (detection coverage change with respect to one-pixel increment) followed by an increasing Δcoverage/Δstep could be found, corresponding to a turning point where the mask starts to include off-target detections. Using this 2D ‘mask growth/shrinking’ strategy, the optimal i-j plane 2D-mask was defined and then applied to each i-j plane of V to select for the on-target detections, resulting in stack Vm2d. Similar to the i-j plane 2D-mask, a 3D mask was made by first applying a 3D moving-mean filter to Vm2d, then creating an initial i-j-k 3D-mask with a user-defined threshold, and finally searching for the optimal i-j-k 3D-mask using the 3D ‘mask growth/shrinking’ strategy. Note that the optimal 2D- and 3D-masks should be almost indifferent to the user-defined threshold values.

The aligned LAFM detection coordinates in D was allocated randomly into two 3D-LAFM detection half-stacks and masked with the optimal 3D mask previously determined to eliminate off-target detections, resulting in half-stacks Va,m3d and Vb,m3d. Then, the FSC method was applied to the two masked half-stacks to determine λhb of stack V (rV) using the half-bit threshold criteria43. The ‘half-bit wavelength’ λhb characterizes the distribution of the aligned LAFM detections in the 3D space, and should depend on the imaging quality and the total count of detections (Supplementary Fig. 3). The 3D-LAFM detection stack evaluation was developed in MATLAB.

3D-LAFM density map construction and evaluation

The 3D-LAFM density map was constructed by applying a 3D density function to each detection in the 3D i-j-k space. In our setup, we used a 3D Gaussian density function N3 ~ (0, rV), where rV is the ‘half-bit wavelength’ value of the 3D-LAFM detection stack V (see “3D-LAFM detection stack evaluation”). This choice to determine the σ value of the 3D Gaussian from the data itself provides a more objective basis for this parameter reflecting the 3D spatial distribution of the aligned LAFM detections, which is likely different for each individual dataset, related to differences of the proteins under investigation and/or instrument- or experiment-dependent noise. One can anticipate that more densely distributed LAFM detections, likely to be found in high-quality raw data with small pixel size should give smaller σ values, which in turn avoids over-smoothing of the probability density. In contrast, lower-quality data will result in wider detection distributions and thus larger σ values, which must be assigned to compute reliable densities from less densely distributed detections. Hence, we constructed the 3D-LAFM density map, P, by a convolution operation, as:

where τ is the size of the 3D density function kernel, and a τ > 5 × rV was used in our setup. The resulting density map P was then 2D-symmetrized at each i-j plane (see “3D-LAFM detection stack construction”).

To evaluate the 3D-LAFM density map P, we applied the same 3D density function to the two (unmasked) half-stacks Va and Vb, and then analyzed their FSC curve using the half-bit threshold criteria for the 3D-LAFM density map ‘half-bit wavelength’ value rP. The 3D-LAFM density map construction and evaluation were developed in MATLAB.

Converting the 3D-LAFM density map to a ‘.afm’ file

The 3D-LAFM density map P (a 3D-array matrix of 32-bit single values) was encoded into an MRC2014 extended ‘.afm’ file using a home-written MATLAB ‘encoder’. To allow data deposition into common repertories as well as promote experimental and analytical details sharing, we used the extra space (Word 25–49, Bytes 97−196) in the MRC2014 file header for the storage of essential parameters (Table 1)47. Once a home-written Python ‘decoder’ is installed, the ‘.afm’ file is compatible with Chimera27, a common structural biology 3D viewer (see Supplementary Methods: “Accessing ‘.afm’ files in ChimeraX”). Note that metadata code AFM1 is introduced for 3D-LAFM density map (Table 1, Word 27)

High-density 3D-LAFM surface representation

The 3D-LAFM density map, encoded as an MRC2014 extended ‘.afm’ file, was opened in Chimera as volume data and displayed in the surface mode, which allowed an iso-density surface to be calculated at any user-defined density value. Then, we colored the top ~7 Å of the density map using the LAFM false color codes25 by the height values. To generate a high-density 3D-LAFM surface representation, we collected ~200 iso-density surface snapshots at a user-defined view (e.g., top or side) with descending density values. The snapshots were exported to ‘png’ files with the ‘transparent background’ mode in Chimera. The first three of the four channels in these ‘png’ files record the RGB color values (LAFM false color codes) of the pixels, informing the surface height as colors, while the last channel encodes the transparency (alpha) values, corresponding to the density value (normalized to 0–255) used in the iso-surface generation. If the pixel corresponds to an empty position, i.e., gaps in the high-density iso-surfaces, the background color (RGB = 0/0/0 for white or 255/255/255 for black) was assigned to the RGB channels.

These snapshots were merged using a home-written MATLAB script. The snapshots were first ordered by descending density values to generate a stack of images, i.e., snapshots taken with high-density values were placed in the front of the stack. Then all background pixels in the stack were assigned a value of 0 in their transparency (4th) channel (100% transparent). We next looked at each i-j column of the stack for the first non-transparent pixel and assigned its color code r,g,b, and transparency α to the corresponding pixel in the high-density 3D-LAFM surface representation image.

The high-density 3D-LAFM surface reflects the most probable height (color) at a position with the corresponding probability of detection (transparency), similar to the (2D) LAFM map25. However, this conversion loses the information of the width of the detection distribution which presumably reflects the local dynamics of the imaged region. Therefore, AFM structural features should be directly analyzed in the 3D-LAFM matrices, not the high-density surface images. The surface representation strategy could be applied to different views of the volume data, but the top view is the most reliable. Note that this representation is not for any detailed comparison or analysis of the 3D-LAFM data with the atomic structures but for a visual of the 3D-LAFM density map.

MDs flexible fitting

MDFF simulations37,48 were set up in VMD (version 1.9.4)68 and performed using NAMD (version 2.13)69 with the CHARMM27 force field52. To incorporate the AFM data as the external potential used by MDFF, the 3D-LAFM density map was converted to UAFM (see “3D-LAFM MDFF force field”) and integrated into the potential energy function, as:

where Utotal is the total potential, UMD the conventional MD potential energy function, USS the potential to preserve the secondary structure of proteins, and UAX the auxiliary potentials (see discussions below).

All atomic structures were first rigid-body docked into the target 3D-LAFM density map in ChimeraX. To avoid overfitting and prevent structural artifacts, restraints for dihedral angles and hydrogen bonds were added to enforce the secondary structure of the protein, as well as restraints generated for preserving the cis/trans configuration and chirality (USS). If applicable, domain and symmetry restraints were then applied to maintain domain rigidity and the inherent structural symmetry of the proteins as auxiliary potentials (UAX)70, respectively. All MDFF simulations in this study were performed for 60 ns, comprising three distinct cycles. Each cycle commenced with an initial energy minimization step of 2 ps, followed by a running process of 20 ns, and concluded with an additional minimization step of 2 ps. The symmetry restraint was applied to all three cycles, while the domain restraint was applied to the first two cycles to assist potential large domain movements. All simulations were carried out at a constant temperature of 300 K, at 1.01 bar pressure, and Langevin dynamics with a damping coefficient of 5 ps−1, and a time-step of 1 fs. Detailed parameters and constraints are provided as supplementary files (Supplementary Methods).

3D-LAFM MDFF force field

The 3D-LAFM MDFF force field UAFM was constructed using a home-written MATLAB script. UAFM consists of an active fraction (UAFM–a), where the force is proportional to the gradient of the 3D-LAFM density map and covers the molecular surface, and an inactive fraction (UAFM–i), where the space is filled with a background-matching density value and covers the rest of the space below the 3D-LAFM density map. UAFM–a was constructed by normalizing the 3D-LAFM density map to [0, 1]. To construct UAFM–i, we generated simulated 3D density data from the atomic structure of the protein using a very large resolution of 10 Å. Then, the i-j cross-section of the protein was obtained by projecting the 3D simulated density volume along its z-axis (corresponding to the height dimension in AFM) and then normalized to [0, 1]. To merge UAFM–i and UAFM–a, we calculated the mean value of the background densities in UAFM–a, using the same 3D-mask for 3D-LAFM detection stack evaluation (see “3D-LAFM detection stack evaluation”, ~0.03 in the A5 and GltPh maps). Using this value as a cutoff, we replaced all voxels below it in UAFM–a with the smaller of the cutoff and the value of the corresponding UAFM–i voxel to generate UAFM.

Analysis of the MDFF trajectories

The internal energy (E) and root-mean-squared distance (rmsd) measurements of the MDFF trajectories were directly obtained from NAMD and VMD, respectively. The normalized cross-correlation between the 3D-LAFM density map and the atomic structures (simulated 3D density data with a resolution of 10 Å) was calculated in Chimera. It should be noted that the (HS-)AFM imaging presumably perturbs the flexible regions on the molecular surface. Therefore, 3D-LAFM MDFF force fields are expected to predominantly drive the movement of structured molecular backbones. It should be taken with caution while analyzing the flexible region movement from these simulations. For A5 MDFF trajectory analysis, the structured annexin repeats were defined as: repeat I: Residues 17–28, 35–72, and 75–85; repeat II: Residues 88–144 and 148–158; repeat III: 169–217 and 232–245; And repeat IV: 247–259 and 266–318. For GltPh MDFF trajectory analysis, the movements of the transport- and trimerization- domains, were analyzed using a home-written MATLAB script. In brief, we defined four collective residues: res1: Residues 80–84, 250–263, 287–302, and 404–417 (transport domain cytoplasmic side); res2: Residues 377–382, 326–328, and 223–227 (transport domain extracellular side); res3: Residues 167–170 (trimerization domain cytoplasmic side); And res4: Residues 150–153 (trimerization domain extracellular side). The mean coordinates of these collective residues in the MDFF trajectories were tracked to illustrate the domain movements. Specifically, the angle between vector res2-res1 (transport domain vector) and the z-axis (θ) as well as the angle between vector res4-res3 (trimerization domain vector) and the z-axis (ψ) were used the characterize the opening/closing of the transport- and trimerization- domains, respectively. The z-axis projection of vector res3-res1 (dz) was used to characterize the height difference between the transport- and trimerization domains from the cytoplasmic side which was exposed to the tip in the AFM experiments. The computational fitting of a molecule into an experimentally derived conformation using the experimental constraints as an external force field does not necessarily represent a meaningful transition. The process itself is as meaningless as morphing, but the resulting MDFF structure is of interest. Consequently, the analysis of the resulting trajectories should focus on the effective convergence of the structural models to the experimental data, rather than interpreting the trajectory as a physically accurate depiction of protein dynamics.

Structural analysis