Abstract

Developing circularly polarized organic light-emitting diodes (CP-OLEDs) that simultaneously achieve narrow-spectrum emission and high electroluminescence (EL) efficiency remains a formidable challenge. This work prepares two pairs of efficient circularly polarized thermally activated delayed fluorescence (CP-TADF) materials, featuring high photoluminescence quantum yields, short delayed fluorescence lifetimes, good luminescence dissymmetry factors and large horizontal dipole ratios. They can function as emitters for efficient sky-blue CP-OLEDs, providing high maximum external quantum efficiencies (ηext,maxs) (33.8%) and good EL dissymmetry factors (gELs) (−2.64 × 10−3). More importantly, they can work as sensitizers for achiral multi-resonance (MR) TADF emitters, furnishing high-performance blue and green hyperfluorescence (HF) CP-OLEDs with intense narrow-spectrum CP-EL and good ηext,maxs (31.4%). Moreover, tandem HF CP-OLEDs are fabricated for the first time by employing CP-TADF sensitizers and achiral MR-TADF emitters, which radiate narrow-spectrum CP-EL with an extraordinary ηext,maxs (51.3%) and good gELs (4.87 × 10−3). The circularly polarized energy transfer as well as chirality-induced spin selectivity effect of CP-TADF sensitizers are considered to contribute greatly to the generation of efficient CP-EL from achiral MR-TADF emitters. This work not only explores efficient CP-TADF materials but also provides a facile approach to construct HF CP-OLEDs with achiral MR-TADF emitters.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Circularly polarized light has drawn extensive attention owing to the rich optical information and angle independence character, which has promising applications in a variety of frontier fields, including 3D displays, information encryption, quantum computing, light-emitting devices, optical communication for spintronics, and so on1,2,3,4. Current dominant methods for obtaining circularly polarized electroluminescence (CP-EL) generally involve manipulating nonpolarized light using a linear polarizer and a quarter-wave plate, which cause large loss in brightness and energy, as well as increased cost and cumbersome device structure5,6,7. In contrast, the direct generation of CP-EL from chiral materials in circularly polarized organic light-emitting diodes (CP-OLEDs) could be an efficient and feasible alternative for mitigating energy loss and simplifying device configuration8,9,10.

To construct efficient CP-OLEDs, exploring robust light-emitting materials with prominent circularly polarized luminescence (CPL) characteristics is of high importance. Purely organic thermally activated delayed fluorescence (TADF) materials are promising candidates for achieving theoretically 100% internal quantum efficiency through fast reverse intersystem crossing (RISC) process11. Current advancements have witnessed the successful design of a vast number of efficient TADF materials, furnishing high electroluminescence (EL) efficiencies and full-color lights in OLEDs12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20. Recently, circularly polarized TADF (CP-TADF) materials are emerging as a focal point in the fabrication of CP-OLEDs because these materials are able to directly generate right- or left-hand circularly polarized light with high exciton utilization efficiency, presenting a significant stride in the pursuit of cutting-edge technologies based on CP-OLEDs21,22,23.

In the design of efficient CP-TADF materials, there are two primary approaches commonly employed. The first approach involves inherent chirality of TADF molecules, which can yield large luminescence dissymmetry factors, but the produced enantiomers often require troublesome chiral separation24,25,26,27,28. The second approach is introducing chiral unit into a distorted donor–acceptor (D–A) structure that is responsible for generating TADF, on the basis of chiral perturbation mechanism. CP-TADF materials constructed by chiral perturbation strategy are typically synthesized by using commercially available enantiomers. This approach has gained increasing attention due to its simplicity in synthesis, high efficiencies, and tunable CPL colors29. However, this structural feature often leads to a wide energy distribution in the excited state due to the structural relaxation, which inevitably results in broad EL spectra and inferior color purity of CP-OLEDs30.

The burgeoning demand for ultra-high-resolution displays in industry has been accompanied by the introduction of new generation color gamut standard, BT.2020. This development has heightened researchers’ awareness of the crucial role played by color coordinates in display technology31. Addressing the pressing need for ultra-high-resolution displays underscores the critical importance of developing CP-OLEDs with high color purity. A pivotal breakthrough in this pursuit was pioneered by Hatakeyama et al. in 2016, who invented a novel design for narrow-spectrum TADF materials based on multiple resonance (MR) effect32,33,34,35,36,37,38. The reported MR-TADF emitters have exhibited noticeable merits of high EL efficiencies and high color quality, but the creation of efficient MR-TADF emitters with CPL property39,40,41,42 is still challenging because of difficult synthesis and complex isolation. Although great efforts have been devoted to the innovative molecular designs, the reported chiral MR-TADF emitters with high EL efficiencies and satisfactory EL dissymmetry factors (gELs) simultaneously are still rare43.

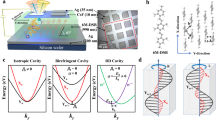

In this work, two pairs of efficient sky-blue CP-TADF materials are synthesized and characterized, and a simple yet effective strategy for constructing CP-OLEDs with good CP-EL performance, narrow emission spectra and high EL efficiencies is proposed. These CP-TADF materials have a twisted D–A framework consisting of a rigid electron acceptor of xanthone (XT) and a weak electron donor of spiro[acridine-9,9’-xanthene] (SXAC) or spiro[acridine-9,9’-fluorene] (SFAC) (Fig. 1a, b), which is responsible for generating delayed fluorescence. The rigid acceptor XT and acridine-based spiro donors are beneficial for reducing intramolecular motion and suppressing non-radiative decay of the excited states44. The spin-orbit coupling can be promoted by the n‒π* transition of the carbonyl group in XT as well, which is conducive to RISC process45,46,47,48,49,50,51. The acridine-based spiro donors can not only modulate emission color but also facilitate horizontal dipole orientation of the molecule. The stable chiral units (R/S)-octahydro-binaphthol ((R/S)-OBN) are introduced on XT acceptor to endow the whole molecule with CPL property via chiral perturbation effect. The doped CP-OLEDs prepared using these CP-TADF materials as emitters have strong CP-EL with good gELs (–2.64 × 10−3) and high maximum external quantum efficiencies (ηext,maxs) (33.8%). More importantly, these CP-TADF materials can serve as efficient sensitizers for commercially available achiral MR-TADF emitters, furnishing high-performance blue and green hyperfluorescence (HF) CP-OLEDs with narrow-spectrum CP-EL and good ηext,maxs (31.4%). In addition, blue and green tandem HF CP-OLEDs also realized, which not only achieve nearly twice the ηext,maxs (51.3%), but also improved gELs (4.87 × 10−3). The underlying sensitization mechanism that enables achiral MR-TADF emitters to radiate CP-EL is also elucidated. This work not only develop efficient CP-TADF emitters and sensitizers for CP-OLEDs, but also provides a facile and universal strategy to construct HF CP-OLEDs with achiral MR-TADF emitters and CP-TADF sensitizers, which can avoid the complicated synthesis and isolation of chiral MR-TADF emitters.

Results

Synthesis and characterization

The target CP-TADF materials, (R/S)-OBN-XT-SXAC and (R/S)-OBN-XT-SFAC, are successfully synthesized via the straightforward routes outlined in Supplementary Fig. 1, and their molecular structures are confirmed through rigorous analysis employing NMR, high-resolution mass spectrometry and X-ray single crystal diffraction (Supplementary data 1‒3). The crystal structures reveal a perfect mirror symmetry of (R/S)-enantiomers as exemplified by (R/S)-OBN-XT-SFAC (Supplementary Fig. 2). All the molecules adopt highly twisted conformations between XT acceptor and SFAC and SXAC donors, with large torsion angles in the range of 78.1°–89.9° (Fig. 1c‒e), which are favorable for the separated distribution of the highest occupied molecular orbitals (HOMOs) and the lowest unoccupied molecular orbitals (LUMOs). Besides, the presence of bulky spiro donors as well as nonplanar chiral (R/S)-OBN groups effectively discourage close packing of the molecules and weaken intermolecular π‒π interactions, which is conducive to suppressing emission quenching in aggregate state52,53,54,55,56. These CP-TADF materials have good thermal stability, as evidenced by the high decomposition temperatures in the range of 460–482 °C. No glass-transition signals are observed below 300 °C (Supplementary Fig. 3). The energy levels of HOMOs and LUMOs are determined by cyclic voltammetry (Supplementary Fig. 4). The results show that the HOMO and LUMO energy levels of (R/S)-enantiomers are basically identical, and (R)-OBN-XT-SXAC and (R)-OBN-XT-SFAC display HOMO and LUMO energy levels of −5.42/−2.87 eV and −5.41/−2.86 eV, respectively. In view of the identical property except for optical activity of (R/S)-enantiomers, the following investigations and discussions are mainly focused on (R)-OBN-XT-SXAC and (R)-OBN-XT-SFAC.

Theoretical calculations and analysis

The geometrical and electronic structures of (R)-OBN-XT-SXAC and (R)-OBN-XT-SFAC are simulated by theoretical calculation (Fig. 1f, g). The optimized molecular structures show that (R)-OBN-XT-SXAC and (R)-OBN-XT-SFAC have twisted molecular skeletons with torsional angles closely resembling those observed in crystal structures. In consequence, they hold separated distribution of HOMOs and LUMOs, in which the HOMOs are primarily localized on SXAC and SFAC donors, while the LUMOs are concentrated on XT acceptor. The chiral (R)-OBN groups barely contribute to HOMOs and LUMOs. Theoretical calculations also uncover small energy splitting (ΔEST) values between the lowest excited singlet (S1) and triplet (T1) states of 0.017 and 0.016 eV for (R)-OBN-XT-SXAC and (R)-OBN-XT-SFAC, respectively, which meet the prerequisite for the occurrence of RISC process. Meanwhile, the natural transition orbital (NTO) analysis reveals that, for the S1 states of these molecules, the highest occupied natural transition orbitals (HONTOs) are located on SXAC and SFAC donors, while the lowest unoccupied natural transition orbitals (LUNTOs) are mainly distributed on XT acceptor (Supplementary Fig. 5). The S1 states are mainly dominated by the typical charge transfer (CT) state (about 95%). For the T1 states, the HONTOs are partially distributed on XT acceptor besides SXAC and SFAC donors, which increases the locally excited component. The different transition characteristics between S1 and T1 states are beneficial for the occurrence of fast RISC process as well.

Thermally activated delayed fluorescence

As shown in Fig. 2a, (R)-OBN-XT-SXAC and (R)-OBN-XT-SFAC show similar absorption bands below 370 nm in toluene solutions, which are mainly ascribed to the π–π* transitions. Almost identical absorption bands with peaks at 395 nm and absorption tails extending to 440 nm are observed for both molecules, which stem from intramolecular CT from SFAC and SXAC donors to XT acceptor. (R)-OBN-XT-SXAC and (R)-OBN-XT-SFAC display sky-blue photoluminescence (PL) emissions peaking at 477 and 487 nm, accompanied by high PL quantum efficiencies (ΦPLs) of 77% and 78%, respectively (Supplementary Table 1). The weaker electron-donating ability of SXAC relative to SFAC results in weakened CT effect, accounting for the bluer emission of (R)-OBN-XT-SXAC than (R)-OBN-XT-SFAC. These materials display prominent delayed component with short lifetimes (τDF) of ~1.2 µs in oxygen-free toluene solutions (Supplementary Fig. 6 and Supplementary Table 2).

a UV-vis absorption spectra and PL spectra of (R)-OBN-XT-SXAC and (R)-OBN-XT-SFAC in toluene solutions (1 × 10‒5 M). b PL spectra of (R)-OBN-XT-SXAC and (R)-OBN-XT-SFAC in neat films and doped films (20 wt% in PPF). c Temperature-dependent transient PL decay spectra of (R)-OBN-XT-SXAC in neat film, measured under nitrogen. d CD spectra of (R/S)-OBN-XT-SXAC and (R/S)-OBN-XT-SFAC in toluene solutions (1 × 10‒4 M). CPL spectra of (R/S)-OBN-XT-SXAC and (R/S)-OBN-XT-SFAC in (e) neat films and (f) doped films (20 wt% in PPF). g gPL values of (R/S)-OBN-XT-SXAC and (R/S)-OBN-XT-SFAC at their related PL peaks in toluene solutions (1.0 × 10−4 M), neat films and doped films (20 wt% in PPF). Plots of gPL versus PL wavelength of (R/S)-OBN-XT-SXAC and (R/S)-OBN-XT-SFAC in (h) neat films and (i) doped films (20 wt% in PPF).

Subsequently, the PL properties of (R)-OBN-XT-SXAC and (R)-OBN-XT-SFAC in film state are studied. In neat films, (R)-OBN-XT-SXAC and (R)-OBN-XT-SFAC exhibit sky-blue PL emissions with peaks at 486 and 492 nm, respectively, which are slightly red-shifted by less than 10 nm compared with the PL peaks in toluene solutions. They have good ΦPLs of 79% and 80%, and short τDFs of 1.4 and 1.1 μs, similar to those in solutions, indicating they are free of aggregation-caused quenching. When doped in polar host 2,8-bis(diphenylphosphoryl)dibenzo[b,d]furan (PPF) at a concentration of 20 wt%, (R)-OBN-XT-SXAC and (R)-OBN-XT-SFAC show PL peaks at 494 and 497 nm, short τDFs of 1.6 and 1.4 μs, and remarkable ΦPLs reaching 98% and 99%, respectively (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Table 1). The short τDF values, less than 1.6 μs, indicate fast RISC processes from T1 to S1 states. The temperature-dependent transient PL decay spectra disclose apparent enhancements in the proportion of delayed fluorescence as the temperature increases from 77 to 300 K (Fig. 2c, Supplementary Fig. 7 and Supplementary Table 3). Such behaviors align with the characteristic of typical TADF materials, in which delayed fluorescence is promoted by the accelerated RISC process at high temperatures.

To evaluate the practical ΔEST values of (R)-OBN-XT-SXAC and (R)-OBN-XT-SFAC, the fluorescence and phosphorescence spectra of the films are measured at 77 K (Supplementary Fig. 8). The experimental ΔEST values of (R)-OBN-XT-SXAC and (R)-OBN-XT-SFAC are as small as 0.018 and 0.024 eV in neat films, and 0.013 and 0.015 eV in doped films, respectively, well consistent with the theoretical data discussed above. Based on the photophysical data, the fluorescence radiative decay rate constants (krs) of (R)-OBN-XT-SXAC and (R)-OBN-XT-SFAC are calculated as high as 1.7 × 107 and 2.0 × 107 s‒1 in neat films, and 1.0 × 107 and 1.7 × 107 s‒1 in doped films, respectively (Supplementary Table 1). These values surpass the internal conversion rate constants (kICs) of 4.6 × 106 s‒1 in neat film and 1.0 × 105 s‒1 in doped film for (R)-OBN-XT-SXAC, and 4.9 × 106 s‒1 in neat film and 2.0 × 105 s‒1 in doped film for (R)-OBN-XT-SFAC, indicative of reduced nonradiative energy loss. Besides, (R)-OBN-XT-SXAC shows fast kRISCs of 1.2 × 106 s‒1 in neat film and 1.6 × 106 s‒1 in doped film. Similarly, (R)-OBN-XT-SFAC also has comparable kRISCs of 1.2 × 106 s‒1 in neat film and 1.4 × 106 s‒1 in doped film. The fast RISC processes of these materials are highly conducive to suppressing triplet-triplet annihilation and thus reducing efficiency roll-offs.

Circularly polarized luminescence

The chiroptical properties of (R/S)-OBN-XT-SXAC and (R/S)-OBN-XT-SFAC are investigated at both ground and excited states by circular dichroism (CD) and CPL spectra, respectively. As shown in Fig. 2d, the (R/S)-enantiomers display obvious mirror-image CD spectra with strong Cotton effects in toluene solutions. Notably, the strong Cotton effects detected at around 307 nm correspond to the characteristic absorption of the chiral OBN unit, while obvious Cotton effects in the range of 330–430 nm may belong to the absorption of the D–A frameworks. These findings indicate the achiral D–A frameworks responsible for delayed fluorescence have been successfully induced to display optical activity by chiral (R/S)-OBN units in ground state. On the other hand, mirror-image CPL signals are recorded for (R/S)-enantiomers, further validating their chiroptical property in excited state. The PL dissymmetry factors (gPLs) of (R/S)-OBN-XT-SXAC and (R/S)-OBN-XT-SFAC are 3.77 × 10−4/−3.52 × 10−4 and 4.41 × 10−4/−5.17 × 10−4 in toluene solutions, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 9). In film states, (R/S)-enantiomers exhibit enhanced CPL behaviors (Fig. 2e−i), with greatly improved CPL signals. The measured gPLs are 2.95 × 10−3/−2.71 × 10−3 for (R/S)-OBN-XT-SXAC in neat film, and 1.51 × 10−3/−1.49 × 10−3 in doped film. The gPLs are 3.04 × 10−3/−3.06 × 10−3 for (R/S)-OBN-XT-SFAC in neat film, and 1.31 × 10−3/−1.56 × 10−3 in doped film. Clearly, the gPLs in film state are much larger than those in solution state. This is because the vigorous intramolecular motion in solution state can make the chiral conformation of the molecule unstable, resulting in a relatively weak CPL signal. However, in film state, the intramolecular motion is greatly restricted, and the chiral conformation can be better stabilized, accounting for the larger gPLs than that in solution state.

Circularly polarized electroluminescence

Concerning the efficient CP-TADF properties, these chiral materials are employed as emitters to fabricate CP-OLEDs with the configuration of ITO/HATCN (5 nm)/TAPC (50 nm)/TcTa (5 nm)/mCP (5 nm)/EML (20 nm)/PPF (5 nm)/TmPyPB (40 nm)/LiF (1 nm)/Al, in which the doped films of (R/S)-OBN-XT-SXAC and (R/S)-OBN-XT-SFAC with the doping concentrations of 10, 20 and 30 wt% in PPF host work as emitting layers (EMLs). Hexaazatriphenylenehexacabonitrile (HATCN), 1,1-bis(4-bis(4-methylphenyl)aminophenyl)c-yclohexane (TAPC) and PPF act as hole injection, hole-transporting and hole-blocking layers, respectively. Tris(4-(carbazol-9-yl)phenyl)amine (TcTa), 1,3-di(carbazol-9-yl)benzene (mCP) and 1,3,5-tri(m-pyrid-3-yl-phenyl)benzene (TmPyPB) function as exciton-blocking, electron-blocking and electron-transporting layers, respectively. The molecular structures of the used functional materials, along with the energy level diagrams of the device architectures, are illustrated in Fig. 3a, b. All the devices can be turned on at low voltages of 2.7–3.3 V and radiate strong sky-blue lights (Table 1). By increasing doping concentration from 10 to 30 wt% in PPF host, the EL peaks are slightly red-shifted, the luminance is enhanced apparently, and the efficiency roll-offs become reduced progressively. At 20% doping concentration, these doped devices show the highest EL efficiencies. The OLEDs based on (R)-OBN-XT-SXAC and (R)-OBN-XT-SFAC exhibit EL peaks at 496 nm (CIEx,y = 0.19, 0.43) and 504 nm (CIEx,y = 0.21, 0.48) and maximum luminance (Lmax) of 10100 and 8599 cd m−2, respectively, and attain remarkable EL efficiencies of maximum current efficiencies (ηc,maxs) of 86.7 and 94.5 cd A−1, maximum power efficiencies (ηp,maxs) of 92.6 and 98.4 lm W−1 and ηext,maxs of 33.4% and 33.7%, respectively (Fig. 3c, d, Supplementary Fig. 10). All the (S)-enantiomers show similar EL performances to the (R)-enantiomers (Supplementary Fig. 11, Supplementary Fig. 12). For example, at 20 wt % doping concentration, the devices of (S)-OBN-XT-SXAC and (S)-OBN-XT-SFAC provide ηc,maxs of 83.7 cd A−1 and 96.4 cd A−1, ηp,maxs of 87.7 and 101.0 lm W−1 and ηext,maxs of 31.7% and 33.8%, respectively. Owing to the good CPL nature of these CP-TADF materials, their devices display mirror-image CP-EL spectra with good gELs ranging from −2.64 × 10−3 to 2.35 × 10−3 (Fig. 3e, f, Supplementary Fig. 13), which are comparable to the reported gELs for high-efficiency CP-OLEDs57,58,59,60,61,62. These results underscore the good CP-EL performances of these CP-TADF materials.

a Configuration, energy levels and (b) chemical structures of functional layers of the doped devices based on (R/S)-OBN-XT-SXAC and (R/S)-OBN-XT-SFAC. EML is the doped film of 10, 20 and 30 wt% (R/S)-OBN-XT-SXAC or (R/S)-OBN-XT-SFAC in PPF host. c EL spectra, external quantum efficiency–luminance (The insert show the photo of the device with 20 wt% doping concentration) and (d) plots of luminance–voltage–current density of the OLEDs based on (R)-OBN-XT-SXAC. The doped OLEDs are fabricated with different (R)-OBN-XT-SXAC doping concentration in PPF host. e CP-EL spectra and (f) plots of gEL versus EL wavelength of doped OLEDs of (R/S)-OBN-XT-SXAC. The doping concentration is 20 wt%.

In view of the ηext,maxs exceeding 30%, the emitting dipole orientation behaviors of these CP-TADF materials in 20 wt% doped films are investigated by angle-dependent p-polarized PL spectra (Supplementary Fig. 14). They exhibit high ratios of horizontal emitting dipole (Θ//s) in the range of 86.5%‒88.5%, which should be attributed to the presence of spiro SFAC and SXAC donors63,64,65,66,67,68. By combining reflex index and active layer thickness, the corresponding outcoupling efficiencies (ηouts) of the doped devices are calculated as high as 39.0%‒40.8%, which should significantly contribute to the high ηext,maxs.

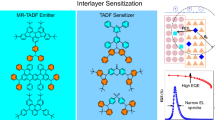

Hyperfluorescence circularly polarized OLEDs

Although these CP-TADF materials hold high EL efficiencies in CP-OLEDs, their EL spectra are actually broad because of the intrinsic TADF nature. To improve color quality of the devices, HF CP-OLEDs are fabricated using these CP-TADF as sensitizers to sensitize MR-TADF emitters featuring narrow emission spectra (Fig. 4a, b). The commercial achiral blue MR-TADF emitter, v-DABNA, whose absorption spectrum overlaps well with the PL spectra of (R/S)-OBN-XT-SXAC, is employed in this study (Fig. 4c, d). It is envisioned that efficient circularly polarized fluorescence resonance energy transfer (CP-FRET) process can occur from (R/S)-OBN-XT-SXAC sensitizers to achiral MR-TADF emitter, bringing about narrow-spectrum CP-EL emissions69,70,71. The co-phase sensitized HF device with (R)-OBN-XT-SXAC sensitizer and v-DABNA emitter is constructed with the configuration of ITO/HATCN (5 nm)/TAPC (50 nm)/TcTa (5 nm)/mCP (5 nm)/0.5 wt% v-DABNA: 20 wt% (R)-OBN-XT-SXAC: mCBP (20 nm)/PPF (5 nm)/TmPyPB (40 nm)/LiF (1 nm)/Al (device (R)-HF1), in which 3,3’-di(9H-carbazol-9-yl)-1,1’-biphenyl (mCBP) is used as host for v-DABNA and (R)-OBN-XT-SXAC. As shown in Fig. 4e−h and Table 2, device (R)-HF1 shows intense high-purity blue light with a sharp EL peak at 470 nm and a narrow FWHM of 20 nm, and the narrow EL spectrum renders a saturated blue light (CIEx,y = 0.13, 0.18). In addition, device (R)-HF1 achieves good EL performances with a large Lmax of 21160 cd m−2, and a high ηext,max of 28.5 %. More importantly, a distinct CP-EL signal with a gEL of 2.93 × 10−3 is recorded at the EL peak position (470 nm) for device (R)-HF1, and the repeated devices of (R)-HF1 confirm the good reproducibility of CP-EL signals (Supplementary Fig. 15). Moreover, device (S)-HF1 containing the emittng layer of 0.5 wt% v-DABNA: 20 wt% (S)-OBN-XT-SXAC: mCBP (20 nm) exhibits EL performance similar to device (R)-HF1, with an ηext,max of 27.8 % and a gEL of −2.96 × 10−3 (Supplementary Fig. 16 and Supplementary Table 4). These findings reveal that the achiral MR-TADF emitter v-DABNA has been successfully sensitized to radiate strong CP-EL with good EL efficiencies.

Device configurations of (a) blue and (b) green HF CP-OLEDs and (c) molecular structures of v-DABNA and BN2. d Absorption spectra of v-DABNA and BN2 and PL spectra of (R)-OBN-XT-SXAC and (R)-OBN-XT-SFAC in toluene solutions (concentration: 1.0 × 10−5 M). e EL spectra, (f) luminance–voltage–current density curves, (g) external quantum efficiency–luminance curves, and (h, i) CP-EL spectra and plots of gEL versus EL wavelength of blue (device (R)-HF1) and green (device (R)-HF2) co-phase sensitized HF CP-OLEDs using (R)-OBN-XT-SXAC and (R)-OBN-XT-SFAC as sensitizers and v-DABNA and BN2 as emitters. Inserts in plane (e): photos of blue and green HF CP-OLEDs.

To dig into the potential of these CP-TADF materials as sensitizers, more HF CP-OLEDs using (R/S)-OBN-XT-SFAC as sensitizers for achiral green MR-TADF emitter BN2 are further fabricated, with the configurations of ITO/HATCN (5 nm)/TAPC (50 nm)/TcTa (5 nm)/mCP (5 nm)/1 wt% BN2: 20 wt% (R/S)-OBN-XT-SFAC: CBP (20 nm)/TmPyPB (40 nm)/LiF (1 nm)/Al (devices (R/S)-HF2), where 4,4′-bis(N-carbazolyl)-1,1′-biphenyl (CBP) works as host for BN2 and (R/S)-OBN-XT-SFAC. The device (R)-HF2 based on (R)-OBN-XT-SFAC has a green EL peak at 542 nm (CIEx,y = 0.32, 0.64) with a narrow FWHM of 42 nm, and provides Lmax, ηext,max, ηc,max and ηp,max of 10710 cd m−2, 31.4%, 133.7 cd A−1 and 144.8 lm W−1, respectively. It also displays clear and repeatable CP-EL signals with gELs in the range of 1.31 × 10−3–1.44 × 10−3 in the repeated devices of (R)-HF2 (Fig. 4e−g and i, Supplementary Fig. 15). The device (S)-HF2 based on (S)-OBN-XT-SFAC shows similar EL performances with a good ηext,max of 30.7% and a gEL of –1.46 × 10−3 (Supplementary Fig. 16 and Supplementary Table 4). Notably, (R/S)-OBN-XT-SXAC and (R/S)-OBN-XT-SFAC in this work are comparable to or even outperform many reported achiral TADF sensitizers for v-DABNA and BN2 (Supplementary Table 5), highlighting that these CP-TADF materials are promising sensitizers for MR-TADF emitters in the fabrication of HF CP-OLEDs72,73,74,75,76,77.

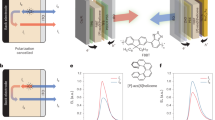

Circularly polarized sensitization mechanism

In these HF CP-OLEDs, the chiral sensitizers and achiral emitters are co-doped into one host layer, and the generation of CP-EL from achiral emitter may be caused by the chirality induction effect from the chiral environment of the adjacent chiral molecules78,79,80,81. But current researches suggest that the CP-FRET69,70,71 effect could play a critical role in the generation of CP-EL from achiral emitters. In order to figure this out, supplementary HF CP-OLEDs on the basis of interlayer sensitization strategy82,83 are prepared, with the configurations of ITO/HATCN (5 nm)/TAPC (50 nm)/TcTa (5 nm)/mCP (5 nm)/0.5 wt% v-DABNA: mCBP (10 nm)/20 wt% (R/S)-OBN-XT-SXAC: PPF (1 nm)/PPF (5 nm)/TmPyPB (40 nm)/LiF (1 nm)/Al (devices (R/S)-HF3) (Fig. 5a, b). Unlike devices (R/S)-HF1, devices (R/S)-HF3 have the chiral sensitizer and achiral emitter doped into two separated host layers to avoid chirality induction effect. According to energy level diagram, in devices (R/S)-HF3, a large part of excitons will be formed in the sensitizing layer containing (R/S)-OBN-XT-SXAC. Since the degree of FRET is closely related to the spatial distance between the donor and acceptor molecules, the thickness of sensitizing layer is kept as thin as possible in order to ensure sufficient energy transfer. Delightfully, device (R)-HF3 based on (R)-OBN-XT-SXAC also radiates strong blue light with an EL peak at 470 nm and a narrow FWHM of 20 nm, and achieves a ηext,max as high as 28.0%. Meanwhile, prominent CP-EL signals with gELs in the range of 1.25 × 10−3–1.55 × 10−3 are observed in different batches of device (R)-HF3, which are comparable to those obtained in device (R)-HF1 (Fig. 5c−e, Supplementary Fig. 17 and Table 2). Similarly, a high ηext,max of 27.4% and a good gEL value of –1.45 × 10−3 are attained by device (S)-HF3 based on (S)-OBN-XT-SXAC (Supplementary Fig. 18 and Supplementary Table 4). By gradually increasing the thickness of (R)-OBN-XT-SXAC-containing layer from 1 nm to 5 nm, the resultant devices have the comparable EL efficiencies with noticeable CP-EL signals, but the EL spectrum becomes broader at 5 nm (Supplementary Table 6), probably due to the incomplete energy transfer from (R)-OBN-XT-SXAC to v-DABNA. The apparent CP-EL signals from achiral v-DABNA in interlayer-sensitizing configuration suggest that one of the possible working mechanisms could be CP-FRET process rather than chirality induction.

a Configurations, energy level diagrams and b EMLs of devices (R)-HF3, (R)-HF4, (R)-HF5 and (R)-HF6. c EL spectra and external quantum efficiency–luminance, (d) plots of luminance–voltage–current density, (e, f) CP-EL spectra and plots of gEL versus EL wavelength of the blue (device (R)-HF3) and green (device (R)-HF5) interlayer-sensitized HF CP-OLEDs using (R)-OBN-XT-SXAC and (R)-OBN-XT-SFAC as sensitizers and v-DABNA and BN2 as emitters.

On the other hand, according to recent reports, the chirality-induced spin selectivity (CISS) effect84,85,86,87, which refers to the spin polarization of charge carriers after passing through the chiral molecules in device, may also contribute to the appearance of CP-EL signals from achiral v-DABNA. In devices (R/S)-HF3, some spin-polarized charge carriers may be formed when current passes through chiral (R/S)-OBN-XT-SXAC molecules and get recombined in achiral v-DABNA to radiate narrow-spectrum EL emission with CP-EL signal. To confirm whether CISS effect can function in sensitizing achiral v-DABNA to produce CP-EL signal, the control HF CP-OLEDs are fabricated with the configuration of ITO/HATCN (5 nm)/TAPC (50 nm)/TcTa (5 nm)/mCP (5 nm)/20 wt% (R/S)-OBN-XT-SXAC: PPF (1 nm)/0.5 wt% v-DABNA: mCBP (10 nm)/PPF (5 nm)/TmPyPB (40 nm)/LiF (1 nm)/Al (devices (R/S)-HF4) (Fig. 5a, b). In devices (R/S)-HF4, the positions of sensitizing layer and emitting layer are switched in comparison with those in device (R/S)-HF3. In that case, spin-polarized charge carrier can be formed when the current passes through the thin sensitizing layer containing (R/S)-OBN-XT-SXAC, parts of which can get recombined directly in emitting layer containing v-DABNA to produce CP-EL. As expected, device (R)-HF4 shows similar EL performance as device (R)-HF3, with an even bluer and narrower EL spectrum and a higher ηext,max of 29.1% (Supplementary Fig. 19 and Table 2). And pronounced CP-EL signal with a gEL of 1.59 × 10−3 is recorded in device (R)-HF4 (Supplementary Fig. 17). This interesting phenomenon can also be observed in device (S)-HF4, which has a ηext,max of 28.1% and a gEL value of –1.57 × 10−3 (Supplementary Fig. 20 and Supplementary Table 4). Moreover, when the emiting layer is sandwiched by two sensitizing layers with the same chirality in the device of ITO/HATCN (5 nm)/TAPC (50 nm)/TcTa (5 nm)/mCP (5 nm)/EML/PPF (5 nm)/TmPyPB (40 nm)/LiF (1 nm)/Al, in which the EML consists of 20 wt% (R)-OBN-XT-SXAC: PPF (1 nm)/0.5 wt% v-DABNA: mCBP (10 nm)/20 wt% (R)-OBN-XT-SXAC: PPF (1 nm), or 20 wt% (S)-OBN-XT-SXAC: PPF (1 nm)/0.5 wt% v-DABNA: mCBP (10 nm)/20 wt% (S)-OBN-XT-SXAC: PPF (1 nm), similar CP-EL signals can still be observed for the devices (Supplementary Fig. 21 and Supplementary Table 7). But when the emiting layer is sandwiched by two sensitizing layers with the opposite chirality, in which the EML is composed by 20 wt% (R)-OBN-XT-SXAC: PPF (1 nm)/0.5 wt% v-DABNA: mCBP (10 nm)/20 wt% (S)-OBN-XT-SXAC: PPF (1 nm), the CP-EL signals are greatly weakened and almost indistinguishable, which is probably due to the offset of the oppositely spin-polarized charge carriers. These results demonstrate the CISS effect can contribute to enabling achiral MR-TADF emitter to emit CP-EL by CP-TADF sensitizers.

To further validate the sensitization mechanism, more supplementary HF CP-OLEDs ((R/S)-HF5 and (R/S)-HF6) based on interlayer sensitization strategy are fabricated, using (R/S)-OBN-XT-SFAC as sensitizers for BN2 emitter. The configuration of devices (R/S)-HF5 is ITO/HATCN (5 nm)/TAPC (50 nm)/TcTa (5 nm)/mCP (5 nm)/1 wt% BN2: CBP (10 nm)/20 wt% (R/S)-OBN-XT-SFAC: PPF (1 nm)/TmPyPB (40 nm)/LiF (1 nm)/Al, while that of devices (R/S)-HF6 is ITO/HATCN (5 nm)/TAPC (50 nm)/TcTa (5 nm)/mCP (5 nm)/ 20 wt% (R/S)-OBN-XT-SFAC: PPF (1 nm)/1 wt% BN2: CBP (10 nm)/TmPyPB (40 nm)/LiF (1 nm)/Al (Fig. 5a, b). Device (R)-HF5 also demonstrates CP-EL performance, with an EL peak at 540 nm (CIEx,y = 0.30, 0.63), a narrow FWHM of 42 nm, and gELs of 1.19 × 10−3–1.36 × 10−3 in the repeated devices of (R)-HF5. And good EL efficiencies of a ηext,max of 24.9%, a ηc,max of 103.0 cd A−1, and a ηp,max of 106.2 lm W−1 are also attained by the device (Fig. 5, Supplementary Fig. 22 and Table 2). Consistent with the blue HF devices, green HF devices with different thickness of (R)-OBN-XT-SFAC-containing layer also have stable EL efficiencies and noticeable CP-EL signals, while the EL spectrum becomes wide when the thickness of (R)-OBN-XT-SFAC-containing layer is increased to 5 nm because of incomplete energy transfer (Supplementary Table 8). Device (R)-HF6 also exhibits efficient CP-EL with slightly improved EL performances and a good gEL of 1.24 × 10−3 (Supplementary Fig. 19, Supplementary Fig. 22 and Table 2). Besides, the interlayer-sensitized devices (S)- HF5 and (S)-HF6 based on (S)-OBN-XT-SFAC show similar CP-EL performances as devices (R)-HF5 and (R)-HF6 (Supplementary Fig. 18, Supplementary Fig. 20 and Supplementary Table 4). The pronounced CP-EL signals from achiral BN2 provide evidences for that CISS effect could be another possible sensitization mechanism besides CP-FRET.

In short, the results of these HF CP-OLEDs validate the effectiveness of the developed CP-TADF materials as sensitizers for achiral MR-TADF emitters, furnishing high-performance CP-OLEDs with narrow-spectrum EL emissions, high EL efficiencies, and good gELs. The apparent CL-EL signals from achiral v-DABNA and BN2 in interlayer-sensitizing configuration demonstrate the dominant contributions from CISS and/or CP-FRET effects rather than chirality induction mechanism.

Tandem hyperfluorescence circularly polarized OLEDs

Tandem OLEDs (TOLEDs) meet the requirements of various display applications owing to their apparently enhanced luminance, efficiency and lifetime relative to single-unit device88,89. But for HF CP-OLEDs, the tandem devices are rarely reported in the literature, making it difficult to assess the influence of the tandem configuration on the CP-EL property, such as gELs. Since the tandem configuration has greatly increased numbers of functional layers, it is natural to assume that the CP lights generated from the emitting layers may partially become non-polarized when passing through these layers or experiencing refraction and reflection within the device, leading to decreased gELs. To address this issue, herein, tandem HF CP-OLEDs employing (R/S)-OBN-XT-SXAC and (R/S)-OBN-XT-SFAC as sensitizers and v-DABNA and BN2 as emitters are constructed. Concerning that in tandem configuration, the charge generation unit (CGU) has a decisive impact on the device performance88,89, a series of single CGU devices based on different electron-transporting layers (ETLs) are initially evaluated, with the configuration of ITO/ETL (40 nm)/LiF (0.3 nm)/Al (1 nm)/HATCN (10 nm)/TAPC (50 nm)/Al. Four commonly used electron-transporting materials, including PPF, 4,7-diphenyl-1,10-phenanthroline (Bphen), 1,3,5-tris(1-phenyl-1Hbenzimidazol-2-yl)benzene (TPBi) and TmPyPB, are selected to work as ETL, and Bphen is finally determined as ETL because of its lower LUMO energy level (−3.0 eV) than PPF, TPBi and TmPyPB (~2.7 eV)90, which makes the electron injection energy barrier smaller and ensure higher current density (Supplementary Fig. 23).

Subsequently, the blue tandem HF CP-OLEDs are optimized to the configuration of ITO/HATCN (5 nm)/TAPC (50 nm)/TcTa (5 nm)/mCP (5 nm)/0.5 wt% v-DABNA: 20 wt% (R/S)-OBN-XT-SXAC: mCBP (20 nm)/PPF (5 nm)/Bphen (40 nm)/LiF (0.3 nm)/Al (1 nm)/HATCN (10 nm)/TAPC (60 nm)/TcTa (5 nm)/mCP (5 nm)/0.5 wt% v-DABNA: 20 wt% (R/S)-OBN-XT-SXAC: mCBP (20 nm)/PPF (5 nm)/Bphen (40 nm)/LiF (1 nm)/Al (devices (R/S)-T-HF1) (Fig. 6a). Successfully, the tandem device (R)-T-HF1 radiates intense blue light with an EL peak at 470 nm (CIEx,y = 0.13, 0.19) and a narrow FWHM of 20 nm, consistent with those in single-unit device (R)-HF1, but attains boosted EL performances with a large Lmax of 16140 cd m‒2 and a high ηext,max of 50.9% (Fig. 6b−d and Table 2). Also, the EL performance of device (R)-T-HF1 is better than those of previously reported devices of v-DABNA (Supplementary Table 5)72,73,74. More importantly, tandem device (R)-T-HF1 maintains a distinct CP-EL signal with an enhanced gEL of 4.87 × 10−3 relative to that of single-unit device (R)-HF1 (2.93 × 10−3) (Fig. 6e). The repeated devices of (R)-T-HF1 show the similar results, indicative of good reproducibility (Supplementary Fig. 24). Another tandem HF CP-OLED (device (S)-T-HF1) based on (S)-OBN-XT-SXAC obtained good CP-EL performance as well, with a remarkable ηext,max of 50.6% and a good gEL value of −4.89 × 10−3 (Supplementary Fig. 25 and Supplementary Table 4).

a Device structure of tandem HF CP-OLEDs. EMLs of blue and green tandem HF CP-OLEDs are 0.5 wt% v-DABNA: 20 wt% (R)-OBN-XT-SXAC: mCBP (20 nm) (device (R)-T-HF1) and 1 wt% BN2: 20 wt% (R)-OBN-XT-SFAC: CBP (20 nm) (device (R)-T-HF2), respectively. b EL spectra, (c) external quantum efficiency–luminance, (d) plots of luminance–voltage–current density, (e, f) CP-EL spectra and plots of gEL versus EL wavelength of the blue (device (R)-T-HF1) and green (device (R)-T-HF2) tandem HF CP-OLEDs using (R)-OBN-XT-SXAC and (R)-OBN-XT-SFAC as sensitizers and v-DABNA and BN2 as emitters.

In order to further clarify the influence of the tandem configuration on CP-EL and verify the universality of the sensitization strategy, green tandem HF CP-OLEDs are also fabricated and investigated. The optimized device configuration is ITO/HATCN (5 nm)/TAPC (50 nm)/TcTa (5 nm)/mCP (5 nm)/1 wt% BN2: 20 wt% (R/S)-OBN-XT-SFAC: CBP (20 nm)/Bphen (40 nm)/LiF (0.3 nm)/Al (1 nm)/HATCN (10 nm)/TAPC (80 nm)/TcTa (5 nm)/mCP (5 nm)/1 wt% BN2: 20 wt% (R/S)-OBN-XT-SFAC: CBP (20 nm)/Bphen (40 nm)/LiF (1 nm)/Al (devices (R/S)-T-HF2) (Fig. 6a). The tandem device (R)-T-HF2 exhibits a low start-up voltage of 5.3 V, and radiates strong green light with an EL peak at 540 nm (CIEx,y = 0.28, 0.66) and a narrow FWHM of 39 nm. Encouragingly, tandem device (R)-T-HF2 attains EL performances with a Lmax of 20620 cd m‒2, a ηext,max of 51.3%, a ηc,max of 222.0 cd A‒1 and a ηp,max of 126.8 lm W−1 (Fig. 6b−d and Table 2). Strong CP-EL signals with good gELs of 2.17 × 10−3–2.43 × 10−3, about two-fold higher than that of the device (R)-HF2, are also acquired (Fig. 6f, Supplementary Fig. 24 and Table 2). Meanwhile, device (S)-T-HF2 also provides similar CP-EL performances, with a ηext,max of 50.4% and a gEL of −2.38 × 10−3 (Supplementary Fig. 25 and Supplementary Table 4).

In tandem HF CP-OLEDs, two achiral emitting layers could be induced to produce CP-EL with the same optical activity. The enhancement in CP-EL signals may be owing to the constructive interference of the two CP-EL light waves from two achiral emitting layers, while the possible refraction and reflection of the lights within the tandem device do not significantly weaken the CP-EL signals. These results represent a remarkable achievement as the first example of high-performance tandem HF CP-OLEDs with the best ηext,max reported to date. These preliminary findings also suggest the tandem configuration may have no unfavorable impact on the CP-EL performances but could be conducive to strengthening CP-EL signals.

Discussion

In summary, tailor-made efficient blue-sky CP-TADF materials (R/S)-OBN-XT-SXAC and (R/S)-OBN-XT-SFAC are developed through a straightforward chiral perturbation approach of introducing chiral units (R/S)-OBN into a twisted TADF framework consisting of XT acceptor and spiro donors of SXAC and SFAC. (R)-OBN-XT-SXAC and (R)-OBN-XT-SFAC exhibit strong CP-TADF with fast RISC process (kRISC = 1.6 × 106 and 1.4 × 106 s‒1), short τDFs (1.6 and 1.4 µs), high ΦPLs (98% and 99%) and good gPLs (1.51 × 10−3 and 1.31 × 10−3) in doped films. In addition, the spiro donors promote horizontal emitting dipole orientation, resulting in very large Θ//s and ηouts of up to 88.5% and 40.8%, respectively. Thanks to these advantageous features, these CP-TADF materials perform exceptionally well as emitters in CP-OLEDs, providing high ηext,maxs of up to 33.4% and 33.8%, and strong CP-EL signals with gELs ranging from −2.64 × 10−3 to 2.35 × 10−3. Moreover, they can function as efficient sensitizers for achiral blue and green MR-TADF emitters (v-DABNA and BN2) for fabricating blue and green HF CP-OLEDs, producing strong narrow-spectrum CP-EL with ηext,maxs of 28.5% and 31.4%, narrow FWHMs of 20 and 42 nm, and good gELs of 2.93 × 10−3 and 1.31 × 10−3, respectively. The HF CP-OLEDs based on interlayer sensitization strategy not only furnish good EL performances with narrow EL spectra, but also exhibit prominent CP-EL signals, demonstrating CP-FRET process and particularly CISS effect play significant roles in making achiral MR-TADF emitters radiate strong CP-EL. More intriguingly, as a proof of concept, high-performance blue and green tandem HF CP-OLEDs are realized, which furnish high ηext,maxs of 50.9% and 51.3%, narrow FWHMs of 20 and 39 nm, and improved gELs of 4.87 × 10−3 and 2.43 × 10−3. These devices represent the first and state-of-the-art narrow-spectrum tandem CP-OLEDs developed by employing CP-TADF sensitizers and achiral MR-TADF emitters. Overall, these results indicate (R/S)-OBN-XT-SXAC and (R/S)-OBN-XT-SFAC are promising emitters and sensitizers for high-performance HF CP-OLEDs, and the proposed sensitization strategy could be a feasible approach to construct multi-color HF CP-OLEDs as well, avoiding complicated synthesis and isolation of chiral MR-TADF emitters.

Methods

Materials and instruments

All the chemicals and reagents were purchased from commercial sources and used as received without further purification. The final products were subjected to vacuum sublimation to further improve purity before PL and EL properties investigations. 1H and 13C NMR spectra were measured on a Bruker AV 500 spectrometer at room temperature. High-resolution mass spectra (HRMS) were recorded on Agilent 1290/Bruker maXis impact mass spectrometer operating in Positive HRMS mode. The single crystal X-ray diffraction intensity data were collected at 173 K on a Bruker–Nonices Smart Apex CCD diffractometer with graphite monochromated MoKα radiation. Processing of the intensity data was carried out using the SAINT and SADABS routines, and the structure and refinement were conducted using the SHELTL suite of X-ray programs (version 6.10). Cyclic voltammograms were measured in a solution of tetra-n-butylammonium hexafluorophosphate (Bu4NPF6, 0.1 M) in dichloromethane (oxidation) and N,N-dimethylformamide (reduction) containing the sample at a scan rate of 50 mV s‒1. Three-electrode system (Ag/Ag+, platinum wire and glassy carbon electrode as reference, counter and work electrode respectively) was used in the cyclic voltammetry measurement to determine HOMO and LUMO energy levels (HOMO = −[Eox + 4.8] eV, and LUMO = −[Ere + 4.8] eV). Eox and Ere represent the onset oxidation and reduction potentials relative to ferrocene, respectively. UV-vis absorption spectra were measured on a Shimadzu UV-2600 spectrophotometer. PL spectra were recorded on a Horiba Fluoromax-4 spectrofluorometer. Fluorescence quantum yields were measured using a Hamamatsu absolute PL quantum yield spectrometer C11347 Quantaurus_QY. Transient PL decay spectra were measured in Edinburgh Instruments FLS1000 spectrometer. Circular dichroism (CD) spectra were recorded with a Chirascan spectrometer (Applied Photophysics, England). Circularly polarized photoluminescence (CP-PL) and circularly polarized electroluminescence (CP-EL) spectra were recorded at 100 nm min‒1 scan speed with a commercialized instrument JASCO CPL-300 at room temperature. The CP-PL and CP-EL spectra of each simple were further examined by rotation 90° and 180°, and the profiles were almost the same with 0°.

Device fabrication and characterization

Glass substrates precoated with a 90-nm-thin layer of indium tin oxide (ITO) with a sheet resistance of 20 Ω per square were thoroughly cleaned for 10 minutes in ultrasonic bath of acetone, isopropyl alcohol, detergent, deionized water, and isopropyl alcohol and then treated with O2 plasma for 5 minutes in sequence. Organic layers were deposited onto the ITO-coated substrates by high-vacuum (<5 × 10−4 Pa) thermal evaporation. Deposition rates were controlled by independent quartz crystal oscillators, which were 1 ~ 2 Å s−1 for organic materials, 0.2 Å s−1 for LiF, and 5 Å s−1 for Al, respectively. The emission area of the device was 3 × 3 mm2 as shaped by the overlapping area of the anode and cathode. All the device characterization steps were carried out at room temperature under ambient laboratory conditions without encapsulation. All the devices had their EL spectra, luminance‒voltage‒current density, and external quantum efficiency characterized with a dual-channel Keithley 2400 source meter and a PR-670 spectrometer.

Theoretical calculation

The ground-state geometries were optimized using the density function theory (DFT) method, and the excited-state geometries and properties were studied by time-dependent density functional theory (TDDFT) with PBE0 functional at the basis set level of 6–311 G (d, p). All the calculations were performed using Gaussian16 package. Multiwfn91 and VMD92 softwares are applied to analyze data and visualized.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and the Supplementary Information. Crystallographic data for the structures reported in this Article have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, under deposition numbers CCDC 2310084 ((S)-OBN-XT-SXAC), 2309876 ((S)-OBN-XT-SFAC) and 2310079 ((R)-OBN-XT-SFAC). Copies of the data can be obtained free of charge via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Zhang, M. et al. Processable circularly polarized luminescence material enables flexible stereoscopic 3D imaging. Sci. Adv. 9, eadi9944 (2023).

Lin, S. et al. Photo-triggered full-color circularly polarized luminescence based on photonic capsules for multilevel information encryption. Nat. Commun. 14, 3005 (2023).

Kan, Y. et al. Metasurface‐enabled generation of circularly polarized single photons. Adv. Mater. 32, 1907832 (2020).

Xiao, S. et al. Chiral photonic circuits for deterministic spin transfer. Laser Photonics Rev. 15, 2100009 (2021).

Dai, Y., Chen, J., Zhao, C., Feng, L. & Qu, X. Biomolecule‐based circularly polarized luminescent materials: construction, progress, and applications. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202211822 (2022).

Deng, Y. et al. Circularly polarized luminescence from organic micro-/nano-structures. Light Sci. Appl. 10, 76 (2021).

Kitzmann, W. R., Freudenthal, J., Reponen, A.-P. M., VanOrman, Z. A. & Feldmann, S. Fundamentals, advances, and artifacts in circularly polarized luminescence (CPL) spectroscopy. Adv. Mater. 35, 2302279 (2023).

Sang, Y., Han, J., Zhao, T., Duan, P. & Liu, M. Circularly polarized luminescence in nanoassemblies: generation, amplification, and application. Adv. Mater. 32, 1900110 (2020).

Gong, Z.-L. et al. Frontiers in circularly polarized luminescence: molecular design, self-assembly, nanomaterials, and applications. Sci. China Chem. 64, 2060–2104 (2021).

Zhang, Y. et al. Circularly polarized luminescence in chiral materials. Matter 5, 837–875 (2022).

Uoyama, H., Goushi, K., Shizu, K., Nomura, H. & Adachi, C. Highly efficient organic light-emitting diodes from delayed fluorescence. Nature 492, 234–238 (2012).

Huang, T. et al. Enhancing the efficiency and stability of blue thermally activated delayed fluorescence emitters by perdeuteration. Nat. Photonics 18, 516–523 (2024).

Huang, T., Wang, Q., Meng, G., Duan, L. & Zhang, D. Accelerating radiative decay in blue through-space charge transfer emitters by minimizing the face-to-face donor–acceptor distances. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202200059 (2022).

Zhang, T. et al. Highly twisted thermally activated delayed fluorescence (TADF) molecules and their applications in organic light‐emitting diodes (OLEDs). Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202301896 (2023).

Wang, H. et al. An A‐D‐A‐type thermally activated delayed fluorescence emitter with intrinsic yellow emission realizing record‐high red/NIR OLEDs upon modulating intermolecular aggregations. Adv. Mater. 36, 2307725 (2024).

Fu, Y., Liu, H., Tang, B. Z. & Zhao, Z. Realizing efficient blue and deep-blue delayed fluorescence materials with record-beating electroluminescence efficiencies of 43.4%. Nat. Commun. 14, 2019 (2023).

Ahn, D. H. et al. Highly efficient blue thermally activated delayed fluorescence emitters based on symmetrical and rigid oxygen-bridged boron acceptors. Nat. Photonics 13, 540–546 (2019).

Liu, Y., Li, C., Ren, Z., Yan, S. & Bryce, M. R. All-organic thermally activated delayed fluorescence materials for organic light-emitting diodes. Nat. Rev. Mater. 3, 18020 (2018).

Hwang, J., Nagaraju, P., Cho, M. J. & Choi, D. H. Aggregation-induced emission luminogens for organic light-emitting diodes with a single-component emitting layer. Aggregate 4, e199 (2023).

Cai, Z. et al. Realizing record-high electroluminescence efficiency of 31.5% for red thermally activated delayed fluorescence molecules. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 23635–23640 (2021).

Yuan, L., Zhang, Y.-P. & Zheng, Y.-X. Chiral thermally activated delayed fluorescence materials for circularly polarized organic light-emitting diodes. Sci. China Chem. 67, 1097–1116 (2024).

Zhang, D.-W., Li, M. & Chen, C.-F. Recent advances in circularly polarized electroluminescence based on organic light-emitting diodes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 49, 1331–1343 (2020).

Li, M. & Chen, C.-F. Advances in circularly polarized electroluminescence based on chiral TADF-active materials. Org. Chem. Front. 9, 6441–6452 (2022).

Frédéric, L., Desmarchelier, A., Favereau, L. & Pieters, G. Designs and applications of circularly polarized thermally activated delayed fluorescence molecules. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2010281 (2021).

Ye, Z. et al. Deep-blue narrowband hetero[6]helicenes showing circularly polarized thermally activated delayed fluorescence toward high-performance OLEDs. Adv. Mater. 36, 2308314 (2024).

Zhang, F., Rauch, F., Swain, A., Marder, T. B. & Ravat, P. Efficient narrowband circularly polarized light emitters based on 1,4-B,N-embedded rigid donor–acceptor helicenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202218965 (2023).

Yang, W. et al. Simple double hetero[5]helicenes realize highly efficient and narrowband circularly polarized organic light-emitting diodes. CCS Chem. 4, 3463–3471 (2022).

Yan, Z.-P. et al. A chiral dual-core organoboron structure realizes dual-channel enhanced ultrapure blue emission and highly efficient circularly polarized electroluminescence. Adv. Mater. 34, 2204253 (2022).

Li, X., Xie, Y. & Li, Z. The progress of circularly polarized luminescence in chiral purely organic materials. Adv. Photonics Res. 2, 2000136 (2021).

Wang, Q. et al. Constructing highly efficient circularly polarized multiple‐resonance thermally activated delayed fluorescence materials with intrinsically helical chirality. Adv. Mater. 35, 2305125 (2023).

Fan, X. et al. RGB thermally activated delayed fluorescence emitters for organic light‐emitting diodes toward realizing the BT.2020 standard. Adv. Sci. 10, 2303504 (2023).

Hatakeyama, T. et al. Ultrapure blue thermally activated delayed fluorescence molecules: efficient HOMO–LUMO separation by the multiple resonance effect. Adv. Mater. 28, 2777–2781 (2016).

Fan, X.-C. et al. Ultrapure green organic light-emitting diodes based on highly distorted fused π-conjugated molecular design. Nat. Photonics 17, 280–285 (2023).

Hu, Y. X. et al. Efficient selenium-integrated TADF OLEDs with reduced roll-off. Nat. Photonics 16, 803–810 (2022).

Xing, L. et al. Highly efficient pure-blue organic light-emitting diodes based on rationally designed heterocyclic phenophosphazinine-containing emitters. Nat. Commun. 15, 6175 (2024).

Suresh, S. M. et al. Judicious heteroatom doping produces high‐performance deep‐blue/near‐UV multiresonant thermally activated delayed fluorescence OLEDs. Adv. Mater. 35, 2300997 (2023).

Fan, T. et al. Tailored design of π-extended multi-resonance organoboron using indolo[3,2-b]indole as a multi-nitrogen bridge. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202313254 (2023).

Zhang, Y. et al. Fusion of multi-resonance fragment with conventional polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon for nearly BT.2020 green emission. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202202380 (2022).

Yuan, L. et al. Tetraborated intrinsically axial chiral multi-resonance thermally activated delayed fluorescence materials. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202407277 (2024).

Meng, G. et al. B‐N covalent bond embedded double hetero‐[n]helicenes for pure red narrowband circularly polarized electroluminescence with high efficiency and stability. Adv. Mater. 36, 2307420 (2024).

Yang, Y. et al. Chiral multi‐resonance TADF emitters exhibiting narrowband circularly polarized electroluminescence with an EQE of 37.2 %. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202202227 (2022).

Xu, Y., Wang, Q., Cai, X., Li, C. & Wang, Y. Highly efficient electroluminescence from narrowband green circularly polarized multiple resonance thermally activated delayed fluorescence enantiomers. Adv. Mater. 33, 2100652 (2021).

Wu, X., Yan, X., Chen, Y., Zhu, W. & Chou, P.-T. Advances in organic materials for chiral luminescence-based OLEDs. Trends Chem. 5, 734–747 (2023).

Alías-Rodríguez, M., Graaf, C. D. & Huix-Rotllant, M. Ultrafast intersystem crossing in xanthone from wavepacket dynamics. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 21474–21477 (2021).

Wu, X., Peng, X., Chen, L., Tang, B. Z. & Zhao, Z. Through-space conjugated molecule with dual delayed fluorescence and room-temperature phosphorescence for high-performance OLEDs. ACS Mater. Lett. 5, 664–672 (2023).

Peng, X. et al. Purely organic room-temperature phosphorescence molecule for high-performance non-doped organic light-emitting diodes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202405418 (2024).

Chen, J. et al. Versatile aggregation-enhanced delayed fluorescence luminogens functioning as emitters and hosts for high-performance organic light-emitting diodes. CCS Chem. 3, 230–240 (2021).

Chen, C. et al. Intramolecular charge transfer controls switching between room temperature phosphorescence and thermally activated delayed fluorescence. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 16407–16411 (2018).

Liu, H. et al. High-performance non-doped OLEDs with nearly 100% exciton use and negligible efficiency roll-off. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 9290–9294 (2018).

Huang, J. et al. Highly efficient nondoped OLEDs with negligible efficiency roll-off fabricated from aggregation-induced delayed fluorescence luminogens. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 12971–12976 (2017).

Peng, Q., Ma, H. & Shuai, Z. Theory of long-lived room-temperature phosphorescence in organic aggregates. Acc. Chem. Res. 54, 940–949 (2021).

Li, W. et al. Tri‐spiral donor for high efficiency and versatile blue thermally activated delayed fluorescence materials. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 11301–11305 (2019).

Li, W. et al. Spiral donor design strategy for blue thermally activated delayed fluorescence emitters. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 5302–5311 (2021).

Qu, Y.-K., Zheng, Q., Fan, J., Liao, L.-S. & Jiang, Z.-Q. Spiro compounds for organic light-emitting diodes. Acc. Mater. Res. 2, 1261–1271 (2021).

Lin, T. et al. Sky‐blue organic light emitting diode with 37% external quantum efficiency using thermally activated delayed fluorescence from spiroacridine‐triazine hybrid. Adv. Mater. 28, 6976–6983 (2016).

Yi, C. et al. A rational molecular design strategy of TADF emitter for achieving device efficiency exceeding 36%. Adv. Opt. Mater. 10, 2101791 (2022).

Liao, X.-J. et al. Planar chiral multiple resonance thermally activated delayed fluorescence materials for efficient circularly polarized electroluminescence. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202217045 (2023).

Guo, W.-C., Zhao, W.-L., Tan, K.-K., Li, M. & Chen, C.-F. B. N-embedded hetero[9]helicene toward highly efficient circularly polarized electroluminescence. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202401835 (2024).

Zhang, Y.-P. et al. Circularly polarized white organic light-emitting diodes based on spiro-type thermally activated delayed fluorescence materials. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202200290 (2022).

Yang, S.-Y. et al. Highly efficient sky-blue π-stacked thermally activated delayed fluorescence emitter with multi-stimulus response properties. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202206861 (2022).

Li, M., Wang, M.-Y., Wang, Y.-F., Feng, L. & Chen, C.-F. High-efficiency circularly polarized electroluminescence from TADF-sensitized fluorescent enantiomers. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 20728–20733 (2021).

Zhong, X.-S. et al. Circularly polarized organic light-emitting diodes based on chiral hole transport enantiomers. Adv. Mater. 36, 2311857 (2024).

Fu, Y. et al. Boosting external quantum efficiency to 38.6% of sky-blue delayed fluorescence molecules by optimizing horizontal dipole orientation. Sci. Adv. 7, eabj2504 (2021).

Jiang, R. et al. High-performance orange–red organic light-emitting diodes with external quantum efficiencies reaching 33.5% based on carbonyl-containing delayed fluorescence molecules. Adv. Sci. 9, 2104435 (2022).

Huang, R. et al. Creating efficient delayed fluorescence luminogens with acridine-based spiro donors to improve horizontal dipole orientation for high-performance OLEDs. Chem. Eng. J. 435, 134934 (2022).

Chen, H. et al. An efficient aggregation-enhanced delayed fluorescence luminogen created with spiro donors and carbonyl acceptor for applications as an emitter and sensitizer in high-performance organic light-emitting diodes. Aggregate 4, e244 (2023).

Huang, R. et al. Sky-blue aggregation-induced delayed fluorescence luminogens with high horizontal dipole orientation for efficient organic light-emitting diodes. Chin. J. Chem. 41, 527–534 (2023).

Fu, Y., Liu, H., Tang, B. Z. & Zhao, Z. Exploring efficient blue TADF materials with ultrafast bipolar charge transport for high-efficiency thick-layer OLEDs. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2401434 (2024).

Zhao, T., Han, J., Duan, P. & Liu, M. New perspectives to trigger and modulate circularly polarized luminescence of complex and aggregated systems: energy transfer, photon upconversion, charge transfer, and organic radical. Acc. Chem. Res. 53, 1279–1292 (2020).

Wu, Y. et al. Circularly polarized fluorescence resonance energy transfer (C‐FRET) for efficient chirality transmission within an intermolecular system. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 24549–24557 (2021).

Xu, L. et al. Efficient circularly polarized electroluminescence from achiral luminescent materials. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202300492 (2023).

Stavrou, K., Franca, L. G., Danos, A. & Monkman, A. P. Key requirements for ultraefficient sensitization in hyperfluorescence organic light-emitting diodes. Nat. Photonics 18, 554–561 (2024).

Kondo, Y. et al. Narrowband deep-blue organic light-emitting diode featuring an organoboron-based emitter. Nat. Photonics 13, 678–682 (2019).

Jeon, S. O. et al. High-efficiency, long-lifetime deep-blue organic light-emitting diodes. Nat. Photonics 15, 208–215 (2021).

Stavrou, K. et al. Unexpected quasi-axial conformer in thermally activated delayed fluorescence DMAC-TRZ, pushing green OLEDs to blue. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2300910 (2023).

Liu, H., Fu, Y., Chen, J., Tang, B. Z. & Zhao, Z. Energy-efficient stable hyperfluorescence organic light-emitting diodes with improved color purities and ultrahigh power efficiencies based on low-polar sensitizing systems. Adv. Mater. 35, 2212237 (2023).

Chen, J. et al. Exploring robust delayed fluorescence materials via structural rigidification for realizing organic light-emitting diodes with high efficiencies and small roll-offs. Nano Mocro Small 20, 2306800 (2024).

Zhang, Y., Li, D., Li, Q., Quan, Y. & Cheng, Y. High comprehensive circularly polarized electroluminescence performance improved by chiral coassembled host materials. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2309133 (2023).

Geng, Z., Zhang, Y., Zhang, Y., Quan, Y. & Cheng, Y. Amplified circularly polarized electroluminescence behavior triggered by helical nanofibers from chiral co-assembly polymers. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202202718 (2022).

Chen, Z. et al. High‐performance circularly polarized electroluminescence with simultaneous narrowband emission, high efficiency, and large dissymmetry factor. Adv. Mater. 34, 2109147 (2022).

Chen, Z. et al. Cascade chirality transfer through diastereomeric interaction enables efficient circularly polarized electroluminescence. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2215179 (2023).

Wang, J. et al. Promising interlayer sensitization strategy for the construction of high-performance blue hyperfluorescence OLEDs. Light Sci. Appl. 13, 139 (2024).

Liu, H., Chen, J., Fu, Y., Zhao, Z. & Tang, B. Z. Achieving high electroluminescence efficiency and high color rendering index for all-fluorescent white OLEDs based on an out-of-phase sensitizing system. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2103273 (2021).

Bloom, B. P., Paltiel, Y., Naaman, R. & Waldeck, D. H. Chiral induced spin selectivity. Chem. Rev. 124, 1950–1991 (2024).

Kim, Y.-H. et al. Chiral-induced spin selectivity enables a room-temperature spin light-emitting diode. Science 371, 1129–1133 (2021).

Naaman, R., Paltiel, Y. & Waldeck, D. H. Chiral molecules and the electron spin. Nat. Rev. Chem. 3, 250–260 (2019).

Nishizawa, N., Nishibayashi, K. & Munekata, H. Pure circular polarization electroluminescence at room temperature with spin-polarized light-emitting diodes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 1783–1788 (2017).

Xie, Y.-M., Liao, L.-S. & Fung, M.-K. Hybrid design of light-emitting diodes in tandem structures. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2401789 https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.202401789 (2024).

Fung, M.-K., Li, Y.-Q. & Liao, L.-S. Tandem organic light‐emitting diodes. Adv. Mater. 28, 10381–10408 (2016).

Xu, T. et al. Highly simplified reddish orange phosphorescent organic light-emitting diodes incorporating a novel carrier- and exciton-confining spiro-exciplex-forming host for reduced efficiency roll-off. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9, 2701–2710 (2017).

Lu, T. & Chen, F. Multiwfn: a multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 33, 580–592 (2012).

Humphrey, W., Dalke, A. & Schulten, K. VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 14, 33–38 (1996).

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (U23A20594, 22375066 and 21788102) and the GuangDong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2023B1515040003).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.Z. conceived the study. L.C. and Z.Z. wrote and revised the manuscript. L.C. synthesized and characterized the materials, measured the photophysical property and performed the theoretical simulation. P.Z. fabricated and characterized the OLEDs. J.C. and L.X. provided suggestions on experiments and writing manuscript. Z.Z. and B.Z.T. supervised the project. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, L., Zou, P., Chen, J. et al. Hyperfluorescence circularly polarized OLEDs consisting of chiral TADF sensitizers and achiral multi-resonance emitters. Nat Commun 16, 1656 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56923-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56923-6

This article is cited by

-

Chiral luminescent molecule with aggregate conformational isomerism for multimodal anti-counterfeiting

Science China Chemistry (2025)