Abstract

The solvent fluorination almost always improves electrochemical stability of electrolytes against both lithium anodes and high-voltage cathodes in lithium metal batteries. However, how exactly fluorination affects Li+-solvation and interphasial chemistries remains unclear, hindering rational design of electrolytes and interphases with both wide electrochemical stability window and fast ion transport kinetics that are required for energy-dense and fast-charging LMBs. Here we introduce the trifluoromethylation (-CF3) at one end of 1,2-dimethoxyethane and generate 1,1,1-trifluoro-2-(2-methoxyethoxy) ethane, which as a single solvent of electrolyte simultaneously meets energy-dense and fast-charging requirements when dissolving 2 M lithium bis(fluorosulfonyl)imide. Beside the electron-withdrawing effect of -CF3, we find that its lithiophobic nature against Li+ significantly alters the solvation structures, which favors the formation of anion-dominated clusters that lead to superior interphasial chemistries in layered structure and fast Li+ transport kinetics. In such electrolyte, lithium metal batteries constructed with 50-μm-thin Li||high-loading-NMC811 in both coin and pouch cell configurations achieve >400 cycles under fast-charging condition, and >100 cycles in 14-Ah-level industrial pouch cell with a high energy density over 510 Wh kg−1 at cell-level.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Replacing graphite anode with metallic lithium (Li0) is one of the most promising ways to approach the 500 Wh kg−1 battery energy density1,2,3,4,5,6. However, the practical implementation of such lithium metal batteries (LMBs), especially when coupled with high-voltage/high-capacity cathodes such as LiNi0.8Co0.1Mn0.1O2 (NCM811), is extremely challenging, hindered by both short cycling life caused by rapid capacity fading and charge/discharge rate limits imposed by poor interphasial kinetics and morphological concern. Both failure factors primarily stem from the fundamental instability between Li0 and electrolytes, whose uncontrollable parasitic reactions lead to continuously-growing SEIs and the consequent sluggish ion kinetics7,8. The composited effects of these issues is responsible for the fundamental irreversibility of LMBs.

As the ionic bridge between Li anode and high-voltage cathodes, the liquid electrolyte bears liability for these issues but simultaneously holds great key to resolve them9,10,11,12,13. Several electrolyte engineering approaches have been explored, including high concentration electrolytes (HCEs)14,15,16, locally HCEs diluted via non-coordinated co-solvents (LHCEs)17,18,19, additive tailoring20,21,22, artificial SEI or direct surface coating23,24, design of fluorinated solvents and single solvent-single-salt electrolytes25,26,27,28.

A practical high-energy density LMB requires several key parameters to be met simultaneously, including high-mass loading and high-cutoff voltage of a high capacity cathode, lean electrolyte, as well as limited Li metal inventory, which present unprecedented challenge to the electrolyte compositions. Thus, an ideal electrolyte must accommodate the reactivities of both electrodes while remaining inert to all other components it is exposed to and managing the deposition morphology of Li0. Various strategies have been attempted to approach the above metrics29,30,31,32,33,34, which effectively expand the lifespan of high-voltage LMBs if the cell is cycled at low charge/discharge rate (<0.5 C); however, a sudden deterioration always occurs once the current densities are above 0.5 C35,36,37,38. Fluorination of solvents has been proved as an effective avenue to improve reversibility of both Li metal and high-voltage cathodes in previous reports39,40,41,42, but always at the expense of the solvation power of the solvent, leading to insufficient solubility of the salt and sluggish Li+ transport in the bulk electrolyte43,44,45.

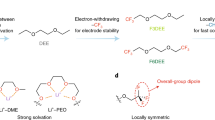

Here we introduced a new fluorination strategy by trifluoromethylating (-CF3) one end of 1,2-dimethoxyethane (DME). The new solvent molecule 1,1,1-Trifluoro-2-(2-methoxyethoxy) ethane (TMEE) was then used to form a single solvent electrolyte by dissolving 2 M lithium bis(fluorosulfonyl imide) (LiFSI). Compared with its homologs substituted with difluoromethyl (1,1-difluoro-2-(2-methoxyethoxy) ethane, DMEE) and nonfluorinated DME, TMEE-derived electrolyte exhibits superior electrochemical behaviors that comprehensively encompass long cycle life and high-rate capability. Unlike locally polar -CF2H group that can form weak coordination with Li+ via Li-F interaction, the fully fluorinated -CF3 group is completely lithiophobic, which alters electrolyte solvation structures together with its strong electron withdrawing effect, and leads to anion-dominated clusters. A unique SEI of distinctive bilayer structure is formed, consisting of a Li2O-rich outer-layer and an amorphous inner-layer, which maintains reversibility at both Li anode and high-voltage cathodes (Fig. 1a), suppresses Al corrosion, while allowing fast Li+ transport, which is otherwise unavailable for the DME- or DMEE-based electrolytes. Beside the high Li plating/stripping efficiency (>99.65%), the TMEE electrolyte also achieves >400 cycles in 50-μm-thin Li||high-loading-NMC811 coin/pouch cells (520 mAh) under fast-charging condition (1 C), and >90 cycles in 14-Ah-level Li||NCM811 industrial pouch cell with a high energy density over 500 Wh kg−1 at cell-level. A mechanism of how trifluoromethylation alters Li+-solvation sheath structure via lithiophobicity and electron-withdrawing effect is proposed, which sheds more light on the designing principle for the next generation electrolytes and interphases.

a Chemical structure design, electrostatic potential (ESP) of solvent molecules, and associated properties. b The CE test of different electrolytes via Aurbach method. c The long cycling performance of Li||Cu cells in different electrolytes under full plating/stripping conditions. d Evaluation of oxidation stability of different electrolytes via linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) of Li||Al cells at a scan rate of 0.5 mV s−1. e Cycling performance of Li||NCM811 coin cells under 0.3 C/0.5 C charge/discharge rate within the voltage range of 2.8–4.4 V.

Results

Design logic of fluorinated-TMEE solvent

To decrease the influence of steric hindrance to Li+-solvation, we introduced the trifluoromethylation (-CF3) and difluoromethylation (-CF2H) at one end of DME via facile nucleophilic reactions, respectively (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Figs. 1–4, termed as TMEE and DMEE hereafter, respectively), differing from previous works where almost always both ends of DME were substituted46,47,48,49. Note that monofluoromethylation (-CH2F) was not conducted in this work because the strong Li-F coordination will favor the generation of solvent-separated ion pairs in the electrolyte according to our previous report50, which is adverse to the general philosophy of encouraging cation-anion clustering in order to bring fluorine into interphases. The fluorination enables TMEE and DMEE to decrease their HOMO levels, and possess appropriate mass densities and boiling points (Supplementary Figs. 5-6), which are beneficial for electrolytes application. To reveal the impact of fluorination degree on resultant electrolyte properties, LiFSI was used as the common salt to prepare single-salt-single-solvent electrolytes due to superior Li metal compatibility compared with other salts (Supplementary Fig. 7)3,10. The relationship between ionic conductivity and salt concentration indicates that TMEE electrolyte promotes ion transport (ionic conductivity 4.3 mS cm−1) with 2 M LiFSI (Supplementary Fig. 8). Therefore, 2 M LiFSI was set as standard concentration for different solvents, which are termed as TMEE-2M, DMEE-2M, and DME-2M respectively.

To investigate Li metal compatibility of these electrolytes, we first evaluated the Li plating/striping efficiency in Li||Cu coin cells using Aurbach’s method51. The cell with TMEE-2M electrolyte delivers a high Coulombic efficiency (CE) of 99.65% at 0.5 mA cm−2 (Fig. 1b), which outperforms DMEE-2M (99.57%) and DME-2M (99.38%). The long cycling performance of Li||Cu cells with full plating/stripping was also tested to further confirm Li reversibility during repeated charge/discharge processes. Although at the current density of 1 mAh cm−2 DME-2M electrolyte achieves relatively high CE with good stability achieved for the initial 100 cycles, large CE fluctuation of the cell in was observed during the following cycles (Fig. 1c), indicating the dendritic growth of plated Li0 accompanied by local short circuit. By contrast, electrolytes based on fluorinated solvents show more stable cycling with high CEs and lower overpotentials (Supplementary Fig. 9), while TMEE-2M exhibits the best operation stability over 400 cycles. After increasing the applied current density to 2 mA cm−2 with the areal capacity of 2 mAh cm−2, the cell using TMEE-2M electrolyte can still operate stably over 160 cycles with high average CE and low overpotentials (Supplementary Figs. 10-11), indicating that the SEI originated not only preserve the non-dendritic morphology of Li0 but also allow fast Li+ kinetics. The oxidation stability of different electrolytes was evaluated via linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) in Li||Al coin cells. Unlike relatively low oxidation stability achieved in DME-2M and DMEE-2M electrolytes (~4.5 V), TMEE-2M shows considerably improved high-voltage tolerance with limited oxidation at 4.7 V (Fig. 1d), and this stability was further verified by the potentiostatic polarization tests (Supplementary Fig. 12a). Beside the inherent oxidation stability, TMEE stability against active cathode materials at high-voltage is also verified in Li||NCM811 coin cells, whose leakage currents at different applied voltages as revealed in Supplementary Fig. 12b remains the lowest from 4.3 to 4.7 V. By contrast, large leakage current densities with severe fluctuations are observed for the cells using DME-2M and DMEE-2M electrolytes, clearly ascribed to the catalytic decomposition of electrolytes by transition metal cores at cathode surface or the corrosion of Al current collectors.

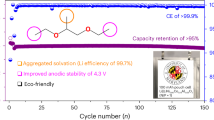

The superior stability of TMEE-2M against both Li0 and high-voltage cathode makes it a promising candidate to construct energy-dense LMBs, which were assembled using high-mass-loading (areal capacity: 3.5 mAh cm−2) NCM811 as cathode and 50 μm Li foils in coin cell configurations and tested between 2.8 and 4.4 V at 0.3/0.5 C charge/discharge rate (1 C = 3.5 mA cm−2). TMEE-2M enables a 90% capacity retention after 350 cycles with a high average CE of >99.7% and smaller polarization (Fig. 1e) than reference electrolytes (Supplementary Fig. 13a–b). By comparison, in DME-2M electrolyte the cell capacity decreases markedly and finally drops to 72% after 250 cycles. Possible reason for this rapid fading is the intensive Al corrosion and poor stability of DME-2M against oxidative decomposition at cathode, which has been verified by voltage floating test of Li||NCM811 cells (Supplementary Fig. 12b). DMEE-2M sustains similar capacity and cycling tendency with TMEE-2M within 100 cycles, but a fast capacity decay during overcharging induced cell failure (Supplementary Fig. 13c) is observed, which differs from DME-2M. Considering the high Li plating/stripping CEs achieved in Li||Cu coin cells (Fig. 1b, c), the instability against cathode side is suspected to cause this poor cycling performance. To reveal the exact cause, we assembled Li||Al coin cells with different electrolytes and analyzed the corrosion of Al foils under scanning electron microscope (SEM) and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) after holding Al at 4.8 V for 24 hours. The Al foil in TMEE-2M maintains a smooth morphology with negligible change when compared with the pristine Al, while porous surface structures with apparent corrosion are observed for the Al foils in both DMEE-2M and DME-2M (Supplementary Fig. 14). Further XPS data confirms that TMEE-2M encourages the formation of AlF3/Al2O3-dominated interphase to suppress Al corrosion (Supplementary Fig. 15), which is absent in both DMEE-2M and DME-2M.

Solvation structures altered by lithiophobicity and electron withdrawing effect

Both experimental characterizations and theoretical calculations were conducted to correlate the fluorination degree with Li+-solvation structures. The binding energies of different solvent molecules to Li+ were calculated (Fig. 2a), which is defined as the energy difference between the optimized binding state and the sum of each component. As a solvent with strong solvating power, the DME shows a high binding energy of −2.84 eV, forming the well-known solvation cages with working ions34. Difluoromethylation (-CF2H) slightly raises the binding energy to −2.96 eV. Noteworthy is that although the electron withdrawing effect by -CF2H group will decrease the electron cloud density around the oxygen in DMEE, the formation of weak Li-F interaction will compensate this weaking by coordinating with Li+, leading to overall elevated binding energy. In contrast, the TMEE solvent shows a much lower binding energy of −2.72 eV, indicating that the strong electron-withdrawing effect by trifluoromethylation (-CF3) significantly weakens the solvating power of the ether oxygen, while the lithiophobicity of -CF3 fails to compensate the loss as difluomethylation does. 19F NMR of the fluorine atoms in solvents directly quantifies the interaction between fluorine and Li+, where the changes in chemical shift in absence or presence of Li+ directly reflect the Li-F coordination interaction47,50. For DMEE solvent, 19F-chemical shift locates at −125.9 ppm, which experiences an up-field change of chemical shift by 0.51 ppm upon dissolving 2 M LiFSI (Fig. 2b), indicating the formation of Li-F interaction. In contrast, the 19F chemical shift in TMEE solvent locates at a higher value of -75.2 ppm, which results from the decreased electron cloud density around each fluorine nucleus. Interestingly, a down-field chemical shift change of 0.4 ppm is observed in TMEE-2M upon the dissolution of lithium salt, an entire reversal of what DMEE-2M displays. Such de-shielded effect of fluorine nuclei also varies with salt concentration (Supplementary Fig. 16), among which the largest chemical shift change occurs at 2 M, consistent with the variation of ionic conductivity. Given the shielded effect of fluorine nuclei upon the dissolution of LiFSI represents the Li-F coordination, this abnormal de-shielded effect can only represent a repulsion force between Li+ and fluorine atoms in TMEE, which is defined as the lithiophobicity in this work. The lithiophobicity in conjunction with strong electron withdrawing effect effectively decreases the solvating power of TMEE and regulate the Li+ solvation by allowing more participation of anions in its primary solvation shell, which is further verified by the decreased chemical shifts of 19F in FSI- anions (Fig. 2c) and the chemical environment change around Li+ after the dissolution of LiFSI (Supplementary Fig. 17).

a The binding energies of DME, DMEE, and TMEE solvents with Li+ cations. b 19F NMR spectra of the fluorine in DMEE/TMEE molecules before and after dissolving 2 M LiFSI. The CF3CD2OD is used for calibration. c The 19F NMR spectra of the fluorine in FSI- of different electrolytes. d The proton NMR spectra of different solvents before and after dissolving lithium salts. e Molecular dynamic (MD) simulation trajectory of TMEE-2M electrolyte and extracted solvation structures. Colors for different elements: H-white, Li-lime, C-cyan, N-blue, O-red, F-pink, and S-yellow. f Radial distribution functions TMEE-2M electrolyte calculated from the MD simulations. The Raman spectrum of DME-2M (g), DMEE (h) and TMEE-2M (i) electrolytes, respectively.

The weak interactions among Li+, solvents, and FSI- anions can also be revealed by 1H NMR spectra (Fig. 2d), where the protons in DME and DMEE solvents experience shielding by moving towards a lower chemical shift upon dissolution of LiFSI, while an exact reverse tendency is again observed for TMEE. In DME, relatively strong O···H hydrogen binding exists due to the relatively higher electron cloud density around the ether oxygen (Supplementary Fig. 18a). Upon lithium salt dissolution, the strong coordination between Li+ and oxygens will disrupt hydrogen bonding, and lead to shielded 1H nuclei in DME-2M electrolyte. A similar effect occurs in DMEE, suggesting that ether oxygens still maintain high electronegativity because -CF2H does not induce sufficient electron removal. In contrast, weakened and even negligible O···H hydrogen bonding exists in TMEE due to the significantly decreased electron density on ether oxygens by strong electron withdrawing effect of -CF3 (Supplementary Fig. 18b). After dissolving LiFSI, the coordination between Li+ and oxygens induces the electron shifting from hydrogen atoms, resulting in the de-shielded effect of 1H nuclei in TMEE-2M electrolyte. The proton NMR study on different solvents suggests that the strong electron-withdrawing effect also plays a significant role in tuning electrolyte solvation structures, although it is difficult for us to distinguish specific contributions when comparing with lithiophobicity.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations reveal more details of Li+-solvation structure in TMEE-2M electrolyte that is unavailable from experiments, in which the snapshot of TMEE-2M electrolyte denotes that Li+ coordinate with ether and sulfone oxygens from TMEE and FSI- to construct its primary solvation shell (Fig. 2e), which is verified by the representative peaks of Li-O(TMEE) and Li-O(FSI-) appearing around 2 Å in the radial distribution function (RDF, Fig. 2f). In addition, the higher coordination number (~3.9) of Li-O(FSI-) than that of Li-O(TMEE) (~1.8) also indicates the anion dominated solvation structures. Zoom-in the local part of MD snapshot reveals that ether oxygens distribute closer to Li+, while the -CF3 is repelled away from the primary solvation shell (red circle in Fig. 2e), which is also verified by the absence of Li-F(TMEE) around 2 Å in RDF (Fig. 2f). Instead, the snapshot of DME-2M (Supplementary Fig. 19a) places Li+ as surrounded mainly by the solvent molecules to form the primary solvation shell with negligible footprint of FSI- (Supplementary Fig. 19b), consistent with previously reported results6,50. For the DMEE-2M, the Li+ cations are coordinated by the oxygens from DMEE and FSI- (Supplementary Fig. 19c), while the peak intensity of Li-O(DMEE) is slightly higher than that of Li-O(FSI-) (Supplementary Fig. 19d). The larger coordination number of Li-O(DMEE) indicates that the content of solvent molecules is still higher than that of FSI- in the primary solvation sheath. From the extracted solvation cluster, we observed that the Li+ is close to the -CF2H group, which is probably ascribed to the weak Li-F(DMEE) interaction and contrary to -CF3 in TMEE-2M. The results of MD simulations are consistent with those of 19F NMR in Fig. 2b. Raman spectroscopy (Fig. 2g–i), whose signals within 700–800 cm−1 originate from the vibrations of the S-N-S bond in FSI- indicate solvent-separated ion pairs (SSIPs), contact ion pairs (CIPs), and ion aggregates (AGGs) at 720, 732, and 747 cm−1, respectively19. For DME-2M electrolyte, SSIPs are the dominant species at 64.5% (Fig. 2g), while CIPs and AGGs occupy 29.8% and 5.7%, respectively. Difluoromethylation (-CF2H) induces a large increase in CIPs and AGGs at the expense of SSIPs (Fig. 2i), yet its proportion still remains at a relatively high value of 20.9%. It is well-established that high SSIPs content often favors the decomposition of solvent molecules, sluggish Li+ desolvation, as well as the Al corrosion, which elucidates the short cycle life of cells in DME-2M and TMEE-2M electrolytes5,6,14,18. For TMEE-2M electrolyte, however, AGGs dominate the electrolyte speciations with a high proportion of 69.9% (Fig. 2i and Supplementary Fig. 20), while the SSIPs and CIPs decrease to 10.6% and 19.5%, respectively. Note that these proportions of solvation clusters are in accordance with the analysis from MD calculations (Supplementary Fig. 21), which further verified the anion-dominated solvation structures of TMEE-2M electrolytes. The anion-rich AGG structures favor the formation of an inorganic SEIs with robust physical properties to protect Li anode. Note that the non-zero existence of SSIPs in TMEE-2M electrolyte is necessary to maintain the ionic conductivity and high-rate performance for cells.

Deposited Li0 morphology in different electrolytes

The morphologies of deposited Li metal with a 5 mAh cm−2 (current density: 0.5 mA cm−2) areal capacity in different electrolytes were studied using SEM (Fig. 3a–d). In DME-2M electrolyte, a granular structure, featuring irregular Li0 particles with a diameter of ~10 μm and a deposition thickness of ~32 μm, is observed. The porous structure of Li0 particles increases its surface area and the opportunity of parasitic reactions. For the DMEE-2M electrolyte, the microstructure of platted Li is similar to that of DME-2M (Supplementary Fig. 22). In contrary, a smooth and compact Li0 morphology with a smaller thickness of 30 μm is observed for TMEE-2M electrolyte, indicating that this electrolyte encourages the homogeneous and dense Li0 deposition. To investigate the Li plating/stripping behaviors on the surface of Li foils, the cycling performance of Li||Li symmetrical cells with different electrolytes was measured at the current density of 2 mA cm−2 (capacity: 2 mAh cm−2). As shown in Fig. 3e, the TMEE-2M electrolyte enables the cell with a long cycling life over 500 h along with a low overpotential of 25 mV, while the cell with DME-2M only sustains 410 h of operation followed by failure due to short-circuit. The Li0 morphologies of Li||Li cells after 100 cycles were studied using SEM. Compared with the pristine Li foils (Fig. 3f), the cycled Li in DME-2M shows a rough and porous structure (Fig. 3g), which is in sharp contrast with the dense and uniform deposition in TMEE-2M (Fig. 3h).

Top and cross-sectional view SEM images of platted Li metal on Cu foil at 0.5 mA cm−2 with the capacity of 5 mAh cm−2 in DME-2M (a, b) and TMEE-2M (c, d) electrolytes. e The cycling performance of Li||Li symmetrical cells in different electrolytes at 2 mA cm−2 with the capacity of 2 mAh cm−2. SEM images of Li foils before (f) and after 100 plating/striping cycles in Li||Li symmetrical cells with DME-2M (g) and TMEE-2M (h) electrolytes. Investigation of the morphology and roughness of plated Li in DME-2M (i) and TMEE-2M (j) electrolytes via AFM. Monitoring the surface modulus of SEIs formed in DME-2M (k) and TMEE-2M (l) electrolytes.

The surface of deposited Li metal in different electrolytes was also characterized using the atomic force microscopic (AFM). A Li0 surface with a high roughness of 128 nm is observed in DME-2M electrolyte (Fig. 3i), which may induce the dendritic growth of Li0. In contrast, the surface of platted Li0 in TMEE-2M electrolyte shows a smooth and compact structure with an extremely low roughness of 12 nm (Fig. 3j), and this homogeneous deposition could inhibit the growth of Li dendrite and decrease the side reactions between active Li anode and electrolyte, thus improving the Li plating/stripping efficiency. The mechanical property of SEI formed on the Li0 surface was further investigated via AFM characterization. As revealed by the quantitative nanomechanical mapping-AFM images, the modulus distribution of the SEI formed in DME-2M is inhomogeneous (Fig. 3k), which potentially leads to the uneven Li0 deposition with dendrite growth. By contrast, the SEI formed in TMEE-2M shows a smooth and uniform distribution of modulus (Fig. 3l). This dense and even SEI could provide complete protection of Li metal with minimal exposure to electrolyte, thus decreasing the possibility of side reactions.

SEI nanostructures and Li metal protection mechanism

Cryogenic transmission electron microscopy (cryo-TEM) techniques enabled us to understand more about the composition and nanostructures of the formed SEIs in different electrolytes. The high resolution TEM (HRTEM) image of the formed SEI layer in TMEE-2M electrolyte is shown in Fig. 4a. A uniform and continuous SEI layer with a thickness of ~15 nm is observed on the surface of Li metal, showing smooth and dense passivation (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 23a). After magnifying the local interface, we found a distinctive and well-defined bilayer SEI from TMEE-2M electrolyte (Fig. 4b), featuring amorphous matrix in the inner layer (grey region) and continuous rod-like Li2O crystals with large size over 20 nm in the outer layer (highlighted with bright yellow region), which has been confirmed by the lattice spacings of 0.27 nm ({111} planes) and 0.23 nm ({220} planes) and corresponding fast Fourier transform (FFT) patterns (Fig. 4c, d). This bilayer SEI differs from the mosaic-like51, monolithic52, and LiF/Li2O double-layer14 SEI nanostructures in previous reports. Apart from the cryo-TEM, the Li2O as the dominant species in the SEI layer was also confirmed via XPS depth-profiling (Supplementary Fig. 24). In sharp contrast, the SEI formed from DME-2M electrolyte on Li metal shows a nonuniform and loose structure with high thickness of ~33 nm (Fig. 4e and Supplementary Fig. 23b), which is probably caused by uncontrolled parasitic reactions between active Li0 anode and electrolyte. When screening the local interfacial region (Fig. 4f), we found that an amorphous matrix dominates SEI with non-uniform, small-sized Li2O particles (3~8 nm) discontinuously dispersed (Fig. 4g–h). Note that the Li2O content in the SEI from DME-2M is only slightly lower than that of TMEE-2M electrolyte (Supplementary Fig. 24, Fig. 4b and f), which implies that the chemical composition of SEI may not be as important as the distribution of these chemical components in SEI as established earlier53.

The cryo-TEM images of the SEIs formed in TMEE-2M (a) and DME-2M (e) electrolytes. b, f Local magnification of the interface between the Li deposit and vacuum (white regions in a and e), highlighting the composition and nanostructure of the SEIs. Regions outlined with light yellow are Li2O nanocrystals. Representative HRTEM images (c, g) and corresponding fast Fourier transform (FFT) patterns (d, h) of the crystalline lattices within the SEI. Schematic illustration of the observed SEIs structures in TMEE-2M (i) and DME-2M (j) electrolytes, and corresponding Li metal protection mechanisms.

The Li metal protection mechanisms of different SEIs were proposed and summarized in Fig. 4i, j. For TMEE-2M electrolyte, although the formed SEI is very thin, the outer layer constructed by continuous large-sized Li2O particles is compact and robust enough to prevent the electrolyte permeation and subsequent Li corrosion (Fig. 4i). In addition, the thin and Li2O-rich SEI also promote the diffusion and migration of Li+ due to the low interfacial binding energy of Li+ on the boundaries of Li2O crystallites, favoring uniform Li-metal deposition. For DME-2M electrolyte, despite the significant presence of Li2O crystals in the formed SEI, the discrete and isolated particles often distribute separately in the whole region (Fig. 4j), which fails to construct an effective defense to prevent the electrolyte permeation across the porous section of the SEI.

Electrochemical performance of Li-metal batteries

Based on the chemical, morphological and architectural characteristics of SEIs, TMEE-2M electrolyte is expected to present more protective protections in high-voltage LMBs. The high-mass-loading Li||NCM811 coin cells containing different electrolytes were assembled and tested under various charge/discharge current densities in the voltage range of 2.8–4.4 V (Fig. 5a). At the charge/discharge current densities of 0.7, 1.75, 3.5, 7.0, 10.5, 17.5 mA cm−2, the TMEE-2M enables the cell with high capacities of 216.5, 207.5, 198.4, 186.2, 173.4, and 133 mAh g−1, respectively, while the cell in DME-2M only delivers capacities of 212.4, 200, 187.4, 171.5, 154.6, 114.2 mAh g−1 under identical conditions (Supplementary Fig. 25). The superior rate performance of Li||NCM811 cell is primarily ascribed from the fast Li+ transport kinetics across TMEE-derived SEI and is well aligned with the state-of-the-art literature44,50,54,55 of high-voltage LMBs with areal capacities >3 mAh cm−2. The long cycling performance is critical to the application of high-voltage LMBs, which is evaluated using Li(50 μm)||NCM811 coin cells at a charge rate of 0.3 C along with a high discharge rate of 2 C (1 C = 3.5 mA cm−2). TMEE-2M electrolyte enables a remarkable cycling performance of 80% capacity retention at the 500th cycle, along with minimal cell impedance increase (Supplementary Fig. 26). By contrast, DME-2M electrolyte only maintains 58% of the original capacity. The combination of high charge/discharge rate (e.g. >1 C), high-mass loading Li||NCM811 and high cutoff voltage (4.4 V) always presents the greatest challenge, and can hardly be realized in the most advanced HCEs36, LHCEs19, as well as weakly solvating electrolytes4,8,13,31. To test the superiority of TMEE, we cycled the Li||NCM811 cells at 1 C (3.5 mA cm−2), where TMEE-2M displays an impressive operational stability by maintaining a capacity retention of 88% after 450 cycles. This cycling stability surpasses the state-of-the-art electrolytes under such strict conditions (cutoff voltage: 4.4 V, high-mass loading: >3 mAh cm−2; thin Li foil: 50 μm; and charge/discharge rate: 1 C)4,5,6,7,8,9,13,19,35,38. In comparison, the DME-2M electrolyte only sustains the cell with a short working life of less than 100 cycles followed by accelerated capacity fading and rapid cell failure. Note that the operation stability of the DME-2M-cell cycled at 1 C charge/discharge rate is far inferior to that at 0.3/2 C, indicating that both the electrolyte/electrodes side reactions and dendritic Li growth will exacerbate at high charge/discharge current densities and finally results in the rapid deterioration of cells. Apart from NCM811, the TMEE-2M electrolyte also accommodates LiCoO2 (LCO) cathode, where a high-capacity retention of 97% after 400 cycles is achieved at 1 C charge/discharge rate (1 C = 2.5 mA cm−2, Fig. 5d). The TMEE-2M electrolyte also enables the LMB under the most severe condition of ‘anode free’, i.e, Cu||NCM811 cell, supporting 100 cycles at 1 C charge/discharge rate with a commercial high-loading cathode, far superior to DME-2M electrolyte (Supplementary Fig. 27).

a The rate performance of Li||NCM811 coin cells within the voltage of 2.8-4.4 V in different electrolytes. The areal capacity of the commercial cathode is 3.5 mAh cm−2. b The long cycling performance of Li||NCM811 coin cells at 0.3 C/2 C charge/discharge rate after one precycle at 0.1 C. c The long cycling performance of Li||NCM811 coin cells at 1 C in different electrolytes after one precycle at 0.1 C. d The cycling stability of Li | |LCO coin cells at 1 C in different electrolytes after one precycle at 0.1 C. e The high-temperature storage performance of Li | |NCM811 coin cells and subsequent specific discharge capacities (f) in different electrolyte. g The cycling stability of Li||NCM811 coin cells at 60 °C. h The long cycling performance of Li||NCM811 pouch cell (520-mAh) at 1 C charge/discharge rate after precycles at 0.1, 0.2, and 0.5 C. The optical image and its parameters of a 14-Ah level pouch cell (i) with the gravimetric energy density of 512 Wh kg−1 (by total weight at 0.1 C) and corresponding cycling performance at 0.1 C (j). All cells were measured at 30 °C unless specified.

To examine the anodic stability of different electrolytes on high-voltage cathode NMC, the morphology and CEIs on cycled NCM811 cathodes were analyzed via multiple characterization including SEM, HRTEM, and XPS. The cycled NCM811 recovered from TMEE-2M exhibits particle-like morphology similar to the pristine NMC811, while severe cracks are observed for the cathode material recovered from DME-2M electrolyte (Supplementary Fig. 28). The HRTEM images further reveal a uniform CEI layer with a thickness of 3.4 nm generated on the surface of the NCM811 after 100 cycles in TMEE-2M (Supplementary Fig. 29), while much thicker and nonuniform CEI layer with the thickness of 6.1 nm is observed for the cathode in DME-2M, which results from the parasitic reactions and the ineffectiveness of SEI, as verified by the XPS (Supplementary Fig. 30). Apparently, the reduced carbon content and the increased LiF content in the TMEE-derived SEI serves as the major player in supporting fast Li+-kinetics as well as suppressing parasitic reactions and Li0-dendrites.

The stability of high-voltage LMBs under high temperatures is also extremely challenging to the practical application due to the aggravated parasitic reactions that leads to fast capacity decay and severe self-discharge. To verify the efficacy of TMEE, the storage tests under high temperature (60 °C) was evaluated by monitoring the voltages of fully charged Li | |NCM811cells at 4.4 V. As revealed in Fig. 5e, the voltage of the cell with TMEE-2M electrolyte remains at 3.93 V after storing at 60 °C for 30 days, while the DME-2M only retains a voltage of 3.68 V under the same condition. After the high-temperature storage measurement, the cell in TMEE-2M still delivers a capacity of 142 mAh g−1, ca. 70% of the original capacity, while only 72 mAh g−1 was released by the cell with DME-2M electrolyte (Fig. 5f). Besides high-temperature storage, high-temperature cycling was also conducted. The TMME-2M electrolyte benefits from the moderately high boiling point of the TMEE solvent (105 °C), and the Li | |NCM811 cell based on it delivers stable cycling by maintaining a capacity retention of 70% after 150 cycles at 60 °C (Fig. 5g, Supplementary Fig. 31), while the DME-2M electrolyte only sustains 60 cycles operation life before cell failure. Besides the higher boiling point, the improved high-temperature cycling stability can be attributed to the robust SEI/CEI layers which prohibited the permeation of solvent molecules and subsequent parasitic reactions with both Li anode and high-voltage cathodes at elevated temperatures.

The outstanding electrochemical performance of TMEE-2M electrolyte in coin cells encourages us to further examine its application potential under practical conditions. A Li(50 μm)||NCM811 pouch cell with the total capacity of 520 mAh was assembled and tested at the voltage range of 2.8-4.4 V. At 1 C charge/discharge rate (1 C = 3.5 mA cm−2), the pouch cell in TMEE-2M electrolyte displays impressive cycling stability by maintaining 89.5% capacity after 400 cycle (Fig. 5h), while similar performance can only be achieved at low charge/discharge rates (e.g. 0.2/0.5 C) for the state-of-the-art electrolytes1,4,6,8,13,14. The TMEE-2M electrolyte also enables the 160-mAh-Li(50 μm)||LCO pouch cell with a capacity retention of 92.6% after 300 cycles (Supplementary Fig. 32). To achieve high energy density in LMBs, several key design parameters must be integrated into a single cell simultaneously, including high-mass loading, large cell capacity which matches both electrodes, high cutoff voltage, lean electrolyte, and limited active Li0. Aiming at this target, a 14-Ah level pouch cell was assembled with high-mass loading cathode (NCM811: 6 mAh cm−2 on single side), an ultra-thin Li foil (30 μm, corresponds to a negative/positive ratio of 0.5), and lean TMEE-2M electrolyte (1.2 g Ah−1). Benefiting from the optimized parameters, the pouch cell delivers a high gravimetric energy density of 512 Wh kg−1 based on the total weight of the cell and a volume energy density of 932 Wh L−1 under 0.1 C (Fig. 5i). More importantly, this pouch cell achieves a capacity retention of 90% after 100 cycles at 0.1 C (Fig. 5j), verifying the superiority of TMEE.

Fast Li-ion transport kinetics

Despite a much lower ionic conductivity when compared with DME-2M electrolyte (Supplementary Fig. 33), TMEE-2M exhibits an abnormally superior rate performance (Fig. 5a), which implies that the ion transport in the bulk electrolyte does not dictate the cell-level performance, while other factors might have contributed, such as Li+ transference number (tLi+), and interphasial factors such as Li+ desolvation and absorption of solvent molecules on electrode surfaces. The desolvation energies of the Li+(solvent)n complexes can be evaluated through the MD and DFT simulations (Fig. 6a), yielding −408 and −268 kJ mol−1 for Li+(DME)2.2 and Li+(TMEE)0.9 complexes (average coordination number from MD), respectively. Since charge-transfer impedance is dominated by Li+ desolvation process56, we deem this difference in desolvation energy for lower charge-transfer impedance in TMEE-2M electrolyte which directly benefits rate performance. The binding energies of different solvent molecules on Li metal surface were also assessed via DFT calculations. Comparing with the -CH3 of DME (Eb=0.09 eV), the -CF3 group shows a much higher binding energy (Eb = 0.2 eV) to Li0 (Fig. 6b). This stronger association between Li0 and TMEE may bring more Li+(solvent)n clusters to the surface of Li0 and accelerate the subsequent Li+-desolvation process. On the other hand, the higher lithium ion transference number (tLi+=0.81, Supplementary Fig. 34) enables a high Li+ conductivity (3.5 mS cm−1), which narrows the difference compared to that of DME-2M (tLi+=0.4, σLi+=4.5 mS cm−1). The desolvation of Li+ in different electrolytes was also investigated via the distribution of relaxation times (DRT)57 analysis in the Li||NCM811 cells (Fig. 6c). Not that the charge transfer resistance (Rct) locating at low frequency (10−1 < τ < 102), corresponds to the kinetics of Faradic processes at two electrodes related to the Li+ solvation and desolvation, while the intermediate frequency peak (10−3 < τ < 10−1) can be assigned to the impedance of SEI (RSEI). The Rct of the cells in TFEE-2M after 10 and 150 cycles is much smaller than those cells using DME-2M electrolyte, indicating rapid Li+ desolvation behavior in the former. After 150 charge/discharge cycles, a sharp peak corresponding to RSEI appears within the intermediate frequency for the cell in DME-2M, which is absent for the cell in TMEE-2M electrolyte, suggesting a thicker and uncontrollable SEI growth which is probably ascribed from the side reactions between active Li metal and electrolyte and accordance with the results of cryo-TEM (Fig. 4).

Discussion

In summary, we developed an ether solvent substituted by trifluoromethyl at one end. As a single solvent, it constructs a nonaqueous electrolyte that can form stable interphases on both Li0 and high-voltage cathode surfaces with fast Li-ion transport kinetics. We found that the lithiophobicity and the electron-withdrawing effect of trifluoromethyl alter the Li+-solvation structures that favors the formation of anion-derived clusters, which eventually leads to the formation of a high-quality bilayer-structured SEI consisting of a Li2O-rich outer layer and an amorphous matrix inner layer. Besides a superior high-temperature performance, the developed TMEE electrolyte also enables stable cycling of Li||NCM811 coin/pouch cells under fast charge/discharge rates and a high energy density of a 14-Ah pouch cell over 510 Wh kg−1 (based on total weight). This study unveils the impact of trifluoromethylation on electrolyte solvation engineering. It will inspire the design of more advanced electrolytes for fast-charging and long cycling energy-dense battery chemistries including but also beyond LMBs.

Methods

Materials

2,2,2-trifluoro-ethanol (98%), and 2-methoxyethanol (98%) were purchased from Adamas-beta®. 2,2-Difluoroethanol (Cat No. 1089787, Leyan, shanghai, China) was ordered from Leyan Co., Ltd. Dichloromethane (DCM, 99%), p-toluene sulfochloride, potassium hydroxide (KOH, 95%) N-methylpyrrolidone (NMP, 99%), anhydrous magnesium sulfate (MgSO4, 99%), 2,2,2-trifluoroethyl p-toluenesulfonate (99%), diethyl ether (99%), calcium hydride (CaH2, 99%), and lithium hydride (LiH, 99%), were purchased from Macklin Technology Co. Ltd (Shanghai, China). All chemicals were used without further purification unless specified. Lithium bis(fluorosulfonyl)imide (LiFSI, >99.9%), 1,2-dimethoxyethane (DME, >99.9%), LiNi0.8Co0.1Mn0.1O2 (NCM811, 3.5 mAh cm−2) and LiCoO2 (LCO, 2.5 mAh cm−2) cathode sheets were provided by Shenzhen CAPCHEM Technology Co. Ltd. The NCM811 cathode sheets with the areal capacity of 6.0 mAh cm−2 and 30-μm-Li foils for 14-Ah pouch cell were provided by Zhejiang Funlithium New Energy Technology Co., Ltd. The Celgard 2400 (20 μm thick) separator was purchased from Celgard and used in all coin and pouch cells. Thick (400 μm) and thin Li foils (50 μm) were purchased from China Energy Lithium Co. Ltd (Tianjin, China). The thin Cu current collectors (12 μm) and other battery materials were all purchased from Canrd Technology Co. Ltd.

Synthesis

1,1,1-Trifluoro-2-(2-methoxyethoxy) ethane (TMEE) was synthesized using similar approach as our previous report6. To a 1000-mL round-bottomed flask, 2-methoxyethanol (76 g, 1 mol), 2,2,2-trifluoroethyl p-toluenesulfonate (381 g, 1.5 mol), and NMP (200 mL) were added, and the solution was cooled to 0 °C followed by stirring for half an hour. Then, 250 mL KOH aqueous solution (45 wt%) was added dropwise, followed by heating to 50 °C for 5 hours. Afterwards, the temperature was elevated to 70 °C to remove residual tosylate. After cooling down to room temperature, the while precipitate was removed by filtration, while the residual solution was extracted with ethyl ether, followed by washing three times with deionized water. The obtained organic solution was dried by anhydrous MgSO4, CaH2, and LiH, respectively. After removing solvent via rotary evaporation, the product was obtained after atmospheric distillation (Boiling point: 100 ~ 105 °C). Yield: 84%. 1H NMR and 19F NMR were shown in Supplementary Figs. 2–3c.

For difluoromethyl (1,1-difluoro-2-(2-methoxyethoxy) ethane (DMEE), a 1-L round-bottom flask was added a mixture of p-toluenesulfonyl chloride (TSCl, 1.05 mol) and 2,2-difluoroethanol (1 mol) in dichloromethane (DCM, 500 mL). Triethylamine (Et3N, 1.05 mol) was added dropwise under ice-bath cooling with vigorous stirring. The reaction was maintained at 0-5 °C for 1 h, then allowed to warm to room temperature and stirred for 24 h. The organic phase was washed with deionized water (3 × 300 mL), dried over anhydrous MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure to afford 2,2-difluoroethyl p-toluenesulfonate as pale orange liquid (~98% crude yield). The obtained sulfonate ester (1 mol) was dissolved in N-methylpyrrolidone (NMP, 200 mL), followed by addition of ethylene glycol monomethyl ether (1 mol). The solution was cooled to 0 °C in an ice-water bath, then 45 wt% aqueous KOH solution (300 mL) was added dropwise while maintaining temperature below 5 °C. After complete addition, the mixture was stirred for 1 h at 0 °C and then heated to 70 °C for 6 h. The cooled reaction mixture was diluted with deionized water (500 mL) and extracted with diethyl ether (3 × 200 mL). The combined organic layers were washed with saturated brine (3 × 150 mL), dried over MgSO4, and concentrated under vacuum. The crude product was purified by atmospheric distillation, collecting the fraction at 140–150 °C to yield the target compound. Yield: 60%. 1H NMR and 19F NMR were shown in Supplementary Figs. 2–3c.

Electrolytes

LiFSI (3.74 g) were dissolved into 10 mL solvents (e.g., DME, DMEE, and TMEE) at room temperature to directly obtain corresponding DME-2M, DMEE-2M, and TMEE-2M electrolytes with the salt concentration of 2 M, respectively. All the electrolytes were prepared and stored in an argon-filled glovebox (oxygen <0.01 ppm, water <0.01 ppm).

Characterizations

The densities of solvents were tested using a DensitoPro densimeter (Mettler Toledo) at 30 °C. The nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) (400 MHz, Bruker) was used to characterized chemical structures of the solvents and corresponding electrolytes. The deuterated trifluoroethanol (CF3CD2OD) was selected as the reference sample for the calibration, and the 19F NMR of fluorinated electrolytes was measured using coaxial nuclear magnetic tubes. All the NMR measurements were performed with a decoupling mode. The morphology of deposited Li metal was characterized using a field emission scanning electron microscope (SEM, TASCAM MIRA3). To avoid contact with air, the Li samples on Cu foils were prepared in the glove box and transferred using a seal transfer bin with the protection of Ar. The ionic conductivities of electrolytes were measured via a conductivity meter (Mettler Toledo) at different temperatures. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was obtained through an AXIS-ULTRA DLD spectrometer (Shimazu-Kratos). The XPS spectra are calibrated by using C1s (284.8 eV) as the reference peak. The etching depth for the sputtering is 10 nm/min. The SEI characterization of Li metal was performed using an aberration-corrected FEI Krios G3i microscope with Gatan Continuum (1069) and Falcon 3 direct detection device. The automatic liquid nitrogen perfusion system can automatically maintain the low temperature of the sample chamber and the lens barrel for several days to ensure high imaging stability. The resolution limit of the microscope can reach ~0.14 nm. The samples in different electrolytes were prepared by electrochemically plating Li metal on the copper grid (400 mesh) at 0.25 mA cm−2 for half an hour using coin cells. The extracted Li metal samples were immediately frozen in an improved argon-filled glove box and then transferred to the Cryo-TEM chamber. The cryo-TEM images were acquired with an electron dosage of 120 e Å−2 and the Cryo-EELS are acquired using 11 pA current with 0.1 s dwell time at each pixel for core edges.

Theoretical calculations

The molecular geometries for the ground states were optimized by density functional theory (DFT) at the B3LYP/6-311++G (d, p) level, and then the orbital levels, and electrostatic potentials (ESPs) of the solvent molecules were evaluated using Gaussian 09 package. Binding energies of the Li+(Solvent)x complexes were calculated after geometry optimizations, in which the full complexes were optimized with and without Li+, representing their separation at an infinite distance. The desolvation energies were calculated as: Ed = ELi+(solvent)x–(ELi++Ex(solvent))+EBSSE. The ELi+(solvent)x, ELi+, Ex(solvent), EBSSE, are the energies of Li+(solvent)x complex, Li+ cation, solvent molecules, and basis set superposition error. The calculations of adsorption energies were performed with the Vienna ab initio Simulation Package (VASP) within the frame of DFT. The exchange-correlation interactions of electrons were described via the generalized gradient approximation (GGA) with PBE functional, and the projector augmented wave (PAW) method was used to describe the interactions of electron and ion. Additionally, the DFT-D3 method was used to account for the long-range van der Waals forces present within the system. The Monkhorst-Pack scheme was used for the integration in the irreducible Brillouin zone. The kinetic energy cut-off of 450 eV was chosen for the plane wave expansion. The slab of 8 Li layers which contains 128 atoms (the bottom 4 layer frozen during optimization) was constructed to model the BCC Li (001) surface based on an orthogonal supercell of Li (R3̅m). In all cases, a vacuum region of 15 Ã in the direction perpendicular to the Li surface was kept. The total energy was converged within 10-5 eV per formula unit. The final forces on all ions are less than 0.02/Å. The adsorption ability of different molecules to Li metal were calculated using binding energy (Eb) according to previous literature58. Eb is defined as the difference between the total energy of the molecule-adsorbed system (Etotal) and the energy sum of the isolated solvent molecule (DME or TMEE) and a clean Li substrate: Eb=Emolecule+Esubstrate-Etotal, where a larger value indicates greater adsorbing strength. The intention of the calculation is to investigate the different adsorption ability of -CH3 and -CF3 groups to Li metal, therefore, the linear configurations of DME and TMEE were applied for the calculation.

All-atom molecular dynamics (MD) simulations: MD simulations were performed using the Gromacs2022.4 package. The optimized potentials for a liquid simulations all-atom (OPLS-AA) force field were adopted to describe the interatomic interactions of the electrolyte system. Partial atomic charges were optimized by DFT. According to the molar ratio in experiments, 500 LiFSI with 2250 DME molecules for DME-2M, 500LiFSI with 1670 DMEE, and 500 LiFSI with 1670 TMEE molecules were randomly put into the cubic simulation box by using gmx insert-molecules software. The steepest descent method was applied to minimize the energy of the system. Then, 2 cycles of quench-annealing dynamics between 298 K and 698 K were conducted to eliminate the persistence of meta-stable states. After that, a 50 ns MD simulation in the isothermal-isobaric ensemble was conducted at the temperature of 298 K and the pressure of 1 bar, and the last 20 ns MD trajectory was used for analysis. During simulations, the temperature was controlled by the Nosé-Hoover thermostat algorithm with a coupling constant of 0.2 ps, and the pressure was controlled by the Parrinello-Rahman algorithm. The LINCS algorithm was employed for bond constraints. The long-range electrostatic interactions were treated with the Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) method. The non-bonded potential truncation was performed with a cut-off radius of 12 Å for the Lennard-Jones potential. Periodic boundary conditions were used in all three directions. The time step was set at 1 fs. The visualization and analysis of simulation results were performed using VMD and internal codes. The solvation clusters statistics of different electrolytes were calculated using the MDAnalysis Python package48.

Electrochemical measurements

All battery components used in this work were purchased from Shenzhen Kejing Technology Co. Ltd., and all electrochemical tests were carried out using 2032-type coin cells unless otherwise specified. All cells were fabricated in an argon-filled glovebox (H2O < 0.1 ppm, O2 < 0.1 ppm), and one layer of Celgard 2400 was used as a separator for all batteries. The tests of Li+ transference number (LTN) and linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) were carried out on a Solartron electrochemical workstation (1260 A). The cycling tests for coin cells were carried out on NEWARE Battery Test System (CT-4008T-5V50mA-164, Shenzhen, China). For the LTN measurements, a 10-mV constant voltage bias was applied to the Li||Li cells. LSV tests were conducted over a voltage range from open circuit to 6 V. For Li||Cu cell cycling tests, five pre-cycles between 0 and 1 V were initialized to minimize the side reaction between the Li and Cu electrode surface, and then cycling was done by depositing Li onto the Cu electrode; the Li was then stripped to 1 V at different current densities. The average CE was calculated by dividing the total stripping capacity by the total deposition capacity after the formation cycle. For the Aurbach’s CE test, a standard protocol was followed: (1) performing one formation cycle with Li metal deposition of 5 mAh cm−2 on Cu with 0.5 mA cm−2 and stripping Li to 1 V; (2) deposited 5 mAh cm−2 Li on Cu with 0.5 mA cm−2 as a Li reservoir; (3) repeatedly stripping/platting Li 1 mAh cm−2 Li with 0.5 mA cm−2 for 10 cycles; 4) stripping all Li to 1 V. The 400 µm Li foils were used for the measurements of LiCu, Li||Al coin cells (including LSV, LTN). The Li||NCM811 cells (cathode capacity: 3.5 mAh cm−2, Li foil: 50 µm) with different electrolytes were cycled between 2.8 and 4.4 V at different rates after the first two activation cycles at 0.35 mA cm−2. The NCM811 cathode contains 97 wt% active materials, 1 wt% Super P, and 2 wt% PVDF binders. For the 520-mAh level Li||NCM811 pouch cells, two cathode sheets (double side, 5.0 × 7.4 cm2) with a high areal capacity of 3.5 mAh cm−2 were selected to pair with three 50-μm-thick Li foils. The anode-free cell was assembled by paring NCM811 cathode with Cu foil and tested with the current density of 3.5 mA cm−2 at 30 °C. The electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) of Li||NCM811cells was performed from 10 MHz to 10 mHz at an amplitude of 10 mV using a Solartron 1287 electrochemical workstation. Before carrying out the EIS measurements at 30 °C, cells were discharged to 3.9 V. The specific current and specific capacity refer to the mass of the active material in the positive electrode. 30 µL of different electrolytes were added in each coin cell for electrochemical measurements. All cells were prepared in an argon-filled glovebox (H2O < 0.1 ppm, O2 < 0.1 ppm) and tested in constant-temperature chambers.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data that supports the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Jie, Y. et al. Towards long-life 500 Wh kg−1 lithium metal pouch cells via compact ion-pair aggregate electrolytes. Nat. Energy 9, 987–998 (2024).

Jie, Y. et al. Progress and perspectives on the development of pouch-type lithium metal batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 136, e202307802 (2024).

Hobold, G. M. et al. Moving beyond 99.9% Coulombic efficiency for lithium anodes in liquid electrolytes. Nat. Energy 6, 951–960 (2021).

Ma, B. et al. Molecular-docking electrolytes enable high-voltage lithium battery chemistries. Nat. Chem. 16, 1427–1435 (2024).

Sun, Y. et al. Molecular engineering toward robust solid electrolyte interphase for lithium metal batteries. Adv. Mater. 36, 2311687 (2024).

Zhang, G. et al. Molecular design of competitive solvation electrolytes for practical high-energy and long-cycling lithium-metal batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2312413 (2023).

Huo, S. et al. Anode-free Li metal batteries: Feasibility analysis and practical strategy. Adv. Mater. 36, 2411757 (2024).

Li, A.-M. et al. Methylation enables the use of fluorine-free ether electrolytes in high-voltage lithium metal batteries. Nat. Chem. 16, 922–929 (2024).

Li, T. et al. Stable anion-derived solid electrolyte interphase in lithium metal batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 22683–22687 (2021).

Yu, W. et al. Electrochemical formation of bis(fluorosulfonyl)imide-derived solid-electrolyte interphase at Li-metal potential. Nat. Chem. 17, 246–255 (2025).

Zhao, Y. et al. Electrolyte engineering via ether solvent fluorination for developing stable non-aqueous lithium metal batteries. Nat. Commun. 14, 299 (2023).

Kim, S. C. et al. High-entropy electrolytes for practical lithium metal batteries. Nat. Energy 8, 814–826 (2023).

Kwon, H. et al. Borate-pyran lean electrolyte-based Li-metal batteries with minimal Li corrosion. Nat. Energy 9, 57–69 (2024).

Li, G.-X. et al. Enhancing lithium-metal battery longevity through minimized coordinating diluent. Nat. Energy 9, 817–827 (2024).

Liu, Q. et al. An inorganic-dominate molecular diluent enables safe localized high concentration electrolyte for high-voltage lithium-metal batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2209725 (2023).

He, R. et al. Active diluent-anion synergy strategy regulating nonflammable electrolytes for high-efficiency Li metal batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202317176 (2024).

Zhu, Y. et al. Multifunctional electrolyte additives for better metal batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2301964 (2024).

Bergstrom, H. K. et al. Ion transport in (localized) high concentration electrolytes for Li-based batteries. ACS Energy Lett. 9, 373–380 (2024).

Efaw, C. M. et al. Localized high-concentration electrolytes get more localized through micelle-like structures. Nat. Mater. 22, 1531–1539 (2023).

Zhang, H. et al. Electrolyte additives for lithium metal anodes and rechargeable lithium metal batteries: progress and perspectives. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 15002–15027 (2018).

Wen, Z. et al. Dual-salt electrolyte additive enables high moisture tolerance and favorable electric double layer for lithium metal battery. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202314876 (2024).

Fu, C. et al. A non-expendable leveler as electrolyte additive enabling homogenous lithium deposition. Adv. Mater. 7, 2305470 (2023).

Chen, H. et al. Heterogeneous structure design for stable Li/Na metal batteries: Progress and prospects. eScience 5, 100281 (2024).

Wu, X. et al. Lithiophilic covalent organic framework as anode coating for high-performance lithium metal batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202319355 (2024).

Huang, Y. et al. Eco-friendly electrolytes via a robust bond design for high-energy Li metal batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 15, 4349 (2022).

Li, Y. et al. Single-solvent-based electrolyte enabling a high-voltage lithium-metal battery with long cycle life. Adv. Energy Mater. 13, 2300918 (2023).

Piao, Z. et al. A semisolvated sole-solvent electrolyte for high-voltage lithium metal batteries. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 24260–24271 (2023).

Zhao, Y. et al. Fluorinated ether electrolyte with controlled solvation structure for high voltage lithium metal batteries. Nat. Commun. 13, 2575 (2022).

Deng, L. et al. Asymmetrically-fluorinated electrolyte molecule design for simultaneous achieving good solvation and high inertness to enable stable lithium metal batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 14, 2303652 (2023).

Chen, L. et al. Dynamic shielding of electrified interface enables high-voltage lithium batteries. Chem 10, 1–17 (2024).

Chen, S. et al. Unveiling the critical role of ion coordination configuration of ether electrolytes for high voltage lithium metal batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202219310 (2023).

Fang, M. et al. A temperature-dependent solvating electrolyte for wide-temperature and fast-charging lithium metal batteries. Joule 8, 91–103 (2024).

Meng, Y. S., Srinivasan, V. & Xu, K. Designing better electrolytes. Science 378, 1065 (2022).

Xu, K. Electrolytes, Interfaces and Interphases: Fundamentals and Applications in Batteries, RSC Press (2023).

Zhang, J. Weakly solvating cyclic ether electrolyte for high-voltage lithium metal batteries. ACS Energy Lett. 8, 1752–1761 (2023).

Li, Z. et al. Non-polar ether-based electrolyte solutions for stable high-voltage non-aqueous lithium metal batteries. Nat. Commun. 14, 868 (2023).

Moon, J. et al. Non-fluorinated non-solvating cosolvent enabling superior performance of lithium metal negative electrode battery. Nat. Commun. 13, 4538 (2023).

Hai, F. et al. A low-cost, fluorine-free localized highly concentrated electrolyte toward ultra-high loading lithium metal batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 14, 2304253 (2024).

Amanchukwu, C. V. et al. A new class of ionically conducting fluorinated ether electrolytes with high electrochemical stability. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 7393–7403 (2020).

Lin, Y. et al. Impact of the fluorination degree of ether-based electrolyte solvents on Li-metal battery performance. J. Mater. Chem. A 12, 2986 (2024).

Zhang, G. et al. A nonflammable electrolyte for high-voltage lithium metal batteries. ACS Energy Lett. 8, 2868–2877 (2023).

Li, Z. et al. Critical review of fluorinated electrolytes for high-performance lithium metal batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2300502 (2023).

Zhang, H. et al. Cyclopentylmethyl ether, a non-fluorinated, weakly solvating and wide temperature solvent for high-performance lithium metal battery. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 135, e202300771 (2023).

Xia, Y. et al. Designing an asymmetric ether-like lithium salt to enable fast-cycling high-energy lithium metal batteries. Nat. Energy 8, 934–945 (2023).

Kim, S. C. et al. Solvation-property relationship of lithium-sulphur battery electrolytes. Nat. Commun. 15, 1268 (2024).

Wu, L.-Q. et al. Unveiling the role of fluorination in xexacyclic coordinated ether electrolytes for high-voltage lithium metal batteries. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 5964–5976 (2024).

Yu, Z. et al. Molecular design for electrolyte solvents enabling energy-dense and long-cycling lithium metal batteries. Nat. Energy 5, 526–533 (2020).

Yu, Z. et al. Rational solvent molecule tuning for high performance lithium metal battery electrolytes. Nat. Energy 7, 94–106 (2022).

Wang, H. et al. Dual-solvent Li-ion solvation enables high-performance Li-metal batteries. Adv. Mater. 33, 2008619 (2021).

Zhang, G. et al. A monofluoride ether-based electrolyte solution for fast-charging and low temperature non-aqueous lithium metal batteries. Nat. Commun. 14, 1081 (2023).

Peled, E., Golodnitsky, D. & Ardel, G. Advanced model for solid electrolyte interphase electrodes in liquid and polymer electrolytes. J. Electrochem. Soc. 144, L208 (1997).

Cao, X. et al. Monolithic solid-electrolyte interphases formed in fluorinated orthoformate-based electrolytes minimize Li depletion and pulverization. Nat. Energy 4, 796–805 (2019).

Wang, C., Meng, Y. S. & Xu, K. Fluorinating Interphases. J. Electrochem. Soc. 166, A5184–A5186 (2019).

Wu, Z. et al. Growing single-crystalline seeds on lithiophobic substrates to enable fast-charging lithium-metal batteries. Nat. Energy 8, 340–350 (2023).

Rahman, M. M. et al. An inorganic-rich but LiF-free interphase for fast charging and long cycle life lithium metal batteries. Nat. Commun. 14, 8414 (2023).

Xu, K. Charge-Transfer” process at graphite/electrolyte interface and the solvation sheath structure of Li+ in nonaqueous electrolytes. J. Electrochem. Soc. 154, A162–A167 (2007).

Maradesa, A. et al. Advancing electrochemical impedance analysis through innovations in the distribution of relaxation times method. Joule 8, 1958–1981 (2024).

Xue, W. et al. FSI-inspired solvent and full “fluorosulfonyl” electrolyte for 4 V class lithium-metal batteries. Environ. Sci. 13, 212–220 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (22305115 and 22371116), Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (2023A1515010686), Shenzhen Science and Technology Program (JCYJ20220818100218040, JCYJ20220530114408018, JSGG20220831095800001, SGDX20240115110505010), Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2023A1515010985). We also thank K. Liu, THU, for helpful discussions regarding the statistical analysis presented herein.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G. Z., C. W., K. X., and Y. D. conceived the concept and designed the experiments. G. Z. and T. Z. contributed to this work in the experimental planning, experimental measurements, data analysis, and manuscript preparation. Z. Z. and M. D. G. conducted the cryo-TEM test and contributed to the corresponding analysis. R. H., Q. W., and S.-S. C. participated in material synthesis and characterization. Y. C. and Z. L. assisted in the preparation of punch cells. manuscript preparation. K. X., C. J., and Y. D. co-wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the experimental results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Paul Rudnicki, and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, G., Zhang, T., Zhang, Z. et al. High-energy and fast-charging lithium metal batteries enabled by tuning Li+-solvation via electron-withdrawing and lithiophobicity functionality. Nat Commun 16, 4722 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-59967-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-59967-w

This article is cited by

-

Regulating anion chemistry in electrolytes from molecular principles to interphases engineering for high energy batteries

Science China Chemistry (2025)

-

Aligned electrospun polyacrylonitrile nanofibers coated with Li7La3Zr2O12 solid electrolytes for mechanically robust and flame-retardant membranes

Journal of the Korean Ceramic Society (2025)