Abstract

Shigellosis is a gastrointestinal infection caused by species of Shigella. A large outbreak of Shigella flexneri serotype 2a occurred in Albuquerque, New Mexico between May 2021 and November 2023 that involved humans and non-human primates (NHP) from a local zoo. We analyzed the genomes of 202 New Mexican isolates as well as 15 closely related isolates from other states, and four from NHP. The outbreak was initially detected within men who have sex with men but then predominantly affected people experiencing homelessness. Nearly 70% of cases were hospitalized and there was one human death. The outbreak extended into Albuquerque’s BioPark Zoo, causing high morbidity and six deaths in NHPs. All isolates were multidrug-resistant, including towards fluoroquinolones, a first line treatment option which led to treatment failures in human and NHP populations. We show the circulation of the same S. flexneri strain in humans and NHPs, causing fatalities in both populations. This study demonstrates the threat of antimicrobial resistant organisms to vulnerable human and NHP populations and emphasizes the value of genomic surveillance within a One Health framework.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Shigellosis is a bacterial gastrointestinal infection caused by species of Shigella and characterized by bloody diarrhea, fever, and abdominal cramping, which may lead to extraintestinal complications such as sepsis, seizures, and reactive arthritis1. Shigellosis is caused by four species of Shigella: S. sonnei, S. flexneri, S. dysenteriae, and S. boydii, all of which are transmitted via the fecal-oral route. Shigella species have an low infectious dose of 10–100 cells2, and infection is common in young children, international travelers, men who have sex with men (MSM), and people experiencing homelessness (PEH)1,3. Within higher income settings such as Europe and the United States, many shigellosis cases have been attributed to transmission within the MSM community4,5,6. Additionally, there have been reports of recent outbreaks of shigellosis within PEH communities in several U.S. cities4,7,8,9.

While most shigellosis cases resolve naturally in short duration, antibiotic treatment may be recommended for severe cases and to limit the duration of infection and bacterial shedding1. The WHO first-line antimicrobial recommendation for shigellosis is ciprofloxacin, with pivmecillinam, ceftriaxone, or azithromycin as second line alternatives10. The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) similarly recommends ciprofloxacin, azithromycin or ceftriaxone as first-line options, with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole or ampicillin as alternatives11. Species of Shigella worldwide have acquired drug resistance to many first-line treatment options and genomic analyses have demonstrated the rapid emergence and spread of a fluoroquinolone resistant lineage for S. sonnei1,12,13. Many countries have recently reported Shigella strains designated extensively drug resistant (XDR), which display resistance to all empirical and alternative recommended antibiotics. In the U.S., prevalence of XDR Shigella rose from 0% in 2015 to 5% in 20223.

Here, we present the epidemiological and genomic characterization of a large shigellosis outbreak first identified within the Albuquerque, NM metro area caused by a multidrug-resistant (MDR) S. flexneri strain. This outbreak affected both PEH and MSM populations, and is notable because the same strain was also detected in the non-human primate (NHP) population at a local zoo, where it was associated with significant morbidity and mortality within that population.

Results

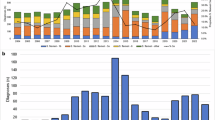

Between May 13, 2021, and November 19, 2023, NMDOH identified an outbreak of 202 Shigella flexneri serotype 2a cases in New Mexico (Fig. 1). NMDOH identified an initial cluster of four cases in May/June of 2021 among males reporting sexual activity with other men (MSM). However, by August 2021, cases spread into people experiencing homelessness (PEH). Over the course of the outbreak, half of the cases (n = 102, 50.5%) were classified as either PEH or PEH-adjacent and 11 cases (5.5%) reported MSM activity (Fig. 1). All those who were not MSM or PEH, but still in the outbreak were deemed ‘sporadic’ (n = 100, Fig. 1). Throughout the outbreak, the percentage of those who were PEH and sporadic remained roughly proportional. The outbreak also infected children attending daycare at several points (Fig. 1), but did not appear to cause prolonged transmission in daycare settings. Nearly 70% of cases were hospitalized (n = 141, 69.8%), with a median length of stay of four days (IQR 2.75–7.0 days). In contrast, only 40.8% of shigellosis cases not part of this outbreak in NM were hospitalized during the same period. Among PEH and PEH-adjacent cases, 78.6% (n = 81) were hospitalized, compared to 60% (n = 60) in sporadic and daycare cases. Table 1 summarizes epidemiological and clinical characteristics of cases.

NMDOH epidemiologists collaborated with City of Albuquerque environmental health officials, local nonprofits, and other stakeholders, which resulted in installing portable toilets and handwashing stations near large encampments of PEHs. This was critical since many public facilities had been closed due to the COVID-19 pandemic. An outreach point of contact (POC) with a local advocacy group was established to ensure services when PEHs were discharged from emergency rooms. Health Alert Network (HAN) messages were distributed to local providers informing them of significant developments in the outbreak.

In order to determine if this outbreak lineage was only localized to New Mexico, we pulled data from the NCBI Pathogen Detection database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pathogens) and identified closely related isolates to those found within the state. We determined our outbreak sublineage is part of the PDG000000004.4455/PDS000007367.963 SNP cluster defined by NCBI Pathogen Detection database and found 15 additional isolate genomes that were a part of the outbreak cluster but were not from NM. We pulled all sequencing data for a total of 220 samples, assembled the genomes, and mapped the reads against the reference S. flexneri 2a str. 301 to identify single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). Our genomic analyses revealed that the outbreak sublineage is highly clonal, with pairwise SNP differences for NM samples ranging from 0 to 32 SNPs (median 9, IQR 6–13) (Fig. 2B, Supplementary Fig. 1). All New Mexico samples had a minimum cgMLST allele difference ≤5 alleles to another sample, with 93% (196 of 211) of samples having one or fewer allele differences. The pairwise SNP distributions compared year on year are consistent with an introduction and establishment of transmission chains, and then subsequent divergence of isolates each year. The median increase in pairwise SNP distances each year increases between 3 and 4 SNPs (Supplementary Fig. 1), which is in line with the described mutation rate for Escherichia coli / Shigella spp. of 2–5.5 SNPs per year14,15.

A Time-scaled BEAST phylogeny of outbreak strains. The outbreak clade includes 221 isolates, 202 residents of New Mexico, 15 out of state residents, and 4 non-human primates. Nodes are colored by demographic status. The presence of AMR genes are indicated and clustered by drug class. B Minimum spanning tree of outbreak strains. The nodes are collapsed at five SNPs and the size of the circles are proportional to the number of strains within a given node. Nodes are colored by demographic status. Branch lengths correspond to the number of SNPs. C Transmission inference from BEAST. The size of the circles denotes the number of cases and lines between locations indicate inferred transmission events.

This outbreak sublineage harbors a set of triple point mutations (parC_S80I, gyrA_D87N, and gyrA_S83L) conferring resistance to fluoroquinolones (e.g., ciprofloxacin). These isolates also harbored a variety of other resistance genes (Fig. 2A), including the narrow spectrum beta-lactamase genes such as blaOXA-1 and blaTEM-1 which confer resistance to penicillins and first-generation cephalosporins, as well as sul2 and dfrA1 or dfrA5, conferring resistance to trimethoprim sulfamethoxazole. Despite the clonal nature of this outbreak, we noted that not all isolates harbored the same resistance profile. In particular, a ~84Kb plasmid harboring a number of resistance genes, including the blaTEM-1 gene, appears to be repeatedly lost across the outbreak (Fig. 2A). We did not detect macrolide resistance, mph(A) and erm(b), in isolates from NM (Figs. 2A and 3). Based on these analyses, NMDOH released a local Health Alert Network (HAN) notification on February 27, 2023 to all Albuquerque area providers alerting of this resistance pattern to ciprofloxacin.

To investigate the evolutionary history and spread of this outbreak sublineage, we created time-scaled phylogenetic trees. Our analyses indicate several precursor isolates to our New Mexico strains were first detected in Louisiana in 2019 and Texas in 2020 before being introduced into NM. We estimated the date of the most recent common ancestor (MRCA) for all NM isolates to August of 2020 [95% HDP April 2020–December 2020], suggesting this sublineage was circulating in NM prior to the first recognized case in May 2021. While the first cases in NM reported MSM activity, these cases were not directly linked to the other nine MSM cases later in the outbreak, which are largely interspersed with the other cases (Fig. 2). One notable exception is a well-supported clade (posterior probability, PP = 1) linking two MSM cases from NM in April/May 2022 to two MSM cases from NM and one case in New Jersey (collected within days of each other) in May 2023 (Fig. 2). The outbreak quickly moved into circulating predominantly within the PEH community starting in June 2021. While we do find instances of clusters of PEH cases, these isolates are also interspersed across the phylogeny. The sporadic cases are also interspersed throughout the phylogenetic tree, indicating a complex transmission network across different populations. In addition, there were five daycare cases, again distributed throughout the phylogeny. This sublineage has spread from NM to include six Colorado cases, two in Arizona, and single cases from New Jersey and Wyoming (Fig. 2, Supplementary Fig. 5), but does not appear to have caused similar outbreaks in these locations. We also contextualized this outbreak within the broader S. flexneri 2a diversity (Fig. 3, Supplementary Fig. 6). We find that our outbreak forms a distinct cluster, but sits within other closely related lineages that have been circulating in the U.S. and is not directly related to isolates circulating internationally (Fig. 3, Supplementary Fig. 6). Concerningly, many of these closely related strains harbor resistance genes towards macrolides or third-generation cephalosporins, which if transferred into the NM outbreak strain would confer an XDR phenotype. Overall, our phylogenetic analyses point to a complex transmission network that spans MSM, PEH, daycare populations, and other U.S. states.

To increase the resolution in our analyses, we sequenced the earliest viable NM isolate archived by NMDOH (PNUSAE076676, collected June 22, 2021) via Oxford Nanopore long-read technologies. This isolate was the sixth isolate collected in the NM outbreak and temporally 40 days from the first identified case on May 14, 2021. Combining the long and short-reads in a hybrid assembly yielded a fully closed genome, which we designated our internal outbreak reference strain. We mapped all isolates against the closed PNUSAE076676 genome and created phylogenies from the resulting alignments. Due to the clonal nature of the outbreak, some nodes in the phylogenies have low support and we have taken a conservative approach in making inferences based on these phylogenies (Supplementary Figs. 2–5). This limitation is likely to be a reality for many bacterial outbreaks where the rate of mutation accumulation is much slower than the transmission rate during the outbreak16.

In August of 2021, ten weeks after the first human cases, six out of eight Western lowland gorillas (Gorilla gorilla), four out of four siamangs (Hylobates syndactylus), three out of four Sumatran orangutans (Pongo abelii), and two out of nine chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) had clinical signs consistent with enteric disease. Primates exhibiting clinical signs were tested using the BioFire GI Panel. Fecal samples from an orangutan and gorilla, the second and third animals to show clinical signs, were submitted to Veterinary Diagnostic Services for bacterial culture and were sequenced at the New Mexico State Scientific Laboratory Division (SLD) in accordance with PulseNet protocol. The veterinary clinical management of this event is described in Bradford et al.17 A 48-year-old gorilla and three siamangs—a 32-year-old male, a 30-year-old female, and her two-month-old infant—died due to the Shigella infection. BioPark staff declared a quarantine after the first animals became symptomatic and worked closely with NMDOH to implement biosafety protocols, including disinfection, personal protective equipment (PPE) use, and cohorting of staff to prevent further transmission. No keeper staff reported illness or exposure consistent with Shigella infection. BioPark staff were encouraged to submit stool samples to test for asymptomatic carriage, but no samples were submitted. Importantly, all primates had ≥1 negative fecal culture for Shigella before their transfer to the BioPark, in keeping with standard zoo surveillance protocols. NMDOH, in collaboration with City of Albuquerque Environmental Health Department and the BioPark Zoo, re-interviewed available cases using a specialized shigellosis questionnaire focusing on areas around the zoo, water exposure from the Rio Grande flood drainage area, and produce-specific questions based on invoices from the zoo’s dietary ordering. No other samples were taken from other captive animals or wildlife as other animal species are not known to be common carriers of Shigella. The Biopark uses treated City of Albuquerque Water, which reported no known excess of fecal contamination. There was no other known environmental exposure, and no environmental sampling was conducted. Despite extensive investigation, the NMDOH team found no significant epidemiological connection. Almost a year after the initial outbreak, in July 2022, a 22-year-old chimpanzee began exhibiting clinical signs for enteric disease and tested positive for S. flexneri via BioFire GI panel and bacterial culture. The chimpanzee subsequently died. No other primate illnesses were reported at that time.

The remaining siamang of the troop (named Eerie) was transferred to an out of state zoological park (Zoo B) in 2021, after four negative cultures and a negative PCR test. Unfortunately, after Eerie’s introduction, a Shigella outbreak occurred in Zoo B, which killed an additional two siamangs. Eerie remained asymptomatic and was treated at Zoo B with amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (a penicillin) and ciprofloxacin (a fluoroquinolone) to eradicate carriage. No cultures were taken during the Zoo B outbreak. Upon Eerie’s transfer back to the Albuquerque BioPark Zoo, a fecal culture yielded Shigella. Unfortunately, despite treatment with appropriate antibiotics and an attempted transfaunation, he was euthanized in February 2024.

We obtained four genome sequences from infected NHP (a gorilla and an orangutan in 2021, chimpanzee in 2022, and Eerie the siamang November 2023 isolate). Our analysis places the NHP isolates directly within, and connected to, the human outbreak circulating in the Albuquerque metro area. (Fig. 2). These results suggest that this sublineage was circulating in the human population and was subsequently introduced into the NHP population within the BioPark. We used BEAST to estimate the most recent common ancestor (MRCA) for the four NHP genomes, obtaining a date of late March 2021 (95% HPD: January 2021 – June 2021). Importantly, this 95% HPD interval does not overlap with the earlier MRCA estimated for the New Mexico human isolates (August 2020; 95% HPD: April 2020 – December 2020), indicating an approximate 7-month gap between MRCA of the NM human lineage and the subsequent MRCA of the NHP lineage.

When comparing pairwise SNPs, we find that all NHP samples have their closest pair with a human sample, ranging from 0 to 11 SNPs. For instance, we found that both NHP samples from August 2021 are 0-1 SNPs away from a human samples from September 2021. Pairwise SNP distance between just the NHP samples ranged from 1 to 14 SNPs. Our phylogenetic analysis also suggests that Eerie the siamang was a long-term asymptomatic carrier. Eerie’s 2023 isolate falls directly within the outbreak lineage and his closest matches via pairwise SNPs (4 SNPs) from a 2021 NHP isolate. That same 2021 NHP isolate is 0 SNPs from several human isolates collected in September 2021, making Eerie just 4 SNPs from those September 2021 human cases as well. As expected, the isolates sampled from NHPs were multidrug resistant and shared the resistance profiles with the human isolates. All NHP isolates were resistant to fluoroquinolones due to the presence of the triple point mutations mentioned above and harbored the blaOXA-1 conferring resistance to penicillins. All isolates, except for the 2023 siamang strain, also harbored blaTEM-1.

A major question was whether the 2022 chimpanzee infection was due to asymptomatic carriage by either a zookeeper or another animal, or was the result of another separate introduction into the zoo. While it is likely that Eerie the siamang was a long-term carrier, this animal was not present at the time of the 2022 infection. All other NHPs had negative fecal cultures prior to arriving at the BioPark. The July 2022 chimpanzee sample is 14 SNPs different from the 2023 siamang sample, while 10-11 SNPs away from human samples, collected in late 2021 and in March 2022. The 2023 siamang was 4 SNPs different from three human samples collected in September 2021, November 2021 and January 2022. Due to the highly clonal population structure and resulting small number of SNPs, definitively answering this question is not trivial. When mapping to the external reference, our phylogenetic reconstruction does not place the 2022 chimpanzee isolate with any of the other NHP isolates (Fig. 2, Supplementary Figs. 2, 3). However, when mapping to our internal outbreak reference our phylogenies show the chimp 2022 isolate groups as a descendant of one of the 2021 NHP samples, albeit with low support (Supplementary Fig. 3). To gain more resolution, we performed additional long-read Nanopore sequencing on 28 isolates that spanned across the outbreak, including all four of the NHP samples. The long-read data was combined with short-read data to yield dramatically improved assemblies and resulted in complete or near-complete genomes for all 28 samples. To avoid potential reference bias, we utilized ska218, which is a k-mer based, reference free alignment tool. However, even with this dataset, the placement of the NHP samples is largely unresolved, essentially forming various branches stemming from a single “trunk” as one large polytomy in the phylogeny (Supplementary Fig. 7). However, the fact that in no phylogenetic analyses do we see all NHP samples grouping together does lend weight to the possibility of multiple introductions into the zoo.

Discussion

We have described a multidrug-resistant outbreak of S. flexneri 2a involving different human populations and remarkably, non-human primates. This was one of the largest identified outbreaks of shigellosis in New Mexico, and the first large outbreak involving a multidrug-resistant strain. While we have not detected macrolide or extended-spectrum beta-lactam (ESBL) resistance in this outbreak, the fact that many Shigella isolates circulating in the United States, including in New Mexico, harbor these resistance genes warrants vigilant surveillance.

Outbreak Response

This outbreak impacted various groups, such as MSM, PEH, daycare attendees, and the general public. The use of genomic similarity to determine the outbreak allowed us to identify cases – e.g., in daycares, which did not share epidemiologic similarities to other cases in this outbreak. These cases would have been missed if we were relying on traditional epidemiological data. Due to the significant impact and severity of this outbreak—which accounted for 39.3% of all shigellosis cases in New Mexico during the period and led to a 69.8% hospitalization rate—the New Mexico Department of Health (NMDOH) implemented aggressive measures, including establishing partnerships to ensure patient care for vulnerable groups, conducting thorough epidemiological investigations, and issuing local health alerts to inform clinical providers about the outbreak and the associated resistance patterns of the isolates. It is likely that the outbreak was much larger than reported cases, since not every Shigella case in NM has an associated isolate, which we used to define this outbreak. Additionally, care-seeking behavior among affected populations may vary. For example, the high hospitalization rate in PEH may stem from varied healthcare-seeking behavior, resulting in the detection of only severe cases.

The use of active public health surveillance through the FoodNet programs provided valuable data in a population notoriously difficult to interview4. Collaborating with local nonprofits and community partners allowed for the development of trust and ability to provide care to vulnerable populations. Our results spurred direct public health action as our data alerted local clinicians and veterinarians to not treat shigellosis cases with fluoroquinolones, but rather to use macrolide antibiotics. Without the genomics data, it is likely that both the connectedness of these cases and the AMR patterns would have gone unrecognized.

Shigella in Non-human Primates

This outbreak was particularly devastating in the NHP population within the Albuquerque BioPark Zoo. The BioPark participates in the Association of Zoos and Aquariums Species Survival Plan (SSP), which ensures genetic diversity among captive populations19. The loss of these endangered animals, particularly those of reproductive age, is a setback to achieving the goals of the SSP. Despite aggressive investigation by the Albuquerque BioPark and NMDOH, it is unclear how this S. flexneri outbreak strain was introduced into the zoo environment, which our phylogenies indicate may have occurred on multiple occasions. Of note, no zoo staff reported illness consistent with shigellosis during this time period. Although keepers were encouraged to submit specimens to SLD to test for asymptomatic carriage, no samples were received.

We considered alternative scenarios for how the introduction may have occurred, including a common-source exposure. Although theoretically possible, several lines of evidence reduce its likelihood. All BioPark primates had documented negative Shigella fecal cultures within 30 days of transfer and there had been no Shigella cases prior, indicating there was not a resident Shigella population in the BioPark primates. Further, municipal water testing conducted by the New Mexico Environment Department revealed no fecal contamination. Additionally, human cases in NM appeared 10 weeks before the first NHP cases and we find that there are 0-1 SNPs between the NHP samples from August 2021 and human samples from a month later in September 2021. Our molecular dating for these populations estimates the human NM samples have an MRCA seven months earlier than the NHP MRCA. As Shigella is known to persist on surfaces20, it may have been introduced, indirectly, when a zoo visitor threw a contaminated item into the enclosure. It may also have been introduced on cardboard tubes used as enrichment items, although this common zoo practice was discontinued as part of the initial response to the 2021 primate infections, and cannot explain the 2022 chimpanzee infection. Another possibility is that Shigella may have been introduced on an insect acting as a mechanical vector. Houseflies (Musca domestica) are able to carry infectious doses of Shigella species and have been associated with Shigella infections21,22. Insects acting as mechanical vectors could explain some of the genomic diversity among the NHP samples. Nonetheless, the human cases predating the NHP cases, 0-SNP identity between human and NHP isolates, and molecular-clock evidence, collectively support the scenario that spillover, either directly or indirectly (i.e. via contaminated objects), from infected humans remains the most parsimonious explanation for this outbreak.

Future Directions

Future research should investigate the prevalence of Shigella carriage in both wild and captive primate populations and identify factors that may trigger bacterial shedding in asymptomatic individuals. At the BioPark, quarterly PCR testing for Shigella has been conducted for all NHPs, with negative results except for the cases noted above. The factors contributing to shedding within this population remain unclear.

Shigella has been shown to circulate and transmit between human and NHP populations in captive settings23,24,25,26. Nizeyi et al.27 report that detection of Shigella among wild NHPs increases with human encroachment and cohabitation. Our report adds to this body of literature and emphasizes the severe impact this infection can cause, particularly as increasing rates of AMR impact treatment options. There is potential risk to both captive and wild primate populations as contact between humans and these animals increases - particularly in areas of high human shigellosis prevalence. The rising rates of AMR within Shigella, therefore, have direct implications for human and primate health in the future.

Methods

Epidemiologic information

We obtained shigellosis case data from the New Mexico Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Network (FoodNet), an active, population-based network which conducts surveillance for laboratory-confirmed infections, including species of Shigella. Our case definition was: a resident of New Mexico with a Shigella flexneri isolate genomically related (≤10 core-genome MLST (cgMLST) allele differences) to the outbreak strain. One patient had two separate positive samples collected <90 days apart, which was deemed not a separate incident case. Another patient had two samples collected >90 days apart and was deemed two separate incident cases. Four samples were collected in NM, but upon interview or medical record review were out of catchment (OOC) and excluded from case data collection, for a total of 202 cases. Eighty-two (40.6%) cases were interviewed by New Mexico Department of Health (NMDOH) staff and the remaining cases underwent medical record review for variables including outcome, hospitalization, length of stay, symptoms, onset date, MSM activity, and housing status. Cases were defined as a person experiencing homelessness (PEH) if either the interview or medical record reported homelessness at time of infection. We created a PEH-adjacent category for cases who reported being unstably housed (e.g., living in a motel) or whose occupation brought them into direct contact with PEH (e.g., shelter worker or a healthcare worker caring for an identified case). There was one case who was both MSM and PEH; based on epidemiologic and genomic evidence, this case was classified as PEH for the purpose of the study. We defined cases as “sporadic” when they did not fit either PEH, PEH-Adjacent, Daycare, or MSM categories, but were still related to the outbreak.

Sample collection and whole-genome sequencing

All Shigella cases are required by New Mexico Administrative Code 7.4.3.13 to be reported to the NMDOH, and associated specimens are sent to the State Scientific Laboratory Division (SLD), where whole-genome sequencing is performed as part of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)’s PulseNet program (Supplementary Data 2). Every clinical Shigella spp. isolate received or isolated at SLD is submitted for whole-genome sequencing with the following exception: multiple isolates from the same patient and isolation source if collected within 60 days of original submission date. Sequence assembly and outbreak cluster analysis were performed using BioNumerics 7.3 (Applied Maths NV, Sint-Martens-Latem, Belgium) with CDC PulseNet plugins. Following sequencing, genetically similar NM sequences or “clusters” are identified by comparing core genome MLST (cgMLST) of Shigella flexneri sequences in a local database with dates of collection in the last 60 days. For routine outbreak detection, clusters are defined as two or more sequences with ≤10 alleles difference and at least two of the sequences at ≤5 alleles. Due to the number of isolates and length of the outbreak, some samples were >10 alleles from some of the early isolates, but all samples were ≤10 (usually 0-1 alleles) from at least one sequence that was already part of the cluster.

Symptomatic primates were tested using a Biofire GI Panel (BioMerieux, Durham, NC, USA). Additional fecal specimens were submitted to Veterinary Diagnostic Services for bacterial culture. These grew Shigella flexneri, which was sequenced according to PulseNet protocol described above.

Additionally, we sequenced 28 isolates via Oxford Nanopore GridION on a R9.4.1 flowcell using the Rapid Barcoding Kit 96 V14 (SQK-RBK114.96). We chose one isolate that was the earliest viable NM isolate archived by NMDOH (PNUSAE076676, collected June 22, 2021) to be our internal reference strain for this outbreak.

Genomic and phylogenetic analyses

Illumina short-read data was assembled and annotated using the Bactopia pipeline28. We performed hybrid assemblies using Nanopore long-reads and Illumina short-read data via Bactopia using Unicycler v.0.5.029. This yielded a complete genome for our internal reference strain PNUSAE076676 (SRR15103314) which is accessioned under NCBI BioProject PRJNA1040311. AMRFinderPlus v.3.1130 was used to identify antimicrobial resistance genes.

We used the snippy v.4.6.0 (https://github.com/tseemann/snippy) pipeline with --mincov 8 and otherwise default parameters to map short-reads against reference sequences, call variants, and to generate consensus genome alignments. We mapped all samples against two reference genomes, the standard external reference Shigella flexneri 2a str. 301 (NCBI accessions NC_004337 and NC_004851), and to our internal outbreak reference strain PNUSAE076676. We masked the alignment to removed mobile elements and pathogenicity islands. SNPs were only considered if they fell within the chromosome. Unless otherwise stated, all statistics are reported for the alignment to the external reference Shigella flexneri 2a str. 301. The resulting SNP alignment consisted of 387 SNP sites as determined with snp-sites31.

We captured current transmission of closely related strains circulating in the U.S. by analyzing representative sequences from this outbreak in NM (n = 23) and 105 additional genomes that were <65 SNPs of the outbreak sequenced by CDC’s PulseNet program as part of the PDG000000004.4096/PDS000007367.803 SNP cluster as defined by the NCBI Pathogen Database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pathogens/) (Supplementary Data 2). The resulting variable site alignment was 630 sites. Additionally, we used the PathogenWatch32 database to pull 580 genomes that within 13 cgMLST alleles to our New Mexico isolates (Supplemental Data 3). We created a core-genome alignment of 4,125 genes using panaroo33. Reference free alignments were performed using ska218.

Maximum likelihood trees were calculated under the GTR + GAMMA model in IQ-Tree v.1.6.1234 with 10,000 ultrafast bootstraps and 10,000 bootstraps for the SH-like approximate likelihood ratio and visualized in ggtree35. BEAST v.1.10.436 was used with a strict molecular clock to estimate time-resolved phylogenies for both internal and external reference alignments, accounting for invariant sites. We ran five independent MCMC chains for 100,000,000 states, then combined the outputs by resampling every 5000 states with a burn-in of 10% of the chain length. All effective sample size (ESS) values exceeded 4,000, indicating excellent mixing. GrapeTree v.1.5.037 was used to create minimum-spanning trees, where we collapsed nodes at five SNPs. We excluded the four precursor strains sampled in the years prior in states outside of NM for the minimum-spanning trees.

Ethics

This activity (#23-086) was reviewed by the University of New Mexico Health Sciences Institutional Review Board and was determined to be “Not Human Research.” The bacterial genome sequencing data from non-human primate samples were obtained from NMDOH as part of routine surveillance activities. No new sampling or animal interventions were performed in this study, and no additional IACUC or ethical approvals were required for use of these existing data.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Sequencing data from this project has been deposited under NCBI BioProject PRJNA1040311. All short-read data can be accessed in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive using the accessions listed in the supplementary data tables (Supplementary Data 1–3). Alignments, results files, code, and full size figures are available at https://github.com/DommanLab/shigella-flex-NM.

Code availability

Code is available at: https://github.com/DommanLab/shigella-flex-NM.

References

Kotloff, K. L., Riddle, M. S., Platts-Mills, J. A., Pavlinac, P. & Zaidi, A. K. M. Shigellosis. Lancet 391, 801–812 (2018).

Puzari, M., Sharma, M. & Chetia, P. Emergence of antibiotic resistant Shigella species: A matter of concern. J. Infect. Public Health 11, 451–454 (2018).

CDC Health Alert Network. Increase in Extensively Drug-Resistant Shigellosis in the United States. https://emergency.cdc.gov/han/2023/han00486.asp (2023).

Hines, J. Z. et al. Heavy precipitation as a risk factor for shigellosis among homeless persons during an outbreak — Oregon, 2015–2016. J. Infect. 76, 280–285 (2018).

Charles, H. et al. Outbreak of sexually transmitted, extensively drug-resistant Shigella sonnei in the UK, 2021–22: a descriptive epidemiological study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 22, 1503–1510 (2022).

Thorley, K. et al. Emergence of extensively drug-resistant and multidrug-resistant Shigella flexneri serotype 2a associated with sexual transmission among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men, in England: a descriptive epidemiological study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 23, 732–739 (2023).

Tansarli, G. S. et al. Genomic reconstruction and directed interventions in a multidrug-resistant Shigellosis outbreak in Seattle, WA, USA: a genomic surveillance study. Lancet Infect. Dis. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00879-9 (2023).

Murti, M., Louie, K., Bigham, M. & Hoang, L. M. N. Outbreak of Shigellosis in a Homeless Shelter With Healthcare Worker Transmission—British Columbia, April 2015. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 36, 1372–1373 (2015).

Stefanovic, A. et al. Multidrug Resistant Shigella sonnei Bacteremia among Persons Experiencing Homelessness, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 29, 1668–1671 (2023).

Guidelines for the control of shigellosis, including epidemics due to Shigella dysenteriae type 1. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9241592330.

Shane, A. L. et al. 2017 Infectious Diseases Society of America Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Infectious Diarrhea. Clin. Infect. Dis. 65, e45–e80 (2017).

Chung The, H. & Baker, S. Out of Asia: the independent rise and global spread of fluoroquinolone-resistant Shigella. Microb. Genomics 4, e000171 (2018).

The, H. C. et al. Dissecting the molecular evolution of fluoroquinolone-resistant Shigella sonnei. Nat. Commun. 10, 1–13 (2019).

von Mentzer, A. et al. Identification of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) clades with long-term global distribution. Nat. Genet. 46, 1321–1326 (2014).

Chung The, H. et al. Evolutionary histories and antimicrobial resistance in Shigella flexneri and Shigella sonnei in Southeast Asia. Commun. Biol. 4, 353 (2021).

Duchêne, S. et al. Genome-scale rates of evolutionary change in bacteria. Microb. Genomics 2, e000094 (2016).

Bradford, C., Blossom, J., Reiten, K. & Ragsdale, J. Multispecies shigella flexneri outbreak in a zoological collection coinciding with a cluster in the local human population. J. Zoo. Wildl. Med. 54, 837–844 (2024).

Derelle, R. et al. Seamless, rapid, and accurate analyses of outbreak genomic data using split k-mer analysis. Genome Res 34, 1661–1673 (2024).

Species Survival Plan Programs | AZA. https://www.aza.org/species-survival-plan-programs.

Kramer, A., Schwebke, I. & Kampf, G. How long do nosocomial pathogens persist on inanimate surfaces? A systematic review. BMC Infect. Dis. 6, 130 (2006).

Chavasse, D. et al. Impact of fly control on childhood diarrhoea in Pakistan: community-randomised trial. Lancet 353, 22–25 (1999).

Levine, M. M., Cohen, D., Green, M., Levine, O. S. & Mintz, E. D. Fly control and shigellosis. Lancet 353, 1020 (1999).

Rewell, R. E. Outbreak of shigella schmitzii infection in men and apes. Lancet 253, 220–221 (1949).

Banish, L. D., Bush, M., Montali, R. J. & Sack, D. Shigellosis in a Zoological Collection of Primates. J. Zoo. Wildl. Med. 21, 302–309 (1990).

Lederer, I., Much, P., Allerberger, F., Voracek, T. & Vielgrader, H. Outbreak of shigellosis in the Vienna Zoo affecting human and non-human primates. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 9, 290–291 (2005).

Strahan, E. K. et al. Potentially Zoonotic Enteric Infections in Gorillas and Chimpanzees, Cameroon and Tanzania. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 30, 577–580 (2024).

Nizeyi, J. B. et al. Campylobacteriosis, salmonellosis, and shigellosis in free-ranging human-habituated mountain gorillas of Uganda. J. Wildl. Dis. 37, 239–244 (2001).

Petit, R. A. & Read, T. D. Bactopia: a Flexible Pipeline for Complete Analysis of Bacterial Genomes. mSystems 5, https://doi.org/10.1128/msystems.00190-20 (2020).

Wick, R. R., Judd, L. M., Gorrie, C. L. & Holt, K. E. Unicycler: Resolving bacterial genome assemblies from short and long sequencing reads. PLOS Computational Biol. 13, e1005595 (2017).

Feldgarden, M. et al. AMRFinderPlus and the Reference Gene Catalog facilitate examination of the genomic links among antimicrobial resistance, stress response, and virulence. Sci. Rep. 11, 12728 (2021).

Page, A. J. et al. SNP-sites: rapid efficient extraction of SNPs from multi- FASTA alignments. Microbial Genomics.

Pathogenwatch | A Global Platform for Genomic Surveillance. https://pathogen.watch/.

Tonkin-Hill, G. et al. Producing polished prokaryotic pangenomes with the Panaroo pipeline. Genome Biol. 21, 180 (2020).

Minh, B. Q. et al. IQ-TREE 2: New Models and Efficient Methods for Phylogenetic Inference in the Genomic Era. Mol. Biol. Evolution 37, 1530–1534 (2020).

Yu, G., Smith, D. K., Zhu, H., Guan, Y. & Lam, T. T.-Y. ggtree: an r package for visualization and annotation of phylogenetic trees with their covariates and other associated data. Methods Ecol. Evol. 8, 28–36 (2017).

Suchard, M. A. et al. Bayesian phylogenetic and phylodynamic data integration using BEAST 1.10. Virus Evolution 4, vey016 (2018).

Zhou, Z. et al. GrapeTree: visualization of core genomic relationships among 100,000 bacterial pathogens. Genome Res. 28, 1395–1404 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the UNM Center for Advanced Research Computing, supported in part by the National Science Foundation, for providing the high-performance computing resources used in this work. We would also like to thank all NMDOH, BioPark, Emerging Infections Program, nonprofit, and City of Albuquerque staff for their assistance in the investigation. This project is supported by an award from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health under parent grant number UL1TR001449 for a KL2TR001448 to D.D.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.S.D. participated in the outbreak investigation, data gathering and led the data analysis and manuscript writing. P.S.H. participated in data analysis and manuscript writing. K.E., C.B., T.H., J.H., F.L., K.P., And M.B. participated in outbreak investigation and data gathering. A.G.F., N.W., and D.M. performed laboratory experiments at S.L.D. and K.S. performed laboratory experiments at the University of New Mexico. S.L., C.S., and D.L.D. assisted with development of the presented ideas and implementation of the research. All authors discussed results and contributed to the final manuscript. D. D. conceptualized the direction of the manuscript, led data analysis, and supervised the project.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

After the manuscript had entered peer‑review, D.L.D. accepted a position at Illumina; this new employment commenced after all data collection and primary analyses were completed and did not influence the study design, interpretation of results, or the preparation of this manuscript. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Pieter-Jan Ceyssens, Karen Terio and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shrum Davis, S., Salazar-Hamm, P., Edge, K. et al. Multidrug-resistant Shigella flexneri outbreak affecting humans and non-human primates in New Mexico, USA. Nat Commun 16, 4680 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-59766-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-59766-3