Abstract

Accurate ground-level ozone (O3) estimation is crucial for assessing health impacts and designing control strategies. Traditional polar-orbit satellites provide limited, one-time measurements, missing O3’s diurnal variability. Here, we utilize a next-generation geostationary satellite with ultraviolet capabilities to retrieve hourly O3 concentrations, achieving high accuracy (R2 = 0.94) and improving daily maximum 8-hour estimates, particularly in semi-urban areas (R2 + 0.10, error reduction >7 μg/m³). Our analysis reveals a 30% drop in O3-related health risks compared to traditional polar-orbit estimates, with the greatest impact in semi-urban and rural areas where satellite data plays an important role due to the lack of ground measurements. This suggests prior estimates may have overestimated total mortality and urban-rural spillover effects. Our findings underscore the importance of geostationary satellites in capturing O3 diurnal variability through refined hourly data on photochemical precursors and radiation, providing a scientific basis for health assessments and informing O3 pollution regulations in China.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

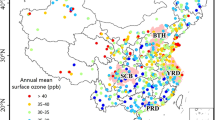

Exposure to ozone (O3), whether short-term or long-term, significantly increases the risk of premature mortality1,2,3,4,5, resulting in approximately 423,1006 deaths globally in 2019. China ranks second globally in O3-related mortalities, with over 50,000 deaths in 2019 amidst a recent surge in O3 levels7,8. To combat O3 pollution and protect human health, ground observational networks such as the China National Environmental Monitoring Center have been established and are expanding to monitor ambient O3 concentration. However, current monitoring sites are mostly located in urban areas, which are unable to provide a comprehensive evaluation of the entire spatial distribution, particularly for downwind or rural areas, necessitating the use of satellite measurements to retrieve spatially continuous concentrations.

Polar-orbit satellites have been extensively used to retrieve ground-level O3 concentrations9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16, by offering large spatial coverage measurements of atmospheric chemical column density which are strongly corelated with ground-level O317,18,19. Among these, the TROPOspheric Monitoring Instrument (TROPOMI) has gained prominence in recent studies due to its high spatial resolution (0.05° × 0.05°), making it a widely utilized satellite product for atmospheric monitoring and O3 measurement14,20,21. This spatial resolution surpasses that of other polar-orbit satellites, such as Ozone Monitoring Instrument (OMI), and Suomi National Polar-orbiting Partnership (SNPP), which have relatively coarse spatial resolution (0.25°), limiting their applicability for high-resolution estimations in fine-scale environmental assessments. However, like other polar-orbiting satellites, TROPOMI has limited temporal resolution (typically once per day), posing challenges in capturing the diurnal variations of ground-level O₃22,23,24, which exhibit significant fluctuations throughout the day due to its photochemical nature25,26. Low tropospheric O3 primarily forms through a series of photochemical reactions involving precursors as nitrogen dioxide (NO2) and volatile organic compounds (VOCs)27,28 with ultraviolet (UV) irradiance playing a crucial role in initiating the O3 catalytic cycle29,30. The lack of detailed information to represent these photochemical reactions makes it difficult for polar-orbit satellites to accurately capture O3 diurnal variations. Despite ongoing efforts, achieving satisfactory O3 retrievals via polar-orbit satellite observations remains elusive31,32.

Recent launches of geostationary environmental satellites with hourly resolution offer significant potential for improving the O3 retrievals. One advantage is its detailed representation of precursor levels throughout the day, which effectively addresses the limitations of existing studies that have relied on satellite-observed radiances as indicators of ground-level O333,34,35 but without incorporating information on precursor concentrations. Another and more important advantage is the measurement of UV radiance, which plays a crucial role in characterizing the diurnal patterns of ground-level O3 more effectively than the general radiances used previously12. Measuring UV signals has traditionally been challenging with geostationary passive remote sensing sensors. However the recently launched Geostationary Environment Monitoring Spectrometer (GEMS) in 2020 is the first geostationary sensor equipped with an UV-visible instrument, offering significant advantages over previously launched geostationary satellites36. With detailed information on O3 precursors and UV irradiance, thorough validation of its data quality37,38,39 and previous successful applications in retrieving ground-level NO240,41,42, the GEMS offers enhanced capabilities and high reliability for representing diurnal variations in O₃ photochemistry. Moreover, capturing the diurnal variation of O3 is crucial for assessing O3-related health effects. The daily maximum 8-hour average (MDA8), calculated from hourly O3 retrievals, is proven to be a robust index for representing human exposure to O3 and quantifying associated health impacts43,44,45,46. Thus, the hourly data provided by geostationary satellites offer a unique advantage in improving the ground-level O3 retrievals for health assessments compared to traditional studies that rely on single-time polar-orbit satellite observations.

Here, we present a study for hourly ground-level O3 retrieval using geostationary satellite data to improve the estimation of associated O3 exposures and health effects. Specifically, we efficiently leverage the detailed information from geostationary satellite products, including GEMS-based hourly precursor concentrations and UV radiation, to accurately represent the photochemistry of O3 with time-specific machine learning model (as illustrated in Fig. 1), which is commonly employed to establish the relationship between ground-level O3 concentrations and O3 precursors47,48,49, enabling effective derivation of ground-level concentrations from column information. By overcoming the limitations of traditional polar-orbit TROPOMI estimates, which rely on specific-hour O3 precursor observations, the new GEMS estimations benefit from multiple-hour measurement data, resulting in more precise O3 retrievals and improved assessment of O3-related health effects. We found that the new estimates from GEMS data significantly improve the accuracy of both hourly and daily ground-level O3 retrievals, with increased R² (over 0.05) and reduced root mean squared error (about 2 μg/m3). This approach effectively mitigates the overestimation of O3 levels based on previous polar-orbit satellites, revealing smaller O3-related health risks (by 30%) and urban-rural spillover effects than traditionally thought.

Results

Enhanced MDA8-O3 estimates with hourly geostationary satellite retrievals

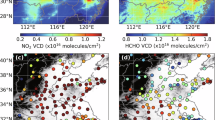

The high temporal resolution of the GEMS satellite, with hourly measurements, significantly improves the accuracy of surface MDA8-O3 estimation compared to polar-orbit satellites like TROPOMI across all sites (Fig. 2a). This enhancement is evidenced by a site-based mean increase in R² of over 0.10 and a reduction in absolute error exceeding 7 μg/m³ annually, with improvements observed across all months (R2 increased by 0.06–0.17; absolute error reduced by 1.67–3.97 μg/m³, month-based) and specific hours (Supplementary Table 1). Apparently, GEMS’s valuable hourly precursor and UV data successfully address TROPOMI’s limitation of having only one-time-per-day measurements, which are insufficient for representing O₃ diurnal variation.

The most significant improvements are observed in semi-urban areas (Fig. 2b; Supplementary Fig. 1), with an enhancement of R² exceeding 0.15 (ranging from 0.11 to 0.25 at the 25th percentile) and a reduction in absolute error of 6.94 μg/m³ (ranging from 5.18 to 8.84 at the 25th percentile) (Supplementary Table 2). This significant improvement is attributed to the strong diurnal variation of precursors in semi-urban areas (Fig. 2c), particular for NO2, whose relative standard deviation is 23% and 10% higher than in urban and rural area, respectively. The areas with strong diurnal variance benefit significantly from the GEMS hourly observations, enabling accurate estimation of hourly O3 concentrations and, consequently, more precise determination of MDA8 O3 (Supplementary Fig. 2).

A large improvement is also observed in remote regions such as western and southern China, where over 70% of sites show R² enhancements greater than 0.05, and over 20% exceed 0.30. This is due to the region’s relatively sparse ground measurements, which rely more on satellite data. These results indicate that GEMS’s hourly data will significantly benefit O3 prediction in areas with limited ground measurements that were previously difficult to predict accurately. We also found that this improvement applies to all days across different pollution levels, indicating an even larger reduction in absolute error during high O3 episodes due to the high baseline concentration (Supplementary Fig. 3). Therefore, in addition to annual averages, GEMS hourly data will also enhance the estimation of daily variation, which is crucial for assessing short-term O3 exposure and associated health impacts.

New GEMS retrievals mitigate overestimation of O3 level from polar-orbit satellite

Following the discussion on the enhanced model accuracy with GEMS data, the discrepancy between new GEMS- and previously TROPOMI-retrieved MDA8-O₃ can be seen as reflecting uncertainties in previous O₃ level estimations. As shown in Fig. 3, the new GEMS predictions lead to a substantial reduction in MDA8-O₃ by 10 μg/m³ in most regions, particularly in Central and Northern China, where high O₃ pollution (>120 μg/m³) is prevalent (Fig. 3d). The reduction is especially pronounced in rural areas (by 4 μg/m³), which are far away from ground-based measurements and thus rely heavily on satellite data. A considerable reduction is also observed in semi-urban regions (by 2 μg/m³) during warm seasons when O₃ levels are consistently high. These results suggest that previous TROPOMI estimates may have significantly overestimated MDA8-O₃ in most of regions, particularly in warm seasons. Urban areas show minimal impact from GEMS data, with differences within 1 μg/m³, likely due to the constraints of monitoring sites being located within urban areas.

a Spatial distribution at annual averaged level, with brown color indicating an increased estimation by GEMS, while the blue color indicates a reduced estimation by GEMS; b, c Across three regions in warm seasons (Apr-Oct) and cool seasons (Nov-Mar); d, e Spatial distribution of MDA8 in warm seasons and cool seasons. The purple color suggests higher MDA8 values and green color represents lower MDA8 values.

The new GEMS-estimated MDA8-O₃ shows higher O₃ levels in Southeast, Northwest, and Northeast China, with an increase of 9.6 μg/m³ compared to previous estimates from TROPOMI, particularly in spring and winter (Supplementary Fig. 4). This suggests that TROPOMI may have underestimated O₃ levels in remote areas and during cool season.

The discrepancy in MDA8 estimations between GEMS and TROPOMI is largely due to their different representations of diurnal variation. More specifically, TROPOMI uses a single measurement hour to approximate this, resulting in considerable uncertainties. In contrast, these uncertainties can be effectively reduced with the detailed hourly variations provided by GEMS. To illustrate this, we introduce a deviation ratio calculated by the difference between GEMS- and TROPOMI-estimated MDA8-O₃ to quantify the discrepancy between the two. A strong spatial pattern is evident in the deviation ratio (Fig. 4a), with more pronounced discrepancies (8%, compared to the national average of 5%) in the southern provinces of China, particularly in Hong Kong & Macau, Fujian, and Guangdong. This is due to their relatively strong O₃ diurnal variance, indicated by the ratio of daily peak-hour O₃ (i.e., MDA1) to MDA8. Strong O₃ diurnal variance leads to large discrepancies between GEMS and TROPOMI (Fig. 4b), highlighting the greater effectiveness of using the hourly GEMS dataset to improve O₃ estimation in regions with significant diurnal variations.

a Comparison of O3 estimations between GEMS and TROPOMI among provinces: the diurnal O3 retrieved by GEMS is represented by the solid curves in each region, while the dashed lines represent the MDA8-O3 estimated by polar-orbit TROPOMI. The colored background indicates the discrepancies in MDA8-O3 estimations between GEMS and TROPOMI, averaged for all grids in each province. The whiter color of the background indicates less deviation between GEMS- and TROPOMI-based estimations, while orange color suggests more notable deviations; b Correlations between the discrepancies of MDA8-O3 estimates and the diurnal O₃ variation (quantified by the ratio of MDA1-O3 to MDA8-O3): the size of the circles indicates the MDA8-O3 level of each province.

New estimates indicate smaller O3-related health risks and urban-rural spillover effects

From the original TROPOMI, lower MDA8-O3 estimated in new GEMS has resulted in a substantial reduction in O3-related mortalities (Fig. 5a), with decreases of 29.1% and 33.0% in short-term and long-term risks, respectively, implying considerable overestimation in the traditional O3-related health risks using TROPOMI. The changes are mostly significant in densely populated regions of central and eastern China, with over 30,000 and 50,000 fewer total mortalities for both short-term and long-term risks, including the provinces of Shandong, Henan, and Hebei, which experience the highest O3-related health impacts from both short-term and long-term exposures. A significant reduction of 55.1% is also found in northwestern and south China where experience large O3 estimation deviations from TROPOMI to GEMS, particularly in Sichuan, where mortality rates exceed 3000 due to long-term exposure.

Furthermore, given that MDA8-O₃ changes more in rural areas but less in urban areas, as previously discussed due to the greater effectiveness of GEMS in areas lacking ground measurements, O₃-related mortality in semi-urban and rural areas is reduced more significantly (by 26–39%) compared to urban areas (by 22–23%) (Fig. 5b). This results in a smaller urban-rural spillover effect (i.e., semi-urban and rural areas suffering from pollution originating in urban areas) from the original TROPOMI assessment50,51.

Discussion

Since ground-level O3 has been surging in China in recent years, attention has increasingly focused on the health effects caused by ground-level O3. Accurate and comprehensive observation of O3 is vital for the prevention and control of O3 pollution. Although previous studies have mapped O3 diurnal patterns to some extent, the lack of diurnal measurements has largely limited the applicability and accuracy of these methods, as well as subsequent health effect assessments. This study successfully leveraged the next-generation geostationary satellite equipped with ultraviolet capacities to achieve accurate retrieval of hourly O3 concentrations, demonstrating the importance of implementing detailed diurnal patterns of precursors and UV information for the O3 retrievals to address the limitation of current estimates based on polar-orbit satellites like TROPOMI. The refined O₃ diurnal patterns and subsequent health effect assessments will greatly aid in the prevention and control of O₃-related hazards, as well as the design of satellite spectra and observation patterns in environmental studies. The methodology proposed here can be applied to retrieve hourly O3 data worldwide, advancing air quality monitoring. Although this study focuses on China due to the GEMS coverage in East Asia, the approach can easily be extended to other regions, such as North America, where the new TEMPO geostationary satellite provides coverage52. The improvement in hourly O3 estimations have great potential to enable the calibration of cohort studies on O3-related health risks, enhancing the accuracy of health risk assessments. Furthermore, our findings reveal urban-rural differences in O3 diurnal patterns, highlighting the need for environmental justice investigations and informing policies aimed at addressing disparities in air quality and promoting more equitable environmental outcomes.

We conducted multiple sensitivity experiments to eliminate other confounding factors that might influence the comparison between GEMS and TROPOMI estimates. First, retrieving hourly-level O₃ data is essential for optimal MDA8-O₃ estimation. The model’s accuracy in directly predicting MDA8-O₃ is worse (R² is reduced by 0.02 from the original 0.94) compared to predicting O₃ for each hour individually and then estimating MDA8-O₃, even using the same GEMS dataset (see Supplementary Fig. 5). The detailed statistics and comparisons in terms of space and time are demonstrated in Supplementary Text 6. This suggests that incorporating detailed constraints at the hourly level will improve the prediction of the overall value of MDA8-O₃. Second, diurnal features from GEMS data are crucial for MDA8-O₃ estimation. The model’s accuracy using all GEMS hourly features throughout the day is better (R² increased by 0.007 from 0.914) compared to using GEMS features from just one specific hour (14:00 local time), which is the single-hour measured by TROPOMI (see Supplementary Fig. 5 compared with Supplementary Fig. 6). This demonstrates the importance of the GEMS diurnal dataset even for the direct prediction of MDA8-O₃. Third, the UV and precursor measurements in GEMS also contribute to the improvement of GEMS estimated O3, as the model accuracy is considerable better (R² increased by 0.028 from 0.886) by using only GEMS 14:00 feature to predict the MDA8-O3, as compared to that using TROPOMI (see Supplementary Fig. 6 compared with Supplementary Fig. 7). This result demonstrates the usefulness of GEMS UV measurements for O₃ retrievals, as they show a stronger association with O₃ compared to the visible bands used in previous studies34,35.

The data quality of satellite observations, including NO2 column, HCHO column, and UVI, has been thoroughly validated in previous studies38,39,53,54. Although biases and uncertainties are present to some extent, our experiment using a Monte Carlo-based perturbation method indicates that these uncertainties have a negligible impact on the accuracy of surface O3 estimation, as perturbations in satellite products lead to less than a 2% variance in O3 concentrations across dominant retrieved grids (detailed in Supplementary Texts 1–3). These results highlight the capability of machine learning algorithms to effectively process original satellite column datasets. We further explore the impact of diurnally varying bias of the satellite observations of NO2 column by replacing the original NO2 column with a temporally modulated dataset from Oak et al54. The results indicate a limited impact on O3 concentration (detailed in Supplementary Text 1), implying the machine learning model can effectively correct certain diurnal bias in the GEMS NO2 column, to capture the diurnal patterns of the NO2 column and generate accurate surface O3 concentrations.

Given that diurnal patterns of O₃ concentration vary significantly from urban to rural areas55, but most ground measurements are located in urban areas, the success of machine-learning-based models in interpolating ground measurements (the labels) to the entire space largely depends on the model’s ability to identify urban and rural conditions. Therefore, any features used as indicators for distinguishing urban from rural conditions become even more important. NO2 concentration, a precursor mostly emitted from urban areas with numerous anthropogenic sources such as industrial combustion and transportation, is such one key feature. As expected, the NO2 column density shows the greatest ability to distinguish urban patterns from rural patterns among all features (see Supplementary Fig. 8), with urban NO2 levels at least twice as high as those in rural areas. However, this difference varies significantly throughout the day, ranging from 2.3 to 4.1, with the highest effectiveness occurring around 11:00 am and substantially reducing thereafter. Fortunately, GEMS data, which provide hourly NO2 column measurements, do not suffer from such impacts. In contrast, polar-orbiting satellite sensors, such as TROPOMI, are affected, reducing their ability to capture O3 urban-rural patterns due to their overpass time (14:00), which usually occurs under conditions with a lower urban-rural NO2 ratio. The ability to distinguish urban and rural patterns by GEMS satellite data is further demonstrated by the reduced contribution of the socio-economic features (i.e., land use, road density and population) to model performance. Specifically, these socio-economic features, which can significantly enhance the model performance in the TROPOMI-based model, have limited impact on the GEMS-based model. This is due to the advantage of GEMS, which can, to some extent, distinguish urban and rural regions using the hourly-level column information (Supplementary Fig. 8), making the socio-economic features less important. These results further demonstrate the importance of the hourly dataset provided by GEMS for predicting diurnal O3 variations. Consequently, the hourly-level O3 concentration can successfully depict the urban-rural O3 diurnal variation. As demonstrated in Supplementary Fig. 10, the diurnal patterns of O3 concentration suggest a higher deviation in rural regions than urban regions where monitoring sites are sparse or absent, implying challenge of accurate estimation in rural areas without detailed diurnal data from GEMS satellite.

As previously discussed, GEMS data is most beneficial in regions with the strongest diurnal variations (quantified by the ratio of MDA1/MDA8). A single time-step measured by TROPOMI cannot accurately represent these diurnal patterns. The seasonality of diurnal variations indicates that the strongest diurnal variations occur in fall (see Supplementary Fig. 11), leading to the largest discrepancy in MDA8-O3 estimation between GEMS and TROPOMI (see Supplementary Fig. 4). In the summer, the discrepancy in MDA8-O3 estimation between GEMS and TROPOMI is also significant due to the highest annual MDA8-O3 concentrations, although the diurnal variations are not as pronounced as in fall. In winter, the diurnal variations are larger than in summer, but this is offset by the lower absolute MDA8-O3 concentrations. In spring, the discrepancy in MDA8-O3 estimation between GEMS and TROPOMI is the smallest of the year due to the weakest diurnal variations across all three types of sites.

The hourly retrieval with GEMS data plays a prominent role in subsequent analyses of O₃-associated exposure and health effects, showing a considerable reduction in O₃-related mortalities nationwide, as previously discussed. Detailed analysis suggests more complex transitions at the grid cell level. Although the dominant trend indicates an overall overestimation in TROPOMI estimations, as grid cells originally identified as heavily O₃-polluted moved to moderate and light pollution levels (see Supplementary Fig. 12), some grid cells originally identified as light or moderate pollution shifted to heavier pollution levels. This implies that, in certain situations across all seasons, the original TROPOMI estimations also underestimated O₃ exposure and related health risks, which need to pay more attention for human health protection. In addition, we demonstrate the importance of using new GEMS data to accurately represent O3 exposure by applying the existing exposure-risk function to estimate O3 health risk. It has great potential to refine the exposure-risk function when multiple years of GEMS data become available, establishing more accurate correlations between O3 exposure and associated health risks. Overall, this study is crucial for advancing both environmental and public health research, providing a robust framework for more accurate O3 monitoring and health risk assessment, and offering valuable insights to guide policy and promote environmental equity globally.

Methods

Geostationary and polar-orbit satellite datasets

The Korean GEMS was launched aboard South Korea’s Geostationary Korea Multi-Purpose Satellite 2 (GEO-KOMPSAT-2) in Feb, 2020 with the mission to monitor the atmospheric composition in Asia-Pacific. The satellite is playing a pivotal role in the air monitoring as the first geostationary satellite for air quality. The satellite has the field of view of 5000 km × 5000 km and with the viewing coverage of 5°S–45°N and 75°E–145°E. The spectral range of 300–500 nm and high spectral resolution of 0.6 nm facilitates the observation of multiple trace gas species, including NO2 and HCHO. The nominal spatial resolution of observations of trace gases is 3.5 km × 7.7 km for these gases56. In this study, we utilize the available hourly GEMS L2 products of NO2, HCHO and UV index to retrieve the surface O3 concentration. The products are obtained from the Korean Environmental Satellite Center website (https://nesc.nier.go.kr/)36. For polar-orbit satellite observations, the Tropospheric Ozone Monitoring Instrument (TROPOMI) satellite instrument, which is commissioned by the European Space Agency (ESA) onboard Sentinel-5p, serves as the advanced sensor to measure the trace gases and creates daily-level maps of atmospheric species. We obtain the NO2 and HCHO products from Copernicus Sentinel-5P data center57,58. TROPOMI-UV dataset is obtained from Sodankylä National Satellite Data Centre59.

ECMWF meteorological and auxiliary datasets

The ground-level meteorological datasets are retrieved from the ERA5-Land reanalysis products with spatial resolution of 0.10° × 0.10°, produced by the European Centre for Medium-range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF). The utilized datasets include the variables of 2 m surface temperature (ST), 2 m dewpoint temperature (DT), surface pressure (SP), U-component wind speed (UW), V-component wind speed (VW), total precipitation (TP), total evaporation (TE). ERA5 pressure-level reanalysis product also provides variable of relative humidity and the interpolated slice at surface pressure is denoted as RH.

Based on the empirical knowledge and previous studies, a set of auxiliary variables are involved to demonstrate the temporal and geological characteristics in the model, which include elevation (EL), Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), hour of the day (HH) and day of the year (DOY). The Landsat Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) is obtained from MODIS, which provides 16-days global NDVI product with 250 m spatial resolution (MOD13A3). This data is then aggregated to monthly mean values and upscaled to 0.05° resolution by averaging. Elevation data is obtained from the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) and upscaled to 0.05° resolution by averaging. The correlations of these variables are shown in Supplementary Fig. 13. The model also incorporates socio-economic variables including population and road density, which have been used incorporated in previous studies14. Population data with a 1 km by 1 km spatial resolution is obtained from Worldpop and integrated in the GEMS grids60). The road density, obtained from the Open Street Map (https://osm.mapplus.cn/), is employed as an indicator of the distribution of mobile pollutant emission. The road density is calculated for each grid based on the length of the roads, without consideration of their width, and is expressed as the ratio of the total road length in the grid to the grid area.

The classification of urban, semi-urban and rural regions is based on the land use cover from the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MCD12Q1), which observes 17 types of land use type61. In this study, a grid (0.05° resolution) is classified as “urban” if more than 75% of its area is covered by urban land use. Grids with less than 15% urban land use are classified as “rural”. A 50 km buffer zone is created around each urban area, and grids within this buffer are classified as “suburban”, provided they do not meet the criteria for urban or rural classification.

Ground-level O3 from monitoring sites

The in-situ measurements of surface O3 during the study period (unit: μg/m3) are obtained from 1672 monitoring sites operated by China National Environmental Monitoring Center. Multiple air quality data can be retrieved from the monitoring sites, including PM2.5, PM10, SO2, NO2, O3, CO and AQI. In order to retrieve the hourly ground-level O3 concentration, the hourly observation corresponding to the satellite scanning time is used as the training label of the model. For example, the scanning period ranging from 0645UTC to 0715UTC would be matched to the monitored O3 concentration at 3 pm Beijing Time (UTC + 8). It is noticeable that the monitored surface O3 concentration is higher in eastern China, and the monitoring sites are distributed much denser in eastern China compared to western China.

Retrieval of hourly ground-level O3 concentration

All datasets are collocated into grids of 0.05° ×0.05° and matched to the coordinates by the inverse distance weighting (IDW) interpolation. The temporal period covers from November 2022 (when access to the GEMS dataset became available) to December 2023. The complete dataset has a consistent spatial resolution (0.05° ×0.05°) and temporal resolution (hourly) with diverse spatial coverage associated with the valid satellite scanning. The statistics of the descriptive variables used for machine learning is given in Supplementary Table 3.

In this study, we selected the LightGBM model to retrieve the hourly-level surface O3 concentration, which has the advantages of excellent performance in dealing with large-volume datasets and non-linearity associated with the complex O3 photochemistry. The scheme of the surface O3 retrieval is depicted in Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 14.

As a highly efficient ML-model based on the Gradient Boosting Decision Tree, the LightGBM has been widely applied owing to its advantages of low computation cost and high learning accuracies, especially when processing large and complex datasets62. Given the large volume of the hourly-level and high spatial coverage of satellite samples for model training, LightGBM is considered the most suitable tool due to greatly reduced computation processing time and high accuracy. The LightGBM model can be expressed as (1).

The hyperparameters of the LightGBM model were optimized using a grid search strategy, where various combination of hyperparameters were tested in batches. The best combination of hyperparameters was selected based on the results of batch tests, which is summarized in Supplementary Table 4. LightGBM has also been widely acknowledged to capture the non-linear relationship between features and labels. Thus, to forecast the hourly O3 concentration when no satellite observations are available (mostly, after 15:00), the satellite observations in the morning hours are used as input features, under the assumption that there is a lag time for O3 concentrations to equilibrate with its precursors. Therefore, the forecast LightGBM model can be expressed as (2), where t represents hours when satellite observations are available within the target day.

The selection of the satellite products as model input features is considered on both model evaluation and O3 photochemistry. For instance, tropopheric NO2, though more associated with the O3 formation than total NO2 column, demonstrated poorer model performance compared with total NO2 column, likely due to uncertainties associated with the stratosphere-troposphere separation process (detailed in Supplementary Text 1). Similarly, tropospheric O3 profiles from GEMS would not enhance the model accuracy (detailed in Supplementary Text 4). As for UVI, the erythemal satellite product is selected from the four GEMS-observed types of UV products because it exclusively covers wavelengths between 340 and 400 nm, which align with the spectrum most likely to correspond to the quantum yield of NO2 photolysis which is initiated by the UV irradiance to produce excited oxygen atoms and thereby accelerating the catalytic cycle for O3 formation (detailed in Supplementary Text 3).

Based on the hourly-level O3 concentration estimations, the daily-level MDA8 O3 concentration can be calculated accordingly. To make comparisons with estimations based on the polar-orbit sensor TROPOMI, we have utilized daily-level MDA8-O3 estimation based on TROPOMI observations, which have the overpass time to be around 2 pm in each day. The TROPOMI-based O3 concentration model can be expresses as (3).

Model validation

The performance of the hourly ground-level O3 concentration is validated under the cross-validation schemes. As conventional approach to evaluate the model performance, 10-fold sample-based cross-validation randomly splits the dataset into training set and the testing set with the proportion of 90% and 10%, respectively. Then this process is repeated for 10 times until all samples have been designated as the testing set. With different setups of sample splitting standards, the 10-fold cross-validation are utilized to evaluate the model performance in multiple aspects. As a baseline, the sample based 10-fold cross-validation completely splits the datasets randomly. The site-based cross-validation randomly chooses grids instead of samples as training set or testing set to evaluate the spatial discrepancy of the model. When a grid is designated for the testing, all samples within the grid are labeled as the testing set. It should be noted that the space-based O3 data is averaged to the 0.05-degree grid cell to avoid overfitting if more than one site are existing in a 0.05° grid. Similarly, we setup the hour-based cross validation by randomly selecting samples within the testing hour. All samples within the testing hours are used to evaluate the model trained by datasets in the training hours.

Two common metrics are selected to evaluate the model performance, i.e., coefficient of determinant (R2) and root mean square error (RMSE), as expressed below:

where n is the number of samples; i represents the sample number; O3,meas denotes the measured O3 concentration at monitoring sites, O3,mod denotes the retrieved O3 concentration by the model.

The hourly-level O3 estimations comprise two aspects: firstly, the hourly estimations based on the corresponding satellite observations in the hour; and secondly, the hourly estimations inferred from satellite observations previous in the day. GEMS covers only specific hours within a day, but the O3 concentration can still be interpolated by the delayed O3 formation from the O3 precursors. This means that it is still possible to obtain the hourly-level O3 concentrations in the hours when GEMS are not able to observe. Supplementary Fig. 15 comprehensively validates the observed (09:00–16:00) and the forecasted (17:00–20:00) O3 concentration from the geostationary satellite, with respect to the ground-based monitoring sites under 10-fold sample-based validation. The model with concurrent satellite observations is accurate throughout the day (R2 ranges from 0.84 to 0.94), with the highest model accuracy occurring at 13:00 and 14:00. The root mean squared error ranges from 10.64 μg/m3 to 13.44 μg/m3. This model accuracy shows diurnal patterns consistent with the O3 concentration patterns, implying the photochemical indicators would play vital roles in estimating O3 concentration when O3 photochemistry is active. The forecasted O3 concentrations show inferior accuracy compared with the retrieved O3 (R2 ranges from 0.86 to 0.92, RMSE ranges from 13.06 μg/m3 to 15.22 μg/m3). Forecasted O3 at 20:00 shows the least accuracy, which is attributable to the weakest relation to the model input (temporally ranging 09:00–16:00). The validation result strong supports that ultraviolet-channel-based GEMS shows reliable competence in retrieving the hourly-level O3 concentration.

Apparently, detailed spatiotemporal variations of O3 has been well captured by geostationary satellite estimated by machine learning and satellite-based photochemical precursors. The coverage of the surface O3 concentration is in accordance with the satellite sensing ranges. The mapping indicates the hotspots of O3 pollution, whose occurrence tends to concentrate starting from 14:00. Noticeable spatial patterns of hotspots are demonstrated, as in eastern China rapid growth and decline of O3 pollution can be observation, while in western China O3 pollution would be more persistent even until 20:00. MDA8-O3 is subsequently calculated by the hourly O3 maps. Supplementary Fig. 16 depicts the center hour of the maximum 8 h, indicating a regional variance of O3 diurnal patterns, which suggests that direct retrieval of MDA8-O3 would be less reliable. Supplementary Fig. 2 also indicates a clear diurnal pattern can be depicted from the satellite observations. The exceedance would preserve until nighttime (20:00), when more than 10% territory still suffers from the pollution. Further, the O3 estimation model would apparently identify the seasonal variation of O3 and generates accurate O3 concentration despite of different photochemical regimes (Supplementary Fig. 17).

The hourly-level O3 estimations would surpass the existing O3 concentration retrievals by expanding the temporal resolutions. In Supplementary Figs. 18 and 19 we demonstrate that the diurnal patterns of O3 would show variations seasonally and regionally. O3 tends to vary significantly in warm seasons, when high pollution events are likely to occur. Therefore, the proposed model would provide additional details for monitoring and controlling O3 pollution. The photochemical property of O3 would not only impact the concentration seasonally and regionally, but also affect the performance of the retrieval of O3 concentration by GEMS and TROPOMI. The contribution of photochemical features (UVI, NO2 and HCHO) to O3 concentration estimation were further analyzed using the SHapley Additive exPlanation (SHAP) method, which quantifies the importance of features in the model63,64. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 20, UVI ranks as the 3rd most important O3 precursors, following temperature and hour of the day. NO2 column and HCHO also exhibit considerable levels of importance in estimating O3 concentration. However, socioeconomic factors such as road density and population were found to have a limited impact on model performance, likely because this information is already captured by the GEMS satellite observations. The impact of the bias and uncertainty of satellite observations (NO2, HCHO and UV) on the model performance is investigated using a Monte-Carlo-based perturbation method by generating synthetic satellite datasets. These datasets are derived using a correction method that produces statistically representative samples based on satellite-site validation results, as clarified in Supplementary Text 1–4.

Comprehensive validations, including site-based and hour-based cross-validations, were conducted to demonstrate that the proposed model reduced its reliance on spatial and temporal information from monitoring sites. This enables the model to more effectively capture the photochemical associations between O3 concentration and its precursors (as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 21). Furthermore, excluding the satellite observations of UVI, NO2 and HCHO leads to a significant reduction in model accuracy, as shown by the site-based and hour-based validations (Supplementary Figs. 22 and 23). This suggests that O3 characteristics cannot be accurately extracted from time, spatial, or meteorological features alone without satellite observations.

Assessing the O3-associated premature deaths

We estimate premature respiratory mortality attributable to short-term and long-term O3 exposure using the following equation (Eq. (6)), which has been widely used to estimate annual O3-related mortality44.

Where ER refers to the increased relative risk of cause-specific (disease d) attributable to the change of O3 concentration, \(\Delta {{{\rm{Mort}}}}\) is the excess death due to O3 exposure, BMR is the baseline mortality rate of disease d, pop is the resident populated in the calculated region, β is the concentration response factor which indicates a 10 μg/m3 increase in MDA8-O3 (daily for short-term and annual average for long-term), c is the O3 concentration in a specific metrics, \({c}_{0}\) is the baseline concentration that causes O3-associated health effect. As with any study of air pollution impacts, the quantification of the premature mortalities is sensitive to the specific choice of concentration-response function. To prevent systemic errors in disparate studies, cross-sectional comparisons of data on O3-induced fatalities across different indicators were solely made from the same study. In this study, we obtained the β from Sun’s research (MDA8, for each season)44 for short-term O3 risks assessment and Turner’s research for long-term O3 risk analysis5. It is important to note that, the O3-associated risks are primarily significant during the warm seasons (April to October) as indicated in previous studies45,65 our analysis focused exclusively on addressing O3 risks during this period. The baseline O3 concentration is selected to be 65 μg/m3 based on health studies in China and the WHO guideline66,67. To maintain the consistency with the health assessment in China, selection of baseline mortality rate of specific disease and the population distribution, are obtained in the China National Disease Surveillance Points (DSP) and by Worldpop, respectively.

Both mortalities by retrievals based on GEMS and TROPOMI are calculated based on the O3 short-term risk of mortality from random-effects meta-analysis and large-scale prospective study5,44. Using the proposed O3 concentration retrieval model, we generated the mortality maps with a spatial resolution of 0.05° × 0.05° (as shown in Supplementary Fig. 24) based on Eq. (7). Since mortality is typically assessed on a provincial scale or national scale, provincial statistics (calculated by summing all grids within each province) are provided and compared in this study.

The contrast of O3 exceedance in rural and urban regions shows difference trends in short-term and long term. For short-term O3 exposure, the urban-rural contrast is discovered to be less significant, as the overestimation in urban regions (20.1%) is higher than in rural regions (15.3%). On the contrary, for long-term O3 exposure, urban-rural contrast is underestimated, as the overestimation level of O3 exceedance in urban regions (2.1%) is significantly lower than in rural regions (9.1%). It should be noted that, even though the long-term O3 exceedance shows much less deviations in urban and rural regions, the associated health risks are greatly extended, mainly due to the higher response factor of long-term health risks than short-term risks. Therefore, it suggests that, compared with long-term risks, short-term O3 risks would be more sensitive to O3 concentration trends.

Data availability

The GEMS satellite datasets are retrieved via https://nesc.nier.go.kr/. The site-monitored ozone concentration is obtained from https://quotsoft.net/air/. The meteorological datasets are downloaded from https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/. The generated hourly-level ozone concentration is available at: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.2653799868. Figures containing maps are based on the standard map with the drawing review No. GS (2016) 1600 downloaded from the Ministry of Natural Resources of China. The basemap is not modified.

Code availability

The data of hourly-level ozone generated based on GEMS used in this study are available in the database under accession code at https://zenodo.org/records/1494764069.

References

Anenberg, S. C., Horowitz, L. W., Tong, D. Q. & West, J. J. An estimate of the global burden of anthropogenic ozone and fine particulate matter on premature human mortality using atmospheric modeling. Environ. Health Perspect. 118, 1189–1195 (2010).

Ghude, S. D. et al. Premature mortality in India due to PM2. 5 and ozone exposure. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 4650–4658 (2016).

Hamade, A. K., Misra, V., Rabold, R. & Tankersley, C. G. Age-related changes in cardiac and respiratory adaptation to acute ozone and carbon black exposures: interstrain variation in mice. Inhalation Toxicol. 22, 84–94 (2010).

Nawahda, A. et al. Premature mortality in Japan due to ozone. Atmos. Environ. 81, 538–545 (2013).

Turner, M. C. et al. Long-term ozone exposure and mortality in a large prospective study. Am. J. Respir. Crit. care Med. 193, 1134–1142 (2016).

Malashock, D. A. et al. Global trends in ozone concentration and attributable mortality for urban, peri-urban, and rural areas between 2000 and 2019: a modelling study. Lancet 6, e958–e967 (2022).

Mousavinezhad, S., Choi, Y., Pouyaei, A., Ghahremanloo, M. & Nelson, D. L. A comprehensive investigation of surface ozone pollution in China, 2015–2019: Separating the contributions from meteorology and precursor emissions. Atmos. Res. 257, 105599 (2021).

Wang, Y. et al. Sustained emission reductions have restrained the ozone pollution over China. Nat. Geosci. 16, 967–974 (2023).

Dong, L. et al. Joint features random forest (JFRF) model for mapping hourly surface PM2. 5 over China. Atmos. Environ. 273, 118969 (2022).

Fioletov, V. et al. Application of OMI, SCIAMACHY, and GOME‐2 satellite SO2 retrievals for detection of large emission sources. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 118, 11,399–311,418 (2013).

Ma, Z. et al. Satellite-based spatiotemporal trends in PM2. 5 concentrations: China, 2004–2013. Environ. Health Perspect. 124, 184–192 (2016).

Song, G. et al. Surface UV-assisted retrieval of spatially continuous surface ozone with high spatial transferability. Remote Sens. Environ. 274, 112996 (2022).

Wang, Y., Yuan, Q., Li, T., Tan, S. & Zhang, L. Full-coverage spatiotemporal mapping of ambient PM2. 5 and PM10 over China from Sentinel-5P and assimilated datasets: Considering the precursors and chemical compositions. Sci. Total Environ. 793, 148535 (2021).

Wang, W., Liu, X., Bi, J. & Liu, Y. A machine learning model to estimate ground-level ozone concentrations in California using TROPOMI data and high-resolution meteorology. Environ. Int. 158, 106917 (2022).

Yang, Q. et al. Mapping PM2. 5 concentration at a sub-km level resolution: A dual-scale retrieval approach. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 165, 140–151 (2020).

Zhan, Y. et al. Satellite-based estimates of daily NO2 exposure in China using hybrid random forest and spatiotemporal kriging model. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 4180–4189 (2018).

Xing, J. et al. Modeling study on the air quality impacts from emission reductions and atypical meteorological conditions during the 2008 Beijing Olympics. Atmos. Environ. 45, 1786–1798 (2011).

Cheng, N. et al. Ground ozone concentrations over Beijing from 2004 to 2015: Variation patterns, indicative precursors and effects of emission-reduction. Environ. Pollut. 237, 262–274 (2018).

Wang, P. et al. Responses of PM2. 5 and O3 concentrations to changes of meteorology and emissions in China. Sci. Total Environ. 662, 297–306 (2019).

Kang, Y. et al. Estimation of surface-level NO2 and O3 concentrations using TROPOMI data and machine learning over East Asia. Environ. Pollut. 288, 117711 (2021).

Xu, J. et al. Remote sensing of tropospheric ozone from space: progress and challenges. J. Remote Sens. 4, 0178 (2024).

Jin, X., Fiore, A. M. & Cohen, R. C. Space-based observations of ozone precursors within California wildfire plumes and the impacts on ozone-NO x-VOC chemistry. Environ. Sci. Technol. 57, 14648–14660 (2023).

Souri, A. H. et al. Unraveling pathways of elevated ozone induced by the 2020 lockdown in Europe by an observationally constrained regional model using TROPOMI. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 21, 18227–18245 (2021).

Zhao, F. et al. Ozone profile retrievals from TROPOMI: Implication for the variation of tropospheric ozone during the outbreak of COVID-19 in China. Sci. Total Environ. 764, 142886 (2021).

Cheng, L. et al. Regionalization based on spatial and seasonal variation in ground-level ozone concentrations across China. J. Environ. Sci. 67, 179–190 (2018).

Liu, R. et al. Spatiotemporal distributions of surface ozone levels in China from 2005 to 2017: A machine learning approach. Environ. Int. 142, 105823 (2020).

Finlayson-Pitts, B. & Pitts, J. Jr Atmospheric chemistry of tropospheric ozone formation: scientific and regulatory implications. Air Waste 43, 1091–1100 (1993).

Haagen-Smit, A. J., Bradley, C. & Fox, M. Ozone formation in photochemical oxidation of organic substances. Ind. Eng. Chem. 45, 2086–2089 (1953).

Crutzen, P. J. Photochemical reactions initiated by and influencing ozone in unpolluted tropospheric air. Tellus 26, 47–57 (1974).

Dohan, J. & Masschelein, W. The photochemical generation of ozone: Present state–of–the–art. Ozone 9, 315–334 (1987).

David, L. M. & Nair, P. R. Diurnal and seasonal variability of surface ozone and NOx at a tropical coastal site: Association with mesoscale and synoptic meteorological conditions. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 116, D10303 (2011).

Fishman, J., Watson, C. E., Larsen, J. C. & Logan, J. A. Distribution of tropospheric ozone determined from satellite data. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 95, 3599–3617 (1990).

Chen, B. et al. Estimation of near-surface ozone concentration and analysis of main weather situation in China based on machine learning model and Himawari-8 TOAR data. Sci. Total Environ. 864, 160928 (2023).

Wang, Y., Yuan, Q., Zhu, L. & Zhang, L. Spatiotemporal estimation of hourly 2-km ground-level ozone over China based on Himawari-8 using a self-adaptive geospatially local model. Geosci. Front. 13, 101286 (2022).

Zhang, Y., Wang, W., He, J., Jin, Z. & Wang, N. Spatially continuous mapping of hourly ground ozone levels assisted by Himawari-8 short wave radiation products. GIScience Remote Sens. 60, 2174280 (2023).

Kim, J. et al. New era of air quality monitoring from space: geostationary environment monitoring spectrometer (GEMS). Bull. Am. Meteorological Soc. 101, E1–E22 (2020).

Lange, K. et al. Validation of GEMS tropospheric NO2 columns and their diurnal variation with ground-based DOAS measurements. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 17, 6315–6344 (2024).

Yang, L. H. et al. Interpreting geostationary environment monitoring spectrometer (GEMS) geostationary satellite observations of the diurnal variation in nitrogen dioxide (NO2) over East Asia. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 24, 7027–7039 (2024).

Lee, G. T. et al. First evaluation of the GEMS formaldehyde product against TROPOMI and ground-based column measurements during the in-orbit test period. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 24, 4733–4749 (2024).

Gödeke, J. et al. Hourly surface nitrogen dioxide retrieval from GEMS tropospheric vertical column densities: Benefit of using time-contiguous input features for machine learning models. EGUsphere 2024, 1–47 (2024).

Theys, N. et al. Atmospheric HONO observed over global biomass burning regions using satellite observations of TROPOMI and GEMS. ESS Open Archive (2024).

Park, J., Choi, Y., Jung, J., Lee, K. & Yeganeh, A. K. First top-down diurnal adjustment to NOx emissions inventory in Asia informed by the Geostationary Environment Monitoring Spectrometer (GEMS) tropospheric NO2 columns. Sci. Rep. 14, 24338 (2024).

Bell, M. L. & Dominici, F. Effect Modification by Community Characteristics on the Short-term Effects of Ozone Exposure and Mortality in 98 US Communities. Am. J. Epidemiol. 167, 986–997 (2008).

Sun, Q. et al. Acute effect of multiple ozone metrics on mortality by season in 34 Chinese counties in 2013–2015. J. Intern. Med. 283, 481–488 (2018).

Sun, H. Z. et al. Cohort-based long-term ozone exposure-associated mortality risks with adjusted metrics: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Innovation 3, 100246 (2022).

Yang, C. et al. Alternative ozone metrics and daily mortality in Suzhou: the China Air Pollution and Health Effects Study (CAPES). Sci. Total Environ. 426, 83–89 (2012).

Nelson, D. et al. A comprehensive approach combining positive matrix factorization modeling, meteorology, and machine learning for source apportionment of surface ozone precursors: Underlying factors contributing to ozone formation in Houston, Texas. Environ. Pollut. 334, 122223 (2023).

Xing, J. et al. Mimicking atmospheric photochemical modeling with a deep neural network. Atmos. Res. 265, 105919 (2022).

Li, S. & Xing, J. DeepSAT4D: Deep learning empowers four-dimensional atmospheric chemical concentration and emission retrieval from satellite. Innov. Geosci. 2, 100061 (2024).

Chen, X., Shao, S., Tian, Z., Xie, Z. & Yin, P. Impacts of air pollution and its spatial spillover effect on public health based on China’s big data sample. J. Clean. Prod. 142, 915–925 (2017).

Lin, H. et al. Assessing drivers of coordinated control of ozone and fine particulate pollution: Evidence from Yangtze River Delta in China. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 96, 106840 (2022).

Zoogman, P. et al. Tropospheric emissions: Monitoring of pollution (TEMPO). J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf. 186, 17–39 (2017).

Helbich, M. et al. Sleep problems mediate the association between outdoor nighttime light and symptoms of depression and anxiety: A cross-sectional, multi-city study in Bulgaria. Environ. Res. 263, 119897 (2024).

Oak, Y. J. et al. A bias-corrected GEMS geostationary satellite product for nitrogen dioxide using machine learning to enforce consistency with the TROPOMI satellite instrument. EGUsphere 2024, 1–19 (2024).

Xia, N., Du, E., Guo, Z. & de Vries, W. The diurnal cycle of summer tropospheric ozone concentrations across Chinese cities: Spatial patterns and main drivers. Environ. Pollut. 286, 117547 (2021).

Seo, S. et al. Diurnal variations of NO2 tropospheric vertical column density over the Seoul metropolitan area from the Geostationary Environment Monitoring Spectrometer (GEMS): seasonal differences and the influence of the a priori NO2 profile. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 18, 115–128 (2025).

Di, Q. et al. Assessing PM2.5 Exposures with High Spatiotemporal Resolution across the Continental United States. Environ. Sci. Technol. 50, 4712–4721 (2016).

Dong, L. C., Li, S. W., Yang, J., Shi, W. X. & Zhang, L. Investigating the performance of satellite-based models in estimating the surface PM2.5 over China. Chemosphere 256, 127051 (2020).

Lindfors, A. V. et al. The TROPOMI surface UV algorithm. AMT 11, 997–1008 (2018).

Stevens, F. R., Gaughan, A. E., Linard, C. & Tatem, A. J. Disaggregating census data for population mapping using random forests with remotely-sensed and ancillary data. PloS One 10, e0107042 (2015).

Friedl, M. A. et al. MODIS Collection 5 global land cover: Algorithm refinements and characterization of new datasets. Remote Sens. Environ. 114, 168–182 (2010).

Ke, G. et al. Lightgbm: A highly efficient gradient boosting decision tree. Proc. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 30, 3146–3154 (2017).

Lundberg, S. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. Proc. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 30, 4768–4777 (2017).

Shapley, L. S. A value for n‐person games. In: Contribution to the Theory of Games 2 (Princeton University Press, 1953).

Zhang, Y. et al. Respiratory mortality associated with ozone in China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ. Pollut. 280, 116957 (2021).

Fu, G. et al. The synergistic effect of high temperature and ozone on the number of deaths from circulatory system diseases in Shijiazhuang, China. Front. Public Health 11, 1266643 (2023).

Xue, T. et al. New WHO global air quality guidelines help prevent premature deaths in China. Natl Sci. Rev. 9, nwac055 (2022).

Song, G. Hourly-level ozone concentration retrieved by GEMS and relative analysis on model accuracy and environmental implications. figshare. Dataset. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.26537998 (2025).

Song, G. Unraveling Overestimated Exposure Risks Through Hourly Ozone Retrievals from Next-Generation Geostationary Satellites. ARSgesong/hourly_ozone_model. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14947640 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by The National Natural Science Foundation of China [NO: 42375131]. The authors are grateful to the GEMS science team for providing GEMS NO2, HCHO and UV products.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

These authors contributed equally to this paper: L.S., S.G. L.S.: Conceptualization, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing- Reviewing and Editing. S.G.: Methodology, Investigation, Model Development, Formal analysis, Writing- Original draft preparation, Writing- Reviewing and Editing. X.J.: Supervision, Writing- Reviewing and Editing. D.J.X.: Methodology, Model Development, Formal analysis. Z.M.L.: Methodology, Model Development, Formal analysis, Writing- Reviewing and Editing. F.C.Y.: Formal analysis. M.S.Y.: Model Development, Formal analysis. Y.J.: Writing- Reviewing and Editing. D.L.C.: Writing- Reviewing and Editing. G.W.: Writing- Reviewing and Editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Wenhao Wang and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, S., Song, G., Xing, J. et al. Unraveling overestimated exposure risks through hourly ozone retrievals from next-generation geostationary satellites. Nat Commun 16, 3364 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-58652-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-58652-2

This article is cited by

-

Effects of ozone pollution on crops and human health: evidence from the “2 + 36” cities of Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei and surrounding regions, China

Air Quality, Atmosphere & Health (2025)