Abstract

Developing highly active, low-cost, and durable catalysts for efficient oxygen reduction reactions remain a challenge, hindering the commercial viability of proton exchange membrane fuel cells (PEMFCs). In this study, an ordered PtZnFeCoNiCr high-entropy intermetallic electrocatalyst with Pt antisite point defects (PD-PZFCNC-HEI) is synthesized. The electrocatalyst shows high mass activity of 4.12 A mgPt-1 toward the oxygen reduction reaction (ORR), which is 33 times that of the commercial Pt/C. PEMFC, assembled with PD-PZFCNC-HEI as the cathode (0.05 mgPt cm-2), exhibits a peak power density of 1.9 W cm-2 and a high mass activity of 3.0 A mgPt-1 at 0.9 V. Theoretical calculations combined with in situ X-ray absorption fine structure results reveal that defect engineering optimizes Pt’s electronic structure and activates non-noble metal site active centers, achieving exceptionally high ORR catalytic activity. This study provides guidance for the development of nanostructured ordered high-entropy intermetallic catalysts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Oxygen reduction reactions (ORRs) find wide applications in proton exchange membrane fuel cells (PEMFCs), metal-air batteries, organic synthesis, and environmental protection technologies1,2,3,4,5,6. However, the lack of efficient ORR catalysts significantly hinders their practical application2,6,7,8,9,10,11. In recent decades, the primary technology blueprint for ORR catalysts has involved the development of highly active and durable Pt-based catalysts to expedite the sluggish ORRs12. Alloying Pt with other transition metals with face-centered cubic-type solid-solution structures optimizes the surface electronic structure of Pt–M (M = Fe, Mn, Ni, Ti, Cr, etc.), improves its electrocatalytic performance, and reduces the consumption of Pt metals, lowering the cost of fuel cells13,14,15,16,17,18. However, Pt–M alloys are prone to preferential leaching of metal element M, due to the high electrochemical potential of the cathode ORR, especially in acidic media, leading to a decrease in electrocatalytic stability and fuel cell performance19. Therefore, it is necessary to explore new approaches to achieving high activity and stability of ORR catalysts.

High-entropy intermetallics electrocatalysts have enhanced thermodynamic stability and corrosion resistance because of the high-entropy effect generated by the entropy enhancement of mixed configurations16,20,21,22,23,24,25. In high-entropy intermetallics, each lattice site has a different lattice potential energy, and the formation and migration enthalpies of vacancies at different lattice sites are different, leading to the hysteresis diffusion effect of elements in high-entropy alloys and enhancing the high-temperature mechanical strength26,27,28. On the other hand, the kinetically controlled metal diffusion process results in various types of defects in alloys29,30. The presence of defects induces stress due to lattice mismatch, which can affect the surface electronic structure and the adsorption ability toward adsorbates31,32. To date, the synthesis of intermetallic nanocrystals with controlled defect structures remains challenging, partly due to the complex growth and ordering processes33,34. Conversely, the presence of hysteresis diffusion effect in high-entropy intermetallic compounds further increases the likelihood of generating various defects35,36,37. Although significant progress has been made in controlling the particle size and exposed activity facets of high-entropy intermetallic catalysts16,38,39,40, research on defect design and growth control, which have a significant impact on catalyst activity, has not yet been reported. Ordered intermetallics are thermodynamically more stable than disordered solid solutions, but to achieve the transition from disorder to order, it is necessary to cross the kinetic energy barrier of atomic order41. Therefore, the preparation of intermetallics usually requires heating above 600 °C, which can lead to particle growth and aggregation42,43. Moreover, at high temperatures, intermetallics tend to become more ordered, which makes the controllable preparation of ultrafine high-entropy intermetallics with defects challenging.

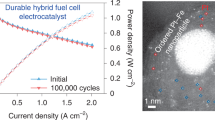

In this study, we report a PtZnFeCoNiCr high-entropy intermetallic electrocatalyst (PD-PZFCNC-HEI) with Pt antisite defects. The effects of the carbon support and pore-confinement on the intermetallic nanoparticles were studied. The sluggish diffusion effect in high-entropy intermetallics enables controllable formation of Pt antisite defects by tuning the heat-treatment temperature. Due to the synergistic effects involving the regulation of Pt electronic structure and the formation of multiple active sites, the as-prepared PD-PZFCNC-HEI exhibits superior ORR performance. It achieves an ORR mass activity of 4.12 A mgPt−1 in a half-cell, which was 33 times that of the commercial Pt/C. The PEMFC constructed with the PD-PZFCNC-HEI cathode attains a peak power density of 1.9 W cm−2, demonstrating a mass activity of up to 3.0 A mgPt−1 at 0.9 V. This significantly exceeds the US DOE 2025 target (0.44 A mgPt−1). After undergoing a 30k-cycles accelerate stability test (AST), it exhibits a minimal voltage decay of 14 mV at 0.8 V. This study provides a unique approach for investigating high-entropy intermetallic compounds as ORR catalysts.

Results and discussion

Material synthesis and characterizations

The carbon support pore-confined reduction method was used to prepare the target products, as detailed in Supplementary Note 1, to achieve the feasibility of synthesizing PD-PZFCNC-HEIs. All diffraction peaks of the PD-PZFCNC-HEI sample obtained at an optimized temperature of 800 °C can be indexed as a face-centered tetragonal ordered intermetallic structure with a P4/mmm space group (Fig. 1a). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images show that the average diameter of the as-prepared PD-PZFCNC-HEI particles is 1.726 nm (measured standard deviation is 0.025 nm) with a uniform distribution (Figs. S8 and 1b, c), which aligns with the pore size distribution of the carbon support resulting from the pyrolysis of the ZIF-8 (denoted as Zn-DPCN), indicating that pore-confinement suppresses particle growth. The reference sample (PZFCNC-XC72) prepared at 800 °C using XC72 as the support showed the same crystal structure as the PD-PZFCNC-HEI, but the average particle size is up to 7.6 nm and the particle size distribution is uneven (Figs. S9 and S10).

a X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern of PD-PZFCNC-HEI; b Transmission electron microscopy images of PD-PZFCNC-HEI; c Particle size distribution histogram of PD-PZFCNC-HEI; d High-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy images of PD-PZFCNC-HEI nanoparticle; The corresponding atomic-resolution STEM-EDS mapping of e Pt, f Zn, g Fe, h Co, i Ni, and j Cr; k Line-scan profile of the PD-PZFCNC-HEI nanoparticle along the green line in (d); l, m Corresponding local structure image; Quantitative analysis on compressive and tensile strains within dislocation cores along n line 1 and o line 2 in (m), respectively; Strain distributions of p εyy and q εxx by geometric phase analysis base on (d).

The composition of PD-PZFCNC-HEI was determined by inductively coupled plasma‒mass spectrometry to be Pt0.5022Zn0.2235Ni0.058Co0.0617Fe0.0857Cr0.0688. The energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) mapping results confirm the presence of six elements on a single particle (Figs. 1e–j and S27). The selection of non-precious metal constituents is based on a comprehensive consideration of the atomic radii, formation enthalpy, and reported ORR activity of each component, aiming to obtain highly active high-entropy intermetallic compounds44,45,46,47,48. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) reveals distinct signals of the 0-valent metal species of each element (Fig. S11). The peaks at 71.8, 1021.7, and 575.7 eV correspond to the signals of the metal states Pt0, Zn0, and Cr0, respectively. The fitting results of the Fe 2p spectrum reveal five components, with the first peak positioned at 710.9 eV, corresponding to the metallic state of iron, and the second peak located at 713.5 eV, indicative of the Fe³⁺ oxidation state. This fitting analysis thoroughly accounts for its multiplet splitting structure. The three lines within the energy range 713–720 eV are due to the multiplet splitting phenomenon and the last line, called shake-up at 715 eV, additionally points out Fe3+49. The Ni 2p spectrum is fitted with four components, with the first peak centered at 852.4 eV representing the metallic part of Ni and lines in the range from 855 to 861 eV indicate Ni2+ oxidation states49. The chi-square values for the fitting results of Pt, Zn, Fe, Co, Ni, and Cr are 0.4638, 0.801, 0.0069, 0.79, 0.64, and 0.1932, respectively, indicating relatively high fitting quality50.

X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES) spectra shows that the intensity of the “white line” (WL) at the Pt L3-edge is consistent with that of Pt foil and significantly lower than that of PtO2, indicating that Pt is in a metallic state, whereas the k-edge of Co, Fe, Ni, Zn, and Cr is generally close to their respective metallic states with slight shifting towards higher energy (Figs. 2a–d and S12a, b). The extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) results for all elements show strong metal-metal coordination peaks, further indicating they primarily exist in the metallic state (Figs. 2e–h and S13a, b). These results confirmed the successful reduction of each metallic element. The small energy deviation between the k edges of Co, Fe, Ni, Zn, and Cr and their respective metal states could be related to the ligand effects that exist within the high-entropy intermetallics and the charge transfer between the transition metals and the support51,52,53,54. Wavelet transform (WT) analysis of EXAFS indicates the presence of metal-nitrogen (M–N) coordination bonds (Figs. 2i–k and S14–S18)55,56,57,58,59, which was confirmed by the metal-nitrogen (M–N) bonds at 399.8 eV observed by XPS result of PD-PZFCNC-HEI (Figs. 2l and S19). The strong coordination bonding between the high-entropy intermetallics nanoparticles and support leads to a slight increase in the metal valence state, which is advantageous for suppressing migration and agglomeration at high temperatures.

L3-edge XANES spectra of a Pt, and K-edge XANES spectra of b Co, c Fe, and d Ni in the PD-PZFCNC-HEI nanoparticles (the embedded images correspond to the local magnified views of the corresponding regions); EXAFS spectra of e Pt, f Co, g Fe, h Ni elements; WT-EXAFS plots of i Co foil, j CoO, and k PD-PZFCNC-HEI for Co element; l X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy spectra collected at the N 1s edges for the PD-PZFCNC-HEI sample.

High-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM) was used to study the atomic structure of PD-PZFCNC-HEI. Spots with higher contrast correspond to heavy Pt atoms, whereas lower-intensity spots represent randomly distributed lighter transition metal atoms M (M: Zn, Fe, Co, Ni, and Cr) because the intensity of the images is correlated with the atomic number. The characteristic atomic-resolution image of individual nanoparticles along the [010] zone axis (Fig. 1d) shows interplanar spacings of 1.864 and 1.931 Å, corresponding to the (002) and (200) crystal planes, respectively. Moreover, a small amount of high-contrast Pt atoms is dispersed within the lower-contrast non-precious metal layer (As indicated by the red dashed line). Similar phenomena can also be observed in other crystal axes, such as [110], [1–10] and [221] (Fig. S20). This suggests that a small amount of Pt has migrated into positions typically occupied by non-noble metals, resulting in Pt antisite defects. These defects may influence the material’s structure and properties, particularly in catalytic reactions. Notably, Pt antisite defects were observed in Pt-based intermetallic catalysts. Decreasing the reduction reaction temperature below 700 °C results in a solid-solution structure (Figs. S21 and S22). However, the reference sample obtained at a temperature of 900 °C, labeled as PZFCNC-HEI (900), exhibits similarly ordered atomic arrangement with an average particle size of 2.2 nm, but lacks the Pt antisite defects observed in the other samples (Fig. S23). In addition, the reference sample prepared at 700 °C, denoted as PZFCNC-HEA (700), shows no apparent structural ordering (Fig. S24), with an average particle size of 1.66 nm. Therefore, it can be concluded that 800 °C is the optimal temperature for forming high-entropy intermetallics with antisite defects, as it provides a balance between the thermodynamic driving force for ordering and the diffusion energy barriers of defects. This outcome underscores the correlation between the formation of Pt antisite defects in PD-PZFCNC-HEI and the reaction temperature, attributed to the sluggish component diffusion effects inherent in high-entropy intermetallics. When transitioning from a disordered state at 700 °C to an ordered state at 800 °C, some Pt atoms do not diffuse to the Pt site of the intermetallics and remain at the non-noble metal site because of the larger size of the Pt atoms compared to the transition metal atoms, resulting in the formation of intermetallics with Pt antisites. The line-scan profiles along the green line in Fig. 1a provide additional evidence for the antisite distribution of the Pt atoms, as shown in Fig. 1k. Along the wide green lines, Pt generally exhibits a periodic distribution trend; however, a small amount of Pt occupies non-noble metal sites, such as the weak peak between the two Pt peaks.

The FT-EXAFS spectrum was analyzed to extract local structural information. Due to the ultrasmall size of our nanoparticles, which results in a low signal-to-noise ratio in the absorption spectra, the fitting primarily focused on the first coordination shell peaks of PZFCNC-HEI (Fig. S25) and PD-PZFCNC-HEI (Fig. S26). The fitting results (Table S2) demonstrate that the average coordination number (CN) of the first shell of Pt in PD-PZFCNC-HEI is ~8, with a Pt–M (M: non-noble metal) coordination number of 3.5 and a Pt–Pt coordination number of 4.5. These findings further support the successful formation of a face-centered tetragonal (fct) ordered intermetallic structure in PFCNCZ-HEI60. Considering the functional relationship between the “growth curve” of CN and the size of nanoparticles, this CN value implies that the average particle size of PFCNCZ-HEI nanoparticles is less than 2 nm61. Most importantly, the Pt–M coordination number in PD-PZFCNC-HEI (3.5) is slightly lower than that in PZFCNC-HEI (3.8), while the Pt–Pt coordination number in PD-PZFCNC-HEI (4.5) is significantly higher than in PZFCNC-HEI (4.0). This suggests that Pt antisite defects occupy some non-precious metal atomic sites, leading to an increase in the Pt–Pt coordination number in PD-PZFCNC-HEI, which macroscopically supports the presence of Pt antisite defects in PD-PZFCNC-HEI. On the other hand, the Pt–Pt bond length in PD-PZFCNC-HEI (2.70 Å) is slightly shorter than in PZFCNC-HEI (2.71 Å), further verifying the presence of Pt antisite defects, as the larger radius of the Pt defects compared to non-precious metals induces local compressive strain, thereby reducing the average Pt–Pt bond length.

Fig. 1n, o shows the calculated results of compressive and tensile strains along lines 1 and 2 in Fig. 1m, respectively, derived from the variation in the atomic column spacing. Notably, the PD-PZFCNC-HEI nanoparticles exhibited significant compressive and tensile strains, which were attributed to the lattice distortion effects arising from differences in atomic sizes and the presence of antisite defects. Furthermore, the corresponding geometric phase analysis (GPA) was calculated to further analyze the distribution of surface stress (Fig. 1p, q). The color legend delineates the varying degrees of strain, with yellow to white corresponding to the tensile strain and brown to black corresponding to the compressive strain. The contour plot of the strain component εyy demonstrates that the compressive and tensile strains are spatially coupled and exhibit a periodic distribution, ensuring the stability of the overall structure of the nanoparticles. Simultaneously, the contour plot of the strain component εxx also confirmed the presence of spatially coupled compressive-tensile strains induced by lattice distortion and antisite defects.

Oxygen reduction driven by antisite defect

The synthesized PD-PZFCNC-HEI was used to study the influence of antisite defects on ORR performance by rotating disk electrode measurements in a 0.1 M HClO4 electrolyte at room temperature. The PD-PZFCNC-HEI with antisite defects exhibits a remarkably high half-wave potential (E1/2) of up to 0.948 V vs. reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE), surpassing that of the PZFCNC-HEI sample without antisite defects (0.926 V), commercial Pt/C (0.86 V), solid-solution sample PZFCNC-HEA (0.892 V), and PZFCNC-XC72 (0.81 V) (Figs. 3a and S28). The Pt mass activity of PD-PZFCNC-HEI at 0.90 V is up to 4.12 A mgPt−1, which is 33 times higher than that of commercial Pt/C catalyst (0.126 A mgPt−1) (Fig. 3b), surpassing PZFCNC-HEI sample without antisite defects (1.78 A mgPt−1), the solid-solution sample PZFCNC-HEA (0.713 A mgPt−1), and PZFCNC-XC72 (0.69 A mgPt−1), and ranks top in the reported ORR catalysts (Table S3). The Tafel slope for the PD-PZFCNC-HEI (62 mV dec−1) is notably lower than that of Pt/C (78 mV dec−1), signifying the superior ORR kinetics of PD-PZFCNC-HEI (Fig. S29). Based on the cyclic voltammetry curves shown in Figs. S30 and S31, the electrochemical active surface area (ECSA) of PD-PZFCNC-HEI and commercial Pt/C catalyst are calculated to be 70.3 and 68.3 m2 gPt−1, respectively. Furthermore, its ECSA normalized specific activity is 5.6 mA cm−2, representing a 31-fold improvement compared to Pt/C (Fig. S32). The Koutecky-Levich plots shown in Fig. S33, which are derived from the data at different rotation rates (Fig. 3c), exhibit a well-defined and nearly parallel linear relationship. The electron transfer number (n) for the PD-PZFCNC-HEI is calculated to be ~4.0 (Fig. 3d), indicating its efficient four-electron mechanism.

a ORR polarization curves of the PD-PZFCNC-HEI, PZFCNC-HEA, and commercial 20 wt% Pt/C catalysts in O2-saturated 0.1 M HClO4 solution at 1600 rpm; b Mass activities at 0.9 V vs. reversible hydrogen electrode; c Polarization curves of PD-PZFCNC-HEI at different rotation rates; d Charge transfer number of PD-PZFCNC-HEI. e Normalized chronoamperometric curves of the PD-PZFCNC-HEI and Pt/C catalysts tested at a constant potential of 0.7 V; Polarization curves of f PD-PZFCNC-HEI and g Pt/C after AST between 0.6 and 0.95 V at different cycle numbers; h Mass activity before and after AST; The I–V polarization curves and power density of the H2–O2 fuel cell of the (i) PD-PZFCNC-HEI and j Pt/C sample with the cathode Pt loading of 0.05 mgPt cm−2 before and after AST. k Long-term stability of the H2-Air fuel cell with PZ-PZFCNC-HEI as the cathode at a current density of 500 mA cm−2.

Stability is a prerequisite for practical applications of catalyst. Chronoamperometric measurements at 0.7 V shows (Fig. 3e) that the retention rate of the PD-PZFCNC-HEI catalyst after continuous oxygen reduction for 100000 s is 90.1%, which is significantly higher than that of Pt/C (only 36%). The defect-free PZFCNC-HEI sample (prepared under 900 °C) also delivers an 87% retention rate after testing, which is attributed to the exceptional structural stability of the high-entropy intermetallic (Fig. S34). An accelerate stability test (AST) was employed to further assess the long-term electrocatalytic durability of PD-PZFCNC-HEI within the range of 0.6–1.1 V. After 20,000 cycles of AST, PD-PZFCNC-HEI shows only a 7 mV E1/2 decay (Fig. 3f), which is significantly lower than that of commercial Pt/C, which exhibits a negative shift of 107 mV (Fig. 3g). Following 20,000 cycles, PD-PZFCNC-HEI maintains an impressive 89.0% of its initial mass activity, significantly surpassing that of the commercial Pt/C, which only retains 45.6% (Fig. 3h). Furthermore, STEM observation of the PD-PZFCNC-HEI sample after AST testing still exhibits high particle dispersibility, as shown in Fig. S35a. Meanwhile, an ordered intermetallic compound structure and prominent Pt antisite defects can also be observed (Fig. S35b). In addition, after the AST testing, the PD-PZFCNC-HEI sample still retains a relatively high configurational entropy (Tables S4 and S5). This further corroborates the outstanding structural stability of PD-PZFCNC-HEI during the electrochemical process. Moreover, no significant elemental segregation is observed post-cycling in the STEM-EDS mapping results of the PD-PZFCNC-HEI nanoparticle (Fig. S36). These results collectively confirm the elevated catalytic durability of PD-PZFCNC-HEI.

Fuel cell membrane electrode assembly applications

Fuel cell membrane electrode assemblies (MEAs) performance and durability. The PD-PZFCNC-HEI catalyst was used as the cathode in the fabrication of MEAs to validate its superior ORR activity. Subsequently, the actual performances of the H2–O2 and H2-Air fuel cells are evaluated by testing them in a PEMFC. The composition of the PEMFC is shown in Figs. S41 and S42. PD-PZFCNC-HEI or 20 wt% Pt/C was employed as the cathode and 20 wt% Pt/C was used as the anode. Figure S43 shows the I–V polarization curves and power density of the H2–O2 fuel cell for the PD-PZFCNC-HEI and Pt/C at an O2 pressure of 2.0 bar, with a cathode Pt loading of 0.05 mgPt cm−2. The open-circuit voltage of PD-PZFCNC-HEI reaches 0.98 V, indicating a high intrinsic ORR activity during fuel cell operation. The peak power density reached 1.9 W cm−2, surpassing that of Pt/C at 1.34 W cm−2. In particular, the mass activity at 0.9 V reaches 3.0 A mgPt−1, and the Pt mass-normalized rated power is up to 38 W mgPt−1, significantly exceeding the 2025 US Department of Energy (DOE) target (Table S6) and the state-of-the-art ORR catalysts reported in current literature (Table S7)62. It also demonstrates significant application advantages compared to other HEIs in the same field (Table S8). Even under H2-Air conditions, it can exhibit a maximum power density of 0.652 W cm−2, as illustrated in Fig. S44. In contrast, Pt/C achieved maximum power densities of only 1.33 and 0.555 W cm−2 under H2–O2 and H2-Air conditions, respectively.

Following the AST protocol established by the U.S. DOE, a potential cycling from 0.6 to 0.95 V was also conducted on the MEA to assess the stability of the PEMFC under operational conditions. After the 30k-cycles AST, PD-PZFCNC-HEI still exhibits a mass activity of 2.2 A mgPt−1 (at 0.9 V) and a voltage decay of 14 mV at 0.8 A cm−2, meeting the DOE 2025 target (mass activity > 0.26 A mgPt−1 and voltage loss <30 mV after 30k cycles, Fig. 3i, Table S7). Additionally, after the 30k AST cycle, the peak power density of PD-PZFCNC-HEI only declined by 0.014 W cm−2 under H2-Air condition (Fig. S45). In contrast, after 30k AST cycles, the open-circuit voltage of Pt/C significantly decreased under both H2–O2 and H2-Air conditions, dropping below 0.9 V, as shown in Figs. 3j and S46. Additionally, the stability of the MEA prepared with the PD-PZFCNC-HEI catalyst was further evaluated by constant current testing at 500 mA cm−2 (Fig. 3k). After continuous operation for 50 h, the voltage loss in the PEMFC was negligible. These results demonstrated the excellent structural stability of the PD-PZFCNC-HEI catalyst under practical conditions.

Insights into the oxygen reduction mechanism

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed to gain insight into the superior ORR performance of the PD-PZFCNC-HEI. Initially, a series of defect-free PtZnFeCoNiCr intermetallic compound (PZFCNC-HEI) models were constructed based on the P4/mmm space group (Fig. S47). We selected Fig. S47a, which has the lowest energy, as the reference model for defect-free PZFCNC-HEI (Fig. S48). Based on this model, we constructed antisite defect models by sequentially replacing each outermost non-noble metal atom with a Pt atom (Figs. S49 and S50). After optimization, the most stable antisite defect model, PD-PZFCNC-HEI, formed by Pt substitution at the Zn site, was selected as a case for analysis (Figs. 4b and S49a). A pure Pt (111) surface model is also constructed as a reference (Fig. 4a). Comparing the projected partial densities of states of the Pt d-band, it can be observed that the Pt d-band center (−2.247 eV) of PD-PZFCNC-HEI is 0.069 eV (Fig. 4f) lower than that of antisite defect-free PZFCNC-HEI (−2.178 eV) and 0.303 eV lower than that of Pure Pt (−1.944 eV). This disparity may be attributed to the interactions between the elements in the high-entropy intermetallic compounds, which generate surface electron transfer that widens the d-band electron region of the surface Pt (Fig. 4c), especially the presence of large atomic radius Pt antisite defects, inducing compressive strain and adjusting the d-band center of Pt (Fig. 4l). Overall, the presence of Pt defects results in further compression of the Pt d-band electrons, causing the Fermi level to rise and consequently lowering the Pt d-band center. The downward shift of the d-band center helps reduce the adsorption energy of Pt–O, thereby enhancing the reactivity of the reaction.

The top and side views of the a Pt (111) and b PD-PZFCNC-HEI (111) surface models; c The number of outer electrons in the surface atoms of PD-PZFCNC-HEI and the corresponding pure metal from Bader charge analysis; Partial density of states (PDOS) of the d-band for the surface Pt atoms in d Pt (111), e PZFCNC-HEI, and f PD-PZFCNC-HEI surface; The free energies of intermediates of g Pt-PtCoNiPtPtZn and h Zn-CrPtPtPtPtPt sites on the PD-PZFCNC-HEI surface for the ORR steps; COHP and ICOHP for *OH adsorption intermediates at i Pt (111), j the Pt-PtCoNiPtPtZn, and k the Zn-CrPtPtPtPtPt sites on PD-PZFCNC-HEI; l Variation of Pt d-band structure with compressive strain.

The Gibbs free energies of the intermediate products were calculated to elucidate the ORR mechanism. Given that the interaction between the high-entropy intermetallic surface and oxygen-containing intermediates is characterized by multi-metal synergistic coupling rather than single-metal adsorption54, the sites on the PD-PZFCNC-HEI surface are denoted as Mc–M1M2M3M4M5M6, representing a central metal atom (Mc) and six adjacent metal atoms (M1–M6). At an equilibrium potential of 1.23 V vs. RHE, the rate-limiting step for the reaction pathway of *O at the top site on Pt(111) is the hydrogenation of O2 to form the *OOH intermediate with a ΔG of 0.406 eV (Fig. S51). The rate-determining energy barriers for the bridge and hollow sites are 1.0517 eV (Fig. S52a) and 1.053 eV (Fig. S52b), respectively. Similarly, the rate-limiting step at the Pt-PtCoNiPtPtZn site on the PD-PZFCNC-HEI surface is also the O2 hydrogenation step, corresponding to a ΔG value of 0.381 eV (Fig. 4g), which is lower than the rate-limiting steps of all Pt (111) surface reaction pathways. Moreover, the integrated projection of the crystal orbital Hamiltonian population values (ICOHP) of the Pt–*OH bond of the Pt-PtCoNiPtPtZn (Fig. 4j) and Zn-CrPtPtPtPtPt (Fig. 4k) sites on the PD-PZFCNC-HEI surface were calculated to be 0.535 and 0.507, respectively, both lower than the value of 1.270 for Pt (111) (Fig. 4i). This indicates that the optimization of d-band electrons further influences the interaction with oxygen-containing intermediates. Additionally, the ease of O–O bond breaking in the *OOH intermediate largely determines whether the active site undergoes a four-electron or a two-electron reaction. The O–O bond length in the *OOH intermediate on the PD-PZFCNC-HEI is longer than that on Pt (111) (Fig. S53), and the charge density between the O–O bonds on *OOH at the PD-PZFCNC-HEI surface sites is notably lower than that on the Pt (111) surface (Fig. S54), indicating a greater tendency for *OOH to undergo O–O bond cleavage rather than hydrogenation to form hydrogen peroxide. Notably, even for non-noble metal sites, such as the Zn-CrPtPtPtPtPt site, the energy barrier for the rate-limiting step is only 0.363 eV (Fig. 4h), which is lower than that of Pt (111). To our knowledge, Zn is not typically considered a highly active element in the ORR. However, it was activated as a highly active site in PD-PZFCN-HEI. These results suggest that multiple active sites may exist on the PD-PZFCNC-HEI surface.

In situ, XAFS measurements under electrochemical operating conditions further precisely identify the multi-active site characteristics of the PD-PZFCNC-HEI (Figs. 5a and S59). Figure 5b, e shows the Pt L3-edge and Zn K-edge XANES spectra of the PD-PZFCNC-HEI, respectively. The XANES spectra at all applied voltages retained their primary features, especially for the position of the WL and the second near-edge oscillation, indicating that the prepared PD-PZFCNC-HEI maintained high stability during the reaction. When the operating voltage reaches 1.1 V, the WT peak signal of the Pt L3-edge reaches its maximum (Fig. 5c), indicating an increase in Pt 5d empty orbitals, attributed to the adsorption of oxygen at the Pt sites. This result also demonstrates that Pt sites exhibit a high onset potential and elevated reaction activity. As the potential decreased, the increase in the number of species resulting from oxygen reduction and hydrogenation led to a decrease in the intensity of the Pt L3 edge WT peak. The Zn K-edge exhibits a similar phenomenon, where the WT peak gradually decreases with decreasing voltage (Fig. 5d, e). This finding indicates that the Zn sites also directly undergo oxygen adsorption and participate in the redox reactions. The in situ XAFS results strongly support the DFT calculation results, confirming that the PD-PZFCNC-HEI surface features multiple ORR reaction sites.

a Diagram of electrochemical cell for in situ XAFS measurements in fluorescence mode; b In situ Pt L3-edge XANES spectra of PD-PZFCNC-HEI at different voltage (the embedded images correspond to the local magnified view); Contour plots of the white lines at the c Pt L3 edge and d Zn K-edge; e In situ Zn K-edge XANES spectra of PD-PZFCNC-HEI at different voltage (the embedded images correspond to the local magnified view).

Discussion

In summary, we successfully used a spatial confinement strategy to design and synthesize an innovative ultrasmall PD-PZFCNC-HEI with an ordered superstructure and Pt antisite defects (average size of 1.7 nm). Compared to state-of-the-art Pt/C catalysts, the PD-PZFCNC-HEI catalyst exhibited significant advantages, including superior mass activity (33 times higher than that of commercial Pt/C) and enhanced stability, making it an ideal choice for ORR catalysts under acidic conditions. Moreover, it achieves a power density of 1.9 W cm−2 in practical fuel cells and demonstrates a top-tier performance in PEMFCs with a mass activity of 3.0 A mgPt−1 at 0.9 V voltage. Furthermore, the high activity of the PD-PZFCNC-HEI was revealed through a combination of theoretical calculations and experimental results. Specifically, the presence of Pt antisite defects induces compressive strain, further modulating the Pt d-band electrons. Additionally, the activation of non-precious metal sites promotes the formation of multiple active sites. The synergistic interplay between these factors significantly enhanced the ORR activity of the PD-PZFCNC-HEI. The outstanding performance of the PD-PZFCNC-HEI for the ORR serves as reference frames for the study of the structure-activity relationship of high-entropy intermetallic catalysts through defect engineering. This work provides guidance for the design of other ordered HEI catalysts with breakthrough performance and accelerates research on ordered HEI in energy-related applications.

Methods

Materials

Zinc (II) nitrate hexahydrate and methanol were obtained from Aladdin. H2PtCl6·6H2O and 5 wt% Nafion were purchased from Alfa Aeser. Commercial 20 wt% Pt/C was sourced from Johnson Matthey, HiSPEC 3000, and its composition was determined using ICP-AES and chemical elemental analysis. 2-methylimidazole, Co(acac)2, Fe(acac)3, Ni(acac)2, and Cr(acac)3 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. All the experiments were conducted using ultrapure water (Millipore, 18.23 MΩcm)

Synthesis of Zn-DPCN

Typically, 1.118 g of zinc (II) nitrate hexahydrate (Beijing Tongguang Fine Chemical Company, AR) and 1.232 g of 2-methylimidazole (Sigma-Aldrich, AR) were dissolved in two separate methanol solutions. After 30 min of magnetic stirring, the two solutions were mixed and stirred continuously at room temperature for 24 h. The precipitate was collected by centrifugation, washed at least thrice with methanol, and dried at 70 °C in a vacuum oven for 10 h. The precursors are designated as ZIF-8, subsequently ZIF-8 was heated at a temperature of 900 °C in a tube furnace under Ar/H2 flow for 3 h to obtain the Zn-DPCN, and then the products were treated in 0.5 M H2SO4 for 1 h to remove partially unstable zinc. The samples were then washed until the pH was neutral, collected by centrifugation, and dried to obtain the pretreated Zn-DPCN support.

Synthesis of PD-PZFCNC-HEI

Considering that Pt is the optimal catalytic element for ORR, our research aims to reduce the amount of platinum and enhance its catalytic activity through high-entropy alloying based on Pt. The selection of non-precious metals requires consideration of elements that can be alloyed with Pt and subsequently converted into intermetallic compounds with Pt. In addition, the selected elements ideally have similar atomic radii to alleviate lattice distortion effects in the resulting high-entropy alloy. Importantly, if the selected non-precious metal also exhibits favorable ORR catalytic activity, it would be advantageous. In light of these criteria, we opted for Zn, Fe, Co, Ni, and Cr, as these elements have been reported to possess high ORR activity and are amenable to alloying with Pt. In detail, to begin with, Co(acac)2, (Sigma-Aldrich, AR) Fe(acac)3, (Sigma-Aldrich, AR) Ni(acac)2, (Sigma-Aldrich, AR) Cr(acac)3, (Sigma-Aldrich, AR) and H2PtCl6·6H2O (Sigma-Aldrich, AR) were dissolved in a 20 mL mixture of water and alcohol in a certain proportion. The Pt mass in this mixture was maintained at ~8 wt% of the final total mass. Subsequently, 25 mg of the Zn-DPCN support was dispersed in the solution and ultrasonicated for half an hour. The suspension was magnetically stirred at 70 °C to evaporate the solvent. The resulting thick slurry was then transferred to an oven and left overnight to ensure complete drying. After grinding in an agate mortar, the powder was alloyed and annealed at 800 °C for 4 h under H2/Ar atmosphere. Following treatment with a 0.1 M HClO4 solution for half an hour, centrifugation and overnight drying were conducted to obtain PD-PZFCNC-HEIs. For the synthesis of the PD-PZFCNC-XC72 reference sample, all other conditions were kept the same, except for the replacement of Zn-DPCN with an equivalent amount of XC72. Similarly, for the PZFCNC-HEA reference sample, all other conditions were maintained except for the final calcination temperature of 600 °C.

Characterization

Inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy (ICP-AES) measurements were performed on a Prodigy 7 ICP-AES system. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) data were acquired using a VG ESCALAB MKII spectrometer with a Mg Kα X-ray source. The X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis was conducted using a Bruker D8 Focus XRD instrument, employing Cu Kα radiation at a scanning speed of 1° per minute. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) observations were carried out with a JEOL 2010F microscope operating at an acceleration voltage of 200 kV. The K-edge spectra of Fe, Co, Ni, Cr, and Zn, as well as the Pt L3-edge spectra, were collected in fluorescence mode at beamline 1W2B of the Beijing Synchrotron Radiation Facility, utilizing a Si (111) double-crystal monochromator. For high-resolution scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) imaging, energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) mapping, and line-scan analysis, a Cs-corrected FEI Titan Themis Z microscope was utilized, operating at 300 kV with a convergence semi-angle of 25 mrad, and equipped with a probe SCOR spherical aberration corrector. The XANES and extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) data were processed and analyzed using the ATHENA software package.

Electrochemical measurements

Electrochemical measurements were conducted using a CHI 760E electrochemical workstation in a standard three-electrode configuration. The working electrode consisted of a glassy carbon rotating disk electrode (4 mm diameter), while a Hg/HgSO4 electrode and a Pt wire served as the reference and counter electrodes, respectively. To prepare the catalyst ink, 2 mg of the carbon-supported catalyst was uniformly dispersed in a solution containing 490 µL of isopropanol, 490 µL of deionized water, and 20 µL of Nafion (5 wt%) under ultrasonication for 30 min. Subsequently, 2 µL of the homogeneous ink was drop-cast onto the glassy carbon electrode and allowed to dry at room temperature. Cyclic voltammetry (CV) was performed in N2-saturated 0.1 M HClO4 electrolyte at a scan rate of 50 mV s−1. Oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) polarization curves, corrected for iR drop (E - iR), were recorded in O2-saturated 0.1 M HClO4 (pH = 1.0 ± 0.1) at a scan rate of 10 mV s−1. Accelerated durability tests (ADT) were carried out by cycling the potential between 0.6 and 1.1 V for 10,000 cycles at 200 mV s−1. All measured potentials were converted to the reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE) scale using the equation: E(RHE) = E(Hg/HgSO4) + 0.652 + 0.05916 × pH. The electrochemical surface area (ECSA) was calculated following a previously reported method. Notably, the capacitive behavior of Pt/C and PD-PZFCNC-HEI was found to be nearly identical63.

Computational details

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations were carried out using the Vienna ab initio Simulation Package (VASP)64. The electron-ion interactions were modeled using projector-augmented wave (PAW) potentials, while the exchange-correlation interactions were described by the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) functional within the generalized gradient approximation (GGA)65,66,67. A plane-wave cutoff energy of 500 eV was employed, and the convergence thresholds for energy and forces were set to 10−5 eV and 0.02 eV/Å, respectively. To minimize interactions between periodic images, a vacuum layer of 15 Å was introduced in the slab models. The Brillouin zone integration was performed using a k-point grid with a spacing of 0.08 Å−1. Van der Waals (vdW) interactions were accounted for using the DFT-D3 dispersion correction method68. Additionally, spin polarization effects were included in all calculations. Source data are provided as a Supplementary Data 1 file.

The high-entropy model was constructed using Python’s pymatgen and random modules by randomly replacing the Fe sites in the PtFe (111) surface structure. Specifically, we first determined the atomic numbers and quantities of atoms in the optimized PtFe (111) surface structure. Based on the elemental ratios obtained from experimental characterization (Pt:Cr:Fe:Co:Ni:Zn = 1:0.137:0.171:0.123:0.115:0.445), we calculated the number of atoms to be replaced for each of the five elements (Cr, Fe, Co, Ni, Zn). We then used the random module to generate a random array of these five elements and employed pymatgen methods to perform the element substitution in the PtFe (111) surface structure, aiming to simulate the disordered distribution of multiple elements in a high-entropy structure. Using this random construction method, we generated 10 different (4 × 4 × 4) unit cells, with energy differences less than 0.5 eV, indicating that their distribution has minimal impact on the stability of the bulk structure, as shown in Fig. S47a–j. By further comparing their energies, we selected the structure with the lowest energy, i.e., the thermodynamically most stable structure, to further construct the Pt-defective high-entropy structure. Among them, we selected Fig. S47a, which exhibits the lowest formation energy (−477.76 eV) and is thus the most stable structure, as the PZFCNC-HEI model, with its surface depicted in Fig. S48. Considering the possibility of Pt atom antisite defects replacing any non-noble metal atom, we sequentially constructed Pt antisite defect models by substituting Zn, Fe, Co, Ni, and Cr sites on the PZFCNC-HEI (111) model surface. Since the substitution of different elements results in slight deviations in the number of each element in the defect models, we chose to compare the substitutions of each element separately. For example, since the PZFCNC-HEI surface in Fig. S48 has three Zn atoms at different positions, we replaced each of these Zn atoms with Pt to obtain three different PD-PZFCNC-HEI defect models (Fig. S49a–c). Among these, Fig. S49a exhibited the lowest energy, and thus, we selected it as the representative PD-PZFCNC-HEI defect model (Fig. 4b) with Pt substitution at Zn sites for further calculations. To further validate the advantages of Pt antisite defects, we continued calculations based on the PD-PZFCNC-HEI-2 defect model (Fig. S50a), where Pt replaces Fe to form an antisite defect.

For the density functional theory (DFT) calculations focused on the oxygen reduction reaction (ORR), the associative mechanism following a four-electron pathway was selected. To evaluate the theoretical ORR performance of the relevant slab models, the computational hydrogen electrode (CHE) approach, originally developed by Nørskov and co-workers, was utilized68.

Single fuel cell preparation and test

To prepare the catalyst ink for the 30% Nafion electrodes, the catalyst, deionized water, isopropanol, and a 5 wt% Nafion ionomer solution were mixed under ultrasonication for 1 h. The resulting catalyst slurry was sprayed onto carbon paper to create a cathode catalyst layer with a platinum loading of 0.05 mgPt cm−2. For the anode, a commercial Pt/C catalyst (20 wt% Pt, JM Hispec3000) was used, with a platinum loading of 0.1 mgPt cm−2. The cathode and anode were then hot-pressed onto opposite sides of a Nafion 211 membrane (DuPont) at 120 °C to assemble the membrane electrode assembly (MEA), which had a geometric area of 4 cm2. Fuel cell performance was evaluated using an 850e Fuel Cell Test Station. The reactant gases, H₂ and O₂, were humidified at 80 °C, with flow rates set at 0.6 L min−1 for H₂ and 2.6 L min−1 for O2. The operating pressures were maintained at 1.0 bar for H2 and varied between 0.5 and 2 bar for O2/air.

Data availability

The experiment data which support the findings of this study are presented in this article and the Supplementary Information, and are available from the corresponding authors upon request. The source data underlying Figs. 1–5, Supplementary Figs. 1–59, are provided as a Source Data file. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Debe, M. K. Electrocatalyst approaches and challenges for automotive fuel cells. Nature 486, 43–51 (2012).

Xiao, F. et al. Atomically dispersed Pt and Fe sites and Pt–Fe nanoparticles for durable proton exchange membrane fuel cells. Nat. Catal. 5, 503–512 (2022).

Douglin, J. C. et al. High-performance ionomerless cathode anion-exchange membrane fuel cells with ultra-low-loading Ag–Pd alloy electrocatalysts. Nat. Energy 8, 1262–1272 (2023).

Pivovar, B. Catalysts for fuel cell transportation and hydrogen related uses. Nat. Catal. 2, 562–565 (2019).

Nørskov, J. K. et al. Origin of the overpotential for oxygen reduction at a fuel-cell cathode. J. Phys. Chem. B 108, 17886–17892 (2004).

Greeley, J. et al. Alloys of platinum and early transition metals as oxygen reduction electrocatalysts. Nat. Chem. 1, 552–556 (2009).

Cullen, D. A. et al. New roads and challenges for fuel cells in heavy-duty transportation. Nat. Energy 6, 462–474 (2021).

Ni, W. et al. Synergistic interactions between PtRu catalyst and nitrogen-doped carbon support boost hydrogen oxidation. Nat. Catal. 6, 773–783 (2023).

Xiong, Y. et al. Single-atom Rh/N-doped carbon electrocatalyst for formic acid oxidation. Nat. Nanotechnol. 15, 390–397 (2020).

Chong, L. et al. Ultralow-loading platinum-cobalt fuel cell catalysts derived from imidazolate frameworks. Science 362, 1276–1281 (2018).

Zeng, Y. et al. Tuning the thermal activation atmosphere breaks the activity–stability trade-off of Fe–N–C oxygen reduction fuel cell catalysts. Nat. Catal. 6, 1215–1227 (2023).

Kong, F. et al. Trimetallic Pt–Pd–Ni octahedral nanocages with subnanometer thick-wall towards high oxygen reduction reaction. Nano Energy 64, 103890 (2023).

Xie, M. et al. Pt–Co@Pt octahedral nanocrystals: enhancing their activity and durability toward oxygen reduction with an intermetallic core and an ultrathin shell. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 8509–8518 (2021).

Cui, C., Gan, L., Heggen, M., Rudi, S. & Strasser, P. Compositional segregation in shaped Pt alloy nanoparticles and their structural behaviour during electrocatalysis. Nat. Mater. 12, 765–771 (2013).

Liu, X. et al. Inducing covalent atomic interaction in intermetallic Pt alloy nanocatalysts for high-performance fuel cells. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202302134 (2023).

Yao, Y. et al. High-entropy nanoparticles: synthesis-structure-property relationships and data-driven discovery. Science 376, eabn3103 (2022).

Yao, Y. et al. Carbothermal shock synthesis of high-entropy-alloy nanoparticles. Science 359, 1489–1494 (2018).

Huang, J. et al. Experimental Sabatier plot for predictive design of active and stable Pt-alloy oxygen reduction reaction catalysts. Nat. Catal. 5, 513–523 (2022).

Guo, J. et al. Template-directed rapid synthesis of Pd-based ultrathin porous intermetallic nanosheets for efficient oxygen reduction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 10942–10949 (2021).

Chen, W. et al. High-entropy intermetallic PtRhBiSnSb nanoplates for highly efficient alcohol oxidation electrocatalysis. Adv. Mater. 34, e2206276 (2022).

Dasgupta, A. et al. Atomic control of active-site ensembles in ordered alloys to enhance hydrogenation selectivity. Nat. Chem. 14, 523–529 (2022).

Zhu, G. et al. Constructing structurally ordered high-entropy alloy nanoparticles on nitrogen-rich mesoporous carbon nanosheets for high-performance oxygen reduction. Adv. Mater. 34, 2110128 (2022).

Batchelor, T. A. A. et al. High-entropy alloys as a discovery platform for electrocatalysis. Joule 3, 834–845 (2019).

Chen, T. et al. Symbiotic reactions over a high-entropy alloy catalyst enable ultrahigh-voltage Li–CO2 batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 18, 853–861 (2025).

Feng, G. et al. Engineering structurally ordered high-entropy intermetallic nanoparticles with high-activity facets for oxygen reduction in practical fuel cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 11140–11150 (2023).

Qiao, Z. et al. Atomically dispersed single iron sites for promoting Pt and Pt3Co fuel cell catalysts: performance and durability improvements. Energy Environ. Sci. 14, 4948–4960 (2021).

Tsai, K. Y., Tsai, M. H. & Yeh, J. W. Sluggish diffusion in Co–Cr–Fe–Mn–Ni high-entropy alloys. Acta Mater. 61, 4887–4897 (2013).

Wang, R. et al. Effect of lattice distortion on the diffusion behavior of high-entropy alloys. J. Alloy. Compd. 825, 154099 (2020).

Wang, K. et al. Kinetic diffusion–controlled synthesis of twinned intermetallic nanocrystals for CO-resistant catalysis. Sci. Adv. 8, eabo4599 (2022).

Wang, R. M. et al. Layer resolved structural relaxation at the surface of magnetic FePt icosahedral nanoparticles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 017205 (2008).

Wang, Y., Han, P., Lv, X., Zhang, L. & Zheng, G. Defect and interface engineering for aqueous electrocatalytic CO2 reduction. Joule 2, 2551–2582 (2018).

Huang, H. et al. Understanding of strain effects in the electrochemical reduction of CO2: using Pd nanostructures as an ideal platform. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 3594–3598 (2017).

Li, Z.-A. et al. Chemically ordered decahedral FePt nanocrystals observed by electron microscopy. Phys. Rev. B 89, 161406 (2014).

Chi, M. et al. Surface faceting and elemental diffusion behaviour at atomic scale for alloy nanoparticles during in situ annealing. Nat. Commun. 6, 8925 (2015).

Chen, Y. et al. Pt atomic layers with tensile strain and rich defects boost ethanol electrooxidation. Nano Lett. 22, 7563–7571 (2022).

Zhao, S. Lattice distortion in high-entropy carbide ceramics from first‐principles calculations. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 104, 1874–1886 (2021).

Wang, Y. et al. Enhancing properties of high-entropy alloys via manipulation of local chemical ordering. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 180, 23–31 (2024).

Feng, G. et al. Sub-2 nm ultrasmall high-entropy alloy nanoparticles for extremely superior electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 17117–17127 (2021).

Sun, Y. & Dai, S. High-entropy materials for catalysis: a new frontier. Sci. Adv. 7, eabg1600 (2021).

Chen, T. et al. An ultrasmall ordered high-entropy intermetallic with multiple active sites for the oxygen reduction reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 1174–1184 (2024).

Yan, Y. et al. Intermetallic nanocrystals: syntheses and catalytic applications. Adv. Mater. 29, 1605997 (2017).

Shao, M., Peles, A. & Shoemaker, K. Electrocatalysis on platinum nanoparticles: particle size effect on oxygen reduction reaction activity. Nano Lett. 11, 3714–3719 (2011).

Xie, C., Niu, Z., Kim, D., Li, M. & Yang, P. Surface and interface control in nanoparticle catalysis. Chem. Rev. 120, 1184–1249 (2019).

Guan, J. et al. Intermetallic FePt@PtBi core-shell nanoparticles for oxygen reduction electrocatalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 21899–21904 (2021).

Kuttiyiel, K. A. et al. Gold-promoted structurally ordered intermetallic palladium cobalt nanoparticles for the oxygen reduction reaction. Nat. Commun. 5, 5185 (2014).

Ding, H. et al. Epitaxial growth of ultrathin highly crystalline Pt-Ni nanostructure on a metal carbide template for efficient oxygen reduction reaction. Adv. Mater. 34, e2109188 (2022).

Liang, J. et al. Biaxial strains mediated oxygen reduction electrocatalysis on Fenton reaction resistant L10‐PtZn fuel cell cathode. Adv. Energy Mater. 10, 2000179 (2020).

Cui, Z., Chen, H., Zhou, W., Zhao, M. & DiSalvo, F. J. Structurally ordered Pt3Cr as oxygen reduction electrocatalyst: ordering control and origin of enhanced stability. Chem. Mater. 27, 7538–7545 (2015).

Czerski, J. et al. Corrosion and passivation of AlCrFe2Ni2Mox high-entropy alloys in sulphuric acid. Corros. Sci. 229, 111855 (2024).

Ivanova, T., Naumkin, A., Sidorov, A., Eremenko, I. & Kiskin, M. X-ray photoelectron spectra and electron structure of polynuclear cobalt complexes. J. Electron Spectrosc. Relat. Phenom. 156−158, 200–203 (2007).

Tian, X. et al. Engineering bunched Pt-Ni alloy nanocages for efficient oxygen reduction in practical fuel cells. Science 366, 850 (2019).

Li, H. et al. Fast site-to-site electron transfer of high-entropy alloy nanocatalyst driving redox electrocatalysis. Nat. Commun. 11, 5437 (2020).

Zhao, J. et al. Co NP/NC hollow nanoparticles derived from yolk-shell structured ZIFs@polydopamine as bifunctional electrocatalysts for water oxidation and oxygen reduction reactions. J. Energy Chem. 27, 1261–1267 (2018).

Chen, T. et al. PtFeCoNiCu high-entropy solid solution alloy as highly efficient electrocatalyst for the oxygen reduction reaction. iScience 26, 105890 (2023).

Chen, Y. et al. Enhanced oxygen reduction with single-atomic-site iron catalysts for a zinc-air battery and hydrogen-air fuel cell. Nat. Commun. 9, 5422 (2018).

Yuan, B. et al. Synergistic effect of size-dependent PtZn nanoparticles and zinc single-atom sites for electrochemical ozone production in neutral media. J. Energy Chem. 51, 312–322 (2020).

Zheng, W. et al. A universal principle to accurately synthesize atomically dispersed metal–N4 sites for CO2 electroreduction. Nano Micro Lett. 12, 108 (2020).

Pan, T. et al. Amorphous chromium oxide with hollow morphology for nitrogen electrochemical reduction under ambient conditions. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14, 14474–14481 (2022).

Guo, W. et al. In situ revealing the reconstruction behavior of monolayer rocksalt CoO nanosheet as water oxidation catalyst. J. Energy Chem. 70, 373–381 (2022).

Li, J. et al. Fe stabilization by intermetallic L10-FePt and Pt catalysis enhancement in L10-FePt/Pt nanoparticles for efficient oxygen reduction reaction in fuel cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 2926–2932 (2018).

van Bokhoven, J. A. Recent developments in X-ray absorption spectroscopy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 12, 5502–5502 (2010).

Wang, Y. et al. Fundamentals, materials, and machine learning of polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cell technology. Energy AI 1, 100014 (2020).

Sadighi, Z., Liu, J., Zhao, L., Ciucci, F. & Kim, J.-K. Metallic MoS2 nanosheets: multifunctional electrocatalyst for the ORR, OER and Li–O2 batteries. Nanoscale 10, 22549–22559 (2018).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953–17979 (1994).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Grimme, S., Antony, J., Ehrlich, S. & Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 132, 154104 (2010).

Nørskov, J. K. et al. Origin of the overpotential for oxygen reduction at a fuel-cell cathode. Phys. Chem. B 108, 17886–17892 (2004).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Professor Yan Xiang and Master Xinkai Zhang for their contributions to our fuel cells. This work was financially supported by the National Key R&D Program of China under 2022YFB2502100, National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 53130202, No. U22A20419) and Hunan Provincial Natural Science Foundation Project, No. 2025JJ60355. T.C. and X.Z. contribute equally. All support for this research is gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.C. designed the study. X.Z. and Y.X. carried out the fuel cell test. H.W., C.Y., Y.Z., C.G., W.X., Y.Y., J.C., and T.L. helped analyze test results. D.X. supervised the project.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, T., Zhang, X., Wang, H. et al. Antisite defect unleashes catalytic potential in high-entropy intermetallics for oxygen reduction reaction. Nat Commun 16, 3308 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-58679-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-58679-5

This article is cited by

-

Sub-angstrom strain in high-entropy intermetallic boosts the oxygen reduction reaction in fuel cell cathodes

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Nano-Engineered High-Entropy Intermetallic Compounds for Catalysis: From Designs to Catalytic Applications

Electrochemical Energy Reviews (2025)

-

Platinum-based intermetallics for oxygen reduction catalysis: from binary to high-entropy

Catal (2025)