Abstract

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) manipulates the host immune system to establish a persistent colonization, posing a serious threat to human health, but the mechanisms remain poorly understood. Here we integrate single-cell RNA sequencing and TCR profiling for analyzing 187,192 cells from 11 H. pylori-negative and 12 H. pylori-positive individuals to describe the human gastric ecosystem reprogrammed by H. pylori infection, as manifested by impaired antigen presentation and phagocytosis function. We further delineate a monocyte-to-C1QC+ macrophage differentiation trajectory driven by H. pylori infection, while T cell responses exhibit broad functional impairment and hyporesponsiveness with restricted clonal expansion capacity. We also identify an HLA-DRs- and CTLA4-expressing T cell population residing in H. pylori-inhabited stomach that potentially contribute to immune evasion. Together, our findings provide single-cell resolution information into the immunosuppressive microenvironment shaped by H. pylori infection, offering critical insights for developing novel therapeutic approaches to eliminate this globally prevalent pathogen.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori), a gram-negative and transmissible pathogen that colonizes the stomachs of nearly half of the global population, poses a severe threat to human health1. Infection is typically acquired in childhood and persists lifelong unless treated. Individuals infected with this pathogen always develop a sustained immune infiltrate (chronic gastritis), which may progress through atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia (IM) to gastric adenocarcinoma, as outlined by the Correa cascade2. Designated by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a “high-priority” pathogen3, H. pylori eradication is universally recommended by the 2015 Kyoto consensus for all infected individuals unless there are compelling counterindications4.

H. pylori infection triggers a robust host immune response characterized by leukocyte infiltration in the gastric mucosa, including lymphocytes (T/B cells), monocytes, macrophages, neutrophils, mast cells, and dendritic cells. Infected individuals exhibit H. pylori-specific CD4+ T cells in both gastric tissue and peripheral blood, accompanied by a T helper cell (Th)1-polarized response and Th17-mediated IL-17A upregulation, which induces pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6) and chemokines (CXCL1, CCL2, CCL7) release, recruiting neutrophils and macrophages5,6. Recent studies by Maximilian et al. further identified CD8+ T cell-mediated immunity contributing to early bacterial control7. Despite these responses, H. pylori successfully establishes a persistent infection leading to chronic inflammation.

Multiple lines of evidence suggest that H. pylori has evolved strategies to orchestrate immune suppression by remodeling its bioactive molecules and manipulating host immunity to reduce bacterial clearance8. Compared with other gram-negative pathogens, its lipopolysaccharides and flagellins exhibit structural discrepancies that evade recognition by TLR4 and TLR59,10. Additionally, H. pylori employs multiple strategies to subvert adaptive immunity: the virulence factor outer inflammatory protein A (OipA) induces tolerogenic programming in dendritic cells (DCs) by inhibiting their maturation11, while vacuolating cytotoxin (VacA) suppresses DC co-stimulatory molecules (CD40, CD80, CD86), thereby dampening T cell activation12. We recently demonstrated that H. pylori subverts autophagosomes to create a pro-survival niche by disrupting lysosomal acidification and maturation13,14. However, these evidence was mostly obtained from in vitro and murine studies. Systematic characterization of clinical samples is needed to elucidate H. pylori’s ability to manipulate host innate and adaptive immune responses to avoid eradication. Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has enabled host–pathogen interactions to be examined at an unprecedented resolution15.

In this study, we investigate the gastric ecosystem reprogramming in H. pylori-colonized human stomach by integrating single-cell RNA and T cell receptor (TCR) sequencing on 187,192 cells obtained from 11 H. pylori-negative and 12 H. pylori-positive donors with chronic gastritis. We further perform in vitro and in vivo experiments to validate key findings in the discovery cohort. Using this approach, we reveal a H. pylori-driven immunosuppressive microenvironment, and delineate unique alterations in immune responses that facilitate H. pylori persistence, providing actionable insights for developing therapeutic strategies to eradicate this pathogen.

Results

Cohort characteristics and single cell profiling of H. pylori-reprogrammed human gastric ecosystem

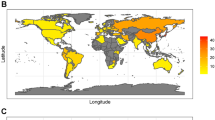

Using strict inclusion and exclusion criteria (See “Methods”), we recruited 12 patients with newly diagnosed H. pylori-associated chronic gastritis and 11 individuals with H. pylori-negative gastritis to systematically survey gastric ecosystem reprogramming (Supplementary Fig. 1a). All subjects were younger than 35. Serologic testing revealed that all H. pylori strains were genotypically CagA-, VacA-, UreA-, and UreB-positive. We collected 22 gastric specimens and 17 paired peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) samples from these subjects. H. pylori-positive gastric biopsy and paired PBMC samples are annotated as PT and PP; corresponding samples from H. pylori-negative participants are annotated as NT and NP, respectively (Fig. 1a). Quantitative PCR (qPCR) analysis demonstrated significantly elevated OipA expression levels in H. pylori-positive gastric specimens compared to their H. pylori-negative counterparts (Supplementary Fig. 1b, Supplementary Table 1). Detailed clinical and pathological information are provided in Supplementary Table 2.

a Workflow representing the process of sample collection, single cell dissociation, separation, and scRNA-seq using the 10× platform. b Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) plot showing the annotation and color codes for major cell types in H. pylori-negative or H. pylori-positive human Peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) or gastric ecosystem. c UMAP plots showing the cell origin from NP (n = 10), NT (n = 11), PP (n = 7) or PT (n = 11) samples. d Histogram showing the proportion of major cell types in each analyzed subject. e The expression of marker genes in the annotated cell types are showed by bubble heatmap. Dot size indicates fraction of expressing cells, colored based on normalized expression levels. f Boxplots showing the proportion of each major cell clusters in PBMC (Left, NP = 10, PP = 7) or gastric tissue (Right, NT = 11, PT = 11) samples. Quantitative data are shown as Mean ± SD. P values are calculated using the two-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test, and are shown in the figure panels. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001.

For scRNA-seq, we used microbead separation to enrich samples for immune (CD45+) cells, and subjected live, dissociated cells to single-cell transcriptome sequencing. After strict data pre-processing and doublet removal, the dataset contained 187,192 high-quality cell measurements. On average, 1195 genes and 3090 unique molecular identifiers (UMI) per cell were detected in each sample, with no obvious batch effects across subjects (Supplementary Fig. 1c). P1T sample data were excluded due to a library exception (average: >7000 genes per cell).

Using differential expression of canonical gene markers of the main expected cell types, we manually annotated unsupervised graph-based clusters, revealing 98,339 T and natural killer (NK) cells (52.5%, CD3D, NKG7); 32,905 B and plasma cells (17.6%, CD19, CD79A); and 27,310 myeloid lineage cells (e.g., monocytes, macrophages, 14.6%, LYZ, CD14). Due to the limited efficiency of microbeads separation, we also captured 28,638 (15.3%) non-immune (CD45-) cells, designated as gastric tissue and proliferating cells (high ENG, EPCAM, MKI67 expression) (Figs. 1b–e, and Supplementary Fig. 1d-f, Supplementary Data 1). The lack of neutrophil and eosinophil acquisition was attributable to well-known technical limitations16. The identified cell types were shared among individuals and between H. pylori-negative and -positive samples (Supplementary Figs. 1d–e). We next assessed the enrichment of each cell type in both tissue and PBMC samples by calculating their relative abundances within individual sample and performing the ratio of observed to expected cell numbers (Ro/e) analysis. Comparative analysis revealed striking compositional difference between cell clusters from H. pylori-positive versus negative gastric biopsies, exemplified by increased proportions of B and plasma cells coupled with decreased frequencies of gastric tissue and proliferating cells in H. pylori-positive gastric samples (Fig. 1f, and Supplementary Fig. 1g). These findings suggest a reprogramming of the gastric ecosystem driven H. pylori colonization.

Repressed antigen processing and presentation capacities of H. pylori-infected APCs

Unsupervised clustering of myeloid cells yielded 16 subtypes, including eight monocyte clusters, four DC clusters, two macrophage clusters, and one cluster each of mast cells and megakaryocytes (Figs. 2a–d, and Supplementary Figs. 2a, b). Mast cells (Cluster 5) were mostly recruited from gastric biopsies (Supplementary Fig. 2c) and distinguished by markedly elevated expression of canonical mast cell markers such as TPSAB1, CPA3, KIT17. A higher proportion of these cells was detected in PT than in NT samples (Fig. 2e). Megakaryocytes (Cluster 11) were primarily enriched in PBMCs (Fig. 2e, Supplementary Fig. 2c), and characterized by expression of PF4, PPBP and GP9 (Fig. 2d)18.

a–c UMAP plot showing 16 subsets in myeloid lineage derived from H. pylori-negative or -positive individuals. a Each subcluster is color-coded according to cell type. b, c Cell origins are shown by (b) patient origin, and (c) H. pylori-negative (Upper) or -positive origin (Down). d Bubble heatmap showing marker genes across all subclusters from myeloid lineage. Dot size indicates fraction of expressing cells, colored based on normalized expression levels. e Boxplots showing the proportion of each myeloid subset in PBMC (Upper, NP = 10, PP = 7) or gastric tissue (Down, NT = 11, PT = 11) samples. Quantitative data are shown as Mean ± SD. P values are calculated using the two-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test, and are shown in the figure panels. f Heatmap showing the elevated genes expression (scaled mean expression) in each “classical” monocyte cluster. Colored based on normalized expression levels. g Up-regulated pathways in Cluster 7 by GO enrichment analysis. h Heatmap showing the top 10 activated transcriptional factors (TFs) for PBMC-derived Cluster 7 with or without H. pylori infection by SCENIC analysis. i Violin plot showing the MHC-II scores of CD14++CD16- monocytes from NP or PP samples. Violin outline width represents density. Horizontal line represents median. The p value is calculated using the two-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test, and is shown in the figure panels. j Violin plots showing the MHC-II scores of CD14+CD16+ (Left), or Mono 4 (Right) monocytes from NP or PP samples. Violin outline width represents density. Horizontal line represents median. P values are calculated using the two-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test, and are shown in the figure panels. k Violin plot showing the MHC-II scores of Mono 3 monocytes from NT or PT samples. Violin outline width represents density. Horizontal line represents median. The p value is calculated using the two-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test, and is shown in the figure panels. l C57/BL6J mice were orally gavaged with BHI (n = 5) or H. pylori PMSS1 strain (n = 5) for two months. Mice peripheral blood was collected to enrich PBMCs. Single immune cells were gated and dead cells were excluded via FVS450 signal. Mice peripheric monocytes were defined by CD45+Ly6G-CD11b+CD172a+. Flow cytometry analysis was performed to detect the expression levels (Median fluorescence intensity, MFI) of I-A/I-E in mice peripheral monocytes. Quantitative data are shown as Mean ± SD. The p value is calculated using the two-tailed student’s unpaired t-test, and is shown in the figure panels. m Violin plots showing the MHC-II scores of CD1C+ DCs from PBMC (Left) or gastric tissue (Right) samples with or without H. pylori infection. Violin outline width represents density. Horizontal line represents median. P values are calculated using the two-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test, and are shown in the figure panels. n Violin plots showing the MHC-II scores of CLEC9A+ (Left) or CD1C-CD141- (Right) DCs from NP or PP samples. Violin outline width represents density. Horizontal line represents median. P values are calculated using the two-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test, and are shown in the figure panels. o DC2.4 cells were infected with H. pylori TN2GF4 or NCTC 11637 strains (MOI = 1:10) for three days. Single cells were gated and dead cells were excluded via FVS450 signal. DC cells were defined by CD45+CD11b+CD11c+. The expression (MFI) of I-A/I-E in DC cells were determined (n = 3 replicates for each group). Quantitative data are shown as Mean ± SD. P values are calculated using ordinary one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison tests with adjustments, and are shown in the figure panels. The statistical significance of the data was calculated from one of three independent experiments with similar results. p C57/BL6J mice were administrated with BHI (n = 5) or H. pylori PMSS1 strain (n = 5) for two months. PBMCs were isolated from the blood of BHI or PMSS1-treated mice and subjected for flow cytometry analysis. Single immune cells were gated and dead cells were excluded via FVS450 signal. Mice peripheric DCs were defined by CD45+Ly6G-CD11b+CD11c+. The expression levels (MFI) of I-A/I-E in mice peripheral DCs were determined. Quantitative data are shown as Mean ± SD. The p value is calculated using the two-tailed student’s unpaired t-test, and is shown in the figure panels. q Gastric biopsies from H. pylori-negative (n = 13) or -positive (n = 12) patients were collected to isolate immune cells, then subjected them for flow cytometry analysis. Single immune cells were gated and dead cells were excluded via Zombie-NIR signal. Human gastric DCs were defined by CD11b+CD11c+. The expression levels (MFI) of HLA-DR in human gastric DCs derived from H. pylori-negative (n = 13) or H. pylori-positive (n = 12) patients were determined. Quantitative data are shown as Mean ± SD. The p value is calculated using the two-tailed student’s unpaired t-test, and is shown in the figure panels. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001.

We captured four classical monocyte subsets (Clusters 0, 2, 7, 9), characterized by CD14, FCN1, and VCAN expression and lack of CD16 (FCGR3A) and CX3CR1 expression (Figs. 2a–d, and Supplementary Figs. 2a, b)19. We then investigated the proportion of each of the four subsets in patients and found that these classical monocytes were mostly derived from PBMC samples (Fig. 2e, and Supplementary Fig. 2c). In-depth inspection of signature genes in CD14++CD16- monocyte populations revealed elevated expression of multiple genes related to macrophage recruitment, activation and inflammasome maturation, including CCL3, CXCL8, IL1B and NLRP3 in Cluster 7 compared to the other three subsets (Fig. 2f)20,21. Correspondingly, pathways associated with chemokine production and macrophage activation were selectively enriched in this cluster (Fig. 2g, and Supplementary Fig. 2d). By examining regulatory networks in NP- or PP-derived Cluster 7 (Fig. 2h), we observed marked activation of FOSB and JUNB, which encode transcription factors (TFs) essential for monocyte–macrophage differentiation and macrophage activation, after H. pylori infection22,23. FLI1, encoding critical regulators of monocyte differentiation and development, was also strongly expressed in Cluster 7 post-infection24,25. Taken together, these results suggest a potential involvement of Cluster 7 in macrophage differentiation and maturation in response to H. pylori challenge.

Major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II molecules are essential for processing and presenting exogenous pathogen antigens for CD4+ T cell activation26. H. pylori is predominantly considered a non-invasive pathogen that colonizes the extracellular mucosa of the human stomach. To investigate its impact on monocyte function, we calculated the MHC-II scores in these CD14++CD16– monocytes (Supplementary Table 3). In H. pylori-infected PP samples, Clusters 0, 2 and 9 showed significant reductions in MHC-II scores (Supplementary Fig. 2e). Cluster 7 exhibited consistently attenuated MHC-II levels in both PP and PT samples (Supplementary Fig. 2f). Furthermore, by aggregating data from PBMC-derived CD14++CD16– monocytes, we identified a marked decline in MHC-II expression following H. pylori infection (Fig. 2i). These results indicate that H. pylori infection suppresses antigen processing and presentation capacities in these monocytes, which may promote an immunosuppressive microenvironment post-infection.

We also captured a subset of non-classical monocytes (Cluster 13, Mono-CD16++CD14-), primarily enriched in PBMCs, characterized by high expression of FCGR3A (CD16), CX3CR1, RHOC, MS4A7, and SERPINA1, but lacking CD14 expression (Fig. 2a–e, and Supplementary Fig. 2a–c). Additionally, we identified a subset of intermediate monocytes (Cluster 1, Mono-CD14+CD16+) enriched in PBMCs, showing concurrent modest expression of CD14 and CD16 alongside conventional monocyte markers such as VCAN, S100A8, S100A9 and FCN1 (Figs. 2a–e, and Supplementary Fig. 2a–c). Similarly, a monocyte population (Cluster 15, Mono3), enriched in the stomach, exhibited elevated expression of MXD1, CXCR2, CSF3R and NEAT1 (Fig. 2a–e, Supplementary Fig. 2a–c). Another population (Cluster 3, Mono4), enriched in PBMCs, displayed prominent expression of cytotoxic genes (e.g., GNLY, PRF1, CTSW) (Fig. 2a–e, Supplementary Fig. 2a–c), align with previously reported Mono3 and Mono4 cells19. Similar to CD14++CD16– monocytes, we observed decreased MHC-II levels in PBMC-enriched Mono-CD14+CD16+ and Mono4 subsets, as well as in gastric-infiltrating Mono3 following H. pylori challenge (Fig. 2j–k). These findings suggest suppressed antigen presentation activities across these monocyte populations.

To validate suppressed antigen presentation in peripheral monocytes following H. pylori colonization, we infected C57BL/6 J mice with the pathogenic, CagA-proficient H. pylori strain PMSS1 for two months (Supplementary Fig. 2g–h) and analyzed single-cell PBMC suspensions by flow cytometry (Supplementary Fig. 3a). While the proportion of CD11b+CD172a+ monocytes remained unchanged post-infection (Supplementary Fig. 2i), we detected a substantial reduction in the expression of the MHC-II molecules I-A/I-E within this population (Fig. 2l).

We identified two conventional DCs (cDC) subsets: the cDC-CD1C+ (Cluster 8) characterized by high expression of CD1C, CD1D, FCER1A and CLEC10A, and cDC-CLEC9A+ (Cluster 14) predominantly derived from gastric tissues, defined by elevated expression of CLEC9A, C1orf54 and IDO1 (Fig. 2a–e, and Supplementary Fig. 2a–c). Additionally, we identified a DC population (Cluster 4) strongly expressing FCGR3A, FTL, SERPINA1, LST1 and AIF1, but lacking CD1C and THBD (CD141), like the previously reported DC419. Thus, we designated this cluster as DC-CD1C-CD141- (Fig. 2a–e, and Supplementary Fig. 2a–c). We also captured a plasmacytoid DCs (pDC, Cluster 12) population expressing canonical markers such as TCF4, IL3RA, LILRA4, IRF7, PACSIN1, and CLEC4C (Fig. 2a–e, and Supplementary Fig. 2a–c). Notably, similar to the phenomenon observed in monocytes, we detected significantly reduced MHC-II scores in CD1C+ DCs from PP and PT samples, as well as in PBMC-enriched CLEC9A+ and CD1C-CD141- DCs following H. pylori infection (Fig. 2m–n). These findings indicate impaired antigen presentation functionality in these cDC populations post-H. pylori infection.

To validate whether H. pylori infection impairs DC antigen presentation, we established an in vitro model by infecting the immortalized murine DC cell line DC2.4 with two H. pylori strains, TN2GF4 and NCTC 11637 (Supplementary Fig. 3b)27. As anticipated, infected DCs exhibited reduced expression of I-A/I-E compared to uninfected controls (Fig. 2o). We further assessed I-A/I-E expression in peripheral CD11b+CD11c+ DCs from H. pylori-infected mice (Supplementary Fig. 3c). Consistent with observations in murine monocytes, the proportion of CD11b+CD11c+ DCs remained unchanged post-infection (Supplementary Fig. 2j). However, I-A/I-E levels were significantly down-regulated in these peripheral DCs following H. pylori challenge (Fig. 2p). Due to technical limitations in isolating leukocytes from murine gastric tissue, we instead analyzed gastric immune cells from 12 H. pylori-positive and 13 H. pylori-negative gastritis patients (Supplementary Table 4). CD45+ cells were enriched for flow cytometry (Supplementary Fig. 3d). Compared to H. pylori-negative controls, infected patients showed increased proportions of gastric CD11b+CD11c+ DCs (Supplementary Fig. 2k). Notably, HLA-DR expression was markedly reduced in gastric DCs from H. pylori-positive subjects (Fig. 2q), confirming impaired antigen-presenting capacity in DCs exposed to H. pylori.

Macrophages develop from monocyte-like precursors exhibiting an immunosuppressive phenotype following H. pylori infection

We identified two macrophage populations in our cohort (Fig. 2a–e, and Supplementary Fig. 2a–c): Cluster 6, predominantly derived from gastric tissues, was characterized by high expression of CD68, CD163, MRC1 (CD206) and CSF1R. A lower proportion of these cells was observed in PT than in NT samples. Cluster 10, derived from both PBMCs and gastric specimens, exhibited modest expression of CD68, CD163, and multiple MHC-II genes such as HLA-DRA, HLA-DRA1, HLA-DRB1 and HLA-DRB5. Comparative transcriptomic analysis of these two populations revealed elevated expression of complement C1Q-encoding genes (C1QC, C1QA, C1QB), APOE, CD163 and SLC40A1 in Cluster 6 (Fig. 3a), which we designated Macro-C1QC. Up-regulated expression of MRC1, a type I membrane glycoprotein receptor critical for phagocytosis and endocytosis28,29, suggested enhanced phagocytotic capacity. NR4A3, a tissue-resident marker30, was also highly expressed in Macro-C1QC. In contrast, Cluster 10 expressed a set of interferon-related genes (e.g., IFIT1, IFIT2, IFIT5, GBP1, GBP5) and monocyte-associated markers (PTX3, IL27, CCL7 and FN1), indicating a transitional activation state. We therefore annotated this cluster as Macro-IFIT1. Gene Set Variation Analysis (GSVA) further demonstrated remarkable enrichment of complement activation, antigen processing and presentation, and cell migration pathways in Macro-C1QC, whereas interferon signaling and leukocyte transendothelial migration pathways were enriched in Macro-IFIT1 (Fig. 3b).

a Volcano plot showing Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between C1QC+ and IFIT1+ macrophages. P values are calculated by two-sided Wilcoxon’s rank-sum test and corrected using the Benjamini-Hochberg approach. Genes highlighted in indigo have log2 fold change > 1.0 and p value < 0.05. b Differential pathways enriched in C1QC+ or IFIT1+ macrophages by GSVA analysis. c Developmental trajectory of Cluster 7 and two macrophage subsets recruited from H. pylori-positive samples is inferred by Monocle 3. The UMAP is colored by inferred pseudotime. d Violin plots showing the MHC-II scores of C1QC+ macrophages from PBMC (Left) or gastric (Right) samples with or without H. pylori infection. Violin outline width represents density. Horizontal line represents median. P values are calculated using the two-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test, and are shown in the figure panels. e Violin plots showing the MHC-II scores of IFIT1+ macrophages from PBMC (Left) or gastric (Right) samples with or without H. pylori infection. Violin outline width represents density. Horizontal line represents median. P values are calculated using the two-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test, and are shown in the figure panels. f Violin plots showing the phagocytosis scores of C1QC+ (Left) or IFIT1+ (Right) macrophages from NT or PT samples. Violin outline width represents density. Horizontal line represents median. P values are calculated using the two-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test, and are shown in the figure panels. g BMDM cells were infected with H. pylori TN2GF4 or NCTC 11637 strains (MOI = 1:50) for three days. Single cells were gated and dead cells were excluded via FVS450 signal. Macrophages were defined by CD45+CD11b+F4/80+. The expression (MFI) of I-A/I-E in BMDM cells were determined by flow cytometry analysis (n = 3 replicates for each group). Quantitative data are shown as Mean ± SD. P values are calculated using ordinary one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison tests with adjustments, and are shown in the figure panels. h Gastric biopsies from H. pylori-negative (n = 13) or -positive (n = 12) patients were collected to isolate immune cells, then subjected them for flow cytometry analysis. Single immune cells were gated and dead cells were excluded via Zombie-NIR signal. Human gastric macrophages were defined by CD11b+CD11c-. The expression levels (MFI) of HLA-DR in human gastric macrophages derived from H. pylori-negative (n = 13) or -positive (n = 12) patients were determined. Quantitative data are shown as Mean ± SD. The p value is calculated using the two-tailed student’s unpaired t-test, and is shown in the figure panels. i THP-1 cells were incubated with phorbol-12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA, 100 ng/ml) for 48 h, then infected with H. pylori TN2GF4 strain (MOI = 1:50) for three days. Cells were incubated with fluorescent beads (green) for 6 h (MOI = 1:100). Representative images of fluorescent beads in THP-1 cells were shown (Left). Twenty visual fields of each group were randomly selected to count the number of fluorescent beads (Right). Quantitative data are shown as Mean ± SD. The p value is calculated using the two-tailed student’s unpaired t-test, and is shown in the figure panels. The statistical significance of the data (g, i) was calculated from one of three independent experiments with similar results. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001.

To investigate the functional phenotypes of these macrophages, we calculated M1 and M2 polarization scores (Supplementary Fig. 4a). Both macrophage populations exhibited co-expression of M1- and M2-associated gene signatures, consistent with previous studies17,31. As described earlier, we identified a monocyte cluster (Cluster 7) that appeared to migrate and differentiate into macrophage. To assess the differentiation states of these subsets, we selected cells from Cluster 7 and the two macrophage populations in H. pylori-positive samples and reconstructed the developmental trajectory using Monocle 332. Pseudotime analysis revealed a clear differentiation trajectory originating from Cluster 7 monocytes, progressing through intermediate Macro-IFIT1, and culminating in Macro-C1QC (Fig. 3c, Supplementary Fig. 4b). This confirmed that Cluster 7 monocytes serve as cellular precursors to C1QC+ macrophages following H. pylori infection.

We next evaluated the antigen presentation and phagocytic capacities of Macro-C1QC and Macro-IFIT1 using MHC-II and phagocytosis-related gene signatures, and observed reduced MHC-II and phagocytic scores in Macro-IFIT1 compared to Macro-C1QC (Supplementary Fig. 4c, d). Notably, compared to control counterparts, both macrophage populations, whether derived from PBMCs or gastric tissues, exhibited lower MHC-II scores following H. pylori infection (Fig. 3d–e). Similarly, phagocytic scores were diminished in stomach-resident macrophages after H. pylori exposure (Fig. 3f). These findings indicate that H. pylori infection restricts both antigen presentation and phagocytic functionality in these macrophage subsets.

To determine whether H. pylori infection impairs macrophage antigen presentation and phagocytosis, we infected mouse bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) with H. pylori strains TN2GF4 and NCTC 11637. Flow cytometry analysis revealed reduced expression of the MHC-II marker I-A/I-E in infected BMDMs (Fig. 3g, and Supplementary Fig. 3e). Furthermore, we observed an increased proportion of CD11b+CD11c- macrophages in gastric immune cells from H. pylori-positive patients compared to negative controls (Supplementary Figs. 3d, 4e). Consistent with the BMDM findings, gastric CD11b+CD11c- macrophages from infected patients exhibited decreased expression of the human MHC-II marker HLA-DR (Fig. 3h). Finally, using an in vitro phagocytosis model, we confirmed that H. pylori infection impaired macrophage phagocytic capacity (Fig. 3i).

These results delineate a H. pylori-propelled cell transition trajectory from Cluster 7 monocytes, progressing through intermediate Macro-IFIT1, to Macro-C1QC. Additionally, they reveal diminished antigen processing and presentation functions in both peripheral and gastric APC lineages following H. pylori infection. This functional impairment may compromise CD4+ T cell recruitment and the initiation of adaptive immunity, thereby fostering an immunosuppressive gastric microenvironment that favors persistent H. pylori colonization.

CD8+HLA-DR+CTLA4+ T cells exhibited immunosuppressive phenotypes upon H. pylori colonization

By performing unsupervised clustering analyzes of 98,339 T/NK cells from our dataset, we identified four major cell populations: CD4+ T (33,588 cells, 34.2%), CD8+ T (41,610 cells, 42.3%), NK (16,847 cells, 17.1%), and γδT (6294 cells, 6.4%) cells (Supplementary Figs. 5a–c). NK cells were predominantly derived from peripheral blood and exhibited strong expression of canonical markers, including NCAM1 (CD56), FCGR3A (CD16) and cytotoxic genes such as PRF1, GNLY, GZMB and NKG7. γδT cells, also enriched primarily in PBMCs, showed characteristic high expression of TRDV2, TRDV9, TRGC1 and CST7. Comparative analysis of cell type enrichment in PBMCs and gastric specimens revealed a significantly higher proportion of CD4+ T cells but a lower proportion of CD8+ T cells in PT samples than in NT samples (Supplementary Fig. 5c).

Further sub-clustering analysis revealed 19 subsets of CD8+ T cells, categorized into six naïve clusters (Cluster 0, 5, 6, 7, 13 and 18), six cytotoxic clusters (Cluster 3, 8, 9, 11, 14, 17), two effector memory clusters (Cluster 2 and 15), one mucosal-associated invariant T (MAIT) cell cluster (Cluster 10), and four dysfunctional clusters (Cluster 1, 4, 12, 16) (Fig. 4a–c, Supplementary Fig. 5d–f). Naïve CD8+ T cells were identified by elevated expression of naïve-associated gene signatures including SELL, IL7R, CCR7, GPR183 and TCF733. Cytotoxic CD8+ T cells displayed robust expression of cytotoxicity-related genes such as GZMA, NKG7, GZMH, CX3CR1, GNLY and PRF134. The MAIT cell cluster (CD8-10-CCR6) exhibited defining features of CCR6, SLC4A10, and RORC expression, consistent the previously described CD8-SLC4A10 cells35. We further validated them by predominantly bearing uniquely rearranged TCR (TRAV1-2/TRAJ33, TRAV1-2/TRAJ20, or TRAV1-2/TRAJ12) (Supplementary Fig. 5g). The two effector memory clusters displayed high expression of CXCR3, CCR5, TNF, CXCR6, but lacking the naïve markers SELL and CCR7 expression34. Dysfunctional CD8+ T cell populations were distinguished by elevated expression of GZMK, PDCD1, LAYN, TIGIT, ITGAE, CTLA4, EOMES and ID233,36.

a, b UMAP plots showing 19 subsets in CD8+ T cells derived from H. pylori-negative or -positive patients. a Each subcluster is color-coded according to cell type. b Cells from H. pylori-negative (Upper) or -positive (Down) patients are shown. c Boxplots showing the proportion of each CD8+ T cell subset in PBMC (Upper) or gastric tissue (Down) samples. Quantitative data are shown as Mean ± SD. P values are calculated using the two-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test, and are shown in the figure panels. d Heatmap indicating the expression (scaled mean expression) of selected gene sets in stomach-resident CD8+ T cell subsets (Cluster 2, 4, 12, 15), including naïve, resident, inhibitory, pre-dysfunction, cytotoxicity, co-stimulatory, and MHC-II-related gene signatures. Colored based on normalized expression levels. e Boxplot showing the fractions of CD8A+HLA-DRA+CTLA4+ cells in the CD8-12-HLA-DR subset derived from NT (n = 11) or PT (n = 11) samples. The dot represents one value from individual participants. Boxplots centered at the median with hinges at 1st and 3rd quartiles and whiskers drawn from hinges to the lowest and highest points within 1.5 interquartile range. The p value is calculated using the two-tailed student’s unpaired t-test, and is shown in the figure panels. f Volcano plot showing DEGs of CD8-12-HLA-DR subset between NT and PT samples. P values are calculated by two-sided Wilcoxon’s rank-sum test and corrected using the Benjamini-Hochberg approach. Genes highlighted in purple have log2 fold change > 1.0 and p value < 0.05. g Inferred developmental trajectory of stomach-resident CD8+ T cell subsets (Cluster 2, 4, 12, 15) from H. pylori-positive samples by RNA velocity. h Developmental trajectory of stomach-resident CD8+ T cell subsets (Cluster 2, 4, 12, 15) from H. pylori-positive samples inferred by Monocle 3. The UMAP is colored by inferred pseudotime. i (Left) UMAP plot showing common clones shared among the different color-coded CD8+ T cell subsets. The thickness of the connecting lines between subtypes represents the number of shard TCR clones. (Right) The number of TCRs shared by two clusters are calculated. The two colors in every bar represent the particular two clusters sharing TCRs. j (Left) Clonotype diversity of CD8+ T cells in NT (n = 11) or PT (n = 11) samples measured by Gini-Simpson index. (Right) Clonal expansion is measured by the fraction of clonal T cells from stomach-enriched CD8+ T cell populations in NT (n = 11) or PT (n = 11) samples. The dot represents one value from individual participants. Boxplots centered at the median with hinges at 1st and 3rd quartiles and whiskers drawn from hinges to the lowest and highest points within 1.5 interquartile range. P values are calculated by two-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001.

By quantifying the enrichment of cell populations in PBMC and gastric tissues, we identified four subsets (Cluster 2, 4, 12, 15) that were predominantly enriched in gastric specimens (Supplementary Fig. 5f). Compared to NT samples, PT samples exhibited lower proportions of Cluster 2 and 15, but a higher proportion of Cluster 12 (Fig. 4c). Notably, Cluster 12 showed marked upregulation of inhibitory markers (CTLA4, LAG3, PDCD1, TIGIT, HAVCR2) alongside elevated expression of naïve genes (e.g., CCR7, TCF7, LEF1 and SELL), co-stimulatory markers (TNFRSF14, CD28, TNFRSF9), and multiple MHC-II genes (e.g., HLA-DRA, HLA-DQA1) relative to the other clusters (Fig. 4d). Thus, we annotated this population as CD8-12-HLA-DR, a subset resembling a plastic exhaustion state in CD8+ T cells recently reported in gastric adenocarcinoma37.

To investigate infection-associated inhibitory reprogramming in this subset, we quantified the proportion of CD8A+HLA-DRA+CTLA4+ cells and observed a significant increase in PT samples (Fig. 4e). Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) analysis further revealed distinct signatures between PT and NT samples (Fig. 4f): NT samples exhibited upregulation of the tissue resident gene ZNF683 and cytotoxic genes (KLRC1, KLRC2), while PT samples showed elevated expression of inhibitory genes (CTLA4, HAVCR2, TOX2), the predysfunctional marker GZMK, and MHC-II genes (HLA-DRB1, HLA-DQB1, HLA-DRA, HLA-DOA, HLA-DQB2). These findings suggest that H. pylori infection drives reduced cytotoxic activity and enhances inhibitory and MHC-II-related signatures in this CD8+ T cell subset.

Next, we determined the differentiation trajectories of CD8+ T cells in H. pylori-positive gastric samples. Both RNA velocity and Monocle 3 analyzes revealed a developmental pathway originating from CD8-12-HLA-DR cells, progressing through CD8-2-CXCR3 cells, and terminating at CD8-4-ID2 cells. These analyzes also identified an alternative differentiation route from CD8-12-HLA-DR cells directly to CD8-4-ID2 cells, bypassing the intermediate CXCR3-expressing state (Fig. 4g, h, Supplementary Fig. 5h).

TCR is the gold-standard marker for identifying T cell ancestry38. By leveraging TCR-seq data to trace clonal trajectories of CD8+ T cells, we identified 310,268 and 198,192 clonal CD8+ T cells (frequency ≥ 2) in H. pylori-negative and -positive individuals, respectively (Supplementary Figs. 5i, j, and Supplementary Data 2). We then examined shared and biased clonotypes across gastric CD8+ T subsets in each individual and observed remarkable TCR clonality sharing among the CD8-12-HLA-DR, CD8-2-CXCR3 and CD8-4-ID2 subpopulations (Fig. 4i), aligning with the differentiation trajectory and transitional relationships inferred earlier. Strikingly, while clonotype diversity (measured by the Gini–Simpson index) increased post-infection, mucosal-infiltrating CD8+ T cells exhibited markedly restricted clonal expansion (Fig. 4j). This suggests that H. pylori may evade immunity by impairing the clonal expansion capacity of CD8+ T cells.

Together, these results define differentiation trajectories of gastric CD8+ T cells and demonstrate H. pylori-driven suppression of their clonal expansion potential.

Interaction between HLA-DR+CTLA4+ T cells and macrophages via the CTLA4/CD86 axis upon H. pylori infection

Re-clustering of CD4+ T cells identified 16 distinct subpopulations (Fig. 5a–c, and Supplementary Fig. 6a–c), including seven naïve clusters (Clusters 0, 6, 7, 9, 10, 13, 15), two follicular helper clusters (Tfh; Clusters 1, 12), two regulatory clusters (Treg; Clusters 5, 11), one type 1 helper cluster (Th1; Cluster 4), one Th2 cluster (Cluster 3), one Th17 cluster (Cluster 2), one tissue-resident memory cluster (TRM; Cluster 8), and one interferon-response cluster (Cluster 14). Cluster 14 exhibited elevated expression of IFIT1, IFIT3, STAT1, ISG15 and MX1, consistent with formerly described CD4+ TISG cells36. Naïve CD4+ T clusters displayed characteristic markers LEF1, TXK, TCF7, IL7R, SELL, CCR7 and MAL33. Tfh clusters were defined by strong expression of CXCR5, IL21, ICOS, PDCD1 and CXCL13. The Th1 cluster showed enrichment of TBX21 (T-bet), CXCR3, IFNG, CCR1 and CCR5. While the Th2 cluster was marked by GATA3, IL5, PTGDR2, CCR8 and IL17RB. Th17 identity was confirmed through CCR6, IL23R, RORC and RORA expression. The TRM cluster exhibited elevated CD69, ITGAE (CD103), IL2 and TGFB1. Treg clusters demonstrated canonical FOXP3, TGFB, IL2RA, ENTPD1 and CTLA4 expression.

a, b UMAP plots showing 16 subsets in CD4+ T cells derived from H. pylori-negative or -positive patients. a Each subcluster is color-coded according to cell type. b Cells from H. pylori-negative (Upper) or -positive (Down) patients are shown. c Boxplots showing the proportion of each CD4+ T cell subset in PBMC (Upper) or gastric tissue (Down) samples. Quantitative data are shown as Mean ± SD. P values are calculated using the two-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test, and are shown in the figure panels. d Heatmap indicating the expression (scaled mean expression) of selected gene sets in each CD4+ T cell subset, including naïve, resident, inhibitory, pre-dysfunction, cytotoxicity, co-stimulatory, and MHC-II-related gene signatures. Colored based on normalized expression levels. e Boxplot showing the fractions of CD4+HLA-DRA+CTLA4+ cells in the CD4-5-HLA-DR subset derived from NT (n = 11) or PT (n = 11) samples. The dot represents one value from individual participants. Boxplots centered at the median with hinges at 1st and 3rd quartiles and whiskers drawn from hinges to the lowest and highest points within 1.5 interquartile range. The p value is calculated using the two-tailed student’s unpaired t-test, and is shown in the figure panels. f Volcano plot showing DEGs of CD4-5-HLA-DR subset between NT and PT samples. P values are calculated by two-sided Wilcoxon’s rank-sum test and corrected using the Benjamini-Hochberg approach. Genes highlighted in purple have log2 fold change > 1.0 and p value < 0.05. g (Left) Clonotype diversity of CD4+ T cells in NT (n = 6) or PT (n = 11) samples measured by Gini-Simpson index. Samples (N5T, N7T, N8T, N9T and N10T) having fewer than 20 CD4+ T cells were excluded from analyzes. (Right) Clonal expansion is measured by the fraction of clonal T cells from stomach-enriched CD4+ T cell populations in NT (n = 11) or PT (n = 11) samples. The dot represents one value from individual participants. Boxplots centered at the median with hinges at 1st and 3rd quartiles and whiskers drawn from hinges to the lowest and highest points within 1.5 interquartile range. P values are calculated by two-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test (Left) or two-tailed student’s unpaired t-test (Right). h Bubble chart showing the interaction between macrophage and selected CD4+ or CD8+ T cell subsets, based on the L-R analysis. The scores are normalized expression levels, and the sizes of the bubbles indicate the significance of the interactions, calculated by CellPhoneDB. i Multiplexed immunofluorescence images showing the interaction between macrophages and CD4+ or CD8+ T cells that co-expressing HLA-DRA and CTLA4, based on the CTLA4/CD86 axis, using antibodies CD4, CD8, CD68, CD86, CTLA4, and HLA-DRA. Spatial distance between target cells is shown. Scale bars, 50 um. Data shown are representative images of six donors and one experiment. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001.

Intriguingly, similar to CD8-12-HLA-DR cells, Cluster 5 also exhibited robust co-expression of MHC-II genes (HLA-DRA, HLA-DQA1, HLA-DQB1), inhibitory markers (CTLA4, LAG3), and co-stimulatory genes (TNFRSF14, CD28) (Fig. 5d), leading to its designation as CD4-5-HLA-DR. This population was predominantly derived from gastric specimens and showed significantly higher enrichment in PT samples compared to NT samples (Fig. 5c, and Supplementary Fig. 6c). Notably, Cluster 5 displayed markedly higher TNFRSF9 expression relative to Cluster 11 (Fig. 5d), indicative of an activated Treg phenotype33. Subsequent quantification of CD4+HLA-DRA+CTLA4+ cells within this population revealed a pronounced increase in PT samples (Fig. 5e). Comparative DEG analysis further highlighted distinct functional signatures: NT samples showed significant enrichment of inflammatory mediators (S100A6, S100A10, S100A11, S110A9, IL1A), cytotoxic effector molecules (XCL1, XCL2, GZMB, PRF1, GNLY, GZMA), and tissue-residency markers (RUNX3, NR4A1). In contrast, PT samples were dominated by immunosuppressive markers (LAG3, CTLA4, TOX) and MHC-II components (HLA-DRA, HLA-DOB) (Fig. 5f). These findings suggest H. pylori infection attenuates cytotoxic potential and tissue-resident functionality while driving an inhibitory phenotype.

As discussed earlier, our data demonstrate constrained antigen presentation capacities in both peripheral and gastric APC populations following H. pylori infection, which might impair subsequent CD4+ T cell recruitment. To investigate this relationship, we calculated the correlations between the MHC-II scores and CD4+ T cell proportions across experimental groups. Consistent with our hypothesis, MHC-II scores showed positive correlations with CD4+ T cell percentages in both PP and PT samples (Supplementary Fig. 6d).

Analysis of TCR-seq data revealed increased clonotype diversity but reduced clonal expansion capacity in CD4+ T cells from PT samples compared to NT samples (Fig. 5g, and Supplementary Fig. 6e, Supplementary Data 3), mirroring the trend observed in CD8+ T cells. These findings support the conclusion that H. pylori infection impairs T cell clonal expansion.

We identified two T cell subsets predominantly enriched in PT samples: a CD4+ population (CD4-5-HLA-DR) and a CD8+ population (CD8-12-HLA-DR), both exhibiting strong expression of MHC-II-associated genes (HLA-DRA, HLA-DQA1, HLA-DQB1) and elevated CTLA4 expression. To validate these populations in the H. pylori-colonized human stomach, we enriched gastric immune cells from H. pylori-negative and H. pylori-positive patients prior to flow cytometry analysis. Consistent with our scRNA-seq data, the proportions of CD4+HLA-DRA+CTLA4+ and CD8A+HLA-DRA+CTLA4+ T cells were significantly increased in H. pylori-positive individuals compared to their H. pylori-negative counterparts (Supplementary Fig. 3f, 6f, g, Supplementary Table 4).

To investigate whether these HLA-DR+CTLA4+-expressing T cells might suppress anti-bacterial immunity, we subjected all T cells and myeloid clusters to ligand–receptor (L-R) analysis and identified selective crosstalk between HLA-DRhi T cells and macrophages through the CTLA4/CD86 axis in PT samples, but not in NT samples (Fig. 5h). Given CD86’s higher affinity for CTLA4 than for CD2839, these HLA-DRhiCTLA4+ T cells may attenuate the efficiency of antigen presentation by macrophages and subsequent T cell activation, similar to the interaction between malignant cells and DCs via CD274/CD80 and CTLA4/CD80 in early-relapse hepatocellular carcinoma40. Further multiplexed immunofluorescent staining verified that the CD68+CD86+ macrophages physically resided near the CD4+HLA-DRA+CTLA4+ and CD8+HLA-DRA+CTLA4+ T cells (Fig. 5i), corroborating their functional interaction.

In summary, these data demonstrate that H. pylori colonization compromises clonal expansion in both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Furthermore, CD68+ macrophages engage HLA-DRhi T cells through the CD86/CTLA4 axis, dampening macrophage antigen-presenting capacity and subsequent T cell activation—a mechanism that may facilitate bacterial persistence.

Discussion

As the most ubiquitous human pathogen, a hallmark of H. pylori is that it successfully and stealthily evades host immune defenses. However, our understanding of how H. pylori manipulates host innate and adaptive immunity to favor its own persistence remains limited. Using scRNA-seq technology, we systematically characterized the reprogrammed immunosuppressive ecosystem within the H. pylori-infected human stomach. We further performed additional in vitro and in vivo experiments to orthogonally validate the findings in the discovery cohort.

By dissecting immunosuppressive signatures, we revealed that both peripheral and mucosal-infiltrating APCs exhibit reduced antigen presentation capacities after H. pylori infection, consistent with current knowledge. For example, VacA was shown to negatively regulate DC maturation by restoring E2F1 expression, and to impair antigen presentation by inhibiting the export of MHC-II molecules to the DC surface12,41. Moreover, we revealed a transcriptional trajectory from monocyte precursors to tissue-resident C1QC+ macrophages upon H. pylori infection, reminiscent of cell transitions described in colon cancer31. This may represent a pattern of development from monocytes to tissue-resident macrophages that is conserved across different settings. In macrophages, compromised phagocytosis was identified post-infection, representing another mechanism by which H. pylori promotes its survival in the human stomach. Our results further revealed a significant increase in mast cell infiltration within H. pylori-infected gastric tissues, aligning with their established role as early responders in gastric inflammation42,43. Activated mast cells drive pathogenic cascades through TNF-α-mediated epithelial barrier disruption44, yet simultaneously orchestrate antimicrobial responses via CXCL8-dependent neutrophil recruitment and cathelicidin secretion45. This functional duality suggests mast cells operate at the crux of H. pylori clearance and immunopathology. However, whether H. pylori exploits mast cell-derived signaling pathways (e.g., histamine or cytokine cascades) to subvert host immunity and establish chronic persistence still remains to be investigated.

T cells are the major effector cells in immune responses to H. pylori5,46. Maximilian et al. recently reported that CD8+ T cells defend against H. pylori infection7. In this study, we observed generally impaired T cell responses during H. pylori infection, as evidenced by the restricted clonal expansion capacities of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Notably, we profiled a population of T cells with reduced cytotoxicity that was predominantly enriched in H. pylori-infected gastric samples and strongly expressed both MHC-II-related genes and inhibitory-related genes (e.g., CTLA4). A similar cell subset was recently identified in gastric adenocarcinoma samples37. By integrating pseudotemporal and TCR clonality information, we confirmed that this population could transdifferentiate into CD8-2-CXCR3 or CD8-4-ID2 T cells. T cell responsiveness is an important issue in vaccine design. To address the mechanisms that impair responsiveness, we performed L-R-based interaction analysis and detected crosstalk between macrophages and HLA-DRA+CTLA4+-expressing T cells and verified the physical proximity of these cell populations via multiplexed immunofluorescent staining. Thus, a reduction in CD86/CD28 interactions via competition between CTLA4 and CD86 would prevent functional T cell activation39; it thus may represent a potential immune evasion mechanism of H. pylori.

In conclusion, our study provides evidence for an immunosuppressive gastric ecosystem in response to H. pylori infection, typified by reduced antigen presentation capacities of APCs and restricted clonal expansion capacities among mucosal-infiltrating T cells. These findings may be essential for understanding how H. pylori persists via host immune system manipulation. Our data may help researchers develop novel therapeutic strategies to eliminate this highly prevalent and detrimental pathogen.

Methods

Antibodies and pharmacological agents

Primary antibodies we used for multiplexed immunofluorescence staining were anti-HLA-DR/DP/DQ (ThermoFisher scientific, MA1-80678), anti-CD86 (Abcam ab220188), anti-CD4 (Abcam, ab133616), anti-CD68 (ZSGB-bio, ZM-0060), anti-CTLA4 (Abcam, ab237712), anti-CD8 (ThermoFisher scientific, MA1-80231). Primary antibodies and reagents used for flow cytometry were Fixable Viability Stain 450 (FVS450) (BD, 562247), Zombie NIR™ Fixable Viability Kit (Biolegend, 423105), CD45-AF532 (Thermo Fisher, 58-0451-82), CD11b-PE-Cy7 (BD, 552850), CD172a-APC (Biolegend, 144013), Ly-6G -BV421 (Biolegend, 127627), I-A I-E-PerCP-Cy5.5 (BD, 562363), F4/80-BV605 (BD, 743281), CD11c-APC (Biolegend, 117309), Alexa Fluor 532 anti-human CD3 (eBioscience, 58-0038-42), PerCP/Cyanine5.5 anti-human CD4 (Biolegend, 300529), PE anti-human CD8 (Biolegend, 344705), APC anti-human CD152 (CTLA-4) (Biolegend, 349907), Brilliant Violet 605 anti-human HLA-DR (Biolegend, 307640), PE anti-human CD11c (Biolegend, 371503), Alexa Fluor 700 anti-human CD11b (Biolegend, 301355), Brilliant Violet 421 anti-human CD1c (Biolegend, 331525), FITC anti-human CD19 (Biolegend, 302205), Human TruStain FcX (Biolegend, 422301), and APC Mouse IgG1, κ Isotype Ctrl (FC) (Biolegend, 400121).

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethic Committee of Southern Medical University (NYSZYYEC20190017), and the Ethics Committee of SHSMU on Laboratory Animal Care (No. 2022-157). All patients provided written informed consent for collecting tissue and blood samples for research and publishing relevant clinical information. This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Study design

The study was carried out from September 2020 to Novermber 2024 by enrolling patients at the Department of Gastroenterology, Shenzhen Hospital, Southern Medical University (Guangdong, China). All recruited subjects should be recorded for their clinical baseline characteristics, including gender, BMI, the delta over baseline (DOB) value from 13C-urea breath test (C13-UBT), pathological and endoscopic diagnosis reports. The endoscopic performance of stomach tissues was determined by two experienced gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopists. To ensure individuals that were initially diagnosed with chronical gastritis, all enrolled participants should follow the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Patient inclusion criteria

-

1.

18 ≤ Age ≤ 35;

-

2.

H. pylori infection was diagnosed by the 13C-urea breath test (C13-UBT), upper endoscopy examination and bacterial culture. A delta over baseline (DOB) value > 4.4 combined with Kyoto classification score ≥ 2 and culture of H. pylori from gastric biopsies led to a definitive diagnosis of infection.

-

3.

H. pylori-negative donors were defined by DOB value < 1.0, Kyoto classification score = 0, and gastric biopsies culture not detecting H. pylori.

-

4.

Written informed consent obtained.

Exclusion criteria of H. pylori-positive patients

-

1.

Duodenogastric reflux disease.

-

2.

Autoimmune diseases.

-

3.

Diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, chronic hepatitis B.

-

4.

Pregnancy.

-

5.

Long-term administration of non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) such as aspirin, salicylic acid, and hormone.

-

6.

Chronic consumption of coffee, strong tea, tobacco, spicy food, or alcohol.

-

7.

Taken proton pump inhibitors (PPI) or antibiotics within one year.

-

8.

Taken first-line antibiotics for H. pylori treatment, including clarithromycin, metronidazole, or amoxicillin within three year.

-

9.

Diagnosed as gastrointestinal diseases other than gastritis within one year.

Exclusion criteria of H. pylori-negative patients

-

1.

Diagnosed as H. pylori positive.

-

2.

Pregnancy.

-

3.

Taken proton pump inhibitors (PPI) or antibiotics within one year.

-

4.

Taken first-line antibiotics for H. pylori treatment, including clarithromycin, metronidazole, or amoxicillin within three year.

-

5.

Have symptoms such as epigastric pain, abdominal distension, nausea, vomiting, belching or loss of appetite within one year.

Single-cell dissociation and separation

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated using Ficoll solution (Solarbio, P8610) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 2 ml of fresh peripheral blood collected prior to endoscopy examination in EDTA anti-coagulant tubes was diluted with equal volumes of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and subsequently layered onto separating medium. After centrifugation (650 g, 20 min), PBMCs remained at the lymphocyte interface were carefully transferred to a new tube and washes twice with PBS (650 g, 5 min), then resuspended in autoMACS Rinsing solution (Miltenyi Biotec, 130-091-222).

Fresh gastric biopsies were endoscopically acquired from H. pylori-positive (PT group) or -negative (NT group) mucosae or in either antrum or corpus, then washed with PBS and cut into approximately 1-mm3 pieces. Tissue digestion was performed in digestive enzyme mixture containing 2 ml pre-warmed RPMI-1640 (ThermoFisher scientific), 2 mg/ml dispase II (Solarbio, D6430), 1 mg/ml type IV collagenase (Solarbio, 17104019) and 2 mg/ml DNase I (Solarbio, D8070) for 30 min at 37 °C, then deactivated with Fetal bovine Serum (FBS, Gibco, 16140071). Digested tissues were gently triturated with a 20 ml syringe plunger on a 70 μm cell-strainer (BD, 352350) until uniform cell suspensions were obtained. The suspended cells were centrifuged at 400 g for 6 min at 4 °C, and washed with PBS. Cell pellets were re-suspended in autoMACS Rinsing solution.

Single living immune cells (CD45+) were obtained using human CD45 microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec, 130-045-801) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, single-cell pellets from PBMCs and gastric biopsies were resuspended in autoMACS Rinsing solution containing 0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 2 mM EDTA. 20 μl of CD45 Microbeads per 107 cells were added and incubated for 15 min at 4 °C. Cells were washed and centrifuged at 300 g for 10 min, then re-suspended in autoMACS Rinsing solution. CD45+ cells already magnetically labeled with microbeads were loaded onto a MACS Column, and enriched by a MACS Separator.

Single cell cDNA amplification, library construction and sequencing

Cellular suspensions were loaded on a 10× Genomics GemCode Single-cell instrument that generates single-cell Gel Bead-In-EMlusion (GEMs). Libraries were generated and sequenced from the cDNAs with Chromium Next GEM Single Cell 3’ Reagent Kits v3.1. Upon dissolution of the Gel Bead in a GEM, primers containing (i) an Illumina R1 sequence (read 1 sequencing primer), (ii) a 16 nt 10x Barcode, (iii) a 10 nt Unique Molecular Identifier (UMI), and (iv) a poly-dT primer sequence were released and mixed with cell lysate and Master Mix. Barcoded, full-length cDNAs were then reverse-transcribed from poly-adenylated mRNA. Silane magnetic beads were used to remove leftover biochemical reagents and primers from the post GEM reaction mixture. Full-length, barcoded cDNAs were then amplified by PCR to generate sufficient mass for library construction. R1 (read 1 primer sequence) were added to the molecules during GEM incubation. P5, P7, a sample index, and R2 (read 2 primer sequence) were added during library construction via End Repair, A- tailing, Adapter Ligation, and PCR. The final libraries contained the P5 and P7 primers used in Illumina bridge amplification. The Single Cell 3’ Protocol produced Illumina-ready sequencing libraries. A Single Cell 3’ Library comprised standard Illumina paired-end constructs which begin and end with P5 and P7. The Single Cell 3’ 16 bp 10x Barcode and 10 bp UMI were encoded in Read 1, while Read 2 was used to sequence the cDNA fragment. Sample index sequences were incorporated as the i7 index read. Read 1 and Read 2 were standard Illumina sequencing primer sites used in paired-end sequencing.

Preprocessing of single cell RNA-seq data

10× Genomics Cell Ranger software (version 3.1.0) was used to convert raw BCL files to FASTQ files, alignment and counts quantification. Briefly, reads with low-quality barcodes and UMIs were filtered out and then mapped to the reference genome. Reads uniquely mapped to the transcriptome and intersecting an exon at least 50% were considered for UMI counting. Before quantification, the UMI sequences would be corrected for sequencing errors, and valid barcodes were identified based on the EmptyDrops method47. The cell by gene matrices were produced via UMI counting and cell barcodes calling.

Cell clustering

The cell by gene matrices for each sample were individually imported to Seurat version 3.1.1 for downstream analysis48. Cells with unusually high number of UMIs (≥8000) or mitochondrial gene percent (≥ 10%) were filtered out. We also excluded cells with less than 500 or more than 4000 genes detected. After removing unwanted cells from the dataset, we employed a global-scaling normalization method “LogNormalize” that normalizes the gene expression measurements for each cell by the total expression, multiplies this by a scale factor (10,000 by default), and log-transforms the results. The formula is shown as follows:

To minimize the effects of batch effect and behavioral conditions on clustering, we used Seurat, which utilized canonical correlation analysis and mutual nearest neighbor analysis, to aggregate all samples49. 2000 highly variable genes were selected in each sample based on a variance stabilizing transformation. Anchors between individual data were identified and correction vectors were calculated to generate an integrated expression matrix, which was used for subsequent clustering. Integrated expression matrix is then scaled and performed on principal component analysis for dimensional reduction. Then we implemented a resampling test inspired by the jackStraw procedure. We randomly permuted a subset of the data (1% by default) and rerun PCA, constructing a ‘null distribution’ of gene scores, and repeated this procedure. We identified ‘significant’ PCs as those who have a strong enrichment of low p-value genes for downstream clustering and dimensional reduction50. Seurat implements a graph-based clustering approach. Distances between the cells were calculated based on previously identified PCs. Briefly, Seurat embed cells in a shared-nearest neighbor (SNN) graph, with edges drawn between cells via similar gene expression patterns. To partition this graph into highly interconnected quasi-cliques or communities, we first constructed the SNN graph based on the Euclidean distance in PCA space and refined the edge weights between any two cells based on the shared overlap in their local neighborhoods (Jaccard distance). We then applied modularity optimization techniques – SLM51, to iteratively group cells together, with the goal of optimizing the standard modularity function. For visualization of clusters, Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) were generated using the same PCs52.

TCR analysis

Cell Ranger was used to assemble, quantify, and annotate paired V(D)J transcript sequences for each T cells. Firstly, non-productive, and incomplete length TCR chains were excluded. All single T cells with at least one productive TCRα or β chains were kept for subsequent analysis. Those cells with more than one productive TCRα or β chains would be further filtered. For example, if one single T cell owned two productive TCRα chains at the same time, we would compare their UMIs and discard the lower-expressed one. T cells shared identical paired TCRα and β chains were classified into the same clonotype. Besides, those cells with only one productive TCRα or β chain were merged into clonotypes in which owned complete paired chains and they must share at least one TCR chain with the paired one. The TCR sequencing data of all samples were then combined with the results of 10× single-cell RNA sequencing, we can therefore process the analyzes of cell phenotypes and their TCR clonotypes. T cells that shared the same TCR clones with more than one T cell in the same patient were defined as clonal T cells, and their increase was indicative of clonal expansion.

Doublet removal

Doublet removal was achieved by using the tool DoubletFinder (v2.0.3) by the generation of artificial doublets, using the PC distance to find each cell’s proportion of artificial k nearest neighbors (pANN) and ranking them according to the expected number of doublets53.

Differentially expressed genes analysis

Expression value of each gene in given cluster were compared against the rest of cells using Wilcoxon rank sum test54. Significant upregulated genes were identified using a number of criteria. First, genes had to be at least 1.28-fold overexpressed in the target cluster. Second, genes had to be expressed in more than 25% of the cells belonging to the target cluster. Third, p value is less than 0.05.

Gene set variation analysis (GSVA)

We performed Gene Set Variation Analysis (GSVA) using a collection of gene sets from MsigDB to identify pathways and cellular processes enriched in different clusters55. GSVA was performed as implemented in the GSVA R package version 1.26 based on the cluster-averaged log-transformed expression matrix56.

RNA velocity analyzes

The RNA velocity analysis was performed using the package velocyto with the default parameter, and the BAM files were used as inputs. For visualization, velocity vectors were plotted as locally average vector fields on the tSNE embeddings of our high-quality cells from the previous step57.

Ro/e analysis

Tissue preference for each cluster was quantified using the Ro/e analysis. The expected cell numbers for each combination of cell clusters and tissues were obtained from the chi-square test. One cluster was identified as being enriched in a specific tissue if Ro/e > 1.

SCENIC analysis

To carry out transcription factor network inference, analysis was performed on the SCENIC R package58. In brief, log-normalized expression matrix generated using Seurat was used as input, and the pipeline was implanted in three steps. First, we identified gene co-expression network via GENIE3. Second, we pruned each module based on a regulatory motif near a transcription start site via RcisTarget. Precisely, networks were retained if the TF-binding motif was enriched among its targets, while target genes without direct TF-binding motifs were removed. The retained networks were called regulons. Third, we scored the activity of each regulon for each single cell via the AUC scores using AUCell R package.

Bacterial and cell culture

The H. pylori strain PMSS1, TN2GF4 and NCTC 11637 strains were obtained from the Department of Microbiology, the Chinese University of Hong Kong. H. pylori was initially grown on horse blood agar plates (Columbia Blood Agar Base with DENT Selective Supplements; Oxoid, SR0147) in an anaerobic jar with a microaerophilic environment for 5 days at 37 °C. Murine dendritic cell line DC2.4 (Millipore, SCC142) was cultured in RPMI-1640 (GibcoTM, Thermo Fisher, 23400021) supplemented with 10% FBS and 10 ng/mL murine GM-CSF at 37 °C in 5% CO2. THP-1 Cells (ATCC, TIB-202) were cultured in RPMI-1640 (GibcoTM, Thermo Fisher, 23400021) supplemented with 10% FBS at 37 °C in 5% CO2.

Murine bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDM) preparation and culture

C57BL/6 J mice were purchased from Shanghai Model Organisms (Shanghai, China). Mice were housed under 12-h light/dark cycles in a specific pathogen-free/SPF room with clean bedding and free access to food and water, and temperature and humidity were kept at 22–26 °C, 55% ± 5%. Cage and bedding changes were performed each week. Eight- to ten-week-old C57/BL6J mice (regardless of gender) were used to generate (BMDM) according to standard procedures59. Mice were killed under anesthesia and soaked with 70% ethanol. Holding the foot with a forceps, remove the skin and muscles from the legs down to the hip bone. Isolate the tibia and femur by dislocating them from the hip, and then isolate the hip bone by holding it by the femoral cavity and cutting just beneath. Remove any tissue from the bones. Separate the femur from the tibia by dislocating and cutting through the knee joint, and the tibia from the foot by cutting just below the ankle joint. Cut the epiphyses of the bones and flush the marrow into a 50 mL centrifuge tube using a 5 mL syringe and a 23 G needle. Use 5 mL PBS per bone. Filter the cell suspension with a 70 μm cell strainer in a new 50 mL tube. Centrifuge at 250 × g and 4 °C for 5 min. Discard the supernatant and resuspend the cell pellet in 3 mL of BMDM medium. Count the cells under a microscope. Bone marrow cells were cultured in high glucose DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 20% L929-cell conditioned medium, and 100 U/mL penicillin-streptomycin for 7–10 days at 37 °C with 5% CO2.

Murine H. pylori infection

H. pylori were grown in brain heart infusion (BHI; Oxoid, CM1135) broth supplemented with 15% FBS for 20–30 h at 37 °C under microaerobic conditions and saturated humidity, with shaking at 200 rpm. Six- to seven-week-old C57BL/6 J mice were orally gavaged with 2 × 108 CFUs of H. pylori PMSS1 or sterile BHI broth (as a control) using gastric intubation on alternate days for a total of 3 doses. BHI or H. pylori-treated mice were maintained separately in different cages. At the end of the study, mice were sacrificed under anesthesia.

Flow cytometry

For live/dead-discrimination, BD Horizon Fixable Viability Stain 450 (FVS450, BD, 562247) or Zombie NIR Fixable Viability Kit (Biolegend, 423105) were used to stain cells for 12 mins at RT in the dark. Cells were washed with FACS buffer (PBS + 0.5% BSA) and then stained with panels of fluorophore-conjugated antibodies for 30 minutes at 4 °C. After washing, cells were resuspended in FACS buffer and analyzed using a 3-laser Sony SA3800 Spectral Analyzer. All antibodies and reagents used for FACS staining are listed in Supplementary Table 5.

Multiplexed immunofluorescence staining

Multiplex staining of FFPE samples were performed using the Leica BOND RX platform according to the manufacture’s instruction. The primary antibodies for the validation of T cells interacting with macrophage, including HLA-DR/DP/DQ (ThermoFisher, MA1-80678, 1:800), CD86 (Abcam, ab220188, 1:800), CD4 (Abcam, ab133616, 1:400), CD68 (ZSGB-bio, ZM-0060, 1:100), CTLA4 (Abcam, ab237712, 1:250), CD8 (ThermoFisher, MA1-80231, 1:100) were sequentially applied. Then, slides were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody. DAPI was used to stain nuclei after all antigens have been labeled. For each slides, ≥5 fields of immune cell enriched areas were selected for image capture. The selected areas were scanned by Vectra Polaris Automated Quantitative Pathology Imaging System (AKOYA) to obtain multispectral images. Spatial distance between target cells were measured by HALO-link platform. Distance <30 μm was considered as physical juxtaposition.

Statistics

All statistical analysis were performed using GraphPad Prism (version 9.0) or SPSS (version 27) software. All quantitative data were shown as means ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical tests used in figures were shown in figure legends and statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Exact value of n was shown in the figures, figure legends and source data. What n represents was shown in the figure legends.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The raw scRNA and TCR sequence data reported in this paper have been deposited in the Genome Sequence Archive (Genomics, Proteomics & Bioinformatics 2021) in National Genomics Data Center (Nucleic Acids Res 2022), China National Center for Bioinformation / Beijing Institute of Genomics, Chinese Academy of Sciences (GSA-Human: HRA004050) [https://bigd.big.ac.cn/gsa-human/browse/HRA004050]. All data are included in the Supplementary Information or available from the authors, as are unique reagents used in this Article. The raw numbers for charts and graphs are available in the Source Data file whenever possible. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The source code employed for data processing and analysis in this study is available in Supplementary Software 1.

References

Malfertheiner, P. et al. Helicobacter pylori infection. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 9, 19 (2023).

Correa, P. A human model of gastric carcinogenesis. Cancer Res 48, 3554–3560 (1988).

Tacconelli, E. et al. Discovery, research, and development of new antibiotics: the WHO priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and tuberculosis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 18, 318–327 (2018).

Sugano, K. et al. Kyoto global consensus report on Helicobacter pylori gastritis. Gut 64, 1353–1367 (2015).

Jafarzadeh, A., Larussa, T., Nemati, M. & Jalapour, S. T cell subsets play an important role in the determination of the clinical outcome of Helicobacter pylori infection. Micro. Pathog. 116, 227–236 (2018).

Larussa, T., Leone, I., Suraci, E., Imeneo, M. & Luzza, F. Helicobacter pylori and T helper cells: mechanisms of immune escape and tolerance. J. Immunol. Res. 2015, 981328 (2015).

Koch, M. R. A. et al. CagA-specific gastric CD8(+) tissue-resident T cells control Helicobacter pylori during the early infection phase. Gastroenterology 164, 550–566 (2023).

Salama, N. R., Hartung, M. L. & Muller, A. Life in the human stomach: persistence strategies of the bacterial pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nat. Rev. Microbiol 11, 385–399 (2013).

Stead, C. M., Beasley, A., Cotter, R. J. & Trent, M. S. Deciphering the unusual acylation pattern of Helicobacter pylori lipid A. J. Bacteriol. 190, 7012–7021 (2008).

Gewirtz, A. T. et al. Helicobacter pylori flagellin evades toll-like receptor 5-mediated innate immunity. J. Infect. Dis. 189, 1914–1920 (2004).

Teymournejad, O., Mobarez, A. M., Hassan, Z. M., Moazzeni, S. M. & Ahmadabad, H. N. In vitro suppression of dendritic cells by Helicobacter pylori OipA. Helicobacter 19, 136–143 (2014).

Kim, J. M. et al. Stimulation of dendritic cells with Helicobacter pylori vacuolating cytotoxin negatively regulates their maturation via the restoration of E2F1. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 166, 34–45 (2011).

Zhang, L. et al. Reduced lysosomal clearance of autophagosomes promotes survival and colonization of Helicobacter pylori. J. Pathol. 244, 432–444 (2018).

Hu W. et al. Vitamin D3 activates the autolysosomal degradation function against Helicobacter pylori through the PDIA3 receptor in gastric epithelial cells. Autophagy, 4, 707–725 (2019).

Papalexi, E. & Satija, R. Single-cell RNA sequencing to explore immune cell heterogeneity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 18, 35–45 (2018).

Tietscher, S. et al. A comprehensive single-cell map of T cell exhaustion-associated immune environments in human breast cancer. Nat. Commun. 14, 98 (2023).

Cheng, S. et al. A pan-cancer single-cell transcriptional atlas of tumor infiltrating myeloid cells. Cell 184, 792–809.e723 (2021).

Ren, X. et al. COVID-19 immune features revealed by a large-scale single-cell transcriptome atlas. Cell 184, 5838 (2021).

Villani A. C. et al. Single-cell RNA-seq reveals new types of human blood dendritic cells, monocytes, and progenitors. Science 356, (2017).

Schaller, T. H., Batich, K. A., Suryadevara, C. M., Desai, R. & Sampson, J. H. Chemokines as adjuvants for immunotherapy: implications for immune activation with CCL3. Expert Rev. Clin. Immunol. 13, 1049–1060 (2017).

Swanson, K. V., Deng, M. & Ting, J. P. The NLRP3 inflammasome: molecular activation and regulation to therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 19, 477–489 (2019).

Belyaeva, V. et al. Fos regulates macrophage infiltration against surrounding tissue resistance by a cortical actin-based mechanism in Drosophila. PLoS Biol. 20, e3001494 (2022).

Fontana, M. F. et al. JUNB is a key transcriptional modulator of macrophage activation. J. Immunol. 194, 177–186 (2015).

Suzuki, E. et al. The transcription factor Fli-1 regulates monocyte, macrophage and dendritic cell development in mice. Immunology 139, 318–327 (2013).

Zhao, H. et al. KSRP specifies monocytic and granulocytic differentiation through regulating miR-129 biogenesis and RUNX1 expression. Nat. Commun. 8, 1428 (2017).

Pishesha, N., Harmand, T. J. & Ploegh, H. L. A guide to antigen processing and presentation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 22, 751–764 (2022).

Lu, L. et al. Utilizing murine dendritic cell line DC2.4 to evaluate the immunogenicity of subunit vaccines in vitro. Front Immunol. 15, 1298721 (2024).

Orsenigo, F. et al. Unifying considerations and evidence of macrophage activation mosaicism through human CSF1R and M1/M2 genes. Cell Rep. 43, 114352 (2024).

AG, N. et al. Phagocytosis imprints heterogeneity in tissue-resident macrophages. J. Exp. Med. 214, 1281–1296 (2017).

Ma, R. Y., Black, A. & Qian, B. Z. Macrophage diversity in cancer revisited in the era of single-cell omics. Trends Immunol. 43, 546–563 (2022).

Zhang, L. et al. Single-cell analyses inform mechanisms of myeloid-targeted therapies in colon cancer. Cell 181, 442–459.e429 (2020).

Hao, D. et al. The single-cell immunogenomic landscape of B and plasma cells in early-stage lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer Discov. 12, 2626–2645 (2022).

Zheng, L. et al. Pan-cancer single-cell landscape of tumor-infiltrating T cells. Science 374, abe6474 (2021).

van der Leun, A. M., Thommen, D. S. & Schumacher, T. N. CD8(+) T cell states in human cancer: insights from single-cell analysis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 20, 218–232 (2020).

Zheng, C. et al. Landscape of Infiltrating T cells in liver cancer revealed by single-cell sequencing. Cell 169, 1342–1356. e1316 (2017).

Chu, Y. et al. Pan-cancer T cell atlas links a cellular stress response state to immunotherapy resistance. Nat. Med. 29, 1550–1562 (2023).

Wang R., et al. Evolution of immune and stromal cell states and ecotypes during gastric adenocarcinoma progression. Cancer Cell, 41, 1407–1426 (2023).

Corcoran, M. et al. Archaic humans have contributed to large-scale variation in modern human T cell receptor genes. Immunity 56, 635–652.e636 (2023).

Schildberg, F. A., Klein, S. R., Freeman, G. J. & Sharpe, A. H. Coinhibitory Pathways in the B7-CD28 Ligand-Receptor Family. Immunity 44, 955–972 (2016).

Sun, Y. et al. Single-cell landscape of the ecosystem in early-relapse hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell 184, 404–421.e416 (2021).

Wang, Y. H., Gorvel, J. P., Chu, Y. T., Wu, J. J. & Lei, H. Y. Helicobacter pylori impairs murine dendritic cell responses to infection. PLoS One 5, e10844 (2010).

Mysorekar, V. V., Dandekar, C. P. & Prakash, B. S. Mast cells in Helicobacter pylori associated antral gastritis. Indian J. Pathol. Microbiol 46, 605–609 (2003).

Nakajima, S., Bamba, N. & Hattori, T. Histological aspects and role of mast cells in Helicobacter pylori-infected gastritis. Aliment Pharm. Ther. 20, 165–170 (2004).

Lv, Y. P. et al. Helicobacter pylori-induced IL-33 modulates mast cell responses, benefits bacterial growth, and contributes to gastritis. Cell Death Dis. 9, 457 (2018).

Elieh Ali Komi, D. & Kuebler, W. M. Significance of mast cell formed extracellular traps in microbial defense. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 62, 160–179 (2022).

Velin, D., Straubinger, K. & Gerhard, M. Inflammation, immunity, and vaccines for Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter 21, 26–29 (2016).

Lun, A. T. L. et al. EmptyDrops: distinguishing cells from empty droplets in droplet-based single-cell RNA sequencing data. Genome Biol. 20, 63 (2019).

Butler, A., Hoffman, P., Smibert, P., Papalexi, E. & Satija, R. Integrating single-cell transcriptomic data across different conditions, technologies, and species. Nat. Biotechnol. 36, 411–420 (2018).

Stuart, T. et al. Comprehensive integration of single-cell data. Cell 177, 1888–1902.e1821 (2019).

Chung, N. C. & Storey, J. D. Statistical significance of variables driving systematic variation in high-dimensional data. Bioinformatics 31, 545–554 (2015).