Abstract

Nature uses bottom-up self-assembly to build structures with remarkable complexity and functionality. Understanding how molecular-scale interactions translate to macroscopic properties remains a major challenge and requires systems that effectively bridge these two scales. Here, we generate DNA and RNA-based liquids with exquisite programmability in their macroscopic rheological properties. In the presence of multivalent cations, nucleic acids can condense to a liquid-like state. Within these liquids, DNA and RNA retain sequence-specific hybridization abilities. We show that sequence-specific inter-molecular hybridization in the condensed phase cross-links molecules and slows down chain dynamics. This reduced chain mobility is mirrored in the macroscopic properties of the condensates. Molecular diffusivity and material viscosity scale with the inter-molecular hybridization energy, enabling precise sequence-based modulation of condensate properties over several orders of magnitude. Our work offers a robust platform to create bottom-up programmable fluids and may help advance our understanding of liquid-like compartments in cells.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The sequence-specific binding properties of nucleic acids form the basis for life, providing the chemical foundation for the replication of genetic material, its decoding by the ribosome, and for molecular targeting such as by guiding RNA processing1. This sequence-specificity of DNA bonding has also been harnessed to generate a variety of self-assembling programmable materials2. These include nanometer-scale structures with precise control of DNA topology such as in DNA origami3,4 to mesoscale soft materials such as hydrogels5,6. DNA and RNA nanostructures with reversible interaction sites have also been used to create liquid-like materials that exhibit dynamic and tunable properties, opening up applications in biotechnology and providing synthetic models for biomolecular condensates in cells7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15. In most of these applications, the negative charge on the phosphodiester backbone is neutralized by low valence counterions, and the desired molecular arrangement is achieved exclusively by utilizing the sequence-programmability of DNA and RNA bonding.

In the cellular environment, however, DNA and RNA interact with multivalent cations such as polyamines16 and positively charged proteins17. When solutions of oppositely charged polymers are mixed, they can undergo associative phase separation, called complex coacervation, which results in a polymer-rich phase and a dilute supernatant phase18,19,20 DNA and RNA readily undergo complex coacervation in the presence of cationic polymers21,22, and this process may have parallels in the origin of life scenarios23,24. Electrostatic interaction-mediated complexation is also the dominant approach used to assemble nucleic acids for delivering foreign genetic material to cells25,26. Many cellular condensates, such as nucleoli and stress granules, contain RNA, and complex coacervation of RNA with proteins contributes to the formation of these bodies27,28,29. Single- and double-stranded nucleic acids form coacervates with distinct biophysical properties, suggesting that nucleic acid structure and flexibility influence coacervate behavior30,31,32. Moreover, our previous work indicated that single-stranded nucleic acids in complex coacervates can participate in inter-molecular base-pairing interactions33. This interplay of base-pairing and charge-mediated interactions likely plays a role in cellular condensates34,35 but it remains largely uncharacterized.

Given the ability of DNA and RNA to form intermolecular base-pairing within complex coacervates, we hypothesized that it may allow us to create programmable DNA- and RNA-based materials. We were inspired by self-associative polymers that are designed to exhibit reversible associations between polymer chains36,37. These reversible inter-chain cross-links allow reconfiguration of the polymer network, and manifest properties that are not accessible to conventional polymer materials with static cross links, such as, self-healing and stimuli-responsive material transformation37. These macroscopic properties depend on the lifetime, densities, and positions of the cross-links between polymer chains38. Precise engineering of these features in synthetic polymers is difficult. The exquisite programmability of nucleic acid bonding could help overcome these challenges.

Here we use these insights to generate DNA and RNA liquids with precise control over their viscoelastic properties. We engineered DNA oligonucleotides with short hybridization patches interspersed by single stranded regions (Fig. 1). Polyvalent cations induce complex coacervation resulting in DNA-rich liquids. Within the condensed phase, the DNA concentration is above the overlap concentration facilitating inter-chain hybridization. Such inter-chain hybridizations transiently cross link DNA molecules and slow down their diffusion. DNA self-diffusion and viscosity of the condensed phase scale linearly with the life-time of DNA-DNA cross-links. By engineering the sequence, we can precisely program the hybridization energy and thus tune the properties of these liquids over several orders of magnitude. Similar rules apply to RNA coacervates and to condensates of nucleic acids with cationic peptides. This system may pave the way for a class of programmable nucleic acid-based materials. It may provide insights on the physics of polyelectrolyte complexation and may help uncover the rules underlying the formation of liquid-like RNA granules in the cell.

a Single stranded nucleic acids undergo associative phase separation in the presence of polyvalent cations and produce a polymer rich coacervate phase and a dilute supernatant phase. b Representative fluorescent micrographs (n = 5 independent experiments) showing complex coacervates of non-base pairing T-90 DNA in the presence of spermine. Scale bar, 30 µm. c We incorporated multiple weak hybridization patches in the DNA/RNA sequence. Inter-molecular hybridization at these sites transiently cross-links two or more strands and impedes their molecular mobility within coacervates. d Molecular diffusivity (Dself) and viscosity (η) of these coacervates depend on the lifetime of inter-molecular cross-links (τbond), and can be programmed by modulating the DNA/RNA sequence.

Results

Design of nucleic acids with self-associative patches

We used a 90-nucleotide long deoxythymidine (T-90) oligonucleotide as a chassis to build self-associative DNA (Fig. 1a, b, Supplementary Fig. 1a). T-90 does not form appreciable secondary structure at room temperature and provides a benign scaffold to engineer base-pairing sites. To incorporate associative sites, we replaced a subset of T-bases in T-90 with short palindromic interaction patches (Fig. 1c–d, Supplementary Table 1). These patches provide sites for intra- and inter-strand DNA hybridization while the total charge along the phosphodiester backbone is unchanged. The patch sequences were chosen such that the DNA transiently hybridize at room temperature (hybridization energy, ε = -ΔG/(kBTNA), between 0 and 20, where ΔG is the theoretical predicted free energy of hybridization from nearest neighbor calculations39, kB is the Boltzmann constant, T is the temperature and NA is the Avogadro constant, see Supplementary note 1 for additional notes on patch design). Successive patches were separated by ≥15 non-hybridizing T bases in order to minimize the cooperativity in hybridization between adjacent sites40,41. By changing the patch sequence or temperature, we can program the hybridization energy of the associative patch (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2) and varying the number of patches per DNA allows us to tune the hybridization valency. We refer to these self-associating single-stranded DNA oligonucleotides as patchyDNA drawing parallels to colloids with multiple interaction sites42.

As a polycation, we chose spermine, a cellular metabolite and a tetravalent cation at pH 7.0 (pKa for the four amine groups ≥7.9)43. Addition of spermine induced complex coacervation and produced two coexisting aqueous phases: a DNA-poor supernatant phase and a DNA-rich, condensed phase (Fig. 1b, Supplementary Fig. 1). A small amount (<1%) of fluorescently labeled DNA was doped to facilitate condensate visualization. The patchyDNA condensates exhibited liquid-like properties (Supplementary Fig. 1b–e): they were spherical, and upon contact, two or more droplets coalesced and relaxed to a spherical geometry (Supplementary Fig. 1e). Nearly 90% of DNA partitioned in the condensed phase (Supplementary Fig. 2), and DNA partitioning and coacervate yield was comparable for the various sequences examined (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Previous work has shown that the complex coacervate phase can be envisioned as a semi-dilute solution, i.e., within the condensed phase, the polymer concentration is comparable to the overlap concentration, making inter-chain interactions as or more likely as intra-chain interactions44,45,46. Consistent with this notion, the DNA concentration in the patchyDNA coacervates (Cdense ~ 1–10 mM, Supplementary Fig. 2) was comparable to the estimated overlap concentration (Coverlap, for a 90-mer ssDNA ~1 mM) (see Supplementary Note 2). We also used fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) to directly estimate the mean inter-molecular distance between DNA in the coacervate and dilute phases. We labeled patchyDNA with either a fluorescence donor (Cy3) or an acceptor (Cy5) dye (Supplementary Table 3). In the condensate, we observed substantial FRET between the two dyes (Supplementary Fig. 3), indicating that the distance between DNA molecules is comparable to the molecular length scales (Frster radius for Cy3 and Cy5 dye pair ≈ 5 nm47; radius of gyration for 90-mer ssDNA, ≈ 5 nm48). In contrast, no discernible FRET signal was observed in the solution phase indicating that the hybridization patches do not induce stable DNA dimerization (Supplementary Fig. 3).

As additional evidence for inter-molecular hybridization in the condensed phase, we examined the effect of base-pairing interactions on the phase stability. Complex coacervation is driven by a combination of attractive electrostatic interactions and entropically favorable molecular rearrangements. The loss in configurational entropy upon polyelectrolyte complexation is counterbalanced by the entropy gain upon the release of low-valence counter-ions that were bound to the polyelectrolytes18,19,49. High concentrations of low valence counter ions diminish the relative entropic gain upon polyelectrolyte complexation and inhibit complex coacervation49. Short-range intermolecular interactions such as hydrogen bonding and base stacking may stabilize complex coacervates against salt-mediated dissolution50. Consistent with this expectation, DNA-spermine coacervates were susceptible to NaCl mediated dissolution and the critical salt concentration for coacervate dissolution (C*) increased progressively with the patch hybridization energy (C* = 30 mM for ε = 0, 130 mM for ε = 20.2, Supplementary note 3, Supplementary Fig. 4). In summation, these results demonstrate that patchyDNA molecules are densely packed in complex coacervates which may potentiate intermolecular base-pairs.

Base-pairing modulates chain dynamics in patchyDNA condensates

Inter-molecular base-pairing would cross-link DNA strands and impede their mobility. To examine the effect of inter-strand cross-linking on chain dynamics, we used fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP). In these experiments, a small region of a DNA droplet is photobleached and the recovery is tracked over time (Fig. 2a, b). The fraction of fluorescence recovery reports on the proportion of DNA that is mobile within the droplet, while the recovery timescales reported on the molecular diffusivity. For the sequences examined (ε ≤ 20.2) (Fig. 2b), the patchyDNA coacervates exhibited near-complete (≥80%) fluorescence recovery upon partial photobleaching (Fig. 2b, c, Supplementary Fig. 5a), indicating that the DNA in the condensed phase is mobile. However, the characteristic fluorescence recovery time, τFRAP, progressively increased with ε, indicating that DNA mobility is reduced as the hybridization energy increases (Fig. 2b, c, Supplementary Fig. 5a, b). τFRAP can be used to estimate the apparent self-diffusion coefficient, Dself (see the FRAP section in “Methods”)51,52. Dself for the non-base-pairing T-90 was 0.32 ± 0.16 µm2/s (mean ± standard deviation, n = 16). As the hybridization energy of the patch was increased, Dself progressively decreased by nearly three orders of magnitude (Dself = (3.6 ± 1.3) × 10−4 µm2/s at ε = 20.2, mean ± standard deviation, n = 18, Supplementary Fig. 5c). Base-pairing is temperature sensitive, and besides changing the DNA sequence, ε can also be modulated by changing the temperature (Supplementary Table 2). For a given interaction patch, Dself could be modulated by nearly 5-fold as the temperature was increased from 20 °C to 45 °C (for patch sequence GGATCC, Dself = (2.6 ± 0. 3) × 10−3 µm2/s at 20 °C, ε = 16.1, versus (17 ± 2) × 10−3 µm2/s at 45 °C, ε = 10.8) (Fig. 2d, Supplementary Fig. 6). We did not observe any measurable change in Dself for T-90 in this temperature range (Supplementary Fig. 6a and 7).

a Schematic showing the design of self-associative patchyDNA. The patches are 2–8 nucleotide long palindromic sequences, and successive patches are separated by ≥15 T bases. b Kymographs (right) depicting fluorescence recovery upon partial photobleaching of patchyDNA condensates with the indicated patch sequences (left). ε is the patch hybridization energy at 22 °C. Inset: representative fluorescence micrographs and corresponding fluorescence time trace for DNA with the patch sequence GGATCC. The arrow indicates the point of photobleaching. c, d Fluorescence recovery time traces for patchyDNA condensates, where ε was changed either by varying the patch sequence (measurements conducted at 22 °C) (c) or by varying the temperature for a given sequence (d). Each data point in c and d denotes mean ± SD, n = 5 droplets. e Plot showing that logarithm of DNA self-diffusion coefficient (Dself) scales linearly with ε. The solid and open symbols in (e) denote that ε was varied by changing the patch sequence or by changing the temperature, respectively. Each data point denotes mean ± SD. Patch sequences and number of droplets analyzed (n) at 22 °C: T90 (n = 16), GC (n = 17), GTAC (n = 15), GAATTC (n = 20), GGCC (n = 19), GGATCC (n = 16), GGAATTCC (n = 18), and GGGCCC (n = 16). Temperature-dependent measurements for GGCC and GGATCC: GGCC—20 °C (n = 9), 25 °C (n = 5), 30 °C (n = 9), 35 °C (n = 10), 40 °C (n = 7), and 45 °C (n = 5); GGATCC—20°C (n = 7), 25°C (n = 9), 30 °C (n = 9), 35 °C (n = 10), 40 °C (n = 10), and 45 °C (n = 7). The dotted line is the least square fit between log (Dself) and ε (slope (mean ± SE) = −0.14 ± 0.01, R2 = 0.95). The color bars in (c, d, e) denote the range of ε. Scale bar in (b) is 5 µm. Error bars for some data points in e are smaller than the symbols, and thus not visible in the plot (see Supplementary Fig. 6c, d).

Interestingly, all of our Dself measurements across various patch sequences and temperatures, when plotted against ε, converged on a single line on the semi-log plot, indicating that Dself scales exponentially with ε (Fig. 2e). Similar scaling for Dself with ε was observed when we used oligo-lysine or oligo-arginine as polycations instead of spermine (Supplementary Fig. 8). This exponential scaling between Dself and ε is reminiscent of the dynamics of unentangled self-associative neutral polymers in the semi-dilute regime38,53. According to this model (referred to as the sticky Rouse model), associative polymers in a network diffuse by breaking inter-molecular cross-links on one site and re-forming at another38,54. Thus, polymer diffusion is inversely related to the lifetime of intermolecular cross-links, τbond53,54. The bond lifetime is determined by the interaction energy and is given by τbond ~ e−Ea/kBT, where Ea is the association energy, and kBT is the normalization for thermal energy. While we do not know the exact solvent environment in the condensed phase, these results indicate that the theoretically estimated hybridization energy provides a reasonable proxy for the relative association energy and demonstrate that DNA diffusion in the coacervate phase can be precisely programmed by engineering the hybridization patch sequence.

Inter-chain hybridization modulates material properties of DNA condensates

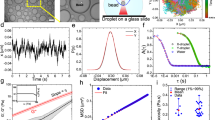

We next examined the viscoelastic properties of coacervates using particle tracking microrheology55. In these experiments, fluorescent microspheres are embedded in the material and their movement over time reports on the material’s viscoelastic behavior55,56. Beads trapped in the DNA coacervates exhibited random fluctuations that are effectively described by a Gaussian probability distribution (Fig. 3a, b, Supplementary Fig. 9). The mean squared displacement (MSD) of beads followed a power law relation with time (t), MSD ~ tα, with diffusion exponent α ≈ 1, across the various patch sequences examined (Fig. 3c–d). This linear relationship between bead MSD and time indicates that the patchyDNA coacervates behave like viscous fluids with minimal elastic behavior and aligns with our observations from fluorescence photobleaching experiments described above.

a Representative fluorescence micrograph (n = 5 independent experiments) showing passivated beads (radius = 50 nm) embedded in a patchyDNA coacervate (white circle). b Representative time trajectory of a single bead (left) and probability distribution of bead displacement at three different lag times (right) in T-90 coacervates at 22 °C. Distributions are well-described by a Gaussian function (solid lines). c Mean squared displacement (MSD) with lag time for beads embedded in T-90 coacervates at 22 °C. Gray lines show the data from individual beads. Mean values are depicted in yellow. Black solid line is provided as a guide for slope = 1. d MSD tracks of beads (mean) in T-90 (n = 7), GC (n = 5), GTAC (n = 6), and GGCC (n = 6) condensates at 22 °C. e Similar to (d) but for beads in GGCC condensates at various temperatures (n = 5 at each temperature). f Plot showing the logarithm of viscosity (η) versus ε. The solid and open symbols denote ε was varied by changing the patch sequence or by changing the temperature respectively. Each data point denotes mean ± SD. Patch sequences and corresponding n at 22 °C T-90 (n = 7), GC (n = 5), GTAC (n = 6), and GGCC (n = 6). Temperature-dependent measurements for GGCC and GGATCC: GGCC—25 °C (n = 6), 30 °C (n = 6), 35 °C (n = 6), 40 °C (n = 6), and 45 °C (n = 8); GGATCC—25 °C (n = 5), 30 °C (n = 6), 35 °C (n = 5), 40 °C (n = 6), and 45 °C (n = 6). The dotted line is a linear fit between log(η) and ε (slope (mean ± SE) = 0.22 ± 0.01, R2 = 0.88). The color bars in (d, e, f) denote the range of ε. Error bars for some data points in f are smaller than the symbols, and thus not visible in the plot (see Supplementary Fig. 11c, d).

The bead fluctuations can be used to calculate its diffusion coefficient, Dprobe, using the relationship, MSD ≈ 4·Dprobe t + NF, where NF is the noise floor (see the Single particle tracking section in “Methods”, Supplementary Fig. 10). Since these coacervates behave like viscous liquids and knowing the size of the bead, we can use Stokes-Einstein relation to estimate the material’s dynamic viscosity (η). η increased with ε, increasing from 0.56 ± 0.32 Pa.s (for T-90, ε = 0; mean ± standard deviation, n = 7) to 191 ± 97 Pa.s (for patch sequence GGCC, ε = 12.5; mean ± standard deviation, n = 6). Likewise, for a given DNA sequence, η increased when ε was increased by varying the temperature (Fig. 3e, Supplementary Fig. 11). Similar to our observations with Dself, η scaled exponentially with ε (Fig. 3f), indicating that the macroscopic properties of the condensates can be programmed by the DNA sequence. Similar dependence on ε was observed when we used patchyDNA with AT-rich interaction patches incorporated within a C-rich single stranded backbone (Supplementary Table 4 and Supplementary Fig. 12). We limited our microrheology experiments to DNA with ε ≈ 15 as beyond this regime, the bead diffusion approached the measurement noise floor (Supplementary Fig. 10).

When two liquid droplets fuse, interfacial tension drives them to minimize the surface area by relaxing to a spherical shape, while viscosity opposes this relaxation. For droplets of a viscous fluid suspended in a lower viscosity medium, the timescales of fusion (τfusion) are proportional to the droplet viscosity (η) and its size (l), and inversely proportional to the interfacial tension (γ)57,58. Consistent with their liquid-like behavior, patchyDNA droplets fused with one another (Fig. 4a). For a given patchyDNA sequence, τfusion increased linearly with the droplet size, l, and the slope of this line provided an estimate of the ratio, η/γ, also knowns as the inverse capillary velocity (Fig. 4b–d and Supplementary Fig. 13a). We estimated η/γ for the various patchyDNA sequences by examining multiple coalescence events across a range of droplet sizes and found that η/γ increased by 6 orders of magnitude as ε was varied from 0 to 20.2 (Fig. 4e). The droplet coalescence rates, in conjunction with direct viscosity measurements, allowed us to estimate the droplet interfacial tension. Interfacial tension for patchyDNA coacervates was between 400 and 1200 µN/m, about two orders of magnitude smaller than that for air-water interface at 22 °C (≈70 mN/m)59 (Supplementary Fig. 13b). This ultra-low interfacial tension is comparable to that for condensates of other polymers of similar molecular dimensions60,61. Within the constraints of our experiments, γ did not appreciably change with ε (Supplementary Fig. 13b), aligning with recent findings that polymer chains at interfaces tend to favor intra-chain interactions46. The fusion experiments allowed us to extract η/γ for a larger spectrum of patchyDNA, and in conjunction with our observation that γ exhibits a weak dependence on ε, these results indicate that η scales exponentially with ε, and can be modulated over 6 orders of magnitude as ε varies from 0 to 20.2 (η/γ ≈ 5.2 × 10−4 s-µm−1 for ε = 0, ≈3 × 102 s-µm−1 for ε = 20.2).

a Representative fluorescence micrographs showing fusion between complex coacervates of patchyDNA with the indicated ε and spermine at 22 °C. Fusion rates are slower for DNA with higher ε. Scale bar, 10 µm. b The characteristic fusion time (τfusion) can be obtained from fitting single exponential (dotted line) to the aspect ratio of the fusing droplets of roughly similar size. The plot in (b) corresponds to ε = 15.7 in (a). c τfusion linearly increased with the droplet size (l). Representative data from patchyDNA condensates with patch sequence GGATCC, ε = 15.7. Each data point (mean ± 95% CI) denotes independent fusion events. d τfusion for various patchyDNA coacervates increases linearly (solid lines) with l. Each data point (mean ± 95% CI) denotes independent fusion events. e Plot showing that the logarithm of inverse capillary velocity (η/γ) scales linearly with ε (dotted line, slope (mean ± SE) = 0.28 ± 0.02, R2 = 0.92). Each data point denotes mean ± 95% CI. The color bars in d and e show the range of ε. Error bars in e are smaller than the symbols, and thus not visible in the plot.

To further substantiate that the observed scaling results from hybridization-based inter-strand cross-links, we modulated the patch valency. DNA strands with three or more patches can form cross-linked networks, whereas those with two or fewer patches are not expected to do so. Consistent with this model, for a given patch sequence, coacervates formed using DNA with one or two patches exhibited properties comparable to those of T-90 (Supplementary Table 5, Supplementary Figs. 14 and 15). In contrast, increasing the number of patches to three resulted in a significant increase in condensate viscosity (Supplementary Fig. 14). Furthermore, sequences with only two patches did not show measurable changes in rheological properties as the patch hybridization energy (ε) was varied, while those with three patches exhibited scaling behavior similar to that observed with four-patch sequences (Supplementary Fig. 15). Altogether, our data demonstrate that patchyDNA with three or more interaction patches can form hybridization-based networks in the condensed phase. By programming the sequence of the DNA patch, we can tune the lifetime of the DNA-DNA cross-link, and this interchain interaction is reflected in both the molecular diffusion of the DNA and the macroscopic properties of the resulting condensed phase.

Heterotypic interactions enable design of stimuli-responsive condensates

The DNA in the condensates can also be potentially cross-linked via heterotypic interactions. Such heterotypic associations could allow one to tune the coacervate properties in response to a trigger strand that potentiates inter-molecular cross-linking (Fig. 5a, Supplementary Fig. 16a). As a proof of concept, we designed two sets of patchyDNAs: a primary strand and an actuator secondary strand (Supplementary Tables 6, 7 and Fig. 5a). The patches on these DNAs individually do not canonically self-associate, but they can hybridize to each other (Fig. 5a, b and Supplementary Fig. 16). The coacervates produced from the primary strand alone (patch sequence, CTCCTC) exhibited dynamics and material properties similar to those from T-90 DNA, as expected (Supplementary Fig. 16b). Upon addition of the cross-linking secondary DNA (patch sequence, GAGGAG), the self-diffusivity of the primary strand diminished (Supplementary Fig. 16c). The apparent self-diffusion coefficient, Dself, was lowest when the two strands were mixed at equimolar ratio and increased when either strand was in excess (Supplementary Fig. 16c).

a Schematic showing design of a primary patchyDNA with inducible inter-molecular cross-linking. The primary strand forms complex coacervates with spermine but this sequence does not contain self-associative hybridization sites (left). Addition of an appropriate secondary patchyDNA strand may cross-link the two DNAs (right). b Estimated hybridization energy for heterotypic cross-links (εheterotypic) with the indicated secondary patch sequence. Patch sequence for primary strand is CTCCTC. c, d Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching for the primary patchyDNA and f, g MSD of embedded beads with lag time, where εheterotypic was modulated either by varying the secondary patchyDNA (c, f) or by varying the temperature for the indicated secondary patchyDNA (d, g). Data depict mean ± SD, n = 5 and mean, n = 5 for (c, d) and (f, g), respectively. Plots showing that the logarithm of self-diffusivity (Dself) (e) and viscosity (η) (h) of the primary patchyDNA scales linearly with εheterotypic. Dotted line denotes the least square fit (slope (mean ± SE) = −0.34 ± 0.01, R2 = 0.92 and 0.33 ± 0.02, R2 = 0.83, for e and h respectively). The solid and open symbols indicate that εheterotypic was varied by changing the secondary patchyDNA or by changing the temperature, respectively. Each data point denotes mean ± SD. The number of technical replicates (n) for e, at 22 °C for CTCCTC + GG (n = 8), CTCCTC + AGGA (n = 8), CTCCTC + GAGG (n = 10), CTCCTC + GAGGAG (n = 9) and for CTCCTC + GAGGAG at various temperatures 25 °C (n = 5), 30 °C (n = 5), 35 °C (n = 6), 40 °C (n = 5), and 45 °C (n = 5). For h: at 22 °C for CTCCTC + GG (n = 5), CTCCTC + AGGA (n = 5), CTCCTC + GAGG (n = 6), CTCCTC + GAGGAG (n = 8) and for CTCCTC + GAGGAG at various temperatures 25 °C (n = 8), 30 °C (n = 8), 35 °C (n = 7), 40 °C (n = 9), and 45 °C (n = 9). The color bars in (c, d, f, g) indicate the range of εheterotypic. Error bars for some data points in (e) are smaller than the symbols, and thus not visible in the plots (see Supplementary Fig. 16e, f).

This ability to harness heterotypic interactions allowed us to tune the properties of the coacervates produced from the same primary patchyDNA but in response to distinct cross-linking secondary DNAs as triggers. We examined four distinct secondary sequences that could each hybridize with the same primary patchyDNA but with different hybridization energies (Fig. 5b). Similar to our observations with self-associative patches, both Dself and η scaled exponentially with the inter-molecular hybridization energy, εheterotypic, when the two strands were mixed at stoichiometric ratios (Fig. 5c–h, Supplementary Fig 16e, f). These results, in conjunction with the findings from previous sections, reinforce that the material properties of DNA complex coacervates can be predictably tuned by modulating hybridization-based cross-links, including in response to an external input.

Inter-molecular hybridization modulates the material properties of RNA-peptide condensates

Eukaryotic cells are compartmentalized by numerous RNA-containing condensates such as nucleoli, nuclear speckles, and stress granules, that exhibit liquid-like properties27,62. The protein constituents of these condensates often contain charged disordered domains63. In vitro, many of these proteins forms condensates in the presence of RNA28,64. The choice of RNA sequence affects condensate properties51,65 but the role of RNA-RNA interactions in these bodies remains poorly characterized66. Equipped with our biophysical framework, we examined how inter-molecular RNA-RNA hybridization affects the properties of RNA condensates produced with cationic peptides.

We used a 60-nucleotide long polyU (rU-60) RNA and incorporated 4 associative patches that are expected to reversibly hybridize at room temperature (Supplementary Tables 8, 9 and Fig. 6a). rU-60 does not form appreciable secondary structure at or above room temperature (22°C)21. As a cationic peptide, we used poly-l-lysine (K10). The pKa of the lysine side chain is 10.5, and this peptide is expected to be fully protonated at the neutral pH67. The K10 peptide induced RNA complex coacervation (Fig. 6a). These coacervates exhibited liquid-like behavior and upon fusion of two or more droplets, they rapidly relaxed to a spherical geometry (Supplementary Fig. 17a). The fusion timescales, τfusion, increased linearly with the droplet size, indicating that these coacervates behave like simple viscous liquids (Supplementary Fig. 17a). The measured viscosity, η, for rU-60/K10 complex coacervates was 4.4 ± 1.6 Pa.s (mean ± standard deviation, n = 5) and increased progressively by about two orders of magnitude to 476 ± 96 Pa.s (mean ± standard deviation, n = 5) as the hybridization energy, εRNA, was increased to 9.5, by either modulating the patch sequence (Fig. 6b) or by changing temperature (Fig. 6c, Supplementary Fig. 18). The interfacial tension for RNA-peptide coacervates was ~1 mN/s and only modestly varied with εRNA (Supplementary Fig. 17b). Like patchyDNA, all measured values of η and η/γ across various perturbations could be described by a single exponential relationship (Fig. 6d, e). This exponential scaling between η and εRNA demonstrates that the dynamics of these droplets scale with the lifetime of RNA-RNA bonds and reinforces that the macroscopic properties of these RNA-containing condensates are tuned by inter-strand RNA hybridization.

a Top: representative micrographs (n = 5 independent experiments) showing that non-base-pairing U-60 RNA forms complex coacervates with poly-l-lysine (K10). Scale bar, 10 µm. Bottom: schematic depicting the design of a 60-nucleotide long patchyRNA with four hybridization patches. Table shows hybridization energy of patches (εRNA) at 22 °C. MSD of passivated beads in patchyRNA/K10 condensates, where εRNA was modulated either by varying the patch sequence (b) or by temperature (c). The color bars represent the range of εRNA. Each datapoint is mean of n = 5 experiments. The logarithm of viscosity (η) (d), and inverse-capillary velocity (η/γ) (e) scales linearly with εRNA (dotted line, slope (mean ± SE) = 0.22 ± 0.01, R2 = 0.85 and 0.25 ± 0.03, R2 = 0.98, respectively). The solid and open symbols in (d) denote εRNA was varied by changing the patch sequence or by temperature respectively. Each data in (d) depicts mean ± SD for n = 5 experiments. Each data point in e represents mean ± 95% CI. Error bars for some data points in (d, e) are smaller than the symbols, and thus not visible in the plots (see Supplementary Fig. 17d, e).

Discussion

We harnessed the two fundamental properties of nucleic acids, the negative charge and the sequence programmability of their bonding, to generate liquid-like materials with exquisite control over their physical properties. By super-imposing transient base-pairing interactions onto electrostatic interaction mediated coacervates, we were able to achieve remarkable control over the molecular dynamics. Engineering the nucleic acid sequence enabled us to program the lifetime of inter-strand cross-links, and these molecular-scale interactions manifest in the macroscopic properties of the condensed phase. The material properties scale exponentially with the predicted hybridization energy and allow us to exert striking control over the bulk properties by manipulating the sequence. This ability to tune material properties, in conjunction with the inherent stability and biocompatibility of nucleic acids, may inspire a class of self-assembling materials.

Polymer networks with dynamic and reversible associations exhibit properties that are not achieved in conventional polymers with static cross-links, and offer functionalities such as ease of degradation, responsiveness to stimuli, and self-healing36,37. Given these desirable properties, there is considerable interest in generating polymers with reversible associations, but it remains challenging to precisely engineer the strength and positioning of these interactions in synthetic polymers. Employing DNA hybridization for inter-chain interactions provides exceptional control over the engineerability of these association sites. Ongoing advances in theory and simulations, such as modeling droplet behavior in associative polymer systems68, may allow for more accurate estimation of the ionic environment and interaction energies within the condensed phase. Additionally, improvements in DNA synthesis scales69 and the development of chimeric DNA-conjugated polymers70 could pave the way for producing bulk-scale materials with precise control over material properties. There is also tremendous interest in understanding the physics of associative polymers, but limitations in generating synthetic polymers with desired molecular patterns, interactions, and lengths, have hampered experimental examination. Our system may provide a facile platform to overcome these challenges and advance our fundamental understanding of associative polymer systems.

Our work also has implications towards understanding the assembly of biomolecular condensates in the cell. RNA provides scaffold for the formation of numerous biomolecular condensates but how the sequence-specific physicochemical properties of RNA affect its condensation is only beginning to be uncovered66,71. Previous works have shown that single-stranded and double-stranded nucleic acids, that differ in stiffness and charge density, yield coacervates with distinct properties30,65. We show that besides stable duplexes, transient sequence-specific inter-molecular base-pairing between RNA may profoundly alter condensate properties. These transient interactions impede molecular diffusion and may tune reaction rates. Cellular condensates are also enriched in proteins with intrinsically disordered regions which readily undergo phase separation in vitro. A considerable body of work has expanded our understanding of how the sequence composition of intrinsically disordered proteins influences phase behavior and material properties of the resulting condensates56,72,73,74,75,76. Mutations in proteins that alter the viscoelastic properties of condensates are observed in neurodegenerative diseases77. For example, ALS-causative mutations in FUS and TDP-43 reduce stress granules dynamics78. Our work shows that like proteins, RNA sequence and base-pairing interactions can have a profound effect on condensate properties and may potentially harbor disease causative mutations. Analogous to the molecular grammar of condensate-associated proteins79, our work may lay the foundation for uncovering the ‘RNA grammar’ in condensates. Altogether, these advancements may help illuminate the principles that govern the formation and function of RNA-protein granules in the cell and may be potentially used to create synthetic membraneless organelles80.

Methods

Chemicals

Single-stranded DNA and RNA oligonucleotides were purchased from IDT, USA. Spermine tetrahydrochloride and poly-l-lysine hydrochloride (MW 1600 Da) were purchased from Millipore Sigma, USA (S2876), and Alamanda Polymers, USA (26124-78-7), respectively. Nuclease-free water (AM9939) and Tris buffers (pH 7.0, AM9850G and pH 8.0, AM9855G) were obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA. IDTE pH 7.5 was purchased from IDT, USA (11-05-01-15). DNA was resuspended at a concentration of 250 µM in TE buffer (10 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 0.1 mM EDTA). RNA was resuspended at a concentration of 200 µM in IDTE pH 7.5. Stock solutions of spermine hydrochloride (100 mM) and poly-l-lysine hydrochloride (25 mM) were prepared in nuclease-free water. Stock solutions were aliquoted and stored at −20 °C and thawed immediately before use.

In vitro complex coacervation

DNA complex coacervates were prepared by sequentially adding the reagents to a PCR tube in the following order to the indicated concentrations: nuclease-free water, Tris buffer (pH 7.0, 10 mM), DNA solution (10 µM), labeled DNA (40 nM), spermine (4 mM), and NaCl (0–160 mM). The components were thoroughly mixed by pipetting. Immediately after mixing, the solution became turbid indicative of phase separation. The mixture was transferred onto a passivated glass surface for visualization under a microscope. For examining heterotypic interactions, the stock solutions of two DNA species were first mixed at the desired stoichiometric ratio, and complex coacervation was induced as described above. The resulting complex coacervates of DNA mixtures were heat denatured at 70 °C for 3 min, and cooled down to room temperature before characterization. RNA coacervates were prepared by mixing RNA (16 µM) and poly-l-lysine (0.5 mM) in 10 mM Tris (pH 7.0).

Glass passivation

Glass-bottom 384-well plates (Brooks, MatriPlate MGB101-1-2-LG-L) and cover glass (VWR, USA, 48393-251) were passivated with PEG-silane (MW = 5 kD, Laysan bio, MPEG-SIL-5000-1g). Briefly, the glass surface was first activated with a 0.5 M NaOH (Millipore Sigma, USA, 1310-73-2) solution for 20 min at 40 °C. This solution was removed, and the glass surface was rinsed three times using Milli-Q water and dried at 40 °C for an additional 30 min. Subsequently, the glass surface was treated with 5% (w/v) PEG-silane in anhydrous ethanol and incubated at room temperature (22 °C) for 20 min. After removing the PEG-silane solution, the glass surface was washed three times with Milli-Q water and dried using a gentle flow of dry air. The passivated glasses were used immediately or stored at 4 °C.

Microsphere passivation

Red-fluorescent carboxy-coated polystyrene beads (diameter = 100 nm, Invitrogen FluoSpheresTM F8801) were passivated with amine-terminated methoxy-PEG (mPEG-NH2; MW 750 Da; Millipore Sigma 07964) following the protocol described by Valentine, M. T. et al.81. Briefly, beads were diluted to 4 × 1012 particles/ml and tip-sonicated (10% amplitude, 5 s on, 5 s off, 30 s total time) to minimize inter-bead adhesion. The diluted bead solution was dialyzed into 100 mM 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid (MES, 150x volume, Millipore Sigma M3671) at pH 6.0 for 2.5 h. The dialysis bag was rinsed with deionized water and transferred to a solution mixture of 100 mM MES, 15 mM 1-[3-(dimethylamino)propyl]-3-ethylcarbodiimide (Millipore Sigma E6383), 5 mM N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) (Millipore Sigma 130672), and a 10x excess of mPEG-NH2. After 40 min of reaction, the dialysis bag was transferred to borate buffer (50 mM boric acid, Millipore Sigma B0394, 36 mM sodium tetraborate, Millipore Sigma 221732) at pH 8.5 containing 5 mM NHS and a 10x excess of mPEG-NH2 and dialyzed for at least 8 h. This dialysis protocol was repeated two more times before transferring the dialysis cassette to pure borate buffer, where dialysis continued for another 4 h. Upon completion of dialysis, the bead solution was removed from the dialysis cassette, diluted (50x volume) into 10 mM Tris (Millipore Sigma 93352) pH 7.0 buffer, and stored at 4 °C for future use.

Microscopy

Complex coacervates were visualized using an Andor Dragonfly 500 spinning disk confocal system (Oxford Instruments, USA) mounted on a Nikon TE2000E inverted microscope using a 100x Nikon oil immersion objective (NA 1.45). Images were acquired an Andor iXon EM-CCD or an Andor Zyla sCMOS (Oxford Instruments, USA). Images were captured using 561 nm (for Cy3 labeled DNA), and 637 nm (for Cy5 labeled DNA) excitation lasers. The imaging scan speed was varied between 200 and 0.1 Hz, depending on the dynamics (FRAP recovery rates, MSD of microspheres, and fusion of coacervates) of the samples. Imaging data were processed and analyzed using ImageJ.

Temperature-controlled experiments were conducted using a CherryTemp setup (Cherry Biotech, France) and captured using the spinning disk confocal system described above. In each experiment, a freshly prepared solution was deposited onto a passivated cover glass, and a thermalization chip was positioned on top of the slide following the manufacturer’s protocol. The glass slide and the chip were separated by 500 µm liquid silicone spacers. Temperature was varied between 20 °C and 45 °C with a precision of 0.1 °C. After each heating or cooling step, the system was allowed to equilibrate for 2 min before acquiring the images.

FRAP

FRAP measurements were conducted using a Micro Point pulsed nitrogen-pumped dye laser (405 nm) from Andor Technologies, integrated with the spinning disk confocal microscope. For each experiment, a circular spot with a diameter of ≈1 µm at the center of the complex coacervates was bleached. For experiments involving partial photobleaching, we selected droplets with a minimum diameter of ≈10 µm. Fluorescence recovery was recorded at different frame rates for the various patchyDNA sequences in order to account for their different mobility and to minimize the effects of photobleaching during imaging. For rapidly recovering T-90, GC, and GTAC coacervates, movies were acquired at 10 fps (frames per second) (30 s total), while GGCC, GAATTC, and GGATCC coacervates were imaged at 1 fps (300 s total). For GGGCCC and GGAATTCC coacervates, we used 0.1 fps frame rate (30 min total). Temperature-dependent FRAP experiments were conducted using the CherryTemp setup described above.

To determine the characteristic recovery time, the mean fluorescence intensity of the circular bleached region (B(t), 1 µm diameter) and mean intensity at the center of an unbleached coacervate (U(t), 1 µm diameter) were monitored before and after photobleaching. The background noise (N(t)) during this imaging was measured by monitoring a circular area (1 µm diameter) in the solution phase, outside of the droplet. The corrected intensity at the bleach spot, I(t), was calculated using the following relation:

Here, U(0), B(0), and N(0) are mean pre-bleach intensities averaged over 5 frames. The recovery data were corrected to account for lost signal due to the bleaching pulse and photobleaching during imaging. The recovery data were normalized (IN(t)) and the characteristic FRAP recovery time, τFRAP, was calculated by fitting IN(t) vs. t with the following equation:

where A is the total recovery fraction. The self-diffusion coefficient (Dself) of DNA within the coacervates was estimated using the following relation:

where a is the radius of the bleached spot (0.5 µm)

Condensate fusion

Spontaneous fusion events were manually identified in movies of condensates recorded using either an Andor iXon EM-CCD (for movies at <20 fps) or an Andor Zyla sCMOS (for movies at > 20 fps). Fusion events for T-90 and GC coacervates were recorded at 200 fps, while coacervates of the other patchyDNA were recorded at rates ranging from 10 to 0.1 fps. The characteristic fusion time, τfusion, was calculated from the temporal evolution of the aspect ratio (AR(t)) of a coacervate after contact using the following relation:

We chose fusion events between droplets of roughly similar size. In a typical fusion event, AR(t = 0) ≈ 2 and relaxes to ≈1 over time. For each patchyDNA, we examined fusion events across a range of droplet sizes. The inverse capillary velocity (η/γ) for was then calculated using the following relation:

Where l is the size of the coacervate after fusion, defined as:

Here, llong and lshort are the long and short axes of the coacervate, respectively. Coacervate fusion experiments were performed on freshly passivated 384-well plates to minimize effects of surface adsorption on fusion dynamics.

Single particle tracking

The viscosity of coacervates was calculated by tracking trajectories of passivated fluorescent polystyrene beads (diameter = 100 nm, Thermo Fisher, USA) embedded in coacervates. Bead trajectories were imaged using Andor iXon EMCCD with a 561 nm excitation laser at 5 fps and analyzed using the Trackmate plugin in ImageJ82.

The diffusion coefficient of beads (Dprobe) was calculated from the MSD using the following relation:

Here, α is the diffusion exponent, and NF is the noise floor, estimated by tracking beads stuck at the bottom of the coacervates. Coacervates viscosity was estimated using the Stokes-Einstein relation:

Here, rprobe = 50 nm. For all MSD experiments, beads diffusing far away from the coacervate-solution interface were examined in order to minimize any surface effects on bead trajectories. Where indicated, the temperature was modulated using the CherryTemp instrument, as described above, and for each temperature, NF was determined independently.

FRET

To determine FRET efficiency within complex coacervates, we used a method similar to that was used by Nott et al.83. In brief, three fluorescent images: DD, DA, and AA at a fixed z-plane are captured. Here DD = donor emission after donor excitation; DA (FRET signal) = acceptor emission after donor excitation and AA = acceptor emission after acceptor excitation. The FRET efficiency (F) at a given region of interest is then given by,

The donor (Cy3) and acceptor (Cy5) fluorophores were incorporated at the 5’ terminus of the DNA sequences (see Supplementary information for sequences). Cy3 and Cy5 were excited by 561 nm and 637 nm lasers respectively and their emissions were collected using 600–50 nm and 700–75 nm bandpass filters respectively. To correct for spectral overlap, we calculated corrected FRET efficiency by using three sets of samples: sample containing (a) both Cy3-Cy5 (DDCy3-Cy5, DACy3-Cy5, AACy3-Cy5), (b) only Cy3 (DDCy3, DACy3, AACy3) and (c) only Cy5 (DDCy5, DACy5, AACy5). The corrected FRET efficiency, Fcorr for each pixel within the region of interest was calculated by following the relation,

where \(\alpha=\frac{{{DA}}_{{Cy}3}}{{{DD}}_{{Cy}3}\,}\) and \(\beta=\frac{{{DA}}_{{Cy}5}}{{{AA}}_{{Cy}5}\,}\)

Low intensity values corresponding to DDCy5 and AACy3 confirmed that signal bleed-through between channels was minimal. All images were background corrected before processing.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Unless otherwise noted, all data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article, the Supplementary Information, and the Source Data files. Source data for all graphs in the main manuscript and Supplementary Information are provided. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Blackburn, G. et al. (eds) Nucleic Acids in Chemistry and Biology (Royal Society of Chemistry, 2022).

Jones, M. R., Seeman, N. C. & Mirkin, C. A. Programmable materials and the nature of the DNA bond. Science 347, 1260901 (2015).

Dey, S. et al. DNA origami. Nat. Rev. Methods Prim. 1, 13 (2021).

Han, D. et al. Single-stranded DNA and RNA origami. Science 358, eaao2648 (2017).

Um, S. H. et al. Enzyme-catalysed assembly of DNA hydrogel. Nat. Mater. 5, 797–801 (2006).

Biffi, S. et al. Equilibrium gels of low-valence DNA nanostars: a colloidal model for strong glass formers. Soft Matter 11, 3132–3138 (2015).

Udono, H., Gong, J., Sato, Y. & Takinoue, M. DNA droplets: intelligent, dynamic fluid. Adv. Biol. 7, 2200180 (2023).

Samanta, A., Hörner, M., Liu, W., Weber, W. & Walther, A. Signal-processing and adaptive prototissue formation in metabolic DNA protocells. Nat. Commun. 13, 3968 (2022).

Biffi, S. et al. Phase behavior and critical activated dynamics of limited-valence DNA nanostars. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 15633–15637 (2013).

Jeon, B. et al. Salt-dependent properties of a coacervate-like, self-assembled DNA liquid. Soft Matter 14, 7009–7015 (2018).

Sato, Y., Sakamoto, T. & Takinoue, M. Sequence-based engineering of dynamic functions of micrometer-sized DNA droplets. Sci. Adv. 6, eaba3471 (2020).

Do, S., Lee, C., Lee, T., Kim, D.-N. & Shin, Y. Engineering DNA-based synthetic condensates with programmable material properties, compositions, and functionalities. Sci. Adv. 8, eabj1771 (2022).

Abraham, G. R. et al. Nucleic acid liquids. Rep. Prog. Phys. 87, 066601 (2024).

Stewart, J. M. et al. Modular RNA motifs for orthogonal phase separated compartments. Nat. Commun. 15, 1–13 (2024).

Fabrini, G. et al. Co-transcriptional production of programmable RNA condensates and synthetic organelles. Nat. Nanotechnol. 19, 1665–1673 (2024).

Lightfoot, H. L. & Hall, J. Endogenous polyamine function—the RNA perspective. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, 11275–11290 (2014).

Corley, M., Burns, M. C. & Yeo, G. W. How RNA-binding proteins interact with RNA: molecules and mechanisms. Mol. Cell 78, 9–29 (2020).

Rumyantsev, A. M., Jackson, N. E. & De Pablo, J. J. Polyelectrolyte complex coacervates: recent developments and new frontiers. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 12, 155–176 (2021).

Sing, C. E. & Perry, S. L. Recent progress in the science of complex coacervation. Soft Matter 16, 2885–2914 (2020).

Lu, T. & Spruijt, E. Multiphase complex coacervate droplets. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 2905–2914 (2020).

Aumiller, W. M., Pir Cakmak, F., Davis, B. W. & Keating, C. D. RNA-based coacervates as a model for membraneless organelles: formation, properties, and interfacial liposome assembly. Langmuir 32, 10042–10053 (2016).

King, J. T. & Shakya, A. Phase separation of DNA: from past to present. Biophys. J. 120, 1139–1149 (2021).

Oparin, A. I. The origin of life and the origin of enzymes. Adv. Enzymol. Relat. Areas Mol. Biol. 27, 347–380 (1965).

Drobot, B. et al. Compartmentalised RNA catalysis in membrane-free coacervate protocells. Nat. Commun. 9, 3643 (2018).

Luo, D. & Saltzman, W. M. Synthetic DNA delivery systems. Nat. Biotechnol. 18, 33–37 (2000).

Paunovska, K., Loughrey, D. & Dahlman, J. E. Drug delivery systems for RNA therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Genet 23, 265–280 (2022).

Banani, S. F., Lee, H. O., Hyman, A. A. & Rosen, M. K. Biomolecular condensates: organizers of cellular biochemistry. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 18, 285–298 (2017).

Brangwynne, C. P., Tompa, P. & Pappu, R. V. Polymer physics of intracellular phase transitions. Nat. Phys. 11, 899–904 (2015).

Aumiller, W. M. & Keating, C. D. Phosphorylation-mediated RNA/peptide complex coacervation as a model for intracellular liquid organelles. Nat. Chem. 8, 129–137 (2016).

Vieregg, J. R. et al. Oligonucleotide-peptide complexes: phase control by hybridization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 1632–1638 (2018).

Shakya, A. & King, J. T. DNA local-flexibility-dependent assembly of phase-separated liquid droplets. Biophys. J. 115, 1840–1847 (2018).

Boeynaems, S. et al. Spontaneous driving forces give rise to protein−RNA condensates with coexisting phases and complex material properties. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 116, 7889–7898 (2019).

Jain, A. & Vale, R. D. RNA phase transitions in repeat expansion disorders. Nature 546, 243–247 (2017).

Ma, W., Zhen, G., Xie, W. & Mayr, C. In vivo reconstitution finds multivalent RNA-RNA interactions as drivers of mesh-like condensates. Elife 10, e64252 (2021).

Van Treeck, B. et al. RNA self-assembly contributes to stress granule formation and defining the stress granule transcriptome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 115, 2734–2739 (2018).

Zhang, Z., Chen, Q. & Colby, R. H. Dynamics of associative polymers. Soft Matter 14, 2961–2977 (2018).

Webber, M. J. & Tibbitt, M. W. Dynamic and reconfigurable materials from reversible network interactions. Nat. Rev. Mater. 7, 541–556 (2022).

Semenov, A. N. & Rubinstein, M. Thermoreversible gelation in solutions of associative polymers. 1. Statics Macromol. 31, 1373–1385 (1998).

Zadeh, J. N. et al. NUPACK: analysis and design of nucleic acid systems. J. Comput Chem. 32, 170–173 (2011).

Zeng, Y., Montrichok, A. & Zocchi, G. Bubble nucleation and cooperativity in DNA melting. J. Mol. Biol. 339, 67–75 (2004).

Ares, S., Voulgarakis, N. K., Rasmussen, K. Ø. & Bishop, A. R. Bubble nucleation and cooperativity in DNA melting. Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 035504 (2005).

Bianchi, E., Blaak, R. & Likos, C. N. Patchy colloids: state of the art and perspectives. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 13, 6397–6410 (2011).

Blagbrough, I. S., Metwally, A. A. & Geall, A. J. Measurement of polyamine pKa values. Methods Mol. Biol. 720, 493–503 (2011).

Spruijt, E. et al. Structure and dynamics of polyelectrolyte complex coacervates studied by scattering of neutrons, X-rays, and light. Macromolecules 46, 4596–4605 (2013).

Muthukumar, M. A perspective on polyelectrolyte solutions. Macromolecules 50, 9528–9560 (2017).

Wang, J., Devarajan, D. S., Nikoubashman, A. & Mittal, J. Conformational properties of polymers at droplet interfaces as model systems for disordered proteins. ACS Macro Lett. 12, 1472–1478 (2023).

Sabanayagam, C. R., Eid, J. S. & Meller, A. Using fluorescence resonance energy transfer to measure distances along individual DNA molecules: corrections due to nonideal transfer. J. Chem. Phys. 122, 061103 (2005).

Sim, A. Y. L., Lipfert, J., Herschlag, D. & Doniach, S. Salt dependence of the radius of gyration and flexibility of single-stranded DNA in solution probed by small-angle x-ray scattering. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlin Soft Matter Phys. 86, 021901 (2012).

Fu, J. & Schlenoff, J. B. Driving forces for oppositely charged polyion association in aqueous solutions: enthalpic, entropic, but not electrostatic. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 980–990 (2016).

Wang, L. et al. Hydrogen bonding enhances the electrostatic complex coacervation between κ-carrageenan and gelatin. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 482, 604–610 (2015).

Zhang, H. et al. RNA controls PolyQ protein phase transitions. Mol. Cell 60, 220–230 (2015).

Taylor, N. O., Wei, M. T., Stone, H. A. & Brangwynne, C. P. Quantifying dynamics in phase-separated condensates using fluorescence recovery after photobleaching. Biophys. J. 117, 1285–1300 (2019).

Rubinstein, M. & Semenov, A. N. Dynamics of entangled solutions of associating polymers. Macromolecules 34, 1058–1068 (2001).

Baxandall, L. G. Dynamics of reversibly crosslinked chains. Macromolecules 22, 1982–1988 (1989).

Mason, T. G. & Weitz, D. A. Linear viscoelasticity of colloidal hard sphere suspensions near the glass transition. Phys. Rev. Lett. 75, 2770–2773 (1995).

Elbaum-Garfinkle, S. et al. The disordered P granule protein LAF-1 drives phase separation into droplets with tunable viscosity and dynamics. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 7189–7194 (2015).

Eggers, J., Lister, J. R. & Stone, H. A. Coalescence of liquid drops. J. Fluid Mech. 401, 293–310 (1999).

Brangwynne, C. P., Mitchison, T. J. & Hyman, A. A. Active liquid-like behavior of nucleoli determines their size and shape in Xenopus laevis oocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 4334–4339 (2011).

Lyklema, J. (ed) Soft Colloids (Elsevier Academic Press, 2005).

Aarts, D. G. A. L., Schmidt, M. & Lekkerkerker, H. N. W. Direct visual observation of thermal capillary waves. Science 304, 847–850 (2004).

Spruijt, E., Sprakel, J., Cohen Stuart, M. A. & Van Der Gucht, J. Interfacial tension between a complex coacervate phase and its coexisting aqueous phase. Soft Matter 6, 172–178 (2010).

Rhine, K., Vidaurre, V. & Myong, S. RNA droplets. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 49, 247–265 (2020).

Choi, J.-M., Holehouse, A. S. & Pappu, R. V. Physical principles underlying the complex biology of intracellular phase transitions. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 49, 107–133 (2020).

Lin, Y., Protter, D. S. W., Rosen, M. K. & Parker, R. Formation and maturation of phase-separated liquid droplets by RNA-binding proteins. Mol. Cell 60, 208–219 (2015).

Choi, S., Meyer, M. O., Bevilacqua, P. C. & Keating, C. D. Phase-specific RNA accumulation and duplex thermodynamics in multiphase coacervate models for membraneless organelles. Nat. Chem. 14, 1110–1117 (2022).

Roden, C. & Gladfelter, A. S. RNA contributions to the form and function of biomolecular condensates. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 22, 183–195 (2021).

Mirtič, A. & Grdadolnik, J. The structure of poly-l-lysine in different solvents. Biophys. Chem. 175–176, 47–53 (2013).

Zheng, W. et al. Molecular details of protein condensates probed by microsecond long atomistic simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B 124, 11671–11679 (2020).

Praetorius, F. et al. Biotechnological mass production of DNA origami. Nature 552, 84–87 (2017).

Cangialosi, A. et al. DNA sequence–directed shape change of photopatterned hydrogels via high-degree swelling. Science 357, 1126–1130 (2017).

Wadsworth, G. M. et al. RNA-driven phase transitions in biomolecular condensates. Mol. cell 84, 3692–3705 (2024).

Sundaravadivelu Devarajan, D. et al. Sequence-dependent material properties of biomolecular condensates and their relation to dilute phase conformations. Nat. Commun. 15, 1912 (2024).

Rekhi, S. et al. Expanding the molecular language of protein liquid–liquid phase separation. Nat. Chem. 16, 1113–1124 (2024).

Simon, J. et al. Programming molecular self-assembly of intrinsically disordered proteins containing sequences of low complexity. Nat. Chem. 9, 509–515 (2017).

Wang, H. et al. Surface tension and viscosity of protein condensates quantified by micropipette aspiration. Biophy. J. 1, 100011 (2021).

Alshareedah, I., Moosa, M. M., Pham, M., Potoyan, D. A. & Banerjee, P. R. Programmable viscoelasticity in protein-RNA condensates with disordered sticker-spacer polypeptides. Nat. Commun. 12, 1–14 (2021).

Zhou, X. et al. Mutations linked to neurological disease enhance self-association of low-complexity protein sequences. Science 377, eabn5582 (2022).

Li, Y. R., King, O. D., Shorter, J. & Gitler, A. D. Stress granules as crucibles of ALS pathogenesis. J. Cell Biol. 201, 361–372 (2013).

Martin, E. W. et al. Valence and patterning of aromatic residues determine the phase behavior of prion-like domains. Science 367, 694–699 (2020).

Xue, Z. et al. Targeted RNA condensation in living cells via genetically encodable triplet repeat tags. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, 8337–8347 (2023).

Valentine, M. T. et al. Colloid surface chemistry critically affects multiple particle tracking measurements of biomaterials. Biophys. J. 86, 4004–4014 (2004).

Ershov, D. et al. TrackMate 7: integrating state-of-the-art segmentation algorithms into tracking pipelines. Nat. Methods 19, 829–832 (2022).

Nott, T. J., Craggs, T. D. & Baldwin, A. J. Membraneless organelles can melt nucleic acid duplexes and act as biomolecular filters. Nat. Chem. 8, 569–575 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We thank Ofer Kimchi, Ella King, Daniel Stein, Alfredo Alexander-Katz, and members of Jain lab for helpful discussions. This work was supported by grants to A.J. from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (R35GM151111), the David and Lucile Packard Foundation, and the Pew Biomedical Scholars Program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.M. and A.J. conceptualized the project and designed the experiments. S.M. conducted the experiments and analyzed the data. S.M. and A.J. interpreted the data. S.C. provided passivated beads for microrheology experiments. S.M. and A.J. wrote the manuscript with inputs from S.C. and N.F.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Majumder, S., Coupe, S., Fakhri, N. et al. Sequence-encoded intermolecular base pairing modulates fluidity in DNA and RNA condensates. Nat Commun 16, 4258 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-59456-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-59456-0

This article is cited by

-

Nanocluster intermediates orchestrate the phase transition of ATP condensates

Communications Chemistry (2025)