Abstract

The DNA binding of most Escherichia coli Transcription Factors (TFs) has not been comprehensively mapped, and few have models that can quantitatively predict binding affinity. We report the global mapping of in vivo DNA binding for 139 E. coli TFs using ChIP-Seq. We use these data to train BoltzNet, a novel neural network that predicts TF binding energy from DNA sequence. BoltzNet mirrors a quantitative biophysical model and provides directly interpretable predictions genome-wide at nucleotide resolution. We use BoltzNet to quantitatively design novel binding sites, which we validate with biophysical experiments on purified protein. We generate models for 124 TFs that provide insight into global features of TF binding, including clustering of sites, the role of accessory bases, the relevance of weak sites, and the background affinity of the genome. Our paper provides new paradigms for studying TF-DNA binding and for the development of biophysically motivated neural networks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Escherichia coli is the most widely used cell in biology and biotechnology, the best studied model prokaryote1,2, and the foundation for most efforts in synthetic biology. Yet despite its central importance, and a wealth of knowledge, surprising gaps remain3. Bacteria typically encode hundreds of transcription factors (TFs) whose binding to DNA modulates gene regulation. Decades of work in E. coli have led to a deep mechanistic understanding of TF function. Yet this high level of knowledge is limited to a handful of well-studied TFs. The binding affinities of most of the ~300 TFs in E. coli have not been comprehensively mapped; indeed a recent publication estimates that only 30% of E. coli TF-DNA interactions have been identified4. Moreover, many TFs lack information about even a single sequence to which they bind. And very few have experimentally validated biophysical models that can be used to quantitatively understand TF binding behavior. Such an understanding is crucial to fully deciphering cellular function and predictively engineering synthetic biology circuits.

Chromatin-immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-Seq) enables the genome-wide characterization of TF binding under in vivo conditions. However, differences in protocols, conditions, and computational processing can modulate the degree of real or apparent binding, complicating the comparison and interpretation of these results. Applied to the smaller genomes of bacteria, ChIP-Seq also has the capability to detect binding over a wide range of apparent affinities, down to very weakly bound sequences5,6,7,8. Commonly, weakly bound sites are often discarded9 despite being highly reproducible5,7. And recently, weak affinity TF binding has been demonstrated to have unique regulatory function10,11. Typically, ChIP-Seq analyses focus on cataloging a discrete set of “true” high affinity sites. A complete model of TF binding, however, must predict affinity for any sequence.

In recent years, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) for analyzing ChIP-Seq and related data have been developed with promising results12,13,14. These models leverage the feature discovery capabilities of CNNs and the flexibility and optimization capabilities of advanced neural network frameworks. Developed for eukaryotes, existing models borrow the template of image processing CNNs, with many kernels and many convolutional layers using standard neural network activation functions. These deep architectures were motivated by the recognition that multiple factors, including chromatin context and co-factors, mediate the binding of TFs in eukaryotes. However, it is not clear the degree to which these complex factors are required to understand TF binding to DNA in bacteria15. Moreover, deep CNNs come at a cost of greater complexity, which can lead to overfitting and necessitates additional algorithms for interpretation. Significantly, the scores derived from such interpretations are not directly tied to any physical parameters that can be experimentally verified.

Thermodynamic models provide a predictive description of TF function tied to biophysical quantities that can be experimentally validated16,17,18,19. TF binding is characterized by the energy released, Δε, when a protein binds a DNA sequence. Under the assumption of thermal equilibrium, Δε can be used to predict the probability of binding, and corresponding dissociation (or association) constants via the Boltzmann distribution. Multiple studies have demonstrated that this framework can be used to accurately predict the sequence specificity of TF binding and downstream gene regulation20. This framework has been applied to a range of high-throughput TF binding assays (Spec-Seq, MITOMI, PBMs, SELEX). Most recently, a machine learning method, ProBound, was developed for predicting biophysical parameters from SELEX experiments that could be applied to ChIP-Seq data21. However, ProBound was designed for eukaryotes, and is based on a custom machine learning framework, making it more difficult to adapt to other uses.

In this study, we report the global mapping of DNA binding for 139 E. coli TFs under controlled in vivo conditions using a standardized ChIP-Seq and computational analysis protocol. Our data provides the most comprehensive view of E. coli TF binding to date, and a foundation to study the determinants of TF-DNA interactions in all bacteria. We have developed a novel neural network, “BoltzNet”, that accurately predicts ChIP coverage and TF binding affinity from DNA sequence. In contrast to previous neural networks, BoltzNet is based on an explicit quantitative biophysical model of TF-DNA binding and provides directly interpretable physical predictions genome-wide at nucleotide resolution. We use BoltzNet to quantitatively design novel binding sites, which we then experimentally validate using independent in vivo, and in vitro biophysical binding assays. Our results confirm that BoltzNet directly predicts a highly accurate model of relative binding energies for existing and novel binding sites. They also provide insight into several global features of TF binding behavior, including clustering of binding sites, the importance of poorly conserved accessory bases, the physiological relevance of weak binding sites, and the background affinity of the genome. We have generated high-confidence models for 124 TFs that can be used and extended by any researcher to quantitatively interpret TF binding behavior and to predictively engineer new binding sites.

Results

Large-scale mapping of TF binding sites in E. coli

We developed a standardized protocol for mapping E. coli TFs with ChIP-Seq (Figure S3). TFs were tagged for efficient IP and expressed in two ways: from their native genomic promoters and loci, or inducibly expressed from a plasmid. We used both systems to maximize the likelihood of adequate TF expression. We applied both methods to each TF and required at least two successful experiments with either method for a TF to be considered mapped. All ChIP-Seq was performed in vivo under a single controlled condition. In addition, for selected TFs, we also performed ChIP-Seq in vitro with controlled protein concentrations. All results were analyzed using a standardized pipeline that filters out common artifacts and identifies enriched regions (Figure S5). Enriched regions are defined as contiguous sequences longer than 150 bp with coverage that is statistically enriched compared to background and that show the expected signature of forward and reverse coverage for protein binding (Figure S6). Enriched regions may contain multiple binding sites22. Coverage for enriched regions is normalized to the genome mean.

We applied our ChIP-Seq protocol to 318 predicted TFs in E. coli (Supplementary Data 1) and required that a TF have at least two replicate ChIP-Seq experiments that pass all quality control filters to be further considered. In doing so, we generated high-confidence global mapping data for 139 TFs (Fig. 1A, Figure S11). Enriched regions included the vast majority of reported high-confidence binding sites in RegulonDB for these TFs as well as thousands of additional reproducible binding regions (Supplementary Data 2). Novel regions were found for TFs that lack any reported sites, as well as for TFs that have been previously studied. Native and inducible expression were complementary. No single approach was successful for all TFs (Fig. 1B) and both were required to recover known sites (Fig. 1C), even for TFs with data from both approaches (Fig. 1D), although the inducible system outperformed native expression. Our results show enrichment is highly reproducible across replicates of the same expression mode, and highly correlated between different expression modes (Fig. 1E, F). We were not able to generate replicate ChIP-Seq data for 179 TFs (Supplementary Data 1), and we discuss this further in the Supplementary Information.

A Summary of novel regions (green) and known regions (found:blue, not found:red) for 139 mapped TFs, ordered by total number of binding regions (TFs in blue have BoltzNet models). B Mode of TF expression used to map TFs. Both experimental approaches required to map all TFs. Recovery of known sites by different expression modes for TFs mapped by (C) either or both modes of expression, or (D) both modes only. No single approach recovers all known sites, although TF induction performs better. E Example for PdhR of comparisons of ChIP-Seq experiments within and between expression modes. Axes plot log10 peak enrichment with green circles called in both replicates; orange called only in the Y-axis experiment; and blue called only in the X-axis experiment. Points with a black outline have been previously reported. F Correlation of enrichment across all replicates for all TFs. G Location of binding regions relative to start position of nearest gene (G – genic, IG – intergenic). Binding regions between 150 bp upstream and 50 bp downstream are overrepressented relative to random expectation (grey circles are means with black error bars displaying standard deviation of 100 random samples), regions > 1.5 kb up or down-stream of the nearest gene are grouped into a single bar on either edge. Data for regions with known sites shown in inset. H Both novel and known regions are observed over 3 logs of enrichment. Each row is a TF and each dot is a called region (green new region, blue known region).

Binding regions were highly enriched within 150 bp upstream and 50 bp downstream of gene starts (Fig. 1G). We also see extensive binding within genes, although intergenic binding is ~2.5-fold overrepresented (28% of enriched regions vs ~10.96% intergenic genome). Conversely, binding further from gene starts is not markedly different from expectation for all ChIP regions but is underrepresented in the set of high-confidence known sites23. We observe over three logs of enrichment across all binding regions, and within regions for individual TFs (Fig. 1H, green). Known sites are skewed to regions of higher enrichment but span the range of absolute and relative enrichment (Fig. 1H, blue). The number of binding regions varies dramaticallyacross TFs (Fig. 1A, F) and can be approximated by a power law (p(k)~k-1.9)24,25. We observe several TFs that reproducibly bind throughout the genome. Conversely, 23 TFs have only a single binding region (Supplementary Data 2) and of these 17 (74%) are regions just upstream of the TF operon that imply autoregulation. Of all 139 TFs reported, 95 (68%) have autobinding, consistent with autoregulation as a highly enriched regulatory motif26. Genome-wide, we observe that most 1 kb regions are bound by at most one TF, while certain regions can be bound by multiple TFs (Figure S15). This large diversity of binding regions provided a unique opportunity to study and model the global binding preferences of bacterial TFs.

BoltzNet architecture and training

To model sequence affinity and ChIP-Seq coverage as a function of sequence, we developed a convolutional neural network (CNN), BoltzNet, specifically designed to mirror a two-stage quantitative biophysical model of TF-binding and ChIP-seq. The first stage consists of a thermodynamic model of TF binding to a DNA site driven by the binding energy of the site relative to an unbound state, Δε16. Several studies have demonstrated that simple additive “energy matrix models” are often sufficient to describe TF-DNA binding energies15,17,18,19,27. Assuming TF binding is in thermal equilibrium, the probability that the site will be bound can be calculated via the Boltzmann distribution as:

where KD is the equilibrium disassociation constant of the binding reaction. Crucially, both KD and the probability of binding depend on the exponentiation of Δε. Given a sequence with multiple sites, the probability of a protein being bound to the sequence is related to the sum of the exp(Δε) for all sites (see Methods). In the second stage, ChIP-Seq coverage is a function of the probability that a site is bound, which we have shown can be modeled as a signal convolution22,28.

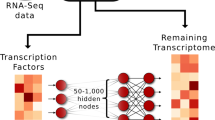

BoltzNet is designed with two components to mirror these two stages (Fig. 2A). The first component inputs 101 bp DNA sequences and models the affinity at every position in both orientations using a convolution layer consisting of a single 25 bp weight matrix (kernel) and bias term (the width of the weight matrix is a hyperparameter). The use of a single kernel encodes the hypothesis that a single linear energy matrix can predict binding energy. The output of the kernel feeds into an exponential activation function, so that the convolution layer models the affinity for each site. Subsequent pooling layers sum these values to generate an affinity score for the entire 101 bp sequence. The second component predicts coverage in multiple ChIP-Seq experiments as a function of the affinity score. We learn this mapping using the universal function approximation capabilities of a fully connected feedforward neural network29. BoltzNet is trained on a set of sequences consisting of all enriched regions for a TF (positive samples) as well as 5000 randomly selected genomic regions (negative samples) (see Methods for details).

A BoltzNet architecture. BoltzNet mirrors a thermodynamic model of TF-DNA Binding to predict ChIP-Seq coverage from sequence. A convolution component models the effective energy of TF binding to the sequence as an affinity score. The fully connected neural network component models normalized ChIP coverage in multiple experiments as a function of this score. B–J Detailed analysis of PdhR Model. B Prediction of coverage and cross-validation on training set. Predictions on a subset of representative experiments (full set in Figure S17). Black circles show leave-one-out cross-validation predictions. All coverage is normalized between zero (baseline) and 1 (most enrichment). Native #x=native promoter replicate number, inducible #x= inducible promoter replicate number, in vitro #x = in vitro ChIP-Seq replicate numbers at two different protein concentration. C Accuracy of genome-wide prediction of normalized coverage in all experiments. D A single energy weight matrix is sufficient for accurate prediction. Positive values represent more energetically favorable bases. E Predicted PFM matches known PFM from RegulonDB1. F Neural network predicts experiment specific coverage from a single sequence affinity score. Experiments with higher known or predicted protein concentrations are correctly predicted to have higher coverage for the same predicted affinity. Large symbols are predicted coverage in each experiment and small gray symbols are actual normalized coverage. In some cases, lines are not easily visible due to complete overlap. G–J Four PdhR binding sites demonstrating that BoltzNet provides direct interpretation at all scales. Four representative regions are shown. Top track is gene annotation for region. Next tracks show true coverage (red, green, blue), genome-wide coverage predictions (black) for three representative experiments, and the predicted affinity score (pink). Coverage in units of fold enrichment over mean coverage. Bottom track shows single nucleotide resolution predictions around binding site. Sequence logo shows base contribution score. Cyan shading shows known binding sites. Heatmaps shows predicted affinity at each position in positive (green) and negative (red) orientation. Sequence shown in gray. Note that different y-axis scales are used between different sites and different experiments to facilitate visualizing prediction concordance within a site.

BoltzNet accurately models sequence binding strength

Figure 2B–F provides an analysis of a BoltzNet accuracy for PdhR. PdhR is a GntR family TF with 10 validated known binding sites and a known HTH binding motif. We performed 11 ChIP-Seq experiments on PdhR including replicates of in vivo ChIP-Seq with both native and inducible promoters. Additionally, we performed in vitro ChIP-Seq at two different protein concentrations. Across all experiments we call 204 enriched regions spanning three logs of enrichment.

BoltzNet accurately predicts enrichment in all experiments (Fig. 2B) and demonstrates high specificity when applied to all 101 bp sequences in the genome (Fig. 2C). As an initial assessment of generalizability, we performed leave-one-out (LOO) cross-validation on the top 10 enriched regions. For each left-out sample both the output coverages and relative affinity scores were correctly predicted (Fig. 2B and Figures S16 & S17). And when the most enriched region was left out, it was correctly predicted in all experiments, demonstrating the potential for BoltzNet to extrapolate.

BoltzNet is interpretable and verifiable genome-wide at nucleotide resolution

The accuracy of BoltzNet is achieved from a single weight matrix that directly represents the relative contributions of each base at every position of a 25 bp binding site (Fig. 2D). The weight matrix differs from motif logos based on position frequency matrixes (PFMs), which are the most common means of representing binding sites. However, PFMs model the frequency of bases at each position in a collection of sites, and thus depend on the sites used to count frequencies in addition to the contribution of each base to binding strength (see Supplement). Moreover, PFMs are not capable of predicting ChIP-Seq coverage (Figures S26–S31), as these models are not designed to weight positive and negative contributions towards binding of each base but are designed to predict the statistical enrichment of a subsequence from a set of sequences. PFMs can be derived from weight matrixes by scanning matrixes over a set of sequences and counting the bases in each position scoring above a threshold30. Applying this approach, we confirm that BoltzNet identifies the known binding motif for PdhR (Fig. 2E).

On a genome-wide scale, the model demonstrates spatial accuracy in predicting coverage in multiple experiments simultaneously, all derived from a single affinity score for each 101 bp sequence (Fig. 2F–I). Within each sequence region, the output of the convolution provides a measure of the affinity at every position and orientation (heatmap). And at nucleotide resolution, we can measure the contribution of each base by summing the base weight in all overlapping sites multiplied by the affinity score of that site. This can be summarized in a sequence logo (Fig. 2F–I). A comparison of nucleotide level predictions with the location of know binding sites (cyan shaded regions) demonstrates that BoltzNet has accuracy to exact binding locations.

BoltzNet models expected behavior of different ChIP experiments

The neural network component must learn a mapping from a single affinity score to coverage in multiple experiments accounting for variations in IP, cell state, growth conditions, and especially protein concentration. As protein levels increase, stronger sites are bound first and saturate as weaker sites are bound. Figure 2J demonstrates that BoltzNet learns this behavior. For in vitro experiments, the model accurately predicts higher and more saturating coverage with 10x protein compared to 1x (Fig. 2J). Similarly, comparing in vivo experiments show increasing coverage and saturation with the expected greater protein concentration from inducible promoters relative to native promoters. This verification of the neural network component provides a consistency check on the model as a whole.

A compendium of TF binding models

Applied to in vivo ChIP-Seq data for 139 E. coli TFs, we have generated BoltzNet models for 124 that passed criteria for accuracy in predicting coverage and for specificity on the whole genome (Supplementary Data 3). For 36 models that overlap with known motifs in RegulonDB, we see strong concordance with the model-predicted PFM (Figure S19). Figure 3 illustrates the range of different TF behavior captured by BoltzNet models. TFs with a range of binding site profiles can be modeled. UlaR illustrates a model based on one strong site and multiple weak sites while Nac (as we have previously reported5) and GlnG have many called sites spanning the range of relative coverages. And TFs with only one called site can be modeled with the same high accuracy in identifying known sites (Figure S20). Binding sites of both low (GlnG) and high (Nac) AT-content are accurately modeled. TFs associated with σ70 (PdhR, AllR, Nac) and σ54 (GlnG) are equally well modeled. Cross-validation of models for AllR, GlnG, Nac, and UlaR (Figures S21–24), confirms model generalization and the potential for extrapolation, as with PdhR.

We have generated models for 124 TFs Supplementary Data 2, Figure S19). Here we show a summary of models for AllR - A, GlnG - B, Nac - C, and UlaR – D that span a range of different TF classes (see Text). Top row of each panel displays a scatter plot of region coverage prediction accuracy in all experiments (left. Each color represents a different experiment, the weight matrix (middle), and BoltzNet-derived PFM aligned above the known RegulonDB PFM (left). The bottom half of each panel shows nucleotide level resolution predictions as in Fig. 2G for top 3 binding sequences for each TF ordered from strongest (top) to weakest (bottom). Cyan shading shows known binding sites.

Role of clustered binding sites and accessory bases

An examination of nucleotide level predictions across models reveals two themes predicted to contribute to binding strength. First, many sequences contain multiple predicted non-overlapping binding sites (e.g. Nac, AllR, GlnG). Clustered sites (e.g. Figure 2G) can result in affinity scores equal to (e.g. Figure 2I) or stronger than any single site (e.g. Figure 3C, top sequence), suggesting that similar sequence occupancies can be achieved both ways. Moreover, BoltzNet sums the contributions of clustered sites, the accuracy of which suggests that cooperative interactions do not substantially impact occupancy31. Second, core bases are commonly conserved across a range of binding site strengths. For TFs that bind as a dimer this core is typically palindromic. Differences in binding strength appear to be determined by accessory bases outside the core, potentially by stabilizing or destabilizing contacts with the core motif. This is also apparent from weight matrices, where core bases have the strongest relative contributions, but bases outside the core can be equally important (e.g. for PdhR and GlnG the presence of cytosines between the two core palindromes has significant negative weight – Figs. 2D, 3C).

Design and validation of novel binding sites by Library-ChIP confirms role of accessory bases

To validate the predictive ability of BoltzNet as well as the role of accessory bases, we used our models to design new binding sites to be tested experimentally. This was accomplished by taking a reference binding sequence and generating all variants outside the core (Fig. 4A and Figure S25). For each TF, we selected a reference sequence containing only one strong binding site, for simplicity. BoltzNet models based on only in vivo ChIP-Seq data were used to score all variant sequences, and a set of sequences spanning a range of predicted binding affinities was selected for experimental validation.

A Novel site designs for PdhR, AllR, and GlnG. For each TF, the top singleton binding site was selected as a reference (sequence logo) and all combination of accessory bases (pink shading) were generated and used as input to the corresponding BoltzNet model. B–D Scatter plots of BoltzNet predictions vs Library-ChIP enrichment.

We first tested sequences for PdhR, AllR, and GlnG using an independent assay for in vivo binding, Library-ChIP32 (Figure S33 and Supplementary Data 6). Library-ChIP enabled high-throughput testing of a large number of sites and tested the ability of BoltzNet to generalize to a different type of binding assay. The results of Fig. 4B–D demonstrate that BoltzNet predictions were correlated with actual Library-ChIP enrichment (R2 of 0.88, 0.72, and 0.46 for PdhR, AllR, and GlnG, respectively).

BoltzNet accurately predicts binding energy

The variability observed in Fig. 4B–D, especially for GlnG, likely reflects the fact that ChIP is as much a function of the extrinsic experimental conditions spanning a population of cells as it is a function of the intrinsic binding energy of a single protein to a single DNA sequence. The affinity score of BoltzNet can be used to derive a measure of this intrinsic energy that is independent of ChIP coverage prediction. We thus sought to verify this using a biophysical assay of protein-DNA interactions, Biolayer Interferometry (BLI, Fig. 5A).

Measurement of binding kinetics for purified proteins and 61 bp DNA sequences using Bio-Layer Interferometry (BL). A BLI schematic. DNA sequences are attached to glass probes (loading-baseline). The probe is placed into a solution of TF and the kinetics of binding are measured (association). The probe is then placed into a solution without TF and the kinetics of unbinding are measured (disassociation). Based on a bimolecular model of binding, a measured effective binding energy is calculated. Created in BioRender. Lally, P. (2025) https://BioRender.com/z27l039. B–F Scatter plots of measured effective energies (relative to solution) versus predicted effective binding energies for PdhR, AllR, GlnG, Nac, and UlaR. For each TF, sequences include sites from the genome (triangles) and novel sites generated using BoltzNet. All sites were tested against all TFs. Green and orange symbols are sites selected for the given TF. Grey symbols are sites selected for other TFs. Dotted lines represent bounds of ±1.5 kBt, equivalent to average thermal energy.

We performed BLI experiments on 5 TFs with both genomic sequences and novel sequences designed as in Fig. 4A (and Figure S25 for Nac and UlaR)(Figures S54–S58). The kinetic measurements of BLI were used to estimate binding energies. Measured values were consistent with those for other DNA binding proteins33. Predicted values show a strong concordance with measured values (Fig. 5), with R2 values between 0.51 and 0.99 spanning the strongest specific binding sites (green and orange) to non-specific sequences (gray) as well as genomic (triangle) and novel designed (circle) binding sites. Sequences that contain both single (no border) and multiple (black border) binding sites were accurately predicted, supporting the energy summation model used by BoltzNet. More generally, the results confirm the ability of BoltzNet to predict relative binding energies across a range of binding site strengths and configurations, and to extrapolate to sites stronger than any found in the genome.

Large differences in enrichment reflect physiologically relevant differences in binding energy

Calibrating our model predictions with the results of Fig. 5 allows us to relate ChIP-Seq coverage to quantitative binding energies. Figure 6 reveals that large changes in relative coverage between enriched regions result from differences in binding energy spanning ~4 kbT. This is consistent with an estimated 5.8 kbT span of energies between the operators of LacI18,33,34. Weak binding sites are well within a physiological range of binding energy differences relative to strong sites. And our models predict that even small differences in sequence can differentiate weak from strong binding. Moreover, the accuracy of our models trained on weak binding regions suggests these sites contain information about the specificity of TF-DNA interactions. Many assays for DNA binding focus on cataloging the strongest binding sites. Our data support the view that weak sites are necessary for a complete picture of TF-DNA binding10,35.

A–E Results for PdhR, GlnG, UlaR, AllR, and Nac. (Left panels) Predicted relative coverage vs predicted -Δε relative to solution for 101 bp sequences. Large relative differences in coverage arise from physiologically relevant differences in binding energy. (Top and bottom right panels) Binding energy versus solution (green left axis) and genome (green right axis) and affinity (exponentiated energy) relative to strongest region (pink left axis) and genome average (pink right axis). F Probability of binding of a TF to genome versus solution as a function of energy of genome energy εgenome, (εsoln = 0) and ratio of number of sites in solution to number of sites in genome (contours). Solid line shows solution sites/genome sites = 106, points on the line display predicted probability that TFs in (A–E) are bound based on their average genome-wide energy. Results predict that most TF is bound non-specifically to genome relative to solution.

Transcription factors primarily bound non-specifically to genom

The results of Fig. 5 reveal that all 5 TFs have substantial binding energies to apparent non-specific sequences (grey symbols). Predictions of our calibrated models further suggest that all 101 bp genomic sequences have substantial binding affinity (Fig. 6A–E, green), with average genome values spanning ~15–16.5 kbT. The cellular location of TFs has long been a question of interest36,37. An analysis based on our results predicts that the majority ( > 79%) of protein molecules for our studied TFs are bound “non-specifically” to genome rather than being free in solution (Fig. 6F). This is consistent with reports on specific TFs in a number of organisms37,38,39,40, though at odds with other reports41 possibly due to differences in background genome binding energy. It also has functional implications for TF binding and gene regulation39,42,43,44.

Our results also suggest the genome average as a more natural in vivo reference point for TF binding energies compared to solution. TF binding specificity can then be seen as the distribution of binding energies relative to this reference. Highly specific TFs (e.g., GlnG, UlaR, and AllR; Fig. 6B, C, E) have lower variability in genome-wide binding energy and have one or a few sites with substantially higher affinity than this background. Less specific TFs (e.g., Nac, Fig. 6D) have much higher genome-wide binding energy variability, with few sites substantially stronger but many sites moderately stronger. TFs like PdhR demonstrate an intermediate pattern. From this perspective, TF binding affinities in vivo exist on a spectrum with the genome. BoltzNet builds quantitative models of TF binding behavior that provide this genome-wide perspective.

BoltzNet models robust to hyperparameters

To assess stability to hyperparameters, for all five TFs calibrated with BLI we built models for a range of widths of the middle layer of the neural network component (Figures S33–37) and a range of weight matrix lengths (Figures S38–42) and assessed accuracy against the independent BLI binding energy data (see Supplement). Models were largely insensitive to neural network width. Widths from 5 to 2000 nodes in the middle layer displayed virtually identical performance).

Models were also robust to range of weight matrix lengths. In all cases where a model could be built, the same relative positions and bases with significant energy contributions were identified. However, very short ( < 15 bp) or very long ( > 40 bp) matrices resulted in degraded accuracy. The highest accuracy was achieved with matrices with minimal margins around the core sequence and accessory bases. Much shorter matrices failed to capture all bases with substantial affinity contributions, lowering accuracy. And in some cases, models could not be built for matrices of length 10 or 15. Much longer matrices beyond a threshold weight matrix length (typically 40pb) also decreased model accuracy, and in several cases accurate models with longer matrices could not be built (see Supplement).

BoltzNet models robust to input data

To assess model stability with respect to input data, for all five calibrated TFs we built models for subsets of the strongest called peaks (Figures S43–47) and subsets of available experiments (Figures S48–52) and assessed accuracy as above. The impact of limiting the number of peaks varied by TF. For the majority of cases, accurate models could be built with as few as the five strongest called peaks (PdhR, GlnG, AllR, UlaR), and in some cases the three strongest peaks (PdhR, GlnG). And moderately accurate models could be built with as few as two strong peaks. In contrast, while Nac models were robust to removal of more than 50% of the 504 called peaks, models for Nac with 100 or fewer subsampled peaks could not be generated.

Sub-selection of experiments had no impact on models for PdhR, AllR, GlnG, and Nac with equivalent accuracy on the prediction of binding energy as compared to BLI measurements. Only UlaR displayed a sensitivity to the selection of experiments. Maximum accuracy was achieved with a combination of in vitro and in vivo experiments (R2 = 0.8) while subsets of experiments displayed more moderate accuracy (0.58 < R2 < 0.67). Importantly, models could be built for all five TFs from subsampled pairs of in vivo experiments, whether native or inducible promoters, and performed as well as models from the full set of experiments for four of the five TFs, and with acceptable accuracy for UlaR (we discuss the behavior of UlaR in Supplementary Material).

BoltzNet outperforms existing tools

We sought to compare BoltzNet with six different tools: ProBound, BPNet, Catchitt, DeepBind, DeepLift and FactorNet. Not all tools were available, and different tools provided different capabilities (Supplementary Table S2). We were thus able to compare BoltzNet to three state-of-the-art neural network tools: ProBound, BPNet, and Catchitt (see Supplement for full details).

ProBound is the only tool compared that predicts an explicit binding energy and binding energy matrix. ProBound is based on a custom maximum-likelihood framework that models both the biophysical process of TF-DNA binding as well as the biophysical process of experimental binding enrichment. For ProBound, we compared binding energy weight matrices, the relationship between sequence and binding affinity across the genome, and the accuracy of predicting binding sequence energy for the sequences measured by BLI in Fig. 5 (Figure S59). ProBound matrixes for PdhR, Nac, and UlaR captured positive binding energy contributions for the expected core binding sequences and relative positions, although bases with negative weights were often more uniform. Matrices for GlnG and AllR failed to capture the expected core sequence. Predicted binding energy vs coverage displayed the expected sigmoidal relationship, with the exception of GlnG. Most importantly, ProBound performed poorly in predicting the binding energy of sequences measured by BLI (Fig. 5). In nearly all cases, ProBound performed poorly on this test (0 < R2 0.39). The one exception was PdhR where ProBound predicted more accurately (R2 = 0.76), but still less accurately than the BoltzNet model with same five training experiments (R2 = 0.93). Notably, AllR displayed the lowest variance relationship between coverage an ΔΔG on the genome, but the lowest accuracy on the independent test (Figure S59). The results reveal that ProBound could differentiate between expected peaks and non-specific sequences, but often failed to predict difference in affinity between specific sequences and between non-specific sequences.

BPNet is a deep convolutional neural network designed to predict genome coverage from sequence13. It does not explicitly generate a model of TF-DNA binding affinity. Instead, additional tools have been developed to interpret the behavior of the model: TF_MoDISco45 is used to predict a PFM binding model, and SHAP46 is used to assign each nucleotide an importance value. In the absence of a predicted affinity score for sequences, we calculated the sum of SHAP scores (see Supplement). Moreover, BPNet could only be trained on one experiment at a time, so we generated one model per experiment. We first compared the PFM derived from the BoltzNet binding affinity matrix with the TF-MoDISco PFM (Figure S60A). Experiments with fewer peaks, even if they generated models, often failed to generate motifs. For models with PFMs, there was often excellent agreement with the PFMs from BoltzNet. We next tested the ability of BPNet to model binding affinity on the test set (Figure S60B). In the vast majority of cases, coverage across the genome could be modeled as a sigmoidal function of SHAP Sum. Finally we tested the ability of BPNet to predict binding affinity on sequences never seen during training (Figure S61). To do so, we ran predictions using all BPNet models on the novel designed sequences from Fig. 5. BPNet performed worse than BoltzNet in all comparison for all TFs. As with ProBound, BPNet could differentiate between expected peaks and non-specific sequences, but often failed to predict difference in affinity between specific sequences and between non-specific sequences.

Catchitt, unlike BoltzNet, ProBound and BPNet, is not a tool for binding motif/weight matrix discovery47. For training, Catchitt requires a pre-existing PFM model of binding for a TF. It then combines this model with the location of ChIP-Seq binding sites, chromosome accessibility data (typically from DNAse-Seq or ATAC-Seq), and optional DNA methylation data. To generate Catchitt predictions, we provided a PFM model derived from MEME run on the called peaks for each TF, and applied Catchitt to called peaks for each experiment. The results reveal that the Catchitt probability of binding was not predictive of peak binding coverage (Figure S62). These results are consistent with our results that demonstrate that PFM matrices are not accurate predictors of coverage and binding affinity for our ChIP-Seq data.

Discussion

We report the mapping of in vivo DNA binding for 139 E. coli TFs using ChIP-Seq. We also describe BoltzNet, a novel neural network that interprets ChIP-Seq data through the lens of a biophysical model of TF-DNA binding. Together, our results suggest a new paradigm for developing interpretable neural networks, and an alternative paradigm for describing TF-DNA binding. Most analyses of ChIP-Seq data catalog specific binding sequences, often by focusing on the most enriched binding regions. This effort is complicated by variability between experiments. Our data suggest that strong and weak binding exists on a spectrum of affinity to any sequence. Consequently, the notion of a discrete set of “canonical” TF binding sites is incomplete. A complete picture must predict binding affinity to any sequence, interpret the results of individual experiments, account for differences between experiments, and enable the quantitative design of novel binding sites.

We designed BoltzNet for these purposes. BoltzNet is trained on ChIP-Seq data and can predict coverage from any DNA sequence. However, the primary goal of BoltzNet is to learn an underlying thermodynamic model of TF-DNA binding affinity. BoltzNet is thus a bridge between high-throughput genomics and detailed biophysics. The model learns a single set of parameters that explain affinity across multiple genomic experiments. These parameters can then be used to design new sites with quantitative accuracy in measurements of purified protein and DNA. BoltzNet also learns a mapping from affinity to ChIP-Seq coverage that implicitly accounts for differences in experimental conditions, including TF concentration.

Crucially, we designed the architecture of BoltzNet for the physical process being modeled rather than the process of learning the model. This resulted in critical differences between BoltzNet and prior applications of CNNs to genomic data. One key difference was the use of an exponential activation function which is not typical in CNNs where it is common to re-scale and zero-center internal outputs to facilitate backpropagation. In the case of BoltzNet, the exponential activation was necessary to internally represent biophysically meaningful values, and empirically it was required to learn accurate models with only one weight matrix. By explicitly modeling a biophysical process, BoltzNet avoids issues of overparameterization and interpretability associated with black-box neural networks.

Our approach is more aligned with biophysical methods like ProBound but has significant differences. BoltzNet is designed for prokaryotic ChIP-Seq while ProBound is designed for eukaryotic SELEX. BoltzNet also only models TF-DNA binding in biophysical detail. Coverage, by contrast, is modeled as a functional mapping motivated by our prior work22. This significantly simplifies the BoltzNet model. BoltzNet then leverages the feature selection power of convolutions and the function approximation power of fully connected neural networks. By taking advantage of the flexibility and optimization engines of modern neural network frameworks, BoltzNet is also more easily trained, used, and adapted. BoltzNet thus acts as an important bridge between neural networks and thermodynamic models and provides a foundation for future biophysically inspired CNNs.

The application of BoltzNet to 124 E. coli TFs provides broad insight into prokaryotic TF-DNA interactions. Our results are consistent with previous reports that TF-DNA binding in prokaryotes is driven by localized interactions that can be modeled with a single energy matrix48. They also highlight the role of degenerate residues in sculpting overall affinity. Such residues may only be present in a few strong sites, and thus not apparent in PFMs. Our findings also reframe the discussion of weak and strong binding sites into real physical units. In doing so, they highlight the physiological relevance of weak sites and stress the importance of deep ChIP-Seq coverage to reveal weaker sites that are nonetheless important for understanding specificity. One important observation is that clusters of weaker sites can lead to occupancy equivalent to that of a single strong site, consistent with reports in other organisms31. Finally, our results speak to the long-standing question of the cellular localization of TFs36,41. For five TFs, we estimate >79% of protein is bound to the genome as compared to being free in solution. This conclusion depends on estimates of cell volume and only considers predictions in 101 bp sequences. It does not account for longer range interactions or sequence context. It is nonetheless consistent with previous reports and argues that “non-specific” genome binding is an important factor in gene regulation36.

While we targeted all 318 TFs in E. coli for mapping, for 179 TFs we were not able to generate replicate ChIP-Seq experiments that both passed quality control filters (Supplementary Data 1). These TFs represent an important gap to fill. In most cases we can only speculate as to the reasons for the failure for ChIP-Seq mapping. In some cases, we expect that our single consistent growth condition did not support binding by the TF, even when induced. However, as described in the Supplement, one important finding from our results is in vitro ChIP-Seq provides an equally accurate measure of binding energy as in vivo experiments. Moreover, as discussed in the Supplement, we expect that in vitro ChIP-Seq data may facilitate training of models for some of the 15 of 139 TFs with replicate in vivo data but no BoltzNet model. We thus expect that a future strategy of mapping the remaining 194 TFs without BoltzNet models will yield a complete and consistent picture of TF binding energy for E. coli.

Whether BoltzNet can be applied to other organisms is an important question for future study. Even within prokaryotes, more complex binding configurations including protein-protein interactions and DNA-looping are known to be important. An important advantage of BoltzNet is that it can be readily extended to encompass these additional interactions. Moreover, interactions can be systematically added to BoltzNet to test each hypothesis and determine the minimal model required for accuracy and generalization.

Finally, while our results do not speak to the potential functional rules of the TF-DNA binding we have uncovered, the thermodynamic framework used can extend to gene regulation16, and we anticipate analogous extensions to BoltzNet to enable the study of gene expression.

Methods

ChIP-Seq protocol

We developed a standardized ChIP-seq protocol based on previous methods (Figure S3)7,49. A more detailed protocol can be found in Supplementary Material (see ChIP-Seq). At a high level, we grew cells with different tagged TFs (see Strain Construction in Supplement and (Supplementary Data 5) until log-phase in M9 minimal media supplemented with 0.4% glycerol as a carbon source. We crosslinked TFs to DNA and performed washes to prepare cells for sonication on a Covaris S2, which lysed cells and sheared DNA into fragments with a tight length distribution. We used ChIP-grade monoclonal antibodies in immunoprecipitation that target our engineered tags to specifically pull-down DNA bound to the TF of interest. This DNA was purified and prepared for NGS on Illumina’s NextSeq platform.

ChIP-Seq analysis pipeline

We developed a standardized pipeline for identifying enriched regions from ChIP-Seq data based on previous methods7,49,50. This pipeline is described graphically in (Figure S5A). At a high level, we started by performing quality control on raw sequencing reads, before pruning Illumina adapter sequences from read ends, and aligning to the E. coli reference genome (Genbank Accession U00096.3). We calculated coverage from alignments as the number of reads aligning to each strand at each position, which was used to identify statistically enriched regions of coverage. We applied several filters to these regions, including: (1) filtering for the expected signature of forward and reverse coverage; (2) filtering for background enrichment in control experiments; and (3) filtering for ChIP-Seq specific artifacts that are not apparent in controls (Supplementary Data 4). After filtering likely spurious regions, we performed ChIP-Seq-specific quality control to verify tagging of the correct TF. Results of all analyses were imported to a MySQL database.

After all samples of a given TF have been analyzed, we removed experiments with poor background coverage by filtering those with < 90% of bases covered with at least 1 read; as well as experiments with poor enrichment by removing experiments where the strongest region was < 10-fold enriched. For TFs with at least 2 experiments passing this filter, we merged the output regions from each experiment into a unified binding region set (Figure S5B). We found all overlapping regions and kept any that were found in at least two experiments, or one experiment and contains a RegulonDB known binding site.

Mathematical model of TF-DNA binding and ChIP coverage

We model a ChIP-seq experiment as a two-step process. The first step is TF binding to DNA, which we analyze through the lens of a previously described thermodynamic model of protein-DNA interaction16,17,18,20 resulting in the estimated probability that any given sequence will be bound by a TF at thermal equilibrium. The second step models ChIP coverage as a function of the probability of binding which we have previously shown can be treated as a signal convolution process22,28.

Thermodynamic model of binding to a single site

To analyze TF-DNA binding, we seek to model the sequence-specific binding energy of a TF to DNA. In the simplest case, we consider a system consisting of one sequence of interest and NNS non-specific sites. We then consider NTF transcription factors, each of which can be either be bound to the sequence of interest with energy εseq or occupy a non-specific site with energy εNS. By convention, more negative energies are more favorable. We further assume that occupancy of these states is in thermal equilibrium over the timescales of interest for our analysis, motivated by the fact that speed of binding reactions is very fast relative to the timescale of a typical ChIP experiment.

The probability that the sequence of interest will be bound by a TF can be calculated via the Boltzmann distribution16. This is accomplished by considering two states for the system: (1) an “unbound” state where all NTF molecules occupy “non-specific” sites, and (2) a “bound” state where NTF – 1 TF molecules occupy non-specific sites, and one TF molecule is bound to the sequence of interest. Each state is associated with a multiplicity, Z, which is the number of configurations by which that state can be realized. For example, for the unbound state, Zunbound is the number of ways in which NTF TFs can be arranged in NNS non-specific sites. The energy of each configuration can be calculated by summing the energies of the NTF TFs in that configuration. For example, for any unbound configuration:

and for any bound configuration:

For each configuration, we then calculate the Boltzmann factor (also called statistical weight), defined as the exponential of the negative energy relative to kbT for that configuration where kb is the Boltzmann constant and T is temperature (in K):

For the following, we assume that all energies are given in units of kbT so that this term will be omitted, and energies will be unitless. The probability that the system will be in the bound state can then be calculated as the sum of the Boltzmann factors for all bound configurations divided by the sum of the Boltzmann factors for all configurations:

(where, as noted above, we assume energies are in units of kbT). The denominator of Eq. 5 is the partition function of the system. As shown previously16,18 (see also Thermodynamic Model of Binding to a Single Site in Supplement) for the simple system of one sequence and NNS non-specific sites, Eq. 5 can be simplified to:

Where Δε is defined as the difference in energy between a single TF bound to the specific sequence and the TF occupying a non-specific site:

Δε can be interpreted as the energy released when a TF transitions from a non-specific site to the specific sequence, or conversely the energy that must be provided to dislodge a TF from the specific sequence to a non-specific site. From Eq. 6 more negative Δε increases Pbound and thus reflects a sequence with higher affinity to the TF relative to non-specific sites.

Relationship to Hill function

Equation 6 can also be related to a unimolecular model of TF binding to a DNA sequence:

which can be used to derive the familiar Hill function form for TF binding at equilibrium (see Relationship to Hill Function in Supplement):

where [TF]eq is the concentration of free TF at equilibrium, Pbound is the probability that the DNA is bound to TF, and KD is the dissociation equilibrium constant, or the inverse of the association equilibrium constant, KA:

KD (and KA) can in turn be related to the Gibbs free energy of the reaction (see Equilibrium Constant Relation to Free Energy in Supplement):

where ΔG0 is the Gibbs free energy associated with the reaction under standard conditions in which all reactants are present a 1 M, NA is Avogadro’s number or the number of molecules in 1 mole, and \({\mathbb{C}}\) =\(\,\frac{{\left[{TF}\right]}_{0}{\left[{DNA}\right]}_{0}}{{\left[{TFDNA}\right]}_{0}}=1\,{{\rm{mol}}}\) where [x] is 1 M for all species X (see Supplement).

From this, we can recognize that:

which is the change in energy of a molecule in units of kbT (and it thus unitless). We can thus rewrite Eq. 11 as:

and:

providing an interpretation of the equilibrium constants in terms of the change in energy (in units of kbT) when a single TF molecule binds DNA).

Probability of TF binding to a sequence with multiple sites

A more realistic model assumes that each of Nregion positions in a DNA sequence can be considered as an individual binding site i, each with their own energy εi. As before, there are NTF proteins available to bind any site within this region, and NNS nonspecific sites that can be bound each with energy εNS. We further make the simplifying assumption that only 1 TF can bind the sequence at any time. Determining the probability of binding anywhere in this sequence requires deriving the appropriate Boltzmann factors and multiplicities where the sequence is or is not bound, as in Eq. 4. As shown in Probability of TF Binding to a Sequence with Multiple Sites, the corresponding Pbound can be shown to be:

where Δεi = εi - εNS as in Eq. 6.

If we then consider the entire sequence as a single potential binding site with an effective binding energy of Δεeff, we can relate Eqs. 6 and 15 to derive:

which implies that the effective energy of the sequence is related to the log of the \({e}^{-{\triangle {{\rm{\varepsilon }}}}_{i}}\) of each site in the sequence:

Additive model of binding energy

In general, the energy of binding of proteins to DNA could depend on the underlying sequence through numerous complex non-linear interactions. However, several studies have demonstrated that simple additive “energy matrix models” models of are often sufficient to describe TF-DNA binding energies15,17,18,19,27. In such models, each base in a sequence contributes an additive term to the overall binding energy. Such models can be seen as first-order Taylor Series approximations to more complex models. Mathematically, we implement such models using one-hot strategy to represent a sequence of length L as an 4xL matrix Sij, where i represents the four bases (A,C,G,T) and Sij = 1 if an only if the base at position j is i. The binding energy matrix Mij in turn contains 4xL values where Mij is the energy contributed by base i at position j. The total energy of the sequence is then the inner product of both matrices:

Signal processing model of ChIP-Seq coverage

We have previously shown that ChIP-Seq coverage can be approached from a signal processing perspective as a signal convolution22,28. In this context, an impulse signal represents a binding site and the process of ChIP-seq emits a corresponding impulse response. The magnitude of the impulse signal is assumed to be proportional to the probability that the site is bound. The impulse response spreads out the signal of the binding site due to the shearing and sequencing process of ChIP-Seq. An analysis of this process revealed that the impulse response can be modeled as an extreme value distribution, resulting in an impulse response that follows a Gumbel distribution22. The sum of impulse responses from all TF binding sites in a region generates an observed ChIP-seq enrichment peak.

BoltzNet architecture and implementation

BoltzNet is a neural network designed to predict ChIP coverage from sequence by directly estimating a model of TF-DNA binding energy. Following the mathematical model described in the previous section, BoltzNet consists of two components: one that models the processes of TF-DNA binding and one that models coverage in ChIP experiments (Fig. 1A). BoltzNet is implemented using TensorFlow v2.7.0.

TF-binding component

The TF-DNA binding component takes DNA sequence as input and models the effective equilibrium association constant of TF binding. This component is a specifically designed convolution model. DNA sequences are input using one-hot encoding, as described above, to create a 4xL matrix where L is the length of the sequence. To model TF-DNA binding in either forward or reverse orientation, one-hot versions of the forward and reverse complemented strands of the input sequence are then concatenated together to generate a 4x(2 L) matrix. This matrix is then input to a convolution layer.

The BoltzNet convolution layer follows a specific biophysically motivated design: it consists of a single convolution weight matrix (kernel), with a bias term, that feeds into an exponential activation function. We use a single convolution weight matrix, w, of length 25 (the size of the matrix is a hyperparameter that can be modified) to model the energy of binding to each 25-mer in an input sequence relative to a constant reference energy:

where sij is the one-hot encoded 25-mer. The motifs length is a parameter that can be modified at the time of building a model. A matrix of length 25 was selected as the majority of known motifs for E. coli in RegulonDB are less then 25 bp in length (Figure S16A). Out of 97 motifs in RegulonDB, the motifs for only 3 TFs are longer than 25 bp, and in these three cases the RegulonDB motifs appear to include repeats of a core motifs (Figure S16B–D). (In all three cases, the Boltznet models for these three TFs learn a shorter motif consistent with this interpretation). We discuss an analysis of the impact of the weight matrix length in the main text and below.

Because positive values of weights contribute positively to neural network outputs, the weight matrix models the negative of the relative binding energy.

An exponential activation function is then used to generate the exponentiated energies required by the Boltzmann distribution, so that the output of the convolution layer models the exponentiated relative energy at each position, p, of a sequence.

Exponential activations are not typical in CNNs where the values of internal layers are not intrinsically meaningful, and the common practice is to minimize and zero-center internal outputs to facilitate backpropagation. In the case of BoltzNet, it is key to ensuring that internal layers represent verifiable physical values.

The output of the convolution is then passed through two pooling layers. The first pooling layer, SumStrands, sums the contribution from each strand at each position (implemented using a tailored 2D Convolution layer). The second sums the value at each position of the SumStrands layer and divides this value by a constant, Cave, that depends on the length of the SumStrands layer (implemented using a 2D Global Average Pooling layer). We refer to the output of the final pooling layer as the Affinity Score of the sequence, and mirroring Eq. 16, we interpret this score as the exponent of an effective weight, Δweff, for the sequence:

Then, we relate Eq. 22 with Eq. 17 using Eq. 20 to derive:

ChIP coverage component

The second component takes the output of the final pooling layer as input and models the coverage in one or more ChIP experiments as a function of this value. This component follows the signal processing model of ChIP-Seq described above. In this context, the connection between \(\Delta {\varepsilon }_{{eff}}\) for a sequence and expected coverage involves two transformations. First, from Eq. 6, \(\Delta {\varepsilon }_{{eff}}\) implies a probability of binding. Second, binding to the sequence gives rise to impulse response of coverage that is proportional to Pbound, and coverages from nearby sites combine additively (see above). This two-step process implies a function from 1/KA to coverage that is monotonically increasing and smooth, and that differences in coverage between different experiments for the same site are expected to be due in large part to differences in TF protein concentration which alter Pbound (via Eq. 15), and differences in IP efficiency which alter the proportionality between coverage and Pbound.

We learn this function for each experiment using a fully connected neural network. This approach takes advantage of the well-known universal function approximator nature of fully connected neural networks with at least one hidden layer with non-linear activations29. BoltzNet employs a neural network with one input layer with one node, one hidden layer with 140 nodes (the width of the middle layer is a hyperparameter that can be modified), and one output layer with one node per experiment. The input and hidden layer nodes use Leaky ReLU activation functions, while the output layer uses a linear activation function appropriate for regression. Both deep (multiple hidden layers) and wide (few hidden layers with many neurons) neural networks have the capability for universal function approximation, with deep neural networks learning certain classes of functions more efficiently51,52,53,54 at the expense of potential vanishing gradients55. In the case of BoltzNet, the expected function does not fall into the class of functions that are expected to require a deep architecture. And empirically, the use of a deep architecture did not outperform the architecture with one hidden layer.

BoltzNet training

BoltzNet is trained using a set of training sequences and associated coverage values. Training sequences consist of all the called enriched regions (see ChIP-Seq Analysis Pipeline) for a TF (positive samples) as well as 5,000 randomly selected genomic regions (negative samples). Sequences of 101 bp are used consisting of 50 bp on either side of the center position of a sequence. For positive samples, the center position is the location of maximum coverage for a called region and the coverage value is the maximum coverage across the region of the sequence in each experiment after masking known artifacts (see Filtering of Artifacts), normalized to 1 where 1 is the strongest region. For negative samples, the center positions are chosen randomly from all genomic positions that are at least 500 bp from any positive sample and the coverage value is set to 0 in all experiments.

To increase model generalization, we augment positive training samples using circular shift permutation56. Each positive sequence is augmented with two additional sequences – one sequence shifted 1 bp in the 5’ direction and one shifted 1 bp in the 3’ direction. Each positive sequence is thus represented three times in the training set – once with the original sequence and twice with permuted sequences. The coverage values for all three sequences are the same as the original sequence. To test the impact of this data augmentation, we built models for PdhR, AllR, GlnG, Nac, and UlaR without augmentation (Figure S64). In the cases of PdhR, AllR, GlnG, and Nac, data augmentation did not dramatically alter the model learned and the accuracy on the training set, genome, and predicted sequence energies. In contrast, for UlaR a model satisfying our accuracy requirements could not be found during training without augmentation (despite multiple build attempts).

The training of neural network parameters through gradient descent via backpropagation is sensitive to the starting values of the parameters. Initial values may constrain models to regions of the parameter space that are less optimal. To address this, we train BoltzNet in two stages. First, we pre-train 10-15 models (implemented with multiple-process support) for a restricted number of epochs on all the positive data and number of negative samples equal to the number of called regions times 3. Second, the pre-trained model with the highest accuracy then underwent additional training on the entire positive and negative training set. Empirically, we observed that this process increased the probability that the binding sites in each sequence associated with higher affinity binding energies would be discovered. However, the limited number of negative samples used during pre-training typically meant that pre-trained models would have a greater number of false positives on the full genome sequence. Full training on the best pre-trained model with all negative sequences typically increased model specificity on the full genome by further learning parameters associated with non-specific binding energies. If pre-training could not identify a model that fit the pre-training data with an R2 > 0.6, no model was created.

All training was performed using the Adam optimizer57, with an exponential decay learning rate schedule, a mean-squared error loss function, a batch size of 256, and early stopping with patience of 100 epochs. Pre-training was performed over a maximum of 1000 epochs. Full training was performed over a maximum of 4500 epochs.

Regularization was essential for accurate model learning and prediction. L1 kernel, activity, and bias regularization were applied to both the convolutional layer and all neural network layers. Conversely, since our goal was to train deterministic models whose predictions and parameters could be experimentally verified, we did not incorporate Batch Normalization layers which would re-scale and re-center parameters58. Nor did we incorporate Dropout layers59 which can lead to non-deterministic results during training. Empirically, neither was required for accurate training of our models.

We applied BoltzNet to in vivo ChIP-Seq data for all 139 TFs and generated 124 models that passed two accuracy criteria: R2 > 0.6 on predicting coverage on the training set and specificity of more than 60% when applied to the entire genome. Of the models for the 14 TFs that do not pass, 12 failed to model the training set with R2 > 0.6 (allS, csgD, csiR, gadX, hcaR, hipB, maze, nanR, stpA, yafC, yfiE, yjgJ) while the remaining two (aaeR, rutR) failed to achieve >60% specificity when applied to the entire genome (specificity of 48% and 40% respectively).

Calculating PFMs from weight matrices

To calculate Position Frequency Matrices from convolution weight matrices, we used a previously described method30. The method counts nucleotide frequencies in sequence sites that score above a threshold when multiplied by the weight matrix. For a given weight matrix, we scan all positive training sequences and identify all locations that score above some fraction of the maximum score for that matrix (typically 0.8 maximum). The frequencies of bases in each position of all such locations is used to construct the corresponding PFM. All sequence logos were generated using Logomaker60.

Calculation of base contributions

As described above, the weight matrix provides a direct prediction of the relative contribution of every base at any binding location and orientation, the exponentiation of which provides a measure of the affinity at each location and orientation. The affinity of the whole sequence is determined by the affinity of all locations and orientations. Any given base thus contributes to the overall affinity of the sequence through all overlapping binding locations in both orientations. To calculate a measure of this contribution, for every base we calculate the weight of the base in each overlapping binding location multiplied by the model affinity (exponentiated kernel score) of that location and sum these values over overlapping locations. These values are then used to scale the base in plots of base contributions.

Known binding sites and the alignment of PFMs

The set of known sites was derived from RegulonDB v12.023 based on sites for 36 TFs with strong classical binding evidence, and not dependent on other high-throughput datasets. No ChIP-Seq data from any other study was used in our analysis. This selection was made to ensure that only high-confidence binding sites were considered. To align PFMs we transformed frequency matrices into information matrices and compared every possible motif alignment (including reverse-complementing one motif, see Motif Comparison). We obtained PFMs from RegulonDB v12.023 based on sites for 36 TFs with strong classical binding evidence for comparison to PFMs from BoltzNet, allowing us to demonstrate that weight matrices can recover existing PFMs, while providing a more quantitative explanation of TF sequence preference.

Prediction of novel binding sites

For each TF, we selected a 101 bp reference sequence. This sequence was chosen as the strongest enriched region with a single binding site. We then manually selected 10 bases to vary in each sequence, focusing on accessory bases outside the bases that were the most conserved. We generated all combinations of all of the 10 bases while keeping the remaining bases the same. This resulted in a range of predicted affinities. We selected sequences from this range, including where possible predicted sites stronger than the strongest singleton genomic site. These selected sequences were then trimmed to 61 bases for ordering oligos. The trimmed sequences were rerun through BoltzNet (with Ns at trimmed positions) to generate final predictions for all selected sequences. Oligos with the selected sequences were then ordered from Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT), and used for validation with either Library-ChIP and/or BioLayer Interferometry.

Library-ChIP

Library-ChIP is performed according to previously published methods7,49,50. We used the same tagged-TF strains that were used in ChIP-seq, carrying an additional single-copy plasmid containing one of ~100 different designed binding sites (see Library-ChIP Library Construction). Cultures were treated identically to those in ChIP-Seq experiments up through sonication. After pelleting the sonicated lysate, we saved ~10% of the DNA-containing supernatant as a pre-IP control. The remaining 90% of supernatant went through immunoprecipitation as a normal ChIP-Seq experiment would. Both the pre- and post-IP samples underwent protein digestion, and DNA was purified. DNA was converted into NGS libraries using a custom protocol, then pooled for sequencing in the same manner as our ChIP-Seq samples (see Library-ChIP Library Prep and Pooling). After retrieving the sequencing reads, we counted the abundance of each designed sequence and normalized by sequencing depth, then took the ratio of post-IP/pre-IP counts as the Library-ChIP enrichment (see Analysis).

Protein purification

To purify proteins for in vitro experiments, we grew 500 mL cultures of each TF-6xHis construct (see Inducible Tagging for in vitro Experiments). After cultures reached log-phase, we induced TF expression by adding rhamnose to a final volume of 0.2% and allowed induction to continue overnight. We purified TFs with Qiagen’s Ni-NTA Spin Kit (#31314) and dialyzed against a storage buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 200 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 50% glycerol61; GlnG was stored in 10 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM EDTA, 50% glycerol62) using desalting columns (Cytiva cat. #17085101). TF expression and purity were assessed with SDS-PAGE and concentrations were determined with the Bradford Assay using BSA as a standard. 10μM stocks were made in respective storage buffers and proteins were stored at -80 °C for downstream experiments.

BioLayer Interferometry

BLI was carried out using a previously published protocol that we optimized for our application63,64. We loaded biotinylated DNA on an Octet Red 384 using Streptavidin Tips (Sartorius cat. #18-5020). All BLI was performed at 30 °C with shaking at 1000 rpm in binding buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 120 mM KCl, 5% glycerol, and added 0.05% Tween-20 as a blocking agent65). A 1:1 ratio of 10 nM biotin and biotinylated-dsDNA in binding buffer was used for loading and different TF concentrations were used as analyte. For specific DNAs, 50-100 nM proved to be a sufficient upper-limit of TF concentration and a 2-fold serial dilution was used from that upper limit for a total of 6 TF concentrations and a 0 nM TF reference. For non-specific DNAs, more protein was needed for an observable signal and we used TF at 100, 250, 500, 750 nM, and 1 uM in addition to the 0 nM TF reference. We performed an initial 10 min pre-incubation where the tips are soaked in buffer A, followed by a 60 s baseline reading. We loaded DNAs for 2 min and took another baseline reading for 60 s to align traces before TF binding. TF was allowed to bind to probe-bound DNAs with a 10 min association step before probes were returned to a well of buffer to monitor unbinding in a 15 min dissociation phase. The oligonucleotide sequences used for BLI are provided in Supplementary Data 7, and the TF-DNA pairs tested in BLI are provided in Supplementary Data 8.

This assay followed the design for fitting with the 1:1 binding model, which corresponds to a unimolecular TF-DNA binding reaction. We implemented this model in MATLAB to estimate dissociation constants for each TF-DNA pair and calculated binding energies from Eq. 12 (see Analyzing BLI).

Statistics and reproducibility

We required that a TF have at least two replicate ChIP-Seq experiments that pass all quality control filters to be further considered. Reproducibility was verified by ensuring that the coverage profile between replicates was correlated and that the peaks called between replicates were consistent. Due to differences in protein levels, different experiments were expected to result in different numbers of peaks called, but the strongest peaks in all replicates were required to agree and to have the same relative peak heights. Only the peaks called in at least two replicate experiments were considered for further analysis. This ensured that any called novel peaks were replicated. No data passing these requirements was excluded from analysis. No statistical method was used to predetermine sample size. Experiments were not randomized. Group allocation was not performed as part of our analysis.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The ChIP-Seq and Library-ChIP data generated in this study have been deposited in NCBI’s Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) under GEODataSeries Accession GSE268698. We have provided the associated GEODataSample accessions for each experiment in this series in Supplementary Data 9. U00096.3 [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/U00096.3/]. The union peaks and weight matrices for each TF, as well as the underlying peaks from each experiment used to generate the union peaks have been deposited in RegulonDB at: https://regulondb.ccg.unam.mx/ht/dataset/TFBINDING/source=GALAGAN. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. Strains are available upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

All code is available through CodeOcean at https://codeocean.com/capsule/9709912/tree/v1.

References

Santos-Zavaleta, A. et al. RegulonDB v 10.5: tackling challenges to unify classic and high throughput knowledge of gene regulation in E. coli K-12. Nucleic Acids Res 47, D212–D220 (2019).

Keseler, I. M. et al. EcoCyc: fusing model organism databases with systems biology. Nucleic Acids Res 41, D605–D612 (2013).

Mejia-Almonte, C. et al. Redefining fundamental concepts of transcription initiation in bacteria. Nat. Rev. Genet. (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41576-020-0254-8

Trouillon, J., Doubleday, P. F. & Sauer, U. Genomic footprinting uncovers global transcription factor responses to amino acids in Escherichia coli. Cell Syst (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cels.2023.09.003

Aquino, P. et al. Coordinated regulation of acid resistance in Escherichia coli. BMC Syst. Biol. 11, 1 (2017).

Jaini, S. et al. in Molecular Genetics of Mycobacteria, 2nd Edition (eds G. Hatfull & W. R. Jacobs, Jr.) (ASM Press, 2014).

Galagan, J. E. et al. The Mycobacterium tuberculosis regulatory network and hypoxia. Nature 499, 178–183 (2013).

Minch, K. J. et al. The DNA-binding network of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat. Commun. 6, 5829 (2015).

Tanay, A. Extensive low-affinity transcriptional interactions in the yeast genome. Genome Res. 16, 962–972 (2006).

Kribelbauer, J. F., Rastogi, C., Bussemaker, H. J. & Mann, R. S. Low-Affinity Binding Sites and the Transcription Factor Specificity Paradox in Eukaryotes. Annu Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 35, 357–379 (2019).

Shahein, A. et al. Systematic analysis of low-affinity transcription factor binding site clusters in vitro and in vivo establishes their functional relevance. Nat. Commun. 13, 5273 (2022).

Quang, D. & Xie, X. FactorNet: A deep learning framework for predicting cell type specific transcription factor binding from nucleotide-resolution sequential data. Methods 166, 40–47 (2019).

Avsec, Z. et al. Base-resolution models of transcription-factor binding reveal soft motif syntax. Nat. Genet. 53, 354–366 (2021).

Alipanahi, B., Delong, A., Weirauch, M. T. & Frey, B. J. Predicting the sequence specificities of DNA- and RNA-binding proteins by deep learning. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 831–838 (2015).

Zhao, Y. & Stormo, G. D. Quantitative analysis demonstrates most transcription factors require only simple models of specificity. Nat. Biotechnol. 29, 480–483 (2011).

Bintu, L. et al. Transcriptional regulation by the numbers: models. Curr. Opin. Genet Dev. 15, 116–124 (2005).

Barnes, S. L., Belliveau, N. M., Ireland, W. T., Kinney, J. B. & Phillips, R. Mapping DNA sequence to transcription factor binding energy in vivo. PLoS computational Biol. 15, e1006226 (2019).

Brewster, R. C., Jones, D. L. & Phillips, R. Tuning promoter strength through RNA polymerase binding site design in Escherichia coli. PLoS computational Biol. 8, e1002811 (2012).

Kinney, J. B., Murugan, A., Callan, C. G. Jr. & Cox, E. C. Using deep sequencing to characterize the biophysical mechanism of a transcriptional regulatory sequence. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 9158–9163 (2010).

Bintu, L. et al. Transcriptional regulation by the numbers: applications. Curr. Opin. Genet Dev. 15, 125–135 (2005).

Rube, H. T. et al. Prediction of protein-ligand binding affinity from sequencing data with interpretable machine learning. Nat. Biotechnol. 40, 1520–1527 (2022).

Gomes, A. L. et al. Decoding ChIP-seq with a double-binding signal refines binding peaks to single-nucleotides and predicts cooperative interaction. Genome Res. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.161711.113 (2014).

Salgado, H. et al. RegulonDB v12.0: a comprehensive resource of transcriptional regulation in E. coli K-12. Nucleic Acids Res 52, D255–D264 (2024).

Holme, P. Rare and everywhere: Perspectives on scale-free networks. Nat. Commun. 10, 1016 (2019).