Abstract

Manipulating floating objects, whether solid or liquid, from microscopic to mesoscopic sizes, is crucial in various microfluidics and microfabrication applications. While capillary menisci naturally self-assemble and transport floating particles, their shapes and sizes are limited by the properties of the fluid and the objects involved. We herein harness the superposition of capillary menisci to curve liquid interfaces controllably. By using 3D-printed spines piercing the interface, we can finely adjust height gradients across the liquid surface to create specific liquid topographies. Thus, our method becomes a powerful tool for manipulating floating objects into programmable paths. Combining experimental demonstrations, numerical simulations, and theoretical modeling, we study the liquid elevation created by specific spine dispositions and the three-dimensional manipulation of submillimetric particles. Multiple examples showcase the method’s potential applications, including sorting and capturing particles, which could pave the way for cleaning fluid interfaces.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In nature, capillary menisci serve various purposes. They enhance the aggregation of objects at liquid interfaces, like mosquito eggs1, bubbles2, or cereals3. Water-walking insects use menisci to reach the shore4, while surface-piercing vegetation captures particles on water surfaces5,6. Such natural phenomena have long inspired scientists to exploit menisci or curved interfaces to self-assemble7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19, transport20,21,22, or manipulate23,24,25 floating objects. Pillars, in particular, have been used to curve the interface by pinning it to the pillar cross-section, enabling particle transport26,27,28. However, these pillar-based strategies typically focus on single pillars, resulting in axisymmetric deformations limited by the capillary length λ, around 2.7 mm for the water-air interface. Peng et al. notably created a meniscus gradient for bubble transport using multiple slippery oil-infused pillars with height gradients20.

In this study, we extend these concepts by exploring the superposition of capillary menisci generated by regularly arranged 3D-printed conical spines. By leveraging the interplay between spine geometry and spacing, we demonstrate control of liquid interface topographies over larger scales than the capillary length. Experimental results, supported by theoretical modeling and numerical simulations, show that specific liquid landscapes and artistic topographies can be programmed by tuning spine parameters. These tailored liquid interfaces enable precise manipulation of floating particles. For instance, we illustrate how objects of different sizes can be directed along programmable paths or trapped at predetermined locations. Additionally, we provide an example of time-dependent manipulation by incorporating structural subfeatures on the spines, where the interface is dynamically pinned as the liquid level decreases. Finally, we highlight the broad range of applications for this work, including particle sorting, micromanipulation, and interface cleaning. This offers a versatile and scalable platform for future advancements in microfluidic systems.

Results

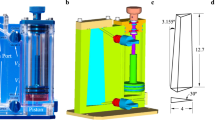

Single spine

Let us consider a conical spine crossing the water-air interface. Figure 1a presents a sketch of the conical spine defining its geometrical characteristics: the radius of its base R and its height H. A meniscus forms around such a spine, and the contact line height from the base is given by h + h0, where h0 is the height of the undisturbed surface. Figure 1b presents a picture of the typical meniscus forming around a 3D printed spine with a half opening angle \(\alpha=\arctan (R/H)\) being α = 3°. The shape of the meniscus z(x, y) is determined by the condition that the surface overpressure, which arises from surface tension and is directly related to the curvature of the interface, matches the hydrostatic pressure difference caused by the interface’s deformation29. In an approach where interface slopes are considered small enough, this condition is mathematically written as the linearized Laplace-Young equation

defining the capillary length

which is the characteristic length scale at which gravitational forces and surface tension forces are balanced. Several research studies, including those conducted by Lo30, Kralchevsky31, and Cooray32, among others, have been undertaken to investigate the formation of the meniscus around a vertical cylinder. Eq. (1) can be rewritten in cylindrical coordinates thanks to the cylinder’s axisymmetry. Its solution gives the profile z as a function of the radial distance r counted from the center of the cylinder. One has

where K0 is a decaying zero-order modified Bessel function of the second kind and Q is a constant of integration usually called the capillary charge of the cylinder and has a crucial importance for capillary interactions33. For a cylinder piercing a liquid-fluid interface, Cooray et al.32 have determined Q by using Archimedes principle stating that, at equilibrium, the weight of the liquid lifted in the meniscus must equal the capillary force acting on the contact line. For the cylinder, assuming R ≪ λ, this characteristic elevation is \({Q}_{cyl}=R\cos \theta\), where θ is the contact angle as defined in the sketch from Fig. 1. The previous assumptions for the conical spine studied herein still hold since the contact line keeps axisymmetry. Yet, the contact line radius changes with the liquid height. For the conical spine, we, therefore, assume a characteristic elevation

The above general description (3) of the meniscus tells us that the horizontal extension of the meniscus is limited by the capillary length λ.

a Sketch of a single conical spine crossing the liquid-air interface. The geometrical characteristics of the spine H and R and the associated meniscus height h are emphasized. The dashed horizontal line denotes the undisturbed interface z = 0 at height h0 from the spine’s base. b Sketch of the edge of a square array of spines separated by a. The water profile highlights the slight undulation of the interface between the spines from a maximal height h to a lower liquid height hv between spines. c Picture of a 3D-printed conical spine crossing blue-colored water and illustrating the meniscus formation. d A closeup of the liquid menisci at the edge of a square lattice. The liquid interface inside the lattice is 3.5 mm above the undisturbed interface. Scale bars: 1 mm.

Regularly arranged spines

A primary motivation of the present work is to defy this limitation by creating giant menisci with a horizontal extension much larger than λ. In other words, we would like to obtain a steady situation in which the interface is tilted over the entire container size. To reach this challenging situation, we consider an array of identical conical spines. Each spine crossing the interface is the origin of a meniscus, described by Eq. (3). When they are close to each other, i.e., when the lattice spacing a ≲ λ, the menisci created on neighboring spines superimpose. Regular microstructures are also notably used to mimic the wetting of specific surfaces34,35, like porous materials36,37 or super-hydrophobic surfaces38. Figure 1c,d shows a sketch and a picture of the edge of a square lattice of spines. The liquid rises above the undisturbed interface inside the lattice, proving the effect is significant. On average, the interface on the whole lattice is nearly flat. Nevertheless, small valleys are seen in between neighboring spines. In these valleys, the interface height hv is slightly smaller than h.

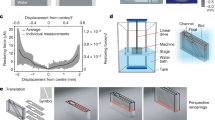

Experimental measurements of the interface position have been done by optical means. Figure 2a plots the heights h in orange and hv in purple dots as a function of the unit cell area A function for 12 square lattices. All lattices are 3D printed with fixed spine shapes (R = 0.2 mm and α = 1.15°) and varying lattice spacing a. The range of geometrical parameters is constrained by the 3D printing method used. Although the 3D printer has a specified resolution of 16 μm, our experimental tests have demonstrated that we can print spines with a base distance as small as 0.3 mm. If this distance is reduced further, the gap between the spines becomes too small, causing complications during the 3D printing process and potentially resulting in the individual spines sticking together. Consequently, the chosen lattice spacing a and base radius R are determined by the limitations of our methodology. The 3D-printed material and the fluids determine the contact angle. For the air-water interface, we measured a contact angle of θ = 53° on our spines. For small lattice spacing a, h and hv are quite similar, while the difference between those couples of points seems to increase with the unit cell area A. High water elevations h up to 5-6 mm are reached with small lattice spacing. This order of magnitude is comparable to the capillary rise in a millimeter tube as given by Jurin’s law39.

a Measured height at meniscus h and between spines hv of water in square lattice as a function of the unit area A. Experimental and numerical results are presented. Spines' characteristics are R = 0.2 mm and α = 1.15° and the bath level is h0 = 0 mm. The orange and purple curves are predictions of Eq. (6) and (7) respectively. The red region is the region over which the superposition approximation is no longer valid. The green curve represents \(\overline{h}\), the solution from Eq. (9), the force balance model. b Elevations h and hv of the interface in a square lattice as a function of the spine radius R when α = 3°, A = 2.25 mm2 and h0=1 mm. c Height h and hv as a function of the angle α for spines of radius R = 0.5 mm, lattice spacing A = 2.25 mm2, and bath level h0 = 1 mm.

We propose to describe the interface behavior using the Linear Superposition Approximation (LSA), which assumes the total interface results from the linear superposition of individual menisci formed around each spine. This principle, rooted in Nicolson’s work2, is widely applied to study capillary interactions between floating bodies1,2,3,11,14,31,32,33,40,41,42,43,44. Vassileva et al.44 demonstrated the validity of the superposition approximation for capillary interactions between two cylinders of radius R at a separation d > 4R by comparing exact and LSA capillary force. For smaller separations between cylinders, the superposition approximation underestimates the liquid elevation between cylinders and the resulting capillary force. Extending this result to our study, we assume the superposition approximation to be valid when \(a \, > \, 4(R-(h+{h}_{0})\tan \alpha )\). Under this framework, the liquid elevation at a position \(\overrightarrow{r}=(x,y)\) inside the lattice is given by:

where k and ℓ are lattice indices running over the entire structure, with \({\overrightarrow{r}}_{k,\ell }=(ka,\ell a)\) for the square lattice. Looking around the central spine, i.e. when k = ℓ = 0, and substituting Q using Eq. (4), one finds the expression of the liquid elevation h at the contact line:

and the liquid elevation of the valley in between neighboring spines:

The profiles in the sketch of Fig. 1c were drawn using the LSA approximation. Figure 2a compares these predictions (orange and purple curves for h and hv, respectively) with experimental data. The agreement is excellent across all tested lattice spacings. The red region in Fig. 2a indicates the range where \(a \, < \, 4(R-h\tan \alpha )\), beyond which the LSA approximation fails. Notably, all experimental data fall within the model’s validity.

To further observe the robustness of the model, the non-linear Young-Laplace equation has been numerically solved for 2D square lattices of spines. Numerical results for h and hv are presented in Fig. 2a as orange and purple crosses, respectively. By comparing numerical simulations with the liquid heights h and hv determined using the LSA, we demonstrate that the validity range of the approximation observed by Vassileva et al.44 for two cylinders can be widened to a broader array of spines.

The meniscus height around the spines is influenced by three main geometric parameters: (i) lattice spacing a, (ii) spine radius R at z = 0, and (iii) opening angle α and the physical parameters λ and θ, which depend on the material and the fluids. To adjust the liquid height of the interface, one can modify geometric parameters like the cone’s base radius R or opening angle α.

Figure 2 (b) presents graphs of the experimental and numerical results for the liquid heights h and hv in a square grid when the radius of the spine R increases, with the A = 2.25 mm2 and α = 3° fixed. The selected parameters aim to showcase the model’s limitations while being constrained by the fabrication methods. The experimental data agree with the LSA model within the model’s validity. When the superposition approximation reaches its limit, the LSA tends to underestimate the liquid elevation, which is consistent with the work of Vasilleva et al.44. Figure 2c presents similar measurements for square arrays as a function of α and with other parameters fixed (R = 0.5 mm and A = 2.25 mm2). The comparison between experimental, numerical, and predicted results again demonstrates an excellent agreement within the LSA limit. While we concentrated on the central spine to simulate liquid elevation throughout the entire lattice, it is worth noting that the menisci at the lattice edges are distorted differently due to the absence of neighboring spines, which can be observed in Fig. 1(c) and (d). The LSA model effectively captures this specific distortion and the valleys between spines, both of which are crucial for potential manipulation applications.

Beyond the LSA limit, the liquid is nearly flat as h and hv converge, and the liquid height inside an area element A can be modeled by a simple force balance, as discussed in the Methods. The average liquid elevation \(\overline{h}\) predicted by this model and given in Eq. (9) is plotted in green in Fig. 2a–c. While effectively capturing the liquid elevation inside the lattice as the liquid gets flatter, the force balance model, unlike the LSA model, fails to capture the valleys and the specific distortion at the lattice edge.

Specific Liquid Topography

The above results show that liquid height is controlled by the geometric characteristics A, R, and α of an array of conical spines. Thus, the geometry of each individual spine or the lattice spacing can be adjusted to pin the interface at different heights within a unique array. Having effectively captured the impact of these parameters on the liquid elevation, we can employ this method to program unique liquid topography.

Elementary topographies can be programmed by varying the lattice spacing a or the total height of the spine H in one direction, radially or otherwise. Figure 3 shows various examples to showcase the method’s versatility and the wide range of menisci that can be generated. In Fig. 3a and b, two tilted interfaces are produced: (a) the first one is by gradually decreasing the total height H, which is equivalent to modifying the radius of the contact line while keeping the other parameters fixed, and (b) the second slope is obtained by increasing the lattice spacing a from left to right. Figure 3c and d display, respectively, a sinusoidal and a parabolic liquid interface produced by varying H sinusoidally and quadratically. Conical spines are truncated above the contact line to highlight the liquid interface. The experimental liquid heights for the sinusoidal and parabolic devices are presented in orange dots in subfigures (c) and (d). The predicted liquid height, derived from the LSA model for these sinusoidal and quadratic variations of H, is also plotted in orange curves in the subfigures to emphasize the correspondence between the intended and actual liquid topography. Figure 3e displays a hemispherical meniscus created by decreasing the total height H radially. Finally, Fig. 3f shows the meniscus created by two adjacent inclines with perpendicular slopes, thus creating a 90° turn in the height gradient. This meniscus is created by decreasing H and keeping R fixed to 0.5 mm.

a A liquid incline providing a tilted giant meniscus at equilibrium. The total height H of the spines gradually decreases along the lattice from left to right while the radius R = 0.2 mm is constant. b The same incline created by another lattice where the lattice spacing a gradually increases from left to right. c A sine wave topography created by sinusoidally varying the total height H of the spines of radius R = 0.2 mm. d A quadratic well created by varying quadratically the height H of spines of radius R = 0.3 mm. The experimental measurements and the predicted liquid elevation by Eq. (6) in devices c and d are plotted in the subfigures using dots and curves respectively. e A hemisphere created by radially decreasing the total height H of spines of the same radius R = 0.3 mm. f Two adjacent inclines with perpendicular slopes, therefore, creating a 90° turn in the height gradient. The inclines are created by varying the height H of spines of radius R = 0.5 mm. Scale bars: 10 mm.

To program arbitrary and complex liquid topographies, we solve the inverse problem of Eq. (6): starting from the desired liquid height, we numerically calculate the corresponding spines and lattice parameters. This allows us to create any liquid landscape from a given target shape, as Fig. 4 exemplifies. From the grayscale image of the Atomium, the famous Belgian monument, shown in Fig. 4a, we designed a lattice of truncated conical spines where each spine represents a pixel of different total height H. The values of H were determined based on the desired liquid elevation h, which is linked to each pixel value ranging from 0 to 255. As the liquid invades the lattice, it rises to different heights, resulting in a three-dimensional representation of the Atomium, as shown in Fig. 4b, which offers a perspective view of the experiment. Our method of designing the device that creates artistic liquid landscapes from any 2D images or 3D coordinates has been implemented in a Mathematica code available on GitHub (see Code Availability).

Meniscus-induced micromanipulations

The wide variety of menisci that specific arrangements of spines can create gives direct inspiration for micromanipulation. Indeed, when a particle floats on a surface that is tilted either by the presence of another particle, a wall meniscus, or, in our case, some spines, the resulting force is no longer perpendicular to the surface, which results in a net movement along the surface. Therefore, light particles, such as bubbles, move upward along the meniscus, following the height gradient, while heavier particles denser than the liquid move downward along the interface slope2,3. This simple assumption, first proposed by Nicolson2, allows to evaluate the capillary interaction between a particle and another meniscus by computing the gravitational potential energy of the particle at a specific height z in the latter meniscus. Thus, the interaction potential simply takes the shape of the liquid profile z(x, y) in which the particle sits. In 2022, Peng et al. have notably achieved directional bubble transport on a few slippery oil-infused pillars with height-gradient20. Being aware that complex tridimensional capillary transport can only be achieved by complexifying the liquid topography, we herein propose the use of specific arrays of spines as an effective strategy for particle transport at liquid interfaces.

To test our strategy, we conducted transport experiments of a heavy submillimeter bead floating on desired liquid topographies. As a first experiment, we successfully achieved unidirectional micromanipulation using the array shown in Fig. 3a, forming a giant slope along the interface. Figure 5a presents a 3D plot illustrating the z(x, y) profile of the meniscus, calculated using Eq. (5), superimposed on the 3D STL file of the device. This plot effectively illustrates a liquid slope of 4°. The grayscale image within the same figure provides a top-down view of the device, with trajectories of 400 μm diameter beads color-coded according to their instantaneous speed. Refer to the Supplementary Video S1 for the motion. Similar motions are observed in each row, following the slope of the tilted interface. By varying the particle size, the steepness of the slope, or the lattice spacing, we observed similar behaviors but at different speeds. For instance, under the same incline, a 500 μm bead is faster than an 800 μm bead, which is also faster than a 400 μm bead. When testing slope varying from 1° to 5° in increments of 0.5°, we observe a maximal speed for the slope of 3° for all bead sizes. These counter-intuitive observations emphasize the complexity of the forces acting on the beads. The drag force on spherical particles trapped at liquid interfaces depends on various factors, including the shape of the interface, whether the three-phase contact line is pinned or not, the immersion depth, and the driving force45,46,47,48. In our case, the liquid interface is not only tilted but also slightly undulated between the height h and hv following the periodic structure of the array, which highly complicates the bead’s dynamics. Therefore, the precise dynamics of particles manipulated in our device will be studied in future works. However, it should be noted that because the particles reach different speeds depending on their size when the beads leave the device, they come to rest at distinct positions. This observation opens up exciting possibilities for sorting particles based on size or wettability.

The 3D plots, calculated using Eq. (5), display the liquid landscape created by an arrangement of spines piercing the liquid. The plot is rainbow-colored according to the liquid elevation, and the spines are colored in light blue. In each subfigure, experimental trajectories of heavy submillimeter beads inside the same arrangement are represented and are color-coded according to their speed from purple to yellow. Real-time movies can be viewed in Supplementary Videos S1, S2, and S3 for figures a, b, and c respectively.

More strikingly, the multi-directional transport of particles can also be performed by other liquid topographies. Two examples are shown in Fig. 5b and c. Figure 5b presents the calculated liquid profile of the array displayed in Fig. 3f and the trajectory of an 800 μm bead descending the slope. The bead first falls down the slope along the x-direction. When the height gradient in the x-direction vanishes, the bead briefly stops and then continues its descent along the y-direction gradient. The 800 μm stops permanently inside the device when the height gradient and the bead’s inertia can no longer overcome the drag force and the slight undulation of the interface. The motion can be seen in Supplementary Video S2. We note that smaller beads (400 and 500 μm) came to rest outside this device. Once again, different particles are sorted, and the array controls the final positions. In Fig. 5c, we display a particular lattice forming a sinusoidal valley with a slight slope, allowing the bead to make a series of turns while descending the hill. See Supplementary Video S3 for the real-time motion inside the sinusoidal valley. Unlike the constant speed measured on the liquid slope of Fig. 5a, one can observe from the color-coded trajectory of a 500 μm bead that it is always decelerated in the turns, i.e., when the direction of motion changes, just as in the 90° turn of Fig. 5b.

As a first step toward actuating our lattice, we can draw inspiration from the work of Zeng et al.23, in which they manipulated floating objects by adjusting the liquid elevation within a vertical channel that has vertical variations in wettability. For our lattice, considering the simple case of cylinders (α = 0°), we have designed structural spines with substructures onto which the interface will be pinned as the liquid level falls. The upper part of the lattice consists of cylinders with small yet identical radii, creating a horizontal interface that traps particles. The lower part, uncovered as the liquid descends, consists of cylinders with decreasing radii to form a liquid slope and thus manipulate the floating particles. The menisci are, therefore, time-dependent. Figure 6 illustrates the upgraded device and demonstrates how the interface is pinned to the substructures as the liquid descends. Supplementary Video S4 showcases the manipulation of a 500 μm bead by a combination of these devices, enabling the bead to make a complete 360° turn.

Experimental water profiles within an array of spines with substructures are presented for three different levels of bath liquid. Initially, the liquid interface is pinned to cylinders of identical radius. As the bath level descends, the liquid interface is then pinned to cylinders with decreasing radii, and the liquid slope appears. The liquid interfaces are highlighted in red.

These illustrating examples offer promising prospects for precise object transport, such as positioning objects beneath a microscope lens, the utilization of liquid curvature as a ’capillary tweezer’24,28, or favoring specific structures on capillary self-assemblies, such as the side-by-side assembly of cylindrical particles on a curved interface17,19,25,26. It is worth noting that this manipulation method works for objects of any nature, solid or liquid, as long as they are attached to the liquid interface. Furthermore, as long as the distance between the spines is on the order of the capillary length, even microscopic objects can be controlled23. As the total size of the device is only limited by the fabrication process, one major and crucial application of our method could be the cleaning of interfaces from specific oil microdroplets and microscopic objects.

Discussion

The innovative approach presented herein demonstrates using arrays of 3D-printed conical spines to manipulate liquid surfaces precisely. By controlling the geometry, arrangement, and spacing of the spines, we achieved a wide variety of liquid topographies, ranging from inclined surfaces and sinusoidal patterns to complex artistic structures. These results confirm the ability to create tailored liquid landscapes over scales much larger than the capillary length, overcoming the limitations of traditional single-pillar systems. Through these programmable liquid interfaces, we showcased precise manipulation of floating particles, including directional transport, size-based sorting, and controlled trapping at predetermined locations. Moreover, by introducing structural subfeatures on the spines, we demonstrated time-dependent manipulation, where the interface dynamically evolves as the liquid level decreases. The versatility and scalability of this approach open promising avenues for practical applications, such as particle sorting, micromanipulation, and cleaning liquid interfaces from microscopic debris or oil droplets. Future work could explore the dynamic actuation of the spines using adaptive magnetic49 or magnetoelastic50 materials, shape-shifting materials35, shape memory polymers43, or mechanical systems to achieve real-time control of the liquid surface curvature. These advancements would further enhance the potential of this method for innovative microfluidic technologies and capillary-driven systems.

Methods

Design and 3D printing

The devices have been designed using a Mathematica script that creates all the spines with specific characteristics and in the desired arrangement with a 2 mm base. The script then exports the 3D graphics in an STL file (See Code Availability). Since the lattice spacing a and the shape of the spines can be modified, about 60 different devices were printed using a PolyJet 3D printer (Stratasys Object Prime 30). The PolyJet method consists of jetting out resin droplets onto the platform, which are then cured using UV light. It results in an excellent announced resolution of up to 16 μm. We used a resin similar to ABS plastic (Vero Blue) in a glossy finish.

Experimental measurements

The lattice was placed in the center of a Petri dish. The amount of water added to the system was controlled to define z = 0 and h0. The water level was determined by optical means, with a camera taking pictures from the side. The height h of the liquid above the undisturbed interface was measured by image analysis. For the experiments with solid particles, we took videos from above the device and then tracked the particles.

Numerical solution for the interface shape

The code used to solve the Young-Laplace equation has been adapted from Ho et al.13 and uses the ‘General Form PDE’ solver in COMSOL 5.3a. The PDE was solved in 2D for a square array. For the case of spines (i.e., α > 0), the contact line position in the 2D computational domain is not known a priori and was addressed as described in what follows. In the simulation, the contact lines were modeled as circular regions of radius Rc. The nonlinear Young-Laplace was solved exterior to the circular regions while enforcing a slope of θ + α at the contact line position. For a fixed combination of A, α, and λ, a range of simulations were run varying Rc. Then, for a targeted h0 and R in the experiment, the simulation wherein \({R}_{c}=R-(h+{h}_{0})\tan \alpha\) was satisfied was selected as the appropriate solution, and h and hv were extracted therefrom. For all cases, the size of the simulated lattice was increased until the predicted h and hv at the center of the lattice converged.

Force balance model

The force balance model provides a description of the liquid interface in cases where the Linear Superposition Approximation (LSA) is no longer valid. When the lattice spacing is small, the interface flattens between the spines, and the average liquid height is determined by balancing forces. The capillary force exerted by the spines is matched with the weight of the liquid displaced in the unit cell area A. Assuming a flat interface at elevation \(\overline{h}\), the force balance is expressed as:

This results in a cubic equation for \(\overline{h}\):

The solution to this equation gives the average liquid height \(\overline{h}\), capturing the behavior of the liquid interface under conditions where the LSA model fails. The predicted \(\overline{h}\) is compared with experiments, numerical results, and LSA predictions in the main text, as shown in Fig. 2(a–c). For a cylindrical pillar, α = 0° and Eq. (9) simplifies nicely to

In contrast to the LSA model, the force balance does not account for the valleys and the particular distortion at the lattice edge, which is crucial for manipulation applications.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper. The code for creating an arrangement of truncated conical spines that reproduces a gray-scale image is implemented in Mathematica (Version 13.3). This code and CAD files for 3D printing the devices presented in this paper can be found at https://github.com/GRASP-LAB/3D-printed-spines51.

Code availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper. The code for creating an arrangement of truncated conical spines that reproduces a gray-scale image is implemented in Mathematica (Version 13.3). This code and CAD files for 3D printing the devices presented in this paper can be found at https://github.com/GRASP-LAB/3D-printed-spines51.

Change history

17 July 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-61995-5

References

Loudet, J. & Pouligny, B. How do mosquito eggs self-assemble on the water surface? Eur. Phys. J. E 34, 1 (2011).

Nicolson, M. M. The interaction between floating particles. Math. Proc. Camb. Philos. Soc. 45, 288 (1949).

Vella, D. & Mahadevan, L. The “Cheerios effect”. Am. J. Phys. 73, 817 (2005).

Hu, D. L. & Bush, J. W. Meniscus-climbing insects. Nature 437, 733 (2005).

Peruzzo, P., Defina, A. & Nepf, H. Capillary trapping of buoyant particles within regions of emergent vegetation. Water Resources Res. 48 https://doi.org/10.1029/2012WR011944 (2012).

Peruzzo, P., Defina, A., Nepf, H. M. & Stocker, R. Capillary interception of floating particles by surface-piercing vegetation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 164501 (2013).

Bowden, N., Terfort, A., Carbeck, J. & Whitesides, G. M. Self-assembly of mesoscale objects into ordered two-dimensional arrays. Science 276, 233 (1997).

Whitesides, G. M. & Grzybowski, B. Self-assembly at all scales. Science 295, 2418 (2002).

Boncheva, M. & Whitesides, G. M. Making things by self-assembly. MRS Bull. 30, 736 (2005).

Pelesko, J. A. Self assembly: the science of things that put themselves together. (Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2007).

Poty, M., Lumay, G. & Vandewalle, N. Customizing mesoscale self-assembly with three-dimensional printing. N. J. Phys. 16, 023013 (2014).

Dasgupta, S., Auth, T. & Gompper, G. Nano-and microparticles at fluid and biological interfaces. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 29, 373003 (2017).

Ho, I., Pucci, G. & Harris, D. M. Direct measurement of capillary attraction between floating disks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 254502 (2019).

Delens, M., Collard, Y. & Vandewalle, N. Induced capillary dipoles in floating particle assemblies. Phys. Rev. Fluids 8, 074001 (2023).

Botto, L., Lewandowski, E. P., Cavallaro, M. & Stebe, K. J. Capillary interactions between anisotropic particles. Soft Matter 8, 9957 (2012).

Vandewalle, N. et al. Symmetry breaking in a few-body system with magnetocapillary interactions. Phys. Rev. E 85, 041402 (2012).

Zeng, C., Brau, F., Davidovitch, B. & Dinsmore, A. D. Capillary interactions among spherical particles at curved liquid interfaces. Soft Matter 8, 8582 (2012).

Vinay, T. V., Banuprasad, T. N., George, S. D., Varghese, S. & Varanakkottu, S. N. Additive-free tunable transport and assembly of floating objects at water-air interface using bubble-mediated capillary forces. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 4, 1601231 (2017).

Eatson, J. L. et al. Capillary assembly of anisotropic particles at cylindrical fluid-fluid interfaces. Langmuir 39, 6006 (2023).

Peng, Y. et al. Meniscus-induced directional self-transport of submerged bubbles on a slippery oil-infused pillar array with height-gradient. Langmuir 38, 15001 (2022).

Jiang, J. et al. Directional pumping of water and oil microdroplets on slippery surface. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 116, 2482 (2019).

Xie, G. et al. Continuous, autonomous subsurface cargo shuttling by nature-inspired meniscus-climbing systems. Nat. Chem. 14, 208 (2022).

Zeng, C. et al. 3d-printed machines that manipulate microscopic objects using capillary forces. Nature 611, 68 (2022).

Metzmacher, J., Delens, M. & Vandewalle, N. Ring of capillary actuators as trap, tweezers, and ratchet for floating particles (2024), preprint (Version 1) available at Research Square.

Lewandowski, E. P., Bernate, J. A., Searson, P. C. & Stebe, K. J. Rotation and alignment of anisotropic particles on nonplanar interfaces. Langmuir 24, 9302 (2008).

Cavallaro Jr, M., Botto, L., Lewandowski, E. P., Wang, M. & Stebe, K. J. Curvature-driven capillary migration and assembly of rod-like particles. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 108, 20923 (2011).

Liu, I. B. et al. Elastocapillary interactions on nematic films. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 112, 6336 (2015).

Liu, X., Zhou, W., Tang, F., Zheng, H. & Joo, S. W. Capillary tweezer for programmable droplet manipulation. Sens. Actuators B: Chem. 370, 132380 (2022).

Gennes, P.-G. et al. Capillarity and wetting phenomena: drops, bubbles, pearls, waves. (Springer, 2004).

Lo, L. L. The meniscus on a needle–a lesson in matching. J. Fluid Mech. 132, 65 (1983).

Kralchevsky, P., Paunov, V., Denkov, N., Ivanov, I. & Nagayama, K. Energetical and force approaches to the capillary interactions between particles attached to a liquid-fluid interface. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 155, 420 (1993).

Cooray, H., Cicuta, P. & Vella, D. The capillary interaction between two vertical cylinders. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 24, 284104 (2012).

Paunov, V., Kralchevsky, P., Denkov, N. & Nagayama, K. Lateral capillary forces between floating submillimeter particles. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 157, 100 (1993).

Semprebon, C., Forsberg, P., Priest, C. & Brinkmann, M. Pinning and wicking in regular pillar arrays. Soft Matter 10, 5739 (2014).

Cappello, J., Scheid, B., Brau, F. & Siéfert, E. Bioinspired shape shifting of liquid-infused ribbed sheets. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 120, e2216001120 (2023).

Bico, J., Thiele, U. & Quéré, D. Wetting of textured surfaces. Colloids Surf. A: Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 206, 41 (2002).

Quéré, D. Wetting and roughness. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 38, 71 (2008).

Yang, Y. et al. 3d-printed biomimetic super-hydrophobic structure for microdroplet manipulation and oil/water separation. Adv. Mater. 30, 1704912 (2018).

Jurin, J. Ii. an account of some experiments shown before the royal society; with an enquiry into the cause of the ascent and suspension of water in capillary tubes. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. 30, 739 (1717).

Kralchevsky, P. A. & Nagayama, K. Capillary forces between colloidal particles. Langmuir 10, 23 (1994).

Chan, D., Henry Jr, J. & White, L. The interaction of colloidal particles collected at fluid interfaces. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 79, 410 (1981).

Loudet, J.-C., Alsayed, A. M., Zhang, J. & Yodh, A. G. Capillary interactions between anisotropic colloidal particles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 018301 (2005).

Vandewalle, N. et al. Switchable self-assembled capillary structures. Soft Matter 16, 10320 (2020).

Vassileva, N. D., van den Ende, D., Mugele, F. & Mellema, J. Capillary forces between spherical particles floating at a liquid- liquid interface. Langmuir 21, 11190 (2005).

Dörr, A. & Hardt, S. Driven particles at fluid interfaces acting as capillary dipoles. J. Fluid Mech. 770, 5 (2015).

Dörr, A., Hardt, S., Masoud, H. & Stone, H. A. Drag and diffusion coefficients of a spherical particle attached to a fluid–fluid interface. J. Fluid Mech. 790, 607 (2016).

Zhou, Z., Vlahovska, P. M. & Miksis, M. J. Drag force on spherical particles trapped at a liquid interface. Phys. Rev. Fluids 7, 124001 (2022).

Hunt, R. et al. Drag on a partially immersed sphere at the capillary scale. Phys. Rev. Fluids 8, 084003 (2023).

Sun, Y. et al. Locally reprogrammable magnetic micropillars with on-demand reconfiguration and multi-functionality. Adv. Mater. Technol. 8, 2300773 (2023).

Poty, M., Weyer, F., Grosjean, G., Lumay, G. & Vandewalle, N. Magnetoelastic instability in soft thin films. Eur. Phys. J. E 40, 1 (2017).

Delens, M., Franckart, A., Harris, D. M., & Vandewalle, N. Grasp-lab/3d-printed-spines: Code and stl supporting our article “3d-printed spines for programmable liquid topographies and micromanipulation. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15205890 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This work is financially supported by the University of Liège through the CESAM Research Unit. It is also financially supported by the FNRS CDR project number J.0186.23 entitled “Magnetocapillary Interactions for Locomotion at Liquid Interfaces" (MILLI). D.M.H. recognizes financial support from the National Science Foundation (NSF CBET-2338320).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.D., A.F., and N.V. have developed the original idea of the array of spines. M.D. and A.F. developed the script for designing the spines. A.F. conducted the experiments. M.D., A.F., and N.V. did the theoretical LSA model, and A.F. and D.M.H. did the theoretical force balance model. D.M.H. numerically solved the non-linear Young-Laplace equation. All authors participated in editing the manuscript. N.V. supervised the project and secured funding. M.D. and A.F. contributed equally.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Delens, M., Franckart, A., Harris, D.M. et al. 3D-printed spines for programmable liquid topographies and micromanipulation. Nat Commun 16, 4348 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-59483-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-59483-x

This article is cited by

-

Ring of capillary actuators as trap, tweezers and ratchet for floating particles

Scientific Reports (2025)