Abstract

Space-time wave packets (STWPs) with correlated spatial and frequency degrees of freedom exhibit time-dependent spatial interference, thereby giving rise to interesting dynamic evolution behaviors. While versatile spatiotemporal phenomena have been demonstrated in freely propagating fields, coupling spatiotemporal light into multimode fibers remains a fundamental experimental challenge. Whereas synthesizing freely propagating STWPs typically relies on a continuum of plane-wave modes, their multimode-fiber counterparts must be constructed from the discrete set of fiber modes whose propagation constants depend on fiber structures. Here, we demonstrate STWPs with axially controllable motion of the transverse profile and reconfigurable group velocity in graded-index multimode fibers. This is accomplished by introducing a linear association between frequency comb lines and corresponding fiber modes. The synthesized STWPs present dynamic rotation and translation with a 4.8-ps period. Simultaneously, the group velocity can be tuned from positive subluminal and superluminal to negative values (e.g., 0.870, 1.35, 10, and –3.3 × 108 m/s, respectively).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Space-time wave packets (STWPs) that incorporate precise correlations between their spatial and temporal spectral contents offer unique prospects for sculpting the spatiotemporal field dynamics1,2,3,4,5. By associating each temporal frequency with a prescribed transverse spatial field, direct control can be exercised over the field dynamics1,2,3,4,5. A wide range of useful characteristics have been realized in this way for freely propagating fields. Examples include dynamic evolution of spatial properties6,7,8, propagation invariance in free space or dispersive media1,9, tunable group velocity (Vg) independently of the refractive index10,11,12, anomalous refraction13, and axial acceleration14. More generally, spatiotemporally structuring the optical field has produced interesting field configurations, including time-varying orbital angular momentum (OAM)15,16,17, transverse OAM18,19, and toroidal pulses20,21.

Common among all these examples of spatiotemporally structured optical wave packets is their realization in a freely propagating field. STWPs offer a unique advantage by virtue of their independence of dimensionality: STWPs retain their characteristics even when the field is structured along only one transverse dimension. Consequently, guided STWPs have been realized in planar slab waveguides22,23 and in surface plasmon polaritons24,25 where the guidance mechanism provides field confinement in one dimension, leaving freedom for spatiotemporally structuring the field along the unguided dimension.

This leaves open a fundamental challenge: constructing STWPs in which the underlying spatial modes are those of the waveguide itself26,27. This necessitates the utilization of a multimode optical waveguide or fiber. In such an environment, STWPs can ameliorate many features that challenge optical communications in a multimode fiber (MMF). Guided STWPs maintain their time-averaged spatial intensity profile along the propagation axis, their group velocity can be tuned, and they offer reduced group-velocity dispersion (GVD) and guided-mode dispersion. An initial demonstration in a one-dimensional (1-D) highly multimode slab waveguide28,29, in which the waveguide modes approximate free-space plane-wave modes, has confirmed some of these basic features. However, this leaves open the challenge of realizing 2-D guided STWPs, particularly in an MMF, a case that has been examined theoretically30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39.

In this paper, we propose, simulate, and experimentally demonstrate STWPs in a graded-index (GRIN) fiber with controllable dynamic motions and group velocities40. Unlike free-space systems where an infinite set of spatial modes is available, propagation in a fiber is only possible in terms of a finite number of guided modes whose propagation constants (β) are directly determined by the refractive index profile of the fiber itself41,42. When synthesizing the STWPs, a linear correlation between frequency, propagation constant β, and mode order is utilized. This is facilitated by the equidistant β spectrum associated with the spatial modes in a GRIN parabolic fiber, allowing the dispersion lines to be parallel and equally spaced. In this regime, the resulting wave packets are shown to exhibit dynamic rotational or translational dynamics with a period of 4.8 ps. The STWP group velocities in this fiber setting are measured by the time delay between different fiber lengths, and they can be tailored from positive superluminal (3.36 c) and subluminal (0.29 c) to negative (–1.10 c) values.

This work points to the feasibility of synthesizing spatiotemporally structured fields for multimode optical waveguides and fibers, thereby opening up new vistas of their applications, including imaging and sensing43,44,45, nonlinear optical interactions46,47, and signal processing48.

Results

Concept of space-time wave packet in multimode fiber

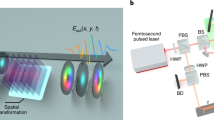

The dynamic motion of the transverse intensity profile and group-velocity control are two typical spatiotemporal phenomena that can be produced by sculpting the spatiotemporal spectral structure of an STWP. For a pulsed beam in free space, these two phenomena require each temporal frequency undergirding the optical pulse to be linearly correlated to the axial propagation constant of the spatial mode undergirding the transverse beam. For MMFs, the field is constrained to be a superposition of a discrete set of confined, guided modes. The dispersion relation between the β of any such mode and frequency is determined by the refractive index profile of the fiber and the modal order. Rather than the spatial modes in free space used in constructing freely propagating STWPs, their MMF counterparts, as shown in Fig. 1, are synthesized using the guided modes after associating each mode with a prescribed temporal frequency, thereby yielding controllable dynamic motion of the transverse field profile along the fiber axis, and tunable group velocity of the synthesized STWP.

a, b Dynamic motion: a STWPs in MMFs can be synthesized by manipulating the transverse fields of a frequency comb spectrum. The dynamic phase delay between different frequency components leads to time-varying interference between the spatial modes, resulting in a temporally evolving transverse spatial profile in the fiber. b An example of dynamic rotation produced by correlating the frequencies with Laguerre-Gaussian LGℓ,0 modes. At different times, the frequency-induced phase delay matches the orbital angular momentum (OAM) values of different frequencies. Therefore, the phase profiles for all frequencies experience the same dynamic rotation angle. c, d Group velocity control: c Propagation constants (β) are near-linearly spaced for different frequencies and mode groups (MGs) in the GRIN fiber. Each MG consists of multiple degenerate modes with similar β. In a comb-based STWP, where equal mode-group spacing (∆MG) is maintained between adjacent frequencies (ω), the slope of the ω-β curve represents the group velocity (Vg), which Vg can be tailored to superluminal, subluminal, or negative values. Examples of MG choices for different Vg values are shown (e.g., subluminal \(\Delta {MG}=-\!2\), luminal \(\Delta {MG}=0\), superluminal \(\Delta {MG}=+\! 1\), and negative \(\Delta {MG}=+ \!2\) velocities). d The Vg dictates the time delay for these STWPs with distances.

A GRIN MMF is a particularly suitable candidate for fiber-based STWPs due to its unique dispersion relation. Guided modes in a GRIN MMF can be represented in different modal bases and corresponding modal indicies, including Laguerre-Gaussian modes (\({{LG}}_{{\ell},p}\)), linearly polarized modes (\({{LP}}_{l,m}\)), and Hermite-Gaussian modes (\({{HG}}_{m,n}\))49. The β for GRIN fiber modes follows an approximately linear relation with frequency. Spatial degenerate modes in the fiber have a similar effective index and approximately the same β, thereby forming modal groups (MGs). Crucially, the dispersion curve for a GRIN fiber is equally spaced for different MGs. The propagation constant \({\beta }_{f,{MG}}\) for modes at a frequency of \(f\) in a mode group of order MG can be expressed by50:

where \(k\) is the wavenumber at frequency \(f\); c is the speed of light in vacuum; \({n}_{0}\) is the refractive index on the fiber axis; and \(b\) is a scaling parameter. Here, MG is a function of the modal indices, with \({MG}=|{\ell}|+2p+1\) for the LG modal basis, \({MG}=l+2m-1\) for the LP modal basis, and \({MG}=m+n+1\) for the HG modal basis, respectively41,42.

Therefore, STWPs in a GRIN MMF can be synthesized using a frequency comb with equal frequency spacing, where each frequency line is associated with a designated fiber mode. Taking LG modes as an example, the synthesized electric field is

where n is the index of the frequencies; and \({{LG}}_{{\ell}\left(n\right),p\left(n\right)}\) is the mode assigned to the nth frequency. Spatiotemporal phenomena can thus be tailored by assigning different fiber modes to different frequencies. Two characteristics are mainly studied in this paper:

-

(a)

Dynamic motion: The frequency difference between comb lines induces a time-dependent phase delay in the transverse spatial modes of the STWP. Consequently, the interference between these spatial modes evolves dynamically, leading to a temporally varying transverse field36,38,45,51,52,53. Figure 1a, b shows an example of temporal rotating motion by associating \({{LG}}_{{\ell},0}\) modes with the different comb frequencies. At different times, the frequency-induced phase delay matches the OAM values at different frequencies. Therefore, the phase profiles for all the frequencies experience the same dynamic rotation angle, resulting in a rotationally interfered intensity profile. A similar method has also been previously considered for demonstrating intensity transport along the propagation direction for monochromatic light54,55. In this respect, evolving intensity patterns such as rotation and translation have been experimentally demonstrated56,57,58,59.

-

(b)

Group velocity control: Group velocity will induce a time delay between the wave packets measured at two propagation distances, as shown in Fig. 1c, d. The Vg of an STWP can be estimated from the dispersion relation dω/dβ, where ω is the angular frequency. Leveraging the linear spacing between β for different MGs, the Vg of a comb-synthesized STWP in a GRIN fiber can be controlled by a proper choice of the MGs35,37,38. We define mode-group difference ∆MG as the difference between the mode group values of consecutive frequencies when sorted in increasing order, whereby Vg is given by:

Consequently, a wide range of different Vg values can be achieved with proper frequency and mode spacing choices, including subluminal (\(\Delta {MG} \, < \, 0\)), superluminal (\(0 \, < \, \Delta {MG} \, < \, \frac{2\pi {n}_{0}b\Delta f}{c}\)), and negative values (\(\Delta {MG} \, > \, \frac{2\pi {n}_{0}b\Delta f}{c}\)).

In conventional pulses propagating along MMFs, inter-modal dispersion arises because different modes generally have different Vg, causing pulse spreading as it travels. However, in-fiber STWPs fundamentally avoid this drawback. In STWPs, each frequency is assigned to a specific mode such that the Vg is determined by the slope of the frequency–mode correlation, rather than being affected by inherent Vg differences between modes. As a result, intermodal dispersion is effectively reduced, enabling the pulse to maintain its spatiotemporal structure with propagation.

Experimental demonstrations of dynamic motion in multimode fiber

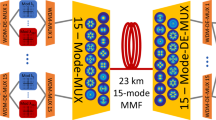

We experimentally demonstrate the proposed wave packet by synthesizing the spatial modes at different frequency comb lines. The resulting wave packet is further launched into a GRIN MMF, as shown in Fig. 2a (see Methods for a detailed description). 5 comb lines with a 208 GHz spacing are selected from a turn-key integrated Kerr micro-comb by a liquid crystal on silicon (LCoS) based wave selective switch (WSS). All frequency lines are tuned with the same intensity and initial phase, and the spectrum and auto-correlation results are presented in Fig. 2b, c. Subsequently, each frequency line is modulated with a designated fiber mode. We couple the wave packet into a 1.25-m-long, 50-μm-core-diameter, parabolic GRIN MMF for STWP propagation. The MMF supports 10 mode groups and 55 modes at 1550 nm. The electric field of the propagated wave packet at the fiber end is extracted by a spatiotemporal off-axis hologram with a free-space Gaussian reference (see Methods for a detailed description). This measurement has a time step of 50 fs controlled by the delay line.

a Schematics of the experimental setup. A turn-key integrated Kerr comb functions as the source. Five comb lines are selected by a programmable liquid crystal on silicon (LCoS) based wave selective switch (WSS). These frequencies are subsequently separated for spatiotemporal synthesis and reference. The synthesized STWP is coupled to a 1.25-m GRIN MMF. After that, the output from the fiber is collimated again and imaged to the camera together with the reference pulse. b The optical spectrum of 5 comb lines selected by the programmable LCoS WSS filter. c Autocorrelation results of the pulse after the programmable LCoS WSS filter. FHWM: full width at half maximum.

We first examine the dynamic motion of the transverse intensity in the fiber. As depicted in Fig. 3a, an STWP with temporal rotation is constructed using LGℓ,0 modes when ℓ is linearly correlated with the 5 frequencies. The isosurfaces in the figures are plotted at 50% of the maximum intensity values. In this particular case, ℓ increases by +1 with the frequency from ℓ = +5 to ℓ = +9. As a result of interference, the spatial intensity profile of the STWP rotates clockwise, and the rotating cycle equals the pulse period of 4.8 ps (i.e., 1/208 GHz). Figure 3b presents the transverse intensity profiles at different times. The profile size is rescaled according to the focal length of the fiber collimator. During the circular rotation motion, the beam rotates with a constant angular velocity, and the intensity profile is retained almost the same at different positions. Notably, though we measure the dynamic behavior at the fiber end, the same intensity motion is expected to occur along the fiber. Meanwhile, this preserved wave packet structure after propagation can partially indicate that the STWP in GRIN fiber travels along the fiber with a steady Vg without strong group delay dispersion, which is consistent with the theory.

a Reconstructed isosurface of the wave packet with clockwise dynamic rotation. The specific STWP is constructed by LGℓ,0 modes (ℓ = 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, mode group spacing ΔMG = Δℓ = +1). b Transverse intensity profiles at different times. The dashed circle in the figures represents the diameter of the fiber core.

The dynamic motion can be tailored by devising different spatial modes correlated with frequencies. For example, the sign of Δℓ will affect the rotation direction, and the absolute value of Δℓ determines the number of petals in the intensity profiles. Moreover, choosing spatial modes from various modal sets can be utilized to achieve different kinds of motions. Two other examples are experimentally realized and depicted in Fig. 4. As shown in Fig. 4a–c, a horizontal translation can be synthesized by LP modes, which have mirror symmetry. Therefore, by assigning LPl,m=1 a modes (a represents the orientation of the mode, and this mode corresponds to LGℓ,0 + LG-ℓ,0) to different frequencies, a movement happens in the x-direction axis, while staying symmetric along with respect to the y-axis. Additionally, an STWP with a bullet-like spatial and temporal profile can be generated by utilizing LG0,p modes, as shown in Fig. 4d–f. LG0,p modes have uniform intensity and phase distribution along the azimuthal direction, while varying along the radial direction. Meanwhile, it should be noted that these LG0,p modes belong to different mode groups; thus, the STWP also has a tailored Vg. Therefore, STWPs with normal Gaussian-like spatial and temporal shape but controlled Vg can be achieved using LG0,p modes.

a–c STWP with dynamic translational motion. The STWP is constructed by linearly polarized LPl,m=1 a modes (l = 4, 3, 2, 1, 0, mode group spacing ΔMG = Δl = –1). b–f STWP with bullet-like spatial and temporal pulse shape. The STWP is constructed by LG0,p modes (p = 4, 3, 2, 1, 0, mode group spacing ΔMG = 2Δp = –2). a, d Reconstructed isosurface of the wave packets. b, e Temporal evolution of intensity profiles along the x-axis. c, f Transverse intensity profiles at different times.

Experimentally tailored group velocity in multimode fiber

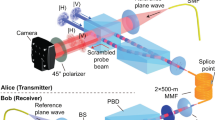

Next, we demonstrate control over the group velocity of the STWP in the fiber. Given 10 different mode groups of the MMF, 5 different Vg values are achieved by tuning the ΔMG between adjacent frequency lines from –2 to +2. With 208 GHz spacing and a fiber b parameter of 1.85 × 10-4, the theoretical Vg values calculated by the slope of the dispersion curves show a variation from superluminal to subluminal and also negative values.

A typical approach to measuring the Vg records the time delay between the propagated wave packets at different distances. To avoid ambiguity in calculating the Vg, the time delay shall be less than one pulse period. Particularly in our case and given the relatively small pulse period of 4.8 ps, the maximum allowable distance difference to avoid ambiguity is around 360 μm (for the subluminal case where Vg ≈ 0.760 × 108 m/s). For this reason, we alter the propagation distance by stretching the fiber with 250 μm using a motorized translation stage with precision <5 μm. However, the stretching also decreased the refractive index, thereby affecting the Vg. To compensate for this effect, we estimated the index decrease Δneff to be –3.8 × 10-5, and then calculated the index-change-induced time delay (see Methods for details)41,42. Finally, the experimental Vg is estimated by

where Δz is the fiber length change; Δt is the time delay measured with two different fiber lengths; and Δtcomp is the compensation time delay for the index change.

In the experiment, the time delay is retrieved by calculating the temporal-power-weighted average of the spatial overlapping between the wave packets at two distances, defined as

where \({E}_{{z}_{0}}\left(x,y,t\right)\) and \({E}_{{z}_{0}+\Delta z}\left(x,y,t\right)\) correspond to the electric field of the STWPs before and after stretching, respectively; and \(\tau\) is the time shift. Such overlapping integral reaches the maximum when \(\tau\) matches the time delay between the two STWPs. The maximum value of the integral reveals the similarity between the two wave packets. Figure 5 shows examples of the correlation curve when ΔMG = –1, +1, and +2, corresponding to subluminal, superluminal, and negative group velocity, respectively. The maximum overlapping is calculated to be 86% at Δt = 1 ps, 81% at Δt = 0.1 ps, and 70% at Δt = –0.7 ps for the three cases, respectively. These results reveal that the spatiotemporal structure is retained after stretching. The degradation of the maximum correlation might be because of: (a) distortion to the modal structure as a result of stretching and (b) instability in the delay line interferometer (e.g., vibration-induced beam center shift).

a Frequency-β relationship of an STWP with ΔMG = –1 corresponding to a subluminal Vg. The correlation result shows a 1-ps time delay in 250 μm. b Frequency-β relationship of an STWP with ΔMG = +1 corresponding to a superluminal value Vg. The correlation result shows a 0.1-ps time delay in 250 μm. c Frequency-β relationship of an STWP with ΔMG = +2 corresponding to a negative value Vg. The correlation result shows a –0.7-ps time delay in 250 μm.

Figure 6 shows the theoretical and estimated experimental Vg as a function of ΔMG. Specifically, ΔMG = 0 represents the Gaussian pulse corresponding to the luminal case in MMF used as a reference. The experimental results generally match the theoretical predicted values. Specifically, the superluminal Vg when ΔMG = +1 demonstrates a higher difference than the theoretical value. That could be because the corresponding Δt for a large Vg is close to our measurement time resolution (50 fs), leading to a larger error when estimating Vg.

Moreover, we tune the Vg at several distinct values in our experiment by changing fiber modes. It might also be possible to tailor the Vg by adjusting the frequency spacing between comb lines.

Discussion

In this paper, we demonstrate generation and propagation of STWPs in a GRIN MMF, exhibiting controllable dynamic axial motion of the transverse spatial profile and tunable group velocity. The STWP is synthesized by assigning the different frequency lines from an optical comb to designated fiber modes. The wave packets thus produced exhibit dynamic rotational or translational motion with a period of 4.8 ps, as determined by the frequency spacing of the comb. The group velocity can be tuned from subluminal to superluminal and negative values (e.g., 0.870, 1.35, 10, and –3.3 × 108 m/s, respectively).

These wave packets, with their customizable dynamically evolving properties and controllable group velocities, may potentially enable useful applications in imaging, sensing, nonlinear interactions, and signal processing in multimode waveguides. While some of these applications have already been demonstrated using STWPs in free space, the use of MMFs may significantly extend these possibilities to environments and locations that are not easily accessible with free-space optics. Potential examples of these applications might be: (a) For imaging, STWPs through MMFs might open the possibility of dynamic spatiotemporal focusing, where light pulses may be synchronized with transient events at the fiber output, especially when high resolution and adaptability to dynamic phenomena are desirable43,44,45. (b) In the realm of nonlinear interactions, STWPs may facilitate phase-matching configurations by correlating frequency components with specific spatial modes. The ability to control the group velocity might enable precise synchronization of interacting waves, optimizing the efficiency of nonlinear processes. Furthermore, the unique dynamical evolution of STWPs may potentially provide a platform for exploring nonlinear optical phenomena in compact, fiber-based environments46,47. (c) For signal processing, the tunable group velocities of STWPs might enable their use as fiber-based optical delay lines. These delay lines may provide precise timing for high-speed communication systems or multiplexed data streams, ensuring synchronization across channels by real-time adjustments to optical signal paths48.

We note that there are some limitations in the experiment that motivate future exploration. In this paper, we have mainly focused on STWPs in GRIN fibers where the linearly spaced dispersion lines align with the equal frequency spacing of the comb. However, we note that our approach can potentially be generalized to other fibers with different types of mode-dispersion relationships28,35. In this case, the choice of carrier frequency for each mode should match the spacing between different dispersion lines (ω-β) of fiber modes; indeed, a similar concept has been theoretically and experimentally demonstrated for 1-D slab waveguides28,35. As an indication that STWPs may exist in other types of fibers, in Supplementary Note 1, we take step-index MMFs as an example and simulate STWPs synthesized with dynamic motion and controllable group velocity similar to those demonstrated here with GRIN MMFs.

In our demonstration, the number of frequency lines involved in the wave packet is limited by the number of supported guided modes in the MMF, as well as by the experimental setup for spatiotemporal synthesis. A limited number of frequency lines can be accessed and processed in our setup, which can be potentially enhanced by exploiting alternative experimental approaches such as multi-plane light converters (MPLCs)60 and metasurfaces61. To expand the frequency bandwidth, a potential approach might rely on dividing the entire spectrum into multiple sub-combs with fewer lines and recycling the fiber modes for synthesis. The same frequency-mode assignment can be replicated for each sub-comb62. It might also be possible to directly generate STWPs in fiber with nano-structures fabricated on the fiber ends63. Using 3-D laser nanoprinting, 3-D metasurface can be realized on a fiber end-facet for structured light field generation. It might be possible to design these nano-structures with appropriate frequency dependence of their response, such that different frequencies can be shaped with prescribed spatial profiles, thereby enabling direct STWPs synthesis at the fiber end.

Additionally, modal coupling in the MMF of our experiment is reduced by keeping the fiber straight. In general, imperfections in the fiber structures, bends, or external perturbations can disrupt the ideal propagation of light and induce modal coupling in MMFs. Further investigation is required to explore the influence of modal coupling for STWPs propagating in MMFs. In particular, for GRIN MMFs, the modal coupling is mainly within the same mode groups (intra-modal-group coupling). As a result, β of each frequency in the STWP may still remain similar, and the group velocity could be retained. As detailed in Supplementary Note 2, we simulate an STWP propagating in GRIN MMFs with modal coupling, indicating a similar Vg held after propagation in this case. The modal coupling in MMF generally remains a challenge for long-distance propagation of STWPs. Possible future directions might include: (a) exploring STWPs synthesized in specially designed fibers with reduced modal coupling, such as ring-core fibers that support OAM modes64,65, and (b) mitigating coupling effects by employing fiber eigenmodes for STWP synthesis, achieved through measuring the fiber transmission matrix66.

Methods

Experimental details

The output of the micro-ring resonator-based Kerr comb (from Enlightra) is fed into a programmable LCoS WSS. Five frequency lines are subsequently selected, and the amplitude and phase of the different frequencies are tuned to be the same by the programmable LCoS WSS. The optical pulse with an initial Gaussian spatial profile is divided into two paths for STWP generation and reference. A detailed scheme for the spatiotemporal synthesis appears in Supplementary Information Fig. S3a. To synthesize the designed light field, we first use two cascaded gratings to separate the frequencies by a proper spatial spacing with a propagation distance of approximately 2 m. They are followed by two SLMs for spatial modulation. The propagation of the frequencies is depicted in Supplementary Information Fig. S3b. SLM 1 is mainly used for mode generation. We generate digital holographic patterns on the SLM to directly modulate the intensity and phase profiles for each frequency. Meanwhile, the reflecting angle of each beam is tailored by grating patterns, such that all beams arrive at the same position on SLM 2. SLM 2 is used to tailor the propagation direction of the five frequencies, so that they propagate coaxially afterwards. Five grating patterns are summed on SLM 2. For each frequency, optical power is divided evenly into 5 different reflection directions corresponding to the 5 gratings. The grating angles are designed so that each frequency has a corresponding grating to redirect the beam to the output direction. Therefore, all 5 frequency components will propagate coaxially after SLM 2. Two typical holographic patterns on the SLMs are shown in Supplementary Information Fig. S3c. A 2-lens 4-\(f\) imager system is used to relay the field generated at SLM 1 to the fiber collimator. The focal length of the lens is set as 80 cm. The generated STWP is then coupled and propagated in the MMF.

The total transmission loss for our setup is ∼22 dB when comparing the optical power before the first optical grating and before the collimator to the MMF. This power loss is mainly contributed by (i) the insertion loss of the optical elements, including the grating, lenses, and mirrors; (ii) diffraction efficiency loss of SLMs (i.e., power loss to undesired diffraction orders); (iii) the conversion efficiency of the complex modulation on SLM 1; and (iv) the loss of beam combining on SLM 2 (i.e., theoretically 4/5 fraction of the power will be lost when combining 5 frequencies using the gratings). We note that higher efficiency could be potentially achieved by using other spatial modulation techniques such as MPLCs60 and metasurfaces61 to achieve simultaneous efficient mode conversion and beam combining.

Spatiotemporal off-axis hologram

To extract the total electric field of the STWP at different time instants, we perform off-axis holography and sweep the delay stage on the reference arm (\({\Delta z}_{{ref}}\))67. The time-integrated intensity profile recorded by the camera is given by67:

where \({E}_{{STWP},n}\left(x,{y;}{z}_{0}\right)\) and \({E}_{{ref},n}\left(x,{y;}{\Delta z}_{{ref}}\right)\) are the transverse electric fields of the wave packet to be measured at distance \({z}_{0}\) and the reference pulse at the \(n\)-th temporal frequency at the distance set by the delay stage \({\Delta z}_{{ref}}\). Since the reference pulse has a relatively large Gaussian spatial profile, we assume it to be a series of plane waves with different temporal frequencies. These plane waves have a spatial frequency term \({e}^{i{k}_{x}x}\) representing the difference in the arriving angle between the STWP and the reference. Equation (7) shows the estimated electric field of the reference pulse at the \(n\)-th temporal frequency:

where \({{k}_{z}}_{{ref},n}\) is the propagation constant of the \(n\)-th temporal frequency, and \({{k}_{x}}^{2}+{{{k}_{z}}_{{ref},n}}^{2}={{{k}_{\omega }}_{n}}^{2}\). When the angle between the STWP and reference is small, we estimate \({{k}_{z}}_{{ref},n}\) as \({{k}_{\omega }}_{n}\), and the propagation-induced phase can be assumed to be caused by a time delay \(t={\Delta z}_{{ref}}/c\). However, it shall be noted that due to the difference between \({k}_{z}\) and \({k}_{\omega }\), the assumption of time delay t becomes less accurate as the off-axis angle increases. Additionally, the \({k}_{z}\) value varies nonlinearly with frequency, leading to nonlinear dispersion when estimating the time delay, especially if the optical spectrum is broad.

Since the camera has a limited bandwidth, cross-temporal frequency beatings are not recorded in the picture. Moreover, the time integral on the temporal phase term \(\int {e}^{-i{\omega }_{n}t}{e}^{i{\omega }_{n}t}{dt}\) becomes a constant and can be normalized. Thus, the recorded intensity profile can be simplified to become:

Performing a Fourier transform and spatial frequency filtering-based image processing, we can retrieve the electric field from the off-axis holograph as:

The translation delay produced by the reference can be regarded as time variable \(t={\Delta z}_{{ref}}/c\) for the wave packet. Therefore, the electric field of the STWP at a specific time can be measured by this off-axis holograph with a swept reference delay.

Refractive index change induced by stretching the fiber

As a result of fiber stretching, the effective refractive index of the fiber modes decreases and influences the group velocity synthesized in the fiber. This kind of index change has been widely investigated for fiber Bragg grating sensors41,42. Specifically, the effective index change can be estimated using the theory of photoelasticity. A lateral stress on the fiber changes the refractive index via a strain-optic effect. When the fiber is stretched along the propagation z-axis, the effective index change is estimated by41,42

Here, \({p}_{11}\) is the component of the strain optical tensor, L is the original fiber length, and ΔL is the stretched fiber length. Taking n0 = 1.46, \({p}_{11}\) = 0.12, L = 1.25 m, and ΔL = 250 μm, Δneff is estimated as 3.8 × 10-5. Subsequently, we use the new index of the fiber core to estimate the theoretical group velocity after the stretching as

Therefore, the time delay without (\(\Delta t\)) and with (\(\Delta {t}^{{\prime} }\)) considering stretching-induced Vg change can be represented by

To calculate the compensation time delay for the index change, we subtract the time difference as

Table S1 in Supplementary Information shows the experimentally measured time delay, calculated compensation time, and estimated group velocity.

Data availability

Data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary information files. All raw data generated during the current study are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

References

Yessenov, M., Hall, L. A., Schepler, K. L. & Abouraddy, A. F. Space-time wave packets. Adv. Opt. Photon. 14, 455–570 (2022).

Pierce, J. R. et al. Arbitrarily structured laser pulses. Phys. Rev. Res. 5, 013085 (2023).

Shen, Y. et al. Roadmap on spatiotemporal light fields. J. Opt. 25, 093001 (2023).

Jolly, S. W., Gobert, O. & Quéré, F. Spatio-temporal characterization of ultrashort laser beams: a tutorial. J. Opt. 22, 103501 (2020).

Chong, A., Renninger, W. H., Christodoulides, D. N. & Wise, F. W. Airy–Bessel wave packets as versatile linear light bullets. Nat. Photon. 4, 103–106 (2010).

Shaltout, A. M. et al. Spatiotemporal light control with frequency-gradient metasurfaces. Science 365, 374–377 (2019).

Zhao, Z. et al. Dynamic spatiotemporal beams that combine two independent and controllable orbital-angular-momenta using multiple optical-frequency-comb lines. Nat. Commun. 11, 4099 (2020).

Yessenov, M., Hall, L. A., Ponomarenko, S. A. & Abouraddy, A. F. Veiled talbot effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 243901 (2020).

Kondakci, H. E. & Abouraddy, A. F. Diffraction-free space–time light sheets. Nat. Photon. 11, 733–740 (2017).

Yessenov, M. et al. Space-time wave packets localized in all dimensions. Nat. Commun. 13, 4573 (2022).

Froula, D. H. et al. Spatiotemporal control of laser intensity. Nat. Photon. 12, 262–265 (2018).

Guo, C., Xiao, M., Orenstein, M. & Fan, S. Structured 3D linear space–time light bullets by nonlocal nanophotonics. Light Sci. Appl. 10, 160 (2021).

Bhaduri, B., Yessenov, M. & Abouraddy, A. F. Anomalous refraction of optical spacetime wave packets. Nat. Photon. 14, 416–421 (2020).

Yessenov, M. & Abouraddy, A. F. Accelerating and decelerating space-time optical wave packets in free space. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 233901 (2020).

Rego, L. et al. Generation of extreme-ultraviolet beams with time-varying orbital angular momentum. Science 364, eaaw9486 (2019).

Zou, K. et al. Tunability of space-time wave packet carrying tunable and dynamically changing OAM value. Opt. Lett. 47, 5751–5754 (2022).

Su, X. et al. Temporally and longitudinally tailored dynamic space-time wave packets. Opt. Express 32, 26653–26666 (2024).

Chong, A., Wan, C., Chen, J. & Zhan, Q. Generation of spatiotemporal optical vortices with controllable transverse orbital angular momentum. Nat. Photon. 14, 350–354 (2020).

Jhajj, N. et al. Spatiotemporal optical vortices. Phys. Rev. X 6, 031037 (2016).

Zdagkas, A. et al. Observation of toroidal pulses of light. Nat. Photon. 16, 523–528 (2022).

Wan, C., Cao, Q., Chen, J., Chong, A. & Zhan, Q. Toroidal vortices of light. Nat. Photon. 16, 519–522 (2022).

Shiri, A., Yessenov, M., Webster, S., Schepler, K. L. & Abouraddy, A. F. Hybrid guided space-time optical modes in unpatterned films. Nat. Commun. 11, 6273 (2020).

Shiri, A. & Abouraddy, A. F. Severing the link between modal order and group index using hybrid guided space-time modes. ACS Photonics 9, 2246–2255 (2022).

Schepler, K. L., Yessenov, M., Zhiyenbayev, Y. & Abouraddy, A. F. Space–time surface plasmon polaritons: a new propagation-invariant surface wave packet. ACS Photonics 7, 2966–2977 (2020).

Ichiji, N. et al. Observation of ultrabroadband striped space-time surface plasmon polaritons. ACS Photonics 10, 374–382 (2023).

Stefańska, K., Béjot, P., Tarnowski, K. & Kibler, B. Experimental observation of the spontaneous emission of a space–time wavepacket in a multimode optical fiber. ACS Photonics 10, 727–732 (2023).

Cao, Q., Chen, Z., Zhang, C., Chong, A. C. & Zhan, Q. Propagation of transverse photonic orbital angular momentum through few-mode fiber. Adv. Photonics 5, 036002 (2023).

Shiri, A., Webster, S., Schepler, K. L. & Abouraddy, A. F. Propagation-invariant space-time supermodes in a multimode waveguide. Optica 9, 913–923 (2022).

Shiri, A., Schepler, K. L. & Abouraddy, A. F. Theory of space–time supermodes in planar multimode waveguides. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 40, 1142 (2023).

Lichtenberg, B., Gallagher, N. C. & Ziolkowski, R. W. Closed-form, localized wave solutions in optical-fiber waveguides: comment. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 10, 2090–2091 (1993).

Zamboni-Rached, M., Recami, E. & Fontana, F. Superluminal localized solutions to Maxwell equations propagating along a normal-sized waveguide. Phys. Rev. E 64, 066603 (2001).

Zamboni-Rached, M., Nóbrega, K. Z., Recami, E. & Hernández-Figueroa, H. E. Superluminal X-shaped beams propagating without distortion along a coaxial guide. Phys. Rev. E 66, 046617 (2002).

Zamboni-Rached, M., Fontana, F. & Recami, E. Superluminal localized solutions to Maxwell equations propagating along a waveguide: the finite-energy case. Phys. Rev. E 67, 036620 (2003).

Ruano, P. N., Robson, C. W. & Ornigotti, M. Localized waves carrying orbital angular momentum in optical fibers. J. Opt. 23, 075603 (2021).

Guo, C. & Fan, S. Generation of guided space-time wave packets using multilevel indirect photonic transitions in integrated photonics. Phys. Rev. Res. 3, 033161 (2021).

Béjot, P. & Kibler, B. Spatiotemporal helicon wavepackets. ACS Photonics 8, 2345–2354 (2021).

Kibler, B. & Béjot, P. Discretized conical waves in multimode optical fibers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 023902 (2021).

Béjot, P. & Kibler, B. Quadrics for structuring invariant space–time wavepackets. ACS Photonics 9, 2066–2072 (2022).

Jolly, S. W. & Kockaert, P. Coupling to multi-mode waveguides with space-time shaped free-space pulses. J. Opt. 25, 054002 (2023).

Su, X. et al. Demonstration of space-time wave packets in optical fibers with dynamic motion and tunable group velocity. in Frontiers in Optics + Laser Science 2023 (FiO, LS2023), paper JTu7B.1.

Jeunhomme, L. B. Single-Mode Fiber Optics: Prinicples and Applications. (Routledge, New York, 2019).

Okamoto, K. Fundamentals of Optical Waveguides. (Elsevier, 2021).

Lin, S., Gong, L. & Huang, Z. Time-of-flight resolved stimulated Raman scattering microscopy using counter-propagating ultraslow Bessel light bullets generation. Light Sci. Appl. 13, 148 (2024).

Liang, J., Zhu, L. & Wang, L. V. Single-shot real-time femtosecond imaging of temporal focusing. Light Sci. Appl. 7, 42 (2018).

Liu, Y. et al. Integrated vortex soliton microcombs. Nat. Photon. 18, 632–637 (2024).

Vieira, J., Mendonça, J. T. & Quéré, F. Optical control of the topology of laser-plasma accelerators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 054801 (2018).

Turnbull, D. et al. Raman amplification with a flying focus. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 024801 (2018).

Yessenov, M., Bhaduri, B., Delfyett, P. J. & Abouraddy, A. F. Free-space optical delay line using space-time wave packets. Nat. Commun. 11, 5782 (2020).

Saleh, B. E. A. & Teich, M. C. Fundamentals of Photonics. (John Wiley & Sons, 2019).

Boonzajer Flaes, D. E. et al. Robustness of light-transport processes to bending deformations in graded-index multimode waveguides. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 233901 (2018).

Piccardo, M. et al. Broadband control of topological–spectral correlations in space–time beams. Nat. Photon. 17, 822–828 (2023).

Lin, Q. et al. Direct space–time manipulation mechanism for spatio-temporal coupling of ultrafast light field. Nat. Commun. 15, 2416 (2024).

Chen, B. et al. Integrated optical vortex microcomb. Nat. Photon. 18, 625–631 (2024).

Jarutis, V., Matijošius, A., Trapani, P. D. & Piskarskas, A. Spiraling zero-order Bessel beam. Opt. Lett. 34, 2129–2131 (2009).

Matijošius, A., Jarutis, V. & Piskarskas, A. Generation and control of the spiraling zero-order Bessel beam. Opt. Express 18, 8767–8771 (2010).

Vetter, C. Generalized radially self-accelerating helicon beams. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 183901 (2014).

Morris, J. E. et al. Realization of curved Bessel beams: propagation around obstructions. J. Opt. 12, 124002 (2010).

Zhao, J. et al. Specially shaped Bessel-like self-accelerating beams along predesigned trajectories. Sci. Bull. 60, 1157–1169 (2015).

Dorrah, A. H., Zamboni-Rached, M. & Mojahedi, M. Frozen Waves following arbitrary spiral and snake-like trajectories in air. Appl. Phys. Lett. 110, 051104 (2017).

Cruz-Delgado, D. et al. Synthesis of ultrafast wavepackets with tailored spatiotemporal properties. Nat. Photon. 16, 686–691 (2022).

Chen, L. et al. Synthesizing ultrafast optical pulses with arbitrary spatiotemporal control. Sci. Adv. 8, eabq8314 (2022).

Hall, L. A. & Abouraddy, A. F. Spectrally recycling space-time wave packets. Phys. Rev. A 103, 023517 (2021).

Li, C. et al. Metafiber transforming arbitrarily structured light. Nat. Commun. 14, 7222 (2023).

Brunet, C. et al. Design of a family of ring-core fibers for OAM transmission studies. Opt. Express 23, 10553–10563 (2015).

Zhu, G. et al. Scalable mode division multiplexed transmission over a 10-km ring-core fiber using high-order orbital angular momentum modes. Opt. Express 26, 594–604 (2018).

Carpenter, J., Eggleton, B. J. & Schröder, J. 110×110 optical mode transfer matrix inversion. Opt. Express 22, 96–101 (2014).

Cuche, E., Marquet, P. & Depeursinge, C. Spatial filtering for zero-order and twin-image elimination in digital off-axis holography. Appl. Opt. 39, 4070–4075 (2000).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the Office of Naval Research through a MURI Award (N00014−20-1−2789); Defense University Research Instrumentation Program (FA9550-20-1-0152); and Qualcomm Innovation Fellowship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.S., K.Z., A.F.M., and A.E.W. conceived the idea; X.S., K.Z., Y.W., and M.Y. developed the theory and performed the simulation; X.S., K.Z., and A.E.W. designed the experiment; X.S., K.Z., H.Z., H.S., and K.W. conducted the experiment; X.S., K.Z., Y.W., R.Z., A.A., M.R., and Y.D. carried out the data analysis; A.F.M., M.T., D.N.C. and A.E.W. provided the technical support. All the authors contributed to the interpretation of the results and manuscript writing. The project was supervised by A.E.W.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Pierre Bejot and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Su, X., Zou, K., Wang, Y. et al. Space-time wave packets in multimode optical fibers with controlled dynamic motions and tunable group velocities. Nat Commun 16, 2027 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56982-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56982-9