Abstract

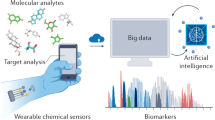

Biophysical signals such as motion and optically acquired hemodynamics represent foundational sensing modalities for wearables. Expansion of this toolset is vital for the progression of digital medicine. Current efforts utilize biofluids such as sweat and interstitial fluid with primarily adhesively mounted sensors that are fundamentally limited by epidermal turnover. A class of potential biomarkers that is largely unexplored are gaseous emissions from the body. In this work, we introduce an approach to capture emission of gas from the skin with a leaky cavity designed to allow for diffusion-based ambient gas exchange with the environment. This approach, coupled with differential measurement of ambient and in-cavity gas concentrations, allows for the real-time analysis of sweat rate, VOCs, and CO2 while performing everyday tasks. The resulting biosignals are recorded with temporal resolutions that exceed current methodology, providing unparalleled insight into physiological processes without requiring sensor replacement over weeks at a time.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Current state of the art in wearable devices enables intimate tracking of biomarkers that are physical, chemical, and hormonal in nature1. Most platforms rely on adhesive approaches that capture analytes, such as sweat, that use physical sensors that rely on electrochemical or photonic interfaces with the skin2. Adhesive approaches are fundamentally limited by epidermal turnover, which results in operational times of around 3 days before the primary interface to the skin needs to be replaced3,4,5,6. Especially for interfaces that collect biofluids such as sweat, operational times are also limited by the capturing volume capability of the device and biofouling of respective sensors7. A biomarker that has only been investigated in a laboratory context because of missing technology that allows for use in the field is gaseous emissions from the skin. Currently, complicated setups that require gas chromatographs and/or airtight sealing against the skin are used in experimentation8,9,10,11,12, making relevant real-world experiments difficult or impossible. Enabling these experiments in a wearable format that is not limited to the lab can yield substantial insights, currently impossible to collect, especially over chronic time scales. Key technological advances that are required include the capability to bring gas analysis into a miniaturized and reusable form factor suitable for a wearable that can easily be worn during many activities and enables continuous sampling of gas emitted by the skin.

In this work, we introduce a concept to sample gaseous emissions from the skin by shaping a 3D cavity that enables continuous gas exchange with the ambient environment and, at the same time, provides the ability to take differential measurements to allow for absolute characterization of the gas in close proximity to the body. We accomplished this by using the continuously wearable biosymbiotic platform characterized extensively by the Gutruf lab, which is defined by wireless recharge at a distance, allowing for 24/7 operation, adhesive-free interfaces with the user, skin-safe substrates, and skin-similar mechanics in a near-invisible-to-user small form-factor5,13,14,15,16 and the flexibility of 3D printing of soft materials to allow for the spatial resolution to shape cavities precisely to feature gas exchange rates that are predictable and consistent even in real-world scenarios. On-body, this device records gaseous biosignals from the dorsal forearm, a widely used location for biosensors7,17,18,19, often covered with dense body hair, which is important in this context because skin-gas excretion collected from this area is of high or acceptable relative intensity compared to other areas to target in wearable form11,17,20,21. Gas emission rates are highest on the head, forehead, and cheek, followed by the palm, lower back, buttocks, and axilla, with significant variation across body regions10,17,22,23,24. The dorsal forearm and wrist provide consistent gas emissions while minimizing user burden, supporting their selection for continuous wearable sensing12,20,25. Together with onboard analysis of the signals, this yields a platform called Diffusion-Based Gas Sensors (DBGS) that provides a high level of temporal resolution and multimodal characterization of physiology.

Results

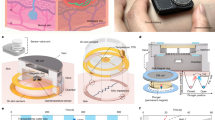

To capture gaseous emissions from the skin, a sealed cavity is required that restricts convective exchange with the ambient gases while simultaneously featuring a capability to diffuse gas emitted by the skin in a controlled manner into the ambient air. This is accomplished with a unique design of a cavity with a leak that is shaped in a way for diffusion to occur without convection arising from ambient air drafts or movements. The cavity features aerodynamic blockages that do not allow for a direct air path of ambient air to disturb the gas inside the cavity. As shown in Fig. 1a, this principle allows for diffusion-based gas exchange with the ambient air. It allows for gas to enter the cavity and for sensors to measure the inside and outside concentration of that gas, which then enables a differential measurement from absolute gas concentration numbers in the cavity. Because diffusion is based on the inside and outside gas concentration, rates of emission from the skin can be calculated, and convection is minimized because of the aerodynamic design of the cavity. Practically, this can be accomplished with 3D printing and a pillared structure of the cavity as shown in Fig. 1b. This configuration provides a leak to the ambient air to enable diffusion. This architecture interacts with the target eccrine sweat glands on the dorsal forearm without the need to prepare skin prior to or post-sweat collection, which eliminates selection of hair-free or alcohol-rubbed skin segments2,3,7, and I2C data lines that connect the sensors travel in a strain-mitigating serpentine pattern to aggregation by the microcontroller. The cavity also features a port and a housing at the top that allows for the mounting of SMD gas sensors, which sample gas concentration inside and outside the cavity. Important to note is that the sensors are sealed to the respective air volumes. Complete circuitry makeup of the biosymbiotic DBGS is shown in Supplemental Fig. 1. Figure 1c illustrates skin-gas diffusive mechanisms where gaseous molecules either diffuse directly through skin, or accumulate in the eccrine sweat and sebaceous glands to then evaporate when exposed to ambient conditions8,9,20,26, In green, the cross-section of the sensing volume illustrates the accumulation of various skin gases where a dual-gas sensor samples interior and exterior concentrations.

a Schematic outline of operating principle. Gaseous emissions (blue) originating from skin are captured by a DBGS cavity (green) with two layers of pillars that facilitate gas transfer to the ambient air via passive diffusion and minimal convection. A dual sensor system facing the cavity (red) and ambient air (black) captures the difference between cavity and ambient gas. b Photographic image of the realized FDM printed cavity with electronics installed. c Rendered image illustrating gas diffusion through epidermal tissue, originating from the blood vessels and sweat glands. H2O Water, CO2 carbon dioxide, C2H6O ethanol, VOC volatile organic compounds.

Characterization and simulation of diffusion cavity

Humidity as a characterization gas is utilized because sweat rate and epidermal water loss are important biomarkers that are well characterized in literature2,3,7,27,28,29. Tracking fluid loss in sweat provides clear insight into hydration status3,7,30,31,32,33, is used to evaluate psychological status34, and offers advanced monitoring of dermatologic conditions such as atopic dermatitis and plaque psoriasis35.

Also, highly accurate humidity sensors in small form factors with low power consumption are available in SMD packaging, enabling simple proof of principle of the concept and detailed investigation into the performance of the cavity in various scenarios. To characterize the performance of the diffusion cavity, a test stand is utilized that allows for the creation of humidity analogous to skin. Figure 2a showcases the experimental setup, which is a heated plate operating at skin temperature, including a small orifice tube that represents a collection of sweat pores. The cavity is then placed on top of the outlet and subjected to a range of flow rates and ambient humidity conditions. Figure 2b shows the high temporal resolution of this sensing approach, capturing changes in visible and, importantly, non-visible sweat in the range of seconds, which points to a temporal resolution and fidelity that surpasses current sweat rate monitoring using liquid sweat routed through microfluidic channels. Step response to a 0.5 μL volume results in a 24.58% increase in interior humidity reading over 5 s (slope of 4.97%/s), while the comparatively small slope (−0.38%/s) of the return-to-baseline humidity values over 48 s is observed. A distinct change in slope from quasi-linear to exponential demarks full evaporation of the fluid and clearing of the cavity humidity. Figure 2c shows diffusion characteristics in increasingly humid ambient conditions, using steady flow rates of 0–7 μL/min representing the physiological range of sweat. Because diffusion is reliant upon the gas concentration gradient from inside the cavity to outside per Fick’s diffusion laws36, higher sensitivities can be accomplished at lower ambient humidities, as shown in these results. However, even at extreme humidities, as seen in real-world experiments, the sensitivity is high enough to distinguish a variety of physiologically relevant flow rates of sweat in tested conditions. Important to note is that the cavity, with a leak area of 60 mm2, representing the sum of all opening areas to ambient air, is designed to allow for diffusion that is compatible with physiological conditions of sweat generation across a wide range of applications. This can be calculated analytically and can be tuned for the target use case by changing the geometries of the leak area.

a Experimental setup illustrating simulated sweat response. RH relative humidity. b Example step response of relative humidity values captured from ambient-facing and cavity-facing sensors. c Humidity differences plotted against various ambient humidity values at increasing artificial sweat flow rates. d Fluid dynamic modeling of diffusion cavity (Left) bottom view in-cavity windspeed in response to a 30 mph wind. (Right) side-view of cross section of cavity showing aerodynamic performance in decrease in windspeed inside the engineered chamber. e bar graph illustrating the average change in windspeed from input to in-cavity averages at sensor interface (black) and total sensing volume (red).

An important potential downside of this sensing method is convection through ambient air currents, as they occur in outdoor activities such as bike riding and other high-wind scenarios where the gas in the cavity can get displaced by incoming air, which would be difficult to compensate for in a wearable device. The cavity geometry design is created to aerodynamically block incoming air currents and deflect outside air in a variety of ambient air speeds around the cavity, yielding diffusion-dominated air exchange with the outside air. Designs are shaped by fluid dynamic modeling as shown in Fig. 2d. Here, an ambient airspeed of 10 and 30 mph (30 mph shown) is applied in simulation. Visible from the flow diagram is effective deflection of the incoming air and very little air movement within the cavity. These changes in ambient speeds are represented explicitly in Fig. 2e. The data shows that average interior windspeed at sensor interface (black) is decreased from input by 94.27% and 96.31% for 10 and 30 mph respectively, and averaged windspeed in the total sensing volume (red) decreases by 85.7% and 89.1%, respectively. This effective blockage of air movement at extreme speeds ensures the gas exchange is diffusion-dominated as intended by the design. These results are further supported by modeling of turbulent airflow, shown in direct comparison to the above results in Supplemental Fig. 2. In this paradigm, it is clear there is no preferential directionality to oncoming air stream, and showcase that DBGS sensing is effective in a variety of ambient conditions.

On-body results in controlled environments

Based on characterizations of the ex vivo results, computation of sweat rate based on the difference in ambient and in-cavity humidity is accomplished. The relationship is described by a polynomial fit of the data displayed in Fig. 2c, yielding Eq. 1.

The accuracy is tested against gold standard in sweat rate tests with highly absorbent cloth swabs cut with a surface area of 30 mm2 that matches the exposed to skin area of the DBGS, as outlined by Fig. 3a. The test features a stationary bike cycling exercise for 40 total minutes, with 30 min in heart rate (HR) Zone 3 (70–80% of maximum)37, which is chosen to introduce a steady sweat rate after a warm-up. Swabs are applied and weighed on a precision scale to extract sweat rate at 2-min intervals, which provides the gold standard to benchmark DBGS. Data collected from the subjects show a very good agreement of sweat rates collected by swabs versus sweat rates computed using DBGS, as shown in Fig. 3b. Important to note is that the temporal resolution of this method is very high compared to liquid sweat rate calculated by manual swabbing7,38,39, colorimetric epifluidics18, or even active electrochemical29 and epifluidic devices40. The stability of the DBGS sweat tracker is tested against ambient drafts in Fig. 3c. Here, fans with varying speeds simulate outdoor conditions in a controlled lab environment. Predictably, the increased air speed has an influence on convective cooling and, by extension, sweat rate31, which is shown both in swab samples and in DBGS, which correlate throughout the test, highlighting the robustness against ambient drafts. Further demonstration of draft tolerance is shown in Supplemental Fig. 3, where a subject maintains a nearly undisturbed (SD 0.00217 µL/cm2/min) sweat rate during targeted intervals of 5, 10, and 30 mph during a downhill cycling activity (ambient temperature: 50 °F, relative humidity 20.3%).

a Schematic outline of stationary cycling tests. DBGS diffusion-based skin gas sensor. b Example time-synced data from Subject 1 (male, heavy body hair), showing absorbent swab sweat rates compared to continuous data streams from the DBGS with no ambient draft. c Example time-synced data from Subject 2 (male, light body hair), showing absorbent swab sweat rates compared to continuous data streams from the DBGS with variable drafts. d Coefficient of variation (COV) and Bland–Altman plots relating temporally matched swabbed sweat values with the averaged sweat rate for the 2-min period corresponding to each swab’s contact with skin. R2 coefficient of determination, RMSE root mean square error, RPC reproducibility coefficient, CV coefficient of variance, SD standard deviation.

The combined results of sweat rates from four subjects over seven total trials, with direct comparison to gold standard each 2 min yields statistical analysis, giving a Pearson’s correlation and a Bland–Altman plot shown in Fig. 3d with r2 of 0.75 (R = 0.866) and reproducibility coefficient (RPC) of 48. Anthropometric data of subjects is shown in the “Methods” section and with individual r2 values ranging from 0.69 to 0.78 (see Supplemental Fig. 4). Recent studies on wearable sweat rate capture that provide similar statistical analysis rely on either a single bulk comparison to gold standard at activity end, showing R = 0.97 (r2 = 0.81), or gold standard comparison each 10 min showing general qualitative agreement41. Furthermore, DBGS results compared per subject on nonconsecutive days generate a repeatability correlation coefficient (R). Supplemental Fig. 5a shows schematically how data collected from the subjects are analyzed for correlation, and Supplemental Fig. 5b shows resulting R of 0.986 and 0.979 with p < 0.0001 are observed for subjects one and two over 240 datapoints representing the average of every 10 s of readings per test. This approach surpasses the current state-of-the-art, and the robustness of the results further corroborates the reliability of this platform.

Performance in athletics and daily activity

Tracking sweat rate in daily activity is demonstrated with experiments reliant on chronic stability and performance, otherwise difficult or impossible to capture with current technology. The skin-seal of the cavity is robust and able to withstand a direct axial load of 1.53–2.03 N before sensor readings lose fidelity, shown in Supplemental Fig. 6. In cases where the cavity directly experiences force exceeding 2 N, the elastic properties of the biosymbiotic platform immediately reacquire skin-seal upon load termination. Important to note is that DBGS sensors integrate seamlessly with biosymbiotic electronics previously developed by the Gutruf lab, enabling continuous operation without the use of adhesives5,13,14,15,16. The full system description is shown in Supplemental Fig. 7, with assembly steps outlined in Supplemental Fig. 8.

In Fig. 4a, an indoor weightlifting session is recorded, featuring periods of warm-up, rest, and lifting with variations in heart rate tracked by gold standard devices and sweat rate characterized by DBGS. Sweat rate with respect to active lifting work and rest, consistent with expected physiological sweat responses, is shown in this demonstration. Sweat rate slowly rises during the warm-up period from its rest value to 88.7% of maximum during the session. Following a brief rest, a localized maxima and minima, spaced 1 min apart, represent a localized sweat rate differential of 0.4404 µL/cm2/min from warmed-up baseline. The subject performs four sets of 3–5 repetitions of heavy (85% of one rep max) deadlift with 3–5 min of rest between sets. The observed sweat rate during the lift does not fluctuate, with a standard deviation of all periods in red relative to the warmed-up baseline of 0.0426 µL/cm2/min, and an average standard deviation during these periods of 0.00235 µL/cm2/min. The majority of interesting information occurs in the periods immediately preceding or following the lift, where instances of a drop in sweat rate with a sharp incline immediately prior to the lift (second and third lift), and two instances (first and last lift) where sweat rate spikes immediately following the lift42. Additionally, Supplemental Fig. 9 illustrates the same phenomenon of sweat rate lagging the activity in a separate strength-training experiment. In this case, pushups are performed from rest with hands stationary during the exercise. Observed is an increase in sweat rate lagging the period of effort. These temporal dynamics are not shown in the literature and only visible because of the high temporal resolution of the system. Repetition of the experiment in Fig. 4a demonstrates similar sweat responses with standard deviations remaining low at an average of 0.00323 µL/cm2/min. Supplemental Fig. 10a shows original and repeated experiments in direct comparison.

a Sweat rates during weight training measured with biosymbiotic DGBS with heart rate benchmark. b Biosymbiotic DBGS and heart rate for stationary cycling for a total of 30 min indoors, followed by rest to sweat cessation, with subsequent stationary cycling outdoors for a total of 30 min captured in one continuous activity. c DBGS and Heart Rate for a tennis match. d Continuous chronic data collection of one work week recording of sweat rate using the biosymbiotic DBGS with activity marked by icons. Dumbbell: Weightlifting session. Bike: Cycling activity. Shoe: Running activity. Tennis Racquet: Tennis activity. e Sweat response to ingestion of food covered in hot sauce. The gray line indicates the start of food ingestion. f Sweat rate cessation following exercise completion. g Illustration of epidermal thermography capturing the wake-up period with corresponding sweat rates.

Due to the platform’s ease of use, bypassing skin preparation or device handling between experiments, sweating in dynamic environments can be investigated. To test observable sweat rates in contrasting environments, two identical stationary bike experiments are performed back-to-back in an indoor and outdoor environment. Sweat response curves shown in Fig. 4b follow a similar trend to that of Fig. 3b, c, which utilize a similar protocol, modified to decrease total time by 10 min in HR Zone 3 per test. Following completion of the indoor portion of the experiment, the subject rests until baseline sweat and heart rate readings return, and the experiment is repeated outdoors. The peak measured sweat value in this test is 45.9% less for the outdoor sweat portion than for the indoor portion. This change in response to an identical experimental protocol has many causes—increased evaporation due to low humidity of a desert environment, acute dehydration43,44, decreased power output at the same HR intensity due to fatigue, and increased core body temperature39. To ensure that the experimental outcomes are repeatable, the experiment is repeated with outdoor trials completed first in the sequence, results shown in Supplemental Fig. 11. In this case, the same trend is observable, where outdoor sweat rates are substantially lower than indoor sweat rates. This experiment is repeated months later, resulting in identical trends, shown in Supplemental Fig. 10b. In the repeated experiment, maximum sweat rate is 26.3% less and the average is 25.7% less for indoor than original experiment, and outdoor maximum rate increases by 19.9% and average sweat rate increases by 34.03%, attributable to the change in ambient humidity, which affects sweat rate45. Sweat rates correlate to environmental changes from indoor to outdoor cycling, not ambient wind conditions, evidenced by stationary cycling tests utilizing airflow changes using a fan shown in Fig. 3c. This is further supported by tests isolating sweat rate and wind speed in field conditions shown in Supplemental Figs. 3 and 9, and Fig. 3c.

Because of the high temporal resolution, high fidelity sweat rate insight can be recorded for dynamic competitive sports such as outdoor tennis. Over an 80-min bout, three distinct phases of the session are identified, shown in Fig. 4c. The subject performs an extended 22-min warm-up terminating in high intensity (>90% of maximum heart rate), which matches a steady rise in sweat rate and peak after heart rate begins to decrease. Instantaneous sweat rate increase during rest period immediately following high-intensity exercise is minimally characterized in literature42,46, however, it is frequently observed in our experiments, and is a classic thermoregulatory response in eccrine glands to enhanced body heat39, which requires an enhanced sweat rate to combat the delayed increase in body temperature due to exercise. After a short break, skill work consisting of lower intensity drills (21 min) shows a reduced (25.2% of maximum) sweat output. Sweat rate is observed to increase in the following matchplay section. Matchplay is simulated by a series of two “set tiebreakers” to 7 points and one “match tiebreaker” to 10 points. Heart rate trends indicate variability in intensity of these bouts, with a steady rise in sweat rate to the experiment maximum of 0.9681 µL/cm2/min. Supplemental Fig. 10c repeated experiments show that the absolute maximum sweat rate is higher during the warm-up phase by 57.1%, and average sweat rate during skill work is 31.2% higher as well. While individual response differs in rate because tennis skill work intensity is difficult to repeat exactly, trends for both experiments follow for each phase of training.

DBGS enables chronic data collection facilitated by biosymbiotic electronics and ultralow power (<20 mW) consumption at wake and transmission, shown in Supplemental Fig. 12, for an unexplored range of biomarkers. We demonstrate this through continuous data collection over 135 h (5.5 days). In the graph shown in Fig. 4d, green indicates periods of wake where the subject was not performing a targeted sweat-inducing activity, such as going about daily activities at work, home, and elsewhere. A zoomed-in example of a typical 12-h wake period encompassing a normal work day is shown in the figure inset, where minor spikes in sweat rate occur semi-regularly. These may be attributed to any number of stressors, such as the morning commute, workplace demands, or even engaging or stressful social scenarios47,48,49. In blue, periods of sleep are shown. The typical adult experiences “insensible fluid loss” otherwise known as difficult-to-measure fluid loss through ratios of roughly equal to 3:1 parts integumentary and respiratory pathways, which can modulate throughout the diurnal cycle50,51. This is potentially shown during the visible signal perturbations during sleep, starting at the 64 h mark. In red, many instances of activity ranging from weightlifting, running, cycling, and tennis are shown, often with multiple occurrences in a single day. Each of these temporally matched activities is recorded using the same wearable device, without the need for recharge or replacement of constituent components. Variations in intensity and duration are shown, with rapid return to baseline.

As this sensing method does not require the presence of visible liquid sweat, gaseous humidity characterizations of subtle physiological events may be captured. This is demonstrated in Fig. 4e, f. Figure 4e shows a subject’s response to the ingestion of spicy food. In this experiment, bland food supplemented with 1 million Scoville hot sauce is ingested after a period of nonstimulated physiological attenuation. As this is an uncomfortable experience for the subject, the first segment, shown in blue, may be representative of anticipatory anxious sweat response52, which levels off in the 5 min prior to ingestion. In the minute following ingestion, represented by the vertical gray line, the subject experienced a rapid spike in sweat rate, achieving the maximum reported value for this experiment of 0.0482 µL/cm2/min. Important to note is that the sweat rate was measured on the forearm, a location not typically associated with visible sweat induced by spicy food53. This was repeated and is shown in Supplemental Fig. 13a. Specific features are labelled for comparison. Point 1 shows a sweat rate local minima for both graphs, and point 2 illustrates a consistent increase, with 77.1% and 88.9% increases at peak from the average reading of Point 1. Point 3 shows a secondary sweat peak, occurring within 6–7.5 min of the peak at Point 2.

Figure 4f explores cessation of sweat in uncontrolled ambient environments. The activity shown at approximately 58 h in Fig. 4d provides context, where the subject engaged in a trail run activity outdoors. Displayed are the last 5 min of this activity, where a localized sweat peak of 0.3031 µL/cm2/min tapers downward, initially with a generally consistent downward slope of 0.07074 µL/cm2/min/min over 4 min, followed by a 0.003038 µL/cm2/min/min downward trend for the following 30 min, matching reported trends showing it takes roughly 4 min for the slope to level off54. This functional example provides context and potentially a proxy metric for the rate at which an individual’s sympathetic nervous response deactivates39,55 and core body temperature returns to baseline39. When repeated, virtually identical sweat response occurs, evidenced by the results of Supplemental Fig. 13b. These results differ slightly in sweat cessation rate with a lower slope of 0.00401 µL/cm2/min/min.

Temperature can be used as a representative biomarker to illustrate circadian rhythm56,57. Figure 4g uses this corroborating metric of skin temperature to show increases in sweat rate in conjunction with modulation of sleep state. Core body temperature usually locally spikes upon waking and remains mostly constant through the day until temperature drops prior to and during sleep15,56. Thermography is performed using the in-cavity facing gas sensor. A baseline with a steady low-deviation-from-mean (0.00351 µL/cm2/min) is observed 8 min plotted prior to wake. The subject maintains a regular sleep schedule, waking at 6:45 am. The first spike shown in green temporally matches this alarm time within 20 s, which represents a linear increase of 0.001266 µL/cm2/s spread over 35 s, initially peaking at an instantaneous reading of 0.0608 µL/cm2/min. Steady-state sweat readings following stabilization after the peaks shown in “awake” show a 46.1% increase in mean sweat rate during “active” (red) from “asleep” (blue), and a 38.6% increase in standard deviation from mean sweat rate. When repeated, sweat rate and temperature trends remain the same, shown in Supplemental Fig. 13c. Both subjects’ skin temperature drops just before the waking period and then increases upon activity both sweat rates spike during the waking phase.

Multimodal skin gas characterization

While experiments in Figs. 3 and 4 focus on the characterization of humidity emitted from skin and sweat, the principle of DBGS extends to the characterization of any gaseous emission from the skin. This is demonstrated by the characterization of CO2 and VOC gases in real time in vivo. CO2, along with H2O, constitutes the primary waste products from all oxygen-mediated reactions in the body. Utilizing a similar sensor and cavity architecture, differential signals in skin-emitted CO2 and ambient air in response to various stimuli can be captured. CO2 emissions captured via transcutaneous pathways are already used in clinical practice12,58,59,60, for example, to measure ventilation status in neonates61. Similarly, VOC’s, an aggregate term for volatile organic compounds, consists of substances such as ethanol, ammonia, acetone, toluene, and many more10,11,22. VOC’s are associated with the metabolism of various substances and are released via aggregation in sweat and sebaceous glands and excreted with perspiration and sebum. They also directly diffuse through layers of the dermis from the vasculature8,9. VOC monitoring can be used for monitoring of diabetes62, stress63,64,65, and metabolic or hepatic disorders34,66. Most, but not all, studies evaluating VOC emissions from skin utilize mass spectrometry to quantify the specific VOC compounds emitted from skin, with highest typically hydrocarbons, aldehydes, and ketones, with the ketone acetone specifically being the highest or second-highest reported individual VOC11,67,68. In this study, only nonspecific aggregate VOC dynamics are evaluated in response to various stimuli. For the following experiments, CO2 readings and VOC readings are calibrated analog to the procedure described for sweat rate. Figure 5a details the experimental paradigm to achieve physiological levels of CO2 in benchtop testing. A mixture of CO2 and ambient air is titrated to test concentrations from 0.14% to 1.03%. This mixture feeds into a semisealed chamber with a small opening to the DBGS cavity volume and a large opening to ambient air, ensuring diffusive dynamics with minimum gas pressure into the DBGS cavity during calibration measurements. Detailed descriptions of this process are provided in the “Methods” section. While ambient changes in CO2 are not significant in this experiment, their effect is accounted for in differential measurements between in-volume and ambient sensor readings. The concentration of CO2 in the gaseous mixture plotted against sensor differential is shown in Fig. 5b, showing a linear relationship with concentration. Figure 5c shows settling times for various concentrations of CO2 in a gaseous mixture. Peak values are achieved within 10 s of concentration change, with a typical response time under 5 s for CO2 gas mixtures.

a Schematic outline of benchtop experimentation to yield calibration data for DBGS CO2 measurements. b Calibration results from increasing CO2 mixtures by volume against differential sensor readings. R2 coefficient of determination. c Time to achieve stable sensor readings. d Schematic outline of benchtop experimentation to yield calibration data for DBGS VOC measurements. VOC volatile organic compounds. e Calibration results for increasing VOC mixtures by dilution of 91% ethanol with distilled water. R2 coefficient of determination. f Required time to achieve 63% (black, t63) and 95% (red, t95) of maximal response to increasing concentrations of VOC. g Top: Response to stationary bike exercise. Bottom: Repeated experiment. h Top: Response to alcohol ingestion Bottom: Repeated experiment. The grey bar indicates ingestion time. i Top: Response to neuropsychological mental-fatigue test, A–X continuous performance task (AX-CPT). Bottom: Repeated experiment. Grey bars indicate the start and end of the test.

Figure 5c details the experimental paradigm to achieve physiological levels of VOC in benchtop testing. This methodology uses mixtures of 91% isopropyl alcohol (IPA) with distilled (DI) water to achieve the very low VOC concentrations present in skin at rest. VOC and DI water mixture is drop-cast onto a warmed plate into the DBGS VOC cavity, facilitating emissions at a physiologically relevant rate22,25,67. Detailed descriptions of this process follow in the “Methods” section. Sensor output plotted against the logarithm of VOC concentration is shown is Fig. 5e, showing a linear relationship to VOC emissions of 0 ppb to 10,000 ppb. Sensing response is robust, with the longest time to achieve 95% of maximal response at 14 s for concentrations of 25 ppb, shown in Fig. 5f.

Efficacy of the sensing approach is tested with a stationary bike test similar to those presented in Fig. 3a, with a schematic outline shown in Supplemental Fig. 14. Here, swabs are replaced with CO2 and VOC DBGS sensors. Results are shown in Fig. 5g top and bottom panels. Trial 1 and 2 results show that sweat rate and CO2 both increase during steady-state exercise, with CO2 staying elevated above baseline. VOCs follow a similar trend, with all modalities showing near or above 100% increase from baseline to the peak (CO2 153.4%, VOC 99.8%), reaching nearly 200% for sweat (198.01%) during Trial 1. Trial 2 shows clear repeatability of results, with a higher steady-state VOC increase from baseline (142.2%), and only slightly lower sweat (189.3%) and CO2 (132.4%) responses. During steady-state exercise, trends of increasing H2O and CO2 occur due to aerobic metabolism26,69. Literature suggests this trend will appear in generalizable VOC metabolism during exercise, given a temporally sensitive collection modality70,71, with the most likely contributors being increases in Acetone and Isoprene production67. All trends are shown in the reported data.

A strength of this approach is the capability to capture multimodal emissions in the same spatial location. Stressors such as alcohol metabolism produce H2O, CO2, ketone bodies, and many other VOCs72, and ethanol in the bloodstream, which diffuses to the skin through previously described mechanisms. Previously published works on the impact of alcohol ingestion on sweat rate describe a minor or minimal39 increase, with a characteristic temporal spike in sweat rate 10–15 min after ingestion of a 0.36 g/kg of subject body weight alcohol mixture73. Also described in the literature upon ingestion of alcohol are measurable changes in VOC emissions from the skin22,25. In Fig. 5h, we observe these prior described physiological effects. Specifically sweat modulation consistent with the results of Yoda et al.73, are present in Trial 1 and 2 (black arrows). Reportable VOC trends similar to those captured via an over-ear ethanol sensor22, and similar-in-effect to a “bio-sniffer”25 where ingestion of alcohol causes a time-delayed reaction of roughly 10–15 min where VOC readings begin to increase drastically. Alcohol metabolism, plus the increase in blood alcohol levels, directly influences the production of transdermal VOC emission, specifically breakdown to acetaldehyde yielding increased acetone levels via indirect effects on lipid metabolism11,22,25,72, additionally non-metabolized ethanol in the bloodstream affects VOC emission. These processes are shown in the data, where the highest blood alcohol concentration presents a spike representing a 171.2% increase (region between 1st and 2nd red arrow) in VOC emission from baseline of the 5 min before ingestion, and associated metabolic processes following this spike keep the VOC trend elevated at an average of 159.8% from baseline. Skin CO2 emission in response to alcohol is uncharacterized in literature, however work related to pulmonary function measured through spirometry suggests that alcohol ingestion suppresses the function of this system74,75, which would yield higher CO2 concentrations in the bloodstream. This is corroborated by our experimental results, in which CO2 skin emission is significantly increased by 22.1% (blue arrow) in Trial 1, starting 10 min following alcohol ingestion and peaking 2.5 min later. Trial 2 shows a lower slope, but a similar phenomenon, where the CO2 peak occurs 12 min after ingestion (shown by the blue arrow), with a percent change from baseline of 4.2%. Clear indication of alcohol metabolism is shown in both reported results, with temporally matched peaks occurring within 30 s in independent testing, showcasing the DBGS platform’s strength in capturing discrete physiological phenomena with high temporal resolution.

While apocrine sweat glands are typically associated with the hyperhidrosis related to psychological stressors, eccrine sweat glands, such as those found in the dorsal forearm, are still upregulated by hormonal influences, namely catecholamines, which act in response to acute stress55. Because of the high fidelity of the sensing approach, subtle changes in physiology in response to mental fatigue can be captured. Figure 5i shows multiple subjects’ responses to the AX-continuous performance Test (AX-CPT), described by Marcora et al.76, which induces mental fatigue by requiring sustained attention, working memory, response inhibition, and error monitoring76,77. This is accomplished by demanding focus through subjects accurately identifying a correct letter-pairing while filtering out distractors, with performance metrics related to latency and response accuracy as an output. In literature, increases in heart rate on average when compared to neutral stimuli are elevated, indicating an increased physiological demand. In Trial 1, sweat rate markedly and continually decreases from baseline, a difference of 53.82% between start and end (gray lines) of the AX-CPT and recovers immediately following. Trial 2 shows qualitatively a similar trend as CO2 in Trial 1 increases 17.01% from baseline at the highest (1st blue arrow), then drops to 30.3% below baseline (2nd blue arrow). A similar phenomena occurs in CO2 response during Trial 2, where the first blue arrow shows a peak 3.85% higher than baseline, and second arrow a 1.4% decrease. Red arrow 1 in Trials 1 and 2 points to VOC peaks with subsequent dip, temporally matched to AX-CPT test stressors (18.5% decrease from preceding 5 min of baseline in trial 1, 2.5% decrease in baseline in trial 2), and red arrow 2 shows signal recovery and eventual peak occurring within 1.5 min of each other, 6 and 4.5 min before termination of data collection respectively for Trial 1 and 2. Notable is the similar trend of sweat rate and CO2 profiles compared to alcohol ingestion, with a positive VOC inflection at the start of the test indicating an initial stress response. Only three papers on VOC excretion in response to mental stress exist63,64,65, with significant variance on the most strongly implicated specific VOCs. However, all are in agreement that VOC content will increase in response to stress.

Discussion

The present study introduces diffusion-based gas sensors (DBGS) for wearable applications, which provide high temporal resolution and multimodal gas sensing capabilities for continuous monitoring of gaseous emissions from the skin over extended periods. These sensors offer an enhanced approach to physiological monitoring by enabling the detection of differential and temporal signatures in response to various stimuli, such as exercise, alcohol intake, and mental load, that traditional methods cannot capture. Multimodal sensing ability enables dissection of physiological events through rate-dependent observation, such as the rise of all emissions (VOC, CO2, and sweat rate) in aerobic activities and metabolically driven responses that yield elevated rates of one metric. A detailed synopsis of DBGS performance against other skin-gas tracking literature is given in Supplemental Table 1. The capability of DBGS to capture real-time gas emissions allows for detailed observation of physiological processes in natural settings, offering substantial insights through casual observation. This capability is demonstrated through the detection of subtle physiological responses to mental stress, exercise, and other daily activities, revealing complex interactions between physiological states and gas emissions that have not been previously characterized. Furthermore, exploring multiple gas emissions, including volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and CO2, presents a promising avenue for developing unexplored biomarkers that can provide real-time assessments of physiological status. This approach could lead to more comprehensive health monitoring systems that integrate into daily life without requiring user maintenance, enhancing user compliance and enabling chronic monitoring spanning weeks or months without interruption. The findings suggest that DBGS technology, designed to uncover mechanisms of gas emission by the body, could be a valuable tool in advancing digital medicine, with potential applications ranging from sports performance optimization to stress management and chronic disease monitoring. Limitations of the technology are related to diffusion dynamics, which are determined by the concentration gradient of the cavities, which may limit accuracy in, for example, extremely humid environments and related tradeoffs in dynamic range and sensitivity when choosing the total leak area. Future work could focus on device performance when subjected to a variety of metabolic conditions, such as exercise dynamics typically captured by a metabolic cart, dietary influence on VOC production, including insight into progression of disease paradigms such as diabetic ketoacidosis. Overall, this work highlights the potential of DBGS to significantly impact wearable health monitoring by providing high-resolution, multimodal insights into human physiology, paving the way for increasingly personalized health management.

Methods

Flexible circuit fabrication

Flexible circuits, designed in AutoCAD 2021, were externally manufactured (PCBWay, FlexPCB 413) and laser-cut using an LPKF Protolaser U4. These panels consisted of 12.5 µm Polyimide, 15 µm Adhesive, 12 µm Copper, 25 µm Polyimide, 12 µm Copper, 15 µm Adhesive, and 12.5 µm Polyimide. Following the laser cutting, the PCBs were cleaned using a commercial ultrasonic cleaner (Vevor, 2 L) for 2 min in flux (Superior #71, Superior Flux and Manufacturing Company), then rinsed with deionized water. The components, all commercially available, were manually placed and reflowed using low-temperature solder paste (Chip Quik, SMD291AX).

Circuit design and fabrication

A serpentine-shaped dipole antenna tuned to resonate at 915 MHz was assembled with a full bridge rectifier, using hand-placed commercially available components and reflowed with low-temperature solder paste. The rectifier incorporated low-forward-voltage Schottky diodes (Skyworks, SMS7630-061) and a smoothing capacitor. An exposed copper strip node enabled direct connection to a 3.7 V battery, with capacities ranging from 30 mAh to 100 mAh (BIHUADE 400909, CBB B083NWXLTK), charged through harvested energy. Device power was controlled by a single-throw single-pull switch (CUS-12TB). To ensure stable operation and protect against overvoltage, a 3.3 V low-drop-out (LDO) regulator supplied power to the microcontroller. The Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) microcontroller System on a Chip (SoC) (DA14531) was programmed by attaching flexible wires (Calmont) to General Purpose Input/Output (GPIO) pins designated for SW_CLK and SW_DATA, using Dialog’s SmartSnippet Studio software. The BLE SoC communicated via I2C with the dual-gas sensor setup through a custom breakout node that ascended a serpentine vertical gradient. This dual-gas sensor system featured a sensor footprint with I2C addressing pins properly set to the required voltages on both the top and bottom layers of the flexible circuit board. 4.7 kΩ resistors were connected in parallel to the communication lines and input voltage. Data transmission occurred over the BLE protocol at 2.45 GHz using an external chip antenna (YA-GEO, ANT1608LL14R2400A). The gas-sensing modalities did not employ any onboard filtering. Assembly steps are illustrated in Supplemental Fig. 8a.

Biosymbiotic integration of electronics

2D mesh drawings were exported from AutoCAD and imported into 3D modeling software (Autodesk, Fusion 360) for extrusion. The resulting models were then exported as Stereolithography (STL) files and brought into 3D slicing software (Prusa3D, PrusaSlicer), which converts the models into machine code compatible with a 3D printer. A fused deposition modeling printer (Creality, CR-10S) was modified to include an all-metal direct drive extruder (Creality, Sprite) and equipped with an automatic bed-leveling unit (Antclabs, BLTouch). TPU filament (NinjaTek, NinjaFlex) was printed at a speed of 18 mm/s, with the extruder set to 225 °C and bed at 45 °C. A finalized 3D printed biosymbiotic mesh structure is shown in Supplemental Fig. 8b.

Diffusion-based gas sensor cavity design and biosymbiotic integration

A 12 × 12 mm square was created as the base of the DBGS to interface with the functional unit of previous biosymbiotic device designs. This was drawn in AutoCAD 2021 as the base geometry of the gas cavity. Aligned with the exterior perimeter edge, twenty rectangles of dimension 1.5 × 1.5 mm were uniformly added with 0.5 mm of spacing between them. An inner section, comprised of 12 rectangles of dimension 1.5 × 0.75 mm, we placed directly in the open space between outer rectangles, spaced 0.5 mm apart. The interior perimeter was defined by a square whose perimeter aligned with the exterior edges of the interior rectangles. This file was exported in.dxf format to Autodesk Fusion 360, where the base geometry was extruded 0.45 mm. Each rectangle was extruded 6 mm, and a new sketch was generated on the top to include a 144 mm2 square, also extruded to 0.45 mm to seal the chamber. A final sketch was generated on this monolithic block, to include a square centered at x and y centroid, of dimensions provided by manufacturer datasheet of the various sensors used. The square was offset by 0.1 mm in the x and y directions to account for print imperfections. This square was used to create a cut in the center of the top covering. Additionally, an arc structure was created to provide stability to relatively long-distance serpentine interconnects between electronics, which was lofted along the arc from 0.45 mm to 6 mm. The completed geometry file was exported as a stereolithography file and imported into a 3D slicing software (Chitubox Basic). Contrary to past biosymbiotic device structures, this component is printed utilizing light-sensitive UV resin (UltraFast, UltraFlex) in a stereolithography-capable printer (Phrozen Sonic Mega 8k). The geometry file was sliced at 0.16 mm layer height, with a bottom layer count of 8, bottom exposure time of 15 s, and normal layer exposure time of 2.1 s. Lift speed and distance were 100 mm/min and 4 mm, respectively. After printing, cavities were cleaned in 90% Isopropyl alcohol in a wash and cure station (Anycubic Wash and Cure). Once cleaned and cured, the cavities were adhered to a biosymbiotic mesh via UV-glue (Damn Good, 20910DG) and exposed to UV light for 5 min.

Electronics integration with biosymbiotic structures

Electronics, as described in “Circuit Design and Fabrication,” integrate with biosymbiotic platforms by an FDM printed nonconductive thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU) (NinjaTek, NinjaFlex) of shore hardness 85 A in a 0.45 mm thick device housing with 0.2 mm walls printed directly into the biosymbiotic mesh structure. The device housing features a 0.1 mm offset to fit the assembled device footprint. Assembled dual-gas sensing nodes had their perimeters lightly coated in UV-glue (Damn Good, 20910DG), and were press-fit into the cavity opening as designed. This node was exposed to UV light for 5 min to fully bond the device to its cavity. Carefully, the outer perimeter was again lightly coated in UV-glue, and a protective housing harvested from a second cavity opening section was glued into place, shown in Supplemental Fig. 8d. The assembled electronics as described in Circuit Design and Fabrication are placed into the biosymbiotic structure and held in place by a small amount of Super Glue (Cyafixed, Instant Adhesive). Full encapsulation using photosensitive UV SLA resin (SuperFast, SuperFlex) that is mixed with one drop of white paint (Alumulite, White), is applied and cured with UV exposure (Supplemental Fig. 8e). The completed DBGS device is shown on-body in Supplemental Fig. 8f.

Benchtop experiments and characteristic equation for sweat rate

A PID tuned 3D printer bed (Creality, Ender 3) was heated to 36.5 C to mimic physiological skin temperature. A rectangular prism of dimensions 50 × 50 × 7.5 mm was 3D modeled in Fusion 360 with a centered hole of outer diameter 1.15 mm. This was uploaded to a 3D slicing software and FDM printed using polylactic acid (Overture, Black), a rigid plastic. In the centered hole, a small PTFE tubing of matching outer diameter and inner diameter of 0.6 mm was fed through and glued. The far end of the tubing was attached to a precision pipette (ONiLAB, YE187AL0051978), allowing 0.5 µL increments in fluid flow. The DBGS cavity was connected using a custom Arduino script using I2C communication. Ambient humidity was controlled by trapping the experimental setup in a non-gas-permeable enclosure with a tray of water heated by the hot plate. This humidity was allowed to build over time, and measurements were not taken until stable ambient humidity readings were outputted by the sensor. Low humidity measurements were taken without an enclosure, and each step-wise increase was facilitated by variable air inlet heights of the enclosure. Sweat rate was calculated by polynomial curve fit to the aggregate data per unit area as reported in Eq. 1.

Axial load to break the skin seal

A biosymbiotic DBGS mesh was worn on the subject’s forearm. The subject rested their arm in a 3D printed cradle that limited movement. A string was threaded through the DBGS cavity and tied to a calibrated load cell (SparkFun, HX711). A 3D-printed stretching stage was designed in Autodesk Fusion 360, consisting of one stationary arm on which the load cell sits and one mobile arm consisting of a stepper motor (Creality, 42-40) and shaft, which may be displaced (JRGJ, LDSW-T8X8-350). This was displaced until a gap was visible between the DBGS cavity and the subject’s skin. Force outputs were collected by a microcontroller (Arduino Nano) via serial logger (CoolTerm) and converted from kg to Newtons. Sweat was artificially added to the skin by use of a single spray of tap water from a spray bottle (Hydior, 2 oz) on the dorsal forearm prior to measurement.

Simulations

The cavity, as described in diffusion-based gas sensor cavity design and biosymbiotic integration, was recreated in ANSYS Workbench 2024b using ANSYS SpaceClaim geometry software. All CFD simulations were performed in the ANSYS Fluent environment. An exterior enclosure of dimensions 240 mm × 120 mm × 240 mm was added to allow for analysis of air flow around and within the housing. Directly below the housing unit, a plate was created to block off air flow entering from the skin-interface opening. The crown housing and base plate were then subtracted from the enclosure via the Boolean function. Interior visualization of the housing was performed by taking a cross-section of the full geometry. To define the boundary conditions of the system, named selections of the inlet, outlet, surrounding walls, housing, and the symmetry wall were created. Linear meshing was performed, utilizing default element sizing and adaptive sizing of resolution 2. The setup of the simulation involved the use of a pressure-based solver in steady-state conditions, with the K-epsilon modeler. Air was defined as the material of the surrounding enclosure, and TPU as the material of the base plate. Note that the material of the base plate is not important in this case, as energy transfer is not being modeled. Simulations were conducted for inlet fluid velocities of 4.470 m/s (10 mph) and 13.4112 m/s (30 mph). The outlet of the system was set as a pressure outlet, with a zero-gauge pressure. Solution methods involved second-order analysis, coupled scheme, and a least squares-based gradient. Standard initialization was performed from the inlet of the system, relative to the cell zone. Calculations involved 250 iterations with an automatic time-step. Results were viewed via CFD-Post. Fluid velocity throughout the system was visualized with the help of streamlines and velocity vectors. The average velocity of the fluid passing through the interior of the housing was determined via a point cloud of 100 points spanning 0.25 mm placed normal to the direction of airflow at the sensor interface and a volume generated to intersect with the walls of the sensing volume.

On-body data collection

In all cases, the DBGS gas-sensing interface was affixed to the subject’s dorsal forearm, with sensing volume located in line with, and inferior to, the distal humeral head. No skin preparation was undertaken. Data were initially collected via a custom Python script run on a researcher’s laptop or a single-board portable computer using Python 3.9 interpreter (Raspberry Pi 4b). Later instances of data collection were accomplished through a custom application developed by the research team utilizing the MIT App Inventor platform. This application was deployed on a BLE-enabled Google Pixel 6a.

Stationary bike tests

To compare device performance with a standard methodology for capturing localized sweat, subjects were asked to complete a steady-state exercise bout on a stationary bike. The subjects were permitted to use their own bicycles, affixed to a trainer (Saris, Fluid) or fitted to a researcher-provided stationary cycling setup. Subjects were given their choice of wrist-based (Garmin, Fenix 7S) or thorax-based (Polar, H10) commercial heart rate monitors to provide real-time feedback on physiological load incurred by the exercise test. The subject was outfitted with a DBGS sweat tracking sensor on their left dorsal forearm, and an analogous biosymbiotic-mimicking TPU mesh platform on their right dorsal forearm, matched for location. The biosymbiotic mimicking platform, which we will call the gold standard band, featured a 50 × 50 mm square extruded 0.45 mm, under which an absorbent swab (Scott, 75147) was placed to capture the accumulation of sweat over time. These swabs were cut to exactly match the inlet area of the DBGS cavity, pre-weighed, and sectioned prior to experiment start. Starting at minute zero, the subject had a swab placed underneath the gold standard band using sterilized tweezers (Kaverme, ESD-13) by the experimenter and immediately began cycling. These swabs were removed from the gold standard band every 2 min, on the minute, and replaced with the next swab immediately. Swabs were weighed on a high-precision scale (Ohaus, PR124), and raw accumulated sweat volume was calculated by subtracting post-exercise weight from pre-experiment tare weight. Subjects were instructed to self-monitor their heart rate and spend the first 5 min of their ride warming up at heart rates corresponding to self-tolerated values below 70% of their reported or calculated maximum heart rate. For subjects without knowledge of their maximum heart rate, this number was calculated using Eq. 2.

After 5 min of warm-up, subjects were instructed to increase the intensity at which they were cycling to 70–80% of their maximum heart rate value. This intensity was maintained for 30 min, after which the subject was asked to cool down for 5 min, defined by cycling at a lower intensity that brings heart rate down below 70% of maximum once again. In some cases, variable fan speeds were introduced to evaluate swabbed sweat response. Fans were placed roughly 2 m from subjects, or the minimum distance necessary for the subject to qualitatively feel uniform cooling across their thorax and data collection zones on the forearm.

Anthropometric data for stationary bike tests

Four subjects participated in stationary bike tests against gold standard. Their anthropometric data in aggregate are listed in Table 1.

Data processing of stationary bike tests

Data was exported as a comma-separated variable datatype. This was uploaded into MATLAB R2021a, where timestamps were derived from Unix time, aided by a real-time clock module (FOSA, DS1307) in the Raspberry Pi platform or native timestamps from the researcher’s laptop. Raw humidity values obtained from top and bottom sensors were fed into Eq. (1) and post-processed via the use of a low-pass filter of 0.1 Hz at a sampling rate of 2 Hz. As concurrent sensor readings relied on BLE client readings from two separate BLE server characteristics, these often were offset; therefore, timestamped NaN datapoints were generated and excluded from analysis. Gold standard band swab measurements in grams were obtained by subtracting each swab’s tare weight in grams from the final weight in grams and dividing by surface area (0.29461 cm2). This value was converted to milligrams of water, which converts directly to the final unit of µL/cm2/min. Each value was compiled into an array, with a corresponding time array increasing from zero by two until 40, for a total of twenty measurements per test. For statistical comparison, the continuous data stream from the DBGS sweat sensor was iterated through a for loop to produce an average sensor reading over each 2-min period corresponding to swab replacement. Per test, this generated two twenty-cell arrays, which were used in Bland-Altman and Coefficient of Variance Analysis78. All data from all subjects is eventually plotted, in which averaged sensor readings and averaged swab readings were concatenated by experiment instance, and analyzed in the same way. Data were excluded in cases where sensor saturation was achieved, defined by interior relative humidity values greater than 100% (n = 4).

Correlation metrics were obtained from identical tests performed by each subject on nonconsecutive days. These waveforms were averaged every 10 s, to generate 240 (40 min) datapoints per test. MATLAB’s corrcoef function was used to generate repeatability correlation (R), and p values.

Field-collected data

Data collected in the field initially utilized the DBGS sweat sensor and a Raspberry Pi continually running a data collection script while powered by a 99.2 W/h portable power bank (Dongguan Yuanhaoxun Technology Co., HX200K1). In future sections, this is referred to as Raspberry Pi data collection. Due to the bulk of this data collection system, a BLE-enabled Android (Google, Pixel 6a) application was developed using MIT App Inventor 2, especially useful in chronic-use experimentation. In future sections, we will refer to this as phone data collection.

Field-collected data: weightlifting

Field-collected weightlifting data, as shown in Fig. 4a was recorded via Raspberry Pi data collection. The subject wore a commercial wrist-based heart rate sensor (Garmin, Fenix 7S) and synchronized initialization of data recording from both sensors simultaneously. The subject was allowed free garment choice and wore a breathable long-sleeve sun shirt, which covered the DBGS sweat tracker. The subject performed a warm-up and lifting routine tailored to his individual goals. The warm-up routine consisted of thirteen minutes of increasing intensity of deadlift, bent-over row, hang clean, and shoulder press, beginning with an unloaded bar. The warm-up period included a progressive build on the deadlift lift to 75% of the subject’s 1 rep max. The subject was training strength gains, and as such, implemented short sets with long rests. In total, 3–5 repetitions of the deadlift were performed at 85% of the subject’s 1 rep max, followed by 3–5 min of rest between each of the four sets, as tolerated by the subject.

Field-collected data: indoor/outdoor stationary cycling

Field-collected cycling data, as shown in Fig. 4b was recorded via phone data collection. The subject followed a similar protocol to that of the gold-standard comparison stationary bike ride, using a personal road-cycling bike (Giant, AR4), and stationary trainer (Saris, Fluid) with the exception of data collection without corroboration of swabs weighed on a precision scale, and only 20 consecutive minutes in heart rate Zone 3. This experiment saw the subject synchronize wrist-based heart rate data with sweat tracking initiation. After a total of 30 min of riding (5 min warm up and cool down), the subject sat motionless until all active sweating had cessated, defined by qualitative feelings of such, heart rate readings returning to within 10% of baseline, and DBGS sweat tracker readings of under 0.05 µL/cm2/min. After the baseline was reached, the subject took his stationary cycling setup outdoors and repeated the experiment. Data collection was uninterrupted between the two tests. This was also repeated in the same manner, beginning outdoors and moving indoors.

Field-collected data: tennis

Field-collected tennis data, as shown in Fig. 4c was recorded via Raspberry Pi data collection. The subject wore the DBGS sweat tracker on their non-dominant forearm and placed the data collection module on an elevated surface to maximize Bluetooth range. The subject wore a short-sleeved shirt. Like other activities, data collection of concurrent heart rate and sweat rate was initiated simultaneously. The subject here performed a typical practice session based on his own definition and kept a running journal of changes in session goal (later assigned to warm-up, skill work, and matchplay). The warm-up consisted of informal drills centered around long baseline rallies typical of tennis workouts. The cessation of warm-up followed particularly intense movement drills that required the subject and opponent to maintain consistency while changing the flight path of the received tennis ball with each shot (otherwise known as directionals), which inevitably results in required alley-to-alley line movement. Skill work consisted of lower physiologically demanding drills, such as warming up serve, and drills designed to develop pinpoint accuracy. As mentioned, the matchplay simulation consisted of a series of three tiebreakers. In tennis scoring, points comprise games, which comprise sets, which comprise matches. In a set tiebreaker, the two players compete to be the first to win 7 points, by at least 2 points. In a match tiebreaker, the two players compete to be the first to win 10 points, by at least 2 points. These are typically chosen by players to simulate matchplay, as they introduce high-stakes point play, without requiring potentially multiple hours to complete.

Field-collected data: chronic data collection

Field-collected chronic-scale data, as shown in Fig. 4d was recorded via phone data collection. The subject wore a DBGS sweat tracker continuously for multi-day periods. This experiment began on a Monday at 8:30am, and the device was worn continuously except for instances of showering. This data collection was paused at 11:40 pm on the following Thursday. During this experiment, the subject left the state to attend a wedding and removed the device until 10:20 am on the next Monday. The device was kept in a sealed container with the power switch off, and to restart the experiment, the subject simply reattached the sensor to his arm. No additional charging or device maintenance was necessary, and the experiment terminated on that Thursday at 1:30 pm. Periods of data dropout were experienced, most notably during sleep when the connection timed out and the subject was unable to reconnect by Bluetooth. As evaluation of the effectiveness of the Bluetooth module is not the target for evaluation, this data was excluded and time-shifted resulting data to create a cohesive data set.

Field-collected data: spicy food

Field-collected high spice food intake, as shown in Fig. 4e, was recorded via phone data collection. The subject wore a DBGS sweat tracker on their left forearm and time-synced an activity tracker watch (Garmin, Fenix 7S). The subject brought a bland meal, consisting of lightly salted chicken and pasta, then added hot sauce (Dave’s Gourmet, Carolina Reaper) to the point of self-defined discomfort. The subject sat in place, unstimulated and with sensors running, for 15 min prior to food ingestion. After 15 min, the subject ate their meal over 10 min, then sat motionless and unstimulated for another 15 min to test for sweat cessation, if any.

Field-collected data: run cessation

Field-collected run cessation data, as shown in Fig. 4f, were recorded via phone data collection. This experiment simply required the subject to perform a sweat-inducing activity outdoors and continue to monitor sweat after exercise cessation. This was accomplished via a trail run activity in the Tucson Mountain Park, of which four miles were covered with an average heart rate of 155 bpm. Not pictured in Fig. 4f is an additional 30 min of exercise prior to the bounds of this graph.

Field-collected data: sleep

Field-collected sleep data, as shown in Fig. 4g, was recorded via Raspberry Pi data collection. This experiment involved a subject wearing a DBGS sweat sensor to bed to monitor sleep cycle, with concurrent output from the temperature sensor embedded in the SHT-30 hardware.

Skin gas sensor development

CO2 sensing was accomplished via a dual-sensor architecture similar to the one used in sweat tracking. Metal–oxide CO2 (Sensirion, STC31) sensors were configured to simultaneously output top and bottom sensor readings via a custom Arduino script using the default (0 × 29) and secondary (0 × 2A) I2C addresses. Communication lines were pulled up via 4.7 kΩ series resistors. Power and ground were decoupled via a 1 µF capacitor. The diffusion-based gas cavity was modified only by an increase in sensor hole size to accommodate the footprint of the sensor. Data were collected via serial interface (CoolTerm) and timestamped locally, or written directly to an SD card module (HiLetgo, 3-01-0038) via SPI protocols. Sensor architecture was integrated into a dummy biosymbiotic system with a microcontroller (Arduino, Nano) embedded in place of biosymbiotic electronics. This was attached to the left forearm for tests as described in detail in the following sections: “Diffusive-Based Gas Sensing Modality test protocol: Bike, Diffusive-Based Gas Sensing Modality test protocol: Alcohol, Diffusive-Based Gas Sensing Modality test protocol: AX-CPT.”

VOC sensing was accomplished via a slightly different dual-sensor architecture than previous iterations. A high-sensitivity metal-oxide sensor (Sensirion, SGP41) sensitive to VOC emission was chosen. This particular sensor does not support multiple I2C addresses, so two N-type MOSFETs (Nexperia, PMZ130UNEYL) were connected to SDA lines from two non-integrated VOC nodes. The voltage input was routed to digital pins on a microcontroller (NodeMCU, ESP8266) and pulsed every 200 ms, allowing data from each sensor to be read in an alternating fashion. SCLK lines were shared. Data were collected via serial interface (CoolTerm) and timestamped locally, or written directly to an SD card module (HiLetgo, 3-01-0038) via SPI protocols. Sensor architecture was integrated into a dummy biosymbiotic system with the microcontroller embedded in place of biosymbiotic electronics. This was attached to the right forearm for tests as described in detail in the following sections: “Diffusion-Based Gas Sensing Modality test protocol: Bike, Diffusion-Based Gas Sensing Modality test protocol: Alcohol, Diffusive-Based Gas Sensing Modality test protocol: AX-CPT.”

On-body data collection for CO2 and VOC DBGS paradigms

From the results of Fig. 5b, c, it was determined that an initialization and equalization period is required for the highest fidelity CO2 and VOC sensor data acquisition. A 10 min ambient equalization period for all three sensing modalities was undertaken.

CO2 calibration

CO2 calibration readings were obtained by mixing compressed air of typical ambient gas concentrations (80% O2, 0.04% CO2, 19.96% other gases) with decreasing quantities of exhaled breath in a balloon. At rest, exhaled breath is 4% CO2. The balloon is clamped to a small (3 mm inner diameter) tube which inserts gas into a sealed accumulation volume consisting of a large (100 mm2) opening to ambient air, and a small opening the size of the DBGS skin-interface (30 mm2). The DBGS CO2 cavity was sealed to the accumulation volume using masking tape. The sensor was initialized in this configuration under ambient conditions for 5 min, after which volumes of test gas were released into the mixing volume over the course of 1 min. After 1 min and complete replacement of ambient air with test concentrations, the balloon is removed, and sensor readings are captured over 2 min. The proportion of CO2 in the mixing volume was increased to 0.139–1.03% CO2 concentration, or 1390–10300 ppm. Readings from ambient-facing sensors and DBGS cavity sensors were recorded, and calibration values representing sensor response were obtained by subtracting the mean value of the entire 5 min of equalization from the maximum amplitude change, occurring within the first 20 s after the balloon was released. This calibration yielded Eq. (3), showing a linear response curve through the physiological range.

VOC calibration

VOC calibration readings were obtained by mixing 91% Isopropyl Alcohol (IPA) (Florida Laboratories, Isopropyl Alcohol 91%) with Distilled water in decreasing amounts, ranging from 1% to 0.0000025% by volume (107-25ppb). The DBGS VOC chamber was taped down to a large open glass container (Coccot, ASIN B0CC5MRWFH). The sensor and glass container were placed on a PID-enabled hot plate (HLHgirl, B0CGQX4M88), set to 36.5 degrees Celsius. A thin string was routed through the outer row of pillars of the DBGS, which was then used to open the test volume to ambient conditions. An enclosure was constructed around the hot plate, consisting of a 6 cm vacuum inlet located 10 cm vertically from the glass container to shield the sensing setup from the effects of breath and other ambient VOC sources. The test was initialized with test volume exposed to ambient conditions, where the sensors were equalized for 10 min. After 10 min passed, a 1.5 µL droplet of pre-mixed solution of IPA and distilled water was placed onto the small mark underneath the test volume. At this time, the sensor was sealed to the alcohol mixture, which sat for 20 min. After 20 min, the test volume was again exposed to ambient conditions for 10 min, and the test was repeated with the next concentration. Differential readings from ambient-facing sensors and test-volume sensors were captured for the entire test duration, and calibration values representing sensor response to test concentrations of VOC titrations were obtained by subtracting the mean value of the exposed-to-ambient equalization period from the maximum amplitude change. This calibration yielded Eq. (4), showing a linear response through the physiological range.

Diffusion-based gas sensing modality test protocol: bike

This experiment followed the same protocol as Field-Collected Data: Indoor/Outdoor Stationary Cycling, only data collection was stopped at the termination of the indoor bike ride. DBGS sweat tracker, CO2, and VOC platforms were all attached to the subject’s dorsal forearm. The subject warmed up for 5 min with heart rate readings below 70% of maximum. After this warm-up, the subject rode at 70–80% of maximum for 25 min, followed by a 5 min cooldown and an idle period of 5 min following. The data were timestamped and temporally matched in MATLAB R2021a. Differential values of CO2 and VOC were calculated by subtracting the bottom sensor from the top sensor, then dividing the entire generated array by the maximum value in the dataset. Prior to plotting, the data were postprocessed via a smoothing spline of magnitude 0.01.

Diffusion-based gas sensing modality test protocol: alcohol

This protocol was adapted from Yoda et al.73. DBGS sweat tracker, CO2, and VOC platforms were all attached to the subject’s dorsal forearm. The subject fasted from prior mealtime (for example, a dinner experiment required no food after lunch, and a morning experiment required fasting from 8 pm the night before). The subject had all sensors attached by a sober researcher, who timesynced the start of each sensing modality. The subject sat for a 15 min equalization period with no stimuli. At this time, the researcher prepared an alcoholic drink mix containing 0.36 g of ethanol per kg of body weight. After the equalization period concluded, the subject ingested the prepared alcohol and remained seated for an additional 45 min with no external stimulus. Participants were additional members of the research team, of legal drinking age, and required to sign an Informed Consent Form as necessitated by the University of Arizona’s Institutional Review Board. The data were timestamped and temporally matched in MATLAB R2021a. Prior to plotting, the data were postprocessed via a smoothing spline of magnitude 0.01.

Diffusion-based gas sensing modality test protocol: AX-CPT

This protocol was adapted from Marcora et al.76. In this experiment, the subject saw the DBGS sweat tracker, CO2, and VOC platforms all attached to the subject’s dorsal forearm. The subject sat for a 15 min equalization period with no stimuli. After this period passed, the subject ran an executable script available for download from https://www.millisecond.com/download/library/cpt, which instantiated a 20 min version of the AX-CPT continuous performance task. In this task, the subject indicates “correct” or “incorrect” for a pairing of letters, separated by two distracting letters. When the first in a sequence of four is ‘A’, and the fourth in the sequence is ‘X’, the subject responds ‘True’. All other combinations are false. All incorrect answers are accompanied by a distracting beeping noise. After completing the test, the subject sits motionless for another 15 min equalization period. Prior to plotting, the data were postprocessed via a smoothing spline of magnitude 0.01.

Ethics

Subjects participating in reported experiments followed procedures approved by the University of Arizona Institutional Review Board under Protocol number 00005295. Each participant gave informed written consent.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary files. Any additional requests for information can be directed to, and will be fulfilled by, the corresponding authors. Source data are provided with this paper. The data necessary to interpret, verify, and extend the research generated in this study have been deposited in the Zenodo.

Code availability

Data collection and processing scripts are included in the Zenodo database alongside collected data necessary to interpret the findings of this paper.

References

Stuart, T., Hanna, J. & Gutruf, P. Wearable devices for continuous monitoring of biosignals: challenges and opportunities. APL Bioeng. 6, 021502 (2022).

Childs, A. et al. Diving into sweat: advances, challenges, and future directions in wearable sweat sensing. ACS Nano 18, 24605–24616 (2024).

Min, J. et al. Skin-interfaced wearable sweat sensors for precision medicine. Chem. Rev. 123, 5049–5138 (2023).

Sempionatto, J. R., Montiel, V. R. V., Vargas, E., Teymourian, H. & Wang, J. Wearable and mobile sensors for personalized nutrition. ACS Sens. 6, 1745–1760 (2021).

Clausen, D. et al. Chronic biosymbiotic electrophysiology. Adv. Funct. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.202407086 (2024).

Zhao, J. et al. A wearable nutrition tracker. Adv. Mater. 33, e2006444 (2021).

Baker, L. B. et al. Skin-interfaced microfluidic system with personalized sweating rate and sweat chloride analytics for sports science applications. Sci. Adv. 6, eabe3929 (2020).

Sekine, Y., Toyooka, S. & Watts, S. F. Determination of acetaldehyde and acetone emanating from human skin using a passive flux sampler-HPLC system. J. Chromatogr. B Anal. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 859, 201–207 (2007).

Naitoh, K. et al. New measurement of hydrogen gas and acetone vapor in gases emanating from human skin. Instrum. Sci. Technol. 30, 267–280 (2002).

Sekine, Y., Oikawa, D. & Todaka, M. Human skin gas profile of individuals with the people allergic to me phenomenon. Sci. Rep. 13, 9471 (2023).

Mochalski, P., King, J., Unterkofler, K., Hinterhuber, H. & Amann, A. Emission rates of selected volatile organic compounds from skin of healthy volunteers. J. Chromatogr. B Anal. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 959, 62–70 (2014).

Ahuja, P. et al. Air-permeable redox mediated transcutaneous CO2 sensor. Chem. Eng. J. 457, 141260 (2023).

Stuart, T. et al. Biosymbiotic platform for chronic long-range monitoring of biosignals in limited resource settings. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2307952120 (2023).

Stuart, T. et al. Context-aware electromagnetic design for continuously wearable biosymbiotic devices. Biosens. Bioelectron. 228, 115218 (2023).

Stuart, T. et al. Biosymbiotic, personalized, and digitally manufactured wireless devices for indefinite collection of high-fidelity biosignals. Sci. Adv. 7, eabj3269 (2021).

Tyree, A. et al. Biosymbiotic haptic feedback—sustained long term human machine interfaces. Biosens. Bioelectron. 261, 116432 (2024).