Abstract

Designing highly active, cost-effective, stable, and coke-resistant catalysts is a hurdle in commercializing bio-oil steam reforming. Single-atom alloys (SAAs) are captivating atomic ensembles crosschecking affordability and activity, yet their stability is held questionable by trial-and-error synthesis practices. Herein, we employ descriptor-based density functional theory (DFT) calculations to elucidate the stability, activity, and regeneration of Ni-based SAA catalysts for acetic acid dehydrogenation. While 12 bimetallic candidates pass the cost/stability screening, they uncover varying dehydrogenation reactivity and selectivity, introduced by favoring different acetic acid adsorption modes on the SAA sites. We find that Pd-Ni catalyst provokes the utmost H2 activity, however, ab-initio molecular simulations at 873 K reveals the ability of Cu-Ni site to effectively desorb hydrogen compared to Pd-Ni and Ni, attributed to the narrowed surface charge depletion region. Notably, this Cu-Ni performance is coupled with enhancing C*-gasification and acetic acid dehydrogenation with respect to Ni. Building upon these findings, DFT-screening of trimetallic M1-M2-Ni co-dopants recognizes 6 novel modulated single-sites with high stability, balanced H*-adsorption, and anti-coking susceptibility. This work provides invaluable data to accelerate the discovery of affordable and efficient bimetallic and trimetallic SAA catalysts for bio-oil upgrading to green hydrogen.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

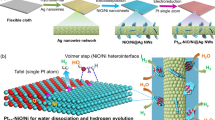

The conceptualization of a “hydrogen economy” became a progressively advancing framework to drive a sustainable and clean energy source1,2. In industrial settings, steam reforming of natural gas or shale gas (methane) is by far the predominant reforming strategy for the generation of hydrogen (H2), which can be dated back to the early 19th century of conventional fossil fuel processing refineries3,4. In the current transition to the hydrogen economy, steam reforming of bio-oil, produced by 70–80 wt.% from biomass fast pyrolysis5, offers a viable and sustainable route for producing clean hydrogen with a null CO2 generation, given the end-cycle of recycling back the CO2 via biomass photosynthesis to be once again harnessed4. Moreover, although direct steam reforming of crude bio-oil is feasible, bio-oil fractionation through water addition can facilitate the separation of crude bio-oil into (i) aqueous-rich and (ii) organic-rich phases6. The former phase, enriched in water and light oxygenated compounds, makes a much-suited and retrofitted feedstock for future hydrogen generation7. In addition, the lateral hydrophobic phase of lignin-derived oligomers can be upgraded via hydrodeoxygenation (HDO) to value-added products and aromatic-based biofuels8.

Acetic acid is commonly used as a simple, yet effective probe molecule to model the bio-oil aqueous fraction for numerous reasons, mainly boiling down to (i) its highest concentration reaching up to 32 wt.%9,10, (ii) its wide-ranging functional groups of C=C, C=O, C\(-\)O, C\(-\)H, and O\(-\)H bonds, and (iii) being a representative compound of the carboxylic acids in bio-oil11. The catalyst selection is a critical factor in directing acetic acid conversion to H2. Although nickel is extensively used and firmly established in the steam methane reforming (SMR) process1, serving as an economically viable and readily available catalyst with strong activity, its susceptibility to deactivation via carbon deposition, metal oxidation, and particle sintering is regarded as the main hurdles1. Alternatively, noble metals are coke-resistant and offer the highest activity12,13, yet their main drawback is their lesser accessibility and prohibitive costs. Thus, research endeavors are motivated towards the discovery of cost-effective base metal alloys, such as Ni-based catalysts, with enhanced coke resistance and boosted catalytic performance14,15.

Previous experimental studies have reported the successful synthesis and boosted performance of ameliorated bimetallic and trimetallic single-atom alloys (SAA) catalytic candidates for H2-production from acetic acid upgrading. For instance, a recent study by Ding et al.7 investigated a series of Ni-Mg-Cr catalysts with Cr2O3 or MgCr2O4 supports for reforming acetic acid towards H2-production, discovering that Ni4-MgCr2O4 catalyst offers superior hydrogen production while mitigating coke deposition through effective gasification of adsorbed species (e.g., C* and O*). While such experimental efforts lie at the core of upscaling an H2 production process for aqueous bio-oil upgrading, they are discursive in literature and based on a trial-and-error approach. In view of this, discoveries of each experimental study are limited to a handful of additive combinations, hampering the comparison of the catalysts’ performances16. Nevertheless, lengthy synthesis, extensive characterization, and performance tests can be directed via reliable theoretical screening tools17,18,19. Adopting density functional theory (DFT) computations as a first-principles-based comprehensive hierarchical workflow can accelerate the design of stable, active, and coke-resistant SAA catalysts with coordinated sites of bimetallic and trimetallic modulations. DFT analysis has been applied to screen feasible functionalized metallic electrocatalysts/photocatalysts on an immense scope for reactions involving CO2, H2, O2, and H2S reactants20,21,22,23. Research endeavors within these studies have focused on capturing catalytic activity and selectivity with simple (linear or nearly linear) relations, volcano plots, and activity maps24. For instance, a linear scaling correlation relating the reaction energy of a catalytic step to its transition state is recognized in heterogenous catalysis as the Brønsted−Evans−Polanyi relationship25. On a fundamental basis, these attempts offer “shortcut methods” to rationalize the Sabatier principle26, a conceptual term in catalysis referring to a golden region of balanced adsorption strength and reaction kinetics27. Going beyond the tips of the volcano-curve “cliffs” is helpful in discovering efficient materials with geometric and electronic regulations28. Yet, to the best of our knowledge, the rational design of optimum and cost-effective SAA catalysts for H2 production from bio-oils catalytic upgrading has often been neglected from computational studies. A challenging aspect arises from the structural complexity of modeled bio-oil compounds, provoking far greater adsorption modes relative to the catalyst active-sites compared to their applications, involving simpler diatomic (i.e., O2 and H2) or triatomic (i.e., CO2) species. Moreover, within the recent computational hunt for novel catalysts, the search for SAAs is often confined to the bimetallic family of materials20,21,22,29, whereas a focus on trimetallic DFT-screening is limited, despite potentially offering unprecedented performance23. In practice, this is marked by synergistic interactions between co-dopants (i.e., two types of guest atoms incorporated into the host) and SAA ensembles. These are anticipated to offer advantages over bimetallic counterparts (i.e., one type of guest atom incorporated into the host)30,31. Understanding the stability and activity of trimetallic SAA surfaces, especially those tailored specifically for bio-oil dehydrogenation, could have unexploited benefits in biofuel catalysis research.

Effective SAA catalysts for bio-oil reforming to H2 must maneuver around key pitfalls of stability, affordability, selectivity, coke regeneration, and susceptibility. In the pursuit of an inclusive catalyst design, we have developed a DFT descriptor assessment to design effective and affordable bimetallic and trimetallic nickel-based single-atom sites for technologically advancing hydrogen production from acetic acid. Spin-polarized DFT calculations were performed to test the stability and activity of 26 transition metal dopants as bimetallic and trimetallic SAA Ni-based catalysts compared against monometallic nickel catalysts. Moreover, ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) was used to provide understanding of the imperative dynamic evolution of H-adsorbed species on selected SAA catalysts relative to nickel, corroborating the predictions of the DFT descriptors assessment. This systematic protocol expedites the discovery of next-generation SAAs bimetallic and trimetallic ensembles for fabrication and synthesis.

Results

Screening workflow

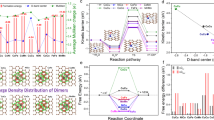

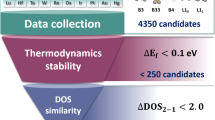

Figure 1 illustrates the hierarchical DFT-screening roadmap of 26 transition metal dopants benchmarked against a pristine Ni surface. Tc and Hg elements were omitted from the screening owing to their radioactivity and limited solid stability, respectively. High-throughput spin-polarized simulations were first performed on bimetallic Ni-based SAA catalysts (MxNi1-x, x = 0.0156, hereinafter denoted M-Ni), and subsequently explored using trimetallic (MxMyNi1-x-y, x + y = 0.0313, expressed as M1-M2-Ni). The approach began with addressing the important aspects of stability, affordability, and carbon-clustering. In the next steps, the stable combinations were evaluated based on balancing acetic acid adsorption and selective dehydrogenation against dehydroxylation, promoting H2 production, coke gasification, and enabling facile H2O dissociation. This inclusive approach helps underpin their catalytic performance, corroborated by AIMD simulations of H2 production at 873 K. We ended by modulating the surface properties of trimetallic SAA M1-M2-Ni catalysts, examining their stability and catalytic performance by simple yet effective DFT-descriptors. Details of the chosen descriptors are provided in the “Methods” section.

From top to bottom in the figure, the 26-dopants are screened based on their (1) stability: aggregation energy (\(\Delta {E}_{{agg}}\)), segregation energy (\(\Delta {E}_{{seg}}\)), surface energy (\(\gamma\)), carbon-clustering; 4 C* reaction energy (\(\Delta {E}_{{rxn}{,}_{4C}}\)), and price ($·kg−1). Then, (2) acetic acid adsorption (\({E}_{{{ads},}_{C{H}_{3}{COOH}}}\)) and dehydrogenation (\(\Delta {E}_{{rxn}}\)) energies are assessed. (3) H2 production activity is evaluated based on 2H* adsorption energy (\({E}_{{ads}{,}_{2H}}\)) and \(\Delta {E}_{{rxn}}\) of 2H*\(\to\)H2*. The SAA catalysts’ (4) coke formation and regeneration are considered through C* and O* adsorption energies (\({E}_{{ads}{,}_{C+O}}\)) and \(\Delta {E}_{{rxn}}\) of C* + O* \(\to\) CO*. Steam reforming is captured through (5) water dissociation (\(\Delta {E}_{{rxn}}\) of H2O*\(\to\)H* + OH*) and H* and OH* adsorption energy (\({E}_{{ads}{,}_{H+{OH}}}\)). Finally, screening of trimetallic combinations is executed to provide novel SAA M1-M2-Ni catalysts candidates. Inserted figures denote the bimetallic and trimetallic SAA Ni-based configurations.

Regulation of single-atom alloying sites

The aggregation energy (\(\Delta {E}_{{agg}}\), see Eq. (1) in “Methods”) of the M-Ni surfaces was first computed to test the stability of the dilute M-dopant from aggregating into dimer or trimer clusters (see Fig. 2a). Collectively, the results predict a strong propensity of the M-dopants to occupy isolated single sites owing to their positive \(\Delta {E}_{{agg}}\). This excludes Re-Ni, Os-Ni, and Fe-Ni with designated negative or borderline values (\(\Delta {E}_{{agg}}\le\) 0.1 eV). Note that \(\Delta {E}_{{agg}}\) exhibits a descending trend across each d-series from IIIB to IIB, suggesting that the dispersion tendency is highest among early transition metals, which diminishes as we progress down the group.

a aggregation energy, \(\Delta {E}_{{agg}}\) (eV), of dimers and trimers dopants formation into Ni host. \(\Delta {E}_{{agg}} > \) 0.0 eV symbols for the propensity towards occupying isolated single sites, whereas \(\Delta {E}_{{agg}} < \) 0.0 eV designates favoring dimer or trimer aggregation. b screening of SAA catalysts based on segregation energy (\(\Delta {E}_{{seg}}\)), carbon clustering (\(\Delta {E}_{{rxn}{,}_{4C}}\)), and market price. Segregation energy indicates dopant surface segregation tendency or bulk occupancy (\(\Delta {E}_{{seg}} > \) 0 eV: favorable; \(\Delta {E}_{{seg}} < \) 0 eV: undesirable). Vertical axis: reaction energy of forming 4C* chain (\(\Delta {E}_{{rxn}}{,}_{4C}\)). Less negative \(\Delta {E}_{{rxn}}{,}_{4C}\) indicates higher resistance to coking on the M-Ni surfaces. The inset depicts 4C optimized conformation on SAA M-Ni surfaces. Color bar represents SAA combinations prices; (i.e., M-Ni_($·Kg−1) = Dopant_($·Kg−1)\(\times\)0.0156+Ni_($·Kg−1) \(\times\)(1−0.0156)). Cost-effective SAA M-Ni catalysts are ones with price \( < \)1500 $·Kg-1. c surface energy, \({\gamma }_{M-{Ni}(111)}\) (J·m−2), of bimetallic single-atom alloy M-Ni(111) surfaces. Red values denote M-Ni mixtures less stable than Ni(111) (i.e., \({\gamma }_{M-{Ni}(111)}\ge {\gamma }_{{Ni}(111)}\)). Solid blackline, \({\gamma }_{{Ni}(111)}\) = 1.86 J·m−2. d Hydrogen induced segregation energy compared with vacuum segregation of SAA M-Ni surfaces. 3H*-adsorbed on the 1st nearest neighbor hcp-hollow sites simulate the M-dopants \(\Delta {E}_{{seg}}\) after rapid bio-oil dehydrogenation to H2 production. Inserted figures denote the SAA configurations top views in the distinct environments. Single-atom dopants in a, b, and d are arranged by their d-series from right to left (IIIB to IIB group), then up to down (3 d to 5 d). Data available in Zenodo.

The stability of M-dopant sites to remain on the surface, their coking susceptibility, and economic feasibility are shown in Fig. 2b, where the segregation energy (\(\Delta {E}_{{seg}}\), Eq.(2)) is presented as a useful index to screen the bimetallic SAA stability on the uppermost layer vs. the possibility of such sites to segregate to the bulk. Obtained results for \(\Delta {E}_{{seg}}\) match the values of 5 and 11 dopants previously reported by Zhou et al.32 and Alareeqi et al.8, respectively. This reveals twelve stable and economically viable SAA M-Ni catalysts, having \(\Delta {E}_{{seg}} > \) 0 eV and market prices less than 1500 $·Kg−1 (see details of the price calculation in the figure caption of Fig. 2b). Apart from the previously verified combinations of reported \(\Delta {E}_{{seg}}\), we provide an inclusive range of screening 26 transition metal M-dopants into host Ni catalyst, combined with the 4 C* chain-clustering (\(\Delta {E}_{{rx}{n,}_{4C}}\), Eq. (6)) as a coke probe molecule, a bottleneck deactivation that has been often overlooked in DFT-screening literature20,33. Interestingly, stable candidates with a positive \(\Delta {E}_{{seg}}\) were shown to be less prone to form 4 C* long-chains (i.e., \(\Delta {E}_{{rx}{n,}_{4C}}\ge\) −1.0 eV) compared to other unstable combinations of negative \(\Delta {E}_{{seg}}\) (i.e., \(\Delta {E}_{{rx}{n,}_{4C}}\le\) −1.5 eV) except for Pt and Mn. A recent experimental study by Wang et al.15 indicated that the addition of Zn and Cu enhanced the nickel-based catalyst’s tolerance to coking, consistent with Zn’s and Cu’s lower \(\Delta {E}_{{rx}{n,}_{4C}}\) values (−0.54 eV and −0.88 eV) compared to that for a Ni catalyst (−2.01 eV). While Ir and Rh showed somewhat stable and moderate clustering behavior, these metals were also screened out due to their high costs. Incorporating the M-dopant’s market price at an early stage of the process eases the burden on DFT calculations for unfeasible M-Ni catalysts.

The surface energy of the SAA M-Ni catalysts, \(\gamma\) (see Eq. (5)), an interfacial indicator whose value can be also experimentally measured, corroborates the stability of the 12 M-dopants that overcame the \(\Delta {E}_{{seg}}\) test (see Fig. 2c). In fact, \(\Delta {E}_{{seg}}\) excluded more combinations than those omitted by the \({\gamma }_{M-{Ni}(111)}\le {\gamma }_{{Ni}(111)}\) criterion, eliminating W, Re, and Os. Note that the calculated \({\gamma }_{{Ni}(111)}\) value in this work agrees well with that previously reported by Tran et al.34 (difference of 0.06 J·m−2) testing monometallic facets. Thus, the \({\gamma }_{M-{Ni}(111)}\) evaluation here can be exploited to predict the stability of novel SAA M-Ni(111) alloys upon synthesis. Additionally, comparing our DFT results with modified embedded-atom method (MEAM) simulations and experiments on available combinations in literature reveals that \(\Delta {E}_{{seg}}\) we are able to predict the segregational tendencies of Pd35 and Cu36,37 in a host nickel present in dilute amounts, thus providing strong theoretical evidence of the accuracy of our DFT calculations. The long-term stability of the single-atom dopants for two systems of high (Y-Ni) and low (Pd-Ni) segregation affinities was investigated at 873 K using AIMD (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2). It was found that both single sites eventually stabilize to their initial z-coordinates in the slab model, further validating the predicted stability of the SAA M-Ni(111) catalysts on the top surface.

However, rapid acetic acid dehydrogenation might lead to H*-induced structural segregation effects on the SAA M-Ni catalysts. This has been also tested in this work by computing the 3H*-induced segregation energy, \(\Delta {E}_{3H-{seg}}\) (i.e., 3H* atoms fully occupying the M-dopant 1st neighboring hollow sites) shown in Fig. 2d. While the quantitative affinity of \(\Delta {E}_{3H-{seg}}\) and \(\Delta {E}_{{seg}}\) varies, the conclusions remain consistent regarding whether the ad-atom favors residing on the surface or segregating to bulk occupancy. Therefore, it is fair to say that Sc, Mn, Cu, Zn, Y, Zr, Pd, Ag, Cd, Hf, Pt, and Au are suitable single-site M-dopants with known structural stability and economic feasibility. Accordingly, these SAA M-Ni catalyst combinations advanced to the next phase of the evaluation.

Tuning SAA M-Ni catalysts activity for H2 production from acetic acid dehydrogenation

Previous theoretical studies uncovering the full mechanism of acetic acid decomposition on Pd(111)38 and Ni(111)39 have recognized that dehydrogenation through the hydroxyl functional group is mainly favored on transition metals. DFT-screening work on SAA catalysts has shown that the SAA catalysts’ activity can be described by accessing the first dehydrogenation reaction40. Thus, the acetic acid selective dehydrogenation (DH) route of the \({\rm{O}}-{\rm{H}}\) bond was examined to describe the SAA Ni-based activity. First, DFT computations were performed to systematically inspect the adsorption modes of acetic acid on 11 distinct sites for each M-dopant (Supplementary Fig. 3), resulting in a total of 132 initial adsorption simulations. The adsorption energies for acetic acid on the intrinsic M-Ni SAA surfaces, \({E}_{{ads}{,}_{C{H}_{3}{COOH}}}\) (see Eq. (3)), are revealed in Supplementary Fig. 4. The optimal \({E}_{{ads}{,}_{C{H}_{3}{COOH}}}\) values against the dehydrogenation reaction energy, \(\Delta {E}_{{rxn}}\) (see Eq.(6)), are plotted in Fig. 3 for each M-Ni SAA and Ni. An exothermic reaction (i.e., negative \(\Delta {E}_{{rxn}}\)) is desirable to drive the H-abstraction reaction from the bio-oil towards hydrogen production. Interestingly, introducing the ad-atom enhances the bio-oil adsorption strength but also alters the optimum adsorption conformation of acetic acid. To rationalize this behavior, we accentuate five distinct adsorption modes of the single-atom nearest neighbor sites, highlighted in Fig. 3, via the inserted conformations. Ag, Cu, and Zn provide the most thermodynamically favorable CH₃COOH* dehydrogenation to CH₃COO* + H* (\(\Delta {E}_{{rxn}}\) = −0.46, −0.53, and –0.56 eV, respectively), accompanied by moderately lessened \({E}_{{ads}}\) (~0.16 eV) compared to pristine Ni surface. This favorable reaction is attributed to the ability of the ad-atom to fine-tune the hydroxyl oxygen (-\({O}_{\beta }\)H) surface interactions by adsorbing on the Ni atop and M-Ni bridge sites (configurations shown in green and blue boxes), without strongly increasing the carbonyl (\({O}_{\alpha }\)) interactions with the surface as in the case of Hf-Ni, Zr-Ni, Y-Ni, and Mn-Ni (configurations in pink and yellow). Indeed, the resulting DH conformations reveal the distant (adjacent) \({O}_{\alpha }\) adsorption of the formal (lateral) M-dopants following H*-cleavage (Supplementary Fig. 5). As for the other M-Ni catalysts, provided that acetic acid oxygenated moieties prefer to reside on the nearby single-site adsorption, their effect on acetic acid adsorption or dehydrogenation is within the range of ~0.2 eV. As clearly shown in Fig. 3, and due to the distinct adsorption modes, the single-atom sites surrounded by Ni coinage can break the linear scaling relations (LSRs) for the acetic acid DH reaction. This goes beyond the confined catalytic pinnacle performance stated by Sabatier26 as ameliorating novel SAA with fine-tuned selectivity and reactivity28.

a The relationship between the dehydrogenation reaction energy (\({\Delta E}_{{rxn}{,}_{C{H}_{3}{CO}{O}^{*}+{H}^{*}}}\)) and acetic acid adsorption energy (\({E}_{{ads}{,}_{C{H}_{3}{COOH}}}\)). Horizontal and vertical black lines are set to compare M-Ni modulations with Ni surface. Insets reveal the top view of acetic acid adsorption on the SAA sites and are colored based on the various adsorption modes. SAA in green significantly reduce the \({\Delta E}_{{rxn}{,}_{C{H}_{3}{CO}{O}^{*}+{H}^{*}}}\), while decreasing acetic acid adsorption \({E}_{{ads}{,}_{C{H}_{3}{COOH}}}\) only moderately. Atoms color coding: Ni: Blue, Dopant: yellow, C: gray, H: while, O: red. b comparison of acetic acid reaction energies \((\Delta {E}_{{rxn}})\) for the dehydrogenation through \({O}_{\beta }H\) moiety (\(C{H}_{3}{COO}{H}^{*}\to C{H}_{3}{CO}{O}^{*}+{H}^{*}\)), dehydroxylation \((C{H}_{3}{COO}{H}^{*}\to C{H}_{3}C{O}^{*}+{{OH}}^{*})\), and methyl dehydrogenation (\(C{H}_{3}{COO}{H}^{*}\to C{H}_{2}{CO}{{OH}}^{*}+{H}^{*}\)) on the SAA M-Ni sites. Data are available in Zenodo.

To validate that acetic acid dehydrogenation via -\({O}_{\beta }\)H (\(C{H}_{3}{COO}{H}^{*}\to {C}{H}_{3}{CO}{O}^{*}+{H}^{*}\)) is the most favorable reaction pathway on the SAA M-Ni surfaces, the \(\Delta {E}_{{rxn}}\) of this route is compared to competitive dehydrogenation of the methyl moiety (\(C{H}_{3}{COO}{H}^{*}\to C{H}_{2}{COO}{H}^{*}+{H}^{*}\)) and dehydroxylation (\(C{H}_{3}{COO}{H}^{*}\to C{H}_{3}C{O}^{*}+O{H}^{*}\)) in Fig. 3b. The \(\Delta {E}_{{rxn}}\) reveals the SAA effectiveness in favoring \({O}_{\beta }\)H dehydrogenation with \(\Delta {E}_{{rxn}}\le 0{eV}\) (green bars), opposed to the endothermic dehydroxylation (red bars) and methyl group dehydrogenation (blue bars) routes. Except for the Sc, Y, Pd, Cd, and Hf induced-Ni catalysts, the formation of \(C{H}_{2}{COO}{H}^{*}+{H}^{*}\) species is more favorable than \(C{H}_{3}C{O}^{*}+O{H}^{*}\) on the SAA sites within the two endothermic reactions. The relative \({O}_{\beta }\)H and \({{CH}}_{3}\) dehydrogenations vs. −\({O}_{\beta }\)H dehydroxylation show that Mn, Cu, Zn, Zr, Ag, Pt, and Au present high dehydrogenation selectivity against bare Ni catalysts (Supplementary Fig. 6).

Subsequently, we sought to establish linear scaling relations based on three fundamental reactions in acetic acid catalytic upgrading: hydrogen production, C*-gasification, and water dissociation. For hydrogen, Fig. 4a evinces a volcano-like relationship. A fundamental understanding of why the volcano curve appears is explained below. The initial constructed configurations signaled 2H* at the fcc-hollow nearest neighbor sites relative to the single-atom M-dopant. Meanwhile, upon performing the spin-polarized relaxation, structural variations revealed a preference of 2H* atoms to relocate to the 2nd nearest neighboring hcp-hollow sites for Zn, Y, and Cd M-Ni SAA catalysts (Supplementary Fig. 7). As a result, this has led such SAA M-Ni systems to exhibit less favorable endothermic \(\Delta {E}_{{rxn}}\) values when it came to H2 formation, placing them at the peak of the volcano cliff (\(2{H}_{{fcc}}^{*}\,\to \,2{H}_{{top}}^{*}\)). This cliff of the\(\,2{H}_{{fcc}}^{*}\,\to \,2{H}_{{top}}^{*}\) endothermic reaction energy is only reduced as the attachment of \(2{H}_{{top}}^{*}\) intensifies or weakens, while a desirable tradeoff lies in the intermediate region of low \(\Delta {E}_{{rxn}}\) coupled with sufficient \({E}_{{ads}}\) of \(2{H}_{{top}}^{*}\). We acknowledge that Pd, breaking the surface adsorption-reactivity behavior, is marked as an effective catalyst that meets this criterion. Note that Pt was found to dissociate to the bridge site (see Supplementary Fig. 7) and, thus, was excluded from the H2 adsorption/reaction data points. This observation agrees with a reported study of acetic acid reforming on 1Pt15Ni and 5Pt15Ni catalysts, where the experimental measurements presented poor performance of low H2 yield (20%), even when compared to monometallic Ni catalyst (30%)10. Our calculations not only show that SAA Pt-Ni favors H2 dissociation, but it exhibits unfavorably higher \(\Delta {E}_{rxn}\) in reference to Ni surface (Fig. 3).

a The relationship between 2H*top adsorption energy, \({E}_{{ads}{,}_{{2H}_{{top}}}}\), and H2 production reaction energy. b Effect of temperature on H2 formation (\(2{H}_{{top}}^{*}\to {H}_{2(g)}\)) reaction free energy in the range of 700–1000 K. Lines are guide to the eyes. c Ab initio analysis of hydrogen atomic pair structural transformations at 873 K on, pristine Ni, Pd-Ni, and Cu-Ni surfaces. The tendency towards H2 binding and production agrees well with the \(\Delta {G}_{{des},{{H}}_{2}}\). d Charge density difference of the hydrogen-surface interactions at 0.03 ps, 0.08 ps, and 0.05 ps for Ni, Pd-Ni, and Cu-Ni, respectively. Red and blue clouds represent regions of charge accumulation and depletion, respectively, and the isosurface value is 0.0025 e·Å−3. d C* and O* adsorption energy, \({E}_{{ad}{s,}_{C+O}}\), correlation with CO* formation reaction energy. e H* and OH* adsorption energy, \({E}_{{ad}{s,}_{H+{OH}}}\), correlation with \({H}_{2}{O}^{*}\) dissociation reaction energy. Insets in a, b, e, and f: top and side views of the designated reactions on Pd-Ni SAA surface. Color coding; H (white), Ni (blue), Pd (purple), and Cu (brown). Data are available in Zenodo.

While Pd-Ni is able to escape the volcano trend and provide the lowest endothermic reaction energy of the \(2{H}_{{fcc}}^{*}\,\to \,2{H}_{{top}}^{*}\) step compared to the other SAA M-Ni surfaces (Fig. 4a), the effect of reaction temperature reveals Cu-Ni to be most effective in terms of lowering the H2 desorption free reaction energy (\(\Delta {G}_{{des},{H}_{2}}\)) (i.e., ~0.24 eV compared to monometallic Ni surface at 873 K) (Fig. 4b). Yet, the results presented so far are based on calculated static energies, while the dynamic nature of the adsorbates might entail intermediates that are crucial to the catalytic performance, especially at the reaction condition. We have therefore implemented AIMD simulations at 873 K to verify the predicted catalytic activity performance towards H2 production for the doped Pd-Ni(111) and Cu-Ni(111), and un-doped Ni(111) catalyst surfaces. Snapshots from the AIMD simulation shown in Fig. 4c reveal that H2 preferably dissociates on the Ni(111) and Pd-Ni(111) surfaces, followed by surface diffusion of the H* intermediate species for a 5 ps time interval (Fig. 4c). In contrast, the Cu atomic site promoted the \(2{H}_{{top}}^{*}\) desorption to H2 molecule, enabling enhanced catalytic activity for H2 production (\(2{H}_{{top}}^{*}\to \,{H}_{2(g)}\)). These results are in correspondence with the lower \({E}_{{ads}}\) of \(2{H}_{{top}}^{*}\) on Cu-Ni(111) (i.e., −0.03 eV) relative to Pd-Ni(111) and Ni(111) with \({E}_{{ads}}\) of −0.29 eV and −0.61 eV, respectively (Fig. 4a).

To better explain these results, the charge density difference plots in Fig. 4d reveal the distinct electronic and structural properties imparted by the two dopants compared to pure Ni(111). Interestingly, both Ni(111) and Pd-Ni(111) captivate strong regions of charge depletion surrounding the 2H* atoms, consequently elucidating their dissociative behavior on both surfaces. Conversely, the Cu single-site charge depletion region is significantly narrowed (Fig. 4d, last row). The absence of such electron deficiency on the single-site alloy gives rise to repealing the H* atoms, thereby facilitating H2 desorption process compared to Ni and Pd-Ni(111) (Fig. 4d). This Cu-Ni was also found to perform the best for acetic acid dehydrogenation from 700 K to 950 K (Supplementary Fig. 8). Based on the effect of temperature on these two most fundamental reactions of bio-oil upgrading to hydrogen, Cu-Ni is presented as an effective single-atom site with prevailing dehydrogenation, followed by promoting H2 formation and desorption from the M-top site at high temperatures.

Turning to coke gasification (\({C}^{*}+{O}^{*}\to {{CO}}^{*}\)), shown in Fig. 4e, CO* formation reaction from O* and C* was found to correlate with the elemental O* and C* adsorption energies, \({E}_{{ad}{s,}_{C+O}}\), with R2 = 0.98, MAE = 0.07 eV, and RMSE = 0.09 eV, being comparable or lower than previous DFT-screening29,33,41. The reason behind the model’s accuracy (i.e., low MAE and RMSE) is anticipated to derive from our decision to exclude unstable SAA combinations before examining such activity-related properties, signaling the importance of a hierarchical approach. It is not surprising that these two descriptors (\({E}_{{ad}{s,}_{C+O}}\) and \(\Delta {E}_{{rxn},{CO}}\)) followed a descending monotonic relation, indicating facile gasification (more exothermic \(\Delta {E}_{{rxn}}\)) with lowering the binding strength of C* and O* reactants.

The dissociation of H2O on the SAA surfaces was also studied to factor the steam reforming-assessed H2 production (Fig. 4f). Exploring the linear 2-descriptor space shows that highly exothermic dissociation (\(\Delta {E}_{{rxn}}\) < −0.5 eV) comes at the cost of strong binding of the OH* and H* species (\({E}_{{ad}{s}_{H+{OH}}}\) < −2.3 eV), thereby giving rise to surface poisoning and/or hampering subsequent H2 formation. Whereas the lowest \({E}_{{ad}{s}_{H+{OH}}}\) binding is observed for SAA catalysts with reduced exothermic \(\Delta {E}_{{rxn}}\) (i.e., Cd, Ag, Zn, Au, and Pt). In between the two extremes, Cu was found to provide comparable exothermic \(\Delta {E}_{{rxn}}\) to Ni (difference of 0.07 eV) with achieving 0.19 eV lower adsorption strength of the reforming intermediates, thereby reducing the poisoning effect on the SAA surface. If we were to recommend suitable M-Ni combinations that simultaneously balance crucial design aspects of (i) H2 production activity, (ii) coke-resistivity, and (iii) steam reforming-assessed process, this would be Cu-Ni, as it facilitates a decrease in the \(2{H}_{{top}}^{*}\to {H}_{2(g)}\) desorption, lessens the \({E}_{{ads}{,}_{{2H}_{{top}}}}\) binding, provides highly exothermic \(C{O}^{*}\) gasification, and reduces \({E}_{{ad}{s}_{H+{OH}}}\) adsorption strength with exothermic H2O dissociation. In addition to Cu-Ni, we acknowledge that Pd-Ni achieved the best in terms of improving the \(2{H}_{{hcp}}^{*}\to 2{H}_{{atop}}^{*}\) endothermicity (Fig. 4a). Hence, to assess the theory-guided design of more effective SAA Ni-based catalysts, the exploration of trimetallic SAA Ni-based reactive-surface structures has been explored.

Trimetallic single-atom alloy catalysts

Studying SAA trimetallic catalysts offers advantages over bimetallic SAA counterparts due to the presence of synergistic interactions among multiple active sites and is an active area of research in catalysis. The trimetallic combinations studied herein were built from the stable and economically viable 12 bimetallic catalysts that demonstrated positive segregation and anti-aggregation into host Ni surface, with market prices less than 1500$·kg−1. The segregation energy under the effect of co-dopants was further assessed (Fig. 5a). 66 tested SAA M1-M2-Ni trimetallic candidates (i.e., M1 and M2 represent 1st and 2nd metal co-dopants) were found to segregate to the surface under vacuum (\(\Delta {E}_{{seg}} \, > \, 0{eV}\)), while 7 M1-M2-Ni SAA systems (shown in red in Fig. 5a) were shifted to anti-surface segregation under H-induced condition with \(\Delta {E}_{{seg}}\) of negative or approaching \(\cong\) 0 eV (i.e., Mn-Cu, Mn-Pd, Mn-Pt, Cu-Pd, Cu-Pt, Pd-Pt, and Pt-Au). Furthermore, our calculations show that the other trimetallic site combinations present a strong tendency to occupy the uppermost layer in the presence or absence of an H*-induced environment. Yet, it was also important to determine whether a more stable atomic arrangement exists when substituting M1 and M2 compared to alternating M1 to M2 bulk or surface sites occupancy, as shown in Fig. 5b. Specifically, testing this for the Zn-Au-Ni trimetallic ensemble, the most positive \(\Delta {E}_{{seg}}\) was found for both M1 and M2 subsurface-to-surface segregation (Fig. 5c), thereby reinforcing the \(\Delta {E}_{{seg}}\) in Fig. 5a.

a segregation energy (\(\Delta {E}_{{seg}}\)) in eV calculated for trimetallic M1-M2-Ni combinations in a vacuum and under the effect of H*-induced environment. Insets: top and side views of the bulk to surface segregation for the vacuum (blue borders) and H*-induced (yellow borders) systems. b side view of different atomic coordination of M1-M2-Ni tested for the Zn-Au-Ni catalyst and their c calculated \(\Delta {E}_{{seg}}\). d difference in the 1st nearest neighbor site (NNS) and 2nd NNS surface energy (\({\gamma }_{{1}^{{st}}{NNS}}-{\gamma }_{{2}^{{nd}}{NNS}}\)) for the M1-M2-Ni combinations. \({\gamma }_{{1}^{{st}}{NNS}}-{\gamma }_{{2}^{{nd}}{NNS}}\le 0{\rm{J}}.{{\rm{m}}}^{-2}\) denoted by green triangles indicate that the 1st NNS is relatively more stable than the 2nd NNS ensemble. Nearly stable 1st NNS are marked with yellow circles and hold \({\gamma }_{{1}^{{st}}{NNS}}-{\gamma }_{{2}^{{nd}}{NNS}}\) in the range of \(0-0.025{\rm{J}}.{{\rm{m}}}^{-2}\), while structures with \( > 0.025\,{\rm{J}}.{{\rm{m}}}^{-2}\) signals that 2nd NNS is thermodynamically more favorable than 1st NNS indicated with blue diamonds. Insets reveal the top view of the 1st NNS and 2nd NNS trimetallic surfaces. Data are available in Zenodo.

In addition to the dopant surface segregation, M1-M2 dimers might occupy adjacent sites of 1st nearest neighbor sites (NNS), or preferably disperse in ensembles of M1-Ni-M2, herein denoted as 2nd NNS (see insets in Fig. 5d). To further evaluate this tendency, the surface energy \((\gamma )\) difference of the alternating structures 1st NNS and 2nd NNS (\({\gamma }_{{1}^{{st}}{NNS}}-{\gamma }_{{2}^{{nd}}{NNS}}\)) was assessed to evaluate their relative thermodynamic stability. By adding this descriptor into play, trimetallic catalysts exhibiting negative surface energies difference (\({\gamma }_{{1}^{{st}}{NNS}}-{\gamma }_{{2}^{{nd}}{NNS}}\,\le 0\,{\rm{J\cdot }}{{\rm{m}}}^{-2}\)) are less prone to undergo surface restructuring to 2nd NNS. In between, surfaces with somewhat positive \({\gamma }_{{1}^{{st}}{NNS}}-{\gamma }_{{2}^{{nd}}{NNS}}\le 0.025\,{\rm{J}}.{{\rm{m}}}^{-2}\) are marked in the nearly stable 1st NNS, while those with \({\gamma }_{{1}^{{st}}{NNS}}-{\gamma }_{{2}^{{nd}}{NNS}} \, > \, 0.025\,{\rm{J}}.{{\rm{m}}}^{-2}\) are anticipated to encounter surface restructuring in 2nd NNS.

The screening results mark 37 candidates to have energetically stable 1st NNS sites pertinent to 2nd NNS with M1-Ni-M2 configurations, followed by 18 “Nearly stable 1st NNS” SAA catalysts, and only 11 favoring to reside in 2nd NNS configuration. Trimetallic SAA with Pd-M2-Ni and Pt-M2-Ni dopants were mostly found to prefer existing as stable 1st NNS structures, while specific combinations of Cd, Y, and Zr tend to lower the \({\gamma }_{{2}^{{nd}}{NNS}}\), promoting isolated 2nd NNS M1-Ni-M2 sites. Thus, the inclusion of the above stability-selection descriptors of \(\Delta {E}_{{seg}}\) and \({\gamma }_{{1}^{{st}}{NNS}}-{\gamma }_{{2}^{{nd}}{NNS}}\) aids in predicting the formation of well-defined M1-M2-Ni sites on the uppermost layer of the host Ni catalyst. After screening out unfeasible anti-segregation and trimetallic configurations with a tendency to undergo reconstruction to 2nd NNS, the \(\gamma\) values for the stable and nearly stable 1st NNS ensembles trimetallic SAA M1-M2-Ni catalysts are compared next.

Figure 6a depicts the \(\gamma\) distribution of the SAA M1-M2-Ni trimetallic candidates compared against the pristine Ni surface. The most critical observation is that these SAA surface energy values are lowered compared to monometallic Ni (\({\gamma }_{{Ni}\left(111\right)}\) = 1.86 J·m−2). Thus, experimentally, the presence of such active-site modulations in dilute amounts can improve the catalytic stability, resulting from their synergistic interactions. Particularly, observations reveal that trimetallic combinations incorporating Y-M2-Ni and Sc-M2-Ni exhibit the highest stability among co-dopants, having \(\gamma\) in between 1.59 \(-\) 1.70 J·m−2. This is then followed by trimetallic Ni-based SAA surfaces comprising Hf-M2-Ni (\(\gamma\) = 1.64 \(-\) 1.71 J·m−2), Zr-M2-Ni (\(\gamma\) = 1.64 \(-\) 1.72 J·m−2), and Zn-M2-Ni (\(\gamma\) = 1.61 \(-\) 1.78 J·m−2). This precise tuning of the trimetallic catalysts’ stability progressively decreases with the incorporation of other co-dopants, having the least stable co-dopant systems, characterized by \(\gamma \ge\) 1.80 J.m-2, namely, Ag-Mn, Ag-Cu, Ag-Pd, Cd-Cu, and Au-Cu doped into the pristine Ni surface.

a Surface energy (\(\gamma\)) in J·m−2, b hydrogen adsorption energy, \({E}_{{ad}{s,}_{H}}\), and c carbon adsorption energy, \({E}_{{ad}{s,}_{C}}\) (in eV) on the studied trimetallic SAA M1-M2-Ni catalysts. The abscissa and ordinate denote M1 and M2 in the close-packed M1-M2-Ni(111) surfaces. Ni(111) values for the designated quantities are displayed on the diagonal. Color intensities are specified in the scale bar distinctively for each property. Gray squares indicate excluded combinations from the stability assessment (see Fig. 5). Data are available in Zenodo.

Building on the stability of the SAA M1-M2-Ni catalysts, we next explored their H2 activity and coking-tolerance by assessing the adsorption strengths of elemental H* and C* atoms (\({E}_{{ad}{s,}_{C}}\) and \({E}_{{ad}{s,}_{H}}\)) as key intermediates linked to the catalytic modulation of the SAA trimetallic sites (Fig. 6b, c). As previously mentioned, a weaker H* binding (less negative \({E}_{{ad}{s,}_{H}}\)) entails facile H* desorption to improve H2 generation reaction. At the same time, the ramifications of weakening the C*-M1-M2-Ni permit novel anti-coking surfaces. Applying the \({E}_{{ad}{s,}_{H}}\) and \({E}_{{ad}{s,}_{C}}\) criteria based on the generated trimetallic data (details in the “Methods” section), we discovered six (6) promising trimetallic M1-M1-Ni catalysts: Ag-Sc-Ni, Au-Sc-Ni, Au-Zn-Ni, Au-Zr-Ni, Au-Pd-Ni, and Au-Hf-Ni. They all achieve high H2 formation activity, accompanied with improved coke-resistant ability (i.e., \(\le 0.7{eV}\) diminished \({E}_{{ad}{s,}_{C}}\) compared to pristine Ni(111)). Interestingly, those M1-M2-Ni modulations are the ones exhibiting high stability (\(\gamma\) = 1.51 \(-\) 1.76 J·m−2) and are, therefore, viable as stable SAA trimetallic catalysts that are anticipated to favor H2 production with ameliorated coking susceptibility. On the contrary, note that not all trimetallic combinations prove to be successful: Mn-Sc-Ni, Y-Mn-Ni, Zr-Mn-Ni, and Hf-Mn-Ni are prone to severe coke accumulation and deactivation, despite being marked as stable, discriminating such catalysts from future experimental synthesis and characterization studies.

We summarize the most promising trimetallic and bimetallic single-atom alloys that emerge from the screening in Fig. 7. Comparing their surface stability, H* activity, and coke resistance, the trimetallic catalysts outperformed all previously reported bimetallic SAA catalysts, showing reduced surface energies, optimum H* binding, and considerably diminished C* adsorption, respectively (Fig. 7a–c). Particularly, the introduction of Au-Zn coordination into a Ni host imparted remarkably diminished carbon-surface interactions (\({E}_{{{ads},}_{{C}}}=\) −4.88 eV) compared to bimetallic (\({E}_{{{ads},}_{{C}}}=\) −6.72 eV to −6.84 eV) in conjugation with favorable H* adsorption (\({E}_{{{ads},}_{{H}}}=\) −0.42 eV). This is expected to promote H* release towards H2 production compared to bimetallic SAA catalysts (\({E}_{{{ads},}_{{H}}}=\) −0.57 eV to −0.67 eV). Nevertheless, all these trimetallic SAA catalysts are found to be effective in H2 production with minimal propensity for coke accumulation.

a surface energy, \(\gamma\) (J·m-2), b hydrogen adsorption energy, \({E}_{{{ads},}_{H}}\), and c carbon adsorption energy, \({E}_{{{ads},}_{C}}\). Inserted figures denote the optimized configurations. Color coding: Ni (Blue), M1 (Yellow), M2 (Pink), H (white), C (gray). Insets show the active sites and adsorbates simulated conformations for each system.

Discussion

The results of this work allow the identification of novel bi- and trimetallic SAA Ni(111)-based catalysts for the conversion of acetic acid into hydrogen using a systematic periodic spin-polarized DFT analysis framework. First, we rigorously assessed the atomic ensemble stability by four DFT-descriptors (\(\Delta {E}_{{agg}}\), \(\Delta {E}_{{seg}}\), \({3H}^{*}-\Delta {E}_{{seg}}\), and \(\gamma\)), in tandem with their thermodynamic tendency for carbon-chain clustering (\(\Delta {E}_{{rx}{n,}_{4C}}\)) and economic viability ($·Kg-1). Candidate catalysts that involved poor dispersive and segregation behaviors, high costs, or strong exothermic C*-clustering reactions were discarded. Single-atom sites that were predicted to remain stable not only evoked variations in the binding strength of acetic acid but also imposed geometric variations of adsorption modes. This elucidated facile dehydrogenation of SAA M-Ni that balanced \(-{O}_{\beta }\)H and \(-{O}_{\alpha }\) surface interactions (\(-{O}_{\beta }H\): either fcc, hcp, or bridge of M-Ni; \(-{O}_{\alpha }\): top of Ni). Moreover, coupling this behavior with the adsorption and reaction energies of H2 production and C*-gasification reaction provided a benchmark for evaluating the H2 activity trend and SAA catalyst regeneration ability. This identified Cu-Ni(111) and Pd-Ni(111) as effective SAA catalysts for bio-oil upgrading to H2. It is notable that Cu-Ni(111) bimetallic single-atom alloy offers enhanced dehydrogenation, H2 production, C*-gasification, and analogous exothermic H2O dissociation compared to conventional Ni catalyst. Whereas Pd-Ni(111) was found to break the volcano-shaped plot for the endothermic \(2{H}_{{fcc}}^{*}\to 2{H}_{{top}}^{*}\) step with moderate \(2{H}_{{top}}^{*}\) binding, offering the potential to produce hydrogen on the Pd single-site. These Ni-based single sites have not yet been considered for acetic acid reforming to hydrogen in literature. In the modeling work of Xu et al.35, simulating Pd-Ni showed favorable segregation and anti-aggregation behavior of Pd single-atoms in Ni host nanoparticles. Moreover, the synthesis of Pd1Ni as an SAA catalyst was also achieved by Lu’s team42 using quasi-atomic dispersion of Pd on Nickel nanoparticles. Similar findings were predicted for Cu-Ni-based alloy from the atomistic analysis calculations of Watanabe et al.36.

This successful protocol for rationalizing the selection of the catalysts concluded with modeling trimetallic SAA candidates, identifying combinations of six potentially promising trimetallic SAA Ni-based catalysts, crosschecking the key pillars of the 1st nearest neighbor site M1-M2 stability under vacuum and H*-induced conditions, H2 activity, affordability, and regeneration ability. While DFT-based high-throughput screening protocols have been extensively developed and applied in literature20,23, a screening protocol of acetic acid SAA catalytic dehydrogenation to H2 has not yet been employed before this work. This is significantly important for biomass valorization research43,44, as it aids in selecting suitable catalytic active sites for bio-oil to be converted to H2 with high stability, anti-coking, and a high activity to H2 generation. To facilitate linking the findings from this work to experimental synthesis, Fig. 8 provides an overview of the reported Ni-based combinations as SAA, bimetallic, or trimetallic catalysts with higher ratios than single-atom alloys. Although several synthetic systems have been developed for bimetallic and trimetallic Ni-based alloy catalysts (Fig. 8 blue segment), the ratio-controlled synthesis of Ni-based single-atom alloys is limited to a few combinations (Fig. 8 green segment). Moreover, most of the promising trimetallic combinations comprise either Au or Pd sites, being combined with other M2-dopants. These two elements have been already explored experimentally as bimetallic Ni-based alloys (Blue Segment of Fig. 8 and Supplementary Table 3). With this theoretical design screening, the established scaling relations and design rules can be exploited as a guide for experimental work seeking to explore modulated Ni-based bimetallic and trimetallic SAA alloys, unleashing stable and high-performing sites for improved bio-oil steam reforming catalytic upgrading. It is expected that the adsorption and activity insights captured from this work would motivate screening alternative bio-oil functionalities and non-noble metal host alloys, serving as a theoretical design perspective to accelerate efficient surface catalysis of bio-oil upgrading to biohydrogen.

The reported synthesis corresponding to the SAA, bimetallic, and trimetallic catalysts in the green and blue cycles can be found in Supplementary Table 3.

Methods

Computational details

Periodic spin-polarized density functional theory (DFT) calculations of reaction energetics were performed using the plane-wave implementation and ultrasoft pseudopotentials supplied by the open-source QUANTUM ESPRESSO version 7.245,46. We applied the Perdew−Burke−Ernzerof (PBE) functional47, including the (DFT-D3) empirical correction48,49, which provides a reasonable description of the long-rangevan der Waals interactions while maintaining an accurate estimation of chemisorption energies50. We used a 400 Ry kinetic energy cutoff for the charge density and a wavefunction cutoff of 50 Ry. The electronic convergence threshold and ionic minimization forces were set to \({10}^{-6}\) and \({10}^{-3}\), respectively. The starting magnetization of all atom types was set based on the Quantum ESPRESSO input generator51. Moreover, it has been previously verified by Prandini et al.52 that the convergence is not substantially altered by varying the starting magnetization value, which we also reveal in our work (see Supplementary Fig. 9).

Computed properties

A 9 × 9 × 9 k-mesh was used for optimizing the face-centered cubic (fcc) Ni bulk lattice until forces converged to less than 0.05 eV·Å−1. The lattice constant was found to be in close agreement with the experimental value, within a 0.1% difference53. Then, the optimized unit cell was used to construct 3 × 3 supercells of Ni(111), Ni(110), and Ni(100) with four atomic layers and 15 Å vacuum separation. The top two layers were allowed to relax, while the bottom two layers were fixed to their bulk position. It is recognized in the literature that the surface energy (\(\gamma\)) of fcc metals follows a decreasing order of \({\gamma }_{({hkl})} \, > \, {\gamma }_{(100)} \, > \, {\gamma }_{\left(111\right)}\left(h \, > \, k \, \ge \, l\right)\)54. This was tested here, producing \(\gamma\) values of Ni(111), Ni(110), and Ni(100) of 1.86 J·m−2, 2.50 J·m−2 and 2.71 J·m−2, respectively. These results corroborate the expected ordering and are in close agreement with the \(\gamma\) database34, as validated against experimental work55. As a result, the Ni(111) slab was selected to construct the M-Ni(111) single-atom alloy catalysts (i.e., M: dopant transition metal).

The aggregation energy (\(\Delta {E}_{{agg}}\))56,57,58 and segregation energy (\(\Delta {E}_{{seg}}\))32,56 descriptors were calculated to evaluate the SAA surface occupancy and dispersive tendency, respectively, as follows:

where \({E}_{n-{mer}}\) denotes the energy of Ni(111) with a dimer or a trimer aggregate ensemble of M dopant (i.e., M(n)-Ni(111); where n = 2 or 3), and \({E}_{{Ni}(111)}\) represents the energy of the host monometallic Ni(111) surface. \({E}_{{SAA}}\) and \({E}_{{NSA}}\) are the DFT-calculated energies of the M-Ni(111) slab in which the dopant (M) replaces one Ni atom in the top layer (SAA) and in the 3rd layer demonstrating a near-surface alloy (NSA), respectively. Note that for the doped surfaces in the 3rd layer, the top three layers were allowed to relax, while the last 4th layer was kept frozen (see optimized configurations coordinates provided in the Supplementary Data 1).

The adsorption energy of adsorbate \(i\), \({E}_{{ad}{s,}_{i}}\), (i.e., acetic acid (\(C{H}_{3}{COOH}\)), H, \({H}_{2}\), H2O, O, OH, CO, etc.) is defined as23:

where \({E}_{{surface}+{adsorbat}{e,}_{i}}\) and \({E}_{{surface}}\) are the total energies of the slab with and without the adsorbate \(i\), respectively. \({E}_{{adsorbat}{e}_{i}}\) refers to the energy of the adsorbate \(i\) in the gas phase. Moreover, the 3H*-induced segregation energy, \(\Delta {E}_{3{H}^{*}-{seg}}\) was evaluated as:

\({E}_{{ads},3{H}^{*}-{Ni}(111)}\) and \({E}_{{ads},3{H}^{*}-{SAA}}\) are the adsorption energies of the \({3H}^{*}\) adsorbed on the pure host Ni(111) and Ni(111) SAA surfaces, respectively. Finally, the surface energy (\(\gamma\)) of the SAA bimetallic (M-Ni) and trimetallic (M1-M2-Ni) catalysts was assessed as34:

where \({E}_{{M}_{1},{bulk}}\), \({E}_{{M}_{2},{bulk}}\), and \({E}_{{Ni},{bulk}}\) are the energy per atom of the bulk unit cell of M1, M2, and Ni atoms. \({n}_{{M}_{1},{bulk}}\), \({n}_{{M}_{2},{bulk}}\), and \({n}_{{Ni},{bulk}}\) are the number of M1, M2, and Ni atoms in the SAA surface model, respectively. \({A}_{{SAA}}\) denotes the surface area of the SAA slab structure multiplied by a factor of two to account for the two exposed surfaces in the simulated configuration.

For an analysis of the reaction activity, the reaction energy (\(\Delta {E}_{{rxn},i}\)) was evaluated as:

where \({E}_{{ad}{s,}_{{FS}}}\) and\(\,{E}_{{ad}{s,}_{{IS}}}\) denote the adsorption energies of the initial and final adsorbed states, respectively (calculated from Eq. (3)) for a given reaction step59.

Finally, ab initio molecular dynamics simulations in the canonical ensemble were performed to corroborate conclusions drawn from the \({E}_{{ad}{s,}_{i}}\) and \(\Delta {E}_{{rx}{n,}_{i}}\) descriptors. Simulations were run for 5 ps using a 1 fs timestep as a reasonable timeframe to capture the H2 reaction on Ni(111) and Y-Ni(111)60. The temperature was controlled at 873 K using the stochastic-velocity rescaling method61. In terms of modeling the trimetallic SAA surfaces adsorptive properties, the 3-fold fcc-hollow33 and 3-fold hcp-hollow sites62,63 in the 1st nearest neighboring position closest to the M1-M2 dopants were selected for the location of the H* and C* atoms, respectively (see trimetallic conformations in Fig. 7b, c). The increase in the supercell size from 3\(\times\)3 to 4\(\times\)4, including the 4th layer full coordinates relaxation, did not alter the surface energy, hydrogen, and carbon adsorption energies for a randomly selected SAA trimetallic combination of Ag-Cu-Ni (see Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). Hence, the 3\(\times\)3 supercells with upper-two layers relaxation were found sufficient to capture the simulation properties regardless of the periodic boundary conditions. The effect of surface coverage (θ), corresponding to 1/16 and 1/49 monolayer (ML) of adsorbate on the 3 × 3 and 4 × 4 supercells (where ML is the number of adsorbates/metal surface atoms) did not vary the adsorption energy values to a great extent (\({E}_{{ads}}\) of −0.79 eV and −0.83 eV for acetic acid on the 3 × 3 and 4 × 4 supercells of Cu-Ni, respectively). Moreover, the 1/16 ML coverage of acetic acid simulated in this work matches the experimental coverage of acetic acid on transition metals64.

SAA bimetallic M1-Ni(111) and trimetallic M1-M2-Ni(111) doping might deform the local bond length values on the uppermost layer of the Ni-based alloy. These values are provided in Supplementary Fig. 10. Subsequent to the dopants substitution, the M1-Ni(111) and M1-M2-Ni(111) bond lengths became distended by up to 9% and 27%, respectively, in which Y-Ni comprised the largest bond length among the bimetallic, while Y-Sc-Ni, Y-Zr-Ni, and Y-Hf-Ni trimetallic M1-M2-Ni surfaces exhibited the largest deviation among the trimetallic dopants. Note that these combinations of trimetallic actives-sites providing the largest deviations have been excluded in our comprehensive surface stability assessment, as they are not stable (see Fig. 5d). Interestingly, comparing the trend with the 3H*-induced segregation energies, we found that the pattern of M-Ni bond length is consistent with the segregation energy variation for the bimetallic Ni-based catalysts (R2 = 0.91, Supplementary Fig. 11). This can be attributed to the variation of the dopant’s atomic radius that affects the alloy’s structural properties.

Finally, screening the activity of the M1-M2-Ni trimetallic candidates from the \({E}_{{ad}{s,}_{H}}\) and \({E}_{{ad}{s,}_{C}}\) descriptors was based on the range of data attained in this work. The conditions for both properties were set to simultaneously achieve \({E}_{{ad}{s,}_{H}} > -\)0.5 eV and \({E}_{{ad}{s,}_{C}} > -\)6.0 eV, being 0.05 eV and 0.5 eV less than the median value attained for both descriptors, respectively.

Data availability

All data of this study are available in the Zenodo open repository at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14179524.

References

Ochoa, A., Bilbao, J., Gayubo, A. G. & Castaño, P. Coke formation and deactivation during catalytic reforming of biomass and waste pyrolysis products: a review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 119, 109600 (2020).

Falcone, P. M., Hiete, M. & Sapio, A. Hydrogen economy and sustainable development goals: review and policy insights. Curr. Opin. Green. Sustain. Chem. 31, 100506 (2021).

Ertl, G., Knözinger, H., Schüth F., Weitkamp, J. Handbook of Heterogeneous Catalysis. (Wiley, 2008).

Li, D., Li, X. & Gong, J. Catalytic reforming of oxygenates: state of the art and future prospects. Chem. Rev. 116, 11529–11653 (2016).

Carpenter, D., Westover, T. L., Czernik, S. & Jablonski, W. Biomass feedstocks for renewable fuel production: a review of the impacts of feedstock and pretreatment on the yield and product distribution of fast pyrolysis bio-oils and vapors. Green. Chem. 16, 384–406 (2014).

Chan, Y. H. et al. Fractionation and extraction of bio-oil for production of greener fuel and value-added chemicals: recent advances and future prospects. Chem. Eng. J. 397, 125406 (2020).

Ding, C. et al. Interface of Ni-MgCr2O4 spinel promotes the autothermal reforming of acetic acid through accelerated oxidation of carbon-containing intermediate species. ACS Catal. 13, 4560–4574 (2023).

AlAreeqi, S., Bahamon, D., Polychronopoulou, K. & Vega, L. F. Understanding the role of Ni-based single-atom alloys on the selective hydrodeoxygenation of bio-oils. Fuel Process. Technol. 253, 108001 (2024).

Takanabe, K., Aika, K. I., Seshan, K. & Lefferts, L. Sustainable hydrogen from bio-oil—Steam reforming of acetic acid as a model oxygenate. J. Catal. 227, 101–108 (2004).

Souza, I. C. A., Manfro, R. L. & Souza, M. M. V. M. Hydrogen production from steam reforming of acetic acid over Pt–Ni bimetallic catalysts supported on ZrO2. Biomass. Bioenergy 156, 106317 (2022).

Li, X. et al. Mechanistic study of bio-oil catalytic steam reforming for hydrogen production: Acetic acid decomposition. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 43, 13212–13224 (2018).

Lemonidou, A. A., Vagia, E. C. & Lercher, J. A. Acetic acid reforming over Rh supported on La2O 3/CeO2-ZrO2: catalytic performance and reaction pathway analysis. ACS Catal. 3, 1919–1928 (2013).

Basagiannis, A. C. & Verykios, X. E. Catalytic steam reforming of acetic acid for hydrogen production. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 32, 3343–3355 (2007).

Megía, P. J. et al. Influence of Rh addition to transition metal-based catalysts in the oxidative steam reforming of acetic acid. Catal. Today 429, 114479 (2024).

Wang, Y. et al. Modification of nickel-based catalyst with transition metals to tailor reaction intermediates and property of coke in steam reforming of acetic acid. Fuel 318, 123698 (2022).

Lazaridou, A. et al. Recognizing the best catalyst for a reaction. Nat. Rev. Chem. 7, 287–295 (2023).

Chung, H. et al. Single atom substitution alters the polymorphic transition mechanism in organic electronic crystals. Chem. Mater. 26, 18 (2019).

Abdolshah, M., Shilton, A., Rana, S., Gupta, S. & Venkatesh, S. Multi-objective Bayesian optimisation with preferences over objectives. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 32, 464–466 (2019).

Priyadarshini, M. S. et al. PAL 2.0: a physics-driven Bayesian optimization framework for material discovery. Mater. Horiz. 11, 781–791 (2024).

Yeo, B. C. et al. High-throughput computational-experimental screening protocol for the discovery of bimetallic catalysts. npj Comput. Mater. 7, 1–10 (2021).

Tang, M. T., Peng, H., Lamoureux, P. S., Bajdich, M. & Abild-Pedersen, F. From electricity to fuels: descriptors for C1 selectivity in electrochemical CO2 reduction. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 279, 119384 (2020).

Ringe, S. The importance of a charge transfer descriptor for screening potential CO2 reduction electrocatalysts. Nat. Commun. 14, 1–14 (2023).

Li, Y., Bahamon, D., Sinnokrot, M. & Vega, L. F. Computational screening of transition metal-doped CdS for photocatalytic hydrogen production. npj Comput. Mater. 8, 1–9 (2022).

Darby, M. T., Réocreux, R., Sykes, E. C. H., Michaelides, A. & Stamatakis, M. Elucidating the stability and reactivity of surface intermediates on single-atom alloy catalysts. ACS Catal. 8, 5038–5050 (2018).

Logadottir, A. et al. The Brønsted–Evans–Polanyi relation and the volcano plot for ammonia synthesis over transition metal catalysts. J. Catal. 197, 229–231 (2001).

Sabatier, P. Hydrogénations et déshydrogénations par catalyse. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 44, 1984–2001 (1911).

Nørskov, J. K., Bligaard, T., Rossmeisl, J. & Christensen, C. H. Towards the computational design of solid catalysts. Nat. Chem. 1, 37–46 (2009).

Pérez-Ramírez, J. & López, N. Strategies to break linear scaling relationships. Nat. Catal. 2, 971–976 (2019).

Yu, Y. X. et al. High-throughput screening of alloy catalysts for dry methane reforming. ACS Catal. 11, 8881–8894 (2021).

Wang, Y. Y. et al. Facile N≡N bond cleavage by anionic Trimetallic clusters V3−xTaxC4− (x=0–3): A DFT Study. ChemPhysChem 23, e202100771 (2022).

Wang, L., Ore, R. M., Jayamaha, P. K., Wu, Z. P. & Zhong, C. J. Density functional theory based computational investigations on the stability of highly active trimetallic PtPdCu nanoalloys for electrochemical oxygen reduction. Faraday Discuss. 242, 429–442 (2023).

Zhou, J., An, W., Wang, Z. & Jia, X. Hydrodeoxygenation of phenol over Ni-based bimetallic single-atom surface alloys: mechanism, kinetics and descriptor. Catal. Sci. Technol. 9, 4314–4326 (2019).

Han, Z. K. et al. Single-atom alloy catalysts designed by first-principles calculations and artificial intelligence. Nat. Commun. 12, 1–9 (2021).

Tran, R. et al. Surface energies of elemental crystals. Sci. Data 3, 1–13 (2016).

Xu, Y., Wang, G., Qian, P. & Su, Y. Element segregation and thermal stability of Ni–Pd nanoparticles. J. Mater. Sci. 57, 7384–7399 (2022).

Watanabe, K., Hashiba, M. & Yamashina, T. A quantitative analysis of surface segregation and in-depth profile of copper-nickel alloys. Surf. Sci. 61, 483–490 (1976).

Fischer, F., Schmitz, G. & Eich, S. M. A systematic study of grain boundary segregation and grain boundary formation energy using a new copper–nickel embedded-atom potential. Acta Mater. 176, 220–231 (2019).

Chukwu, K. C. & Árnadóttir, L. Density functional theory study of decarboxylation and decarbonylation of acetic acid on Pd(111). J. Phys. Chem. C. 124, 13082–13093 (2020).

Shi, H. et al. Theoretical investigation of the reactivity of flat Ni (111) and stepped Ni (211) surfaces for acetic acid hydrogenation to ethanol. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 46, 15454–15470 (2021).

Sun, G. et al. Breaking the scaling relationship via thermally stable Pt/Cu single atom alloys for catalytic dehydrogenation. Nat. Commun. 9, 1–9 (2018).

Mamun, O., Winther, K. T., Boes, J. R. & Bligaard, T. A Bayesian framework for adsorption energy prediction on bimetallic alloy catalysts. npj Comput. Mater. 6, 1–11 (2020).

Wang, H. et al. Quasi Pd1Ni single-atom surface alloy catalyst enables hydrogenation of nitriles to secondary amines. Nat. Commun. 10, 1–9 (2019).

Wrasman, C. J. et al. Catalytic pyrolysis as a platform technology for supporting the circular carbon economy. Nat. Catal. 6, 563–573 (2023).

Lopez, G. et al. Hydrogen generation from biomass by pyrolysis. Nat. Rev. Methods Prim. 2, 1–13 (2022).

Giannozzi, P. et al. Advanced capabilities for materials modeling with quantum ESPRESSO. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 29, 465901 (2017).

Giannozzi, P. et al. QUANTUM ESPRESSO: a modular and open-source software project for quantum simulations of materials. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 21, 395502 (2009).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996).

Grimme, S. Semiempirical GGA-type density functional constructed with a long-range dispersion correction. J. Comput. Chem. 27, 1787–1799 (2006).

Grimme, S., Antony, J., Ehrlich, S. & Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 132, 154104 (2010).

Zhou, Y. et al. Long-chain hydrocarbons by CO2 electroreduction using polarized nickel catalysts. Nat. Catal. 5, 545–554 (2022).

Talirz, L. et al. Materials Cloud, a platform for open computational science. Sci. Data 7, 299 (2020).

Prandini, G., Marrazzo, A., Castelli, I. E., Mounet, N. & Marzari, N. Precision and efficiency in solid-state pseudopotential calculations. npj Comput. Mater. 4, 72 (2018).

Jette, E. R. & Foote, F. Precision determination of lattice constants. J. Chem. Phys. 3, 605–616 (1935).

Xiao, C. et al. High-index-facet- and high-surface-energy nanocrystals of metals and metal oxides as highly efficient catalysts. Joule 4, 2562–2598 (2020).

Mills, K. C. & Su, Y. C. Review of surface tension data for metallic elements and alloys: Part 1—Pure metals. Int. Mater. Rev. 51, 329–351 (2006).

Darby, M. T., Sykes, E. C. H., Michaelides, A. & Stamatakis, M. Carbon monoxide poisoning resistance and structural stability of single atom alloys. Top. Catal. 61, 428–438 (2018).

Fu, Q. & Luo, Y. Catalytic activity of single transition-metal atom doped in Cu(111) surface for heterogeneous hydrogenation. J. Phys. Chem. C. 117, 14618–14624 (2013).

Ouyang, M. et al. Directing reaction pathways via in situ control of active site geometries in PdAu single-atom alloy catalysts. Nat. Commun. 12, 1–11 (2021).

Santatiwongchai, J., Faungnawakij, K. & Hirunsit, P. Comprehensive mechanism of CO2 electroreduction toward ethylene and ethanol: the solvent effect from explicit water-Cu(100) interface models. ACS Catal. 11, 9688–9701 (2021).

Lu, P. et al. Realizing long-cycling all-solid-state Li-In||TiS2 batteries using Li6+xMxAs1-xS5I (M=Si, Sn) sulfide solid electrolytes. Nat. Commun. 14, 1–14 (2023).

Bussi, G., Donadio, D. & Parrinello, M. Canonical sampling through velocity rescaling. J. Chem. Phys. 126, 014101 (2007).

Marcinkowski, M. D. et al. Pt/Cu single-atom alloys as coke-resistant catalysts for efficient C–H activation. Nat. Chem. 10, 325–332 (2018).

Che, F., Ha, S. & McEwen, J. S. Elucidating the field influence on the energetics of the methane steam reforming reaction: a density functional theory study. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 195, 77–89 (2016).

Davis, J. & Barteau, M. Hydrogen bonding in carboxylic acid Ad layers on Pd (111): evidence for catemer formation. Langmuir 5, 1299–1309 (1989).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge financial support from Khalifa University of Science and Technology under projects RC2-2019-007, Research and Innovation Center on CO2 and Hydrogen (RICH Center), RC2-2018-024, Center for Catalysis and Separations (CeCaS) and CIRA-2020-077. Additional partial support has been provided by the Abu Dhabi Award for Research Excellence (AARE) 2019 through project AARE19−233. Computational resources from Johns Hopkins University Advanced Research Computing, the Research Computing Department at Khalifa University, and the RICH Center are greatly acknowledged. Johns Hopkins Advanced Research Computing Facilities (ARCH) is supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF) grant number OAC 1920103. Part of this work was carried out during a research visit of S. Alareeqi to the group of Prof. Clancy at Johns Hopkins University supported by Khalifa University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.A. performed the computational studies and drafted the manuscript. C.G. and D.B. assisted with the methodology, software, and interpretation of the DFT results. K.P. provided theory and interpretation support. P.C. and L.V. assisted with the conceptualization, supervision, and acquisition of computational resources and project funding. All authors contributed to the writing and final edition of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

AlAreeqi, S., Ganley, C., Bahamon, D. et al. Rational design of optimal bimetallic and trimetallic nickel-based single-atom alloys for bio-oil upgrading to hydrogen. Nat Commun 16, 2639 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-57949-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-57949-6