Abstract

The selection of genetically engineered immune or hematopoietic cells in vivo after gene editing remains a clinical problem and requires a method to spare on-target toxicity to normal cells. Here, we develop a base editing approach exploiting a naturally occurring CD33 single nucleotide polymorphism leading to removal of full-length CD33 surface expression on edited cells. CD33 editing in human and nonhuman primate hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells protects myeloid progeny from CD33-targeted therapeutics without affecting normal hematopoiesis in vivo, thus demonstrating potential for improved immunotherapies with reduced off-leukemia toxicity. For broader application to gene therapies, we demonstrate highly efficient (>70%) multiplexed adenine base editing of the CD33 and gamma globin genes, resulting in long-term persistence of dual gene-edited cells with HbF reactivation in nonhuman primates. Using the CD33 antibody-drug conjugate Gemtuzumab Ozogamicin, we show resistance of engrafted, multiplex edited human cells in vivo, and a 2-fold enrichment for edited cells in vitro. Together, our results highlight the potential of adenine base editors for improved immune and gene therapies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

There is increasing interest in immunotherapeutic strategies to treat cancer, with a growing list of drugs approved for clinical use. Because of the lack of cancer-specific antigens as suitable targets for immune and gene therapies in many instances, on-target toxicity to normal cells is a major safety concern with such therapies. For example, with treatments for hematologic malignancies, expression of target antigens on normal hematopoietic cells can lead to prolonged, severe myelosuppression and associated adverse sequelae such as hypogammaglobulinemia and/or life-threatening/limiting bleeding or infection. For immunotherapy directed at CD33, a myeloid differentiation antigen expressed broadly on neoplastic cells in patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML), we and others proposed to create a specific leukemia antigen by using CRISPR/Cas9 to engineer CD33-negative normal donor hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs)1,2,3. Ablation of CD33 on HSPCs did not alter functionality or hematopoietic repopulation capacity and conferred resistance to CD33-targeted immunotherapies like the clinically approved CD33 antibody-drug conjugate Gemtuzumab Ozogamicin (GO) or CD33-directed chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells in vitro and in vivo. CRISPR/Cas9 has proven very efficient at editing genes, but its double strand break (DSB)-based mechanism has been associated with adverse consequences such as p53 activation, large insertions/deletions, and chromosomal translocations in some cell types including HSPC4,5,6,7. While the off-target assessment of our previous study1 did not uncover deleterious mutations in CRISPR/Cas9-edited HSPCs, the long-term effects of a lineage marker knockout in hematopoietic cells remain uncertain. Furthermore, simultaneous multiplex gene editing to engineer more than a single gene could lead to DSBs in multiple genes that increases the risk of translocations of unknown, and potentially deleterious, function.

Gene editing of normal HSPCs to confer immunotherapy resistance could be harnessed as an enrichment and selection strategy for cells simultaneously edited at another locus to treat genetic or infectious diseases. Such enrichment might overcome a current limitation in the field of HSPC gene therapy, namely the inability to achieve a stable and high proportion of gene-modified cells post-transplantation in patients. In vivo selection of gene-modified cells might also enable the use of conditioning with reduced toxicity such as nonmyeloablative8 and nongenotoxic regimens9,10. Importantly, this selection strategy will only be effective if the targeted antigen is expressed on HSPCs. Several studies2,11,12 including ours1,3 have demonstrated that myeloid markers including CD33 are present on long-term repopulating HSCs, rendering CD33 an ideal target for such strategy. Whether the level of CD33 expression in HSPC is sufficient for sensitivity to CD33-directed immunotherapies remains to be established.

Previous strategies to enrich gene-modified HSPCs include overexpression of mutated O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase (MGMT), conferring resistance to nitrosoureas and O6-benzylguanine drugs13,14. Stable HSPC enrichment could be achieved with this approach, but safety has remained a concern due to the need for alkylating agents for selection. Introduction of genes that confer resistance to a drug or small molecule15,16 has also been investigated for selecting gene-modified cells. However, these approaches, which have mainly been optimized in human cell lines may not be adequate for HSPC-based therapies given they might negatively affect the cells’ fitness and multilineage engraftment capacity. Additional investigation is thus needed for the development of in vivo selection strategies for HSPCs.

Base Editors (BEs) can precisely introduce single nucleotide changes through a DSB-independent mechanism to either rescue gene function or generate nonpathogenic gene variants17,18,19,20. Here we investigated its potential therapeutic applications to: 1) engineer a healthy donor allogeneic HSPC transplant product resistant to CD33-targeted therapies, and 2) develop a multiplex base editing strategy for selection of a therapeutic edit in the gamma globin genes (HBG) that increases fetal hemoglobin (HbF) expression by modulating the binding of key regulatory factors21,22,23, including the repressor protein BCL11A24.

We harnessed the inherent properties of BEs25,26,27,28 by specifically employing the adenine BE ABE8e25 to target CD33 in HSPCs alone and in combination with an edit in the HBG1/2 promoters. Using mouse xenograft and non human primate (NHP) transplantation models, we demonstrate that these cells maintain unaltered long-term engraftment and multi-lineage hematopoietic reconstitution with resistance of myeloid progeny to CD33-directed drugs in vitro and in vivo. Together, these results highlight the potential of BE for cancer immunotherapies and more generally for HSPC gene therapies.

Results

Base editing of CD33 exon 2 splicing acceptor site leads to exon 2 skipping

The dominant full-length isoform of CD33 (CD33FL) is composed of 7 exons. Most current anti-CD33 investigational treatments including GO are directed against epitopes localized in the V-set domain of CD33 encoded by exon 2. The single nucleotide polymorphism rs12459419, located within the exon splicing enhancer (ESE) site of exon 2, substitutes T for C (changing Alanine 14 to Valine, A14V), resulting in the increased transcription of a shorter isoform (CD33Δ2) lacking the exon 2 and reduced translation of CD33FL 29. Exome and genome sequencing databases revealed that 30% of individuals in all populations are homozygous TT for this SNP30,31. Splicing quantitative trait loci (sQTL) analysis of the genotype-tissue expression (GTEx) database indicated genotype dependent excision of exon 232,33. The investigation of the effect of this splicing polymorphism34,35,36,37 on pediatric AML patient response to GO treatment revealed that the CC genotype is associated with greater CD33 expression on AML blasts, as well as lower risk of relapse and higher survival.

To generate a cell population resistant to cancer immunotherapies targeting CD33 exon 2, we assessed whether cytosine base editors (CBEs) and ABEs26,38,39 could edit the CD33 ESE site and exon 2 acceptor splice site to reduce the expression of CD33FL. Owing to the properties of BEs26,38,39, we devised two strategies: either by replicating the known rs12459419 SNP using the CBE BE4max, or by mutating the exon 2 splicing acceptor site using ABE8e (Fig. 1a–c). Two single guide RNAs (sgRNAs) were tested with BE4max protein: sgCBE1 with an editing window targeting the ESE, and sgCBE2 which could concomitantly edit the splicing acceptor and the ESE of CD33 exon2 (Fig. 1c). Both sgRNAs led to more than 50% editing at the targeted nucleotides, but also produced indels as shown by Sanger sequencing and high throughput sequencing (HTS) (Fig. 1d, e) 6 to 7 days post electroporation. The BE4max edited cells displayed approximately 65% to 69% loss of CD33 expression when assessed by flow cytometry after staining with the P67.6 CD33 antibody, which recognizes an epitope encoded within exon 2 and is used as the targeting component for GO therapy (Fig. 1f). Interestingly, a ribonucleoprotein complex made of ABE8e protein and sgABE led to more than 95% editing at the targeted splicing acceptor adenine and almost no detectable indels. A bystander adenine (A5) localized within intron 1 was also edited (Fig. 1d, e). The efficient conversion of the exon 2 splicing acceptor adenine results in more than 94% of HSPCs that were not recognized by the anti-CD33 clone P67.6 (Fig. 1f). To assess the outcomes of the CBE and ABE editing strategies, we harvested the total RNA of unedited or edited HSPCs and performed RT-PCR with different sets of primers to detect CD33FL and/or CD33Δ2 cDNAs. As a control, we used CD34+ unedited cells that were homozygous for CC at Alanine 14 (A14) and expressed mostly CD33FL mRNA. Separation of the PCR products by gel electrophoresis (Fig. 1g) displays clear exon 2 skipped amplicons (highlighted with red and green stars) in all edited cells. Sanger sequencing confirmed the sequence of ABE-generated CD33Δ2 cDNA. We also noted the presence of CD33FL cDNA (highlighted with blue and black stars) in CBE edited HSPCs, which correlates with the detection of 30% CD33 expression by FACS. Finally, staining of ML-1 cells (a human myeloid leukemia cell line) with a set of CD33 antibodies40 either specific to the V set domain (P67.6), or to the C2 domain of all CD33 isoforms (9G2), or to the C2 domain only when exon 2 is absent (11D5), showed that CD33 expression at the membrane is lost following ABE8e editing (Fig. 1h). Due to its significantly higher indel outcomes and lower editing efficiency, the CBE editing strategy was not pursued further. Collectively, these observations highlight the feasibility and efficacy of inducing exon skipping in HSPCs by transient exposure to ABE8e/sgABE RNP mediated editing.

a Top Possible splicing outcomes at CD33 exon 1–3, ag: Splicing acceptor site (SA). gt: Splicing donor site. (Ab icon was created in BioRender. Du, X. (2025) https://BioRender.com/y35d204). Bottom Intron 1 (lower case)/exon2 (upper case) junction DNA sequence with highlight of exon 2 SA (red) and Exon Splicing Enhancer site (ESE in yellow). b CD33Δ2 lacks exon 2 due to the polymorphism rs12459419 that results in an altered ESE site. c Sequences of the protospacers designed to either edit the ESE with BE4max (sgCB1 and CB2) or the SA with ABE8e (sgABE). Protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) is in red. d Sanger sequencing profiles of edited CD34+ cells compared to the wild-type sequence (top) 7 days post electroporation. Edited nucleotides are indicated by arrows. e Editing efficiency (HTS analysis) at the targeted nucleotides and bystanders, as well as indels. f FACS analysis of the edited CD34+ cells 7 days post electroporation with antibody clone P67.6 which recognizes an epitope located in exon 2. g PCR on cDNA with sets of primers, specific to CD33Δ2 (spanning exon junction 1–3), or common to all isoforms (in exons 1, 5 and 7), (L: Ladder in bp). Sanger sequencing of PCR products confirm the absence of exon 2 in edited cells while all other exons are intact. 1 independent experiment. h ML-1 cells were mock electroporated (ML-1mock), or electroporated with ABE8e and CD33 monoclonal antibody (mAb) staining compared to parental ML-1 cells or ML-1 cells in which both alleles of CD33 had been disrupted via CRISPR targeting of exon 1 (ML-1CD33KO). P67 mAb (i), 9G2 (ii) binds to the C2-set domain of CD33, whether V-set is present or not, and 11D5 (iii and iv) binds to the C2-set domain of CD33 when the V-set is absent, e.g., CD33 lacking exon 2. Specificity of 11D5 to CD33Δ2 is shown (iv.) using mouse 3T3 cells that lack human CD33 expression are shown (m3T3) with forced expression of either CD33Δ2 (m3T3+CD33Δ2) or full length CD33 (m3T3+CD33FL). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

CD33 Δ2 cells display intact phagocytic function and resistance to CD33 targeted therapy in vitro

To assess the functional capacity of CD33Δ2 ABE8e edited hematopoietic cells, we evaluated their phagocytotic ability by incubating in vitro myeloid differentiated unedited or CD33Δ2 -edited CD34+ cells with E. coli bioparticles (Fig. 2a). The quantification of internalization of E. coli bioparticles by flow cytometry showed a similar level of phagocytosis between edited and unedited cells. Furthermore, the inhibition of actin polymerization with cytochalasin D blocked the phagocytic capacity of unedited and CD33Δ2 -edited myeloid cells similarly.

a In vitro differentiated unedited (UE) or CD33Δ2-edited monocytes show comparable phagocytosis capacity, as measured by E.coli bioparticles internalization. Left, Representative FACs plots of E. coli bioparticles internalization. Treatment with actin polymerization inhibitor, cytochalasin D, abrogates phagocytosis. Right, Graph of phagocytosis quantification. Unpaired two-tailed t-test. b CD33Δ2-edited CD34+ cells resist Gemtuzumab Ozogamicin (GO) cytotoxicity in vitro. Cells were incubated 48 h with GO and cytotoxicity analyzed by FACS using Sytox Blue or 7AAD as a viability dye. CD33 Δ2-edited CD34+ show same resistance to GO cytotoxicity than a donor with homozygous rs12459419 A14V SNP (TT genotype). Error bars show ±SEM. (2 independent experiments, 2 donors, run in triplicates) c, ML1 CD33 WT or KO cells and Unedited, or ABE8e-edited mPB CD34+ cells were assessed for resistance to the CD33/CD3 bispecific T-cell engager (BiAb, generated from published sequences and described in Correnti et al61.). Target cells were incubated with healthy donor T cells for 2 days and absolute cell number and viability were detected by flow cytometry analysis following staining with 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Results were normalized to reactions that were not treated with the drug (1 experiment run in triplicates, 1 donor). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Additionally, we subjected ABE8e-edited CD34+CD33Δ2 cells to GO to evaluate whether editing confers resistance to CD33-targeted therapy. While CD34+ Unedited cells (CC genotype at Alanine 14) predominantly expressing CD33FL display high sensitivity to GO, CD33Δ2-edited CD34+ cells show GO resistance, similar to control donor cells homozygous for TT genotype (Valine at position 14, V14) and to CD33 knockout CD34+ cells (CD34+CD33Del). MOLM14 leukemic cells, homozygous for CC genotype (A14) and expressing CD33 at high level, were also used as controls, showing high sensitivity to GO (Fig. 2b and Fig. S1). Furthermore, CD34+ cells edited with ABE8e were almost completely resistant to the cytotoxic activity of a CD33/CD3 bispecific T cell engager that is dependent on an exon 2 encoded epitope (Fig. 2c), thus corroborating results from GO treatment. Taken together, these results confirm that CD34+CD33Δ2 base edited cells retain intact phagocytosis capacity yet are insensitive to CD33 targeted therapies in vitro.

CD33 edited HSPCs engraft and repopulate a complete hematopoietic system

Next, we examined if adenine base editing of CD34+ cells could perturb hematopoiesis by following the engraftment and hematopoietic repopulation of CD34+ Unedited and CD34+CD33Δ2 cells in mice over time (Fig. 3a). In all analyzed tissues (peripheral blood, bone marrow (BM), staining of the engrafted cells with the P67.6 antibody clone barely detected CD33 expression in mice reconstituted with CD33Δ2-edited CD34+cells compared to CD34+ Unedited controls (Fig. 3b, c) at 16 weeks post-transplantation. Flow cytometry analysis of mice transplanted with control CD34+Unedited or CD33Δ2-edited CD34+ cells revealed no differences in the levels of overall human cell engraftment (hCD45+) or of specific donor-derived hematopoietic lineages (Fig. 3b, c, Fig. S2). HTS analysis of ABE8e-edited human donor cells pre-and post-transplantation showed that editing efficiency is maintained in vivo (Fig. 3d). Furthermore, similar BM architecture was observed in both groups engrafted with unedited or CD33Δ2 -edited cells as illustrated by H&E staining (Fig. S3).

a Schematic of the experiment was created in BioRender. Du, X. (2025) https://BioRender.com/y35d204. b, c Measure of engraftment by percentage of human CD45+ cells and of hematopoietic repopulation by frequency of progenitors myeloid (CD123) and lymphoid (CD10), as well as mature myeloid (CD14) and lymphoid (CD19), and T cells (CD3) within the human CD45 population in peripheral blood at 8 weeks post-transplantation and in the BM at 16 weeks post-transplantation. (Unedited: n = 5, Edited: n = 9, 2 independent experiments, 2 donors, unpaired two-tailed t-test). d On-target editing (HTS analysis) in edited cells kept in vitro (pre-Transplant) or harvested in the BM 16 weeks post-Transplantation. (2 independent experiments, 2 donors, one-way ANOVA, Tukey’s multiple comparisons test) e Left, frequency of CD14+ myeloid cells in BM of 12 weeks post-transplanted mice. Right, frequency of CD14+CD33− cells in the BM of 12 weeks post-transplanted mice before and one week after Gemtuzumab Ozogamicin (GO) treatment (0.5 ug per mouse). UE, unedited cells. (n = 6, 2 independent experiments, 2 donors, one-way ANOVA, Tukey’s multiple comparisons test). All error bars in this figure show ±SEM. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To determine whether ABE8e-editing of CD33 exon 2 splice site rendered engrafted CD33Δ2 -edited cells resistant to targeted immunotherapy in vivo, CD34+ Unedited and CD33Δ2-edited CD34+ transplanted mice were injected with GO (Fig. 3a). In both groups, the frequencies of myeloid CD14+ cells at 12 weeks post-transplantation were comparable prior to GO treatment (Fig. 3e, left panel). However, following GO treatment, the CD33−CD14+ population was present only in CD33Δ2 -edited CD34+injected mice (Fig. 3e, right panel). Remarkably, while a single dose of GO resulted in eradication of the CD33+ population, the CD33−CD14+ population remained detectable at a significant frequency in mice transplanted with edited cells (Fig. 3e, Fig. S4).

Together, these data indicate that ABE-mediated CD33 exon 2 skipping does not impair BM reconstitution or hematopoietic differentiation of CD34+ HSPCs and confers myeloid resistance to CD33 directed therapy.

CD33/HBG multiplex ABE8e treatment results in a high frequency of dual-edited human cells that are enriched after GO treatment

Having demonstrated that CD33-ABE8e edited cells are protected from CD33 drug cytotoxicity, we sought to determine whether a similar strategy could be exploited to enrich for another edit that is relevant for genetic diseases such as hemoglobinopathies, when the CD33 edit and the therapeutic edit are installed simultaneously in cells. As a model system, we focused on editing the regulatory region of gamma hemoglobin (HBG) genes, which has previously been targeted by site-directed nucleases21,23,41,42 or by BE43,44 to reactivate the expression of fetal hemoglobin (HbF) as treatment for beta-hemoglobinopathies. To be successful, this approach would also require that CD33 is expressed at sufficiently high levels in primitive multilineage HSPCs to allow selection for both edits in these cells, and subsequent differentiation into HbF expressing erythrocytes. We specifically chose to target the HBG promoters at position −175 relative to the initiation codon, where a natural T-to-C variant maintains high HbF expression in adults by creating a de novo binding site for the transcriptional activator TAL1, ultimately increasing HBG expression45,46,47. BE targets for this HBG-175 site have previously been validated for HbF reactivation, and a positive correlation was established between HBG edits and levels of HbF expression given that a total of four HBG site can be edited per cell (two HBG genes and two alleles)44,48,49. For optimal targeting of this HBG site, we use the ABE8e-NG variant in which the Cas9 domain was engineered to have a less stringent PAM requirement as compared to the parental version50,51. Extensive on- and off-target analysis of the HBG-175 target sequence was recently conducted in human CD34+ cells treated with ABE8e-NG, showing efficient editing with potent HbF reactivation of adenine A5. Targeting of this HBG-175 site also produced concomitant bystander edits at A11 and A3 that also affected HbF expression49.

We delivered ABE8e mRNA along with the targeting HBG-175 sgRNA by electroporation to human CD34+ cells and found the expected A > G conversion at 3 different adenines within the target site, with efficiencies averaging 8% at A3, 40% at A5 and 18% at A11 (Fig. 4a–c). Similar to what we described for CD33 ABE8e editing, no indels or other types of changes were detected at this site (Fig. 4b). When used in the context of multiplex editing, electroporation of ABE8e mRNA along with both HBG and CD33 targeting sgRNAs resulted in a small drop in efficiency that did not reach statistical significance for all 3 adenines within the HBG target sequence (Fig. 4c). CD33 editing efficiency remained high in the context of multiplex editing, averaging 75% at A5 and 80% at A7 (Fig. 4d). Hematopoietic colony assays run from multiplex edited CD34+ cells revealed no difference in the number or type of colonies recovered relative to mock electroporated cells (Fig. 4e).

a Schematic of HBG −175 ABE8e target site. Adenines in the editing window are marked in bold red and PAM in light red. b HBG ABE8e editing efficiency measured in human mPB CD34+ HSPCs after treatment by mock electroporation (unedited, UE) or by HBG ABE8e mRNA. Results are from one representative donor. c HBG editing efficiency in human mPB CD34+ HSPCs treated by mock electroporation (UE), by HBG ABE8e mRNA (single) or by CD33/HBG ABE8e mRNA (multiplex). Results are from 4 different donors, 4 independent experiments. d CD33 editing efficiency in human mPB CD34+ HSPCs treated by mock EP (UE) or by CD33/HBG ABE8e mRNA (multiplex). Results are from 5 different donors, 5 independent experiments. e Colony-forming potential of mPB CD34+ cells treated by multiplex ABE8e editing. Results are from 1 representative donor, 3 technical replicates. M=macrophages, G=granulocytes, GM=granulocyte/macrophage, GEMM=granulocyte/erythrocyte/macrophage/monocyte BFU-E=erythroid. f Frequency of colony-forming cells displaying unedited (UE), edits at each gene target, or edits at both gene targets in the same colony. Results are from 2 different human donors, 2 independent experiments. g Frequency of colony-forming cells with unedited (UE), monoallelic (mono) or biallelic (bi) CD33 edits, and accompanying edits (0 to 4) at the HBG target site in two different donors. Number of colonies analyzed is shown on top. N/A=Not Applicable. h Unedited (UE) or multiplex edited ML1 cells treated for 6 consecutive days with 10 pg/mL Gemtuzumab Ozogamicin (GO) starting at 5 days post-electroporation. Viable count was determined by trypan blue staining. Results are from 1 representative experiment. i, Editing efficiency measured at the CD33 (left) or HBG (right) gene targets in multiplex edited ML1 cells from h treated or not with GO at 8 days post GO removal (14 days post-electroporation). All error bars in this figure show ±SEM. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Enrichment for therapeutically relevant HBG-edited cells using CD33-directed drugs would be feasible if both CD33 and HBG edits are found in the same cell. To address this question, we measured clonal editing outcomes in colonies derived from multiplex ABE8e edited CD34+ cells. Over 75% of colonies displayed edits at both HBG A5 and CD33 A7 (Fig. 4f). Of these multiplex edited colonies, the majority showed biallelic CD33 A7 editing (100% and 78% in two different donors), which are expected to fully resist CD33 drug toxicity. Among these, 88.5% and 42.9%, respectively in the two donors, display edits at two or more HBG A5 targets (Fig. 4g and Fig. S5). Taken together, these results indicate that multiplex ABE8e editing of mobilized peripheral blood (mPB) CD34+ HSPCs yields a large fraction of cells containing desired edits at both HBG A5 and CD33 A7 targets, without compromising their multilineage differentiation capacity.

To assess resistance and subsequent enrichment of multiplex ABE8e-edited cells to GO, we used the ML1 human leukemic cell line that exhibits robust CD33 surface expression and is highly sensitive to GO3. We first compared viable cell counts in mock electroporated cells (unedited, UE) with multiplex-edited ML1 cells and found that edited cells were mostly resistant to GO cytotoxicity, as evidenced by their quick proliferation after drug removal (Fig. 4h). Comparison of editing frequencies in GO-treated vs untreated cells showed an increase of over 2-fold at the CD33 target site, with additionally a 2-fold increase at the HBG A5 target (Fig. 4i). Together, these results confirm that CD33-directed drugs have the potential to enrich cells bearing both the CD33 and the HBG therapeutic edits.

Off-target editing analysis of single and multiplex-edited cells

To characterize off-target editing resulting from base editor treatment targeted to CD33, we first conducted CIRCLE-seq52 to experimentally nominate off-target sites. CIRCLE-seq nominated a list of 754 potential off-target sites for sgABE and 548 sites for sgCBE1. We ranked these sites based on their CIRCLE-seq read counts and chose the top 20 nominated sites from each list for further characterization, which included the targeted site in CD33 and 19 potential off-target loci each (Fig. S6 and Fig. S8). We used Illumina high-throughput sequencing (HTS) to quantify on- and off-target editing in edited CD34+ HSPCs compared to unedited controls 7 days following editor electroporation and maintenance in cell culture (Fig. S7). Additionally, to assess editing in engrafting hematopoietic stem cells, we conducted HTS at each site in engrafted cells harvested at 16 weeks post transplantation in mice. Statistically significant off-target editing was observed at 6 loci using ABE8e and 3 loci using BE4max (Fig. S7). Off-target editing in human cells engrafted in mice was much more variable than editing in cells remaining in culture, with engrafted populations in some mice experiencing 90% editing. However, the cell lineages and the total human engraftment in these mice were not different than unedited controls (Fig. 3b, c), so the increase in observed editing efficiency was not caused by oncogenic clonal expansion and may instead be due to the bottleneck of a small number of edited cells that engrafted durably in mice. Indels resulting from ABE treatment were minimal at all sites including those that were efficiently base edited Fig. S7).

To assess editing in multiplex edited cells at both CD33 and HBG-175, we conducted CIRCLE-seq again for the CD33 target using the SpCas9-NG variant that has expanded PAM capacity and was required for the fetal hemoglobin target, which nominated a total of 3668 potential off-target sites. We had previously conducted CIRCLE-seq and off-target editing analysis with this same Cas9 variant targeted to HBG-175 and identified 4 sites where off-target editing occurred49. We used HTS to quantify editing in cells that were edited with ABE8e-SpCas9-NG and either the CD33 sgRNA, the HBG-175 sgRNA, or both, alongside unedited control cells. We sequenced the top 20 sites nominated by CIRCLE-seq with the highest read counts for CD33, the 6 sites where we already observed CD33 off-target editing using ABE8e with wild type Cas9, and the 4 off-target sites previously characterized for HBG-17549 (Fig. 5a, b). Two new candidate sites for CD33 could not be amplified. We observed statistically significant editing at 16 sites for CD33 and 3 sites for HBG-175 (Fig. S9 and S10). Editing with a single guide or both guides simultaneously did not impact whether off-target editing occurred at any site (Fig. 5c). The large majority of sites where off target editing occurred fell in intergenic or intronic regions of the genome. Some fell in intron/exon boundaries and may disrupt splicing of the edited gene, and two fell in exons, which both led to nonsynonymous amino acid substitutions (Fig. 5d). Future work will focus on minimizing off-target edits using these characterizations as a benchmark by adjusting the dose and using higher-fidelity and/or lower-activity variants of base editors. In addition to reducing these guide-dependent off-target observations, other ABE variants and architectures such as inlaid ABE8.2053 may also reduce guide-independent off-target editing that has been observed with ABE8e51. For the present study, we moved forward with in vivo experiments using this high dose and very efficient editor reasoning that it would provide the most sensitive measurement in our animal models of any potential issues that might arise in a human therapeutic, such as clonal expansion or excessive cytotoxicity.

a Visualization of on-target (CD33) and top 23 off-target sites associated with ABE8e editing of the CD33 exon 2 splice acceptor site in multiplex-edited (CD33 + HBG) and single-edited (CD33 or HBG) CD34+ HPSCs. These off-target (OT) sites include eighteen loci (OT1-OT18) nominated by CIRCLE-seq using ABE8e-SpCas9-NG for the CD33 target as well as five loci that showed statistically significant editing from prior off-target analyses in engrafted cells, which had been nominated by CIRCLE-seq using ABE8e (wild type Cas9) (OT19-OT23). Alignment of each site to the sgABE protospacer is shown. b Table summarizing the top 23 nominated off-target loci. Loci with an asterisk (*) indicate that statistically significant editing was observed at this site at one or more nucleotides (A5, A7, or both). Quantification of editing at each site is shown in Fig.S9 and S10. c Histogram demonstrating the mean percent of reads with A > G editing at any site within the sgABE protospacer window for validated off-target sites, classified by multiplex (CD33 + HBG) or single-edited (CD33 or HBG) status. Among the top off-target sites analyzed, no substantial difference in off-target editing was detected among multiplex vs. single-edited CD34+ HPSCs. d Pie chart indicating genomic context of top nominated off-target sites that showed statistically significant editing. The majority of off-target sites were located in intergenic or intronic regions. Results shown are from 3 human donors, 3 independent experiments. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Multiplex ABE8e-edited human CD34+ cells show normal hematopoietic reconstitution and GO resistance in vivo

We and others previously demonstrated that CRISPR/Cas9-editing of the CD33 or HBG gene targets in CD34+ HSPCs does not compromise multilineage engraftment1,2,3,41. We confirmed normal engraftment of multiplex ABE8e-edited human CD34+ cells (treated by ABE8e mRNA electroporation with each targeting sgRNA) and reconstitution of multilineage hematopoiesis in adult (Fig. 6) and neonate (Fig. S11) NSG mice. In both models, human CD34+ cell engraftment was comparable between the control group and the multiplex edited group with circulating human cells averaging 20% in the adult model (Fig. 6b) and 70% in the neonate model (Fig. S11b). As expected, CD33 expression in blood CD14+ monocytes was decreased to less than 10% in the edited group as compared to nearly 100% in the control group (Fig. 6a, Fig. S11c). Human lineage reconstitution was comparable between both groups in blood and BM at 16 weeks post-transplantation (Fig. 6a-d and Fig. S11d). In the adult model, assessment of BM of the edited group revealed that CD33 was also almost completely absent from progenitors (Fig. 6d), and also from the CD34+ subset (Fig. 6e). Importantly, HSC engraftment in BM, as defined by CD34+CD38low, was not affected by our editing approach (Fig. 6c, d). Together, these results demonstrate that our ABE8e-multiplex editing strategy does not affect CD34 + HSC multilineage engraftment in the mouse xenograft model.

a Measure of engraftment by percentage of human CD45+ cells in different tissues at 14 to 16 weeks post-transplantation. Results are from 2 different human donors, 2 independent experiments, n = 11 for PB and n = 6 for BM/spleen for the unedited (UE) group; n = 12 for PB and n = 4 for BM/spleen for multiplex editing. b Hematopoietic repopulation by frequency of mature myeloid (CD14), lymphoid (CD19), and T cells (CD3) within the human CD45 population in peripheral blood. CD33 expression within the CD14+ subset is also shown. Results are from 2 different human donors, 2 independent experiments, n = 11 for UE and n = 12 animals for multiplex editing. c Representative flow plots showing gating strategy of human HSC (CD34+CD38low) in BM of multiplex edited mouse at necropsy. d Engraftment of multiplex edited vs. unedited mPB CD34+ cells in BM as measured by human CD45 expression and of hematopoietic repopulation by frequency of mature myeloid (CD14) and B and T lymphoid (CD19 and CD3) within the human CD45 population in peripheral blood at 14 to 16 weeks post-transplantation. CD33 expression in total BM cells and HSC content (CD34+CD38low) is also shown. Results are from 2 different human donors, 2 independent experiments, n = 6 for unedited and n = 4 animals for multiplex editing. e Representative flow plots of CD33 expression in BM HSC (CD34+CD38low) from engrafted mice at necropsy. All statistical analyses in this figure were done with an unpaired two-tailed t-test. All error bars in this figure show ±SEM. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

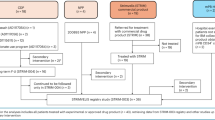

To assess resistance of multiplex edited HSPCs to GO in vivo, we engrafted a new cohort of NSG mice with unedited and multiplex ABE8e-edited HSPCs (Fig. 7a). At 14 weeks post transplantation, these mice showed comparable BM engraftment between the unedited and edited groups (Fig. 7b), and decreased CD33 expression was confirmed in the edited group by flow cytometry (Fig. 7c). Edits at both targets were detected in BM cells, which averaged 75% at CD33 A7 and 12% at HBG A5 (Fig. 7d). Following three consecutive rounds of GO treatment on weeks 15, 16 and 17, a sharp and statistically significant decline in BM CD14+ monocytes was observed in unedited mice, whereas edited mice showed a small, non-statistically significant decrease in monocytes, suggesting resistance to GO treatment (Fig. 7e). We also evaluated the frequency of CD34+CD38low BM HSPCs before and after GO treatment in the unedited and edited animals, and found no effect of the drug in either group (Fig. 7f). In conclusion, these results confirm resistance of multiplex edited cells to GO treatment in vivo. This effect was demonstrated in monocytes that express high levels of surface CD33 receptors but could not be assessed in CD34+CD38low HSPCs, which are not sensitive to GO, presumably due to lower level of CD33 expression.

a Schematic and timeline of mouse engraftment experiment with three consecutive administrations of Mylotarg (0.05 mg/kg). The mouse cartoon was created in BioRender. Du, X. (2025) https://BioRender.com/g56e371. b Human cell engraftment in BM of mice engrafted with unedited (UE) or multiplex ABE8e edited CD34+ cells at 14 weeks post-transplant. c, Frequency of human CD45+/CD33+ cells measured from the same animal as b. Statistical analysis shows unpaired two tailed t-test. d Editing efficiency measured at CD33 (left) and HBG (right) targets measured in mouse BM engrafted with multiplex edited cells at 14 weeks post-transplant. e Frequency of human monocytes (% HuCD45+CD14+) in BM of mice engrafted with UE or multiplex ABE8e edited CD34+ cells pre- (wk14) and post-Mylotarg (wk18) treatment. f Frequency of human HSCs (% HuCD45+CD34+CD38low) in BM of engrafted mice pre- and post-Mylotarg treatment. 1 experiment, 1 human donor, n = 3 for the unedited group and n = 5 for the multiplex edited group. All statistical analyses were done with one-way ANOVA, Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. All error bars in this figure show ±SEM. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Long-term persistence of multiplex ABE8e-edited CD34+CD90+ cells in NHPs

To evaluate the long-term safety and engraftment of multiplex ABE8e-edited HSPCs, we turned to the autologous NHP transplantation model, which enables the investigation of multilineage engraftment, including myeloid differentiation, following myeloablative conditioning. Furthermore, this model enables the tracking of hemoglobin production in peripheral blood, which is not possible in xenograft mouse models where human erythroid cells do not fully mature54. We first verified that HSPC subsets, particularly the recently described hematopoeitic stem cell (HSC)-enriched CD34+CD90+CD45RA− population55,56, could be efficiently edited with ABE8e in NHP. Bulk CD34+ cells were edited with CD33 ABE8e-NG either using mRNA or RNP, and subsequently sorted for HSCs (CD90+CD45RA−), multipotent progenitor cells (CD90−CD45RA−), and lympho-myeloid progenitors (CD45RA+) (Fig. S12). CD33 editing was highest with mRNA delivery and was comparable for each sorted subpopulation, including for the HSC-enriched CD90+CD45RA− subset, for both mRNA and RNP as delivery payload.

Having confirmed that the NHP HSC-enriched cell subset can efficiently be edited with ABE8e, we transplanted two rhesus macaques with multiplex edited cells. For both transplants, CD90+CD45RA− cells were first FACS sorted from enriched BM CD34+ cells (Fig. S12), which greatly minimized the number of cells to be manipulated. Consistent with our previous results employing CRISPR/Cas9 RNP-editing41 and despite upfront FACS-sorting, ABE8e-editing of a sorted CD90+ population did not affect CFC potential (Fig. S13). Editing efficiency in this cell population averaged 70 to 80% for the targeted A7 within CD33, and 8 to 45% for the three adenines at the HBG target site (Fig. 8a, b). Similar to human CD34+ cells (Fig. 6f), ~70% of colonies derived from these cells contained edits at both target genes (Fig. 8c). Most colonies showed biallelic CD33 A7 editing in both animals, required for selection, and among these about half displayed edits at two or more HBG A5 sites (Fig. 8d).

ABE8e editing efficiency at the CD33 (a) and HBG (b) targets measured in the infusion product of each transplanted animal at 5 days post multiplex editing or post mock electroporation (unedited, UE). c, Frequency of unedited, edits at each gene target, or at both targets in colony-forming cells (CFCs) obtained from infusion products from a and b. n = 71 for A18031 and n = 37 for A18038. d Frequency of colony-forming cells with unedited (UE), monoallelic (mono) or biallelic (bi) CD33 edits, and accompanying edits (0 to 4) at the HBG target site in the two infusion products. Number of colonies analyzed is shown on top. e Tracking of CD33 and HBG editing in peripheral blood of both transplanted animals. For simplicity, only editing efficiency at the relevant adenines are shown (A7 for CD33 and A5 for HBG). f CD33 expression in CD11b+CD14− peripheral blood granulocytes in both transplanted animals as compared to an untransplanted control animal (A16227). g, Fetal hemoglobin (HbF) expression as measured by flow cytometry staining for F-cells in peripheral blood of both transplanted animals as compared to the untransplanted control. h Colony forming cells (CFCs) derived from BM aspirates taken from both transplanted animals at 8- or 6-months post-transplant for A18031 and A18038, respectively. i, Frequency of unedited, edits at each gene target, or at both targets in CFCs from g n = 57 for A18031 and n = 45 for A18038. All error bars in this figure show ±SEM. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

For animal A18031, the infused product consisted of total of 3.8 × 106 edited CD90+CD45RA− cells (454,000 cells per kg) combined with 10.6 × 106 non-edited CD90− cells (1.3 × 106 cells per kg), which do not contribute to long-term hematopoietic reconstitution55. For animal A18038, 7.56 × 106 edited CD90+CD45RA− cells (960,000 cells per kg) combined with 31 × 106 non-edited CD90− cells (3.9 × 106 cells per kg). Both animals were conditioned by total body irradiation (TBI) and recovered without complications after transplantation. Blood counts including neutrophils, lymphocytes, platelets, and monocytes rapidly stabilized and remained within a normal range during posttransplant monitoring (Fig. S14). Hematopoietic recovery was also monitored by flow cytometry, which showed kinetics of multilineage reconstitution that are characteristic of a typical transplant experiment in this model41,55(Fig. S15). ABE8e editing at the CD33 and HBG gene targets in blood-nucleated cells stabilized after about 2 months post transplantation. At the last time point analyzed (18 months for A18031 and 7 months for A18038), CD33 editing at the relevant adenine (A7) reached 14% and 23%, respectively in each animal, while HBG editing at A5 was 5% and 12%, respectively (Fig. 8e). Resulting CD33 expression assessed by flow cytometry in blood granulocytes from each animal was lower post transplantation as compared to pre-transplant levels, or as compared to an un-transplanted animal control (Fig. 8f). In addition, the kinetics of CD33 expression post-transplant closely reflected the frequency of CD33 editing detected in blood nucleated cells in both animals. A similar correlation between HBG editing and frequency of blood F-cells was also noted, with levels that stabilized after the initial transient induction resulting from the transplantation procedure57 (Fig. 8g). At 6 months post-transplantation, 7% HBG editing resulted in 8% F-cells in animal A18031, and 16% HBG editing resulted in 16% F-cells in A18038 (Fig. 8e, g).

To verify that multiplex ABE8e-edited HSPCs result in normal BM reconstitution after transplantation, BM samples were taken at 8- and 6-months post-transplantation in A18031 and A18038, respectively. Reconstitution of the stem cell compartment was assessed both by flow cytometry analysis and by functional readout using colony-forming assays. Immunophenotypic evaluation of BM samples demonstrated normal distribution of defined HSPC subsets that were not affected by our editing or transplant strategy (Fig. S16, S17). CFC assays demonstrated robust erythro-myeloid differentiation potential (Fig. 8h), similar to freshly isolated and nonmodified BM cells41. Single colonies derived from the CD90+ subset were also evaluated for editing at both CD33 and HBG as was done previously for the infusion product (Fig. 8c). About 20% of the colonies showed editing at least one target gene, and importantly, 11% and 13% of the colonies showed editing at both targets in each animal, respectively (Fig. 8i). While these frequencies are lower than those detected in the infusion product, they confirm that multiplex ABE8e-edited HSPCs persist long term and restore multilineage hematopoiesis. Given that GO does not cross-react with rhesus CD33, we were unable to assess resistance and subsequent enrichment of multiplex edited cells to CD33 drugs in this model. In summary, these results confirm that, in the autologous setting, CD90+-enriched HSCs treated by ABE8e-multiplex editing are not compromised for long-term engraftment and differentiation.

Discussion

Here we use the adenine base editor ABE8e to disrupt the CD33 exon 2 splice acceptor as a strategy to protect healthy cells from established CD33 immunotherapies targeting an epitope located in that exon. Base editors edit DNA without introducing substantial DSBs, so chromosomal translocations and toxicities associated with multiple DSBs are minimized, making ABE a particularly well-suited platform for multiplex genome editing. The safety of this approach was demonstrated by normal hematopoietic engraftment and function of edited cells. Our findings also showed resistance of CD33 ABE8e-edited HSPCs to GO both in vitro and in vivo, thus validating the concept of edited HSPCs as transplantation product that would be resistant to targeted therapies, using CD33 as a paradigm. To expand the applicability of this approach to other genetic diseases, particularly hemoglobinopathies, we next evaluated a multiplex CD33/HBG ABE8e editing strategy to determine if both edits could simultaneously be enriched following treatment with CD33-directed drugs. We focused on the HBG-175 sequence because it is a validated therapeutic target for HbF reactivation, and extensive on- and off- target editing data for this site have been generated49. Multiplex CD33/HBG ABE8e edited HSPCs maintained normal and persisting multilineage engraftment in mouse and NHP models. To the best of our knowledge, these results represent the first investigation of engraftment of multiplex base edited HSPCs in a large animal model. In this model, we documented loss of CD33FL surface expression in differentiated myeloid cells and elevated peripheral blood HbF production in two transplanted rhesus macaques for over a year. The lower level of persisting editing levels seen in blood at the HBG and CD33 targets as compared to those seen in the infusion product may be explained by residual/non-edited HSPCs after conditioning, which may have competed with infused/edited cells for hematopoietic reconstitution. An alternative hypothesis is a lower editing efficiency in the long-term HSCs, which likely represent a fraction of the edited CD34+/CD90+ subpopulation. Since these cells are generally considered quiescent, base editor mRNA may not be the ideal delivery material to these cells as it requires active translation for activity. The lower levels of long-term editing efficiency observed in these two animals as compared to a previous animal cohort transplanted with the same cell subpopulation edited with CRISPR/Cas9 ribonucleoprotein41 tends to support this hypothesis. Given the lack of cross-reactive drugs with macaque CD33, we were unable to assess the proposed CD33 based enrichment strategy in the transplanted animals. Instead, we relied on a human leukemic cell line to demonstrate in vitro that both CD33 and HBG edits could be increased by about 2-fold following treatment of multiplex edited cells with GO. Recent work described a similar approach for simultaneous editing of CD33 and a different HBG site by delivery of ABE8e using helper-dependent adenovirus to human CD34+ cells ex vivo and in vivo in humanized mice58. Overall editing efficiency was lower than that observed in our study and was not measured in single cells, making it impossible to estimate the percentage of dual edited cells. Nevertheless, enrichment for both edits could be achieved in vitro and in vivo along with an increase in HbF expression in the erythroid progeny, using a substantially greater GO dose.

The CD33 editing approach described in this report induces exon 2 skipping with few to no indels detected. By mimicking a natural SNP with no associated detrimental consequences, we generated HSPCs expressing a CD33 variant lacking the exon containing the epitope recognized by the targeted therapy with no associated detrimental outcomes. CD33Δ2-edited cells exhibit normal function and differentiation but are insensitive to treatment with a CD33 antibody drug conjugate. Using a C-base editor to replicate the natural C > T SNP led to substantially increased indel outcomes (~13%) and lower editing efficiency at the targeted nucleotides relative to an A-base editor that introduced a new mutation to destroy the same splice site. We expect that the high frequency of indels is caused by simultaneous deamination of 2 or more of the 4 C nucleotides in the editing window, recruiting uracil N-glycosylase that excises these modified nucleotides and results in double stranded DNA breaks together with the Cas9-induced nick59. Conversely, A-base editing achieved nearly 95% conversion of the targeted nucleotide within the splice acceptor site in HSPCs with no detectable indels. We propose to leverage the potential of allogeneic therapy for myeloid disorder by combining gene edited allo-HSCT with ADC and/or CAR immune cells.

We assessed off-target editing resulting from ABE8e treatment in HSPCs maintained in culture and in cells that engrafted in mice. Although substantial off-target editing was observed at many sites, there was no alteration of hematopoietic multipotency or myeloid function, which is promising for the clinical viability of this approach. Off-target editing did not change between cells treated with just one editor compared to those treated with both CD33 and HBG-targeting guides. Nevertheless, off-target editing should be minimized and future work should focus on using less active or higher-fidelity versions of base editors, evaluating improvements based on reduced off-target editing at the sites identified here. Because the CD33 edit could permit enrichment of edited cells, the high editing efficiencies achieved by our method are not necessary in the clinic and decreasing the editor dose could also improve editor specificity.

Our group and others have shown that transplantation of CRISPR/Cas9 HBG-edited HSPCs stably increases HbF production while maintaining normal long-term hematopoietic reconstitution in vivo, including in the NHP autologous model41. An analogous CRISPR/Cas9 approach aimed at HbF reactivation, albeit with a different gene target, is now a clinically approved treatment for sickle cell anemia60 and beta-thalassemia61. Despite offering great promises, these approaches are limited by the use of myeloablative conditioning with busulfan for stable engraftment of gene-edited HSPCs. This use of high-intensity conditioning poses considerable risks such as infertility, organ toxicities and late-toxic effects, secondary malignancies, and prolonged myelosuppression with neutropenia. These limitations to HSC genome-editing based therapy could be alleviated using lower-intensity or antibody-based conditioning regimens. Given that these forms of conditioning may not be as efficient at removing non-edited endogenous cells, they are likely to result in lower levels of gene-modified cells. This is especially the case in diseases such as hemoglobinopathies where edited HSPCs do not have a natural survival advantage, and thus require an in vivo selection strategy to reach therapeutic levels of editing post-transplantation. Given the resistance of CD33-edited cells to validated immunotherapies, our results showed in vitro that the secondary HBG edit is increased 2-fold. Further work is needed to demonstrate the feasibility of this approach in vivo, and whether selection will occur at the stem cell level or in differentiated myeloid cells expressing greater levels of CD33. The NHP model is ideally suited to evaluate selection strategy given the long-term persistence of modified cells but drugs that are cross-reactive with macaque CD33 are yet to be developed. Epitope editing on other receptors expressed in HSPCs such as CD45, CD123 (IL-3RA), CD117 (KIT) and CD135 (FLT3) has been previously investigated for the purpose of avoiding on-target/off-tumor toxicity by targeted immunotherapies to shield the receptor while preserving physiological expression and function62,63,64. In comparison, the selection approach we propose here combines a CD33 edit for exon 2 skipping with the HBG edit to enrich therapeutic and dual gene edited cells in vivo. Additional work will be needed to determine if selection can efficiently be achieved at the level of HSPCs, for example by using more potent CD33-directed drugs.

In summary, we propose an efficient editing strategy to create an HSPC population that is both therapeutically altered and resistant to targeted CD33 therapy. Inspired by natural polymorphisms leading to exon skipping in CD33, we generated base editors that can lead to skipping of exon 2, targeted by anti-CD33 drugs. We propose that using genome editors to disrupt exons or otherwise modify residues involved in drug binding can be used to generate healthy cell populations resistant to many other cancer therapeutics. Adapting these methods to generate other resistance mutations, with or without multiplexed therapeutic edits, could improve targeted cancer therapies and treatments for genetic blood disorders.

Methods

Ethical statement

The research presented in this manuscript complies with all relevant ethical regulations. Mice experiments were either conducted at the Columbia University animal facility or at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center under specific pathogen-free in compliance with the approved Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) protocols #AAAW7458 and #50980, respectively, following the ARRIVE guidelines when applicable. At both institutions, all animals were housed under a 12:12 h light/dark cycle with free access to food and water. All mice were fed with Labdiet’s PicoLab Rodent Diet 5053, irradiated formula. Euthanasia was performed via cervical dislocation under deep anesthesia.

For NHP studies, all experimental procedures performed were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center (Fred Hutch) and University of Washington (UW; Protocol #3235-01). This study was carried out in strict accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health (“The Guide”), and monkeys were randomly assigned to the study. Healthy juvenile rhesus macaques were housed at the UW National Primate Research Center (WaNPRC) under conditions approved by the American Association for the Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care. This study included at least twice-daily observation by animal technicians for basic husbandry parameters (e.g., food intake, activity, stool consistency, and overall appearance), as well as daily observation by a veterinary technician and/or veterinarian. Animals were housed in cages in accordance with Animal Welfare Act regulations. Animals were fed twice daily and were fasted for up to 14 h prior to sedation. Environmental enrichment included grouping in compound, large activity, or run-through connected cages, perches, toys, food treats, and foraging activities. If a clinical abnormality was noted by WaNPRC personnel, standard WaNPRC procedures were followed to notify the veterinary staff for evaluation and determination for admission as a clinical case. Animals were sedated by administration of ketamine HCl and/or telazol and supportive agents prior to all procedures. Following sedation, animals were monitored according to WaNPRC standard protocols. WaNPRC surgical support staff are trained and experienced in the administration of anesthetics and have monitoring equipment available to assist with electronic monitoring of heart rate, respiration, and blood oxygenation; audible alarms and LCD readouts; monitoring of blood pressure, temperature, etc. Analgesics were provided as prescribed by the Clinical Veterinary staff for at least 48 h after the procedures and could be extended at the discretion of the clinical veterinarian, based on clinical signs.

Base editor protein/mRNA production and purification

For protein expression, ABE8e and BE4max were codon optimized for bacterial expression and cloned into the protein expression plasmid pD881-SR (Atum, Cat. No. FPB-27E-269). The expression plasmid was transformed into BL21 Star DE3 competent cells (ThermoFisher, Cat. No. C601003). Colonies were picked for overnight growth in TB+25 ug/mL kanamycin at 37 °C. The next day, 2 L of pre-warmed TB were inoculated with overnight culture at a starting OD600 of 0.05. Cells were shaken at 37 °C for about 2.5 h until the OD was ~1.5. Cultures were cold shocked in an ice-water slurry for 1 hour, following which D-rhamnose was added to a final concentration of 0.8%. Cultures were then incubated at 18 °C with shaking for 24 h to induce protein expression. Following induction, cells were pelleted and flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 degrees. The next day, cells were resuspended in 30 mL cold lysis buffer (1 M NaCl, 100 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.0, 5 mM TCEP, 20% glycerol, with 5 tablets of complete, EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail tablets (Millipore Sigma, Cat. No. 4693132001). Cells were passed 3 times through a homogenizer (Avestin Emulsiflex-C3) at ~18000 psi to lyse. Cell debris was pelleted for 20 min using a 20,000 x g centrifugation at 4 °C. Supernatant was collected and spiked with 40 mM imidazole, followed by a 1 h incubation at 4 °C with 1 mL of Ni-NTA resin slurry (G Bioscience Cat. No. 786–940, prewashed once with lysis buffer). Protein-bound resin was washed twice with 12 mL of lysis buffer in a gravity column at 4 °C. Protein was eluted in 3 mL of elution buffer (300 mM imidazole, 500 mM NaCl, 100 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.0, 5 mM TCEP, 20% glycerol). Eluted protein was diluted in 40 mL of low-salt buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.0, 5 mM TCEP, 20% glycerol) just before loading into a 50 mL Akta Superloop for ion exchange purification on the Akta Pure25 FPLC. Ion exchange chromatography was conducted on a 5 mL GE Healthcare HiTrap SP HP pre-packed column (Cat. No. 17115201). After washing the column with low salt buffer, the diluted protein was flowed through the column to bind. The column was then washed in 15 mL of low salt buffer before being subjected to an increasing gradient to a maximum of 80% high salt buffer (1 M NaCl, 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.0, 5 mM TCEP, 20% glycerol) over the course of 50 mL using a flow rate of 5 mL per minute. 1 mL fractions were collected during this ramp to high salt buffer. Peaks were assessed by SDS-PAGE to identify fractions containing the desired protein, which were concentrated first using an Amicon Ultra 15 mL centrifugal filter (100 kDa cutoff, Cat. No. UFC910024), followed by a 0.5 mL 100 kDa cutoff Pierce concentrator (Cat. No. 88503). Concentrated protein was quantified using a BCA assay (ThermoFisher, Cat. No. 23227).

For mRNA production, ABE8e, ABE8e-NG and BE4max were ordered as custom products from Trilink Biotechnologies. mRNAs were transcribed in vitro from PCR product using full substitution of N1-methylpseudouridine for uridine and was capped co-transcriptionally using the CleanCap AG analogue (Trilink Biotechnologies), resulting in a 5’ Cap 1 structure. The in vitro transcription reaction was performed as previously described17,65. Mammalian-optimized UTR sequences (Trilink) and a 120-base poly-A tail were included in the transcribed PCR product.

Culture and editing of CD34+ HSPCs

CD34+ Cord Blood cells were obtained from de-identified healthy adult donors (Stemexpress, or Lonza). For mobilized peripheral blood CD34+ cells, primary human CD34+ cells were purchased from the Co-operative Center for Excellence in Hematology (CCEH) at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center. Collections were performed according to the Declaration of Helsinki and were approved by a local Ethics Committee/Institutional Review Board of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center. All healthy adult donors were mobilized with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF). Human CD34+ cells were enriched as previously described on a CliniMACS Prodigy according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Miltenyi Biotec). Human fetal liver CD34+cells were enriched using a similar process from tissue obtained from Advance Bioscience Resources Inc. (ABR, Alameda, CA). Nonhuman primate CD34+ cells were harvested, enriched, and cultured as previously described41,55. Briefly, before enrichment of NHP CD34+ cells, red cells were lysed in ammonium chloride lysis buffer, and WBCs were incubated for 20 min with the 12.8 immunoglobulin-M anti-CD34 antibody, then washed and incubated for another 20 min with magnetic-activated cell-sorting anti-immunoglobulin-M microbeads (Miltenyi Biotech). Cells were cultured and expanded in StemSpan SFEM II (StemCell technologies) containing 1% Penicillin Streptomycin, 100 ng/mL TPO, 100 ng/mL SCF, 100 ng/mL IL6 and 100 ng/mL FLT3L at 37 °C, 85% relative humidity, and 5% CO2 (human cytokines from Biolegend or PeproTech). Cord blood CD34+ cells were additionally cultured with UM171 0.35 nM (Xcessbio). In colony-forming cell assays, 1000–1200 sorted cells were seeded into 3.5 ml ColonyGEL 1402 (ReachBio). Additional information on donors is provided in Table S3.

Chemically modified sgRNA were purchased from Synthego. For base editor protein, RNP were formed by mixing 5 to 9 μg base editor protein with 1.5 μg of sgRNA in 20 μL of P3 buffer (Lonza, Amaxa P3 Primary Cell 4D-Nucleofector Kit) and incubated for 10 mins. Then cells were electroporated at 50 million cells per mL. For multiplex editing, ABE8e-NG mRNA was exclusively used. In these experiments, electroporation reactions were conducted using 3 μg mRNA combined with 100 pmol of each CD33 and HBG sgRNA for 1 million cells using the ECM 380 Square Wave Electroporation system (Harvard Apparatus).

In vitro phagocytosis assay

CD34+ Unedited or CD33Δ2-edited CD34+cells were differentiated into monocytes for 14 days, with StemSpan SFEM II containing 1% Penicillin Streptomycin and the StemSpan Myeloid Expansion Supplement II (StemCell Technologies). At day 15, differentiated monocytes were preincubated for 30 mins with PBS or 25 μM Cytochalasin D and then incubated with pHrodo red E coli bioparticles (Thermofisher) with or without 25 μM cytochalasin D for 1 h 30 mins. Cells were then transferred to FACS tubes, washed with PBS-1% FBS and incubated 10 mins at RT with Human TruStain FcX and True-Stain Monocyte blocker (Biolegend). Antibody mix containing CD14-APCFire750, CD13-BV786, CD34-BV421, CD33-APC (Biolegend) and ebioscience fixable viability dye e450 (Thermofisher) was then added directly. After 25 mins of incubation, cells were washed and phagocytosis assessed by FACS.

In vitro cytotoxicity assay

CD34+Unedited or CD33Δ2-edited CD34+ cells carrying heterozygous or homozygous rs12459419 SNP or MOLM14 cells were incubated in triplicate with or without GO for 24 or 48 h. Cells were then washed and stained with viability dye 7AAD (Biolegend) or Sytox blue (Thermofisher) and immediately analyzed by FACS. CD3/CD33 BiAb-induced cytotoxicity was determined as previously described3. Briefly, AML cells were incubated at 37 °C (in 5% CO2 and air) in 96-well round-bottom plates (BD Biosciences) at 5 to 10 × 103 cells per well containing various concentrations of the Bispecific T cell engager (generated from published sequences using methods similar to those reported previously66, as well as T cells at different effector to target (E:T) cell ratios. After 48 h, cell numbers and drug-induced cytotoxicity, using 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) to detect non-viable cells, were determined by FACS (BD Biosciences).

CIRCLE-seq off target editing analysis

To identify base editing off target sites, genomic DNA was extracted from CD34+ cells with the QIAgen Gentra PureGene kit. CIRCLE-seq was performed as previously described52. Briefly, purified genomic DNA was sheared with a Covaris S2 instrument to an average length of 300 bp. The fragmented DNA was end repaired, A-tailed and ligated to an uracil-containing stem-loop adaptor, using KAPA HTP Library Preparation Kit, PCR Free (KAPA Biosystems). Adaptor ligated DNA was treated with Lambda Exonuclease (NEB) and E. coli Exonuclease I (NEB) and then with USER enzyme (NEB) and T4 polynucleotide kinase (NEB). Intramolecular circularization of the DNA was performed with T4 DNA ligase (NEB) and residual linear DNA was degraded by Plasmid-Safe ATP-dependent DNase (Lucigen). In vitro cleavage reactions were performed with 250 ng of Plasmid-Safe-treated circularized DNA, 90 nM of Cas9 nuclease (NEB), Cas9 nuclease buffer (NEB) and 90 nM of synthetically modified sgRNA (Synthego) in 100 μL volume. Cleaved products were A-tailed, ligated with a hairpin adaptor (NEB), treated with USER enzyme (NEB) and amplified by PCR with barcoded universal primers NEBNext Multiplex Oligos for Illumina (NEB), using Kapa HiFi Polymerase (KAPA Biosystems). Libraries were sequenced with 150 bp paired-end reads on an Illumina MiSeq instrument. CIRCLE-seq data analyses were performed using open-source CIRCLE-seq analysis software (https://github.com/tsailabSJ/circleseq) using default parameters. The human genome GRCh37 was used for alignment.

Quantification of base-editing efficiency at on-target and off-target sites with High throughput sequencing (HTS) using the Illumina MiSeq

To assess the on-target and off-target editing, we sequenced the CD33 locus and the 19 top off-target sites nominated by CIRCLE-seq. Genomic DNA from CD34+ cells or BM of transplanted mice was extracted with the QuickExtract™ DNA Extraction Solution (Lucigen). For CD33 and each off-target site, we designed human specific primers to generate a 250–300 bp product including the aligned off-target binding site for the guide RNA, and appended adapters (in italic) for Illumina sequencing. To investigate ABE8e mediated editing, the CD33 locus was amplified from genomic DNA using the following primers: Forward 5’-ACACTCTTTCCCTACACGACGCTCTTCCGATCTNNNNCCTCCACTCCCTTCCTCTTT-3’and the Reverse 5’-TGGAGTTCAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCTCTTCCCGGAACCAGTAACCA-3’. To investigate BE4max/sgCBE1 mediated editing, the CD33 locus was amplified with the Forward 5’-ACACTCTTTCCCTACACGACGCTCTTCCGATCTNNNNAGACATGCCGCTGCTGCTA-3’ and the Reverse 5’-TGGAGTTCAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCCCGGAACCAGTAACCATGAAC-3’. Following a secondary PCR to barcode each sample, products were pooled and sequenced using a 300 cycle v2 Illumina MiSeq kit. To analyze editing outcomes in resulting fastq files, we used CRISPResso267 to align each read to the reference amplicon and quantify indels or base changes.

In the multiplex editing experiments, editing was quantitated by next generation sequencing (NGS) or by EditR as follow. Genomic DNA was extracted using QIAamp DNA micro kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD, U.S.), and processed by PCR amplification using the primers described in Table S1. In NGS, libraries were prepared using Illumina barcoded, 2 × 150 base-pair (bp), pair-end and run on the MiSeq platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). In TIDE analysis, amplicons were sequenced by Sanger sequences and analyzed using the web-based EditR program68. The raw bioinformatic data and custom R code generated for the analysis of editing efficiency are available on GitHub (https://github.com/KiemLab-RIS/CD33_Base_editing_Miseq) and Zenodo (https://zenodo.org/records/15190299).

Mouse transplantation experiments

Columbia University

NOD.Cg-Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl Tg(CMV-IL3, CSF2, KITLG)1Eav/MloySzJ (NSGS) or NOD.Cg-Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ (NSG) female mice (The Jackson Laboratory) were conditioned with sublethal (1.2 Gy) total-body irradiation (TBI). Human Cord Blood stem cells (1 × 106per mouse) were injected intravenously into the mice within 8–24 h post-TBI. Engraftment and repopulation of the hematopoietic system over time, was assessed by analysis of peripheral blood, whole BM and spleen using the consequent antibodies from Biolegend or BD Biosciences: Ter119-PeCy5, Ly5/H2kD-BV711, hCD45-BV510, hCD3-Pacific Blue, hCD123-BV605, hCD33-APC, hCD14-APC/Fire750, hCD10-BUV395, hCD19-BV650. Dead cells were excluded using Propidium Iodide. For in vivo GO treatment, engraftment and hematopoietic repopulation was assessed in BM (aspiration) and peripheral blood. Mice were then injected intravenously with GO (resuspended in water) at the indicated concentration. One week after treatment, BM and peripheral blood were analyzed for the presence of myeloid cells by FACS. All data were acquired with the Bio-Rad ZE5 flow cytometry analyzer and data analysis were performed using FlowJo 10.8.1. All in vivo experiments were performed under protocols approved by the institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Columbia University.

Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center

NSG (non-obese diabetic NOD.Cg-Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ) male or female mice were irradiated at 275 cGy (adult) or of 150 cGy (neonate). 4 h later, mice were intravenously or intrahepatically injected with 1 × 106 (adult model) or 0.3 × 106 (neonate model) CD34+ cells, respectively, resuspended in 1X PBS with 1% heparin (APP Pharmaceuticals, East Schaumburg, IL, U.S.) to a total volume of 200 μl (adult) or 30 μl (neonate). Beginning at 8 weeks post-injection, blood samples were collected every 2 to 4 weeks and analyzed by flow cytometry. At time of necropsy, animals were sacrificed, and tissues harvested and analyzed. Lineage and HSC assessment from blood or BM were performed by flow cytometry utilizing antibody panel described in Table S2, and run on the BD FACSCanto II or BD Symphony Flow Cytometer (BD Biosciences). Data were acquired using FACSDiva version 6.1.3 and newer (BD Biosciences). Data analysis was performed using FlowJo version 8 and higher (BD Biosciences). For BM CFCs assays, 7 × 104/ml cells were plated in ColonyGELTM 1402 (ReachBio, Seattle, WA, U.S.) in triplicate from each mouse BM. Colonies were counted and picked for genomic analysis after 14 days.

NHP transplant experiments

Autologous NHP transplants were conducted as described previously for CRISPR/Cas9-editing of the CD90+ subset41. Briefly, male rhesus macaques were conditioned with myeloablative total body irradiation (TBI) of 1020 cGy from a 6 MV x-ray beam of a single-source linear accelerator located at the Fred Hutch South Lake Union Facility (Seattle, Washington, USA). The dose was administered at a rate of 7 cGy/min delivered as a midline tissue dose. After transplant, G-CSF was administered daily from the day of cell infusion until the animals began to show onset of neutrophil recovery. Supportive care, including antibiotics, electrolytes, fluids, and transfusions, was given as necessary, and blood counts were analyzed daily to monitor hematopoietic recovery. Editing from blood and BM was tracked in the transplanted animals as described in the section above, and HbF and multilineage reconstitution was monitored by flow cytometry as described previously41,57 and using the antibodies listed in Table S2.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information. Source data is available for all figures in the associated source data file. Source data are provided with this paper. Illumina sequencing primers are provided in Supplementary Table 2, along with the link to the CIRCLE-seq and CRISPResso2 analysis software used in this study. HTS sequencing files can be accessed using the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (PRJNA1222463, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA1222463). Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

Custom scripts designed for the analysis of editing efficiency have been deposited into GitHub repository https://github.com/KiemLab-RIS/CD33_Base_editing_Miseq and Zenodo https://zenodo.org/records/15190299.

References

Borot, F. et al. Gene-edited stem cells enable CD33-directed immune therapy for myeloid malignancies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 116, 11978–11987 (2019).

Kim, M. Y. et al. Genetic Inactivation of CD33 in Hematopoietic Stem Cells to Enable CAR T Cell Immunotherapy for Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Cell 173, 1439–1453.e1419 (2018).

Humbert, O. et al. Engineering resistance to CD33-targeted immunotherapy in normal hematopoiesis by CRISPR/Cas9-deletion of CD33 exon 2. Leukemia 33, 762–808 (2019).

Genovese, P. et al. Targeted genome editing in human repopulating haematopoietic stem cells. Nature 510, 235–240 (2014).

Schiroli, G. et al. Precise Gene Editing Preserves Hematopoietic Stem Cell Function following Transient p53-Mediated DNA Damage Response. Cell Stem Cell 24, 551–565.e558 (2019).

Samuelson, C. et al. Multiplex CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing in hematopoietic stem cells for fetal hemoglobin reinduction generates chromosomal translocations. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 23, 507–523 (2021).

Song, Y. et al. Large-Fragment Deletions Induced by Cas9 Cleavage while Not in the BEs System. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 21, 523–526 (2020).

Bertaina, A., Bernardo, M. E., Mastronuzzi, A., La, Nasa,G. & Locatelli, F. The role of reduced intensity preparative regimens in patients with thalassemia given hematopoietic transplantation. Ann. N. Y Acad. Sci. 1202, 141–148 (2010).

Czechowicz, A. et al. Selective hematopoietic stem cell ablation using CD117-antibody-drug-conjugates enables safe and effective transplantation with immunity preservation. Nat. Commun. 10, 617 (2019).

Kwon, H. S. et al. Anti-human CD117 antibody-mediated bone marrow niche clearance in nonhuman primates and humanized NSG mice. Blood 133, 2104–2108 (2019).

Taussig, D. C. et al. Hematopoietic stem cells express multiple myeloid markers: implications for the origin and targeted therapy of acute myeloid leukemia. Blood 106, 4086–4092 (2005).

Knapp, D. et al. Single-cell analysis identifies a CD33(+) subset of human cord blood cells with high regenerative potential. Nat. Cell Biol. 20, 710–720 (2018).

Beard, B. C. et al. Long-term polyclonal and multilineage engraftment of methylguanine methyltransferase P140K gene-modified dog hematopoietic cells in primary and secondary recipients. Blood 113, 5094–5103 (2009).

Beard, B. C. et al. Efficient and stable MGMT-mediated selection of long-term repopulating stem cells in nonhuman primates. J. Clin. Invest 120, 2345–2354 (2010).

Agudelo, D. et al. Marker-free coselection for CRISPR-driven genome editing in human cells. Nat. Methods 14, 615–620 (2017).

Li, S. et al. Universal toxin-based selection for precise genome engineering in human cells. Nat. Commun. 12, 497 (2021).

Newby, G. A. et al. Base editing of haematopoietic stem cells rescues sickle cell disease in mice. Nature 595, 295–302 (2021).

Koblan, L. W. et al. In vivo base editing rescues Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome in mice. Nature 589, 608–614 (2021).

Yeh, W. H. et al. In vivo base editing restores sensory transduction and transiently improves auditory function in a mouse model of recessive deafness. Sci. Transl. Med. 12, https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.aay9101 (2020).

Zeng, J. et al. Therapeutic base editing of human hematopoietic stem cells. Nat. Med. 26, 535–541 (2020).

Metais, J. Y. et al. Genome editing of HBG1 and HBG2 to induce fetal hemoglobin. Blood Adv. 3, 3379–3392 (2019).

Weber, L. et al. Editing a gamma-globin repressor binding site restores fetal hemoglobin synthesis and corrects the sickle cell disease phenotype. Sci. Adv. 6, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aay9392 (2020).

Traxler, E. A. et al. A genome-editing strategy to treat beta-hemoglobinopathies that recapitulates a mutation associated with a benign genetic condition. Nat. Med. 22, 987–990 (2016).

Liu, N. et al. Transcription factor competition at the gamma-globin promoters controls hemoglobin switching. Nat. Genet 53, 511–520 (2021).

Gaudelli, N. M. et al. Directed evolution of adenine base editors with increased activity and therapeutic application. Nat. Biotechnol. 38, 892–900 (2020).

Webber, B. R. et al. Highly efficient multiplex human T cell engineering without double-strand breaks using Cas9 base editors. Nat. Commun. 10, 5222 (2019).

Rees, H. A. et al. Improving the DNA specificity and applicability of base editing through protein engineering and protein delivery. Nat. Commun. 8, 15790 (2017).

Komor, A. C., Kim, Y. B., Packer, M. S., Zuris, J. A. & Liu, D. R. Programmable editing of a target base in genomic DNA without double-stranded DNA cleavage. Nature 533, 420–424 (2016).

Perez-Oliva, A. B. et al. Epitope mapping, expression and post-translational modifications of two isoforms of CD33 (CD33M and CD33m) on lymphoid and myeloid human cells. Glycobiology 21, 757–770 (2011).

Karczewski, K. J. et al. The mutational constraint spectrum quantified from variation in 141,456 humans. Nature 581, 434–443 (2020).

Baxter, S. K. et al. https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/variant/19-51225221-C-T?dataset=gnomad_r4 (Global Core Biodata Resource (GCBR), 2023 (2023).

GTEx Consortium. The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) Project was supported by the Common Fund of the Office of the Director of the National Institutes of Health, a. b. N. The data used for the analyses described in this manuscript were obtained from: https://www.gtexportal.org/home/snp/chr19_51225221_C_T_b51225238#sqtl-block the GTEx Portal (2023).

Li, Y. I. et al. Annotation-free quantification of RNA splicing using LeafCutter. Nat. Genet. 50, 151–158 (2018).

Lamba, J. K. et al. CD33 Splicing Polymorphism Determines Gemtuzumab Ozogamicin Response in De Novo Acute Myeloid Leukemia: Report From Randomized Phase III Children’s Oncology Group Trial AAML0531. J. Clin. Oncol. 35, 2674–2682 (2017).

Laszlo, G. S. et al. Relationship between CD33 expression, splicing polymorphism, and in vitro cytotoxicity of gemtuzumab ozogamicin and the CD33/CD3 BiTE(R) AMG 330. Haematologica 104, e59–e62 (2019).

Lamba, J. K. et al. Coding polymorphisms in CD33 and response to gemtuzumab ozogamicin in pediatric patients with AML: a pilot study. Leukemia 23, 402–404 (2009).

Mortland, L. et al. Clinical significance of CD33 nonsynonymous single-nucleotide polymorphisms in pediatric patients with acute myeloid leukemia treated with gemtuzumab-ozogamicin-containing chemotherapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 19, 1620–1627 (2013).

Yuan, J. et al. Genetic Modulation of RNA Splicing with a CRISPR-Guided Cytidine Deaminase. Mol. Cell 72, 380–394.e387 (2018).

Billon, P. et al. CRISPR-Mediated Base Editing Enables Efficient Disruption of Eukaryotic Genes through Induction of STOP Codons. Mol. Cell 67, 1068–1079.e1064 (2017).

Godwin, C. D. et al. Targeting the membrane-proximal C2-set domain of CD33 for improved CD33-directed immunotherapy. Leukemia 35, 2496–2507 (2021).

Humbert, O. et al. Therapeutically relevant engraftment of a CRISPR-Cas9-edited HSC-enriched population with HbF reactivation in nonhuman primates. Sci. Transl. Med. 11, https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.aaw3768 (2019).

Lux, C. T. et al. TALEN-Mediated Gene Editing of HBG in Human Hematopoietic Stem Cells Leads to Therapeutic Fetal Hemoglobin Induction. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 12, 175–183 (2019).

Cheng, L. et al. Single-nucleotide-level mapping of DNA regulatory elements that control fetal hemoglobin expression. Nat. Genet. 53, 869–880 (2021).

Ravi, N. S. et al. Identification of novel HPFH-like mutations by CRISPR base editing that elevate the expression of fetal hemoglobin. Elife 11, https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.65421 (2022).