Abstract

Inspired by the prominent redox and optical properties of natural flavins, synthetic flavins have found broad applications in organic, photochemical, and biochemical research. Tailoring these properties of flavins, however, remains a challenge. In this work, we present three pentacyclic flavins (C-PF, O-PF, and S-PF) that leverage a strategic molecular design to modify the flavin’s electronic structure. Notably, the oxygen- and sulfur-linked pentacyclic flavins (O-PF and S-PF) exhibit deep-red and NIR emission, respectively, driven by enhanced π-conjugation, substituent effects, and charge separation upon excitation. These heteroatom-incorporated pentacyclic flavins exhibit unusual quasi-reversible oxidation, expanding both optical and redox limits of synthetic flavins. Comprehensive spectroscopic, structural, and computational analyses reveal how heteroatom incorporation within this five-ring-fused system unlocks redox and optical properties of flavin-derived chromophores.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

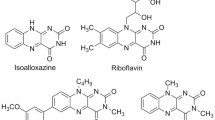

Flavins are ubiquitous in living organisms, serving as redox mediators and photoreceptors1,2. Fig. 1a illustrates three representative examples of natural flavins: riboflavin, flavin mononucleotide (FMN), and flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD)3. In all cases, a common structural feature is the three-ring-fused heterocyclic moiety — an isoalloxazine group (highlighted in light green in Fig. 1a)4. The isoalloxazine core is where electron or proton transfer takes place for biochemical redox processes3,5,6,7. Furthermore, such a tricyclic unit absorbs blue photons and emits bright-green light, enabling many flavoproteins to respond to blue light8,9.

Inspired by the redox and optical properties of natural flavins, synthetic flavins have garnered significant interest in the fields of catalysis10,11,12,13, photochemistry3,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22, chemical biology23,24,25,26,27, and electrochemistry28,29,30,31,32. Tailoring the photoluminescence of flavins has been particularly appealing due to their versatile applications as fluorescent dyes and photocatalysts. To this end, several synthetic approaches have been developed to fine-tune their electronic structure and photophysical properties33,34. These include the incorporation of Lewis acids35,36,37,38, the introduction of a positive charge to afford flavinium salts39,40,41,42,43, and substitution with electron-donating or electron-withdrawing groups (Fig. 1b)44,45,46,47,48,49. Most of these strategies have aimed to blue-shift the absorption and emission wavelengths, thereby enhancing energy and redox potentials in excited states50,51,52. As a result, the majority of synthetic flavins emit in the blue to green light range.

In contrast, only a handful of flavins emit red light (>620 nm). In 2015, the König group reported the red-light-emitting flavin by expanding the π-space of the isoalloxazine ring (Fig. 1b)53. Significant red-shifts in both absorption and emission wavelengths were observed by conjugating the parent isoalloxazine with polyaromatic hydrocarbons. This study demonstrated the potential to extend the emission properties of flavins beyond the green light.

Nevertheless, achieving NIR (>750 nm) or even deep-red (>650 nm) emission from a flavin scaffold has remained a long-standing challenge, likely due to the lack of established molecular design principles. Here, we present a molecular design to modulate the electronic structure of flavins in both their ground and excited states. The developed pentacyclic flavin scaffold enables fine-tuning of (1) π-conjugation, (2) substituent effects, and (3) charge separation upon excitation across the series. This approach has led to the examples of deep-red and NIR emissive flavins upon the incorporation of an oxygen or sulfur atom, respectively (Fig. 1c). Moreover, the developed pentacyclic flavins exhibit quasi-reversible oxidation, a feature typically absent in the parent isoalloxazine unit, broadening the inherent redox capabilities of flavins.

Results

Synthesis and characterization of O-PF

To this end, we designed a pentacyclic scaffold to induce significant changes in the electronic structure, thereby overcoming the intrinsic limits of natural or synthetic flavins in their optical and redox properties (Fig. 1d). Specifically, we hypothesized that anchoring the N(10)-phenyl group to the C(9) atom of the isoalloxazine core via a linker unit (X) would extend π-conjugation and afford a distinctive electronic structure. Furthermore, we envisioned that the identity of X (e.g., O, S, or C(Me)2) would modulate the degree of π-conjugation and introduce specific substituent effects.

In targeting the pentacyclic flavin structure, we initially focused on synthesizing the O-atom-linked variant (Fig. 2a). Nucleophilic aromatic substitution (SNAr) of 2-chloro-1,3-dinitrobenzene with 2-aminophenol, followed by intramolecular SNAr, yielded 1-nitro-10H-phenoxazine. Subsequent hydrogenation produced 10H-phenoxazine-1-amine, which underwent condensation with alloxan to form the pentacyclic scaffold, O-PF-H. For sufficient solubility in organic solvents, we introduced an n-butyl (nBu) substituent at the N(3) position, yielding the desired O-atom linked pentacyclic flavin, O-PF (Fig. 2a). The formation of the targeted five-ring-fused structure was confirmed via multinuclear NMR spectroscopy and high-resolution mass analysis (Supplementary Information).

Along with O-PF, we prepared two additional flavins as comparative analogs: N-Ph and N-Ph(OMe) (Fig. 2b). In both cases, a phenyl group was substituted at the N(10) atom to investigate the role of the O-atom linker in O-PF from the perspective of extending π-conjugation through ring fusion. In particular, methoxy-appended N-Ph(OMe) was designed to better distinguish the substituent effect of the O-atom from the π-conjugation effect. Similar to O-PF, an n-butyl group was introduced at the N(3) atom in both N-Ph and N-Ph(OMe) to ensure that any observed effects were not influenced by the N(3) substituent.

Remarkably, significant changes in absorption and emission spectra were observed across the series. While the parent compound N-Ph emits typical green light, the pentacyclic O-PF exhibits red emission (Fig. 2c). In THF, the lowest-energy absorption wavelength (λabs) of O-PF is observed at 497 nm, red-shifted by 57 nm compared to that of N-Ph (Fig. 2d). In terms of emission (λem), O-PF shows a maximum at 633 nm, whereas N-Ph exhibits the characteristic green emission of the isoalloxazine core at 529 nm (Fig. 2e). N-Ph(OMe) displays intermediate properties, with λabs at 453 nm and λem at 567 nm, likely due to the electron-donating effect of the methoxy group (Fig. 2d, e). Overall, both absorption and emission wavelengths followed the trend N-Ph < N-Ph(OMe) < O-PF, reflecting the progressive substituent effect of the O-atom and extension of π-conjugation. The experimental data support our hypothesis that employing the additional π-space and substituent effect into isoalloxazine can be achieved via the pentacyclic platform using a linker unit, such as an oxygen atom.

This significant change in optical properties was further supported by structural analysis. The solid-state structures of N-Ph and N-Ph(OMe), determined by single-crystal X-ray diffraction, revealed that the N(10)-phenyl ring in both compounds is nearly perpendicular to the isoalloxazine ring (Fig. 3a, b). The dihedral angles of C(9a)–N(10)–C(11)–C(16) are 89.2° and 86.7°, for N-Ph and N-Ph(OMe), respectively, indicating an almost orthogonal arrangement between the isoalloxazine and the N(10)-phenyl moieties (Fig. 3a, b).

a Solid-state structure of N-Ph. b Solid-state structure of N-Ph(OMe). c Solid-state structure of O-PF from multiple viewpoints. Thermal ellipsoids are set at the 50% probability level (C, gray; N, blue; O, red; H, white). The chemical bonds defining the dihedral angle are colored in red. The dotted line colored in green represents the hydrogen bond.

In stark contrast, the solid-state structure of O-PF revealed a nearly planar geometry (Fig. 3c). The dihedral angle of O-PF is 2.6°, confirming that the fused benzoxazine moiety is nearly coplanar with the isoalloxazine ring (Fig. 3c). Due to this planar conformation, an intramolecular hydrogen bonding interaction, N(1)···H(12)–C(12), was observed in the solid-state structure as revealed by single-crystal X-ray diffraction (Fig. 3c). Selected bond distances and angles within the phenoxazine core, illustrated in Fig. 3c, further corroborate the planarity of O-PF. These findings underscore the pronounced planarity and extended π-conjugation of O-PF.

Of note, in a more polar solvent, such as DMSO, the λem of O-PF was further red-shifted and observed at 670 nm, locating it in the deep-red region. By comparison, the previously reported π-space-extended flavin from the König group emits at 628 nm under similar conditions, establishing O-PF as the most red-emissive synthetic flavin to date (Fig. 1b, c). Although O-PF incorporates fewer additional benzene moieties than the König group’s example (one versus three), it still exhibits a greater red-shift in emission. These results suggest a synergistic performance of the substituent and the π-conjugation extension effects. Therefore, the finding highlights the importance of integrating substituent and π-conjugation effects to modulate the optical properties of flavins.

Synthesis and characterization of C-PF and S-PF

Encouraged by the properties of O-PF, we aimed to expand the emission window into the NIR region by exploring how the identity of the linker unit (X) influences the structural and optical properties of the pentacyclic flavin chromophores. To this end, we synthesized two isoelectronic analogs, C-PF and S-PF.

Akin to the synthesis of O-PF, the condensation of 9,9-dimethyl-9,10-dihydroacridin-4-amine or 10H-phenothiazin-1-amine with alloxan, followed by N(3)-butylation, afforded the five-ring-fused products C-PF and S-PF, respectively (Fig. 4a). Both C-PF and S-PF exhibit significantly distorted geometries in the solid state, as revealed by single-crystal X-ray diffraction analysis (Fig. 4b, c). In C-PF, the dihedral angle is 26.3°, indicating a notable loss of planarity due to the sp³- hybridized carbon at the linker (Fig. 4b). S-PF shows even greater distortion, with a dihedral angle of 36.2°, caused by the larger size of the sulfur atom (Fig. 4c)54. The bulkiness of the sulfur atom significantly alters the bond lengths and angles within the phenothiazine core. Consequently, while O-PF remains nearly planar, C-PF and S-PF adopt a substantially twisted structure to accommodate the sp³-hybridized carbon center or the voluminous sulfur atom, respectively.

a A summarized synthetic route for C-PF and S-PF. Full synthetic schemes are described in the Supplementary Information. b Solid-state structure of C-PF. c Solid-state structure of S-PF. Thermal ellipsoids are set at the 50% probability level (C, gray; N, blue; O, red; S, yellow; H, white). The chemical bonds defining the dihedral angle are colored in red. d Normalized absorption spectra of the entire series in THF. e Normalized emission spectra of the entire series in THF. f Digital image of THF solutions taken under 365 nm light. The absorption and emission spectra and digital images for N-Ph, N-Ph(OMe), and O-PF are replotted using data in Fig. 2d, e for clearer comparison with C-PF and S-PF.

The perturbed planarity of C-PF and S-PF translated into notable changes in their optical properties. In a THF solution, C-PF exhibited the λabs and λem at 468 nm and 590 nm, respectively—both red-shifted compared to those of N-Ph (Fig. 4d, e). This red-shift is attributed to the extended π-space in C-PF relative to N-Ph, despite its distorted planarity. However, compared with O-PF, the λabs and λem of C-PF remained in a higher energy region, likely due to relatively reduced π-conjugation and the absence of a substituent effect (Fig. 4d, e).

S-PF displayed particularly surprising properties. Although a blue-shift in λabs and λem was expected relative to O-PF, given the bent structure (similar to C-PF)54, S-PF instead showed the most red-shifted λabs (510 nm) and λem (718 nm) in the series. Of note, the λabs of S-PF were red-shifted by 13 nm (512.9 cm–1) compared to O-PF, while its λem was significantly red-shifted by 85 nm (1870 cm–1) (Fig. 4d, e). As a result, the Stokes shift of S-PF was 208 nm (5680 cm–1) in THF, the largest in the series. These results imply that additional factors beyond π-conjugation and substituent effects may contribute to the exceptional Stokes shift observed in S-PF. Overall, both λabs and λem followed the trend: N-Ph < N-Ph(OMe) < C-PF < O-PF < S-PF.

Solvatochromism

We hypothesized that the substantial Stokes shift observed in S-PF might result from changes in the dipole moment in the excited state. To investigate this further, we measured the absorption and emission spectra of all five compounds across six different solvents—ranging from non-polar (toluene) to highly polar (DMSO)—to assess solvent effects on their optical properties (Supplementary Information)55.

Figure 5 presents the absorption and emission spectra measured in the least and most polar solvents, toluene and DMSO, respectively. As shown in Fig. 5a, N-Ph displayed nearly solvent-independent absorption and emission properties, along with the smallest Stokes shift (3859 cm⁻¹ in DMSO) within the series. Interestingly, all compounds except N-Ph exhibited solvent-dependent emission. While the absorption spectra showed weak solvent dependence, the emission spectra of N-Ph(OMe), C-PF, O-PF, and S-PF exhibited bathochromic shifts as solvent polarity increased, with the largest Stokes shifts observed in DMSO (Fig. 5b–e and Supplementary Information). Furthermore, each compound showed distinct degrees of solvent dependence, following the order: C-PF < N-Ph(OMe) < O-PF < S-PF (Fig. 5b–e).

Thus, the Stokes shifts in DMSO are highlighted with double-headed arrows in Fig. 5. As noted, S-PF showed the largest shift, reaching an emission wavelength of 772 nm in DMSO with a Stokes shift of 6655 cm⁻¹ (262 nm). This result marks the example of an NIR-emissive synthetic flavin, highlighting the significant role of the sulfur linker and pentacyclic scaffold in tuning optical properties. Collectively, the experimental data suggest that changes in dipole moment upon electronic transition are enhanced by (1) adopting a pentacyclic structure and/or (2) incorporating a heteroatom unit (e.g., OMe, O, or S).

Computational analysis

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations were conducted to further investigate the electronic structure of the flavin derivatives and address their distinct degrees of solvent-dependent behavior (See Computational Details in the Supplementary Information)56. To optimize computational efficiency, the N(3)-butyl group was truncated to a methyl group. A benchmark study confirmed that the dispersion-corrected B3LYP functional at the Def2-TZVP//Def2-SVP level of theory was the most suitable for describing the spectroscopic properties of O-PF (Table S15)57,58,59,60,61,62. Fig. 6 illustrates the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) of the five flavin compounds synthesized in this study. Notably, the LUMO energy remains largely consistent across the series, with only a subtle deviation from N-Ph to S-PF. Furthermore, the LUMO is primarily localized on the isoalloxazine core in all compounds.

In contrast, the HOMO shows distinct variations across the series. In the pentacyclic flavins (C-PF, O-PF, and S-PF), the HOMO is primarily localized on the acridine, phenoxazine, and phenothiazine moieties, rather than on the isoalloxazine core (Fig. 6). This characteristic localization is especially pronounced in O-PF and S-PF, as the lone pairs on the oxygen and sulfur atoms contribute significantly to the HOMO.

The HOMO energy levels of N-Ph(OMe) and C-PF were destabilized by 0.315 eV and 0.223 eV, respectively, relative to that of N-Ph. These changes suggest that both the substituent effect and the additional π-conjugation introduced by ring-fusion contribute to raising the HOMO energy. As such, the HOMO of O-PF and S-PF were further destabilized by the combined influence of these factors. Consequently, the computationally predicted HOMO-LUMO gap decreases progressively from N-Ph (3.464 eV) to S-PF (2.737 eV), showing an overall difference of 0.727 eV. These results align with the experimentally observed trend in λabs values in the absorption spectra of the compounds (Figs. 6 and 4d).

Next, we examined the excited state properties of the flavins to explore the origin of the large Stokes shift observed for S-PF. Time-dependent DFT (TD-DFT) calculations on the S0 → S1 transition reveal that the primary component of the transition is driven by the HOMO → LUMO excitation (Table 1). Additionally, natural transition orbital (NTO) analysis was performed to compute the hole-electron distance (i.e., r(h-e)) for the S0 → S1 transition, which is defined as the distance between the centroids of the NTO hole and NTO electron63,64,65. For N-Ph, r(h-e) is predicted to be approximately 1 Å, indicating a local excitation within the flavin moiety and, thus, a relatively small dipole moment change upon excitation (Table 1). This aligns with the solvent-independent emission behavior observed for N-Ph (Fig. 5a). In contrast, substitution with a methoxy group (e.g., N-Ph(OMe)) or ring fusion into the pentacyclic scaffold (e.g., C-PF) significantly increases r(h-e) to 2.313 Å and 1.740 Å, respectively. These results suggest that N-Ph(OMe) and C-PF experience greater dipole moment changes upon excitation compared to N-Ph.

The enhanced r(h-e) values are consistent with the experimentally observed trends in Stokes shifts and solvatochromism, where a larger dipole moment change upon electronic transition is expected when (1) adopting a pentacyclic structure and/or (2) incorporating a heteroatom unit. Consequently, further enhanced r(h-e) values of 2.403 Å and 2.874 Å were observed for O-PF and S-PF, respectively, as a result of the combined effects of the heteroatom substitution and ring fusion. The localized electron density on the phenoxazine and phenothiazine moieties in the NTO donor (or HOMO) of O-PF and S-PF, respectively, reflects increased charge transfer character upon excitation toward the isoalloxazine-based NTO acceptor (or LUMO).

Overall, the trend in the r(h-e) agrees with the experimentally observed Stokes shifts. For example, N-Ph exhibits neither solvatochromism nor a large Stokes shift, as the electron density rearranges only marginally within the isoalloxazine moiety upon excitation, minimizing changes in the dipole moment. In contrast, for S-PF, excitation induces substantial charge separation between the phenothiazine and isoalloxazine units, leading to a larger dipole moment change and pronounced solvent-dependent emissions with an exceptionally large Stokes shift.

Based on these results, we propose that O-PF and S-PF are capable of emitting deep-red and NIR light, respectively, due to three key factors: (1) extended π-conjugation, (2) substituent effects, and (3) charge separation behavior upon excitation. These factors collectively decrease the HOMO-LUMO energy gap and induce larger Stokes shifts, enabling the development of the deep-red and NIR emissive synthetic flavins.

Electrochemical analysis

The tailored HOMO and LUMO energy levels across the series suggest that the pentacyclic flavin scaffold may exhibit expanded redox capabilities. Upon reduction, each compound displayed a nearly reversible reduction with a peak-to-peak separation around 60 mV (Fig. 7a). For N-Ph, the half-wave potential (E₁/₂) was observed at −1.12 V vs. Fc⁺/Fc, consistent with the one-electron reduction of the isoalloxazine ring5,6,66. Across the series, the E₁/₂ values followed the order: N-Ph(OMe) (−1.13 V) < N-Ph (−1.12 V) < C-PF (−1.01 V) < O-PF (−0.99 V) < S-PF (−0.92 V) (Fig. 7a). This trend aligns with the LUMO energy levels predicted by DFT calculations shown in Fig. 6, further validating the agreement between experimental and computational results.

Unlike reduction processes, oxidation of flavins has received less attention, likely because the isoalloxazine ring is already in its fully oxidized form, analogous to a quinone core. In this work, however, the oxidation is of particular interest due to the significant alterations in the HOMO (Fig. 6). Remarkably, O-PF and S-PF display unusual quasi-reversible oxidation (Fig. 7b). This quasi-reversibility is exclusive to the heteroatom-incorporated pentacyclic flavins (e.g., O-PF and S-PF), as N-Ph, N-Ph(OMe), and C-PF revealed irreversible oxidation (Fig. 7b). The oxidative feature could arise from the formation of stabilized radical cation species, likely due to additional resonance effects within the fused phenoxazine or phenothiazine moieties. Overall, the anodic peak potential (Ep,a) increased in the following order: S-PF (1.12 V) < O-PF (1.26 V) < N-Ph(OMe) (1.40 V) < C-PF (1.46 V) < N-Ph (1.71 V) (Fig. 7b). This trend aligns with the HOMO energy levels predicted by DFT calculations (Fig. 6).

These findings provide a strategy for fine-tuning the electronic structure and thus oxidative properties of flavins. Specifically, the developed pentacyclic platform enables selective localization of the HOMO on either phenoxazine or phenothiazine, while preserving the flavin’s characteristic LUMO centered on the isoalloxazine ring. Thus, we believe that this pentacyclic flavin system has the potential to broaden the scope of flavin-mediated redox transformations, and further investigations are ongoing.

In this study, we successfully designed and synthesized a class of flavin-based chromophores, including C-PF, O-PF, and S-PF, to explore how structural modifications and the incorporation of heteroatoms influence their optical and electrochemical properties. Our results demonstrate that altering the nature of the linker unit (X) within the pentacyclic scaffold significantly impacts the π-conjugation, electronic distribution, and redox behavior of these flavins. The developed pentacyclic flavins, O-PF and S-PF, in particular, stand out for their deep-red and NIR emissions, respectively, which arise from a combination of the extended π-space, substituent effects, and enhanced charge separation upon excitation. In addition, the quasi-reversible oxidative feature of O-PF and S-PF demonstrates the potential and capability of this pentacyclic platform to fine-tune the frontier molecular orbitals. These findings not only expand the chemical space of synthetic flavins, marking the examples of deep-red and NIR emissive flavin families, but also open opportunities for their potential applications in bioimaging, photocatalysis, and optoelectronic devices, where tunable redox properties and long-wavelength emission are highly desirable.

Methods

Synthetic procedures and compound characterization

All compounds were synthesized using standard Schlenk or drybox techniques under a nitrogen atmosphere, unless otherwise noted. Detailed synthetic procedures, including reaction conditions, yields, NMR spectra, high-resolution mass spectrometry, and X-ray crystallographic data, are provided in the Supplementary Information.

Photophysical measurements

UV/Vis/NIR absorption spectra were recorded using a Shimadzu UV-2600i spectrophotometer. Emission spectra were obtained with a Shimadzu RF-6000 fluorometer using quartz cuvettes (1 cm path length).

Electrochemical analysis

Cyclic voltammetry was conducted on a Biologics SP-50e potentiostat using a three-electrode setup (glassy carbon working electrode, platinum counter electrode, and Ag/Ag⁺ reference electrode) in anhydrous acetonitrile with tetrabutylammonium hexafluorophosphate (0.1 M) as the supporting electrolyte.

Computational details

Geometry optimizations and excited-state calculations were performed using DFT and TD-DFT at the B3LYP-D3(BJ)/Def2-TZVP//Def2-SVP level with SMD solvation model for DMSO. Natural transition orbital (NTO) analyses were used to compute the hole-electron separation distance. Full computational details are provided in the Supplementary Information.

Data availability

All data is available in the main text or the supplementary information. All data are available upon request. Source data are provided with this paper. Supplementary Information and chemical compound information are available in the online version of the paper. Crystallographic data of N-Ph (CCDC 2400632), N-Ph(OMe) (CCDC 2400633), O-PF (CCDC 2400634), S-PF (CCDC 2400635), and C-PF (CCDC 2400636) are available free of charge from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre. Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.” Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Lienhart, W.-D., Gudipati, V. & Macheroux, P. The human flavoproteome. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 535, 150–162 (2013).

Bonomi, F. & Iametti, S. in Flavins and Flavoproteins: Methods and Protocols (ed Maria Barile) 119-133 (Springer, 2021).

König, B., Kümmel, S., Svobodová, E. & Cibulka, R. Flavin photocatalysis. Phys. Sci. Rev. 3, 20170168 (2018).

Pavlovska, T. & Cibulka, R. Structure and properties of flavins. In Flavin‐Based Catalysis (ed. Cibulka, R.) 1–27 (Wiley-VCH, 2021).

Breinlinger, E., Niemz, A. & Rotello, V. M. Model systems for flavoenzyme activity. Stabilization of the flavin radical anion through specific hydrogen bond interactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 117, 5379–5380 (1995).

Tan, S. L. J. & Webster, R. D. Electrochemically induced chemically reversible proton-coupled electron transfer reactions of riboflavin (Vitamin B2). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 5954–5964 (2012).

McBride, R. A., Barnard, D. T., Jacoby-Morris, K., Harun-Or-Rashid, M. & Stanley, R. J. Reduced flavin in aqueous solution is nonfluorescent. Biochemistry 62, 759–769 (2023).

Crosson, S. & Moffat, K. Structure of a flavin-binding plant photoreceptor domain: Insights into light-mediated signal transduction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 98, 2995–3000 (2001).

Conrad, K. S., Manahan, C. C. & Crane, B. R. Photochemistry of flavoprotein light sensors. Nat. Chem. Biol. 10, 801–809 (2014).

Arakawa, Y., Minagawa, K. & Imada, Y. Advanced flavin catalysts elaborated with polymers. Polym. J. 50, 941–949 (2018).

Iida, H., Imada, Y. & Murahashi, S. I. Biomimetic flavin-catalysed reactions for organic synthesis. Org. Biomol. Chem. 13, 7599–7613 (2015).

Imada, Y., Iida, H. & Naota, T. Flavin-catalyzed generation of diimide: an environmentally friendly method for the aerobic hydrogenation of olefins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 14544–14545 (2005).

März, M., Babor, M. & Cibulka, R. Flavin catalysis employing an N(5)-Adduct: an application in the aerobic organocatalytic mitsunobu reaction. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 3264–3268 (2019).

Srivastava, V., Singh, P. K., Srivastava, A. & Singh, P. P. Synthetic applications of flavin photocatalysis: a review. RSC Adv. 11, 14251–14259 (2021).

Lechner, R., Kümmel, S. & König, B. Visible light flavin photo-oxidation of methylbenzenes, styrenes and phenylacetic acids. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 9, 1367–1377 (2010).

Foja, R. et al. Reduced Molecular Flavins as Single-Electron Reductants after Photoexcitation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 4721–4726 (2022).

Walter, A. & Storch, G. Synthetic C6-functionalized aminoflavin catalysts enable aerobic bromination of oxidation-prone substrates. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 22505–22509 (2020).

Hartman, T. et al. Photocatalytic oxidative [2+2] cycloelimination reactions with flavinium salts: mechanistic study and influence of the catalyst structure. ChemPlusChem 86, 373–386 (2021).

Zelenka, J. et al. Combining flavin photocatalysis and organocatalysis: metal-free aerobic oxidation of unactivated benzylic substrates. Org. Lett. 21, 114–119 (2019).

Dad’ová, J., Svobodová, E., Sikorski, M., König, B. & Cibulka, R. Photooxidation of sulfides to sulfoxides mediated by tetra-O-acetylriboflavin and visible light. ChemCatChem 4, 620–623 (2012).

Hering, T., Mühldorf, B., Wolf, R. & König, B. Halogenase-inspired oxidative chlorination using flavin photocatalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 5342–5345 (2016).

Ramirez, N. P., König, B. & Gonzalez-Gomez, J. C. Decarboxylative cyanation of aliphatic carboxylic acids via visible-light flavin photocatalysis. Org. Lett. 21, 1368–1373 (2019).

Bailleul, G. et al. Evolution of enzyme functionality in the flavin-containing monooxygenases. Nat. Commun. 14, 1042 (2023).

Edwards, A. M. in Flavins Photochemistry and Photobiology Vol. 6 (eds Iqbal Ahmad et al.) (The Royal Society of Chemistry, 2006).

Mansoorabadi, S. O., Thibodeaux, C. J. & Liu, H.-W. The diverse roles of flavin CoenzymesNature’s most versatile Thespians. J. Org. Chem. 72, 6329–6342 (2007).

Fraaije, M. W. & Mattevi, A. Flavoenzymes: diverse catalysts with recurrent features. Trends Biochem. Sci. 25, 126–132 (2000).

Zeng, Q.-Q. et al. Biocatalytic desymmetrization for synthesis of chiral enones using flavoenzymes. Nat. Synth. 3, 1340–1348 (2024).

Orita, A., Verde, M. G., Sakai, M. & Meng, Y. S. A biomimetic redox flow battery based on flavin mononucleotide. Nat. Commun. 7, 13230 (2016).

Lei, J. et al. An active and durable molecular catalyst for aqueous polysulfide-based redox flow batteries. Nat. Energy 8, 1355–1364 (2023).

Nambafu, G. S. et al. An organic bifunctional redox active material for symmetric aqueous redox flow battery. Nano Energy 89, 106422 (2021).

Lee, M. et al. Redox cofactor from biological energy transduction as molecularly tunable energy-storage compound. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 8322–8328 (2013).

Lin, K. et al. A redox-flow battery with an alloxazine-based organic electrolyte. Nat. Energy 1, 16102 (2016).

Rehpenn, A., Walter, A. & Storch, G. Molecular editing of flavins for catalysis. Synthesis 53, 2583–2593 (2021).

Čubiňák, M. et al. Tuning the photophysical properties of flavins by attaching an aryl moiety via direct C–C bond coupling. J. Org. Chem. 88, 218–229 (2023).

Fukuzumi, S., Kuroda, S. & Tanaka, T. Flavin analog-metal ion complexes acting as efficient photocatalysts in the oxidation of p-methylbenzyl alcohol by oxygen under irradiation with visible light. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 107, 3020–3027 (1985).

Fukuzumi, S. et al. Efficient catalysis of rare-earth metal ions in photoinduced electron-transfer oxidation of benzyl alcohols by a flavin analogue. J. Phys. Chem. A 105, 10501–10510 (2001).

Varnes, A. W., Dodson, R. B. & Wehry, E. L. Interactions of transition-metal ions with photoexcited states of flavines. Fluorescence quenching studies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 94, 946–950 (1972).

Mühldorf, B. & Wolf, R. Photocatalytic benzylic C–H bond oxidation with a flavin scandium complex. Chem. Commun. 51, 8425–8428 (2015).

Li, W.-S., Zhang, N. & Sayre, L. M. N1,N10-Ethylene-bridged high-potential flavins: synthesis, characterization, and reactivity. Tetrahedron 57, 4507–4522 (2001).

Obertík, R. et al. Highly chemoselective catalytic photooxidations by using solvent as a sacrificial electron acceptor. Chem. Eur. J. 28, e202202487 (2022).

Pokluda, A. et al. Robust photocatalytic method using ethylene-bridged flavinium salts for the aerobic oxidation of unactivated benzylic substrates. Adv. Synth. Catal. 363, 4371–4379 (2021).

Ishikawa, T., Kimura, M., Kumoi, T. & Iida, H. Coupled flavin-iodine redox organocatalysts: aerobic oxidative transformation from N-tosylhydrazones to 1,2,3-thiadiazoles. ACS Catal. 7, 4986–4989 (2017).

Iida, H., Ishikawa, T., Nomura, K. & Murahashi, S.-I. Anion effect of 5-ethylisoalloxazinium salts on flavin-catalyzed oxidations with H2O2. Tetrahedron Lett. 57, 4488–4491 (2016).

Hasford, J. J. & Rizzo, C. J. Linear free energy substituent effect on flavin redox chemistry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 120, 2251–2255 (1998).

Bosca, F., Fernandez, L., Heelis, P. F. & Yano, Y. Substituent effects on electrophilicity of flavins: an experimental and semi-empirical molecular orbital study. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 55, 183–187 (2000).

Kormányos, A. et al. Flavin derivatives with tailored redox properties: synthesis, characterization, and electrochemical behavior. Chem. Eur. J. 22, 9209–9217 (2016).

Mojr, V. et al. Tailoring flavins for visible light photocatalysis: organocatalytic [2+2] cycloadditions mediated by a flavin derivative and visible light. Chem. Commun. 51, 12036–12039 (2015).

Mohammed, N. et al. Synthesis and characterisation of push–pull flavin dyes with efficient second harmonic generation (SHG) properties. RSC Adv. 7, 24462–24469 (2017).

Zubova, E., Pokluda, A., Dvořáková, H., Krupička, M. & Cibulka, R. Exploring the reactivity of flavins with nucleophiles using a theoretical and experimental approach. ChemPlusChem 89, e202300547 (2024).

Graml, A., Neveselý, T., Jan Kutta, R., Cibulka, R. & König, B. Deazaflavin reductive photocatalysis involves excited semiquinone radicals. Nat. Commun. 11, 3174 (2020).

Marian, C. M., Nakagawa, S., Rai-Constapel, V., Karasulu, B. & Thiel, W. Photophysics of flavin derivatives absorbing in the blue-green region: thioflavins as potential cofactors of photoswitches. J. Phys. Chem. B 118, 1743–1753 (2014).

Rehpenn, A., Hindelang, S., Truong, K.-N., Pöthig, A. & Storch, G. Enhancing flavins photochemical activity in hydrogen atom abstraction and triplet sensitization through ring-contraction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202318590 (2024).

Mataranga-Popa, L. N. et al. Synthesis and electronic properties of π-extended flavins. Org. Biomol. Chem. 13, 10198–10204 (2015).

Corbin, D. A. et al. Effects of the chalcogenide identity in N-aryl phenochalcogenazine photoredox catalysts. ChemCatChem 14, e202200485 (2022).

Reichardt, C. Empirical parameters of solvent polarity as linear free-energy relationships. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 18, 98–110 (1979).

Parr, R. G. & Yang, W. Density-Functional Theory of Atoms and Molecules (Oxford Univ. Press, New York, 1989).

Becke, A. D. Density-functional exchange-energy approximation with correct asymptotic behavior. Phys. Rev. A 38, 3098–3100 (1988).

Grimme, S., Antony, J., Ehrlich, S. & Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 132, 154104 (2010).

Lee, C., Yang, W. & Parr, R. G. Development of the Colle-Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys. Rev. B 37, 785–789 (1988).

Slater, J. C. & Phillips, J. C. Quantum theory of molecules and solids vol. 4: the self‐consistent field for molecules and solids. Phys. Today 27, 49–50 (1974).

Grimme, S., Ehrlich, S. & Goerigk, L. Effect of the damping function in dispersion corrected density functional theory. J. Comput. Chem. 32, 1456–1465 (2011).

Weigend, F. & Ahlrichs, R. Balanced basis sets of split valence, triple zeta valence and quadruple zeta valence quality for H to Rn: Design and assessment of accuracy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 7, 3297–3305 (2005).

Martin, R. L. Natural transition orbitals. J. Chem. Phys. 118, 4775–4777 (2003).

Plasser, F., Wormit, M. & Dreuw, A. New tools for the systematic analysis and visualization of electronic excitations. I. Formalism. J. Chem. Phys. 141, 024106 (2014).

Plasser, F. & Lischka, H. Analysis of excitonic and charge transfer interactions from quantum chemical calculations. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 8, 2777–2789 (2012).

Tan, S. L. J., Novianti, M. L. & Webster, R. D. Effects of low to intermediate water concentrations on proton-coupled electron transfer (PCET) reactions of flavins in aprotic solvents and a comparison with the PCET reactions of quinones. J. Phys. Chem. B 119, 14053–14064 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation (NRF) of Korea through grants RS-2023-00213092 and NRF-2019R1A6A1A1007388723, funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT and the Ministry of Education, respectively. Additional support was provided by the Saudi Aramco and KAIST CO2 Management Center (G01240501) and the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy (RCMS-00469042) in the Republic of Korea. The authors thank Mr. Seung Uk Shin and Dr. Hee Won Seo at KARA, KAIST, for their assistance in measuring the emission spectra of the compounds. We also thank Prof. Dongwhan Lee and his student Mr. Younghun Kim at SNU, Korea, for sharing valuable tips on photographing emissive materials. Lastly, we express our gratitude to Prof. Sukbok Chang for generously allowing us to use the single-crystal X-ray diffractometer and to Prof. Mu-Hyun Baik for providing the research computing resources for the DFT calculations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.S. and Y.B. conceived the project and designed the initial experiments. D.S., G.Y., and T.S. performed experiments regarding the synthesis and characterization of the flavin compounds. S.K., C.W., and D.S. performed computational analysis. D.K. performed single-crystal X-ray diffraction analysis. N.S. provided an idea for designing the pentacyclic scaffold. All authors analyzed the data, discussed the results, and commented on the manuscript. S.K., G.Y., and T.S. contributed equally to this work. Y.B. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Seo, D., Kwon, S., Yoon, G. et al. Expanding the chemical space of flavins with pentacyclic architecture. Nat Commun 16, 3561 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-58957-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-58957-2