Abstract

Bacteria continually evolve. Previous studies have evaluated bacterial evolution in retrospect, but this approach is based on only speculation. Cohort studies are reliable but require a long duration. Additionally, identifying which genetic mutations that have emerged during bacterial evolution possess functions of interest to researchers is an exceptionally challenging task. Here, we establish a Rapid and Integrated Bacterial Evolution Analysis (RIBEA) based on serial passaging experiments using hypermutable strains, whole-genome and transposon-directed sequencing, and in vivo evaluations to monitor bacterial evolution in a cohort for one month. RIBEA reveals bacterial factors contributing to serum and antimicrobial resistance by identifying gene mutations that occurred during evolution in the major respiratory pathogen Klebsiella pneumoniae. RIBEA also enables the evaluation of the risk for the progression and the development of invasive ability from the lung to blood and antimicrobial resistance. Our results demonstrate that RIBEA enables the observation of bacterial evolution and the prediction and identification of clinically relevant high-risk bacterial strains, clarifying the associated pathogenicity and the development of antimicrobial resistance at genetic mutation level.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Bacteria emerged approximately 3.5 billion years ago and have continued to evolve according to the theory of evolution described in Charles Darwin’s “Origin of Species”, similar to human evolution1,2,3. This means that the history of human-bacterial coexistence and bacterial infections has historically been an evolutionary battle between bacteria and humans1.

For pathogenic and opportunistic bacteria, the evolution of pathogenicity, such as the acquisition of virulence factors and toxins and the enhancement of gene mutations, influences human health. In addition, bacteria have developed antimicrobial resistance (AMR), which has become a major concern worldwide, due to the acquisition of AMR genes and resistance-conferring gene mutations4,5. Scientists have attempted to retrospectively elucidate the evolutionary mechanisms of bacterial pathogenesis and the development of AMR by collecting clinical isolates6,7. Additionally, some researchers have attempted to monitor pathogen evolution in cohort studies8,9,10,11,12. Although these studies have succeeded in uncovering the parts of the mechanism, they have not provided a comprehensive understanding of bacterial evolution because retrospective analysis yields only speculative results, and cohort studies are reliable but time-consuming. Therefore, innovative methods must be developed to overcome these problems and uncover the mechanism of bacterial evolution for the benefit of human health. One of the best solutions to these problems is constructing a rapid analytical system to observe the details of bacterial evolution.

Klebsiella pneumoniae (Kp) is the main bacterium that causes infections in the lower respiratory tract infections, urinary tract, and bloodstream infections13. In 2019, more than 0.6 million deaths were caused by AMR-associated Kp infections, making Kp the third most prevalent bacterial species among the cases of AMR-associated deaths5. On the basis of clinical progression, Kp can be divided into two variants: classical and hypervirulent14. Hypervirulent Kp generally exhibits a hypermucoviscous (HMV) phenotype14 that is well known as a clinically important phenotype for Kp causing invasive syndromes such as liver abscess, meningitis, pleural empyema, or endophthalmitis15,16. In contrast, the latest meta-analysis revealed no significant difference in mortality between patients with bacteraemia caused by HMV-Kp (17.4%) and non-HMV-Kp (19.5%)17. These observations suggest the clinical impact of non-HMV-Kp. Although the characteristics (serotypes K1 and K2) and pathogenicity (including the expression of virulence factors such as rmpA and rmpA2 for enhanced capsular production, iutA, iroN, and the virulence IncHIB plasmid) of HMV-Kp15,18,19 and the association between capsular production and serum resistance in Kp are well understood6,14,16,20, evaluations of the true impact and potential risk of clinical progression of non-HMV-Kp infections are inferior to those of HMV-Kp infections. Therefore, it is logical to assess the associated risks of non-HMV-Kp infections.

Accordingly, we previously reported a non-HMV-Kp bloodstream infection that rapidly developed multidrug resistance during the course infection21. Bacteriological analysis revealed that a null mutation in mutS accompanied this development by the hypermutable phenotype. MutS is a DNA mismatch repair enzyme that immediately corrects erroneous nucleotide sequences and facilitates faithful DNA replication with MutL and MutH22,23. The above observation implies that we can predict bacterial evolution according to accelerated gene mutation frequency caused by the functional disruption of the enzymes.

Here, we establish a Rapid and Integrated Bacterial Evolution Analysis (RIBEA) method. RIBEA comprises serial passaging experiments, whole-genome sequencing (WGS), transposon-directed sequencing (TraDIS), and in vivo evaluation. This approach enables the monitoring of the long-term evolution of bacterial pathogenicity and AMR within one month by constructing and utilising hypermutable bacteria. By RIBEA, we reveal the potential risk of non-HMV-Kp infections by revealing their clinical progression and AMR by identifying the serum and AMR factors via the detection of gene mutations that actually occurred during evolution.

Results

Non-HMV-Kp carries a high risk of bloodstream infection

To evaluate the clinical impact of non-HMV-Kp, we first aimed to determine the clinical risk of all Kp infections. In our 5-year retrospective study of Kp infection cases in a university hospital, we compared the characteristics between patients with immunocompetent and immunosuppression (Supplementary Table 1) and revealed that bacteraemia and 60-days mortality are risk factors for immunosuppressed patients caused by Kp infection. We also compared the characteristics between patients with (n = 65) and without bacteraemia (n = 235), and also between patients who died within 60 days (n = 33) and those who survived (n = 267) (Supplementary Tables 2 and 3). These analyses provided the foundation for our multivariate analysis, identifying risk factors for mortality in bacteraemia caused by Kp infection in immunosuppressed patients (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Table 4).

a Influence of bacteraemia caused by Kp infection on 60-day mortality. Multivariate logistic regression analysis (two-sided) demonstrated that Kp bacteraemia was associated with increased 60-day mortality independent of these confounders. No multiple-comparison adjustments were applied. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. b Numbers of HMV-Kp and non-HMV-Kp isolates derived from clinical specimens. The percentage indicates the prevalence of HMV-Kp isolates. c Susceptibility of human serum. The values indicate the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of human serum (%, vol/vol in MHBII). d Distribution of serum MICs. The y-axis shows the prevalence of isolates among the HMV and non-HMV groups. The dotted red line indicates the breakpoint of serum resistance. No significant difference in serum resistance was observed between the HMV and non-HMV groups by two-sided Fisher’s exact test (p = 0.5574). e Frequency of gene mutation in the Kp clinical isolates determined via the rifampicin assay. We defined mutators as low (< 5 × 10−8), moderate (from 5 × 10−9 to 10−8), high (from 10−8 to 10−7), and hyper (> 10−7) according to their mutation. A hypermutator was identified from a clinical respiratory sample (non-HMV isolate SMKP590; mutation frequency: 4.43 × 10−6). The geometric means were indicated, and no significant differences in gene mutation frequency were detected among each isolation site by the two-sided Kruskal‒Wallis test (p = 0.2519). f Comparison of the mutation frequencies of the HMV-Kp (n = 26) and non-HMV-Kp (n = 241) clinical isolates. The value of the hypermutator non-HMV strain was removed to evaluate the majority. The geometric means and geometric standard deviations are given, and a two-sided Student’s t test was used for the statistical analysis. g Core genome SNP analysis of respiratory Kp clinical isolates. The 84 Kp clinical isolates identified by the MALDI Biotyper were 75 Kp strains, eight Klebsiella quasipneumoniae strains, and one Klebsiella variicola strain, as determined by average nucleotide identity (ANI) analysis. HMV (string test-positive) isolates were classified into several STs (ST23, ST39, ST65, ST86, ST218, ST268, ST458, ST893, and some novel STs) and are shown in the red square. We included the carbapenem-resistant Kp strains of ST258 from the NCBI database (shown in orange) as references.

Next, we evaluated the proportion of bloodstream infections caused by clinical Kp isolates. To conduct this analysis, we first performed a string test to distinguish the HMV- and non-HMV-Kp isolates from the 277 total clinical isolates. Among these 277 isolates, 29 (10.5%) were HMV-positive. The prevalence of HMV isolates at each isolation site ranged from 0 to 17% (Fig. 1b). Notably, none of the HMV isolates were collected from blood samples. Serum susceptibility was determined according to the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of human serum to estimate the ability of Kp to survive in the blood. The Kp clinical isolates presented various serum MICs, ranging from ≤ 16 to > 64%. When we defined isolates with MICs of higher than 48% serum were defined as serum-resistant, more than 40% of the total isolates were serum-resistant (Fig. 1c). Moreover, there was no significant difference in serum resistance between the HMV and non-HMV populations (Fig. 1d). These observations indicate that the potential risk of causal bloodstream infections and serum resistance is not associated primarily with the HMV-Kp phenotype.

Next, we evaluated the gene mutation frequency in the Kp clinical isolates (Fig. 1e). We found that the gene mutation frequencies of the Kp clinical isolates were diverse, ranging from 5.5 × 10−10 to 4.4 × 10−6 across the sites of infection. The mutation frequency was significantly higher in the non-HMV group than in the HMV group (Fig. 1f). These observations suggest that the Kp clinical isolates are a genetically heterogeneous population with varying adaptative evolutionary capabilities but indicate that the non-HMV phenotype has a greater propensity for gene mutation. We focused on Kp clinical isolates from respiratory specimens for further analysis because the majority of the Kp isolates were derived from respiratory samples, and the fact that respiratory Kp infections are the main source of bloodstream Kp infections16. Among the 84 Kp isolates derived from respiratory samples, the majority were non-HMV-Kp isolates (n = 69). Fifteen isolates were identified as HMV (string-test positive), and all the isolates were positive for rmpA2. In addition, 10 HMV-Kp isolates also possessed rmpA, and three isolates were positive for serotype markers K1 and K2 (Fig. 1g). Among the HMV isolates, ST23, ST65, and ST86 belong to major hypervirulent capsular type K1 or K2 and carry an IncHIB-type virulence plasmid (pLVPK). Mutation frequency was not associated with the possession of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase genes (blaCTX-M), HMV, or capsular type. We found that the 75 respiratory Kp isolates were genetically diverse in their core genome phylogeny and consisted of multiple clones.

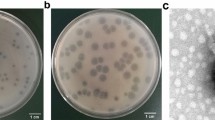

Construction of a rapidly evolving bacterial strain

To elucidate the pathogenesis of non-HMV-Kp, we constructed hypermutable bacteria via mutS deletion for RIBEA. We selected a non-HMV strain, namely, SMKP838, derived from a patient with pneumonia, which belongs to a major clone, ST 45, that causes respiratory non-HMV-Kp infections24. As anticipated, the mutation frequency of the mutS-deletion SMKP838 mutant increased up to 824-fold compared with that of the parent SMKP838, and the observed frequency (7.7 × 10−6) allowed this strain to be labelled hypermutable (Supplementary Fig. 1a). We used this mutant in serial passaging experiments in the presence of human serum or antimicrobial agents to observe the adaptive evolution that occurred in the blood or during antimicrobial treatment (Fig. 2a). The well with the highest serum concentration in which strains grew (sub-MIC) was selected and subcultured in a higher concentration of serum. This step was repeated for 20 days.

a, b Serial passaging experiments with the parent (wild-type, WT) and mutS mutant (ΔmutS) strains in the presence of human serum. The red circles indicate the wells in which the strains/mutants grew. The geometric means and geometric standard deviations from three independent experiments are given. c Venn diagram of the gene mutations accumulated in SMKP838ΔmutS clones (#1 to #3) during the serial passaging experiments in the presence of human serum after 20 days. The accumulated gene mutations are listed in Supplemental Dataset 1. d Schematic of the TraDIS analysis. e Volcano plots of SMKP838 genomes determined via TraDIS analysis in the presence of 40 mg/L SPA (blue) and 4% (green) and 8% (red) human serum. The x-axis shows the change in abundance of each SMKP838 gene compared with that in the control (a log2-fold change). The y-axis shows the p values of the detected SMKP838 genes compared with the control. f The number of genes detected via TraDIS with significantly increased or decreased detection in human serum compared with the control (FDRp < 0.05). g Venn diagram representing the integration of a total of 140 mutant genes identified in the serial passaging experiment in the presence of human serum in (c) and the genes associated with serum resistance derived from TraDIS analysis performed in the presence of 4% (620 genes) and 8% serum (794 genes) in (f). Putative genes involved in serum resistance when mutations enhance their function in blue, and genes involved in serum resistance when their function is disrupted/decreased are marked in red (less or more than a 2-fold difference in detection in the presence of human serum vs. without human serum in TraDIS, FDRp < 0.05, respectively). h Serum susceptibility of the SMKP838 pORTMAGE mutants. These mutants possessed gene mutation(s) identified in the serial passage experiments in the presence of serum, as shown in (b). PORTserumA (LOCUS_14270: p.Ala293Thr + ramA: p.Tyr34His), PORTserumB (LOCUS_21770: p.Leu113Pro + ramA: p.Tyr34His and a spontaneous mutation: glnD:p.Gly841Glu), PORTserumC (LOCUS_21770: p.Leu113Pro + ramA: p.Tyr34His), PORTserumD (LOCUS_39850: p.Val134Ala + ramA: p.Tyr34His), PORTserumE (ramA: p.Tyr34His and a spontaneous mutation: LOCUS_21770: p.Leu181Pro), and PORTserumF (ramA: p.Cys78Arg).

The hypermutable mutS-deletion mutant rapidly acquired serum resistance (on day 6) and continued to develop increased serum resistance, reaching a plateau at a serum MIC of 72% after 13 days (Fig. 2b). In contrast, the parent (wild-type) strain did not exceed the breakpoint of serum resistance after 20 days. The mutS-deletion mutants accumulated 48–60 nonsynonymous gene mutations in biological triplicate experiments with mutations in total 140 genes after 20 days of cultivation (Fig. 2c). A time-kill assay demonstrated that the mutS deletion resulted in the mutant having greater survival ability in the presence of human serum than that of the wild-type due to the accumulation of gene mutations (Supplementary Fig. 1b). This rapid bacterial evolution was also observed in the serial passaging experiments with ciprofloxacin, amikacin, and meropenem, which are clinically important antimicrobial agents against used to treat Kp infections (Supplementary Fig. 1c). The mutS-deletion mutant rapidly acquired AMR within 5 days, whereas wild-type SMKP838 did not exceed the breakpoints after passage for 20 days. A drastic increase in the number of gene mutations occurred in the mutS-deletion mutant during serial passaging (Supplementary Fig. 1d). Therefore, these observations suggest that the mutS-deletion mutant exhibits a higher frequency and accumulation of genetic mutations than the wild-type does, indicating an advantage in terms of environmental adaptation. Thus, we concluded that this rapid bacterial evolution approach is useful for determining how non-HMV-Kp evolution affects the ability of Kp to cause infection at different sites and the outcomes of antimicrobial treatment.

Interestingly, the numbers of gene mutations and genes that had mutations varied depending on selective pressures and affected bacterial growth (Supplementary Fig. 1e and f). Although the development of serum resistance did not influence antimicrobial susceptibility, the development of AMR decreased serum resistance (Supplementary Fig. 1g and h). Thus, this approach enabled us to identify distinct bacterial evolution patterns that were dependent on the environment.

Integrated analysis of serum and AMR analysis

We hypothesised that the bacterial factors contributing to serum resistance in non-HMV-Kp could be extrapolated from among the gene mutations occurring during serial passaging in the presence of human serum. However, we could not readily identify the gene associated with serum resistance because of the numerous accumulated gene mutations.

TraDIS is a powerful technique used to study the functions of genes on a genome-wide scale25. The method involves creating a large library of bacterial transposon mutants, each with a transposon insertion at a different location in the genome. The transposon, a mobile genetic element, randomly inserts itself into the DNA, disrupting the function of the gene at the insertion site. This transposon mutant library is cultured in two different environments (control vs. sample), and TraDIS analysis allows identification of the genes with transposon insertions from the bacterial DNA extracted after culture and comparison (Fig. 2d). By comprehensively extracting the transposon-inserted genes whose detection increased or decreased in the sample compared with that in the control, genes that are more or less frequently detected can be identified. Thus, TraDIS enables the comprehensive identification of bacterial factors essential for survival in different environments. Thus, we performed TraDIS, which can comprehensively detect the bacterial factors contributing to bacterial survival in human serum.

In this study, we performed TraDIS by using the transposon-mutant library of SMKP838 in the presence of either without, 4% (1/4 MIC), 8% (1/2 MIC) human serum, and 40 mg/L surfactant protein A (SPA) (Fig. 2e). SPA is an abundant antimicrobial protein in the airways and alveoli of the lungs26. The reproducibility of the TraDIS data was confirmed in additional biological samples (Supplementary Fig. 2a–e). The numbers of significantly enriched or depleted transposon-inserted genes in 4% (4/1 x MIC) and 8% (sub-MIC) serum (620 and 794 genes, respectively) were much higher than that (only 3 genes) in the presence of SPA (False Discovery Rate p-value, FDRp < 0.05, with more or less than a 2-fold difference vs. unsupplemented medium; Fig. 2f). These results suggest that human serum exerts stronger selective pressure than lung antimicrobial substances do, and the detected 620 and 794 transposon-inserted genes suggest that these genes may contribute to serum resistance.

Next, we merged the data for the genes that accumulated nonsynonymous mutations in mutS-deletion SMKP838 mutants after serial passaging in the presence of human serum and the data for the genes detected by TraDIS (Fig. 2g). Genes with significantly decreased detection in the presence of serum compared within the absence of serum via TraDIS analysis (minus fold change, FDRp < 0.05) are considered to have lost their function, which impairs bacterial growth in the presence of serum, due to transposon insertion. This implies that maintaining or enhancing the functions of these bacterial factors is important for growth in the presence of serum and that these factors are involved in serum resistance. Therefore, if a gene identified via TraDIS is mutated during serial passaging in the presence of serum, the mutation is considered to enhance the function of the encoded bacterial factor and contribute to increased serum resistance. Conversely, genes with significant detection increased in the presence of serum compared with the absence of serum via TraDIS analysis (plus fold-change, FDRp < 0.05) are considered to have lost their function, which results in a growth advantage in the presence of serum, due to transposon insertion. Thus, if a gene identified via TraDIS is mutated during serial passaging in the presence of serum, the mutation is considered to reduce the function of the encoded bacterial factor and is thus responsible for the increase in serum resistance. We identified a total of 22 shared genes (Fig. 2g, and Supplementary Table 5).

Next, we constructed specific gene deletion SMKP838 mutants and measured their serum MICs to determine changes in serum susceptibility. Among them, we observed gene-deletion mutants that decreased serum susceptibility (from a serum MIC of 14% to more than 16%) compared with that of the parent SMKP838 strain (Supplementary Fig. 2f). Finally, we identified 7 genes, namely, surA (encoding a chaperon), mrcB (encoding penicillin-binding protein 1B), ramA (encoding a DNA-binding transcriptional regulator), LOCUS_08550 (encoding a phosphoporin), LOCUS_10060 (encoding a putative sugar transferase), LOCUS_14270 (encoding a pyruvate kinase), and LOCUS_16740 (encoding a γ-glutamylcyclotransferase), which are bacterial factors that contribute to decreased serum susceptibility in non-HMV-Kp (p < 0.05). We also analysed the prevalence of isolates with disruptions or mutations in these bacterial factors by comparison with a public genome dataset, that included 3,447 Kp isolates (Supplementary Fig. 2g). This analysis revealed that certain isolates possessed disruptions or insertions in these factors, suggesting that the resulting the functional disruption could contribute to serum resistance. While not all isolates may contribute to serum resistance, some of the isolates may develop such resistance owing to mutations in these factors.

In addition, we constructed isogenic SMKP838 mutants via pORTMAGE mutagenesis that possessed the gene mutation(s) that occurred during the serial passage experiment in serum. These mutants also increased the serum MICs, and mutations in both LOCUS_14270 and ramA (PORTserumA mutant) conferred a serum-resistant phenotype, and other ramA mutation possessing mutants decreased the serum susceptibility (Fig. 2h). We also performed TraDIS analysis with clinically important antimicrobial agents and successfully distinguished the gene sets to predict the factors that are important for survival in these agents (Supplementary Fig. 3a and b). By merging the data with the accumulated nonsynonymous mutations in mutS-deletion SMKP838 mutants after serial passaging in the presence of antimicrobial agents, we further selected the gene sets the resistance genes occurred during bacterial evolution (Supplementary Fig. 3c). Finally, we confirmed that some of the identified genes contributed to the resistance by constructing isogenic mutants (Supplementary Fig. 3d).

These observations indicated that the integration of serial passaging experiments using rapidly evolving bacteria and TraDIS could be used to identify the contributing gene mutations that actually occurred during bacterial evolution.

RIBEA in non-HMV-Kp clinical isolates

To evaluate whether RIBEA can reveal the authentic evolution of bacteria that occurs in clinical isolates, we next performed a 20-day serial passaging experiment in the presence of human serum with randomly selected serum-sensitive non-HMV-Kp clinical isolates with hyper-, high- and low-mutation frequencies (Fig. 3a). Like the laboratory-derived mutS-deletion mutant, the hypermutable clinical isolate, SMKP590 (possessing five nucleotide deletions in mutH, 408_412delGCGCG) was the first to acquire serum resistance, which occurred after 3 days of passaging. The acquisition of serum resistance was also observed in five highly mutable Kp isolates, including one K. quasipneumoniae isolate. In contrast, lower mutable isolates did not develop serum resistance during 20 days of passaging (p < 0.05). Consistent with the findings in serum, SMKP590 also acquired AMR within 13 days, and a similar trend was observed with the mutS-deletion SMKP838 mutant, indicating a trade-off between the development of AMR and increased serum sensitivity (Supplementary Fig. 4).

a Serial passaging experiment in the presence of human serum. Fifteen serum-susceptible non-HMV-Kp clinical isolates (with serum MICs ranging from 8 to 16%) from among the hyper- (n = 1, SMKP590), high- (n = 9; including one K. quasipneumoniae strain), and low-mutator strains (n = 9) were inoculated in 96-well plates containing serial dilutions of human serum (from 4 to 68%) in MHBII for culture at 37 °C for 24 h and subcultured for 20 days. Significantly more high-mutator isolates acquired serum resistance than low-mutator isolates, as determined by two-sided Fisher’s exact test (p = 0.015). b Serum susceptibility and accumulated gene mutations in the hypermutable isolate, SMKP590, during the serial passaging experiment in (a). We determined the serum MICs (red circles) and number of gene mutations (orange, grey, and white represent nonsynonymous mutations, synonymous mutations, and gene mutations in noncoding regions, respectively) of SMKP590 mutants obtained during serial passaging in the presence of human serum. c Number of novel and accumulated gene mutations in SMKP590 during the serial passaging experiments in (a). The novel and accumulated (continuously detected) gene mutations were counted and compared with those of the day before. The mutated genes are shown in the Supplemental Data (Dataset 3). d Numbers of novel nonsynonymous and other gene mutations that occurred during the serial passaging experiments with SMKP590 in (a). Other genes contained synonymous mutations and gene mutations in noncoding regions. e Integrated analysis of serum resistance in SMKP590. We integrated the gene sets for serum resistance identified via TraDIS (Fig. 2) with the gene mutations accumulated in SMKP590 during the serial passaging experiment in the presence of human serum, as shown in (b). Putative genes involved in serum resistance are shown in blue and red (< 2-fold or >2-fold difference in the presence of human serum vs. without human serum via TraDIS, FDRp < 0.05, respectively; Supplemental Data, Dataset 4). f We listed the serum resistance-associated gene mutations of SMKP590 that occurred during the serial passage experiment. Blue and red represent decreased or increased genes, respectively, as shown in (e). The underlined genes are known to be associated with serum resistance23,57. D, Day.

By WGS, we found that SMKP590 gradually accumulated gene mutations along with increasing serum resistance, and we ultimately detected 74 gene mutations after 20 days of passaging (Fig. 3b). Interestingly, the numbers of novel and accumulated mutations in the genes increased or decreased, and the number of nonsynonymous mutations was also uniform throughout the passaging (Fig. 3c, d).

When we integrated and compared these data with the TraDIS data for SMKP838, we identified that 24 of the 103 nonsynonymous mutations that occurred during passaging were associated with serum resistance (Fig. 3e and Supplementary Table 6). These genes were consisted of eight putative genes involved in serum resistance when mutations enhance their function (< 2-fold difference in detection in the presence of human serum vs. without human serum via TraDIS, FDRp < 0.05), and 16 genes involved in serum resistance when their function is disrupted/decreased (> 2-fold difference in detection in the presence of human serum vs. without human serum via TraDIS, FDRp < 0.05). Twenty-one of these 24 genes, except, wzc, wecC, and gnd23, have not been reported to contribute to serum resistance. These gene mutations accumulated or disappeared on each day of cultivation (Fig. 3f). Taken together, these observations suggest that the current integrated approach is useful for evaluating the adaptative evolution of clinical bacterial isolates and predicting bacterial factors.

In vivo evaluation of the non-HMV-Kp strains that rapidly evolved

We evaluated the pathogenicity of the non-HMV-Kp strains derived from serial passaging experiments that rapidly evolved in a mouse pneumonia model. First, we used SMKP838 and the mutS-deletion mutant to establish intrabronchial infection. We found that infection could not be established without first inducing immunosuppression, as nonimmunosuppressed mice eradicated these strains from their lungs without developing any symptoms (Fig. 4a), suggesting that immunocompetent mice are protected. This result was not unexpected, as non-HMV-Kp is an opportunistic pathogen27. Thus, we utilised immunosuppressed model mice28. Immunosuppression drastically increased the bacterial load in the lungs (Fig. 4a) and blood (Fig. 4b) 32 h after infection. Thus, non-HMV-Kp strains can cause pneumonia and invade the bloodstream in immunosuppressed hosts. We then used this immunosuppression pneumonia model to compare the efficacy of ciprofloxacin treatments in mice infected with the wild-type and hypermutable mutant strains (Fig. 4c).

a, b Intrabronchial infection mouse model and bacterial viability assessment. An intrabronchial infection model was established using non-HMV-Kp SMKP838 (WT) and its mutS-deletion mutant (ΔmutS) (5 × 106 CFUs). Female BALB/c mice (10–12 weeks old), with or without immunosuppression, received 250/125 mg/kg cyclophosphamide monohydrate intraperitoneally prior to infection (n = 5 biologically independent experiments). Lung (a) and blood (b) bacterial counts were determined 48 hours post-infection. c Ciprofloxacin treatment and resistance analysis. Ciprofloxacin treatment was administered to infected immunosuppressed mice via intraperitoneal injection. d, e Bacterial counts in the lungs (d) and blood (e) were assessed with or without ciprofloxacin treatment (n = 6 biologically independent experiments). Parent strains (day 0) and ciprofloxacin-susceptible (CIPS) or ciprofloxacin-resistant (CIPR) mutants derived from 10, 19, or 20 days of serial passaging (Supplementary Figs. 4a, 5a). f, g Serum and ciprofloxacin susceptibility. Serum MICs were determined for SMKP838 and its mutants after 32 h of infection. Fifty colonies of each mutant were evaluated. h Ciprofloxacin MICs were measured in SMKP838 and its mutants post-ciprofloxacin treatment. i, j Lethality and histological examination. (i) Lethality assessment of SMKP838 WT (day 0), ΔmutS (day 0), and ΔmutS-serumR (day 20) mutants evolved under serum exposure (serum MIC: 72%, Supplementary Fig. 2c). Mice counts (biologically independent experiments): WT (n = 14), ΔmutS (n = 6), ΔmutS-serumR (n = 16), PORTserumA (n = 20). j Bacterial counts in the lungs and blood 32 hours post-infection (n = 6 biologically independent experiments). k Histological analysis (H&E staining) of infected immunosuppressed mouse tissues (lungs, liver, kidneys) 24 h post-infection. Severe bacterial infiltration (clumps) was noted in alveoli (red arrows), interstitium (yellow arrows), capillaries (B), and glomeruli (C) (white arrows). Histological scores (n = 3 biologically independent experiments) are shown on the right. Geometric means and standard deviations from biological independent experiments are shown (a–e, i, j, k), and two-sided one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s test was used vs. WT (day 0). Log-rank test was used in (i).

In contrast with the bacterial loads prior to ciprofloxacin treatment, the loads in the lungs of the mice infected with the wild-type strain and the mutS-deletion mutant (day 0) were drastically reduced after ciprofloxacin treatment (Fig. 4d), and no viable colonies were observed in the blood of the infected mice after treatment (Fig. 4e). In contrast, the mice infected with ciprofloxacin-resistant SMKP838 mutant derived after 19 days of serial passaging in the presence of ciprofloxacin [ΔmutS_CIPR (day 19)] (Supplementary Fig. 5) maintained the bacterial loads in both the lungs and blood after ciprofloxacin treatment. Notably, we observed the spontaneous development of serum-resistant and ciprofloxacin-resistant clones from mutS-deletion SMKP838 mutants after ciprofloxacin treatment (Fig. 4f–h). These observations indicate that increasing the mutation frequency in non-HMV-Kp strains results in the production of serum- and antimicrobial-resistant mutants in vivo and affects clinical outcomes.

In support of this hypothesis, both the serum-sensitive and the serum-resistant mutS-deletion mutants caused enhanced mortality than did the wild-type SMKP838 (p = 0.0246) (Fig. 4i). Moreover, the mortality rate that resulted after infection with the serum-resistant mutS-deletion mutant was higher than that caused by the serum-sensitive mutS-deletion SMKP838 mutant (p = 0.0012), and a higher load of the serum-resistant mutS-deletion mutant was detected in the blood (Fig. 4j). Severe tissue damage was observed in the livers and kidneys of infected mice harbouring the serum-sensitive and serum-resistant mutS-deletion SMKP838 mutants (Fig. 4k and Supplementary Fig. 6). Mortality caused by the the isogenic SMKP838 mutant, namely PORTserumA, which possesses two serum resistance mutations in LOCUS_14270 and ramA, was also significantly higher than that caused by the wild-type SMKP838 (p = 0.0391, Fig. 4i). Collectively, these results suggest that this in vivo model is suitable for evaluating the clinical risk of rapidly evolving non-HMV-Kp.

RIBEA of high-risk non-HMV-Kp clones

Finally, we evaluated the utility of RIBEA for currently important bacterial clones in clinical settings. In recent decades, high-risk non-HMV-Kp clones such as ST11 and ST258 have spread worldwide and become major clinical problems due to multidrug resistance29. We previously reported the presence of mutS mutations in ST11 and ST25821. This finding suggests that the worst-case scenario is that these international high-risk non-HMV-Kp clones develop pathogenicity via the accumulation of gene mutations4. We, therefore, constructed a multidrug-resistant ST258 mutant in the BIDMC1 strain (Fig. 5a) that contained a stop codon in mutS. The BIDMC1 mutS mutant exhibited a drastically increased mutation frequency (Fig. 5b) and rapidly acquired serum resistance after 3 days of passaging (Fig. 5c). In contrast, its growths were decreased (Fig. 5d–g). During serial passaging, the BIDMC1 mutS mutant accumulated more gene mutations than did the wild-type (Fig. 5h). Finally, we observed that the mutS mutant killed the mice significantly faster than did the wild-type (Fig. 5i). Taken together, these observations suggest that RIBEA enables prediction of the clinical risk of internationally distributed high-risk multidrug-resistant bacteria.

We used the non-HMV-Kp strain BIDMC1 as a representative for the internationally spreading high-risk clone ST258. a Antimicrobial susceptibility of BIDMC1. S and R indicate susceptible and resistant, respectively. b Gene mutation frequency of BIDMC1 and the mutS nonsense mutable mutant (BIDMC1 MutS_Tyr37Stop). A rifampicin assay was performed to determine gene mutation frequency. The floating bars represent the maximum and minimum values, and the lines represent the geometric means (n = 3 biologically independent experiments). A two-sided Student’s t test was used for the statistical analysis. c Serial passaging experiments with BIDMC1 and the mutS mutant in the presence of human serum. BIDMC1 (wild-type, WT) and BIDMC1 MutS_Tyr37Stop were used (the accumulated mutations are listed in Supplemental Data Dataset 6). The geometric means and geometric standard deviations for biologically independent triplicate experiments are given (d–g). Bacterial growth of the BIDMC1-derived mutants during the serial passaging experiment in (c). We examined three clones of each of the WT and MutS_Tyr37Stop strains. Bacterial growth was evaluated as turbidity (OD600) after 16 h of cultivation in MHBII in (d). Bacterial growth of the mutants derived after 20 days of the serial passaging experiment in the presence of human serum was also evaluated by counting the viable bacterial number as colony formation units (CFU) at 0, 1, 3, 6, and 16 h in (e–g). The means and standard deviations for biologically independent triplicate experiments are given. A two-sided one-way ANOVA test was used for statistical analysis with multiple comparisons vs WT Day 0 (* indicates p < 0.05). The significant dh, Number of accumulated gene mutations of BIDMC_1 and BIDMC_1 MutS_Tyr37Stop in (a). i Survival rates of immunosuppressed mice intrabronchially infected with BIDMC_1, MutS_Tyr37Stop, and serum-resistant MutS_Tyr37Stop (each n = 6 biologically independent experiments). The mouse infection model was the same as that described in Fig. 4c. The log-rank test was used for statistical analysis.

Discussion

Because it is challenging to observe bacterial evolution closely over a long time, elucidating the mechanisms of pathogenesis and the potential risks remain important focuses in the field of infectious diseases8,9,10,11,12,30.

Bacterial evolution assays (serial passaging experiments) using hypermutable strains have been established31. Using the rapid-bacterial evolution method, we consistently succeeded in dramatically accelerating the adaptive evolution of bacteria (more than 800-fold higher frequency than the wild-type strain) and initiated selective pressure-dependent evolution with an increase in gene mutations in non-HMV-Kp strains. As a result, we could observe the details of bacterial evolution, which sometimes takes decades or centuries, within only two weeks (the time at which a plateau was reached in the phenotype during the serial passaging experiments). However, the identification of novel bacterial factors among evolved bacteria is very challenging because of the numerous accumulated gene mutations. Therefore, no previous studies covering all genetic variations that occurred during the evolution period have identified bacterial factors. Moreover, previous studies have had a limited focus on inferable genes, resulting in genes that have not been previously associated with having a contribution among the numerous detected genes being out of scope or lower priority31,32,33. These limitations are bottlenecks in the comprehensive elucidation of bacterial evolution.

TraDIS is currently the most effective approach for identifying essential bacterial factors involved in the survival and/or adaptation of bacteria in specific environments25. Using TraDIS, several bacterial factors in Kp strains involved in serum resistance have been reported20,34. Certain serum resistome genes, such as wzc, wecC, and gnd, were identified in a previous study using the non-HMV ST25820. These genes are the well-known serum resistomes associated with capsular synthesis and production in non-HMV-Kp9,20,30,34 that were consistently identified via TraDIS in this study.

By applying RIBEA, we successfully selected the bacterial factors contributing to serum resistance during bacterial evolution and identified the gene mutations via rapid bacterial evolution assays and TraDIS. The gene sets obtained through this integrated analysis included several genes that had not previously been reported to contribute to serum resistance, such as ramA, LOCUS_14270 (encoding pyruvate kinase), and LOCUS_21770 (encoding a LacI family transcriptional regulator), along with their nonsynonymous mutations. RamA is known to be responsible for lipid A biosynthesis and to contribute to resistance against cationic antimicrobial peptides in serum35. Although another pyruvate kinase, PyrkF, was identified, its encoding gene was detected as a factor for capsule production through TraDIS analysis34. These observations suggest that these regulatory and/or glycosylation functions may contribute to serum resistance in non-HMV-Kp via outer membrane expression and/or composition changes. Similarly, we also successfully selected the bacterial factors and identified the gene mutations associated with AMR. Therefore, RIBEA can not only identify bacterial factors involved in pathogenicity and AMR but also comprehensively identify gene mutations involved in the serum resistance and AMR observed during authentic bacterial evolution as well as their genetic variations (gene mutations).

During the development of the RIBEA, we observed several derivative scientific findings. Using non-HMV-Kp as the bacterial evolution model revealed that the presence of human serum had a greater impactful than SPA. This can be explained by the presence of antibacterial components within the serum, including complement (which forms the membrane attack complex) and antimicrobial peptides36. Consistent with this finding, a previous study using Escherichia coli reported that the selection pressure provided by an environment is more essential for the evolution of novel traits than the mutational supply experienced by wild-type and mutator strains37. Thus, the environment (infection site) greatly affects the speed of evolution, which is consistent with the findings of a previous study38. Antimicrobial pressure provides a harsh environment for bacterial survival, but we revealed that non-HMV-Kp can overcome growth restrictions caused by clinically important antimicrobial agents via the accumulation of gene mutations. Therefore, RIBEA is also helpful in identifying the environments that promote bacterial evolution.

Under selective pressure, genetic mutations that are selected from spontaneous mutations and are beneficial for the survival and adaptation of bacteria will occur, but under nonselective pressure, harmful mutations will be eliminated owing to fitness costs39. Therefore, evaluating evolved mutants in vivo provides more accurate data than those previously estimated in vitro. One such example was observed in this study. During in vitro serial passaging experiments, a trade-off between the development of AMR and the inhibition of bacterial growth was observed in a non-HMV-Kp strain (SMKP838). However, in mouse models, certain combinations of gene mutations acquired during bacterial evolution reduce bacterial growth in vitro but significantly allow antimicrobial treatment to be overcome and allow bacteria to invade the bloodstream from the lungs. Another example is the trade-off between the development of serum resistance and the inhibition of bacterial growth observed in the multidrug-resistant international high-risk ST258 strain (BIDMC1). In mouse models, the evolved serum-resistant mutant displayed significantly increased virulence, overcoming the reduced bacterial growth observed in vitro. Hence, only in vitro bacterial evolution cannot accurately estimate clinical risks and an integrated evaluation with in vivo data is needed, suggesting that RIBEA provides a more accurate assessment of bacterial evolution. Overall, we demonstrated that RIBEA is a beneficial approach for understanding bacterial evolution, as it can identify novel bacterial factors and gene mutations that contribute to pathogenesis and AMR in vivo from numerous gene mutations occurring during evolution in a short-term cohort (Fig. 6a).

a Scheme of the RIBEA method developed in this study. We integrated serial passaging experiments to monitor the rapid bacterial evolution by using hypermutable strains in selective environments, such as different sites of infection and in the presence of antimicrobial agents; whole genome sequencing (WGS) to identify accumulated gene mutations during bacterial evolution; transposon-directed insertion sequencing (TraDIS) analysis to identify potential bacterial factors that contribute to survival in the selective environments (identification of resistance genes); and an in vivo model to evaluate the pathogenesis of the evolved bacteria and determine the potential clinical risk. RIBEA can be completed within approximately one month. b The mechanism by which pathogenicity develops in evolved bacteria. In this study, we revealed the pathogenesis mechanism and the potential clinical risk of the evolved non-HMV-Kp, a principal bacterial pathogen. Non-HMV-Kp does not exhibit typical clinical symptoms upon infection and can be eradicated by innate immune defences in immunocompetent hosts. In immunosuppressed (and/or immunodeficient) hosts, non-HMV-Kp infection can cause lower respiratory tract infections. Non-HMV-Kp, which has the potential for bacterial evolution (hyper- and high gene mutation frequencies), increases its clinical impact by spreading from the primary site (lung) to the blood with or without the development of antimicrobial (abxA) resistance, which leads to a decrease in the treatment efficacy of antimicrobial agents. Therefore, via RIBEA, we revealed the potential and the current clinical risks presented by bacteria that have a high frequency of gene mutations during infection.

In this study, we observed that bacteraemia caused by Kp infection is associated with the 60-day mortality rate and immunosuppression. Consistent with this, previous studies have reported that non-HMV-Kp lower respiratory tract infections and subsequent bacteraemia result in high mortality rates14,40,41, suggesting the importance of understanding the process of clinical progression in non-HMV-Kp infections. RIBEA showed that non-HMV-Kp has the ability to adapt to the pressures of human serum and antimicrobial agents during dissemination from the lungs to the blood. These findings suggest that the adaptative evolution of non-HMV-Kp influences patients’ conditions and the efficacy of antimicrobial therapy. Thus, RIBEA is useful for clarifying the clinical progression of the bacterial infection, as it revealed that non-HMV-Kp has more risk for immunosuppressed and/or immunodeficient hosts and that gene mutations in non-HMV-Kp can affect the infection outcome, suggesting that non-HMV-Kp cannot be underestimated in clinical settings (Fig. 6b).

This clinical risk should increase due to high gene mutation frequency, as demonstrated by the mutS-deletion mutants. We observed that the non-HMV-Kp clinical isolates comprised a more heterogeneous population in terms of gene mutation frequency than the HMV-Kp isolates. Heterogeneity is associated with bacterial colonisation, pathogenesis, and AMR12,33,42,43,44,45. However, conflicting observations that hypermutator strains are less virulent than the wild-type strain have also been reported46,47. These discrepancies could be resolved by applying RIBEA, as demonstrated in this study. Non-HMV-Kp clinical isolates with high mutation frequencies were able to overcome serum-mediated killing and antimicrobial treatment via the adaptative evolution under selective pressure. In addition, we observed that certain Kp isolate genomes from public datasets possess mutated bacterial factors involved in serum resistance, as identified by RIBEA in this study. Overall, we conclude that RIBEA can mirror the present and/or future of clinical bacterial isolates and is a useful tool for estimating the potential risk and identifying clinically high-risk clones.

The limitations of this study are that this integrated approach does not consider the influence of the acquisition of exogenous factors, such as virulence plasmids and horizontally transferred AMR genes, or large-scale nucleotide deletions/duplications48. The accumulation of gene mutations is also a survival strategy for bacteria, as shown by increased persistence49. In addition, randomised observational studies and multicentre and multinational analyses of clinical data on Kp infections are expected to strengthen the causal relationship between the risk factors estimated in this study and clinical outcomes. Thus, these persistent cohorts need to be evaluated, as a comprehensive evaluation of these systems will provide insight into bacterial evolution and survival strategies. In addition, a detailed biological analysis of the identified bacterial factors and those gene mutations via RIBEA is needed to elucidate the mechanism of bacterial evolution.

In conclusion, in this study, the adaptive evolution of bacteria was demonstrated in a short time, and predictions of bacterial adaptation and identification of causal factors was made possible. Such predictions are also helpful for assessing the bacterial clones we should be aware of today, as shown here regarding the health risk of the internationally distributed high-risk multidrug-resistant non-HMV-Kp clone ST258. Therefore, our established rapid and integrated bacteriological approach is a beneficial and suitable analysis method for elucidating the important bacterial factors and the gene mutations of bacterial survival, adaptation, and infection and for predicting the outcomes of infection by various pathogenic bacteria and multidrug-resistant bacteria. By providing the newly identified bacterial factors and the gene mutations through RIBEA to researchers with relevant interests, we hope they will carry out detailed functional and structural analyses and could widely contribute to progress in bacterial ecology, including infection and antimicrobial resistance. Thus, RIBEA and its descendants have the potential to accelerate our understanding of bacterial evolution along with human evolution and become valuable tools for predicting the future of the Earth’s ecosystem, which is largely responsible for determining human life.

Methods

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the Sapporo Medical University Hospital Institutional Review Board (IRB no. 272-70) and Sapporo Medical University Animal Care and Use Committee (nos. 17-137, 18-083, and 20-006).

Clinical epidemiology

Clinical epidemiology analysis was performed using 695 Kp infections reported from 2017 to 2022 at Sapporo Medical University Hospital, including 393 Colonisation and 302 Infection cases. The Infection cases classified according to the presence or absence of immunosuppression, site of infection, and presence or absence of bacteraemia. The contingency tables were analysed by Fisher’s exact test. A p-value < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Bacterial isolation, antimicrobial susceptibility testing, and string test

A total of 277 Kp strains were isolated from clinical specimens derived from hospitalised patients at Sapporo Medical University Hospital between 2017 and 2021. These clinical specimens included 100 urine samples, 113 respiratory samples, 12 blood samples, and 52 other samples (drainage, tongue coating, skin, vaginal lubricant, pus, and bile). Identification of Kp (K. pneumoniae subsp.) was performed using MALDI Biotyper (Bruker Corporation, Billerica, MA, USA). BIDMC_1, a carbapenem-resistant Kp strain isolated at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Centre (BIDMC), was provided by BEI Resources (NIAID, NIH, USA).

The antimicrobial susceptibility of the Kp strains was tested via the broth microdilution method, and the results were interpreted according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) recommendations50. In this study, the following antimicrobial agents were used: ciprofloxacin (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation, Osaka, Japan), ciprofloxacin hydrochloride monohydrate (Tokyo Chemical Industry, Tokyo, Japan), amikacin (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation), kanamycin (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation), and meropenem (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation).

HMV strains were defined as giving a positive string test result, as previously described51. A single colony grown overnight on Mueller-Hinton II (MHII) agar was collected, and the formation of a string > 5 mm in length was defined as a positive result. For the detection of hypervirulence factors (serotypes K1 and K2, rmpA, rmpA2, iutA, iroN, and the IncHIB plasmid), multiplex PCR was performed as previously described18.

Serum susceptibility

In this study, we used commercially available human serum from individual healthy donors (Cedarlane Laboratories Ltd, Burlington, Canada). The serum MIC was defined as the minimum serum concentration (%) that prevented the visible microorganism growth. We set the resistance breakpoint at 32%, and isolates whose serum MIC was higher than 48% of serum MIC were defined as serum-resistant isolates because this concentration is the serum composition of human whole blood (around 40%). For the measurement of serum MICs, the concentration was increased twofold from 0.5 to 32 mg/L. From 32 to 64 mg/L, the increase was set at increments of 16 mg/L to better understand serum resistance levels and to avoid misjudging strains with serum MICs ranging from 40 to 64 mg/L as being judged as having a serum MIC of 32 mg/L, which would incorrectly classify them as serum-susceptible. For the measurement of serum MICs in the serial passaging experiment, the concentration was increased in more detail, in increments of 4%, from 4% to 72%, due to the monitoring of bacterial evolution.

Kp strains were grown in 0.5 ml of tryptic soy broth (TSB) from an overnight culture. The strains were diluted 10−4-fold (105 CFU/ml) and incubated in plates with different concentrations of serum in each well. After 20 h, the bacterial growth was visually confirmed in the wells with high serum concentrations due to the high optical density (OD600 nm).

Determination of mutation frequency

The mutation frequency was determined via a rifampicin assay52. The Kp isolates were cultured overnight in TSB. The solution was concentrated 10-fold and plated onto MHII agar plates supplemented or not with 100 mg/L rifampicin, and the plates were subsequently cultured at 37 °C for 24 h. After cultivation, the colony-forming units (CFUs) that grew on the agar plates were counted. Gene mutation frequency was calculated as [CFUs on the rifampicin-supplemented MHII agar plate]/[CFUs on the unsupplemented MHII agar plate]. We defined the mutator types as hyper (> 10−7), high (from 10−8 to 10−7), moderate (from 5 × 10−8 to 10−8), and low (< 5 × 10−8). Student’s t test was used for statistical analysis. A p-value < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Serial passaging experiments

Serial passaging experiments were performed by incubating Kp isolates (SMKP838, SMKP590, and BIDMC) in 96-well plates with MHBII containing various concentrations of human serum (the concentration was increased in increments of 4%, from 4% to 72%) or antimicrobial agents (ciprofloxacin, amikacin, and meropenem), as previously described53. For the experiments using the other Kp clinical isolates, we selected 19 serum-susceptible Kp isolates (with serum MICs ranging from 8 to 16%) from among the hyper- (n = 1), high- (n = 9; containing one K. quasipneumoniae), and low-mutators strains (n = 9) from the serial passaging experiment in the presence of human serum. We selected the well with the highest concentration (sub-MIC) of human serum or antimicrobial agent in which the bacteria grew and diluted the bacterial culture 100-fold with 0.85% NaCl. Then, 1 µL of the diluted solution was inoculated in 96-well plates containing 100 µL of MHBII with various concentrations of human serum or antimicrobial agents for cultivation at 37 °C for 24 h. Serial passaging was repeated for 20 days in triplicate.

Time-killing assay

Single colonies of SMKP838 and the mutS mutant strains were grown overnight in TSB media. The culture mixtures were adjusted to a final concentration of 1 × 105 CFU/ml and incubated for 0–24 h with each serum-containing solution (1/4 × MIC, 1 × MIC, or 2 × MIC) or in solution without serum at 37 °C without shaking. The assay results were determined at 0 min, 30 min, 1, 3, 6, and 24 h.

WGS

Genomic DNA was isolated with a DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Hulsterweg, The Netherlands). The DNA library was prepared with a Nextera XT DNA Library Preparation Kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) to sequence 300 bp paired-end reads according to the manufacturer’s protocol. An Illumina MiSeq was used for WGS. The CTX-M genes were identified by Resfinder (https://www.genomicepidemiology.org) using the assembled genome data. MLST was performed using the Institute Pasteur MLST database and software (https://bigsdb.pasteur.fr/klebsiella/). Fast average nucleotide identification (FastANI) against the type strain genome was utilised for species identification. Core genome single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP)-based phylogenetic analysis was conducted, using the Kp ATCC 35657 genome (accession number: CP015134.1) as a reference for mapping. Mapping and core genome extraction were performed using BWA version 0.7.17 with the bwasw option, SAMtools version 1.6 with the mpileup option, and VERSCAN version 2.3.9 with the mpileupcns option. Estimated homologous recombination regions were excluded using ClonalFrameML version v1.11-2. Snp-dists was used to determine the pairwise SNP distance. A phylogenetic tree was generated using FastTree version 2.1.11 and FigTree version 1.4.4 (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/). The number of gene mutations accumulated during serial passaging experiments was analysed by mapping the genome reads to the reference genome (wild-type strain on day 0) obtained via WGS, followed by basic variant detection using CLC Genomics Workbench 21 (QIAGEN).

Determination of bacterial growth

Bacterial growth was monitored by measuring the turbidity (OD600) using an Infinite M200 PRO multimode microplate reader (Tecan, Kawasaki, Japan). Strains were grown in 0.5 ml of TSB (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) overnight at 37 °C, and 1 × 105 CFU/ml bacteria were cultured in 0.1 ml of MHBII broth (Becton Dickinson) in a 96-well plate at 37 °C with shaking at 140 rpm for 16 h. Bacterial growth curves were generated from the measurements taken every 10 min for 16 h. Bacterial growth of the mutants derived after 20 days of the serial passaging experiment in the presence of human serum was also evaluated by counting the viable bacterial number as CFU at 37 °C with shaking at 140 rpm for 0, 1, 3, 6, and 16 h. Each 1 ml of the 10-fold serial dilution with 0.85% NaCl was plated on Easy Plate AC (Kikkoman Corp., Chiba, Japan), and CFUs were counted after 48 h of cultivation at 37 °C.

TraDIS

The SMKP838 transposon library was constructed using the EZ-Tn5™ <KAN-2> Tnp Transposome™ Kit (Epicentre, Madison, WI, USA). Bacteria with transposase introduced by electroporation (2.5 kV/cm, 200 Ω, and 25 μF) were selected on the basis of the formation of colonies on MHII agar containing 50 mg/L kanamycin. Over 100,000 colonies were collected, pooled, and frozen at − 80 °C in TSB with 10% glycerol as stock solutions until use. The transposon mutant library (106 CFUs/ml) was inoculated into 1 ml of plain MHBII, MHBII containing 4% or 8% serum, or MHBII containing 40 mg/L SPA and cultured at 37 °C for 20 h. Total DNA was isolated using the Wizard Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). Total DNA (500 ng) was used to prepare the DNA library for TraDIS using the NEBNext Ultra II FS DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA). After fragmentation, end repair, 5’ phosphorylation, dA-tailing, adaptor ligation, and size selection (275-475 bp) according to the manufacturer’s protocol, the transposon-inserted genes were amplified via PCR using NEBNext Ultra II Q5 Master Mix (New England Biolabs), 20 nM primers [NEBTnF2fas (5’-TCGACCTGCAGGCATGCAAGCTTCAGGGTTGAGATGTG-3’) and NEBTn5-700 (5’-GTGACTGGAGTTCAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATC-3’)], and 20 ng of fragmented DNA as the template under the following conditions: initial denaturation at 98 °C for 30 sec, 22 cycles of 98 °C for 10 sec and 72 °C for 1 min and 15 sec, and a final extension at 72 °C for 2 min. After PCR product was purified using AMPure XP beads (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA), enrichment PCR was performed using the KAPA HiFi HotStart Library Amplification Kit (Roche, Basel, Switzerland), 20 nM NEBNext i700 primers [including NEBNext Multiplex Oligos for Illumina (New England Biolabs) and NEBTn5-501-3 (5’- AATGATACGGCGACCACCGAGATCTACACTATAGCCTACACTCTTTCCCTACACGACGCTCTTCCGATCTTCGACCTGCAGGCATGCAAGCTTC-3’)], and 20 ng of the purified DNA as the template under the following conditions: initial denaturation at 98 °C for 45 sec, 10 cycles of 98 °C for 15 sec, 60 °C for 30 sec, and 72 °C for 10 sec, and a final extension at 72 °C for 30 sec. The PCR products were purified and selected on the basis of size (average: 650 bp) using AMPure XP beads. These products were pooled, and a NovaSeq600 was used for TraDIS. TraDIS analysis was performed according to a previous study34, and a false discovery rate-adjusted p-value (FDRp) < 0.05 (vs. unsupplemented medium) was considered significant.

Genes with significantly lower detected levels in serum or SPA samples (> 2-fold vs. unsupplemented medium) were considered putative serum or SPA resistance genes.

Construction of the gene deletion mutants

The mutS-deletion SMKP838 mutant and each putative serum resistance-associated gene were generated via the λ-Red recombinase system, as previously described, using pKD46-hyg54,55. Each gene was replaced with Mini genes containing kanamycin resistance cassettes (Gene Bridges, Heidelberg, Germany) and 50 bases corresponding to the upstream and downstream regions of the target genes. Gene deletion was confirmed via PCR using the specific primers listed in Supplemental Data Dataset 7.

Construction of the isogenic non-HM-Kp mutants

The isogenic SMKP838 strains that developed gene mutation(s) during the serial passaging experiment in serum were constructed by pORTMAGE56. Hygromycin-integrated pORTMAGE (pOSTMAGE-hyg) was generated as previously described21. The pooled 90 bp oligonucleotides of putative serum- and antimicrobial-resistance gene mutations (listed in Supplemental Data Dataset 7) were electroporated into the Kp SMKP838 strain harbouring pORTMAGE-hyg, and approximately 90 clones were selected after 4-6 pORTMAGE cycles. The serum- and antimicrobial-susceptibilities of the clones were evaluated by determining the MICs as described in the Serum susceptibility and antimicrobial susceptibility testing sections.

Prevalence of serum resistance gene mutations in public databases

To investigate the frequency of gene depletion or mutation in clinical isolates of Kp, we downloaded 3447 genome sequences of Kp isolates from the BV-BRC database (https://www.bv-brc.org/). The genome sequences retrieved for use in this study were derived from human isolates between 2019 and 2023 and registered in the database by the end of 2023. We also excluded strains with abnormal genome sizes, high contamination values or low completeness using checkM. The genome sequences were translated into amino acid sequences using getorf included in the EMBOSS package for all open reading frames (ORFs) longer than 50 amino acids. We subsequently used BLASTp in a local environment to search for the amino acid sequences of the nine proteins of the clinical strain SMKP838. Strains possessing an ORFs with sequence lengths matching each query protein were determined to be conserved. The protein sequences that matched those of the SMKP838 strain were classified as identical, whereas the proteins with at least one amino acid mutation were labelled as mutated. In the initial BLASTp searches, strains that did not possess an ORF with an appropriate length were further analysed by examining the ORF with the highest bitscore to identify sequence alterations due to nonsense or indel mutations. These were classified as not conserved. Strains for which no matching results were found were labelled not-found.

Mouse models of lung and bloodstream infection

Ten- to 12-week-old female BALB/c mice were anaesthetised and infected transbronchially with 50 μl of a 1 × 108 CFU/ml solution using a microsprayer (TORAY PRECISION, Tokyo, Japan). The mice were immunosuppressed by administrating cyclophosphamide monohydrate (lot no. SKE6784; FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation, Osaka, Japan) via intraperitoneal injection as follows: 250 mg/kg five days prior to infection and 125 mg/kg one day prior to infection as a previous study28. In the treatment group, the mice were injected subcutaneously with 100 mg/kg ciprofloxacin monohydrochloride (Tokyo Chemical Industry, Tokyo, Japan) 1 and 24 h after infection. After 48 h (or 32 h when the prelethal critical endpoint had been reached) of infection, the mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation. The lungs were washed with sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and homogenised with a gentleMACS dissociator (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). The homogenates were plated to determine the number of CFUs per lung. Blood was collected by puncturing the jugular vein. One drop of blood was added to 1 ml of PBS, vortexed, and then cultured on an appropriate plate. In the experiments, wild-type-derived strains were selected by seeding on MHII agar supplemented with 100 mg/L ampicillin sodium, and the ΔmutS-derived strains were selected on MHII agar supplemented with 50 mg/L kanamycin to eliminate the effects of other indigenous and environmental bacteria. Fifty colonies from each sample were randomly selected, and their serum MICs were determined.

Evaluation of the extent of Klebsiella infiltration

H&E-stained slides were examined under a microscope to evaluate the extent of Klebsiella infiltration in the following tissues: alveoli, capillaries, and interstitium of the lungs, glomeruli, capillaries, and interstitium of the kidneys; and the Gleason sheath, sinusoids, and central veins of the liver. The degree of infiltration was classified as follows: none, mild (small amounts in 1-2 locations), moderate (less confluent than severe), and severe (large amounts in multiple locations). A pathologist (AT) and a trained researcher blinded to the conditions evaluated the whole slides. Conflicting results were discussed, and a consensus was reached.

Construction of mutS-mutated BIDMC_1

Since the λ-Red recombination system was unable to generate mutS-deficient strains of BIDMC1, we used pORTMAGE and constructed mutS-mutated BIDMC1 strain (BIDMC1 MutS_Tyr37STOP)21. The transformants were produced via electroporation. Oligonucleotides (90 bp) for mutS containing the C111T mutation were designed using the MEGA Oligo Design Tool: MegamutS,CGCAACATCCTGACATTCTGCTGTTTTACCGGATGGGGGATTTTTAaGAGCTATTTTATGACGATGCGAAACGCGCCTCGCAGCTGCTCG; where the bold letter a indicates an introduced base. Gene replacement was confirmed by direct DNA sequencing.

Statistical analysis

All the data were analysed by using GraphPad Prism 9 (GraphPad Software, Inc.; San Diego, CA, USA), R version 4.4.0 (R Core Team, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, 2024, https://www.R-project.org) and JMP Pro 17.0.0 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). One-way ANOVA, An unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t test or a two-tailed Mann‒Whitney U test was used to compare two groups, and Dunn’s comparison test, followed by the Kruskal–Wallis test, was used to compare three or more groups. In addition, the log-rank test was used for survival data analysis. Statistical methods and p values are given in each figure legend. A p-value < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. In addition, Fisher’s exact test and Student’s t test were used to compare the two groups in the clinical analysis. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to assess factors associated with bacteraemia, immunosuppression and death within 60 days, and age, sex, body mass index (BMI), haemoglobin, albumin, smoking status, and overall length of hospital stay were included as covariates. Individual models of clinical outcomes were used to account for collinearity.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The NGS data are available in the NCBI database with the following accession numbers; DRR503736-DRR503819 for the genomic sequences of the Kp clinical isolates; DRR503832-DRR503857 for the genomic sequences of the SMKP838 strains and mutS deletion mutants obtained from the serial passaging experiments; DRR504916-DRR505017 for the genomic sequences of the Kp clinical isolates obtained from the serial passage experiments; and DRR503820-DRR503831 for the TraDIS data. There are no restrictions on these data. They are freely accessible to all users via the hyperlink. Source data are provided in this paper.

References

Karlsson, E. K., Kwiatkowski, D. P. & Sabeti, P. C. Natural selection and infectious disease in human populations. Nat. Rev. Genet. 15, 379–393 (2014).

Woese, C. R. Bacterial evolution. Microbiol. Rev. 51, 221–271 (1987).

Woese, C. R., Kandler, O. & Wheelis, M. L. Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87, 4576–4579 (1990).

Mancuso, G., Midiri, A., Gerace, E. & Biondo, C. Bacterial antibiotic resistance: the most critical pathogens. Pathogens 10, 1310 (2021).

Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet 399, 629–655 (2022).

Ernst, C. M. et al. Adaptive evolution of virulence and persistence in carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Nat. Med. 26, 705–711 (2020).

Marsh, J. W. et al. Evolution of outbreak-causing carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae ST258 at a tertiary care hospital over 8 years. mBio 10, e01945–19 (2019).

Lenski, R. E. & Travisano, M. Dynamics of adaptation and diversification: a 10,000-generation experiment with bacterial populations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91, 6808–6814 (1994).

Barrick, J. E. et al. Genome evolution and adaptation in a long-term experiment with Escherichia coli. Nature 461, 1243–1247 (2009).

Blount, Z. D., Borland, C. Z. & Lenski, R. E. Historical contingency and the evolution of a key innovation in an experimental population of Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 7899–7906 (2008).

McDonald, M. J. Microbial experimental evolution - A proving ground for evolutionary theory and a tool for discovery. EMBO Rep. 20, e46992 (2019).

Frazao, N. et al. Two modes of evolution shape bacterial strain diversity in the mammalian gut for thousands of generations. Nat. Commun. 13, 5604 (2022).

Wang, G., Zhao, G., Chao, X., Xie, L. & Wang, H. The characteristic of virulence, biofilm and antibiotic resistance of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17, 6278 (2020).

Catalan-Najera, J. C., Garza-Ramos, U. & Barrios-Camacho, H. Hypervirulence and hypermucoviscosity: two different but complementary Klebsiella spp. phenotypes? Virulence 8, 1111–1123 (2017).

Shon, A. S., Bajwa, R. P. & Russo, T. A. Hypervirulent (hypermucoviscous) Klebsiella pneumoniae: a new and dangerous breed. Virulence 4, 107–118 (2013).

Lee, H. C. et al. Clinical implications of hypermucoviscosity phenotype in Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates: association with invasive syndrome in patients with community-acquired bacteraemia. J. Intern. Med. 259, 606–614 (2006).

Namikawa, H. et al. Differences in severity of bacteraemia caused by hypermucoviscous and non-hypermucoviscous Klebsiella pneumoniae. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 61, 106767 (2023).

Yu, F. et al. Multiplex PCR analysis for rapid detection of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenem-resistant (sequence type 258 [ST258] and ST11) and hypervirulent (ST23, ST65, ST86, and ST375) strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 56, e00731–18 (2018).

Russo, T. A. et al. Identification of biomarkers for differentiation of hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae from classical K. pneumoniae. J. Clin. Microbiol. 56, e00776–18 (2018).

Short, F. L. et al. Genomic profiling reveals distinct routes to complement resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Infect. Immun. 88, e00043–20 (2020).

Sato, T. et al. Emergence of the novel aminoglycoside acetyltransferase variant aac(6’)-Ib-D179Y and acquisition of colistin heteroresistance in carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae due to a disrupting mutation in the DNA repair enzyme MutS. mBio 11, e01954–20 (2020).

Li, G. M. Mechanisms and functions of DNA mismatch repair. Cell Res. 18, 85–98 (2008).

Prunier, A. L. & Leclercq, R. Role of mutS and mutL genes in hypermutability and recombination in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 187, 3455–3464 (2005).

Shi, Q. et al. Transmission of ST45 and ST2407 extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in neonatal intensive care units, associated with contaminated environments. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 31, 309–315 (2022).

Opijnen, T. et al. Transposon insertion sequencing: a new tool for systems-level analysis of microorganisms. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 11, 435–442 (2013).

Wu, H. et al. Surfactant proteins A and D inhibit the growth of gram-negative bacteria by increasing membrane permeability. J. Clin. Invest. 111, 1589–1602 (2003).

Wyres, K. L., Lam, M. M. C. & Holt, K. E. Population genomics of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 18, 344–359 (2020).

Zuluaga, A. F. et al. Neutropenia induced in outbred mice by a simplified low-dose cyclophosphamide regimen: characterization and applicability to diverse experimental models of infectious diseases. BMC Infect. Dis. 6, 55 (2006).

David, S. et al. Epidemic of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in Europe is driven by nosocomial spread. Nat. Microbiol. 4, 1919–1929 (2019).

Nucci, A., Rocha, E. P. C. & Rendueles, O. Adaptation to novel spatially-structured environments is driven by the capsule and alters virulence-associated traits. Nat. Commun. 13, 4751 (2022).

Giraud, A. et al. Costs and benefits of high mutation rates: adaptive evolution of bacteria in the mouse gut. Science 291, 2606–2608 (2001).

Lindgren, P. K., Karlsson, A. & Hughes, D. Mutation rate and evolution of fluoroquinolone resistance in Escherichia coli isolates from patients with urinary tract infections. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47, 3222–3232 (2003).

Marvig, R. L., Johansen, H. K., Molin, S. & Jelsbak, L. Genome analysis of a transmissible lineage of Pseudomonas aeruginosa reveals pathoadaptive mutations and distinct evolutionary paths of hypermutators. PLoS Genet. 9, e1003741 (2013).

Dorman, M. J., Feltwell, T., Goulding, D. A., Parkhill, J. & Short, F. L. The capsule regulatory network of Klebsiella pneumoniae defined by density-TraDISort. mBio 9, e01863–18 (2018).

De Majumdar, S. et al. Elucidation of the RamA regulon in Klebsiella pneumoniae reveals a role in LPS regulation. PLoS Pathog. 11, e1004627 (2015).

Bain, W. et al. Increased alternative complement pathway function and improved survival during critical illness. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 202, 230–240 (2020).

Karve, S. & Wagner, A. Environmental complexity is more important than mutation in driving the evolution of latent novel traits in E. coli. Nat. Commun. 13, 5904 (2022).

Buffet, T. et al. Nutrient conditions are primary drivers of bacterial capsule maintenance in Klebsiella. Proc. Biol. Sci. 288, 20202876 (2021).

Mérino, D. et al. A hypermutator phenotype attenuates the virulence of Listeria monocytogenes in a mouse model. Mol. Microbiol. 44, 877–887 (2002).

Ito, R. et al. Molecular epidemiological characteristics of Klebsiella pneumoniae associated with bacteremia among patients with pneumonia. J. Clin. Microbiol. 53, 879–886 (2015).

Meatherall, B. L. et al. Incidence, risk factors, and outcomes of Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremia. Am. J. Med. 122, 866–873 (2009).

Ruiz, L. M. R., Williams, C. L. & Tamayo, R. Enhancing bacterial survival through phenotypic heterogeneity. PLoS Pathog. 16, e1008439 (2020).

El Meouche, I. & Dunlop, M. J. Heterogeneity in efflux pump expression predisposes antibiotic-resistant cells to mutation. Science 362, 686–690 (2018).

Hall, L. M. C. & Henderson-Begg, S. K. Hypermutable bacteria isolated from humans–A critical analysis. Microbiology 152, 2505–2514 (2006).

Oliver, A., Canton, R., Campo, P., Baquero, F. & Blazquez, J. High frequency of hypermutable Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis lung infection. Science 288, 1251–1254 (2000).

Mena, A. et al. Inactivation of the mismatch repair system in Pseudomonas aeruginosa attenuates virulence but favors persistence of oropharyngeal colonization in cystic fibrosis mice. J. Bacteriol. 189, 3665–3668 (2007).

Montanari, S. et al. Biological cost of hypermutation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains from patients with cystic fibrosis. Microbiology 153, 1445–1454 (2007).

Hacker, J., Blum-Oehler, G., Muhldorfer, I. & Tschape, H. Pathogenicity islands of virulent bacteria: structure, function and impact on microbial evolution. Mol. Microbiol. 23, 1089–1097 (1997).

Andersson, D. I. Persistence of antibiotic resistant bacteria. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 6, 452–456 (2003).

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. M100 Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 34 th ed., 200–216 (2024).

Vila, A. et al. Appearance of Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess syndrome in Argentina: case report and review of molecular mechanisms of pathogenesis. Open Microbiol. J. 5, 107–113 (2011).

Zhou, H. et al. The mismatch repair system (mutS and mutL) in Acinetobacter baylyi ADP1. BMC Microbiol. 20, 40 (2020).

Khil, P. P. et al. Dynamic emergence of mismatch repair deficiency facilitates rapid evolution of ceftazidime-avibactam resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa acute infection. mBio 10, e01822–19 (2019).

Datsenko, K. A. & Wanner, B. L. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 6640–6645 (2000).

Sato, T. et al. Tigecycline nonsusceptibility occurs exclusively in fluoroquinolone-resistant Escherichia coli clinical isolates, including the major multidrug-resistant lineages O25b:H4-ST131-H30R and O1-ST648. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 61, e01654–16 (2017).

Nyerges, Á. et al. A highly precise and portable genome engineering method allows comparison of mutational effects across bacterial species. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, 2502–2507 (2016).

Holmes, C. L., Anderson, M. T., Mobley, H. L. T. & Bachman, M. A. Pathogenesis of gram-negative bacteremia. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 34, e00234–20 (2021).

Acknowledgements