Abstract

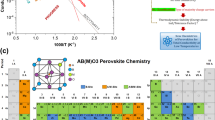

High-entropy LnBaCo2O5+δ perovskites are explored as rSOC air electrodes, though high configuration entropy (Sconfig) alone poorly correlates with performance due to multifactorial interactions. We systematically engineer LnBaCo2O5+δ perovskites (Ln = lanthanides) with tunable Sconfig and 20 consistent parameters, employing Bayesian-optimized symbolic regression to decode activity descriptors. The model identifies synergistic contributions from Sconfig, ionic radius, and electronegativity, enabling screening of 177,100 compositions. Three validated oxides exhibit superior activity/durability, particularly (Pr0.05La0.4Nd0.2Sm0.1Y0.25)BaCo2O5+δ, showing enhanced oxygen vacancy concentration and disordered transport pathways. First-principles studies reveal optimized charge transfer kinetics via cobalt-oxygen bond modulation. Further, the interplay between first ionization energy, atomic mass, and ionic Lewis acidity dictates stability. This data-driven approach establishes a quantitative framework bridging entropy engineering and catalytic functionality in complex oxides.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Multivalent cation-doped polynary perovskite oxides are increasingly recognized for their unique geometric and electronic properties, making them pivotal materials in advanced energy conversion systems1. A prominent example is their role as oxygen electrodes in reversible solid oxide cells (rSOCs), such as La0.6Sr0.4Co0.8Fe0.2O3-δ (LSCF) and PrBaCo2O5+δ (PBC)2,3. Due to the vast array of compositional possibilities and diverse material properties, the development of these perovskites has traditionally followed a trial-and-error approach, a time-consuming process that could benefit from efficient descriptors capable of elucidating the relationship between material properties and performance, thereby accelerating the discovery of high-performance electrocatalysts4. For example, the bulk oxygen p-band center5 and the metal 3d–O 2p covalency6 were proven to be able to modulate the orbital alignment of electrocatalyst with absorbents, further the intrinsic reactivity. High-throughput density functional theory (DFT) also illustrated the linear correlation between O 2p center and surface oxygen exchange coefficient7. Additionally, ionic Lewis acid strength (ISA) has emerged as a key descriptor, with research showing that decreased A-site and increased B-site ISAs enhance oxygen vacancy (Vo) formation and lower the migration barrier for oxygen ions8. More recently, configurational entropy (Sconfig) has been explored as a descriptor to guide the development of perovskite oxides. For instance, introducing Pr/Y/Ba into LSCF significantly reduced degradation rates from 100% over 24 h to 0.25% per 1000 h in the presence of Cr9. Likewise, La/Nd/Sm/Gd incorporated PrBaFe2O5+δ (PBF) exhibited a peak power density of 1020.69 mW cm−2 and a degradation rate of 0.17% per hour at 800 °C, surpassing standard PBF (794.96 mW cm−2 and 0.79% per hour)10. Similarly, doping La/Nd/Ba/Sr/Ca into PBC improved both its activity and durability by increasing electronic and ionic conductivity11.

However, many experimentally derived descriptors, such as Sconfig, have shown limitations in predicting the behavior of high-dimensional systems. This is reminiscent of the oversimplification in genetics, where biological traits are often the result of the complex interaction of multiple genes, rather than the expression of a single gene12. In the case of inorganic materials, while Sconfig reflects the degree of local ionic disorder, it does not reliably predict specific functionalities13,14,15. Moreover, most high-Sconfig materials have been discovered serendipitously, with a lack of systematic design principles, raising concerns about the reliability and generalizability of Sconfig as a predictive index for material performance.

Machine learning (ML) offers a promising approach to overcoming these challenges by analyzing large datasets of atomic and material properties16,17. However, conventional black-box ML models, such as neural networks, often provide limited interpretability18, while more transparent models, such as linear regression, sacrifice accuracy for explainability. Symbolic regression (SR) provides a compelling alternative, balancing prediction accuracy with interpretability. Techniques such as Sure Independence Screening and Sparsifying Operator (SISSO) use mathematical operators to combine material properties, generating analytical expressions from high-dimensional dataset19. Despite its potential, SR often requires time-consuming simulations and produces low-dimensional descriptors, limiting its application to more complex systems20. Genetic algorithms (GAs), on the other hand, offer a more efficient approach by focusing on target values, although their inherent randomness and difficulties in optimizing hyperparameters have limited their widespread adoption21. Efforts to improve efficiency, such as using grid search techniques for hyperparameter optimization, have shown potential, but remain suboptimal in terms of overall efficiency22.

Herein, we developed a material pool of over 50 LnBaCo2O5+δ perovskites (Ln= Pr, La, Ga, Nd, Ce, Sm), systematically varying their Sconfig by doping Ln sites with 2–4 elements. This pool was rigorously characterized across 20 oxygen electrocatalysis-related properties, ensuring robust data collection that minimized variability often encountered in literature reports. Our analysis revealed poor linear correlations between Sconfig and catalytic performance metrics. Instead, using Bayesian-optimized symbolic regression (BOSR) combined with a mixture of experts (MoE) ensemble model, we identified key structure-activity relationships that linked Sconfig, ion radius (R), and electronegativity (χ) to catalytic performance23. Subsequently, we synthesized 35 perovskite oxides selected from 177,100 unexplored compositions, demonstrating the superior performance of three top-ranked candidates: (Pr0.05La0.4Nd0.2Sm0.1Y0.25)BaCo2O5+δ (PLNSY), (Pr0.25La0.35Gd0.05Nd0.05Sm0.05Y0.25) BaCo2O5+δ (PLGNSY), and (Pr0.25La0.2Gd0.1Nd0.1Ce0.1Sm0.05Y0.2)BaCo2O5+δ (PLGNCSY), in both SOFC and SOEC modes. Among them, PLNSY exhibited particularly impressive performance, attributed to its high oxygen vacancy concentration and disorder, which enhanced the transport of ionic charge carriers (O2– and protons). Additionally, PLNSY demonstrated exceptional durability, with a detailed analysis revealing that the interplay between first ionization energy (IE), relative atomic mass (M), and ISA predominantly influences the degradation rate of these complex perovskites.

Results

Evaluation of individual descriptor

Using the PBC system, a benchmark air electrode, we equally diluted Pr by incorporating two, three, or four Ln elements selected from a lanthanide pool (La, Ce, Sm, Gd, Nd, Y) to achieve maximized Sconfig values of 1.1 R, 1,39 R and 1.61 R (where R is the gas constant), respectively. Ln dopants provide a versatile platform for fine-tuning electrocatalytic performance due to their unique gradient-filled 4 f orbital electron configuration24. All samples (Supplementary Table 1) exhibited a tetragonal structure with the P4/mmm space group (PDF#04-015-0633). A secondary phase of BaCeO3 was observed in all the Ce-containing samples; however, higher Sconfig significantly suppressed its formation (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Interestingly, using a basic univariate linear regression model, we found that the polarization resistances (Rps), determined by symmetric half-cell measurements at 650, 700, and 750 oC in dry air, increased with the increase of Sconfig, even when the impact of phase impurity was excluded (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 2, 3). This finding indicates that merely increasing Sconfig is insufficient to optimize the electrocatalytic activity of materials, even within the dataset of LnBaCo2O5+δ layered perovskites with identical crystal structures. In addition to Sconfig, we calculated six theoretical average atomic features (TAFs), including R, χ, ISA, IE, M, and octahedral/tolerance factors (μ/t) for the dataset22 (Supplementary Figs. 4–9). The degree of linear association (DLA) between these TAFs and Rps, represented as R2, was summarized in Fig. 1c. We also analyzed seven structure-related parameters (i.e., oxygen non-stoichiometry (δ), unit cell volume, bond length Ba-O, bond length Co-O, bond length Ln-O, bond angle O-Ln-O and bond angle O-Co-O) and their DLA with Rps (Supplementary Figs. 10–13 and Fig. 1d). Unfortunately, no significant association between any of these 13 descriptors and activity was found, with a maximum R2 value of only 0.137 for χ. To explore more potential parameters, we selected 11 representative materials based on their distributions in all average TAFs, including PBC as a benchmark, for a total of 12 materials. The detailed selection protocol was described in Supplementary Fig. 14. We evaluated additional properties, such as electrical conductivity, thermal expansion coefficient (TEC), lattice oxygen proportion (quantified from O 1 s XPS spectra), valence band X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (VB-XPS) integration center for this dataset (Fig. 1e, f and Supplementary Fig. 15–18). However, these parameters also exhibited poor correlation with the activity, as indicated by the wide 95% confidence bands, even after expanding the test dataset from 12 to 20 materials (Supplementary Fig. 15, 16). To focus on high-performing candidates, we selected six materials (five of the top 10% ranking contenders in performance and PBC) for further characterizations using O K-edge (Supplementary Fig. 19) and Co K-edge X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS). These analyses aimed to elucidate the predictive potential of the highest occupied-lowest unoccupied band orbital distance (distance VB-CB) and cobalt oxidation state, two potential descriptors discussed by Xu et al. 25, and Sun et al. 26, respectively. However, only low R2 values (<0.46) were obtained (Fig. 1g). In addition to Rps, we also attempted to elucidate the relationship between structural/electronic parameters and the kinetic performance index, activation energy (Ea) (Supplementary Fig. 20, 21), but again, none of the individual descriptors enabled direct prediction. These results highlight the limitations of single-variable approaches and underscore the necessity for advanced models that can decode the complex interplay of multiple material features.

a Workflow diagram illustrating the process of database establishment and activity descriptor. b Potential correlation between Rp and Sconfig in the dataset. Each rectangular area in (b) represents the same Sconfig value. Degree of linear association between polarization resistance (from 750 °C to 650 °C) and (c) 6 theoretical physical atomic features, and (d) 7 experimental physical parameters for candidates in the database. e Correlation of lattice oxygen percentage (obtained from O1s XPS), VB XPS integration center, thermal Expansion Coefficient (TEC), and conductivity with polarization resistance (from 750 oC to 650 oC) for 12 selected materials from the database. f Correlation of extended distance VB-CB with polarization resistance (from 750 oC to 650 oC). g Co K-edge spectra of 5 candidates ranked in the top 10% by performance, along with PrBaCo2O5+δ. The inset shows the correlation between Rp and Co valence for 6 samples. Shaded areas in (d–g) represent the 95% confidence interval for linear fitting.

Workflow of the ensembled interpretable machine learning (EIML)

We employed a 4-step EIML process for the dataset we developed (Fig. 2a): (1) data preprocessing, (2) models training and optimization, (3) ensembled approach for enhanced fitting, and (4) screening of new perovskites. First, to streamline material features, we preprocessed the data for EIML by focusing on the six TAFs listed in Fig. 2a, excluding μ/t as it correlates closely with cation radius (Methods and Supplementary Table 2). The resulting dataset contains 50 materials (excluding PBC) with 13 input features (six TAFs plus the proportions of 7 A-site cations), along with target values of Rp-750, Rp-700, and Rp-650. Using the complete dataset, we applied a GA model that represents mathematical expressions using a tree structure (Fig. 2b).

a Overall workflow diagram of the ensembled interpretable model. b Representative procedure of a BOSR approach. Tree diagrams represent expressions for Rp-750. Internal nodes denote employed functions (i.e., arithmetic operators), while terminal nodes represent constants or features. The left and right tree stands for r-SR (length of 18) and BOSR (length of 19), respectively. c Comparison of the best model performance obtained using r-SR (green) and BOSR (orange) on the entire dataset and subsets labeled with Rp-750. d RMSE between symbolic regression predictions and actual values across different data partitions, labeled by entire or corresponding elements. The x-axis label indicates the category of the corresponding value. All values are normalized to the mean of 6.17 and the variance of 1, and thus have no physical units. e 5-fold cross-validation results for models trained without (green) and with element-gate (red). White circles denote test set results from the 5-fold cross-validation, while the black cross indicates the mean value. Violin plots show the distribution of the five test results. f Scatter plot comparing experimental vs. predicted Rp values for the element-gate model. g Count of occurrence for each TAF in all BOSR equations. Percentages indicate the proportion of total occurrences for all features and constants combined. The occurrence count consolidates mergeable terms using a simplified formula.

To avoid the inefficiencies of random hyperparameter search across a vast configuration space, we implemented a BOSR approach. This approach uses an iterative process where a surrogate estimator model, trained on historical experimental data, guides exploration toward high-performing hyperparameter combinations while minimizing computational overhead. To verify its effectiveness, we divided the dataset into element-specific subsets (i.e., La-, Ga-, Ce-, Nd-, Sm-, and Y-) and evaluated Rp-750 performance on the entire dataset and its subsets. We compared the performance of regular SR (rSR) with BOSR, setting the total number of hyperparameter sets to 1200 and comparing the best expression obtained (Methods and Supplementary Table 3). To prioritize interpretability, we filtered out any output expressions exceeding a length of 20. As shown in Fig. 2c, a normalized RMSE of 0.75 and 0.73 was obtained for rSR and BOSR, respectively, on the entire dataset. BOSR significantly outperformed rSR in subset training, with the most substantial improvement (~10%) in the La-subset (Fig. 2c and supplementary Note 1). The fitting degree for BOSR on the entire dataset is shown in Fig. 2d, with RMSE values of 0.73, 0.62, and 0.76 for Rp-750, Rp-700, and Rp-650, respectively (denoted as dashed baselines). This inconsistency in performance is mainly due to the varied impact of different dopants. Subset training with BOSR significantly improved data consistency, reducing RMSE values by up to 18% (Y-subset at 700 oC, see Supplementary Fig. 22–24). Moreover, we confirmed the indeterminate effect of manually optimizing constant values within the predicted expression (Supplementary Note 2, and Supplementary Fig. 25).

To further improve fitting accuracy, we employed a Mixture of Experts (MoE) approach, using the predictions from each subset as inputs for a linear regression model. A 5-fold cross-validation was implemented to enhance the generalization ability of the model and reduce overfitting (details in Methods). As shown in the green section of Fig. 2e, the direct MoE approach (entire dataset and six element-wise subsets) resulted in inconsistent effects on RMSE because all models for the subsets contributed during prediction, even if they were irrelevant. To address this issue, we introduced an element-gate MoE method, where models for subsets with irrelevant elements were deactivated by setting their weights to zero using a control gate. As shown in the red section of Fig. 2e, this element-gate MoE model significantly improved performance (Supplementary Note 3 and Supplementary Fig. 26–28). By taking the arithmetic mean of the weights from the five models of the 5-fold cross-validation, we obtained the final ensemble models. The RMSE for the element-gate model on the entire dataset was 0.67, 0.56, and 0.59 for Rp-750, Rp-700, and Rp-650, respectively, matching the predicted trends with experimental values (Fig. 2f). Compared to direct fitting the entire dataset, RMSE values were reduced by.7.8%, 9.0%, and. 22.1%, respectively. Finally, we derived Rp expressions for both the entire dataset and the six subsets at three specific temperatures (21 expressions in total). All expressions are listed in Supplementary Table 4. The complexity of these expressions supports our experimental analysis in Fig. 1, demonstrating that a simple positive or negative correlation between individual features and Rp cannot be adequately defined. To compare feature importance, we calculated the probability of each feature occurring within the expressions. In addition to the contributions of element concentration (33.5%) and constants (25.6%) shown in Supplementary Fig. 29, the relative importance of TAFs affecting Rp follows this order: Sconfig (15.6%) > R (9.5%) > χ (5%) > ISA (4%) = IE (4%) > M (3%). The limited contribution of Sconfig confirms our hypothesis that the apparent catalytic performance of perovskites arises from the co-expression of multiple major material genes.

To identify promising new candidates and validate the generalization of the model, we generated a comprehensive pool of material compositions by considering all possible compositions of A-site, formed by combining elements from (La, Gd, Nd, Ce, Sm, Y) with Pr, with a step size of 0.05. This search resulted in a total of 177,100 potential perovskite formulations. After calculating TAFs for these formulations, we used the ensembled element-gate model to predict Rp values at 750 °C, 700 °C, and 650 °C, which were then ranked. The overall performance of each material was defined as the sum of its ranking across the three temperatures. Figure 3a shows the Rp rankings at elevated temperatures for all predicted perovskite compositions (see Supplementary Data for the complete list of predicted and selected materials). The projections across the three Rp planes indicate that most compositions exhibit consistent performance across the temperatures, suggesting that Rp values are relatively stable - either consistently high or low. We selected 30 materials from the top 40 based on the sum of rankings, excluding 10 compositions with Ce ratios exceeding 0.15. Additionally, we selected five outliers where the predicted Rp at 700 oC was poor, but Rp-650 ranked within the top 70 and Rp-750 ranked within the top 5 (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Table 5). A detailed discussion of the ranking methodology is provided in Supplementary Note 4.

a Distribution of rankings for all predicted performances. The three axes represent the Rp values at three different temperatures (650, 700 and 750 oC). b Distribution of rankings for the predicted performances of all experimentally validated perovskites. Blue points indicate the top 40 ranked points (excluding 9 points with high Ce content). For Fig. 3 a and b, red points represent the three materials with the best experimentally validated performance. Purple points correspond to materials with poor Rp-700 but good Rp-650 and Rp-750 in the top ranking. The Rp values for the blue points were scaled down to 1:1000 for better visualization. c Typical EIS of symmetrical cells with an anode|LSGM|anode configuration in dry air at 600 and 700 oC. d Temperature dependence of the area-specific resistance (ASR or Rp) of symmetrical cells with various air electrodes. e Distribution of relaxation time (DRT) of various air electrodes at 600 °C under a PO2 of 0.21 atm. f Summary of n values derived from frequency-dependent Rp vs. PO2 plots. g EIS of symmetrical cells with an anode|BZCYYb|anode configuration in 3% wet air at 650 oC. h j–V–P curves of single cells with various air electrodes, measured at 650 oC with a configuration of Ni-BZCYYb|BZCYYb|Cathode.

Overall, we synthesized 34 candidates (Supplementary data), characterized their structures (Supplementary Fig. 30), and tested their performances in an LSGM- supported symmetrical cell configuration. The PLNSY, PLGNSY, and PLGNCSY electrodes exhibited high reactivity. As shown in Fig. 3c, the Rps of PLNSY, PLGNSY, and PLGNCSY electrodes were 0.043, 0.050, and 0.050 Ω cm2 at 700 oC in dry air, significantly lower than that of PBC (0.0754 Ω cm2). Furthermore, the activation energies (Ea) of PLNSY, PLGNSY, and PLGNCSY were 95.97 ± 0.90, 91.91 ± 0.29, and 95.96 ± 0.15 kJ mol-1, respectively, which were also lower than that of PBC (101.62 ± 0.89 kJ mol-1) (Fig. 3d). To further investigate the electrochemical reaction kinetics, electrochemical impedance spectra (EIS) of the electrodes under different PO2 values were collected, and the spectra were fitted using the distribution of relaxation times (DRT). The fitted DRT plots of the various electrodes at 600 oC under different PO2 values are shown in Fig. 3e, f and Supplementary Fig. 31. Multiple distinct peaks corresponding to different frequency ranges were observed (see Supplementary Note 5). The low-frequency (LF) range (P1 + P2) could be attributed to oxygen surface adsorption/dissociation processes (PBC: 0.31, PLNSY: 1.03, PLGNSY: 0.85, and PLGNCSY: 0.93), while the high-frequency (HF) range (P3 + P4 + P5) exhibited less dependence on PO2 and was likely associated with charge transfer reactions (PBC: 0.02, PLNSY: 0.26, PLGNSY: 0.04, and PLGNCSY: 0.01)27. These electrodes were then used to assemble single cells for CO2 electroreduction. Supplementary Fig. 32 shows the j-V curves of cells with PBC, PLNSY, PLGNSY and PLGNCSY anodes, LSGM electrolytes, and a well-studied Ru/SDC/F-LSCF cathode28, tested at 800 °C in pure CO2. At 2 V and 1.6 V, the cell with PLNSY achieved high current densities of 2.54 and 1.58 A cm−2, respectively, which were 1.71 and 1.63 times higher than those using PBC (1.48 and 0.97 A cm−2). Moreover, BZCYYb-supported symmetrical cells were assembled and tested in wet air (3% H2O). As shown in Fig. 3g, the ASRs of PLNSY, PLGNSY, and PLGNCSY electrodes reached 0.128, 0.132, and 0.175 Ω cm2 at 650 oC, significantly outperforming PBC (0.262 Ω cm2). Given that BZCYYb exhibits mixed ion-hole conductivity in an oxidative atmosphere (only 48.4% ion conductivity in wet air at 700 oC, see Supplementary Note 6 and Supplementary Fig. 33), the calibrated polarization resistance (Rη) and Ea were calculated. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 32, PLNSY, PLGNSY, and PLGNCSY electrodes demonstrated superior calibrated electrochemical performance, with Rη values of 6.44, 13.03, and 17.16 Ω cm² at 700 °C and Ea values of 27.7, 18.1, and 14.6 kJ mol⁻¹, respectively, outperforming PBC (27.53 Ω cm² and 47.64 kJ mol⁻1). Typical EIS and j–V–P curves of proton conducting fuel cells with various air electrodes fueled by wet H2 (3% H2O) are shown in Fig. 3h. The cell with the PLNSY (see Supplementary Fig. 34) exhibited an ASR as low as 0.26 Ω cm2 at 550 oC, and a peak power density (Pmax) of 1.55 W cm−2 at 650 °C, greatly surpassing PBC-based cell (0.77 W cm−2).

To investigate the mechanism behind the high performance of these materials, the phase composition and crystal structure of PLNSY, PLGNSY and PLGNCSY were analyzed by XRD, combined with Rietveld refinements (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Table 6). All materials exhibit a pure tetragonal structure (P4/mmm). The improvement in thermal compatibility was further assessed by measuring the thermal expansion coefficients (TECs). PLNSY shows a relatively lower TEC (18.21 × 10−6 K−1) compared to PBC (21.71 × 10−6 K−1), suggesting better compatibility with representative electrolytes such as YSZ, LSGM, BCZYYb (TEC:10.1-12.5 × 10−6 K−1)29,30,31, as shown in Fig. 4b. Figure 4c shows the variation in oxygen content of the electrodes under N2 from 50 to 800 °C. The oxygen non-stoichiometry of PLNSY is consistently higher than that of PBC (e.g., 5.1 vs. 5.39 at 800 oC), and the dynamic oxygen content significantly decreases by 0.49 (from 5.59 to 5.1), outperforming all other counterparts (PBC: 0.3, PLGNSY: 0.36, PLGNCSY: 0.37).

a Refined XRD patterns of the investigated materials. b Linear expansion (dL/L0) measured in an air atmosphere. c Oxygen non-stoichiometry increment analysis as a function of temperature. d ECR curves measured at 700 oC. e O 1 s XPS spectra. f Atomic-resolution STEM image and surface plot along the [001] zone axes of PLNSY. g Corresponding element mapping images for PLNSY. Rietveld refinement results from in situ TOF NPD for h PBC. i PLNSY. j Crystalline structure models of PLNSY. k Formation energy of Vo at the Ba-O plane in PBC and PLNSY. l DFT-calculated energy barriers for OER and ORR mechanisms on the air electrodes of PBC and PLNSY. m Mean squared displacement of hydrogen atoms in PBC and PLNSY. n Time-dependent evolution of proton diffusion pathways in PBC and PLNSY.

The ion conduction properties were further compared using electrical conductivity relaxation (ECR) methods (Fig. 4d). When switching the PO2 from 0.21 atm to 0.1 atm, the relaxation time decreased from 2970 s (PBC) to 1366 s (PLNSY) at 700 °C, indicating accelerated oxygen ionic conduction in PLNSY, allowing it to reach new equilibrium more quickly. The oxygen-ion bulk diffusion coefficient (Dchem) and the oxygen surface exchange coefficient (Kchem) for PLNSY were calculated to be 8.63 × 10−6 cm2 s−1 (283.6% higher than PBC, 2.25 × 10−6 cm2 s−1) and 8.49 × 10−4 cm s−1 (62.3% higher than PBC, 5.23 × 10−4 cm s⁻¹), respectively. Furthermore, the low standard deviation of the fitting results (1.10% for PBC and 1.02% for PLNSY) demonstrates the reliability of our data. To further analyze surface oxygen species, the oxygen 1 s XPS curves were deconvoluted into four peaks (Fig. 4e), corresponding to lattice oxygen at 528.1 eV (P1), O− at 529.5 eV (P2), OH−/CO32– at 531.5 eV (P3), and adsorbed water (H2O) at 533.1 eV (P4). According to the fitting results in Supplementary Table 7, PLNSY has the highest ratio (1.49) of (P2 + P3)/P4 among all the materials (PBC:0.6, PLGNCSY:1.03, PLGNSY: 1.01), suggesting the highest concentration of surface Vo, consistent with TGA results. Focusing on the best-performing material, PLNSY, aberration-corrected transmission electron microscopy (AC-TEM) was used to reveal its fine structure. The configuration of PLNSY can be clearly seen from the atomic high-angle annular dark-field (HAADF)-STEM images along the [001] zone axes (Fig. 4f). Figure 4g displays the surface plots of PLNSY, depicting the intensity of the atomic columns. HAADF-STEM combined with X-ray energy dispersive spectrum (EDS) confirmed that the elements Pr, La, Nd, Y, Sm, Ba, and Co were uniformly distributed within the particles. These findings strongly indicate that a pure-phase PLNSY electrode material has been successfully fabricated.

The ordering of oxygen vacancies is strongly correlated with oxygen exchange kinetics32. To explore this, neutron powder diffraction (NPD) was employed to determine the oxygen occupancy. As shown in Fig. 4h–j, at 25 oC, about 23% of the Vo were located at the O3 (0, 0, 0.5) site in the Pr-O plane (Supplementary Table 8). Vo was nearly absent at the O1 (0, 0, 0) site in the Ba-O plane and the O2 (0, 0.5, 0.277) site in the Co-O2 plane. This suggests that Vo in PBC is highly ordered, aligning with the previous findings32,33. At 700 °C, the Vo content at the O3 site increased to 80%, with full occupancy still observed at the O1 and O2 sites (Supplementary Table 8). In contrast, the Vo in PLNSY were more evenly distributed across the planes, with 15% at the O3 site in the Pr-O plane, 11% at the O1 site in the Ba-O plane, and 10% at the O2 site in the Co-O plane, indicating a more random distribution of Vo. Moreover, at 700 oC, the vacancy content continued to increase, reaching 47% at the O3 site, 27% at the O1 site, and 22% at the O2 site. DFT calculations further confirmed that the formation energy of Vo in the Ba-O plane decreased from 0.8 eV in PBC to -2.75 eV in PLNSY (Fig. 4k, Supplementary Fig. 35-36). The increased disorder and higher quantity of oxygen vacancies facilitate surface oxygen exchange and conversion.

The thermodynamic energy barriers of the reversible ORR/OER processes (in protonic mode) on PBC and PLNSY slabs were compared using DFT calculations (Fig. 4l, Supplementary Fig. 37, 38). The low-index surfaces of PBC (101) and PLNSY (101) were selected for the DFT calculations. The Vo site on the top layer of the slab was chosen as the active site for both models. The ORR process on the air electrode surface is divided into several steps: O2 adsorption, oxygen evolution (*O2 → *O → *O + *H → *OH + *H → *H2O, where * indicates the absorption state), and *H2O desorption, whereas the OER is the inversed ORR. Notably, the maximum energy barrier for PBC in the OER pathway is 2.61 eV for the *O + *H → *O step, indicating that proton conduction is the rate-determining step, which limits the OER rate. In contrast, PLNSY requires only 1.75 eV for this process, further validating its enhanced proton migration capability. Moreover, the energy profiles for the ORR on both materials reveal that the oxygen molecule adsorption energies for PBC and PLNSY are –0.78 and –2.41 eV, respectively, indicating that oxygen adsorption is spontaneous on both materials but more favorable on PLNSY.

To further confirm the crucial role of proton conduction, Ab Initio Molecular Dynamics (AIMD) simulations were conducted at 1073 K to elucidate the proton diffusion pathways in PBC and PLNSY. Figure 4m shows the mean squared displacement (MSD) of protons, with higher MSD values observed for PLNSY, indicating faster proton mobility. Figure 4n illustrates the temporal evolution of proton diffusion pathways within the unit cells. After 30 ps, the protons in PLNSY exhibit interlayer transportation behavior, suggesting a continuous 3D proton transportation network. In contrast, proton diffusion in PBC remains confined within a monolayer, exhibiting a localized 2D network.

Besides activity, durability is another important factor in determining the commercialization potential of perovskite candidates. Koo et al. highlighted the significance of A-O bond strength as a driving force for surface segregation-induced degradation34. Therefore, based on the XRD Rietveld refinement data of electrodes before and after a 150-h stability test (700 oC, in open air), we defined the Δ Ba-O bond length and Δ Ln-O bond length and attempted to correlate them with the degradation rate. From the diagram in Fig. 1a, we selected 10 representative materials to ensure an even distribution based on their A-O bond characteristics (Supplementary Fig. 39). As shown in Fig. 5a, PLNSY exhibited a much slower degradation rate of 0.132% /100 h compared to PBC (0.256 % /100 h) in dry air (Supplementary Fig. 40, 41). These 10 materials, along with PLNSY, PLGNSY, and PLGNCSY, demonstrated an exceptionally strong linear correlation with R2 = 0.94 (for either ΔLn-O or ΔBa-O), confirming that A-O bond strength is a reliable indicator for the robustness of the materials (Supplementary Fig. 42).

a Relationship between degradation rate and Ln-O/Ba-O bond length. b Surface A/B and Ba/Pr ratios of PBC before and after stability test. c Thermal stability study of PBC after 1 × 106 Monte Carlo (MC) steps at 973 K. d DFT calculated formation energy of BaO. e The surface A/B and Ba/Pr ratios of PLNSY before and after stability test. f Thermal stability study of PLNSY after 1 × 106 MC steps at 973 K. g Thermal cycling stability of PLNSY. h Long-term stability test of PLNSY in a BZCYYb-supported symmetric cell configuration at 600 oC and 3% wet air. i Correlation matrix for atomic theoretical features and bond length information. j Performance of the linear regression model, with the horizontal axis representing the number of input features. The performance indicates the best model optimized using modified recursive feature elimination. k Normalized coefficients, derived from the linear regression coefficients without bond length information, expressed as percentages of the sum of absolute coefficients.

As further shown by the SEM-EDS results (Fig. 5b, Supplementary Fig. 43, 44), surface segregation of A-site cations, particularly Ba element, was confirmed on PBC after the stability test. The atomic ratios of A/B and Ba/Pr increased from 1.04 ± 0.02 to 1.09 ± 0.04 and 0.96 ± 0.04 to 1.08 ± 0.03, respectively. We also employed Monte Carlo methods to simulate the structural evolutions during thermal annealing up to 700 oC (973 K) forstan the PBC system. PBC is clearly unstable and shows distinct phase separation of Ba and Pr-containing species after thermal annealing. From a thermodynamic perspective (Fig. 5d, Supplementary Fig. 45, 46), we found that the calculated formation energy of BaO clusters on PBC is 6.31 eV, lower than that of PLNSY (7.58 eV). The SEM-EDS results (Fig. 5e) align with the theoretical study, showing that both A-site cations and Ba element segregations were suppressed in PLNSY. The Monte Carlo simulation also supported our finding, showing that PLNSY remains a nearly homogeneous single-phase structure after 1×106 MC steps at 700 oC (Fig. 5f). Moreover, PLNSY was investigated on a BZCYYb supported symmetric cell at 600 oC in wet air (3 vol%) over 150 h. The ASR remained stable at ~0.28 Ω cm2 throughout the test, with a degradation rate of 0.029% per 100 h (Fig. 5h). The ASR value at 600 °C under wet air conditions (Fig. 5h) was higher than the corresponding value in dry air (Fig. 3c), which can be attributed to the higher impedance associated with weaker proton (H⁺) conductivity compared to O²⁻ conductivity. Additionally, the filling of surface oxygen vacancies by H2O reduces the availability of active B-site metal ions, further contributing to the increased impedance. To assess the thermal cycling stability of PLNSY, rigorous testing was conducted on symmetric cells over a temperature range of 550–650 oC, with a heating and cooling rate of 10 oC min−1. During 20 thermal cycling tests at a current density of 600 mA cm−2, the voltage at 650 oC decreased only slightly from 0.86 V to 0.82 V (Fig. 5g).

Although A-O bond information could help assess the durability of materials, it is an uncontrollable descriptor that cannot be directly obtained without first conducting synthesis and crystal analysis of the materials. Therefore, controllable stability descriptors that capture the TAFs are desirable. As illustrated in the pair-wise correlation matrix (Fig. 5i and Supplementary Fig. 47), we extracted the features from the dataset presented in Fig. 5a, and found that Ba-O, Ln-Ba, and Ln-O bond lengths are highly correlated, with an R² of ~1, indicating strong consistency in the bond length measurements. Supplementary Fig. 48 shows a similar high correlation in the matrix derived from a larger dataset of 28 materials, including PLNSY, PLGNSY, PLGNCSY, and all materials without Ce doping (Fig. 1a). We considered the inclusion (red bar in Fig. 5j) and exclusion (yellow bar in Fig. 5j) of bond length information alongside the TAFs. In both cases, linear regression was used to model their relationship with the degradation rate. A modified recursive feature elimination (mRFE) method (Supplementary Note 7) was applied to determine the optimal number of input features. As shown in Fig. 5j, the linear regression model achieved promising performance (with R² ~0.98 and RMSE < 0.13) using only eight TAFs, suggesting that this combination of The TAFs is sufficient to produce a reliable estimator for durability. The normalized coefficients from the linear regression model indicate the relative importance of each TAF (Fig. 5k and Supplementary Fig. 49), with IE, M and ISA being the top three most influential factors, contributing an average of 30.1%, 18.1% and 3.8%, respectively. These findings suggest that for LnBaCo2O5+δ-based double perovskites, Sconfig does not appear to be a primary driver of activity or durability. However, the influence of Sconfig on performance may vary in other material systems, and the potential effects of high-entropy approaches at the A-site remain an open question.

Generalization of the models

To evaluate the generalizability of our model predictions, we extended our findings from the double perovskite PBC system to the single perovskite PSCF (Pr0.6Sr0.4Co0.2Fe0.8O3-δ)35,36. Ln-series elements were doped into the Pr at the A-site, maintaining the same proportions as in PLGNCSY, PLGNSY, and PLNSY from the PBC system, while keeping the Sr, Co, and Fe proportions constant. This led to the synthesis of PLGNSCY-SCF((Pr0.25La02Gd0.1Nd0.1Ce0.1Sm0.05Y0.2)0.6Sr0.4Co0.2Fe0.8O3-δ),PLGNSY-SCF((Pr0.25La0.35Gd0.05Nd0.05Sm0.05Y0.25)0.6Sr0.4Co0.2Fe0.8O3-δ), and PLNSY-SCF((Pr0.05La0.4Nd0.2Sm0.01Y0.25)0.6Sr0.4Co0.2Fe0.8O3-δ) materials. The EIS measurements were conducted on symmetrical cells configured as electrode|LSGM|electrode under dry air at temperatures ranging from 750 to 650 °C to evaluate their ASR values. As shown in Fig. 6a, the performance trends of the doped materials (PLNSY, PLGNSY, and PLGNCSY) in the PBC system were consistent across various temperatures. Similarly, the PSCF-series materials (Fig. 6b) followed comparable trends aligned with their PBC-series counterparts. For example, at 650 °C, the Rp values ranked as follows: PSCF (0.25 Ω·cm2) > PLGNSCY-SCF (0.194 Ω·cm2) > PLGNSY-SCF (0.18 Ω·cm2) > PLNSY-SCF (0.14 Ω·cm2). These results strongly support the high generalizability of the model’s observations, demonstrating that the trends observed in the PBC system extend robustly to the PSCF system, highlighting the broad applicability of the underlying principles across different material platforms.

Discussion

Decoding the intrinsic relationship between composition and activity remains a key yet challenging task in the design of perovskite air electrodes. In this study, we demonstrated the limited effectiveness of using configuration entropy (Sconfig) and other single atomic features as direct activity descriptors. Instead, we proposed a BOSR model, enhanced by an MoE ensemble approach, which revealed that catalytic activity is primarily governed by the co-expression of multiple material properties. Through our high-throughput screening, we identified three new promising candidates: PLNSY, PLGNSY, and PLGNCSY, all of which exhibited significantly enhanced activity and durability compared to the well-established PrBaCo2O5+δ (PBC). Operando characterizations, along with DFT and AIMD simulations, confirmed that PLNSY, in particular, features a disordered distribution of a larger number of oxygen vacancies, facilitating efficient charge carrier diffusion within a 3D delocalized network. Moreover, we validated that a combination of first ionization energy, relative atomic mass, and ionic Lewis acidity strength were key factors contributing to material stability, providing a more comprehensive descriptor of long-term performance. This work not only elucidates the complex interactions of material properties that drive catalytic activity but also offers valuable insights for the rational design of future oxide electrocatalysts.

Methods

Chemicals

Praseodymium (III) nitrate hexahydrate (Pr(NO3)3·6H2O, 99.99% REO), yttrium (III) nitrate hexahydrate (Y(NO3)3·6H2O, 99.999% REO), lanthanum (III) nitrate hexahydrate (La(NO3)3·6H2O, 99.99% REO), samarium nitrate hexahydrate (H12N3O15Sm, 99.99% REO), neodymium nitrate hexahydrate (H12N3NdO15, 99.99% REO) were purchased from Anhui Senrise Technology Co., Ltd. Gadolinium (III) nitrate hexahydrate (GdN3O9·6H2O, 99.9% metals basis), cobalt nitrate hexahydrate (Co(NO3)2·6H2O, 99.99% metals basis), cerium nitrate hexahydrate (CeN3O9·6H2O, 99.95% metals basis) were purchased from Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. Citric acid (CA, ≥99.5%), ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA, AR), potassium iodide (KI, ≥99.0%), sodium thiosulfate (Na2S2O3, 99%) were provided by Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Co., Ltd. Ammonium hydroxide aqueous solution (NH3·H2O, AR), hydrochloric acid (HCl, AR), ethanol absolute (C2H6O, GR) were supplied by Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. Barium nitrate (Ba(NO3)2, AR) was purchased from Xilong Scientific Co., Ltd.

Synthesis of materials

The perovskite samples in this study were synthesized using a modified sol-gel method. In a typical synthetic, nitrate precursors, citric acid, and EDTA were dissolved in deionized water in a 1:1.5:1 molar ratio of metal ions, citric acid, and EDTA. Ammonia was then added to adjust the PH to 8. The resulting gel was dried at 200 °C to obtain black precursors, which were subsequently calcined at 1100 °C for 2 h to produce the final samples.

Fabrication of symmetrical and single cells

La0.8Sr0.2Ga0.83Mg0.17O3-δ (LSGM) electrolyte pellets with a thickness of ~260 μm were prepared using tape casting. The cathode slurry was prepared by manually milling the cathode powder with ethyl cellulose and terpineol (mass ratio of 1:1.5), which was then screen-printed (disc-shaped) onto both sides of the LSGM disks and calcinated at 1100 °C for 2 h in air. The effective electrode area of each cell was ~0.5 cm2, and the thickness of the electrode was ~20 μm. After that, Ag paste was screen-printed onto the electrode surfaces as the current collector and sintered at 600 °C for 1 h.

High-temperature CO2 electrolysis was carried out using an LSGM electrolyte-supported single cell. Anode and cathode slurries were applied to the LSGM electrolyte via screen printing. The effective electrode area of each cell was ~0.5 cm2, and the thickness of the electrode was ~20 μm. After applying the anode slurry centrally onto the LSGM and calcining at 1100 °C for 2 h, electrospun LSCF fibers37 were mechanically mixed with Ru-SDC28 in a 1:1 mass ratio. This mixture was blended with ethyl cellulose and terpineol to form the cathode slurry, which was applied and calcined at 1050 °C for 2 h. Ag paste was screen-printed onto the electrode surfaces as the current collector and sintered at 600 °C for 1 h, completing the fabrication of the LSGM electrolyte-supported CO2 electrolysis cell.

The NiO/BZCYYb anode-supported half-cells were produced using a two-step dry pressing technique followed by high-temperature heat treatment. In detail, the anode materials were created by grinding NiO (Aladdin Chemical Reagent, China), BZCYYb, and corn starch together at a mass proportion of 7:3:1. BZCYYb electrolyte materials were uniformly spread across the anode substrate surface, then heat-treated at 1450 °C for 10 h in air. Lastly, the cathode mixture was applied to the BZCYYb layer’s center and heat-treated at 1050 °C for 2 h in air8.

Materials characterizations

X-ray diffraction (XRD) was performed using a Rigaku Ultima IV with Cu Kα radiation to investigate the crystal structure of the samples. Rietveld refinements of the XRD data were conducted using GSAS-EXPGUI software. The morphology and elemental distribution of the powders, as well as cross-sectional views of the symmetrical cells, were characterized using a scanning electron microscope (SEM) equipped with an energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) system (GeminiSEM 500). High-resolution morphology was analyzed using a high-resolution transmission electron microscope (HRTEM, FEI Tecnai F30 TWIN). X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, Thermo Scientific K-Alpha) was used to examine the surface chemistry of elements. All XPS data were calibrated using the C 1 s peak at 284.8 eV as a reference and fitted using Avantage software.

The oxygen non-stoichiometry and average valence state of Co were determined via iodometric titration. A starch solution (5 g L−1) was used as an endpoint indicator, resulting in a sharp color change upon completion of the titration. The entire titration process was conducted under a nitrogen (N2) atmosphere. The values of δ (oxygen non-stoichiometry) and Coz⁺ were calculated based on the consumption of thiosulfate solution (details provided in Supplementary Note 8). Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was performed using a TGA5500 instrument over a temperature range of 50 °C to 800 °C in a flowing air atmosphere.

A dense bar was prepared by dry pressing the powders and sintering at 1175 °C for 12 h in air to measure the thermal expansion coefficient, electrical conductivity (S), oxygen surface exchange coefficient (Kchem), and bulk diffusion coefficient (Dchem). The electrical conductivities were measured using the four-probe DC mode under flowing air (100 ml min−1) over a temperature range of 600-800 °C, with a high-precision digital multimeter (Keithley 2050, USA). Thermal expansion coefficients were measured by high precision dilatometer (PCY-G, Xiangyi, China). The Kchem and Dchem were fitted using MATLAB software from data obtained through electrical conductivity relaxation (ECR) measurements. Details of the ECR test and fitting process are provided in Supplementary Note 9.

Soft X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) characterization for the O K edge was conducted in total electron yield (TEY) mode at the National Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory (NSRL, China). Co K edge XANES and XAFS spectra were collected in the transmission mode at the hard X-ray microanalysis (HXMA) beamline at the Canadian Light Source. In situ, time-of-flight neutron powder diffraction (TOF NPD) was performed using the Multi-Physics Instrument (MPI) at the China Spallation Neutron Source (CSNS). Oxygen occupancy information was derived through Rietveld refinement of the TOF NPD data using GSAS II software.

Electrochemical testing

The electrochemical impedance spectra (EIS) of the symmetric cell were acquired using an IVIUM Vertex potentiostat, with an AC amplitude of 10 mV over a frequency range of 100 kHz to 0.1 Hz under open-circuit conditions. The oxygen partial pressure in the gas stream was controlled by mixing nitrogen and oxygen using mass flow controllers (Sevenstar, D007-7). The Distribution of Relaxation Time (DRT) was used to further analyze the EIS data via DRT tools38.

Electrochemical tests of the protonic ceramic fuel cells (PCFCs) were conducted in an electrically heated furnace equipped with a temperature controller, within an environmental chamber. The electrochemical performance of the cells was evaluated at temperatures ranging from 500 to 650 °C, using wet hydrogen (H2) as the fuel (80 mL min−1 flow rate) and ambient air as the oxidant. Linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) was performed to obtain the current-voltage (I-V) curve and maximum power density (MPD). All voltage was not iR corrected. The area-specific resistance (ASR) of the single cell was measured under open-circuit conditions.

High-temperature CO2 electrolysis tests were performed at 800 °C using an LSGM-based single cell. Pure CO2 was supplied to the cathode at a flow rate of 60 mL min−1, while the anode was exposed to static air. LSV was used to obtain the current-voltage (I-V) curve.

To achieve a more accurate measurement of polarization resistance in proton-conducting electrolytes, a series of symmetric cells based on BZCYYb electrolyte (with an active electrode area of 0.5 cm²) was fabricated. Platinum paste and several air electrode materials were applied to the center of both sides of the electrolyte via screen printing, with Ag mesh used as current collectors. The impedance spectra of the Pt/BZCYYb/Pt symmetric cells were measured under 3% wet air and a wet 5% H₂/N₂ atmosphere to determine the contributions of hole and ionic conductivity at various temperatures. LSV scans from -0.01 to 0.01 V were performed on several symmetric air electrodes under the two atmospheres to obtain DC resistance, and impedance spectra were recorded. Calibration and calculation details are provided in Supplementary Note 6.

Calculation details for DFT

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed using the projector augmented wave (PAW) method, as implemented in the VASP code39. The exchange and correlation effects were described using the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) functional40 within the generalized gradient approximation (GGA). A plane-wave cutoff energy of 400 eV was consistently applied in all computations.

Structural optimization was conducted by fixing the bottom atomic layer to achieve minimal total energy. The convergence criteria included an energy threshold of less than 1 × 10⁻⁵ eV for self-consistent field iterations and a force threshold of 0.05 eV Å−1 for geometry optimization. Van der Waals interactions were incorporated using the DFT-D3 method41.

Transition states were located using the Nudged Elastic Band (NEB) method42, which is effective for mapping the minimum energy paths between initial and final states. We employed eight intermediate images between the initial and final states, applying spring forces to ensure equal spacing along the reaction coordinate. The climbing image approach was also utilized to refine the transition state by driving the highest energy image towards the saddle point43. Each image was optimized until the forces on atoms were less than 0.05 eV Å−1, with the highest energy point along the NEB path identified as the transition state.

A Hubbard-like term, U, was introduced to account for on-site Coulombic interactions. Effective U values of 4.5 eV for Nd, Pr, and Sm, and 3.3 eV for Co were used based on previous studies.

For surface calculations, a BaPrCoO (101) slab model was constructed. The unit cell dimensions were 8.58 × 7.80 Å, with a 15 Å vacuum separating four layers of BaPrCoO. The top two layers were relaxed, while the bottom two layers were fixed. A Monkhorst-Pack k-point mesh of 3 × 3 × 1 was used for Brillouin zone integration.

To identify the most stable La-BaPrCoO configuration, we used the Special Quasi-random Structure (SQS) method based on experimental element ratios. For the La-BaPrCoO (101) model, the unit cell size was 10.92 × 19.49 Å, with a Monkhorst-Pack k-point mesh of 1 × 1 × 1 for Brillouin zone integration.

The computational hydrogen electrode (CHE) approach, developed by Nørskov’s group44,45,46, was employed to evaluate thermodynamic properties. The adsorption-free energy was computed using the equation (1):

\(\triangle {G}_{{ads}}={G}_{{facet}+g}{-}{G}_{{facet}}{-}{G}_{g}\) where \({G}_{{facet}+g},{G}_{{facet}}\), and Gg represent the free energies of the species adsorbed on the surface, the clean surface, and the species in the gas phase, respectively.

To comprehensively explore proton diffusion pathways, Ab Initio Molecular Dynamics (AIMD) simulations were conducted within the canonical (NVT) ensemble44,45, utilizing Nosé-Hoover thermostats. The simulations were performed with a time step of 1 fs over a duration of 28 ps.

Computational details for MC/MD

To investigate the effect of entropy on the thermal stability of the oxides, we performed hybrid Monte Carlo (MC)/molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of two oxides at 1073 K using the open-source Large-scale Atomic/Molecular Massively Parallel Simulator (LAMMPS)47. Interactions between ions were modeled using long-range Coulomb interactions calculated via Ewald summation, along with a short-range Buckingham pair potential. The formal charge values were +2, +3, +3, +1.8, +3, +2, +1.8, and −2 for Ba, Pr, Co, La, Nd, Sm, Y, and O, respectively. Buckingham potential parameters were taken from previous studies. The time step was set to 2 fs, and the cutoff radius was 10.0 Å.

The initial configuration of the low-entropy oxide had a nominal atomic ratio of BaPrCo2O6 with a cubix box containing 24000 atoms. Periodic boundary conditions (PBC) were applied in all three dimensions. Based on the low-entropy oxide model, we obtained the initial configuration of the high-entropy oxide by randomly replacing the Pr atoms according to the preset ratio (Pr0.05La0.4Nd0.2Sm0.1Y0.25). The crystallographic structures of both initial configurations were identical, allowing us to examine the effect of entropy. Energy minimization was performed using the conjugate gradient (CG) algorithm, iteratively adjusting ionic positions and optimizing cells. For every 20 MD steps, an additional MC cycle was added. A total of 1,000,000 MC cycles were performed at 1073 K for the two representative models. This hybrid approach enabled local atom swaps during the MC steps, while the MD integration steps ensured relaxations. This method provides greater structural relaxation at a given temperature compared to the stand-alone MD approach48. Temperature and pressure were controlled using the Nose-Hover thermostat and Parrinello-Rahmann barostat, respectively. The atomic configurations were visualized using the Ovito package49.

Data pre-preparation for ML

In addition to elemental compositions, we also incorporated elemental features such as electronegativity(χ), ionic radius (R), (first) ionization energy (IE), Lewis acid strength (ISA) and atomic mass (M). Detailed values for each theoretical atomic feature are provided in Supplementary Table 1. These features use weighted values based on elemental compositions. The weight is normalized such that the total weight for the A site is 0.5, the A’ site (Ba) is 0.5, and the B site (Co) is 1.

For example, the radius calculation for a material of the form \(({\rm{A}}^{1}_{{\rm{k}}}{\rm{A}}^{2}_{0.5-{\rm{k}}}{\rm{A}}^{\prime}_{0.5}{{\rm{B}}}_{1}){{\rm{O}}}_{{\rm{X}}}\) is expressed in equation (2):

\({\rm{R}}={{\rm{R}}}_{{{\rm{A}}}^{1}}\times {\rm{k}}+{\text{R}}_{{\text{A}}^{2}}\times \left(0.5-{\rm{k}}\right)+{\text{R}}_{{\text{A}}^{\prime}}\times 0.5+{{\rm{R}}}_{{\rm{B}}}\) The predictive performance outputs were defined as Rp-750, Rp-700, and Rp-650. Prior to model training, all data were normalized using a standard scaler. This scaler was calibrated based on the entire predictive dataset to prevent biases that could arise from the limited distribution range of the training data alone. To improve the interpretability of the model, each data point was incremented by 6.17, which is the absolute value of the minimum plus 0.01, ensuring all values remained positive. This adjustment was particularly crucial for models involving hyperbolas, where the relationships between positive and negative values are inversely correlated.

Training details of symbolic regression

We employed symbolic regression (SR) facilitated by genetic algorithms (GAs), using the gplearn50 Python library for implementation. The adjusted and fixed hyperparameters are detailed in Supplementary Table 3. Notably, we restricted the function set to five basic operators to enhance interpretability. A ‘parsimony coefficient’ was employed to address complexity penalties, with an empirically derived setting of 0.005 to reach a balance between model complexity and the degree of fitting. The ‘const range’ was defined based on the maximum value observed in the training data. We did not partition the data into training and test sets during this phase, as the newly generated descriptor will subsequently undergo generalization testing within an ensemble framework. Note that the division (‘div’) function is “protected division”, which returns a value of 1 when the denominator approaches zero. To avoid this non-linear scenario, we manually excluded any expressions that could result in a denominator of zero.

Settings for Bayesian optimization

We employed Bayesian optimization (BO) derived using the Python skopt (scikit-optimize 0.8.1, https://scikit-optimize.github.io/stable/) library51 to refine the hyperparameters of the GAs, using a Gaussian process optimizer. To ensure an unbiased initial exploration space, we generated 200 initial points through uniform random sampling. In subsequent iterations, we continued to sample 25 points per iteration across 40 iterations, resulting in a total of 1200 sampled points. For a total of 2400 sampled points, we began with the same random 1200 sampled points and conducted 40 iterations with 30 samples each for the BO process.

Details for cross-validation

The initial training set consists of 50 data points, and the possible values for k in an equally divided k-fold cross-validation scheme are 2, 5, 10, and 25. Among these, we selected 5-fold cross-validation as it provides a balanced compromise between the number of folds and the size of data within each fold. This approach ensures that each split contains a sufficient amount of training and validation data while avoiding overly small subsets.

Data availability

All data supporting our findings are available in this paper and its associated supplementary materials (Supplementary Information and Supplementary Data). Source data for the figures and AIMD/MCMD data can be found in the Source Data file and GitHub repository (https://github.com/helaoer/high_entropy). Source data are provided in this paper.

Code availability

The codes used in this study have been deposited in the GitHub repository and Zenodo, which can be found with these following links: https://github.com/helaoer/high_entropy; https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14821901.

References

Liu, Z. et al. Synergistic dual-phase air electrode enables high and durable performance of reversible proton ceramic electrochemical cells. Nat. Commun. 15, 472 (2024).

Lv, H. et al. Promoting exsolution of RuFe alloy nanoparticles on Sr2Fe1.4Ru0.1Mo0.5O6-δ via repeated redox manipulations for CO2 electrolysis. Nat. Commun. 12, 5665 (2021).

Wang, Y. et al. A review of progress in proton ceramic electrochemical cells: material and structural design, coupled with value-added chemical production. Energ. Environ. Sci. 16, 5721–5770 (2023).

Mu, S. et al. Uncovering electron scattering mechanisms in NiFeCoCrMn derived concentrated solid solution and high entropy alloys. Npj Comput. Mater. 5, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-41018-40138-z (2019).

Lee, Y.-L., Kleis, J., Rossmeisl, J., Shao-Horn, Y. & Morgan, D. Prediction of solid oxide fuel cell cathode activity with first-principles descriptors. Energ. Environ. Sci. 4 https://doi.org/10.1039/c1ee02032c (2011).

Hong, W. T. et al. Charge-transfer-energy-dependent oxygen evolution reaction mechanisms for perovskite oxides. Energ. Environ. Sci. 10, 2190–2200 (2017).

Jacobs, R., Mayeshiba, T., Booske, J. & Morgan, D. Material discovery and design principles for stable, high activity perovskite cathodes for solid oxide fuel cells. Adv. Energy Mater. 8, 1702708 (2018).

Zhai, S. et al. A combined ionic Lewis acid descriptor and machine-learning approach to prediction of efficient oxygen reduction electrodes for ceramic fuel cells. Nat. Energy 7, 866–875 (2022).

Li, Z. et al. High-entropy perovskite as a high-performing chromium-tolerant cathode for solid oxide fuel cells. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 14, 24363–24373 (2022).

Han, X. et al. Utilizing high entropy effects for developing chromium‐tolerance cobalt‐free cathode for solid oxide fuel cells. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2304728 (2023).

Liu, Z. et al. High-entropy perovskite oxide: a new opportunity for developing highly active and durable air electrode for reversible protonic ceramic electrochemical cells. Nanomicro Lett. 14, 217 (2022).

Morley, M. et al. Genetic analysis of genome-wide variation in human gene expression. Nature 430, 743–747 (2004).

Schweidler, S. et al. High-entropy materials for energy and electronic applications. Nat. Rev. Mater. 9, 266–281 (2024).

Aamlid, S. S., Oudah, M., Rottler, J. & Hallas, A. M. Understanding the role of entropy in high entropy oxides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 5991–6006 (2023).

Brahlek, M. et al. What is in a name: Defining “high entropy” oxides. APL Mater. 10, 110902 (2022).

Gomez-Bombarelli, R. et al. Design of efficient molecular organic light-emitting diodes by a high-throughput virtual screening and experimental approach. Nat. Mater. 15, 1120–1127 (2016).

Butler, K. T., Davies, D. W., Cartwright, H., Isayev, O. & Walsh, A. Machine learning for molecular and materials science. Nature 559, 547–555 (2018).

Esterhuizen, J. A., Goldsmith, B. R. & Linic, S. Interpretable machine learning for knowledge generation in heterogeneous catalysis. Nat. Catal. 5, 175–184 (2022).

Ouyang, R., Curtarolo, S., Ahmetcik, E., Scheffler, M. & Ghiringhelli, L. M. SISSO: A compressed-sensing method for identifying the best low-dimensional descriptor in an immensity of offered candidates. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2, 083802 (2018).

Shu, W. et al. Structure sensitivity of metal catalysts revealed by interpretable machine learning and first-principles calculations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 8737–8745 (2024).

Augusto, D. A. & Barbosa, H. J. C. in 6th Brazilian Symposium on Neural Networks. 173-178 (Ieee Computer Soc, 2000).

Weng, B. et al. Simple descriptor derived from symbolic regression accelerating the discovery of new perovskite catalysts. Nat. Commun. 11, 3513 (2020). No.

Clark, A. et al. in 39th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML). (2022).

Li, L. et al. Lanthanide-regulating Ru-O covalency optimizes acidic oxygen evolution electrocatalysis. Nat. Commun. 15, 4974 (2024).

Xu, D. et al. An activity descriptor for perovskite oxides in catalysis. Chem. Catal. 2, 1163–1176 (2022).

Sun, H., Xu, X., Song, Y., Zhou, W. & Shao, Z. Designing high‐valence metal sites for electrochemical water splitting. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2009779 (2021). No.

Chen, Y. et al. A highly efficient multi-phase catalyst dramatically enhances the rate of oxygen reduction. Joule 2, 938–949 (2018).

Song, Y. et al. Surface activation by single ru atoms for enhanced high-temperature CO2 electrolysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202313361 (2024).

Kharton, V., Marques, F. & Atkinson, A. Transport properties of solid oxide electrolyte ceramics: a brief review. Solid State Ion. 174, 135–149 (2004).

Sun, C., Hui, R. & Roller, J. Cathode materials for solid oxide fuel cells: a review. J. Solid State Electr. 14, 1125–1144 (2009).

Jang, I. et al. Electrocatalysis in solid oxide fuel cells and electrolyzers. Chem. Rev. 124, 8233–8306 (2024).

Liu, Q. et al. Tailoring ion ordering in perovskite oxide for high-temperature oxygen evolution reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202307057 (2023).

Seymour, I. D. et al. Anisotropic oxygen diffusion in PrBaCo2O5.5 double perovskites. Solid State Ion-.-. 216, 41–43 (2012).

Koo, B. et al. Enhanced oxygen exchange of perovskite oxide surfaces through strain-driven chemical stabilization. Energ. Environ. Sci. 11, 71–77 (2018).

Deng, G., Kang, K., Liu, Y., Wang, C. & Wang, C. C. New oxygen regulation strategy to enhance the oxygen reduction reaction of the Pr0.6Sr0.4Co0.2Fe0.8O3−δ cathode through A-Site High-Entropy Engineering. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 12, 8366–8378 (2024).

Guo, Y.-Q. et al. Impact of synthesis technique on the structure and electrochemical characteristics of Pr0.6Sr0.4Co0.2Fe0.8O3−δ (PSCF) cathode material. Solid State Ion-.-. 193, 18–22 (2011).

Zhang, X. et al. Nanoscale intertwined biphase nanofiber as active and durable air electrode for solid oxide electrochemical cells. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 11, 8592–8602 (2023).

Maradesa, A. et al. Advancing electrochemical impedance analysis through innovations in the distribution of relaxation times method. Joule 8, 1958–1981 (2024).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Grimme, S., Antony, J., Ehrlich, S. & Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 132 https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3382344 (2010).

Henkelman, G., Uberuaga, B. P. & Jónsson, H. A climbing image nudged elastic band method for finding saddle points and minimum energy paths. J. Chem. Phys. 113, 9901–9904 (2000).

Henkelman, G. & Jónsson, H. Improved tangent estimate in the nudged elastic band method for finding minimum energy paths and saddle points. J. Chem. Phys. 113, 9978–9985 (2000).

Liu, Z., Krösschell, R. D. E., Filot, I. A. W. & Hensen, E. J. M. A combined density functional theory and microkinetics simulations study of electrochemical CO2 reduction on Cu8/SnO2(110): The crucial role of hydrogen coverage. Electrochim. Acta 493 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2024.144409 (2024).

Liu, Z., Zong, X., Vlachos, D. G., Filot, I. A. W. & Hensen, E. J. M. A computational study of electrochemical CO2 reduction to formic acid on metal-doped SnO2. Chin. J. Catal. 50, 249–259 (2023).

Yang, S. et al. Near-unity electrochemical CO2 to CO conversion over Sn-doped copper oxide nanoparticles. ACS Catal. 12, 15146–15156 (2022).

Plimpton, S. Fast parallel algorithms for short-range molecular dynamics. J. Comput. Phys. 117, 1–19 (1995).

Zhang, Z., Ding, J. & Ma, E. Shear transformations in metallic glasses without excessive and predefinable defects. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 119, e2213941119 (2022).

Stukowski, A. Visualization and analysis of atomistic simulation data with OVITO–the Open Visualization Tool. Model. Simul. Mat. Sci. Eng. 18, 015012 (2010).

Stephens, T. Introduction to GP-gplearn0.5.dev0 documentation, https://gplearn.readthedocs.io/en/latest/intro.html (2016).

(n.d.)., S.-O. Scikit-Optimize 0.8.1 documentation., https://scikit-optimize.github.io/stable/ (2020).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (nos. 22472134, 22272136, 52272233, 22472137, 22172129, 22472139, U22A20392). X.T. acknowledges funding from the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EP/Z002753/1). Y.S. acknowledges financial support from the Science and Technology Project of Fujian Province (2022L3077) and the Shenzhen Science and Technology Program (JCYJ20240813145707010, JCYJ20220530143401002, JCYJ20241202124410015). Y.S. also thanks the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (no. 20720240074). ANA acknowledges the Research Institute Supporting Program (RICSP-25−1), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia The authors thank Shenzhen HUASUAN Technology Co., Ltd. for assistance on theoretical calculations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.Z., H.H., Z.S., X.T., and Y.S. conceived the idea. X.Z., G.Y., and Y.S. designed the experiments. H.H. designed the machine learning framework and wrote the code. X.Z., Y.C., X.X., and H.L. synthesized the materials. X.Z, C.J., Y.X., S.W., X.Y., and J.Li performed material characterizations and electrochemical measurements. X.X, X.Y., and A.A. performed the DFT calculations. Y.P., N.C., and J.Lin conducted and analyzed synchrotron radiation experiments. Z.S., X.T., and Y.S. supervised the project. X.Z., H.H., S.L., N.Y., X.T., Z.S., Z.C., and Y.S. co-wrote the manuscript. All authors commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, X., He, H., Chen, Y. et al. Co-expression of multi-genes for polynary perovskite electrocatalysts for reversible solid oxide cells. Nat Commun 16, 2868 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-58178-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-58178-7