Abstract

The discovery of ferroelectricity in hafnium dioxide (HfO2) thin films over the past decade has revolutionized the landscape of ferroelectrics, providing a promising candidate for next-generation ferroelectrics beyond the constraints of Moore’s law. However, the underlying formation mechanism of their metastable and volatile ferroelectric phase is under debate. Herein, we successfully grow HfO2-based (Lu:Hf1−xZrxO2) bulk crystals and gain a comprehensive understanding of the non-polar to ferroelectric phase evolution. We achieve a controllable polymorphic engineering by elucidating the synergistic modulation of co-doped Lu3+ and Zr4+ ions. Our investigation unveils the intricate local structural transitions involved in the formation of the ferroelectric orthorhombic Pbc21 phase from the metastable tetragonal phase. We also establish a controllable tetragonal-to-orthorhombic transformation route, effectively improving the ferroelectric phase component within bulk crystals. Our findings will advance the comprehension of ferroelectric mechanisms in fluorite-structured materials, paving the way for significant strides in developing HfO2-based nonvolatile electronic and photonic devices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With scientific and technological advances, ferroelectric materials exhibiting excellent compatibility with the complementary metal-oxide semiconductor (CMOS) process have become the foundation of optoelectronic functional devices capable of integration and miniaturization1,2,3. Over the years, there has been a mounting interest in HfO2-based fluorite-structure ferroelectric materials. Of particular interest is that their switchable ferroelectric polarization capabilities endure, even when the film thickness is reduced to the atomic realm, typically ranging from 0.5 to 1 nm4,5. Consequently, HfO2-based ferroelectric materials have emerged as a class of promising candidates for the development of highly compact microelectronic devices, encompassing nonvolatile information memory and field-effect transistors, ushering in a new era beyond Moore’s law6,7,8.

Regarding HfO2 and its analog ZrO2, the temperature-dependent polymorphs manifest as cubic (c, Fm-3m), tetragonal (t, P42/nmc), and monoclinic (m, P21/c) phases, while the pressure-induced polymorphs include orthorhombic-I (o-AFE, Pbca) and orthorhombic-II (Pnma)9,10. It is worth noting that none of these space groups can sustain any ferroelectric polarization due to their centrosymmetric (non-polar) nature. The intrinsic ferroelectric origin of HfO2-based materials has remained a mystery ever since its first discovery in an Si:HfO2 thin film11. Several polar ferroelectric space groups have been proposed based on extensive theoretical and experimental studies, including the orthorhombic (Pbc21 and Pmn21) and rhombohedral (R3m) phases12,13,14.

The formation mechanism of HfO2-based ferroelectric phases has always been disputable since the discovery of their ferroelectricity. Early research into HfO2-based ferroelectrics was largely confined to thin films, in which the primary stabilizing factor for ferroelectric phases was often attributed to the phase transformation originating from the metastable t phase6,15,16. Regarding HfO2-based bulk crystals, the observed ferroelectricity is believed to be achieved through the Curie phase transition from the high-temperature c phase17. For colloidal HfO2 nanocrystals, the m phase at the twinning boundary can evolve into the polarization phase, even in the absence of symmetry breaking18,19. Additionally, flat polar phonon bands are considered to be a contributing factor to ferroelectric switching in HfO220, while a moderate electrical stimulus can induce a transformation from the antipolar o-AFE phase to the polar o-FE (Pbc21) phase21. These different formation mechanisms of HfO2-based ferroelectric phases make it essential to understand the non-polar to ferroelectric phase evolution process3. On account of the small grain size (<20 nm) and multiphase interference within actively studied HfO2-based films6,15, discerning the phase evolution of HfO2-based ferroelectricity remains challenging. Most HfO2-based studies primarily focus on analyzing the evolution trajectory of the ferroelectric phase based on a variety of theoretical simulations20,22. Additionally, HfO2-based switchable spontaneous polarization mainly arises from the movement of oxygen ions, rather than cation displacement as observed in perovskite systems6. To comprehensively understand the non-polar to ferroelectric phase evolution in HfO2-based materials, it is imperative to clarify the motion trajectories of oxygen atoms. However, the challenge lies in directly observing oxygen, which has a small atomic number, complicating the atomic-scale characterization15. The emergence of HfO2-based bulk ferroelectric crystals provides an alternative platform for exploring the formation mechanism of HfO2-based ferroelectricity, owing to their grain size of hundreds of nanometers17, which are significantly larger than those in nanoscale thin films.

In this work, we provide compelling evidence of non-polar to ferroelectric phase evolution in HfO2-based (Lu:Hf1−xZrxO2) bulk crystals. Our investigation highlights the pivotal roles of Lu3+ and Zr4+ ions in the adjustment of polymorphic phases. Through the microstructural analyses by integrated differential phase-contrast scanning transmission electron microscopy (iDPC-STEM), we successfully identify the polymorphic phases present in Lu:Hf1−xZrxO2 bulk crystals, including the o-FE, o-AFE, and t phases. Building upon this foundation, we further reveal the t-o phase evolution process by directly observing the movement trajectory of Hf and O atoms near the phase boundary. Finally, we establish a controllable t-to-o transformation mechanism and propose a feasible strategy for optimizing the o-FE phase component within the Lu:Hf1−xZrxO2 bulk crystals. These findings provide a clear understanding of the formation mechanism behind the o-FE polar phase and pave the way for the development of bulk-state fluorite-structure ferroelectric crystals.

Results

Crystal growth and structural survey of Lu:Hf1−xZrxO2 bulk crystals

Leveraging rare-earth-doped HfO2 (RE:HfO2) has emerged as a feasible strategy to stabilize the relevant metastable polymorphs, such as c, t, o-FE, and o-AFE17,23,24. To prevent the formation of the m phase within RE:HfO2 bulk crystals, it is important to meticulously consider the eutectoid reaction (occurring at ~1780 °C, t → c + m), especially when dealing with nearly pure HfO2 (Fig. 1a)23. The optical floating zone (OFZ) method is a versatile approach to grow high-temperature metastable crystals, as it produces a large temperature gradient due to the absence of temperature-field protection25. We grew the RE:HfO2 bulk crystals using the OFZ method, and the as-grown crystals were cooled to room temperature by slow quenching (in ~5.5 h). For the structural analysis, the standard cards for the c, t, and o-AFE phases are obtained from ICSD Nos. 173967, 173966, and 79913, respectively, while the standard card for the o-FE phase is from ref. 26. The theoretical Raman vibrational modes for the c, t, o-AFE, and o-FE phases are sourced from ref. 27. As shown in Supplementary Figs. 1–5, the X-ray diffraction (XRD) and Raman data for both the as-grown Gd:HfO2 and Lu:HfO2 crystals highlight the importance of adhering to this selection rule that avoids the emergence of eutectoid reaction by adjusting the RE doping concentration. The phase evolution of RE:HfO2 can be controlled by managing the oxygen vacancies that arise from the heterovalent substitution of rare-earth ions (acceptor dopant). Previous studies on RE:HfO2 (RE = La, Gd, Y, Sc) have indicated that the optimal stabilization range of the o-FE phase typically falls below 10 at.% of RE doping28,29,30. The selection of RE ions in preparing RE:HfO2 bulk ferroelectric crystals must consider both the optimal doping concentration to maintain robust ferroelectricity and the minimum doping concentration to avoid the eutectoid reaction. Thus, we selected Lu:HfO2 crystals to investigate relevant polymorphic transformations due to the concentration advantage in avoiding the eutectoid reactions (Supplementary Table 1). As shown in Supplementary Fig. 2a, the obtained XRD data for Lu:HfO2 crystals (10–11 at.%) suggest the existence of orthorhombic phases. Subsequent Raman spectroscopy reveals that the primary phase in the as-grown Lu:HfO2 crystals (10–11 at.%) is the o-AFE phase rather than the o-FE phase (Supplementary Fig. 5a)27.

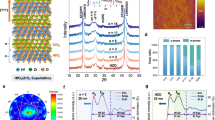

a Schematic diagram of the eutectoid reaction existing in the temperature-dependent phase diagram of Lu doped HfO2. The symbols of m, c, and t correspond to the monoclinic, cubic, and tetragonal phases, respectively. b Photograph of the as-grown Lu:Hf0.6Zr0.4O2 (9.25 at.%) crystal with a dimension of φ3 × 60 mm3. c Room-temperature XRD data of the Lu:Hf0.6Zr0.4O2 crystals with different Lu doping concentrations. The light blue shaded regions (at 38.7°, 53.5°, and 55.7°) represent the diffraction peaks observed in the o phase that are not present in the t phase. d Room-temperature Raman spectra of the Lu:Hf0.6Zr0.4O2 crystals. The shaded regions correspond to the characteristic peaks of t (273 cm−1) and o-AFE (367 cm−1) phases, respectively. e Intensity ratio (I273/I367) between the Raman peaks at 273 cm−1 (for the t phase) and 367 cm−1 (for the o-AFE phase) for different Lu:Hf0.6Zr0.4O2 crystals.

In addition to the incorporation of RE3+ ions, the introduction of Zr4+ ions stands out as a feasible phase control method in high-temperature Hf1−xZrxO2 metastable polymorphs. The ferroelectric phase can be maintained within a specific range of Zr doping, typically falling between 35 and 50 at.%31,32,33. Thus, we grew Lu:Hf1−xZrxO2 crystals by the OFZ slow quenching strategy. To begin, we held the Lu doping concentration constant at 9 at.% while adjusting the Zr doping concentration at 5 at.% increments. As shown in Supplementary Figs. 6 and 7, high-quality Lu:Hf1−xZrxO2 crystals were successfully grown. The subsequent structural investigation confirmed the existence of orthorhombic phases (o-AFE or o-FE). Furthermore, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 8, we observe the vibrational modes of the t phase within the Lu:Hf1−xZrxO2 crystals, in addition to the distinct scattering response of the o-AFE phase.

In general, the orthorhombic o-AFE phase or o-FE phases emerge as a result of the temperature-driven phase transition from the high-temperature t or c phase. According to their respective formation energies, these polymorphs rank in the descending order of c, t, o-FE, and o-AFE, with the o-AFE phase being the most energetically favorable17,27. The Raman vibrations shown in Supplementary Fig. 8 imply that the introduction of Zr4+ ions can stabilize the metastable t and o-AFE phases within the Lu:Hf1−xZrxO2 bulk crystals simultaneously. It is worth noting that the presence of the o-FE phase is also reasonable in the bulk crystals because its formation energy is between those of the t and o-AFE phases. The second harmonic generation (SHG) characterization further corroborates the presence of a polar phase within the as-grown bulk crystals (Supplementary Fig. 9).

The crystal doped with 40 at.% Zr exhibited superior machining characteristics, demonstrating a greater resilience to cracking than the other three Lu:Hf1−xZrxO2 crystals (Supplementary Fig. 6a). Building upon this observation, we prepared a series of Lu:Hf0.6Zr0.4O2 crystals with varying Lu doping concentrations, and Fig. 1b exhibits the typical as-grown bulk crystal with a Lu doping concentration of 9.25 at.%. As shown in Fig. 1c, with an increase in the Lu doping level, the diffraction intensities at 38.7°, 53.5°, and 55.7° gradually diminish in comparison to the dominant Bragg peak at 30°. This trend suggests a growing prevalence of the t-phase component in the final crystal structure. The Raman spectroscopy results (Fig. 1d, e) align with the structural characterization, revealing that the sample doped with 10.5 at.% Lu is mainly characterized by t-phase vibrational modes. This phenomenon coincides with the phase modulation behavior of RE3+ ions observed in RE:HfO2 crystals, where RE doping concentrations exceeding 10 at.% tend to stabilize the metastable t phase, despite its higher formation energy24.

Next, we conducted temperature-dependent XRD analyses on the Lu:Hf0.6Zr0.4O2 (9.25 at.% and 10 at.%) and Lu:HfO2 (10 at.%) crystals to study the polymorphism transformation between different metastable phases as a function of temperature. As exhibited in Fig. 2a–c and Supplementary Fig. 10, a reversible phase transition is observed. Following the complete heating-cooling cycle, the crystal exhibits no discernible diffraction differences compared to its pristine state. The transformation temperatures of the Lu:HfO2 crystal are located in ranges of 900–1000 °C during heating and 800–900 °C during cooling, being comparable to Y:HfO2 bulk crystals (~800 °C)17. By contrast, the Lu:Hf0.6Zr0.4O2 crystals demonstrate much lower transformation temperatures, corresponding to 600–700 °C and 400–500 °C in the heating and cooling processes, respectively. The variation of Lu doping concentration has minimal effect on the phase-transition temperatures of Lu:Hf0.6Zr0.4O2 crystals. These phase-transition temperatures were further confirmed by the differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) measurement (Supplementary Fig. 11a). The transition temperatures of the Lu:Hf0.6Zr0.4O2 (9.25 at.%) are ~628 °C during heating and ~483 °C during cooling. Such a large thermal hysteresis (~145 °C) reflects a large barrier of the activation energy between the high- and low-temperature phases, implying a martensitic phase transition with an apparent volume change through the conversion process. As the temperature decreases across the transition temperature during cooling, the high-temperature phase gradually transforms into the o phases (o-FE or o-AFE) by overcoming the nucleation barrier. The phase transformation is governed by the combination of thermodynamic and kinetic driving forces (ΔG)6. With regard to the thermodynamic driving force, t to o-AFE is preferred compared to t to o-FE due to the more favorable free energy34. Concerning the kinetic driving force, on the other hand, the activation energy for the t to o-FE (46.0 meV per f.u.) is smaller than that for t to o-AFE (68.8 meV per f.u.), suggesting the formation of the o-FE phase requires a faster cooling rate in contrast to the o-AFE case6,17. Moreover, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 11b, the temperature-dependent dielectric constant (εr) of the Lu:Hf0.6Zr0.4O2 (9.25 at.%) bulk crystal exhibits an evident transition peak at the Curie temperature (~661 °C), which is consistent with the temperature-dependent structural and thermal results. For Lu:Hf0.6Zr0.4O2 bulk crystals, the transition from the low-temperature orthorhombic phase to the high-temperature polymorph is marked by the disappearance of Bragg diffraction peaks at ~53.7°, ~55.9°, ~65.8°, and ~67.9°. This signifies the complete transformation from the low-temperature phase to the high-temperature phase. Notably, the high-temperature phase possesses two distinct diffraction peaks around ~59.5° (or ~73.7°), suggesting that the high-temperature metastable polymorph was the t phase rather than the c phase16,35,36.

a Experimental data of the Lu:Hf0.6Zr0.4O2 (9.25 at.%) crystal over 30 to 1000 °C range. The color bar corresponds to the normalized diffraction intensity over the detected 2θ range (52°–57° and 65°–77°). b Detailed XRD data of the Lu:Hf0.6Zr0.4O2 (9.25 at.%) before and after the heating-cooling cycle. c Intensity ratio for the diffraction peaks around 53.5° (from the o phase) and 60° (from the o and t phases) calculated based on the temperature-dependent XRD data, for Lu:HfO2 (10 at.%) and Lu:Hf0.6Zr0.4O2 (9.25 at.% and 10 at.%) bulk crystals. d Manipulation of the phase transformation from the metastable t phase via introducing Zr4+ ions into Lu:Hf1-xZrxO2 bulk crystals. Tt-min denotes the minimum stabilization temperature of the t phase.

The above structural analyses highlight the polymorphic engineering within the Lu:Hf1–xZrxO2 bulk crystals, underscoring the synergistic contributions of co-doping Lu3+ and Zr4+ ions. The presence of RE3+ ions serves to address the challenges posed by the eutectoid reaction during the crystal growth. The XPS survey in Supplementary Fig. 12 confirms the presence of oxygen vacancies within the as-grown Lu:Hf1-xZrxO2 bulk crystals. As explained in Supplementary Note 1, we demonstrate the importance of oxygen vacancies in adjusting the phase evolution in Lu:HfO2 (5 and 10.5 at.%) and Ta,Lu:HfO2 (5–10.5 at.%) bulk crystals by comparing the modulation effect of Lu3+ and Ta5+ ions, which respectively generate and neutralize the oxygen vacancies. This result verifies that the phase evolution of RE:HfO2 bulk crystals is mainly associated with the oxygen vacancies originating from the heterovalent substitution6,15. The XRD data shown in Supplementary Figs. 7 and 13 further indicates the adjustment role of Lu3+ ions is also suitable for Lu:Hf1-xZrxO2 bulk crystals.

As shown in Fig. 2d, the solid lines, ranging from dark orange to blue, represent the transitions from the t phase under different cooling rates6. Under fixed OFZ growth conditions, the cooling path is verified. The primary phase in as-grown Lu:HfO2 crystals (10–11 at.%) is the o-AFE phase, implying the cooling process follows the path indicated by the orange solid line. The phase components within Lu:Hf1-xZrxO2 bulk crystals can be adjusted by changing the minimum stabilization temperature (Tt-min) of the t phase. To achieve this, we modulate the t-o phase transition temperature by introducing Zr4+ ions. The temperature-dependent XRD data in Fig. 2a–c validate the feasibility of this modulation strategy. As shown in Fig. 2d, under fixed OFZ growth conditions, the decline of Tt-min shifts the cooling path from the orange solid line to the orange dashed line. The subsequent structure analysis indicates the presence of t and o (o-FE or o-AFE) phases within Lu:Hf1-xZrxO2 bulk crystals, further highlighting the important role of Zr4+ ions in tuning the t-o transition temperature. This is akin to the modulation of the t-m transition temperature in Hf1–xZrxO26, benefiting the adjustment of the phase composition within the final bulk crystals. The coexistence of the metastable t and o phases within Lu:Hf1–xZrxO2 bulk crystals provides a versatile platform for understanding the t-o phase evolution process.

Local t-o transition process in Lu:Hf1−xZrxO2 bulk crystals

We employed STEM to examine the local atomic arrangement within the bulk Lu:Hf0.6Zr0.4O2 crystal. It is noteworthy that the HfO2-based ferroelectricity is intricately associated with the displacement of oxygen ions, in contrast to the more traditional perovskite ferroelectric materials, where the shift of cation plays a dominant role37,38. iDPC-STEM is an important microstructural imaging technique that enables atomic-scale resolution of both light and heavy elements39,40. To gain deeper insight into the transformation mechanism between various phases in the bulk crystal, we utilized the iDPC-STEM technique, owing to its heightened sensitivity to light elements, enabling a more comprehensive study of the phase transitions.

Figure 3a–c and Supplementary Fig. 14 exhibit the crystal structures of the o-AFE and t phases, as well as the o-FE polar phase. Specifically, the t phase possesses a single type of oxygen site, located at the center of the four neighboring cation positions. In contrast, both the o-FE and o-AFE phases contain dual oxygen sites (O1 and O2), exhibiting an off-center behavior. For o-FE and o-AFE, the O1 ions are located in the spacer layers (Layer II), and the O2 ions belong to the remaining polarization layers (Layers I and III, rectangular light blue areas). Notably, the o-FE and o-AFE phases exhibit a significant distribution difference of O2 ions within the ac plane. The polarization directions are parallel in o-FE (cyan arrows) and antiparallel in o-AFE (cyan and orange arrows). To delve further into the microstructure, iDPC-STEM was employed along the b-axis direction of the o-FE and o-AFE phases, a strategic choice for precise phase identification41,42. Figure 3d–f unveils critical insights into the material composition. Apart from the Hf/Zr/Lu cations, the image clearly highlights the presence of oxygen ions, being instrumental to phase identification at the atomic scale. This finding is in accordance with the aforementioned structural analyses discussed earlier, which confirms that the bulk crystal simultaneously possessed the t, o-FE, and o-AFE phases. In the o-FE phase, the O2 ions in different polarization layers exhibit a uniform c-axis displacement direction, thus yielding robust ferroelectric polarization. In contrast, the o-AFE phase, although possessing a similar cation distribution to that of the o-FE phase, exhibits a distinctive feature. The adjacent polarization layers exhibit reversed polarization directions, resulting in an antipolar nature. As shown in Fig. 3g, the o-FE and o-AFE phases coexist in certain regions owing to the low free energy gap between these two phases (~10 meV/f.u.)21. The coherent interface between o-AFE and o-FE phases within Lu:Hf1-xZrxO2 bulk crystals is characterized by the relationship (100)o-AFE‖(100)o-FE (bo-AFE // bo-FE & co-AFE // co-FE). This observation coincides with the atomic-resolution phase identification in ZrO2 and Hf0.5Zr0.5O2 ferroelectric films, revealing that the disparity between the o-FE and o-AFE polymorphs relies on the displacement direction of the oxygen ions within the polarization layers21,41. There is one polarization layer that exhibits a different displacement behavior of oxygen atoms compared to those within the o-FE or o-AFE phases, similar to the behavior observed in ZrO2 nanocrystals41. This phenomenon might be associated with the incomplete t-o phase transformation process, which could be caused by the large temperature gradient and fast growth rate during the OFZ growth process. Additionally, the different t-o phase evolution behaviors along the thickness direction may also give rise to the displacement discrepancy of oxygen atoms within polarization layers.

a–c Atomic arrangements of the o-FE, o-AFE, and t phases, respectively, derived from the standard cards of ref. 26, ICSD No. 79913, and ICSD No. 173966, respectively. The yellow, cyan, and orange spheres denote the Hf/Zr/Lu, O1, and O2 ions, respectively. For o-FE and o-AFE, the O1 ions are located in the spacer layers (Layer II), and the O2 ions belong to the remaining polarization layers (Layers I and III, rectangular light blue areas). d–f The observed atomic arrangements of o-FE, o-AFE, and t phases, with the associated black-white intensity color scales from −45911 to 65350, from −27498 to 38757, and from −45860 to 69494, respectively. a, d: along the [010] direction of o-FE. b, e: along the [010] direction of o-AFE. c, f: along the [001] direction of t. g The iDPC-STEM image contains the o-FE and o-AFE phases simultaneously (along the [010] direction), and the local zoom-in region well matches the polar o-FE and the antipolar o-AFE phases. The polarization directions are parallel in o-FE (cyan arrows) and antiparallel in o-AFE (cyan and orange arrows). The black-white intensity color scale is from −27615 to 40718. All the scale bars are 1 nm.

Furthermore, as shown in Fig. 4a, we observed the local multiphase region within the Lu:Hf0.6Zr0.4O2 bulk crystal, where the t, o-FE, and o-AFE phases coexisted. Notably, we identified distinct transitional phase regions between the t and o-FE or o-AFE phases, which differed from the steep t-o phase boundary observed in HfO2-based ferroelectric films21,41. The complete t-o phase transformation process contains two distinct stages, denoted as t’ and t”, corresponding to changes in the O and Hf sites, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 15). With Cluster 4 as an example, as illustrated in Fig. 4b, d1 and d2 represent the distances between the Hf sites within the polarization and spacer layers, respectively. d3 denotes the distance between the vertical Hf column and its corresponding O column on the right. The Hf sites of Cluster 4 show minimal position alteration, while the O sites within the polarization layers exhibit an evident atomic shift in the t’ stage, leading to a reduction in d3 compared to that of the t phase. In the adjacent t” stage, the primary change occurs within the neighboring horizontal Hf atomic layers, giving rise to an increase in d1 and a decrease in d2. The position change of the Hf atoms leads to a slight vertical displacement of the O atoms, but the horizontal mirror symmetry mh remains unbroken. This observation delineates the concrete atomic shift trajectory during the t-o phase transformation, contributing to a more comprehensive understanding of the formation mechanism of the o-FE phase. As demonstrated in Supplementary Fig. 16, this t-o phase evolution is a prevalent occurring phenomenon within the as-grown bulk crystal. Besides, the region with a small t-phase component, located between the o-phase regions, exhibits a different t-o evolution behavior on its left and right sides (Supplementary Fig. 17). The o-phase polarization layer on the left corresponds to the o-phase spacer layer on the right side, and vice versa. This phenomenon is associated with the difference in the t-o phase transformation within the t-phase region. The high structural symmetry of the t phase along the c-axis makes the Hf-Hf distances along the [110] (or [−110]) direction lack the polarization and spacer layer characteristics observed in the o-phase. During the t-o phase transformation within the OFZ growth process, the t-phase region may display different phase transition behaviors on its left and right sides. The t-phase Hf-Hf layer likely corresponds to the polarization and spacer layers associated with the t-o phase evolution on either side. As the t-phase region is gradually consumed, the sample ultimately exhibits the t-o transformation phenomenon shown in Supplementary Fig. 17. According to the phase evolution shown in Fig. 4c, the movement of O atoms in the t’ stage breaks the centrosymmetric operation and transforms the space group from tetragonal non-polar P42/nmc to orthorhombic polar crystal systems. The horizontal shift of O sites primarily occurs in the t’ stage, while the change in the vertical Hf-Hf column is concentrated in the t” stage. The t-o phase transition breaks the four-fold rotation symmetry along the [001] direction of the t phase but retains the mirror operation that is parallel to the (100) plane of the o phases. Through the t-o transition, the shift of the O sites (d3) reaches the maximum distance and yields robust intrinsic polarization in the o-FE phase, which can be directly observed by comparing the change of horizontal polarization vectors within each polarization layer (Fig. 4a, detailed calculation description in Supplementary Fig. 18). In each polarization layer, the arrow direction and the arrow length denote the polarization direction and polarization magnitude of each horizontal polarization vector, respectively. Clusters 1–8 present a distinct t-o phase evolution process by virtue of the change of d1, d2, and d3. Besides, the polarization layers of the clusters close to the t-phase region do not exhibit an apparent polarization magnitude, even if in the o-phase region.

a iDPC-STEM results that illustrate the transformation from the initial t (brown) phase to the transient t’ (pink) and t” (yellow), and the formation of o-FE (green) and o-AFE (blue) phases. In each polarization layer, the arrow direction and the arrow length denote the polarization direction and polarization magnitude of each horizontal polarization vector, respectively. The black-white intensity color scale is from −55204 to 78162. b Taking Cluster 4 as an example, the ion distances d1, d2, and d3 across different phase regions are displayed. c Phase evolution mechanism from the t to o-FE phases. The orange arrows denote the movements of the Hf or O ions. d1 and d2 represent the vertical Hf-Hf distances, and d3 corresponds to the horizontal distance between the vertical Hf column and its corresponding O column on the right. mh denotes the horizontal mirror symmetry. The horizontal cyan arrows with a capital P represent the polarization direction. d Hf-Hf distance (d1 and d2) of iDPC-STEM image shown in (a), including the t-o phase evolution region.

Figure 4d describes an apparent alteration of Hf-Hf bond distances throughout the t-o phase evolution process. In the o-FE phase, the values of d1 and d2 remain relatively stable at ~270 pm and ~240 pm, respectively. The notable difference in bond distances between the o-FE and t phases (d1 = d2 = ~259 pm) implies that the bulk crystal experienced strain alteration during the t-o transition. To further assess the strain distributions within Lu:Hf1−xZrxO2 bulk crystals, we conducted a thorough analysis using geometric phase analysis (GPA)43,44,45. Supplementary Fig. 19 and Supplementary Note 2 show that the normal strain variation within the t-phase and t-o transition regions presents a random distribution. This randomness mainly originates from the stabilization strategy employed in the OFZ crystal growth method, where the large temperature gradient and fast growth rate hinder ion diffusion, giving rise to strong chemical pressure at the local regions due to ion substitution17. Additionally, the t-phase region near the t-o phase evolution region presents a slight tensile shear strain, coinciding with the martensitic transformation characteristic of the t-o conversion process6. In contrast, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 20, the strain fluctuation at the phase boundary between the o-FE and o-AFE phases is minimal because of the similar lattice parameters (Pbca, a = 5.01 Å, b = 5.27 Å, c = 5.06 Å) and (Pbc21, a = 5.01 Å, b = 5.29 Å, c = 5.08 Å)14, a phenomenon akin to the strain change observed in ZrO2 nanocrystals41.

Optimization of o-FE phase in Lu:Hf1−xZrxO2 bulk crystals

We performed a Rietveld refinement analysis on the room-temperature XRD data of slow-quenched Lu:Hf1−xZrxO2 bulk crystals to determine the associated phase components (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Figs. 21 and 22). The t phase is predominant in all the as-grown crystals. Among the two o phases within the bulk crystals, the o-AFE phase is more likely to exist than the o-FE phase, coinciding with the observation from the Raman spectra (Fig. 1d, e). The optimization of o-FE phase within the Lu:Hf1−xZrxO2 bulk crystals requires meticulous consideration of the t-o phase transformation mechanism3,6. Although the ideal analytical model assumes a pure t phase, achieving t-phase bulk crystals remains a significant challenge.

a Phase proportion within Lu:Hf0.6Zr0.4O2 (9–10.5 at.%) bulk crystals through slow quenching. b Room-temperature XRD data for the Lu:Hf0.6Zr0.4O2 (10 at.%) crystal by fast quenching. The inset is the crystal photograph. c Room-temperature Raman spectra of the as-grown and annealed (1000 °C for 10 h in air) fast-quenched Lu:Hf0.6Zr0.4O2 (10 at.%) crystal samples. The shaded region corresponds to the characteristic peaks of the o-FE phase. d, e Nonpolarized and polarized (the incident and detected polarizations are vertical) images of the fast-quenched Lu:Hf0.6Zr0.4O2 (10 at.%) crystal sample. All the scale bars are 2 μm. f Dependence of quenching rate on the phase component of Lu:Hf0.6Zr0.4O2 (10 at.%) bulk crystals. g Influence mechanism of quenching rate on the phase transformation from the metastable t phase within Lu:Hf0.6Zr0.4O2 (10 at.%) bulk crystals. Eh denotes the heating energy, and ΔEt/o-FE (or ΔEt/o-AFE) represents the energy barrier between the t and o-FE (or o-AFE) phases.

We selected Lu:Hf0.6Zr0.4O2 (10 at.%) as the designed chemical composition because it closely approximates the pure t phase compared to other low Lu doping levels. Regarding the crystal growth process, fast quenching proved to be an effective strategy for stabilizing the HfO2-based metastable polymorphs at room temperature17,24. Provided the cooling rate is sufficiently rapid, the t-phase bulk crystal could potentially be directly achieved. Thus, we removed the as-grown bulk crystal from the heating zone within 2 s, yielding a rapid temperature variation exceeding 1000 °C/s. As Fig. 5b shows, the Lu:Hf0.6Zr0.4O2 (10 at.%) bulk crystal does not crack through such a rapid quenching process. Only t-phase signals are observed from the XRD and Raman data of the as-grown bulk crystal (Fig. 5b, c, Supplementary Fig. 23a), implying that the o-phase interference is successfully eliminated. The subsequent polarized optical characterization strengthens the presence of the t phase, as evidenced by the clear contrast comparison (Fig. 5d, e), ruling out the presence of the c phase.

In the context of the t-o phase transformation process, both o-FE and o-AFE phases can form within the bulk crystals due to their similar free energies21. Considering the energy barrier differences of the t → o-FE and t → o-AFE transformation processes17, we investigated the annealing temperature influence on the final phase component of the fast-quenched Lu:Hf0.6Zr0.4O2 (10 at.%) bulk crystal samples and proposed a schematic diagram illustrating the kinetics of the t-to-o phase transformation. Once the annealing temperature reaches the threshold for the t-to-o phase transformation, the o phase rapidly forms by relieving the chemical pressure within the as-grown bulk crystal. As shown in Fig. 5f, g and Supplementary Fig. 24, annealing at 900 °C hardly induces any t-to-o phase transformation, revealing the heating energy (Eh) < ΔEt/o-FE < ΔEt/o-AFE, where ΔEt/o-FE denotes the energy barrier between the t and o-FE phases, and ΔEt/o-AFE represents the energy barrier between the t and o-AFE phases. However, when the annealing temperature reaches 1000 °C, the observed Raman vibrations align with the representative o-FE phase28,46, suggesting ΔEt/o-FE < Eh < ΔEt/o-AFE. The Raman vibrational peaks of the o-FE phase exhibit limited dependence on the polarization of the pump light, mainly due to the presence of a multiphase mixture at the nanometer scale (Supplementary Fig. 25). The subsequent ferroelectric switching characterization was also conducted (Supplementary Figs. 26 and 27, Supplementary Note 3), and the piezoresponse force microscopy (PFM) investigation further confirms the existence of the o-FE phase owing to the stable polarization switching. Consequently, most t-phase components transform into the o-FE phase rather than the o-AFE phase (Fig. 5f, g), with the o-FE phase accounting for 48% of the phase component (Supplementary Fig. 23b), about ~4.5 folds higher than that obtained via the slow-quenching strategy (11%). As the annealing temperature is further increased to 1200 °C, the Raman signals of the o-AFE gradually become more pronounced than those of the o-FE phase, indicating that the condition ΔEt/o-FE < ΔEt/o-AFE < Eh favor the transformation of the t-phase component into the o-AFE phase, on account of energetically favorable. This finding provides a controllable t-to-o phase modulation scheme that directly optimizes the o-FE phase component in the bulk crystal by a combination of fast quenching and post-annealing.

Regarding the slow-quenching strategy (Fig. 5f, g), the t-to-o phase transformation occurs during the cooling process from the growth temperature (~2800 °C). Therefore, the primary o phase within the as-grown Lu:Hf1−xZrxO2 bulk crystals is the o-AFE phase, as the Eh exceeds both ΔEt/o-AFE and ΔEt/o-FE. Additionally, the slow-quenching strategy generates a weaker chemical pressure compared to the fast-quenching strategy, owing to a slower cooling rate reducing the difference between ΔEt/o-FE and ΔEt/o-AFE6,17. As a result, within the annealed slow-quenched sample, the o-AFE phase is more likely to form due to its lower formation energy compared to the o-FE phase. The subsequent post-annealing experiments indicate that even under the optimal annealing temperature for fast-quenching to achieve the o-FE phase (1000 °C), the o phase generated within the annealed slow-quenched samples is predominantly the o-AFE phase (Supplementary Fig. 28)6. The alteration of annealing temperature and atmosphere has minimal impact on the dominating o phase in annealed slow-quenched samples, corroborating the importance of the energy barrier difference between ΔEt/o-FE and ΔEt/o-AFE, which is influenced by the cooling rate during crystal growth. These findings validate the vital role of the metastable t phase in determining the subsequent formation of o phases within Lu:Hf1−xZrxO2 bulk crystals, providing valuable insights into the nature behind the t-to-o phase evolution.

Discussion

The challenge of understanding the formation of the ferroelectric phase from the non-polar phase in HfO2-based materials poses a significant hurdle to comprehending the intricate structure-property interplay between device manufacturing and their ferroelectric performances1,6,47,48,49. Although different ferroelectric crystal structures have been proposed over the past decade, the relevant research has predominantly focused on phase identification. The direct observing evidence for the non-polar to ferroelectric phase evolution at the atomic scale remains challenging due to the small grain size (~20 nm) and the inherent multiphase nature in nanoscale thin films6,50. We achieve a controllable polymorphic engineering through composition optimization, by understanding the synergistic effects of co-doping with Lu3+ and Zr4+ ions. Introducing Lu3+ ions addresses the challenge of the m-phase issue, which often complicates the HfO2-based ferroelectric formation. Co-doping with Zr4+ ions plays a vital role in adjusting the stabilization temperature range of the metastable t phase. Of particular importance is that we identify the metastable phases within the bulk crystals and provide clear evidence of the t-o phase evolution pathway by directly tracking the movement of Hf and O atoms, explicitly elucidating the non-polar to ferroelectric structural change and the associated polarization variation. The combination of fast quenching and post-annealing further ascertains the controllable t-to-o transformation mechanism and provides a feasible method for optimization of o-FE phase component within the HfO2-based materials. As shown in Supplementary Table 1, various RE3+ ions can be utilized to control the polymorphic transformation within HfO2-based bulk crystals, though only a few, such as Lu3+, Y3+, and Gd3+, have been explored17. In future optimization efforts for the o-FE phase in HfO2-based bulk crystals, optimizing the appropriate RE3+ ion could be an effective approach. Additionally, comprehensively coordinating the RE and Zr doping concentrations is crucial, given the sensitivity of RE3+ ions in influencing the phase evolution and the strong correlation between Zr4+ ions and the t-o transformation temperature. Beyond that, developing a controllable t-o phase evolution route during the post-annealing process could be another avenue for improving the o-FE content in HfO2-based bulk crystals, similar to the rapid thermal processing used in HfO2-based films6. Notably, these results obtained in this study underscore the significance of adopting a bulk-state perspective when investigating the phase transformation mechanisms in HfO2-based materials51. This approach also facilitates the exploration of the domain wall structure at a unit-cell level and the associated domain evolution15,52,53. The insights gained from this research greatly enhance our understanding of the ferroelectric mechanisms in HfO2-based materials54, facilitating the development of electronic and photonic functional devices with fluorite-structured materials that are compatible with CMOS technology55. This echoes the functionalities observed in applications involving perovskite-based materials.

In brief, our research represents a breakthrough in understanding the non-polar to ferroelectric phase evolution within Lu:Hf1−xZrxO2 bulk crystals, achieved through a comprehensive understanding of the regulatory role of Lu3+ and Zr4+ ions. We find that the main source of ferroelectricity in these bulk crystals is the t-to-o phase transition, consistent with the observations in thin films. Furthermore, we elucidate the intricate process of t-o phase evolution by directly observing the dynamic movement of Hf and O atoms, as well as the precise structural alterations. Finally, we develop a controllable t-to-o transformation route by combining fast quenching with post-annealing process, which effectively improves the ferroelectric-phase component within bulk crystals. These findings bridge the gap between bulk and ultra-thin HfO2-based ferroelectric materials, providing profound insights into their ferroelectric origin. We anticipate that this study, serving as a paradigm for producing large-sized bulk HfO2-based ferroelectric crystals, will advance our understanding of nanoscale ferroelectric domain evolution in fluorite-structured materials, which will greatly benefit the development of CMOS-compatible devices in ferroelectrics, piezoelectrics, and pyroelectrics.

Methods

Crystal growth

The Lu:HfO2, Gd:HfO2, and Lu:Hf1-xZrxO2 bulk crystals were grown by the OFZ method with a four-ellipsoidal-mirror furnace (Crystal Systems Inc., FZ-T-12000-X-I-S-SU), which could realize the heating temperature to 3000 °C. For the optimal growth parameters, the feed and seed rod rotation rates were set at 10 rpm and 5 rpm, respectively. The growth rate was set at 20 mm h−1, and the flow rate of O2 was fixed at 150 ml min−1. The difference between the slow-quenching and fast-quenching strategies was concentrated in the cooling stage of the crystal growth process. The slow-quenching case corresponded to a slow cooling from the growth temperature to room temperature in ~5.5 h, while the fast-quenching case removed the as-grown Lu:Hf0.6Zr0.4O2 (10 at.%) bulk crystal from the heating zone within 2 s. Regarding post-annealing, the heating and cooling rates were 5 °C min−1 for temperatures below 1000 °C and 3 °C min−1 for temperatures above 1000 °C.

XRD, DSC, and dielectric measurements

The as-obtained Lu:Hf1-xZrxO2 bulk crystals were directly used for the related characterizations. The room-temperature XRD measurements were carried out on a Rigaku diffractometer (smartlab 3 kW) with a Cu Kα radiation source, and the step size was 0.01°. After confirming the coexistence of different phases within the bulk crystals by the Raman, XRD, SHG, and iDPC-STEM analyses, we refined the as-measured XRD data employing the relevant standard cards of different HfO2 phases using the TOPAS-4.2 software. The temperature-dependent in-situ XRD measurements were analyzed by a Rigaku diffractometer (smartlab, 9 kW) with a Cu Kα radiation source. The diffraction data were collected after a delay of 5 min to maintain thermal balance. The heating rate was 10 °C min−1, and the scanning rate was 0.01° step−1. The DSC data of Lu:Hf1-xZrxO2 were measured by employing a TA DISCOVERY (SDT650) synchronous thermal analyzer. The whole process was in the air atmosphere, the surveyed temperature range was from 30 to 1000 °C. Both the heating and cooling rates were 5 °C min−1. The temperature-dependent dielectric constant εr was surveyed using an LCR meter (ZX8528A, Zhixin Precision Electronics) with a heating rate of 5 °C min−1.

XPS, Raman, and SHG characterizations

The room-temperature X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) survey was conducted with Thermo Fisher ESCALAB XI+ equipped with monochromatic Al-Kα radiation. Room-temperature Raman spectra were surveyed with an iHR550 Raman spectrometer and a 632-nm He-Ne laser (5 mW). The room-temperature second harmonic generation (SHG) investigation was realized with an iHR550 Raman spectrometer and a femtosecond laser (1030 nm, 250 fs, 200 kHz).

STEM analysis

The direction of the as-grown crystal specimens was confirmed by EBSD based on Carl Zeiss crossbeam 550 L FIB-SEM. The electron transparent sample for the STEM observation was prepared by a Carl Zeiss crossbeam 550 L FIB-SEM using the conventional lift-out method. The integrated differential phase-contrast scanning transmission electron microscopy (iDPC-STEM) experiments were carried out at 300 kV using a ThermoFisher Scientific Themis Z microscope, equipped with a probe corrector and a four-segment DF4 detector. The convergence angle was 25 mrad, and the collection angle for iDPC-STEM imaging was 6–20 mrad. Fourier-filtered iDPC-STEM images were analyzed by CalAtom Software to extract the atomic position of Hf/Zr/Lu and non-polar O ions by multiple-ellipse fitting. The positions of polarized O ions were extracted by line profile using Gatan Microscopy Suite Software (Version 3.22.1461.0). We extracted the black-white intensity color scales of the STEM images from the “dm3” files, representing the relative electron scattering intensity. The white regions correspond to heavy Hf/Zr/Lu elements, while the dark regions denote light O elements or background. The polarization arrow length of each horizontal polarization vector shown in Fig. 4a was drawn based on the horizontal displacement of O atoms (δO, detailed elucidation in Supplementary Fig. 18) in the polarization layer of each cluster, with a twofold scaling factor. As present in Fig. 4d, the color change expressed the vertical Hf-Hf bond distance difference of different clusters. The variation range of color from blue to yellow corresponded to a distance range from 226.1 to 281.0 pm. We analyzed GPA using a Digital Micrograph plugin (HREM Research Inc. https://www.hremresearch.com/gpa/) with the “dm3” file from the iDPC-STEM characterizations43,44,45. For the region containing both t and o phases, we select the parent t phase as the reference owing to its <110> orientation closely matching those of <100> (or <001>) orientation within the o phase. In contrast, in the o-phase region, we utilize the primary o-phase component as the reference phase.

Data availability

The experimental data generated in this study are provided in the Supplementary Information/Source data file. The uploaded source data includes the obtained data that can reproduce all the findings of this study. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Kang, S. et al. Highly enhanced ferroelectricity in HfO2-based ferroelectric thin film by light ion bombardment. Science 376, 731–738 (2022).

Khan, A. I., Keshavarzi, A. & Datta, S. The future of ferroelectric field-effect transistor technology. Nat. Electron. 3, 588–597 (2020).

Noheda, B., Nukala, P. & Acuautla, M. Lessons from hafnium dioxide-based ferroelectrics. Nat. Mater. 22, 562–569 (2023).

Cheema, S. S. et al. Enhanced ferroelectricity in ultrathin films grown directly on silicon. Nature 580, 478–482 (2020).

Cheema, S. S. et al. Emergent ferroelectricity in subnanometer binary oxide films on silicon. Science 376, 648–652 (2022).

Schroeder, U., Park, M. H., Mikolajick, T. & Hwang, C. S. The fundamentals and applications of ferroelectric HfO2. Nat. Rev. Mater. 7, 653–669 (2022).

Kim, K. H., Karpov, I., Olsson, R. H. & Jariwala, D. Wurtzite and fluorite ferroelectric materials for electronic memory. Nat. Nanotechnol. 18, 422–441 (2023).

Cheema, S. S. et al. Ultrathin ferroic HfO2-ZrO2 superlattice gate stack for advanced transistors. Nature 604, 65–71 (2022).

Ohtaka, O. et al. Phase relations and volume changes of hafnia under high pressure and high temperature. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 84, 1369–1373 (2004).

Ohtaka, O. et al. Phase relations and equations of state of ZrO2 under high temperature and high pressure. Phys. Rev. B 63, 174108 (2001).

Böscke, T. S., Müller, J., Bräuhaus, D., Schröder, U. & Böttger, U. Ferroelectricity in hafnium oxide thin films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 99, 102903 (2011).

Wei, Y. et al. A rhombohedral ferroelectric phase in epitaxially strained Hf0.5Zr0.5O2 thin films. Nat. Mater. 17, 1095–1100 (2018).

Wang, Y. et al. A stable rhombohedral phase in ferroelectric Hf(Zr)1+xO2 capacitor with ultralow coercive field. Science 381, 558–563 (2023).

Huan, T. D., Sharma, V., Rossetti, G. A. & Ramprasad, R. Pathways towards ferroelectricity in hafnia. Phys. Rev. B 90, 064111 (2014).

Silva, J. P. B. et al. Roadmap on ferroelectric hafnia- and zirconia-based materials and devices. APL Mater. 11, 089201 (2023).

Shimizu, T. et al. The demonstration of significant ferroelectricity in epitaxial Y-doped HfO2 film. Sci. Rep. 6, 32931 (2016).

Xu, X. et al. Kinetically stabilized ferroelectricity in bulk single-crystalline HfO2. Y. Nat. Mater. 20, 826–832 (2021).

Du, H. et al. Multiple polarization orders in individual twinned colloidal nanocrystals of centrosymmetric HfO2. Matter 4, 986–1000 (2021).

Li, X. et al. Ferroelastically protected reversible orthorhombic to monoclinic-like phase transition in ZrO2 nanocrystals. Nat. Mater. 23, 1077–1084 (2024).

Lee, H. J. et al. Scale-free ferroelectricity induced by flat phonon bands in HfO2. Science 369, 1343–1347 (2020).

Cheng, Y. et al. Reversible transition between the polar and antipolar phases and its implications for wake-up and fatigue in HfO2-based ferroelectric thin film. Nat. Commun. 13, 645 (2022).

Ding, W., Zhang, Y., Tao, L., Yang, Q. & Zhou, Y. The atomic-scale domain wall structure and motion in HfO2-based ferroelectrics: a first-principle study. Acta Mater. 196, 556–564 (2020).

Shevchenko, A., Lopato, L. & Kir’yakova, I. Interaction of HfO2 with Y2O3, Ho2O3, Er2O3, Tm2O3, Yb2O3 and Lu2O3 at high temperatures. Izv. Akad. Nauk SSSR, Neorg. Mater. 20, 1991–1996 (1984).

Yashima, M. et al. Formation of metastable forms by quenching of the HfO2-RO1.5 melts (R = Gd, Y and Yb). J. Phys. Chem. Solids 57, 289–295 (1996).

Dhanaraj, G., Byrappa, K., Prasad, V. & Dudley, M. Springer Handbook of Crystal Growth, Chapter 12 (eds. Dabkowska, H. A. & Dabkowski, A. B.) 367–391 (Springer, 2010).

Qi, Y. et al. Stabilization of competing ferroelectric phases of HfO2 under epitaxial strain. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 257603 (2020).

Fan, S. et al. Vibrational fingerprints of ferroelectric HfO2. npj Quantum Mater. 7, 32 (2022).

Johnson, B. & Jones, J. L. Ferroelectricity in Doped Hafnium Oxide: Materials, Properties and Devices (eds. Schroeder, U., Hwang, C. S. & Funakubo, H.) 25–45 (Woodhead, 2019).

Xu, L. et al. Kinetic pathway of the ferroelectric phase formation in doped HfO2 films. J. Appl. Phys. 122, 124104 (2017).

Schroeder, U. et al. Impact of different dopants on the switching properties of ferroelectric hafniumoxide. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 53, 08LE02 (2014).

Müller, J. et al. Ferroelectricity in simple binary ZrO2 and HfO2. Nano Lett. 12, 4318–4323 (2012).

Park, M. H. et al. Surface and grain boundary energy as the key enabler of ferroelectricity in nanoscale hafnia-zirconia: A comparison of model and experiment. Nanoscale 9, 9973–9986 (2017).

Park, M. H. et al. Morphotropic phase boundary of Hf1-xZrxO2 thin films for dynamic random access memories. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 10, 42666–42673 (2018).

Park, M. H., Lee, Y. H. & Hwang, C. S. Understanding ferroelectric phase formation in doped HfO2 thin films based on classical nucleation theory. Nanoscale 11, 19477–19487 (2019).

Mimura, T. et al. Effects of heat treatment and in situ high-temperature X-ray diffraction study on the formation of ferroelectric epitaxial Y-doped HfO2 film. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 58, SBBB09 (2019).

Mimura, T., Shimizu, T., Katsuya, Y., Sakata, O. & Funakubo, H. Thickness- and orientation-dependences of Curie temperature in ferroelectric epitaxial Y doped HfO2 films. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 59, SGGB04 (2020).

Nukala, P. et al. Reversible oxygen migration and phase transitions in hafnia-based ferroelectric devices. Science 372, 630–635 (2021).

Luo, Q. et al. A highly CMOS compatible hafnia-based ferroelectric diode. Nat. Commun. 11, 1391 (2020).

Lazić, I., Bosch, E. G. T. & Lazar, S. Phase contrast STEM for thin samples: integrated differential phase contrast. Ultramicroscopy 160, 265–280 (2016).

Gauquelin, N. et al. Determining oxygen relaxations at an interface: a comparative study between transmission electron microscopy techniques. Ultramicroscopy 181, 178–190 (2017).

Li, X. et al. Polarization switching and correlated phase transitions in fluorite-structure ZrO2 nanocrystals. Adv. Mater. 35, 2207736 (2023).

Zhou, D., Chen, Z. & Liao, X. Microstructural evolution and ferroelectricity in HfO2 films. Microstructures 2, 2022007 (2022).

Zhu, Y., Ophus, C., Ciston, J. & Wang, H. Interface lattice displacement measurement to 1 pm by geometric phase analysis on aberration-corrected HAADF STEM images. Acta Mater. 61, 5646–5663 (2013).

Peters, J. J. P. et al. Artefacts in geometric phase analysis of compound materials. Ultramicroscopy 157, 91–97 (2015).

Rouvière, J. L. & Sarigiannidou, E. Theoretical discussions on the geometrical phase analysis. Ultramicroscopy 106, 1–17 (2005).

Musfeldt, J. L. et al. Structural phase purification of bulk HfO2:Y through pressure cycling. PNAS 121, e2312571121 (2024).

Hudak, B. M. et al. Real-time atomistic observation of structural phase transformations in individual hafnia nanorods. Nat. Commun. 8, 15316 (2017).

Shi, S. et al. Stabilizing the ferroelectric phase of Hf0.5Zr0.5O2 thin films by charge transfer. Phys. Rev. Lett. 133, 036202 (2024).

Yun, Y. et al. Intrinsic ferroelectricity in Y-doped HfO2 thin films. Nat. Mater. 21, 903–909 (2022).

Zhou, P. et al. Intrinsic 90° charged domain wall and its effects on ferroelectric properties. Acta Mater. 232, 117920 (2022).

Mikolajick, T. & Schroeder, U. Ferroelectricity in bulk hafnia. Nat. Mater. 20, 718–719 (2021).

Wu, Y. et al. Unconventional polarization-switching mechanism in (Hf,Zr)O2 ferroelectrics and its implications. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 226802 (2023).

Peng, R. et al. Revealing the role of spacer layer in domain dynamics of Hf0.5Zr0.5O2 thin films for ferroelectrics. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2403864 (2024).

Mukherjee, B., Fedorova, N. S., Íñiguez-González, J. & Cheema, S. S. First-principles predictions of HfO2-based ferroelectric superlattices. npj Comput. Mater. 10, 153 (2024).

Fina, I. & Sánchez, F. Seeing ferroelectric phase transitions. Nat. Mater. 23, 1015–1016 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We thank C.Wang (Shandong University) for the useful discussion on the dielectric investigation and thank Z.Ye (University of Jinan) for the help of structural refinement. This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 52025021 (H.Y.) and 52472008 (S.W.)), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2021YFB3601504 (H.Z.)), the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (ZR2022LLZ005 (S.W.)), the Future Plans of Young Scholars at Shandong University (S.W.), and Shandong Excellent Young Scientists Fund Program (Overseas) (grant no. 2023HWYQ-041 (N.L.)).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.W., H.Y., S.Z. and H.Z. designed and conceived the research idea. S.W., Y.S. and H.Y. performed the crystal growth and related characterizations, including XRD, Raman, XPS, SHG, P-E, and PFM. S.W., N.L., X.Y., Y.H. and P.N. performed the STEM observation and relevant analysis under the guidance of B.G. and H.Y. S.W. and Y.S. wrote the original manuscript, H.Y., S.Z. and H.Z. revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the discussion of the results.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Shiyu Fan, Pavan Nukala and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, S., Shen, Y., Yang, X. et al. Unlocking the phase evolution of the hidden non-polar to ferroelectric transition in HfO2-based bulk crystals. Nat Commun 16, 3745 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-59018-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-59018-4

This article is cited by

-

Atomic-scale mechanism unlocks thermal-stable high-κ performance in HfO2 via coherent interfaces

Nature Communications (2026)

-

Multisensory Neuromorphic Devices: From Physics to Integration

Nano-Micro Letters (2026)