Abstract

Moiré quasicrystals, formed by stacking periodic structures with a relative twist between them, exhibit many exotic phenomena. Their quasiperiodicity leads to effects such as light localization-delocalization transitions, superconductivity, topological states, and quasiband dispersion. However, weak interlayer interactions, the scalar nature of acoustic fields, and longer wavelengths severely limit the demonstration of these phenomena in acoustics. Here, we report an acoustic moiré quasicrystal that not only achieves a localization-delocalization transition, but also enables wave propagation shifting from diffusion to canalization or localization as a function of the quasicrystal geometry. Unlike conventional two-dimensional materials, the designed sublattice provides tailorable anisotropy and spatial broken symmetry, allowing quasicrystal structures to exhibit reconfigurable nontrivial dispersion. Furthermore, by introducing a uniform tilt angle in the unit cells breaks the spatial symmetry of the moiré quasicrystal, resulting in partial attenuation and disappearance of the wave within the localization pattern. Our findings pave a new avenue for controlling the properties of acoustic wave patterns, and benefit potential applications in energy transfer, subwavelength wave propagation, and highly sensitive sensors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Quasicrystals, characterized by a macrosymmetric structure first observed in metal alloys1,2, feature long-range order in their arrangement of atoms3,4, but do not obey translational symmetry as regular crystals5,6,7,8. They manifest a delicate balance between order and disorder, which results in effects such as light localization-delocalization transitions9,10,11, superconductivity12,13,14,15, topological states16,17, and quasiband dispersion18. In contrast to crystals, which typically exhibit two-, three-, four- or six-fold rotational symmetry, quasicrystals are characterized by a symmetry that is five or even eight times larger19,20, which makes their synthesis and natural discovery difficult. Moiré quasicrystals, formed by the stacking of two-dimensional materials, offer an ideal platform to realize quasicrystals with higher symmetries5,17,21,22,23. They are characterized by flexible control over interlayer coupling, offering abundant possibilities for the exploration of exotic phenomena associated with their quasicrystal nature.

Exploring wave localization and propagation in moiré quasicrystals is not limited to the fields of optics, but it extends across all scientific disciplines that study wave phenomena. Anderson localization theory predicts that waves in a strongly disordered system may exhibit localization, which has been demonstrated in strongly disordered and nonlinear systems24,25,26,27,28. Recently, wavepacket localization of light waves in linear moiré quasicrystals and their evolution from delocalization to localization has also been observed experimentally17,29. This suggests that, although quasicrystals are not disordered, their quasiperiodic structure can induce effects similar to those observed in disordered systems, resulting in localization. Its quasiperiodic character makes the moiré system as a promising platform for exotic wave properties.

Unlike photonic moiré quasicrystals, most acoustic moiré systems need to be implemented at the macroscopic scale. At this scale, interlayer interactions primarily rely on mechanical coupling through air or structural contact, which are significantly weaker compared to the electromagnetic interactions in photonic systems. This relatively weak interlayer interaction diminishes the hybridization of dispersion curves between layers, thereby restricting the realization of phenomena such as localization-delocalization transitions. As a result, studying wave evolution behaviors in acoustic moiré systems becomes more challenging. Moreover, the scalar nature of acoustic fields, their longer wavelength, and the effects of diffraction and attenuation pose additional challenges. Recent studies suggest that, with innovative design, it is possible to achieve tailored coupling and nonlinear responses in these systems, potentially leading to moiré effects30,31,32. And utilizing modular design to tailor the dispersion of acoustic metamaterials to achieve the desired low-frequency sound attenuation properties33. The theoretical feasibility of realizing acoustic moiré quasicrystals has hence become increasingly plausible.

Here we report the demonstration of wave canalization, asymmetric localization and delocalization in acoustic moiré quasicrystals. We utilize the concept of nonlocal moiré superlattices, which extends moiré quasicrystals beyond the fixed control of interlayer coupling strength and twist angle, enabling multidimensional modulation of isotropy, anisotropy, and spatial symmetry. As a result, tunable moiré superlattices with diffusion-canalization-localization transitions can be achieved, distinct from previous reports of wave packet localization25,34,35,36. We theoretically and experimentally demonstrate two kinds of bilayer acoustic systems consisting of two sublattices. In addition, a square unit cell with a tilt angle is specifically designed to break the out-of-plane spatial symmetry, further enabling asymmetric localization. Notably, in acoustics earlier work involved five ultrasonic beams converging onto a pentagonal array to form a \(5\)-fold quasicrystal pressure field distribution in liquids5. This pressure-standing wave field has applications in liquid crystals, polymers, and liquid decomposition. Recent reports indicate that fine-tuning the twist angle to form AB and AA stacking in quasicrystals can generate flat bands in the energy bands, leading to point-like and ring-like localization states23, analogous to the flat bands observed in twisted bilayer graphene. Our work presents a fundamentally different system—a bilayer anisotropic lattice—that enables novel wave-quasicrystal interactions in air. This system allows for higher-dimensional tuning of dispersion, extending acoustic quasicrystals to monoclinic quasicrystals, thereby enabling various wave patterns such as delocalization, localization, canalization, and asymmetric localization. This control offers a flexible mechanism to tailor dispersion and spatial nonuniformity in quasiperiodic structures, enabling the emergence of novel wave propagation patterns.

Results

Acoustic moiré superlattices

We employ 3D printing to fabricate acoustic moiré superlattices consisting of two stacked sublattices that can be twisted relative to each other. The unit cells of these sublattices are either hexagonal or square in structure31 and their interaction is regulated by the twist angle, which determines various periodic or aperiodic structures within the moiré superlattice. For hexagonal (or square) sublattices, the twist angles that produce periodic structures are determined by the Diophantine equation (or Pythagorean triples) (see Supplementary S1). For other twist angles, the resulting structures are aperiodic but remain regular (i.e., non-disordered)17,37. Interestingly, the moiré superlattice can also become a quasicrystal with quasiperiodic yet long-range order, such as the 12-fold rotationally symmetric quasicrystal shown in Fig. 1a.

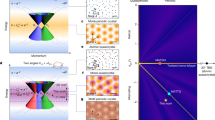

a Acoustic moiré quasicrystal. Top row, bilayer anisotropic metasurfaces composed of hexagonal unit cells with a localized sound pressure field. Bottom row, pattern of a 12-fold rotational symmetric moiré quasicrystal. b, Inverse width of the dispersion modes versus twist angle. The purple (green) curve represents the isotropic (anisotropic) hexagonal lattice. The vertical dashed lines represent the twist angle \(\theta=\arctan {3}^{-1/2}=\pi /6\). c–f Energy dispersion diagram for four types of \({{\rm{\omega }}}\left(k\right)\), which can interconvert into one another in our moiré system through twisting, tilting or tuning anisotropy (illustrated in the upper right corner of each pattern). g–i Theoretical prediction of hybridized dispersion curves. The three different dispersions correspond to the three distinct unit cells in the upper right corner.

The dispersion of the acoustic moiré quasicrystals exhibits multidimensional tunability. By adjusting the acoustic impedance (inductive or capacitive) of the original unit cell, we can easily modify the in-plane anisotropy of the sublattices while preserving the rotational symmetry of the quasicrystal. As shown in the upper right corners of Fig. 1g, h and i, we achieved controllable in-plane isotropy or anisotropy in the sublattices by transforming the coupling structure of the unit cells. In Supplementary S2, the iso-frequency contours of the three sublattices display distinct shapes: two of them have hyperbolic contours, indicating extreme anisotropy, whereas the other exhibits a circular contour, suggesting isotropy or slight anisotropy. We then introduced an inverse width \(\chi\) (see Supplementary S3) to describe the spatial distribution of the wave patterns in the two types of moiré superlattices. As shown in the numerical calculations in Fig. 1b, the inverse width reaches its maximum value at \(\theta=\arctan {3}^{-1/2}=\pi /6\) or \(\theta=\pi /2\) (quasicrystal), suggesting stronger localization of energy compared to other twist angles. In contrast, the inverse width reaches its minimum value at \(\theta=0\) or \(\pi /3\) (where the two layers fully overlap and the moiré superlattice exhibits \({{{\rm{C}}}}_{3}\) symmetry), suggesting weaker localization and a more extended energy distribution relative to other twist angles. This variation underscores significant discrepancies in wave phenomena between different superlattices and suggests the existence of wave localization features in moiré quasicrystals. Additionally, (see Fig. 1i), the out-of-plane spatial symmetry can be broken by tilting each square unit cell. Note that the tilt angle in Fig. 1i is exaggerated for clarity. The specific parameters of each unit cell structure are provided in Supplementary S4.

To understand wave propagation in moiré superlattices, we established a theoretical model to determine their hybridized dispersion modes. Based on the transfer matrix method38, the dispersion relation of the monolayer can be obtained as:

where \({T}_{11}\), \({T}_{12}\), \({T}_{21}\) and \({T}_{22}\) are the four elements of the \(2\times 2\) matrix \({\hat{T}}_{1\to 3}\), not matrices themselves. Note that \({\hat{T}}_{1\to 3}\) is a relationship matrix between the output and input sound waves, constructed through the transfer matrix. \({d}_{h}\) is the height of a monolayer. It should be emphasized that the origin of Formula (1) is based on the transfer matrix method, from which the dispersion relation of a monolayer is derived. The detailed steps can be found in Supplementary S5.

These results confirm that our moiré superlattices may exhibit four distinct dispersion modes: delocalization, localization, canalization and asymmetric localization. As shown in Fig. 1c, where the isotropic bilayers fully overlap (satisfying \({{{\rm{C}}}}_{3}\) and translational symmetry) the distribution mode forms an expanded, irregular pattern. In contrast, at \(\theta=\arctan {3}^{-1/2}=\pi /6\) (quasicrystal), as shown in Fig. 1b and d, the inverse width reaches its maximum value, and the energy distribution becomes localized at its center. This finding indicates that the wave energy or vibrational mode is more tightly confined within the plane. When the sublattice is tuned to support extreme acoustic anisotropy, it forms a quasicrystal structure at \(\theta=\pi /6\), where canalization occurs, as shown in Fig. 1e and h, with waves propagating in a highly concentrated manner. Notably, at \(\theta=\pi /2\) (quasicrystal), for geometric reasons, the hyperbolas of the two layers hybridize to form an ellipse, transforming the moiré superlattice from anisotropic to isotropic or weakly anisotropic39. In this regime, the anisotropy vanishes and the superlattice is influenced primarily by quasi-periodicity, again resulting in localization shown in Fig. 1b. Specifically, in bilayer anisotropic moiré systems, interlayer coupling causes the hyperbolic dispersion curves of the upper and lower layers to gradually hybridize as the twist angle increases. At the quasicrystal state (\(\theta=\pi /6\)), this hybridization leads to the formation of flat bands, enabling the canalization effect of the quasicrystal. With a further increase in the twist angle, at the quasicrystal state (\(\theta=\pi /2\)), the hybridized dispersion curves form closed loops, and the system exhibits isotropic characteristics. At this stage, the quasicrystal’s unique long-range order, combined with the absence of local periodicity, plays a key role, ultimately leading to wave localization. This principle also applies to isotropic moiré systems. Additionally, by tilting each unit cell’s \(z\)-axis resonators by \(5^\circ\) towards the transverse plane, the distribution mode becomes half-propagating and half-attenuated (asymmetric localization, see Fig. 1f and i). This is because such tilting induces a spatial deflection of the dispersion, causing part of the wave to remain confined within the plane while another portion dissipates into space, thereby leading to asymmetric localization effects. The plane projections of the dispersion at \(\theta=\pi /6\) in Fig. 1g–i also reveal the three types of moiré quasicrystal phenomena.

Extremely anisotropic moiré quasicrystal

To validate the aforementioned concepts, we conducted numerical simulations and experiments on the anisotropic moiré superlattice. As shown in Fig. 2a, the monolayer metasurface is composed of hexagonal unit cells, and stacking two layers forms a moiré system. The green coupling tube structure differs significantly in design from other coupling tubes, resulting in the acoustic impedance being either inductive or capacitive in different in-plane directions40, making the sublattice extremely anisotropic. The excitation point source is placed near the center above the bilayer metasurface. The detailed settings and procedures for the numerical simulations and experiments can be found in the Methods section.

a Top view of a moiré quasicrystal composed of anisotropic hexagonal unit cells. The yellow pentagram represents the location of the point source excitation (\(f=1850{{\rm{Hz}}}\)). b Energy distribution in the cross-section of the quasicrystal. When canalization occurs (\(\theta=\arctan {3}^{-1/2}=\pi /6\)), the purple curve illustrates the energy distribution during propagation. In contrast, when localization takes place (\(\theta=\pi /2\)), the green curve shows the energy distribution along the \(x\)-axis at \(y=0\). c–f Illustration of the anisotropic moiré superlattice, along with the simulation and experimental results. The first row shows the patterns of the moiré superlattice (the green arrows indicate that the lattice satisfies translational or rotational symmetry), the second and third rows present the simulated sound pressure fields, and the bottom row displays the experimental sound pressure fields (5 mm below the bilayer).

In Fig. 2b, the green curve represents the energy generated in the cross-section of the quasicrystal by the sound wave when \(\theta=\pi /6\), whereas the purple curve represents the energy distribution for \(\theta=\pi /2\). The results indicate that the quasicrystal energy distributions for two twist angles differ: one is localized, the other is canalized. This is because when the relative rotation angle between the upper and lower layers, i.e., the twist angle, reaches \(\pi /6\), the dispersion curves of the two layers hybridize into flat bands, enabling canalized propagation of acoustic waves39. Additionally, when the two anisotropic sublattices are rotated relative to each other beyond a certain angle, the hybridized dispersion curves close, causing the anisotropy to disappear and the effects of quasiperiodicity to emerge, thereby transforming canalization to localization. Importantly, for \(\theta=\pi /6\), canalization causes a shift in the direction of propagation, necessitating an adjustment in the position of the cross-section. Moreover, when the twist angle \(\theta=0\), each layer of the bilayer system exhibits anisotropic hyperbolic dispersion without any hybridization, resulting in hyperbolic wave propagation (Fig. 2c). As the twist angle increases, at \(\theta=\pi /3\), the dispersion curves of the upper and lower layers hybridize, causing the overall dispersion of the system to form closed loops, thereby exhibiting isotropic characteristics. However, at this stage, the system is not a quasicrystal and thus cannot rely on quasicrystal properties to achieve wave localization. Consequently, the waves exhibit omnidirectional diffusion (Fig. 2e). Figure 2c–f illustrate the changes in moiré superlattice structure with twisting, along with the corresponding numerical and experimental results. The simulation and experimental outcomes are consistent, both validating the previous predictions. The upper row of the moiré superlattice shows the translational symmetry of the periodic structures and the rotational symmetry of the quasiperiodic structures at four different twist angles. While the transition from hyperbolic to elliptical dispersion has been previously reported39,41, wave propagation from canalization to localization in quasicrystals has not yet been demonstrated. Our findings are enabled with the quasiperiodic tunability of our geometry.

It is worth mentioning that the formation of the canalization effect is based on the hybridization of the dispersion curves of the upper and lower layers in a bilayer system at a specific twist angle, a principle that determines its inherent robustness. Additionally, the dispersion curve of the monolayer system is hyperbolic, which results from the unit cell being designed with extreme anisotropy, providing the foundation for achieving canalization. Since the canalization effect originates from the hybridization of the bilayer dispersion curves, this hybridization primarily depends on the shape of the monolayer dispersion curve and their interaction, which are determined by the structural design and are largely independent of the number of layers. Of course, increasing the number of layers may enhance wave confinement, but it has limited influence on the formation mechanism of canalization, thus demonstrating robustness against variations in the number of layers. The physical mechanism of the canalization effect is fundamentally independent of the source intensity. The extreme anisotropy of the unit cell ensures that the hybridized canalization effect remains stable even with variations in the source intensity, affecting only the amplitude of the sound pressure field without altering the propagation pattern. Results from other twist angles have been included in Supplementary S7, along with detailed explanations of the physical meanings of delocalization, canalization, and diffusion. The 2D experimental plots, Fourier spectra and actual images can be found in Supplementary S8.

Isotropic moiré quasicrystals

In the isotropic moiré superlattice, the coupling structures in all directions of the hexagonal unit cell are uniform. As shown in Fig. 3a, the unit cells are closely packed together with a small lattice constant, and the excitation point source is positioned near the center above the bilayer. We conducted numerical simulations and experiments on moiré superlattices with four different twist angles. Figure 3c–f show that even with the same twist angle and the same periodic or quasiperiodic moiré structure, the wave evolution differs significantly from the one observed in the anisotropic moiré superlattice. This is because the set of dispersion curves (Supplementary Fig. S1a) is not influenced by extreme anisotropy and consistently maintains a closed circular shape, with sound waves being affected only by the moiré structure of the superlattice.

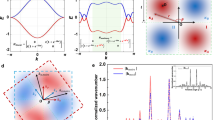

a Top view of the moiré quasicrystal composed of isotropic hexagonal unit cells. The yellow pentagram represents the location of the point source excitation (\(f=1850{{\rm{Hz}}}\)). b Localized energy distribution in the cross-section of the quasicrystal at different frequencies. The curves show the energy distribution along the \(x\)-axis at \(y=0\). c–f Illustration of the isotropic moiré superlattice, along with the simulation and experimental results. The first row shows the patterns of the moiré superlattice (the yellow arrows indicate that the lattice satisfies translational or rotational symmetry), the second row presents the simulated sound pressure fields, and the bottom row displays the experimental sound pressure fields (5 mm below the bilayer).

Specifically, when \(\theta=0^\circ\) or \(60^\circ\), the structure exhibits translational symmetry and \({{{\rm{C}}}}_{3}\) symmetry, allowing sound waves to omnidirectionally propagate within the ordered structure, resulting in a diffuse sound pressure field, as shown in Fig. 3c and e. With translational symmetry, the physical properties of the structure are periodic in space, meaning that the medium conditions encountered by the acoustic waves remain identical at different positions. This symmetry prevents additional reflections or scattering, enabling the acoustic waves to propagate omnidirectionally within the structure. Furthermore, translational symmetry ensures momentum conservation for the wave (The wave will not produce additional reflections or energy loss due to discontinuities or irregularities in the medium), allowing it to propagate freely without being scattered by the periodic medium. At the same time, C3 symmetry minimizes spatial inhomogeneity. Due to the equivalence of the three angular directions in C3 symmetry, multiple scattering of acoustic waves in these directions results in equivalent coherent interference. Such interference does not cause significant spatial inhomogeneity, leading to a uniformly diffused pressure field rather than wave localization or energy concentration. When \(\theta=30^\circ\) or \(90^\circ\), the moiré structure forms a quasicrystal with long-range order but no local periodicity, based on which the sound waves form a highly concentrated pattern, in contrast to the previous scenario (see Figs. 3d and f). Unlike periodic crystals, quasicrystals do not exhibit strict periodic repetition locally. This disrupts the consistency of distances and phase relationships between scattering centers encountered by the waves during propagation. Such aperiodicity significantly enhances multiple scattering effects. As acoustic waves propagate within the structure, the complexity of phase relationships along different paths can lead to constructive interference in certain regions, resulting in energy accumulation and highly localized wave patterns. Their long-range order implies that the global symmetry of the structure cannot be generated through simple translations. And the long-range order provides a global structural constraint, leading to predictable localized wave patterns in specific regions. This unique combination of aperiodicity and long-range order governs wave propagation, leading to localized wave patterns. In comparison, periodic structures with translational symmetry exhibit regular unit cells, enabling predictable scattering paths and uniform energy diffusion throughout the structure. In summary, by tuning the twist angle, we can achieve a transition from delocalized to localized wave behavior in a single system. This tunability highlights the unique advantages and potential applications of quasicrystal structures in acoustics.

Additionally, we explored the impact of different frequencies on localization. The iso-frequency contour within the range of \(1550{{\rm{Hz}}}\) to \(1850{{\rm{Hz}}}\) is a closed circle (as shown in Supplementary Fig. S1a), indicating that localization is not affected by factors such as dispersion geometry and anisotropy. Therefore, at these frequencies, the waves should exhibit localization characteristics under the influence of the quasicrystal structure. As shown in Fig. 3b, the curves represent the cross-sectional modes of the acoustic energy in the quasicrystal, corresponding to different frequencies ranging from \(1550{{\rm{Hz}}}\) to \(1850{{\rm{Hz}}}\) in \(150{{\rm{Hz}}}\) increments. The results of the calculation in Fig. 3b, along with the experimental data in Supplementary S9, indicate that each frequency has a peak indicative of localization, confirming the previous numerical simulations of iso-frequency contours. Notably, as the frequency decreases, the peak gradually diminishes, which may be related to the reduction in local energy and increase in wavelength. Specifically, the reduction in energy at lower frequencies can be attributed to the characteristics of the sound source and the physical properties of the system. At lower frequencies, acoustic energy is distributed over longer wavelengths, leading to a decrease in the local energy density within the localized region. This contrasts with higher frequencies, where shorter wavelengths can more effectively concentrate energy in the localized region. Furthermore, the increase in wavelength may also lead to changes in the attenuation characteristics of the wave, further affecting the strength of localization.

Monoclinic moiré quasicrystals

The superlattice composed of square sublattices also forms an aperiodic lattice9 when \(\theta=\arctan {3}^{-1/2}=\pi /6\). This geometry enables extreme anisotropy while also allowing for the adjustment of spatial symmetry by tilting each unit cell. As shown in Fig. 4a, the conventional bilayer system exhibits an orthogonal square lattice (indicated by red dashed lines), with a right-angle between the lattice axes. When each unit cell is tilted by angle of \(5^\circ\), as illustrated in Fig. 4b, the angle between the axes changes to \(85^\circ\). This results in out-of-plane spatial symmetry breaking, transforming the square lattice into a monoclinic lattice. This can be observed in the theoretical dispersion in Fig. 1i, where only half of the elliptical dispersion remains in plane; this is analogous to ‘ghost modes’ observed in bulk crystals42, where the introduction of a tilt with respect to the interface changes the dispersion and the modes transition to a hybrid between surface and bulk modes. A portion of the energy propagates away from the surface, while the rest continues to propagate along the surface43. As illustrated in Fig. 4c and d, this pattern leads to partial attenuation of the wave in localized states, resulting in asymmetric localization at \(f=2050{{\rm{Hz}}}\).

a, b Square bilayer moiré quasicrystal (\(\theta=\arctan {3}^{-1/2}=\pi /6\)) in both non-tilted and tilted configurations. c, d, Sound pressure fields before and after a \(5^\circ\) tilt. The unit cell structure is shown in the upper right corner. e Asymmetric energy distribution in the cross-section of the quasicrystal. The green curve shows the energy distribution along the \(x\)-axis at \(y=0\).

Similarly, we also studied the cross-sectional energy of sound waves in the monoclinic moiré quasicrystal, as shown in Fig. 4e. The energy is concentrated on one side, which is significantly different from previous wave propagation patterns. We separately analyzed the sound field intensity in the central region of square lattices for both with and without tilting. Analysis was also performed in hexagonal lattices for both anisotropic and isotropic cases as a function of the twist angle. Details are available in Supplementary S10. Moreover, based on previous study30,32, when the distance between two hyperbolic metasurfaces d (the spacing between the two layers) a. Furthermore, when the interlayer distance is small, the theoretically calculated dispersion exhibits minimal changes and aligns well with the experimental Fourier spectrum. In contrast, if the interlayer distance d ≫ a, the hybridization of the upper- and lower-layer dispersions disappears, and corresponding wave phenomena are no longer observed. Therefore, to ensure strong interlayer coupling, the interlayer spacing in this work is set to 2 mm, which is significantly smaller than the lattice constant. It is important to note that our designed structure can only cause the central vertical resonator to tilt in the \(x\)-direction. However, this does not affect the core concept we aim to convey—asymmetric localization. We can also achieve tilting in the \(y\)-direction by rotating the entire system.

Discussion

In summary, we theoretically and experimentally studied dispersive acoustic quasicrystals controlled by the twist angle between periodic surfaces, enabling extreme tunability, e.g., mode localization-delocalization, diffusion-canalization-localization, and asymmetric localization. We designed three different moiré systems, which enable high-dimensional modulation of isotropy, anisotropy and spatial symmetry. In the isotropic system, we observed the transition from delocalization to localization. By constructing anisotropic unit cells, we achieved wave propagation with tunable diffusion, canalization and localization. Additionally, we further broke the spatial symmetry of the system to achieve asymmetric localization in monoclinic geometries. These findings provide a powerful tool to control sound propagation leveraging quasicrystal dispersion, offering significant potential for applications in controlling uniform wave energy distribution, efficient signal transmission, and energy harvesting as well as noise filtering. Notably, the similarity between our structure and periodically arranged structures widely used in nanophotonic metamaterials and photonic crystals44,45 implies the potential to extend our proposed concepts to applications in other wave regimes.

Methods

Numerical simulations

For the numerical simulations, the COMSOL Multiphysics pressure acoustics module was employed. Both frequency domain and the eigenfrequency modules were utilized. The governing equation is:

Where \({p}_{t}=p+{p}_{b}\) represents the total pressure, including the acoustic pressure \(p\) and background pressure \({p}_{b}\); \({\rho }_{c}=\rho\) is the medium density; \({c}_{c}=c\) is the speed of sound; \({k}_{{eq}}^{2}={\omega }^{2}/{c}_{c}^{2}\) is the equivalent wave number squared; \({{{\boldsymbol{q}}}}_{d}\) denotes dissipation-related terms; and \({Q}_{m}\) represents the acoustic source term. The boundaries of the cavity are modeled as rigid walls, with zero normal acoustic velocity. Bloch boundary conditions were applied to the sides of the unit cell, while the top and bottom surfaces were designated perfectly matched layers (PMLs). The crystal cell’s band structure was computed using the eigenfrequency module via a frequency sweep, as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. S1. To mitigate reflections, eight PMLs were positioned around the bilayer moiré system. We have provided a representative COMSOL original file of this work on the website (see Supplementary S11).

It is worth noting that under high-frequency conditions, (e.g., >10 kHz), the number of PML layers typically needs to be increased to avoid reflection interference. This is because the shorter wavelength of high-frequency waves results in a shorter propagation path within the PML region. If the thickness or number of PML layers is insufficient, waves passing through the PML may not be fully absorbed, leading to reflections at the boundaries that could interfere with the results. Therefore, under high-frequency conditions, increasing the PML thickness, refining the mesh distribution, or adding more PML layers can extend the wave propagation path within the PML. This enables greater absorption of wave energy and effectively minimizes reflections that could compromise computational accuracy. Moreover, the refinement of the mesh can also impact the stability and accuracy of the calculations. For high-frequency conditions, a finer mesh is often required to capture the intricate details of wave propagation. In this work, the highest frequency of the acoustic source is \(2050{{\rm{Hz}}}\), and the \(8\)-layer PML was found to be sufficient to effectively reduce spurious reflections without significantly affecting the main conclusions. A monopole point sound source was placed above the center of the upper layer. Its intensity is defined by the formula \(S={e}^{i{{\varnothing }}}\sqrt{\frac{{\rho }_{c}{c}_{c}{p}_{{rms}}}{2\pi }}\), where \({p}_{{rms}}\) is the root mean square power of the source (set to 1 W), and \({{\varnothing }}\) is the phase of the source (set to 0 rad). The frequency domain module recorded the pressure field \(5{{\rm{mm}}}\) below the metasurface bilayer. Based on the theoretical dispersion model, a series of diagrams were plotted via MATLAB.

Sample preparation and measurements

The moiré quasicrystal system was fabricated via 3D printing (R4600 resin), with each layer comprising a \(15\times 15\) array of unit cells. A speaker with a \(6.0{{\rm{mm}}}\) radius (13A05-8Ω) was centrally located within the system, serving as an omnidirectional point source. Acoustic foam was applied to surround and lay under the system to minimize reflections. Above the setup, an acoustic microphone was attached to a thin mechanical rod operated by a motor to capture the transmitted sound pressure, allowing for data collection at different densities. The grid points were sampled at intervals of \(8{{\rm{mm}}}\). Another reference microphone was positioned approximately \(30{{\rm{cm}}}\) below the point sound source to record the incident sound pressure. To ensure uniformity in the sound pressure measurements over time, the reference microphone simultaneously recorded the speaker’s input signal. The experimental apparatus comprised a computer, a power amplifier (E2021), two microphones (AWA 14604), a chassis (NI PXIe-1082), a motor (9030), a signal generator (DG1022U), a custom-built three-axis motion platform, and a microphone support rod (see Supplementary S6).

Data availability

All relevant data are available in the main text and Supporting Information, and can be obtained from the authors upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Dubost, B., Lang, J.-M., Tanaka, M., Sainfort, P. & Audier, M. Large AlCuLi single quasicrystals with triacontahedral solidification morphology. Nature 342, 48–50 (1986).

Kevin, K. Twenty years of structure research on quasicrystals. Part I. Pentagonal, octagonal, decagonal and dodecagonal quasicrystals. Z. Krist-Cryst. Mater. 219, 391–446 (2004).

Bhaduri, S. B. & Sekhar, J. A. Mechanical properties of large quasicrystals in the Al-Cu-Li system. Nature 327, 609–610 (1987).

Yang, Z. et al. Precipitation of binary quasicrystals along dislocations. Nat. Commun. 9, 809 (2018).

Espinosa, F., Torres, M., Pastor, G., Muriel, M. & Mackay, A. Acoustic Quasi-Crystals. Eur. Lett. 21, 9 (1993).

Zeng, X. et al. A columnar liquid quasicrystal with a honeycomb structure that consists of triangular, square and trapezoidal cells. Nat. Chem. 15, 625–632 (2023).

Ledermann, A. et al. Three-dimensional silicon inverse photonic quasicrystals for infrared wavelengths. Nat. Mater. 5, 942–945 (2006).

Talapin, D. et al. Quasicrystalline order in self-assembled binary nanoparticle superlattices. Nature 461, 964–967 (2009).

Wang, P. et al. Localization and delocalization of light in photonic moiré lattices. Nature 577, 42–46 (2020).

Vaidya, S., Jörg, C., Linn, K., Goh, M. & Rechtsman, M. Reentrant delocalization transition in one-dimensional photonic quasicrystals. Phys. Rev. Res. 5, 33170 (2023).

Huang, C. et al. Localization delocalization wavepacket transition in Pythagorean aperiodic potentials. Sci. Rep. 6, 32546 (2016).

Kamiya, K., Takeuchi, T. & Sato, N. K. Discovery of superconductivity in quasicrystal. Nat. Commun. 9, 154 (2018).

Nagai, Y., Nakamura, H., Machida, M. & Sakuma, A. Superconductivity on a quasiperiodic lattice: extended-to-localized crossover of Cooper pairs. Phys. Rev. B 85, 092505 (2012).

Tokumoto, Y. et al. Superconductivity in a van der Waals layered quasicrystal. Nat. Commun. 15, 1529 (2024).

Uri, A., Barrera, S. & Jarillo-Herrero, P. Superconductivity and strong interactions in a tunable moiré quasicrystal. Nature 121, 620 (2023).

Huang, H. & Liu, F. Quantum spin Hall effect and spin Bott index in a quasicrystal lattice. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 126401 (2018).

Kraus, Y. E., Ringel, Z. & Zilberberg, O. Four-dimensional quantum Hall effect in a two-dimensional quasicrystal. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 226401 (2013).

Crosse, J. A. & Moon, P. Quasicrystalline electronic states in twisted bilayers and the effects of interlayer and sublattice symmetries. Phys. Rev. B. 103, 045408 (2021).

Steurer, W. Quasicrystals: What do we know? What do we want to know? What can we know? Acta. Crystallogr. A. 74, 1–11 (2018).

Zoorob, M. E., Charlton, M. D. B., Parker, G. J., Baumberg, J. J. & Netti, M. C. Quasicrystals: Complete photonic bandgaps in 12-fold symmetric quasicrystals. Nature 404, 740–743 (2000).

Mahmood, R., Ramirez, A., & Hillier, A. Creating two-dimensional quasicrystal, supercell, and moiré lattices with laser interference lithography: implications for photonic bandgap materials. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 4, 8851–8862 (2021).

Singh, A., Dickinson, C. & Ryan, K. Insight into the 3D architecture and quasicrystal symmetry of multilayer nanorod assemblies from moiré interference patterns. ACS Nano 6, 3339–3345 (2012).

Jiang, Z., Liu, J. & Xia, B. Phononic twisted moiré lattice with quasicrystalline patterns. Appl. Phys. Lett. 121, 142202 (2022).

Yamilov, A., Cao, H., Zhao, X., Genack, A. Z. & Garcia, N. Anderson localization of electromagnetic waves in three dimensions. Nat. Phys. 19, 1308–1313 (2023).

Segev, M., Silberberg, Y., Christodoulides, N. & Anderson, D. localization of light. Nat. Photonics 7, 197–204 (2013).

Pikovsky, A. & Shepelyansky, D. Destruction of Anderson Localization by a Weak Nonlinearity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 94101 (2008).

Schwartz, T., Bartal, G. & Segev, M. Transport and Anderson localization in disordered two-dimensional photonic lattices. Nature 446, 52–55 (2007).

Kibler, B., Fatome, J. & Dudley, J. M. The Peregrine soliton in nonlinear fibre optics. Nat. Phys. 6, 790–795 (2010).

Wang, P., Fu, Q., Konotop, V. V., Kartashov, Y. V. & Ye, F. Observation of localization of light in linear photonic quasicrystals with diverse rotational symmetries. Nat. Photonics 18, 224–229 (2024).

Yves, S., Peng, Y. & Alù, A. Topological Lifshitz transition in twisted hyperbolic acoustic metasurfaces. Appl. Phys. Lett. 121, 122201 (2022).

Yves, S. et al. Hyperbolic shear metasurfaces. Phys. Rev. X 14, 021031 (2024).

Han, C. L. et al. Nonlocal acoustic moiré hyperbolic metasurfaces. Adv. Mater. 14, 2311350 (2024).

Dong, H. et al. Achromatic metasurfaces by dispersion customization for ultra-broadband acoustic beam engineering. Natl. Sci. Rev. 9, 12–22 (2022).

Ye, L., Cody, G., Zhou, M., Sheng, P. & Norris, A. N. Observation of bending wave localization and quasi mobility edge in two dimensions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 69, 3080–3083 (1992).

Lahini, Y. et al. Observation of a localization transition in quasiperiodic photonic lattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 013901 (2009).

Huang, C. et al. Localization-delocalization wavepacket transition in Pythagorean aperiodic potentials. Sci. Rep. 6, 32546 (2016).

Stampfli, P. A dodecagonal quasiperiodic lattice in two dimensional. Helv. Phys. Acta. 59, 1260–1263 (1986).

Kotov, O. & Lozovik, Y. Hyperbolic hybrid waves and optical topological transitions in few-layer anisotropic metasurfaces. Phys. Rev. B. 100, 165424 (2019).

Hu, G. et al. Topological polaritons and photonic magic angles in twisted α-MoO3 bilayers. Nature 582, 209–214 (2020).

Quan, L. & Alù, A. Hyperbolic sound propagation over nonlocal acoustic metasurfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 244303 (2019).

Hu, G., Krasnok, A., Mazor, Y., Qiu, C. & Alù, A. Moiré hyperbolic metasurfaces. Nano. Letter. 20, 3217–3224 (2020).

Ma, W. et al. Ghost hyperbolic surface polaritons in bulk anisotropic crystals. Nature 596, 362–366 (2021).

Ni, X. et al. Observation of directional leaky polaritons at anisotropic crystal interfaces. Nat. Commun. 14, 2845–2853 (2023).

Staude, I. & Schilling, J. Metamaterial-inspired silicon nanophotonics. Nat. Photonics 11, 274–284 (2017).

Cheben, P., Halir, R., Schmid, J. H., Atwater, H. A. & Smith, D. R. Subwavelength integrated photonics. Nature 560, 565–572 (2018).

Acknowledgements

T.-Z.Y., and C.-Y.L. acknowledge support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China [Grant No. 12232014], the Natural Science Foundation of China [Grant No. 12072221], the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities [Grant No. 2013017] and the Ten Thousand Talents. C.-L.H. acknowledges the support of China Scholarship Council [Grant No. 202406080122] and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities [Grant No. N2403003]. L.-Q.C. acknowledges support from the Science Center Program of National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 62188101), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 12132002). C.-W.Q. acknowledges financial support from the Ministry of Education, Singapore (Grant No. A-8000107-01-00). A.A. was supported by the Simons Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.-W.Q., T.-Z.Y., A.A., L.-Q.C. conceived the idea. C.-L.H. performed the experiments. C.-L.H., and C.-Y.L. carried out the theoretical analysis and simulations. C.-L.H., G.-Q.X., J.-X. L., H.-Y.F. and T.-Z.Y. wrote the manuscript with contributions from the other authors. All authors have made a substantial contribution to the concept and preparation of the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Vladimir Konotop, Fangwei Ye and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Han, C., Chen, LQ., Yang, T. et al. Observation of dispersive acoustic quasicrystals. Nat Commun 16, 1988 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-57067-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-57067-3

This article is cited by

-

Free vibration symplectic analytical solutions of two-dimensional decagonal quasicrystal cylindrical shell panels

International Journal of Mechanics and Materials in Design (2026)

-

Symmetry-driven artificial phononic media

Nature Reviews Materials (2025)

-

The application prospects of metamaterials in the rolling process

The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology (2025)