Abstract

Renewable biomass serves as a cost-effective source of carbon matrix to carry single-atom catalysts (SACs). However, the natural abundant oxygen in these materials hinders the sufficient dispersion of element with high oxygen affinity such iron (Fe). The lowered-density and oxidized SACs greatly limits their catalytic applications. Here we develop a facile continuous activation (CA) approach for synthesizing robust biomass-derived Fe-SACs. Comparing to the traditional pyrolysis method, the CA approach significantly increases the Fe loading density from 1.13 atoms nm−2 to 4.70 atoms nm−2. Simultaneously, the CA approach induces a distinct coordination tuning from dominated Fe-O to Fe-N moieties. We observe a pH-universal oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) performance over the CA-derived Fe-SACs with a half-wave potential of 0.93 V and 0.78 V vs. RHE in alkaline and acidic electrolyte, respectively. Density functional theory calculations further reveal that the increased Fe-N coordination effectively reduces the energy barriers for the ORR, thus enhancing the catalytic activity. The Fe-SACs-based zinc-air batteries show a specific capacity of 792 mA·h·gZn−1 and ultra-long life span of over 650 h at 5 mA cm−2.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Single-atom catalysts (SACs) supported on carbon substrates with metal-nitrogen-carbon coordination (M-N-C) have attracted growing attention for their high potential to substitute the costly and labile platinum-based materials in catalyzing energy-related chemical reactions such as oxygen reduction reaction (ORR)1,2,3,4,5. With maximum atomic efficiency, developing robust SACs demands for a high metal loading and precisely tuned coordination structures6,7. To this end, various strategies have been proposed. For example, the templated pyrolysis strategy is widely adopted where well-designed metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) or C, N-rich molecules (e.g., melamine and dicyandiamide) serves as precursor for carbon substrate8,9,10. Usually, the delicate design and synthesis of MOF structures are time-consuming processes and it requires a huge amount of C, N-rich molecules to obtain the carbon frameworks as a majority of these organics are volatilized during pyrolysis11,12. These methods actually lead to an excessive waste of fine chemicals and result in low yields for SACs production.

A more sustainable and efficient alternative for SACs synthesis lies in the use of biomass (e.g., lignin and cellulose) as substrate precursor, which are readily available and abundant, naturally rich in C and N, and derives high porous structures after pyrolysis13,14. Despite these advantages, there are limited works regarding biomass-derived SACs15,16. The major obstacle inhibiting the extension of this strategy lies in the oxygen content in the biomass materials17,18,19. As reported previously, the single-atom sites are formed in a successive sintering and redispersion way during the pyrolysis20,21. The oxygen groups on the carbon substrate surface tend to grapple the oxyphilic iron or nickel nanoparticles/clusters, hindering the subsequent dispersion22,23. Moreover, except for the delicately designed axial O coordination, single-atom sites with planar O coordination are reported to degrade the ORR activity and suffered from stability issue24,25,26. The oxygen coordination also steers the reaction pathway from a four-electron one to a two-electron one27,28. Unfortunately, there still lacks effective strategies to selective eliminate the oxygen content in the biomass materials and fabricate SACs with high densities and dominated Fe-N coordination.

To address the abovementioned problems, we developed a facile continuous activation (CA) approach for synthesizing robust biomass-derived Fe-SACs (Fig. 1). We first loaded Fe(bpy)3Cl2 (bpy = 2,2’-bipyridine) on bacterial cellulose via a freeze-drying process. Afterwards, directly pyrolyzing the loaded precursors in an Ar atmosphere derives Fe-SACs with abundant oxygen contents and a low atom density. To avoid that, we provide a continuous C-N based small molecules/radicals source at the upstream of the loaded precursors by melamine decomposition. The C-N based small molecules/radicals flows through the loaded precursors and etched the surface oxygen groups away, liberating the dispersion of single atoms from the oxophilicity. The etching process also induced more vacancies for the anchoring of single atoms. Surprisingly, the CA approach increased the Fe loading density to a high 4.70 atoms nm−2, which is 4.15 times higher than the direct pyrolysis way (1.13 atoms nm−2). Simultaneously, the CA approach induced a distinct coordination tuning from dominated Fe-O to Fe-N moieties. In ORR tests, we observed an excellent pH-universal ORR performance over the CA-derived Fe SACs with a half-wave potential of 0.93 V vs. RHE and 0.78 V vs. RHE in alkaline and acidic electrolyte, respectively. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations further revealed that the increased Fe-N coordination effectively changes the potential determining step and reduced the energy barriers for ORR, thus enhancing the catalytic activity. The Fe SACs-based zinc-air batteries (ZABs) show a superior specific capacity of 792 mA h gZn−1 and ultralong life span of over 650 h at 5 mA cm−2, outperforming most reported ZABs.

Results

Synthesis and characterizations of the biomass-derived Fe SACs

In a typical synthetic process, the catalyst denoted as CA-Fe@BC was prepared via CA approach under 950 °C for 3 h, adopting 10 g melamine as CA agent and a distance of 23 cm from CA agent to loaded precursor (Supplementary Fig. S1–S2). More experimental details regarding temperature, distance, and amount control are provided in Supplementary. For comparison, the catalyst denoted as Fe@BC was prepared via generally adopted pyrolysis approach under identical conditions but without the CA agent. Hereafter, the carbon pyrolyzed from bacterial cellulose was named BC.

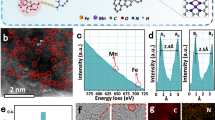

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images revealed that the CA-Fe@BC catalyst exhibits an intertwining structure of hollow fibers (Supplementary Fig. S3a–c). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images depict the carbon nanotubes with ultrathin wall thickness and encapsulated Fe-based nanoparticles (Supplementary Fig. S4a–c). In contrast, the SEM images of Fe@BC indicate that the inherited fibers are solid (Supplementary Fig. S3d–f), which was further verified by TEM characterizations (Supplementary Fig. S4d–f). Of note, the Fe@BC catalyst exhibited denser carbon matrix and larger nanoparticles than CA-Fe@BC (Supplementary Figs. S4 and S5). Closer inspection on the CA-Fe@BC manifests that the encapsulated spherical Fe-based nanoparticles are measured with interlayer spacing of approximately 1.94 Å and 1.71 Å corresponding to the (111) and (200) crystallographic planes of FeN0.032429, respectively (Fig. 2a–c). The surrounded shells display a interlayer spacing in the range of 3.34 Å, which belongs to (002) plane of graphitized carbon. The lattice spacing of the nanoparticles in Fe@BC were measured of 2.08 Å and 2.49 Å, corresponding to the (400) and (311) planes of Fe3O4, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S4f)30. The high-angle annular dark-field-scanning transmission election microscopy (HAADF-STEM) images and energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) element mapping of CA-Fe@BC and Fe@BC indicated the homogeneous distribution of C, N, and O elements (Supplementary Fig. S5). Spherical aberration-corrected high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (AC-HAADF-STEM) was employed for analyzing the atomically dispersed Fe species28,31. As shown in Fig. 2d–f and Supplementary Fig. S6, high-density and uniformly-distributed atomic Fe species (highlighted by solid red circles in high-magnification images) were observed over the CA-Fe@BC catalyst. A high atomic ratio of 6.59: 0.52: 5.94 was acquired for N: Fe: O via XPS analysis (Fig. 2g, Supplementary Fig. S7 and Table S1). In contrast, the Fe@BC catalyst displays much less-density and indistinguishable atomic Fe species doped in the carbon matrix, exhibiting a low atomic ratio of 0.62: 0.28: 13.19 for N: Fe: O (Fig. 2h–k, Supplementary Fig. S7 and Supplementary Table S1). Inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectrometer (ICP-AES) was used to determine the Fe content in the CA-Fe@BC and Fe@BC catalysts, with results of 2.60% and 1.43%, respectively (Supplementary Table S2). The above observation corresponds well with our proposed synthetic mechanisms. The flowthrough C-N based small molecules/radicals from the upstream successfully removes surface oxygen species, promotes the redispersion of sintered FeN0.0324 nanoparticles, and contributes to the Fe-N coordination, leading to a reduced nanoparticle size and the formation of dense Fe-Nx moieties.

a–c TEM images of the CA-Fe@BC catalyst, d, e AC-HAADF-STEM images of the CA-Fe@BC catalyst (the red circles are atomic Fe species), f 3D atom-overlapping Gaussian-function fitting maps of the rectangles area in e. g Relative atomic content of N and Fe for the CA-Fe@BC catalyst. h, i AC-HAADF-STEM images of the Fe@BC catalyst (the red circles are atomic Fe species), j 3D atom-overlapping Gaussian-function fitting maps of the rectangles area in i. k Relative atomic content of N and Fe for the CA-Fe@BC catalyst. Source data for g, k are provided as a Source Data file.

The X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of these catalysts both exhibit a broad peak at 21°, indicating the conversion of bacterial cellulose to amorphous carbon under inert gas and high-temperature conditions (Fig. 3a). Specifically, the Fe@BC catalyst shows characteristic peaks of Fe3O4 and metallic Fe. On the other hand, the XRD pattern of CA-Fe@BC displays characteristic peaks of graphite, metallic Fe, non-stoichiometric compound FeN0.0324, and tiny amount of Fe2C (Fig. 3b). This observation can be rationalized by the vigorous interaction between C-N based small molecules/radicals and Fe nanoparticles during pyrolysis. The porosity of derived catalysts was characterized by N2 adsorption-desorption isotherms. As shown in Fig. 3c–d, both of the CA-Fe@BC and Fe@BC catalysts show Type I and Type IV hybrid isotherms, which present a sharp increase at low relative pressure (P/P0 < 0.1) and a hysteresis at high relative pressure (P/P0 > 0.5). The Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) surface area of the CA-Fe@BC catalyst (601.6 m2 g−1) is slightly larger than that of the Fe@BC catalyst (543.1 m2 g−1). The pore size distribution of the CA-Fe@BC and Fe@BC catalysts are primarily concentrated in the mesoporous range of 3 to 5 nm, providing ideal space for anchoring active sites and substrates transportation.

a, b XRD patterns of the CA-Fe@BC, Fe@BC, CA-BC, and BC catalyst, c the N2 sorption isotherms and d the pore size distributions of the CA-Fe@BC and Fe@BC catalysts (inset: the magnification of dashed box region), e, f Raman spectra, high-resolution XPS spectra of g N 1 s XPS spectra of the CA-Fe@BC-ng catalyst, h Fe 2p, i 57Fe Mössbauer spectra of the CA-Fe@BC catalyst (inset: the magnification of dashed box region), j Fe K-edge X-ray absorption near edge structure (XANES) spectra of the CA-Fe@BC and Fe@BC. k Fourier transformed (FT) k3-weighted w(k)-function of the extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) spectra for the Fe K-edge of the CA-Fe@BC and Fe@BC, l, m the corresponding Fe K-edge EXAFS fitting curves of the CA-Fe@BC and Fe@BC. Source data for a–m are provided as a Source Data file.

We further conducted Raman spectroscopy to explore the defect density of derived catalysts32. All peaks were fitted based on previous literatures (Supplementary Table S3)33. The D band (1350 cm−1) corresponds well to the A1g symmetric breathing mode of disordered and doping defects in graphite. The G band (1580 cm−1) is associated with the E2g vibration mode of ordered sp2 hybridized carbon atoms34,35. A higher ratio of intensity between the D peak and G peak indicates a higher defect density. As shown in Fig. 3e, the application of CA approach and doping Fe enhanced the defect density of derived catalysts. The ID/IG values of the catalysts derived with different amount of CA agents were also compared (Fig. 3f). Apparently, the value grows with the increasing the dosage of CA agent (CA-Fe@BC-10g > CA-Fe@BC-7.5 g > Fe@BC), indicating the enhancement in defect density. Herein, the suffix “-ng” is the mass of melamine used as CA agent (the same below).

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was employed to assess the surface valence states and bonding configurations of C, N, O and Fe in the derived SACs20. The survey spectra show the presence and relative content of C, N, O, and Fe (Supplementary Fig. S7a, b and Table S1). The relative atomic percentage of N and Fe in the catalysts markedly increases by using the CA approach, and continuously rises with enhancing the doping amount of CA agents. The content of O shows a descending trend with increasing the dosage of melamine. CA-Fe@BC-10g has the highest N and Fe content, and lowest O content, indicating superiority of CA approach for modulating the N and O content as well as the coordination environment of Fe species. The C 1 s peak was deconvoluted into five sub-peaks (Supplementary Fig. S7c–e): sp2 hybridized carbon (284.4 eV), sp3 hybridized carbon (285.2 eV), C-N (286.6 eV), C-O (287.8 eV), and O-C=O (289 eV), respectively36, with a separation of 0.8 eV between sp3 and sp2 peaks37. The ratio of sp3 to sp2 components (Supplementary Fig. S7f and Table S4) shows an uptrend with the increase of melamine used as the CA agent (CA-Fe@BC-10g > CA-Fe@BC-7.5 g > Fe@BC). Notably, this result aligns with the trend of Raman spectroscopy, further indicating that the CA approach significantly enhanced the sp3 defects in the catalysts. The N 1 s spectra were fitted into pyridinic N (398.3 eV), Fe-N (399.3 eV), pyrrolic N (400.7 eV), graphitic N (401.5 eV), and oxidized N (403.5 eV), respectively (Fig. 3g)23,27. Further analysis reveals that CA-Fe@BC-10g has a higher relative content of pyridinic N (43.03%) and Fe-N (19.61%) (Supplementary Fig. S8a and Table S5)29. More importantly, the absolute content of Fe-N shows an upward tendency of CA-Fe@BC-10g (10.2%) > CA-Fe@BC-7.5 g (10.1%) > Fe@BC (2.4%). The Fe-N4 moieties is composed by Fe-N, hence the density of Fe-N4 moieties in derived catalysts should follow the same order.

The Fe 2p spectra of the catalysts all exhibited peaks corresponding to Fe3+ at 713.8 eV and 726.9 eV, Fe2+ at 710.6 eV and 723.7 eV, and Fe0 at 708.0 eV and 721.1 eV, respectively (Fig. 3h)30,38. The CA-Fe@BC showed the highest proportion of Fe2+ compared to other catalysts (Supplementary Fig. S8b). The O 1 s spectra were divided into Fe-O (530.0 eV), C-O (532.2 eV), and C=O (534.0 eV) (Supplementary Fig. S7g–i)36,39. Compared to the Fe@BC catalyst, the Fe-O content in the catalysts derived with CA strategy was significantly reduced and CA-Fe@BC-10g exhibited the lowest Fe-O content (Supplementary Fig. S7j and Table S6). Mössbauer spectroscopy was further employed to study the chemical environments and spin states of Fe in the CA-Fe@BC catalyst. According to previous literatures31,40, the signals of Mössbauer spectra were attributed to specific forms of Fe species (Supplementary Table S7)41,42. As shown in Fig. 3i, the Fe species in CA-Fe@BC appear in the forms of superparamagnetic iron, Fe-N4, α-Fe and iron carbide or nitride. More importantly, the Mössbauer spectroscopy indicated the presence of Fe-N4 moieties in CA-Fe@BC, where the Fe ions are in a low-spin Fe(II) state (S = 0)41. This spin state is related to the low electron density around the Fe center and considered a species with high activity for the ORR.

In order to further detect the coordination environments of Fe-N species in derived catalysts, the synchrotron radiation EXAFS tests were performed by employing Fe foil, Fe3O4 and iron phthalocyanine (FePC) as the references. As shown in Fig. 3j, the absorption edge curve of CA-Fe@BC showed a slight shift to the direction of high energy by comparing with the contrast Fe foil, while the trend of Fe@BC absorption edge agrees well with that of Fe foil (see the Position 1). This indicates that the difference of Fe coordination in CA-Fe@BC and Fe@BC. Note that, CA-Fe@BC does not exhibit trough but a small bump at Position 2, which is different from Fe@BC and Fe foil but slightly close to FePC. It means that more Fe-N species were formed in CA-Fe@BC than Fe@BC. Figure 3k presents the individual and combined EXAFS spectra of studied samples. Similar to Fe foil, both CA-Fe@BC and Fe@BC display Fe-Fe peaks (the arrow position), but the peak intensity decreases in the sequence of CA-Fe@BC < Fe@BC < Fe foil. Meanwhile, the peak position of CA-Fe@BC slightly shifts to the direction of low radical distance. This phenomenon indicates CA-Fe@BC shows smaller Fe particle size and lower Fe-Fe coordination number than Fe@BC. More importantly, Fig. 3l, m and Supplementary Fig. S9a–e reveal a distinct Fe-N peak in CA-Fe@BC, with a coordination number close to four, which directly confirms the presence of Fe-N4 structure. In contrast, although Fe-O/Fe-N peaks were also detected in Fe@BC, the Fe-N coordination number is much lower, indicating that the much less Fe-N4 content in Fe@BC. These observations are consistent with the results of aberration-corrected TEM, Mössbauer spectroscopy, and TEM. The specific structural fitting parameters are summarized in Supplementary Table S8.

As has intensively proved previously, the CA approach could change the Fe coordination environment of derived carbon supported catalysts. The mechanism of CA approach removing O and enhancing N doping is highly related to the complicated decomposition process of melamine. According to the mass spectrometry results43, melamine sublimated in the range of 150–250 °C, meanwhile part of them decomposed into small molecules and radicals, including C2N2H2, C2N2H3, C2N3H2, C2N4H5, etc.; then further decomposed into HCN, NH3, etc. Moreover, melamine also undergoes condensation on heating with elimination of N and H atoms, and formation of melam, melem, melon and even C3N4 in the range of 400–700 °C. On one hand, the intermediates of C-N based small molecules/radicals would react with the hydroxyl group of BC cellulose to remove oxygen and deposit N into the skeleton. On the other hand, the N-enriched condensation products of melam, melem, melon and C3N4 mixed with BC cellulose and enhance the N doping level of derived carbon matrix.

High temperature was necessary to anchor Fe SACs onto carbon matrix, but could also exacerbate the migration and clustering of Fe ions, making it difficult to achieve a high density and high dispersion of Fe SACs. Loading ion macrocyclic complexes as the Fe source and benefiting the superiority of CA approach, the Fe SACs in derived catalysts significantly enhanced. At low temperatures, the Fe ions were protected and isolated by bpy and the C-N small molecules and radicals. When temperature rises, most of the protectors were decomposed into gases, but the N-enriched condensation products and the deposit N into the BC by heating melamine could partially retained. These N could bond with some of the Fe ions to form Fe SACs at high temperature.

ORR performance

The ORR activity of derived catalysts was both evaluated in alkaline, acidic and neutral electrolyte (0.1 M KOH, 0.05 M H2SO4 and 0.1 M phosphate buffered saline (PBS)). Commercial 20 wt% Pt/C (denoted as Pt/C in the following) was employed as the reference. As shown in Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. S10, linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) curves demonstrated that the catalysts derived by CA approach showed better ORR activity than other studied cases and Pt/C in alkaline electrolyte. Specifically, the CA-Fe@BC-10g catalyst exhibited excellent ORR activity with an onset potential (Eonset) of 1.07 V and a half-wave potential (E1/2) of 0.93 ± 0.005 V with a significantly high limiting-current density ( JL) of 5.47 mA cm−2, which exceeded most reported non-noble metal-based ORR catalysts (Supplementary Table S9). Of note, the E1/2 of derived catalysts increased with more melamine was utilized (Fig. 4a). The CA-Fe@BC-10g catalyst also showed a smaller Tafel slope than other catalysts (Fig. 4b). Furthermore, the kinetic current density (Jk) was also calculated by Koutecky-Levich (K-L) equation. As shown in Fig. 4b, CA-Fe@BC exhibited a high JK of 55.13 ± 1.71 mA cm−2 at the potential of 0.85 V44, which is 8.76 times that of the benchmark Pt/C catalyst (6.29 ± 0.84 mA cm−2). The Jk of studied catalysts displays an uptrend of CA-Fe@BC-10g (55.13 ± 1.71 mA cm−2) > CA- Fe@BC-5g (21.73 ± 2.74 mA cm−2) > CA-Fe@BC-7.5 g (18.96 ± 3.27 mA cm−2) > CA-Fe@BC-2.5 g (13.85 ± 1.52 mA cm−2) > Pt/C (6.29 ± 0.84 mA cm−2) > Fe@BC (0.50 ± 0.327 mA cm−2). We systematically evaluated the influence of pyrolysis temperature, the distance between CA agent and precursor, CA agent dosage, and the concentration of Fe(bpy)3Cl2 for ORR performance, detailed results and discussions can be found in Supplementary Figs. S11–S12. All these results indicate that CA-Fe@BC-10g displayed the best reaction kinetics for the ORR. An average electron-transfer number (n) of 3.96 was calculated by the K-L equation for the CA-Fe@BC catalyst (Fig. 4c), which was also verified by the rotating ring-disk electrode (RRDE) method (n = 3.92) (Supplementary Fig. S13). Meanwhile, the RRDE measurements demonstrate an exceedingly low H2O2 yield of 4.13% for the CA-Fe@BC catalyst, far below the 6.19% observed for commercial Pt/C (Supplementary Fig. S13). These results further indicated that the reduction of O2 underwent a high selective four-electron path over the CA-Fe@BC catalyst. In addition, the conductivity of working electrodes was analyzed by electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) measurements. As shown in Supplementary Fig. S14, CA-Fe@BC and Pt/C Catalysis exhibit a small EIS semicircle diameter of 12.5 and 16.3 Ω, indicating that the most efficient electron transfer occured at the interface between catalysts and the electrolyte.

a iR corrected LSV curves in 0.1 M KOH (pH = 13 ± 0.10), b Tafel plots, JK and E1/2 for the CA-Fe@BC-ng, Fe@BC, CA-BC, BC, and commercial Pt/C catalysts at a rotating rate of 1600 rpm in O2-saturated alkaline medium, c kinetic-limiting current densities of ORR over the CA-Fe@BC catalyst at different rotating speeds, inset curves are K-L plots at various potentials, d iR corrected LSV curves recorded before and after 10,000 CV cycles, e amperometric i-t curves at applied potential of 0.5 V in alkaline medium, inset curves are the i-t responses at 0.5 V and 1600 rpm by adding 1.0 M methanol at around 200 s, f comparison \({\triangle}\)E1/2 (E1/2-catalyst - E1/2-Pt/C) of the CA-Fe@BC-ng catalyst. g iR corrected LSV curves in 0.5 M H2SO4 (pH = 1 ± 0.06), h Tafel plots, JK and E1/2 for the CA-Fe@BC, Fe@BC, CA-BC, BC, and commercial Pt/C catalysts at a rotating rate of 1600 rpm in O2-saturated acidic medium, i kinetic-limiting current densities of ORR on the CA-Fe@BC catalyst at different rotating speeds, inset curves are K-L plots at various potentials. j iR corrected LSV curves in O2 -saturated in 0.1 M PBS (pH = 7.2 ± 0.12) at 50 mV s−1, k Tafel plots, JK and E1/2 for the CA-Fe@BC, Fe@BC, CA-BC, and commercial Pt/C catalysts at a rotating rate of 1600 rpm in O2-saturated neutral medium, l kinetic-limiting current densities of ORR over the CA-Fe@BC catalyst at different rotating speeds, inset curves are K-L plots at various potentials. The error bars represent the standard deviation, which were obtained from four independent samples and at least three independent measurements for each sample. iR correction was conducted at 100% automatically. Source data for (a–l) are provided as a Source Data file.

We further evaluated the stability of the catalysts. As shown in Fig. 4d, the CA-Fe@BC catalyst exhibited negligible decrease in E1/2 and JL after 10,000 CV scans, while those for Pt/C catalyst dropped sharply. CA-Fe@BC also maintained a higher current density than Pt/C after a 24-h amperometric i-t test in an alkaline medium (Fig. 4e). After injecting 1.0 M methanol into the electrolyte during the test, the current density of the CA-Fe@BC catalyst virtually unchanged, but a significant decay was observed for Pt/C (Fig. 4e, inset). These observations revealed superior durability and methanol tolerance of CA-Fe@BC catalyst compared to the Pt/C reference. Further characterizations on the spent CA-Fe@BC catalyst after 10,000 CV scans were performed using XPS spectroscopy (Supplementary Fig. S15) and TEM (Supplementary Fig. S16), indicating no significant changes in fine spectral peak shapes, morphology, and microstructure (Supplementary Table S4–S7). We also compared the \({\triangle}\)E1/2 (E1/2(catalyst) - E1/2(Pt/C)) of different CA-Fe@BC-ng catalysts (Fig. 4f). The ORR activity of studied catalysts follows the sequence of CA-Fe@BC-10g > CA-Fe@BC-7.5 g > CA-Fe@BC-5g > CA-Fe@BC−2.5 g > Fe@BC (Fig. 4f), indicating the superior ORR activity of CA-Fe@BC−10g.

In acidic medium, the LSV curves illustrate that the ORR activity of the CA-Fe@BC catalyst (Eonset = 0.86 V, E1/2 = 0.78 ± 0.004 V and JL = 5.60 mA cm−2) was higher than Pt/C (Eonset = 0.90 V, E1/2 = 0.76 ± 0.012 V and JL = 5.32 mA cm−2) and other control cases (Fig. 4g). Moreover, CA-Fe@BC displayed a remarkably lower Tafel slope of 64.10 mV dec−1 than 95.62 mV dec−1 for Pt/C, further substantiating the superior ORR catalytic activity (Fig. 4h). The JK for CA-Fe@BC is 7.76 ± 0.52 mA cm−2 at 0.75 V, nearly 1.3 times higher than Pt/C (5.98 ± 0.27 mA cm−2). The electron-transfer number n was determined to be 3.95 for CA-Fe@BC, suggesting the first-order reaction kinetics and four-electron pathway of the ORR (Fig. 4i), which was also verified by the RRDE method (n = 3.99) (Supplementary Fig. S17). Subsequent durability testing under acidic conditions indicates that, CA-Fe@BC exhibited no notable decline after 10,000 CV scans. In contrast, Pt/C experienced a significant drop of 3 mV and 0.46 mA cm−2 for E1/2 and JL, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S18).

In a 0.1 M PBS neutral medium, the LSV curves of CA-Fe@BC indicate that its ORR activity (Eonset = 0.76 V, E1/2 = 0.62 ± 0.013 V, JL = 5.18 mA cm−2) was higher than that of the Pt/C catalyst (Eonset = 0.76 V, E1/2 = 0.56 ± 0.011 V, JL = 5.17 mA cm−2) and other catalysts (Fig. 4j). The Tafel slope of CA-Fe@BC was lower than Pt/C (96.68 mV dec−1 vs 135.25 mV 0.dec−1), further confirming the superior ORR activity of CA-Fe@BC in neutral medium (Fig. 4k). At 0.55 V, the JK of CA-Fe@BC is 32.98 ± 2.34 mA cm−2, nearly five times that of Pt/C (6.60 ± 1.65 mA cm−2). Subsequently, durability tests under neutral conditions showed that after 10,000 CV scans, the E1/2 of CA-Fe@BC decreased by only 4 mV, while the E1/2 of Pt/C decreased significantly by 25 mV (Supplementary Fig. S19). The number of electron transfers, n, for CA-Fe@BC was determined to be 3.91 (Fig. 4l), which was also verified by the RRDE method (n = 3.99) (Supplementary Fig. S20).

Faradaic efficiency (FE) was also calculated according to the method reported in previous literature45. The H2O2 FE for CA-Fe@BC in alkaline, acidic and neutral electrolyte is 2.70%, 0.18% and 0.16%, respectively. While the FE for Pt/C in alkaline, acidic and neutral electrolyte is 4.49%, 0.10% and 0.07%, respectively. The low H2O2 FE demonstrated that the CA-Fe@BC and Pt/C preferred the four-electron pathway for the ORR (Supplementary Fig. S21).

DFT calculations

We further conducted DFT calculations to clarify the underlying mechanism for the enhanced ORR activity via CA approach. As mentioned above, the CA approach induced a distinct coordination tuning from dominated Fe-O to Fe-N moieties. However, it remains a big challenge to truly identify the atomic structure and relative ratio for different active sites with complex coordination environments. To this end, we designed 8 possible models with different Fe-O/Fe-N/Fe-C coordination environments to evaluate the influence of coordination environments on the ORR activity (Fig. 5a). See Supplementary Data 1 for the crystal structure files (cif). Before that, the thermodynamic and kinetic stability of the 8 possible models were examined by calculating the formation energy (Ef) (Supplementary Table S10). The results indicate that all the models are thermodynamically stable. The Gibbs free energy barriers (ΔG) of the studied models are listed in Supplementary Table S11–S13. Of note, the potential determining step (PDS) for the models is the last step (OH* → OH-), except Fe-N2-N2 (pyridinic + pyrrolic), Fe-N4 (Pyrrolic) and Fe-N3-O moieties, which are * + O2 → OO*, OOH* → O* and OO* → OOH*, respectively. As shown in Fig. 5b, the free-energy diagrams for Fe-N2-N2 (pyridinic + pyrrolic), Fe-N4 (pyrrolic), Fe-N4 (pyridinic), Fe-N3-O, Fe-N3-C, and Fe-N2-C2 moieties showed a downhill step. The catalytic activity of these models for the ORR displayed a decline trend in that order by comparing the ΔG of the PDS. In contrast, the oxygen-rich Fe-N2-O2 and Fe-O3 moieties needed to overcome an energy barrier of +0.323 eV and +1.055 eV in their PDS, respectively, indicating they are less active for the ORR. The ORR reaction path on Fe-N2-N2 (pyridinic + pyrrolic) was diagramed in Fig. 5c. Based on above discussions, it is concluded that the coordination of Fe centers could significantly influence the ORR activity of derived catalysts and an N coordination should be much more favorable than O coordination46,47,48,49.

a Optimized models for calculation. b The free-energy diagram of the studied models. c Schematic illustration of the interaction between active sites of the model of Fe-N2-N2 (pyridinic + pyrrolic) and the OO*, OOH*, O*, OH* intermediates during the ORR process. Gray, red, blue, green and cyan are C, O, N, Fe and H atom, respectively. Source data for b are provided as a Source Data file.

Moreover, another two series of typical pyridinic- (C9) and pyrrolic-based (C12) models50 were also adopted to verify the above conclusion by altering the environment of coordinated Fe with O atoms (Supplementary Fig. S22a). See Supplementary Data 1 for the crystal structure files (cif). The negative formation energies indicate that the models are thermodynamically stable (Supplementary Table S10). The free-energy diagrams for Fe-N3-C9, Fe-N2O-C9 and Fe-N3-C12 displayed a stepwise downhill. Nevertheless, the alteration of Fe coordination with O turned this trend for, which means that an energy barrier needed to be surmounted to render the ORR reactions for these moieties (Supplementary Fig. S22b). This observation is consistent with that of above-mentioned 8 possible models and could also serve as a proof for the sensitivity of the ORR activity of Fe-SAC center coordination to the O.

Zinc-air batteries tests

To assess the potential of the catalysts for practical application in energy storage and conversion devices, we loaded the catalysts onto a carbon fiber paper electrode as the air cathode for ZAB tests (Fig. 6a). Polished zinc foil was used as the anode. A 6 M KOH and 0.2 M zinc acetate aqueous solution was used as the electrolyte. For comparison, another ZAB was also assembled adopting commercial Pt/C as the air cathode. As shown in Fig. 6b, the CA-Fe@BC-based battery achieved a maximum power density of 227.61 mW cm−2, which is twice that of Pt/C battery (108.05 mW cm−2) and exceeded previously reported non-precious metal catalysts (Supplementary Table S14). The open-circuit voltage (OCV) of CA-Fe@BC-based battery reached 1.57 V, surpassing the 1.41 V of Pt/C battery (Fig. 6c). When two such batteries connected in series, the OCV reaches 3.17 V, demonstrating its capability to deliver higher voltage, enabling the effortless rotating of a small motor (Fig. 6d). The CA-Fe@BC-based battery also exhibits exceptional rate performance, showing no significant potential drop at different current densities of 1, 2, 5, 10, 20, 50, 100, and 1 mA cm−2, better than the Pt/C-based battery (Fig. 6e). The specific capacity of the CA-Fe@BC-based battery reached 792 mA h gZn−1 at the discharge current density of 5 mA cm−2, higher than that of the Pt/C-based battery (621 mA h gZn−1) (Fig. 6f). As shown in Fig. 6g, the CA-Fe@BC-based battery showed good rechargeability, with an initial charge potential of 1.22 V and a discharge potential of 1.97 V, which has a smaller charge-discharge voltage gap than Pt/C battery. The CA-Fe@BC-based battery exhibits ultra-high durability up to 650 h of charge-discharge cycling without significant degradation, which was much longer than Pt/C battery (Fig. 6g). The superior ZAB performance further highlighted the unlimited potential of the CA-Fe@BC catalyst in energy-related applications.

a Schematic illustration of the ZAB setup. b Discharging polarization and power density curves of the ZABs. c Open-circuit voltage of the ZABs. d A motor powered by two CA-Fe@BC-based ZABs in series. e Discharge curves under different current densities (1, 2, 5, 10, 20, 50, 100 mA cm−2) of the ZABs. f Specific capacity curves of the ZABs. g Cycling durability tests at 5 mA cm−2 of the ZABs. Source data for (b, c) and (e–g) are provided as a Source Data file.

Discussion

In summary, we developed a facile continuous activation (CA) approach for synthesizing robust biomass-derived Fe SACs. By providing continuous C-N based small molecules/radicals at the upstream of the loaded precursors during pyrolysis, the surface oxygen groups inside the biomass materials were sufficiently etched away, liberating the dispersion of single atoms from the oxophilicity. We thus observed a high Fe atom density of 4.70 atoms nm−2. Simultaneously, the CA approach induced a distinct coordination tuning from dominated Fe-O to Fe-N moieties. The CA-derived high density, N-rich Fe SACs exhibited a high pH-universal ORR performance with a half-wave potential of 0.93 V vs. RHE, 0.78 V vs. RHE and 0.62 V vs. RHE in alkaline, acidic and neutral electrolyte, respectively. DFT calculations further revealed that the increased Fe-N coordination effectively changes the potential determining step and reduced the energy barriers for the ORR, thus enhancing the catalytic activity. The potential of the catalysts for practical application in energy storage and conversion devices was also proved by superior ZAB performance. Our work provides a promising method for substrate engineering, broadening potential host material categories for SAC fabrication in a more sustainable and economical manner. Besides, we believe our strategy can be easily extended to synthesize other element (e.g., S and P) coordinated SACs by changing the CA agent properly.

Methods

Catalysts preparation

Materials and chemicals

Iron(II) chloride tetrahydrate (FeCl2·4H2O, 99%), 2,2’-bipyridine (bpy, ≥99%), melamine (C3H6N6, ≥99%), potassium hydroxide (KOH, ≥99%), sulfuric acid (H2SO4, 98%), 0.1 M PBS, and ethanol were purchased from Aladdin Industrial Co. Ltd. 5% Nafion was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Bacterial cellulose hydrogel with a cubic structure of 1 cm × 1 cm × 1 cm was supplied by Hainan Yide Food Co., Ltd. These chemicals were used as received without further purification. Ultrapure water was self-made.

Pretreatment of bacterial cellulose

The bacterial cellulose hydrogel cubes were immersed in a large quantity of deionized (DI) water with continuous stirring. The water was changed every 3 h for 10 times, until a neutral pH was reached. The cleaned bacterial cellulose was stored in water at 4 °C for further use.

Synthesis of Fe(bpy)3Cl2

5 mmol FeCl2 was dissolved in 100 mL ultrapure water, and then 15 mmol 2,2’-bipyridine in 100 ml ethanol, afterwards the mixture was heated to boiling for 2 h. After evaporating the solvents and impurities, the Fe(bpy)3Cl2 was dried under vacuum at 60 °C overnight.

Impregnating bacterial cellulose with Fe(bpy)3Cl2 aqueous solution

A mass of 0.1665/0.2081/0.2497/0.2914/0.3330/0.3746 g Fe(bpy)3Cl2 was dissloved in 70 mL DI water to prepare Fe(bpy)3Cl2 aqueous solution with the concentration of 4/5/6/7/8/9 mmol L−1, then 70 pieces of wet bacterial cellulose cubes were immersed for impregnation. Fe(bpy)3Cl2 loaded bacterial cellulose precursors were obtained under continuous agitation at 240 revolutions per minute in a water bath at a temperature of 40 °C for a duration of 24 h. All the precursors were freeze-dried prior to pyrolysis.

Pyrolysis process

The catalyst preparation was conducted in a tube furnace using Ar as the carrier gas. The size of the tube is Φ50 × 1000 mm, the length of heating area is 400 mm, and the length of thermostatic zone is 200 mm. Prior to the pyrolysis, the thermal field of tube furnace was measured, and the result is shown in Fig. S1. Different mass of dried bacterial cellulose loaded with Fe(bpy)3Cl2 were placed at the center of the thermostatic zone, while varying mass of melamine were placed at the upstream of the bacterial cellulose precursor with different distance. The system was maintained at room temperature for 1 h and then ramped up to the desired temperature at a rate of 5 °C min−2. After a 2-h holding time at the target temperature, the system cooled naturally.

Catalysts characterizations

SEM images of the samples were characterized using a ZEISS Sigma 300. TEM images were obtained for characterization through the FEI Talos F200x. Spherical aberration-corrected TEM analysis of the samples was conducted on the FEI Themis Z. The powder XRD patterns of the samples were recorded using an Ultima IV diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation (Cu Kα, λ = 0.15406 nm, 40 kV, and 15 mA), in the 2θ angle range from 5o to 80o, with a step size of 0.02o, and a scan speed of 2o min−1. The N2 isothermal adsorption-desorption curves (BET) of the samples were characterized using the 3Flex automatic specific surface pore size analyzer. Raman data for the samples were acquired using a LabRam HR Evolution with a 532 nm excitation source. XPS analysis of the samples was performed on the Thermo Scientific K-Alpha. Mössbauer spectra were acquired as raw data from the MFD-500AV instrument. Elemental analysis of Fe and Co in the solid samples was detected by an Optima 7300 DV ICP-AES. X-ray absorption fine structure (XAFS) measurement and data analysis: The XAFS spectra at the Fe K-edge (7112 eV) were measured at the 1W1B station of the Beijing Synchrotron Radiation Facility, China. The Fe K-edge XANES data were recorded in fluorescence mode, using Fe foil, FePc, and Fe3O4 as references. The storage ring operated at energy of 2.5 GeV with an average electron current of 250 mA. The hard X-ray was monochromatized using Si (111) double crystals. The acquired EXAFS data were extracted and processed according to standard procedures using the ATHENA module in the IFEFFIT software package. By subtracting the post-edge background from the overall absorption and normalizing to the edge jump, the k3-weighted EXAFS spectra were obtained. Subsequently, the k3-weighted χ (k) data in the k-space, ranging from 0 to 6 Å−1, were Fourier transformed to real (R) space using a Hanning window (dK = 1.0 Å−1) to distinguish the EXAFS contributions from different coordination shells.

Electrochemical measurements for the ORR

The preparation of all catalytic inks involves mixing 3 mg of the catalyst with 250 μL of ultrapure water, 225 μL of ethanol, and 5% Nafion (25 μL). Subsequently, the mixture is sonicated for 40 min to achieve a homogeneous state. The catalyst ink was spread on the electrode by rotating method (Supplementary Fig. S23). 20 μL and 25 μL of the inks are separately drop-casted onto the central areas of the rotating disk electrode (RDE) and RRDE in 5 times (each time 5 μL), respectively, thereby completing the catalyst loading process. Note that, RDE and RRDE are made of glassy carbon, with circle surface areas of 0.19625 cm2 and 0.2475 cm2, respectively. The catalyst loading amount was 0.61 mg·cm−2 (calculating by Ccatalyst × Vink/Selectrode area, herein Ccatalyst, Vink and Selectrode area are the concentration of catalyst, volume of ink and surface area of working electrode). The preparation of the commercially available Pt/C catalyst ink for comparative purposes follows the exact same procedure as for the samples. 5.6 g KOH dissolved in 100 mL ultrapure water and then diluted to the volume of 1 L after cooling for the preparation of 0.1 M KOH. 0.05 M H2SO4 was prepared by slowly adding 2.7 mL H2SO4 (98%) into 100 mL ultrapure water under stirring and then diluted to the volume of 1 L. All electrolyte solutions were used freshly.

All electrochemical tests are carried out in the open air under room temperature. The electrochemical testing was conducted in a three-electrode system using a CHI 760E electrochemical workstation (Shanghai Chenhua, China). Counter electrode, reference electrode and electrochemical cell were supplied by Gaossunion, China. RDE, RRDE and rotating system were purchased from PINE, US. 100 mL of the fresh electrolyte solutions of alkaline 0.1 M KOH (pH = 13 ± 0.10), acidic 0.05 M H2SO4 (pH = 1 ± 0.06) and neutral 0.1 M PBS (pH = 7.2 ± 0.12) solution were used for each test. RDE and RRDE were employed as the working electrodes, saturated calomel electrode (SCE) was used as the reference electrode, and graphite served as the counter electrode. All the data were recorded by electrochemical workstation and directly used for plotting. The obtained SCE potential (E(vs. SCE)) was converted to RHE potential (E(vs. SCE)) by the formula of E(vs. RHE) = E(vs. SCE) + 0.2414 V + 0.0591 × pH.

Before the measurements, the reference electrode SCE was calibrated in a saturated KCl electrolyte solution (the same as the solution in SCE) at 25 °C by referring an identical standard SCE electrode. The SCE to be calibrated was used as working electrode and the identical standard SCE electrode was used as the reference electrode. Then the open-circuit voltage between the two electrodes was measured. The potential should be within ±5 mV.

Prior to the tests, the electrolyte was purged with N2/O2 gas for 30 min to achieve N2/O2 saturation. LSV was performed on the RDE at various rotation speeds (400–2025 rpm) with a scan rate of 5 mV s−1. CV under N2/O2 saturation conditions was conducted with a scan rate of 50 mV s−1 for both acidic and alkaline conditions. For the ORR tests using RDE, the Koutecky-Levich Eqs. 1 and 2 were employed to calculate the number of transferred electrons (n) and the kinetic current density (JK).

In this equation, j and jk represent the measured current density and kinetic current density, respectively, while “ω” denotes the electrode rotation rate. “F” is the Faraday constant (F = 96485 C mol−1); “C0” is the oxygen concentration in the 0.1 M KOH solution (C0 = 1.2 × 10−6 mol cm−3); “D0” stands for the oxygen diffusion coefficient in the electrolyte (D0 = 1.9 × 10-5 cm² s−1); “V” indicates the dynamic viscosity of the electrolyte (V = 0.01 cm² s−1). The constant 0.2 is applicable when the rotation speed is in rpm units. When “ω” represents angular velocity, this constant becomes 0.62.

RRDE is employed for the measurement of the catalyst’s electron transfer number and peroxide yield (H2O2%), with the reference Formula 3 and 4 provided below:

“Id” represents the disk current, “Ir” denotes the ring current, and “N” stands for the collection efficiency of the ring electrode, with a value of 0.37.

Accelerated durability testing of the catalyst was conducted in oxygen-saturated 0.1 M KOH, under ambient temperature conditions, cycling for 10,000 cycles in the potential range of 0.86 V to 0.96 V vs. RHE at a scan rate of 100 mV s−1.

Faradaic efficiency (FE), H2O2 selectivity and electron transfer number on the rotating ring-disk electrode was calculated based on the current of both disc and ring electrodes.

Electrochemical measurements for Zn-air batteries

Zinc-air batteries was assembled with the use of a 0.5 mm-thick zinc foil as the anode, a carbon paper coated with CA-Fe@BC (at a loading of 1 mg cm−2) as the air cathode, and a 6 M KOH solution containing 0.2 M Zn(CH3COO)2 as the air cathode. The two electrodes were co-assembled in a sealed mold. For comparison, an alternative ZAB was assembled with a cathode loaded with the same weight proportion of Pt/C. All performance tests were conducted in the open air under room temperature. Cycling experiments were performed using periodic constant current pulses of 5 min charging and 5 min discharging, with a current density of j = 5 mA cm−2. The catalysts ink of the ZAB assembled for charge-discharge cycling tests are 2.5 mg of CA-Fe@BC or Pt/C and 2.5 mg of RuO2, along with 1 ml of ethanol and 100 μL of Nafion, which were then mixed and sonicated for 40 min to prepare the cathode catalyst.

DFT computational methods

Herein, spin-polarization DFT calculations were performed with the Vienna ab initio simulation package VASP. The exchange-correlation functional generalized gradient approximation (GGA) of the Perdew, Burke, and Ernzerhof (PBE) was used, and a plane wave basis set using the projector-augmented wave (PAW) with the cutoff energy of 500 eV was employed. The Brillouin zone was sampled with 5 × 5 × 1 and 12 × 12 × 1 Monkhorst-Pack meshes for structure relaxation and electronic properties calculations, respectively. A 15 Å vacuum was added to avoid spurious interaction between layers in the Z direction. Convergence tolerance of electronic energy, maximum force was set as 1 × 10−5 eV and 0.01 eV Å−1, respectively. Dispersion effects were augmented by Grimme’s correction scheme of 2010 (DFT-D3).

Monolayer graphene was used as a carbon carrier for the catalysts. The graphite Fe-N/C/On site was embedded in a 5 × 5 orthogonal graphene supercell containing 50 carbon sites, lattice parameter a = b = 12.30 Å, and three-dimensional boundary condition was periodic. For example, the Fe-N2-N2 (pyridinic + pyrrolic) system was constructed as follows: Firstly, six adjacent C atoms were removed from the original graphene plate to establish the carbon defect surface, and atomic Fe species was embedded in the middle position of the carbon defect. Then, two pyridinic N and two pyrrolic N atoms were introduced to replace the C atoms directly connected to the Fe center. The rest models were built similarly. The crystal structure files (cif) of the models for DFT calculations are provided as Supplementary Data 1.

In alkaline electrolytes, the ORR on atomic Fe species was considered to proceed along the 4e- processes (overall process O2 + 2H2O + 4 e- → 4OH-), as below:

And 2e- processes as below:

where * stands for the adsorption site on the surfaces. To quantitatively assess the activity of the atomic Fe species, we calculated the adsorption energy of each intermediate following the approach of Nørskov et al. reported51,

where, for example, E*O denoted the total energy of an oxygen atom adsorbed on the substrate obtained by the calculations, H2O and H2 in gas phases were used for references. The more positive of the binding energy is, the weaker of the interaction between intermediates and the Fe center would be.

Then we converted the ground state energy into Gibbs free energy at standard state (298.15 K, 0.1 Mpa), and the solution pH of the adsorbates was also included,

where, ∆E was the adsorption energy of each intermediate, ∆ZPE and ∆S presented the differences of zero-point energy and entropy between the products and reactants, ∆GU = -qU, where U is the electrode potential, ∆GpH = kBTln10×(pH), kB is the Boltzmann constant, in this work, pH = 14 was employed in the alkaline electrolyte.

The reference energy of O2 and OH- - e- were obtained from the following expressions,

where, ∆Gw = −2.46 eV was the experimental formation energy of water molecule. The detailed results can be seen in Supplementary Table S9.

To check the energetic stability of the systems, we have calculated the formation energy (Ef) using the following expression and the values are shown in Supplementary Table S1052. Herein, the calculation of μFe was the bulk energy per metal atom Fe with the respective stable crystal structure.

where Emodified layer is the DFT-calculated energy of our modified graphene layer systems; EP is the energy of the pristine graphene sheet; and nc, nN, nO and nM are the total numbers of carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, and metal atoms, respectively, in our proposed systems. \(\mu\)i is the chemical potential of atomic species i (i = C, N, O, TM) in the doped graphene. \(\mu\)c is the energy of a carbon atom in graphene. \(\mu\)N and \(\mu\)O are half of the electronic energy of an N2 molecule and O2 gas phase, respectively. \(\mu\)M is the bulk energy per metal atom Fe with the respective stable crystal structure. n is the total number of atoms in our system.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available in the paper and the Supplementary Information. Source data are provided with this paper. Any other relevant data are also available from the corresponding authors upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Tian, X. et al. Engineering bunched Pt-Ni alloy nanocages for efficient oxygen reduction in practical fuel cells. Science 366, 850–856 (2019).

Liu, K. et al. Insights into the activity of single-atom Fe-NC catalysts for oxygen reduction reaction. Nat. Commun. 13, 2075 (2022).

Debe, M. K. Electrocatalyst approaches and challenges for automotive fuel cells. Nature 486, 43–51 (2012).

Du, M., Li, D., Liu, S. & Yan, J. Practical classification of catalysts for oxygen reduction reactions: optimization strategies and mechanistic analysis. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2301527 (2023).

Yan, J. et al. Facile synthesis of bimetallic fluoride heterojunctions on defect-enriched porous carbon nanofibers for efficient ORR catalysts. Nano Lett. 21, 2618–2624 (2021).

Xia, C. et al. General synthesis of single-atom catalysts with high metal loading using graphene quantum dots. Nat. Chem. 13, 887–894 (2021).

Povarov, K. Y. et al. Pressure-tuned quantum criticality in the large-D antiferromagnet DTN. Nat. Commun. 15, 2295 (2024).

Chen, Y. et al. Atomic‐level modulation of electronic density at cobalt single‐atom sites derived from metal-organic frameworks: Enhanced oxygen reduction performance. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 3212–3221 (2021).

Wang, J., Li, Z., Wu, Y. & Li, Y. Fabrication of single‐atom catalysts with precise structure and high metal loading. Adv. Mater. 30, 1801649 (2018).

Kumar, P. et al. High-density cobalt single-atom catalysts for enhanced oxygen evolution reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 8052–8063 (2023).

Saptal, V. B., Ruta, V., Bajada, M. A. & Vilé, G. Single‐atom catalysis in organic synthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202219306 (2023).

Hu, Y. et al. Progress in batch preparation of single-atom catalysts and application in sustainable synthesis of fine chemicals. Green Chem. 23, 8754–8794 (2021).

Tiwari, J.-N. et al. Multi-heteroatom-doped carbon from waste-yeast biomass for sustained water splitting. Nat. Sustain. 3, 556–563 (2020).

Borghei, M., Lehtonen, J., Liu, L. & Rojas, O. J. Advanced biomass‐derived electrocatalysts for the oxygen reduction reaction. Adv. Mater. 30, 1703691 (2018).

Qin, J. et al. Biomass-derived single Zn atom catalysts: The multiple roles of single Zn atoms in the oxidative cleavage of C-N bonds. JACS Au 3, 801–812 (2023).

Jiao, C. et al. High-density atomic Fe-N4/C in tubular, biomass‐derived, nitrogen-rich porous carbon as air-electrodes for flexible Zn-air batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2213897 (2023).

Dessalle, A., Quílez-Bermejo, J., Fierro, V., Xu, F. & Celzard, A. Recent progress in the development of efficient biomass-based ORR electrocatalysts. Carbon 203, 237–260 (2023).

Huang, B., Liu, Y. & Xie, Z. Biomass derived 2D carbons via a hydrothermal carbonization method as efficient bifunctional ORR/HER electrocatalysts. J. Mater. Chem. A 5, 23481–23488 (2017).

Gao, S., Li, X., Li, L. & Wei, X. A versatile biomass derived carbon material for oxygen reduction reaction, supercapacitors and oil/water separation. Nano Energy 33, 334–342 (2017).

Gu, J. et al. Synergizing metal-support interactions and spatial confinement boosts dynamics of atomic nickel for hydrogenations. Nat. Nanotechnol. 16, 1141–1149 (2021).

Hao, Q. et al. Nickel dual-atom sites for electrochemical carbon dioxide reduction. Nat. Synth. 1, 719–728 (2022).

Qu, Y. et al. Ambient synthesis of single‐atom catalysts from bulk metal via trapping of atoms by surface dangling bonds. Adv. Mater. 31, 1904496 (2019).

Gai, C. et al. Facile one-pot synthesis of iron nanoparticles immobilized into the porous hydrochar for catalytic decomposition of phenol. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 204, 566–576 (2017).

Hutchison, P., Rice, P. S., Warburton, R. E., Raugei, S. & Hammes-Schiffer, S. Multilevel computational studies reveal the importance of axial ligand for oxygen reduction reaction on Fe-N-C materials. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 16524–16534 (2022).

Wong, L.-W. et al. Site-specific electrical contacts with the two-dimensional materials. Nat. Commun. 11, 3982 (2020).

Wang, Y. et al. High‐efficiency oxygen reduction to hydrogen peroxide catalyzed by nickel single‐atom catalysts with tetradentate N2O2 coordination in a three‐phase flow cell. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 13057–13062 (2020).

Singh, M., Das, D. K. & Kumar, A. Role of atomic substitution in first coordination shell of Fe-N-C single atom catalyst towards oxygen reduction reaction: A theoretical study. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 69, 1149–1156 (2024).

Xie, Q. et al. Nanoscaled and atomic ruthenium electrocatalysts confined inside super‐hydrophilic carbon nanofibers for efficient hydrogen evolution reaction. Small 17, 2102160 (2021).

Meng, H. et al. Iron porphyrin-based cathode catalysts for polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cells: Effect of NH3 and Ar mixtures as pyrolysis gases on catalytic activity and stability. Electrochim. Acta 55, 6450–6461 (2010).

Wang, B. et al. Space‐confined yolk‐shell construction of Fe3O4 nanoparticles inside N‐doped hollow mesoporous carbon spheres as bifunctional electrocatalysts for long‐term rechargeable zinc-air batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 2005834 (2020).

Jin, Z. et al. Understanding the inter-site distance effect in single-atom catalysts for oxygen electroreduction. Nat. Catal. 4, 615–622 (2021).

Wu, Q. et al. Ultra-dense carbon defects as highly active sites for oxygen reduction catalysis. Chem 8, 2715–2733 (2022).

Li, L. et al. Architecting FeNx on high graphitization carbon for high‐performance oxygen reduction by regulating d-band center. Small 19, 2300758 (2023).

Qiao, Z. et al. 3D porous graphitic nanocarbon for enhancing the performance and durability of Pt catalysts: A balance between graphitization and hierarchical porosity. Energy Environ. Sci. 12, 2830–2841 (2019).

Zhu, J. & Mu, S. Defect engineering in carbon‐based electrocatalysts: Insight into intrinsic carbon defects. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 2001097 (2020).

Xie, Q. et al. Controlling sp3 defect density of carbon-based catalysts by defining a limiting space. Chem. Eng. J. 452, 139221 (2023).

Qiu, Y. et al. Generalized reactivity descriptor of defective carbon catalysts for acetylene hydrochlorination: the ratio of sp2:sp3 hybridization. Chem. Commun. 56, 14877–14880 (2020).

Chen, Y. et al. Atomic Fe dispersed on N‐doped carbon hollow nanospheres for high‐efficiency electrocatalytic oxygen reduction. Adv. Mater. 31, 1806312 (2019).

Huang, S. et al. N-, O-and P-doped hollow carbons: Metal-free bifunctional electrocatalysts for hydrogen evolution and oxygen reduction reactions. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 248, 239–248 (2019).

Varnell, J. A. et al. Identification of carbon-encapsulated iron nanoparticles as active species in non-precious metal oxygen reduction catalysts. Nat. Commun. 7, 12582 (2016).

Kramm, U. I., Lefèvre, M., Larouche, N., Schmeisser, D. & Dodelet, J.-P. Correlations between mass activity and physicochemical properties of Fe/N/C catalysts for the ORR in PEM fuel cell via 57Fe Mossbauer spectroscopy and other techniques. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 978–985 (2014).

Zhong, L. et al. 57Fe-Mössbauer spectroscopy and electrochemical activities of graphitic layer encapsulated iron electrocatalysts for the oxygen reduction reaction. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 221, 406–412 (2018).

Isbasar, C. & Hacaloglu, J. Investigation of thermal degradation characteristics of polyamide-6 containing melamine or melamine cyanurate via direct pyrolysis mass spectrometry. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 98, 221–230 (2012).

Zhao, M. et al. A pH-universal ORR catalyst with single-atom iron sites derived from a double-layer MOF for superior flexible quasi-solid-state rechargeable Zn-air batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 14, 6455–6463 (2021).

Zheng, Y. et al. Toward more efficient carbon-based electrocatalysts for hydrogen peroxide synthesis: Roles of cobalt and carbon defects in two-electron ORR catalysis. Nano Lett. 23, 1100–1108 (2023).

Ge, B., Chen, B. & Li, L. A DFT study on the relationship between local microstructure and oxygen reduction reaction activity over Fe-N4 graphene. Mater. Today Commun. 25, 101524 (2020).

Li, J. et al. Thermally driven structure and performance evolution of atomically dispersed FeN4 sites for oxygen reduction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 18971–18980 (2019).

Zong, L. et al. Constructing Fe-N4 sites through anion exchange-mediated transformation of Fe coordination environments in hierarchical carbon support for efficient oxygen reduction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 135, e202309784 (2023).

Wang, Y. et al. Advanced electrocatalysts with single-metal-atom active sites. Chem. Rev. 120, 12217–12314 (2020).

Patniboon, T. & Hansen, H. A. Acid-stable and active M-N-C catalysts for the oxygen reduction reaction: The role of local structure. ACS Catal. 11, 13102–13118 (2021).

Nørskov, J. K. et al. Origin of the overpotential for oxygen reduction at a fuel-cell cathode. J. Phys. Chem. B 108, 17886–17892 (2004).

Dutta, S., Banerjee, P. & Pati, S. K. Computational insight into TM-Nx embedded graphene bifunctional electrocatalysts for oxygen evolution and reduction reactions. ACS Phys. Chem. Au 2, 305–315 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We thank to the financial support of the Natural Science Basic Research Program of Shaanxi (Program No. 2024JC-YBQN-0113, Q.X.), Anhui Provincial Natural Science Foundation (Program No. 2308085J16, M.L.), Tianshan Innovation Team Program of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (Grant No. 2020D14038, Q.J.), Tianshan Talent Training Program of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region of China (Program No. 2022TSYCJU0004, Q.J.), the Natural Science Foundation of China (Program No. 22178284, Y.S.) and the Joint Funds of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Program No. U24A20553, Y.S.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.G., M.P., Z.W., and M.L. conducted the experiments and wrote the manuscript; M.P. and Y.Y. performed the DFT calculations and analysed the results; Q.X., H.F., and L.L. performed part of the characterizations; Z.W. and M.L. conceived of the presented idea and supervised the findings of this work; Q.J. and Y.S. supervised the DFT calculations of this work; all authors discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Guo, W., Pan, M., Xie, Q. et al. Achieving pH-universal oxygen electrolysis via synergistic density and coordination tuning over biomass-derived Fe single-atom catalyst. Nat Commun 16, 2920 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-58297-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-58297-1