Abstract

Using a systematic ab initio quantum many-body approach that goes beyond low-energy models, we directly compute the superconducting pairing order and estimate the pairing gap of several doped cuprate materials and structures within a purely electronic picture. We find that we can correctly capture two well-known trends: the pressure effect, where the pairing order and gap increase with intra-layer pressure, and the layer effect, where the pairing order and gap vary with the number of copper-oxygen layers. From these calculations, we observe that the strength of superexchange and the covalency at optimal doping are the best descriptors for these trends. Our microscopic analysis further identifies that strong short-range spin fluctuations and multi-orbital charge fluctuations drive the development of the pairing order. Our work illustrates the possibility of a material-specific ab initio understanding of unconventional high-temperature superconducting materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since the discovery of high-temperature superconductivity in the cuprates almost 40 years ago, obtaining a microscopic description of the phenomenon has challenged theoretical materials science1,2. In particular, the search for new materials with higher transition temperatures has been hindered by the absence of predictive computational links between the material structure/composition and the observed superconducting temperatures. Here, we describe microscopic calculations that reproduce some of the best-known material trends in cuprate superconducting critical temperatures Tc via the direct ab initio computation of the ground-state pairing order, using only the material structure as input. These rely on new methods to solve the quantum many-body Schrödinger equation in the materials without first simplifying to low-energy models. Analyzing the solutions identifies simple descriptors which correlate with transition temperature and the fluctuations that drive the microscopic process of pairing. Overall, our methodology demonstrates a path towards predictive ab initio computations of high-temperature superconductivity in new materials.

Cuprate superconductors are layered perovskite compounds with two-dimensional copper-oxygen planes separated by buffer layers of atoms, which dope the planes either with electrons or holes. In the parent undoped state, the materials are antiferromagnets, becoming superconducting after doping beyond ~5%3,4. Out of the many efforts to increase Tc through altering the composition and structural parameters, some trends can be identified. Two of the clearest ones are the pressure effect and layer effect. In the pressure effect, onset Tc increases with pressure applied in the plane, rising, e.g. in Hg-1223 from 135 K at ambient pressure to 164 K at 30 GPa5,6. In the layer effect, Tc increases with the number of stacked copper-oxygen planes (e.g. in the mercury-barium cuprates, Tc is 97, 127, 133 K in the 1-, 2-, 3-layer compounds7).

Many theories have been proposed to rationalize cuprate superconductivity, but it has proven difficult to obtain a detailed microscopic picture, and even harder to reproduce the specifics of different cuprate materials. There are two essential complications. First, the phenomenon arises from quantum many-body physics with strong electron interactions, where there are no analytical solutions and there is no obvious small parameter8. (This is in contrast to conventional superconductors with weak electron interactions, where material-specific computations are relatively successful9,10). Within any microscopic framework to describe the electron correlation, the predictions thus carry uncertainty from their approximate nature. The second is that the complex material composition complicates the derivation of low-energy Hamiltonians. While one-band Hubbard models and their relatives have informed much current thinking11,12, recent accurate numerical solutions of these models have also highlighted the deviation of the model physics from that of the real materials and the sensitive dependence of the physics on the model13,14,15,16,17,18. In addition, although there has been progress in rationalizing material specific effects in terms of parametrized multi-band models12,19,20,21 the uncertainty introduced into the Hamiltonian arising from downfolding, for instance, due to density functional theory double-counting22, the definition of impurity orbitals23, or the difficulties of parametrization or uncertainty of the parametrized form24, appears comparable to the strength of the material trends.

In principle, solving the ab initio many-electron Schrödinger equation for the full cuprate material provides an unambiguous and material-specific route to understanding cuprate superconductivity. Although this is traditionally viewed as intractable, recent advances in numerical many-body algorithms and their computational implementation are opening up the possibility of predictive ab initio computation even in strongly correlated quantum materials. While such calculations are more expensive than their model counterparts and thus more limited in the system size that can be treated, they are complementary to the low-energy model approach as the microscopic Hamiltonian unambiguously reflects the material-specific composition, at the expense of a less detailed description of long-range physics. As one example of the success of such a strategy, we previously captured, and illuminated at the atomic level, systematic trends in the magnetism of the parent state of the cuprates with such an approach25. Here, we show how these strategies may be extended to the much more challenging doped phases of the cuprates, and in particular to obtain the superconducting pairing order and an estimate of the pairing gap. Below, we describe the advances that now make this work possible, the cuprate systems we will study for their systematic trends, and the results and insights that derive from this approach.

Results

Quantum simulation methods

We aim to approximate, ab initio, the ground-state of the electronic Schrödinger equation of the bulk cuprate (phonon and temperature effects are thus ignored). The strategy has three pieces: a quantum embedding (density matrix embedding theory (DMET)) to connect the bulk many-body problem to a self-consistent impurity many-body problem; the quantum chemical solution of the impurity problem; and the quantum chemical mean-field solution of an auxiliary bulk problem. To retain material specificity, the Hamiltonians use ab initio bare electronic interactions, expressed in a basis of a few hundred of bands, thus no reduced models appear.

Density matrix embedding theory has been introduced elsewhere26, and its application to doped Hubbard models13,27,28 and ab initio cuprate parent states, extensively benchmarked25. We briefly recount essential details in Fig. 1. DMET provides a zero-temperature quantum embedding that maps the interacting bulk problem to the self-consistent solution of two systems: an interacting quantum impurity and an auxiliary mean-field bulk problem. The quantum impurity is taken as a computational supercell (with all atoms) of the material, coupled to a bath constituting the most important orbitals of its environment. The auxiliary bulk Hamiltonian Hlatt is a mean-field crystal Hamiltonian, augmented by a one-electron operator Δ in each unit cell. The mean-field ground-state Φlatt (a Slater determinant or Bardeen-Cooper-Schrieffer (BCS) state, depending on Δ) determines the bath orbitals, and thus the embedding (impurity plus bath) Hamiltonian Hemb(Δ). The impurity ground-state Ψemb then determines the order parameter κemb. The quantum impurity and auxiliary bulk problems are solved self-consistently with respect to Δ until κlatt(Δ) = κemb(Δ). Δ and κ can acquire finite values for ordered phases due to symmetry breaking in the self-consistency.

The ab initio density matrix embedding theory (DMET) framework. This involves solving two ground-state problems: for an auxiliary mean-field Hamiltonian (left), Hlatt = f + Δ → Φ(Δ), and a quantum impurity + bath Hamiltonian (right), Hemb(Δ) → Ψemb(Δ). Δ is modified by self-consistent iteration until the pairing order κ is the same in the impurity and the auxiliary mean-field problem. The non-number-conserving \(\bar{\Delta },W,Y\) terms in Hemb arise from the DMET bath construction from Φ(Δ). In this work, the bulk problem is represented by 128 cuprate unit cells, and the impurity is a 2 × 2 supercell, illustrated above for CCO (CaCuO2).

In an ab initio description, we start with an atomic orbital representation of the crystal. For bases with reasonable accuracy, this gives rise to many bands, e.g. a few hundred bands per computational cell. The quantum impurity, which contains the orbitals of the atoms in the impurity, thus also contains hundreds of orbitals, and we require an ab initio many-body treatment for such problems. Fortunately, only a few orbitals are strongly correlated, so we can use quantum chemistry strategies designed to handle hundreds of orbitals with a few strongly correlated ones: here we primarily use the coupled cluster singles and doubles (CCSD) approximation29. Such coupled cluster wavefunctions are widely used in molecular, and more recently materials, modeling and have proved accurate for ordered states (in the current setting we additionally verify their accuracy through other quantum chemical methods, such as the ab initio density matrix renormalization group30).

In the context of the doped phases of the cuprates, new ingredients appear, such as the treatment of doping. In real materials, doping usually involves dopant atoms, which enlarge the computational cell31. For simplicity, we use implicit doping which modifies the charge density while introducing a compensating positive field, either within the “rigid-band” approximation (RBA, uniform background field), or (for a subset of calculations), the virtual crystal approximation32 (VCA, scaled external field at select atoms). These treatments of doping are undoubtedly crude. Although detailed results for individual structures are sensitive to the doping formulation, we find trends across the materials to be preserved within a fixed doping scheme.

Another new ingredient is the ab initio simulation of superconducting phases. Defining \(\Delta={\sum }_{ij}{\Delta }_{ij}{a}_{i}^{{{\dagger}} }{a}_{j}^{{{\dagger}} }+{{{\rm{H.c.}}}}\) and \({\kappa }_{ij}=\langle {a}_{j}^{{{\dagger}} }{a}_{i}^{{{\dagger}} }\rangle\), past a critical doping, the DMET self-consistency produces a finite Δ and κ. Such superconducting solutions are not usually supported by ab initio quantum chemistry solvers. To handle this, we use the Nambu-Gorkov formalism33 which, for Sz = 0 pairing, maps broken particle number symmetry to broken Sz symmetry. This creates a particle-conserving Hemb amenable to standard quantum chemistry methods, as further detailed in Section 1 of ref. 34.

The scale of the simulations in this work also required additional innovations. For example, to achieve an affordable description of the quantum many-body state, we developed new, compact, Gaussian atomic bases, of correlation-consistent double-ζ plus polarization quality. Similarly, to treat doped states which may be metallic, we adapted our orbital localization, self-consistency procedures, and solver algorithms for metallic systems. These and other technical improvements are discussed in Section 1 of ref. 34.

The outputs of the ab initio DMET procedure are a correlated quantum impurity wavefunction Ψemb and a mean-field bulk wavefunction Φlatt. The former can be used to obtain impurity observables, such as the pairing order, while the latter provides additional information (albeit of limited fidelity) on long-range non-local observables. κ is a multi-orbital quantity, and can be summed into a scalar order parameter with different angular symmetry (in various ways due to the multi-orbital character, see Eqs. (S71) and (S72)); we use mSC to denote the scalar summed quantities. The impurity fluctuations that give rise to these orders can be analyzed from Ψemb.

Because the pairing order is not easily measurable, we also consider additional quantities to place our results in an experimental context. We compute the maximal pairing gap Eg (approximately corresponding to ~ 2Δ0 in a 1-band BCS theory) of the auxiliary bulk Hamiltonian Hlatt + Δ. We note that this is not the same as computing the pairing gap of the interacting bulk problem, but we are using it to provide information in a manner analogous to how a DFT bandgap is used to provide information on the true bandgap of the problem. In the weak-coupling regime (which may not include the cuprates), 2Δ0 is also proportional to Tc (see Section 3.7 of ref. 34).

Within the above formulation, the errors can be attributed to the following sources: the finite impurity supercell, the finite atomic orbital basis, approximations in the many-body solver, and approximations in the DMET self-consistency. In principle, these errors can be improved to exactness, as has been analyzed in ref. 25. In practice, the errors remain finite in our computation. For example, the finite impurity supercell in this work means that we omit some interesting long-range physics, such as stripes or other long-wavelength orders. Our calculations may then be viewed as asking, if we restrict ourselves only to orders that can be formed in the finite cell, is the physics sufficient to explain material-specific trends? Below, we will examine such questions through computation.

Cuprate systems and computations

We consider two series of hole-doped cuprates to study the pressure and layer effects. The first is CCO (CaCuO2), viewed as a parent compound for a variety of doped cuprates. When mixed with Sr, it has been doped with vacancies (approximate composition \({({{{{\rm{Ca}}}}}_{1-y}{{{{\rm{Sr}}}}}_{y})}_{1-\delta }{{{{\rm{CuO}}}}}_{2}\) with y ~ 0.7, δ ~ 0.1, Tc ~ 110 K35). The simple structure of parent CCO makes it ideal for studying the pressure effect. We apply pressure along the a, b axes of the cuprate plane in a manner which can be compared to the uniaxial pressure derivatives dTc/dPa, dTc/dPb extracted in ref. 36. (We note that in the hydrostatic experiments of ref. 6, the trend of increasing Tc with pressure (positive dTc/dP) was observed for the onset Tc across a series of mercury cuprates5, but for Tc corresponding to bulk zero resistance, was found to be compound specific6. Given that the small size of our simulation cells does not allow for a full treatment of phase fluctuations, capturing the difference between onset and zero resistance Tc is beyond our current description).

The second series of compounds are the mercury barium cuprates, single-layer Hg-1201 (HgBa2CuO4+δ) and double-layer Hg-1212 (HgBa2CaCu2O6+δ). In the experimental setting, this series can be continued up to 6-layers, but the computational cell of these systems is too large for a practical treatment. Consequently, to give some information on the large layer limit, we consider CCO as a crude comparison to form the infinite layer parent compound in this series. The mercury-barium compounds are synthesized under conditions with finite oxygen doping. In Hg-1201 we use a structure corresponding to a reported oxygen doping δ = 0.19, associated Tc ~ 95 K37; in Hg-1212, we consider two structures38: the oxidized structure ("ox”, with δ = 0.22, Tc ~ 128 K), and a variant argon-reduced structure ("red”, close to the undoped compound, δ = 0.08, Tc ~ 92 K).

The computations start with a mean-field density functional (DFT) calculation using the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof with exact exchange (PBE0) functional in a custom polarized double-zeta Gaussian basis (described in Section 2.2 of ref. 34) sampling the Brillouin zone corresponding to 8 × 8 × 2 k-points of the primitive cell. (More precisely, we use supercells, thus using a 2 × 2 supercell, we sample the corresponding 4 × 4 × 2 folded Brillouin zone). The increment of doping in the DMET calculation derives from the size of the bulk calculation: we can dope in units of 1/128. Because we do not perform full self-consistency on the charge density (see below), it is necessary to use a mean-field starting point that produces a reasonable charge distribution. We select the PBE0 functional based on its performance relative to accurate quantum many-body embedding benchmarks in our previous work on the parent state25. The PBE0 solution is antiferromagnetic (AFM) at half-filling, and in some cases, becomes paramagnetic beyond a certain doping. The PBE0 calculation generates the initial auxiliary mean-field Hamiltonian f (Fig. 1), but this does not enter the many-body impurity Hamiltonian Hemb. Thus the correlated DMET calculations do not have a double counting error.

The quantum impurity problem consists of the 2 × 2 cell of the cuprate and the DMET bath constructed for the valence orbitals in the impurity, yielding a total problem size of 300-900 orbitals. The upper range corresponds to the large cells of the mercury-barium compounds, and to reduce the cost we used coupled sub-impurities to separately treat the CuO2 and buffer layers25; the largest sub-impurities contain 376 orbitals. As already discussed above, the 2 × 2 cell means that we omit long wavelength physics, such as stripes, which we discuss further in Section 4 of ref. 34. For the results discussed below, we show data from CCSD as a compromise between speed and accuracy. Benchmarks of CCSD against exact solvers in the parent state25, in the DMET treatment of the 2D one-band Hubbard model and in the ab initio cuprate impurity problem (Figs. S3 and S4) suggest we reach sufficient accuracy to discuss the material trends of interest.

To simplify the convergence of the self-consistency, we carry it out with respect to the pairing potential Δ restricted to the three-band Cu 3\({d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) and O 2px(y) orbitals with matrix elements restricted to obey C2h point group symmetry. This allows for the direct update of the pairing density κ (to self-consistency), although it limits self-consistency on the normal charge density itself. In addition, we do not update the charge contribution to the mean-field f. Without full charge self-consistency, the converged DMET solution retains a dependence on the initial choice of mean-field f and initial density. The effect of this dependence is discussed more below and in Section 3.8 of ref. 34.

The pressure effect

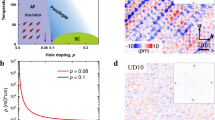

We first examine the computed order in CCO at three different in-plane pressures: -19, 0 (ambient), 32 GPa. Without doping, CCO is in an antiferromagnet. At all pressures, under sufficient doping, a superconducting state is formed with predominantly d-wave pairing order, as illustrated by the Cu-Cu pairing order at optimal doping in Fig. 2B; the d-wave character increases with increased pressure. There is also a small s-wave piece in the Cu-Cu pairing, and the total order has a small p-wave component necessarily arising from the coexistence of AFM and d-wave superconducting order16,39. The uncertainties of the calculation mean that the absolute numerical values for the order should be treated with caution. However, we can obtain a conversion to experimentally accessible quantities through the computed pairing gap amplitude Eg (right-hand axis of Fig. 2E). The pairing gap closely follows the pairing order and the maximum shows the same trend with pressure. Using the weak-coupling result (with its associated limitations) for the conversion of the gap to Tc (Section 3.7 of ref. 34), we obtain Tc ~ 180 K at ambient pressure, of the same order as that typically seen in experiment. Then dTc/dP ≈ 4 − 5K/GPa, comparable to the value extracted from the uniaxial pressure derivatives dTc/dP ~ 2dTc/dPa ~ 4 − 6 K/GPa36. Our calculations thus capture the qualitative structural trend of pressure on the maximum superconducting order and temperature.

A Structure of the ∞-layer cuprate CCO (CaCuO2). B d-wave and s-wave order as a function of pressure p, using different doping representations (rigid band approximation (RBA) and virtual crystal approximation (VCA)). C Anomalous density κ(R0, r) + κ†(R0, r) for CCO at optimal doping and ambient pressure. The reference point R0 is near the Cu atom in the embedded cell. mSC (Cu): pairing order between neighboring Cu atoms showing d-wave symmetry. D Orbital-resolved d-wave SC orders between Cu orbital pairs. E AFM, SC order m and estimated SC gap Eg as a function of doping using RBA (VCA curves shown in Fig. S6). The error bar at x = 0.7 doping at 32 GPa is also shown due to the slow convergence of DMET.

Figure 2C shows a real-space visualization of the Cu-centered pair amplitude, and the scalar pair amplitude between orbitals on neighboring Cu atoms, for CCO at ambient pressure and optimal doping. The sign of the pairing amplitude illustrates the d-wave symmetry, while the spread (not shown) corresponds to a pair distributed across a linear distance of about 6 unit cells. We show a more detailed orbital resolved analysis of the Cu-Cu d-wave order at optimal doping in Fig. 2D. As illustrated in Fig. S5, as doping increases the pairing orbital character changes, with Cu-Cu pairing at small doping being predominantly 3d-3d, but at larger dopings containing more 4s and 4d components. We find that O-O pairing contributes about 30% to the total d-wave order, with Cu-O pairing contributing mainly to the p-wave order.

We now examine in detail the AFM and SC orders as a function of doping in Fig. 2E. We first discuss the x-axis, the doping axis. When holes are added, the charges go primarily to the CuO2 plane, and reside mainly on oxygen (2p), with a fraction (about 20–30%) transferred to Cu; about 90% of the charge resides in the three-band orbitals (Cu 3\({d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) and O 2px,y), and about 97% in the Cu-O plane. In experiments on oxygen doped cuprates, such as yttrium barium copper oxide40 and the mercury barium cuprates studied later41, the effective Cu doping is usually not taken from the estimated oxygen content, which (depending on the assumed formal charge of the dopants) could translate to very large copper-oxygen plane dopings. Instead, the effective doping of the copper-oxygen plane is inferred from an empirical formula40,41. This empirical formula suggests that the optimal doping of the plane is usually about 10%–15% by which the magnetic order is seen to vanish.

In contrast, we see that the local moment in our calculations decays quite slowly and the SC order appears only at much larger dopings. This primarily reflects the residual dependence of our non-charge-self-consistent DMET calculations on the initial DFT charge density, which also has a similarly slow decay of the local moment. (An extreme example of this is -19 GPa system, where the moment does not decrease even under heavy doping).

While full charge self-consistency was too expensive to explore here, we can understand its potential corrective effect in a 3-band model (see Section 3.8 of ref. 34). When doping holes into the model, they go into a pair of (i.e. ↑ and ↓) spin-polarized bands that have mixed Cu–O character. Thus some of the ↑ and ↓ spin-hole density overlaps on the oxygen atoms (with compensated moments) and the residual cell moment comes only from the uncompensated moment on Cu. As shown in Section 3.8 of ref. 34, allowing for charge self-consistency changes the Cu–O character in the 3-band model. This leads to a much faster decay of the magnetic moment.

It is interesting to replace the bare doping here with the hole content on Cu computed from the atomic populations, xCu. Using this rescaling, we empirically observe that the maximum d-wave order appears at a Cu hole content (10%–15%) similar to that seen in one-band treatments42, as well as in experiment. The optimal doping is close to the point at which the magnetic order suddenly drops.

The numerical values of the magnetic and pairing orders depend on details of the doping treatment: for example, the difference in the maximum pairing order between a VCA and RBA treatment is shown in Fig. 2B and Fig. S6. This highlights the need to investigate more realistic representations of dopants. However, the qualitative pressure trend in the pairing order is reproduced in either case.

The layer effect

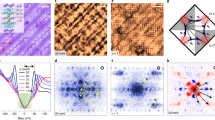

We next consider the layer effect in the mercury barium cuprates (1-, 2-layer) using CCO as a proxy for the ∞-layer compound. The plot of the maximum pairing order as a function of the layer number is shown in Fig. 3C. We see a sizable increase in the maximum pairing order moving from Hg-1201 to Hg-1212 (ox). The maximum pairing gap Eg (right axis of Fig. 3D) shows the same behavior as the pairing order. Both are similar to the experimental change in Tc. Again, although the proportionality between Eg and Tc is a weak-coupling relation, arguably we seem to capture the basic experimental trend in Tc of the layer effect. For more than 3 layers, experimentally it is seen that Tc no longer increases, which has been attributed to the potentially inhomogeneous doping of the different copper-oxygen planes. In CCO, inhomogeneous doping is not part of our representation. However, assuming CCO is a reasonable analog for the ∞-layer limit of the mercury barium cuprates, we find that the pairing order and pairing gap decrease slightly from Hg-1212 to CCO, similar to the experimental trend between 3-6 layers, although the small magnitude of the change is challenging within the uncertainty of our numerical approach. Our result for CCO is also in good agreement with the Tc for the mixed Sr/CCO compound (assuming that reflects the Tc of CCO).

Structures of (A) single-layer Hg-1201 (HgBa2CuO4) and (B) double-layer Hg-1212 (HgBa2CaCu2O6). C Comparison between calculated d-wave SC orders mSC (bar) and pairing gaps Eg (cross marker) (Hg-1201, Hg-1212, and CCO) and experimental Tc (data from refs. 7,35) as a function of the number of layers per cell. D AFM, SC orders m, and estimated SC gap Eg of different compound structures (Hg-1201, oxidized Hg-1212, and reduced Hg-1212). E Electron density difference between oxidized and reduced Hg-1212 at optimal doping (red: increased electron density of oxidized vs. reduced, blue: decreased electron density). The arrow indicates the transfer of charge between reduced and oxidized structures.

The pairing and magnetic orders are shown in Fig. 3D. The qualitative behavior in the mercury-barium cuprates is similar to that in CCO, although here, the hole density is less localized on the Cu atoms, and some fraction goes to buffer atoms (e.g. apical oxygen orbitals). There are other important microscopic differences between the mercury-barium compounds and CCO. For example, in CCO, the magnetic order at half-filling decreases between ambient and 32 GPa pressure, and this is reflected in the more rapid decrease of the local moment close to optimal doping. However, even though the local moment in Hg-1212 decays more slowly than in Hg-1201, the optimal pairing order is larger.

The argon-reduced Hg-1212 structure is similar to the oxygenated structure but has a larger apical Cu-O distance (by about 0.04 Å). Although the experimental sample corresponds to very low oxygen doping where it is not expected to superconduct, it is still observed to have a Tc ~ 92 K38, leading to speculation about complex charge-transfer behavior in mercury barium cuprates. We find that the undoped magnetic behavior (e.g. exchange couplings and charge distribution) is almost identical in the Hg-1212 (ox) and Hg-1212 (red) structures (see Table S4). Nevertheless, as we dope the reduced structure, we find that holes distribute differently in the reduced and oxidized form, especially near optimal doping (xtot ~ 0.5) where the effective Cu doping is smaller in the reduced structure than the oxidized structure, along with a reduction in pairing order (as in the experiment, but much larger in magnitude). The difference in the Hg-1212 (ox) and Hg-1212 (red) electron densities is shown in Fig. 3E: the main difference corresponds to a transfer of charge from the in-plane O 2p orbitals in the (red) structure, to the apical O and Hg orbitals in the (ox) structure, leaving the Hg-1212 (ox) with a larger in-plane doping. The sensitivity of pairing order to the charge distribution highlights the need to further investigate the treatment of doping and the charge density. Overall, the complicated behavior confirms the importance of atomic scale crystal structure in the development of the pairing order in these multicomponent, multilayer cuprates.

Descriptors for superconductivity in the cuprates

Our ab initio calculations above capture the correct pressure and layer effects on pairing order across several cuprate structures and compositions. We can therefore interrogate these in silico solutions to identify the features of the electronic structure that most correlate with these trends.

In Fig. 4 we plot maximum pairing order against a variety of descriptors: (i) the magnetic (nearest neighbor Heisenberg) exchange parameter J, derived from the same ab initio methodology applied at half-filling following ref. 25, (ii) oxygen hole content at optimal doping (ΔnO), (iii) the bond order between Cu 3d-O 2p \(\left(\sim {\left\langle {a}_{3{d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}}^{{{\dagger}} }{a}_{2{p}_{x(y)}}\right\rangle }^{2}\right)\), see Eq. (S68)). (i) and (ii) have previously been invoked as descriptors in the literature (see e.g. refs. 43,44); exchange has been associated with cuprate superconductivity since the earliest discussions45,46 and its correlation with Tc has attracted much experimental interest44,47,48,49. Both (ii) and (iii) are related to the charge-transfer gap and covalency of the Cu-O bond, which are commonly discussed in theoretical treatments21,50,51,52 as well as in various experiments48,53,54,55,56. However, it should be noted that (ii) and (iii) are related but different probes of these quantities: (ii) measures the diagonal part of the density matrix, while (iii) measures the off-diagonal part. (We note that the J values obtained here are somewhat smaller than have been reported in the experimental literature for some of these compounds44 (and about 20% smaller than we reported in ref. 25 due to the different initial density) but we use J values from the same computational approximations as for the rest of this work for internal consistency).

Correlation between superconducting order and selected descriptors. A Super-exchange coupling parameter J at half-filling. B Average number of holes on oxygen ΔnO at optimal doping. C Bond order (off-diagonal measure of covalency) at optimal doping. Linear regression R values are also shown. RBA, VCA: rigid band approximation, virtual crystal approximation.

We see that the best qualitative descriptor for the trends in pairing order is the exchange parameter J, which captures the general features of both the pressure and layer effect. The correlation between pressure and J is straightforward, as increasing pressure increases the kinetic contribution in the super-exchange mechanism. We discussed the microscopic origins of the layer effect on J in ref. 25. These are subtle, involving both mean-field (i.e. band structure)57 and correlated electronic effects25 with the apical orbitals. However, J does not give the right ordering for Hg-1212 (red) and Hg-1212 (ox), which have almost the same J but very different pairing orders. This is unsurprising, because J is derived from magnetism in the undoped compound, and neglects the material-specific aspects of doping, which we saw were different in Hg-1212 (red) and Hg-1212 (ox). We emphasize that the correlation between J and pairing order appears in our study in a material-specific manner, where both quantities are obtained within the same computational approximation.

Unlike J, the oxygen hole content and bond-order at optimal doping are descriptors in the doped state. They both correlate with the pairing order (capturing the pressure effect) and for example, successfully distinguish between Hg-1212 (red) and Hg-1212 (ox), with their different doping dependent electronic structure. The bond-order descriptor has a particularly good average correlation. However, both descriptors do not capture the layer effect. The oxygen hole-content and bond-order reflect mainly the single-particle part of the super-exchange mechanism that gives rise to J, and thus do not capture the subtle dependence on the layers.

The strong correlation of the trends in the pairing order with the local descriptors suggests two things. The first is that systematics in pairing can be understood in terms of quantum correlations at a relatively local level. The second is that the physics of superexchange, appropriately modified to account for material-specific doping, is likely behind the trends in pairing. We now examine this possibility.

Microscopic analysis of fluctuations and pairing

To obtain a clearer understanding of the microscopic processes driving pairing, we examine the fluctuations in the correlated quantum impurity wavefunctions Ψemb that lead to the SC order. In the one-band Hubbard model, such fluctuation analyses have previously been employed for the 2-particle Green’s function58, and here we devise some time-independent analogs.

Within the CCSD solver, \({\Psi }^{{{{\rm{emb}}}}}={{{{\rm{e}}}}}^{{T}_{1}+{T}_{2}}\left\vert \,{\mbox{m.f.}}\,\right\rangle\), where \(\left\vert \,{\mbox{m.f.}}\,\right\rangle\) is a Slater determinant (in the non-SC phase) and a BCS state (in the doped SC phase), where the mean-field is determined by the DMET self-consistency. T1 is an operator containing quadratic fermion terms (a†a, a†a†), while T2 contains quartic fermion terms (a†a†aa, a†a†a†a, a†a†a†a†, ⋯ ); the exponentiation allows T1 to capture disconnected fluctuations of individual particles, while T2 describes the connected fluctuations of pairs of particles. We can further classify T1 and T2 into components that produce different changes in the particle number: N (normal fluctuations which do not change particle number), and N ± 2, ± 4 (anomalous fluctuations). Figure 5A, shows the magnitude of the T1 and T2 components after DMET self-consistency. The fluctuations are largest at intermediate dopings, and the normal fluctuations are larger than the anomalous fluctuations.

A Norm of different blocks of coupled-cluster amplitudes (N: normal fluctuations, N ± 2, N ± 4 anomalous fluctuations). B Singular values of different T2 decompositions [spin conserving (ΔSz = 0) or spin fluctuating (ΔSz = ± 1)] in an ab initio cuprate calculation (CCO, ambient pressure); inset: T2 decomposition in the one-band Hubbard model plaquette DMET at U = 6). C Effect of the largest singular mode of T1 on the charge density n (red: n increase; blue: n decrease): charge shifts from oxygen to copper. D Effect of the largest singular mode of T2 (spin-conserving decomposition) on the charge density: charge shifts from Cu 3d to empty Cu orbitals (breathing) and to O. E Effect of the largest left, right singular modes of T2 (spin-fluctuating decomposition) on the spin density: the moments along the diagonal increase (red)/decrease (blue). F SC order (a residual SC associated with the lattice smearing temperature has been subtracted, see Section 3.3 of ref. 34) from different variants of solvers: CCSD includes all 4 classes of diagrams (not limited to those shown), ring CC contains direct and exchange ring terms, whereas direct-ring CC only contains the direct-ring terms.

To show the physical meaning of the T1 fluctuation, we visualize its effect in CCO (ambient pressure) on the charge density in Fig. 5C. The primary components of T1 are excitations between O 2p and Cu 3d orbitals, resulting in a shift of charge density from oxygen to copper. The effect of this correlation-stabilized fluctuation (i.e. it appears only in the presence of non-zero T2) is to make the copper-oxygen bond more covalent than expected in a simple mean-field treatment.

To see the physical meaning of the four-fermion T2 amplitude, we decompose it through a principal component analysis, similar to decompositions of the four-fermion (two-particle) Green’s functions58. We write \({T}_{2}={\sum }_{m}{w}_{m}{O}_{m}^{{{\dagger}} }{O}_{m}\), and then large weights wm denote dominant mode. Indeed, within a random phase approximation, the Om are bosonic operators, and if there is a dominant bosonic mode that is driving the superconducting instability, we would expect this to appear as a large singular value wm. Because T2 preserves Sz symmetry, we can carry out the decomposition into two channels: {Om} such that [Om, Sz] = 0 (spin-conserving channel), or [Om, Sz] = ± 1 (spin-fluctuation channel). Note that our T2 operator is in the Nambu representation, and the spin-conserving and spin-fluctuating channels contain both particle number preserving and particle number non-conserving Om.

Figure 5 B shows the ordered singular values in the spin-conserving and spin-fluctuating channels for CCO at ambient pressure. (For comparison, we show the same analysis for the DMET plaquette treatment of the 2D pure one-band Hubbard model at U = 6; as we are not allowing competition with stripe orders, the next nearest neighbor \(t^{\prime}\) is not critical here to stabilize a superconducting ground state18). The largest singular values are in the spin-fluctuating channel. There are similarities between the modes in CCO and in the one-band Hubbard model, in particular, we see 4 large singular values in the Sz ± 1 channel in both cases. However, the distribution is less peaked in the ab initio case, and the difference between the spin-conserving and spin-fluctuating channels is less pronounced. We visualize the dominant modes in Fig. 5D, E. In the spin-conserving channel, the first 4 fluctuations mainly involve charge redistribution from Cu 3d to other orbitals, principally, the oxygen 2p orbitals and Cu 4d (details in Table S5). These types of multi-orbital charge fluctuations, such as “breathing mode” 3d → 4d excitations59 and buffer layer excitations beyond the three-band in-plane orbitals of the cuprates, have previously been shown to be essential to capturing material-specific trends in the magnetism in the layer effect25. In the spin-fluctuating channel, the first 4 fluctuations flip the spin densities in the Cu 3\({d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) orbitals. They are primarily magnon excitation operators, formed from linear combinations of the 3d shell spin-flip operators on the Cu atoms with different phases (and are related to the low-lying triplet excitations in model studies of plaquettes60).

To connect these different kinds of fluctuations to the generation of pairing, we recompute the pairing order under different approximations in the CC many-body solver. In Fig. 5F we show 4 families of diagrams included in the CCSD solver (shown in the Nambu representation). The direct-ring diagrams lead only to charge fluctuations. The corresponding variant of the CC solver, which only includes the direct-ring diagrams, leads to no pairing order in CCO (ambient pressure) at least within our numerical resolution. (We have subtracted a small residual SC associated with our implementation of finite temperature smearing in the DMET lattice calculation, c.f. Sections 3.3 and 3.6 of ref. 34). The remaining diagrams in CCSD introduce spin fluctuations. For example, including the antisymmetrized, or exchange-ring diagrams (such diagrams vanish in the Hubbard model) adds a sub-class of spin-fluctuations: we see pairing begin to develop. Fig. S8 shows the contribution of only the ladder diagrams (which include different spin-fluctuations) to the SC order, which is of a similar magnitude to that from the full ring CCSD. The bulk of the pairing order emerges only when the coupling between ring and ladder diagrams, as contained in the full set of CCSD diagrams, is included. Overall the direct analysis confirms that short-range spin fluctuations drive the strength of the pairing order. However, in our fully ab initio microscopic picture, additional large fluctuations (such as breathing modes and charge redistribution) associated with covalency are also required, as they generate the energy scale of superexchange. This is an essential difference with low-energy 1-band representations.

Discussion

In this work, we have demonstrated a fully ab initio many-body simulation strategy that, starting from the material structure, directly approximates the solution of the electronic Schrödinger equation to obtain the superconducting pairing order across a range of geometries and compositions of cuprate materials. We note what is not yet contained within our current treatment: there are no phonons, or long-range spin or charge fluctuations (at distances much larger than the computational cell) and long wavelength orders, the treatment of doping does not include explicit dopants and the associated structural relaxation and disorder, nor are the solvers and representations numerically exact. Perhaps the simplest, but amongst the numerically most significant approximations, is the lack of charge self-consistency, which makes our calculations depend on the chosen starting point. (For a more detailed analysis of outstanding limitations, see Section 4 of ref. 34). Consequently, there remain important differences between the results of the simulations and observations in real materials. Nonetheless, our goal is not to reproduce all aspects of cuprate ground-state physics, but rather to capture some of the observed material trends. In this regard, we find that we obtain two trends in these materials: an increase in pairing order and pairing gap as a function of intralayer pressure; and an increase (and then decrease) in maximum pairing order and pairing gap as a function of the number of stacked copper-oxygen layers. These trends are highly reminiscent of similar trends that are experimentally seen in the superconducting critical temperatures. That these trends correctly appear indicates that the physics and numerical aspects of the calculation likely contain important and relevant ingredients to describe superconducting pairing in a material-specific manner across a range of cuprate compounds.

Detailed analysis of our calculations supports some long-standing proposals for the driving force for pairing in cuprates, but also provides new insights. Superexchange, suitably defined, correlates well with maximum pairing order, and short-range spin fluctuations, mainly on the copper atoms, drive the pairing. However, the ab initio picture of the fluctuations is richer than that in simplified models, because multi-orbital effects associated with covalency are needed to facilitate the spin fluctuations. Such multi-orbital processes are key to material-specific trends.

There is much room to systematically improve the computations in this work in the future. At the same time, we see our material-specific modeling of the superconducting ground-state as the starting point for a material-driven understanding of the full phase diagram; our atomically and orbitally resolved diagrammatic and fluctuation analysis as a route to elucidating the microscopic mechanisms underlying the phases; and the identification of central descriptors as aiding the computational search for new high-temperature superconducting materials. Importantly, our work shows that targetting a material-specific understanding of superconductivity in the cuprates is now a realistic goal through direct ab initio computation.

Data availability

Data used in this work are in the supplementary information.

Code availability

Codes used in this work can be found in the following repositories. The LIBDMET repository is at https://github.com/gkclab/libdmet_preview61. The BLOCK2 code repository is at https://github.com/block-hczhai/block2-preview. PYSCF is available from https://pyscf.org.

References

Plakida, N. High-temperature Cuprate Superconductors: Experiment, Theory, and Applications Vol. 166 (Springer Science & Business Media, 2010).

Norman, M. R. The challenge of unconventional superconductivity. Science 332, 196–200 (2011).

Mukuda, H., Shimizu, S., Iyo, A. & Kitaoka, Y. High-Tc superconductivity and antiferromagnetism in multilayered copper oxides—a new paradigm of superconducting mechanism. J. Phys. Soc. Japan 81, 011008 (2011).

Kurokawa, K. et al. Unveiling phase diagram of the lightly doped high-Tc cuprate superconductors with disorder removed. Nat. Commun. 14, 4064 (2023).

Gao, L. et al. Superconductivity up to 164 K in HgBa2Cam−1CumO2m+2+δ (m = 1, 2, and 3) under quasihydrostatic pressures. Phys. Rev. B 50, 4260 (1994).

Yamamoto, A., Takeshita, N., Terakura, C. & Tokura, Y. High pressure effects revisited for the cuprate superconductor family with highest critical temperature. Nat. Commun. 6, 8990 (2015).

Antipov, E., Abakumov, A. & Putilin, S. Chemistry and structure of Hg-based superconducting Cu mixed oxides. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 15, R31 (2002).

Dagotto, E. Complexity in strongly correlated electronic systems. Science 309, 257 – 262 (2005).

Oliveira, L. N. D., Gross, E. & Kohn, W. Density-functional theory for superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 60, 2430 (1988).

Lüders, M. et al. Ab initio theory of superconductivity. I. Density functional formalism and approximate functionals. Phys. Rev. B 72, 024545 (2005).

Qin, M., Schäfer, T., Andergassen, S., Corboz, P. & Gull, E. The Hubbard model: a computational perspective. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 13, 275–302 (2022).

Schmid, M. T., Morée, J.-B., Kaneko, R., Yamaji, Y. & Imada, M. Superconductivity studied by solving ab initio low-energy effective hamiltonians for carrier doped CaCuO2, Bi2Sr2CuO6, Bi2Sr2CaCu2O8, and HgBa2CuO4. Phys. Rev. X 13, 041036 (2023).

Zheng, B.-X. et al. Stripe order in the underdoped region of the two-dimensional Hubbard model. Science 358, 1155–1160 (2017).

Huang, E. W. et al. Numerical evidence of fluctuating stripes in the normal state of high-Tc cuprate superconductors. Science 358, 1161–1164 (2017).

Qin, M. et al. Absence of superconductivity in the pure two-dimensional Hubbard model. Phys. Rev. X 10, 031016 (2020).

Jiang, S., Scalapino, D. J. & White, S. R. Ground-state phase diagram of the t-\(t^{\prime}\)-J model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 118, e2109978118 (2021).

Mai, P. et al. Robust charge-density-wave correlations in the electron-doped single-band Hubbard model. Nat. Commun. 14, 2889 (2023).

Xu, H. et al. Coexistence of superconductivity with partially filled stripes in the Hubbard model. Science 384, eadh7691 (2024).

Kent, P. R. C. et al. Combined density functional and dynamical cluster quantum Monte Carlo calculations of the three-band Hubbard model for hole-doped cuprate superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 78, 035132 (2008).

Weber, C., Yee, C., Haule, K. & Kotliar, G. Scaling of the transition temperature of hole-doped cuprate superconductors with the charge-transfer energy. EPL 100, 37001 (2012).

Kowalski, N., Dash, S. S., Sémon, P., Sénéchal, D. & Tremblay, A.-M. Oxygen hole content, charge-transfer gap, covalency, and cuprate superconductivity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 118, e2106476118 (2021).

Wang, X., De’Medici, L., Park, H., Marianetti, C. & Millis, A. J. Covalency, double-counting, and the metal-insulator phase diagram in transition metal oxides. Phys. Rev. B 86, 195136 (2012).

Karp, J., Hampel, A. & Millis, A. J. Dependence of DFT + DMFT results on the construction of the correlated orbitals. Phys. Rev. B 103, 195101 (2021).

Jiang, S., Scalapino, D. J. & White, S. R. Density matrix renormalization group based downfolding of the three-band Hubbard model: Importance of density-assisted hopping. Phys. Rev. B 108, L161111 (2023).

Cui, Z.-H., Zhai, H., Zhang, X. & Chan, G. K.-L. Systematic electronic structure in the cuprate parent state from quantum many-body simulations. Science 377, 1192 (2022).

Knizia, G. & Chan, G. K.-L. Density matrix embedding: a simple alternative to dynamical mean-field theory. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 186404 (2012).

LeBlanc, J. P. F. et al. Solutions of the two-dimensional Hubbard model: Benchmarks and results from a wide range of numerical algorithms. Phys. Rev. X 5, 041041 (2015).

Cui, Z.-H. et al. Ground-state phase diagram of the three-band Hubbard model from density matrix embedding theory. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 043259 (2020).

Shavitt, I. & Bartlett, R. J. Many-Body Methods in Chemistry and Physics: MBPT and Coupled Cluster Theory (Cambridge University, 2009).

Chan, G. K.-L. & Sharma, S. The density matrix renormalization group in quantum chemistry. Ann. Rev. Phys. Chem. 62, 465–481 (2011).

Furness, J. W. et al. An accurate first-principles treatment of doping-dependent electronic structure of high-temperature cuprate superconductors. Commun. Phys. 1, 1–6 (2018).

Bellaiche, L. & Vanderbilt, D. Virtual crystal approximation revisited: application to dielectric and piezoelectric properties of perovskites. Phys. Rev. B 61, 7877 (2000).

Nambu, Y. Quasi-particles and gauge invariance in the theory of superconductivity. Phys. Rev. 117, 648–663 (1960).

See supplementary information for methods, computational details, additional data, and limitations of the work at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56883-x.

Azuma, M., Hiroi, Z., Takano, M., Bando, Y. & Takeda, Y. Superconductivity at 110 K in the infinite-layer compound \({({{{{\rm{Sr}}}}}_{1-x}{{{{\rm{Ca}}}}}_{x})}_{1-y}{{{{\rm{CuO}}}}}_{2}\). Nature 356, 775–776 (1992).

Hardy, F. et al. Enhancement of the critical temperature of HgBa2CuO4+δ by applying uniaxial and hydrostatic pressure: implications for a universal trend in cuprate superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 167002 (2010).

Huang, Q., Lynn, J., Xiong, Q. & Chu, C. Oxygen dependence of the crystal structure of HgBa2CuO4+δ and its relation to superconductivity. Phys. Rev. B 52, 462 (1995).

Radaelli, P. et al. Structure, doping and superconductivity in HgBa2CaCu2O6+δ (Tc ⩽ 128 K). Phys. C: Supercond. 216, 29–35 (1993).

Psaltakis, G. C. & Fenton, E. W. Superconductivity and spin-density waves: organic superconductors. J. Phys. C: Solid State Phys. 16, 3913 (1983).

Liang, R., Bonn, D. & Hardy, W. Evaluation of cuo2 plane hole doping in YBa2Cu3O6+x single crystals. Phys. Rev. B 73, 180505 (2006).

Yamamoto, A., Hu, W.-Z. & Tajima, S. Thermoelectric power and resistivity of HgBa2CuO4+δ over a wide doping range. Phys. Rev. B 63, 024504 (2000).

Zheng, B.-X. & Chan, G. K.-L. Ground-state phase diagram of the square lattice Hubbard model from density matrix embedding theory. Phys. Rev. B 93, 035126 (2016).

Kyung, B., Sénéchal, D. & Tremblay, A.-M. S. Pairing dynamics in strongly correlated superconductivity. Phys. Rev. B 80, 205109 (2009).

Wang, L. et al. Paramagnons and high-temperature superconductivity in a model family of cuprates. Nat. Commun. 13, 3163 (2022).

Anderson, P. W. The resonating valence bond state in La2CuO4 and superconductivity. Science 235, 1196–1198 (1987).

Zhang, F. C. & Rice, T. M. Effective Hamiltonian for the superconducting Cu oxides. Phys. Rev. B 37, 3759–3761 (1988).

Keren, A. Evidence of magnetic mechanism for cuprate superconductivity. New J. Phys. 11, 065006 (2009).

O’Mahony, S. M. et al. On the electron pairing mechanism of copper-oxide high temperature superconductivity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 119, e2207449119 (2022).

Rybicki, D., Jurkutat, M., Reichardt, S., Kapusta, C. & Haase, J. Perspective on the phase diagram of cuprate high-temperature superconductors. Nat. Commun. 7, 11413 (2016).

Varma, C. M. Theory of copper-oxide metals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 75, 898–901 (1995).

Weber, C., Haule, K. & Kotliar, G. Strength of correlations in electron-and hole-doped cuprates. Nat. Phys. 6, 574–578 (2010).

Vučičević, Jcv. & Ferrero, M. Simple predictors of Tc in superconducting cuprates and the role of interactions between effective Wannier orbitals in the d − p three-band model. Phys. Rev. B 109, L081115 (2024).

Tallon, J. L. The relationship between bond-valence sums and Tc in cuprate superconductors. Phys. C: Supercond. 168, 85–90 (1990).

Haase, J. A different NMR view of cuprate superconductors. J. Supercond. Nov. Magn. 35, 1753–1760 (2022).

Jurkutat, M. et al. How pressure enhances the critical temperature of superconductivity in YBa2Cu3O6+y. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 120, e2215458120 (2023).

Wang, Z. et al. Correlating the charge-transfer gap to the maximum transition temperature in Bi2Sr2Can−1CunO2n+4+δ. Science 381, 227–231 (2023).

Pavarini, E., Dasgupta, I., Saha-Dasgupta, T., Jepsen, O. & Andersen, O. Band-structure trend in hole-doped cuprates and correlation with \({T}_{{\rm{c}}\;{\rm{max}}}\). Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 047003 (2001).

Dong, X., Del Re, L., Toschi, A. & Gull, E. Mechanism of superconductivity in the Hubbard model at intermediate interaction strength. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 119, e2205048119 (2022).

Bogdanov, N. A., Li Manni, G., Sharma, S., Gunnarsson, O. & Alavi, A. Enhancement of superexchange due to synergetic breathing and hopping in corner-sharing cuprates. Nat. Phys. 18, 190–195 (2022).

Altman, E. & Auerbach, A. Plaquette boson-fermion model of cuprates. Phys. Rev. B 65, 104508 (2002).

Cui, Z.-H. libDMET: A library of quantum embedding theory for lattice models and realistic solids. https://github.com/gkclab/libdmet_preview (2025).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank David Reichman, Andrew Millis, Tianyu Zhu, Linqing Peng, Yuan Li, Patrick Lee, Steve White, Dingshun Lv, Lei Wang, Hong Jiang, Nai-Chang Yeh and Sandeep Sharma for helpful discussions. This work was primarily supported by the US Department of Energy, Office of Science, via grant no. DE-SC0018140. G.K.-L.C. is a Simons Investigator in Physics. Calculations were performed using the facilities of National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center (NERSC), a U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science User Facility located at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, under NERSC award ERCAP0023924, and in the Resnick High Performance Computing Center, supported by the Resnick Sustainability Institute at Caltech. We thank M. Graf and C. Mewes for arranging for computational time on NERSC. This work was partially supported by the National Science Foundation under Award No. CHE-1848369 (H.-Z.Y., development of Gaussian basis) and the Air Force Office of Scientific Research under Award No. FA9550-18-1-0095 (R. K., correlation potential fitting). L.L. is a Simons Investigator. J.T. acknowledges funding by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) through DFG-495279997.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.-H.C. and G.K.-L.C. designed the project. Z.-H.C., J.Y., J.T., and S.Y. carried out simulations. Z.-H.C. implemented the main algorithms for embedding, solvers, and analysis. J.Y. implemented the tailored CC solver. J.T. implemented the ring/ladder CC solver. H.-Z.Y. and T.C.B. designed the optimized Gaussian basis for solids. H.Z. implemented the DMRG algorithm for generalized spin orbitals. S.Y. and G.P. analyzed functional dependence, charge self-consistency, pairing gap, and Fermi surface. R.K. and L.L. helped with correlation potential fitting. X.Z. optimized the mean-field codes with symmetry. Z.-H.C. and G.K.-L.C. wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the discussion of results and editing of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

G.K.-L.C. is part owner of QSimulate, Inc. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Pierre-François Loos, who co-reviewed with Antoine Marie and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cui, ZH., Yang, J., Tölle, J. et al. Ab initio quantum many-body description of superconducting trends in the cuprates. Nat Commun 16, 1845 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56883-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56883-x

This article is cited by

-

Ab initio quantum many-body description of superconducting trends in the cuprates

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Electronic structure and superconducting properties of LaNiO2

Communications Physics (2025)