Abstract

Interfacial photoelectrochemistry at photoanodes has been extensively researched for solar energy conversion, but its application for the production of high-value-added chemical compounds in organic chemistry still presents challenges. Herein, we report photoelectrocatalytic Cl-mediated C(sp3)–H aminomethylation of alkanes with self-developed and reusable BiVO4 photoanodes. The swift condensation of aniline with aldehydes, along with the decrease of the electricity input of aniline by photogenerated holes in the BiVO4 photoanodes, work together to prevent excessive oxidation of aniline, leading to high yields of the desired product. Mechanistic experiments demonstrate that Cl- ions, as the key mediators, could be attracted to holes in the photoanodes and oxidized to form the Cl2. This is followed by light-promoted homolytic cleavage of Cl2, generating Cl radicals that efficiently abstract hydrogen atoms from hydrocarbons. This work opens an avenue for interfacial photoelectrochemical organic synthesis and demonstrates a potential method for optimizing solar energy conversion into fuels.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

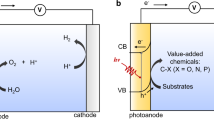

Interfacial photoelectrochemistry (iPEC) at a semiconductor-liquid junction enables a resource-efficient and environmentally benign pathway for directly converting solar energy into chemical fuels, which has been widely explored for H2 production through water decomposition and reduction of carbon dioxide1,2. However, their utility in organic synthesis has only been recognized in recent years and still faces constraints in terms of reaction diversity and underwhelming efficiency3,4. In the last few decades, the swift advancement of photocatalysis and electrocatalysis has emerged as powerful tools, transforming the field of organic synthesis5,6,7,8,9,10,11. In order to circumvent the energy barriers and achieve the organic conversion process in a more sustainable approach, photoelectrochemical catalysis has been introduced to many reported syntheses12,13,14,15,16,17,18. Therein, iPEC, which uses immobilized photoelectrodes to replace dispersed catalysts in heterogeneous systems and soluble catalysts in homogeneous systems, avoids the requirement of a separation process and hence reduces cost. Additionally, certain homogeneous catalysts become inactive after the reaction concludes, rendering them unable to be recovered and reused. Moreover, the external potential of iPEC ensures fast charge separation and high reaction efficiency. Notably, the low and adjustable bias (even the absence of bias) in the iPEC cell saves energy input and avoids excessive oxidation, thereby minimizing the generation of byproducts. Despite these obvious advantages, iPEC for organic synthesis is still in its infancy, for example, the functionalization of C(sp3)–H of hydrocarbons with high bond dissociation energy (85-104 kcal mol–1) in iPEC has even fewer precedents. The Sayama group demonstrated that utilizing a WO3 photoanode under an oxygen atmosphere enables the oxidation of cyclohexane to cyclohexanol and cyclohexanone, attaining both outstanding selectivity for partial oxidation and excellent current utilization efficiency (Fig. 1a)19. After that, utilizing an oxygen-deficient TiO2 photoanode, the Duan group proposed a photoelectrochemical strategy to achieve efficient C–H halogenation of alkanes, producing various organic halides in high conversion (Fig. 1a)20. Although remarkable progress has been made, iPEC continues to encounter many challenges. For instance, (i) most proof-of-concept work has afforded unsatisfactory yields for the target products, (ii) there are limited applications for complex multi-component systems in organic synthesis, (iii) the photoanode materials often detach and deactivate during the reactions21,22. Therefore, the development of a stable photoanode material and application of it in complex multi-component systems to construct high-value-added products is still largely unexplored and remains highly sought after.

a State-of-the-art C–H functionalization of alkanes in interfacial photoelectrochemistry (iPEC). b Challenges of photoelectrocatalytic Cl-mediated multicomponent reactions (MCRs) with amine, aldehyde, and alkane. c This work: Photoelectrocatalytic Cl-mediated C(sp3)–H aminomethylation by BiVO4 photoanodes.

Building on the seminal finding of the Honda-Fujishima effect23, many semiconductor photoanodes have been exploited, such as TiO2, WO3, BiVO4, etc.24,25,26,27,28,29. Among photoanode materials for PEC applications, BiVO4 stands out as a highly promising candidate, gaining considerable interest owing to its robust stability, low toxicity, easy preparation, and visible light responsiveness30,31,32. At present, the utilization of BiVO4 material as photoanodes for organic synthesis is well established33,34,35,36,37. However, most BiVO4 photoanodes are usually prepared by electrodeposition38,39,40. Electrodeposited photoanodes post several drawbacks, such as (i) insufficient active sites, (ii) quick recombination of photoexcited electron-hole pairs, and (iii) exhibiting poor prospects for recycling and reuse41. Therefore, we envisioned that BiVO4 photoanodes prepared through secondary calcination could be used to solve these problems, and further serve in multi-component processes in organic synthesis to demonstrate its practicality.

Over the years, several notable studies have concentrated on the aminomethylation of C(sp3)–H bonds via the 1,2-addition of alkyl radicals to imines. Nevertheless, some drawbacks remain, such as (i) a restricted substrate scope42,43,44, (ii) challenges in applying it to gram-scale reactions45, and (iii) the necessity for imines with activation groups46,47,48. With our continuous interest in sustainable electrochemical alkyl radical transformations49,50,51, herein, we report photoelectrocatalytic Cl-mediated multicomponent reactions (MCRs) of amine, aldehyde, and alkane for the aminomethylation of C(sp3)–H bonds, using our self‐developed and reusable BiVO4-200 photoanode. MCRs usually face the challenges of selectivity control due to a range of potential undesirable side reactions with possibly matched reactivity and selective assembly52,53,54,55,56,57. Notably, the competitive pathways, including reductive hydrogenation of imines (condensation from amine and aldehyde), easy oxidation and reduction of aldehydes, homocoupling of alkyl radicals, carbonyl addition of aldehydes, and oxidation of anilines, all have the potential to impede the formation of the desired target product (Fig. 1b). Fortunately, despite these potential side-products, a series of highly valuable α-branched amines were successfully synthesized with high selectivity from readily available commercial materials in an efficient and straightforward manner. The salient properties of this protocol include: (a) Cl-mediated iPEC; (b) recyclable and reusable BiVO4 photoanodes; (c) straightforward and universal synthetic methods for producing valuable α-branched amines; (d) aminomethylation of C(sp3)–H of hydrocarbons with high bond dissociation energy; (e) high atom and step economy; (f) exceptionally wide substrate range with good tolerance for diverse functional groups; and (g) late-stage modification of biorelevant molecules (Fig. 1c).

Results and discussion

Characterizing the prepared BiVO4 photoanodes

As shown in Fig. 2, the BiVO4 samples were synthesized using a hydrothermal method followed by calcination. Firstly, hydrothermal treatment of a Bi(NO3)3·5H2O and NH4VO3 mixed solution at 150, 175, or 200 °C for 6 h, followed by a subsequent calcination step conducted at 500 °C for 2 h in a muffle furnace. The successfully prepared samples were denoted as BiVO4-150, BiVO4-175, and BiVO4-200. Inspired by previous work24,33,58, the photoanode was prepared. The mixture of the BiVO4 sample and NafionTM resin solution in water/ethanol was sonicated at 0 °C. The resulting solution was subsequently deposited onto the fluorine-doped SnO2 (FTO) conducting glass using a spin-coating technique and then subjected to ultraviolet (UV) irradiation in air.

Subsequently, various characterizations were performed on the synthesized BiVO4 materials. The crystal structure and phase composition of BiVO4‐150/175/200 samples were analyzed through powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) characterization. As illustrated in Fig. 3a, all samples demonstrated identical PXRD patterns that matched well with the standard monoclinic scheelite BiVO4 structure (JCPDS 14-0688), which showed that the modification of the catalyst did not change its crystal structure59. The ultraviolet-visible diffuse reflectance spectrum (UV/vis DRS) revealed prominent absorption features in the 400-500 nm wavelength range (Fig. 3b), demonstrating enhanced light utilization efficiency within the visible spectrum60. The absorption band of BiVO4‐200 was stronger and broader than that of BiVO4‐150/175, demonstrating it has excellent capability in visible light energy utilization. According to the reflection spectrum of the Kubelka-Munk transformation (Supplementary Fig. S25), the absorption bandgaps of BiVO4‐150/175/200 were depicted as 2.44 eV, 2.38 eV, and 2.33 eV61. Meanwhile, in combination with the analytical findings of valence band X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (VB-XPS) (Supplementary Fig. S26), the EVB, NHE and ECB, NHE of BiVO4‐150/175/200 could be calculated to be 2.88 and 0.44 eV, 2.84 and 0.46 eV, 2.81 and 0.48 eV, respectively (Fig. 3c)62. Subsequent analysis focused on the charge carrier dynamics of BiVO4‐150/175/200. As shown in Fig. 3d, the BiVO4‐200 exhibited a significantly lower emission intensity compared to BiVO4‐150/175, indicating its superior charge separation efficiency, which effectively suppresses the recombination of photoinduced charge carriers63. The transient photocurrent (TPC) measurements revealed reproducible response patterns during periodic illumination cycles, with BiVO4-200 demonstrating the most pronounced photocurrent amplitude (Fig. 3e)64. This implied that BiVO4‐200 demonstrates enhanced charge carrier migration and separation capabilities when exposed to visible light illumination. The electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) results showed that the charge transfer resistance decreased in the order of BiVO4-150 > BiVO4-175 > BiVO4-200, which indicated that the electron-hole pair separation was most effective in BiVO4-200 (Fig. 3f)65. Moreover, thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was conducted under air, which disclosed that BiVO4‐150/175/200 were stable up to 800 °C (Supplementary Fig. S24). Next, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of BiVO4‐150/175/200 and commercial BiVO4 were displayed in Fig. 3g-j. In comparison to the earthworm-like mesoporous morphology of conventional electrodeposition-prepared BiVO4 photoanodes39,40, those prepared through secondary calcination exhibit rougher surfaces and pore-like structures. As the hydrothermal temperature increased, this characteristic became more distinctly evident. Conversely, commercial BiVO4 exhibited randomly aggregated structures. We speculate that rougher surface and pore-like structure may facilitate catalytic activity through increased availability of reactive surface sites.

a Powder X-ray diffraction patterns of BiVO4 (JCPDS 14‐0688) and BiVO4‐150/175/200. b Ultraviolet-visible diffuse reflectance spectra of BiVO4‐150/175/200 and corresponding Tauc plots (insets). c The conduction/valence band edges and bandgap of BiVO4‐150/175/200. d Photoluminescence of BiVO4‐150/175/200. e Transient photocurrent response analysis diagram of BiVO4‐150/175/200. f Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy of BiVO4‐150/175/200. g-j Scanning electron microscopy images of BiVO4‐150/175/200 and commercial BiVO4.

Optimization of photoelectrocatalytic Cl-mediated C(sp 3)–H aminomethylation

To evaluate the catalytic activity of the as-prepared BiVO4 photoanode, the multicomponent reaction of aniline 1a, cyclohexanecarboxaldehyde 1b, and cyclohexane 1c was studied in an undivided cell utilizing BiVO4-200 as the anode and Ni plate as the cathode. After systematic investigations, N-(dicyclohexylmethyl)aniline 1 was obtained in 83% isolated yield under the standard condition I, which employed Me4NCl as a dual-functional component serving as both electrolyte and chlorine donor, trifluoromethanesulfonic acid (TfOH) as an additive, CH3CN as solvent, under 400 nm LED light (12 W) with a steady current electrolysis of 3 mA for 10 h at room temperature in an argon atmosphere (Table 1, entry 1). As shown in entries 2-3, modulation of the electrochemical parameter (2 or 4 mA) or photoexcitation condition (365 or 420 nm) consistently induced different levels of yield decrease. Subsequent electrochemical evaluations were performed with alternative anode materials (entries 4-6), including GF( + ), FTO( + ), WO3(+), TiO2(+), BiVO4-150(+), and BiVO4-175(+), which all displayed lower reaction efficiency compared to BiVO4-200(+). In addition, when Pt(-) and Co(-) employed as the cathode, the yields were 87% and 77%, respectively. Given that Ni is more cost-effective than Pt, we opt to use Ni as the cathode material for the system (entry 7). Moreover, when CH3CN was replaced with acetone or DMF, it led to lower yields (entry 8). The failure of DMF as a solvent can be attributed to its reactivity in hydrogen atom transfer (HAT) with Cl radicals (see SI for discussion)66. The experimental results showed that employing Et4NCl and Bu4NCl as electrolytes and chlorine sources are less favorable compared to using Me4NCl in the reaction (entry 9). When trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) or methanesulfonic acid (MsOH) was used as the additive in the reaction instead of TfOH, a decrease in the yield of the desired product was observed. (entry 10). In the absence of Me4NCl or TfOH, the reaction did not result in any product formation (entry 11). A parallel optimization study was conducted to establish suitable reaction conditions using methanol as the radical precursor. The three-component coupling product 2 was successfully obtained with 78% isolated yield under standard condition II, which was carried out in the presence of Et4NCl and TFA, under 400 nm LED light (12 W) with a steady current electrolysis of 2 mA for 12 h at room temperature in an argon atmosphere (entry 12). The BiVO4-150(+) and BiVO4-175(+) photoanodes resulted in poor yield compared to when BiVO4-200(+) was used (entry 13). Employing Ni(-) and Co(-) as cathode materials resulted in a decreased yield of the desired product. (entry 14). When Et4NCl was replaced with Me4NCl in the reaction, the product was obtained in 70% yield (entry 15). Furthermore, using TfOH as the additive instead of TFA had an adverse impact on the reaction performance (entry 16). Performing the reaction in the absence of Et4NCl or TFA resulted in the disappearance of the target product (entry 17). Ultimately, control experiments performed without light and electricity led to a total failure of the reaction (entries 18 and 19), highlighting the crucial roles that light and electricity play in this process.

Optimization of the reaction conditions

aStandard reaction condition I: undivided cell, BiVO4-200 anode (10 × 25 × 1.1 mm3), Ni plate cathode (10 × 15 × 0.1 mm3), 1a (0.3 mmol), 1b (1.5 equiv.), 1c (20.0 equiv.), Me4NCl (25 mol%), TfOH (1.5 equiv.) in dry CH3CN (5.0 mL), 400 nm LED (12 W), constant current = 3 mA, at room temperature for 10 h in Ar. bStandard reaction condition II: undivided cell, BiVO4-200 anode (10 × 25 × 1.1 mm3), Pt plate cathode (10 × 15 × 0.1 mm3), 1a (0.3 mmol), 1b (1.5 equiv.), 1 d (30.0 equiv.), Et4NCl (20 mol%), TFA (2.0 equiv.) in dry CH3CN (5.0 mL), 400 nm LED (12 W), constant current = 2 mA, at room temperature for 12 h in Ar. cYields were evaluated through NMR spectroscopy, utilizing 1,1,2,2-tetrachloroethane as the reference standard. dIsolated yield. N.D. = not detected.

Substrate scope

After determining the best reaction conditions, we explored the substrate range of this multicomponent photoelectrocatalytic Cl-mediated aminomethylation of alkanes (Fig. 4). We first assessed the applicability of aromatic amines with 1b and 1c under standard condition I, yielding the products 1-13 in 58-86% yields. Arylamines with methyl (3), tert-butyl (4), methoxy (5), fluorine (6), chlorine (7), iodine (8), and trifluoromethyl (9) substituents at various sites on the aromatic ring (ortho, meta, and para) were all well-tolerated. The low yield of product 9 may be attributed to the slow condensation of trifluoromethylaniline with cyclohexyl formaldehyde (see SI for discussion). Furthermore, disubstituted aromatic amines were effectively transformed into the corresponding products with satisfactory yields (10 and 11, 77% and 62%). Secondary amines were also effectively transformed into the respective α-branched tertiary amines (12 and 13, 69% and 64%). Next, a wide variety of aliphatic aldehydes were investigated, which led to the corresponding products 14-18 in good yields (62-86%). In addition, a diverse array of aromatic aldehydes containing various electron-donating (-Me, -OMe, -NMe2) or electron-withdrawing (-Br, -CF3, -CO2Me, -Cl, -F) groups at different positions reacted smoothly, resulting in the desired products 19-28 with moderate to good isolated yields (54-88%). Several functional groups, such as methylthio (29), trimethylsilyl and ethynyl (30), and pyridinyl (31) were all compatible in the reaction, obtaining the products in 65-74% yields, further validating its outstanding compatibility with various functional groups of this PEC protocol. Notably, heterocyclic aldehyde also worked well under the optimal conditions, including benzo[b]thiophene-2-carboxaldehyde, benzo[b]furan-2-carboxaldehyde, 5-methylpyridine-2-carboxaldehyde, resulting in products 32-34 with moderate to good yields ranging from 54% to 88%. The slow condensation of aniline with 5-methylpyridine carboxaldehyde, along with the Minisci side reaction, contributed to the low yield of the final target product 34 (see SI for discussion). Furthermore, the scope with respect to alkanes was investigated. Numerous hydrocarbon compounds exhibited excellent performance when employed as coupling components in this three-component synthetic methodology, including norbornane (35), cyclooctane (36, 39), cyclopentane (37), 1-bromoadamantane (38), and cyclododecane (40), which all proceeded smoothly under the standard condition (62-89%). Notably, the reaction exhibited regioselectivity for the C–H bond, predominantly yielding the 1° C–H aminomethylated products (41–43). The reaction selectively took place at the distal methyl position instead of the weaker tertiary C–H bonds, suggesting that steric hindrance is a critical factor in determining the regioselectivity of C–H aminomethylation67.

aStandard condition I is the same as in Table 1.

Subsequently, BiVO4 photoanode was employed in the preparation of β-hydroxy-α-amines using alcohol as the radical precursor (Fig. 5). It is well known that β-hydroxy-α-amine is an important and fundamental structural unit, in particular in peptides and complex natural products68,69. At the outset, various arylamines containing electron-donating (-Me, -OMe) or electron-withdrawing (-F, -Cl, -Br, -CF3) groups were examined under the standard conditions, and delivered the target products in moderate to good yields (44-50, 56-84%). It is worth mentioning that aliphatic, aromatic, and heterocyclic aldehyde were all compatible in this three-component reaction (51-59, 57-86%). Ethanol, isopropanol, tert-butanol were also suitable in this protocol to obtain the target products in moderate yields (60-62, 52-76%). The low yield of the target product 61 may be due to the pinacol-type dimerization of tertiary free radicals and the steric hindrance that these radicals experience (see SI for discussion). Moreover, the C−H bonds adjacent to heteroatoms at α-positions underwent site-selective functionalization with remarkable regiochemical control. Cyclic ethers (63-65) and amides (66, 67), could be aminomethylated under the standard conditions (66-90%). A tetrasubstituted alkene was also explored and smoothly synthesized the target product, although with a modest yield (68, 42%). Significantly, toluene derivatives underwent functionalization selectively at primary benzylic C−H bonds, yielding products 69 and 70 in moderate yields (61% and 68%, respectively).

bStandard condition II is the same as in Table 1.

The diversification of natural products and pharmaceuticals is increasingly achieved through late-stage modification, a strategy that involves attaching diverse functional groups to target compounds to increase their biological performance70,71. The method was additionally extended to the late-stage functionalization of a range of biologically relevant compounds (Fig. 6). Vanillin and Cyclamen aldehyde could directly participate in this three-component system, yielding the products (71, 74, 82) in moderate yields ranging from 46% to 66%. Aromatic aldehyde modified with multifarious natural products and drug molecules (Fenofibric acid, Probenecid, Oleic acid, Citronellol, Ibuprofen, Stigmasterol, Dehydroabietic acid, Phytol, D-α-Tocopherol succinate, and Picaridin) could react with aniline and the radical precursors (cyclohexane and methanol), to successfully lead to the desired products (72, 73, 75-81, 83-90) with isolated yields that were moderate to good (37-77%). These positive results further highlight the methodology’s potential application in drug discovery and development.

aStandard condition I and bStandard condition II are the same as in Table 1.

Synthetic applications

The applicability of this photoelectrochemical protocol was subsequently showcased through large-scale preparations and product derivatizations, as illustrated in Fig. 7a. Gram-scale products 20 and 52 were successfully obtained in good yields using photoelectrochemical methods (for more details, see the SI). Recognizing that alcohols are key intermediates in organic synthesis, several derivatizations of 52 were undertaken. Firstly, condensation reactions of 52 with carboxylic acid or acyl chloride were performed and the corresponding esters (91 and 92) were obtained in high yields. The target compounds, including β-amino amide (93), β-amino thiol (94), and β-amino bromide (96), were successfully synthesized from 52 through nucleophilic substitution reactions, achieving satisfactory yields ranging from 64% to 85%. Moreover, the oxidation of 52 using ruthenium (III) chloride n-hydrate and sodium periodate as reagents successfully produced α-amino acids (95). The conversion of product 52 into the 5-membered carbamate 97 was accomplished using dimethyl carbonate (DMC) as the carbonyl source, while cyclization with thionyl chloride produced product 98 in a yield of 47%. Furthermore, the oxygen heterocycle 99 was synthesized through the palladium-catalyzed intramolecular etherification of compound 53. In addition, the 4-methoxyphenyl group could be removed from product 20 under oxidative conditions using cerium ammonium nitrate (CAN) to afford primary amine (100). Subsequent recyclability testing of the BiVO4 photoanode across five consecutive cycles revealed negligible degradation in performance, demonstrating its robust operational stability (Fig. 7b). The PXRD and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) analyses of the recycled BiVO4 photoanode following five runs showed similarities to those of a freshly synthesized BiVO4 photoanode, which further demonstrates its excellent stability. In addition, SEM showed that the surface of the BiVO4 photoanode became smoother after five cycles (Supplementary Fig. S30).

Mechanistic studies

Next, in order to better elucidate the reaction mechanism, a set of control experiments was conducted, as illustrated in Fig. 8a. The addition of the radical scavenger 2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-1-piperidinyloxy (TEMPO) effectively quenched the model reaction, with high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) analysis confirming the generation of trapped intermediate 101 (Supplementary Fig. S32, see the SI). In addition, the model reaction showed considerable inhibition upon treatment with 2,6-di-tert-butyl-4-methylphenol (BHT), along with the detection of adduct 102 by HRMS (Supplementary Fig. S33). Both of these observations point to the likelihood that a radical pathway, as well as alkyl radicals, may be engaged in this process. Moreover, the addition of ammonium oxalate (HCO2NH4, hole scavenger) or potassium persulfate (K2S2O8, electron scavenger) led to a substantial decrease in the yield of product 1, suggesting that both hole and electron generated in BiVO4 may play a significant role in this transformation. Certainly, the oxidation of aniline by K2S2O8 may also be a significant factor contributing to the severe decrease in yield. As shown in Fig. 8b, product 103 from the radical cascade annulation was isolated at a yield of 40%, which further supports that cyclohexyl radical is generated under standard conditions. Considering that the Cl radical is proposed to function as a HAT agent that aids in alkane activation72,73 we attempted to achieve this process using Cl radical. Based on Xu’s research74, the aminomethylation of cyclohexane using Cl2, generated by combining NaOCl with HCl, yielded the desired product 1 at 35% under light irradiation and without current (Fig. 8c). However, product 1 was not generated when LED light was not present, indicating that Cl2 formation is essential under our photoelectrochemical conditions, and Cl2 may be produced through electrochemical processes. Subsequent experiments were conducted to trap Cl2 under photoelectrochemical and electrochemical conditions using olefins (Fig. 8d). The formation of products 104 and 105 confirmed that Cl2 was indeed produced through an electrochemical process. The enhanced yields of the target products under photoelectrochemical conditions could be attributed to the introduction of light, which boosts the oxidation capability of the holes in the BiVO4 photoanode. It is unusual that product 106 was not detected under photoelectrochemical conditions, which would be a hallmark for Cl radicals via addition to the olefin. We speculate that the Cl2 generated in the system rapidly reacts with the olefins, whereas the small quantity of Cl radicals produced by LED irradiation exhibits low reactivity. Furthermore, the four-component reaction of 1a, 1b, 1c, and 4-methoxystyrene leads to the appearance of the target product 1 under photoelectrochemical conditions, whereas no target product 1 was generated under electrochemical conditions alone, suggesting that light is essential for the homolytic cleavage of Cl2 to generate Cl radicals. In an effort to capture the crucial radical intermediates, we conducted the electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) experiment using 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide (DMPO) (Fig. 8e). EPR spectroscopy analysis indicated the generation of carbon-centered radicals through an intermolecular HAT mechanism, which were swiftly captured by DMPO to produce relatively stable free radicals (g = 2.0057, ANG = 14.60, and AHG = 21.43)75,76. Meanwhile, other chlorine sources were investigated under optimal conditions and showed lower yields than Me4NCl (Fig. 8f).

Kinetic isotope effect (KIE) studies yielded distinct values of 1.4 and 1.9 for parallel and competitive reactions, respectively, implying that the HAT step may not serve as the rate-limiting step in the reaction mechanism (Fig. 9a). In addition, a divided-cell experiment was conducted (Fig. 9b). As anticipated, the product 1 was found in the anode chamber, yielding 42%, indicating that the photoelectrochemical C(sp3)–H aminomethylation took place near the BiVO4 photoanode. Cyclic voltammetry (CV) experiments were then conducted (Fig. 9c). The CV of Me4NCl displayed two significant oxidation signals at 0.91 V and 2.07 V (vs Ag/AgNO3). In contrast, no apparent oxidation peak for cyclohexanecarboxaldehyde 1b, cyclohexane 1c, and TfOH in the region of 0-3 V. Although there was a clear oxidation peak of aniline 1a, it was suppressed when using BiVO4-200 as the working photoanode (with light illumination). Surprisingly, the oxidation peak of Me4NCl did not suppress and increased to 1.04 V and 2.21 V (vs Ag/AgNO3). We hypothesize that the photogenerated holes in the BiVO4 photoanode decrease the electricity input, and the swift condensation of aniline with aldehydes collaborates to inhibit excessive oxidation of aniline, while Cl- may be drawn to the holes and oxidized due to electrostatic interactions. The results of the CV tests indicated that the anode’s electrochemical oxidation of Me4NCl occurred earlier than the oxidation of other components in the reaction sequence. In addition, we performed CV tests on Me4NCl and aniline with different scan rates, and the linear fit to the Randles-Sevcik equation provided that Cl- possesses a greater diffusion capacity in the system compared to aniline, further suggesting that Cl- is oxidized preferentially over aniline during the anodic oxidation process (Supplementary Figs. S51-54, see the SI). It is worth mentioning that experiments involving the on/off control of light and electricity were performed (Supplementary Figs. S46-48), and the transformation was hindered without light or electricity, which validates the necessity of both conditions. In light of the findings from the aforementioned experiments, a potential reaction mechanism featuring a radical pathway was suggested for this three-component reaction, as illustrated in Fig. 9d. Firstly, the excitation of the BiVO4 photoanode by incident photons resulted in the generation of electron-hole pairs. At the surface of the photoanode, Cl- was oxidized by holes to generate Cl2, which subsequently produced Cl radicals via light-driven homolytic cleavage. Meanwhile, in situ condensation of the amine and aldehyde under acidic conditions afforded an electrophilic iminium Int-I. The Cl radical further underwent a HAT process with hydrocarbons to form a more reactive alkyl radical, which then reacted with Int-I to produce amine radical cation Int-II via radical addition. Int-II followed by a HAT process leading to N-centered cation Int-III, which subsequently underwent deprotonation and released the final product. The reduction of protons at the cathode surface produces H2, thereby making sacrificial oxidants unnecessary.

To summarize, we have presented an efficient, stable, and recyclable BiVO4 photoelectrode material, with a focus on achieving Cl-mediated C(sp3)–H aminomethylation of alkanes with high bond dissociation energy (BDE) in a PEC cell. Our approach was carried out under mild conditions and does not require transition metals or oxidants. This transformation benefits from the use of commercially available reagents, high atom and step economy, and broad substrate scope. The proposed mechanism was grounded in the findings from the CV tests and mechanistic experiments. Due to its environmentally friendly and energy-efficient characteristics, we find the PEC technique particularly appealing for organic chemistry, and we plan to further explore its application in our laboratory.

Methods

General procedure for the preparation of BiVO4 photoanodes

The synthesis of BiVO4 materials involved dissolving Bi(NO3)3·5H2O (970.1 mg, 2 mmol) in 40 mL of 2 mol/L HNO3, resulting in a clear solution (Solution A). Simultaneously, NH4VO3 (234.0 mg, 2 mmol) was dissolved in 20 mL of 2 mol/L NaOH, followed by the addition of 20 mL EG, forming another clear solution (Solution B). Solution A was gradually introduced into Solution B under continuous agitation in an ice-cooled environment. The mixture transitioned from colorless to light yellow and eventually to an orange-yellow colloidal suspension. This suspension was placed in a Teflon-lined autoclave and subjected to hydrothermal treatment at varying temperatures (150, 175, or 200 °C) for 6 h. Post-reaction, the product was isolated via centrifugation, rinsed with ethanol and deionized water, and dried at 60 °C under vacuum. Final calcination at 500 °C for 2 h in a muffle furnace yielded the desired BiVO4 materials. The successfully prepared samples were denoted as BiVO4-150, BiVO4-175, and BiVO4-200, corresponding to BiVO4 synthesized as the first step at 150, 175, and 200 oC, respectively. Then, the mixture of 50 mg BiVO4 sample and 10 wt% NafionTM resin solution (0.3 mL) in water/ethanol (1/1, 0.15 mL) was sonicated at 0 °C for 1 h. The resulting mixture was then spin-coated onto the fluorine-doped SnO2 (FTO) conducting glass at 1000 rpm for 30 s and then subjected to ultraviolet (UV) irradiation in air for 20 h. Note: prior to experimental utilization, FTO conductive glass substrates underwent a standardized cleaning protocol involving sequential immersion in a ternary solvent system composed of acetone, isopropanol, and deionized water (1:1:1 v/v ratio) to eliminate surface organic residues and particulate contaminants.

General Procedure for Photoelectrocatalytic Cl-mediated C(sp 3)–H aminomethylation

The standard condition I. The electrocatalytic reaction was performed in a single-compartment electrochemical cell under controlled operational parameters. The system configuration comprised a BiVO4-200 photoanode (10 × 25 × 1.1 mm3) paired with a nickel plate cathode (10 × 15 × 0.1 mm3). The reaction mixture was prepared by sequentially charging the pre-dried cell containing a magnetic stirrer with amine substrate (0.30 mmol), aldehyde component (0.45 mmol, 1.5 equiv.), alkanes (20 equiv.), TfOH (67.5 mg, 0.45 mmol, 1.5 equiv.) and Me4NCl (8.3 mg, 0.075 mmol, 0.25 equiv.), followed by the addition of acetonitrile (5 mL) as solvent. The photoelectrocatalytic process was executed under an argon atmosphere at ambient temperature with simultaneous application of 3 mA constant current and 400 nm LED irradiation (12 W) over 10 h duration. Post-reaction processing involved ultrasonic-assisted electrode purification with ethyl acetate (3 × 5 mL), with subsequent combination of washings to the main reaction mixture. The workup procedure comprised aqueous phase dilution (15 mL H2O) followed by triple ethyl acetate extraction (3 × 30 mL). The combined organic fractions underwent dehydration (anhydrous Na2SO4), filtration, and rotary evaporation prior to final purification through silica gel column chromatography to isolate target compounds.

Standard condition II. The electrocatalytic reaction was performed in a single-compartment electrochemical cell under controlled operational parameters. The system configuration comprised a BiVO4-200 photoanode (10 × 25 × 1.1 mm3) paired with a Pt plate cathode (10 × 15 × 0.1 mm3). The reaction mixture was prepared by sequentially charging the pre-dried cell containing a magnetic stirrer with amine substrate (0.30 mmol), aldehyde component (0.45 mmol, 1.5 equiv.), alcohol or other substrate (30 equiv.), TFA (68.4 mg, 0.60 mmol, 2.0 equiv.) and Et4NCl (10.0 mg, 0.06 mmol, 0.2 equiv.), followed by the addition of acetonitrile (5 mL) as solvent. The photoelectrocatalytic process was executed under an argon atmosphere at ambient temperature with simultaneous application of 2 mA constant current and 400 nm LED irradiation (12 W) over 12 h duration. Post-reaction processing involved ultrasonic-assisted electrode purification with ethyl acetate (3 × 5 mL), with subsequent combination of washings to the main reaction mixture. The workup procedure comprised aqueous phase dilution (15 mL H2O) followed by triple ethyl acetate extraction (3 × 30 mL). The combined organic fractions underwent dehydration (anhydrous Na2SO4), filtration, and rotary evaporation prior to final purification through silica gel column chromatography to isolate target compounds.

Data availability

The authors declare that all experimental details, mechanistic investigations, catalyst and product characterization data, HRMS results, and NMR spectra are included in the main text and Supplementary Information. Any relevant data can be acquired from the corresponding author if needed. Source data are provided in this paper.

References

Wei, S. et al. Metal-insulator-semiconductor photoelectrodes for enhanced photoelectrochemical water splitting. Chem. Soc. Rev. 53, 6860–6916 (2024).

Lu, H. & Wang, L. Unbiased photoelectrochemical carbon dioxide reduction shaping the future of solar fuels. Appl. Catal. B Environ. Energy 345, 123707 (2024).

Reid, L. M., Li, T., Cao, Y. & Berlinguette, C. P. Organic chemistry at anodes and photoanodes. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2, 1905–1927 (2018).

Miao, Y. & Shao, M. Photoelectrocatalysis for high-value-added chemicals production. Chin. J. Catal. 43, 595–610 (2022).

Introduction: Photochemistry in Organic Synthesis. Chem. Rev. 116, 9629-9630 (2016).

Yan, M., Kawamata, Y. & Baran, P. S. Synthetic organic electrochemical methods since 2000: On the verge of a renaissance. Chem. Rev. 117, 13230–13319 (2017).

Hardwick, T., Qurashi, A., Shirinfar, B. & Ahmed, N. Interfacial photoelectrochemical catalysis: Solar-induced green synthesis of organic molecules. ChemSusChem 13, 1967–1973 (2020).

Zhu, C., Ang, N. W. J., Meyer, T. H., Qiu, Y. & Ackermann, L. Organic electrochemistry: Molecular syntheses with potential. ACS Cent. Sci. 7, 415–431 (2021).

Wu, S., Kaur, J., Karl, T. A., Tian, X. & Barham, J. P. Synthetic molecular photoelectrochemistry: New frontiers in synthetic applications, mechanistic insights and scalability. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202107811 (2022).

Melchiorre, P. Introduction: Photochemical catalytic processes. Chem. Rev. 122, 1483–1484 (2022).

Qian, L. & Shi, M. Contemporary photoelectrochemical strategies and reactions in organic synthesis. Chem. Commun. 59, 3487–3506 (2023).

Kim, H., Kim, H., Lambert, T. H. & Lin, S. Reductive electrophotocatalysis: Merging electricity and light To achieve extreme reduction potentials. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 2087–2092 (2020).

Barham, J. P. & König, B. Synthetic photoelectrochemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 11732–11747 (2020).

Huang, H., Steiniger, K. A. & Lambert, T. H. Electrophotocatalysis: Combining light and electricity to catalyze reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 12567–12583 (2022).

Yang, Y. et al. Photoelectrochemical C−H activation through a quinacridone dye enabling proton-coupled electron transfer. ChemSusChem 16, e202201980 (2023).

Cao, Y., Huang, C. & Lu, Q. Photoelectrochemically driven iron-catalysed C(sp3)−H borylation of alkanes. Nat. Synt. 3, 537–544 (2024).

Won, S., Park, D., Jung, Y., Kim, H. & Chung, T. D. A photoelectrocatalytic system as a reaction platform for selective radical-radical coupling. Chem. Sci. 15, 16705–16714 (2024).

Lamb, M. C. et al. Electrophotocatalysis for organic synthesis. Chem. Rev. 124, 12264–12304 (2024).

Tateno, H., Iguchi, S., Miseki, Y. & Sayama, K. Photo-electrochemical C−H bond activation of cyclohexane using a WO3 photoanode and visible light. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 11238–11241 (2018).

Li, Z. et al. Photoelectrocatalytic C–H halogenation over an oxygen vacancy-rich TiO2 photoanode. Nat. Commun. 12, 6698 (2021).

Xiao, M., Wang, Z., Maeda, K., Liu, G. & Wang, L. Addressing the stability challenge of photo(electro)catalysts towards solar water splitting. Chem. Sci. 14, 3415–3427 (2023).

Yu, J. et al. Basic comprehension and recent trends in photoelectrocatalytic systems. Green Chem. 26, 1682–1708 (2024).

Fujishima, A. & Honda, K. Electrochemical photolysis of water at a semiconductor electrode. Nature 238, 37–38 (1972).

Tateno, H., Miseki, Y. & Sayama, K. Photoelectrochemical dimethoxylation of furan via a bromide redox mediator using a BiVO4/WO3 photoanode. Chem. Commun. 53, 4378–4381 (2017).

Mesa, C. A. et al. Kinetics of photoelectrochemical oxidation of methanol on hematite photoanodes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 11537–11543 (2017).

Zhang, L. et al. Photoelectrocatalytic arene C–H amination. Nat. Catal. 2, 366–373 (2019).

Qiao, K. et al. Minisci-type dehydrogenative coupling of C(sp3)–H and N-heteroaromatics enabled by photoelectrochemical hydrogen atom tansfer. Org. Lett. 26, 5805–5810 (2024).

Chen, Y. et al. Scalable decarboxylative trifluoromethylation by ion-shielding heterogeneous photoelectrocatalysis. Science 384, 670–676 (2024).

Bae, S. et al. A hole-selective hybrid TiO2 layer for stable and low-cost photoanodes in solar water oxidation. Nat. Commun. 15, 9439 (2024).

Yu, J., Saada, H., Abdallah, R., Loget, G. & Sojic, N. Luminescence amplification at BiVO4 photoanodes by photoinduced electrochemiluminescence. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 15157–15160 (2020).

Jiang, W. et al. Stress-induced BiVO4 photoanode for enhanced photoelectrochemical performance. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 304, 121012 (2022).

Wang, J. et al. Al2O3-Coated BiVO4 photoanodes for photoelectrocatalytic regioselective C−H activation of aromatic amines. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202315478 (2023).

Li, T. et al. Photoelectrochemical oxidation of organic substrates in organic media. Nat. Commun. 8, 390 (2017).

Wu, Y.-C., Song, R.-J. & Li, J.-H. Recent advances in photoelectrochemical cells (PECs) for organic synthesis. Org. Chem. Front. 7, 1895–1902 (2020).

Luo, L. et al. Photoelectrocatalytic synthesis of aromatic azo compounds over porous nanoarrays of bismuth vanadate. Chem. Catal. 3, 100472 (2023).

Wang, J. et al. Customized photoelectrochemical C−N and C−P bond formation enabled by tailored deposition on photoanodes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202408901 (2024).

Wang, J. et al. Photoelectrochemical Ni-catalyzed cross-coupling of aryl bromides with amine at ultra-low potential. Nat. Commun. 15, 6907 (2024).

Wang, J.-H. et al. Photoelectrochemical cell for P–H/C–H cross-coupling with hydrogen evolution. Chem. Commun. 55, 10376–10379 (2019).

Liu, X. et al. Bromide-mediated photoelectrochemical epoxidation of alkenes using water as an oxygen source with conversion efficiency and selectivity up to 100. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 19770–19777 (2022).

Qiao, K. et al. Acceptorless dehydrogenation of N-heterocycles in a photoelectrochemical Cell. ACS Catal. 13, 14763–14769 (2023).

Tolod, K. R. et al. Optimization of BiVO4 photoelectrodes made by electrodeposition for sun-driven water oxidation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 45, 605–618 (2020).

Yamada, K.-i., Yamamoto, Y., Maekawa, M., Chen, J. & Tomioka, K. Direct aminoalkylation of cycloalkanes through dimethylzinc-initiated radical process. Tetrahedron Lett. 45, 6595–6597 (2004).

Deng, G. & Li, C.-J. Peroxide-mediated efficient addition of cycloalkanes to imines. Tetrahedron Lett. 49, 5601–5604 (2008).

Hager, D. & MacMillan, D. W. C. Activation of C–H bonds via the merger of photoredox and organocatalysis: A coupling of benzylic ethers with Schiff bases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 16986–16989 (2014).

Li, P. et al. Iron-catalyzed multicomponent C–H alkylation of in situ generated imines via photoinduced ligand-to-metal charge transfer. Org. Lett. 26, 6347–6352 (2024).

Babawale, F., Murugesan, K., Narobe, R. & König, B. Synthesis of unnatural α-amino acid derivatives via photoredox activation of inert C(sp3)–H bonds. Org. Lett. 24, 4793–4797 (2022).

Caner, J., Matsumoto, A. & Maruoka, K. Facile synthesis of 1,2-aminoalcohols via α-C–H aminoalkylation of alcohols by photoinduced hydrogen-atom transfer catalysis. Chem. Sci. 14, 13879–13884 (2023).

Leone, M., Milton, J. P., Gryko, D., Neuville, L. & Masson, G. TBADT-Mediated photocatalytic stereoselective radical alkylation of chiral N-sulfinyl imines: Towards efficient synthesis of diverse chiral amines. Chem. Eur. J. 30, e202400363 (2024).

Li, P. et al. Facile and general electrochemical deuteration of unactivated alkyl halides. Nat. Commun. 13, 3774 (2022).

Li, P., Kou, G., Feng, T., Wang, M. & Qiu, Y. Electrochemical NiH-catalyzed C(sp3)−C(sp3) coupling of alkyl halides and alkyl alkenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202311941 (2023).

Li, P. et al. Nickel-electrocatalysed C(sp3)–C(sp3) cross-coupling of unactivated alkyl halides. Nat. Catal. 7, 412–421 (2024).

Siu, J. C., Fu, N. & Lin, S. Catalyzing electrosynthesis: A homogeneous electrocatalytic approach to reaction discovery. Acc. Chem. Res. 53, 547–560 (2020).

Qi, X.-K. et al. Multicomponent synthesis of α-branched tertiary and secondary amines by photocatalytic hydrogen atom transfer strategy. Org. Lett. 23, 4473–4477 (2021).

Lai, X.-L. & Xu, H.-C. Photoelectrochemical asymmetric catalysis enables enantioselective heteroarylcyanation of alkenes via C–H functionalization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 18753–18759 (2023).

Yang, D. et al. Electrochemical oxidative difunctionalization of diazo compounds with two different nucleophiles. Nat. Commun. 14, 1476 (2023).

Zou, L., Xiang, S., Sun, R. & Lu, Q. Selective C(sp3)–H arylation/alkylation of alkanes enabled by paired electrocatalysis. Nat. Commun. 14, 7992 (2023).

Schmid, S. et al. Photoelectrochemical heterodifunctionalization of olefins: Carboamidation using unactivated hydrocarbons. ACS Catal. 14, 9648–9654 (2024).

Masuda, R. et al. Heterogeneous single-atom zinc on nitrogen-doped carbon catalyzed electrochemical allylation of imines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 11939–11944 (2023).

Samanta, S., Khilari, S., Pradhan, D. & Srivastava, R. An efficient, visible light driven, selective oxidation of aromatic alcohols and amines with O2 using BiVO4/g-C3N4 nanocomposite: A systematic and comprehensive study toward the development of a photocatalytic process. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 5, 2562–2577 (2017).

Wang, S. et al. New BiVO4 dual photoanodes with enriched oxygen vacancies for efficient solar-driven water splitting. Adv. Mater. 30, 1800486 (2018).

Chen, H. et al. Identifying dual functions of rGO in a BiVO4/rGO/NiFe-layered double hydroxide photoanode for efficient photoelectrochemical water splitting. J. Mater. Chem. A 8, 13231–13240 (2020).

Lu, Y. et al. Boosting charge transport in BiVO4 photoanode for solar water oxidation. Adv. Mater. 34, 2108178 (2022).

Shi, C., Dong, X., Wang, X., Ma, H. & Zhang, X. Ag nanoparticles deposited on oxygen-vacancy-containing BiVO4 for enhanced near-infrared photocatalytic activity. Chin. J. Catal. 39, 128–137 (2018).

Yang, J. et al. Fe−N Co-doped BiVO4 photoanode with record photocurrent for water oxidation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 64, e202416340 (2024).

Gao, R. T. & Wang, L. Stable cocatalyst-free BiVO4 photoanodes with passivated surface states for photocorrosion inhibition. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 23094–23099 (2020).

Das, S. et al. Photocatalytic (Het)arylation of C(sp3)–H bonds with carbon nitride. ACS Catal. 11, 1593–1603 (2021).

Gonzalez, M. I. et al. Taming the chlorine radical: Enforcing steric control over chlorine-radical-mediated C–H activation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 1464–1472 (2022).

Li, Q., Yang, S. B., Zhang, Z. H., Li, L. & Xu, P. F. Diastereo- and enantioselective synthesis of β-hydroxy-α-amino acids: Application to the synthesis of a key intermediate for Lactacystin. J. Org. Chem. 74, 1627–1631 (2009).

Yoshioka, S., Nagatomo, M. & Inoue, M. Application of two direct C(sp3)–H functionalizations for total synthesis of (+)-Lactacystin. Org. Lett. 17, 90–93 (2015).

Wencel-Delord, J. & Glorius, F. C–H bond activation enables the rapid construction and late-stage diversification of functional molecules. Nat. Chem. 5, 369–375 (2013).

Wang, C., Qi, R., Wang, R. & Xu, Z. Photoinduced C(sp3)–H functionalization of glycine derivatives: preparation of unnatural α-amino acids and late-stage modification of peptides. Acc. Chem. Res. 56, 2110–2125 (2023).

Bonciolini, S., Noël, T. & Capaldo, L. Synthetic applications of photocatalyzed halogen-radical mediated hydrogen atom transfer for C−H bond functionalization. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2022, e202200417 (2022).

Sadeghi, M. C(sp3)−H Functionalization using chlorine radicals. Adv. Synth. Catal. 366, 2898–2918 (2024).

Xu, P., Chen, P.-Y. & Xu, H.-C. Scalable photoelectrochemical dehydrogenative cross-coupling of heteroarenes with aliphatic C−H bonds. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 14275–14280 (2020).

Liu, Y. C. et al. Time-resolved EPR revealed the formation, structure, and reactivity of N-centered radicals in an electrochemical C(sp3)–H arylation reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 20863–20872 (2021).

An, Q. et al. Identification of alkoxy radicals as hydrogen atom transfer agents in Ce-catalyzed C–H functionalization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 359–376 (2023).

Acknowledgements

Financial support from the National Key R&D Program of China (2023YFA1507203), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 22371149, 22301144, 22188101), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. 63223015), Frontiers Science Center for New Organic Matter, Nankai University (Grant No. 63181206) and Nankai University are gratefully acknowledged. We thank the Haihe Laboratory of Sustainable Chemical Transformations for financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.Q. supervised the project, and provided guidance on the project. Y.Q. and A.S. conceived and designed the study. A.S. developed the methods and performed the mechanistic studies. A.S. and P.X. prepared the substrates and studied the scope. Y.Q., P.X., and Y.W. revised the manuscript with feedback from other authors. All the authors were involved in the discussion and analysis of the data.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shi, A., Xie, P., Wang, Y. et al. Photoelectrocatalytic Cl-mediated C(sp3)–H aminomethylation of hydrocarbons by BiVO4 photoanodes. Nat Commun 16, 2322 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-57567-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-57567-2

This article is cited by

-

Bimetallic [Co/K] hydrogen evolution catalyst for electrochemical terminal C-H functionalization

Nature Communications (2025)