Abstract

Strong and lightweight materials are highly desired. Here we report the emergence of a compressive strength exceeding 2 GPa in a directly printed poly(ethylene glycol) micropillar. This strong and highly crosslinked micropillar is not brittle, instead, it behaves like rubber under compression. Experimental results show that the micropillar sustains a strain approaching 70%, absorbs energy up to 310 MJ/m3, and displays an almost 100% recovery after cyclic loading. Simple micro-lattices (e.g., honeycombs) of poly(ethylene glycol) also display high strength at low structural densities. By combining a series of control experiments, computational simulations and in situ characterization, we find that the key to achieving such mechanical performance lies in the fabrication of a highly homogeneous structure with suppressed defect formation. Our discovery unveils a generalizable approach for achieving a performance leap in polymeric materials and provides a complementary approach to enhance the mechanical performance of low-density latticed structures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ultrasmall structures of metals and ceramics exhibit anomalous mechanical behavior compared to their bulk counterparts1,2,3,4,5,6. At the scale of micro- and nanometers, ceramics have shown large elastic1 or even plastic6 deformation, and metals have demonstrated significantly enhanced strength4. This is because that it is possible to fabricate high-quality structures at the ultrasmall scale, which eliminates the detrimental effects of defects1,2. Meanwhile, the strengthening4 and toughening6 effects of microstructures (e.g., grain boundary4 and dual phase6) are significantly amplified in small structures. In recent years, nanolatticed ceramics and metals, which are obtained via the post-treatments (e.g., carbonization, inorganic coating and polymer matrix removal) of the printed polymer lattices, have demonstrated further improved mechanical performance due to the efficient integration of the architecture and size effects7,8. In contrast to metals and ceramics, small structures of polymers9,10 are easier to fabricate. However, so far, structural polymers have rarely demonstrated significantly improved mechanical performance on the micrometer-scale. This may be attributed to the lack of a successful combination of suitable polymeric formulations with current microfabrication techniques, which could produce the defect-free structures with desired microstructural features.

In many polymer-network materials, the actual ultimate strength and compressibility are much lower than theoretical predictions due to the uncontrollable formation of various types of defects11,12. Spatial inhomogeneity of crosslinking, dangling bonds, and loops can be easily formed during the free-radical polymerization of monomers and crosslinkers13. These defects cause stress concentration and mechanical fragility in polymeric networks, particularly in those highly crosslinked systems. In the past two decades, these issues have been partially resolved by several specific molecular-design strategies. These include the design of double-network14, the introduction of non-covalent or sacrificial crosslinker15,16,17,18, and the utilization of entanglements19 and four-arm monomers20. On the other hand, our recent work21 shows that the incorporation of emerging inorganic nanomaterials into polymer architectures could significantly enhance the mechanical performance. However, a generalizable fabrication strategy to achieve the homogeneous networks with suppressed formation of defects is still lacking for commonly used polymers formed by free radical polymerization. And the theoretically predicted mechanical limit of polymer networks are still difficult to be realized.

Over the past several decades, great interest lies in a polymer material known as poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG for short hereafter) because of its tunability, adaptability, and biocompability22. With the addition of two end di-acrylate groups, poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate (PEGDA for short hereafter) can be easily crosslinkable to form polymeric network using a initiator under photoexcitation, thus it has become one of the most used photopolymer in 3D printing23,24. So far, the reported strength of PEG-based structures are normally less than tens of megapascals25,26,27, and these “strong” PEG-based networks with high crosslinking degree are typically brittle25,26,27.

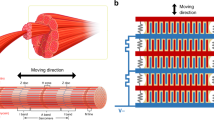

Our high-strength, highly compressive PEG micropillars were obtained via the two-photon printing which constructs 3D structures via a point-by-point (or voxel-by-voxel) polymerization (Fig. 1A). Although two-photon polymerization is well-known for its ability to print high-precision 3D structures28,29,30, thus far, little attention has been paid to its capability of controlling the network feature of polymers, and its potential in enhancing the homogeneity of the covalent-crosslinking network has been rarely exploited. Two-photon volumetric printing using a strong, near-infrared femtosecond laser under high scanning speeds could ensure that radicals are quickly and evenly formed in every voxel of the structure (Fig. 1A). This could avoid the non-uniform generation or the trapping of radicals31 that commonly exists in radical polymerizations, and suppress the inter-layer defects which are typically generated in other layer-by-layer 3D printing processes. We envision that by the judicious tailoring of the photopolymerization materials systems and the printing parameters, the long-time pursued crosslinking network with previously unachievable mechanical performance could be obtained at the small scale.

A Schematic diagram of the feedstock composition, microfabrication setup and the network formation of PEG-based micropillars. Right: SEM image of the printed pillar. B Compressive stress-strain curves of PEG-based micropillars with the addition of 4 wt% PETA. Insets are the SEM images of two micropillars (different height-to-diameter ratios) before and after compression. C Compressive stress-strain curves of PEG micropillars. Insets are the SEM images of two micropillars before and after compression. D Comparison of the stress-strain curve of PEG-based micropillar with other PEG-based macroscale structures. E Comparison of the stress-strain curve of PEG-based micropillar with other materials. Data are reproduced from refs. 4,25,27,34,35,36,37,38. Scale bar: 2 μm.

Results

We chose a PEG-based photoresist (Fig. 1A) in which PEGDA400 (molecular weight = 400, >94 wt%) is used as the monomer, 7-diethylamino-3-thenoylcoumarin (DETC, <2 wt%) is used as the photoinitiator. To enhance the printability, very few pentaerythritol triacrylate (PETA, <4 wt%) is also added into the resin. The PEGDA400 monomer has a relatively long intervinyl distance (10.6 Å), thus it prefers interchain crosslinking32,33 more than intrachain cyclization (i.e., loops) during the photopolymerization. We chose a high laser power to ensure that all the DETC photoinitiators can be excited within a very short time and radicals are formed much faster than the chain propagation33. We adjusted the printing parameters (details in Suplementary Information) to ensure that almost all the C=C bonds can be reacted, with the degree of conversion approaching 100%. The detailed calculations of the photopolymerization dynamics under our printing conditions are displayed in supporting information. We envision that this system could effectively suppress the formation of defects, including the inhomogeneity of crosslinking, dangling bonds, and loops.

The printed micropillar demonstrates an ultrahigh strength up to 2.34 GPa with a compressive strain approaching 70%, and it displays an almost 100% recovery (97.2% in average) after unloading (Fig. 1B). Without the addition of the 4 wt% PETA, PEG micropillar still displays a strength up to 2.68 GPa and a compression strain approaching 70 %, yet the recoverability slightly declines to ~90 % (Fig. 1C). The toughness of our PEG-based micropillar reaches 310 MJ/m3. As shown in Fig. 1D, the compressive strength of our PEG-based micropillar is one-to-three-order-of-magnitudes higher than previously reported PEG-based structures25,27. Furthermore, our ultrastrong PEG-based micropillar behaves like a resilient rubber, rather than a brittle plastic under compression.

Raman and Fourier-transform Infrared results demonstrate that almost all C=C bonds (>95%) have been reacted (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2), suggesting a superhigh crosslinking degree of ~1.5 ×1027 m−3 (or 1.5 nm−3, 1.5 crosslinking points per 1 nm3) and negligible dangling bonds in the printed network. Raman, Fourier-transform infrared and laser confocal microscopy results suggest that the polymer network in our pillars is highly homogeneous (Supplementary Figs. 1–3). Thus, the striking improvement of the mechanical performance of our micropillars compared to previous PEG-based structures25,26,27 should arise from the suppression of defects that commonly exist in large structures of highly crosslinking systems31.

Figure 1E compares the compression behavior of our PEG-based micropillar with other metal4, ceramic6,34,35, composite21,36 and polymeric37,38,39 micropillars. Polymer (SU-8 and polystyrene) micropillars fabricated from other methods (e.g., focused ion beam etching, 2D lithography) show a significant yield and post-yield softening, with their strength limited to a few hundreds of MPa. Micro- or nano-pillars of metals and ceramics display high strength above 1 GPa4,35, but they either fracture or yield at limited strains.

We further compare the mechanical performance of our PEG-based micropillars with other structural materials. As shown in Fig. 2A, B, the high strength, compressibility and recovery of our PEG-based micropillars combine the merits of rubbers and ceramics, which expands the performance space of structural materials. Compressive strength and compressibility (strain) are two critical factors which dominate the overall performance of structural materials in many applications such as energy dissipation, cushioning, and packaging40. However, in many cases, these two properties are mutually exclusive.

More compressive stress-strain curves are displayed in Supplementary Figs. 4–12. The true stress-strain curve of our PEG-based micropillar is shown in Supplementary Fig. 9, in which the strain-hardening behavior can also be observed, and the ultimate true strength approaches 1.59 GPa. We further conducted a series of control experiments to unravel the structure-property relationships of PEG-based micropillars. We printed the micropillars using PEGDA monomers with different molecular weights (i.e., PEGDA200, PEGDA400 and PEGDA700) under the same condition, and compared their mechanical behaviors. This difference could arise from the distinct crosslinking degree. Lower monomer weight of PEGDA200 leads to the higher crosslinking degree, which stiffens the printed structure. And the higher monomer weight of PEGDA700 leads to the lower crosslinking degree, which softens the printed structure. All these PEG-based micropillars display high strength. Micropillars made of PEGDA200 are stiffer but fail when compressed to 40%, and micropillars made of PEGDA700 are softer with degraded recoverability (Supplementary Fig. 10). Meanwhile, PEGDA400-based pillars printed under lower laser powers (Supplementary Fig. 13) have decreased crosslinking degree (characterized by Raman measurement), which become slightly softer. These results indicate the tunability of the materials systems and mechanical performance based on our fabrication framework.

In-situ SEM compression tests of our PEG-based micropillars are shown in Fig. 3A and Supplementary Movie 1. PEG-based micropillars deform uniformly under the compression. Surface wrinkling and cracks were observed in some of our PEG-based micropillars when being compressed in SEM (Supplementary Fig. 14 and Supplementary Movie 2). Normally, surface wrinkling is observed in those stiff films on soft substrates41 under external stresses due to the mismatch of modulus. This structure gradience (hard surface with a softer core) can hinder the propagation of surface crack42,43, as observed in our micropillars (Supplementary Fig. 15 and Supplementary Movie 2). Of note, different from the in-situ SEM tests (vacuum, humidity = 0), cracks were rarely found in our micropillars when compressed under ambient condition (humidity ~60%). We ascribe these different phenomena to the fact that under the SEM vacuum environment (humidity = 0), the absorbed water molecules (~6 wt%, Supplementary Fig. 16) on surface layers could be vacuumized, which leads to the hard surface and core-shell gradience. Similar effects of humidity on the crack formation were previously observed in hydrophilic high-crosslinking networks44,45.

A In situ SEM compression of PEG-Based Micropillar. Scale bar: 10 μm. B Engineering stress-strain curves of 10 cyclic tests of PEG-based micropillar. C SEM images of the PEG-based micropillar before and after the cyclic compression. Scale bar: 5 μm. D Coarse-grained modeling of the photoresist and the largest interconnected molecular cluster in the cured network. E, F Compressive true stress–strain curves from simulated cured network (red line) and experimental measurements (black lines).

Figure 3B displays the cyclic test of the PEG-based micropillars under ambient condition. PEG-based micropillar displays high mechanical stability with a maximum stress retention of ~90% (Fig. 3B) and a recovery of 98% (Fig. 3C) after 10 compression cycles at a large strain of 50%. Very low hysteresis was observed after the first cycle (Fig. 3B). This is because that during the first-cycle loading, polymeric chains need to overcome significant internal friction and mutual slip resistance to rearrange, and the rupture of certain crosslinking points could occur, leading to notable viscous dissipation15,46. More cyclic tests of our micropillars are displayed in Supplementary Fig. 17. The ultimate strength and the dissipated energy (calculated from the area of the hysteresis loops) decreased slightly at first and then approached constant values after the second cycle.

We conducted coarse-grained molecular dynamics to elucidate the molecular-level mechanisms underpinning the mechanical characteristics of the PEG-based polymer network (details in the Suplementary Information). As shown in Fig. 3D, a simplified coarse-grained model was employed to simulate the components of the photoresist. The network was formed following the reaction scheme in Supplementary Fig. 18 which effectively mimics the chemical reactions during the photoinitiated polymerization. The extent of crosslinking reaction, i.e., the extend of double bond conversion is controlled to be ≈93%, as measured by Raman analysis. We further conducted compression simulations on the cured network to characterize its mechanical properties. Figure 3E, F demonstrates a good agreement between simulated and experimental stress–strain behavior. This suggests that the PEG-based micropillar realizes the network with negligible defects, thus the theoretical mechanical behavior of the corresponding ideal network could be experimentally achieved.

We further printed honeycomb structures with a density of 0.56 g/cm3 and a relative density of ~50%. As shown in Fig. 4A, B, the compressive stress-strain response is nonlinear, with significant hardening at large strains approaching ~60% strain without catastrophic failure. Our PEG-based honeycombs demonstrate an ultimate stress up to 1.2 GPa with an energy absorption approaching 180 MJ/m3 (the specific absorption of honeycomb is 325 J/g), and they display a recovery of ~94% after unloading. The small plastic deformation of the structure is probably from crack, leading to irreversible deformation of the structure. Such strength and toughness are much higher than previously reported polymeric honeycombs of similar structural densities40, and are on par with the current record holders, the glassy carbon micro-honeycombs which, however, are normally brittle. In-situ SEM compression of a typical PEG-based honeycomb structure is shown in Supplementary Movie 3. As shown in Fig. 4C, D, the specific strength and energy absorption of our pillars and honeycombs could fill in the white space of the Ashby charts.

A Compressive stress-strain curves of PEG-based honeycombs. Inset is a zoom-in of the initial curve. B SEM images of the honeycomb before and after compression. Scale bar: 3 μm. C Energy absorption versus density. D Compressive strength versus density. Data are reproduced from refs. 4,6,21,34,35,36,37,38,50.

Discussion

In summary, we print a PEG-based micropillar with a compressive strength exceeding 2 GPa, which is one-to-three-order-of-magnitudes higher than previously reported PEG-based structures. This highly-crosslinked micropillar can sustain a compressive strain up to 70% and displays an almost 100% recovery after cyclic loading. Such extraordinary performance can also be obtained in PEG-based lightweight honeycombs, of which the mechanical strength are on par with the glassy carbon at similar structural densities. We ascribe the concurrent high strength and rubber-like behavior to the very homogenous crosslinking with a suppressed defect formation in the two-photon-printed PEG micropillars and micro-honeycombs. This work provides an alternative approach to enhance the mechanical performance of low-density latticed structures.

Besides the PEG-based systems, there is a broad opportunity to print additional high-quality networks of other polymeric materials based on this simple framework. And in comparison to those benchmarking small structures of metals and ceramics1,2,3,4,5,6, polymer networks offer the advantages such as ease of fabrication and post-treatment (e.g., swelling47, heating27), and the flexibility to transform into other types of materials (e.g., hydrogels) and integrate into contemporary microdevices. Thus, current discovery may offer the potential for new applications of microscale polymeric structures in small artificial muscles, tissue engineering, flexible electronics, as well as micro-actuators. In addition, recent progresses in the scalable two-photon printing techniques48,49 may help realize the fabrication of desired polymer networks at larger scales.

Methods

Materials

PEGDA (Poly(ethylene glycol)diacrylate) (97%) and PETA (Pentaerythritol triacrylate) (97%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. DETC (7-Diethylamino-3-thenoylcoumarin) (97%) were purchased from Shanghai Yuanye Bio-Technology Co., Ltd.

Preparation of PEGDA photoresists

PEGDA (Poly(ethylene glycol)diacrylate), PETA (Pentaerythritol triacrylate), and DETC (7-Diethylamino-3-thenoylcoumarin) are commercially available and were used as received. The following photoresists were prepared and used for printing:

98 mg PEGDA400 + 2 mg DETC

96 mg PEGDA400 + 2 mg DETC + 2 mg PETA

94 mg PEGDA400 + 2 mg DETC + 4 mg PETA

94 mg PEGDA200 + 2 mg DETC + 4 mg PETA

94 mg PEGDA700 + 2 mg DETC + 4 mg PETA

Two-photon lithography

Two‐photon lithography experiments were conducted using the Photonic Professional GT system (from Nanoscribe GmbH) with a Zeiss Plan‐Apochromat 63×/1.4 Oil DIC objective and a 780 nm laser. A combination of galvo-mirrors and piezoelectric actuators were used to control the printing position. During the experiment, laser powers ranging from 10 to 50 mW and scanning speeds between 1 and 20 mm s−1 were applied. Glass with a thickness of 0.17 mm was used as the substrate. The photoresist was drop casted onto the substrate, and structures were created under the oil immersion mode. After the printing, the samples were developed in 2-acetoxy-1-methoxypropane for 30 min and then in 2-propanol for 10 min.

Mechanical testing

Compression testing was conducted using Anton Paar UNHT³ nanoindenter. A 200 μm diamond flat punch tip was used. The testing was performed at a strain rate of approximately 0.001–0.1 s−1. Recovery represents the ratio of height after unloading to the initial height.

In-situ SEM mechanical testing

Compression testing was performed using a Bruker PI 85 nanoindenter. Testing was performed under strain rates at 0.001–0.005 s−1. A 20 μm diamond flat punch tip was used for the compression of micropillars.

Characterization

Raman measurement was conducted using a LabRAM HR Evolution Raman microscope with a 633 nm laser. Nano-FTIR imaging was conducted using a Anasys nanoIR2-FS system. Laser confocal microscopy was conducted using a LEICA TCS SP8 system.

Data availability

The data generated in this study are provided in the Source Data file. All data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Banerjee, A. et al. Ultralarge elastic deformation of nanoscale diamond. Science 360, 300–302 (2018).

Xu, P. et al. Elastic ice microfibers. Science 373, 187–192 (2021).

Jang, D. & Greer, J. R. Transition from a strong-yet-brittle to a stronger-and-ductile state by size reduction of metallic glasses. Nat. Mater. 9, 215–219 (2010).

Uchic, M. D., Dimiduk, D. M., Florando, J. N. & Nix, W. D. Sample Dimensions Influence Strength and Crystal Plasticity. Science 305, 986–989 (2004).

Zhang, X. et al. Theoretical strength and rubber-like behaviour in micro-sized pyrolytic carbon. Nat. Nanotechnol. 14, 762–769 (2019).

Zhang, J. et al. Plastic deformation in silicon nitride ceramics via bond switching at coherent interfaces. Science 378, 371–376 (2022).

Ritchie, R. O. & Zheng, X. R. Growing designability in structural materials. Nat. Mater. 21, 968–970 (2022).

Bauer, J. et al. Nanolattices: an emerging class of mechanical metamaterials. Adv. Mater. 29, 1701850 (2017).

Li, J., Accardo, A. & Liu, S. Size effect in the compression of 3D polymerized micro-structures. J. Appl. Mech. 91, 011002 (2023).

Lemma, E. D. et al. Mechanical properties tunability of three-dimensional polymeric structures in two-photon lithography. IEEE Trans. Nanotechnol. 16, 23–31 (2017).

Zhong, M., Wang, R., Kawamoto, K., Olsen, B. D. & Johnson, J. A. Quantifying the impact of molecular defects on polymer network elasticity. Science 353, 1264–1268 (2016).

Danielsen, S. P. O. et al. Molecular characterization of polymer networks. Chem. Rev. 121, 5042–5092 (2021).

Seiffert, S. Origin of nanostructural inhomogeneity in polymer-network gels. Polym. Chem. 8, 4472–4487 (2017).

Gong, J. P., Katsuyama, Y., Kurokawa, T. & Osada, Y. Double-network hydrogels with extremely high mechanical strength. Adv. Mater. 15, 1155–1158 (2003).

Ducrot, E., Chen, Y., Bulters, M., Sijbesma, R. P. & Creton, C. Toughening elastomers with sacrificial bonds and watching them break. Science 344, 186–189 (2014).

Wang, Z. et al. Toughening hydrogels through force-triggered chemical reactions that lengthen polymer strands. Science 374, 193–196 (2021).

Huang, Z. et al. Highly compressible glass-like supramolecular polymer networks. Nat. Mater. 21, 103–109 (2022).

Wang, M. et al. Glassy gels toughened by solvent. Nature 631, 313–318 (2024).

Kim, J., Zhang, G., Shi, M. & Suo, Z. Fracture, fatigue, and friction of polymers in which entanglements greatly outnumber cross-links. Science 374, 212–216 (2021).

Sakai, T. et al. Design and fabrication of a high-strength hydrogel with ideally homogeneous network structure from tetrahedron-like macromonomers. Macromolecules 41, 5379–5384 (2008).

Li, Q. et al. Mechanical nanolattices printed using nanocluster-based photoresists. Science 378, 768–773 (2022).

Burdick, J. A. & Anseth, K. S. Photoencapsulation of osteoblasts in injectable RGD-modified PEG hydrogels for bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials 23, 4315–4323 (2002).

Lu, P. et al. Wavelength-selective light-matter interactions in polymer science. Matter 4, 2172–2229 (2021).

Fairbanks, B. D., Schwartz, M. P., Bowman, C. N. & Anseth, K. S. Photoinitiated polymerization of PEG-diacrylate with lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate: polymerization rate and cytocompatibility. Biomaterials 30, 6702–6707 (2009).

Klimaschewski, S. F., Küpperbusch, J., Kunze, A. & Vehse, M. Material investigations on poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate-based hydrogels for additive manufacturing considering different molecular weights. J. Mech. Energy Eng. 6, 33–42 (2022).

Wang, Z. et al. Tough, transparent, 3D-printable, and self-healing poly(ethylene glycol)-gel (PEGgel). Adv. Mater. 34, 2107791 (2022).

Surjadi, J. U. et al. Lightweight, ultra-tough, 3D-architected hybrid carbon microlattices. Matter 5, 4029–4046 (2022).

Li, L., Gattass, R. R., Gershgoren, E., Hwang, H. & Fourkas, J. T. Achieving λ/20 resolution by one-color initiation and deactivation of polymerization. Science 324, 910–913 (2009).

Kawata, S., Sun, H.-B., Tanaka, T. & Takada, K. Finer features for functional microdevices. Nature 412, 697–698 (2001).

Frenzel, T., Kadic, M. & Wegener, M. Three-dimensional mechanical metamaterials with a twist. Science 358, 1072–1074 (2017).

Kannurpatti, A. R., Anseth, J. W. & Bowman, C. N. A study of the evolution of mechanical properties and structural heterogeneity of polymer networks formed by photopolymerizations of multifunctional (meth)acrylates. Polymer 39, 2507–2513 (1998).

Gao, Y. et al. Complex polymer architectures through free-radical polymerization of multivinyl monomers. Nat. Rev. Chem. 4, 194–212 (2020).

Yu, Q., Zhu, Y., Ding, Y. & Zhu, S. Reaction behavior and network development in RAFT radical polymerization of dimethacrylates. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 209, 551–556 (2008).

Fang, W. et al. Organic–inorganic covalent–ionic molecules for elastic ceramic plastic. Nature 619, 293–299 (2023).

Guruprasad, T. S., Keryvin, V., Kermouche, G., Marthouret, Y. & Sao-Joao, S. Compressive behaviour of carbon fibres micropillars by in situ SEM nanocompression. Compos. Part A: Appl. Sci. Manuf. 173, 107699 (2023).

Schwiedrzik, J. et al. In situ micropillar compression reveals superior strength and ductility but an absence of damage in lamellar bone. Nat. Mater. 13, 740–747 (2014).

Guruprasad, T. S., Bhattacharya, S. & Basu, S. Size effect in microcompression of polystyrene micropillars. Polymer 98, 118–128 (2016).

Cherukuri, R. et al. In-situ SEM micropillar compression and nanoindentation testing of SU-8 polymer up to 1000 s−1 strain rate. Mater. Lett. 358, 135824 (2024).

Koch, T. et al. Approaching standardization: mechanical material testing of macroscopic two‐photon polymerized specimens. Adv. Mater. 36, 2308497 (2024).

Cao, A., Dickrell, P. L., Sawyer, W. G., Ghasemi-Nejhad, M. N. & Ajayan, P. M. Super-compressible foamlike carbon nanotube films. Science 310, 1307–1310 (2005).

Lei, X. et al. Customizable multidimensional self-wrinkling structure constructed via modulus gradient in chitosan hydrogels. Chem. Mater. 31, 10032–10039 (2019).

Feng, X. et al. Microalloyed medium-entropy alloy (MEA) composite nanolattices with ultrahigh toughness and cyclability. Mater. Today 42, 10–16 (2021).

Shi, P. et al. Hierarchical crack buffering triples ductility in eutectic herringbone high-entropy alloys. Science 373, 912–918 (2021).

Itagaki, H. et al. Water-induced brittle-ductile transition of double network hydrogels. Macromolecules 43, 9495–9500 (2010).

Tominaga, T. et al. Hydrophilic double-network polymers that sustain high mechanical modulus under 80% humidity. ACS Macro Lett. 1, 432–436 (2012).

Mullins, L. Softening of rubber by deformation. Rubb. Chem. Tech. 1, 339–362 (1969).

Liu, C. et al. Tough hydrogels with rapid self-reinforcement. Science 372, 1078–1081 (2021).

Saha, S. K. et al. Scalable submicrometer additive manufacturing. Science 366, 105–109 (2019).

Hahn, V. et al. Rapid assembly of small materials building blocks (voxels) into large functional 3D metamaterials. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 1907795 (2020).

Wang, Y., Zhang, X., Li, Z., Gao, H. & Li, X. Achieving the theoretical limit of strength in shell-based carbon nanolattices. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2119536119 (2022).

Acknowledgements

Q.L. acknowledges financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52373048) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (226-2024-00020).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q.L. and L.Z. conceived the project. L.Z., J.T. and F.C. conducted the experiments and data analysis. H.L. performed the calculations. Q.L. and L.Z. wrote the manuscript. Q.L., Q.Z., and W.L. supervised the project. All authors discussed and commented on the manuscript. L.Z. and H.L. contributed equally to this work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zheng, L., Liang, H., Tang, J. et al. Micrometer-scale poly(ethylene glycol) with enhanced mechanical performance. Nat Commun 16, 4391 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-59742-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-59742-x