Abstract

Neural networks posses the crucial ability to generate meaningful representations of task-dependent features. Indeed, with appropriate scaling, supervised learning in neural networks can result in strong, task-dependent feature learning. However, the nature of the emergent representations is still unclear. To understand the effect of learning on representations, we investigate fully-connected, wide neural networks learning classification tasks using the Bayesian framework where learning shapes the posterior distribution of the network weights. Consistent with previous findings, our analysis of the feature learning regime (also known as ‘non-lazy’ regime) shows that the networks acquire strong, data-dependent features, denoted as coding schemes, where neuronal responses to each input are dominated by its class membership. Surprisingly, the nature of the coding schemes depends crucially on the neuronal nonlinearity. In linear networks, an analog coding scheme of the task emerges; in nonlinear networks, strong spontaneous symmetry breaking leads to either redundant or sparse coding schemes. Our findings highlight how network properties such as scaling of weights and neuronal nonlinearity can profoundly influence the emergent representations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The remarkable empirical success of deep learning stands in strong contrast to the theoretical understanding of trained neural networks. Although every single detail of a neural network is accessible and the task is known, it is still very much an open question how the neurons in the network manage to collaboratively solve the task. While deep learning provides exciting new perspectives on this problem, it is also at the heart of more than a century of research in neuroscience.

Two key aspects are representation learning and generalization. It is widely appreciated that neural networks are able to learn useful representations from training data1,2,3. But from a theoretical point of view, fundamental questions about representation learning remain wide open: Which features are extracted from the data? And how are those features represented by the neurons in the network? Furthermore, neural networks are able to generalize even if they are deeply in the overparameterized regime4,5,6,7,8,9 where the weight space contains a subspace—the solution space—within which the network perfectly fits the training data. This raises a fundamental question about the effect of implicit and explicit regularization: Which regularization biases the solution space towards weights that generalize well?

We here investigate the properties of the solution space using the Bayesian framework where the posterior distribution of the weights determines how the solution space is sampled10,11. For theoretical investigations of this weight posterior, the size of the network is taken to infinity. Crucially, the scaling of the network and task parameters, as the network size is taken to infinity, has a profound impact: Neural networks can operate in different regimes depending on this scaling. Here, the relevant scales are the width of the network N and the size of the training data set P. A widely used scaling limit is the infinite width limit where N is taken to infinity while P remains finite12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19. A scaling limit closer to empirically trained networks takes both N and P to infinity at a fixed ratio α = P/N20,21,22,23,24,25,26.

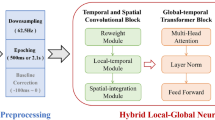

In addition to the scaling of P and N, the scaling of of the final network output with N is important because it has a strong effect on representation learning27,28,29 (illustrated in Fig. 1b,d). If the readout scales its inputs with \(1/\sqrt{N}\) the network operates in the ‘lazy’ regime. Lazy networks rely predominantly on random features, and representation learning is only a 1/N correction both for finite P18,30,31,32,33 and fixed α20 (illustrated in Fig. 1c); in the latter case, it nonetheless affects the predictor variance20,24,25. If the readout scales its inputs with 1/N the network operates in the ‘non-lazy’ (also called mean-field or rich) regime and learns strong, task-dependent representations34,35,36,37,38,39,40 (illustrated in Fig. 1e). However, the nature of the solution, in particular how the learned features are represented by the neurons, remains unclear. Work-based on a partial differential equation for the weights34,35,36,37 only provides insight in effectively low dimensional settings; investigations based on kernel methods38,39,40,41 average out important structures at the single neuron level.

a Sketch of the network with two hidden layers (L = 2) and two outputs (m = 2). b, d Last layer feature space in the lazy regime where predominantly random features are almost orthogonal to the readout weight vector (b) and in the non-lazy regime where learned features are aligned to the readout weight vector (d). c, e Kernels and activations of feature layer neurons in lazy (c) and non-lazy (e) networks for a binary classification task and three neuronal nonlinearities (linear, sigmoidal, and ReLU). For ReLU networks, only the 20 most active neurons are shown. In (e), all three kernels show a similar, pronounced task-learned structure. However, the patterns of activation are strikingly different.

In this paper, we develop a theory for the weight posterior of non-lazy networks in the limit N, P → ∞. We show that the representations in non-lazy networks trained for classification tasks exhibit a remarkable structure in the form of coding schemes, where distinct groups of neurons are characterized by the subset of classes that activate them. Another central result is that the nature of the learned representation strongly depends on the type of neuronal nonlinearity (illustrated in Fig. 1e). We consider three nonlinearities: Linear, sigmoidal, and ReLU leading to analog, redundant, and sparse coding schemes, respectively. We start the manuscript with the learned representations on training inputs in the simple setting of a toy task. Next, we analyze the dynamics in weight space, focusing on spontaneous symmetry breaking. Moving beyond the toy task, we investigate learned representations on training and test inputs and generalization on MNIST and CIFAR10. The paper concludes with a brief summary and discussion of our results.

Results

Non-lazy networks

We consider fully-connected feedforward networks with L hidden layers and m outputs (Fig. 1a)

where ϕ(z) denotes the neuronal nonlinearity, \({z}_{i}^{L}({\boldsymbol{x}})\) the last layer preactivation, and x is an arbitrary N0-dimensional input. The preactivations are \({z}_{i}^{\ell }({\boldsymbol{x}})=\frac{1}{\sqrt{N}}\mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{j=1}^{N}{W}_{ij}^{\ell }\phi [{z}_{j}^{\ell -1}({\boldsymbol{x}})]\) in the hidden layers ℓ = 2, …, L and \({z}_{i}^{1}({\boldsymbol{x}})=\frac{1}{\sqrt{{N}_{0}}}\mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{j=1}^{{N}_{0}}{W}_{ij}^{1}{x}_{j}\) in the first layer. The activations are \(\phi [{z}_{i}^{\ell }({\boldsymbol{x}})]\) and we assume for simplicity that the width of all hidden layers is N. We call the last hidden layer ℓ = L the feature layer.

The trainable parameters of the networks are the readout and hidden weights, which we collectively denote by Θ. The networks are trained using empirical training data \({\mathcal{D}}={\{({{\boldsymbol{x}}}_{\mu } , {{\boldsymbol{y}}}_{\mu })\}}_{\mu=1}^{P}\) containing P inputs xμ of dimension N0 and P targets yμ of dimension m (for classification m is the number of classes). The N0 × P matrix containing all training inputs is denoted by X; the P × m matrix containing all training targets is denoted by Y.

Importantly, the multiplication with 1/N in (1) puts the network in the non-lazy regime; a multiplication with \(1/\sqrt{N}\) corresponds to the lazy regime. The importance of the multiplicative factor can be understood geometrically: In the lazy regime (Fig. 1b), the feature layer activations (called the feature vectors) \(\phi [{z}_{i}^{L}({{\boldsymbol{x}}}_{\mu })]\), i = 1, …, N, are predominantly random resulting in a small overlap of \(O(\sqrt{N})\) with the readout vector which requires a relatively large readout normalization, \(1/\sqrt{N}\). In the non-lazy regime (Fig. 1d), the feature layer activations exhibit a strong learned component, such that they have a large overlap of O(N) with the readout vector, which makes the normalization with 1/N in Eq. (1) appropriate. Put differently, for non-lazy networks, the learned feature vectors and the readout vector are aligned.

To study the properties of the network after learning, we employ a Bayesian framework where, following learning, the parameters Θ are drawn from a posterior distribution \(P(\Theta )=\frac{1}{Z}{P}_{0}(\Theta )\exp \left[-\beta {\mathcal{L}}(\Theta )\right]\) where P0(Θ) is a Gaussian prior, \({\mathcal{L}}(\Theta )\) a mean squared error loss, and Z the normalization constant (see Methods for details). We denote expectations w.r.t. the weight posterior by 〈⋅〉Θ. In the “zero temperature limit” β → ∞ any set of parameters Θ drawn from the posterior corresponds to a network, which perfectly solves the training task.

The geometrical intuition given above about the effect of non-lazy scaling of the output implicitly assumed that the individual components of both the readout vectors as well as the feature vectors are of O(1), hence their norms are of \(O(\sqrt{N})\). However, learning could change the order of magnitude of these norms, for example, during learning the readout weights could grow by a factor \(\sqrt{N}\) which would trivially undo the non-lazy scaling and result in a network operating in the lazy regime, despite the O(1/N) scaling of the output. To control the properties of the network after learning within the Bayesian framework, we adjust in particular the prior variance of the readout weights \({\sigma }_{a}^{2}\) such that all preactivation norms as well as the norm of the readout weights are \(O(\sqrt{N})\). In summary, we consider networks drawn from a weight posterior such that they are perfectly trained and such that the non-lazy scaling is not trivially undone by learning, allowing us to study the salient properties of learning in non-lazy networks.

To understand the properties of the emergent representations, we develop a mean-field theory of the weight posterior. To this end, we consider the limit N, N0, P → ∞ while the number of readout units, as well as the number of layers remain finite, i.e., m, L = O(1). The relation between P and the size parameters will be discussed below.

Kernel and coding schemes

The properties of learned representations are frequently investigated using the kernel20,39,42,43, which measures the overlap between the neurons’ activations at each layer induced by pairs of inputs:

where the inputs x1, x2 can be either from the training or the test set. We denote the posterior averaged kernel by \({{\mathcal{K}}}_{\ell }({{\boldsymbol{x}}}_{1} , {{\boldsymbol{x}}}_{2})={\langle {{\mathcal{K}}}_{\ell }({{\boldsymbol{x}}}_{1} , {{\boldsymbol{x}}}_{2};\Theta )\rangle }_{\Theta }\); the posterior averaged P × P kernel matrix on all training inputs is denoted by Kℓ. In addition to capturing the learned representations, the kernel is a central observable because it determines the statistics of the output function in wide networks12,13,14,15.

Crucially, the kernels are insensitive to how the learned features are represented by the neuronal activations. Consider, for example, binary classification in two extreme cases: (1) Each class activates a single (different) neuron and all remaining neurons are inactive; (2) each class activates half of the neurons and the remaining half of the neurons are inactive. In both scenarios the kernels agree up to an overall scaling factor despite the drastic difference in the underlying representations (illustrated in Fig. 1e).

The central goal of our work is to understand the nature of the representations using a theory that goes beyond kernel properties. To this end, we use the notion of a neural code, which we define as the subset of classes that activate a given neuron (see Table 1). At the population level, this leads to a “coding scheme”: The collection of codes implemented by the neurons in the population. As we will show the coding schemes encountered in our theory are of three types (illustrated in Fig. 1e): (1) Sparse coding where only a small subset of neurons exhibit codes (as in the first scenario above). (2) Redundant coding, where all the codes in the scheme are shared by a large subset of neurons (as in the second scenario above). (3) Analog coding where all neurons respond to all classes but with different strengths.

Surprisingly, the nature of the learned representations varies drastically with the choice of the activation function of the hidden layer, ϕ(z), although the kernel matrix is similar in all cases (Fig. 1e). Specifically, in the linear case, ϕ(z) = z, the coding is analog, in the sigmoidal case, \(\phi (z)=\frac{1}{2}[1+{\rm{erf}}(\sqrt{\pi }z/2)]\left.\right)\), the coding is redundant, and in the case of ReLU, \(\phi (z)=\max (0 , z)\), the coding is sparse.

Main theoretical result

To explain the emergence of the coding schemes, we have derived a mean-field theory for the kernels, the learned representations, the input-output function (predictor statistics) as well as the performance of the networks, which applies to general distributions of inputs and outputs (see supplements A-C). To illustrate the theoretical predictions regarding the learned representations, we first employ a toy classification task where all inputs xμ are mutually orthogonal, \(\frac{1}{{N}_{0}}{{\boldsymbol{x}}}_{\mu }^{\top }{{\boldsymbol{x}}}_{\nu }={\delta }_{\mu \nu }\), and the class memberships are randomly assigned. The corresponding targets yμ are one-hot encoded: If xμ belongs to the r-th class, the r-th element of yμ is y+, and all other elements are y−. The simplicity of the data allows for extensive numerical evaluations across parameters. Later, we will show results for MNIST44 and CIFAR1045 image classification, where representations of both training and test inputs are shown, and the consequences for the generalization performance are investigated.

A general, remarkable outcome of the theory is that the joint posterior of the readout weights and the activations factorizes across neurons and layers,

where ai denotes the m-dimensional vector containing the readout weights for neuron i and \({{\boldsymbol{z}}}_{i}^{\ell }\) denotes the P-dimensional vector containing the preactivations of neuron i on all training inputs. Importantly, while the feature layer representations \({{\boldsymbol{z}}}_{i}^{L}\) depend on the corresponding readout vector, ai, the distribution of the activations of previous layers are completely decoupled, so that even when the readout and top layers break permutation symmetry, this broken symmetry does not affect lower layers as we will see below. The form of the posteriors of both readout weights and preactivations depends on the nature of the neuronal activation functions. Below we present the key results of the theory for the different activation functions (further details in supplements A-C for linear, sigmoidal, and ReLU, respectively).

Analog coding scheme

We begin with linear networks ϕ(z) = z. In this case, the single neuron readout posterior P(ai) is Gaussian, \(P({{\boldsymbol{a}}}_{i})={\mathcal{N}}({{\boldsymbol{a}}}_{i}\,| \,{\boldsymbol{0}} , {\boldsymbol{U}})\), where U is a m × m matrix determined by \({{\boldsymbol{U}}}^{L+1}={\sigma }_{a}^{2L}{{\boldsymbol{Y}}}^{\top }{{\boldsymbol{K}}}_{0}^{-1}{\boldsymbol{Y}}\) with the input kernel \({{\boldsymbol{K}}}_{0}=\frac{1}{{N}_{0}}{{\boldsymbol{X}}}^{\top }{\boldsymbol{X}}\). Because \({{\boldsymbol{Y}}}^{\top }{{\boldsymbol{K}}}_{0}^{-1}{\boldsymbol{Y}}=O(P)\), where P is the size of the training set, the predicted norm-squared of the posterior readout weights grows with \({\sigma }_{a}^{2L}P\) where \({\sigma }_{a}^{2}\) is the readout weights variance of the prior and L is the network depth. Hence, to prevent growth of the norm of the readout weights with P we set \({\sigma }_{a}^{2}=1/{P}^{1/L}\). Furthermore, the posterior mean of the feature layer activations \({{\boldsymbol{z}}}_{i}^{L}\), conditioned on ai, is YU−1ai, where Y is the training label matrix, yielding an analog coding of the task where the strength of the code is determined by the strength of the Gaussian distributed readout weight ai.

For linear networks, the single neuron posterior of the activations in the lower layers ℓ < L is a multivariate Gaussian: \(P({{\boldsymbol{z}}}_{i}^{\ell })={\mathcal{N}}({{\boldsymbol{z}}}_{i}^{\ell }\,| \,{\boldsymbol{0}} , {{\boldsymbol{K}}}_{\ell })\) for ℓ = 1, …, L − 1, where the covariance is given by the kernel matrix \({{\boldsymbol{K}}}_{\ell }={{\boldsymbol{K}}}_{0}+{\sigma }_{a}^{2(L-\ell )}{\boldsymbol{Y}}{{\boldsymbol{U}}}^{-(L-\ell+1)}{{\boldsymbol{Y}}}^{\top }\) consisting of a contribution K0 due to the prior and a learned low-rank contribution \({\sigma }_{a}^{2(L-\ell )}{\boldsymbol{Y}}{{\boldsymbol{U}}}^{-(L-\ell+1)}{{\boldsymbol{Y}}}^{\top }\). The strength of the learned part increases across layers, \({\sigma }_{a}^{2(L-\ell )}=1/{P}^{1-\frac{\ell }{L}}\). In the last layer, it is O(1), indicating that even in the linear case the network learns strong features with a strength that increases across layers, culminating in an O(1) contribution in the feature layer. This is in strong contrast to the lazy case where the learned contribution to the kernels is suppressed by 1/N in all layers20.

A sample of the analog coding scheme is shown in Fig. 2b for the single-hidden-layer network on the toy classification task. For the task, we use three classes with unequal proportions: half of the training inputs belong to the first class, and the remaining inputs belong to the other two classes with equal ratios. The corresponding structure is clearly recognizable in the activations. Furthermore, the activations are sorted by their mean squared activity, which shows the analog nature of the code: There is a continuous gradient from weakly to strongly coding neurons. In line with the Gaussian readout posterior, the readout vectors display no clear structure (Fig. 2a), but in combination with the activations, they are perfectly adjusted to solve the task (Fig. 2c).

a Sample of the readout weight vectors of all three classes. For ReLU, only readout weights of the nine most active neurons are shown. b Activations on all training inputs for a given weight sample. For ReLU, only the nine most active neurons are shown. c Network output for the weighted sample shown in (a, b). The output perfectly matches the one-hot coding of the task where the first half of the inputs belong to the first class, and the remaining inputs belong to the two remaining classes with equal proportions.

We show a sample of the lower layer activations in Fig. 3 for a three-hidden-layer network and the toy task with three classes. In contrast to the feature layer activations (Fig. 3c), the learned structure is hardly apparent in the first layers (Fig. 3a, b). Corresponding to the theory, the learned low-rank contribution to the kernel increases in strength across layers (Fig. 3d–f) until the kernel perfectly represents the task in the last layer.

Redundant coding scheme

We now consider nonnegative sigmoidal networks, \(\phi (z)=\frac{1}{2}[1+{\rm{erf}}(\sqrt{\pi }z/2)]\). To avoid growth of the readout weights with P we must choose \({\sigma }_{a}^{2}=1/P\) for arbitrary depth (see supplement B).

With sigmoidal nonlinearity, the readout posterior is drastically different from Gaussian: It is a weighted sum of Dirac deltas \(P({{\boldsymbol{a}}}_{i})=\mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{\gamma=1}^{n}{P}_{\gamma }\delta ({{\boldsymbol{a}}}_{i}-{{\boldsymbol{a}}}_{\gamma })\) where the weights Pγ and the m-dimensional vectors aγ are determined jointly for all γ = 1, …, n by a set of self-consistency equations which depend on the training set (see supplement B.1). This means that the vector of readout weights is redundant: Each of the N neurons chooses one of n possible readout weights aγ with a probability Pγ. The number of distinct readout weights n determines the number of codes employed by the network.

The readout weights ai determine the last layer preactivation \({{\boldsymbol{z}}}_{i}^{L}\) through the single neuron conditional distribution \(P({{\boldsymbol{z}}}_{i}^{L}\,| \,{{\boldsymbol{a}}}_{i})\). Due to the redundant structure of the readout posterior, a redundant coding scheme emerges in which, on average, a fraction Pγ of the neurons exhibit identical preactivation posteriors \(P({{\boldsymbol{z}}}_{i}^{L}\,| \,{{\boldsymbol{a}}}_{\gamma })\). These posteriors have pronounced means that reflect the structure of the task and the code but also significant fluctuations around the mean which do not vanish in the limit of large N and P (see Fig. 4c).

a Readout weight posterior on first class; theoretical distribution as black dashed line (for sigmoidal networks with finite P correction, see supplement B.1). b Readout weight dynamics for selected neurons during sampling. c Last-layer-preactivation posterior on inputs from the first class; theoretical distribution as black dashed line. For sigmoidal and ReLU networks distributions conditioned on selected codes are shown. d Last-layer-preactivation dynamics during sampling. Neurons selected corresponding to the distributions shown in c. preact., preactivation.

For the single-hidden-layer network on the toy task with three classes, the redundant coding of the task is immediately apparent (Fig. 2b) but also the remaining fluctuations across inputs from the same class are visible. In this example, there are four codes: 1-1-0, 0-1-1, 1-0-1, and 1-1-1. Note that the presence of code 1-1-1, which is implemented only by a small fraction of neurons, is accurately captured by the theory (Fig. 4a middle peak). The relation between the neurons’ activations and their readout weights is straightforward: For neurons with code 1-1-0, the readout weights are positive for classes 0 and 1 and negative for class 2 (Fig. 2a), and vice versa for the other codes, leading to a perfect solution of the task (Fig. 2c).

Clearly, this coding scheme with four codes is not a unique solution. Indeed, the theory admits other coding schemes which are, however, unlikely to occur (see supplement B.1). Interestingly, the details of the coding scheme depend on the choice of values for the targets \({y}_{\mu }^{r}\); for example, increasing y− from 0.1 to 0.5 in the above toy task leads to successive transitions between four different coding schemes (see supplement E).

The posterior of the preactivations \(P({{\boldsymbol{z}}}_{i}^{\ell })\) in the lower layers ℓ < L is multimodal with each mode corresponding to a code (see supplement B.1). Since all neurons sample independently from \(P({{\boldsymbol{z}}}_{i}^{\ell })\), a redundant coding scheme emerges where all neurons coming from the same mode of \(P({{\boldsymbol{z}}}_{i}^{\ell })\) share their code. Due to the appearance of a coding scheme in the activations, the corresponding kernels posses a strong low-rank component reflecting the task. We use the toy task and a three-hidden-layer network to show the redundant coding schemes across layers (Fig. 3a–c) and the corresponding kernels (Fig. 3d–f). For the feature layer representations, the main impact of the increased depth is a reduction of fluctuations across inputs from the same class (Fig. 2b vs. Fig. 3c)—the coding scheme “sharpens”. Across layers, the coding scheme sharpens from the input to the feature layer (Fig. 3a–c). Furthermore, the coding scheme can vary across layers, e.g., there are five codes in the first layer (Fig. 3a) and six codes in the second and third layers (Fig. 3b, c).

Sparse coding scheme

Last, we consider ReLU networks, \(\phi (z)=\max (0 , z)\). Here we set \({\sigma }_{a}^{2}=1/{P}^{1/L}\) as in the linear case owing to the homogeneity of ReLU. For the theory we consider only single-hidden-layer networks L = 1.

The nature of the readout posterior is fundamentally different compared to the previous two cases: It factorizes into a small number n = O(1) of outlier neurons and a remaining bulk of neurons, \(\mathop{\prod }\nolimits_{i=1}^{n}[{P}_{i}({{\boldsymbol{a}}}_{i})]\mathop{\prod }\nolimits_{i=n+1}^{N}[P({{\boldsymbol{a}}}_{i})]\). The readout posteriors of the outlier neurons i = 1, …, n are Dirac deltas at \(O(\sqrt{N})\) values, \({P}_{i}({{\boldsymbol{a}}}_{i})=\delta ({{\boldsymbol{a}}}_{i}-\sqrt{N}{\bar{{\boldsymbol{a}}}}_{i})\). For the bulk neurons i = n + 1, …, N, the readout weight posterior is a single Dirac delta with a probability mass of O(1), P(ai) = δ(ai − a0). The values of a0 and \({\bar{{\boldsymbol{a}}}}_{i}\) are determined self-consistently (see supplement C.1).

The feature layer representations are determined by the conditional distribution of the preactivations. For the outliers, the preactivation posterior is a Dirac delta at \(O(\sqrt{N})\) values, \(P({{\boldsymbol{z}}}_{i}\,| \,\sqrt{N}{\bar{{\boldsymbol{a}}}}_{i})=\delta ({{\boldsymbol{z}}}_{i}-\sqrt{N}{\bar{{\boldsymbol{z}}}}_{i})\). Thus, for the n = O(1) outlier neurons the \(O(\sqrt{N})\) preactivations and readout weights exploit the homogeneity of the activation function to jointly overcome the non-lazy scaling. All N − n neurons of the bulk are identically distributed according to a non-Gaussian posterior P(zi ∣ a0), which means that the neurons from the bulk share the same code.

In total, the bulk and outliers provide n + 1 codes. Since m codes are necessary to solve a task, the minimal number of outliers is n = m − 1; if the bulk is task agnostic the minimal number of outliers increases to n = m. On the toy task with three classes, the latter occurs: There are three outliers coding for a single class each while the bulk is largely task agnostic (Fig. 2b). The relation between outlier readout weights and activations is straightforward: Readout weights for the outlier neurons are positive for the coded class and negative otherwise (Fig. 2a) leading in combination to a perfect solution of the task (Fig. 2c).

We investigate deeper ReLU networks only empirically. For a three-hidden-layer network on the toy task, all layers display task-dependent representations (Fig. 3a–c): The first layer displays a sparse coding scheme with two outlier neurons coding for the second and third class and a bulk which is active on all classes, the second layer a coding scheme with redundant outliers coding for the first and second class, and the feature layer a sparse coding scheme with three outlier neurons coding for one class each as in the single-hidden-layer case. Corresponding to the task-dependent representations, the kernels posses low-rank components in all layers, which increase in strength towards the feature layer (Fig. 3d–f). For the feature layer representations, increasing the depth has no effect: Already for a single hidden layer there are no fluctuations across inputs from the same class, thus the sparse coding scheme cannot sharpen, unlike the redundant coding scheme in sigmoidal networks.

Dynamics

So far, we considered a single sample drawn from the weight posterior to reveal the structure of a typical solution. Next, we investigate the impact of this structure on the dynamics of readout weights and representations during sampling from the posterior.

For linear networks, the posteriors of both readout weights (Fig. 4a) and activations (Fig. 4c) are Gaussian and thus unimodal. During sampling, their single peak is fully explored by any given readout weight (Fig. 4b) and activation (Fig. 4d).

In sigmoidal networks the readout posterior splits into disconnected branches (Fig. 4a). This leads to a fundamental consequence of the theory: For any given neuron sampling is restricted to one of the branches of the posterior (Fig. 4b), i.e., ergodicity is broken. Since the readout weights determine the code through the conditional distribution \(P({{\boldsymbol{z}}}_{i}^{L}\,| \,{{\boldsymbol{a}}}_{\gamma })\) (Fig. 4c), fixing the readout weights implies fixing the code, despite the non-vanishing fluctuations of preactivations (Fig. 4d). This has an important consequence for the permutation symmetry of fully connected networks: The permutation symmetry cannot be restored dynamically. In the linear case, all permutation symmetric solutions are visited during sampling, i.e., permutation symmetry is restored through the dynamics, while in the sigmoidal case, the neurons cannot permute across codes, and the permutation symmetry remains broken.

Remarkably, there is a fundamental difference between the lower layers and the feature layer in sigmoidal networks: In the feature layer, a neuron’s code is fixed, but not in the lower layers (Fig. 5). This can be understood from the factorization of the posterior across layers, Eq. (3), where the lower layers are decoupled from the feature layer and thus not affected by the permutation symmetry breaking in the feature layer. Although the individual neurons change their code during sampling, the global structure of the code is preserved: For each weight sample, the neurons can be reordered such that the coding scheme is apparent (Fig. 5c, d).

Similar to the sigmoidal case, the readout posterior of ReLU networks splits into disconnected branches which correspond to the bulk and the outliers (Fig. 4a). Again, this implies ergodicity breaking: During sampling the readout weights are restricted to their branch of the posterior (Fig. 4b). Corresponding to the fixed readout weights also the code is fixed: The outlier neurons do not permute, and the bulk neurons remain in the bulk during sampling (Fig. 4d). In contrast to the sigmoidal case and the bulk neurons, the activations of outlier neurons freeze as well; otherwise fluctuations cannot average out across neurons in the final readout. While the details between sigmoidal and ReLU networks differ, in both cases, permutation symmetry is broken.

Generalization

Going beyond the training data, we investigate generalization to unseen test inputs. We consider both the representations of the test inputs, quantified by the posterior-averaged kernel \({{\mathcal{K}}}_{\ell }({{\boldsymbol{x}}}_{1} , {{\boldsymbol{x}}}_{2})={\langle {{\mathcal{K}}}_{\ell }({{\boldsymbol{x}}}_{1} , {{\boldsymbol{x}}}_{2};\Theta )\rangle }_{\Theta }\), as well as the generalization performance of the mean predictor \({f}_{r}({\boldsymbol{x}})={\langle {f}_{r}({\boldsymbol{x}};\Theta )\rangle }_{\Theta }\).

To extend the theory to account for test inputs, we include the P* dimensional vector of test activations \({{\boldsymbol{z}}}_{i}^{\ell ,*}\) with elements \({z}_{i}^{\ell }({{\boldsymbol{x}}}_{\mu }^{*})\) on a set of test inputs \({{\boldsymbol{x}}}_{\mu }^{*}\), μ = 1, …, P*, in the joint posterior. The joint posterior still factorizes across neurons and layers into single neuron posteriors \(P({{\boldsymbol{z}}}_{i}^{L ,*} | {{\boldsymbol{z}}}_{i}^{L})P({{\boldsymbol{z}}}_{i}^{L} | {{\boldsymbol{a}}}_{i})P({{\boldsymbol{a}}}_{i})\) in the last layer and \(P({{\boldsymbol{z}}}_{i}^{\ell ,*}| {{\boldsymbol{z}}}_{i}^{\ell })P({{\boldsymbol{z}}}_{i}^{\ell })\) in the previous layers ℓ < L. For all nonlinearities, the distribution of the test preactivations conditioned on the training preactivations, \(P({{\boldsymbol{z}}}_{i}^{\ell ,*}| {{\boldsymbol{z}}}_{i}^{\ell })\), is Gaussian in all layers ℓ = 1, …, L (see supplements A.2, B.2, C). This allows to compute the mean predictor as well as the kernel on arbitrary inputs.

An important result of the theory is that the fluctuations of the predictor \({\langle \delta {f}_{r}{({\boldsymbol{x}};\Theta )}^{2}\rangle }_{\Theta }\) can be neglected, unlike in lazy networks20. This implies that the (non-negative) variance contribution from the bias-variance decomposition \({\langle {[ {y}_{\mu}^{r}-{f}_{r}({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\mu};\Theta )]}^{2}\rangle }_{\Theta }={[ {y}_{\mu}^{r}-{f}_{r}({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\mu})]}^{2}+{\langle \delta {f}_{r}{({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\mu};\Theta )}^{2}\rangle }_{\Theta }\) is absent in the generalization error \({\varepsilon }_{r}=\frac{1}{{P}_{*}}\mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{\mu=1}^{{P}_{*}}{\langle {[\, {y}_{\mu }^{r ,*}-{f}_{r}({{\boldsymbol{x}}}_{\mu }^{*};\Theta )]}^{2}\rangle }_{\Theta }\). The remaining generalization error \({\varepsilon }_{r}=\frac{1}{{P}_{*}}\mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{\mu=1}^{{P}_{*}}{[{y}_{\mu}^{r}-{f}_{r}({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\mu})]}^{2}\) is, therefore, reduced compared to the lazy case.

For linear networks, the mean predictor evaluates to \({\boldsymbol{f}}({\boldsymbol{x}})={{\boldsymbol{Y}}}^{\top }{{\boldsymbol{K}}}_{0}^{-1}{{\boldsymbol{k}}}_{0}({\boldsymbol{x}})\) with \({{\boldsymbol{k}}}_{0}({\boldsymbol{x}})=\frac{1}{{N}_{0}}{{\boldsymbol{X}}}^{\top }{\boldsymbol{x}}\) and \({{\boldsymbol{K}}}_{0}=\frac{1}{{N}_{0}}{{\boldsymbol{X}}}^{\top }{\boldsymbol{X}}\) and the posterior averaged kernel is \({{\mathcal{K}}}_{\ell }({{\boldsymbol{x}}}_{1} , {{\boldsymbol{x}}}_{2})={\kappa }_{0}({{\boldsymbol{x}}}_{1} , {{\boldsymbol{x}}}_{2})+{\sigma }_{a}^{2(L-\ell )}{\boldsymbol{f}}{({{\boldsymbol{x}}}_{1})}^{\top } {{\boldsymbol{U}}}^{-(L-\ell+1)} {\boldsymbol{f}}({{\boldsymbol{x}}}_{2})\) with \({\kappa }_{0}({{\boldsymbol{x}}}_{1} , {{\boldsymbol{x}}}_{2})=\frac{1}{{N}_{0}}{{\boldsymbol{x}}}_{1}^{\top }{{\boldsymbol{x}}}_{2}\) (see supplement A.2). The test kernel is identical to the training kernel except that the training targets are replaced by the predictor. As in the training kernel, the learned part is low rank and becomes more prominent across layers, reaching O(1) in the last layer. Remarkably, despite the strong learned representations, the mean predictor is identical to the lazy case20 and the Gaussian Process (GP) theory (see supplement D.3). In contrast to the lazy case, the variance of the predictor can be neglected (see supplement A.3).

We apply the theory to the classification of the first three digits of MNIST. The nature of the solution is captured by an analog coding scheme, as in the toy task, which generalizes to unseen test inputs (Fig. 6a). The generalization of the representations is confirmed by the test kernel which has a block structure corresponding to the task (Fig. 6b). Also the mean predictor generalizes well (Fig. 6c) and the class-wise generalization error is reduced compared to the GP theory (Fig. 6d). Since the mean predictors are identical for non-lazy networks and the GP theory, the reduced generalization error is exclusively an effect of the reduced variance of the predictor.

a Activations of all neurons on 100 test inputs for a given weight sample; for ReLU only the ten most active neurons are shown. b Posterior-averaged kernel on 100 test inputs. c Mean predictor for class 0 from sampling (gray) and theory (black dashed). d Generalization error for each class averaged over 1000 test inputs from sampling (gray bars), theory (black circles), and GP theory (back triangles). gen. error, generalization error.

For sigmoidal networks, the mean predictor combines contributions from all n codes employed by the network, \({f}_{r}({\boldsymbol{x}})=\mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{\gamma=1}^{n}{P}_{\gamma }{a}_{\gamma }^{r}{\langle {\langle \phi [{z}^{L}({\boldsymbol{x}})]\rangle }_{{z}^{L}({\boldsymbol{x}})| {{\boldsymbol{z}}}^{L}}\rangle }_{{{\boldsymbol{z}}}^{L}| {{\boldsymbol{a}}}_{\gamma }}\) (see supplement B.2). Similarly, the feature layer kernel is composed of the contributions from all codes \({{\mathcal{K}}}_{L}({{\boldsymbol{x}}}_{1} , {{\boldsymbol{x}}}_{2})=\mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{\gamma=1}^{n}{P}_{\gamma }{\langle {\langle \phi [{z}^{L}({{\boldsymbol{x}}}_{1})]\phi [{z}^{L}({{\boldsymbol{x}}}_{2})]\rangle }_{{z}^{L}({{\boldsymbol{x}}}_{1}) , {z}^{L}({{\boldsymbol{x}}}_{2})| {{\boldsymbol{z}}}^{L}}\rangle }_{{{\boldsymbol{z}}}^{L}| {{\boldsymbol{a}}}_{\gamma }}\).

We apply the theory again to the classification of the first three digits in MNIST with a single-hidden-layer network. To make the theory tractable, we neglect the fluctuations of the preactivation conditioned on the readout weights. The test activations display a clear redundant coding scheme with small deviations on certain test inputs (Fig. 6a). In the test kernel, this leads to a clear block structure (Fig. 6b). The mean predictor is close to the test targets except on particularly difficult test inputs and accurately captured by the theory (Fig. 6c); the resulting generalization error is smaller than its counterpart based on the GP theory (Fig. 6d). Similar to linear networks, reduction of the generalization error is mainly driven by the reduced variance of the predictor although in this case also the non-lazy mean predictor performs slightly better.

Using randomly projected MNIST to enable sampling in the regime P > N0 leads to similar results—a redundant coding scheme on training inputs and good generalization (see supplement E). In contrast, using the first three classes of CIFAR10 instead of MNIST with P = 100 still leads to a redundant coding on the training inputs but the coding scheme is lost on test inputs, indicating that the representations do not generalize well, which is confirmed by a high generalization error (see supplement E). Increasing the data set size to all ten classes and the full training set with P = 50, 000 inputs and using a two-hidden-hidden layer network with N = 1 000 neurons improves the generalization to an overall accuracy of 0.45; in this case, the feature layer training activations show a redundant coding scheme on training inputs (Fig. 7b) which generalize to varying degree to test inputs (Fig. 7e).

a, b, d, e Activations of 100 randomly selected first (a, d) and second (b, e) layer neurons on 1000 randomly selected training (a, b) and test (d, e) inputs for a given weight sample. c Readout weights of all three classes for the 100 selected neurons. f Predictor for first class using the weighted sample used in the other panels (gray) and test target (black).

For ReLU networks the mean predictor comprises the contributions from the bulk and the outliers, \({f}_{r}({\boldsymbol{x}})={a}_{0}^{r}{\langle {\langle \phi [z({\boldsymbol{x}})]\rangle }_{z({\boldsymbol{x}})| {\boldsymbol{z}}}\rangle }_{{\boldsymbol{z}}| {{\boldsymbol{a}}}_{0}}+\mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{i=1}^{n}{\bar{a}}_{i}^{r}\phi ({\bar{z}}_{i}({\boldsymbol{x}}))\) with \({\bar{z}}_{i}({\boldsymbol{x}})={\bar{{\boldsymbol{z}}}}_{i}^{\top }{{\boldsymbol{K}}}_{0}^{+}{{\boldsymbol{k}}}_{0}({\boldsymbol{x}})\) for i = 1, …, n. As in the other cases, the predictor variance can be neglected. The test kernel is also composed of the contributions from the bulk and the outliers, \(K({{\boldsymbol{x}}}_{1} , {{\boldsymbol{x}}}_{2})={\langle {\langle \phi [z({{\boldsymbol{x}}}_{1})]\phi [z({{\boldsymbol{x}}}_{2})]\rangle }_{z({{\boldsymbol{x}}}_{1}) , z({{\boldsymbol{x}}}_{2})| {\boldsymbol{z}}}\rangle }_{{\boldsymbol{z}}| {{\boldsymbol{a}}}_{0}}+\mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{\gamma=1}^{n}\phi [{z}_{\gamma }({{\boldsymbol{x}}}_{1})]\phi [{z}_{\gamma }({{\boldsymbol{x}}}_{2})]\). Note that for the outliers, the product of two \(O(\sqrt{N})\) activations jointly overcomes the 1/N in the kernel, Eq. (2), similar to the predictor where the \(O(\sqrt{N})\) readout weights and the \(O(\sqrt{N})\) activations jointly overcome the non-lazy scaling.

On the first three digits of MNIST, the test activations exhibit three outliers which code for one class each (Fig. 6a), leading to a test kernel that displays a clear block structure due to the outliers (Fig. 6b). The mean predictor is accurately captured by a theory which only takes the outliers into account (Fig. 6c). In terms of the generalization error, the non-lazy network outperforms the GP predictor (Fig. 6d), again mainly due to the reduction of the predictor variance.

Discussion

We developed a theory for the weight posterior of non-lazy networks in the limit of infinite width and data set size, from which we derived analytical expressions for the single neuron posteriors of the readout weights and the preactivation on training and test inputs. These single neuron posteriors revealed that the learned representations are embedded into the network using distinct coding schemes. Furthermore, we used the single neuron posteriors to derive the mean predictor and the mean kernels on training and test inputs. We applied the theory to two classification tasks: A simple toy model using orthogonal data and random labels to highlight the coding schemes and image classification using MNIST and CIFAR10 to investigate generalization. In both cases, the theoretical results are in excellent agreement with empirical samples from the weight posterior.

Coding schemes

We show that the embedding of learned representations by the neurons exhibits a remarkable structure: A coding scheme where distinct populations of neurons are characterized by the subset of classes that activate them. The details of the coding scheme depend strongly on the nonlinearity (Fig. 2): Linear networks display an analog coding scheme where all neurons code for all classes in a graded manner, sigmoidal networks display a redundant coding scheme where large populations of neurons are active on specific combinations of classes, and ReLU networks display a sparse coding scheme in which a few individual neurons are active on specific classes while the remaining neurons are task agnostic. In networks with multiple hidden layers, the coding scheme appears in all layers but is sharpened across layers; the coding scheme in the last layer remains the same as in the single-layer case (Fig. 3).

We have shown that the analog coding scheme is a unique feature of linear networks, that a redundant coding scheme emerges for sigmoidal nonlinearities, and that the sparse coding scheme appears for rectified activation functions. The sparse coding scheme does not appear to be the result of the non-smoothness or the homogeneity of the ReLU nonlinearity. In fact, this scheme also arises for \(\phi (z)=\log (1+{e}^{z})\) and \(\phi (z)=\max (0 , {z}^{2})\) (see supplement E).

Sparse representations have classically been associated with rectified nonlinearities in combination with L1 regularization in both neuroscience46,47 and machine learning48. Moreover, it was recently shown that input noise can induce sparse representations in ReLU networks without L1 regularization49. In our case, the sparse representations emerge with L2 instead of L1 regularization on the weights and without input noise.

The fact that L2 regularization is frequently employed in practice raises the question: Why were the coding schemes not previously observed? Compared to standard training protocols, there are two main differences: (1) The sampling from the posterior, i.e., training for a long time with added noise, and (2) the data set size-dependent strength of the readout weight variance, which corresponds to a data set size dependent regularization using weight decay. Empirically, we see that a clear redundant coding scheme emerges also in the absence of noise and data set size-dependent regularization on the toy task (see supplement E), indicating the the coding scheme characterizes the minimum norm solution. However, in general, we expect that the minimum norm solution is separated from the initialization by barriers such that noise is necessary to overcome these barriers. Adding noise, in turn, requires the stronger regularization implemented through the scaled readout weight variance (see supplement E). Furthermore, we note that the final coding schemes only emerge after orders of magnitude more training steps (see supplement E).

From a theoretical perspective, we hypothesize that the coding schemes were elusive because they are not captured by the kernel, which is a frequently used observable in theoretical studies26,38,39,40,41. Furthermore, the coding schemes are controlled by the distribution of the readout weights, which have been marginalized in previous work18,25,26,41,50. Here, we established the readout weights themselves as crucial order parameters controlling the properties of the learned representations.

Permutation symmetry breaking

The coding schemes determine the structure of a typical solution sampled from the weight posterior, e.g., for sigmoidal networks, a solution with a redundant coding scheme. Due to the neuron permutation symmetry of the posterior, each typical solution has permuted counterparts which are also typical solutions. Permutation symmetry breaking occurs if these permuted solutions are disconnected in solution space, i.e., if the posterior contains high barriers between the permuted solutions.

In sigmoidal and ReLU networks, permutation symmetry is broken. The theoretical signature of this symmetry breaking is the disconnected structure of the posterior of the readout weights, where the different branches are separated by high barriers. Numerically, symmetry breaking is evidenced by the fact that, at equilibrium, neurons do not change their coding identity with sampling time. We note that for the readout weights, the symmetry broken phase is also a frozen state, namely not only the coding structure is fixed, but also there are no fluctuations in the magnitude of each weight (Fig. 2). In contrast, activations in the hidden layer, which are also constant in their coding, do exhibit residual temporal fluctuations around a pronounced mean which carries the task-relevant information.

Interestingly, the situation is more involved in networks with two hidden layers (Fig. 4). In the first layer, permutation symmetry is broken, and the neurons’ code is frozen in ReLU networks but not in sigmoidal networks. In the latter case, the typical solution has a prominent coding scheme, but individual neurons switch their code during sampling.

Symmetry breaking has been frequently discussed in the context of learning in artificial neural networks, for example, replica symmetry breaking in perceptrons with binary weights51,52,53, permutation symmetry breaking in fully connected networks54,55 and restricted Boltzmann machines56, or continuous symmetry breaking of the “kinetic energy” (reflecting the learning rule)57,58. Furthermore, the breaking of parity symmetry has been linked to feature learning50, albeit in a different scaling limit. The role of an intact (not broken) permutation symmetry has been explored in the context of the connectedness of the loss landscape59,60,61. Here, we establish a direct link between symmetry breaking and the nature of the neural representations.

Limitations of the theory

For our theory, we assume that the network width N and the data set size P are large, formally captured by the limit N, P → ∞. Both limits are necessary for the coding schemes to emerge. Surprisingly, the limits are not coupled in the theory, i.e., we do not need to assume a fixed ratio α = P/N. Correspondingly, we observe a redundant coding scheme for a N = 1000 sigmoidal network using the full CIFAR10 training set with P = 50, 000. Still, we expect that our theory ceases to hold close to the network’s capacity, i.e., when P = O(N2).

A second important assumption is that we work in the zero temperature limit where the posterior is restricted to the solution space. Which aspects of the theory hold at higher temperatures is an important open question. Empirically, we observe a critical temperature above which there is no longer a redundant coding scheme for sigmoidal network (see supplement E).

Our theory is valid only if the number of hidden layers and the number of outputs is small. The extension to deeper networks, in particular networks with residual connections, or to networks with a large number of outputs, as necessary, for example, for ImageNet, are interesting questions for future research.

Neural collapse

The redundant coding scheme in sigmoidal networks and the sparse coding scheme in ReLU networks are closely related to the phenomenon of neural collapse62. The two main properties of collapse are (1) vanishing variability across inputs from the same class of the last layer activations and (2) last layer activations forming an equiangular tight frame (centered class means are equidistant and equiangular with maximum angle). There are two additional properties which, however, follow from the first two under minimal assumptions62. We note that collapse is determined only by training data in the original definition.

Formally, the first property of collapse is violated in the non-lazy networks investigated here due to the non-vanishing across-neuron variability of the activations given the readout weights. However, the mean activations conditional on the readout weights, which carry the task-relevant information, generate an equiangular tight frame in both sigmoidal and ReLU networks. This creates an interesting link to empirically trained networks where neural collapse has been shown to occur under a wide range of conditions62,63.

Neglecting the non-vanishing variability, the main difference between neural collapse and the coding schemes is that the latter imposes a more specific structure. Technically, the equiangular tight frame characterizing neural collapse is invariant under orthogonal transformations, while the coding schemes are invariant under permutations, which is a subset of the orthogonal transformations. This additional structure makes the representations highly interpretable in terms of a neural code—conversely, applying, e.g., a rotation in neuron space to the redundant or sparse coding scheme would hide the immediately apparent structure of the solution.

Representation learning and generalization

The case of non-lazy linear networks makes an interesting point about the interplay between feature learning and generalization: Although the networks learn strong, task-dependent representations, the mean predictor is identical to the Gaussian Process limit where the features are random. The only difference between non-lazy networks and random features is a reduction in the predictor variance. Thus, this provides an explicit example where feature learning only mildly helps generalization through the reduction of the predictor variance.

More generally, in all examples, the improved performance of non-lazy networks (Fig. 6) is mainly driven by the reduction of the predictor variance; the mean predictor does not generalize significantly better than a predictor based on random features. This shows an important limitation of our work: In order to achieve good generalization performance, it might be necessary to consider deeper nonlinear architectures or additional structures in the model. This is in line with recent empirical results which try to push multi-layer perceptrons to better performance64.

While the learned representations might not necessarily help generalization on the trained task, they can still be useful for few-shot learning of a novel task65,66,67,68. Indeed, neural collapse has been shown to be helpful for transfer learning if neural collapse still holds (approximately) on inputs from the novel classes69. Due to the relation between coding schemes and neural collapse, this suggests that the learned representations investigated here are useful for downstream tasks—if the nature of the solution does not change on the new inputs. This remains to be systematically explored.

Lazy vs. non-lazy regime

The definition of a lazy vs. non-lazy regime is subtle. Originally, the lazy regime was defined by the requirement that the learned changes in the weights affect the final output only linearly70. This implies that the learned changes in the representations are weak since changes in the hidden layer weights nonlinearly affect the final output. To overcome the weak representation learning, the non-lazy regime was defined as O(1) changes of the features during the first steps of gradient descent38,39. This definition leads to an initialization where the readout scales its inputs with 1/N39. However, the scaling might change during training—which is not captured by a definition at initialization.

We here define the non-lazy regime such that the readout scales its inputs with 1/N after learning, i.e., under the posterior. Importantly, we prevent the readout weights overcome the scaling by growing their norm, which leads to the requirement of a decreasing prior variance of the readout weights with increasing P. The definition implies that strong representations are learned: The readout weights must be aligned with the last layer’s features on all training inputs, which is not the case for random features.

Methods

Weight posterior

The weight posterior is20

where \(Z=\int\,d{P}_{0}(\Theta )\,\exp [-\beta {\mathcal{L}}(\Theta )]\) is the partition function, \({\mathcal{L}}(\Theta )=\frac{1}{2}\mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{r=1}^{m}\mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{\mu=1}^{P}{[{y}_{\mu }^{r}-{f}_{r}({{\boldsymbol{x}}}_{\mu };\Theta )]}^{2}\) a mean-squared error loss, and P0(Θ) an i.i.d. zero-mean Gaussian prior with prior variances \({\sigma }_{a}^{2}\), \({\sigma }_{\ell }^{2}\) for readout and hidden weights, respectively. Temperature T = 1/β controls the relative importance of the quadratic loss and the prior. In the overparameterized regime, the limit T → 0 restricts the posterior to the solution space where the network interpolates the training data. For simplicity, we set σℓ = 1 in the main text. Throughout, we denote expectations w.r.t. the weight posterior by 〈⋅〉Θ.

The interplay between loss and prior shapes the solutions found by the networks. Importantly, on the solution space the prior alone determines the posterior probability. Thus, the prior plays a central role for regularization which complements the implicit regularization due to the non-lazy scaling. The Gaussian prior used here can be interpreted as an L2 regularization of the weights.

Samples from the posterior can be obtained using Langevin dynamics \(\frac{d}{dt}\Theta=-\nabla {\mathcal{L}}(\Theta )+T\nabla \log {P}_{0}(\Theta )+\sqrt{2T}\xi (t)\) where ξ(t) are independent Gaussian white noise processes. These dynamics first approach the solution space on a timescale of O(1) and subsequently diffuse on the solution space on a much slower time scale of O(T−1)71; after equilibration the dynamics provide samples from the posterior.

Scaling limit

We consider the limit N, N0, P → ∞ while the number of readout units as well as the number of layers remain finite, i.e., m, L = O(1). Because the gradient of \({\mathcal{L}}(\Theta )\) is small due to the non-lazy scaling of the readout, the noise introduced by the temperature needs to be scaled down as well, requiring the scaling T → T/N. In all other parts of the manuscript T denotes the rescaled temperature which therefore remains of O(1) as N increases. In the present work, we focus on the regime where the training loss is essentially zero, and therefore consider the limit T → 0 for the theory; to generate empirical samples from the weight posterior we use a small but non-vanishing rescaled temperature.

Under the posterior, the non-lazy scaling leads to large readout weights: The posterior norm per neuron grows with P, thereby compensating for the non-lazy scaling. To avoid this undoing of the non-lazy scaling, we scale down \({\sigma }_{a}^{2}\) with P, guaranteeing that the posterior norm of the readout weights per neuron is O(1). The precise scaling depends on the depth and the type of nonlinearity.

In total there are three differences between (4) and the corresponding posterior in the lazy regime20: (1) The non-lazy scaling of the readout in (1) with 1/N instead of \(1/\sqrt{N}\). (2) The scaling of the temperature with 1/N. (3) The prior variance of the readout weights \({\sigma }_{a}^{2}\) needs to be scaled down with P.

Parameters used in Figures

Figure 1 : single-hidden-layer networks L = 1 with a single output m = 1 and N = P = 500, N0 = 510. For the task the classes are assigned with probability 1/2, the targets are binary y = ±1 according to the class.

Figures 2, 4: single-hidden-layer networks L = 1 with m = 3 outputs. Parameters for linear, sigmoidal, and ReLU networks, respectively: N = P = 200, N0 = 220, classes assigned with fixed ratios [1/2, 1/4, 1/4], targets y+ = 1 and y− = 0; N = P = 500, N0 = 520, classes assigned with fixed ratios [1/2, 1/4, 1/4], targets y+ = 1 and y− = 1/2; N = P = 500, N0 = 520, classes assigned with fixed ratios [1/2, 1/4, 1/4], targets y+ = 1 and y− = −1/2.

Figure 3 : three-hidden-layer networks L = 3 with m = 3 outputs. Parameters for linear, sigmoidal, and ReLU networks, respectively: N = P = 200, N0 = 220, classes assigned with fixed ratios [1/2, 1/4, 1/4], targets y+ = 1 and y− = − 1/2; N = P = 200, N0 = 220, classes assigned with fixed ratios [1/2, 1/4, 1/4], targets y+ = 1 and y− = − 1/2; N = P = 100, N0 = 120, classes assigned with fixed ratios [1/2, 1/4, 1/4], targets y+ = 1 and y− = −1/2.

Figure 5 : two-hidden-layer sigmoidal networks L = 2 with m = 3 outputs. Parameters: N = P = 500, N0 = 520, classes assigned with fixed ratios [1/2, 1/4, 1/4], targets y+ = 1 and y− = 1/2.

Figure 6 : single-hidden-layer networks L = 1 with m = 3 outputs. Parameters: N = P = 100, N0 = 784, classes 0, 1, 2 assigned randomly with probability 1/3, targets y+ = 1 and y− = −1/2.

Figure 7 : two-hidden-layer sigmoidal networks L = 2 with m = 10 outputs. Parameters: N = 1000, P = 50,000, N0 = 3072, targets y+ = 1 and y− = −1/10.

Data availability

The sampled weights are available on figshare with the identifier https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.26539129.

Code availability

The code is available on figshare with the identifier https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.26539129.

References

Bengio, Y., Courville, A. & Vincent, P. Representation learning: a review and new perspectives. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 35, 1798–1828 (2013).

LeCun, Y., Bengio, Y. & Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 521, 436 (2015).

Goodfellow, I., Bengio, Y. & Courville, A. Deep Learning (MIT Press, 2016).

Zhang, C., Bengio, S., Hardt, M., Recht, B. & Vinyals, O. Understanding deep learning requires rethinking generalization, in https://openreview.net/forum?id=Sy8gdB9xx. International Conference on Learning Representations (Curran Associates, Inc., 2017).

Zhang, C., Bengio, S., Hardt, M., Recht, B. & Vinyals, O. Understanding deep learning (still) requires rethinking generalization. Commun. ACM 64, 107–115 (2021).

Belkin, M., Hsu, D., Ma, S. & Mandal, S. Reconciling modern machine-learning practice and the classical bias-variance trade-off. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 116, 15849 (2019).

Nakkiran, P. et al. Deep double descent: Where bigger models and more data hurt, in https://openreview.net/forum?id=B1g5sA4twr. International Conference on Learning Representations (Curran Associates, Inc., 2020).

Belkin, M. Fit without fear: remarkable mathematical phenomena of deep learning through the prism of interpolation. Acta Numerica 30, 203–248 (2021).

Shwartz-Ziv, R. et al. Just how flexible are neural networks in practice? https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.11463 (2024).

MacKay, D. J. Information Theory, Inference and Learning Algorithms (Cambridge University Press, 2003)

Bahri, Y. et al. Statistical mechanics of deep learning. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 11, 501 (2020).

Neal, R. M., https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4612-0745-0. Bayesian Learning for Neural Networks (Springer New York, 1996).

Williams, C. Computing with infinite networks, in https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper/1996/file/ae5e3ce40e0404a45ecacaaf05e5f735-Paper.pdf. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Vol. 9 (eds Mozer, M., Jordan, M., & Petsche, T.) (MIT Press, 1996).

Lee, J. et al. Deep neural networks as gaussian processes, in https://openreview.net/forum?id=B1EA-M-0Z. International Conference on Learning Representations (Curran Associates, Inc., 2018).

Matthews, A. G. D. G., Hron, J., Rowland, M., Turner, R. E. & Ghahramani, Z. Gaussian process behaviour in wide deep neural networks, in https://openreview.net/forum?id=H1-nGgWC-. International Conference on Learning Representations (Curran Associates, Inc., 2018).

Yang, G. Wide feedforward or recurrent neural networks of any architecture are gaussian processes, in Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Vol. 32 (eds Wallach, H., Larochelle, H., Beygelzimer, A., d’Alché-Buc, F., Fox, E., & Garnett, R.) (Curran Associates, Inc., 2019).

Naveh, G., Ben David, O., Sompolinsky, H. & Ringel, Z. Predicting the outputs of finite deep neural networks trained with noisy gradients. Phys. Rev. E 104, 064301 (2021).

Segadlo, K. et al. Unified field theoretical approach to deep and recurrent neuronal networks. J. Stat. Mech. Theory Exp. 2022, 103401 (2022).

Hron, J., Novak, R., Pennington, J. & Sohl-Dickstein, J. Wide Bayesian neural networks have a simple weight posterior: theory and accelerated sampling. in: Proceedings of the 39th International Conference on Machine Learning, Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, Vol. 162 (eds Chaudhuri, K., Jegelka, S., Song, L., Szepesvari, C., Niu, G., & Sabato, S.) 8926–8945 (PMLR, 2022).

Li, Q. & Sompolinsky, H. Statistical mechanics of deep linear neural networks: the backpropagating kernel renormalization. Phys. Rev. X 11, 031059 (2021).

Naveh, G. & Ringel, Z. A self consistent theory of gaussian processes captures feature learning effects in finite CNNs, in https://openreview.net/forum?id=vBYwwBxVcsE. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Vol. 34 (eds Ranzato, M., Beygelzimer, A., Dauphin, Y., Liang, P., & Vaughan, J. W.) (Curran Associates, Inc., 2021).

Zavatone-Veth, J. A., Tong, W. L. & Pehlevan, C. Contrasting random and learned features in deep bayesian linear regression. Phys. Rev. E 105, 064118 (2022).

Cui, H., Krzakala, F. & Zdeborova, L. Bayes-optimal learning of deep random networks of extensive-width, in https://proceedings.mlr.press/v202/cui23b.html. Proceedings of the 40th International Conference on Machine Learning, Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, Vol. 202 (eds Krause, A., Brunskill, E., Cho, K., Engelhardt, B., Sabato, S., & Scarlett, J.) 6468–6521 (PMLR, 2023).

Hanin, B. & Zlokapa, A. Bayesian interpolation with deep linear networks. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 120, e2301345120 (2023).

Pacelli, R. et al. A statistical mechanics framework for bayesian deep neural networks beyond the infinite-width limit. Nat. Mach. Intell. 5, 1497–1507 (2023).

Fischer, K. et al. Critical feature learning in deep neural networks, in https://proceedings.mlr.press/v235/fischer24a.html. Proceedings of the 41st International Conference on Machine Learning, Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, Vol. 235 (eds Salakhutdinov, R. et al.) 13660–13690 (PMLR, 2024).

Chizat, L., Oyallon, E. & Bach, F. On lazy training in differentiable programming, in https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper_files/paper/2019/file/ae614c557843b1df326cb29c57225459-Paper.pdf. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Vol. 32 (eds Wallach, H., Larochelle, H., Beygelzimer, A., d’ Alché-Buc, F., Fox, E., & Garnett, R.) (Curran Associates, Inc., 2019).

Woodworth, B. et al. Kernel and rich regimes in overparametrized models, in https://proceedings.mlr.press/v125/woodworth20a.html. Proceedings of Thirty Third Conference on Learning Theory, Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, Vol. 125 (eds Abernethy, J. & Agarwal, S.) 3635–3673 (PMLR, 2020).

Geiger, M., Spigler, S., Jacot, A. & Wyart, M. Disentangling feature and lazy training in deep neural networks. J. Stat. Mech.: Theory Exp. 2020, 113301 (2020).

Yaida, S. Non-Gaussian processes and neural networks at finite widths., in https://proceedings.mlr.press/v107/yaida20a.html. Proceedings of The First Mathematical and Scientific Machine Learning Conference, Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, Vol. 107 (eds Lu, J. & Ward, R.) 165–192 (PMLR, 2020).

Dyer, E. & Gur-Ari, G. Asymptotics of wide networks from feynman diagrams, in https://openreview.net/forum?id=S1gFvANKDS. International Conference on Learning Representations (Curran Associates, Inc., 2020).

Zavatone-Veth, J. A., Canatar, A., Ruben, B. & Pehlevan, C. Asymptotics of representation learning in finite bayesian neural networks, in https://openreview.net/forum?id=1oRFmD0Fl-5. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Vol. 34 (eds Ranzato, M., Beygelzimer, A., Dauphin, Y., Liang, P., & Vaughan, J. W.) (Curran Associates, Inc., 2021).

Roberts, D. A., Yaida, S. & Hanin, B. The Principles of Deep Learning Theory (Cambridge University Press, 2022).

Mei, S., Montanari, A. & Nguyen, P.-M. A mean field view of the landscape of two-layer neural networks. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 115, E7665 (2018).

Chizat, L. & Bach, F. On the global convergence of gradient descent for over-parameterized models using optimal transport, in https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper_files/paper/2018/file/a1afc58c6ca9540d057299ec3016d726-Paper.pdf. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Vol. 31 (eds Bengio, S., Wallach, H., Larochelle, H., Grauman, K., Cesa-Bianchi, N., & Garnett, R. (Curran Associates, Inc., 2018).

Rotskoff, G. & Vanden-Eijnden, E. Parameters as interacting particles: long time convergence and asymptotic error scaling of neural networks, in https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper_files/paper/2018/file/196f5641aa9dc87067da4ff90fd81e7b-Paper.pdf. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Vol. 31 (eds Bengio, S., Wallach, H., Larochelle, H., Grauman, K., Cesa-Bianchi, N., & Garnett, R. (Curran Associates, Inc., 2018).

Sirignano, J. & Spiliopoulos, K. Mean field analysis of neural networks: a central limit theorem. Stoch. Process. Appl. 130, 1820 (2020).

Yang, G. & Hu, E. J. Tensor programs IV: Feature learning in infinite-width neural networks, in https://proceedings.mlr.press/v139/yang21c.html. Proceedings of the 38th International Conference on Machine Learning, Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, Vol. 139 (eds Meila, M. & Zhang, T.) 11727–11737 (PMLR, 2021).

Bordelon, B. & Pehlevan, C. Self-consistent dynamical field theory of kernel evolution in wide neural networks, in https://openreview.net/forum?id=sipwrPCrIS. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Vol. 35 (eds Koyejo, S. et al.) (Curran Associates, Inc., 2022).

Bordelon, B. & Pehlevan, C. Dynamics of finite width kernel and prediction fluctuations in mean field neural networks, in https://openreview.net/forum?id=fKwG6grp8o. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Vol. 36 (eds Oh, A. H. et al.) (Curran Associates, Inc., 2023).

Seroussi, I., Naveh, G. & Ringel, Z. Separation of scales and a thermodynamic description of feature learning in some cnns, Nat. Commun. 14, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-36361-y (2023).

Cortes, C., Mohri, M. & Rostamizadeh, A. Algorithms for learning kernels based on centered alignment. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 13, 795 (2012).

Kornblith, S., Norouzi, M., Lee, H. & Hinton, G. Similarity of neural network representations revisited, in https://proceedings.mlr.press/v97/kornblith19a.html. Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Machine Learning, Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, Vol. 97 (eds Chaudhuri, K. & Salakhutdinov, R.). 3519–3529 (PMLR, 2019).

LeCun, Y. The mnist database of handwritten digits, http://yann.lecun.com/exdb/mnist/ (1998).

Alex, K. Learning multiple layers of features from tiny images, https://www.cs.toronto.edu/~kriz/learning-features-2009-TR.pdf (2009).

Olshausen, B. A. & Field, D. J. Sparse coding with an overcomplete basis set: a strategy employed by v1? Vis. Res. 37, 3311 (1997).

Olshausen, B. A. & Field, D. J. Sparse coding of sensory inputs. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 14, 481 (2004).

Glorot, X., Bordes, A. & Bengio, Y. Deep sparse rectifier neural networks, in https://proceedings.mlr.press/v15/glorot11a.html. Proceedings of the Fourteenth International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics, Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, Vol. 15 (eds Gordon, G., Dunson, D., & Dudík, M.) 315–323 (PMLR, 2011).

Bricken, T., Schaeffer, R., Olshausen, B. & Kreiman, G. Emergence of sparse representations from noise, in https://proceedings.mlr.press/v202/bricken23a.html. Proceedings of the 40th International Conference on Machine Learning, Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, Vol. 202 (eds Krause, A., Brunskill, E., Cho, K., Engelhardt, B., Sabato, S., & Scarlett, J.) 3148–3191 (PMLR, 2023).

Rubin, N., Seroussi, I. & Ringel, Z. Grokking as a first order phase transition in two layer networks, in https://openreview.net/forum?id=3ROGsTX3IR. The Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations (Curran Associates, Inc., 2024).

Krauth, W. & Mézard, M. Storage capacity of memory networks with binary couplings. J. de. Phys. 50, 3057–3066 (1989).

Seung, H. S., Sompolinsky, H. & Tishby, N. Statistical mechanics of learning from examples. Phys. Rev. A 45, 6056 (1992).

Watkin, T. L. H., Rau, A. & Biehl, M. The statistical mechanics of learning a rule. Rev. Mod. Phys. 65, 499 (1993).

Barkai, E., Hansel, D. & Sompolinsky, H. Broken symmetries in multilayered perceptrons. Phys. Rev. A 45, 4146 (1992).

Engel, A., Köhler, H. M., Tschepke, F., Vollmayr, H. & Zippelius, A. Storage capacity and learning algorithms for two-layer neural networks. Phys. Rev. A 45, 7590 (1992).

Hou, T., Wong, K. Y. M. & Huang, H. Minimal model of permutation symmetry in unsupervised learning. J. Phys. A: Math. Theor. 52, 414001 (2019).

Kunin, D., Sagastuy-Brena, J., Ganguli, S., Yamins, D. L. & Tanaka, H. Neural mechanics: Symmetry and broken conservation laws in deep learning dynamics, in https://openreview.net/forum?id=q8qLAbQBupm. International Conference on Learning Representations (Curran Associates, Inc., 2021).

Tanaka, H. & Kunin, D. Noether’s learning dynamics: Role of symmetry breaking in neural networks, in https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper_files/paper/2021/file/d76d8deea9c19cc9aaf2237d2bf2f785-Paper.pdf. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Vol. 34 (eds Ranzato, M., Beygelzimer, A., Dauphin, Y., Liang, P., & Vaughan, J. W.) 25646–25660 (Curran Associates, Inc., 2021).

Brea, J., Simsek, B., Illing, B. & Gerstner, W. Weight-space symmetry in deep networks gives rise to permutation saddles, connected by equal-loss valleys across the loss landscape. https://arxiv.org/abs/1907.02911 (2019).

Simsek, B. et al. Geometry of the loss landscape in overparameterized neural networks: Symmetries and invariances, in https://proceedings.mlr.press/v139/simsek21a.html. Proceedings of the 38th International Conference on Machine Learning, Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, Vol. 139. 9722–9732 (eds Meila, M. and Zhang, T.) (PMLR, 2021).

Entezari, R., Sedghi, H., Saukh, O. & Neyshabur, B. The role of permutation invariance in linear mode connectivity of neural networks, in https://openreview.net/forum?id=dNigytemkL. International Conference on Learning Representations (Curran Associates, Inc., 2022).

Papyan, V., Han, X. Y. & Donoho, D. L. Prevalence of neural collapse during the terminal phase of deep learning training. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 117, 24652 (2020).

Han, X., Papyan, V. & Donoho, D. L. Neural collapse under MSE loss: Proximity to and dynamics on the central path, in https://openreview.net/forum?id=w1UbdvWH_R3. International Conference on Learning Representations (Curran Associates, Inc., 2022).

Bachmann, G., Anagnostidis, S. & Hofmann, T. Scaling mlps: A tale of inductive bias, in https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper_files/paper/2023/file/bf2a5ce85aea9ff40d9bf8b2c2561cae-Paper-Conference.pdf. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Vol. 36 (eds Oh, A., Naumann, T., Globerson, A., Saenko, K., Hardt, M., & Levine, S.) 60821–60840 (Curran Associates, Inc., 2023).

Fei-Fei, L., Fergus, R. & Perona, P. One-shot learning of object categories. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 28, 594 (2006).

Vinyals, O., Blundell, C., Lillicrap, T., Kavukcuoglu, K. & Wierstra, D. Matching networks for one shot learning, in https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper_files/paper/2016/file/90e1357833654983612fb05e3ec9148c-Paper.pdf. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Vol. 29 (eds Lee, D., Sugiyama, M., Luxburg, U., Guyon, I., & Garnett, R.) (Curran Associates, Inc., 2016).

Snell, J., Swersky, K. & Zemel, R. Prototypical networks for few-shot learning, in https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper_files/paper/2017/file/cb8da6767461f2812ae4290eac7cbc42-Paper.pdf. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Vol. 30 (eds Guyon, I., Luxburg, U. V., Bengio, S., Wallach, H., Fergus, R., Vishwanathan, S., & Garnett, R.) (Curran Associates, Inc., 2017).

Sorscher, B., Ganguli, S. & Sompolinsky, H. Neural representational geometry underlies few-shot concept learning. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 119, e2200800119 (2022).

Galanti, T., György, A. & Hutter, M. On the role of neural collapse in transfer learning, in https://openreview.net/forum?id=SwIp410B6aQ. International Conference on Learning Representations (Curran Associates, Inc., 2022).

Jacot, A., Gabriel, F. & Hongler, C. Neural tangent kernel: Convergence and generalization in neural networks, in https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper_files/paper/2018/file/5a4be1fa34e62bb8a6ec6b91d2462f5a-Paper.pdf. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Vol. 31 (eds Bengio, S. et al.) (Curran Associates, Inc., 2018).

Avidan, Y., Li, Q. & Sompolinsky, H. Connecting ntk and nngp: a unified theoretical framework for neural network learning dynamics in the kernel regime. https://arxiv.org/abs/2309.04522 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Qianyi Li for many helpful discussions and Lorenzo Tiberi, Chester Mantel, Kazuki Irie, and Haozhe Shan for their feedback on the manuscript. This research was supported by the Swartz Foundation, the Gatsby Charitable Foundation, the Kempner Institute for the Study of Natural and Artificial Intelligence, and Office of Naval Research (ONR) grant No. N0014-23-1-2051, and in part by grant NSF PHY-1748958 to the Kavli Institute for Theoretical Physics (KITP). The computations in this paper were run on the FASRC Cannon cluster supported by the FAS Division of Science Research Computing Group at Harvard University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.v.M. and H.S. contributed to the development of the project. A.v.M. and H.S. developed the theory. A.v.M. performed simulations. A.v.M. and H.S. participated in the analysis and interpretation of the data. A.v.M. and H.S. wrote the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Friedrich Schuessler and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

van Meegen, A., Sompolinsky, H. Coding schemes in neural networks learning classification tasks. Nat Commun 16, 3354 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-58276-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-58276-6