Abstract

Total sea ice extent (SIE) across the Southern Ocean increased from 1979-2014, but declined rapidly after 2016. Significant sea ice decline has emerged since the peak of SIE in 2014, coincident with Pacific sub-decadal sea surface temperature (SST) trends resembling a strong La Niña-like cold condition and the negative phase of the interdecadal Pacific oscillation (IPO). Previous studies suggest that the warm subsurface Southern Ocean was an important driver of the low sea ice in spring 2016 and the sustained low sea ice state since. Here we show that the observed atmospheric circulation changes near Antarctica during the period from June 2013-May 2023 are conducive to increasing surface temperature via warm advection from north and reducing Antarctic SIE, involving a deepening of the Amundsen Sea Low and anomalous high pressures over the Weddell Sea and West Pacific sectors. Through coupled pacemaker experiments, we demonstrate that Pacific sub-decadal SST trends have dominantly driven these atmospheric circulation changes through tropical–polar teleconnections and also induced significant Southern Ocean subsurface warming in the recent decade. The consequent decreasing SIE has enhanced the Southern Ocean subsurface warming effect and significantly contributed to the rapid Antarctic SIE decline.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Satellite observation shows total Antarctic sea ice extent (SIE) had a small positive linear trend during 1979-2014, with large regional variability1. There is evidence that internal decadal variability of the climate system could be responsible for trends of Antarctic sea ice1,2,3,4,5,6. In particular, decadal variability from the tropical Pacific7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14 or tropical Atlantic15,16,17 could play an important role. Some studies also proposed that Southern Ocean freshening and sea surface temperature (SST) cooling trend might have contributed to the observed positive trend before 201414,18,19,20,21,22. After the peak of 2014, Antarctic SIE started to decrease and dramatically dropped to a record low in late 201623,24,25, after which the unexpected low sea ice state persisted for several years, and the SIE reached a new record low in the mid-2023, and remained at, or near, record-low values during ensuing Austral winter and spring26,27. Nearly all regions have experienced significant sea ice loss, particularly in the Weddell Sea (Figs. 1a and S1).

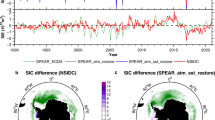

a Seasonal time series of sea ice extent (SIE) in the whole Antarctic from 1979 to December 2023 and the linear trend fit to the 10 years from June 2013 to May 2023 (blue line) is shown. Linear trends of seasonal mean fields in b–e satellite-derived sea ice concentration (SIC) and f–m ERA5 reanalyzed sea level pressure (SLP, interval 1 hPa/decade), 850 hPa wind (UV850), and surface air temperature (SAT) from June 2013 to May 2023. ** in (a) indicates the significant linear trend of SIE at the 95% confidence level. Dotted in (b–e, i–m) and shaded areas in (f–l) indicate the statistical significance of trends of SIC, SLP, and SAT at the 90% confidence level.

These prompt the critical question: What factors have caused the tremendous Antarctic SIE decline since 2014? Recent studies indicate that the decadal-long subsurface Southern Ocean warming associated with the Southern Annular Mode (SAM) and the negative phase of IPO contributed to the sudden Antarctic SIE decline of 2016 and sustained a persistent sea ice decrease since12,26,28,29, and may have caused a regime shift in Antarctic sea ice26. Through numerical simulations, Zhang et al.28 demonstrate that the negative SIE in 2016–2021 corresponds to an overall warm and salty upper ocean and that the SIE declines are preceded by a heat buildup in the subsurface ocean (depths of roughly 100–500 m) and a salinification in the surface ocean before 2016, which tended to destabilize the upper ocean stratification and trigger vertical instabilities. But the subsurface ocean status before 2016 only sustains the overall low states of sea ice, and the tremendous decline of sea ice after 2016 is still largely impacted by the simultaneous atmospheric circulation and ocean variabilities12,28.

This study mainly examines the relative roles of the Pacific sub-decadal SST variations, originating from the evolution of ENSO variations and the shift of the IPO from the positive phase in 2014–2016 to the negative phase after 2016, on Southern Hemisphere (SH) atmospheric changes and Antarctic SIE decline. During 2014–2016, the tropical Pacific experienced persistent warm conditions that included a weak El Niño in 2014 and an extreme El Niño in 2015–2016, while the prolonged 2020–2023 La Niña conditions developed and decayed in autumn 2023. During June 2013–May 2023, the observed SST trend patterns over the Pacific (Figs. 2a, S2a–d) resemble the typical La Niña conditions and the negative phase of the IPO characterized by strong cold conditions in the central-eastern tropical Pacific and large warming in the west-central midlatitude Pacific. The Nino34 SST and raw unfiltered IPO indices show significant downward trends of −1.32 and −1.76 °C/decade from June 2013 to May 2023, respectively (Fig. 2d). The raw IPO has an extremely negative value below −1.5 °C in 2022, indicating that the IPO has very likely transited to negative from a short-lived positive phase during 2015-1630. In each season, significant and persistent SST warming is found over the tropical Atlantic and the high-latitude North and South Atlantic (Fig. S2a–d). Here, we use the Community Earth System Model (CESM1.2) to perform two sets of 100-year coupled pacemaker simulations in which observed trends of SST anomalies over the Pacific and global ocean between 60 °S to 60 °N from June 2013 to May 2023 are added to the model-simulated SST climatology, named the PACTrend and GLTrend experiments, respectively (see “Methods” section). These coupled pacemaker experiments only assimilate prescribed observed SST trend anomalies into the ocean component of the coupled model, and the sea ice component fully responds to atmospheric and ocean variations.

Linear trends of annual mean fields in a ERSSTv5 SST and b CMAP precipitation from June 2013 to May 2023; and c, d pattern of Interdecadal Pacific Oscillation (IPO) and associated raw unfiltered (red line) and low-pass filtered (black line) time series since January 1950, and Nino34 SST index (blue line) since January 1979. Dotted in (a, b) indicate observed values significant at the 90% confidence level. The linear trend of raw, unfiltered IPO index and Nino34 SST index during 2013–2022 are shown in (d) (unit: °C decade−1), with ** indicating the statistical significance at the 95% confidence level. Dark green lines demarcate the area of prescribed Pacific or global pacemaker SSTs in the PACTrend and GLTrend experiments in (a) and in the idealized Pacific pacemaker experiment in (c). Note that the contour interval is 0.2 °C decade−1 in (a) and 0.1 °C in (c).

Results

Observed atmospheric forcing in SIE decline

The atmosphere is an important driver of Antarctic sea ice variability and changes1,6,8,31,32,33,34,35. Figure 1 indicates that changes in atmospheric circulation might have governed the contemporary 10-year trend in SAT and sea ice concentration (SIC) over the Southern Ocean in the chosen time period from June 2013 to May 2023. There is a striking coherence of the trends in SAT and SIC over most areas, where the negative SIC trends are collocated with warming temperature trends, suggesting that the SAT trend largely contributed to sea ice cover trends35. In each season, a deepening of the Amundsen Sea Low (ASL) and high sea level pressure (SLP) anomalies over the Weddell Sea and Western South Pacific are observed, which induce warm SAT trends over the Southern Ocean through warm advection from the north (Fig. 1f–m). Maximum SLP trend values reach −10.0 (6.0), −15.0 (3.0), −9.0 (6.0), and −8.0 (3.0) hPa/decade associated with the deepening ASL (anomalous anticyclonic over the Weddell Sea) in JJA, SON, DJF, and MAM, respectively. Circulation around the ASL promotes southerly flow on its western side and northerly flow on the eastern side, and the intensity and location of the ASL strongly influence surface temperature and sea ice extent in the Southern Ocean31,32,33,34. Strong negative SIC trends over the Weddell–Bellingshausen Seas are consistent with large positive surface temperature trends and warm northwesterly flow associated with enhanced ASL and positive SLP anomalies in the Weddell Sea sector in Austral spring (September–October–November, SON) and summer (December–January–February, DJF) (Fig. 1c, d, g, h), along with warm northerly flow and marked poleward heat flux as a result of a couplet of low and high SLP anomalies that were centered on 90°W and 0° in autumn (March–April–May, MAM) or 140°W and 60°W in winter (June–July–August, JJA) (Fig. 1f, i), respectively. Similarly, sea ice loss and positive temperature trends over the West Pacific and Ross Sea sectors are consistent with warm northwesterly flow associated with high (low)-pressure anomalies over the Western South Pacific (the Antarctic) in Austral summer and spring. Meanwhile, the mechanical effect of the northerly winds would push ice southward, decreasing the SIE and vice versa. In each season, anomalous positive (negative) v-component 850 hPa winds are strongly connected with greater offshore (onshore) flow and sea ice gain (loss)11, but part of the Amundsen-Bellingshausen Sea (ABS) and eastern Ross Sea experienced strong southerly wind and only weak increase in sea ice. This contrasts dramatic sea ice loss over other regions, particularly in the Weddell Sea. During Austral spring (summer), the SLP trend pattern is characterized by strongly (weakly) positive SAM but with considerable zonal asymmetry, which is important in contributing to the sea ice decline31,32,33,34. The greatest warming and SIE loss are observed in the Weddell Sea sector, accounting for over 41% of the total Southern Ocean SIE trend (−1.84 × 106 km2/decade). Figure 1 also shows the concurrence of cold or weak warm SAT and large SIC decline over the eastern Weddell Sea in JJA and vast areas from the Weddell Sea to Ross Sea in DJF, indicating that subsurface warming might have driven the sea ice decline, as will be discussed later.

In all seasons, the 300-hPa geopotential height (Z300) changes over the South Pacific are associated with a negative Pacific South America (PSA)-like Rossby wave train that originates in the tropical Pacific, and the corresponding wave activity flux (WAF) exhibits a distinctive arc-shaped trajectory, extending from the central tropical Pacific toward the ABS region and continuing to the South Atlantic (Fig. S2e–h). Coincident with the trends of the strengthened ASL and negative PSA patterns in the anomalous circulation, tropical Pacific rainfall trends show the La Niña-related dipole-like patterns with strong negative rainfall over the western to central equatorial Pacific in all seasons, and positive rainfall over the Maritime Continent in JJA and SON and northwestern tropical Pacific and the South Pacific convergence zone (SPCZ) in DJF and MAM (Fig. S3). A La Niña condition typically generates a negative PSA teleconnection pattern and deepens the ASL36,37,38, and could also drive a SAM teleconnection in Austral summer17,39,40, while the IPO can affect Antarctic atmospheric circulation through PSA-like Rossby wave trains and SAM teleconnection, with anomalies persisting for decades10,11. Over the tropical Atlantic, there are warming SST and increased precipitation trends, but the precipitation magnitudes are much smaller compared with the equatorial western Pacific or the SPCZ, suggesting that teleconnections from Pacific precipitation anomalies are primarily responsible for observed circulation changes in Figs. 1 and S2.

Modeling impacts of Pacific and global sub-decadal SST trends on SIE decline

We first examine the forcing of Pacific sub-decadal SST trends in atmospheric circulation changes and the rapid decline of Antarctic SIE in the recent decade. In the PACTrend experiment, significant ensemble-mean responses in Fig. 3e–h reproduce major features of observed SLP and UV850 trends, especially the enhanced ASL and positive SLP anomalies over the Weddell Sea and Western South Pacific in all seasons and positive SAM-like teleconnections in SON and DJF. The most noticeable disagreement is that the strengthening of JJA ASL in the observation and simulation are centered at about 135°W and 90°W, respectively. The pattern correlations between observed SLP trend and forced SLP response between 50°S and 90°S are 0.01, 0.68, 0.89, and 0.34 in JJA, SON, DJF, and MAM, respectively. In all seasons, the magnitudes of the ensemble-mean SLP are less than observed trends, mainly due to the ensemble averaging process. Figures S4 and5a–d further indicate that the responses of precipitation, Z300, and associated WAF responses to Pacific SST trends strikingly resemble the corresponding observed trends in Figs. S2 andS3, except for the longitude phase shift (about 45°) between observed and forced Z300 in JJA as in the SLP field. Sub-decadal negative SST anomalies in the tropical Pacific drive enhanced Walker circulation over the tropical Pacific with weakened (enhanced) vertical motion and reduced (increased) convection and rainfall over the equatorial central-eastern Pacific (equatorial western Pacific and SPCZ) in all four seasons (Fig. S4a–d). There is a pair of symmetric cyclones over the Pacific from ~30°N–30°S responding to the cooling tropical Pacific SST in each season, which appears to be quantitively consistent with the simple model solution exhibited by Gill41 (Fig. S5a–d). This convection produces anomalous diabatic heating in the mid-troposphere and accelerates the local Hadley circulation over the western tropical Pacific, forming anomalous convergent flows at the descending branch. There is a large-scale zonally oriented dipole pattern in the tropics with anomalous upper-level divergence (convergence) over the western tropical Pacific and Indian Ocean (the central-eastern Pacific and tropical Atlantic Ocean) in each season (Fig. S6a–d). The resultant subtropical upper-level convergent/divergent anomalies perturb the subtropical jet and generate anomalous Rossby wave sources (RWS)42, which subsequently excite patterns of stationary Rossby waves and influence the SH extratropics15,17,40. Significant positive RWS is found over the subtropical areas from South Indian Ocean and Australia to the western South Pacific in all seasons. The propagation of WAF as indicated by arrows shows a wave train originating from these areas, and a negative PSA teleconnection is clearly seen (Fig. S5a–d), leading to the significant anomalous low over the ASL region (maximum anomaly −3.5, −4.5, −3.5, and −1.5 hPa in JJA, SON, DJF and MAM, respectively) and significant anomalous high over the northern Weddell Sea (maximum anomaly 1.5-2.0 hPa in SON, DJF and MAM, respectively) (Fig. 3e–h).

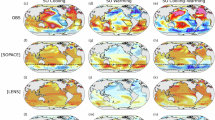

Model ensemble-mean responses of seasonal fields of a–d sea ice concentration (SIC), e–h sea level pressure (SLP) and 850 hPa wind (UV850), and i–l Surface air temperature (SAT) to the Pacific SST trend anomalies in the PACTrend experiment. The contour interval is 0.5 hPa for SLP, with red solid (blue dashed) contours denoting positive (negative) values, and zero contours are omitted. Dotted and shading areas indicate response values significant at the 95% confidence level.

Overall, above atmospheric responses to Pacific sub-decadal SST variations are similar to those to the La Niña SST anomalies36,37,38,39,40 and negative IPO SST anomalies10,11, and the associated tropical–polar teleconnections are consistent with the understanding of tropical teleconnections to the SH extratropics arising from the tropical Pacific variability associated with ENSO and IPO reviewed in Li et al.17. In Fig. 3, sea ice increase and cold SAT over the ABS and Ross Sea are simulated in all four seasons mainly due to the southerly wind anomalies associated with the deepening of the ASL, which assists in bringing more cold air from Antarctica, driving sea ice northward and enhancing sea ice expension1,8,11,33. In cold seasons, JJA and SON, the simulations generally reproduce observed sea ice decline and warm SAT trends over the Weddell and Indian Ocean Seas and West South Pacific when tropical–polar teleconnections are strongest (Fig. 3a, b, i, j). Although the PACTrend experiment captures spatial patterns of observed SLP trends in DJF and MAM, the sea ice decline from the Bellingshausen-Weddell Seas and Western South Pacific are much weaker than the corresponding observed trends, indicating important contributions to SIC decline by other forcings in these two warm seasons. In Fig. 3g, h, strengthened westerlies likely drive cooling and sea ice increase over the southern Weddell Sea in DJF and MAM by advecting cold and surface mixed-layer waters northward by the Ekman effect8,25, and reduce sea ice loss over the northern Weddell Sea and Indian Ocean.

Second, the global SST trends are added to the model-simulated SST in the global ocean between 60°S and 60°N in the GLTrend experiment. As shown in Figs. 2a and S2, significant and persistent SST warming is found over the tropical Atlantic and the high-latitude North and South Atlantic, and weak cooling occurs over the Indian Ocean in each season. The contributions of the global SST trend to the SIC and atmospheric changes are shown in Figs. 4 and S4–S5. Key circulation responses (e.g., the deepening of the ASL and positive SLP anomalies in the Western South Pacific and PSA Rossby wave patterns in all seasons, and DJF positive SAM) to global SST trends remarkably resemble those to Pacific SST trends. Compared to those responses in Fig. 3, the strengthened ASL responses are slightly enhanced in JJA, DJF and MAM with the maximum anomalies of −4.0, −4.0, and −2.5 hPa, respectively, and the anticyclonic responses over the Weddell and Ross Seas are reduced in JJA, SON and MAM (Fig. 4). The model atmospheric responses of SLP and Z300 to the global SST trend (Figs. 4e–h, S5e–h) reproduce the major features of the observed circulation changes in all seasons, except similar eastward shifts of the strengthening JJA ASL and PSA teleconnection as in the PACTrend experiment. The pattern correlations between observed SLP trend and forced SLP response between 50°S and 90°S are −0.08, 0.39, 0.92, and 0.69 in JJA, SON, DJF, and MAM, respectively. Two sets of pacemakers run thus better reproduce the observed SLP trends in the other three seasons but simulate a deepening of the ASL with a 45° longitude phase shift from observations in Austral winter. This indicates that Southern Ocean atmospheric circulation changes are mainly induced by Pacific sub-decadal SST variations in the other three seasons in the recent decade but also by other factors in winter, such as atmospheric internal variability.

Same as Fig. 3 except for model ensemble-mean responses of seasonal fields of a–d sea ice concentration (SIC), e–h sea level pressure (SLP) and 850 hPa wind (UV850), and i–l Surface air temperature (SAT) to the global SST trend anomalies in the GLTrend experiment.

The relative contributions of Atlantic and Indian Ocean SST trends are shown in Figs. S7–S9 by subtracting responses in the PACTrend simulation from those in the GLTrend simulation. Tropical Atlantic SST warming and Indian Ocean cooling can perturb the zonal Walker circulation and change the local Hadley cell15,16,17, creating anomalous convergent (divergent) flow across the upper troposphere in the central-eastern Pacific and eastern Indian Ocean (tropical Atlantic and western Indian Ocean) (Fig. S7a–d), and leading to significant positive precipitation responses over tropical Atlantic-South America with a strengthened and southward shifted SACZ and increased (reduced) precipitation over tropical Africa and the western tropical Indian Ocean (the eastern tropical Indian Ocean) in all four seasons (Fig. S8a–d). As demonstrated in previous studies15,16,17, the interaction between the anomalous convergence (divergence) over the subtropic Atlantic (eastern Indian Ocean) and mean vorticity produces positive (negative) RWS in the South Atlantic through to the western South Indian Ocean and also over the western South Pacific (eastern South Indian Ocean and South Pacific) (Fig. S7e–h). These RWS subsequently excite two wave trains that teleconnect the region of the tropical Atlantic and Indian Ocean, forcing to the extratropic, one from the tropical Atlantic to the Amundsen-Bellingshausen-Weddell seas and another wave train from the subtropical South Indian Ocean and Australia toward the western South Pacific and South Atlantic (Fig. S8e–h). These two wave trains appear to constructively increase the strength of both the trough and the ridge that develops over the Southern Ocean significantly in the JJA, SON, and DJF seasons.

Overall, SLP and UV850 responses to Atlantic and Indian Ocean SST trends are much weaker than those to Pacific SST forcing (Figs. S9e–h, 3e–h) but cause significant warm SAT and sea ice reduction over most areas of the ABS and Weddell Sea, and Western South Pacific. In DJF, Atlantic and Indian Ocean SST trends induce a strong positive (negative) Z300 response over the Weddell Sea (ABS) (Fig. S8g), and a weak but significant SLP and anticyclonic wind response over the Weddell Sea and warm northerly flow, leading to local SAT warming and significant sea ice loss over the Weddell Sea and ABS (Fig. S9c, g, k). This explains why a large SIC decline over the Weddell Sea and less SIC increase over the ABS is simulated in the GLTrend experiment (Fig. 4c, k). Similar warm air advected from the north and northerly onshore flow effect on sea ice loss associated with responses of 850 hPa winds are also simulated in other seasons, significantly enhancing (reducing) the effects of SAT warming (cooling) and sea ice decline (gain) by the Pacific SST forcing over the Weddell Sea and Western South Pacific (the ABS). The GLTrend experiment thus simulates much stronger signals of warming SAT and sea ice decline over the Southern Ocean than the PACTrend experiment (Figs. 3 and 4). The spatial and seasonal patterns of Antarctic sea ice concentration decline, particularly the significant ice loss in the Bellingshausen-Weddell Sea and Western South Pacific, are better captured in the GLTrend experiment. Seasonal Antarctic SIE decreases −0.70 (−0.39), −0.68 (−0.47), −1.21 (−0.25) and −0.53 (0.09) * 106 km2 from JJA to MAM in the GLTrend (PACTrend) experiment, respectively (Table S1). The Pacific and global SST-induced annual Antarctic SIE decreases are −0.40 and −0.72 * 106 km2, accounting for about 22% and 40% of the observed SIE trend (−1.84 * 106 km2/decade), respectively.

Third, the PACTrend experiment reproduces observed North and South Atlantic SST warming and tropical to subtropical (midlatitude) Indian Ocean cooling (warming) trends (the left panels), but simulates a cooling tropical Atlantic SST response, in contrast to observed warming trend there (Fig. 5a–d and left panels in Fig. S10). Consistent with warming SST responses over the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans, significant upper ocean warming responses over these areas are also simulated in each season (right panels in Fig. S10, Fig. 5e and S11). Amplitudes of 0–50 m annual mean temperature responses averaged over 50°–65°S in the South Atlantic and Indian Ocean sectors are about 0.37 °C and 0.18 °C, respectively. Figure 6 shows a strong (weak) annual warming trend of 0.51 °C/decade (0.13 °C/decade) from the Argo float data in the South Atlantic (South Indian Ocean). Numerous studies have demonstrated that Pacific SST variability can excite other modes of climate variability in the Atlantic and Indian Oceans by altering the general circulation of the atmosphere on interannual and decadal time scales, as reviewed by Wang et al.43 and Li et al.17. When an El Nino event is developed and matured, a basin-side warm Indian Ocean and a warm tropical North Atlantic Ocean occur in boreal winter or in the following spring43. On decadal time scales, there is a same-sign SST response in the tropical Atlantic when observed SSTs are specified in historical tropical Pacific pacemaker experiments, and processes in the Pacific and Atlantic are sequentially interactive through the atmospheric Walker circulation along with contributions from midlatitude teleconnections for the Atlantic response to the Pacific44. In fact, seasonal SST responses over the Atlantic and Indian Ocean in the PACTrend experiment in Fig. S10a–d are similar to, but stronger than those to the IPO forcing in Fig. 2c (also Fig. 1a in Meehl et al.44). The monthly mixed-layer heat budget in the Southern Ocean reveals that the SST and top layer warming over the Weddell Sea and Indian Ocean sector is driven by both oceanic heat advection and surface heat fluxes received by the ocean in the PACTrend experiment (Fig. S12). This is consistent with the previous findings that mixed-layer temperature variations averaged over the latitude band of 50°–65°S are primarily governed by heating due to air-sea fluxes and northward Ekman transport and wind-driven entrainment29,45. Therefore, the impacts of Indian Ocean and high-latitude Atlantic sub-decadal SST variations on atmospheric circulation and the consequent rapid decline in Figs. S7–S9 are likely relevant to that of the contemporary Pacific sub-decadal variations in Fig. 2a and S2. Above results suggest the dominant forcing of La Niña-like Pacific sub-decadal SST variations on the deepening of the ASL and positive SLP trends over the Weddell Sea, Western South Pacific and Indian Ocean sectors in all seasons, and the joint forcing of Pacific and tropical Atlantic sub-decadal SST variations on Southern Ocean surface warming and SIE decline in the recent decade.

Same as Fig. 3 except for a–d seasonal mean SST south of 50°S and e subsurface temperature averaged over 50–65°S in the whole Southern Ocean (0–360°E) and five sectors of the Ross Sea, Amundsen and Bellingshausen Seas, Weddell Sea, South Indian Ocean, and Western Pacific Ocean. Solid (dash) lines in (d) indicate trend values significant (insignificant) at the 95% confidence level. Green boxes in (a–d) demarcate the area of prescribed observed SST trends over 50–60°S of the Pacific sector in the PACTrend experiment.

Seasonal mean time series of subsurface temperature in the Argo float data from January 2004 to August 2024, in degrees Celsius averaged over 50–65°S in a the whole Southern Ocean and b–f five sectors of the Ross Sea, Amundsen and Bellingshausen Seas, Weddell Sea, South Indian Ocean and Western Pacific Ocean, and g linear trends of these anomalies from June 2013 to May 2023. Ocean temperature anomalies are calculated relative to the 2004–2023 climatology. Solid (dash) lines in (g) indicate trend values significant (insignificant) at the 90% confidence level.

Meanwhile, the temperature profiles of the upper 1000 m of the ocean in Figs. 5e and S11 and spatial patterns in Fig. S10e–h reveal that Pacific sub-decadal SST variations have induced 100–500 m subsurface warming in the Weddell Sea and Indian Ocean and the whole Southern Ocean throughout the year. Surface warming can penetrate into the subsurface through lateral advection, absorption of solar energy to warm the ocean mixed layer, and Ekman pumping12,29. Although a cold top-layer temperature is nudged over the ABS and Ross Sea in the PACTrend experiment, 100–500 m subsurface warming is also simulated there, which is contributed by the oceanic poleward heat advection and Ekman pumping effect bringing warmer water upward as discussed in the next section. In the GLTrend experiments, significant subsurface warming is also simulated in the Weddell Sea and Indian Ocean, as well as the whole Southern Ocean (Fig. S13).

Compounding Pacific and subsurface forcing of SIE decline

A strengthened ASL induces strong southwesterly flow across the Amundsen-Ross Seas and is supposed to increase SIE as simulated in both experiments (Figs. 3 and 4), which is in contrast to a decrease in SON and weak sea ice increase there in other seasons in observations (Fig. 1). As noted earlier, Fig. 1 also shows concurrent cold or weak warm SAT and large SIC decline over the eastern Weddell Sea in DJF and wide areas from the Weddell Sea to Ross Sea in JJA. The Southern Ocean subsurface warming (Fig. 6a) is suggested to link to the current low sea ice state afterward25,26,28. Five Antarctic sectors show similar subsurface ocean features (Fig. 6b–f), but with the largest magnitude and increased trend over the Weddell Sea (Figs. 6d and S14). The expected sea ice gain over the Amundsen and eastern Ross Seas due to the strengthened ASL resulting from the La Niña Pacific sub-decadal SST trends (Fig. 3a–h) is offset by the subsurface ocean warming effect, explaining why a weak sea ice trend is observed there. In contrast, the atmospheric changes and consequent decreasing SIE over the Weddell–Bellingshausen Seas and Indian Ocean and Western Pacific Ocean by Pacific and tropical Atlantic SST forcing are enhanced by the Southern Ocean subsurface warming effect. Significant and largest warming trends of 0–50 m mean temperature (about 0.76 °C/decade) are found over Weddell Sea in DJF and MAM (Fig. S14c, d), which is consistent with the maximum sea ice decline there in these two seasons (Fig. 1d, e). Even when the observed SST trends are prescribed in the top mixed layer, the seasonal and annual mean responses of 0–50 m mean temperature over the whole Southern Ocean and five sectors to global sub-decadal SST trends are less than the corresponding warming trends (Fig. S13). A weak SIC decline in the GLTrend experiment could be partially due to smaller upper ocean warming forcing compared to observations.

Meehl et al.12 suggest that the negative trend in wind stress curl (WSC) during 2000-2014 associated with negative IPO/positive SAM produces upward advection of warmer subsurface water through Ekman pumping. During 2014–2023 Austral summer, the negative trends in WSC over the southeast Weddell Sea, Western Pacific Ocean and Ross Sea (Fig. 7c), associated with anomalous westerlies for the Pacific-forced positive SAM in Fig. 1h, would also result in more upwelling of warm subsurface water around Antarctica and contribute to sea ice decline in these areas. This explains why a large sea ice decline but weak SAT warming occurred in those areas to some extent (Fig. 1d, l). Similar but weaker negative WSC responses over the Weddell Sea in the Austral summer are also simulated in PACTrend and GLTrend experiments (Fig. 7g, k). In all four seasons, significant negative trends in WSC are observed over most areas in the ABS and Ross Sea (Fig. 7a–d), and the association upwelling Ekman pumping effect greatly reduces surface cooling and sea ice gain over the Amundsen and Ross Seas induced by the strengthened ASL as analyzed in last two sections. Therefore, weak sea ice and SAT trends are observed over the Amundsen and eastern Ross Seas from SON to MAM (Fig. 1c–e, k–m). Spatial and seasonal patterns of negative WSC trends over the ABS and Ross Sea are well reproduced but underestimated in two pacemaker experiments (Fig. 7e–l). Although still contributing to 100–500 m subsurface warming over the ABS and the Ross Sea in simulations, upwelling Ekman pumping effects would weakly offset the large sea ice gain and cooling SAT due to the enhanced ASL, explaining why significant cold SAT and large sea ice are simulated over these areas in Figs. 3 and 4. In JJA, a negative trend in WSC is observed over the northeastern Weddell Sea (Fig. 7a) and likely contributed to 100–500 m subsurface warming and sea ice decline there (Figs. S14a and 1b), but such upwelling Ekman pumping is not simulated in two experiments. The underestimated atmospheric and ocean signals in two pacemaker experiments jointly provide an interpretation as to why the forced SIE declines are weaker than the observed SIE trend.

a–d Linear seasonal mean trend from 2013/06 to 2023/05 of WSC (Nm−3 × 10−8 decade−1), computed from ERA5 turbulent wind stress; e–l seasonal mean responses of WSC (Nm−3 × 10−8) to the Pacific and global sea surface temperature (SST) variations in the PACTrend and GLTrend experiments. Negative WSC values denote areas of Ekman suction that would move water upward in the column. Dotted areas denote observed trend (model response) values significant at the 90% (95%) confidence level.

The radiative forcing is fixed at the preindustrial level in both PACTrend and GLTrend experiments. Contributions of radiative forcing resulting from anthropogenic-induced factors (e.g., rising well mixed greenhouse gas and changes of stratospheric and tropospheric ozone, aerosol and biomass Burning Emissions, and land uses) and natural factors (solar and volcanic forcing) to Antarctic SIE and associated circulation changes are assessed by examining the output from the seventeen models covering the observed period of June 2013 to May 2023 under the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) historical and the SSP3-7.0 future radiative forcing scenarios. Figure S15 indicates that there is a circumpolar decrease in SIC and warming SAT over the large areas of the Southern Ocean in all four seasons, with larger forced signals in MAM and JJA. The SLP and UV850 trends are much weaker than those in the PACTrend experiment, with positive SAM-like patterns in MAM and JJA and a maximum trend of −0.75 (−0.50) hPa/decade over Weddell Sea in JJA (Antarctica in MAM). The seasonal SIE trends range from −0.16 to −0.26 * 106 km2/decade, and the annual mean trend is −0.22 * 106 km2/decade, about 12% of the observed annual SIE trend (Table S1).

Discussion

Our coupled pacemaker experiments well reproduce spatial and seasonal patterns of observed SLP trends (including the all-seasonal strengthening of the ASL and positive SLP trends over the Weddell Sea and the Western South Pacific, and DJF positive SAM), PSA teleconnections, Southern Ocean surface and subsurface warming, negative WSC trends and Antarctic SIC decline with high fidelity. We conclude that La Niña-like Pacific sub-decadal SST variations were the primary driver of changes in Southern Ocean atmospheric circulation and South Atlantic and Indian Ocean SST warming through tropical–polar teleconnections and significantly contributed to Southern Ocean subsurface warming and the decline of Antarctic sea ice in the recent decade. Pacific sub-decadal SST variations originated from the ENSO evolution (from the 2014–2016 El Niño to the 2020–2023 La Niña conditions) and the IPO phase shift (from the positive phase in 2014–2016 to the negative phase after 2016). The SIC and atmospheric responses to the IPO-only forcing with phase shift from positive to negative (Fig. S16) are much weaker than those to the total Pacific 10-year SST trends in the PACTrend experiment (Fig. 3). Considering that the ensemble averaging process generally reduces the magnitudes of atmospheric circulation responses to prescribed SST forcing in the coupled pacemaker experiments, at least 40% of observed annual Antarctic SIE decline is attributed to Pacific and relevant Atlantic and Indian Ocean sub-decadal SST variations, and also tropical Atlantic SST warming. Such impacts have amplified the diminishing effect of Southern Ocean subsurface warming on Antarctic SIE decline, together explaining why Antarctic SIE has dramatically declined in the recent decade. Decadal hindcasts initialized in 2014 and 2015 indicate that approximately half of the SIE difference between low ice states in 2017–2020 and high ice states in 2012–2015 can be attributable to subsurface warming28. Both Pacific and tropical Atlantic sub-decadal SST variations have acted in concert with the Southern Ocean subsurface ocean to produce the tremendous Antarctic SIE decline from June 2013 to May 2023, while the warming effect of anthropogenic radiative forcing might have played a minor role that accounts for about 12% of the overall reduction in SIE.

Since June 2023, a strong El Niño condition has developed27, and cold La Niña-like cold conditions in the central-eastern tropical Pacific in the 10-year SST trends in winter and spring during 2014–2023 are weaker than those during 2013–2022 in Fig. S2a, b, likely mitigating sub-decadal impacts of Pacific SST trends on the Antarctic SIE in these two seasons. In 2023, Austral summer and autumn SLP anomalies from the ABS and Weddell Sea resemble observed trends in Fig. 1h, i, and the shift in the ASL toward 90°W and large heat transports contributed to the loss of sea ice in the Weddell Sea. Meanwhile, anomalous PSA associated with the emerging El Niño and an anomalous zonal-wavenumber-three (ZW3) atmospheric circulation drove this exceptional low in winter27,46, and the combining impacts of anomalously warm upper‐ocean temperatures and anomalously strong northerly winds on impeding the ice advance during the fall and winter25,47,48,49,50, significantly contributing to the second half 2023 Antarctic SIE decline. Considering that changes in tropical deep convection fundamentally control the ZW3 pattern51 and that anomalously abundant rainfall in the equatorial Pacific was observed in 2023 winter27, the strong stationary ZW3 pattern in the 2023 JJA was very likely driven by the developing El Niño. On the other hand, observed Southern Ocean subsurface warming persists in the second half of 2023 (also through 2024, Fig. 6) and has very likely also contributed to Antarctic SIE loss since June 202349,50.

The 2023 record-low Antarctic sea ice coverage and the emergence of significant sea ice decline in the recent decade indicate a new low-extent state, a regime shift in Antarctic sea ice, and a potential transition in the Southern Ocean–ice–atmosphere system25,26,52,53. Several studies have hinted that recent record-low sea ice years may be less unusual in the near future25,26,54. The increased autocorrelation and predictability of Antarctic sea ice season by season during the last 15 years found by Hobbs et al. (ref. 52) are likely related to a slow and lagged response to SST and subsurface temperature anomalies. Espinosa et al.50 demonstrate that the 2023 winter sea ice anomalies were largely driven by warm Southern Ocean conditions that developed prior to 2023 and were predictable six months in advance. Their ensemble forecast correctly predicted that near-record-low sea ice would persist in the Austral winter of 2024 due to persistent warm Southern Ocean conditions. The subsurface ocean warming began prior to 2016 and has persisted since, and is contributing to the current low sea ice state26,28. In the long term, the subsurface Southern Ocean warming in the upper 2000 m since the 1950s is largely attributed to anthropogenic forcing55. Decadal-time scale trends of strengthened circum-Antarctic westerlies associated with the negative phase of the IPO and positive phase of the SAM moved warm subsurface water upward in the water column due to Ekman pumping during 2000–2016 and, in turn, decreased the Antarctic SIE45. Subsurface heat reduces the ocean stratification, and the associated deep convection brings subsurface warm water to the surface and decreases the SIE in the surface ocean2,28. The albedo feedback further amplifies such warming in the Southern Ocean35. Our results demonstrate that Pacific sub-decadal SST trends have also significantly contributed to Southern Ocean subsurface warming in the recent decade through changes in subsurface ocean heat flux and advection and the Ekman pumping effect. Subsurface warming has strongly enhanced since 2020 over most of the Southern Ocean (Fig. 6) and will push the Antarctic into a lower-ice state in the coming decade.

Methods

Observational datasets and analysis

The six observational datasets used here are as follows: (1) The monthly SIC data are the newly updated homogeneous monthly high-resolution data derived from passive microwave satellite data with the bootstrap algorithm35. (2) The monthly SLP, 850 hPa u- and v-components of wind (UV850), and 300 hPa geopotential height (Z300) and SAT are from the ERA5 reanalysis56. (3) SST dataset is the Extended Reconstructed Sea Surface Temperature (ERSSTv5) dataset derived from the International Comprehensive Ocean-Atmosphere Dataset (ICOADS)57. (4) Ocean subsurface temperature data from January 2004 to December 2023 are derived from the extension of the gridded Argo data product58. (5) The IPO and Nino34 SST indices are from the Earth System Research Laboratory (ESRL) of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and calculated from the ERSSTv5 dataset. The IPO index is the Tripole Index (TPI)59, based on the difference between the SST anomaly averaged over the central equatorial Pacific (10°S–10°N, 170°E–90°W) and the average of the SST anomalies in the Northwest (25°N–45°N, 140°E–145°W) and Southwest Pacific (50°S–15°S, 150°E–160°W): SSTA2 − (SSTA1 + SSTA3)/2, which is a measure of interdecadal variability in the Pacific. (6) Precipitation data is from CMAP Precipitation60.

Antarctic sea ice has dropped rapidly since a record high in 2014. Linear trends are calculated for seasonal mean of Antarctic SIC anomalies in three successive months of June–July–August (JJA), to September–October–November (SON), December–January–February (JFM), March–April–May (MAM) in the period of June 2013 to May 2023. The time period June 2013 to May 2023 was chosen to calculate a 10-year linear trend for each season, avoiding the influence of the ongoing El Niño event starting from June 2023. When a strong El Niño condition developed during the spring of 2023, 10-year linear SST trends in the central-eastern Pacific in Austral winter or spring during 2014–2023 significantly weakened. The mechanisms of the continuing Antarctic SIE decline in the 2023 Austral winter and spring are mainly due to atmospheric forcing and subsurface warming, as discussed in the main text. Similarly, linear trends of seasonal mean ERA5 SAT, UV850, SLP, and Z300 anomalies are calculated in the above period. We examine SIE for the Southern Ocean as a whole and for five sectors that have been considered in a number of earlier studies (e.g., Turner et al.23). These are the Ross Sea (160°E–130°W), Amundsen-Bellingshausen Sea (ABS) (130°W–60°W), Weddell Sea (60°W–20°E), Indian Ocean (20°E–90°E), and western Pacific Ocean (90°E–160°E).

We analyze the responses of Rossby wave source and Rossby wave flux (WAF) on 300 hPa. The upper-level component of this vorticity source, denoted the Rossby wave source (RWS)42, is defined as:

Where ζ is the absolute vorticity and D is the horizontal wind divergence, \({V}_{\chi }\) is the divergent component of the horizontal wind vector and ∇ represents the horizontal gradient operator. WAF is used to study the propagation of Rossby waves to study the propagation mechanism of the atmospheric circulation to the SST forcing. We use the formula proposed by Takaya and Nakamura61 to obtain the horizontal component of WAF. The horizontal component of the WAF in the form of 300 hPa geostrophic wind can be written as:

Where \(\bar{U}=\left(\vec{u},\vec{v}\right)\) is the horizontal climatological geostrophic wind field, \({\psi }^{{\prime} }\) is a stream function anomaly derived from the 300 hPa geopotential height by the quasi-geostrophic approximation method, and x and y represent the longitude and latitude directions respectively. The upper horizontal line represents the time average.

Following Meeth et al.12, we estimate the magnitude of Ekman pumping by calculating the vertical component of the curl of the wind stress (WSC):

Where constant ρ0 is the density of seawater (1025 kg m−3), f is the Coriolis parameter, and τx and τy are eastward and northward surface stress, respectively. Negative trend or response values of WSC denote areas of Ekman suction that would move water upward in the column and cause sea ice decline.

Coupled Pacific and global Pacemaker experiments

We perform a 100-year fully coupled control simulation (CTR) with the preindustrial radiative forcings and two sets of coupled pacemaker simulations using Community Earth System Model 1.2 (CESM1.2)62 to examine the effects of Pacific and global sub-decadal SST trends from June 2013 to May 2023. CESM1.2 ensemble pacemaker experiments with a partial assimilation approach in the Pacific and global oceans are similar to the idealized pacemaker experiment in Meehl et al.44. In these experiments, the SST anomaly that amounts to observed ERSSTv5 SST trends from June 2013 to May 2023 at each grid box is added to the model-simulated SST climatology over the Pacific or global region from 60°S to 60°N, named the PACTrend and GLTrend experiments, respectively, with preindustrial radiative forcings. In other words, the model SST is only restored to the observed trend anomalies superimposed on the model’s own climatology over the specified region of the Pacific or global oceans, and the model evolves freely outside of the restoring region, allowing a full response of the climate system. The SST restoration is performed using a restoring time scale of 2 days. Data in sea ice regions are not assimilated, so temperature anomalies in the sea ice region are not constrained by observations and sea ice variations are completely controlled by the internal dynamics. Each set of pacemaker simulations begins from the control run and runs for 100 years, and the prescribed SST forcing repeats annually. Each year is considered to be an ensemble member. The climate response of any variable is the difference between the seasonal means from the last 80 years of each coupled pacemaker run and the 80 years of the coupled control run, allowing a 20-year spin-up of the Parallel Ocean Program (POP) ocean model. The statistical significance of grid-box responses is assessed by a standard two-tailed difference of means Student’s t-test.

To examine responses of top-layer ocean temperature to Pacific SST trends, we utilize monthly output to calculate the mixed-layer heat budget over the Southern Ocean. The equation for the mixed-layer heat budget can be expressed as follows29,46:

Here, T represents the mixed-layer temperature and H is the mixed-layer depth; \(\vec{{{\rm{V}}}}\) signifies horizontal and vertical velocity and ∇ represents the gradient operator; Qnet denotes the surface net heat flux into the ocean as the sum of shortwave radiation, longwave radiation, latent heat flux, and sensible heat flux. Constant \({C}_{p}\) (3996 J kg−1 K−1) represents specific heat capacity. Residual includes mainly vertical entrainment and mixing.

This study also analyzes outputs from ideal pacemaker simulation experiments conducted with the CESM1.245 to examine Antarctic SIC response to the shift of IPO from a short-lived positive phase during 2015-1630,45 to the negative phase. There are two sets of ten ensemble idealized Pacific pacemaker simulations in which one standard deviation of SST anomalies is added to the model-simulated SST in the Pacific between 40°S to 60°N: positive Pacific Decadal Variability (PDV) and negative PDV in Fig. 2c. The IPO and the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO) are highly correlated both spatially and temporally, and they are referred to collectively as the PDV mode. Each ensemble selected 10 starting years with varying PDV states from the CESM1 large-ensemble preindustrial control run: negative PDV (years 926, 1331, 1366); positive PDV (years 606, 1011, 1251); neutral PDV but trending toward negative (years 1321, 1356). Each ensemble commences on January 1 and continues for a duration of 10 years, during which the specified seasonal cycle of SST anomalies in the respective areas was kept constant in time while the rest of the model was fully coupled45. Annual responses of SST in Fig. 2c and seasonal responses of SIC, SLP, and UV850 to PDV−SST forcing in Fig. S16 are the ensemble-mean difference between the PDV- simulation and PDV+ simulation. Global responses of SST and SLP to the PDV forcing were examined by Meehl et al.44.

CMIP6 simulation analysis

To estimate the forced SIC and atmospheric responses to radiative forcing, we use the multimodel ensemble mean from phase 6 of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP6)63. To match observations, CMIP6 data from the historical and SSP3-7.0 experiments are concatenated from June 2013 to May 2023. We include 17 CMIP6 models that have at least three ensembles for both historical and SSP3-7.0 simulations to reduce the impacts of large internal variability on the 10-year SIC trends (Table S2). Similar amplitudes of Antarctic SIE trends in Table S1 and SIC trends in Figure S15 are obtained if SSP5-8.5 experiments are used. For significance testing, we compute the standard deviation (σ) of 10-year trends in any region or grid box using the 304 superensemble members from these 17 models, with all members assumed to be independent. We apply a two-sided local significance test (|trend| ≥ 2.0σ/\(\sqrt{{Ne}}\)) to determine whether the superensemble mean simulated trend is significantly different from zero at the 5% significance level, where Ne = 304. The estimated seasonal and annual mean 10-year SIE trends range from −0.16 to −0.26 * 106 km2/decade (Table S1). When estimated as the average of ensemble-mean trends of 17 models, similar 10-year SIE trends are found (Table S1).

Data availability

All observational, CMIP6, and idealized pacemaker model datasets used in this study are publicly available online. The Antarctic sea ice data are from the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) (https:// https://nsidc.org). ERA5 data is available from the ECMWF website at https://www.ecmwf.int/. The ERSSTv5 SST, the IPO and Nino34 index, and CMAP precipitation datasets may be downloaded from the Earth System Research Laboratory (ESRL) of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) website at https://psl.noaa.gov. Argo ocean temperature data is from https://sio-argo.ucsd.edu/RG_Climatology.html. The CESM1.2 idealized pacemaker simulation data are available from https://www.cesm.ucar.edu/working-groups/climate/simulations/cesm1-pacific-pacemaker. The CESM1.2 Pacific and global pacemaker simulation data are available from https://codeocean.com/capsule/0103116/tree (https://doi.org/10.24433/CO.0103116.v1). Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The current CESM1.2 version is freely available at www.cesm.ucar.edu/models/cesm1/. The NCL scripts used to generate the plots in this paper are available from https://codeocean.com/capsule/0103116/tree (https://doi.org/10.24433/CO.0103116.v1).

References

Turner, J. et al. Recent changes in Antarctic sea ice. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: mathematical. Phys. Eng. Sci. 373, 20140163 (2015).

Gagné, M.-È., Gillett, N. P. & Fyfe, J. C. Observed and simulated changes in Antarctic sea ice extent over the past 50 years. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 90–95 (2015).

Polvani, L. M. & Smith, K. L. Can natural variability explain observed Antarctic sea ice trends? New modeling evidence from CMIP5. Geophys. Res. Lett. 40, 3195–3199 (2013).

Singh, H., Polvani, L. & Rasch, P. Antarctic sea ice expansion, driven by internal variability, in the presence of increasing atmospheric CO2. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 2019GL083758 (2019).

Zhang, L., Delworth, T. L., Cooke, W. & Yang, X. Natural variability of Southern Ocean convection as a driver of observed climate trends. Nat. Clim. Change 9, 59–65 (2019).

Holland, P. R. & Kwok, R. Wind-driven trends in Antarctic sea-ice drift. Nat. Geosci. 5, 872–875 (2012).

Clem, K. R. & Fogt, R. L. South Pacific circulation changes and their connection to the tropics and regional Antarctic warming in Austral spring, 1979–2012. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 120, 2773–2792 (2015).

Hobbs, W. R. et al. A review of recent changes in Southern Ocean sea ice, their drivers and forcings. Glob. Planet. Chang. 143, 228–250 (2016).

Ding, Q. & Steig, E. J. Temperature change on the Antarctic Peninsula linked to the tropical Pacific. J. Clim. 26, 7570–7585 (2013).

Purich, A. et al. Tropical Pacific SST drivers of recent Antarctic sea ice trends. J. Clim. 29, 8931–8948 (2016).

Meehl, G. A. et al. Antarctic sea-ice expansion between 2000 and 2014 driven by tropical Pacific decadal climate variability. Nat. Geosci. 9, 590–-595 (2016).

Meehl, G. A. et al. Sustained ocean changes contributed to sudden Antarctic sea ice retreat in late 2016. Nat. Commun. 10, 14 (2019).

Lee, S.-K. et al. Wind-driven ocean dynamics impact on the contrasting seaice trends around West Antarctica. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 122, 4413–4430 (2017).

Chung, E. S. et al. Antarctic sea-ice expansion and Southern Ocean cooling linked to tropical variability. Nat. Clim. Chang. 12, 461–468 (2022).

Simpkins, G. R. et al. Tropical connections to climatic change in the extratropical Southern Hemisphere: the role of Atlantic SST trends. J. Clim. 27, 4923–4936 (2014).

Li, X. et al. Impacts of the north and tropical Atlantic Ocean on the Antarctic Peninsula and sea ice. Nature 505, 538–542 (2014).

Li, X. et al. Tropical teleconnection impacts on Antarctic climate changes. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2, 680–698 (2021).

Purich, A., Cai, C., Sullivan, A. & Durack, P. J. Impacts of broad-scale surface freshening of the Southern Ocean in a coupled climate model. J. Clim. 31, 2613–2632 (2018).

Swart, N. C. & Fyfe, J. C. The influence of recent Antarctic ice sheet retreat on simulated sea ice area trends. Geophys. Res. Lett. 40, 4328–4332 (2013).

Bintanja, R., Van Oldenborgh, G. J., Drijfhout, S. S., Wouters, B. & Katsman, C. A. Important role for ocean warming and increased iceshelf melt in Antarctic sea-ice expansion. Nat. Geosci. 6, 376–379 (2013).

Bronselaer, B. et al. Change in future climate due to Antarctic meltwater. Nature 564, 53–58 (2018).

Blanchard-Wrigglesworth, E., Roach, L. A., Donohoe, A. & Ding, Q. Impact of winds and Southern Ocean SSTs on Antarctic sea ice trends and variability. J. Clim. 34, 949–965 (2021).

Turner, J. et al. Unprecedented springtime retreat of Antarctic sea ice in 2016. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 6868–6875 (2017).

Parkinson, C. L. A 40-y record reveals gradual Antarctic sea ice increases followed by decreases at rates far exceeding the rates seen in the Arctic. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 14414–14423 (2019).

Eayrs, C. et al. Rapid decline in Antarctic sea ice in recent years hints at future change. Nat. Geosci. 14, 460–464 (2021).

Purich, A. & Doddridge, E. D. Record low Antarctic sea ice coverage indicates a new sea ice state. Commun. Earth Environ. 4, 314 (2023).

Clem, K. R. & Raphael, M. N. Antarctica and the Southern Ocean [in “State of the Climate in 2023“]. Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc. 105, S331–S370 (2024).

Zhang, L. et al. The relative role of the subsurface Southern Ocean in driving negative Antarctic sea ice extent anomalies in 2016–2021. Commun. Earth Environ. 3, 302 (2022).

Wilson, E. A. et al. Mechanisms for abrupt summertime circumpolar surface warming in the Southern Ocean. J. Clim. 36, 7025–7039 (2023).

Hu, S. & Fedorov, A. V. The extreme El Niño of 2015–2016 and the end of global warming hiatus. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 3816–3824 (2017).

Hobbs, W. R. & Raphael, M. N. The Pacific zonal asymmetry and its influence on Southern Hemisphere sea ice variability. Antarct. Sci. 22, 559–571 (2010).

Hosking, J. S., Orr, A., Marshall, G. J., Turner, J. & Phillips, T. The influence of the Amundsen-Bellingshausen Seas low on the climate of West Antarctica and its representation in coupled climate model simulations. J. Clim. 26, 6633–6648 (2013).

Raphael, M. N. et al. The Amundsen Sea Low: variability, change, and impact on Antarctic climate. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 97, 111–121 (2016).

Schlosser, E., Haumann, F. A. & Raphael, M. N. Atmospheric influences on the anomalous 2016 Antarctic sea ice decay. Cryosphere 12, 1103–1119 (2018).

Comiso, J. C. et al. Positive trend in the Antarctic sea ice cover and associated changes in surface temperature. J. Clim. 30, 2251–2267 (2017).

Liu, J. et al. Mechanism study of the ENSO and southern high latitude climate teleconnections. Geophys. Res. Lett. 29, 1–24 (2002).

Stammerjohn, S. E. et al. Trends in Antarctic annual sea ice retreat and advance and their relation to El Niño–Southern Oscillation and Southern Annular Mode variability. J. Geophys. Res: Oceans 113, 2007JC004269 (2008).

Simpkins, G. R., Ciasto, L. M., Thompson, D. W. J. & England, M. H. Seasonal relationships between large-scale climate variability and Antarctic sea ice concentration. J. Clim. 25, 5451–5469 (2012).

Ding, Q., Steig, J., Battisti, D. S. & Wallace, J. M. Influence of the tropics on the southern annular mode. J. Clim. 25, 6330–6363 (2012).

Ding, Q., Steig, E. J., Battisti, D. S. & Küttel, M. Winter warming in West Antarctica caused by central tropical Pacific warming. Nat. Geosci. 4, 398–403 (2011).

Gill, A. E. Some simple solutions for heat-induced tropical circulations. Quart. J. R. Met. Soc. 106, 447–462 (1980).

Sardeshmukh, P. D. & Hoskins, B. J. The generation of global rotational flow by steady idealized tropical divergence. J. Atmos. Sci. 45, 1228–1251 (1988).

Wang, C. Three‑ocean interactions and climate variability: a review and perspective. Clim. Dyn. 53, 5119–5136 (2019).

Meehl, G. A. et al. Atlantic and Pacific tropics connected by mutually interactive decadal- timescale processes. Nat. Geosci. 14, 36–42 (2021).

Dong, S., Gille, S. T. & Sprintall, J. An assessment of the Southern Ocean mixed layer heat budget. J. Clim. 20, 4425–4442 (2007).

Ionita, M. Large-scale drivers of the exceptionally low winter Antarctic sea ice extent in 2023. Front. Earth Sci. 12, 1333706 (2024).

Gilbert, E. & Holmes, C. 2023’s Antarctic sea ice extent is the lowest on record. Weather 79, 46–51 (2024).

Jena, B. et al. Evolution of Antarctic sea ice ahead of the record low annual maximum extent in September 2023. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2023GL107561 (2024).

Wang, J. et al. Synergistic atmosphere-ocean-ice influences have driven the 2023 all-time Antarctic sea-ice record low. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, 415 (2024).

Espinosa, Z. I., Blanchard-Wrigglesworth, E. & Bitz, C. M. Understanding the drivers and predictability of record low Antarctic sea ice in Austral winter 2023. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, 723 (2024).

Goyal, R. et al. Zonal wave 3 pattern in the Southern Hemisphere generated by tropical convection. Nat. Geosci. 14, 732–738 (2021).

Hobbs, W. et al. Observational evidence for a regime shift in summer Antarctic Sea ice. J. Clim. 37, 2263–2275 (2024).

Landrum, L. L. & DuVivier, A. K. Sea ice is shrinking during Antarctic winter. Nature 636, 578–579 (2024).

Liu, J., Zhu, Z. & Chen, D. Lowest Antarctic sea ice record broken for the second year in a row. Ocean Land Atmos. Res. 2, 0007 (2023).

Swart, N. C., Gille, S. T., Fyfe, J. C. & Gillett, N. P. Recent Southern Ocean warming and freshening driven by greenhouse gas emissions and ozone depletion. Nat. Geosci. 11, 836–841 (2018).

Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteor. Soc. 146, 999–2049 (2020).

Huang, B. et al. Extended Reconstructed Sea Surface Temperature, Version 5 (ERSSTv5): upgrades, validations, and intercomparisons. J. Clim. 30, 8179–8205 (2017).

Roemmich, D. & Gilson, J. The 2004–2008 mean and annual cycle of temperature, salinity, and steric height in the global ocean from the Argo Program. Prog. Oceanogr. 82, 81–100 (2009).

Henley, B. J. et al. A tripole index for the interdecadal Pacific oscillation. Clim. Dyn. 45, 3077–3090 (2015).

Xie, P. & Arkin, P. A. Global precipitation: a 17-year monthly analysis based on gauge observations, satellite estimates, and numerical model outputs. Bull. Am. Meteor. Soc. 78, 2539–2558 (1997).

Takaya, K. & Nakamura, H. A formulation of a phase-independent wave-activity flux for stationary and migratory quasigeostrophic eddies on a zonally varying basic flow. J. Atmos. Sci. 58, 608–627 (2001).

Hurrell, J. W. et al. The Community Earth System Model: a framework for collaborative research. Bull. Am. Meteor. Soc. 94, 1339–1360 (2013).

Eyring, V. et al. Overview of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) experimental design and organization. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 1937–1958 (2016).

Acknowledgements

This work is funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) under Grant No 42375031, Q.W., No W2441014, L.Z. and No 91837206, Q.W. The pacemaker simulations were carried out at the National Supercomputer Center in Tianjin, and the calculations were performed on the Tianhe new generation supercomputer. The simulations are also supported by the High Performance Computing Division in the South China Sea Institute of Oceanology. L.Z. is supported by the Development fund (SCSIO202203) and Special fund (SCSIO2023QY01) of South China Sea Institute of Oceanology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences and the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2024B1515040024).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q.W. designed the research, conducted the analysis, and wrote the paper. L.Z. and H.L. run the coupled pacemaker simulations, while Q.W. and S.L. run AGCM simulations in the old manuscript. A.H. and N.R. run the idealized PDV pacemaker experiments. Y.M., L.Y., and C.Y. processed the data and drew the figures under the supervision of Q.W.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, Q., Ma, Y., Hu, A. et al. Pacific sub-decadal sea surface temperature variations contributed to recent Antarctic Sea ice decline trend. Nat Commun 16, 3386 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-58788-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-58788-1

This article is cited by

-

Recent south-central Andes water crisis driven by Antarctic amplification is unprecedented over the last eight centuries

Communications Earth & Environment (2025)

-

Preface to the Special Issue on Atmospheric and Oceanic Processes in the Antarctic and Their Climate Effects: 40 Years of CHINARE

Advances in Atmospheric Sciences (2025)