Abstract

The US Food and Drug Administration approves tissue-agnostic therapies to target tumor biomarkers regardless of tumor type. In light of the growing number of such approvals in recent years, a better understanding of their relative clinical benefit across cancer types is required. To address this need, we analyzed tissue-agnostic indications (TMB-High, MSI-High/MMRd, BRAFV600E mutations, and NTRK and RET fusions) in a database of 295,316 molecularly-profiled tumor samples with associated clinical outcomes data. Here, we show that 21.5% of tumors harbored at least one of the tissue-agnostic indications investigated, including 5.4% lacking a cancer-specific indication. Our analysis reveals poor uptake of targeted therapies for rare NTRK fusions, significant differences in pembrolizumab-associated outcomes across tumor types for TMB-High and MSI-High/MMRd, as well as clinical benefits in tumor types and drugs of the same class not investigated in the pivotal clinical trials. These results demonstrate that treatment effects are not necessarily tissue-agnostic, and suggest possible expansion of therapeutic avenues for a given tissue-agnostic indication.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

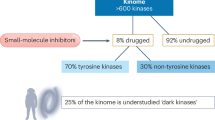

Recent years have seen the advent of several new United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approvals known as tissue-agnostic indications. Tissue-agnostic drugs target “specific molecular alteration(s) across multiple cancer types as defined, for example by organ, tissue, or tumor type”, per the FDA’s guidance1. Implicit in this definition is the expectation of clinical benefit across biomarker-positive patient populations regardless of tissue lineage.

To date, there have been eight approved indications across seven different therapeutic agents, as shown in Table 1, and the pace of approvals has increased recently, with four occurring since 2022. These approvals represent a diverse mixture of molecular targets, including cancers with high tumor mutational burden (TMB) and/or microsatellite instability (MSI)/mismatch repair deficiency (MMRd), as well as more specific indications related to individual mutations (e.g., BRAFV600E), fusion transcripts (e.g., NTRK1,2,3 and RET), and most recently, the overexpression of the oncogene HER22,3,4,5,6,7,8,9. In 2022, the FDA released a draft guidance regarding such tissue-agnostic approvals1.

While tissue-agnostic approvals have expanded the treatment landscape for many cancers and have undoubtedly benefited numerous patients, there remains a poor understanding of the comparative clinical benefit across cancer types for therapies approved for tissue-agnostic indications10. Previously, we reported that within a single tissue-agnostic indication, there exists some important nuances regarding specific thresholds for patients to derive maximal benefit10.

In this current work, we performed a large pan-cancer analysis on a substantially updated data set and expanded the analysis to comprehensively address the inter-cancer variability in clinical benefit for tissue agnostic indications, including rare indications and tumor types that have proven difficult to study in the setting of clinical trials. We relied heavily on the combination of real-world approaches using insurance claims databases, combined with next-generation sequencing (NGS) data within the Caris Life Sciences database to evaluate the burden of disease embodied in these indications, as well as evaluate the practical therapeutic implications of tissue-agnostic indications in a real-world setting. We show that tissue-agnostic indications are prevalent, but therapeutic benefits are variable across tumor types. As such, our work provides valuable insights into the emerging benefits of real-world database analyses to further our understanding of the clinical application of tissue-agnostic cancer therapies.

Results

Variability in prevalence of tissue-agnostic indications across tumor types

To establish a comprehensive understanding of the molecular burden of tissue-agnostic indications in the cancer population in a real-world setting, we performed a census of the Caris dataset of 295,316 human tissue samples from 57 tumor types (female: 170,201; male: 125,115; median age: 65 y), focusing on 5 highly clinically relevant indications (TMB-High, MSI-High/MMRd, BRAFV600E, NTRK1/2/3 fusions, and RET gene fusions). Notably, these molecular alterations are interrogated as part of standard comprehensive molecular profiling tests requested by treating physicians for patients with metastatic or advanced diseases to guide treatment, allowing for an unbiased evaluation. On the contrary, HER2 immunohistochemistry (IHC) was not performed uniformly across cancer types prior to the recent tissue-agnostic approval, leading to frequency bias, and was therefore not included. Our analysis demonstrated immense variability in the frequency of the investigated tissue-agnostic indications across human tumor lineages, ranging from a low of 0% (pituitary carcinoma) to a high of 87% (basal cell skin cancer) (Fig. 1, Supplementary Data 1). NTRK1/2/3 and RET gene fusions were rare molecular events across the spectrum of tumors, with most tumor types displaying 0-0.3% frequency. Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) displayed the highest percentage (1.1%) of NTRK gene fusions (Fig. 1, Supplementary Data 1). In general, the difference in overall frequencies of applicable tissue-agnostic indications was largely related to the inherent mutability of individual cancer types, as measured via TMB, with smaller contributions from BRAFV600E mutations, MSI-High/MMRd, and fusions (Supplementary Data 1). Collectively, this data suggests that with the current FDA indications, 21.5% of all cancer patients are candidates for a tissue-agnostic drug, a stunning molecular burden with widespread therapeutic, economic, and educational implications. Of these patients, 17% had a single alteration, 3% had two alterations, and 1% had three or more alterations. Even when subtracting patients whose tumors possessed a cancer-specific indication, an impressive 5.4% of patients were still candidates for a tissue-agnostic drug. We also analyzed prevalence data according to demographic information, including age, sex, race, and ethnicity, which revealed subtle variations in prevalence across demographic factors in certain cancer types (Supplementary Data 2 and 3).

The heatmap shows alteration frequency among indicated tumor types for each alteration. Pan-tumor cohort sizes that were investigated were as follows: TMB-High (n = 262,429), MSI-High/MMRd (n = 251,968), BRAFV600E (n = 248,181), NTRK1/2/3 or RET fusions (n = 226,566), and any positive (n = 181,463). Therapies associated with each biomarker are indicated at the top. Black boxes indicate cancer types with cancer-specific drug approvals. Red boxes indicate cancer types with cancer-specific and biomarker-specific drug approvals. Specifically, dabrafenib + trametinib are indicated in melanoma and pediatric low-grade glioma for BRAFV600E/K; pembrolizumab is indicated in triple negative breast cancer (TNBC); selpercatinib is indicated in RET-mutated medullary thyroid cancer; and entrectinib is indicated in ROS1 fusion-positive non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). More details are available in Supplementary Data S1.

Poor clinical uptake of drugs for rare tissue-agnostic indications

The availability of real-world data gave us the opportunity to evaluate the clinical uptake of drugs granted a tissue-agnostic approval for a rare indication. As demonstrated above, NTRK gene fusions are one of the rarest tissue-agnostic indications (0.2% of all cases), for which two FDA-approved agents (larotrectinib and entrectinib) exist6,7. These agents are both relatively non-toxic and highly active and would therefore seem fine candidates for widespread use in eligible patients. Using insurance claims data, we observed that only a minority of patients with NTRK fusions (around one-third in any given year) received such treatment, and this rate was relatively stable over time (Fig. 2A). We confirmed this observation through analysis of electronic health records (performed in collaboration with ConcertAI), with highly congruent results: only 17/45 patients (37.8%) with an NTRK gene fusion received an NTRK-targeting drug. Further, when we interrogated electronic medical records of patients with NTRK fusions enrolled in the Caris Precision Oncology observational ROADMAP study, only 14/28 subjects (50%) were administered NTRK inhibitors.

A Clinical uptake of NTRK-targeted therapies (larotrectinib or entrectinib) from 2019 to 2022. A total of 81 patients were treated with NTRK inhibitors out of 216 patients with tumors positive for NTRK fusions (37.5%). Percentages may add up to greater than 100% due to rounding. B Immune-oncology (IO) biomarker prevalence in patients treated (n = 81) or not treated (n = 135) with NTRK-targeting drugs. Statistical significance was calculated using Fisher’s exact test.

While several reasons may exist for this failure to use demonstrably safe, effective drugs, one observed trend seen in our dataset is that patients who did not receive an NTRK-targeting agent were more likely to be either MSI-High (21% vs 2.5%) or TMB-High (24% vs 6.2%) than those receiving such an agent (Fig. 2B). This observation suggests preferential use of a checkpoint inhibitor in these patients, though as checkpoint inhibitors are not usually curative, it fails to explain the subsequent lack of use of an NTRK-targeting agent.

Clinical applicability of tissue-agnostic indications across tumor types

We next addressed whether patients receiving tissue-agnostic treatments demonstrate similar treatment benefit and overall survival (OS) across different cancer types—in other words, whether these treatments can truly be considered tissue-agnostic. While some tissue-agnostic indications have relatively small numbers of patients treated across the spectrum of tumor types in our dataset (particularly for recently approved agents), we could readily address this question for the two most common tissue-agnostic indications—TMB-High and MSI-High/MMRd—as well as, to some extent, for BRAFV600E mutations. For TMB-High and MSI-High/MMRd, we observed significant differences between tumor types for median time on treatment (TOT) and OS from start of pembrolizumab, using data derived from our large claims database (Fig. 3, Supplementary Data 4–9). In the setting of TMB-High cancers, significantly prolonged (P < 0.05) TOT with pembrolizumab compared to the global median (i.e., the median TOT of all patients in the treated cohort) was observed for tumor types including melanoma and NSCLC, as opposed to cancers of the bladder, pancreas, prostate, breast, and esophageal/gastroesophageal junction (GEJ), as well as high grade gliomas and small cell lung cancers (SCLC). For instance, median TOT for NSCLC was 4.9 months [95% confidence interval (CI): 4.5–5.1 months] compared to 2.4 months (95% CI: 0.8–2.9 months) for SCLC (Fig. 3A, Supplementary Data 4). We observed similar differences across tumor types for OS from start of pembrolizumab in patients with TMB-High tumors. Namely, patients with endometrial cancer, melanoma, squamous cell skin cancer, colorectal adenocarcinoma (CRC), and ovarian surface epithelial carcinomas all displayed significantly prolonged OS compared to the global median (i.e., the median OS of all patients in the treated cohort), while patients with NSCLC, head and neck cancers, breast cancer, esophageal/GEJ carcinomas and SCLC displayed significantly shorter OS (P < 0.05) (Fig. 3B, Supplementary Data 5).

Median pembrolizumab TOT (A, C, E) and OS (B, D, F) for patients with TMB-High tumors (A, B), MSI-High/MMRd tumors (C, D), or the MSS/MMRp subset of TMB-High tumors (E, F). Whiskers indicate 95% confidence intervals; when no endcap is shown, upper 95% CI is undefined. Dotted line indicates median TOT or OS across cancer types (i.e., global median of all patients in cohort). Black asterisks indicate cancer types with median TOT/OS significantly higher than global median and red asterisks indicate median TOT/OS lower than the global median. Shown are cancer types with n ≥ 40 patients (A, B), n ≥ 10 patients (C, D), and n ≥ 25 patients (E, F). ‘n’ for each tumor type and analysis is shown in parentheses on the y-axis. HRs were computed utilizing the Cox proportional hazards model, and P values were assessed by two-sided log-rank test (no multiple comparison testing). Full tables of all cancer types are shown in Supplementary Data S4–9.

In the case of MSI-High/MMRd, variability in TOT with pembrolizumab was also seen across cancer types, ranging from 3.0 months (95% CI: 2.1–4.6 months) for prostate cancer to 6.3 months (95% CI: 5.5–7.3 months) for CRC. Since it is a rarer molecular event than TMB-High, relatively wider confidence intervals were present for TOT across several cancer types (Fig. 3C, Supplementary Data 6). Similar significant differences in OS from start of pembrolizumab were observed for MSI-High/MMRd cancers (Fig. 3D, Supplementary Data 7). Of note, when exploring microsatellite stable (MSS)/TMB-High tumors, we observed some differences in responsive tumor types than we observed among TMB-High tumors, suggesting that further refinement of biomarker selection can better identify responsive tumor types. For instance, patients with CRC displayed significantly longer median OS compared to the global median when examining the TMB-High and MSI-High/MMRd subsets, but significantly shorter median OS when examining the MSS/TMB-High population (Fig. 3E, F, Supplementary Data 8 and 9).

We also investigated the variability in response to dabrafenib plus trametinib among BRAFV600E-mutant cancers across tissue lineages. Although patient numbers were lower for this analysis (a total of 568 patients across all cancer types), this data mirrors the variability observed for pembrolizumab response in TMB-High and MSI-High/MMRd tumors—namely, patients with CRC exhibited shorter median TOT and OS and patients with melanoma displayed longer median TOT and OS relative to the global median (Fig. 4). Together, our results indicate that tissue-agnostic agents are highly tissue-specific with regard to crucial clinical outcomes across cancer types, plausibly stemming from inherent biological differences between tumor types.

Median TOT (A) and OS from treatment start (B) for indicated cancer types is shown. The dotted line indicates median TOT or OS across cancer types. Whiskers indicate 95% confidence intervals. Black asterisks indicate cancer types with TOT or OS significantly higher than global median and red asterisks indicate cancer types with TOT or OS significantly lower than global median. n ≥ 16 patients; ‘n’ for each tumor type and analysis is shown in parentheses on the y-axis. HRs were computed utilizing the Cox proportional hazards model, and P values were assessed by two-sided log-rank test (no multiple comparison testing).

Extrapolation of tissue-agnostic indications to non-trial supported tumor types

Initial studies underlying tissue-agnostic approvals frequently underrepresented or omitted tumor types11,12,13,14,15,16,17. Real-world data, however, are greatly empowered to overcome such limitations. We examined a total of 1031 patients who were treated with pembrolizumab and had cancer types not included in either KEYNOTE-15811 or the retrospective study by Cristescu et al.18. In this analysis, we observed significantly improved TOT [5.53 m (95% CI: 5.1–6.2 m)] and OS [20.04 m (95% CI: 17.93–22.73 m)] for patients with TMB-High tumors compared to their TMB-Low counterparts [3.26 m (95% CI: 3.0–3.5 m) and 10.56 m (95% CI: 9.9–11.1 m), respectively] (Fig. 5A, B). These findings held true in the MSS/mismatch repair proficient (MMRp) subset of TMB-High tumors as well (Fig. 5C, D). Furthermore, we observed nearly identical pembrolizumab TOT and OS for patients with TMB-High tumors that included non-trial tumor types as for patients with TMB-High tumors of trial-investigated lineages (Fig. 5E, F). Together, these data justify and strengthen the tissue-agnostic FDA approval of pembrolizumab for TMB-High cancers, which was based on data from limited cancer types.

A, B Time-on-treatment (TOT) with pembrolizumab (A) and overall survival (OS) from start of pembrolizumab (B) in patients with non-trial investigated tumor types (KEYNOTE-158; Cristescu et al.18), comparing patients with TMB-High tumors (red lines; n = 1024 for TOT and n = 1025 for OS) and TMB-Low tumors (blue lines, n = 2327 for TOT and n = 2875 for OS). C, D Pembrolizumab TOT (C) and OS (B) in patients with non-trial investigated tumor types, comparing the MSS/MMRp subset of patients with TMB-High tumors (red lines; n = 683 for TOT and n = 805 for OS) and TMB-Low tumors (blue lines; n = 2146 for TOT and n = 2656 for OS). E, F Pembrolizumab TOT (E) and OS (F) for patients with TMB-High tumors, comparing trial investigated tumor types (red lines; n = 8183 for TOT and n = 9435 for OS) with non-trial tumor types (blue lines; n = 1024 for TOT and n = 1205 for OS). The shaded area surrounding the lines indicates 95% CI. HRs and P values were calculated using Cox Proportional Hazards model and log-rank test, respectively. HR hazard ratio, CI confidence interval.

Extrapolation of tissue-agnostic indications to other members of a therapeutic class

Finally, we investigated the question of whether tissue-agnostic indications given to one member of a therapeutic class may be extrapolatable to other members of the same class. We approached this question by examining real-world outcomes data for nivolumab, a drug with a similar mechanism of action as pembrolizumab, but that lacks tissue-agnostic FDA approval for TMB-High tumors. Comparing patients with TMB-High cancers as well as MSS/TMB-High cancers to their TMB-Low and MSS/TMB-Low counterparts, we found similar benefit from treatment with nivolumab as pembrolizumab when considering all cancer types combined, as well as in many individual cancer types (Table 2). Similarly, pembrolizumab and nivolumab showed near identical TOT hazard ratios (HRs; 0.792 and 0.807, respectively) comparing patients with MSI-High/MMRd tumors to those with MSS tumors (Supplementary Data 10). Therefore, we propose that real-world data can serve as a powerful tool to support the extension of tissue-agnostic indications to other members of a class of drugs not included in the initial approval.

As demonstrated above (Fig. 3), it is evident that not all tumor types exhibit a significant improvement in TOT with pembrolizumab for TMB-High tumors compared to their TMB-Low counterparts. Interestingly, this lack of uniform improvement was evident for both pembrolizumab and nivolumab but was observed in different tumor types for each (Table 2). For example, patients with TMB-High gastric cancer and soft tissue tumors demonstrated significantly prolonged TOT with pembrolizumab compared to patients with TMB-Low tumors, while no such effect was seen for nivolumab. In contrast, patients with TMB-High melanoma and neuroendocrine tumors showed significantly prolonged TOT with nivolumab, but not pembrolizumab, compared to patients with TMB-Low tumors. It’s important to note that real-world evidence underscores the disparity in nivolumab usage across various cancer types compared to pembrolizumab. The scarcity of clinical data limits the evaluation of nivolumab’s effectiveness in numerous cancer types due to low numbers of patients. Nevertheless, the available clinical data unequivocally supports an association between TMB-High and nivolumab clinical benefit across a range of cancer types, as seen for pembrolizumab.

A similar approach was undertaken to explore the relationship between TMB-High and clinical benefit of various other immune checkpoint inhibitors (durvalumab, atezolizumab, cemiplimab, avelumab, and dostarlimab). Considering all cancer types collectively, a notable prolongation of TOT was observed for patients with TMB-High tumors compared to those with TMB-Low tumors, with HRs ranging from 0.67 (avelumab, 95% CI: 0.559–0.795) to 0.873 (atezolizumab, 95% CI: 0.812–0.939) (Supplementary Data 11). Due to the modest HR values seen for multiple drugs in this analysis and the limited availability of clinical data for most cancer types, further data collection is needed before any conclusions can be drawn regarding the potential for tissue-agnostic approval of these drugs. Regarding clinical benefit of these additional immune checkpoint inhibitors for patients with MSI-High/MMRd tumors relative to MSS/MMRp, low cohort sizes also precluded solid conclusions (Supplementary Data 12).

Discussion

A tissue-agnostic indication represents a highly desired outcome for any new agent used to treat metastatic cancer. As such, the pharmaceutical industry has developed multiple new agents in recent years meeting the FDA’s guidelines for tissue-agnostic therapeutic approvals. However, the original studies supporting tissue-agnostic approvals exhibit limitations stemming from inadequate numbers of certain tumor types and arguably insufficient types of tissues11,12,13,14,15,16,17,19,20,21,22,23,24. The existence of large and growing numbers of NGS datasets with associated clinical data offers us the opportunity to perform deeper dives into important questions regarding tissue-agnostic indications. The analysis presented herein, performed on data from 295,316 tumors, provides valuable insights into several important questions.

First, and unsurprisingly, there is impressive variance regarding the prevalence of tissue agnostic indications, with overall frequencies ranging from 0 to 87% across tissue types. In this regard, our results parallel those of the American Association of Cancer Research (AACR)’s Project Genie25, but critically go further by analyzing real-world outcomes associated with these tissue-agnostic indications. Globally, we observed that tissue-agnostic indications are common, whether viewed with or without subtraction of overlapping tissue-specific indications (21.5% and 5.4%, respectively). The majority of patients have a single tissue-agnostic indication, though a small percentage harbor 2–3 tissue-agnostic indications.

Secondly, real-world data suggest that for rarer indications such as NTRK gene fusions, uptake of associated agents—despite high efficacy and relatively low toxicity12,14—has been poor. Claims data do not allow examination of the oncologist’s thought processes in any great depth, though a partial explanation may be the higher frequency of TMB-High and MSI-High/MMRd cancers in untreated patients, funneling them toward immune checkpoint blockade instead. Regardless, these data suggest the need for further education of oncologists regarding tissue-agnostic indications that they may only rarely encounter.

Thirdly, our evidence suggests that the term tissue-agnostic should not be understood to imply that all cancer types with an approved tissue-agnostic biomarker respond equally well to an approved agent. Where we had data to adequately analyze this question (TMB-High and MSI-High/MMRd cancers, and to a somewhat lesser extent BRAFV600E-mutant cancers), clinically and statistically significant differences exist across tumor types (also see multivariate analysis in Supplementary Data 13) and within/across histological subtypes (Supplementary Fig. 1). While demonstrating whether these differences represent differences in cancer biology or other factors such as number and types of prior regimens is beyond the scope of our current study, our findings provide corroborating evidence that clinical benefit is not tissue-agnostic in any meaningful sense, substantially adding to our previous report on variable TMB thresholding10. Together, these data may call into question the very concept of tissue-agnostic as a therapeutic or biologic construct, and provide valuable tissue-specific insight into the clinical application of tissue-agnostic indications.

Finally, while our data show substantial variability in therapy responses across tumor types, it also demonstrates the feasibility of extrapolation to tumor types not included in the initial studies used to support some tissue-agnostic approvals, with encouraging results. Relative to patients in the pivotal trials, patients with non-trial tumor types in our dataset displayed highly similar median TOT with pembrolizumab for TMB-High and MSI-High indications. However, rarer and/or more recently approved tissue-agnostic indications will require larger numbers of treated patients and longer clinical follow-ups to support such generalizations. Furthermore, our data suggest that real-world data can support extrapolation of a tissue-agnostic indication to other members of the same class. Comparing the checkpoint inhibitors nivolumab and pembrolizumab in the setting of TMB-High and MSI-High/MMRd cancers, HRs for median times on treatment were quite similar, suggesting that nivolumab (and perhaps other checkpoint inhibitors) might be a reasonable alternative for tissue-agnostic indications in these two categories. Although this approach may not be feasible for many targeted therapies, which are rarely used outside of approved indications in clinical practice, immune checkpoint inhibitors such as nivolumab are frequently administered beyond TMB-High and MSI-High/MMRd indications. As TMB and MSI status are routinely assessed through comprehensive NGS testing, ample real-world data exist to investigate whether these tissue-agnostic markers can be extended to nivolumab.

There are a few limitations to our study. First, due to the real-world nature of the cohort, we were unable to control for clinical variables such as stage, grade, patient status, or other treatment regimens. We also encountered the persistent challenge of studying rare indications and rare tumor types, although our data highlights the importance of further analysis of these patients in order to understand how to best treat them. Similarly, data on the benefit of nivolumab or other similar checkpoint inhibitors has lagged behind pembrolizumab, although these drugs may offer similar therapeutic benefits or even improved outcomes in select tumor types. Importantly, we demonstrate that real-world data can generate insight into such questions and inform physician decisions on patient treatment as well as future clinical investigations.

Together, our study provides a comprehensive evaluation of clinical outcomes in the largest cohort of patients treated based on tissue-agnostic indications reported to date. By both expanding potential therapeutic avenues for a given tissue-agnostic indication and identifying tumor types most likely to benefit, we illustrate the vast potential for real-world data to inform the clinical implementation of tissue-agnostic drug approvals.

Methods

Patient cohort and molecular profiling

This study was conducted in accordance with guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, Belmont report, and U.S. Common rule. In keeping with 45 CFR 46.101(b)(4), this study was performed utilizing retrospective, deidentified clinical data. Therefore, it is considered IRB-exempt and no patient consent was required. Exempt status was determined by WCG IRB. Tumor samples of cancer patients that underwent comprehensive tumor profiling at Caris Life Sciences (Phoenix, AZ, USA) from 2015 to 2023 were included in this study. Sex (as reported by the patient’s physician) and self-reported race/ethnicity were collected but were not considered in the study design (instead, all samples with successful sequencing results were included in the analysis). Prior to molecular testing, tumor enrichment was achieved by harvesting targeted tissue using manual microdissection techniques (≥20% tumor content required for DNA and ≥10% for RNA). NGS was performed on genomic DNA isolated from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tumor samples using the NextSeq (592-whole gene panel) or NovaSeq 6000 (enhanced depth of coverage on 720 genes recurrently altered in cancer) platforms (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA). All variants were detected with >99% confidence based on allele frequency and bait panel coverage, with an average sequencing depth of coverage >500× and an analytic sensitivity of 5%. Genetic variants identified were interpreted by board-certified molecular geneticists according to the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) standards.

Gene fusion detection was performed on mRNA isolated from FFPE tumor samples using the Illumina NovaSeq platform (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA) and Agilent SureSelect Human All Exon V7 bait panel (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). Qiagen RNA FFPE tissue extraction kits were used for extraction, and RNA quality and quantity were determined using the Agilent TapeStation. Biotinylated RNA baits were hybridized to the synthesized and purified cDNA targets and the bait-target complexes were amplified in a post capture PCR reaction. The resultant libraries were quantified and normalized, and the pooled libraries were denatured, diluted, and sequenced; the reference genomes used were GRCh37/hg19 or GRCh38/hg38, and analytical validation of this test demonstrated ≥97% positive percent agreement (PPA), ≥99% negative percent agreement (NPA) and ≥99% overall percent agreement (OPA) with a validated comparator method.

TMB was measured by counting all non-synonymous missense, nonsense, in-frame insertion/deletion and frameshift mutations found per tumor that had not been previously described as germline alterations in dbSNP151, Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD) databases, or benign variants identified by Caris geneticists. A cutoff point of ≥10 mutations per MB was used based on the KEYNOTE-158 pembrolizumab trial11. Caris Life Sciences is a participant in the Friends of Cancer Research TMB Harmonization Project26.

A combination of multiple test platforms was used to determine the MSI or MMR status of the tumors profiled, including IHC using antibodies for MLH1 (M1), MSH2 (G2191129), MSH6 (44), and PMS2 (EPR3947; Ventana Medical Systems, Inc., Tucson, AZ); and NGS ( > 2800 target microsatellite loci were examined and compared to the reference genomes hg19 or hg38 from the University of California, Santa Cruz (UCSC) Genome Browser database). The two platforms generated highly concordant results as previously reported27, and in the rare cases of discordant results, IHC results were prioritized.

Clinical data collection and endpoint calculation

Real-world clinical data were obtained from insurance claims, which encompass detailed records of health services, including prescribed medications, procedures performed, and established diagnoses. TOT was determined as the interval from the initiation to the conclusion of treatment with an indicated therapy. OS was defined as the period from treatment initiation to the date of the patient’s last known clinical activity. In cases with no insurance claims for a period exceeding 100 days, it was inferred that the patient had deceased. Conversely, patients with a documented clinical activity within 100 days prior to the latest data update were censored in the analysis28. Kaplan–Meier survival estimates were generated for cohorts defined by molecular characteristics. HRs were computed utilizing the Cox proportional hazards model, and significant differences in survival times were assessed with the log-rank test, where P < 0.05 was considered significant. To study the clinical uptake of NTRK inhibitors, separate queries of EMR (electronic medical record) data from the Caris Precision Oncology observational ROADMAP study (Caris Retrospective Real-world Outcomes-Associated Database, Multi-site Precision Oncology Alliance TM Protocol (ROADMAP): https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT03326479) and ConcertAI (real-world data leveraging various sources including EMR and insurance claims and enriched by artificial Intelligence: www.concertai.com) on overlapping patients with molecular data were performed, in addition to investigation of the insurance claims data. Statistical analysis was performed using standard functions in JMP® 18.1.0. No custom code or software was used.

Data availability

The deidentified sequencing data are owned by Caris Life Sciences and cannot be publicly shared due to the data usage agreement in place. These data will be made available to researchers for replication and verification purposes through our letter of intent process, which are generally fulfilled with 6 months. For more information on how to access this data, please contact Joanne Xiu at jxiu@carisls.com. The summarized, processed data generated in this study are provided in the Supplementary Data file.

References

United States Food and Drug Administration. GUIDANCE DOCUMENT: Tissue Agnostic Drug Development in Oncology, Draft Guidance for Industry. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/tissue-agnostic-drug-development-oncology (2022).

Adashek, J. J., Kato, S., Sicklick, J. K., Lippman, S. M. & Kurzrock, R. If it’s a target, it’s a pan-cancer target: tissue is not the issue. Cancer Treat. Rev. 125, 102721 (2024).

United States Food and Drug Administration. FDA grants accelerated approval to fam-trastuzumab deruxtecan-nxki for unresectable or metastatic HER2-positive solid tumors. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-grants-accelerated-approval-fam-trastuzumab-deruxtecan-nxki-unresectable-or-metastatic-her2 (2024).

United States Food and Drug Administration. FDA grants accelerated approval to pembrolizumab for first tissue/site agnostic indication. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-grants-accelerated-approval-pembrolizumab-first-tissuesite-agnostic-indication (2017).

United States Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves pembrolizumab for adults and children with TMB-H solid tumors. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-approvals-and-databases/fda-approves-pembrolizumab-adults-and-children-tmb-h-solid-tumors (2020).

United States Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves larotrectinib for solid tumors with NTRK gene fusions. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/fda-approves-larotrectinib-solid-tumors-ntrk-gene-fusions-0 (2018).

United States Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves entrectinib for NTRK solid tumors and ROS-1 NSCLC. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-entrectinib-ntrk-solid-tumors-and-ros-1-nsclc (2019).

United States Food and Drug Administration. FDA grants accelerated approval to dabrafenib in combination with trametinib for unresectable or metastatic solid tumors with BRAF V600E mutation. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-grants-accelerated-approval-dabrafenib-combination-trametinib-unresectable-or-metastatic-solid (2022).

United States Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves selpercatinib for locally advanced or metastatic RET fusion-positive solid tumors. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-selpercatinib-locally-advanced-or-metastatic-ret-fusion-positive-solid-tumors (2022).

Muquith, M. et al. Tissue-specific thresholds of mutation burden associated with anti-PD-1/L1 therapy benefit and prognosis in microsatellite-stable cancers. Nat. Cancer 5, 1121–1129 (2024).

Marabelle, A. et al. Association of tumour mutational burden with outcomes in patients with advanced solid tumours treated with pembrolizumab: prospective biomarker analysis of the multicohort, open-label, phase 2 KEYNOTE-158 study. Lancet Oncol. 21, 1353–1365 (2020).

Drilon, A. et al. Efficacy of larotrectinib in TRK fusion-positive cancers in adults and children. N. Engl. J. Med. 378, 731–739 (2018).

Subbiah, V. et al. Tumour-agnostic efficacy and safety of selpercatinib in patients with RET fusion-positive solid tumours other than lung or thyroid tumours (LIBRETTO-001): a phase 1/2, open-label, basket trial. Lancet Oncol. 23, 1261–1273 (2022).

Demetri, G. D. et al. Updated integrated analysis of the efficacy and safety of entrectinib in patients with NTRK fusion-positive solid tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 28, 1302–1312 (2022).

Salama, A. K. S. et al. Dabrafenib and trametinib in patients with tumors with BRAF(V600E) mutations: results of the NCI-MATCH trial subprotocol H. J. Clin. Oncol. 38, 3895–3904 (2020).

Marabelle, A. et al. Efficacy of pembrolizumab in patients with noncolorectal high microsatellite instability/mismatch repair-deficient cancer: results from the phase II KEYNOTE-158 Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 38, 1–10 (2020).

Maio, M. et al. Pembrolizumab in microsatellite instability high or mismatch repair deficient cancers: updated analysis from the phase II KEYNOTE-158 study. Ann. Oncol. 33, 929–938 (2022).

Cristescu, R. et al. Tumor mutational burden predicts the efficacy of pembrolizumab monotherapy: a pan-tumor retrospective analysis of participants with advanced solid tumors. J. Immunother. Cancer 10, e003091 (2022).

Genentech Inc. ROSLYTREK® (entrectinib). Prescribing Information. https://www.gene.com/download/pdf/rozlytrek_prescribing.pdf (2024).

GlaxoSmithKline. JEMPERLI® (dostarlimab-gxly). Prescribing Information. https://gskpro.com/content/dam/global/hcpportal/en_US/Prescribing_Information/Jemperli/pdf/JEMPERLI-PI-MG.PDF (2023).

Loxo Oncology Inc. VITRAKVI® (larotrectinib). Prescribing Information. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/211710s000lbl.pdf (2018).

Merck Sharp & Dohme L. L. C. KEYTRUDA® (pembrolizumab). Prescribing Information. https://www.merck.com/product/usa/pi_circulars/k/keytruda/keytruda_pi.pdf (2024).

Novartis. MEKINIST® (trametinib). Prescribing Information. https://www.novartis.com/us-en/sites/novartis_us/files/mekinist.pdf (2024).

Novartis. TAFINLAR® (dabrafenib). Prescribing Information. https://www.novartis.com/us-en/sites/novartis_us/files/tafinlar.pdf (2024).

Gouda, M. A., Nelson, B. E., Buschhorn, L., Wahida, A. & Subbiah, V. Tumor-agnostic precision medicine from the AACR GENIE database: clinical implications. Clin. Cancer Res. 29, 2753–2760 (2023).

Merino, D. M. et al. Establishing guidelines to harmonize tumor mutational burden (TMB): in silico assessment of variation in TMB quantification across diagnostic platforms: phase I of the Friends of Cancer Research TMB Harmonization Project. J. Immunother. Cancer 8, e000147 (2020).

Vanderwalde A., Spetzler, D., Xiao, N., Gatalica, Z. & Marshall J. Microsatellite instability status determined by next-generation sequencing and compared with PD-L1 and tumor mutational burden in 11,348 patients. J. Cancer Med. 7, 746–756 (2018).

Abraham, J. P. et al. Clinical validation of a machine-learning-derived signature predictive of outcomes from first-line oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy in advanced colorectal cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 27, 1174–1183 (2021).

Eli Lilly and Company. RETEVMO® (selpercatinib). Prescribing Information. https://uspl.lilly.com/retevmo/retevmo.html#pi (2022).

Daiichi Sankyo Inc. and AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP. ENHERTU® (fam-trastuzumab deruxtecan-nxki). Prescribing Information. https://daiichisankyo.us/prescribing-information-portlet/getPIContent?productName=Enhertu&inline=true (2024).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: G.W.S., T.Y., and J.X. Formal analysis: J.X., A.H., S.K., B.G., J.J.G., and J.A. Investigation: G.W.S., J.X., A.H., S.K., B.G., J.J.G., J.R.R., M.J.O., M.R., J.A., and D.S. Resources: J.E., M.J.O., G.W.S., M.R., and D.S. Data curation: J.X., A.H., S.K., B.G., J.J.G., and J.A. Writing—original draft: G.W.S. and J.X. Writing—-review and editing: J.R.R. and J.X., all authors reviewed and approved. Visualization: J.R.R. and J.X. Supervision: G.W.S., M.R., and D.S.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

G.W.S., T.Y., J.X., A.H., J.R.R., S.K., B.G., J.J.G., M.J.O., M.R., J.A., and D.S. are employees of Caris Life Sciences. J.E. is CEO of ConcertAI. T.Y. reports honoraria from Chugai Pharmaceutical, Takeda Pharmaceutical, Merck Biopharma, Bayer Yakuhin, Ono Pharmaceutical and MSD K.K.; consulting fee from Sumitomo Corp.; and research grant from Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Chugai Pharmaceutical, Daiichi Sankyo. Eisai, FALCO biosystems, Genomedia, Medical & Biological Laboratories, Merus N.V., Molecular Health GmbH, MSD, Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim, Ono Pharmaceutical, Pfizer Japan, Roche Diagnostics, Sanofi, Sysmex, Taiho Pharmaceutical and Takeda Pharmaceutical.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Adam Palmer and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sledge, G.W., Yoshino, T., Xiu, J. et al. Real-world evidence provides clinical insights into tissue-agnostic therapeutic approvals. Nat Commun 16, 2646 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-57941-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-57941-0

This article is cited by

-

Comparison of trastuzumab deruxtecan and sacituzumab govitecan in HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer: a large real-world data analysis

Breast Cancer Research (2025)

-

Tissue-agnostic cancer therapies: promise, reality, and the path forward

Nature Communications (2025)