Abstract

Guided bone regeneration (GBR) is a standard therapy for treating bone defects, with collagen-based barrier membranes widely used clinically. However, these membranes face challenges like poor mechanical properties, early bacterial invasion and immunomodulation deficiency, potentially risking GBR failure. Orchestrating macrophage activation and controlling their M1 or M2 polarization are effective strategies for bone repair. Here, we present a Janus collagen-based barrier membrane with immunomodulation. The porous layer promotes direct osteogenic differentiation and inward growth of osteoblasts. The dense layer prevents invasion of soft tissue into bone defects and protects bone defects from bacterial infection. The membrane also enhances rat bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cell infiltration, proliferation, and osteogenic differentiation by regulating the immune microenvironment, demonstrating superior bone regeneration compared to the commercial Bio-Gide® membrane. Overall, the Janus collagen-based membrane reduces tissue inflammation and fosters an osteoimmune environment conducive to new bone formation, offering effective material design for advanced GBR technology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Bone damage can lead to disability, causing pain and discomfort for many patients, with infections, trauma, and systemic diseases being major contributing factors1. The guided bone regeneration (GBR) technique has become a standard therapy for treating bone defects clinically, while the core of this technique is the GBR membrane2,3,4. Presently, collagen-based GBR membranes (e.g., Bio-Gide®, AlloDerm®) have gained widespread application in clinical practice. Collagen serves as the predominant constituent of natural bone, and it features the adhesion ligand arginine-glycine-aspartic acid sequences, which facilitates easy cell attachment5,6. This aligns more closely with the design requirements of biomimetic materials. Collagen-based GBR membranes currently encounter numerous challenges, including inferior mechanical strength and unsatisfactory barrier properties resulting in inadequate osteogenic potential7, precisely controlling pore size and elasticity of GBR membranes to regulate macrophage behavior and osteoblast anchoring remains to be solved, bacterial invasion leads to the failure of GBR in bone repair8,9, and the remodeling of immune homeostasis in the bone engineering community1,10. Therefore, developing collagen-based GBR membranes that primarily serve as post-implantation barriers, exhibit superior mechanical properties, and can adapt to the complex immune microenvironment of advanced bone regeneration to meet the clinical demand for intelligent biomaterials with enhanced biological activity is a significant undertaking.

Janus GBR membranes draw inspiration from the two-faced god in ancient Roman mythology, which has asymmetric chemistry, morphology, and properties2,11. An ideal Janus GBR membrane can simultaneously serve as a barrier on one side for fibroblasts while providing a growth space for osteoblasts on the other side12. Currently, collagen-based Janus membranes have been fabricated by advanced technologies, such as electrospinning, 3D printing and layered casting methods13,14. In contrast, the layered casting method can quickly obtain the collagen-based Janus membranes with controllable structure and satisfactory performance, which is suitable for achieving industrialization and mass production.

The immune microenvironment at the site of bone defects is dysregulated due to the long-term sustained inflammatory response caused by implant materials, bacterial invasion, necrotic tissue, etc15. These inflammatory responses initiate diverse biochemical signals that can determine local cell plasticity, particularly macrophage polarization plays a critical role in bone regeneration16,17,18. Macrophages in the pro-inflammatory M1 phenotypes are recruited promptly to the site of material implantation, and then programmed transition to anti-inflammatory M2 phenotypes after 3–4 days of injury10. However, if the M1 phenotype persists for an extended period and there is a failure to enhance the M2 phenotype, macrophages may be unable to resolve inflammation, ultimately leading to poor bone healing19. Therefore, orchestrating the spatiotemporal activation of macrophages and precisely controlling their M1-M2 polarization during bone repair holds promise in therapeutics20.

Active drugs, such as antibiotics, natural products, bio-enzymes, and cytokines are introduced into the GBR membranes to kill bacteria and relieve inflammation, promote the remodeling of the immune microenvironment in the bone defect site, and achieve rapid bone repair21. However, the initial burst release and uncontrolled continuous drug release can lead to excessive local drug concentrations, potentially disrupting bone repair22. Interestingly, using nanocarriers to load active drugs can not only protect the drug activity and improve the bioavailability of insoluble drugs, but also realize the controlled release of drugs, and finally realize the ideal therapeutic effect23. Curcumin (Cur) as a natural phenolic compound exhibits good antioxidant activity and anti-inflammatory effects besides low toxicity and small adverse reactions (side effects), but is almost insoluble in water24. Therefore, the nano drug delivery system has been applied to incorporate Cur to significantly improve its bioavailability and realize long-term sustained drug release25. Dual drug loading achieved by incorporating both nanocarrier-loaded Cur and the broad-spectrum bactericidal agents will undoubtedly endow GBR membranes with rapid bactericidal and long-lasting anti-inflammatory activities. The coordinated drug administration strategy will effectively regulate the polarization of macrophages, and promote the rapid regression of inflammation and the remodeling of immune homeostasis in the bone defect site. Therefore, the cleverly integrated Janus structures, retained collagen activity, strong mechanical properties, and spatiotemporal immune microenvironment regulation in GBR membranes are expected to solve the clinical challenges of advanced bone regeneration.

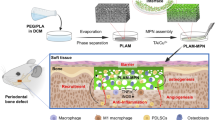

Here, we report a Janus collagen-based GBR membrane (Collagen-DCMC@Curcumin/Chlorhexidine, CDCC) that is simply and effectively prepared by the layered casting method (Fig. 1). The dialdehyde carboxymethyl cellulose (DCMC) is utilized as a non-toxicity crosslinker to enhance the mechanical properties of the membrane. Simultaneously, the use of collagen with different molecular weights on both sides facilitate the natural formation of a dense layer, providing inherent support and further enhancing its mechanical performance. Nano-micelles loaded Cur and CHX are dual introduced into the matrix of GBR membranes to make collagen-based GBR membranes have both antibacterial and anti-inflammatory activities. Meanwhile, nano-hydroxyapatite (nHAP) is introduced into the porous layer to mimic the osteogenic microenvironment. Furthermore, we demonstrate that the time-controlled delivery of two drugs can effectively modulate the microenvironment of bone formation, thereby promoting bone regeneration. We conduct a comprehensive investigation on the mechanical strength, biocompatibility, barrier function, osteogenesis, antibacterial properties, and osteo-immunomodulatory properties of the membrane, while the regenerative potential in vivo is assessed utilizing a rat cranial defect model. This study not only provides a fresh solution for collagen-based bone repair materials but also presents a straightforward, industrially scalable method for customizing Janus materials. Moreover, its potential applications can be extended to various other areas within the field of biomaterials, such as multi-layer skin repair membranes, and multi-layer joint scaffolds.

Schematic diagram of the preparation of multifunctional CDCC membrane and its application for advanced bone regeneration in the rat skull defect area. Figure 1 created with BioRender.com released under a Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International license (https://BioRender.com/ou7zczv).

Results and discussion

Preparation and characterization of curcumin@cholesteryl-polyethylene glycol nanomicelles (Cur@Chol-PEG NMs)

Cur@Chol-PEG NMs were fabricated as shown in Supplementary Fig. 1. Firstly, the amphiphilic polymer cholesteryl-polyethylene glycol (Chol-PEG) was synthesized through the substitution reaction using polyethylene glycol (PEG) with a molecular weight of 2000 and cholesteryl chloroformate (Chol). Afterwards, the Chol-PEG was loaded with the hydrophobic drug Cur using the emulsification-thin film dispersion method to prepare Cur@Chol-PEG NMs. In the FT-IR spectrum of Chol-PEG, the characteristic peak of Chol appeared at 1778 cm−1 (Supplementary Fig. 2A). In the 1H-NMR spectrum of Chol-PEG, the characteristic peaks of Chol were observed at 0.6-2.0 ppm, including -CH3 (0.64 ppm), -CH3 (0.83-0.85 ppm), -CH3 (0.93 ppm), and -CH3 (1.30-1.40 ppm) (Supplementary Fig. 2B). All the results proved that the Chol was successfully conjugated onto the backbone of PEG to obtain the amphiphilic polymer Chol-PEG. Then the Chol-PEG was self-assembled into nanomicelles via the emulsification-thin film dispersion method. The critical micelle concentration of Chol-PEG is about 16.35 μg/mL. We can observe the Tyndall effect when light passes through the Cur@Chol-PEG NMs suspension, while it is not visible in the Cur aqueous solution (Supplementary Fig. 2C). This confirmed the formation of nanomicelles. The characteristic peaks of the benzene ring of Cur appeared at 1603 cm−1 and 1630 cm−1 in the FT-IR spectrum of Cur@Chol-PEG NMs (Supplementary Fig. 2D). The result indicated that Cur was successfully loaded into nanomicelles. The Cur loading efficiency and entrapment efficiency of Cur@Chol-PEG NMs were 54.2 ± 3.4 mg/g and 88.4 ± 6.4%, respectively (Supplementary Table 1). The hydrophobic tails aggregate to form a hydrophobic core in an aqueous solution, which can encapsulate and dissolve hydrophobic Cur, thereby increasing its solubility. The morphology of both Chol-PEG NMs and Cur@Chol-PEG NMs was observed using transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Chol-PEG NMs and Cur@Chol-PEG NMs showed well-defined spherical morphology (Supplementary Fig. 2E, F). The average particle size of Cur@Chol-PEG NMs (~57 nm) was larger than that of Chol-PEG NMs (~33 nm), which was mainly on account of Cur loading (Supplementary Fig. 2G). The mean sizes of Chol-PEG NMs and Cur@Chol-PEG NMs in water, measured by DLS, were approximately 50 nm (PDI = 0.194) and 78 nm (PDI = 0.157), respectively (Supplementary Fig. 2H). All the prepared nanomicelles showed good monodispersity with a relatively narrow size distribution. Significantly, the Cur@Chol-PEG NMs loading strategy facilitates the effortless incorporation of the poorly water-soluble Cur into the membrane matrix.

Fabrication and characterization of the janus GBR membrane (CDCC)

The CDCC membrane composed of a dense layer and a porous layer was fabricated (Supplementary Fig. 3). Initially, a dense-layer collagen-based membrane with a non-porous structure was achieved through evaporation-induced assembly and the Schiff’s base reaction of single-chain collagen peptide with a macromolecular polysaccharide cross-linking agent, DCMC. The surface of the dense-layer membrane was subsequently coated with a thin layer comprising a mixture of collagen, DCMC, and nHAP. This layer was then transformed into a porous structure through an ice-templating process. To enhance the bioactivity of the membrane, we introduced Cur@Chol-PEG NMs and the antibacterial drug CHX into the pre-liquid used for membrane preparation, aiming to modulate the immune response in the bone formation microenvironment. The CHX has good water solubility, allowing it to be uniformly mixed directly into the membrane matrix without the use of nano-carriers, thereby achieving faster release. The amino groups on the collagen chains of the dense and porous layers form dynamic amide bonds with the abundant aldehyde groups on the DCMC chains at the junction, resulting in chemical crosslinking and strong binding between the two layers. The cross-section of the CDCC membrane, transitioning from the dense layer to the porous layer, exhibits a gradient of red fluorescence ranging from deep to light red (Supplementary Fig. 4). This red fluorescence at the interface indicated the formation of interlayer amide bonds. The CDCC membrane showcased flexibility, with one side displaying a yellow hue while the other remains white, highlighting their unique structural characteristics (Supplementary Fig. 5). The microstructures of the CDCC membranes were observed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (Fig. 2A). The dense layer is approximately 200 μm thick, while the porous layer is about 800 μm thick (Supplementary Fig. 6). The pore size of the porous part is normally distributed around 108 μm (Supplementary Fig. 7). It is in the optimal pore size range (100–200 μm) for osteoblast growth26. From the top and side views of the dense layer, it was clear that the surface presented a non-porous topology. That was because the single-chain collagen peptide first formed a 3D network structure in water through hydrogen bonding and electrostatic interactions. The addition of a cross-linking agent generated more connection sites with single-chain collagen peptides, reinforcing the 3D network for firmness. And the dense single-chain collagen peptide membrane was formed due to the intensified crosslinking between collagen and DCMC as the solvent slowly evaporated. It is worth noting that the membrane formation process required simultaneous gelation and solvent evaporation. If the solution gels before the solvent evaporates, the network structure becomes fixed, leading to the formation of a hydrogel instead of a dense membrane. The porous layer, obtained through the ice-templating technique, was tightly combined with the dense layer. Inspection from both the bottom and side views of the CDCC membrane revealed a characteristic porous microstructure. The macroporous structure of the porous layer arose from the sublimation of ice crystals, which left behind pores initially occupied by these crystals within the template material, resulting in a highly organized pore arrangement. The shape and size of these pores can be adjusted by controlling the growth conditions of ice crystals, as well as the degree and quantity of cross-linking agent added. Energy-dispersive X-ray spectrometry mapping (EDX, mapping) was conducted to analyze the distribution of chemical elements. The results demonstrated that nHAP was evenly distributed across the framework of the porous layer (Fig. 2B; Supplementary Fig. 8). Meanwhile, a higher concentration of carbon elements was observed in the dense layer compared to the porous layer, reflecting its denser structure. The roughness analysis performed with atomic force microscope (AFM) images was in accordance with the microstructure imaged (Fig. 2C). The porous layer exhibited significantly higher Rq and Ra values of 489 nm and 380 nm, respectively, compared to the dense layer, with Rq and Ra values of 142 nm and 109 nm (Supplementary Fig. 9). It indicated that the surface roughness of the porous layer was higher than that of the dense layer, implying the presence of more microscopic undulations and irregularities. On rough surfaces, cells may exhibit increased protrusions and extensions, which are beneficial for cell attachment and growth27,28. Microstructural variances between the two surfaces of the CDCC membrane led to differences in their properties, as demonstrated by water contact angle (WCA) measurements. Drops deposited on the porous layer surface were fully absorbed, while those on the dense layer surface were retained (Fig. 2D). The contact angle on the porous layer surface decreased rapidly from 100.7° to 30.1° within the first 5 seconds, while the contact angle on the dense layer surface remained nearly constant at around 130° during the same period (Fig. 2E; Supplementary Fig. 10). The hydrophilic porous layer can facilitate cell attachment, development, and adhesion, while the dense layer with relatively hydrophobic characteristics can block the infiltration and erosion of fibroblasts.

A SEM images of the porous layer, the dense layer, and the sectional view of the CDCC membrane (n = 3 independent replicates, Scale bars:100 μm). B The merged SEM-EDX mapping images of each side of the CDCC membrane (n = 3 independent replicates, scale bars: 100 μm). C AFM images of the porous and dense layer of the CDCC membrane (n = 3 independent replicates). D The time-dependent images of water contact angle for the dense and porous layers (n = 8 independent replicates, scale bars: 250 μm). E The stable water contact angle statistical chart of the dense and porous layer (n = 8 independent replicates, Two-tailed Student’s t test, mean value ± SD). F Tensile properties of CDCC and Bio-Gide® membranes (n = 4 independent replicates, Two-tailed Student’s t test, mean value ± SD). G The tensile stress (TS) of the porous layer, the dense layer, and the CDCC membrane (n = 4 independent replicates, Two-tailed Student’s t test, mean values ± SD). H The elongation at break (EAB) of the porous layer, the dense layer, and the CDCC membrane (n = 4 independent replicates, Two-tailed Student’s t test, mean value ± SD). I Interfacial toughness (T-peel test) of CDCC and Bio-Gide® membranes (n = 4 independent replicates, Two-tailed Student’s t test, mean value ± SD). J shear strength (lap-shear test) of CDCC and Bio-Gide® membranes (n = 4 independent replicates, Two-tailed Student’s t test, mean value ± SD). K adhesive strength of CDCC and Bio-Gide® membranes (n = 4 independent replicates, Two-tailed Student’s t test, mean value ± SD). The release curves of (L) CHX and (M) Cur (n = 3 independent replicates, Two-tailed Student’s t test, mean value ± SD). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The mechanical strength of the GBR membrane used for GBR surgery is an important factor to be considered. The bilayered CDCC membrane exhibited an optimal tensile strength (~22.90 MPa), T-peel strength (~100.00 J/m2), lap-shear strength (~122.42 KPa) and adhesive strength (~46.74 KPa), which are much larger than those of Bio-Gide® membrane (~7.54 MPa, ~34.88 J/m2, ~66.29 KPa, ~9.71 KPa) (Fig. 2F, I–K). Under wet conditions simulating for practical clinical applications, the tensile strength of the Bio-Gide® membrane was only about 0.74 MPa, which is much lower than that of the CDCC membrane (~3.97 MPa) (Supplementary Fig. 11). The CDCC membrane has high elongation at break (EAB) values both under dry and wet conditions (dry: 100.66 ± 4.43%, wet:111.80 ± 29.25%), demonstrating significantly better toughness than the Bio-Gide® membrane (dry: 220.62 ± 7.08%, wet: 29.91 ± 8.58%), highlighting its superior mechanical performance (Fig. 2H; Supplementary Fig. 11). The strain-stress curve of the dense layer of the CDCC membrane closely resembled that of the CDCC membrane (double layer), suggesting that the mechanical strength of the CDCC membrane primarily originated from the dense layer (Fig. 2G; Supplementary Fig. 12, 13). This is mainly due to the high packing density of the dense layers in the CDCC membrane. The addition of the DCMC can introduce more crosslinking bonds in both the Col-DCMC and the CDCC membrane, leading to higher mechanical stress compared to the pure Col membrane. What is particularly noteworthy is that DCMC is a naturally derived macromolecular crosslinker that exhibits no biological toxicity29. In vivo, the interlayer binding force of the CDCC membrane helps maintain its bilayer structure (Supplementary Fig. 14). The favorable mechanical properties of the CDCC membrane prevent it from collapsing into the bone defect during treatment, thereby preserving space for bone cell growth and effectively promoting bone repair30.

Sequential drug release, swollen and degradation resistance properties of the CDCC membrane

The swelling behavior of the CDCC membrane is similar to that of the Bio-Gide® membrane, with both membranes maintaining stable morphology after swelling in PBS (pH 7.4), Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS), and Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) solutions (Supplementary Fig. 15, 16). These findings suggest that both membranes can maintain their structural integrity in body fluids. The Bio-Gide® membrane lost its structure and fragmented after 5 days of in vitro degradation, whereas the CDCC membrane degraded slowly and retained most of its morphology even after 28 days (Supplementary Fig. 17, 18). This result demonstrated that the CDCC membrane exhibited significantly better degradation resistance than the Bio-Gide® membrane. The Schiff’s base crosslinking between collagen and DCMC provided the collagen-based GBR membrane with high resistance to degradation31,32. Furthermore, the addition of CHX made the CDCC membranes have antibacterial activity, thus effectively avoiding the biodegradation caused by the fast-growing bacteria to prolong the degradation time of the CDCC membranes. The CDCC membrane possesses adequate swollen properties and enhanced degradation resistance properties, which are conducive to its clinical applications in bone repair in vivo.

The dissolution of the membrane skeleton will lead to the release of the drug33. We determined the cumulative release of CHX and Cur by dialyzing the samples in simulated body fluid34. The results indicated that there was an initial burst release of CHX from the CDCC membrane of about 60% over 5 days, followed by an adsorption and desorption dynamic equilibrium, while the free-CHX due to its good water solubility was released completely within 1 day (Fig. 2L). The study of the release kinetics showed that the release of CHX in the CDCC membrane conformed to the Weibull distribution model (R2adj=0.991, MSC = 4.401), indicating that the release of CHX is driven by a combination of the concentration difference and the networks swelling (Supplementary Fig. 19; Supplementary Table 2). Meanwhile, free-Cur, being hydrophobic, faces difficulties in cell penetration when applied alone. The encapsulation of Cur by the nanocarrier Chol-PEG NMs in the CDCC membrane enabled sustained release for up to 60 days (Fig. 2M). The release of Cur in the CDCC membrane conformed to the Weibull distribution model (R2adj=0.998, MSC = 5.907) and the first-order model (R2adj=0.995, MSC = 5.167) (Supplementary Fig. 20; Supplementary Table 3). The β value in the Weibull distribution model fitting is 0.886 confirming a non-Fickian transport (Supplementary Table 3). Therefore, the mechanism of Cur release is a synergism of drug diffusion and matrix corrosion, and the nanocarriers improved the water solubility of the hydrophobic Cur. According to previous studies, bone defect remodeling from day 1 to day 5 is in the inflammatory stage, followed by a remodeling stage lasting up to 1 month30. Therefore, the rapidly released CHX can eliminate bacteria from the wound surface after surgery and inhibit bacterial growth. The slowly released Cur can regulate bone regeneration microenvironment and reduce inflammation. The sequential release of Cur and CHX achieved by leveraging the dissolution of the CDCC membrane skeleton and the sustained release effect of the nanocarrier Chol-PEG NMs is aligned with clinical application requirements.

Antibacterial functions of the CDCC membrane

Antibacterial properties are essential for wound healing after surgery35,36. In this study, CHX was incorporated into the CDCC membrane to confer long-term antibacterial function, and the membrane without CHX was selected as the control. The antibacterial properties were evaluated in vitro against Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) and Escherichia coli (E. coli), which are representative of Gram-positive bacteria and Gram-negative bacteria, respectively. The antibacterial zone test demonstrated that the CDCC group exhibited inhibitory zones against E. coli (Porous layer: ~1.54 mm, Dense layer: ~2.81 mm) and S. aureus (Porous layer: ~2.90 mm, Dense layer: ~6.94 mm), while no inhibitory zones were observed in the other groups, which can be attributed to the release of the antimicrobial agent CHX (Fig. 3A, B). This suggests that mild preparation conditions preserved the biological activity of CHX.

The antibacterial activity of samples against E. coli (A) and S. aureus (B) was evaluated using the inhibition zone method and the corresponding statistics of inhibition zone width (n = 9 biologically independent samples, Two-tailed Student’s t test, mean values ± SD). C Colony count of E. coli coated AGAR plate after bacterial penetration (n = 3 biologically independent samples, Two-tailed Student’s t test, mean values ± SD). D Colony count of S. aureus coated AGAR plate after bacterial penetration (n = 3 biologically independent samples, Two-tailed Student’s t test, mean values ± SD). The SEM images of E. coli (E) and S. aureus (F) treated by Col, Col-DCMC, and CDCC membranes (Scale bars: 5 μm). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The photographs and bacterial colony quantitative analysis showed a decrease in the viability of bacterial species cultured on the surface of the CDCC membrane, while bacterial viability remained consistently lower than other groups (Fig. 3C, D; Supplementary Fig. 21). Col-DCMC exhibited stronger resistance to bacterial infiltration than Col, attributed to its denser structure formed by crosslinking. The bacteria exhibited a normal shape in the Col and Col-DCMC group, while the membrane structures of bacteria were significantly destroyed and shrunken in the CDCC group (Fig. 3E, F). The high bacterial inhibition efficiency of the CDCC membrane is attributed to the rapid release of CHX and the protonation of guanidine groups on CHX, providing primary defense. This allows them to adsorb onto the permeation barrier of bacterial cell membranes, leading to the leakage of cell contents37. CHX has a bacteriostatic effect at low concentrations, while it shows a bactericidal effect at high concentrations. With a concentration of 10 μg/mL in the materials, the early rapid release effectively kills bacteria (1 day), while the later slow release of CHX maintains a bacteriostatic effect with minimal cell toxicity (2–20 days) (Fig. 2L). Additionally, the dense layer skeleton of the CDCC membrane serves to block any remaining viable bacteria that may penetrate the membrane and infect the underlying bone substitutes, establishing a secondary defense. Consequently, the surface of the CDCC membrane could shield the invasion of soft tissue and bacteria, and provide a guarantee for the formation of new bone.

Heterogeneity of the CDCC membranes

The primary function of the GBR membrane is to serve as a barrier, effectively preventing the invasion of soft tissue while creating a sealed environment conducive to the formation of new bone38. We initially evaluated the hemocompatibility and cytocompatibility of the membranes. Supplementary Fig. 22 showed that the hemolysis ratio values for all membranes were below the critical safe hemolysis ratio of 5% for biomaterials. Additionally, the results of CCK-8 testing and fluorescence microscope images suggested that all the membranes had almost no cytotoxicity within 72 h (Supplementary Fig. 23, 24). We conducted experiments using L929 fibroblasts to evaluate cell growth on each surface of the CDCC membrane, aiming to determine how surface topography influences cell movement (Fig. 4A, B). The 3D fluorescent images showed vigorous proliferation of fibroblast cells on the surface of both layers during the 7-day culture period, with markedly different infiltration depths (Fig. 4). On the porous layer, fibroblasts not only proliferated but also infiltrated the structure, extending to a maximum depth of approximately 480 μm (Fig. 4C–E). This infiltration highlights the porous layer’s capacity to support cell migration and penetration. In contrast, on the dense layer, fibroblasts were primarily confined to a narrow region near the dense surface layer, with a maximum infiltration depth of around 100 μm throughout the culture period (Fig. 4F–H). It suggested that the dense layer effectively prevents fibroblasts from infiltrating deeper into the material. The results indicated that the dense layer of the CDCC membrane acted as a barrier, hindering L929 cell penetration and potentially inhibiting the invasion of fibrous connective tissue into bone defects.

The schematic representation showed the different behaviors of cells on the porous layer (A) and the dense layer (B) of the CDCC membrane. C The 3D fluorescent images of L929 cells cultured on the porous layer of the CDCC membrane for 1, 4 and 7 days. D Infiltration depth of L929 cells in the porous layer (n = 10 biologically independent samples, Two-tailed Student’s t test, mean values ± SD). E Cell fluorescent intensity of L929 cells in the porous layer (n = 10 biologically independent samples, Two-tailed Student’s t test, mean values ± SD). F The 3D fluorescent images of L929 cells cultured on the dense layer of the CDCC membrane for 1, 4 and 7 days. G Infiltration depth of L929 cells in the dense layer (n = 10 biologically independent samples, Two-tailed Student’s t test, mean values ± SD). H Cell fluorescent intensity of L929 cells in the dense layer (n = 10 biologically independent samples, Two-tailed Student’s t test, mean values ± SD). Source data are provided as a Source Data file. Panels (A, B) created with BioRender.com released under a Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International license (https://BioRender.com/eeyc19f).

Furthermore, we analyzed the proliferation of MC3T3-E1 cells on the porous layer. Similarly, MC3T3-E1 cells were cultured on the surface of the porous layer, and stained cells were observed after specified incubation times using CLSM. Distinguishingly, we utilized both the pure collagen group (Col group) and the group where collagen was solely added with nHap (Col-nHap group) as controls for the CDCC group. This choice stemmed from the vital role of nHap in promoting bone cell growth. All membranes promoted MC3T3-E1 cell proliferation, with cells displaying a tendency to infiltrate and grow inward along the large pores (Supplementary Fig. S25, 26). Osteoblast proliferation on the porous surface of the CDCC membrane was higher than that on the porous surface of the Col group (Supplementary Fig. 26A). However, no significant difference (P = 0.3415) was observed in the depth of infiltration between the two groups (Supplementary Fig. 26B). It demonstrated that cell proliferation was enhanced in the 3D scaffold compared to cultivation on 2D surfaces. The porous structure likely facilitated proliferation by providing additional space for cell adhesion and promoting efficient nutrient transport. Moreover, the incorporation of nHap may support the growth of osteogenic cells, potentially enhancing osteogenesis upon interaction.

Osteoimmunomodulatory functions of the CDCC membrane

Persistent and severe inflammation in bone defect tissues can initially result in connective tissue damage and bone resorption, thus impeding bone regeneration even post-treatment. Evidence suggested that biomaterials possessing osteoimmunomodulatory properties can enhance bone formation through immune system regulation, offering an alternative avenue to promote bone regeneration39. Macrophages play a crucial role in regulating osteoimmunomodulation, primarily due to their ability to transition between pro-inflammatory M1 and pro-healing M2 macrophages. They influence the growth and differentiation of other cells such as osteoblasts, fibroblasts, and angioblasts through the release of cytokines. We anticipate that the porous layer of the CDCC membrane when positioned in the region of bone resorption, can establish an anti-inflammatory microenvironment that supports subsequent osteogenesis. This is facilitated by the capacity of the porous layer to locally deliver Cur, which possesses anti-inflammatory properties. Furthermore, previous studies have reported that the porous topology and hydrophilic surface of implants can induce an anti-inflammatory phenotype in immune cells40. Therefore, the hydrophilic porous surface of the CDCC membrane potentially serves as another cue to imbue the membrane with anti-inflammatory functionality.

To investigate the osteoimmunomodulatory functions of the CDCC membrane, we cultured macrophages on the porous layer of the CDCC membrane with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) to stimulate macrophages. Then we collected the medium after co-culturing and used it to culture bone mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs) to evaluate changes in osteogenic differentiation and signaling pathways of BMSCs (Supplementary Fig. 27). Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) serves as a marker for osteogenic differentiation. More significant ALP staining in the CDCC membrane group was observed, suggesting that the release of Cur impacted macrophage phenotype and subsequently influenced osteoblast differentiation (Fig. 5A, D). The utilization of Alizarin red S (ARS) staining as the second marker further demonstrated the promoting effect of CDCC membrane on the osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs under inflammatory conditions (Fig. 5B, E). Subsequently, the protein expressions of Osteocalcin (OCN), Runt-related transcription factor 2 (RUNX-2), Osteopontin (OPN), and Type I Collagen (COL-1) in osteoblasts were examined by western blot (Fig. 5C; Supplementary Fig. 28). The CDCC group displayed significantly higher protein expression levels of OCN (1.62 times), RUNX-2 (1.60 times), OPN (2.25 times), and COL-1 (3.31 times) compared to the LPS group (Fig. S28). Moreover, the CDCC group demonstrated significantly higher mRNA expression levels of osteogenesis-related genes including OCN (9.11 times), RUNX-2 (3.24 times), OPN (4.43 times), and COL-1 (4.17 times) compared to the LPS group (Fig. 5F).

A Typical digital photos of ALP activity by BMSCs (Scale bars: 400 μm). B Typical digital photos of mineralized nodules by BMSCs (Scale bars: 400 μm). C Western blot of osteogenic differentiation-related proteins (the samples derive from the same experiment). D quantitative analysis of osteogenic differentiation capacity after different treatments and staining with ALP (n = 3 biologically independent samples, Two-tailed Student’s t test, mean values ± SD). E Quantitative analysis of osteogenic differentiation capacity after different treatments and staining with Alizarin Red (n = 3 biologically independent samples, Two-tailed Student’s t test, mean values ± SD). F mRNA expression of the BMSCs detected by qPCR (n = 3 biologically independent samples, Two-tailed Student’s t test, mean values ± SD). G RNA similarity of Control group, LPS group, and CDCC group. H Venn diagram portraying differential gene counts in the Control group, LPS group, and CDCC group. I The dot-plot shows GO enrichment analysis of typical biological processes (CDCC group vs. LPS group). J Analysis of the differential gene enrichment within the KEGG pathway (CDCC group vs. LPS group). K Heatmap of target gene cluster analysis (CDCC group vs. LPS group). L The pathway of osteogenic gene activation by CDCC membrane under inflammation conditions. M The expression levels of CD86 (M1 marker) and CD206 (M2 marker) in the co-culture environment of BMDMs with different membranes under inflammatory conditions, as assessed by quantitative fluorescence analysis (n = 5 biologically independent samples, Two-tailed Student’s t test, mean values ± SD, scale bars: 10 μm). N The expression levels of CD86 (M1 marker), CD206 (M2 marker), and osteogenic markers (OCN, OPN, and Runx-2) in the co-culture environment of BMDMs and BMSCs with the different membranes, as assessed by quantitative fluorescence analysis (n = 5 biologically independent samples, Two-tailed Student’s t test, mean values ± SD, scale bars: 10 μm). Source data are provided as a Source Data file. Panels (L–N) created with BioRender.com released under a Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International license (5 L: https://BioRender.com/bmyjx52; 5 M: https://BioRender.com/eowc22r; 5 N: https://BioRender.com/fe5a3ve).

Mechanism of the CDCC membrane in promoting bone formation under inflammation

Based on the above promising therapeutic results of CDCC membrane in promoting bone defect repair, mechanistic studies were further conducted to elucidate the underlying biological processes and signaling pathways. Consequently, RNA-seq analysis was applied for BMSCs subjected to different treatments. Based on the empirical Bayes method (fold changes ≥1.5 and P < 0.05), differentially expressed genes (DEGs) including 780 down-regulated and 546 up-regulated genes were identified by comparing the inflammation model and CDCC groups, as implicated by the volcano plots (Supplementary Fig. 29). Similarly, the CDCC membrane influenced the expression of 4.53% of genes in BMSCs relative to the Model group (Fig. 5G, H). The affected genes are mainly involved in inflammatory response, response to hypoxia, and regulation of inflammatory response (Fig. 5I). Furthermore, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment results revealed significant effects on classic inflammation-related pathways, including the TNF signaling pathway, IL-17 signaling pathway, NF-kappa B signaling pathway, osteoclast differentiation, TGF-β signaling pathway, and others (highlighted in red in Fig. 5J). Reactome enrichment results revealed the interplay and regulation among molecules in biological processes, with the majority of DEGs concentrated in signal transduction and the immune system. It suggested that the CDCC membrane primarily affected cellular functions by influencing the expression and transduction of intercellular signaling factors in the immune system (Supplementary Fig. 30). The heatmap of DEGs further indicated that several key inflammatory genes (e.g., IL-1, GAB, etc.) were altered in pathways involved in inflammatory regulation (Fig. 5K). Therefore, we can hypothesize the mechanism of osteogenesis induced by CDCC membrane inflammation (Fig. 5L). It may be primarily as follows: The downregulation of IL-1 reduces IL-1 receptor expression on the cell membrane, indirectly regulating TRAF2/6. In contrast, the upregulation of TGF-β activates its receptors, further activating TRAF2/6. TRAF2/6 then binds with Gab-2 and PLCγ, triggering phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C and increasing IP3 production. As a second messenger, IP3 induces Ca²⁺ release from the endoplasmic reticulum, raising intracellular Ca²⁺ levels and activating CaMLIV. Activated CaMLIV enters the nucleus and enhances CREB activity, which, together with PPAR, upregulates c-Fos expression. Additionally, TRAF2/6 activates TAK1, which promotes MEK1 phosphorylation, leading to the activation of P38 MAPK. Activated P38 phosphorylates AP-1, facilitating its expression and nuclear translocation. In the nucleus, AP-1 forms a complex with c-Fos, regulating osteogenesis-related gene expression. In summary, the CDCC membrane regulated the inflammatory microenvironment and promotes bone regeneration through the synergistic interaction of the TGF-β and IL-1 pathways.

Direct regulation of osteoimmunomodulation by CDCC membrane under inflammatory conditions

Co-culture experiments were employed to further investigate the impact of membrane structure on macrophage differentiation and its effect on osteoblast differentiation under inflammatory conditions. Bone Marrow-Derived Macrophages (BMDMs) were seeded on the porous surface of the CDCC membranes and polarized with LPS, with BMDMs polarized with LPS and IL-4 in blank well plates used as controls. The results showed that BMDMs grown on CDCC membranes exhibited higher expression of CD206 than CD86 (CD86:CD206 = 0.022), similar to BMDMs polarized with IL-4, indicating that CDCC membranes can induce M2 polarization of BMDMs (CD86:CD206 = 0.029) (Fig. 5M; Supplementary Fig. 32, 33). After polarization with LPS, BMDMs grown on CDCC membranes also expressed higher levels of CD206 (CD86:CD206 = 0.029), unlike BMDMs polarized with LPS grown on Bio-Gide® membranes (CD86:CD206 = 38.60) and BMDMs polarized with LPS (CD86:CD206 = 5.14) (Fig. 5M; Supplementary Fig. 34, 35). This suggests that CDCC membranes promote a stronger M2 polarization of macrophages under inflammatory conditions.

Furthermore, to investigate the effect of CDCC membranes on osteogenic differentiation under inflammatory conditions, BMDMs, and BMSCs were co-cultured on the porous surface of the CDCC and Bio-Gide® membranes, with LPS used to induce an inflammatory environment. Similarly, cells polarized with LPS and IL-4 were used as controls. BMDMs with IL-4 (M2) significantly enhanced the expression of osteogenic-related proteins (OCN, OPN, and RUNX-2) in BMSCs compared to BMDMs with LPS (M1) (Supplementary Fig. 36). It suggested that the M2 macrophage environment is more favorable for osteoblast differentiation. The CDCC membrane exhibited higher expression of OCN (3.28 times), OPN (1.99 times), and RUNX-2 (7.49 times) compared to the Bio-Gide® membrane, which is likely related to the CDCC membranes’ ability to promote M2 polarization of BMDMs (Fig. 5N). More importantly, under LPS-induced inflammatory conditions, BMSCs grown on the CDCC membranes still exhibited high expression of osteogenic-related proteins, whereas the expression of these proteins was significantly reduced in BMSCs grown on the Bio-Gide® membrane (Fig. 5N). In summary, the CDCC membrane promoted osteogenic differentiation under inflammatory conditions by inducing macrophage polarization towards the M2 phenotype.

In vivo biocompatibility evaluation of the CDCC membrane

Preliminarily, we evaluated the in vivo biocompatibility of the CDCC membrane through subcutaneous implantation, with the Bio-Gide® membrane as the comparison group (Fig. 6A). During the observation period, all rats remained healthy, with no surgery-related infections or complications. Histological examination of the organs (Supplementary Fig. 38) and blood tests showed no abnormalities in rats implanted with different membranes (Supplementary Fig. 39, 40). After 1 and 2 weeks of surgery, the expression levels of inflammation-related proteins (IL-1, TNF-α, and TGF-β) were assessed through immunohistochemical (IHC) staining (Fig. 6B, C; Supplementary Fig. 41, 42). The results revealed varying changes in the expression of the aforementioned three inflammatory proteins at different time points implanted in rat subcutaneous between the Bio-Gide® treated group and the CDCC-treated group. The expression levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and TNF-α exhibited a gradual increase in the Bio-Gide® treated group over time. In contrast, the CDCC-treated group showed a notable decrease in the expression of both IL-1β and TNF-α, with levels reduced by 11.71% and 38.99%, respectively (Fig. 6B; Supplementary Fig. 42). The results demonstrated that the CDCC membrane effectively mitigates the inflammatory response induced by the implantation of allogeneic materials and promotes a more favorable healing environment. Meanwhile, TGF-β, known as an anti-inflammatory factor, functions in contrast to its homolog TNF-α, regulating immune responses and cell proliferation41. Consistently high TGF-β expression was observed in the CDCC-treated group, with levels 1.80 and 1.75 times higher than the Control group at Week 1 and Week 2 of subcutaneous implantation, respectively (Fig. 6B; Supplementary Fig. 42). The results demonstrated that the CDCC membrane exhibits favorable biocompatibility and effectively modulates the inflammatory response induced by implant insertion, with the potential to establish a conducive microenvironment for bone repair.

A Schematic diagram of the rat subcutaneous implantation. B Immunohistochemistry staining photographs of IL-1β, TNF-α and TGF-β at 2-weeks post-subcutaneous implantation in rats (Scale bars: 20 μm). C Quantitative analysis of IL-1β, TNF-α and TGF-β levels. D Schematic diagram showing the rat calvarial defects model to assess in vivo osteogenic ability. E Micro-CT images of the calvarial defects at 4-weeks and 8-weeks post-surgery. Quantitative analysis of micro-CT images including (F) BV/TV, (G) Tb. Th and (H) Tb. Sp (n = 5 biologically independent samples, Two-tailed Student’s t test, mean values ± SD). Quantitative analysis of (I) H&E staining and (J) Masson’s trichrome staining (n = 5 biologically independent samples, Two-tailed Student’s t test, mean values ± SD). K H&E staining and (L) Masson’s trichrome staining for the evaluation of bone regeneration (Scale bars: 1 mm). Source data are provided as a Source Data file. Panels (A, D) created with BioRender.com released under a Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International license (6 A: https://BioRender.com/48ek7vt; 6D: https://BioRender.com/hqo8tos).

In vivo bone repair function of the CDCC membrane

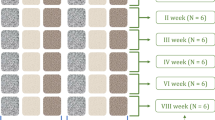

The functionality of the CDCC membrane was evaluated in vivo using a rat cranial critical-size defect model. To minimize errors between individual rats, both inter-group and intra-group controls were conducted (Fig. 6D; Supplementary Fig. 43). The representative micro-computed tomography (micro-CT) images showed that the Model group exhibited minimal new bone regeneration, whereas, in the membrane-covered groups, the defects were filled with a significant amount of regenerated bone (Fig. 6E). Especially noteworthy is the fact that, in both the 4-weeks and 8-weeks assessments, the CDCC-treated group exhibited a significantly greater degree of new bone regeneration compared to the Bio-Gide® treated group (Fig. 6E). Bone volume fraction (BV/TV) represents the ratio of bone tissue volume to total tissue volume, which directly reflects changes in bone mass42. The results demonstrated that the CDCC-treated group exhibited the highest BV/TV ratio at 8 weeks post-surgery, with a value of 25.22% (21.67% in the Bio-Gide® treated group, and 11.97% in the Model group) (Fig. 6F). The semi-quantitative assessment of trabecular thickness (Tb. Th) and trabecular separation (Tb. Sp) can reflect the morphological reconstruction of the bone43. Generally, a smaller Tb. Sp corresponds to a higher Tb. Th. The results indicated that the rats implanted with the CDCC membrane had a significant regeneration of bone, which was not observed in untreated animals (Fig. 6G). Additionally, the CDCC-treated group (~187.88 µm) exhibited a significantly smaller Tb. Sp compared to the Bio-Gide® treated group (~208.66 µm) (Fig. 6H). To further investigate the bone repair capability of the membranes, histological analyses of newly formed bone were performed by H&E staining and Masson’s trichrome staining (Fig. 6I–L). In the CDCC membrane group, increased trabecular bone and more mature bone marrow cavities were observed within the defect area, along with notable collagen deposition (Fig. 6J). In summary, these results suggested that the CDCC membrane exhibited superior bone repair compared to the Bio-Gide® membrane. This is likely attributed to the antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, and osteogenic properties conferred by the porous topology and loaded nanomicelles component of the CDCC membrane.

In vivo early inflammatory response of the CDCC membrane

A rat cranial infectious defect model (Fig. 7A) was used to further elucidate the impact of CDCC on early immune responses during bone regeneration under infectious conditions44. During the observation period, all rats remained healthy, with no surgery-related infections or complications. Histological examination revealed no abnormalities in organs at 1-week and 2-weeks post-implantation (Supplementary Fig. 44, 45). The CDCC membrane maintains high antibacterial efficacy in vivo, providing an effective resistance to bacterial penetration and a sterile environment for underlying bone substitutes (Fig. 7B; Supplementary Fig. 46). After 2-weeks post-implantation, micro-CT data showed that the bone volume fraction (BV/TV) value of the CDCC membrane treated group was 3.18 and 2.36 times higher than those in the Model group and Bio-Gide® treated group, respectively (Fig. 7C–E; Supplementary Fig. 47). Additionally, micro-CT images revealed that the CDCC membrane supported the bone defect site and degraded gradually while maintaining its shape. Significantly greater new bone formation and collagen deposition were observed in the CDCC-treated group compared to the other groups in the cranial infectious defect model (Fig. 7F; Supplementary Fig. 48, 49).

A Schematic diagram showing the process of creating rat calvarial defect models to assess in vivo immune regulation ability under bacterial conditions. B Colony count of S. aureus on agar plates after sacrifice (n = 5 biologically independent samples, Two-tailed Student’s t test, mean values ± SD). C Micro-CT 3D reconstructions and coronal views of new bone formation within bone defect sites at 1-week and 2-weeks post-implantation in bacterial models. Quantitative analysis of bone parameters including (D) BV/TV and (E) Tb. Sp (n = 5 biologically independent samples, Two-tailed Student’s t test, mean values ± SD). F Quantitative analysis of collagen deposition in bone remodeling site (n = 5 biologically independent samples, Two-tailed Student’s t test, mean values ± SD). G Representative immunofluorescence images for surface markers including CD86 (red, M1 phenotype) and CD206 (green, M2 phenotype) at 1-week and 2-weeks post-implantation (Scale bars: 1 mm). H Quantitative analysis of the ratio of CD86 to CD206 expression (n = 5 biologically independent samples, Two-tailed Student’s t test, mean values ± SD). I Representative immunohistochemistry staining revealed the expression of IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and TGF-β in different groups at post-implantation in infected cranial defect model (Black arrows: new bones, Scale bars: 200 μm). J Quantitative analysis of immunohistochemistry staining at 1-week and 2-weeks (n = 5 biologically independent samples, Two-tailed Student’s t test, mean values ± SD). K Representative immunofluorescence images revealed the expression of OCN, OPN, CD31, and VEGF in different groups (White arrows: new blood vessels, Scale bars: 1 mm). L Quantitative analysis of immunofluorescence at 1-week and 2-weeks (n = 5 biologically independent samples, Two-tailed Student’s t test, mean values ± SD). Source data are provided as a Source Data file. Panel (A) created with BioRender.com released under a Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International license (https://BioRender.com/qdicg56).

To better understand the effects of the CDCC membrane on the inflammatory responses and macrophage activation during infected bone regeneration, we further performed immunofluorescence (IF) staining and IHC staining in defect areas after 1 and 2 weeks of implantation (Fig. 7G–J). The ratio of CD86/CD206 in the CDCC-treated group (week 1: 0.55 ± 0.19, week 2: 0.30 ± 0.26) was much lower than that in the Bio-Gide®-treated group (week 1: 11.45 ± 3.14, week 2: 94.83 ± 68.91) and Model group (week 1:7.61 ± 3.81, week 2: 42.43 ± 35.11) (Fig. 7H; Supplementary Fig. 50). It demonstrated that the CDCC-treated group exhibited a higher expression of M2 macrophages, whereas the Bio-Gide®-treated group and Model group showed a higher expression of M1 macrophages. The same tendency was detected in the percentage of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α. In addition, a significantly higher proportion of anti-inflammatory cytokine TGF-β was observed in the CDCC-treated group (week 1: 17.25 ± 6.67%, week 2: 25.38 ± 8.25%) compared to the Bio-Gide®-treated group (week 1: 0.39 ± 0.10%, week 2: 10.13 ± 2.31%) and Model group (week 1: 0.80 ± 0.36%, week 2: 9.44 ± 1.52%) after 1 and 2 weeks of implantation in infected cranial defect model (Fig. 7I, J). These results indicated that post-implantation of the CDCC membrane into the infected calvarial defects provoked M2 macrophage polarization, which alleviated inflammation status and promoted the bacteria-infected bone regeneration. Further investigation of osteogenic proteins (OCN and OPN) around the surgical site revealed that these proteins were more likely to be expressed at cranial defects after treatment with the CDCC-treated group (Fig. 7K-L). The results showed that compared to the Bio-Gide® treated group, the CDCC-treated group showed significantly higher expression of OCN (22.53 times) and OPN (14.76 times) after 2 weeks of treatment (Fig. 7L). This suggested that the CDCC membrane had superior osteogenic capacity in the cranial infectious defect model. Moreover, the skull treated with the CDCC-treated group exhibited high expression of vascular proteins, including CD31 and VEGF, which were significantly higher than those observed in the other two groups (Fig. 7L). In conclusion, the CDCC membrane exhibited robust antibacterial, immunoregulatory, angiogenic, and osteogenic properties.

In this study, we fabricated a Janus collagen-based GBR membrane with a porous and dense layer. The membrane integrated osteogenic, antibacterial, controlled release, and osteoimmunomodulatory functions together. The porous layer of the membrane promoted direct osteogenic differentiation of the osteoblasts. The dense layer of membrane prevented soft tissue incursion and protected bone defects from bacterial infection. In addition to its barrier function on fibroblasts, the membrane also synergistically regulates the immune microenvironment to promote the osteogenic differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells through the IL-1 and TGF-β pathways. Cranial defect experiments confirmed that the membrane exhibited superior bone regeneration performance in vivo compared to the Bio-Gide® membrane. Infected calvarial defect experiments further demonstrated that the membrane could regulate the early immune microenvironment of bone repair. Therefore, our work might provide a promising strategy for the design of bioactive GBR membranes for bone regeneration clinically.

Methods

Ethical statement

All animal protocols in this study were approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Sichuan University (approval NO. KS2023311), and performed according to the guidelines of the Council for the Purpose of Control and Supervision of Experiments on Animals, Ministry of Public Health, China.

Animals

Eight-week-old female Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats with average weight ranging between 200 g and 270 g were purchased from Chengdu Dashuo Laboratory Animal Co., Ltd. (Chengdu, China). SD rats were housed on a 12/12 light/ dark cycle with constant temperature (22 °C) and humidity (50-60%). During the experimental period, the SD rats had free access to water and food. In animal experiments, each group consisted of 5 SD rats.

Preparation of Cur@Chol-PEG NMs

Cur@Chol-PEG NMs were fabricated using the method proposed in our previous work with modification25. The 1.0 g of polyethylene glycol (PEG) with a molecular weight of 2000 was mixed with 25.0 g of molten imidazole. After stirring for 30 min, 0.225 g of cholesteryl chloroformate (Chol) was added to the mixture. The above mixture was continuously stirred at 100 oC for 1 h, and the reaction was terminated by adding 50.0 mL of deionized water. The resulting mixture was dialyzed (MWCO = 2000 Da) against deionized water for 3 d, and finally freeze-dried to obtain amphiphilic polymer Chol-PEG.

The emulsification-thin film dispersion method was used to prepare Cur@Chol-PEG NMs. The oil phase was prepared by mixing 5.0 mg of curcumin (Cur), 80.0 mg of Chol-PEG, and 5.0 mL of CH2Cl2 in an ice bath under ultrasonic treatment. The whole oil phase was added into 50.0 mL of deionized water. The mixture was homogenized using a high-speed homogenizer (T18, IKA, Germany) at 18553 g for 5 min to obtain an emulsion. Then the emulsion was completely evaporated at 45 °C using a rotary evaporator (R-300, BUCHI, Switzerland). Afterwards, the product was dissolved in 20.0 mL of deionized water, and filtered through a 0.45 μm microfiltration membrane. Finally, the Cur-loaded nanomicelles (Cur@Chol-PEG NMs) were obtained after freeze-drying. The nanomicelles without loading Cur were also prepared according to the above method and named Chol-PEG NMs.

Characterization of Cur@Chol-PEG NMs

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR, Nicolet iS50, Thermo Scientific, USA) and 1H NMR spectrometer (DD2 400-MR, Agilent, USA) were used to detect the chemical substructure of samples. The morphology of samples was observed using field emission transmission electron microscopy (TEM, HT7700, Hitachi, Japan). For TEM analysis, the samples were uniformly dispersed in deionized water using low-temperature sonication and then added dropwise to a copper mesh. The particle size distributions were calculated from their TEM images by Nano Measure software. A Nano Zetasizer (ZS90, Malvern Instruments Ltd., U.K.) was employed to determine the hydrodynamic size of samples. To gain insight into their scattering properties, 5 mg/mL solutions of Cur and Cur@Chol-PEG NMs were prepared, exposed to light, and photographed to observe the Tyndall effect. Cur loading capacity and encapsulation efficiency of Cur@Chol-PEG NMs were determined using ultraviolet spectrophotometry. Cur@Chol-PEG NMs were suspended in ethanol, treated with ultrasound, and centrifuged. The absorbance of the supernatant at 425 nm was measured using a UV–vis spectrophotometer (A360, AOYI Instruments Shanghai CO. LTD., China). Cur drug loading capacity and encapsulation efficiency were then calculated using specified equations.

Isolation of collagen and the preparation of dialdehyde carboxymethyl cellulose (DCMC)

Collagen type I was isolated from the fresh adult bovine Achilles tendon using an acetic acid-pepsin method45. The sodium periodate oxidation method was used to prepare the crosslinking agent DCMC according to our previous work with modification29. The 4.0 g of carboxymethyl cellulose was dissolved in 100.0 mL of deionized water, followed by adding 50.0 mL of sodium periodate aqueous solution (0.080 g/mL) under stirring. The pH value of the mixture was adjusted to 3.0 using 1.0 M sulfuric acid solution. The mixtures were continuously stirred at 45 oC for 4 h in dark. The oxidized sample was obtained by alcohol precipitation, and then dialyzed against deionized water using 3 kDa cut off dialysis tubing to completely remove the iodide. The DCMC was obtained after freeze-drying.

Preparation of CDCC membrane

Collagen type I was dissolved in 0.05 M acetic acid (Hac) solution to prepare a 0.50% (w/v) collagen solution. Cur@Chol-PEG NMs (preparation method was described in Supporting Information) and chlorhexidine acetate (CHX) were introduced into the collagen solution to attain concentrations of 1 mg/mL for Cur and 10 μg/mL for CHX. Nano-hydroxyapatite (nHap) was added to the collagen solution to achieve a mass ratio of 4:6 between collagen and nHap. The solutions were mixed evenly under the ice bath and their pH was adjusted to 6.0. Then DCMC solution was introduced to attain a 100:1 ratio of collagen to DCMC. The resulting pre-porous layer solution was reserved for future use.

Degraded collagen peptides (without triple helix structure) were dissolved in deionized water to prepare a 10% (w/v) solution. Cur@Chol-PEG NMs and CHX were introduced into the degraded collagen peptides solution to attain concentrations of 1 mg/mL for both Cur and CHX. Then the pH of the solution was adjusted to 6.0. Following this, a DCMC solution was introduced to attain a 100:1 ratio of degraded collagen peptides to DCMC. The resulting pre-dense layer solution was reserved for future use.

The pre-dense layer solution was first cast into the bottom of a polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) mold. Water evaporation was conducted for 12 h in a constant-temperature environment at 45 °C. Subsequently, the pre-porous layer solution was added onto the surface of the pre-dense layer solution. The sample was rapidly frozen in liquid nitrogen for 60 seconds. The CDCC membrane was obtained after freeze-drying. The Janus membranes of collagen crosslinked with DCMC (Col-DCMC), collagen with only nHap (Col-nHap), and uncrosslinked pure collagen (Col) were also prepared.

Characterization of the CDCC membranes

The morphology and chemical components of samples were detected using field emission scanning electron microscopy equipped with an energy-dispersive spectroscope (SEM, SIGMA500, ZEISS, German). Before SEM characterization, the CDCC samples were gold-coated. The surface roughness of both sides of CDCC was tested using atomic force microscopy (AFM, Dimension Icon, Bruker, USA) with a scan rate of 0.4 Hz. The obtained property maps were analyzed using NanoScope software. The static water contact angles (WCAs) were measured by a contact angle analyzer (DSA30, KRUSS, German) at room temperature. WCAs were investigated to characterize the hydrophobicity of the CDCC.

The mechanical properties and interlayer binding forces of each sample were measured using an electronic universal testing machine (CMT6202, MTS Systems Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). This included the standard tensile test (tensile properties, ASTM D882), the standard T-peeling test (ASTM D1876), the standard lap-shear test (ASTM F2255), and the standard tensile test (adhesive strength, ASTM F2258).

The tensile strength (TS) and elongation at break (EB) of the samples were calculated by the Eqs. (1) and (2):

where Fmax is the maximum force (N) of the machine load to pull the sample apart, A is the cross-sectional area (m2) of the samples (For adhesive strength measurement, A is the adhesive area (m2)), and L is the elongation of the sample (mm) at the moment of rupture.

The interfacial toughness was calculated by the Eq. (3):

where Fp is the plateau force (N) of the T-peeling test, and W is the width (m) of the samples.

The shear strength was calculated by the Eq. (4):

where Fmax is the maximum force (N) of the lap-shear test, and A is the adhesive area (m2) of the samples.

A gravimetric method was used to examine the swelling behavior of samples31. The dry samples were cut into the same size and then weighed and recorded. Subsequently, all samples were soaked in PBS (pH 7.4), Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS), and Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) solutions at 37 oC for 6, 18, and 24 h. At each time point, the excess liquid on the surface of the samples was removed, and the samples were weighed and recorded. The in vitro biodegradation rate of samples was evaluated according to the previous literature46. The samples were incubated at 37 oC in 10 mL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH=7.4) containing 2 U/mL protease XIV. Solutions were replaced daily, and the samples were freeze-dried for dry weight at designated time points. The mass retained was calculated by comparing the dry weight remaining at that time point with the initial dry weight.

Assessment of the antibacterial activity

Preparation of bacterial suspension: Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus, ATCC 25923, USA) and Escherichia coli (E. coli, ATCC 25922, USA) with 1×104 CFU/mL were used for the antibacterial measurement. S. aureus and E. coli were cultured in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium at 37 oC. The final bacterial suspension was diluted with sterile saline culture medium to a density of 1×109 CFU/mL.

Inhibition zone method: The 100 μL of S. aureus and E. coli suspension (109 CFU/mL) were uniformly spread on LB agar plates, respectively. Then the rounded samples (10 mm in diameter) after ultraviolet sterilization were gently placed on the surface of LB agar and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. The bacteria-free zones surrounding the rounded samples were measured and used to evaluate the antibacterial capacity of the samples.

Bacterial infiltration: Bacterial infiltration through samples was studied to evaluate the antibacterial properties of samples again. The rounded samples (10 mm in diameter) after ultraviolet sterilization were placed on the surface of LB agar. Then 100 μL of S. aureus and E. coli suspension (109 CFU/mL) were dropped on the surface of samples, respectively, and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. The growth of bacteria on the surface of samples was recorded by camera. Moreover, the samples containing bacteria were collected and fixed with 2.5% (v/v) glutaraldehyde for 2 h at 4 °C. After that, the samples were washed with PBS (pH=7.4) and dehydrated using a graded series of ethanol followed by freeze-drying. The morphologies of bacteria on the surface of samples were observed by SEM after coating with Au. Furthermore, the LB agar under the samples was taken out and put into 25 mL of sterile water to obtain bacterial suspension. Then 100 μL of the above bacterial suspension were uniformly spread on new LB agar plates and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h again. The growth of bacteria was recorded to further detect the number of bacteria infiltrating through the samples.

Hemocompatibility evaluation

Samples were positioned in test tubes, followed by adding 10 mL of saline. Afterward, a 0.2 mL aliquot of freshly prepared ACD blood was integrated into the mixture, carefully agitated, and held at 37 °C for 1 h. Post-centrifugation at 440 × g for 5 min, the clear liquid atop the sediment was collected and moved to a cuvette. A spectrophotometer was employed to measure the absorbance of each sample at 545 nm. Concurrently, erythrocytes treated with saline (0% hemolysis) and deionized water (100% hemolysis) were served as reference points as negative and positive control groups, respectively. The hemolysis ratio (HR) was calculated as by the Eq. (5):

where Asample, Apositive and Anegative are the absorbance values of test group, positive and negative groups, respectively.

Characteristics of regulating cell behavior

Cell culture: The mouse-derived cell line of L929 fibroblasts were cultured in dulbecco’s modified eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (PS). And the mouse-derived cell line of MC3T3-E1 osteoblasts were cultured in α-minimum essential medium (α-MEM) supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% PS. The above cells were cultured at 37 °C in an atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2. The culture medium was changed every two days.

Cytotoxicity assessment and cell proliferation: Samples were soaked in the same complete medium for 24 h to obtain an extract liquid (0.1 g/mL). After filtration through sterile syringe filters (45 mm), the extract liquid was stored at 4 °C for future use. Cells were firstly seeded in 24-well plates containing 300 μL of complete medium and cultured for 24 h. Then 300 μL of extract liquid was employed to replace the original medium and incubated for another 24 h and 72 h. The cell viability was tested according to the instructions using CCK-8 assay. Cells were stained with Dio, and their morphology was observed using a fluorescence microscope (CKX53, Olympus, Japan). The viabilities rate of the cells was calculated by the Eq. (6):

where ODi, ODb, and ODc are the optical density of the experimental group, blank group, and control group, respectively.

Barrier function assessment (Cell penetration): L929 cells at a density of 104 cells per well were seeded onto the dense layer and porous layer respectively. After 2 h of incubation, once cells fully adhered to the sample surface, the culture medium was replaced with fresh medium. The medium was changed every 2 days. After culturing for 1, 4, and 7 days, the cytoskeleton and nucleus of the cells were stained with phalloidin-Alexa Fluor 488 and 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), respectively. Then, confocal laser scanning microscope (CLSM, Leica, Germany) was used to observe the cell penetration, and 3D fluorescent images were obtained. ImageJ software was applied for quantitative analysis.

In vitro evaluation of osteogenic function under inflammatory conditions

Cell culture: The RAW264.7 macrophages were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 15% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (PS). The bone mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs) were cultured in α-minimum essential medium (α-MEM) supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% PS. The above cells were cultured at 37 °C in an atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2. The culture medium was changed every two days.

Inflammatory condition medium collection: To collect inflammatory condition culture-medium, the RAW264.7 cells were seeded onto the outer faces of the membranes in 6-well plates with a density of 105 cells per well. After culturing for 2 h, the original medium was replaced by the induction medium containing lipopolysaccharide (LPS, 1 µg/mL) to activate inflammatory macrophages. 2 h later, the induction medium was replaced by 6 mL of DMEM. After 6 h, the medium in the 6-well plates was collected and centrifuged to obtain the supernatant as the conditioned medium for further testing. Meanwhile, RAW 264.7 cells were detached by trypsin after culture and rinsed with 1% BSA/PBS at 4 oC. The RAW 264.7 cells seeded on the blank plate served as control. The nonspecific protein binding was blocked by CD16/32 in advance. Then, all samples were incubated with PE-conjugated CD86 antibody (1:100) and FITC-conjugated CD206 antibody (1:100) for 30 min at 4 oC. After washing with 1% BSA/PBS, samples were measured by a flow cytometer (Beckman coulter, USA), and the acquired data were analyzed by FlowJo software (Treestar, USA).

Osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs under inflammatory conditions: To investigate the effect of CDCC/macrophage conditioned medium on the osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs, BMSCs were seeded onto the 6-well plates and cultured in the conditioned medium to mimic the immune environment in vivo.

Mineralization evaluation: On day 7 after osteogenic induction, BMSCs were washed 3 times with PBS, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, and stained with the BCIP/NBT ALP staining kit. On day 21 post osteogenic induction, BMSCs were washed 3 times with PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. Then, 2% Alizarin Red was applied to stain calcium deposition. After staining, BMSCs were washed 3 times with deionized water and observed under a phase-contrast microscope. ImageJ software was applied for quantitative analysis.

Quantitative PCR: After incubation for 7 days, the osteogenic-related genes (OPN, OCN, RUNX-2, COL-1) in BMSCs were measured by qPCR as mentioned above. Relative levels of different genes were determined by using the ΔΔCt method and normalizing to the housekeeping gene β-ACTIN. Sequences of primers for qPCR:

GENE | Forward 5’-3’ | Reverse 5’-3 |

|---|---|---|

β-ACTIN | CAGCCTTCCTTCYYGGGTATG | GGCATAGAGGTCTTTACGGATG |

OPN | GATGAACAGTATCCCGATGCCA | GTCTTCCCGTTGCTGTCCTGA |

OCN | TGACAAAGCCTTCATGTCCAA | CTCCAAGTCCATTGTTGAGGTAG |

RUNX-2 | TACCCAGGCGTATTTCAGATGAT | TGTAAGTGAAGGTGGCTGGATAGT |

COL-1 | CCCAGCGGTGGTTATGACTT | TCGATCCAGTACTCTCCGCT |

Western blotting analysis: Total proteins were extracted with RIPA containing 1% PMSF and the protein concentrations were examined by BCA Protein Assay Kit. Then, the proteins (30 μg/lane) were separated by 10% (wt/vol) SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes. After blocking with 5% fat-free dry milk in TBST (TBS with 0.1% Tween-20) for 30 min at room temperature, the membranes were separately incubated with primary antibodies against β-ACTIN, OPN, OCN, RUNX-2, or COL-1 at 4 °C overnight. Then, the membranes were washed with TBST and incubated with the corresponding horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies at room temperature for 30 min. Subsequently, the membranes were washed again with TBST, and the signals were visualized with the Immobilon Western Chemiluminescent HRP Substrate. Protein bands were analyzed with ImageJ software. The antibody information used was shown in Supplementary Table 4.

Transcriptome sequencing of BMSCs after treatment with CDCC: BMSCs were seeded in 6-well plates, followed by treatment with or without the conditioned medium to mimic the immune environment in vivo for 7 days. After digestion of BMSCs using pancreatic enzymes, samples were collected by centrifugation. Total RNA was extracted from BMSCs by the standard Trizol extraction method. Then, cDNA samples were sequenced using an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 system by Majorbio Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China). The sequencing data were filtered with SOAPnuke (v1.5.2) by: (1) Removing reads containing the sequencing adapter; (2) Removing reads whose low-quality base ratio (base quality less than or equal to Q-score) is over 20%; (3) Removing reads whose unknown base (‘N’ base) ratio is over 5%. Afterward, clean reads were obtained and stored in FASTQ format. The clean reads were mapped to the reference genome using HISAT2 (v2.0.4). Bioinformatics data was analyzed based on the gene expression profiles across different samples.

In vitro macrophage polarization induced by CDCC membrane

The Bone Marrow-Derived Macrophages (BMDMs) were extracted from the bone marrow of rats. Briefly, primary bone marrow cells extracted from the bone marrow of rats were seeded onto the porous surface of the CDCC membrane at a density of 5×10⁴ cells/cm² and cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10 ng/mL of M-CSF. LPS (100 ng/mL) was used to stimulate the cells and induce M1-type BMDMs, and IL-4 (10 ng/mL) was used to stimulate the cells and induce M2-type BMDMs. To comprehensively evaluate the immunomodulatory effects, BMDMs cells were cultured for 2 days and then analyzed using immunofluorescence (IF) staining to assess M1/M2 polarization markers (CD86, CD206). The BMDMs were directly cultured in the well plates and polarized into M1 and M2 types to serve as controls. The antibody and repair condition used were shown in Supplementary Table 4.

In vitro osteogenic differentiation induced by CDCC membrane

To more accurately mimic the osteogenic microenvironment under inflammatory conditions, BMDMs and BMSCs were co-cultured on the porous surface of the CDCC membrane. Initially, BMDMs were seeded onto the surface of the CDCC membrane, and subsequently polarized into Mø and M1 types, respectively. Next, BMSCs were seeded onto the surface of the CDCC membrane, allowing BMSCs and BMDMs to co-culture on the membrane surface. Once the cells had adhered to the membrane surface, the culture medium was replaced with the osteogenic induction medium, and the cells were cultured for 14 days, with the medium being replaced every 2 days. IF staining (OPN, RUNX-2, and OCN) was performed after 14 days to analyze the expression of osteogenic target proteins in the BMSCs. IF staining (CD86, CD206) was performed after 14 days to analyze M1/M2 polarization markers in the BMDMs. The BMDMs and BMSCs were co-cultured on the Bio-Gide® membrane and a blank well plate as the control group. The antibody and repair condition used were shown in Supplementary Table 4.

In vivo biocompatibility assessment

Material preparation and animal grouping: The in vivo biocompatibility of CDCC was evaluated by rat subcutaneous implantation, and untreated healthy rats were used as control. Before implantation, the samples were trimmed to a size of 1×1 cm and sterilized in ultraviolet and ozone for 1 h. Samples were subcutaneously implanted into the backs of SD rats (between the skin and muscle). Skin biopsies including the implants were harvested for histological analysis after 1 and 2 weeks, respectively. The biopsies were fixed, dehydrated, embedded in paraffin, and cut into 5 µm thick transverse sections. Then, the sections were subjected to immunohistochemical (IHC) staining, hematology test, hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) stain of important organs and to evaluate histocompatibility.

IHC staining: Samples were deparaffinized and rehydrated. Endogenous peroxidase was blocked with 3% hydrogen peroxide for 10 min, followed by antigen retrieval and blocking with goat serum. Primary antibodies (IL-1β, TNF-α, TGF-β) were added and left to incubate overnight at 4 °C. After washing with PBS, secondary antibodies were applied for 30 min. DAB chromogen was added for color development, followed by staining with hematoxylin, differentiation, counterstaining, and dehydration. Slides were mounted and observed under a microscope. The antibody and repair condition used were shown in Supplementary Table 4.

Hematology tests: At 2 weeks post-operation, blood samples were collected via the abdominal aorta of the rats for hematological, hepatic, and renal function tests. Hematological parameters of the blood drawn from the catheter in the carotid artery were determined using a hematology analyzer. The collected blood was centrifuged at 158 g for 10 min at 4 °C. After centrifugation, the supernatant was obtained and subjected to biochemical analysis using a fully automated biochemical analyzer.

Histological analysis of important organs: At 2 weeks post-operation, SD rats were euthanized by exsanguination. Hearts, livers, spleens, lungs, and kidneys were harvested from the euthanized rats, and paraffin sections were prepared for H&E staining.

H&E staining: Samples were dehydrated in graded alcohol, embedded in paraffin wax, and sectioned at a thickness of 4 μm. Three sections containing the central areas of each defect from the sagittal surface of the specimens were used for the histomorphometric analysis. Then the sections were stained with H&E and observed under light microscopy (DM500, Leica, Germany).

In vivo bone repair evaluation

A diameter of 5 mm trephine was used as a mold to make the samples into circular membranes (d = 5 mm). SD rats were randomly allocated into the following groups: (A) CDCC membrane, (B) Bio-Gide® membrane (positive control), (C) Blank control. The SD rats were weighed and anesthetized via intraperitoneal injection of 2% pentobarbital sodium at a dosage of 3 mg/kg. A 1.5 cm sagittal incision was made on the scalp, and the calvarium was exposed. A circular defect was created in the calvarium using a trephine of 5 mm diameter under irrigation with 0.9% NaCl (Create two symmetrical defects in one rat for intergroup comparison control). Different samples were implanted into the defects without covering other materials on the surface, and no materials were placed in the blank control group. After 4-week and 8-weeks post-operation, the animals were euthanized under general anesthesia. The skulls containing experimental sites were collected and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 48 h. Then harvested samples were immersed in 75% ethanol for subsequent tests.