Abstract

Lycopodium alkaloids are attractive synthetic targets due to their diverse and unusual skeletal features. While numerous synthetic approaches have been reported, there still remain outstanding synthetic challenges to several lycopodium alkaloids. Herein, a concise total synthesis of lycoposerramine congeners is accomplished through the use of nitrogen deletion strategy (N-deletion) to combine two fully elaborated piperidine and tetrahydroquinoline fragments. Specifically, two natural congeners, lycoposerramine V and W, previously accessible only in 18–23 steps, are each synthesized in 10 steps or less. In contrast to the successful use of N-deletion, many C–C bond forming reactions surveyed fail to deliver the desired coupling product. To further highlight its modular nature, the strategy is applied in the synthesis of two unnatural epimers of lycoposerramine V and W. This work demonstrates the benefits of incorporating modern synthetic methodologies in streamlining access to complex molecules.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since the discovery of huperzine A as a potent acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, alkaloids from the Lycopodium plants (lycopodium alkaloids) have become the subject of intense biological and synthetic research1,2. Broadly speaking, lycopodium alkaloids can be divided into four major structural classes, namely the lycopodine class, the lycodine class, the fawcettimine class, and the phlegmarine class. Members of the phlegmarine class such as phlegmarine (1), cermizine B (2), serratezomine E (3), and lycoposerramines (4−6) share common structural features, namely a decahydroquinoline (DHQ) or 5,6,7,8-tetrahydroquinoline (THQ) core and a pendant piperidine moiety which is oxidized on the nitrogen in lycoposerraminne Z (4) and at the 3-position in lycoposerramine W (6) (Fig. 1A). Diversity within the class further arises from the stereochemical arrangement of the DHQ/THQ moiety, wherein both the 7,15-cis and 7,15-trans configurations have been observed.

A Representative structures of phlegmarine alkaloids. B Synthetic challenges presented by 5 and 6 and prior approaches to address these challenges. HWE: Horner-Wadsworth-Emmons reaction. C Retrosynthesis of 6 featuring enzymatic hydroxylation and late-stage fragment coupling (this work). PG protecting group, FG functional group.

Numerous synthetic approaches featuring either linear or convergent routes have been reported to achieve the total syntheses of phlegmarine alkaloids3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11. In the former category, ring-closing olefin metathesis with Grubbs catalyst was applied to construct the piperidine ring of 2,3, and 5 in Amat and Takayama’s syntheses3,4. Takayama and co-workers also achieved the total synthesis of 6 through SmI2-mediated construction of the hydroxylated piperidine ring (Fig. 1B)4. Yao and co-workers utilized reductive amination with chiral amines to form the DHQ ring of 45 and the piperidine ring of 5 and its epimer6. Zhao and co-workers completed the total synthesis of (±)-2 through diastereoselective Michael addition of 2-picoline, subsequent dearomatization, and methylation to form the pendant piperidine ring7. In contrast, convergent routes entail independent construction of the pendant piperidine and DHQ/THQ units (or their synthetic equivalents), followed by their union. Comins and co-workers accomplished the total synthesis of 1 through dearomative fragment coupling between an iodinated DHQ moiety and a pyridinium salt8. Finally, Bradshaw and Bonjoch applied Horner-Wadsworth-Emmons (HWE) olefination on 2-pyridinylmethyl phosphonate, followed by pyridine hydrogenation in the total synthesis of 2−49,10,11.

While the benefits of convergent synthesis are well-known in the literature, prior coupling strategies would not be well-suited for the construction of THQ-containing phlegmarine alkaloids, such as lycoposerramine V (5) and W (6). A common feature among these convergent approaches is the use of a pyridine synthetic equivalent for the pendant piperidine unit, followed by post-fragment coupling reduction. However, the pyridine ring embedded in the THQ moiety of 5 and 6 would likely present a chemoselectivity challenge in the reduction. Bradshaw and Bonjoch’s pyridine hydrogenation approach was also noted to produce a mixture of epimers at C5 (Fig. 1B). Finally, in the context of lycoposerramine W, it was not immediately clear how this strategy could be readily adjusted to install the C3 alcohol in a stereoselective fashion. To address these issues, we sought to develop a complementary fragment coupling approach that would proceed without any recourse to late-stage oxidation state adjustments (Fig. 1C), setting our sights first on lycoposerramine W (6). In our design, the disubstituted piperidine fragment would be prepared by implementing a structure-goal strategy that capitalizes on the structural resemblance between the target fragment and a known hydroxylated derivative of pipecolic acid. In light of the ready availability of the corresponding precursors, a net oxidative annulation would enable rapid construction of the THQ coupling partner. This disconnection would also offer the opportunity to broadly survey various fragment coupling conditions and benchmark their performance.

Results

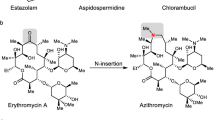

Biocatalytic and chemocatalytic preparation of the pendant piperidine and tetrahydroquinoline fragments

Our synthesis of 6 commenced with the preparation of the piperidine and THQ units for late-stage fragment coupling (Fig. 2). The 4-position of L-pipecolic acid (L-Pip, 7) was site- and stereo-selectively functionalized through a direct enzymatic C–H oxidation by the α-ketoglutarate dependent dioxygenase FoPip4H, which has been examined in a different synthetic context in our previous report12. This gram-scale enzymatic oxidation and successive Boc protection afforded the hydroxylated L-Pip derivative 8 in 86% over 2 steps. Following protection of the secondary alcohol as the tert-butyl dimethylsilyl (TBS) ether in 90% on a multi-gram scale, the carboxylic acid moiety was reduced to the corresponding primary alcohol by using BH3•SMe2 to obtain 10. Initial attempts to prepare the intended coupling partners from 10 included halogenation of the primary alcohol under Mitsunobu conditions and conversion of the alcohol to the methanesulfonyl (Ms) group. However, a bicyclic compound (SI-7) was obtained in both cases, presumably arising from an intramolecular nucleophilic attack from the Boc oxygen to the activated alcohol (Supplementary Table S1). As a workaround, N-Boc to N-methyl conversion was effected by reduction with LiAlH4 to produce 11 in quantitative yield over 2 steps from 9. Unfortunately, the conversion of this alcohol to the corresponding bromide or tosylate failed to proceed and resulted in either the recovery (87%) or decomposition of 11, or the formation of a complex mixture of products (Supplementary Table S1). To broadly examine a variety of fragment coupling reactions, several additional piperidine units were synthesized, including aldehyde 12 and alkene 13 via Dess-Martin periodinane (DMP) oxidation (77% over 2 steps from 9 on a multi-gram scale) and Wittig reaction with MePPh3Br (69% from 12), respectively.

A Enzymatic hydroxylation of L-pipecolic acid 7, followed by chemical modifications to prepare piperidine fragments 10 − 13. B Cu-catalyzed pyridine ring construction to obtain ( ± )− 16 and its conversion to additional THQ fragments 17 − 20. Yields in brackets refer to overall yield from ( ± )− 16.

Turning our attention to the pyridine fragment, several synthetic methods for pyridine ring construction were examined to obtain (±)-16 from 1,3-diketone 14 (Fig. 2B and Supplementary Table S2). A Cu-catalyzed annulation method13 was found to reliably afford (±)-16 from 14 and propargyl amine (15) in 49% on a multi-gram scale. Once again, with the goal of examining a variety of fragment coupling reactions, (±)-16 was used as a divergence point to prepare additional derivatives, including diethyl phosphonate 1714, alkene 18, vinyl triflate 19, and pyridyl bromide 20.

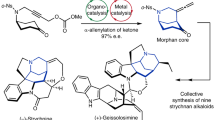

Attempts of fragment coupling and revised retrosynthesis of 6

Fragment coupling between the piperidine and pyridine units was initially examined by means of HWE olefination, olefin metathesis by Grubbs catalyst, Nozaki-Hiyama-Kishi (NHK) reaction, and deoxygenative cross-coupling reactions previously developed by the Weix15 and MacMillan groups16 (Fig. 3A and Supplementary Table S3). Unfortunately, these reactions afforded either a complex mixture of products or unreacted starting materials. To achieve the desired C–C bond construction, we then pivoted to the use of N-deletion strategy, in which a new C–C bond is formed from a secondary amine through in-cage diradical coupling with N2 evolution via an isodiazene intermediate upon reacting the amine with a nitrogen transfer reagent17,18,19,20,21,22. It has also been reported that some of these reactions proceed in a stereospecific manner and maintain the stereochemistry of the N-deletion precursor, and the memory of the chirality phenomenon has been put forth to rationalize this observation20. Translating this idea to our synthesis campaign, the desired coupling product 21 would be obtained from N-deletion of 22, which would in turn, be accessed from aldehyde 12 and optically pure amine (5S, 7 R)-23 through reductive amination (Fig. 3B).

A Failed fragment coupling attempts to access the phlegmarine skeleton. HWE: Horner-Wadsworth-Emmons reaction, NHK: Nozaki-Hiyama-Kishi reaction. See Supplementary Table S3 in the Supplementary Information for detailed reaction conditions. B Revised retrosynthesis of 6 featuring N-deletion of 22. FGI: functional group interconversion.

Preparation of amine 23 from a chiral building block and N-deletion precursor 22

To obtain the chiral amine 23, we submitted ketone (±)-16 to asymmetric reduction as well as reductive amination with several chiral amines (Fig. 4A, Supplementary Figs. S1 and S2, and Supplementary Tables S4 and S5). Initial attempts to effect this transformation included in situ reductive amination in the presence of chiral secondary amines and stepwise imine formation with chiral primary amines in the presence of Brønsted and Lewis acid. However, none of these approaches succeeded in providing the desired product. Conversely, asymmetric reduction of (±)-16 utilizing Noyori’s Ru catalyst in the presence of HCO2H and NEt3 gave an optically pure product 24a in 26% (Entry 2 of Supplementary Table S5). Further optimization of this reaction afforded 24a (42%) and 24b (28%) (Entry 8 of Supplementary Table S5), whose structure and enantiopurity were confirmed by X-ray crystallography and derivatization with a chiral carboxylic acid, respectively (see Experimental Section and X-ray data collection in the Supplementary Information). Asymmetric imine hydrogenation under Noyori conditions was also examined but led to no desired product formation (Fig. S2). It is worth noting that while 24b could be obtained with Noyori reduction, separation of product diastereomers with flash column chromatography was highly challenging, rendering the route unsuitable for large-scale use. Stereoinvertive azide displacement of the alcohol on 24b under Mitsunobu conditions proceeded in 91% yield, which was followed by hydrogenation to give optically pure (5S, 7 R)-23 in 83%.

A First-generation synthesis of chiral amine fragment 23 from ( ± )− 16. B Second-generation synthesis of chiral amine fragment 23 from (R)-pulegone. C N-deletion of 22 and total synthesis of lycoposerramine W 6. D Selected results from benzylic oxidation screening. E Selected results from N-deletion optimization. a0.02 or 0.05 mmol scale, NH2CO2NH4 (8 eq.), b0.1 mmol scale.

As the above route featured an inefficient reductive kinetic resolution with difficult purification and several concession steps, we decided to explore a different route to 23. To this end, a second-generation synthesis commenced with a retro-aldol reaction on (R)-pulegone 25, a useful chiral building block, under aqueous acidic condition in the presence of cetylpyridinium chloride (CPC)23 to afford (R)-3-methylcyclohexanone (R)-SI-6. This chiral ketone was subjected to the Cu-catalyzed annulation with propargyl amine 15 to give a mixture of (R)-26 and its regioisomer (R)-27 with a ratio of 3.0:1.0 in 45% over 2 steps (see Supplementary Table S6 for reaction optimization). Chemocatalytic benzylic azidation and biocatalytic benzylic oxidation of this mixture to directly generate SI-10 and 24b, respectively, were briefly explored but proved fruitless (Supplementary Fig. S3). Our effort thus turned to benzylic oxidation of (R)-26 to obtain (S)-16 and separate it from (R)-27 (Fig. 4D and see Supplementary Table S7 in the Supplementary Information for reaction optimization Table S7). Initial screening of reaction conditions, including the use of metal- and photoredox-catalyzed oxidation24,25,26,27,28,29, produced promising results with manganese salts in the presence of tert-butyl hydrogen peroxide (Fig. 4D and Entry 2 and 3 of Table S7). In subsequent optimization, we varied the identity of the manganese salt, solvent and additives and ultimately identified that loading an increased amount of Mn(OAc)3 (10 mol%) and using a higher substrate concentration (0.5 M) improved the reaction yield to 32% (Entry 24 of Supplementary Table S7). Finally, extending the reaction time from 16 h to 24 h furnished the desired pyridyl ketone (S)-16 in 41% on a gram scale (Fig. 4B). Despite the higher step count relative to our first-generation synthesis, this route avoids the use of expensive ruthenium catalyst and eschews the need for difficult chromatographic separation.

With chiral (S)-16 in hand, we revisited its reductive amination with simpler amines. While condensation with methoxyamine and O-benzylhydroxylamine successfully delivered the corresponding oximes, hydrogenation of the oxime derived from the latter proceeded with superior yield and diastereoselectivity (Supplementary Fig. S4). With this insight, (S)-16 was subjected to oxime formation with O-benzylhydroxylamine, followed by hydrogenation to provide (5S, 7 R)-23 in 66% over 2 steps (d.r. = 20:1). The cis configuration was confirmed by comparing the 1H NMR of this batch of material with that prepared from 24b (Supplementary Fig. S5). The asymmetric reduction of (S)-16 to 24b under the Noyori condition described above was also examined but resulted only in a moderate yield (40%, Supplementary Fig. S6) and attempts to obtain (5S, 7 R)-23 via biocatalytic transamination of (±)-16 was unsuccessful (Supplementary Table S8). Finally, reductive amination of 23 with aldehyde 12 using NaBH(OAc)3 provided the N-deletion precursor 22 in 86% on a gram-scale as a single diastereomer (Fig. 4C).

Nitrogen-deletion of 22 and total synthesis of lycoposerramine W 6

With the precursor 22 in hand, we examined the proposed N-deletion strategy with a number of nitrogen transfer reagents such as Levin’s anomeric amide 2817, sulfamoyl azides18,19, hypervalent iodine reagents (29a,b)20, and O-diphenylphosphinylhydroxyulamine (DPPH)22 (Fig. 4C and E, and Supplementary Table S9). Initial results were disappointing as no desired product could be observed with the anomeric amide, sulfamoyl azides, and 29a. However, switching the hypervalent iodine reagent from 29a to its mesyloxy substituent 29b30 led to an initial hit of 4% yield of 21, which provided a starting point for further optimization. Lowering the reaction temperature and adjusting the reagent introduction to drop-wise addition in 2,2,2-trifluoroethanol (TFE) provided a 29% yield (Supplementary Fig. S7), which improved further to 51% upon conducting the reaction on a 0.1 mmol scale, and 21 was formed as a single diastereomer in the reaction, suggesting a complete transfer of stereo information without erosion. This observation is consistent with the proposed mechanism of in-cage diradical formation and recombination under the influence of the memory of chirality20. It is worth noting that, prior to our work, the use of hypervalent iodine reagents in N-deletion has only been examined in the context of cyclobutane synthesis20, and this work expanded its utility in constructing an attached ring system. Boc deprotection, N-methylation (86% over 2 steps), and TBS deprotection under acidic conditions (71%) completed our total synthesis of lycoposerramine W in 10 steps (longest linear sequence, LLS). The spectroscopic data of our synthetic sample are in good agreement with those of natural and synthetic ones reported by Takayama et al.4.

Total synthesis of lycoposerramine V 5 and epimers through late-stage N-deletion strategy

We next examined whether the late-stage N-deletion strategy could be applied to other THQ-containing phlegmarine alkaloids, such as lycoposerramine V 5 (Fig. 5A). A chiral piperidine fragment (S)-30 was prepared from commercially available N-Boc-L-pipecolic acid (S)-SI-14 in 56% over 2 steps and then reacted with (5S, 7 R)-23 to afford N-deletion precursor 31 in 82% yield. The initial attempt of N-deletion on 29b under the optimized conditions resulted in a mixture of inseparable products even after Boc deprotection. Fortunately, changing the nitrogen transfer reagent from 29b to DPPH22 successfully delivered the N-deletion product. Subsequent Boc deprotection afforded 5 as a single diastereomer in 16% yield over 2 steps, completing the total synthesis of 5 in 8 steps (LLS) overall. While the spectroscopic data of our synthetic sample are in good agreement with those of natural and synthetic ones4, it should be noted that different purification procedures provide different NMR spectra, and we assume that these discrepancies arise from the various protonation states of the amine in 5 (Supplementary Fig. S8). In addition, the 7,15-cis configuration was confirmed by 2D NMR correlations in COSY and NOESY analyses, which was consistent with the literature4. Finally, the established strategy was also applied in the synthesis of 5-epi-lycoposerramine V (5-epi-5) and 15-epi-lycoposerramine W (15-epi-6), by starting from the corresponding stereoisomers of the coupling fragments and using the appropriate N-deletion conditions (Fig. 5B and C). Similar to 5, 5-epi-5 was observed to exhibit different 1H NMR spectra depending on the purification protocols, which are assumed to arise from the various protonation states of the secondary amine and the concentration of the NMR samples (Supplementary Fig. S9). Cumulatively, these syntheses highlight the straightforward and intuitive nature of N-deletion logic in synthesis as the transformation can almost be regarded as a C–C cross-coupling equivalent between an amine and an aldehyde. Furthermore, various stereochemical diads can be accessed in a modular fashion owing to the general stereo fidelity of the reaction. While the yield of the reaction can vary greatly, our success in applying the reaction on a challenging C–C bond formation that could not be achieved with any other means suggests that at the very least, the reaction merits strong tactical consideration during the design of complex molecule synthesis.

Discussion

Herein, we demonstrated the viability of an N-deletion strategy to couple two fully functionalized fragments for the synthesis of several phlegmarine-type alkaloids. We first completed the total synthesis of lycoposerramine W (6) in 10 steps (LLS). The structural resemblance between the hydroxylated piperidine unit in 6 and a known hydroxylated derivative of pipecolic acid allowed us to install the C3-OH early through scalable enzymatic oxidation on unprotected L-Pip. Conversely, the racemic THQ subunit (±)-16 was accessed in one step through a Cu-catalyzed oxidative annulation process, which in turn provided the opportunity to systematically investigate the performance of various fragment coupling approaches. Subsequently, an improved synthesis of the chiral THQ fragments (5S, 7 R)-23 was achieved from (R)-pulegone 25 through retro-aldol degradation, Cu-catalyzed oxidative annulation, Mn-catalyzed benzylic oxidation, and stereoselective reductive amination. A key enabling feature of our synthesis is the identification of an N-deletion strategy for fragment coupling, which proved to be the only feasible method to achieve the desired C–C bond construction. Among the N-deletion method examined, we uncovered the utility of Antonchick’s hypervalent iodine-based method beyond its original scope in cyclobutane formation and improved the outcome of the reaction through the use of reagent 29b, which had never been examined before in this context. Furthermore, the late-stage N-deletion strategy was applied to the total syntheses of lycoposerramine V (8 steps, LLS) and two epimers of lycoposerramine V and W, and we anticipate that the strategy can be readily extended to access all the possible C5/C7/C15 stereochemical triads found in other phlegmarine alkaloids. In the broader context of synthetic strategy development, the work presented herein outlines a straightforward logic for designing nitrogen “traceless linchpin”17 strategies to build molecular complexity, which consists of chiral amine synthesis, reductive amination, and nitrogen deletion for stereocontrolled C–C bond formation. The conceptual simplicity of this logic should inspire its broader adoption in complex molecule synthesis.

Methods

General Information

Unless otherwise noted, all chemicals and reagents for chemical reactions were purchased at the highest commercial quality and used without further purification. (R)-Pelegone was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and purified by distillation at 110 °C under reduced pressure prior to use because the purity was reported > 90%. Reactions were monitored by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) and liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry (LC/MS). TLC was performed with 0.25 mm E. Merck silica plates (60F-254) using short-wave UV light as the visualizing agent, KMnO4, ninhydrin, and heat as developing agents. 3-(Ethylenediamino)propyl-functionalized silica gel (200–400 mesh) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. LC/MS analysis was performed with Agilent 1260 Infinity System. High-resolution mass spectrum (HRMS) analysis was performed by using Agilent AdvanceBio 6545XT LC/Q-TOF mass spectrometer equipped with Agilent Technologies 1290 Infinity II injection system (Agilent, California, USA). NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker AVANCE AV600 (600 MHz for 1H NMR, 151 MHz for 13C NMR, 565 MHz for 19F, and 243 MHz for 31P NMR) (Bruker, Massachusetts, USA). IR spectra were recorded on a PerkinElmer, FTIR Spectrum 100 (ATR) instrument (PerkinElmer, Massachusetts, USA). Optical rotations were measured on a Polartronic M100 polarimeter (SCHMIDT + HAENSCH, Berlin, Germany) in 100 mm cells using the D line of sodium (589 nm) at 20 °C. X-ray crystal structure analysis was performed on an XRD Rigaku Synergy-S equipped with dual-beam microfocus Cu and Mo radiation sources (Cu radiation source was used for the data collection) and paired with a Rigaku’s Hypix-Arc150 detector (Rigaku, Tokyo, Japan). Sonication was performed using a Qsonica Q500 sonicator. Biochemicals and media components were purchased from standard commercial sources. E. coli. BL21(DE3) cells harboring pET-28a(+)-FoPip4H plasmid were stored as glycerol stocks at − 80 °C.

Biocatalytic hydroxylation of L-Pip for the synthesis of 8

An overnight culture of E. coli. BL21(DE3) cells harboring pET-28a(+)-FoPip4H plasmid in LB media (4 mL) containing kanamycin (50 μg/mL) was used to inoculate into TB media (250 mL in 2 × 1 L Erlenmeyer flask) containing kanamycin (50 μg/mL). The culture was shaken at 250 rpm at 37 °C for 3 h or until an OD600 = 0.6–0.8 was reached and cooled on ice for 15 min, after which IPTG (25 mM in H2O) was added to a final concentration of 25 μM for the induction and the resulting culture was shaken at 250 rpm at 20 °C for 20 h. The cells were collected by centrifugation (2719 × g, 4 °C, 10 min), resuspended in KPi buffer (50 mM, pH 7, 200 mL) (OD600 = ca. 18), and then lysed by sonication at 50% amplitude for 4 min (1 s on, 3 s off) in an ice bath. After centrifugation (2719 × g, 4 °C, 10 min), the clarified lysate supernatant was diluted 1:1 with KPi buffer (50 mM, pH 7). 2 × 1 L Erlenmeyer flasks were used for the reaction, each containing L-pipecolic acid 7 (1.03 g, 8 mmol, 1 eq., 40 mM), α-ketoglutaric acid (3.63 g, 16 mmol, 2 eq.), FeSO4•7H2O (112 mg, 4 mmol, 0.5 eq.), and L-ascorbic acid (707 mg, 0.40 mmol, 0.05 eq.) in the clarified lysate (200 mL). The suspensions were shaken at 250 rpm at 22 °C for 20 h in the open Erlenmeyer flasks. The reactions were quenched with 6 N HCl aq. to pH 2 and centrifuged (2719 × g, 4 °C, 10 min). The combined supernatants were concentrated to ca. 300 mL and used for the next reaction.

The supernatant was basified by the addition of 6 N NaOH aq. to pH 10, to which a solution of (Boc)2O (8.73 g, 40 mmol, 2.5 eq.) in EtOH (150 mL) was added dropwise at room temperature with vigorous stirring. After 30 min, the reaction solution was adjusted to pH 10 by 6 N NaOH aq., and stirred at room temperature for 21 h. Ethanol was removed under reduced pressure and 6 N HCl aq. was added to the resulting solution until pH 1. The aqueous layer was extracted with EtOAc (150 mL) until the product was extracted completely, as judged by TLC and LCMS analysis. The combined organic layer was washed with brine, dried over NaSO4, filtered and concentrated under reduced pressure. The resulting residue was purified by silica gel column chromatography (S.C.C., CH2Cl2/MeOH = 20/1, 1% AcOH) followed by the evaporation with toluene (100 mL × 2) to afford 8 as a colorless solid (3.39 g, 13.8 mmol, 86%).

Synthesis of 21 through N-deletion

A 2 mL vial was charged with 22 (55.3 mg, 0.113 mmol, 1 eq.) and NH2CO2NH4 (70.8 mg, 0.907 mmol, 8 eq.) in 2,2,2-trifluoroethanol (TFE) (0.5 mL). After purging the atmosphere with N2, the solution was treated with hydroxy(mesyloxy)iodobenzene 29b (35.7 mg, 0.113 mmol, 1 eq.)30 in TFE (0.1 mL) dropwise over 5 min, and the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 20 min. The dropwise addition of 29b (1 eq.) in TFE (0.1 mL) over 5 min and stirring for 20 min were repeated additional 7 times. After the dropwise addition was completed (8 eq. in total), the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 1 h, diluted with sat. NaHCO3 aq. (10 mL), and then extracted with EtOAc (10 mL × 3). The combined organic layer was washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, filtered and concentrated under reduced pressure. The resulting residue was purified by S.C.C. (hexanes/AcOEt = 4/1) to afford 21 as a colorless amorphous (27.2 mg, 0.0573 mmol, 51%).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study, including figures, tables, experimental procedures, characterization data, and NMR spectra, are available within this article and its Supplementary Information. The X-ray crystallographic data of 24b (CCDC deposit number: 2289617) was deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center (CCDC). The data can be obtained free of charge via https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures/. All data are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Ma, X. & Gang, D. R. The lycopodium alkaloids. Nat. Prod. Rep. 21, 752–772 (2004).

Hirasawa, Y., Kobayashi, J. & Morita, H. The lycopodium alkaloids. Heterocycles 77, 679–729 (2009).

Pinto, A. et al. Studies on the synthesis of phlegmarine-type lycopodium alkaloids: enantioselective synthesis of (-)-cermizine B, (+)-serratezomine E, and (+)-luciduline. J. Org. Chem. 83, 8364–8375 (2018).

Shigeyama, T., Katakawa, K., Kogure, N., Kitajima, M. & Takayama, H. Asymmetric total syntheses of two pholegmarine-type alkaloids, lycoposerramines-V and -W, newly isolated from lycopodium serratum. Org. Lett. 9, 4069–4072 (2007).

Zhang, L.-D., Zhong, L.-R., Zi, J., Yang, Z.-L. & Yao, Z.-J. Enantioselective total synthesis of lycoposerramine-Z using chiral phosphoric acid catalyzed intramolecular Michael addition. J. Org. Chem. 81, 1899–1904 (2016).

Zhang, L.-D. et al. Total syntheses of lycoposerramine-V and 5-epi-lycoposerramine-V. Chem. Asian. J. 9, 2740–2744 (2014).

Shi, X. et al. Total synthesis of ( ± )-cermizine B. J. Org. Chem. 82, 11110–11116 (2017).

Wolfe, B. H., Libby, A. H., Al-awar, R. S., Foti, C. J. & Comins, D. L. Asymmetric synthesis of all the known phlegmarine alkaloids. J. Org. Chem. 75, 8564–8570 (2010).

Bradshaw, B., Luque-Corredera, C. & Bonjoch, J. cis-Decahydroquinolines via asymmetric organocatalysis: application to the total synthesis of lycoposerramine. Z. Org. Lett. 15, 326–329 (2013).

Bradshaw, B., Luque-Corredera, C. & Bonjoch, J. A gram-scale route to phlegmarine alkaloids: rapid total synthesis of (-)-cermizine B. Chem. Commun. 50, 7099 (2014).

Bosch, C., Fiser, B., Gómez-Bengoa, E., Bradshaw, B. & Bonjoch, J. Approach to cis-phlegmarine alkaloids via stereodivergent reduction: total synthesis of (+)-serratezomine E and putative structure of (-)-huperzine N. Org. Lett. 17, 5084–5087 (2015).

Amatuni, A., Shuster, A., Abegg, D., Adibekian, A. & Renata, H. Comprehensive structure-activity relationship studies of cepafungin enabled by biocatalytic C–H oxidations. ACS Cent. Sci. 9, 239–251 (2023).

Sotnik, S. O. et al. Cu-catalyzed pyridine synthesis via oxidative annulation of cyclic ketones with propargylamine. J. Org. Chem. 86, 7315–7325 (2021).

Miao, W. et al. Copper-catalyzed synthesis of alkylphosphonates from H-phosphonate and N-tosylhydrazones. Adv. Synth. Catal. 354, 2659–2664 (2012).

Benjamin, K. et al. In-situ bromination enables formal cross-electrophile coupling of alcohols with aryl and alkenyl halides. ACS Catal. 12, 580–586 (2022).

Dong, Z. & MacMillan, D. W. C. Metallaphotoredox-enabled deoxygenative arylation of alcohols. Nature 598, 451–456 (2021).

Kennedy, S. H., Dherange, B. D., Berger, K. J. & Levin, M. D. Skeletal editing through direct nitrogen deletion of secondary amines. Nature 593, 223–227 (2021).

Zou, X., Zou, J., Yang, L., Li, G. & Lu, H. Thermal rearrangement of sulfamoyl azides: reactivity and mechanistic study. J. Org. Chem. 82, 4677–4688 (2017).

Qin, H. et al. N-Atom deletion in nitrogen heterocycles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 20678–20683 (2021).

Hui, C., Brieger, L., Strohmann, C. & Antonchick, A. P. Stereoselective synthesis of cyclobutanes by contraction of pyrrolidines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 18864–18870 (2021).

Wtight, B. A. et al. Skeletal editing approach to bridge-functionalized bicyclo[1.1.1]pentanes from azabicyclo[2.1.1]hexanes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 10960–10966 (2023).

Guo, T., Li, J., Cui, Z., Wang, Z. & Lu, H. C(sp3)–C(sp3) bond formation through nitrogen deletion of secondary amines using O-diphenylphosphinylhydroxyulamine. Nat. Synth. 3, 913–921 (2024).

Vashchenko, E. V., Knyazeva, I. V., Krivoshey, A. I. & Vashchenko, V. V. Retro-aldol reaction in micellar media. Manatsh Chem. 143, 1545–1549 (2012).

Ren, L. et al. Synthesis of 6,7-dihydro-5H-cyclopenta[b]pyridine-5-one analogues through manganese-catalyzed oxidation of the CH2 adjacent to pyridine moiety in water. Green Chem. 17, 2369 (2015).

Hruszakewycz, D. P., Miles, K. C., Thiel, O. R. & Stahl, S. S. Co/NHPI-mediated aerobic oxidation of benzylic C–H bonds in pharmaceutically relevant molecules. Chem. Sci. 8, 1282 (2017).

Yi, H., Bian, C., Hu, X., Niu, L. & Lei, A. Visible light mediated efficient oxidative benzylic sp3 C–H to ketone derivatives obtained under mild conditions using O2. Chem. Commun. 51, 14046 (2015).

Wilde, N. C., Isomura, M., Mendoza, A. & Baran, P. Two-phase synthesis of (-)-taxuyunnanine D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 4909–4912 (2014).

Bonvin, Y. et al. Bismuth-catalyzed benzylic oxidations using t-butyl hydroperoxide. Tetrahedron Lett. 46, 2581–2584 (2005).

Wang, Y., Chen, X., Jin, H. & Wang, Y. Mild and practical dirhodium(II)/NHPI-mediated allylic and benzylic oxidations with air as the oxidant. Chem. Eur. J. 25, 14273–14277 (2019).

Yusubov, M. S. & Wirth, T. Solvent-free reactions with hypervalent iodine reagents. Org. Lett. 7, 519–521 (2005).

Acknowledgements

Financial support for this work is provided, in part, by the Welch Foundation (award number C2159 to H.R.). K.Y. acknowledges fellowship support from the Naito Foundation in Japan. We are grateful to the Shared Equipment Authority at Rice University for access to their instruments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.R. conceived and directed the project. K.Y. performed experiments and collected analytical data described in this manuscript. H.R. and K.Y. co-wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Chunfa Xu and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yokoi, K., Renata, H. Enantioselective total synthesis of lycoposerramine congeners through late-stage nitrogen deletion. Nat Commun 16, 1659 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56956-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56956-x