Abstract

Inaccurate chromosome segregation can lead to the formation of aneuploid cells that harbor an imbalanced complement of chromosomes. Several fungal species are not only able to tolerate the detrimental effects of aneuploidy but can use it to adapt to environmental pressures. The fungal pathobiont Candida albicans frequently acquires supernumerary chromosomes that enable growth in the presence of antifungal drugs or in specific host niches, yet the transcriptional changes associated with aneuploidy are not globally defined. Here, a karyotypically diverse set of C. albicans strains revealed that expression generally correlated with gene copy number regardless of the strain karyotype. Unexpectedly, aneuploid strains shared a characteristic transcriptional profile that was distinct from a generalized environmental stress response previously defined in aneuploid yeast cells. This aneuploid transcriptional response led to altered growth and oxidative balances relative to euploid control strains. The increased expression of reactive oxygen species (ROS) mitigating enzymes in aneuploid cells reduced the levels of ROS but caused an acute sensitivity to both internal and external sources of oxidative stress. Taken together, our work demonstrates common transcriptional and phenotypic features of aneuploid C. albicans cells with consequences for infection of different host niches and susceptibility to environmental stimuli.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Defects in cell division can lead to mis-segregation of chromosomes during mitosis and the formation of aneuploid cells which contain an uneven complement of chromosomes. Aneuploidy is often tied to general fitness defects in single-celled eukaryotes and can result in spontaneous abortion or tumor production in multi-cellular species1,2,3. These detrimental effects are directly linked to genetic dysregulation via DNA copy number changes. In general, genes in amplified regions of aneuploid cells exhibit increased expression in accordance with their dosage4, so that a trisomic chromosome in a diploid species displays a 50% increase in gene expression. However, mechanisms to compensate for increased gene dosage can operate in human cancers due, in part, to transcriptional suppression via DNA methylation5,6,7, and similar compensatory mechanisms operate on a subset of genes on supernumerary chromosomes in the model yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae8. Genetic imbalance can also produce generalized stress responses in addition to gene-specific responses such as those observed in oncogenic transformation9,10,11. Studies in S. cerevisiae have defined a transcriptional profile common to aneuploid strains that is similar to the environmental stress response (ESR)1. This profile is also observed in other eukaryotic species and can result in increased proteotoxic stress due to protein misfolding and aggregate formation, metabolic defects, and altered growth4,12,13,14,15,16.

Yeast species have served as an excellent model for investigating aneuploidy because of their ability to propagate stably across different ploidy states and to tolerate the presence of supernumerary chromosomes17. Aneuploidy in many yeast species can arise either through errors during meiosis or unequal chromosome segregation during mitosis18,19. In the pathobiont Candida albicans, ~5% of a collection of 182 isolates was found to contain supernumerary chromosomes20, and this percentage was higher in other clinical collections, possibly due to strains having been exposed to antifungal drugs21,22. Indeed, exposure to the azole class of antifungal drugs can decouple nuclear division and cell separation to produce karyotypically diverse cell populations23. Additionally, the parasexual mating cycle in C. albicans frequently generates aneuploid cells, as mating products undergo an uncoordinated process of ploidy reduction termed concerted chromosome loss (CCL) to produce a wide variety of aneuploid progeny24,25,26,27. In contrast to other yeast species, it is unclear how copy number and gene expression are associated in C. albicans. Initial studies suggested chromosome copy number may influence gene expression28,29, while more recent investigations indicated potential compensation for imbalanced genes but relied on a relatively small number of strains and focused on single chromosomes30,31.

Carriage of supernumerary chromosomes has been shown to improve C. albicans fitness under specific conditions. For example, amplification of chromosome 5 (Chr5) genes enables resistance to azole drugs by increasing expression of the ERG11 drug target29,32, while an extra copy of Chr7 provides a fitness advantage for gastrointestinal colonization through elevated NRG1 expression33,34. Indeed, the relatively few fitness benefits associated with aneuploid strains have been linked to specific imbalanced chromosomes35,36,37,38. However, most aneuploid C. albicans strains exhibit a fitness defect when grown under a variety of in vitro conditions, consistent with there being a significant cost associated with aneuploidy35. The fitness defects associated with aneuploids are thought to contribute to their instability and the convergence of aneuploid C. albicans strains towards euploidy during repeated in vitro passaging26. Yet, the frequent isolation of aneuploid C. albicans isolates from the clinic suggests that these cells also display traits that are either beneficial or lack substantial fitness costs to colonization or propagation in certain human host environments.

In this study, we characterized the transcriptional profiles and phenotypes of a diverse set of aneuploid C. albicans strains harboring different supernumerary chromosomes. These experiments used the C. albicans parasexual program to generate aneuploid derivatives of SC5314, the genome reference isolate of the species. We show that transcript abundance strongly correlates with gene copy number on imbalanced C. albicans chromosomes. Moreover, we uncover a shared aneuploid stress response (ASR) in C. albicans that is independent of strain karyotype. The ASR confers unique phenotypes to aneuploid cells that distinguishes them from their euploid counterparts and is not conserved with transcriptional responses to other environmental stresses. Together, these results demonstrate both shared and unique transcriptional responses among aneuploid C. albicans strains with consequences for adaptation to different host niches.

Results

C. albicans gene expression correlates with relative copy number

Diploid C. albicans SC5314 strains were mated to generate tetraploid products that were then induced to undergo CCL by incubation on pre-sporulation medium at 37oC for seven days24,27,39. Viable parasexual progeny were assessed for ploidy reduction by growth on 2-deoxygalactose (2-DOG) medium, which selects for loss of the two Chr1 encoded GAL1 copies from the tetraploid mating product. 2-DOG-resistant progeny were subsequently screened for DNA content by flow cytometry to identify isolates that had slightly greater than diploid DNA content. In total, 44 parasexual progeny screened by flow cytometry were selected for further genomic and transcriptomic analysis (Fig. 1a).

a Schematic depicting growth of the strains used in this study for transcriptional and DNA profiling. Progeny cultures were grown in YPD medium in logarithmic phase to 2 × 107 cells/mL were split into two aliquots, one for selective genotyping to define the karyotype and the other for expression profiling by RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq). Created in BioRender. Gusa, A. (2025) https://BioRender.com/i95e847. b Karyotypes of parasexual progeny were determined and depicted as a heat map where the block intensity indicates the number of strains with each aneuploid karyotype. c The log2 ratio of RNA (red) and DNA (black) counts relative to the diploid control were fitted with a LOESS method first degree local polynomial regression for a diploid progeny and nine representative aneuploid strains. Data is plotted based on its chromosomal position and the eight chromosomes are plotted separately. d The median expression value for each chromosome was normalized relative to the diploid control. Expression values were then separated by the DNA copy number as either disomic (open) or trisomic (maroon) and plotted for all 36 aneuploid strains. Significance was determined by Wilcoxon test. *** denotes p < 2E-16. e The expression of all genes (left) or a subset of 49 genes in stoichiometric complexes (right) that were found on trisomic chromosomes was normalized to the average expression on disomic chromosomes in aneuploid strains. Expression is plotted as a histogram of the log2 ratio of relative expression. The dashed line indicates a 1.5-fold increase in expression.

Selective genotyping by double-digest restriction site associated DNA sequencing (ddRAD-Seq) was used to define C. albicans strain karyotypes based on comparative read depth for each of the eight chromosomes. Sequenced strains carried a range of karyotypes with 19 strains harboring a single trisomic chromosome and others containing up to four trisomic chromosomes (Supplementary Data 1). Three strains were karyotypically complex and subsequently removed from the initial study. For example, one mostly disomic strain contained four copies of Chr5 and another strain contained a mixture of stably inherited monosomic and trisomic chromosomes (Figure S1A). An additional single strain was disomic for all eight chromosomes and removed from downstream analysis.

Ultimately, the 36 strains included in this study contained trisomies for each of seven of the eight C. albicans chromosomes (Fig. 1b). No strain contained trisomy of Chr1 alone or in combination with other chromosomes, likely due to selection for loss of the GAL1 gene which is located on this chromosome24,39, or trisomy for Chr7 alone. Seventeen of 36 strains carried trisomies for multiple chromosomes (Fig. 1b, Supplementary Data 1). Recovered aneuploid strains were not biased towards containing smaller chromosomes or less total imbalanced DNA in this strain set (R2 = 0.107, F(1, 14) = 2.792, p = 0.117), suggesting that identification of aneuploid strains did not exclude larger chromosomes or complex karyotypes from being recovered.

To define how copy number changes affect gene expression, DNA and transcript abundance values were normalized to the diploid parental strain and plotted for all eight chromosomes. A clear association emerged between increased DNA copy number due to chromosome trisomy and corresponding increases in average gene expression (Fig. 1c, S2). Across all 36 strains, trisomies displayed a median 1.46-fold increase in gene expression compared to disomic chromosomes in the same strains (Fig. 1d, Wilcoxon; W = 43, p < 2.2E-16). The distribution of expression values around the median was not Gaussian but contained a similar number of genes outside the 95% confidence interval (135 and 80 on the left and right tails, respectively). Validation of this association using DNA and gene expression data from three aneuploid clinical isolates (19 F, P78042, and P60002) showed remarkably similar trends, with gene expression increasing in accordance with amplified chromosomal regions, including segmental amplifications (Figure S3). Together, this data strongly supports a linear relationship between C. albicans gene copy number and average gene expression that is independent of a specific karyotype or genetic background.

Imbalanced gene expression of protein subunits in heterooligomeric complexes from chromosomes with different copy numbers can lead to the formation of protein aggregates and disrupted protein homeostasis40,41. Expression of 49 genes from nine separate complexes on trisomic chromosomes remained elevated relative to their disomic counterparts and mirrored the general expression trends on amplified chromosomes (Fig. 1e, S4, Wilcoxon; W = 95924, p = 0.2292). Thus, no clear gene dosage compensatory mechanism exists to attenuate gene expression of individual subunits in stoichiometric complexes.

Aneuploidy produces a unique transcriptional response in C. albicans

Chromosomal imbalance generates a shared transcriptional stress response across eukaryotes, including yeast, plants, and humans1,4,42,43. To determine if an aneuploid-specific transcriptional response also exists in C. albicans, we separated each of the eight C. albicans chromosomes and compared the expression profiles of genes on disomic chromosomes between euploid and aneuploid strains. Note that only disomic chromosomes were examined in aneuploid isolates to remove the contribution of trisomic chromosomes to differences in gene expression, and each chromosome was analyzed individually (Fig. 2a). This approach compared gene expression of five diploid replicates to expression profiles of aneuploid strains that were disomic for the selected chromosome (range of 42 replicates for Chr4 to 72 replicates for Chr1).

a Aneuploid stress responses were determined for each chromosome individually. Diploid control strains were compared to the expression across all aneuploid strains except those trisomic for that chromosome. Created in BioRender. Gusa, A. (2025) https://BioRender.com/f13d484. b Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between aneuploid strains and the diploid control set were determined as greater than a 2-fold change and adjusted p value < 0.05 by Fisher’s Exact Test. These genes (N = 557) are plotted by transcript abundance (x-axis) and change in expression in aneuploid strains relative to the diploid strains (y-axis) as grey dots. Heat shock proteins (HSPs) are marked as black dots. c Heatmaps display expression values for differentially expressed genes on each chromosome. Strains are ordered from left to right by the amount of excess DNA in the aneuploid strain. Gene expression is shown only for strains disomic for that chromosome. d Gene Ontology processes with statistical enrichment in the aneuploidy stress response are shown with the number of contributing genes indicated (Fisher’s Exact test). e Transcriptional profiling of C. albicans in the same SC5314 genetic background was analyzed identically to the aneuploid stress response from Bruno et al.46. Differentially expressed genes (2-fold change and q < 0.05) are displayed as yellow and magenta for increased and decreased transcript abundance, respectively. Genes without differential expression in any condition were excluded from the plot. Clustering was done using Manhattan distances and the number of DEGs for each condition is shown in parenthesis.

Aneuploid strains showed altered expression of 566 genes (q ≤ 0.05 and 2-fold change) on disomic chromosomes. Most of these genes showed increased expression in the aneuploid strains (479 of 566 genes), with the remaining 87 genes decreasing in expression (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Data 2). Notably, heat shock proteins (HSPs) displayed some of the largest increases in expression (e.g., HSP21 - 600x increase, Fig. 2b), consistent with prominent roles in aneuploidy responses in other eukaryotes1. Apart from heat shock proteins, the top ten genes with the highest fold change between aneuploid and euploid strains included two genes involved in cell wall architecture (RBT5 and RBR1) and five members of the telomere-associated (TLO) gene family, a paralogous family of transcriptional regulators in the C. albicans subtelomeres that function as interchangeable subunits of the Mediator complex44. Surveys of other expanded gene families identified that seven of ten members of the secreted serine aspartyl proteases (SAPs) associated with host cell destruction also increased in expression in aneuploid cells. Among the ten genes with the largest fold change, two genes were related to C. albicans mating responses (FAR1 and CAG1). Increased expression of mating genes could be linked to homozygosis of the Mating Type-Like (MTL) locus in the aneuploid parasexual progeny during CCL. Indeed, six of ten assayed progeny strains had lost heterozygosity at the MTL locus (Figure S5A), which likely underlies increased mating gene expression. Diploid control strains consistently expressed mating-responsive genes at low levels compared to aneuploid isolates that could have 100x greater expression (Figure S5B), even when heterozygous at the MTL locus (e.g., FAR1 in strain D1). Nine genes differentially expressed in aneuploid cells are known regulatory targets of the a1/alpha2 heterodimer at the MTL locus45 and were removed from further analysis to remove the effects of MTL configuration, leaving 557 genes differentially expressed in aneuploid strains.

To determine how well conserved the aneuploid stress response was in each aneuploid strain, differential gene expression was performed between the diploid control and each aneuploid strain individually. Genes with significantly different expression ( ≥ 2-fold change, q-value ≤ 0.05) on disomic chromosomes were compared to the 557 genes that define the ASR. Differentially expressed genes in each aneuploid strain overlapped with the ASR by 34.1% to 70.1% (Figure S6). Furthermore, gene expression changes defining the ASR generally remained the same for cells with different amounts of imbalanced DNA (Fig. 2c),

The set of 557 genes whose expression was linked to aneuploidy in C. albicans clustered into gene ontology (GO) categories related to growth (e.g., carbohydrate transport, cell redox homeostasis), adhesion, and oxidative stress (Fig. 2d). These gene products are overrepresented in the cell wall and other external structures (Supplementary Data 3). Example genes include the aforementioned SAP genes as well as loci encoding GPI-anchored proteins such as RBT5 and RBR1. Interestingly, genes associated with GO terms describing sugar transport had reduced expression in the aneuploid strains, including five members of the high-affinity glucose transporter (HGT) gene family.

The aneuploid stress response described here was clearly distinguishable from other C. albicans stress responses. Transcriptional profiles of C. albicans yeast cells grown in oxidative stress (0.5 or 5 mM H2O2), nitrosative stress (1 mM DPTA-NONOate), hyphae-inducing conditions (YPD + 10% fetal calf serum), and pH stress (pH 4 or 8 in M199 medium) from Bruno et al.46 were compared to the ASR. Interestingly, most of these stress conditions elicited broader transcriptional responses inclusive of more genes than that of the aneuploid-specific response (Fig. 2e, S7A, Supplementary Data 4). Differential expression of only nine genes was common to all six stress conditions, and 103 genes were unique to the ASR (Figure S7). Together, this data indicates the lack of a shared response in C. albicans to different stresses and establishes that the aneuploid stress response is distinct from that of environmental stress responses.

The aneuploid stress response induces redox imbalance and oxidative sensitivity

The transcriptional profile of C. albicans aneuploid strains suggested that phenotypic differences may exist relative to euploid strains. Previously, the only phenotype ascribed broadly to C. albicans aneuploid cells was a reduced growth rate in rich media conditions35. Ten aneuploid isolates that harbored a range of supernumerary chromosomes (six strains containing a single trisomic chromosome for each of Chr2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and R and four strains containing multiple trisomic chromosomes) were chosen for phenotypic analysis. Consistent with the study by Yang et al., all ten aneuploid isolates grew more slowly than the diploid SC5314 parental strain in YPD medium at 30 °C (Fig. 3). This slower growth rate was due to increased doubling times and not a defect in entering logarithmic growth (Fig. 3a).

a Growth curves in liquid YPD at 30 °C during a 21-hour window are shown for 10 aneuploid strains (in blue), the diploid control (in dark grey), and tetraploid control (in light grey). OD600 measurements are shown in 15-minute intervals with standard deviations. Data are plotted as the mean with error bars indicating the standard deviation. N = 4. b The average doubling time during exponential growth was calculated for all strains and plotted as the mean and interquartile ranges (IQR) with whiskers extending to 1.5 × IQR. Data points extending beyond 1.5 × IQR are plotted individually. Strains are ordered from left to right by the amount of excess DNA in the aneuploid strain. N = 4. Significance was determined by two-sided Student’s t-test relative to the diploid strain without multiple comparison adjustments. * denotes p < 0.05. ** denotes p < 0.01. *** denotes p < 0.001.

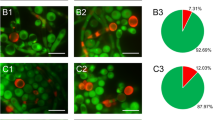

Reduced growth rates and altered metabolic profiles in aneuploid S. cerevisiae strains have been linked to redox imbalance and increased levels of internal ROS11. Gene expression of the aneuploid C. albicans strains indicated major shifts in cellular homeostasis through changes to reduction-oxidation reactions and oxidative stress responses. To determine if redox imbalance is also a general feature of aneuploid C. albicans strains, we compared the basal and induced oxidative states of diploid and aneuploid cells using the molecular indicator 2’,7’-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (H2DCF-DA). Actively growing diploid cells contained ~4-fold greater levels of ROS than quiescent cells taken directly from saturated overnight cultures. Surprisingly, nine of 10 aneuploid strains contained lower levels of ROS compared to the diploid parent, with most strains mirroring the more metabolically quiescent saturated cultures (Fig. 4a, b). The increased expression of the positive regulator CAP1 (2.3-fold among aneuploid strains on average) may contribute to the reduced ROS levels (Supplementary Data 2). CAP1 activates the expression of genes as part of the oxidative stress response, including superoxide dismutases (e.g., SOD4, SOD6), thioredoxins (e.g., PRX1, TRX2), peroxidases (e.g., CCP1, DOT5, GPX3), and oxidoreductases (e.g., CIP1, OYE32, PST2) that can quench ROS.

a Logarithmic phase C. albicans cells were stained with 476 μM H2DCF-DA for 30 minutes and imaged by differential interference contrast (DIC) and fluorescence microscopy. Scale bar = 5 µm. b Quantification of H2DCF-DA fluorescence is plotted as the mean and interquartile ranges (IQR) with whiskers extending to 1.5 × IQR. Data points extending beyond 1.5 × IQR are plotted individually. N = 3. Significance was determined by Student’s t-test relative to the diploid control without multiple comparison correction, and all data are plotted as the mean and interquartile ranges. c Schematic representing the origin of reactive oxygen species (ROS) from either exogenous or endogenous sources. d Strains were struck heavily onto high glucose pre-sporulation medium for 4 days and allowed to grow at 37 °C. Cells were suspended in a 1:3000 dilution of propidium iodide (PI) and the fraction of PI positive cells determined by flow cytometry of 50,000 events. Significance was determined by the Wilcoxon test, and data was plotted as the mean with the error bars indicating the standard deviation. N = 9. e A polynomial curve was fit to the growth curve over 36 hours. Exogenous ROS sensitivity was determined by comparing the time taken to reach 0.4 OD600 between cultures grown in 0 mM and 2.5 mM H2O2, and (f) plotted for the indicated strains. Significance was determined by Wilcoxon test, and data plotted as the mean with error bars indicating the standard deviation. N = 4. g Cells from the diploid and ten aneuploid strains were incubated for 30 minutes in liquid YPD supplemented with 0, 40, or 80 mM H2O2. Ten-fold dilutions were spotted as 5 μL onto YPD solid agar medium and imaged after 24 hours. h Significance was determined by Wilcoxon test of the 40 mM:0 mM H2O2 second spot dilution pixel intensity between aneuploid strains and the diploid control. N = 3 except for diploid where N = 6. Data is plotted with the mean and error bars that indicate the standard deviation. Aneuploid strains are shown in blue and the diploid and tetraploid controls in dark and light grey, respectively. * denotes p < 0.05. ** denotes p < 0.01. *** denotes p < 0.001.

Although the basal levels of intracellular ROS in aneuploid C. albicans cells is inverted compared to other eukaryotic species11,47,48, we posited that increased expression of ROS mitigating enzymes could leave aneuploid cells more sensitive to additional oxidative stress from endogenous and exogenous sources (Fig. 4c). Growth on glucose-rich S. cerevisiae pre-sporulation (pre-spo) medium generates high levels of ROS byproducts in tetraploid C. albicans cells that leads to nuclear fragmentation and cell death49. Growth on pre-spo increased the fraction of PI-positive cells for eight of ten aneuploid strains (Fig. 4d). Increased sensitivity did not correlate with the amount of imbalanced DNA. Surprisingly, cells containing a Chr2 trisomy alone or in combination with Chr6 were hypersusceptible to pre-spo induced death with nearly all cells staining PI-positive. It is currently unclear what loci on Chr2 may contribute to this drastically increased susceptibility to endogenous ROS.

Aneuploid strains also proved to be more sensitive to exogenous sources of oxidative stress than euploid strains. Growth of C. albicans in low doses of H2O2 can delay or slow growth without being lethal to the majority of cells in the population (Fig. 4e)50. Consequently, the addition of 2.5 mM H2O2 significantly delayed the growth of eight out of ten aneuploid strains compared to the diploid control when normalized to growth in 0 mM H2O2 (Fig. 4f), while one aneuploid strain (trisomic for Chr5, 7) showed an increased growth rate in H2O2. Aneuploid and diploid control strains were also exposed to an acute pulse of 40 or 80 mM H2O2 and allowed to grow for 24 hours in the absence of ROS prior to imaging. In the absence of H2O2 exposure, an equivalent number of colonies formed for aneuploid isolates compared to the diploid control (Fig. 4g). Following exposure to acute levels of 40 and 80 mM H2O2, less growth was observed for aneuploid strains than for the euploid control. Thus, aneuploid strains, with the exception of TriR, had a reduced pixel intensity ratio when comparing growth at 0 mM and 40 mM H2O2 (Fig. 4h), indicating increased susceptibility of aneuploid strains to short bursts of oxidative stress. No clear trends in increased sensitivity to endogenous and exogenous sources of ROS based on particular chromosome trisomies emerged, suggesting a complex phenotype influenced both by the transcriptional response to aneuploidy and specific loci on imbalanced chromosomes. Together, altered redox balances and oxidative stress responses appear to be general features of aneuploid C. albicans cells that decrease intracellular ROS and can significantly increase sensitivity to external sources of oxidative stress.

Aneuploidy increases flocculation and can promote fluconazole survival

Gene ontology analysis identified increased expression of genes associated with adhesion in aneuploid cells relative to the diploid control. Cell-cell adhesion can contribute to differences in C. albicans flocculation and cell settling that are readily observable among some aneuploid isolates in saturated liquid cultures left undisturbed (Figure S8A). Four of the ten aneuploid strains flocculated more rapidly in YPD compared to the diploid parental strain (Figure S8B). Among strains containing a single trisomic chromosome, those with Chr2, Chr5, and ChrR trisomies settled more rapidly, whereas strains with Chr3, Chr4, and Chr6 trisomies did not. Aneuploid cells were similar in size to the diploid control cells, and thus cell size differences are unlikely to contribute to differences in the dynamics of settling (Figure S8C). Cultures of aneuploid strains with strong flocculation phenotypes contained cells that frequently clumped together, which is likely responsible for the faster settling. No correlation existed between gene expression of loci annotated for biological adhesion and the degree of flocculation observed. However, the two strains that displayed the strongest cell aggregation and settling phenotypes contained a Chr2 trisomy (Figure S8B, C).

Certain forms of aneuploidy are known to alter sensitivity to the commonly used azole class of antifungal drugs29. Fluconazole resistance increased in strains trisomic for Chr5, which encodes the ERG11 azole drug target, compared to the diploid control (Students t-test; t(5) = 5.37, p = 0.021, Figure S9A,B). Trisomy of ChrR has also recently been shown to increase tolerance to fluconazole51. The set of 10 aneuploid strains evaluated here showed both increased and decreased fluconazole tolerance. Most notably, a trisomy of ChrR produced significantly increased tolerance to fluconazole with colonies occupying the full area of the plate up to the fluconazole disk (Welch’s t-test; t(5) = -4.22, p = 0.019, Figure S9A,C), consistent with the report of Yang et al.51.

Spontaneous and complex aneuploid cells share ASR features

Our collection of parasexual progeny did not include cells containing only a trisomy of Chr7. However, a previous study obtained SC5314 cells that harbored a trisomy for either the A or B homolog of Chr735. We therefore evaluated the transcriptional profile of these aneuploid strains which were obtained by an independent approach from the parasexual mating cycle used to produce the aneuploid strains in the current study. Strains trisomic for Chr7 were transcriptionally profiled under the same conditions as the set of aneuploid parasexual progeny. As with all other aneuploid strains, relative expression of genes on trisomic copies of Chr7 mirrored their gene dosage (Figure S10A). Moreover, gene expression on disomic chromosomes in strains with a Chr7 trisomy was significantly associated with the ASR expression profile, χ2 (1, N = 538) = 43.5, p = 4.18E-11 (Figure S6). The overlap with the aneuploid stress response is lower in Chr7 trisomic strains than in other aneuploid strains and is due, in part, to the lower number of differentially expressed genes on disomic chromosomes in these trisomic strains (371 and 479 for Chr7 AAB and ABB, respectively).

To determine if the effects of aneuploidy were observed in strains with more complex karyotypes, we also evaluated gene expression in a strain that was tetrasomic for Chr4 and one strain that harbored both monosomic (Chr2,7) and trisomic (Chr4,6) chromosomes (Figure S1A). The strain tetrasomic for Chr5 shared 57.5% of differentially expressed genes with the ASR (on disomic chromosomes), and the highly complex aneuploid strain with monosomic and trisomic chromosomes showed an overlap with the ASR of 43.1% (Figure S6). Visualization of differentially expressed genes on disomic chromosomes reflected the gene expression patterns of parasexual progeny containing trisomic chromosomes (Figure S1B), suggesting that expression of ASR genes is generally associated with aneuploidy.

Strains containing a spontaneous Chr7 trisomy or other complex karyotypes displayed phenotypes consistent with our set of parasexual aneuploid strains. Thus, growth on pre-spo medium induced significantly elevated levels of cell death for both the Chr7 trisomic strains and strains with complex karyotypes compared to the diploid control (Figure S1C, S10B). This was particularly true for the strain carrying a combination of trisomic and monosomic chromosomes, in which 93.8% of cells were PI-positive after four days of growth on pre-spo medium at 37 °C. In addition, these aneuploid strains were susceptible to an external source of reactive oxygen species. Exposure to 40 mM or 80 mM H2O2 for 30 minutes significantly reduced cell viability of the assayed aneuploids compared to the diploid control strain (Figure S1D,E, S10C,D). Thus, these strains show overlapping transcriptional and phenotypic characteristics with the parasexual trisomic strains used to define the ASR.

Tetraploid cells do not exhibit the aneuploid stress response

Aneuploid strains used to define the aneuploid stress response have increased DNA content above diploid. To determine if the aneuploid stress response is unique to cells with imbalanced karyotypes or a general consequence of increased ploidy, we compared the transcriptional response of SC5314 diploid and tetraploid cells when grown under identical culture conditions to the aneuploid strains (logarithmic phase growth in YPD at 30 °C). Tetraploid cells differentially expressed 524 genes compared to isogenic diploid cells (q \(\le\) 0.05, 2-fold change; Supplementary Data 2). Unlike the aneuploid stress response, roughly equal numbers of genes were increased and decreased in expression between diploid and tetraploid cells. Differentially expressed genes were enriched for a narrow subset of processes that centered on core pathways of transcription and translation such as tRNA processing and modification, RNA regulation, and ribosome biogenesis (Fig. 5a, Supplementary Data 3). These terms are fundamentally distinct from gene ontologies identified in the aneuploid stress response.

a Gene Ontology processes enriched among the 524 differentially expressed genes (2-fold change and q < 0.05) comparing isogenic diploid and tetraploid strains is shown with the number of contributing genes indicated. b Comparison of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) with transcript abundance either decreased (left, in purple) or increased (right, in yellow) in the aneuploid strain set or tetraploid mating products relative to the diploid background strains. Expression of DEGs in common is displayed as a heatmap and ordered by increasing change in the aneuploid stress response.

To determine the extent of similarity in the aneuploid stress response and tetraploid expression profile, we interrogated the extent of overlap among differentially expressed genes between aneuploid and tetraploid cells. Significant overlap existed for both increased and decreased transcript abundance between these strains when compared to the diploid parental strains, χ2 (1, N = 6461) = 120.13, p < 2.2E-16; increased, (1, N = 6461) = 139.97, p < 2.2E-16; decreased (Fig. 5b). However, performing a rank test of genes differentially expressed in both aneuploid and tetraploid cells revealed a lack of similarly ordered gene expression between the datasets (Wilcoxon; upregulated, W = 135, p = 1.21E-4 and downregulated, W = 2065, p = 5.38E-4). Furthermore, genes in the aneuploid stress response with connections to affiliated phenotypes (e.g., HSP, SAP, AOX genes) were not differentially expressed between diploid and tetraploid cells. This strongly supports the identification of an aneuploid-specific response to imbalanced karyotypes in C. albicans that differs from that due to increased DNA content alone.

Discussion

Aneuploidy has well-defined roles in promoting cellular heterogeneity and phenotypic variation that extends from microbial populations to cancer. C. albicans and other fungi have served as model organisms for examining the consequences of aneuploidy due to their ability to tolerate highly diverse and complex aneuploid karyotypes. Here, we generated and analyzed a set of aneuploid C. albicans strains to determine relationships between aneuploidy, gene expression, and its affiliated phenotypes. We show that aneuploid strains share several features, including: a) increased expression of genes on imbalanced chromosomes or chromosomal regions in line with gene copy number, b) a lack of transcriptional compensation for proteins in stoichiometric complexes, c) a shared aneuploid stress response (ASR) independent of the aneuploid configuration, d) increased expression of genes associated with specific cellular processes, and e) concomitant phenotypic changes arising from these expression changes. We highlight that the C. albicans ASR has multiple features that distinguish it from the environmental stress response associated with aneuploidy in other eukaryotes. Altogether, this work defines common attributes held by aneuploid strains of C. albicans and provides insight into how aneuploidy may be uniquely tolerated to promote phenotypic heterogeneity and survival in host niches.

The C. albicans aneuploid stress response has distinct features

Aneuploidy alters some of the same responses in C. albicans but often in unique ways to that described in other eukaryotes, including altered metabolism, oxidative stress, and protein turnover4,15. A hallmark feature of aneuploidy in most investigated eukaryotes is increased gene expression of the protein turnover machinery as part of the unfolded protein response (UPR)52,53,54. Our data lacks clear transcriptional induction of pathways involved in ubiquitin-mediated protein turnover, proteosome activity, or organellar degradation in C. albicans aneuploid cells. This may represent a significant deviation from the conserved environmental stress response (ESR) observed in aneuploid cells from other species. Accordingly, the transcriptional response of C. albicans to a variety of environmental stresses did not resemble the aneuploid stress response. Alternatively, excess protein produced from imbalanced chromosomes in C. albicans may be acted upon by heat shock proteins and not the UPR. Heat shock proteins (HSPs), such as HSP104, disassemble protein aggregates that form in aneuploid S. cerevisiae cells53. HSP104 and multiple other HSPs are also transcriptionally activated in C. albicans aneuploid strains and may serve similar functions that circumvent the requirement for the UPR.

Previously, most aneuploid C. albicans strains were shown to grow slower than euploid strains under optimal growth conditions, independent of the karyotype35. Decreased expression of glucose transporters (e.g., HGT2, HGT8, HGT20, etc.,) in aneuploid C. albicans cells (Supplementary Data 2, 3) provides a potential molecular explanation for the decreased growth rates observed in aneuploid C. albicans cells. We did not observe any transcriptional evidence of cell cycle defects in aneuploid C. albicans cells that would result in slower rates of cell division and growth as was reported in S. cerevisiae and human cells1,47,55. The volume of C. albicans aneuploid cells was also not significantly greater than diploid cells as was found in aneuploid S. cerevisiae cells43, suggesting that reduced growth is unlikely due to osmolarity or surface:volume ratio changes that increase transport times throughout the cell or increase the requirement for cellular building blocks56,57.

Aneuploid cells in S. cerevisiae and other species contain elevated ROS levels that are likely due to increased metabolic turnover of excess protein4,11,47. Although aneuploid C. albicans cells upregulated transcriptional activators of oxidative stress and their corresponding downstream effectors (e.g., SOD4, SOD6), ROS levels were unexpectedly lower in aneuploid cells relative to euploid cells. Decreased ROS levels in aneuploid C. albicans cells could reflect a combination of reduced metabolic activity and increased expression of genes that eliminate ROS. Increased ROS-mitigating enzyme expression may compromise the ability for aneuploid cells to mitigate oxidative damage and/or activate repair pathways in response to additional sources of ROS, either endogenously produced through metabolism (e.g., during growth on pre-spo medium) or from exogenous sources (e.g., hydrogen peroxide). The oxidative stress sensitivity observed in C. albicans aneuploid cells is consistent with aneuploid phenotypes in other species and likely stems from the inability to repair oxidative DNA damage following intense ROS bursts47.

Altered host-microbe processes among aneuploid strains

The first step in either C. albicans colonization or dissemination in the host is often adhesion to host tissues58,59. Four of ten aneuploid strains analyzed in this study displayed increased aggregation and flocculation that could contribute to altered propensities to colonize host niches or to changes in biofilm structures. Increased expression of multiple architecturally distinct groups of adhesins (e.g., those encoded by ALS and IFF genes) may facilitate these phenotypes and was characteristic of the aneuploid stress response.

Detection by the host relies heavily on the recognition of fungal cell surface molecules that can initiate inflammatory responses leading to fungal clearance. Unexpectedly, genetic signatures of aneuploid cells were enriched for cell wall components. GPI-anchored proteins constituted a significant portion of differentially expressed genes (e.g., HYR1, CHT2, and PGA family members) that are associated with cell wall remodeling during interconversion between the yeast and hyphal forms60,61,62. All aneuploid strains grew as yeast cells under the conditions used for transcriptional profiling, suggesting that dysregulation of state-specific gene expression occurs in aneuploid cells and can lead to increased expression of hyphae-induced genes. Further support for a dysregulated cell wall profile is found in the upregulation of seven members of the serine aspartyl protease (SAP) family that have increased expression in hyphal cells63, and may also contribute to the increased adhesive properties of aneuploid strains.

Clearance of C. albicans by the innate immune response relies heavily on the production of ROS to eliminate fungal cells, either when phagocytosed or via extracellular ROS64. The susceptibility of aneuploid strains to ROS discussed above suggests that these cells would be more easily cleared by the immune response. Relatively little work has assessed the virulence properties of aneuploid cells in host systems, so it remains unclear how the increased dosage of specific chromosomes may alter the dynamics of infection in environments with elevated ROS levels.

Investigations of aneuploidy in C. albicans have largely focused on the trade-off between fitness defects during in vitro growth and fitness advantages to specific environmental stresses such as drug exposure36,65. The ASR involved fewer gene expression changes than that to canonical stress conditions. This may indicate that aneuploidy has a relatively limited impact on the activation of general stress pathways that would otherwise impose a significant fitness cost and favor the propagation of euploid derivatives. The lack of a core stress response in C. albicans may enable cells to cope with stress by activating the minimum number of genes to neutralize fitness detriments66,67. Thus, a limited impact on overall fitness by aneuploidy may underlie the karyotypic flexibility ascribed to C. albicans and its ability to tolerate aneuploidy. In addition, fitness advantages conferred by increased copies of specific chromosomes in the host (e.g., Chr6 in the oral cavity, Chr7 in the gut) could overcome any general fitness defects associated with aneuploidy33,34,68.

Allele-specific expression is not likely to significantly impact the transcriptional features of aneuploid cells described here. In SC5314, 139 genes (of 3,285 included in the analysis, 4.2%) were found to display allele-specific expression and were enriched for mitochondrial proteins69. This small number of genes is unlikely to skew the expression signature of imbalanced chromosomes across aneuploid strains. Additionally, ASR genes are not enriched for mitochondrial functions. However, increased dosage of alleles containing functionally relevant variants can produce novel C. albicans phenotypes70,71, and could similarly impact aneuploid phenotypes in karyotypically identical strains.

Taken together, our results show that C. albicans aneuploid cells express most genes in line with their copy number, and that a shared transcriptional response (the ASR) arises when supernumerary chromosomes are present. The activation of a limited transcriptional stress response in C. albicans may allow aneuploidy to function as a bet-hedging strategy in adapting to new niches or environmental conditions. Further understanding how aneuploidy alters fundamental aspects of cell physiology, the relative stability of supernumerary chromosomes, and whether compensation of imbalanced genes occurs at the protein level, continue to be important topics for understanding genomic heterogeneity in fungi and higher eukaryotes.

Methods

Media and reagents

Yeast peptone dextrose (YPD) was prepared as previously described72. YPD containing 40 mM and 80 mM hydrogen peroxide was prepared using Swan 3% hydrogen peroxide (Fisher Scientific, cat# 19-027033). Medium with 2-deoxygalactose (2-DOG) consisted of synthetic complete (SC) medium supplemented with 2% glycerol, 2 mg/ mL 2-DOG (Fluka, cat# 31050), and 2% agar as previously described72. Saccharomyces cerevisiae pre-sporulation (pre-spo) medium contained 0.8% yeast extract, 0.3% peptone, 10% glucose and 2% agar73.

Strains

The Candida albicans strains described in this study are listed in Supplementary Data 1. To minimize the impact of stochastic aneuploid chromosome loss as reported in previous studies26, all assays were performed using cell populations from the center portion of the primary streak inoculated into liquid cultures prior to the experiment.

Parasexual progeny screening for ploidy and expression

The previously constructed SC5314xSC5314 tetraploid mating product RBY18 was struck in quadrants on pre-spo agar medium and incubated at 37 °C for 7 days24,39. The resulting parasexual progeny were selected for loss of GAL1 from two Chr1 homologs on 2-DOG, indicative of reduced ploidy, and screened by flow cytometry for DNA content using 1 μM SYTOX Green stain. Putative aneuploid parasexual progeny, the parental diploid strain, the mated tetraploid, and aneuploid clinical isolates were grown in 4 mLs of liquid YPD at 30 °C to an OD600 of 1.0 and the culture split into two cryovials, snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at -80 °C. One vial was used for determining karyotype by ddRAD-Seq and the second half of the population was used to build RNA-Seq libraries.

ddRAD-sequencing library construction and data processing

Genomic DNA for each strain was isolated from 2 × 108 cells using the Quick-DNA™ Fungal/Bacterial Miniprep Kit (Zymo Research, cat# D6005) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Restriction enzymes, MboI and MfeI, were used to digest DNA into fragments to be ligated with a unique i5 adapter to pool samples into groups of 12. Each pool was size-selected using the Blue Pippin system (Sage Science, Beverly, MA) to obtain a pool with fragments sizes between 150 bp to 500 bp. Size-selected pools were PCR amplified for 14 cycles. During amplification, each pool was uniquely labeled with an i7 adapter to enable all pools to be combined into a single sequencing library. The library was sequenced as 50 bp single-end reads on a HiSeq 4000 platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA). Sequencing reads were aligned to the SC5314 reference genome Assembly 21 (A21-s02-m09-r10) with bowtie274 and the pileup used to determine chromosome copy number relative to the diploid parental strains. Screening criteria, defined as strains harboring only trisomic chromosomes, were established at the onset of the experiment.

RNA-sequencing library construction and data processing

RNA was harvested using MasterPure™ Yeast RNA Purification kit (Biosearch Technologies, cat# MPY03100) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and treated with DNase I. RNA concentrations were measured using a NanoDrop™ OneC (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA).

The NEBNext® Poly(A) mRNA Magnetic Isolation Module (NEB, cat# E7490L) was used to isolate polyadenylated RNA and the NEBNext® Ultra™ II Directional RNA Library Prep Kit (NEB, cat# E7760L) for Illumina® was used for library preparation, following the manufacturer’s instructions. Library quality was assessed using a 2100 Bioanalyzer and the Agilent High Sensitivity DNA Kit (Agilent, cat# 5067-4626). 109 libraries were split into five pools for sequencing. Each pool was loaded onto one lane of an Illumin HiSeq 4000 flow cell to generate single-end 50 bp reads to an average yield of 16.6 million reads per sample. FastQC (v0.11.7) was used to assess read quality75, and reads with Q ≥ 30 along its length were retained. Reads were aligned to the SC5314 reference genome Assembly 21 (A21-s02-m09-r10) using Spliced Transcripts Alignment to a Reference (STAR) (version 2.5.0a) with the default parameters except for alignIntronMin and alignIntronMax which were set to 30 and 1000 respectively76. Feature counts were generated using HTSeq (v0.8.0) against the SC5314 Assembly 21 genome feature file (GFF)77. The HTseq-count parameter stranded was set to reverse.

Hierarchical clustering of expression

Transcript per million (TPM) values for all genome features in the SC5314 Assembly 21 GFF were used to test similarity in gene expression using the pvclust package (v2.2.0)78 in R (v4.1.2). Clustering was performed using Spearman’s correlation and tested with 100 bootstraps. Screening criteria for inclusion were required biological replicates to cluster together and were pre-established.

Karyotype and transcriptional profiling plots

A custom script was built in R (v4.1.2) that plots TPM values and counts per million (CPM) of normalized ddRAD-seq data following normalization to the diploid control and log2 transformation. Data is adjusted such that the average TPM and CPM values on disomic chromosomes are plotted at 1. The geom_smooth function within ggplot2 is used to fit a first-degree local polynomial regression using the LOESS method79.

Expression of imbalanced genes in stoichiometric complexes

We selected a non-exhaustive list of protein complexes in C. albicans that are important for core processes, including chromatin remodeling, mitosis, translation, and transcriptional regulation. In total we selected 9 complexes (Mediator, DNApolII, RNApolII, RSC, Septin, SWI/SNF, t-UTP, Dam1, SAGA). We only included subunits that are encoded by a single gene. For the Mediator complex, only genes encoding components of the head and middle modules were included, excluding the multiple-member telomere-associated gene family (TLOs) and the tail module, which can be recruited and function independently within the cell80. Genes with average TPM values less than 1 and those found on Chr1 were removed from the analysis. In total, this provided 49 genes encoding stoichiometric subunits and 4,349 genes that served as the ‘all genes’ category for this analysis (Supplementary Data 5).

Differential expression analysis and gene ontology

Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were called using EdgeR (v3.36.0)81. To prevent genes on trisomic chromosomes from directly influencing DEG calls, chromosomes were analyzed individually, so that only gene counts for strains carrying disomic copies of the single chromosome were included. Genes with an average TPM of less than five were removed prior to calling DEGs. Fisher’s exact test was used to call DEGs with thresholds of at least a 2-fold change and a q-value < 0.05. DEGs for all eight chromosomes were combined, resulting in the transcriptional response to aneuploidy, referred to as the aneuploid stress response (ASR) (Supplementary Data 2). RNA-Seq datasets from Bruno et al.46 were processed using the same methods from the raw FASTQ deposit in the Sequence Read Archive (SRA).

Differential expression analysis was done in the same manner for comparison of the diploid and tetraploid strains, except that genes across all chromosomes were analyzed together. The data was processed as described above with the exception that reads were trimmed using Trimmomatic (v0.39 LEADING:3 TRAILING:3 SLIDINGWINDOW:4:15 MINLEN:36)82.

Gene Ontology (GO) analysis was done using the Candida Genome Database GO Term Finder (http://www.candidagenome.org/)83.

Growth rate

Overnight cultures were grown in 300 microliters (μLs) of liquid YPD at 30 °C, shaking at 125 revolutions per minute (rpm). Cultures were diluted 1:2000 in 200 μLs fresh liquid YPD or YPD + 2.5 mM H2O2. The OD600 was read every 15 minutes for 36 hours at 30 °C shaking at 250 rpm using a Synergy H1 microplate reader (Biotek, Shoreline, WA). Doubling time was calculated using custom scripts that identify the six time points where a linear regression fitted to the data has the steepest slope. All strains had four biological replicates, each with two technical replicates.

Flocculation assay

Overnight cultures grown in liquid YPD at 30 °C were vortexed and diluted to an OD600 of 1.5 in fresh liquid YPD with a final volume of 500 μLs. Each culture was vortexed and added to a channeled cuvette. Cuvettes were allowed to sit undisturbed with OD600 readings taken every 20 minutes during a 140-minute time-course with a ThermoFisher NanoDrop One (Fisher Scientific, Hampton, NH). All strains had three biological replicates.

Intracellular ROS assay and fluorescence imaging

Overnight cultures were grown in liquid YPD at 30 °C and diluted back 1:20 into 2 mLs fresh liquid YPD to begin logarithmic phase growth. Cultures were grown at 30 °C for 2.5 hours and counted with a hemocytometer. 4 × 107 cells were transferred into microcentrifuge tubes and spun at 3000 relative centrifugal force (rcf) for 3 minutes to pellet cells. The supernatant was discarded except for 200 μLs that was used to resuspend the cell pellet. In addition, 4 or 10 μLs of 10 mM H2DCF-DA was added (for quantification by fluorescence or microscopy, respectively) and the cell suspension vortexed to mix. A linear relationship between the amount of H2DCF-DA incubated with C. albicans cells and fluorescence exist across a dynamic range spanning 99-566 µM. These were incubated for 30 minutes at 30 °C with shaking at 225 rpm covered in foil. Following incubation, cells were spun at 3000 rcf for 3 minutes and washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) in two successive rounds. After the second wash, cells were resuspended in 500 μLs PBS and 200 μLs was transferred into an opaque black 96-well plate to read fluorescence (Ex 504 nm Em 529 nm) using a Synergy H1 microplate reader (Biotek, Shoreline, WA). All aneuploid strains had three biological replicates, the diploid was included with each reading to minimize run-to-run variation and had two or three biological replicates per run. For visualization, 10 μLs was transferred to a microscope slide and H2DCF-DA fluorescence was visualized under the FITC channel. Images were captured using an Axio Imager.D2 microscope (Zeiss, Thornwood, NY).

Pre-spo sensitivity assay

Strains were grown from freezer stocks on YPD agar at 30°C overnight and restruck on pre-sporulation (pre-spo) media the following day. Pre-spo plates were then incubated for four days at 37 °C. Colonies from each aneuploid strain were resuspended in PBS and diluted 1:100 into a 1:3000 dilution of propidium iodide (final concentration of 333 pg/mL). The heat-killed control was prepared by boiling cell resuspension at 95 °C for 5 minutes. Dyed resuspensions were then analyzed on a Millipore Guava EasyCyte flow cytometer (Millipore, Burlington, MA) or ThermoFisher Attune NxT v6 (ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA) for 50,000 events. Three biological replicates were performed.

Spot assay

Overnight cultures were grown in liquid YPD at 30 °C and diluted back 1:20 into 2 mLs of fresh liquid YPD to begin logarithmic phase growth. Cultures were grown at 30 °C for 2.5 hours and counted with a hemocytometer. 1×107 cells were taken and spun at 3,000 rcf for 3 minutes. The supernatant was removed, and the pellet was resuspended in 500 μLs of either YPD, YPD + 40 mM H2O2, or YPD + 80 mM H2O2. These were incubated for 30 minutes at 30 °C shaking at 225 rpm covered in foil. Following the incubation, 10-fold dilutions were made to 1 × 105 cells in PBS and 5 μLs of each dilution was spotted onto solid YPD agar medium. Plates were incubated for 24 hours at 30 °C before imaging using a ChemiDoc XRS+ molecular imager (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). This was done with a minimum of three biological replicates per strain and condition. Spot images were then analyzed for average pixel brightness using ImageJ84.

Fluconazole disc assay

Overnight cultures were grown in liquid YPD at 30 oC, vortexed, and diluted to an OD600 of 0.04 in fresh liquid YPD in a final volume of 1 mL. From this, 70 μLs was plated onto YPD solid agar medium and spread using glass beads. Plates were allowed to dry at room temperature for 1 hour and a 25 mM fluconazole disc was then placed in the center of the plate. Plates were incubated for 48 hours at 30 °C before imaging using a ChemiDoc XRS+ molecular imager (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Plate images were analyzed using DiskImageR85, and the fraction of growth (FoG20) and resistance (RAD20) scores used to determine tolerance and resistance, respectively.

Statistics and Reproducibility

Expression profiling was performed with two biological replicates per aneuploid strain and five replicates per control because of the aggregated approach taken here to defining altered expression on each chromosome. All phenotypic experiments were performed with a minimum of three biological replicates. No statistical method was used to predetermine sample sizes. No data were excluded from analyses. The investigators were blinded for flocculation assays but were not blinded for any other experiments using automated quantification and outcome assessment. The diploid control and Tri 4,5,6,7 strains were used as replication controls in assessing strains harboring complex aneuploidies in Figure S1 and the Chr7 trisomic strains in Figure S10. All phenotypes were able to be replicated with these strains.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The sequencing data generated in this study have been deposited in the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database under accession code PRJNA855681. The experimental data generated in this study are provided in the Supplementary Information/Source Data File. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

Code used to generate growth curve statistics is available at https://github.com/andersonlabgroup/Growth_curve_Mackey/blob/main/AM_Growth_Curve_Script_Corrected.Rmd.

References

Torres, E. M. et al. Effects of aneuploidy on cellular physiology and cell division in haploid yeast. Science 317, 916–924 (2007).

Hassold, T. J. A cytogenetic study of repeated spontaneous abortions. Am. J. Hum. Genet 32, 723–730 (1980).

Williams, B. R. et al. Aneuploidy affects proliferation and spontaneous immortalization in mammalian cells. Science 322, 703–709 (2008).

Sheltzer, J. M., Torres, E. M., Dunham, M. J. & Amon, A. Transcriptional consequences of aneuploidy. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 12644–12649 (2012).

Wang, F. et al. Integrated transcriptomic-genomic tool Texomer profiles cancer tissues. Nat. Methods 16, 401–404 (2019).

Mohanty, V., Akmamedova, O. & Komurov, K. Selective DNA methylation in cancers controls collateral damage induced by large structural variations. Oncotarget 8, 71385–71392 (2017).

Mohanty, V., Wang, F., Mills, G. B., Network, C. T. D. R. & Chen, K. Uncoupling of gene expression from copy number presents therapeutic opportunities in aneuploid cancers. Cell Rep. Med. 2, 100349 (2021).

Hose, J. et al. Dosage compensation can buffer copy-number variation in wild yeast. Elife 4, https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.05462 (2015).

Zhu, J., Tsai, H. J., Gordon, M. R. & Li, R. Cellular Stress Associated with Aneuploidy. Dev. Cell 44, 420–431 (2018).

Gordon, D. J., Resio, B. & Pellman, D. Causes and consequences of aneuploidy in cancer. Nat. Rev. Genet 13, 189–203 (2012).

Dephoure, N. et al. Quantitative proteomic analysis reveals posttranslational responses to aneuploidy in yeast. Elife 3, e03023 (2014).

Sheltzer, J. M. & Amon, A. The aneuploidy paradox: costs and benefits of an incorrect karyotype. Trends Genet 27, 446–453 (2011).

Thompson, S. L., Bakhoum, S. F. & Compton, D. A. Mechanisms of chromosomal instability. Curr. Biol. 20, R285–R295 (2010).

Tang, Y. C., Williams, B. R., Siegel, J. J. & Amon, A. Identification of aneuploidy-selective antiproliferation compounds. Cell 144, 499–512 (2011).

Stingele, S. et al. Global analysis of genome, transcriptome and proteome reveals the response to aneuploidy in human cells. Mol. Syst. Biol. 8, 608 (2012).

Gasch, A. P. et al. Genomic expression programs in the response of yeast cells to environmental changes. Mol. Biol. Cell 11, 4241–4257 (2000).

Mulla, W., Zhu, J. & Li, R. Yeast: a simple model system to study complex phenomena of aneuploidy. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 38, 201–212 (2014).

Whittaker, S. G. et al. The detection of mitotic and meiotic aneuploidy in yeast using a gene dosage selection system. Mol. Gen. Genet 215, 10–18 (1988).

Ni, M. et al. Unisexual and heterosexual meiotic reproduction generate aneuploidy and phenotypic diversity de novo in the yeast Cryptococcus neoformans. PLoS Biol. 11, e1001653 (2013).

Ropars, J. et al. Gene flow contributes to diversification of the major fungal pathogen Candida albicans. Nat. Commun. 9, 2253 (2018).

Hirakawa, M. P. et al. Genetic and phenotypic intra-species variation in Candida albicans. Genome Res. 25, 413–425 (2015).

Ford, C. B. et al. The evolution of drug resistance in clinical isolates of candida albicans. eLife 2015, https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.00662 (2015).

Harrison, B. D. et al. A tetraploid intermediate precedes aneuploid formation in yeasts exposed to fluconazole. PLoS Biol. 12, e1001815 (2014).

Forche, A. et al. The parasexual cycle in Candida albicans provides an alternative pathway to meiosis for the formation of recombinant strains. PLoS Biol. 6, e110 (2008).

Anderson, M. Z., Thomson, G. J., Hirakawa, M. P. & Bennett, R. J. A ‘parameiosis’ drives depolyploidization and homologous recombination in Candida albicans. Nat. Commun. 10, 4388 (2019).

Hickman, M. A., Paulson, C., Dudley, A. & Berman, J. Parasexual Ploidy Reduction Drives Population Heterogeneity Through Random and Transient Aneuploidy in Candida albicans. Genetics 200, 781–794 (2015).

Bennett, R. J. & Johnson, A. D. Completion of a parasexual cycle in Candida albicans by induced chromosome loss in tetraploid strains. EMBO J. 22, 2505–2515 (2003).

Bouchonville, K., Forche, A., Tang, K. E., Selmecki, A. & Berman, J. Aneuploid chromosomes are highly unstable during DNA transformation of Candida albicans. Eukaryot. Cell 8, 1554–1566 (2009).

Selmecki, A., Forche, A. & Berman, J. Aneuploidy and isochromosome formation in drug-resistant Candida albicans. Science 313, 367–370 (2006).

Kravets, A. et al. Widespread occurrence of dosage compensation in Candida albicans. PLoS One 5, e10856 (2010).

Tucker, C. et al. Transcriptional Regulation on Aneuploid Chromosomes in Divers Candida albicans Mutants. Sci. Rep. 8, 1630 (2018).

Selmecki, A., Gerami-Nejad, M., Paulson, C., Forche, A. & Berman, J. An isochromosome confers drug resistance in vivo by amplification of two genes, ERG11 and TAC1. Mol. Microbiol. 68, 624–641 (2008).

Ene, I. V. et al. Global analysis of mutations driving microevolution of a heterozygous diploid fungal pathogen. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, E8688–E8697 (2018).

Kakade, P., Sircaik, S., Maufrais, C., Ene, I. V. & Bennett, R. J. Aneuploidy and gene dosage regulate filamentation and host colonization by Candida albicans. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2218163120 (2023).

Yang, F. et al. The fitness costs and benefits of trisomy of each Candida albicans chromosome. Genetics 218, https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/iyab056 (2021).

Hirakawa, M. P., Chyou, D. E., Huang, D., Slan, A. R. & Bennett, R. J. Parasex Generates Phenotypic Diversity de Novo and Impacts Drug Resistance and Virulence in Candida albicans. Genetics 207, 1195–1211 (2017).

Janbon, G., Sherman, F. & Rustchenko, E. Monosomy of a specific chromosome determines L-sorbose utilization: a novel regulatory mechanism in Candida albicans. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 95, 5150–5155 (1998).

Anderson, M. Z., Saha, A., Haseeb, A. & Bennett, R. J. A chromosome 4 trisomy contributes to increased fluconazole resistance in a clinical isolate of Candida albicans. Microbiol. (Read.) 163, 856–865 (2017).

Thomson, G. J., Kakade, P., Hirakawa, M. P., Ene, I. V. & Bennett, R. J. Adaptation to the dietary sugar D-tagatose via genome instability in polyploid Candida albicans cells. G3 (Bethesda), https://doi.org/10.1093/g3journal/jkab110 (2021).

Brennan, C. M. et al. Protein aggregation mediates stoichiometry of protein complexes in aneuploid cells. Genes Dev. 33, 1031–1047 (2019).

Santaguida, S., Vasile, E., White, E. & Amon, A. Aneuploidy-induced cellular stresses limit autophagic degradation. Genes Dev. 29, 2010–2021 (2015).

Durrbaum, M. et al. Unique features of the transcriptional response to model aneuploidy in human cells. BMC Genom. 15, 139 (2014).

Tsai, H. J. et al. Hypo-osmotic-like stress underlies general cellular defects of aneuploidy. Nature 570, 117–121 (2019).

Moran, G. P., Anderson, M. Z., Myers, L. C. & Sullivan, D. J. Role of Mediator in virulence and antifungal drug resistance in pathogenic fungi. Curr. Genet. 65, 621–630 (2019).

Tsong, A. E., Miller, M. G., Raisner, R. M. & Johnson, A. D. Evolution of a combinatorial transcriptional circuit: a case study in yeasts. Cell 115, 389–399 (2003).

Bruno, V. M. et al. Comprehensive annotation of the transcriptome of the human fungal pathogen Candida albicans using RNA-seq. Genome Res. 20, 1451–1458 (2010).

Li, M. et al. The ATM-p53 pathway suppresses aneuploidy-induced tumorigenesis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 14188–14193 (2010).

Joy, J. et al. Proteostasis failure and mitochondrial dysfunction leads to aneuploidy-induced senescence. Dev. Cell 56, 2043–2058 e2047 (2021).

Thomson, G. J. et al. Metabolism-induced oxidative stress and DNA damage selectively trigger genome instability in polyploid fungal cells. EMBO J. 38, e101597 (2019).

Kaloriti, D. et al. Mechanisms underlying the exquisite sensitivity of Candida albicans to combinatorial cationic and oxidative stress that enhances the potent fungicidal activity of phagocytes. mBio 5, e01334–01314 (2014).

Yang, F. et al. Antifungal Tolerance and Resistance Emerge at Distinct Drug Concentrations and Rely upon Different Aneuploid Chromosomes. mBio 14, e0022723 (2023).

Beaupere, C. et al. Genetic screen identifies adaptive aneuploidy as a key mediator of ER stress resistance in yeast. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, 9586–9591 (2018).

Oromendia, A. B., Dodgson, S. E. & Amon, A. Aneuploidy causes proteotoxic stress in yeast. Genes Dev. 26, 2696–2708 (2012).

Terhorst, A. et al. The environmental stress response causes ribosome loss in aneuploid yeast cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 17031–17040 (2020).

Thorburn, R. R. et al. Aneuploid yeast strains exhibit defects in cell growth and passage through START. Mol. Biol. Cell 24, 1274–1289 (2013).

Hickman, M. A. et al. The ‘obligate diploid’ Candida albicans forms mating-competent haploids. Nature 494, 55–59 (2013).

Storchova, Z. et al. Genome-wide genetic analysis of polyploidy in yeast. Nature 443, 541–547 (2006).

Romo, J. A. & Kumamoto, C. A. On commensalism of candida. J. Fungi 6, 27–30 (2020).

Zakikhany, K. et al. In vivo transcript profiling of Candida albicans identifies a gene essential for interepithelial dissemination. Cell Microbiol 9, 2938–2954 (2007).

Bailey, D. A., Feldmann, P. J., Bovey, M., Gow, N. A. & Brown, A. J. The Candida albicans HYR1 gene, which is activated in response to hyphal development, belongs to a gene family encoding yeast cell wall proteins. J. Bacteriol. 178, 5353–5360 (1996).

Cottier, F. et al. Remasking of Candida albicans beta-Glucan in Response to Environmental pH Is Regulated by Quorum Sensing. mBio 10, https://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.02347-19 (2019).

Cabral, V. et al. Targeted changes of the cell wall proteome influence Candida albicans ability to form single- and multi-strain biofilms. PLoS Pathog. 10, e1004542 (2014).

Chen, Y. C., Wu, C. C., Chung, W. L. & Lee, F. S. Differential secretion of Sap4-6 proteins in Candida albicans during hyphae formation. Microbiol. (Read.) 148, 3743–3754 (2002).

Miramon, P. et al. Cellular responses of Candida albicans to phagocytosis and the extracellular activities of neutrophils are critical to counteract carbohydrate starvation, oxidative and nitrosative stress. PLoS One 7, e52850 (2012).

Yang, F. et al. Aneuploidy enables cross-adaptation to unrelated drugs. Mol. Biol. Evol. 468, 321–325 (2019).

Brown, A. J., Brown, G. D., Netea, M. G. & Gow, N. A. Metabolism impacts upon Candida immunogenicity and pathogenicity at multiple levels. Trends Microbiol 22, 614–622 (2014).

Enjalbert, B. et al. Role of the Hog1 stress-activated protein kinase in the global transcriptional response to stress in the fungal pathogen Candida albicans. Mol. Biol. Cell 17, 1018–1032 (2006).

Forche, A. et al. Selection of Candida albicans trisomy during oropharyngeal infection results in a commensal-like phenotype. PLoS Genet 15, e1008137 (2019).

Muzzey, D., Sherlock, G. & Weissman, J. S. Extensive and coordinated control of allele-specific expression by both transcription and translation in Candida albicans. Genome Res. 24, 963–973 (2014).

Selmecki, A., Gerami-Nejad, M., Paulson, C., Forche, A. & Berman, J. An isochromosome confers drug resistance in vivo by amplification of two genes, ERG11 and TAC1. Mol. Microbiol 68, 624–641 (2008).

Liang, S. H. et al. Hemizygosity Enables a Mutational Transition Governing Fungal Virulence and Commensalism. Cell Host Microbe 25, 418–431.e416 (2019).

Guthrie, C. & Fink, G. R. Guide to Yeast Genetics and Molecular Biology. Methods Enzymol. 194, 165–186 (1991).

Codon, A. C., Gasent-Ramirez, J. M. & Benitez, T. Factors Which Affect the Frequency of Sporulation and Tetrad Formation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae Baker’s Yeasts. Appl Environ. Microbiol 61, 1677 (1995).

Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 9, 357–359 (2012).

Andrews, S. FastQC: a quality control tool for high throughput sequence data. Available online at: http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc (2010).

Dobin, A. et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29, 15–21 (2013).

Anders, S., Pyl, P. T. & Huber, W. HTSeq–a Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics 31, 166–169 (2015).

Suzuki, R. & Shimodaira, H. Pvclust: an R package for assessing the uncertainty in hierarchical clustering. Bioinformatics 22, 1540–1542 (2006).

Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. Springer-Verlag New York. https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org (2016).

Ansari, S. A. et al. Distinct role of Mediator tail module in regulation of SAGA-dependent, TATA-containing genes in yeast. EMBO J. 31, 44–57 (2012).

Robinson, M. D., McCarthy, D. J. & Smyth, G. K. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 26, 139–140 (2010).

Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M. & Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114–2120 (2014).

Skrzypek, M. S. et al. The Candida Genome Database (CGD): Incorporation of Assembly 22, systematic identifiers and visualization of high throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, D592–D596 (2017).

Schneider, C. A., Rasband, W. S. & Eliceiri, K. W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods 9, 671–675 (2012).

Gerstein, A. C., Rosenberg, A., Hecht, I. & Berman, J. diskImageR: quantification of resistance and tolerance to antimicrobial drugs using disk diffusion assays. Microbiol. (Read.) 162, 1059–1068 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Diego Martinez and Joshua Wang for initial analysis of gene expression in aneuploid C. albicans clinical isolates in addition to members of the Anderson and Chad Rappleye labs for helpful discussion throughout the project. We also thank Hung-Ji Tsai for useful conversations in contextualizing the phenotypic roles observed in the aneuploid strains. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants U19AI110818 (to C.A.C.), R21AI144651 (to R.J.B.), 1R01AI41893 (to R.J.B.), 1R01AI148788 (to M.Z.A.), a Burroughs Wellcome Fund Investigator in the Pathogenesis of Infectious Disease Award (#1020388) to A.S., and an NSF CAREER Award 2046863 to M.Z.A. Additionally, R.J.F. was supported by a F31DE029409.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.I.M., C.A.C., R.J.B., and M.Z.A. conceived and designed experiments. A.I.M., R.J.F., P.S.H., G.J.T., and M.Z.A. performed experiments and analyzed data. A.I.M. and M.Z.A. wrote the initial version of the manuscript. A.I.M., C.A.C., R.J.B., and M.Z.A. edited the manuscript, and all authors approved the final version. R.J.B. and M.Z.A. supervised this work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Feng Yang and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mackey, A.I., Fillinger, R.J., Hendricks, P.S. et al. Aneuploidy confers a unique transcriptional and phenotypic profile to Candida albicans. Nat Commun 16, 3287 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-58457-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-58457-3

This article is cited by

-

Uncovering actionable trade-offs of antifungal resistance in a yeast pathogen

Molecular Systems Biology (2026)

-

Inducible chromosomal rearrangement reveals nonlinear polygenic dosage effects in driving aneuploid yeast traits

Nature Communications (2025)