Abstract

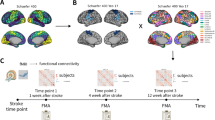

The red nucleus, a large brainstem structure, coordinates limb movement for locomotion in quadrupedal animals. In humans, its pattern of anatomical connectivity differs from that of quadrupeds, suggesting a different purpose. Here, we apply our most advanced resting-state functional connectivity based precision functional mapping in highly sampled individuals (n = 5), resting-state functional connectivity in large group-averaged datasets (combined n ~ 45,000), and task based analysis of reward, motor, and action related contrasts from group-averaged datasets (n > 1000) and meta-analyses (n > 14,000 studies) to precisely examine red nucleus function. Notably, red nucleus functional connectivity with motor-effector networks (somatomotor hand, foot, and mouth) is minimal. Instead, connectivity is strongest to the action-mode and salience networks, which are important for action/cognitive control and reward/motivated behavior. Consistent with this, the red nucleus responds to motor planning more than to actual movement, while also responding to rewards. Our results suggest the human red nucleus implements goal-directed behavior by integrating behavioral valence and action plans instead of serving a pure motor-effector function.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The brainstem was previously thought of as an evolutionarily conserved structure, limited to physiological (e.g., breathing) and basic motor functions (e.g., locomotion)1,2, with the exception of neuromodulatory nuclei (e.g., locus coeruleus)3. The red nucleus is located in the midbrain of the brainstem and first emerged as quadruped precursors began coordinating extremities for movement4,5,6,7,8. The red nucleus includes magno- and parvo-cellular neurons4,9. In quadrupeds, magnocellular red nucleus neurons project down the full length of the spinal cord, forming the rubrospinal tract, which evokes limb movements when stimulated5,10. Parvocellular red nucleus neurons are smaller in diameter and do not project to the spinal cord4. Instead, these neurons participate in the dento-rubro-thalamic tract (DRTT), forming a loop between the cerebral cortex, cerebellum, brainstem, and thalamus4,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21, though the direct red nucleus to thalamus projection has been disputed22,23,24. Projections to the thalamus from the dentate nucleus (passing around the red nucleus) and a possible direct red nucleus projection13, allows for structural connectivity of the red nucleus to identify the ventral intermediate nucleus (VIM)25, a target for neurosurgical treatment (e.g. thalamotomy, deep brain stimulation) of essential tremor and tremor predominant Parkinson’s Disease26,27.

In a striking example of phylogenetic refinement28 from quadrupeds to bipedal humans, the proportion of red nucleus neurons has shifted strongly from magnocellular to parvocellular29,30. For instance, the reptilian red nucleus is almost entirely magnocellular29, the feline red nucleus is approximately 2/3 magnocellular31, and the primate red nucleus is primarily parvocellular4. Furthermore, comparison of the quadrupedal baboon to the bipedal upright gibbon shows that bipedalism coincides with a continued reduction of the rubrospinal tract30. In humans, there is a small rubrospinal tract that only projects to the cervical spinal cord, suggesting that it serves only a minimal role in locomotion32,33. The proportion of cell types in the human red nucleus favors parvocellular so much so that studies of the red nucleus in humans are effectively studies of the parvocellular red nucleus33. Even though human locomotion is supported by the corticospinal tract rather than the rubrospinal tract, the expansion of parvocellular neurons has maintained the red nucleus as one of the largest nuclei in the human midbrain4.

Despite nearly 150 years of research, the functional role of the red nucleus in humans remains unclear4. This represents a major gap in our understanding of a clinically relevant structure and the brainstem. Direct recordings from the parvocellular (in non-human primates)34 and whole red nucleus (in humans)35 show activity is unrelated to free-form movement. Interestingly, there appears to be a relation between the parvocellular red nucleus and goal-directed actions and cognition. In an arm fixation-maintenance study in non-human primates, arm fixation evoked no red nucleus response except when an adaptive arm correction was required36. Human task fMRI studies indicate that the entire red nucleus is minimally activated by simple sensory stimulation and hand movements, relative to larger activations from cognitive tactile discrimination tasks37,38. and tasks involving cognitive control38,39. Rodent electrophysiology recordings during a stop-signal task found trial-to-trial adjustments in the parvocellular red nucleus firing rate that were correlated with movement accuracy and speed, indicating control signals40. Based on these findings, some have argued for parvocellular red nucleus involvement in motor control4, which is a broad concept including motor planning, execution (motor-effector linked), and feedback41,42,43,44,45,46,47. Owing in part to structural connectivity to primary motor cortex48, the adaptive control responses in parvocellular red nucleus40 could support a mechanism for indirect control of movements where motor-effectors in primary motor cortex were modulated by the parvocellular red nucleus based on task goals4. However, support for this hypothesis remains sparse, and it is possible that the human red nucleus has a function within motor control independent of motor-effectors, suggesting a purpose in humans distinct from in quadrupeds.

Resting state functional connectivity (RSFC) has greatly expanded our understanding of human brain organization by revealing large-scale functional networks related to specific functions such as action control, movement and salience49,50,51,52,53. With large amounts of high quality data, it is now possible to identify networks at the individual level, a technique we have termed precision functional mapping (PFM54,55,56,57). Using PFM, we previously mapped the functional connectivity profiles of the thalamus58, cerebellum59, and hippocampus60. This procedure allows researchers to test theories concerning subcortical nuclei, especially when such models argue for connectivity with specific networks. Brainstem fMRI has historically been limited by low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) owing to distance from receiver coils, suboptimal echo times, and unique forms of noise owing to cerebrospinal fluid pulsations39,61,62,63. As a result, fMRI and RSFC of the red nucleus have greatly lagged relative to the rest of the brain, making it difficult to examine its organization in humans.

We have recently shown that the precentral gyrus (i.e., primary motor cortex) is separated into motor-effector specific regions (foot, hand, and mouth) and somato-cognitive action network (SCAN) regions for integrating body movement, goals, and physiology64,65,66,67,68. These SCAN regions are most closely coupled to the action-mode network (AMN, previously called cingulo-opercular network), which governs executive action control49,69,70. While the parvocellular red nucleus has structural connectivity with the precentral gyrus48, it is unclear whether this connectivity is specific to motor-effector or SCAN regions, a question with fundamental interpretive implications. If the human red nucleus is mainly a motor-effector structure, it should exhibit extensive connectivity with effector-specific primary motor regions in the precentral gyrus (i.e. somatomotor hand, food, and/or mouth), and show activity during pure movement tasks. In contrast, stronger functional connectivity with SCAN regions in the precentral gyrus would suggest a role in goal-directed action. Importantly, parvocellular red nucleus structural connectivity extends far beyond the precentral gyrus, including a robust connection with the anterior cingulate cortex48. The anterior cingulate cortex contains many networks, including a large representation of the salience network, which is important for processing reward signals and motivation52,71,72,73,74. The connectivity of the anterior cingulate suggests that the red nucleus may play a role in processes beyond movement, such as reward and motivated behavior, which can be tested through functional connectivity and by examining the red nucleus’s response to reward tasks. Based on structural connectivity alone, it remains unknown with which networks the human red nucleus is functionally connected.

In this work, we determined individual-specific RSFC of the human red nucleus by overcoming the limited low signal-to-noise ratio with denoising approaches. We verified PFM results using group-averaged data from three large fMRI datasets (Human Connectome Project (HCP), Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) study, UK Biobank (UKB); combined sample size of nearly 45,000 participants. We directly tested red nucleus involvement in movement, motor planning, and motivated behavior by analyzing group-averaged task fMRI data from motor and reward tasks (HCP) and meta-analyses (Neurosynth75,76).

Results

Red nucleus is connected with salience and action control networks

Red nucleus (Fig. 1a) functional connectivity was strongest in the dorsal anterior cingulate, medial prefrontal, pre-supplementary motor, insula (especially anterior insula), parietal operculum and anterior prefrontal cortex (Fig. 1). Functional connectivity was clearly organized into networks, especially the AMN (action control; dorsal anterior cingulate cortex, anterior prefrontal cortex, and anterior insula3), and salience network (reward/motivated behavior; anterior cingulate/medial prefrontal cortex and ventral anterior insula52), but not foot/hand/mouth effector-specific motor regions near the central sulcus (Fig. 1; Supplementary Figs. 1–4). Functional connectivity in the central sulcus was strongest with the SCAN regions, which are closely related to the AMN64. The red nucleus was not functionally connected with the default mode network regions in prefrontal cortex or fronto-parietal network regions in the lateral prefrontal cortex and insula. There were no obvious or consistent functional connectivity differences between the left and right red nuclei (Supplementary Fig. 1; Supplementary Fig. 3), nor were the results contingent on the functional connectivity threshold (Supplementary Fig. 2). Additionally, single voxel connectivity maps of the red nucleus indicate that connectivity patterns cannot be explained by partial volume effects as voxels directly outside of the red nucleus have a unique connectivity pattern from voxels within the red nucleus (Supplementary Fig. 5). The observed functional connectivity pattern was also evident in the three large group-averaged datasets totaling ~45,000 participants (Fig. 1c; Supplementary Fig. 1) and in additional, individual-specific red nucleus seed maps (Supplementary Fig. 4).

a Axial (top) and coronal (bottom) display of the right red nucleus (white outline) overlaid on a T2w structural image for subject PFM-Nico. b Resting state functional connectivity (RSFC) seeded from the right red nucleus in an exemplar highly sampled participant with multi-echo independent component analysis (MEICA) denoising (PFM-Nico; 134 min resting-state fMRI). Individual specific functional connectivity map shows strongest 20 percent of cortical vertices. Bar graph quantifies the average connectivity per network. The average connectivity was significantly different from zero for the salience, action-mode (AMN) and dorsal attention (DAN) networks (two-sided t-test against null distribution, *P < 0.05, Bonferroni correction, uncorrected p-value = 0.000999), but was only positive for salience and AMN. c Group-averaged functional connectivity map shows strongest 20 percent of cortical vertices using previously defined split-halves (see ref. 101; n = 1964 participants each) from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) study. For additional participants see Supplementary Figs. 1–4. AMN action-mode, SCAN somato-cognitive action, le-SMN lower-extremity somatomotor, ue-SMN upper-extremity somatomotor, f-SMN face somatomotor, PMN posterior memory, CAN contextual association, DMN default mode, FPN fronto-parietal, DAN dorsal attention, VAN ventral attention.

Red nucleus is functionally connected with the ventral intermediate thalamus

Since the red nucleus is a node along the DRTT, we next examined functional connectivity to subcortical structures. Within the thalamus, red nucleus functional connectivity was strongest with the ventral lateral posterior (VLP) nucleus, encompassing the ventral intermediate nucleus (VIM), which is a major target for treating tremor via thalamotomy and deep brain stimulation27. This was observed at the individual level using a subject specific thalamic segmentation (Fig. 2a; Supplementary Fig. 6) and verified using large group-averaged datasets (Fig. 2b–d; UKB (n = 4000), ABCD study (n = 3928), HCP (n = 812). Interestingly, red nucleus connectivity tended to be stronger to more dorsal sections of the VIM (MNI z coord. > 2 mm). Within cerebellum, red nucleus functional connectivity was primarily with lobule VI (Supplementary Fig. 7).

Top 20% of red nucleus connections for the thalamus (MNI space) for (a), PFM-Nico, (b), ABCD study (n = 3,928), (c), HCP (n = 812), and (d), UKB (n = 4000). Four different axial slices of the thalamus are shown (MNI space) overlaid on the subject’s structural image (panel a only). Thresholding is based on the top 20% of connections for the thalamus. The VIM (ventral intermediate) nucleus of the thalamus defined in an individual subject is shown in panel (a). The nucleus outline based on a dilated probabilistic map using the THOMAS atlas shown in panels (b–d). See Supplementary Fig. 6 for additional participants.

Red nucleus activity for reward and motor control

To further interrogate red nucleus function, we used task fMRI data from the Human Connectome Project (HCP; gambling [Supplementary Fig. 8] and motor [Supplementary Fig. 9]) and automated meta-analysis from Neurosynth for terms: ‘reward’ (Supplementary Fig. 10), ’motor’ (Supplementary Fig. 11a), and ‘motor control’ (Supplementary Fig. 11b). The salience network is typically related to reward/motivated behavior, leading us to predict that the red nucleus would respond to reward related tasks, given its salience network connectivity (Fig. 1 Supplementary Figs. 1–4). Consistent with this, we found that the red nucleus exhibited a larger response to reward than punishment using the HCP gambling task (Fig. 3a). Using automated meta-analysis (Neurosynth), we also found that the red nucleus had a large response to reward (Fig. 3b). In analyzing automated meta-analyses of red nucleus data, we were concerned about partial volume effects given the inherent diversity of processing approaches across the neuroimaging literature. This is a particular concern given the proximity of reward regions like the ventral tegmental area and substantia nigra. Therefore, when performing automated meta-analyses, we accounted for the tissue directly surrounding the red nucleus (peri-nucleus, Supplementary Fig. 12) using an approach that has been previously used to isolate claustrum signals from the insula and putamen77,78 while also accounting for differences in whole brain intensity that varied across contrasts (Supplementary Fig. 13; see Methods). Analyses of motor task fMRI data (HCP) showed that the motor cue indicating upcoming movement triggered a larger response in the red nucleus than actual movement, a classic pre-motor activation pattern (Fig. 3c). When subdividing movement into bilateral hand and foot and tongue movements, we found that the red nucleus response was actually smallest for upper body movements (Supplementary Fig. 14), which is one of the few parts of the human body that can be directly influenced by red nucleus descending projections32,33. Consistent with these task fMRI findings, automated meta-analyses showed red nucleus activations to ‘motor control’ (Fig. 3d), but no activations in the ‘motor’ contrast (Supplementary Fig. 15).

a Red nucleus activation from the gambling task of Human Connectome Project (HCP) reward (left, filled light gray) and punishment (right, unfilled) contrasts (paired t-test; t = 4.87, confidence interval = [0.046 0.11], cohen’s d d = 0.15, df = 1080, p = 1.29 × 10-6). b Automated meta-analysis average for term ‘reward’ for the red nucleus (left, stripe pattern) the region surrounding the red nucleus (peri-nucleus, middle, circle pattern) and whole brain (right, crosshatch pattern). c Red nucleus activation from the motor task of HCP motor cue (left, filled dark grey) and average movement (right, unfilled) contrasts (paired t-test; t = 4.58, confidence interval = [0.04 0.1], cohen’s d d = 0.14, df=1079, p = 5.22 × 10-6). d Automated meta-analysis average for term ‘motor control’ for the red nucleus (left, stripe pattern) the region surrounding the red nucleus (peri-nucleus, middle, circle pattern) and whole brain (right, crosshatch pattern). Boxplot displays interquartile range, median (horizontal black line), mean (red circle), and 95% confidence interval (black error bars).

Red nucleus is not functionally connected with effector-specific motor cortex

Treating the red nucleus as a homogeneous functional connectivity seed could potentially obscure a subregion of red nucleus with motor-effector connectivity. To further evaluate the hypothesis that red nucleus should have motor-effector network connectivity, we applied a winner-take-all approach to assign red nucleus voxels to networks based on cortical connectivity58,60. We found that almost no voxels had preferential motor-effector specific connectivity (somatomotor foot, hand, and mouth; Fig. 4, hollow triangles) in large group-averaged (Fig. 4, left) and in individual-specific (Fig. 4, right) datasets. Most voxels were assigned to either AMN, salience, or SCAN (Fig. 4, filled circles).

Red nucleus voxels were assigned to networks using winner-take-all logic. The percentage of red nucleus voxels assigned to action related networks (salience network, AMN, or SCAN) is shown in filled circles and the percent assigned to any of the three motor-effector networks (lower-extremity somatomotor, upper-extremity somatomotor, and face somatomotor) is shown in hollow triangles. The left three columns show group-averaged data; the right five columns showing data from highly sampled individuals. AMN (action-mode), SCAN (somato-cognitive action).

Distinct ventral-lateral (salience) and dorsal-medial (action-mode) subdivisions

Winner-take-all assignments identified two sub-populations within the red nucleus, one connected to the salience network and one to the AMN/SCAN (Supplementary Fig. 16a). To delineate red nucleus subdivisions, we used agglomerative hierarchical clustering to group voxels based on functional connectivity with cortical networks58,79. These analyses identified a dorsal-medial and ventral-lateral division of the red nucleus (Fig. 5a, Supplementary Figs. 16, 17, Supplementary Table 1). Comparing the functional connectivity of these two sub-divisions (ventral-lateral [salience preference] – dorsal-medial [AMN preference]60) demonstrated that the ventral-lateral division had stronger connectivity with the salience and parietal memory networks60,80, while the dorsal-medial red nucleus had stronger connectivity with the AMN and SCAN regions within the precentral gyrus (Fig. 5b, c, Supplementary Fig. 17a). Binarizing the preference for Salience vs. AMN connectivity sufficed to identify the two red nucleus partitions (AUC > 0.9). In support of this dorsal-medial/ventral-lateral partition of red nucleus, we also examined the correlation between red nucleus connectivity and specific cortical networks, revealing an obvious divide in network connectivity between AMN and salience (Fig. 5c, d, Supplementary Fig. 16b, Supplementary Fig. 17d). Neither subdivision displayed strong effector-specific motor connectivity relative to SCAN. As was true of the entire red nucleus, dorsal-medial red nucleus precentral gyrus connectivity was strongest with SCAN regions (Fig. 5b, c). Preference for salience vs. AMN in group average datasets similarly identified a ventral-lateral (salience) and dorsal-medial (AMN/SCAN) divisions, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 16b, Supplementary Fig. 17d, Supplementary Fig. 18).

a Anatomical display of dorsal-medial (hatched) and ventral-lateral (no fill) red nucleus subdivisions in an exemplar participant (PFM-Nico) overlaid on the same participant’s T2w image. b Strongest 20 percent of cortical RSFC for ventral-lateral (left) and dorsal-medial (middle) red nucleus subdivisions. The right most image shows the difference map between these two connectivity maps. Note greater ventral-lateral connectivity in red and greater dorsal-medial in blue. c Average cortical RSFC organized by network for dorsal-medial (hatched) and ventral-lateral (no fill) subdivisions. d Similarity (r) in network connectivity for each red nucleus voxel grouped into dorsal-medial and ventral-lateral divisions. For additional subjects/analyses see Supplementary Figs. 16–19. AMN (action-mode) SCAN (somato-cognitive action), le-SMN (lower-extremity somatomotor), ue-SMN (upper-extremity somatomotor), f-SMN (face somatomotor), PMN (posterior memory), CAN (contextual association), DMN (default mode), FPN (fronto-parietal), DAN (dorsal attention), VAN (ventral attention); Resting state functional connectivity (RSFC).

Based on the preceding results, we used salience-favoring (ventral-lateral) and AMN-favoring (dorsal-medial) partitions of the red nucleus as separate seeds to examine subcortical connectivity. The ventral-lateral (salience) partition was functionally connected with the VIM (Supplementary Fig. 19a). The ventral-lateral partition had peak cerebellar connectivity in lobule VI (Supplementary Fig. 19a). The dorsal-medial (AMN) partition was functionally connected with the mediodorsal nucleus of the thalamus (Supplementary Fig. 19b) as well as cerebellar lobule VIII, especially in VIIIb (Supplementary Fig. 19b). When analyzing these partitions in task data from the HCP, we found that both had a larger response to motor cue (indicating upcoming movement) than to actual movement, with the dorsal-medial (AMN) partition having an even larger response that the ventral-lateral (salience) division (Supplementary Fig. 20).

Discussion

The red nucleus is functionally connected with action (action-mode) and motivated behavior (salience) networks, but not motor-effector networks (somatomotor foot, hand, and mouth). In fact, the red nucleus displayed no, or negative functional connectivity with motor-effector networks. Moreover, motor cortex connectivity was restricted to SCAN regions64. This is in stark contrast to previous literature in quadrupedal organisms showing red nucleus is a motor-effector nucleus that controls muscle movements through spinal projections10. These observations, combined with the reduction in the rubrospinal pathway in humans32,33, suggest that in striking contrast to other species10, the primary function of the human red nucleus is not exclusive to controlling movements. The evolutionary principle of exaptation, where a trait serves a new function other than its original purpose, may apply. The original function of the red nucleus was to coordinate extremity movement for locomotion. However, emergence of the pyramidal system and bipedalism made the rubrospinal pathway outdated for locomotion7. Thus, instead of gradually disappearing, the red nucleus appears to have been repurposed from a motor-effector nucleus controlling muscles through a spinal projection to involvement in higher-level control and potentially integration of action and motivated behavior.

Multiple non-human primate tract tracing studies have shown that the red nucleus is structurally connected with the motor cortex and that parts of the primate red nucleus are active during some motor tasks36,48,81,82. Accordingly, it was somewhat surprising that human red nucleus functional connectivity to motor-effector specific regions of motor cortex was small or negative. This results conflicts with certain motor control models that position the red nucleus (and potentially the entire DRTT) as a system for fine control of motor-effector circuits in the cerebral cortex. Instead, the observed functional connectivity with SCAN is more consistent with the original role of the red nucleus in whole body coordination, a process involving the SCAN64. It is worth emphasizing that regardless of the disputed direct projection between the red nucleus and the thalamus22, the red nucleus is widely agreed to receive dentate nucleus inputs while also having projections that indirectly influence the cerebellum4. These considerations imply that re-analyses of non-human primate red nucleus tract tracing studies may show preferential connectivity of the red nucleus with SCAN homologues rather than motor-effector regions.

It remains an open question whether the salience and AMN subdivisions of the red nucleus are strictly parallel or whether they might support the integration of reward/motivated-behaviors (hence salience network connectivity and reward activation) and action-control (hence AMN connectivity and motor control and motor cue activation), allowing action plans to be regulated by motivation, even in the brainstem. This general framework is consistent with the emerging perspectives that the brain produces specific behavior in the context of motivated states83,84. The red nucleus may coordinate and rapidly adapt action execution based on changing salience information. In either scenario, the present results suggest that human action is controlled by a repurposed motor nucleus. This perspective is consistent with the view that cognition/planning and movement are fundamentally linked85,86.

The observation that red nucleus function seems to have shifted its role from quadrupedal locomotion to reward and action processing has broader implications. The brainstem has often been conceptualized as participating in two rigid hierarchies: a top-down control circuit that passively receives and transmits top-down signals originating from the cerebral cortex; and a bottom-up sensory circuit that passively receives and transmits sensory signals originating from the periphery. However, tract tracing results demonstrating limited connectivity between the red nucleus and spinal cord indicate that this simplified view does not apply. We speculate that the dominant representation of two functional networks in the red nucleus is consistent with the view that neural networks are an organizing principle throughout the brain, and not limited to the cerebral cortex, in keeping with recent findings and perspectives87,88,89,90. How specific networks interact with the body91,92 carries implications for studies of affect and motivated behavior, and is a topic that warrants further investigation.

We are aware of fewer than a half dozen studies investigating the red nucleus as a target for therapeutic DBS. One group developed an electrophysiologic profile of the red nucleus with the goal of avoiding this structure93 as stimulation of the third cranial nerve (which passes through the RN) can lead to ocular disturbances35,94. This proximity to oculomotor nuclei/axons may help to explain red nucleus functional connectivity with visual cortex (Fig. 1b), though the small voxel sizes used (2 mm isotropic for PFM-Nico) and red nucleus constrained smoothing likely mitigate partial volume effects (Supplementary Fig. 5). Interestingly, insertion of a macro-electrode into the red nucleus transiently reduced postural tremor in a single patient35. Our findings suggest that using the functional connectivity of each red nucleus subdivision could aid in the localization of thalamic stimulation sites like the VIM or mediodorsal thalamus for treatment of tremor or pain95 respectively.

The absence of pure motor task activity and motor-effector functional connectivity argues against the human red nucleus being a motor-effector nucleus, directly influencing motor-effector neurons in M1. Therefore, the evolutionary process of exaptation may have given the red nucleus a new purpose as a node within the dento-rubral thalamic tract (DRTT), a major loop connecting the cerebral cortex, thalamus, brainstem, and cerebellum4,12. Neural loops serve as valuable machinery for action feedback and integration96. We speculate that the red nucleus is ideally positioned to incorporate motivated behavior signals (e.g., experienced reward or anticipated reward) into motor planning information moving through the DRTT. This would allow for reward signals to be rapidly and dynamically incorporated into motor planning during ongoing goal-oriented behavior, helping to guide optimal action selection and its online adjustment.

Methods

Washington University participant for precision functional mapping (PFM-Nico)

The participant was 37 year old healthy adult male used previously in both the Midnight Scan Club (ref. 55; MSC02) and limb immobilization studies (ref. 97; SIC01), and the senior investigator of this current project (N.U.F.D.). This participant is referred to as precision functional mapping (PFM)-Nico. See below section: Preprocessing of PFM-Nico for additional scanning and preprocessing information. PFM-Nico data collection was approved by the Washington University School of Medicine Human Studies Committee and Institutional Review Board.

Cornell University participants for precision functional mapping

Four healthy adult participants (ages 29, 38, 24, and 31; all male) from a previously published study were used57. These participants are referred to as participant 1–4 in the manuscript. The previous study was approved by the Weill Cornell Medicine Instructional Review Board and each participant provided written informed consent. For additional details please see ref. 57.

UK Biobank (UKB)

We downloaded the group-averaged weighted eigenvectors from an initial group of 4100 UKB participants aged 40-69 years (53% female) with 6-minute resting-state scans (https://www.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/ukbiobank/). Details of the acquisition and processing can be found at https://biobank.ctsu.ox.ac.uk/crystal/ukb/docs/brain_mri.pdf98. This eigenvector file was mapped to the Conte69 surface template99 using the ribbon-constrained method in Connectome Workbench100, following which the eigenvector time courses were cross-correlated.

Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study

3928 9-10-year-old participants (51% female), with at least 8 min of low-motion resting state data were used. In cases (e.g. Figure 1c) these subjects were split into two equal halves matched across site location, age, sex, ethnicity, grade, highest level of parental education, handedness, combined family income, and prior exposure to anesthesia101. Data processing was done with the ABCD-BIDS pipeline (NDA collection 3165; https://github.com/DCAN-Labs/abcd-hcp-pipeline). For additional details see:101,102,103.

Human Connectome Project (HCP)

The group-averaged dense functional connectivity matrix for the HCP 1200 participants release, consisting of functional connectivity data for all 812 participants aged 22–35 years (410 female) with 60 min of resting-state fMRI, was downloaded from https://db.humanconnectome.org. Task data from HCP was also from the 1200 participants release used for resting state data and featured 1085 participants for the gambling task and 1081 for the motor task downloaded from https://db.humanconnectome.org. For more information on the acquisition and processing see:100,104,105,106.

Automated Meta-Analytic maps from Neurosynth

Automated meta-analytic maps were downloaded from neurosynth75,76 from https://github.com/neurosynth/neurosynth-data. In total, 14,371 studies were included.

Preprocessing of PFM-Nico

PFM-Nico refers to a single participant (N.U.F.D) collected at Washington University in St. Louis. Imaging was performed using a Siemens TRIO 3 T MRI scanner. Structural MRI included four T1-weighted images (sagittal acquisition, 224 slices, 0.8 mm isotropic resolution, TR = 2500 ms, TE = 2.9 ms, flip angle = 8°) and four T2-weigthed images (sagittal acquisition, 224 slices, 0.8 mm isotropic resolution, TR = 3200 ms, TE = 479 ms, flip angle = 120°). Structural data were processed using previously described methods97. Briefly, T1 and T2 weighted images were corrected for field inhomogeneity using FSL Fast107, averaged separately, and then aligned to Talairach space using 4dfp tools (https://readthedocs.org/projects/4dfp/). All structural images were inspected for registration errors especially in the brainstem. Functional blood oxygenation level-dependent (BOLD) images were acquired using a multi-echo multi-band gradient-echo sequence consisting of nine 15-minute runs (72 slices, 2 mm isotropic resolution, TR = 1761 ms, TE = [14.20, 38.93, 63.66, 88.39, 113.12 ms], flip angle = 68°, multi-band acceleration factor = 6). In addition, 3 noise frames were acquired per run for noise reduction with distribution corrected (NORDIC) PCA, which was used to reduce thermal noise in functional data108. fMRI preprocessing used previously published methods97,109. This included slice timing correction through temporal interpolation, rigid-body correction for head followed by optimal-echo combination and denoising (described below) and finally NORDIC thermal denoising108. Atlas transformation was accomplished by computing a composition of 1) native space mean functional image to T2w space, T2w space to T1w space, and finally T1w space to template space.

Optimal combination of multi-echo data and multi-echo independent component analysis (MEICA) denoising were performed using the tedana package version 0.0.11110,111,112. To promote reproducibility, we copy the automated methods description writeup as follows. TE-dependence analysis was performed on input data. An initial mask was generated from the first echo using nilearn’s compute_epi_mask function. An adaptive mask was then generated, in which each voxel’s value reflects the number of echoes with ‘good’ data. A two-stage masking procedure was applied, in which a liberal mask (including voxels with good data in at least the first echo) was used for optimal combination, T2*/S0 estimation, and denoising, while a more conservative mask (restricted to voxels with good data in at least the first three echoes) was used for the component classification procedure. A monoexponential model was fit to the data at each voxel using log-linear regression in order to estimate T2* and S0 maps. For each voxel, the value from the adaptive mask was used to determine which echoes would be used to estimate T2* and S0. Multi-echo data were then optimally combined using the T2* combination method113.

Principal component analysis based on the PCA component estimation with a Moving Average (stationary Gaussian) process114 was applied to the optimally combined data for dimensionality reduction. The following metrics were calculated: kappa, rho, countnoise, countsigFT2, countsigFS0, dice_FT2, dice_FS0, signal-noise_t, variance explained, normalized variance explained, d_table_score. Kappa (kappa) and Rho (rho) were calculated as measures of TE-dependence and TE-independence, respectively. A t-test was performed between the distributions of T2*-model F-statistics associated with clusters (i.e., signal) and non-cluster voxels (i.e., noise) to generate a t-statistic (metric signal-noise_z) and p-value (metric signal-noise_p) measuring relative association of the component to signal over noise. The number of significant voxels not from clusters was calculated for each component. Independent component analysis was then used to decompose the dimensionally reduced dataset. The following metrics were calculated: kappa, rho, countnoise, countsigFT2, countsigFS0, dice_FT2, dice_FS0, signal-noise_t, variance explained, normalized variance explained, d_table_score. Kappa (kappa) and Rho (rho) were calculated as measures of TE-dependence and TE-independence, respectively. A t-test was performed between the distributions of T2*-model F-statistics associated with clusters (i.e., signal) and non-cluster voxels (i.e., noise) to generate a t-statistic (metric signal-noise_z) and p-value (metric signal-noise_p) measuring relative association of the component to signal over noise. The number of significant voxels not from clusters was calculated for each component. Next, component selection was performed to identify BOLD (TE-dependent), non-BOLD (TE-independent), and uncertain (low-variance) components using the Kundu decision tree (v2.5112). This workflow used numpy115, scipy116, pandas117, scikit-learn118, nilearn, and nibabel119. This workflow also used the Dice similarity index120,121.

For every run of BOLD data, we manually inspected the noise/signal classification from MEICA and adjusted classification where needed. This strategy of manual inspection is viable in the context of small sample studies like ours, and is a major strength of the PFM approach. Only components classified as signal were used for all analyses. Based on the 6 rigid body parameters derived via retrospective motion correction, we calculated frame-wise displacement (FD122). Motion parameters were low-pass filtered (threshold set at 0.1 Hz) before FD computation so as to reduce the impact of respiratory artifact of estimates of head motion123. To identify high motion frames, we set a threshold of 0.08 mm on the FD vector. Global signal was calculated as the average of all voxels within a brain mask. Following optimal combination and MEICA, data underwent temporal bandpass filtering with frequencies between 0.005 Hz and 0.1 Hz being retained. Global signal and its first derivative constituted the only nuisance regressors. Following noise correction, cortical data were projected onto a surface using a previously described approach55. Data were smoothed with a geodesic 2D (surface) or Euclidean 3D (volumetric) Gaussian kernel of σ = 2.55 mm. Volumetric smoothing was done within each subvolume including bilateral red nuclei (described in manual tracing of the red nucleus).

Improving brainstem signal-to-noise ratio

The brainstem is the most difficult part of the brain to functionally neuroimage. Distance from the receiver coils inherently makes the SNR lower there than in the cerebral cortex. Additionally, optimal echo times are different in the brainstem (and vary across the brainstem) and cerebral cortex, in part owing to high concentration of iron. Given that most studies optimize scanning parameters for the cortex, common scanning parameters are poorly suited for the brainstem. Also, we encountered sources of noise at the individual level that were difficult to characterize with standard denoising with motion and anatomical regressors. In total, these limitations with current brainstem imaging required a specialized denoising strategy. The first part of this strategy was implementation of a recently developed thermal denoising approach called NORDIC108, which greatly reduces unstructured noise. By acquiring multi-echo data and employing optimal combinations of echoes on a voxelwise manner, we were able to have an optimized echo time for both the cerebral cortex and brainstem. Also, MEICA allows for a substantial improvement in SNR57. We utilized MEICA and manually modified noise components on a run-by-run level, taking care to remove any brainstem specific artifactual components. This procedure would be excessively burdensome for large sample size studies but is viable in a PFM framework. Finally, we collected a far greater amount of data individual participant fMRI data than is usual, allowing for a ‘brute force’ approach to SNR improvement. Where these denoising strategies did not apply, i.e., in group averaged and single echo datasets, we relied on massive sample sizes to improve SNR. These measures mitigated the most pressing issue in brainstem functional imaging, namely, the low SNR. The strategies employed here demonstrate the feasibility of brainstem neuroimaging and can be extended to investigate other clinically relevant structures like the substantia nigra and periaqueductal grey.

Defining the red nucleus

Unlike many brainstem nuclei, the red nucleus is clearly visible on T2-weighted images as a region of low signal intensity (Fig. 1a). Such regions were manually segmented on T2-weighted native space images (Fig. 1a) by a single experimenter (S.R.K. with oversight from N.U.F.D) and transformed to MNI space for subsequent analyses. Publicly available brainstem atlases were used as a reference for the red nucleus to assist in manual drawing (brainstem navigator atlas https://www.nitrc.org/projects/brainstemnavig124). We did not exclusively use the brainstem navigator atlas to define the red nucleus in part owing to possible image registration errors between anatomical data and template space. In a situation where the red nucleus was exclusively defined using the template space brainstem navigator atlas, any registration errors between the template (which the brainstem navigator atlas is registered to), and anatomical data would necessarily cause mismatch between the brainstem navigator red nucleus region of interest and the true red nucleus in the participant’s data. As a result, the ultimate functional connectivity results would be erroneous to a degree proportional to the magnitude of registration error. This problem is avoided when the red nucleus is manually defined based on each participant’s anatomical data, because even if registration errors occur between the anatomical data and the template, the red nucleus will still be correctly defined so long as it was accurately drawn originally. For group average datasets, the red nucleus was again hand drawn but on a high resolution T2-weighted MNI template image125.

Cortical network identification

The Infomap algorithm125 (https://www.mapequation.org/) was used to assign vertices to communities, and the resulting communities were then assigned a network identity based on similarity to known group-average networks. The consensus network assignment, computed by aggregating across thresholds, was used as the cortical resting state networks (see Supplementary Fig. 2 for example assignments). The original 17 networks set described in MSC55 was recently amended to account for the SCAN64.

Red nucleus functional connectivity

For PFM and ABCD data, we averaged the timeseries of red nucleus voxels to create a red nucleus timeseries and correlated this with all other grayordinates. For HCP and UKB data, we instead averaged over rows in the dense connectivity matrix corresponding to the red nucleus. When computing the functional connectivity of red nucleus subdivisions, we simply repeated these procedures, but for the subdivision instead of the whole red nucleus.

Task analysis of red nucleus

Average red nucleus response to HCP gambling and motor contrasts was calculated for each available participant. We used a one sample t-test to test for significance of the reward versus punishment contrast and motor cue versus motor average contrast that was directly downloaded from https://db.humanconnectome.org. For specific motor-effects (i.e. left hand, right foot etc.) versus the motor cue effect (e.g. Supplementary Fig. 14), we conducted a paired t-test between the participant’s red nucleus motor cue response and each movement contrast. The analysis of Neurosynth meta-analytic contrasts was somewhat more challenging. Relative to all other datasets used, Neurosynth features a staggering amount of variability due to the inherent heterogeneity in functional neuroimaging research, including differences in scanner, scanner sequence, preprocessing and analysis. This made us especially concerned about the risk of partial volume effects. Qualitatively examining brainstem values in Neurosynth, we noticed that there were some meta-analytic contrasts that appeared anatomically disperse, potentially owing to partial volume. In order to mitigate these effects, we relied on a modified version of Small Region Confound Correction78 which was originally developed to isolate claustrum signals from surrounding regions by regressing surrounding tissue from the region of interest. The surrounding areas are defined by dilating the region of interest to a large degree, dilating it to a small degree, and then finally subtracting the smaller dilation from the larger. This produces a surrounding area that matches the shape of the region of interest, but does not include the region of interest. In the case of the red nucleus, we dilated bilateral nuclei by 4 mm, and then by 2 mm. The 2 mm dilation was then subtracted from the 4 mm dilation creating what we refer to here as a peri-nucleus given that it is around the red nucleus (see Supplementary Fig. 12 for an illustration). By comparing the red nucleus with the peri-nucleus we are able to ensure that the red nucleus meta-analytic value is not simply a result of partial volume effects from nearby regions like the ventral tegmental area of substantia nigra, which is especially important for reward related analysis. One additional concern when using Neurosynth data is that the average intensity of meta-analytic contrasts varies greatly across contrasts for the whole brain (Supplementary Fig. 13a) and in the areas adjacent to the red nucleus (Supplementary Fig. 13b). This meant that comparisons across contrasts are challenging as the average intensity is variable. Consistent with this, we observed a small to moderate correlation between the red nucleus (Supplementary Fig. 13c) and peri-nucleus (Supplementary Fig. 13d) meta-analytic contrast intensity with the average global meta-analytic contrast intensity. To ensure that this intensity difference was not misleading our interpretation, we always display Neurosynth results with the whole brain average for that specific contrast. Due to the variably smoothed nature of neurosynth data, we did not compare differences in red nucleus subdivisions for meta-analytic contrasts. However, we did compare the cue versus average movement contrast from the HCP motor task and the reward versus punishment contrast from the HCP gambling task based in the red nucleus subdivisions.

Winner-take-all analysis of red nucleus voxels

We used a previously established approach for assigning red nucleus voxels to bilateral cortical networks60. Described briefly, a voxel was assigned to the network that it had the largest correlation to, so long as that correlation was greater than zero. We excluded three sensory networks, two visual and one auditory, from possible assignment, because the red nucleus is not believed to be involved in these processes, and because potential assignment to these three networks would be likely artifactual potentially owing to partial volume effects with the third cranial nerve which passes through the red nucleus. Additionally, inconsistent and small Infomap cortical assignment to the anterior and posterior medial temporal networks led us to exclude these two networks as well. In total, there were 13 networks that red nucleus voxels could be assigned. These networks with associated colors for figures are as follows: AMN (action-mode network; purple); SCAN (somato-cognitive action network; mauve), le-SMN (lower-extremity somatomotor network; forest green), ue-SMN (upper-extremity somatomotor network; cyan), f-SMN (face somatomotor network; orange), PMN (posterior memory network; blue), CAN (contextual association network; white), DMN (default mode network; red), FPN (fronto-parietal network; yellow), DAN (dorsal attention network; neon green), VAN (ventral attention network; teal).

Clustering

Clustering of the red nucleus was based on cortical connectivity, specifically the correlation between each red nucleus voxel and the 13 bilateral resting state networks similar to previous clustering approaches to other subcortical structures58. We used hierarchical clustering on the Euclidean distance between cortical connectivity strength with Ward’s method126,127. Using the NBclust R package we assessed clustering performance with the number of clusters ranging from 2 to 13 using more than 20 metrics128. For each number of clusters, a score for all clustering metrics was computed, and cluster performance was ranked (e.g. the number of clusters with the largest silhouette index scored a rank of 1). For each metric, a number of clusters “won” when it had the best performance for that specific clustering metric. The number of clusters chosen was based on a majority rule where the number of clusters with the most total victories (first place for each metric) was determined to be the best overall.

Thalamus segmentation

The Thalamus-Optimized Multi-Atlas Segmentation (THOMAS v 2.1)129 is a method for identification of nuclei, particularly the ventral intermediate nucleus that has been colocalized with the segment labelled the ventral part of the Ventro-Lateral-Posterior nucleus130.

To segment the thalamic nuclei on our precision mapping participant, we used the hips_thomas.csh function from the version 2.1 that has been validated for use of T1 acquisition only131 and that is available on docker (https://github.com/thalamicseg/hipsthomasdocker). We used the average T1 acquisition that has been produced for the registration of all functional data. For group averaged data we used an MNI space transformation of a probabilistic THOMAS segmentation (https://zenodo.org/record/5499504) with 2 millimeters of dilatation.

Projecting to the cerebellum

Cerebellar connectivity values were mapped onto a cerebellar flat map with the SUIT toolbox132 (https://www.diedrichsenlab.org/imaging/suit.htm).

Statistics

We used a rotation-based null model to test if red nucleus connectivity was selective for networks or random (e.g. Figure 2b). In this approach, cortical resting state networks were rotated by a random amount around a spherical expansion of the cortical surface 1000 times133. For each rotation, we calculated the measure of interest (e.g. red nucleus connectivity strength to the rotated network). A p-value was calculated by comparing the true value against the values obtained through random rotations. When multiple comparisons across networks was performed, a Bonferroni correction for network number was used to control the false positive rate.

Visualization

The distribution of functional connectivity values differs based on dataset, in part owing to different denoising decisions. Therefore, direct numerical comparisons across datasets is not appropriate. Thus, to facilitate comparison, in almost all figures, RSFC values were thresholded to be the top 20 percent of the given image. Supplementary Fig. 2 demonstrates that this threshold does not obscure red nucleus connectivity. In group averaged subcortical data we noticed a pattern in which the edges of structures (e.g. thalamus) were the most likely to contain extreme values. Even an inspection of dense connectivity matrices shows an obvious effect of extreme values around the edge of volume structures. It is not entirely clear why this is the case. One possibility is that sub-volume constrained averaging may cause edge voxels to be noisier because they are averaged with fewer voxels, thus promoting extreme values. Thus, we excluded edge voxels from the thalamus exclusively for group average datasets. We accomplished this by minimally eroding the thalamus ROI by 3 mm. When examining Cornell data in the thalamus, we noticed that red nucleus signal was being smoothed into the ventral thalamus, leading to extremely large and erroneous connectivity values. To address this, we masked out thalamus voxels that were included in a 5 mm dilation of the bilateral red nucleus.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

ABCD, HCP, and UKB data are publicly available with download information provided. Raw data for PFM-Nico is available for download: https://openneuro.org/datasets/ds005926. For Cornell data (P1-P4) please contact Charles J. Lynch (cjl2007@med.cornell.edu). Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Baizer, J. Unique Features of the Human Brainstem and Cerebellum. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 8 https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/humanneuroscience/articles/10.3389/fnhum.2014.00202/full (2014).

Baizer, J. S., Webster, C. J. & Witelson, S. F. Individual variability in the size and organization of the human arcuate nucleus of the medulla. Brain Struct. Funct. 227, 159–176 (2022).

Sara, S. J. The locus coeruleus and noradrenergic modulation of cognition. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 10, 211–223 (2009).

Basile, G. A. et al. Red nucleus structure and function: from anatomy to clinical neurosciences. Brain Struct. Funct. 226, 69–91 (2021).

De Lange, S. J. The red nucleus in reptiles. K. Ned. Akad. Van. Wet. Proc. Ser. B Phys. Sci. 14, 1082–1090 (1912).

Padel, Y. Magnocellular and parvocellular red nuclei. Anatomico-functional aspects and relations with the cerebellum and other nerve centres]. Rev. Neurol. (Paris) 149, 703–715 (1993).

Ten Donkelaar, H. J. Evolution of the red nucleus and rubrospinal tract. Behav. Brain Res. 28, 9–20 (1988).

Padel, Y., Bourbonnais, D. & Sybirska, E. A new pathway from primary afferents to the red nucleus. Neurosci. Lett. 64, 75–80 (1986).

Hatschek, R. Zur vergleichenden Anatomie des Nucleus ruber tegmenti. Arb. Neurol. Inst. Univ. Wien. 15, 89–136 (1907).

Ghez, C. Input-output relations of the red nucleus in the cat. Brain Res. 98, 93–108 (1975).

Martínez‐Marcos, A., Lanuza, E., Font, C. & Martínez‐García, F. Afferents to the red nucleus in the lizard Podarcis hispanica: Putative pathways for visuomotor integration. J. Comp. Neurol. 411, 35–55 (1999).

Cacciola, A. et al. The cortico-rubral and cerebello-rubral pathways are topographically organized within the human red nucleus. Sci. Rep. 9, 12117 (2019).

Roger, M. & Cadusseau, J. Anatomical evidence of a reciprocal connection between the posterior thalamic nucleus and the parvocellular division of the red nucleus in the rat. A combined retrograde and anterograde study. Neuroscience 21, 573–583 (1987).

Lapresle, J. & Hamida, M. B. The dentato-olivary pathway: somatotopic relationship between the dentate nucleus and the contralateral inferior olive. Arch. Neurol. 22, 135–143 (1970).

Flumerfelt, B. A., Otabe, S. & Courville, J. Distinct projections to the red nucleus from the dentate and interposed nuclei in the monkey. Brain Res. 50, 408–414 (1973).

Bertino, S. et al. Ventral intermediate nucleus structural connectivity-derived segmentation: anatomical reliability and variability. NeuroImage 243, 118519 (2021).

Carpenter, M. B. A study of the red nucleus in the rhesus monkey. Anatomic degenerations and physiologic effects resulting from localized lesions of the red nucleus. J. Comp. Neurol. 105, 195–249 (1956).

Miller, R. A. & Strominger, N. L. Efferent connections of the red nucleus in the brainstem and spinal cord of the rhesus monkey. J. Comp. Neurol. 152, 327–345 (1973).

Milardi, D. et al. Red nucleus connectivity as revealed by constrained spherical deconvolution tractography. Neurosci. Lett. 626, 68–73 (2016).

Petersen, K. J. et al. Structural and functional connectivity of the nondecussating dentato-rubro-thalamic tract. NeuroImage 176, 364–371 (2018).

Tacyildiz, A. E. et al. Dentate Nucleus: Connectivity-Based Anatomic Parcellation Based on Superior Cerebellar Peduncle Projections. World Neurosurg. 152, e408–e428 (2021).

Edwards, S. B. The ascending and descending projections of the red nucleus in the cat: an experimental study using an autoradiographic tracing method. Brain Res. 48, 45–63 (1972).

Hopkins, D. A. & Lawrence, D. G. On the absence of a rubrothalamic projection in theb monkey with observations on some ascending mesencephalic projection. J. Comp. Neurol. 161, 269–293 (1975).

Miller, L. E. & Gibson, A. R. Red nucleus. in Encyclopedia of neuroscience 55–62 (Elsevier Ltd, 2009).

Nowacki, A. et al. Probabilistic mapping reveals optimal stimulation site in essential tremor. Ann. Neurol. 91, 602–612 (2022).

Haubenberger, D. & Hallett, M. Essential Tremor. N. Engl. J. Med. 378, 1802–1810 (2018).

Schlaier, J. et al. Deep Brain Stimulation for Essential Tremor: Targeting the Dentato-Rubro-Thalamic Tract? Neuromodulation Technol. Neural Interface 18, 105–112 (2015).

Cisek, P. Resynthesizing behavior through phylogenetic refinement. Atten. Percept. Psychophys. 81, 2265–2287 (2019).

Massion, J. The mammalian red nucleus. Physiol. Rev. 47, 383–436 (1967).

Padel, Y., Angaut, P., Massion, J. & Sedan, R. Comparative study of the posterior red nucleus in baboons and gibbons. J. Comp. Neurol. 202, 421–438 (1981).

Huisman, A. M., Kuypers, H. G. J. M. & Verburgh, C. A. Differences in collateralization of the descending spinal pathways from red nucleus and other brain stem cell groups in cat and monkey. in Progress in Brain Research (eds. Kuypers, H. G. J. M. & Martin, G. F.) vol. 57 185–217 (Elsevier, 1982).

Massion, J. Red nucleus: past and future. Behav. Brain Res. 28, 1–8 (1988).

Nathan, P. W. & Smith, M. C. The rubrospinal and central tegmental tracts in man. Brain J. Neurol. 105, 223–269 (1982).

Kennedy, P. R., Gibson, A. R. & Houk, J. C. Functional and anatomic differentiation between parvicellular and magnocellular regions of red nucleus in the monkey. Brain Res. 364, 124–136 (1986).

Lefranc, M. et al. Targeting the Red Nucleus for Cerebellar Tremor. Cerebellum 13, 372–377 (2014).

Herter, T. M., Takei, T., Munoz, D. P. & Scott, S. H. Neurons in red nucleus and primary motor cortex exhibit similar responses to mechanical perturbations applied to the upper-limb during posture. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 9, 29 (2015).

Liu, Y. et al. The human red nucleus and lateral cerebellum in supporting roles for sensory information processing. Hum. Brain Mapp. 10, 147–159 (2000).

Sung, Y.-W., Kiyama, S., Choi, U.-S. & Ogawa, S. Involvement of the intrinsic functional network of the red nucleus in complex behavioral processing. Cereb. Cortex Commun. 3, tgac037 (2022).

de Hollander, G., Keuken, M. C., van der Zwaag, W., Forstmann, B. U. & Trampel, R. Comparing functional MRI protocols for small, iron‐rich basal ganglia nuclei such as the subthalamic nucleus at 7 T and 3 T. Hum. Brain Mapp. 38, 3226–3248 (2017).

Brockett, A. T., Hricz, N. W., Tennyson, S. S., Bryden, D. W. & Roesch, M. R. Neural Signals in Red Nucleus during Reactive and Proactive Adjustments in Behavior. J. Neurosci. 40, 4715–4726 (2020).

Craighero, L., Fadiga, L., Rizzolatti, G. & Umiltà, C. Action for perception: a motor-visual attentional effect. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 25, 1673 (1999).

Fajen, B. R. Introduction to Section on Perception and Action. in Progress in Motor Control: A Multidisciplinary Perspective (ed. Sternad, D.) 263–272 (Springer US, Boston, MA, 2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-77064-2_13.

Kalaska, J. F. From Intention to Action: Motor Cortex and the Control of Reaching Movements. in Progress in Motor Control: A Multidisciplinary Perspective (ed. Sternad, D.) 139–178 (Springer US, Boston, MA, 2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-77064-2_8.

Latash, M. L. Fundamentals of Motor Control. (Academic Press, 2012).

Stanley, J. & Miall, R. C. Using Predictive Motor Control Processes in a Cognitive Task: Behavioral and Neuroanatomical Perspectives. in Progress in Motor Control: A Multidisciplinary Perspective (ed. Sternad, D.) 337–354 (Springer US, Boston, MA, 2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-77064-2_17.

Taylor, A. & Gottlieb, S. Convergence of Several Sensory Modalities in Motor Control. in Feedback and Motor Control in Invertebrates and Vertebrates (eds. Barnes, W. J. P. & Gladden, M. H.) 77–91 (Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht, 1985). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-011-7084-0_5.

Vogt, S., Taylor, P. & Hopkins, B. Visuomotor priming by pictures of hand postures: Perspective matters. Neuropsychologia 41, 941–951 (2003).

Burman, K., Darian‐Smith, C. & Darian‐Smith, I. Macaque red nucleus: origins of spinal and olivary projections and terminations of cortical inputs. J. Comp. Neurol. 423, 179–196 (2000).

Dosenbach, N. U. et al. Distinct brain networks for adaptive and stable task control in humans. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 104, 11073–11078 (2007).

Biswal, B., Zerrin Yetkin, F., Haughton, V. M. & Hyde, J. S. Functional connectivity in the motor cortex of resting human brain using echo‐planar MRI. Magn. Reson. Med. 34, 537–541 (1995).

Power, J. D. et al. Functional network organization of the human brain. Neuron 72, 665–678 (2011).

Seeley, W. W. et al. Dissociable intrinsic connectivity networks for salience processing and executive control. J. Neurosci. 27, 2349–2356 (2007).

Yeo, B. T. et al. The organization of the human cerebral cortex estimated by intrinsic functional connectivity. J. Neurophysiol. 106, 1125–1165 (2011).

Allen, E. J. et al. A massive 7T fMRI dataset to bridge cognitive neuroscience and artificial intelligence. Nat. Neurosci. 25, 116–126 (2022).

Gordon, E. M. et al. Precision functional mapping of individual human brains. Neuron 95, 791–807.e7 (2017).

Laumann, T. O. et al. Functional System and Areal Organization of a Highly Sampled Individual Human Brain. Neuron 87, 657–670 (2015).

Lynch, C. J. et al. Rapid precision functional mapping of individuals using multi-echo fMRI. Cell Rep. 33, 108540 (2020).

Greene, D. J. et al. Integrative and network-specific connectivity of the basal ganglia and thalamus defined in individuals. Neuron 105, 742–758.e6 (2020).

Marek, S. et al. Spatial and temporal organization of the individual human cerebellum. Neuron 100, 977–993.e7 (2018).

Zheng, A. et al. Parallel hippocampal-parietal circuits for self-and goal-oriented processing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 118 https://www.pnas.org/doi/abs/10.1073/pnas.2101743118 (2021).

Beissner, F. Functional MRI of the brainstem: common problems and their solutions. Clin. Neuroradiol. 25, 251–257 (2015).

de Hollander, G., Keuken, M. C. & Forstmann, B. U. The subcortical cocktail problem; mixed signals from the subthalamic nucleus and substantia nigra. PloS One 10, e0120572 (2015).

Wright, S. M. & Wald, L. L. Theory and application of array coils in MR spectroscopy. NMR Biomed. Int. J. Devoted Dev. Appl. Magn. Reson. Vivo 10, 394–410 (1997).

Gordon, E. M. et al. A somato-cognitive action network alternates with effector regions in motor cortex. Nature 617, 1–9 (2023).

Ren, J. et al. The somato-cognitive action network links diverse neuromodulatory targets for Parkinson’s disease. bioRxiv 2023–12 (2023).

Skandalakis, G. P. et al. White matter connections within the central sulcus subserving the somato-cognitive action network. Brain awaf022, https://academic.oup.com/brain/advance-article/doi/10.1093/brain/awaf022/7984389 (2025).

Hara, M., Murakawa, Y., Wagatsuma, T., Shinmoto, K. & Tamaki, M. Feasibility of Somato-Cognitive Coordination Therapy Using Virtual Reality for Patients with Advanced Severe Parkinson’s Disease. J. Park. Dis. 14, 1–4 (2024).

Baldermann, J. C. et al. A critical role of action-related functional networks in Gilles de la Tourette syndrome. Nat. Commun. 15, 1–15 (2024).

Newbold, D. J. et al. Cingulo-opercular control network and disused motor circuits joined in standby mode. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 118, e2019128118 (2021).

Dosenbach, N. U. F., Raichle, M. E. & Gordon, E. M. The brain’s action-mode network. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 1–11 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41583-024-00895-x (2025)

Peters, S. K., Dunlop, K. & Downar, J. Cortico-striatal-thalamic loop circuits of the salience network: a central pathway in psychiatric disease and treatment. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 10, 104 (2016).

Qiao, L. et al. The Motivation-Based Promotion of Proactive Control: The Role of Salience Network. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 12 https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/humanneuroscience/articles/10.3389/fnhum.2018.00328/full (2018).

Yuen, G. S. et al. The salience network in the apathy of late-life depression. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 29, 1116–1124 (2014).

Seeley, W. W. The salience network: a neural system for perceiving and responding to homeostatic demands. J. Neurosci. 39, 9878–9882 (2019).

Salo, T. et al. NiMARE: neuroimaging meta-analysis research environment. NeuroLibre 1, 7 (2022).

Yarkoni, T., Poldrack, R. A., Nichols, T. E., Van Essen, D. C. & Wager, T. D. Large-scale automated synthesis of human functional neuroimaging data. Nat. Methods 8, 665–670 (2011).

Krimmel, S. R. et al. Resting State Functional Connectivity of the Rat Claustrum. Front. Neuroanat. 13 https://doi.org/10.3389/fnana.2019.00022 (2019).

Krimmel, S. R. et al. Resting state functional connectivity and cognitive task-related activation of the human claustrum. NeuroImage 196, 59–67 (2019).

Gan, G., Ma, C. & Wu, J. Data Clustering: Theory, Algorithms, and Applications. (SIAM, 2020).

Gilmore, A. W., Nelson, S. M. & McDermott, K. B. Precision functional mapping of human memory systems. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 40, 52–57 (2021).

Kuypers, H. G. & Lawrence, D. G. Cortical projections to the red nucleus and the brain stem in the rhesus monkey. Brain Res. 4, 151–188 (1967).

Mewes, K. & Cheney, P. D. Primate rubromotoneuronal cells: parametric relations and contribution to wrist movement. J. Neurophysiol. 72, 14–30 (1994).

Allen, W. E. et al. Thirst regulates motivated behavior through modulation of brainwide neural population dynamics. Science 364, eaav3932 (2019).

Lynch, C. J. et al. Frontostriatal salience network expansion in individuals in depression. Nature 633, 624–633 (2024).

György Buzsáki, M. D. The Brain from inside Out. (Oxford University Press, 2019).

Llinás, R. R. I of the Vortex: From Neurons to Self. (MIT press, 2002).

Chin, R., Chang, S. W. & Holmes, A. J. Beyond cortex: The evolution of the human brain. Psychol. Rev. 130, 285 (2023).

Gordon, E. M. et al. Default-mode network streams for coupling to language and control systems. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 117, 17308–17319 (2020).

Raut, R. V. et al. Global waves synchronize the brain’s functional systems with fluctuating arousal. Sci. Adv. 7, eabf2709 (2021).

Shine, J. M. The thalamus integrates the macrosystems of the brain to facilitate complex, adaptive brain network dynamics. Prog. Neurobiol. 199, 101951 (2021).

Chiel, H. J. & Beer, R. D. The brain has a body: adaptive behavior emerges from interactions of nervous system, body and environment. Trends Neurosci. 20, 553–557 (1997).

Dum, R. P., Levinthal, D. J. & Strick, P. L. The mind–body problem: Circuits that link the cerebral cortex to the adrenal medulla. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 116, 26321–26328 (2019).

Micieli, R., Rios, A. L. L., Aguilar, R. P., Posada, L. F. B. & Hutchison, W. D. Single-unit analysis of the human posterior hypothalamus and red nucleus during deep brain stimulation for aggressivity. J. Neurosurg. 126, 1158–1164 (2017).

Leys, D., Nègre, A., Rondepierre, P. H., Ares, G. S. & Godefroy, O. Small Infarct Limited to the Ventromedial Part of the Red Nucleus: Partial, Transient and Isolated Unilateral Oculomotor Nerve Palsy. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2, 378–379 (1992).

Meda, K. S. et al. Microcircuit mechanisms through which mediodorsal thalamic input to anterior cingulate cortex exacerbates pain-related aversion. Neuron 102, 944–959.e3 (2019).

Mumford, D. On the computational architecture of the neocortex: I. The role of the thalamo-cortical loop. Biol. Cybern. 65, 135–145 (1991).

Newbold, D. J. et al. Plasticity and Spontaneous Activity Pulses in Disused Human Brain Circuits. Neuron 107, 580–589.e6 (2020).

Miller, K. L. et al. Multimodal population brain imaging in the UK Biobank prospective epidemiological study. Nat. Neurosci. 19, 1523–1536 (2016).

Van Essen, D. C., Glasser, M. F., Dierker, D. L., Harwell, J. & Coalson, T. Parcellations and hemispheric asymmetries of human cerebral cortex analyzed on surface-based atlases. Cereb. Cortex 22, 2241–2262 (2012).

Glasser, M. F. et al. The minimal preprocessing pipelines for the Human Connectome Project. Neuroimage 80, 105–124 (2013).

Marek, S. et al. Reproducible brain-wide association studies require thousands of individuals. Nature 603, 654–660 (2022).

Casey, B. J. et al. The adolescent brain cognitive development (ABCD) study: imaging acquisition across 21 sites. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 32, 43–54 (2018).

Feczko, E. et al. Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) community MRI collection and utilities. BioRxiv 2021. 07, 451638 (2021).

Glasser, M. F. et al. A multi-modal parcellation of human cerebral cortex. Nature 536, 171–178 (2016).

Glasser, M. F. et al. The human connectome project’s neuroimaging approach. Nat. Neurosci. 19, 1175–1187 (2016).

Smith, S. M. et al. Resting-state fMRI in the human connectome project. Neuroimage 80, 144–168 (2013).

Zhang, Y., Brady, M. & Smith, S. Segmentation of brain MR images through a hidden Markov random field model and the expectation-maximization algorithm. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 20, 45–57 (2001).

Dowdle, L. T. et al. Evaluating increases in sensitivity from NORDIC for diverse fMRI acquisition strategies. NeuroImage 270, 119949 (2023).

Raut, R. V., Mitra, A., Snyder, A. Z. & Raichle, M. E. On time delay estimation and sampling error in resting-state fMRI. Neuroimage 194, 211–227 (2019).

DuPre, E. et al. TE-dependent analysis of multi-echo fMRI with* tedana. J. Open Source Softw. 6, 3669 (2021).

Kundu, P., Inati, S. J., Evans, J. W., Luh, W.-M. & Bandettini, P. A. Differentiating BOLD and non-BOLD signals in fMRI time series using multi-echo EPI. Neuroimage 60, 1759–1770 (2012).

Kundu, P. et al. Integrated strategy for improving functional connectivity mapping using multiecho fMRI. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 110, 16187–16192 (2013).

Posse, S. et al. Enhancement of BOLD‐contrast sensitivity by single‐shot multi‐echo functional MR imaging. Magn. Reson. Med. J. Int. Soc. Magn. Reson. Med. 42, 87–97 (1999).

Li, Y.-O., Adalı, T. & Calhoun, V. D. Estimating the number of independent components for functional magnetic resonance imaging data. Hum. Brain Mapp. 28, 1251–1266 (2007).

Van Der Walt, S., Colbert, S. C. & Varoquaux, G. The NumPy array: a structure for efficient numerical computation. Comput. Sci. Eng. 13, 22–30 (2011).

Jones, E., Oliphant, T. & Peterson, P. SciPy: Open source scientific tools for Python. (2001).

McKinney, W. Data structures for statistical computing in python. in Proceedings of the 9th Python in Science Conference vol. 445 51–56 (Austin, TX, 2010).

Pedregosa, F. et al. Scikit-learn: Machine learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 12, 2825–2830 (2011).

Brett, M. et al. nipy/nibabel. Zenodo. DOI Httpsdoi Org. 10 5281, (2019).

Dice, L. R. Measures of the amount of ecologic association between species. Ecology 26, 297–302 (1945).

Sorensen, T. A. A method of establishing groups of equal amplitude in plant sociology based on similarity of species content and its application to analyses of the vegetation on Danish commons. Biol. Skar 5, 1–34 (1948).

Power, J. D., Barnes, K. A., Snyder, A. Z., Schlaggar, B. L. & Petersen, S. E. Spurious but systematic correlations in functional connectivity MRI networks arise from subject motion. Neuroimage 59, 2142–2154 (2012).

Fair, D. A. et al. Correction of respiratory artifacts in MRI head motion estimates. Neuroimage 208, 116400 (2020).

Bianciardi, M. et al. Toward an in vivo neuroimaging template of human brainstem nuclei of the ascending arousal, autonomic, and motor systems. Brain Connect. 5, 597–607 (2015).

Rosvall, M. & Bergstrom, C. T. Maps of random walks on complex networks reveal community structure. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 105, 1118–1123 (2008).

Murtagh, F. & Legendre, P. Ward’s hierarchical agglomerative clustering method: which algorithms implement Ward’s criterion? J. Classif. 31, 274–295 (2014).

Ward, J. H. Jr. Hierarchical grouping to optimize an objective function. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 58, 236–244 (1963).

Charrad, M., Ghazzali, N., Boiteau, V., Niknafs, A. & Charrad, M. M. Package ‘nbclust’. J. Stat. Softw. 61, 1–36 (2014).

Jh, S. et al. Thalamus Optimized Multi Atlas Segmentation (THOMAS): fast, fully automated segmentation of thalamic nuclei from structural MRI. NeuroImage 194, 272–282 (2019).

Su, J. H. et al. Improved Vim targeting for focused ultrasound ablation treatment of essential tremor: A probabilistic and patient-specific approach. Hum. Brain Mapp. 41, 4769–4788 (2020).

Pfefferbaum, A., Sullivan, E. V., Zahr, N. M., Pohl, K. M. & Saranathan, M. Multi-atlas thalamic nuclei segmentation on standard T1-weighed MRI with application to normal aging. Hum. Brain Mapp. 44, 612–628 (2023).

Diedrichsen, J. & Zotow, E. Surface-based display of volume-averaged cerebellar imaging data. PloS One 10, e0133402 (2015).

Gordon, E. M. et al. Generation and evaluation of a cortical area parcellation from resting-state correlations. Cereb. Cortex 26, 288–303 (2016).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH grants T32DA007261 (S.R.K), MH120989 (C.J.L.), MH120194 (J.T.W.), NS123345 (B.P.K.), NS098482 (B.P.K.), NS124789 (S.A.N.), NS133486 (J.L.R.), MH120194 (J.T.W.), DA047851 (C.J.L.), MH118388 (C.J.L.), MH114976 (C.J.L.), MH129616 (T.O.L.), DA041148 (D.A.F.), DA04112 (D.A.F.), MH115357 (D.A.F.), MH096773 (D.A.F. and N.U.F.D.), MH122066 (E.M.G., D.A.F. and N.U.F.D.), MH121276 (E.M.G., D.A.F. and N.U.F.D.), NS140256 (E.M.G.), MH124567 (E.M.G., D.A.F. and N.U.F.D.), NS129521 (E.M.G., D.A.F. and N.U.F.D.); by Center for Brain Research in Mood Disorders; by Eagles Autism Challenge; by the Dystonia Medical Research Foundation (S.A.N.); by the National Spasmodic Dysphonia Association (E.M.G. and S.A.N.); by the Taylor Family Foundation (T.O.L.); by the Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Research Center (N.U.F.D.); by the Kiwanis Foundation (N.U.F.D.); by the Washington University Hope Center for Neurological Disorders (E.M.G., B.P.K. and N.U.F.D.); and by Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology pilot funding (E.M.G. and N.U.F.D.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.R.K., T.O.L., E.M.G., and N.U.F.D. conceived the project. S.R.K., T.O.L., R.J.C., A.N.V., J.M., K.M.S., F.I.W., N.R.P., A.M., N.J.B., B.P.K., C.J.L., E.M.G., and N.U.F.D. performed experiments. S.R.K., T.O.L., R.J.C., T.H., J.L.R., J.S.Shimony., J.T.W., S.A.N., A.N.V., A.W., A.Z.S., C.J.L., E.M.G., N.U.F.D., carried out the data analysis. S.R.K., T.O.L, R.J.C, T.H., J.L.R., J.S. Shimony, J.T.W., S.A.N., S.M., B.P.K., J.S.Siegel, H.N.A., A.Z.S., D.A.F., C.J.L., M.E.R., E.M.G., and N.U.F.D. wrote the manuscript. T.O.L., S.M., A.Z.S., C.J.L., E.M.G., and N.U.F.D. managed the project. All authors discussed the results and implications and commented on the manuscript at all stages.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Within the last year, J.S.Siegel was an employee of Sumitomo Pharma America and received consulting fees from Otsuka and Longitude Capital. D.A.F., and N.U.F.D. have a financial interest in Turing Medical Inc. and may benefit financially if the company is successful in marketing FIRMM motion monitoring software products. J.T.W. is a consultant for Turing Medical Inc. A.N.V., E.M.G., D.A.F. and N.U.F.D. may receive royalty income based on technology developed at Washington University School of Medicine and Oregon Health and Sciences University and licensed to Turing Medical Inc. D.A.F. and N.U.F.D. are co-founders of Turing Medical Inc. These potential conflicts of interest have been reviewed and are managed by Washington University School of Medicine, Oregon Health and Sciences University and the University of Minnesota. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Joan Baizer and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Krimmel, S.R., Laumann, T.O., Chauvin, R.J. et al. The human brainstem’s red nucleus was upgraded to support goal-directed action. Nat Commun 16, 3398 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-58172-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-58172-z