Abstract

Because of vectorial protein translation, residues that interact in the native protein structure but are distantly separated in the primary sequence are unavailable simultaneously. Instead, there is a temporal delay during which the N-terminal interaction partner is unsatisfied and potentially vulnerable to non-native interactions. We introduce “Native Fold Delay” (NFD), a metric that integrates protein topology with translation kinetics to quantify such delays. We found that many proteins exhibit residues with NFDs in the range of tens of seconds. These residues, predominantly in well-structured, buried regions, often coincide with aggregation-prone regions. NFD correlates with co-translational engagement by the yeast Hsp70 chaperone Ssb, suggesting that native fold-delayed regions have a propensity to misfold. Supporting this, we show that proteins with long NFDs are more frequently co-translationally ubiquitinated and prone to aggregate upon Ssb deletion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Globular protein function is determined by its native structure. Achieving this structure involves folding an elongated polypeptide chain into a specific conformation while avoiding off-pathway conformations that can lead to misfolding and aggregation. Most of our mechanistic understanding of protein folding derives from classic in vitro experiments in which the (re)folding of purified, full-length protein is monitored. These experiments yielded invaluable insights, including, first and foremost, the notion that the primary amino acid sequence of a protein encodes the conformational information specifying its native fold1. However, a large fraction of the proteome cannot refold from a denatured state in vitro and instead tends to misfold and aggregate2. This is particularly true for proteins that are large, multimeric, and topologically complex (i.e., high contact order3), often requiring the assistance of molecular chaperones in the cellular environment. Yet, surprisingly, even when supplemented with chaperones, a significant fraction of proteins still remains unable to refold in vitro4.

An aspect that is overlooked in such refolding experiments is protein translation. Protein translation progresses at an average rate of about 20 aas/s in prokaryotes and around five aas/s in eukaryotes5,6,7, meaning that the complete synthesis of proteins can take seconds and even up to minutes as opposed to the folding of secondary and tertiary structures, which is much faster, generally in the range of microseconds to seconds8. Hence, in vivo, local folding events often take place while a polypeptide chain emerges from the ribosome, i.e., co-translationally. Indeed, it is estimated that one-third of the E. coli cytosolic proteome folds at least one entire domain co-translationally9, and this fraction is likely higher in eukaryotes given their slower translation rates. In fact, several studies have shown that native contacts between amino acids can already start to form in the narrow ribosomal exit tunnel, enabling compacted structural elements such as alpha helices10. The gradual addition of residues allows the growing polypeptide chain to sample stabilizing native interactions in a reduced conformational space, forming co-translational folding intermediates that can effectively avoid kinetic traps that are associated with interactions with not yet formed residues towards the C-terminus in the sequence11. Moreover, several studies have shown that codon usage (often used as a proxy of translation rates) is optimized to regulate co-translational folding pathways12,13. Slowing down translation rates can allow an already synthesized N-terminal portion more time to fold independently from a C-terminal portion. On the other hand, speeding up translation can prevent specific folding intermediates from being populated. Therefore, the vectorial nature and the rates of translation are exploited in vivo to increase folding efficiency. This has been put forth as one of the explanations for why many proteins fold more efficiently co- than post-translationally14,15,16,17,18.

However, co-translational folding is a double-edged sword. While vectorial protein production provides a timeframe in which local folding events can occur in a reduced conformational space, bypassing folding trajectories that are prone to misfolding and aggregation, it also imposes a temporal delay on folding events that require long-range native interactions, such as the formation of parallel β-sheet topologies19. We reason that non-native intra- or intermolecular interactions might form co-translationally during the time it takes to produce the C-terminal segments involved in such long-range native contacts, potentially leading to off-pathway conformations. In support of this, several sources report that newly synthesized proteins are more vulnerable to misfolding and aggregation compared to once they matured20,21,22, with topologically complex proteins, i.e., those with more long-range interactions, being more at risk21. In addition, artificially inducing ribosome pausing during translation, which would increase the temporal delay between long-range contacts, triggers widespread protein misfolding and aggregation23.

To avoid premature co-translational misfolding events, an entire branch of the proteostasis network (PN) exists that acts specifically at the translation stage24. Firstly, ribosomes themselves have a holdase function as their negatively charged surface interacts with nascent chains, preferentially with basic and aromatic residues. Therefore, the ribosome prevents premature co-translational misfolding by the unfolded nascent chain while lowering the entropic penalty of protein folding24,25,26,27. Secondly, a host of dedicated chaperones engage nascent chains at the ribosome28. The typical example of this is Trigger Factor (TF) in E. coli, which directly interacts with both the nascent chain and the ribosome, thereby preventing off-pathway interactions29. In eukaryotes, co-translational chaperones are most well-studied in S. cerevisiae, in which Nascent polypeptide Associated Complex (NAC) and Ribosome Associated Complex (RAC) directly engage the ribosome and interact with the nascent chain near the ribosome exit tunnel28. RAC recruits an Hsp70-type ribosome-associated chaperone called Ssb, which prevents premature folding through binding-release cycles30,31,32. Still, these mechanisms are not foolproof as an estimated one-third of newly synthesized polypeptides are targeted for proteasomal degradation, either through mistakes in translation or inability to attain the native fold33.

In this work, we describe a method to identify regions that are unsatisfied during translation and potentially vulnerable to premature co-translational misfolding. To do this, we quantify the time delay incurred by a residue between its addition to the nascent chain and the addition of all the rest of its native interaction partners, a metric for which we coined the term “Native Fold Delay” (NFD). Using the NFD algorithm, we show that many proteins contain residues with NFDs in the range of minutes, especially at eukaryotic translation rates. Furthermore, we establish that residues with the longest NFDs tend to be in well-structured, buried parts of globular proteins and are often part of predicted aggregation-prone regions (APRs). In addition, we show that in vivo, the yeast co-translational Hsp70 chaperone Ssb preferentially engages native fold-delayed regions. Aggregation propensity in these Ssb binding sites correlates with co-translational aggregation upon Ssb knockout. Both these findings suggest that regions of long NFD are indeed at risk of co-translational misfolding and aggregation. In support of this, we further show that proteins that are more frequently co-translationally ubiquitinated have long NFDs.

Results

Protein translation is orders of magnitude slower than protein folding

To visualize the differences in timescales of protein folding and translation rates, we directly compare folding rates and estimated translation times for 133 single-domain globular proteins that have experimentally recorded in vitro refolding rates from denaturing conditions reported in the Protein Folding DataBase (PFDB)34 (Fig. 1). The proteins in this database cover all structural topological classes (α, β, α/β, and α + β) and have an average length of 108 residues (Supplementary Fig. 1). The PFDB contains information on proteins from a wide array of species, and for a lot of these, an accurate translation rate has never been established. Therefore, translation times were estimated by multiplying protein lengths with an average translation rate. We assumed a relatively fast translation rate of 20 aas/s for all prokaryotic proteins and five aas/s for all eukaryotic proteins5,6,7.

Distribution of average folding times versus estimated average translation times of 133 proteins in the Protein Folding Database (PFDB34). Arrows show differences in folding and translation times for individual proteins. Yellow arrows indicate proteins for which the average translation time is slower than the average folding time, blue arrows indicate proteins for which the average translation time is faster than the average folding time.

Despite this, the distributions of translation times and folding times are clearly separated (Fig. 1). Translation times are typically on the order of seconds, whereas folding times range from microseconds to seconds, and in 126 of 133 cases (95%), the in vitro refolding time of the full-length protein is shorter than the time estimated to complete its translation (Fig. 1). Moreover, we here consider the time it takes for an entire polypeptide chain to cooperatively fold to its native conformation. Local protein conformational dynamics are generally even faster, ranging from nanoseconds to microseconds35. As a result, for most proteins, folding is a co-translational process that starts as soon as the N-terminal part of the protein emerges from the ribosome tunnel and long before the full-length protein chain has been synthesized and released from the ribosome.

Vectorial protein translation imposes spatial and temporal constraints on folding

Protein folding studies, both in vitro and in the cell, have demonstrated that protein topology (i.e. the sequence order in which the structural elements of the tertiary fold occur in the primary sequence) is a key determinant of folding rates and efficiencies3,36. Protein topological complexity is often described by Contact Order (CO), a metric which calculates the average sequence distance separation of native interactions3. As shown in Fig. 1, translation is relatively slow compared to folding. This means that during protein translation topology restricts folding not only spatially but also temporally: residues that are separated spatially in the primary sequence are also separated temporally as interaction partners towards the C-terminal end of the protein will simply not exist until they have been translated. Inspired by and building on CO and a previous study37, we here propose a metric that accounts for these temporal and topological constraints, for which we have coined the term “Native Fold Delay” (NFD). For each residue (i) in a protein sequence, NFD measures the sequence distance (ΔSi,j), in residues, from its furthest away C-terminal interactor (j):

Therefore, NFD measures the number of residues that need to be synthesized before residue i can engage with all its native interaction partners. NFD can also be expressed in time units by factoring the elongation rate (τk) for each codon k in the interval between residues i and j:

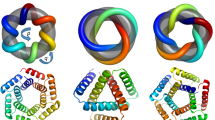

In other words, NFD measures the minimum amount of time it takes for all the native interaction partners of a residue to be available. The NFD calculation is schematically represented in Fig. 2a–d. Figure 2a shows the native fold for a hypothetical small globular protein. From this native structure, all interactions are mapped, resulting in a contact map. While during post-translational folding all contacts are available simultaneously (Fig. 2a), in the co-translational paradigm, the contact map changes over time as the polypeptide emerges from the ribosome (Fig. 2b–d). For example, residue 5 interacts with residue 24 in the native structure (residues outlined in red in panels Fig. 2a–d). As residue 5 emerges from the ribosome, this interaction is not available as residue 24 has not yet been added to the polypeptide chain (Fig. 2b, c). Therefore, residue 5 cannot complete all its native interactions until residue 24 has been synthesized and exits the ribosome, becoming physically accessible (Fig. 2d). As a result, residue 5 incurs a NFD of 19 aas. Importantly, residue 24 has practically no NFD as all its long-range interaction partners (residues 5 and 6) have already been added to the polypeptide when it emerges from the ribosome exit tunnel. The latter highlights the key difference between NFD and CO. CO is a spatial metric, measuring the sequence separation between interacting residues. Because of this, a high CO value is assigned to both residues 5 and 24 since they make the same long-range interaction with each other. In contrast, NFD incorporates the vectorial nature of protein translation, converting the spatial information captured by CO into a temporal metric.

A Above, schematic representation of the globular native structure of a hypothetical protein. Amino acids are colored in a gradient from N-term (blue) to C-term (red). Residue 5 interacts with residue 24 in the native structure, both outlined in red. Below, the contact map of the native structure shows that all interactions are simultaneously available during post-translational folding. B–D In the co-translational folding paradigm, the contact map evolves over time as the nascent chain exits the ribosome tunnel. Solid lines indicate available interactions, while dotted lines indicate interactions that are not yet accessible, as their interaction partners have not yet emerged from the ribosome. B Contact map as residue 5 emerges from the ribosome. Residue 24, its interaction partner, is not yet synthesized, leaving the interaction unavailable. C As the polypeptide elongates, long-range interactions begin to form. D Contact map as residue 24 emerges from the ribosome. At this point, all native interactions for residue 5 are available. The NFD for residue 5 is 19 amino acids, representing the time between its emergence from the ribosome and the availability of its most C-terminal interaction partner, residue 24. Note that schematic is not to scale and is meant for illustrative purposes only.

As an example, Fig. 3a–c show the NFD calculation for the E. coli peptidyl-prolyl isomerase B (PPIase B, UniProt code P23869) protein. PPIase B is an abundant cytoplasmic enzyme with a length of 164 residues. Its functional form is a globular shape comprised of beta sheets and alpha helices separated by several random coils (Fig. 3a). While PPIase B has an average folding time of about 600 μs, its estimated translation time is eight seconds (assuming an average translation rate of 20 aas/s). Clearly, the timescales of folding and translation here are vastly different, and PPIase B is likely to start folding co-translationally. Figure 3b and c show the contact map calculated from the PPIase B native structure and the per-residue NFD profile, respectively. PPIase B contains a beta-sheet consisting of a strand close to the N-terminus (E1) and a strand close to the C-terminal end in the primary sequence (E8). Strand E1 cannot be fully stabilized in its native conformation until strand E8 has been synthesized, requiring 160 residues to be produced. This means that the full set of native interactions of strand E1 are not satisfied for about eight full seconds. On the other hand, strand E8 has a negligible NFD, as its interaction partners have all been produced when it emerges from the ribosome. Notably, whereas NFD trends downwards from N- to C-term, CO follows a more symmetrical pattern as it does not capture the directionality of protein translation (Fig. 3c).

A Cartoon representation of the native structure of the E. coli peptidyl-prolyl isomerase B (PPIase B, UniProt code P23869) enzyme as predicted by AlphaFold. Residues are colored on a gradient from N-term (blue) to C-term (red). B Contact map of PPIase B showing for each residue its furthest away interactor based on the structure in (A). C Per-residue NFD calculation (rainbow) and per-residue CO (gray) for PPIase B. D Mean NFD of domains in the SCOPe40 dataset versus the relative residue position in the domain (scaled from 1 to 100). Error bars indicate standard deviation. E Domain length versus mean NFD of the SCOPe40 dataset. Red points indicate domains of exactly 101 amino acids, the domain length with the most datapoints in the SCOPe40 database. For visualization purposes, domains longer than 1000 residues are not displayed. Pearson correlation analysis shows a strong positive relationship (R = 0.89, p < 2.2e-16), indicating that longer domains generally have higher mean NFD values. F Violin plots showing the distribution of mean NFD for the domains of exactly 101 amino acids per SCOP class. Green points indicate a representative example in each group (domains with mean NFD closest to the median of their respective SCOP class). The significance of the differences in distributions was assessed through a two-sided Wilcoxon Rank Sum test with Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparisons. P-values of multiple comparisons are indicated for significant differences (p-value < 0.05). G NFD profiles of the representative examples for each SCOP class indicated in (K). H Cartoon representation of the native structure of a peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase from S. cerevisiae (UniProt code P14832) as predicted by AlphaFold. Residues are colored on a gradient from N-term (blue) to C-term (red). I Contact map of the structure in (M) showing for each residue its furthest away. J Per-residue NFD (rainbow) and per-residue CO (gray) calculation for the structure in (H).

To explore general NFD patterns across different protein topologies, we ran NFD analyses on the protein domains of the SCOPe40 dataset. This dataset contains single-domain structures that have been manually classified based on their architectures and filtered so that no two domains in the set have more than 40% identical sequences38,39. Reflecting the vectorial nature of protein translation, NFD has both spatial and temporal implications. First, the NFD profiles of proteins display an N- to C-terminal gradient: N-terminal elements generally incur larger NFDs than more C-terminal elements (Fig. 3d). In addition, domain size is a big determinant of NFD, as the longer a polypeptide chain, the more potential there is for long-range interactions, leading to larger NFDs (Fig. 3e). On top of length, NFD also reflects the topology of the translated protein. Indeed, even when considering proteins of identical length (101 aas), proteins from different SCOPe classifications have different NFD patterns (Fig. 3e, f). More complex protein topologies have larger NFDs and present more pronounced N- to C-terminal NFD gradients, resulting in different profiles for alpha-helical or beta-sheet structured domains (Fig. 3f, g). Interestingly, NFD profiles of large multi-domain proteins often display a sawtooth profile reflecting the domain dependence of N- to C-terminal NFD gradients (Supplementary Fig. 2).

On top of topology, NFD is also dependent on translation rates, which can vary strongly between species. Figure 3h shows the AlphaFold predicted structure of a peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase (PPIase, UniProt code P14832) from S. cerevisiae, which is homologous and structurally very similar to PPIase B from E. coli (RMSD between 104 pruned atom pairs is 0.714 Å). As is the case for PPIase B, the N-terminal domain has a strand near its N-terminus (E1) that forms contacts with a strand at the C-terminus of the domain (E8), resulting in long NFD values for E1 (Fig. 3i, j). Although the NFDs for the N-terminal strands in both proteins are very similar when expressed in a number of residues, the relatively slower translation rates of S. cerevisiae (estimated to be around five aas/s on average) means that strand E1 has to wait for about 32 seconds to make all its native contacts, as opposed to just 8 seconds for its E. coli counterpart. Therefore, differences in translation rates of different organisms can cause domains with very similar folds to incur vastly different NFDs.

Sequence segments with long NFD often consist of aggregation-prone tertiary structural elements that stabilize the native structure

Having established the NFD algorithm, we next used it to explore NFD patterns on a proteome-wide scale. The near-exhaustive availability of AlphaFold-predicted structures combined with the computationally inexpensive nature of our algorithm allows us to calculate NFD for all residues across entire proteomes40,41. In addition, AlphaFold models provide a confidence measurement to assess the relative position of two residues within the predicted structure, called the Predicted Aligned Error (PAE). We used this metric to filter out interactions between residues whose relative positions with respect to each other are predicted with low confidence since these interactions most probably do not occur in the actual structure, as is the case for contacts with disordered regions or some contacts between distinct domains. (Supplementary Fig. 3).

We calculated the NFD incurred by all residues in the E. coli and S. cerevisiae proteomes, assuming flat average translation rates of 20 aa/s and five aas/s, respectively5,6,7. Interestingly, most proteins have at least one residue that has to wait for tens of seconds for the translation of all its native interacting residues (Fig. 4a). Binning proteome-wide NFDs however, reveals that most residues have short NFDs as they interact only with their neighbors ( ± 5 aa). While intermediate NFDs are relatively rare, about 23% of residues in S. cerevisiae proteome incur NFDs of more than 10 seconds (Fig. 4b), while the same is true for 7% of E. coli residues (Supplementary Fig. 4a). Specific secondary structures are more likely to incur NFD (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Fig. 4b). Logically, residues in random coils (C) are depleted in residues with long NFDs as they make few and mostly local contacts. On the other hand, helical structures (G, H, and I) are dominated by short-range contacts, yielding average NFDs. Pi-helices (I) have longer NFDs than alpha-helices (H), which is consistent with the fact that backbone interactions in pi-helices occur at an interval of five residues, where this is four residues for alpha-helices and three for 3-turn helices (G). Finally, beta-structured elements (B, E) are enriched in residues with the longest NFDs since contacts between beta strands are generally more long-range than those between residues in alpha helices3.

A Distribution of residues with the maximum NFD (log scale) for each protein in E. coli (n = 3910) and S. cerevisiae (yeast; n = 5812). Vertical dotted lines indicate NFDs corresponding to 1 second, 10 seconds, and 1 minute. B Histogram showing the number of residues in yeast proteins grouped by NFD bins. C Enrichment of residues with NFDs between 1–10 seconds or longer than 10 seconds relative to the background for different secondary structure categories in yeast proteins. DSSP categories: C, coil, B, β-bridge, E, extended strand in β-sheet conformation, G = 3-turn helix, H = 4-turn helix, I = 5-turn helix, S, bend and T, hydrogen bounded turn. D Enrichment of residues with NFD between 1-10 seconds or longer than 10 seconds relative to the background for all amino acid types in yeast proteins. E–G pLDDT scores (E), solvent accessibilities (F), and predicted stabilities (G) for residues in yeast proteins grouped by NFD bins. H Percentage of residues in APRs (TANGO score > 5) for different NFD bins in yeast proteins. Residues in transmembrane domains and signal peptides were filtered out to avoid bias. I Aggregation strength (TANGO score) for residues in APRs of yeast proteins grouped by NFD bins. In box plots (E, F, G, and I), the box shows interquartile range, the line indicates the median and the whiskers span 1.5 times the interquartile range. Notches around the median indicate an approximate 95% confidence interval. Statistical significance was assessed using a two-sided unpaired Wilcoxon test with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Statistical significance: ****p < 0.0001, ns, not significant.

Looking at the sequence composition of segments with long NFDs, we find them to be enriched in aromatic and aliphatic residues (Fig. 4d and Supplementary Fig. 4c). This makes sense as these residues are often buried in the hydrophobic cores of globular proteins, where they make many tertiary contacts. Exploring this further, we find that regions of long NFDs are often structurally ordered – as indicated by the AlphaFold pLDDT score, which inversely correlates with disorder – (Fig. 4e and Supplementary Fig. 4d) and indeed constituted of buried residues – as shown by their relatively low solvent accessibility (Fig. 4f and Supplementary Fig. 4e). Furthermore, regions of long NFDs are usually important for the thermodynamic stability of the native structure, as shown by their low predicted free energies (Fig. 4g and Supplementary Fig. 4f). Given their propensity for beta-sheet formation and hydrophobic nature, we asked whether regions of long NFDs tend to be aggregation-prone. Indeed, we find that the proportion of residues in aggregation-prone regions (APRs) substantially increases with NFD (Fig. 4h and Supplementary Fig. 4g), although the distribution of their aggregation propensities remains relatively similar between intermediate and long NFDs (Fig. 4i and Supplementary Fig. 4h).

Binding sites of the co-translational chaperone Ssb are characterized by long NFD

Aggregation-prone exposed regions of high hydrophobicity are the preferred binding sites of many molecular chaperones, including Hsp70s31,42,43. It has been proposed that Hsp70s bind to these regions to delay the folding of newly forming polypeptides until the residues required for folding emerge from the ribosome, thus preventing the formation of non-native interactions43,44. Given that NFD may correlate to co-translational exposure and that regions of long NFD tend to be hydrophobic, we hypothesized that NFD could help explain the engagement of specific segments of the nascent chain by chaperones. To address this question, we used a dataset containing the binding footprints for the co-translational chaperone Ssb from S. cerevisiae, obtained by Döring et al.31 using selective ribosome profiling (SeRP). These Ssb binding footprints indicate the specific codons that are being translated by ribosomes at the time Ssb binds to the emerging polypeptide chain (Fig. 5a).

A Schematic of Ssb interacting with a nascent chain during translation. RAC recruits Ssb to the nascent chain once it reaches a length of around 50 aas. B NFD of nascent chains aligned to the start of Ssb binding footprints (peak width of 6–8 aas; n = 3371) compared to NFD of nascent chains aligned to randomly sampled positions (n = 4000) from the same proteins. Solid lines represent the median value at each position, while shaded regions indicate 95% bootstrapped confidence interval (CI). C Relative enrichment of CO scores of nascent chains aligned to the start of Ssb binding footprints (peak width of 6–8 aas; n = 3371). The solid line represents the median, while the shaded region indicates the 95% bootstrapped CI. D Overlap between Limbo regions and Ssb binding sites (peak width of 5–11 aas) E NFD of Limbo regions that overlap with Ssb binding sites (blue; n = 3554) compared to Limbo regions without Ssb binding (green; n = 8811). The solid line represents the median, while the shaded region indicates the 95% bootstrapped CI. F NFD profile of the MTAP protein. Limbo regions overlapping with Ssb binding sites are highlighted in blue, while those without Ssb binding are in green. G Difference in median NFD values between aligned Ssb binding footprints and randomly sampled positions (as in B). The dotted line indicates the average peak width of Ssb binding sites. H NFD of nascent chains aligned to the start of Ssb binding footprints with peak width of 5 (n = 1412), 6 (n = 1277), 7 (n = 1111), 8 (n = 983), 9 (n = 945), 10 (n = 897) and 11 (n = 707) aas. Solid lines represent the median. (I) Average median NFDs within the Ssb binding region (-53 and -35 codons) grouped by peak width of aligned Ssb binding footprints (sample sizes as in panel H). Error bars show standard deviation, and the line represents the linear regression fit. All experimental Ssb binding footprints used are derived from31.

We carried out a metagene analysis by aligning the starting site of Ssb binding ribosome footprints across the S. cerevisiae proteome and calculated the median NFD value at each position. A distinct NFD peak was revealed at around 50 aa towards the N-terminal side (Fig. 5b). This is the exact distance that has been reported to exist between the Ssb footprint, i.e., the sequence segment protected by the ribosome at the moment of Ssb engagement with the nascent chain, and the actual Ssb binding site31,45. Indeed, at these positions, we observed some of the characteristic sequence and structural properties of Ssb binding motifs31,32, including enrichment in positively charged residues and β-sheet propensity (Supplementary Fig. 5a, b), and a depletion of intrinsically disordered regions (Supplementary Fig. 5c). This suggests that the observed NFD peak is directly associated with the regions engaged by Ssb. A similar NFD pattern was observed using a different published dataset of Ssb binding regions32 (Supplementary Fig. 5d). On the other hand, a dataset of Ssb binding regions generated in the absence of RAC (RACΔ31), a cochaperone that is required for high-affinity binding of Ssb to its substrates, did not show any peak around these positions (Supplementary Fig. 5e). Interestingly, an additional smaller NFD peak can be observed between -16 and -6 aa from the start of Ssb binding footprints, which is approximately 36 residues downstream of the main Ssb binding region (Fig. 5b). This peak might correspond to other Ssb binding regions, as these have been previously described to occur in proteins every 36 amino acids, on average46. Together, these results indicate that regions bound by Ssb have, on average, long NFDs. We next asked whether the same conclusions could be drawn solely from CO, i.e. whether Ssb simply has a preference for regions that make long-range contacts, regardless of the directionality of these contacts. However, doing the same analysis with CO yielded no discernable signatures, suggesting that Ssb binds preferentially to regions that make long-range contacts that are still not available (Fig. 5c).

Intriguingly, despite Ssb recognition motifs being very common within protein sequences46, SeRP data showed that many putative binding sites in vitro are actually ignored in vivo31,32. Thus, we investigated whether putative chaperone binding motifs with short NFDs are skipped co-transitionally by Ssb. To investigate this, we used the computational tool Limbo to predict chaperone binding sites in yeast proteins47. Although Limbo was trained to predict E. coli DnaK binding sites, these motifs have been shown to be very similar to Ssb binding regions31. In fact, Limbo regions are enriched around 50 residues upstream of Döring et al.31. Ssb footprints (Supplementary Fig. 5f) and match with half of the identified Ssb binding regions (Fig. 5d). On the other hand, only 22% of all Limbo predicted regions matched with an Ssb binding region (P-value < 0.001 by Fisher exact test), suggesting that additional factors beyond the amino acid sequence determine Ssb binding. To further corroborate this, we produced peptide arrays on cellulose membranes containing polypeptide segments of the S. cerevisiae proteome with high LIMBO scores. These sequences were divided into two groups for analysis: those identified as engaged by Ssb in vivo, based on the data produced by Döring et al.31, and those that are not engaged by Ssb in vivo, despite their high LIMBO scores. As controls, we took random sequences from the same set of proteins that were negative for LIMBO. We then tested Ssb binding to these sequences in vitro (Supplementary Fig. 5g–i). Firstly, we found that Ssb binds more strongly and frequently to high Limbo-scoring peptides than to random control peptides, confirming that Limbo captures part of the Ssb-binding determinants. Secondly, we find that there is no significant difference in binding in vitro between the set of peptides engaged by Ssb in vivo versus sites that are non-engaged in vivo. Hence, our data suggests that Ssb binding in vivo is not solely determined by the presence of a compatible sequence motif, but additional factors, such as RAC45, need to be considered. Comparing all Limbo-predicted regions that matched and did not match with Ssb binding regions, we observed that those that are not engaged by Ssb in vivo have shorter NFDs (Fig. 5e). Notably, Ssb binding and non-Ssb binding LIMBO regions have similar hydrophobicities, showing that the difference in NFD does not arise from a difference in amino acid composition (Supplementary Fig. 5j). As an example, the protein S-methyl-5’-thioadenosine phosphorylase (MTAP) has six predicted chaperone binding sites based on Limbo (Fig. 5f). Out of these, only two were experimentally identified in vivo and reside in regions with long NFDs. Conversely, the other four predicted binding sites are in regions with shorter or even negligible NFDs. Thus, it seems then that Ssb not only engages their targets based on amino acid composition alone but also on the availability of unsatisfied native interactions, which is captured by the NFD metric. This does of course not mean that long NFDs imply Ssb binding. As illustrated in Fig. 5f, many regions with long NFDs are not engaged by Ssb since they lack the right amino acid makeup31.

As discussed by Döring et al. in the original Ssb SeRP publication, the maximal lifetime of the Ssb-Nascent chain complex can be extrapolated from the width of Ssb-binding peaks31. The average width of the Ssb peaks considered in our analysis is 6.9 aas, which corresponds to an average translation time, and hence Ssb engagement time, of 1.38 seconds. Intriguingly, we found that NFDs of experimentally confirmed Ssb binding regions are, on average, 1.44 seconds longer than NFDs from regions of the same proteins that were sampled at random (Fig. 5g). This suggests that regions that have a NFD that is equal to or longer than the Ssb binding time can actually be engaged by the chaperone. To corroborate this, we asked whether Ssb binding sites with longer engagement times, i.e., wider footprints, have longer NFDs. For Ssb footprints ranging in size from 5 to 11 aas, we indeed observed a strong positive correlation between the NFD values at positions -53 to -35 (Ssb binding region) and the footprint size (Fig. 5h, i). Moreover, the slope of this correlation roughly corresponds to the addition of one amino acid (Fig. 5i). The same analysis outside the Ssb binding region showed weaker and not significant correlations (Supplementary Fig. 5k, l).

Collectively, our findings suggests that both amino acid composition and the availability of unsatisfied native interactions, as captured by NFD, determine co-translational Ssb engagement. This highlights the importance of considering not just sequence motifs but also structural and kinetic contexts in understanding chaperone interactions.

Proteins with long NFDs are associated with co-translational misfolding and aggregation

We have shown that Ssb preferentially engages specific amino acid motifs with long NFDs. To corroborate this, we used a dataset produced by Willmund et al., who mapped Ssb clients across the S. cerevisiae proteome and showed that the deletion of Ssb leads to widespread aggregation of newly synthesized polypeptides30. We used this dataset to assess whether Ssb clients indeed have longer NFDs and whether proteins with long NFDs are disproportionately affected by Ssb deletion. To this end, we assigned a single value to each protein by simply summing the NFDs of individual residues. As expected, Ssb clients generally have larger total NFDs than proteins that are not engaged by the co-translational chaperone (Fig. 6a). Furthermore, Ssb clients that aggregate upon deletion of Ssb (SSBΔ30) have, on average, slightly larger total NFDs than Ssb substrates that remain soluble (Fig. 6a). To further corroborate the link between NFD and aggregation, we also investigated whether, inversely, proteins with a larger total NFD are also more likely to aggregate. In order to do so we performed a logistic regression using NFD as the input variable and aggregation status as the response and found that proteins with larger total NFDs are slightly more likely to aggregate upon Ssb deletion (balanced accuracy of 0.53, with a significance level of p = 0.014 and a coefficient value of 0.16; Supplementary Fig. 6a, b). In other words, from the proteins that are bound by Ssb, those with long NFDs have a marginally increased tendency to aggregate upon Ssb deletion.

A Total NFD of actively translated proteins in S. cerevisiae grouped based on their co-translational interaction with Ssb (bound: n = 1913; not bound: n = 910)30. Ssb-bound proteins are further stratified as soluble (n = 1495) or aggregated (n = 418) in SSBΔ cells. B NFD across nascent chains aligned to the start of Ssb binding footprints with peak widths between 5–11 aas, in proteins that aggregate or remain soluble in SSBΔ cells. The dataset includes 1917 Ssb binding sites in aggregating proteins and 5415 in soluble proteins. Lines represent the median NFD value at each position, while shaded regions indicate the 95% bootstrapped confidence intervals. C Number of APRs per 100aa in soluble (n = 1495) and aggregated (n = 418) Ssb-bound proteins in SSBΔ cells. D, E Proportion of APR starting sites across codon bins relative to the start of Ssb binding footprints with peak widths between 5-11 aa in proteins that aggregate (D) or remain soluble (E) in SSBΔ cells. A two-sided Fisher’s exact test with FDR correction was used to compare the proportion of APR starting sites in the Ssb binding region against the other regions. Asterisks indicate statistical significance (defined below). F Total NFD of yeast proteins under physiological conditions (n = 107) or upon exposure to arsenite stress (n = 140) compared to background (MS proteome; n = 1179)48. G Total NFD of proteins co-translationally ubiquitinated under physiological conditions (n = 600)51. As background we use the translatome (n = 1790) reported by Willmund et al.30. In box plots (A, C, F, and G), the box shows interquartile range, the line indicates the median and whiskers span 1.5 times the interquartile range. Notches around the median indicate an approximate 95% confidence interval. Statistical significance was determined using a two-sided unpaired Wilcoxon test with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Statistical significance: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001, ns = not significant.

To examine this association in more detail, we looked at the metagene NFD profile of specific Ssb binding sites of aggregated and soluble Ssb substrates based on Döring et al.31 ribosome footprints. Ssb binding regions in proteins that aggregate in SSBΔ cells have, on average, a one-second longer NFD compared to binding regions in proteins that do not aggregate (Fig. 6b and Supplementary Fig. 6c, d). We next investigated whether proteins in the aggregated fraction upon Ssb deletion have higher intrinsic aggregation propensities. Although these proteins have a similar number of APRs per length unit (Fig. 6c), we found that proteins that aggregate upon Ssb deletion have a significantly higher proportion of APRs in their Ssb binding regions (positions -53 to -35) compared to other regions in the same proteins of the same size (Fig. 6d). In contrast, proteins that remain soluble have a significantly lower proportion of APRs in their Ssb binding regions (P-value < 0.0001 by Fisher exact test), similarly to other regions from the same proteins (Fig. 6e). This suggests that aggregation-prone Ssb binding regions favor protein aggregation in SSBΔ cells.

To further corroborate these findings, we analyzed a dataset produced by Jacobson et al. who identified proteins that aggregate upon treatment of yeast cells with trivalent arsenite [As(III)]48, a metalloid known to cause misfolding and aggregation by interfering with the folding of nascent proteins49. Again, we found that proteins that aggregate under arsenite stress have significantly larger total NFDs (Fig. 6f). In eukaryotic cells, misfolded proteins are tagged through ubiquitination for degradation50. Duttler et al.51 showed that a subset of cytoplasmic nascent polypeptides is often co-translationally ubiquitinated. Re-analysis of this dataset revealed that proteins that are co-translationally ubiquitinated have significantly larger total NFDs compared to other, non-ubiquitinated but abundantly translated yeast proteins (Fig. 6g). To further test this association, we also investigated whether, inversely, proteins with a larger total NFD are also more likely to be ubiquitinated. In order to do so we performed a logistic regression with NFD as the input variable, and co-translational ubiquitination as the response and found that proteins with larger total NFD are more frequently co-translationally ubiquitinated (balanced accuracy of 0.66, with a significance level of p < 0.001 and a coefficient value of 0.48; Supplementary Fig. 6e, f). Therefore, proteins with long NFDs are also more often co-translationally ubiquitinated.

Together, our findings suggest that proteins with long NFDs are at a higher risk of premature co-translational misfolding and aggregation, particularly under proteotoxic stress conditions.

Discussion

In recent years, it has become clear that co-translational protein folding and complex formation is probably the most common folding mechanism across proteomes. Given that protein conformational fluctuations are orders of magnitude faster than translation, both processes have co-evolved, which explains why in vivo co-translational folding is more efficient than in vitro protein refolding13,24. Mechanistically, however, co-translational protein folding faces the challenge of balancing the highly cooperative nature of protein stability, driven by long-range tertiary interactions, with the temporal delay in the apparition of native interaction partners as the protein is synthesized sequentially. To model this, we introduce NFD, a metric designed to quantify the combined impact of translation dynamics and protein topology on co-translational folding. Conceptually, NFD resembles the simple yet widely used and validated CO metric, as it captures topological complexity by the separation between interacting residues in the native structure3. However, in contrast to CO, NFD only considers interactions directed toward the C-terminus, reflecting the inherent directionality of protein translation. Moreover, NFD also integrates the temporal separation between such native interactions by factoring translation elongation rates. For simplicity, throughout the analyses in this study, we assumed a uniform elongation rate across all codons in a transcript. However, our method can incorporate individual elongation rates obtained through techniques such as ribosome profiling52, which would enhance the accuracy of the NFD metric.

Our data shows that regions with long NFDs are relatively common in proteins and can last for tens of seconds and even up to minutes (Fig. 4a, b), a vast period on a molecular timescale53. Nevertheless, in spite of long NFD values, it is clear that co-translational folding is a very efficient process. One reason is that most residues have short NFDs (e.g., about two-thirds of the residues in the yeast proteome have NFD of less than 2 seconds, Fig. 4b), allowing local structural propensities to shape co-translational folding. This is in agreement with the early successes of protein structure prediction using protein fragments54 but also mechanistically fits with the recent finding that co-translational folding lowers the entropic penalty of folding by destabilizing the unfolded state, thereby facilitating the formation of folding intermediates27. However, due to the more complex topologies of some protein folds, such as those composed of parallel ß-sheets for example, about one-third of residues in the yeast proteome (and this is valid across pro- and eukaryotic proteomes) possess long NFD values, implying that they have to wait significant amounts of times ( >10 s) before their native interaction partners emerge from the ribosome. The question then is whether these unsatisfied residues represent a risk for protein misfolding and, if so, how this is mechanistically handled within the framework of co-translational folding.

As native interactions cannot be satisfied by local interactions in regions with long NFD, they cannot be easily stabilized by the formation of native-like folding intermediates. An energetically expensive solution would be the formation of transient non-native intermediate structures that are unraveled once other parts of the polypeptide have been synthesized. This would require the breaking of bonds, representing an energy barrier in the co-translational folding funnel19. For example, the formation of non-native alpha helices has been observed in the vestibule of the ribosome tunnel for several beta-sheet proteins55,56. It has been proposed that the temporal formation of alpha helices can protect the emerging polypeptide from misfolding while entropically facilitating the search for native interactions as more residues are added to the nascent chain56.

Apart from intrachain interactions, fold-delayed regions might be temporarily stabilized through interactions with PQC elements such as the ribosome and molecular chaperones. Indeed, the ribosome can destabilize non-native folding intermediates by interactions with the nascent chain, thereby preventing premature folding until a critical chain length is reached11. Interestingly, the ribosomal surface interacts predominantly with segments that contain positively charged and aromatic amino acids25. These specific residues are enriched in regions with long NFDs (Fig. 4d) and are also preferentially found in chaperone-binding regions31,46. Thus, the ribosome could function as a holdase, sequestering hydrophobic native fold-delayed segments until their interaction partners have been synthesized. Our results show an association between NFD and co-translational chaperone engagement and dependence. In particular, we show that Ssb, a co-translational chaperone in S. cerevisiae, preferentially targets regions of long NFDs (Fig. 5). The authors who produced the Ssb data analyzed here found that in an in vitro peptide array - where there is no potential of folding - Ssb recognizes more binding sites than it does in vivo, suggesting that some interaction sites are skipped in vivo31. The authors attributed this discrepancy to additional regulation by cochaperones in vivo. However, NFD offers a different explanation: the skipped sites are simply not available for Ssb binding. In support of this, we show that the lifetime of the Ssb-Nascent chain complex correlates directly to the NFD of the bound segment (Fig. 5h, i) and that predicted chaperone binding sites that do not engage Ssb in vivo have shorter NFDs (Fig. 5e). Therefore, NFD could provide an additional triaging parameter for Ssb to recognize vulnerable regions: hydrophobic regions where native interactions remain unsatisfied for longer periods of time and hence more at risk for misfolding are more readily engaged by Ssb than hydrophobic regions that can be satisfied by local native interactions.

Despite these protective mechanisms, a small subset of proteins is susceptible to co-translational ubiquitination under physiological conditions, suggesting premature misfolding51. We showed that these proteins have significantly longer NFDs than the background translatome (Fig. 6g). However, the potential risk of native fold-delayed regions becomes clearly apparent when the tightly regulated co-translational folding process is perturbed. For example, deletion of the Ssb chaperone or chemically inhibiting in vivo protein folding with trivalent arsenite [As(III)] disproportionately causes the aggregation of proteins with long NFDs (Fig. 6a, f). Slower decoding would increase NFDs, which can trigger co-translational misfolding if a nascent chain is trapped in an off-pathway conformation. Interestingly, it was found that 70% of the proteins that aggregate in the absence of Ssb, which we show are characterized by long NFDs, also aggregate after inducing ribosome pausing through loss of U34 modification23.

Our analysis revealed that regions with long NFDs often occur in structured, hydrophobic regions that are meant to be buried within the hydrophobic core of the structure of globular proteins (Fig. 4). These regions are likely to engage in homotypic off-pathway interactions, leading to aggregation. Moreover, we showed that Ssb binding sites in proteins that aggregate upon Ssb deletion align more often with APRs than those in Ssb clients that do not aggregate (Fig. 6d, e). Together, these observations suggest that APRs with long NFDs can lead to protein aggregation, requiring PQC elements to suppress it. This begs the question whether native fold-delayed APRs could aggregate co-translationally, especially in the context of polysomes where there is a higher local concentration of nascent polypeptides exposing identical APRs.

NFD merges two important concepts: topological complexity and translation rate. The latter varies vastly between organisms and even between different cell types and conditions57. One could argue that a slower translation rate allows for the successful co-translational folding of more complex structures. In support of this, it was shown decades ago that eukaryotic translation systems more efficiently produce modular proteins than their prokaryotic counterparts58. Interestingly, slowing down translation speed in bacteria is often enough to enhance the folding efficiency of recombinant eukaryotic proteins59. However, our analyses show that this comes at a cost since slower translation rates mean longer NFDs, which can pose a risk to folding. Hence, while slowing down translation rates opened the door to more complex folds, it may have also necessitated the co-evolution of a more elaborate network of co-translational chaperones to mitigate the associated increase in NFD. This may be one of the reasons for the existence of a much more extensive co-translational chaperoning system in eukaryotes than in prokaryotes60.

In summary, our study describes a method to quantify the temporal separation between native interacting residues that arises from protein translation. This method can be used to identify regions that are potentially susceptible to premature co-translational misfolding, especially upon proteotoxic challenges. A limitation of our method is that it only calculates the temporal separation between each residue and its most distant interactor. Since not all interactions are energetically equal, this could overstress the potential risk for some residues with long NFDs where the furthest interactor has a minimal impact on the native stability.

Methods

Protein folding vs protein translation rates

Protein folding rates were retrieved from PFDB, a standardized protein folding kinetics database (https://balalab-skku.org/PFDB/)34). This curated dataset contains folding rates derived from experimental data. To obtain data on the organism from which each structure was derived, PDB IDs as listed by the PFDB were queried in the RCSB database61. We thereby retrieved 133 structures with source organism annotations. From the reported folding rates at 25 degrees C (kf,), we calculated average folding times (calculated as 1/kf). For an estimation of the translation times, proteins from prokaryotic organisms were assigned translation rates of 20 aas/s, whereas proteins from eukaryotes were assigned translation rates of 5 aas/s5,6,7. For an estimation of the total translation time of a protein, we simply multiplied these translation rates by the number of residues in each protein studied.

SCOPe40 analysis

We analyzed NFD profiles of protein domains in the SCOPe40 dataset. This dataset contains single-domain structures that have been manually classified based on their architectures and filtered so that no two domains in the set have more than 40% identical sequences38,39. To establish a general pattern of NFD from N- to C-term within domains (Fig. 3d), residues were assigned relative positions by dividing their position in the domain by the domain length, multiplying by 100 and rounding off to the nearest integer. For each relative position, average NFDs and standard deviations were calculated. The average (or mean) NFD for a domain was calculated as the sum of the NFD of all residues in a domain divided by the domain length.

Proteome-wide analyses

AlphaFold structures (version 4) and their corresponding predicted aligned error (PAE) matrices for the full proteomes of Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae (yeast) were retrieved from the AlphaFold Protein Structure Database40,41. Genomic sequences for both species were retrieved from NCBI Genomes FTP server. AlphaFold structures were mapped to genomic sequences using the UniProt ID mapping tool. 3929 and 4363 proteins were successfully matched with their corresponding codon sequences for E. coli and yeast, respectively. The energies of the structures were minimized using the FoldX “RepairPDB” command, and stability calculations for each amino acid were performed using the “SequenceDetail” command62. Protein secondary structures and absolute solvent accessibility values were obtained with DSSP based on the AlphaFold structures63,64. Then, the relative solvent accessibility (RSA) values were calculated by dividing the absolute solvent accessibility values by residue-specific maximal accessibility values, as extracted from Tien et al.65. Disordered regions were defined using the pLDDT score provided in the AlphaFold models, as regions with low confidence scores (pLDDT <50) have been shown to overlap largely with intrinsically disorder regions66. To exclude biases arising from intrinsically disordered proteins, proteins with more than 90% disordered residues were filtered out of the data. Aggregation prone regions were defined with the TANGO algorithm (score > 5)67 at physiological conditions (pH at 7.5, temperature at 298 K, protein concentration at 1 mM, and ionic strength at 0.15 M).

Native Fold Delay

Native Fold Delay (NFD) profiles were determined from protein structures for all SCOPe40 domains and the E. coli and yeast proteomes based on AlphaFold models using the formulas described in the Results section. Residues were considered to interact if they contained non-hydrogen atoms within 6 Å. This threshold was chosen since it is commonly used to calculate other topological parameters, such as contact order3. For SCOPe40 domains, all residue interactions were considered as the structures were solved with experimental methods. Instead, for AlphaFold predicted models, interactions between two residues whose relative position to each other is low based on the Predicted Aligned Error (PAE) metric were filtered out. Specifically, we excluded interactions with an expected position error >6 Å.

We assigned a single NFD value to each protein to facilitate the proteome-wide NFD correlations in Figs. 3 and 6. The “mean NFD” values correspond to the mean of the NFD of individual residues in a structure. The “total NFD” values reported are simply the sum of the NFD of individual residues in a structure. These metrics provide a global view of the delay incurred by a polypeptide chain throughout its ribosomal production.

Contact order

Per-residue contact order (CO) profiles were determined from protein structures for the E. coli and yeast proteomes based on AlphaFold models using the formula described in the original CO paper3. However, the formula was adapted to have a per-residue value instead of one for the full-length protein. In other words, for every residue, the average sequence distance of all the contacts that it makes was calculated. Contacts were defined as interactions between non-hydrogen atoms of different residues within 6 Å. Contacts between two residues whose relative position to each other is low based on the Predicted Aligned Error (PAE) metric were filtered out. Specifically, we excluded contacts with an expected position error >6 Å.

Ssb binding footprints metagene analyses

Ssb binding footprints were obtained from Döring et al.31 and Stein et al.32. Nucleotide positions were transformed to amino acid positions by dividing them by three and rounding down. The lifetime of the Ssb-Nascent chain complex (engagement times) was extrapolated from the width of Ssb binding peaks. Specifically, only Ssb binding peaks with widths falling between 5 and 11 aas were selected for analysis. This range was chosen because higher widths might suggest additional binding and release cycles. A metagene analysis of the Ssb binding footprints was done by aligning the starting site of Ssb binding footprints. The NFD profile and the relative enrichment of different properties were calculated, across a range of -120 and 120 aas from the starting site of the Ssb footprints, per position using a rolling average of 3 and after removing empty positions.

As a control measure, random positions were sampled from the same proteins containing the Ssb footprints and the metagene analyses were repeated but aligning on these random positions.

Comparison between Ssb sites and Limbo regions

Predicted Hsp70 binding regions, here referred to as Limbo regions, were identified with the computational tool Limbo (score > 5)47. Döring et al.31. Ssb binding footprints with a width ranging from 5 to 11 aas were then compared to the Limbo regions. A Limbo region was considered to overlap with an Ssb site if it fell within a range of -55 aas from the starting residue to -35 aas from the ending residue of the Ssb footprints. Based on this criterion, Limbo regions were classified as either “Limbo Ssb binding” if there was an overlap or “Limbo no Ssb binding” if there was no overlap with any Ssb binding footprint. Average hydrophobicity (Kyte-Doolittle scale) was calculated for each Limbo region with R package “Peptides”.

Ssb1 purification

N-terminally His6-tagged yeast Ssb1 was purified by Ni2+-NTA affinity chromatography (ÄKTA start, GE Healthcare) with a Ni2+-NTA column (PureCube Ni-NTA Cartridge 5 ml, Cube Biotech) in HEPES buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.8, 100 mM KCl, 2.5 mM MgAc2, 1 mM PMSF, protease inhibitor mix: 1.25 μg/ml leupeptin, 0.75 μg/ml antipain, 0.25 μg/ml chymostatin, 0.25 μg/ml elastinal, and 5 μg/ml pepstatin A). His6-tagged Ssb1 was eluted using a 30 ml linear imidazole gradient from 50 mM to 500 mM. Imidazole was subsequently removed using a PD10 column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with HEPES buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 100 mM KCl, 2.5 mM MgAc2, protease inhibitor mix).

Ssb peptide membrane analysis

Peptide sequences were randomly selected from Limbo-predicted sites across the S. cerevisiae proteome, keeping the binding site lengths constant at 8 amino acids to ensure accurate production on the membrane. 120 Limbo sequences that correspond with in vivo Ssb binding sites as determined by Döring et al.31 were randomly selected, as well as 120 Limbo sequences that do not correspond with Ssb binding sites. As a negative control, 60 sequences of 8 amino acids in length that did not correspond to Limbo binding sites were also added to the set. To avoid bias towards protein types, these 60 sequences were taken from the same set of proteins that contain the Limbo binding sites represented on the membrane. Peptide arrays were produced through SPOT synthesis on acid-stable cellulose membranes using the Intavis Multipep RSi synthesis robot. Peptides were synthesized from C- to N terminus, starting with a GGS linker preceded by a PEG spacer (Aims-Scientific). Membranes were activated in 50% methanol for 10 minutes, followed by blocking in 4% BSA in TBS-T for 2 h. Membranes were then incubated with 100 nM Ssb in 25 mM Tris buffer supplemented with 10 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2 and 300 mM NaCl, and 0.1% Tween (Buffer A) for 1 h at room temperature. Membranes were then washed three times for 5 minutes in Buffer A, followed by an incubation with HRP anti-His tag antibody (BioLegend #652504) diluted 1/10000 for 45 minutes at room temperature. Membranes were then washed 5 times for 5 minutes in Buffer A and developed through chemiluminescence using a BioRad Chemidoc MP system (representative blot shown in Supplementary Fig. 5g). Three repeats’ membranes were analyzed in this manner. Spot intensities were quantified using the BioRad Image Lab software. Spot intensities were normalized to the median spot intensity in each membrane. The average of each spot across three repeats was then calculated. These averages were log-transformed, resulting in the data presented in Supplementary Fig. 5g). Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism as indicated in the figure caption.

NFD of proteins aggregating in Ssb knockout strain

We reanalyzed a dataset produced by Willmund et al.30. Through pulldowns of Ribosome Nascent Chain complexes followed by MS, the authors established the S. cerevisiae “translatome”. Through Ssb pulldowns, the translatome was then stratified into a group that interacts with Ssb co-translationally (“Ssb not bound” in Fig. 6a), and a group that does not. The authors further determined which proteins aggregate upon deletion of the Ssb chaperone, indicating they are dependent on Ssb for their solubility. Using this information, we divided the group of Ssb binders into a “soluble” and an “aggregated” fraction as shown in Fig. 6a.

NFD of proteins sensitive to Arsenite stress

Ibstedt et al. report the identification of aggregated proteins in S. cerevisiae both in physiological conditions (“Physiological” in Fig. 6f), as well as upon exposure to Arsenite stress (“Arsenic” in Fig. 6f)49. Aggregated fractions were separated through centrifugation and proteins in the aggregated fraction were identified through LC-MS. As a background, the authors used a previously established S. cerevisiae proteome, which we copied (“MS proteome” in Fig. 6f).

NFD of proteins that are co-translationally ubiquitinated

Duttler et al. produced a dataset of proteins that are co-translationally ubiquitinated under physiological conditions in S. cerevisiae51. They do not report a background proteome, so we compared the total NFD of the co-translationally ubiquitinated proteins with the translatome reported by Willmund et al.30

Logistic regression

A logistic regression using NFD values as an input variable and as the response variable either whether proteins are co-translationally ubiquitinated or not or whether they aggregate upon Ssb deletion or not was made. This was done in R using package called “stats”. Since the number of observations in each class is substantially different, random undersampling was used to avoid biases. In random undersampling, observations from the majority class are randomly removed until a balanced class distribution is achieved.

Statistics

GraphPad Prism or R software were used to perform the different statistical tests. The tests used in each analysis are specified in the corresponding figure. P-values are represented as: * P-value ≤ 0.05, ** P-value ≤ 0.01, *** P-value ≤ 0.001 and **** P-value ≤ 0.0001.

Visualizations

Visualizations were performed with GraphPad prism or custom R scripts using the packages ggplot268. Contact maps were visualized using the circlize R package69. ChimeraX was used to visualize protein structures70.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The Native Fold Delay datasets for the yeast and E. coli proteomes generated for this study have been deposited at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14712087. The raw and processed in vitro Ssb binding analysis data generated in this study are provided in the Source Data file. Additional datasets used in this study are also publicly available: ref. 34 (protein folding rates), ref. 39 (protein domains), refs. 31,32 (Ssb binding footprints), ref. 30 (protein aggregation in Ssb knockout strain), ref. 49 (protein aggregation during arsenite stress) and ref. 51 (protein co-translational ubiquitination during physiological conditions). Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

Code for calculating the Native Fold Delay profile of individual proteins can be publicly found at https://github.com/ramondur/Native-Fold-Delay or on Zendo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14712087. All customized R scripts used for data processing and analysis are available from the corresponding author on request.

References

Anfinsen, C. B. Principles that govern the folding of protein chains. Science 181, 223–230 (1973).

To, P., Whitehead, B., Tarbox, H. E. & Fried, S. D. Nonrefoldability is pervasive across the E. coli proteome. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 11435–11448 (2021).

Plaxco, K. W., Simons, K. T. & Baker, D. Contact order, transition state placement and the refolding rates of single domain proteins11Edited by P. E. Wright. J. Mol. Biol. 277, 985–994 (1998).

To, P. et al. A proteome-wide map of chaperone-assisted protein refolding in a cytosol-like milieu. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 119, e2210536119 (2022).

Ingolia, N. T., Lareau, L. F. & Weissman, J. S. Ribosome profiling of mouse embryonic stem cells reveals the complexity and dynamics of mammalian proteomes. Cell 147, 789–802 (2011).

Liang, S. T., Xu, Y. C., Dennis, P. & Bremer, H. mRNA composition and control of bacterial gene expression. J. Bacteriol. 182, 3037–3044 (2000).

Chaney, J. L. & Clark, P. L. Roles for synonymous codon usage in protein biogenesis. Annu Rev. Biophys. 44, 143–166 (2015).

Wagaman, A. S., Coburn, A., Brand-Thomas, I., Dash, B. & Jaswal, S. S. A comprehensive database of verified experimental data on protein folding kinetics. Protein Sci. 23, 1808–1812 (2014).

Ciryam, P., Morimoto, R. I., Vendruscolo, M., Dobson, C. M. & O’Brien, E. P. In vivo translation rates can substantially delay the cotranslational folding of the Escherichia coli cytosolic proteome. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, E132–E140 (2013).

Liutkute, M., Samatova, E. & Rodnina, M. V. Cotranslational folding of proteins on the ribosome. Biomolecules 10, 97 (2020).

Waudby, C. A., Dobson, C. M. & Christodoulou, J. Nature and regulation of protein folding on the ribosome. Trends Biochem. Sci. 44, 914–926 (2019).

Jiang, Y. et al. How synonymous mutations alter enzyme structure and function over long timescales. Nat. Chem. 15, 308–318 (2023).

Moss, M. J., Chamness, L. M. & Clark, P. L. The effects of codon usage on protein structure and folding. Ann. Rev. Biophys. 53, 87–108 (2023).

Frydman, J., Erdjument-Bromage, H., Tempst, P. & Hartl, F. U. Nat. Struct. Biol. 6, 697–705 (1999).

Samelson, A. J. et al. Kinetic and structural comparison of a protein’s cotranslational folding and refolding pathways. Sci. Adv. 4, eaas9098 (2018).

Zhang, G., Hubalewska, M. & Ignatova, Z. Transient ribosomal attenuation coordinates protein synthesis and co-translational folding. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 16, 274–280 (2009).

Ugrinov, K. G. & Clark, P. L. Cotranslational folding increases GFP folding yield. Biophys. J. 98, 1312–1320 (2010).

Evans, M. S., Sander, I. M. & Clark, P. L. Cotranslational folding promotes beta-helix formation and avoids aggregation in vivo. J. Mol. Biol. 383, 683–692 (2008).

Clark, P. L. Protein folding in the cell: reshaping the folding funnel. Trends Biochem. Sci. 29, 527–534 (2004).

Huang, C. et al. Intrinsically aggregation-prone proteins form amyloid-like aggregates and contribute to tissue aging in Caenorhabditis elegans. Elife 8, https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.43059 (2019).

Zhu, M. et al. Pulse labeling reveals the tail end of protein folding by proteome profiling. Cell Rep. 40, 111096 (2022).

Xu, G. et al. Vulnerability of newly synthesized proteins to proteostasis stress. J. cell Sci. 129, 1892–1901 (2016).

Nedialkova, D. D. & Leidel, S. A. Optimization of codon translation rates via tRNA modifications maintains proteome integrity. Cell 161, 1606–1618 (2015).

Bitran, A., Jacobs, W. M. & Shakhnovich, E. The critical role of co-translational folding: An evolutionary and biophysical perspective. Curr. Opin. Syst. Biol. 37, 100485 (2024).

Cassaignau, A. M. E. et al. Interactions between nascent proteins and the ribosome surface inhibit co-translational folding. Nat. Chem. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41557-021-00796-x (2021).

Deckert, A. et al. Common sequence motifs of nascent chains engage the ribosome surface and trigger factor. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2103015118 (2021).

Streit, J. O. et al. The ribosome lowers the entropic penalty of protein folding. Nature 1–8 (2024).

Deuerling, E., Gamerdinger, M. & Kreft, S. G. Chaperone Interactions at the Ribosome. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 11. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a033977 (2019).

Ferbitz, L. et al. Trigger factor in complex with the ribosome forms a molecular cradle for nascent proteins. Nature 431, 590–596 (2004).

Willmund, F. et al. The cotranslational function of ribosome-associated Hsp70 in eukaryotic protein homeostasis. Cell 152, 196–209 (2013).

Doring, K. et al. Profiling Ssb-nascent chain interactions reveals principles of hsp70-assisted folding. Cell 170, 298–311 e220 (2017).

Stein, K. C., Kriel, A. & Frydman, J. Nascent polypeptide domain topology and elongation rate direct the cotranslational hierarchy of Hsp70 and TRiC/CCT. Mol. Cell 75, 1117–1130 e1115 (2019).

Schubert, U. et al. Rapid degradation of a large fraction of newly synthesized proteins by proteasomes. Nature 404, 770–774 (2000).

Manavalan, B., Kuwajima, K. & Lee, J. PFDB: A standardized protein folding database with temperature correction. Sci. Rep. 9, 1588 (2019).

Xu, Y., Purkayastha, P. & Gai, F. Nanosecond folding dynamics of a three-stranded β-sheet. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 15836–15842 (2006).

Plaxco, K. W., Simons, K. T. & Baker, D. Contact order, transition state placement and the refolding rates of single domain proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 277, 985–994 (1998).

Kurt, N. & Cavagnero, S. The burial of solvent-accessible surface area is a predictor of polypeptide folding and misfolding as a function of chain elongation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 15690–15691 (2005).

Fox, N. K., Brenner, S. E. & Chandonia, J.-M. SCOPe: structural classification of Proteins—extended, integrating SCOP and ASTRAL data and classification of new structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, D304–D309 (2014).

Chandonia, J.-M. et al. SCOPe: improvements to the structural classification of proteins – extended database to facilitate variant interpretation and machine learning. Nucleic Acids Res. 50, D553–D559 (2022).

Jumper, J. et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 596, 583–589 (2021).

Varadi, M. et al. AlphaFold Protein Structure Database: massively expanding the structural coverage of protein-sequence space with high-accuracy models. Nucleic Acids Res. 50, D439–D444 (2022).

Sekhar, A. et al. Conserved conformational selection mechanism of Hsp70 chaperone-substrate interactions. Elife 7, e32764 (2018).

Rosenzweig, R., Nillegoda, N. B., Mayer, M. P. & Bukau, B. The Hsp70 chaperone network. Nat. Rev. Mol. cell Biol. 20, 665–680 (2019).

Preissler, S. & Deuerling, E. Ribosome-associated chaperones as key players in proteostasis. Trends Biochem. Sci. 37, 274–283 (2012).

Zhang, Y. et al. The ribosome-associated complex RAC serves in a relay that directs nascent chains to Ssb. Nat. Commun. 11, 1504 (2020).

Rüdiger, S., Germeroth, L., Schneider-Mergener, J. & Bukau, B. Substrate specificity of the DnaK chaperone determined by screening cellulose-bound peptide libraries. EMBO J. 16, 1501–1507 (1997).

Van Durme, J. et al. Accurate prediction of DnaK-peptide binding via homology modelling and experimental data. PLoS Comput Biol. 5, e1000475 (2009).

Jacobson, T. et al. Arsenite interferes with protein folding and triggers formation of protein aggregates in yeast. J. cell Sci. 125, 5073–5083 (2012).

Ibstedt, S., Sideri, T. C., Grant, C. M. & Tamas, M. J. Global analysis of protein aggregation in yeast during physiological conditions and arsenite stress. Biol. Open 3, 913–923 (2014).

Klaips, C. L., Jayaraj, G. G. & Hartl, F. U. Pathways of cellular proteostasis in aging and disease. J. Cell Biol. 217, 51–63 (2018).

Duttler, S., Pechmann, S. & Frydman, J. Principles of cotranslational ubiquitination and quality control at the ribosome. Mol. Cell 50, 379–393 (2013).

Sharma, A. K. et al. A chemical kinetic basis for measuring translation initiation and elongation rates from ribosome profiling data. PLoS computational Biol. 15, e1007070 (2019).

Shamir, M., Bar-On, Y., Phillips, R. & Milo, R. SnapShot: timescales in cell biology. Cell 164, 1302–1302. e1301 (2016).

Kim, D. E., Chivian, D. & Baker, D. Protein structure prediction and analysis using the Robetta server. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, W526–W531 (2004).

Hanazono, Y., Takeda, K. & Miki, K. Structural studies of the N-terminal fragments of the WW domain: Insights into co-translational folding of a beta-sheet protein. Sci. Rep.-Uk 6, 34654 (2016).

Agirrezabala, X. et al. A switch from α‐helical to β‐strand conformation during co‐translational protein folding. EMBO J. 41, e109175 (2022).

Wu, C. C.-C., Zinshteyn, B., Wehner, K. A. & Green, R. High-resolution ribosome profiling defines discrete ribosome elongation states and translational regulation during cellular stress. Mol. cell 73, 959–970. e955 (2019).

Netzer, W. J. & Hartl, F. U. Recombination of protein domains facilitated by co-translational folding in eukaryotes. Nature 388, 343–349 (1997).

Siller, E., DeZwaan, D. C., Anderson, J. F., Freeman, B. C. & Barral, J. M. Slowing bacterial translation speed enhances eukaryotic protein folding efficiency. J. Mol. Biol. 396, 1310–1318 (2010).

Morales-Polanco, F., Lee, J. H., Barbosa, N. M. & Frydman, J. Cotranslational mechanisms of protein biogenesis and complex assembly in eukaryotes. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Data Sci. 5, 67–94 (2022).

Berman, H. M. et al. The protein data bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 235–242 (2000).

Schymkowitz, J. et al. The FoldX web server: an online force field. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, W382–W388 (2005).

Kabsch, W. & Sander, C. Dictionary of protein secondary structure: pattern recognition of hydrogen-bonded and geometrical features. Biopolymers 22, 2577–2637 (1983).

Joosten, R. P. et al. A series of PDB related databases for everyday needs. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, D411–D419 (2011).

Tien, M. Z., Meyer, A. G., Sydykova, D. K., Spielman, S. J. & Wilke, C. O. Maximum allowed solvent accessibilites of residues in proteins. PloS one 8, e80635 (2013).

Ruff, K. M. & Pappu, R. V. AlphaFold and implications for intrinsically disordered proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 433, 167208 (2021).

Fernandez-Escamilla, A. M., Rousseau, F., Schymkowitz, J. & Serrano, L. Prediction of sequence-dependent and mutational effects on the aggregation of peptides and proteins. Nat. Biotechnol. 22, 1302–1306 (2004).

Wickham, H. Data analysis. In ggplot2 pp. 189-201, Springer. (2016).

Gu, Z., Gu, L., Eils, R., Schlesner, M. & Brors, B. circlize Implements and enhances circular visualization in R. Bioinformatics 30, 2811–2812 (2014).

Goddard, T. D. et al. UCSF chimeraX: meeting modern challenges in visualization and analysis. Protein Sci. 27, 14–25 (2018).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Sabine Rospert (Freiburg) for their feedback and help with the SSB1 purification. The Switch Laboratory was supported by the Flanders Institute for Biotechnology (VIB, grant no. C0401), KU Leuven through postdoctoral grant PDMT2/24/084 to R.D. and the Fund for Scientific Research Flanders (FWO, project grants G053420N and G0A6724N to J.S. and postdoctoral fellowship 12S3722N to B.H.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.R. and J.S. conceived and supervised this study. R.D., B.H., and P.F.M. designed and performed the computational analyses. Y.Z. recombinantly produced and purified Ssb. B.H., R.D., F.R., and J.S. wrote the manuscript. All authors proofread and corrected the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The subject matter of this publication is part of a patent application (EP 24154112.7) with inventors F.R. and J.S. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Ayala Shiber and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions