Abstract

The enzyme glucocerebrosidase (GCase) catalyses the hydrolysis of glucosylceramide to glucose and ceramide within lysosomes. Homozygous or compound heterozygous mutations in the GCase-encoding GBA1 gene cause the lysosomal storage disorder Gaucher disease, while heterozygous and homozygous mutations are the most frequent genetic risk factor for Parkinson’s disease. These mutations commonly affect GCase stability, trafficking or activity. Here, we report the development and characterization of nanobodies (Nbs) targeting and acting as molecular chaperones for GCase. We identify several Nb families that bind with nanomolar affinity to GCase. Based on biochemical characterization, we group the Nbs in two classes: Nbs that improve the activity of the enzyme and Nbs that increase GCase stability in vitro. A selection of the most promising Nbs is shown to improve GCase function in cell models and positively impact the activity of the N370S mutant GCase. These results lay the foundation for the development of new therapeutic routes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The lysosomal enzyme glucocerebrosidase or acid-β-glucosidase (GCase, EC3.2.1.45) is responsible for the hydrolysis of the sphingolipid glucosylceramide (GlcCer), as well as for the transglucosylation of cholesterol by transferring the glucose moiety from GlcCer to cholesterol1. Biallelic mutations in the GCase-encoding GBA1 gene cause Gaucher Disease (GD), the most common lysosomal storage disorder2, while both heterozygous and homozygous mutations in GBA1 are the most common genetic risk factor for Parkinson’s disease (PD)3.

GD is characterized by a very broad spectrum of phenotypes, ranging from asymptomatic GD to patients showing hepatosplenomegaly, joint and bone pain and damage, anaemia and thrombocytopenia. Some forms of GD are neuropathic, and, depending on the neurological manifestation of the disease, GD is classified into three clinical subtypes (Type 1, Type 2, and Type 3)4. Type 1 GD is the most common variant and considered to be non-neurological: symptoms can be absent or systemic, and patients can develop the disease at any age. Type 2 presents the most severe neuropathic phenotype, with the onset of the disease in the first months of life and a rapid progression that leads to death during infancy. Type 3 is the chronic neuropathic form of GD, with patients surviving longer but presenting neurological symptoms over the whole course of their lives5. GD patients present a higher risk of developing PD, suggesting that even Type 1 GD can have neurological manifestations as patients age6.

PD is the second most common neurodegenerative disorder after Alzheimer’s disease, and is characterized by typical motor symptoms, such as tremor, rigidity, and bradykinesia. Non-motor symptoms also occur, such as gastrointestinal defects at early stages, and psychosis and dementia at the later stages7. About 10% of PD cases are inherited and caused by mutations in different genes, either in an autosomal dominant or in a recessive manner. The other 90% of the cases are sporadic and can be associated with environmental exposure to toxins and pesticides and/or mutations in genes that are risk factors for the disease7, such as GBA1. GD frequency in the general population is about 1 in 50000 to 100000 (https://medlineplus.gov/), while around 10 million people worldwide are affected by PD. About 5–8% of PD patients carry a GBA1 mutation, compared to less than 1% of healthy people. GBA1-associated PD presents earlier onset compared to typical sporadic PD8,9, and GBA1-PD patients are more likely to develop dementia and to die earlier compared to non-carriers10. More than 500 mutations in GBA1 have been associated with GD and PD (most of them summarized in ref. 11), including nonsense mutations, deletions, insertions, and missense mutations. Most of these mutations cause the GCase enzyme to be less stable and/or less active, although the exact link between the effect of the mutations and the severity of the disease is still largely unclear.

In normal conditions, GCase is synthesized by ribosomes that are bound to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and then transferred to the ER for the correct folding. GCase is subsequently trafficked to the lysosomes through the Golgi, while undergoing different glycosylations12. The two main suggested mechanisms of toxicity in GD and PD are thus linked to (i) impaired trafficking of the mutant protein (e.g., N370S or L444P) due to defective folding and stability, leading to ER stress and damage13,14,15, and (ii) reduced GCase activity, which causes the accumulation of substrates within the lysosomes and lysosomal dysfunction2. In neuronal cells, the impaired lysosomal function due to GCase mutation is associated with the aggregation of alpha-synuclein, with mitochondrial dysfunction and defective calcium handling16,17,18,19. Interestingly, GCase activity is reduced in sporadic PD brains20, even without accumulation of GCase substrates21, indicating a multilevel involvement of the enzyme in PD.

Currently, no cure for PD is available. GD patients are commonly treated by one of two strategies. A first strategy is enzyme replacement therapy, where recombinant GCase is provided intravenously. This strategy typically restores systemic symptoms but is unable to affect the neuropathic ones because of the inability of the recombinant enzyme to cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB). A second possible but more limited approach is substrate reduction therapy, through inhibition of glucosylceramide synthase, thus reducing the accumulation of GCase substrates by hampering their rate of biosynthesis. For GBA1-associated PD, a brain-permeant glucosylceramide synthase inhibitor, termed venglustat, was evaluated in clinical trials, but with no success in ameliorating the disease phenotype22.

Other possible therapeutic strategies targeting GCase both in PD and GD have been put forward, with the aim of stabilizing or activating the protein, or improving its trafficking to the lysosomes. Initially, this pharmacological chaperone approach was attempted unsuccessfully by exploiting iminosugar-based inhibitors, such as isofagomine23, to stabilize GCase by binding to the active site of the enzyme. This approach was hampered by the persisting binding of the chaperone to the GCase active site in the lysosomes, thus inhibiting the enzymatic activity. To overcome this limitation, iminosugars whose binding is disrupted at lysosomal pH are currently being synthesised and studied24,25,26. High throughput screening also allowed to identify non-iminosugar inhibitors able to act as chaperones for GCase when studied in vitro on the recombinant enzyme and on spleen lysates obtained from GD-patients carrying the N370S GBA1 mutation27. The quinazoline modulator JZ-4109 was shown to stabilize wild-type and N370S mutant GCase, and increase GCase abundance in PD- and GD-derived fibroblast cells28. Nevertheless, also JZ-4109 inhibits GCase activity by binding very close to the active site of the enzyme, suggesting it needs to dissociate once the enzyme reaches the lysosomes to avoid competition with the substrate. No information of further development of the molecule and (pre-)clinical applications is available to our knowledge. More recently also non-inhibitory small molecules acting as pharmacological chaperones for GCase were discovered, and their positive impact on iPSC-derived neurons from PD patients was demonstrated29,30. Other molecules that were shown to improve GCase function, and are currently in clinical trials for PD, are ambroxol and BIA-28-6156/LTI-29131,32,33, while their mechanism of action is still largely unclear. Although their exact binding mode is unknown, docking studies suggest that also these molecules might bind close to the GCase active site34,35.

In this work, we explored and validated the use of nanobodies (Nbs) as pharmacological chaperones to improve (mutant) GCase stability, trafficking, and activity. Nbs are small (~ 15 kDa) and stable single-domain fragments derived from camelid heavy chain-only antibodies36. Owing to their small size, stability, and ease of cloning and recombinant production, Nbs have frequently been used as tools in research, in diagnostics, and even as therapeutics36,37. They have the tendency to insert themselves into clefts or cavities on the surface of their antigens38, thus stabilizing certain protein conformations and/or modifying enzyme activity39,40,41,42. As such, Nb-mediated stabilization of GCase appears as an appealing approach to improve GCase folding in the ER and its transport to the lysosome, thus possibly reducing the amount of unfolded mutant GCase in the ER and increasing the amount of functional GCase in the lysosome, or even increase the enzymatic activity of GCase in the lysosome per se. With this strategy in mind, we were able to identify and characterize different sets of Nbs that stabilize or activate GCase in vitro and in cell models, using an allosteric mechanism that differs, to the best of our knowledge, from the currently available GCase chaperones.

Results

Identification of GCase-targeting nanobodies

To generate nanobodies (Nbs) specifically binding human lysosomal glucocerebrosidase (GCase), a llama was immunized with a commercial source of GCase (Velaglucerase, VPRIV®)43,44,45. To maximize the chances of obtaining a large repertoire of Nbs, which preferentially bind irrespective of the glycosylation pattern of GCase and outside its active site pocket, different phage display selection strategies were used in parallel. Hereto, GCase was first deglycosylated with Peptide:N-glycosidase F (PNGase F) and/or allowed to react with the covalent inhibitor conduritol-β-epoxide (CBE)46, resulting in the following combinations that were used for two subsequent rounds of phage display panning: (i) glycosylated GCase, (ii) glycosylated GCase bound to CBE, (iii), deglycosylated GCase, (iv) deglycosylated GCase bound to CBE (Supplementary Fig. S1). Moreover, to ensure that the selected Nbs also bind at the low lysosomal pH, washing steps using a buffer at pH 5.4 were incorporated in the phage display protocol. Sequencing of the Nb open reading frames resulting from these 4 selection strategies provided 38 unique sequences. These can be grouped into 20 sequence families, where members within a sequence family display > 80% sequence identity in their complementary determining region 3 (CDR3). One representative of each family was recloned in a pHEN29 vector and subsequently expressed in the periplasm of Escherichia coli as a C-terminally LPETGG-His6-EPEA-tagged protein, and the corresponding 20 Nbs were purified to homogeneity (Supplementary Fig. S2).

The Nbs bind GCase mostly in a glycosylation-independent way and with a variety of affinities

The binding of the purified Nbs to GCase (Velaglucerase) was first confirmed using ELISA, with binding defined as an ELISA signal of at least threefold above the GCase background and threefold above the signal of an irrelevant Nb. Using that criterion, we find binding for 11 out of the 20 tested Nbs (Nb1, Nb2, Nb3, Nb4, Nb6, Nb7, Nb8, Nb9, Nb10, Nb16, Nb17) (Fig. 1A). Interestingly, while no binding signal is observed for Nb12 and Nb18 on glycosylated GCase, a clear binding signal is obtained when using deglycosylated GCase (Supplementary Fig. S3). Also, for Nb10 a stronger ELISA signal is observed when using deglycosylated GCase. This is in good agreement with the fact that these Nbs result from phage display panning on deglycosylated GCase.

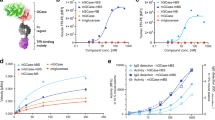

A ELISA of 20 purified Nbs using wild-type GCase or N370S GCase coated on the bottom of the ELISA wells. An irrelevant Nb is used as negative control, while the positive control displays the signal of a Nb (Nb17) directly coated in the ELISA plate. Each ELISA signal is the result of three independent experiments represented as mean values (bars) with standard deviations (error bars). B Representative Bio-Layer interferometry (BLI) traces for binding of Nb1 to wild-type GCase (upper panel), and fitting of the signal amplitudes (Req) versus Nb1 concentration curve on the Langmuir equation to determine the KD values (lower panel). C Equilibrium dissociation constants (KD) of the Nbs for wild-type GCase or N370S GCase. For wild-type GCase, BLI experiments were performed with biotinylated GCase immobilized on the Streptavidin sensors (see Supplementary Fig. S5 for results of the experiment using the inverse set-up). For N370S GCase, C-terminally biotinylated Nbs were immobilized on the Streptavidin sensors. KD values are determined similar to (B). KD values for wild-type GCase are represented as mean values ± standard deviations (n = 3), while reported KD values for N370S GCase are the result of a single experiment. Source data are deposited as Source Data files on Zenodo.

To determine the binding affinities (KD) of the Nbs for (glycosylated) GCase, we turned to biolayer interferometry (BLI). Hereto, randomly biotinylated GCase was immobilized on a streptavidin biosensor and titrated with increasing amounts of each of the Nbs, after which the equilibrium signals were plotted against the Nb concentrations and fitted on a Langmuir equation (Fig. 1B, C and Supplementary Fig. S4). Overall, the obtained KD values are in good agreement with the trend observed in ELISA. KD values in the sub-micromolar range are obtained for 9 of the Nbs, with Nb1, Nb8, and Nb17 showing the highest affinities (KD < 5 nM). Nb5 and Nb18 show low-affinity binding (KD in µM-range), while binding of Nb10 and Nb12 could only be observed when using deglycosylated GCase. No clear binding signals in BLI were obtained with Nb11, Nb13, Nb14, Nb15, Nb16, Nb19, and Nb20. Remarkably, while no binding was observed in BLI for Nb16, a clear binding signal was present in ELISA. To shed light on this apparent discrepancy, we used fluorescence anisotropy as an alternative method to assess the binding of GCase to 5-TAMRA-labeled Nb16 (Supplementary Fig. S5). Fitting of the resulting binding isotherm yielded a KD value of approximately 450 µM, confirming that Nb16 binds to GCase albeit with a very low affinity, which could explain the lack of signal in BLI. Finally, to verify that the observed binding affinities are unaffected by the immobilization of GCase on the sensor surface, we performed a BLI experiment where we titrated increasing GCase concentrations in solution to Nbs that are immobilized on the streptavidin sensors via a biotin molecule that is site-specifically attached to the C-terminus of the Nbs (Supplementary Fig. S6). With the exception of Nb5 and Nb12, the obtained KD values are similar in both BLI set-ups. However, for Nb5 and Nb12 we find significantly higher affinities in the latter experiment, indicating that these two Nbs bind to an epitope that is shielded or altered by the immobilization of GCase.

Different subsets of Nbs affect the activity and thermal stability of GCase in vitro

To characterize the impact of the 20 Nbs on the activity of wild-type GCase, we took advantage of a 4-MU based assay, as previously reported47. This approach allowed us to evaluate if any of the Nbs were able to increase the GCase activity in vitro, either by slowing down the time-dependent unfolding of the enzyme or by allosterically activating it. Hereto, GCase (Velaglucerase) was incubated for 30 min at 37 °C in the presence of each Nb to allow GCase-Nb complex formation (if any), then the 4-MU substrate was added and the mix was incubated for 90 min before the reaction was stopped to proceed with the measurement (Fig. 2A). This allowed to identify 7 Nbs able to significantly increase the activity of the wild-type GCase: Nb3, Nb4, Nb5, Nb6, Nb10, Nb16, and Nb18. Among them, 5 Nbs were able to augment the GCase activity by more than twofold (Nb3, Nb5, Nb6, Nb16, Nb18), while the increment due to Nb4 and Nb10 was between 1.5 and twofold. Interestingly, also Nb1, Nb2, Nb8, Nb9, and Nb19 showed a trend toward a positive impact on the enzymatic activity of the GCase (between 1.5 and twofold), albeit not statistically significant, while the others seem to have no effects on the enzyme activity (Fig. 2B). Isofagomine (25 µM) was used as a control and proved to reduce the GCase activity by about 70%. To understand if the presence of other proteins or cofactors would change the outcome of these measurements, we performed the 4-MU activity assay on cell lysates expressing wild-type GCase, following the same experimental setup. Interestingly, in this case only Nb10 and Nb16 showed a significant > twofold increase in GCase activity, while Nb9 and Nb18 were able to significantly improve the activity by 1.5 to twofold. Under these conditions, some Nbs were also showing a mild decrease in GCase functionality, i.e., Nb2, Nb6, Nb17, and Nb19 (Fig. 2C), even though not significant. This suggested that different experimental conditions may impact on the interaction between the different Nbs and the enzyme, affecting the improvement of the enzymatic activity in vitro. Overall, these results led us to conclude that Nb9, Nb10, Nb16, and Nb18 increase the GCase activity under both tested conditions.

A Schematic representation of the protocol for the in vitro 4-MU GCase activity assay; B Velaglucerase activity in the presence of each of the 20 Nbs showed that a subset of Nbs is able to significantly improve in vitro GCase enzymatic activity. Isofagomine (IFG, 25 µM) was used as a negative control (n = 6 replicates in three independent experiments, data represented as mean ± SEM, statistical analysis was performed using an Ordinary One Way Anova multiple comparison test, DF Nbs = 21, DF residual = 110, F value = 18.08); C GCase activity assay in cellular lysates in the presence of each of the 20 Nbs showed that a subset of Nbs is able to significantly improve in vitro GCase enzymatic activity in the cellular lysates, quite coherently with the impact of Nbs on the Velaglucerase activity. Isofagomine (IFG, 25 µM) was used as a negative control (n = 5 replicates in three independent experiments, data represented as mean ± SEM, statistical analysis was performed using an Ordinary One Way Anova multiple comparison test, DF Nbs = 21, DF residual = 88, F value = 47.54); D Thermal unfolding curves of GCase, obtained using a thermal shift assay at pH 7.0 (black line) and pH 5.2 (red line) in absence or presence of Nb1. E Overview of the results of the TSA assay for the full set of 20 Nbs. The plotted variation of Tm (ΔTm) is the difference between the Tm of GCase and GCase + Nb. The covalent inhibitor conduritol-β-epoxide (CBE) was used as positive control, and an irrelevant nanobody (Irr Nb) as negative control. Each TSA signal is the result of three independent experiments, shown as mean values (bars) with standard deviations (error bars). Source data are deposited as Source Data files on Zenodo. GCase, glucocerebrosidase; Nb, nanobody.

Pathogenic mutations in the GBA1 gene can also lead to a decreased cellular GCase activity by affecting the protein stability and subsequently causing unfolding in the ER. The development of molecular chaperones that increase protein stability, and thereby assist the correct trafficking through the ER toward the lysosome, is therefore regarded as a valid therapeutic strategy48,49,50,51. To test the influence of the 20 Nbs on GCase thermal stability, we used a fluorescence-based thermal shift assay (TSA)52. First, the melting temperature (Tm) of GCase was determined at both pH 7.0 and 5.2 (non-lysosomal and lysosomal pH), yielding Tm values of 50.8 °C and 58.0 °C, respectively (Fig. 2D). Screening of the GCase stability in the presence of the full set of Nbs, yielded 3 Nbs that considerably stabilize GCase at pH 7.0, with Nb1, Nb4, and Nb9 yielding an increase in Tm of 7 °C, 4 °C, and 4 °C, respectively (Fig. 2E). These stabilizing effects were less pronounced at pH 5.2, with Nb1 and Nb9 providing an increase in Tm of 3 °C and 2 °C, respectively, while Nb4 does not provide stabilization at this pH. In comparison, for the covalent active-site binding inhibitor CBE we find an increased stability of about 10 °C, while this compound completely destroys the enzyme’s catalytic activity.

Next, we assessed whether the increase in GCase thermal stability provided by Nb1, Nb4, and Nb9 also translates in protection against proteolytic degradation. To this end, GCase, either in absence or presence of each of these Nbs, was incubated with cathepsin L, a cysteine protease known to regulate GCase in lysosomes53. Similar to what was previously described53, under the experimental conditions used, incubation of GCase with cathepsin L leads to proteolytic degradation of more than 50% of the protein (Supplementary Fig. S7). However, incubation of GCase with Nb1 or Nb9 leads to a small but significant protection against this proteolysis. A similar trend is observed for Nb4, albeit no statistical significance is reached for this Nb. Thus, this confirms that the increase in thermal stability provided by certain Nbs also protects GCase from the action of proteases, probably by preventing unfolding or by rigidifying the folded conformation of the protein.

The structure of GCase in complex with Nb1 reveals the mechanism of stabilization

Since Nb1, Nb4, and Nb9, which belong to different sequence families, can stabilize the GCase fold, we next wondered whether they bind different regions of GCase or target a similar stability hotspot region of the protein. To test this, we performed a BLI-based epitope mapping of these 3 Nbs, and also included Nb17 as a high affinity but non-stabilizing and non-activating Nb control. For the epitope mapping we set up a pairwise competition-binding experiment, where in turn one of the Nbs was biotinylated and immobilized on the BLI sensor, while the other Nbs were added in excess to GCase in solution to assess their effect on the binding of GCase. This experiment shows that Nb1, Nb4, and Nb9 compete with each other for GCase binding, while this is not the case for Nb17 (Supplementary Fig. S8). This proves that all the stabilizing Nbs bind to the same or a closely overlapping epitope of GCase, probably implying that this corresponds to an important region for protein stability. In contrast, Nb17 binds to a different region of GCase.

To identify and characterize the stability hotspot in GCase, as well as the stabilizing mechanism of the Nbs, we co-crystallized GCase with Nb1. Hereto, we used a deglycosylated form of imiglucerase (Cerezyme®) as a source of GCase, which was mixed in a 1:1.2 ratio with Nb1 before setting up crystallizations41. Diffraction-quality crystals were obtained using 1.6 M magnesium sulfate heptahydrate and 0.1 M MES pH 6.5 as crystallization solution, and diffraction data were collected and the structure was refined to 1.7 Å resolution. The refined structure shows one molecule of GCase bound to one molecule of Nb1 in the asymmetric unit (Fig. 3A). As previously described, the structure of GCase displays a globular fold formed by 3 non-contiguous domains: domain I (residues 1–29 and 383–414) is a small three-stranded antiparallel β-sheet, domain II (residues 30–77 and 431–497) forms an eight-stranded β-barrel, and domain III (residues 78–382 and 415–430) adopts a (β/α)8 triose-phosphate isomerase (TIM) barrel, which contains the active site and the two catalytic residues E235 and E34043,54,55,56. During refinement, sugar moieties were added on residues N19 and N270, which are well-known and characterized glycosylation sites43. Additionally, two magnesium ions have also been included in the GCase structure, one of which is located in the active site and directly interacts with the two catalytic glutamate residues.

A Overall structure of the GCase-Nb1 complex. The three domains of GCase are colored in pink (domain 1 = three-stranded anti-parallel β-sheet domain), green (domain 2 = Ig-like domain), and light blue (domain 3 = (β/α)8 triose-phosphate isomerase (TIM) barrel). Nb1 is colored grey with the CDR1 loop in yellow, CDR2 loop in dark blue and CDR3 loop in red. The position of the active site of GCase is indicated with an arrow. B Close up view of some of the interactions between the Nb1 CDR1 loop (upper panel), CDR2 loop (middle panel), and CDR3 loop (lower panel) with GCase. Interacting residues are shown in stick representation. The structure and structure factors were deposited in the PDB (code 9ENA).

Nb1 binds to GCase on the opposite side of the active site and interacts at the interface between domain II and III (Fig. 3A). The observation that Nb1 is binding far from the GCase active site is in good agreement with our previous finding that the Nb does not negatively interfere with the catalytic activity. On the side of Nb1, most of the interactions with GCase are provided by residues from CDR2 and CDR3 (Fig. 3B). CDR1 provides only 2 interacting residues specifically interfacing with GCase domain II, with the main chain carbonyl of its residue Asp32 forming a H-bond with GCase residue Lys77. CDR2 interacts with residues belonging to GCase domains II and III. In particular, Ser55 forms a H-bond with Lys77 of domain II, while Thr60, Tyr61, Tyr62, and Asp64 form multiple salt bridges and/or H-bonds with residues Thr272, His274, Asn275, and Arg277 from domain III. Finally, most interactions are made by the very long CDR3 loop that partially folds into a short stretch of α-helix. Residues from CDR3 make multiple interactions with GCase domain III, with in particular the side chain of Gln226 of GCase forming multiple hydrogen bonds with main chain atoms of CDR3. This binding mode of Nb1, at the interface of two GCase domains, could explain its stabilizing effect by keeping these two domains tightly together.

Superposition of the structure of the GCase-Nb1 complex on a structure of unbound GCase (PDB 1OGS), shows no major conformational changes in GCase induced by the Nb (rmsd all atoms = 0.260 Å; rmsd Cα atoms = 0.229Å, using chain A of PDB 1OGS) (Supplementary Fig. S9)55. Only minor conformational changes are observed in the loops surrounding the entry to the GCase active site pocket, in particular in loop 1 (residues 311–319), loop 2 (residues 345–349), and loop 3 (residues 394–399). Interestingly, our structure in complex with Nb1 shows GCase in a state that has some features resembling the enzyme active state, with loop 1 adopting a nearly helical conformation, the side chain of residue Asp315 moving in the direction of residue Asn370, and the bulky side chains of Trp348 and Arg395 oriented away from the active site56,57,58.

ER-targeted Nb4 and Nb9 improve lysosomal GCase activity in live wild-type cells, but not the overall lysosomal proteolytic activity

Based on the in vitro results, studying the impact of the Nbs on either recombinant wild-type GCase or on endogenous GCase from cell lysates, we curated a shortlist of priority Nbs for in cellulo validation. The first group of selected Nbs (Nb1, Nb4, and Nb9) showed promise due to their capacity to stabilize wild-type GCase, with a defined mechanism of action. We then designed a set of plasmids for mammalian expression of the Nbs in fusion with a 3 × Flag tag and bicistronic co-expression with either eGFP or mCherry markers. Moreover, a targeting strategy based on established ER or lysosomal signal peptides59,60 was attained to either assist in the folding of GCase during ER maturation, or to enhance the stability or enzymatic activity within the lysosome, respectively. As controls, in each experiment we used an expression vector for a fragment of a non-relevant and non-functional protein (defined as Mock in the experiments) and/or untransfected control cells.

We first overexpressed the three lysosome-targeted (lyso-Nbs) and three ER-targeted Nbs (ER-Nbs) in HEK293T cells and assessed the expression levels of each Nb by western blot (Supplementary Fig. S10A and C). All ER-Nbs were expressed, though at different levels, whilst lyso-Nb1 was barely detectable compared to lyso-Nb4 and lyso-Nb9 and to ER-Nb1 (Supplementary Fig. S10C, D).

Next, we set out to identify the optimal experimental system for evaluating the effect of ER- and lyso-Nbs on GCase cellular properties. We first measured GCase levels and ER/lysosome response from lysates of Nb-transfected cells. Upon expression of ER-Nbs, the levels of GCase protein were unchanged (Supplementary Fig. S11A and E). Similarly, expression of lyso-Nbs did not affect GCase protein levels (Supplementary Fig. S11B and F). Ectopic expression of ER- or lyso-Nbs did not alter the overall levels of calnexin, which is induced during ER stress, or of the lysosomal protein LAMP1, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S11A–C and B–D).

To examine the impact of the Nbs on GCase activity only at the lysosomes and only on Nb-expressing cells, we exploited a flow-cytometry based assay to measure lysosomal GCase activity in live cells by employing the fluorogenic substrate PFB-FDGlu (5-(pentafluorobenzoylamino) Fluorescein Di-β-D-Glucopyranoside) (Supplementary Fig. S12) and co-expressing the Nbs with an mCherry reporter for flow cytometry analysis of transfected cells (Fig. 4A). Expression of lyso-Nbs did not result in any alteration of the lysosomal activity of GCase (Fig. 4C). In contrast, ER-Nb4 and ER-Nb9 showed a ~ 15% increase in the endogenous activity of lysosomal GCase, indicating that these Nbs improve GCase folding and stability during the ER maturation process, resulting in a lysosomal pool of GCase with enhanced activity (Fig. 4B).

A Schematic representation of the lysosomal GCase activity assay, performed using the PFB-FDGlu substrate in HEK293 live cells expressing different Nbs. Created in BioRender. Plotegher, N. (2025) https://BioRender.com/efdob53. B Expression of ER-Nb4, ER-Nb9, and ER-Nb16 significantly increased the lysosomal GCase activity by about 15%, as compared to ER-Mock transfected cells (n = 12 for ER-Mock and ER-Nb9 in 6 independent experiments, n = 6 for ER-Nb1, ER-Nb4 and ER-Nb16 in 3 independent experiments, data represented as violin plots, Shapiro–Wilk test for normality, Ordinary One Way Anova with multiple comparisons, DF Nbs = 4, DF residual = 31, F value = 9.58). C Only lysosomal-Nb16 improved GCase enzymatic activity (n = 15 for lyso-Mock, n = 9 for lyso-Nb9, n = 6 for ER-Nb1 and ER-Nb4 in 3 independent experiments, data represented as violin plots, Shapiro–Wilk test for normality, Ordinary One Way Anova with multiple comparisons, DF Nbs = 4, DF residual = 37, F value = 18.2). D Schematic representation of the DQ-BSA assay performed to evaluate lysosomal proteolytic activity upon Nb overexpression in HEK293T cells. Created in BioRender. Plotegher, N. (2025) https://BioRender.com/b8bx884. E No changes in lysosomal proteolytic activity in HEK293T cells overexpressing the selected ER-Nbs (n = 8 for ER-Mock, n = 9 for ER-Nb1, ER-Nb4, ER-Nb9, ER-Nb16 in three independent experiment, data represented as violin plots, Shapiro–Wilk test for normality, Ordinary One Way Anova with multiple comparisons, DF Nbs = 4, DF residual = 39, F value = 1.716). F No changes in lysosomal proteolytic activity in HEK293T cells overexpressing the selected lysosmal-Nbs (n = 9 for lyso-Mock, n = 10 for lyso-Nb1, n = 6 for lyso-Nb4, n = 7 for lyso-Nb9, n = 8 for lyso-Nb16 in four independent experiments, data represented as violin plots, Shapiro–Wilk test for normality, Ordinary One Way Anova with multiple comparisons, DF Nbs = 4, DF residual = 35, F value = 0.2793). Source data are deposited as Source Data files on Zenodo. GCase glucocerebrosidase, Nb nanobody, PFB-FDGlu 5-(Pentafluorobenzoylamino)Fluorescein Di-β-D-Glucopyranoside.

Given the ability of ER-Nb4 and ER-Nb9 to improve GCase activity in live cells, we next investigated their impact on the lysosomal proteolytic activity using the DQ-Red BSA marker and a cytofluorometry-based assay61 (Fig. 4D). The DQ-Red BSA dye is a fluorogenic substrate for proteases, which is hydrolyzed in the acidic compartment causing an increase in the emitted red fluorescence signal that correlates with the overall lysosomal function. As reported in Fig. 4E, cells transfected with the ER-Nbs present DQ-BSA fluorescence values similar to Mock cells, suggesting that Nbs did not affect the lysosomal protease activity. Similarly, no differences were found among the different lyso-targeted Nbs tested and the lyso-Mock expressing cells (Fig. 4F). This result indicates that Nbs do not impair nor enhance the overall lysosomal degradative capacity of the cell, even those able to improve GCase activity at the lysosomes. This may be explained by the fact that wild-type HEK293 cells do not display any impairment in the lysosomal function that needs to be rescued.

Selected ER-targeted Nbs improve GCase trafficking to the lysosomes

Since Nb1, Nb4, and Nb9 were shown to increase the thermal stability of GCase in vitro (Fig. 2E) and Nb4 and Nb9 enhance GCase lysosomal activity when targeted to the ER (Fig. 4B), we hypothesized that the mechanism by which the latter occurs is an ameliorated trafficking of the enzyme to the lysosomes. Thus, we assessed whether these ER-Nbs could indeed improve the trafficking of GCase to the lysosomes in cells. To this aim, the lysates of HEK293T cells overexpressing the selected ER-Nbs were incubated with ENDO H and PNGase F, two enzymes that digest glycans at different sites. Specifically, ENDO H cleaves immature glycans present in the ER but not after additional modifications that occur in the Golgi, which can be instead cleaved by PNGase F. Thus, the sensitivity of GCase to ENDO H or PNGase F is an indicator of the amount of protein present in the ER or post-ER, respectively. The higher the ratio between ENDO H-resistant and ENDO H-sensitive GCase, the more GCase is predicted to have reached the lysosomal compartment. We measured by western blot the level of total GCase and of GCase sensitive to ENDO H or to PNGase F in cell lysates (Fig. 5A). Quantification of the ER fraction or post-ER fraction was performed following previous methods62. The PNGase F-sensitive GCase band was considered as a reference for the deglycosylated GCase fraction. Thus, when quantifying the different bands in the ENDO H treated GCase lane, the band that runs at the same height as the band in the PNGase F lane corresponds to the protein that is still localized at the ER. The rest of the ENDO H treated GCase bands represented the post-ER GCase fraction, which was not deglycosylated by the ENDO H treatment (ENDO H resistant fraction). Quantification of the ratio between the band intensities corresponding to the post ER and to the ER GCase fraction, showed that Nb1 and Nb9 significantly increase the post ER/ER GCase fraction ratio, suggesting that they were able to promote the correct folding and trafficking of the protein through the ER and the Golgi (Fig. 5B). Nb4 also presented a trend toward amelioration of trafficking, even though it did not reach statistical significance. Taken together, this data shows that the epitope the three Nbs bind is not only crucial for GCase stability but also for the trafficking and maturation of the protein. We next performed colocalization analysis between the ER marker calnexin and the ER-targeted Nbs (Fig. 5C). Consistent with these findings, Pearson’s coefficients ranged between 0.2 and 0.4 (Fig. 5D), indicating only partial colocalization of the Nbs with the ER. The incomplete colocalization (i.e., values below 1 and smaller than Mock-expressing cells), suggests that the ER-targeted Nb4 and Nb9 bound to GCase are more likely to leave the ER and reach the lysosome. When performing colocalization analyses between the lysosomal marker LAMP2A and the ER-targeted Nbs on confocal images (Fig. 5E), we observed significantly increased Pearson’s coefficients for Nb9 (Fig. 6F), reaching values up to 0.76 in certain cells, further supporting the hypothesis that Nb9 facilitates the trafficking of GCase to the lysosomes.

A Representative western blot of lysates of Nb-transfected HEK293T cells incubated with ENDO H and PNGase F to identify the ENDO H resistant (post ER, higher MW band) and the ENDO H sensitive bands (ER, lower MW band). B Ratio between the post ER and ER fraction of GCase (ENDO H resistant/ENDO H sensitive) measured in cell lysates using lysates incubated with ENDO H and PNGase as a reference show an increase in the ER-Nb1 and ER-Nb9, and an increasing trend for ER-Nb4, as compared to the control (n = 5, data represented as mean ± SEM, Shapiro–Wilk test for Normality, One Way Anova with multiple comparisons, DF Nbs = 3 DF residual = 10 F value 5.996). C Representative confocal images of HEK293T cells transfected with Nb1-flag-IRES-EGFP targeted to the ER stained for flag (yellow) and calnexin (magenta), while EGFP was used as a marker for Nb-flag expressing cells (scale bar 10 µm). D Colocalization of ER-targeted Nbs in the ER in HEK293T cells overexpressing the selected Nbs was evaluated by calculating the Pearson’s coefficient between flag and calnexin signals. All the Nbs present a certain degree of colocalization with the ER marker calnexin, which is significantly reduced in Nb4, Nb9, and Nb16, as compared to the Mock transfection (n = 16–28 cells in 2 independent experiments, data represented as violin plot, Shapiro–Wilk test for normality, Kruskal–Wallis test with multiple comparisons). E Representative confocal images of HEK293T cells transfected with Nb9-flag-IRES-EGFP targeted to the ER stained for flag (yellow) and LAMP2A (magenta), while EGFP was used as a marker for Nb-flag expressing cells (scale bar 10 µm). F Localization of ER-targeted Nbs to the lysosomes in HEK293T cells overexpressing the selected Nbs was evaluated by calculating the Pearson’s coefficient between flag and LAMP2A signals. Colocalization with the lysosomal markers is significantly increased for Nb9, as compared to the control (n = 26–35 cells in 2 independent experiments, data represented as violin plot and median values, Shapiro–Wilk test for normality, Kruskal–Wallis test with multiple comparisons). Source data are deposited as Source Data files on Zenodo. GCase glucocerebrosidase, Nb nanobody.

A Nb10 and Nb16 are able to significantly improve in vitro N370S GCase enzymatic activity. Isofagomine (IFG) was used as a negative control (n = 6 replicates in three independent experiments, data represented as mean ± SEM, statistical analysis was performed using an Ordinary One Way Anova multiple comparison test); B GCase activity assay in gut lysates from hN370S GBA1−/− mice incubated with Nb1, Nb4, Nb9, Nb10, and Nb16 showed that Nb10 and Nb16 are able to significantly improve in vitro N370S GCase enzymatic activity. (n = 4 tissue per genotype, each tested in 3 independent experiments in 3 technical replicates, data represented as histograms showing the average value for the technical replicates for each experiment in each biological sample, statistical analysis was performed using an Ordinary One Way Anova multiple comparison test, DF Nbs = 5, DF residual = 55, F value = 4.926). C Co-expression of the N370S GCase mutant and the ER-Nb4 and ER-Nb9 in GBA1 KD cells induced an increase in the lysosomal N370S GCase activity of about 60–70%, as compared to ER-Mock transfected cells, while no effects were observed for ER-Nb1 and ER-Nb16 (n = 8 for ER-Mock, n = 4 for ER-Nb1, Nb4, Nb9, n = 5 for ER-Nb16 replicates in three independent experiments, data represented as violin plots, an Ordinary One Way Anova test with multiple comparisons, after Shapiro–Wilk Normality test was used for the statistical analysis Df Nbs = 4, Df Residual 24, F = 14.96). D Co-expression of N370S GCase mutant and the lysosomal-targeted Nb16 in GBA1 KD cells significantly increased the lysosomal N370S GCase activity, as compared to lysosomes-Mock transfected cells, while Nb1, Nb4, and Nb9 did not affect lysosomal N370S GCase activity when targeted to the lysosome (n = 11 for lyso-Mock, n = 4 for lyso-Nb1, Nb4, Nb9, n = 5 for lyso Nb16 replicates in three independent experiments, data represented as violin plots, a Kruskal–Wallis test with multiple comparisons, after Shapiro–Wilk Normality test was used for the statistical analysis). Source data are deposited as Source Data files on Zenodo. GCase glucocerebrosidase, Nb nanobody, PFB-FDGlu 5-(Pentafluorobenzoylamino)Fluorescein Di-β-D-Glucopyranoside.

Nb16 is able to improve lysosomal GCase activity in live cells when targeted to the ER or to the lysosomes

The remarkable effect of Nb16 on GCase activity in vitro (Fig. 2B, C) prompted us to further investigate the impact of Nb16 on lysosomal GCase activity in live cells. Similar to the other Nbs, Nb16 was cloned in a bicistronic plasmid with a 3 × FLAG epitope at the C-terminus and a sequence targeting the ER or the lysosome, together with a fluorescent protein (EGFP or mCherry). For the two targeting strategies, Nb16 was detected in HEK293T cells by western blotting and confocal imaging (Supplementary Fig. S10). Similar to Nb1, Nb4, and Nb9, ER- and lysosome-targeted Nb16 did not affect GCase expression, or calnexin and LAMP1 levels (Supplementary Fig. S11). However, while no significant effects were observed on total GCase protein levels (Supplementary Fig. S11), Nb16 significantly increased endogenous GCase activity by 25% when targeted to the ER (Fig. 4B). Moreover, an even higher improvement (50%) was observed when Nb16 was targeted to the lysosomes (Fig. 4C). Thus, consistent with our in vitro data indicating that Nb16 is a GCase activator, this Nb stands out as the only lysosomal-targeted Nb that enhances GCase activity in live cells, in contrast to lyso-Nb1, Nb4, and Nb9 (Fig. 4B). Finally, confocal imaging revealed that Nb16, similar to Nb9, exhibits reduced colocalization with the ER marker calnexin. However, unlike ER-Nb9, the colocalization of the ER-Nb16 with the lysosomal marker LAMP1 remained unchanged (Fig. 5D and F).

A subset of Nbs bind and increase the activity of the GCase N370S PD mutant in vitro and in cell models

GCase N370S is the most common mutation associated with PD and GD. This mutant shows significantly reduced catalytic activity in vitro and in cells13,63. Of note, previous studies showed that GCase is misprocessed in the ER leading to ER stress in iPSC-derived dopaminergic neurons13. N370S retention in the ER was also shown in PD-patient fibroblasts63. Thus, N370S mutant GCase is an interesting paradigm to test the potential beneficial effects of our best performing Nbs. To this aim, we purified the recombinant GCase-N370S protein and tested the full set of 20 purified Nbs for binding on GCase N370S in ELISA (Supplementary Fig. S13 and Fig. 1A). Nb1, Nb6, Nb8, Nb10, Nb16, and Nb17 showed a > threefold binding signal over the background. Nevertheless, many other Nbs that bind to wild-type GCase also gave a clear binding signal above the background for N370S, including Nb4 and Nb9.

Next, we used BLI to determine the binding affinities (KD) for a selected subset of Nbs: Nb1, Nb4, Nb9, Nb10, Nb16, and Nb17, based on the results obtained on the wild-type enzyme in vitro (Supplementary Fig. S14). In this case, the Nbs were site-specifically biotinylated at their C-terminus, captured on a Streptavidin sensor and titrated with increasing concentrations of the N370S mutant. No binding was observed for Nb16 in BLI, while a weak binding signal was observed in ELISA. Similar to what is observed for wild-type GCase, this indicates that Nb16 also displays a very low affinity binding to the N370S mutant. The other Nbs bind to the N370S mutant with comparable affinities to the wild-type enzyme, with the notable exception of Nb10, which showed a fivefold higher affinity (Fig. 1C). We next investigated the impact of the Nbs on the activity of GCase N370S in vitro using the classical 4-MU assay. This experiment was performed only for a selection of Nbs that show interesting properties in vitro and in cells for the wild-type GCase protein. The outcome yielded a > twofold significant increase in the enzyme activity for Nb10 and Nb16 (Fig. 6A).

To corroborate these results in a mouse model, we measured the effect of these Nbs on GCase activity using gut lysates from the Gba1−/− hN370S mice, which express the human GBA1 N370S gene in a null murine Gba1 background60 and present a reduced GCase activity in vitro (Supplementary Fig. S15). As Fig. 6B illustrates, addition of Nb10 and Nb16 to Gba1−/− hN370S gut lysates significantly increased GCase activity by about twofold, with a trend of increase also observed for Nb4. Overall, these findings indicate that Nb10 and Nb16 are efficient activators of GCase in vitro, and thus emerge as promising candidates for correcting mutant GCase activity.

To investigate the possible impact of the stabilizing Nbs, i.e., Nb1, Nb4, and Nb9, in improving the trafficking and lysosomal activity of N370S GCase in live cells, we exploited a CRISPR/Cas9 GBA1 knockdown (KD) model (Supplementary Fig. S16) in which we co-expressed the N370S mutant and the different Nbs. Both the clones 6E and 11 F GBA1 KD cells presented reduced GCase level by western blot (Supplementary Fig. S16A, B) and reduced lysosomal GCase activity in live cells (Supplementary Fig. S16C), as evaluated using the PFB-FDGlu substrate assay. We chose to exploit the 11 F GBA1 KD cells, which presented the larger reduction in GCase levels and activity, as null background to re-express the N370S GCase mutant. Upon overexpression, we verified that > 80% of the N370S expressing cells were also expressing the Nbs by immunocytochemistry (Supplementary Fig. S16D), and that N370S overexpression induced an overall increase in lysosomal GCase activity in 11 F GBA1 KD live cells (Supplementary Fig. S16E). When overexpressing Nb4 and Nb9 targeted to the ER, the increase in the N370S GCase lysosomal activity was between 60% and 70% as compared to Mock-transfected cells (Fig. 6C). No effects were observed for ER-Nb1 (Fig. 6C), nor for Nb1, Nb4 and Nb9 targeted to the lysosomes (Fig. 6D). This finding is in agreement with the known effect of the N370S mutation in impairing the trafficking of GCase to the lysosomes, which appears to be rescued by the expression of the Nb4 and Nb9 at the ER. A different behaviour was observed for Nb16, which improved N370S GCase activity only when delivered to the lysosomes (Fig. 6D). Taken together, these data suggest that Nb16, despite being a poor binder, acts as a potent activity enhancer by potentially activating GCase’s enzymatic activity in the native lysosomal compartment (Fig. 4B, C).

Discussion

The lysosomal enzyme glucocerebrosidase (GCase) plays a fundamental role in the complex cellular pathways linked to lysosome-dependent autophagy and proteostasis13,16,64,65. Biallelic (homozygous or compound heterozygous) mutations in the gene encoding GCase (GBA1) are causative for the lysosomal storage disorder GD, whereas heterozygous or homozygous mutations are the most important genetic risk factor for the development of PD3. Importantly, GCase dysfunction was also observed in models or patients of other inherited forms of PD and in sporadic PD20,29. Hence, GCase is considered as an appealing therapeutic target for both disorders. Most of the disease-linked GBA1 mutations cause defects in GCase folding, stability, trafficking and/or activity, suggesting that possible strategies to target this protein and ameliorate its function would involve the development of pharmacological chaperones able to act as stabilizers and/or activators66,67,68,69. However, while some of such currently available chaperone molecules were tested in clinical trials, none of them actually showed a significant impact in PD/GD models or patients and reached the market so far70.

Here, we present the identification of different families of nanobodies (Nbs) directed against GCase, that were thoroughly characterized in vitro to reveal their ability to improve GCase stability and activity. One factor that might contribute to the failure in the clinic of many of the current pharmacological chaperones, including iminosugars, non-iminosugars, and other types of molecules, is that they commonly bind into or close to the GCase active site pocket and hence act as inhibitors of its catalytic activity70. To overcome such potential problems, and to screen from the beginning for Nbs that bind outside the active site pocket and act in a true allosteric fashion, we devised a phage display selection procedure using both apo-GCase, containing no ligands bound to its active site, and GCase where the active site is blocked with the covalent inhibitor CBE. Additionally, to obtain Nbs with maximal versatility and the capacity to bind GCase in different cellular compartments and different mutant forms, we reasoned that it would be advantageous that the Nbs can bind to GCase irrespective of its glycosylation state. Hereto we performed phage display selections with either glycosylated or deglycosylated GCase (Velaglucerase).

The selection procedure finally yielded a panel of 20 different Nbs families, where one representative of each family was purified and used for further biochemical/biophysical characterization. The majority of the obtained Nbs show clear binding to GCase in ELISA and BLI, and display affinities in the low to high nanomolar range (Fig. 1). Nevertheless, some other Nbs either show no binding or very low affinity binding, while they were picked up during phage display panning. This could be due to the fact that more GCase is directly coated to the immunosorbent plate during selections and that the selection conditions were different than in the ELISA. As we envisioned in our selection strategy, most of the Nbs bind in a glycosylation-independent way, except for Nb10, Nb12, and Nb18, which seem to bind better to the deglycosylated GCase (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. S3).

A priori we envisioned two potential and possible overlapping functions for the GCase-targeting Nbs: (i) Nbs that increase the conformational stability of GCase and would thereby prevent unfolding and aid in the trafficking of GCase through the ER toward the lysosome, which we call Class I Nbs, and (ii) Nbs that increase the catalytic activity of GCase, which we call Class II Nbs. Detailed in vitro characterization of the purified Nbs allowed us to pinpoint these properties. First, a TSA experiment showed that three Nbs - Nb1, Nb4, and Nb9 - increase the melting temperature of GCase in vitro (Fig. 2). GCase on its own is significantly more stable at the lysosomal pH than at neutral pH (Tm of 58 °C and 50.8 °C at pH 5.2 and 7.0, respectively). All three Nbs stabilize GCase at neutral pH, with Tm shifts of 7 to 4 °C, while only Nb1 and Nb9 also stabilize GCase at pH 5.2, albeit to a lesser extent. The stabilizing effect at neutral pH, corresponding to the pH in the ER, would potentially make these Nbs exquisite tools to facilitate the trafficking of (mutant) GCase through the ER and act as molecular chaperones. In agreement with their stabilizing effect, Nb1 and Nb9 (not statistically significant for Nb4) also protect GCase from degradation by its natural lysosomal protease cathepsin L (Supplementary Fig. S7). This categorizes Nb1, Nb4, and Nb9 as Class I Nbs. Interestingly, epitope mapping shows that all three class I Nbs bind to overlapping epitopes of GCase (Supplementary Fig. S8), thereby unveiling a hotspot of protein stability on the GCase surface. To characterize this binding pocket, we solved the crystal structure of GCase in complex with the highest affinity Class I Nb, Nb1 (Fig. 3). This structure shows that Nb1 mainly uses its CDR2 and CDR3 loops to interact with GCase, with CDR3 being particularly long and partially adopting an α-helical conformation. Nb1 binds to GCase at the opposite side of its active site and at the interface of GCase domain II and III (Supplementary Fig. S17). Specifically, residues from the CDR2 and CDR3 loops of Nb1 interact with GCase domain III and the linker region between domain II and III, while the CDR1 loop makes two interactions with GCase domain II. We hypothesize that the stabilizing effect of the class I Nbs could stem exactly from this interaction on the interface of domain II and III, thus keeping both domains tightly together. Our structural analysis thus shows that the Class I Nbs bind to a true allosteric pocket, located at large distance from the GCase active site, which turns out to be crucial for GCase stability. To the best of our knowledge, this binding pocket is completely different from the binding sites of any previously described GCase chaperone70. Indeed, a number of compounds have been recently discovered that either activate or stabilize GCase by binding also to an allosteric pocket (Supplementary Fig. S18)28,71,72,73. While a subset of these compounds bind to a site close to the GCase active site on the GCase dimer interface (e.g., JZ-502928, compound 1471, and compound 3273), others bind further away from the active site in a pocket on the interface of GCase domain II and domain III (e.g., compound 2872 and compound 3173). Nevertheless, none of these reported molecules targets the same pocket as Nb1 (Supplementary Fig. S18). Our discovery of a novel stability hotspot on the GCase surface may also facilitate the future development of (small) molecules targeting this region to improve GCase wild-type or mutant properties. Important for the development of such pharmacological chaperones that guide GCase through the ER toward the lysosome, is the observation that the class I Nb epitope differs from the binding sites of LIMP-2 and Saposin-C (Supplementary Fig. S19). These proteins function as a natural molecular chaperone for the import of GCase in the lysosome and as activator of GCase in the lysosome, respectively12,57. Computational as well as experimental methods have shown that both proteins bind in the vicinity of the GCase active site pocket, at binding surfaces that do not overlap with the Nb1 epitope (Supplementary Fig. S19)58,74. Additionally, a recent cryo-EM structure of the GCase-LIMP-2 complex bound to two pro-macrobodies derived from Nb1 and Nb6 unequivocally shows that these two Nbs bind GCase epitopes that do not overlap with the LIMP-2 binding surface75. This implies that any molecular chaperone binding to the identified allosteric pocket, including the class I Nbs, would also very likely not interfere with the binding of either Saposin-C or LIMP-2. Interestingly, it has been suggested that even wild-type GCase is not completely and correctly folded in the ER, meaning that a significant part of the newly synthesized enzyme never reaches the lysosomes76. In this frame, the identified Class I Nbs may be able to stabilize the unfolded wild-type GCase fraction retained at the ER in normal individuals or carriers of GBA1 mutations, promoting its trafficking to the lysosomes with the final outcome of increasing the levels of functional GCase in this individual. This would represent a valuable approach for all those PD patients carrying either heterozygous mutations in GBA1, or presenting reduced GCase activity unrelated to genetic variants.

To identify Class II Nbs, 4-MU based GCase activity assays were performed with all 20 Nbs and using either purified GCase or cell lysates expressing recombinant GCase (Fig. 2). These experiments revealed that Nb3, Nb4, Nb5, Nb6, Nb9, Nb10, Nb16, and Nb18 act as Class II Nbs, able to increase GCase activity in either or both assays. However, it should be noted that the experimental setup of the assays, where the GCase-Nb complex is incubated for 2 h before the amount of product is measured, can result in an increased observed activity either by increasing the enzymatic activity per se or by preventing or slowing down the time-dependent unfolding of the enzyme. Surprisingly, Nb16 has the strongest activity-increasing effect (about a fourfold increase for both pure GCase and GCase present in cellular lysates), even though its affinity for GCase seems to be very low (KD value of approximately 450 µM as determined using fluorescence anisotropy titration). This outcome thus poses interesting questions about the exact mode of action of Nb16 on GCase activity, which will require further elucidation.

Based on the in vitro results and considering the two identified classes of GCase-Nbs, we shortlisted four Nbs for further in cellulo studies. We selected Nb1, Nb4, and Nb9 for their GCase-stabilizing effect (Class I), and Nb16 for its ability to strongly increase the GCase enzymatic activity despite having a low binding affinity (Class II). In order to overcome the limitation of the common inability of Nbs to cross intracellular membranes, we directly targeted the Nbs either to the ER or to the lysosomes. All Nbs were expressed when targeted to the ER, while only Nb4, Nb9 and—to a lesser extent—Nb16 could be detected when expressed in the lysosome (Supplementary Fig. S10). This potentially reflects a difference in the vulnerability of the Nbs to the aggressive environment in the lysosome. To specifically assess the impact of these modifiers only in the sub-population of cells expressing the Nbs, we established robust flow cytometry-based assays where Nbs were co-expressed with mCherry, and where GCase activity was tested with the fluorescent substrate PFB-FDGlu for in-cell recording. Although the used HEK293T cells express fully functional wild-type GCase, and therefore lack any enzymatic or lysosomal defects, we still observed a 15% increase in lysosomal GCase activity in the presence of ER-Nb4 and ER-Nb9 (Fig. 4). This aligns with the ability of these Nbs to enhance the fraction of GCase in post-ER compartments and the lysosome, by stabilizing the fraction of wild-type GCase that is not folded properly and is retained in the ER76 (Fig. 5). Another interesting observation was that ER-targeted Nbs showed a reduced colocalization with the ER, compared to a control ER-targeted mock sequence (Fig. 5), suggesting that ER-Nbs bind GCase in the ER and then “hitchhike” together with the enzyme through the Golgi toward the lysosomes. This is also confirmed for Nb9 by an increased colocalization to the lysosomes as compared to mock expressing cells (Fig. 5), which suggests that Nb9 may be the most promising among the stabilizing (Class I) Nbs in live cells. Of interest, no effects on GCase activity were observed when lysosome-targeted Nb1, Nb4, and Nb9 were expressed (Figs. 4 and 6). This appears coherent with the fact that these 3 Nbs belong to the GCase stabilizing Class I Nbs and only to a lesser extent increase GCase activity in vitro. Hence, a possible interpretation is that when specifically targeted to the lysosomes, the primary stabilizing function of the class I Nbs is irrelevant in these organelles. Our model, implying that the Class I Nbs (Nb1, Nb4, Nb9) aid in the trafficking of GCase to the lysosomes, is also in good agreement with the GCase-Nb1 structure, which shows that these Nbs would not interfere with LIMP-2 and Saposin-C binding. Interestingly, the class II Nb16 showed enhanced GCase activity, not only when targeted to the ER, but especially when targeted to the lysosome (by 25% and 50%, respectively). This is in good agreement with the results obtained in vitro, and suggests that Nb16 mainly acts by directly increasing the GCase enzymatic activity.

Additionally, nearly all Nbs that bind wild-type GCase also show binding to the major disease-linked N370S mutant in ELISA and BLI (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. S14). This is an important finding with respect to any future therapeutic applications in a clinically relevant setting. We also showed that the lysosomal GCase activity of the N370S mutant, when expressed in cells overexpressing the stabilizing Nb4 and Nb9 targeted to the ER, can be increased by about 60–70%. This is coherent with the fact that N370S trafficking was shown to be impaired13, suggesting that the mechanism by which ER-Nb4 and ER-Nb9 impact on the mutant enzyme is by improving its delivery to the lysosomes, as we showed for the wild-type protein (Fig. 5). Interestingly, Nb16 (and Nb10) induce a significant increase in N370S GCase activity in vitro, in both the experimental conditions tested (Fig. 6). In good agreement with these in vitro results, Nb16 was able to increase the N370S activity when targeted to the lysosomes.

With these promising Nbs in hand, several approaches can be envisaged to explore their translational potential. First, the Nbs should be evaluated in clinically relevant cell models and in vivo systems. Besides mice models carrying mutations in GBA1, also zebrafish models that express the mutated human GCase may be considered as they are easy to handle and maintain77. Furthermore, the effects of these Nbs on other clinically relevant GCase mutations should be investigated. This could involve using patient-derived fibroblasts or neurons generated from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) obtained from PD or GD patients. However, the inability of Nbs to cross the BBB and cell membranes, highlight the need to optimize effective delivery strategies. Promising approaches include the use of liposomes, vesicles, brain shuttle constructs, and adeno-associated virus-based vectors78,79. Alternatively, small-molecule mimetics targeting the binding pockets of the stabilizing or activating Nbs could be developed. Taken together, given the current lack of disease-modifying therapies for PD and GD, our results present the GCase-targeting Nbs as valuable starting points for the development of new generations of allosteric molecular chaperones and open exciting avenues for therapeutic intervention.

Methods

Ethical statement

Our research complies with all relevant ethical regulations. Mice were maintained within the Animal Facility of the Department of Biology, at the University of Padova; dark/light cycles were 12 h/12 h, temperature between 21 and 24 °C and humidity between 60% and 65%. Experiments were conducted according to the Italian Ministry of Health and the approval by the Ethical Committee of the University of Padova and of the Italian Ministry of Health (authorization number D2784.N.QHV).

The Llama vaccinations to obtain nanobodies fell within the scope of study 2021.2 that was approved by the VUB Ethics Committee Animal Research. All animal vaccinations were performed in strict accordance with good practices and the European Union animal welfare legislation.

Immunization and Nb selection

A llama was immunized using a six-week protocol with weekly immunizations of GCase (Velaglucerase, VRPIV®, Takeda) in the presence of GERBU adjuvant, and blood was collected 4 days after the last injection. All animal vaccinations were performed in strict accordance with good practices and EU animal welfare legislation. The construction of immune libraries and Nb selection via phage display were performed using previously described protocols80. In brief, starting from the PBMCs collected from the llama blood after immunization, the open reading frames coding for the variable domains of the heavy-chain antibody repertoire were cloned in a pMESy4 phagemid vector (GenBank KF415192), resulting in an immune library of 3.3 × 108 transformants. This Nb repertoire was expressed on the tip of filamentous phages after rescue with the VCSM13 helper phage. Four phage display selections (two rounds each) were performed using solid phase coating on a 96-well MaxiSorp NUNC-Immuno plate (Thermo Fischer Scientific): (1) glycosylated GCase, (2) glycosylated GCase bound to CBE, (3) deglycosylated GCase, (4) deglycosylated GCase bound to CBE. For selections (2) and (4), proteins were incubated for 30 min on ice with 10 µM CBE. Solid phase coating of all proteins was performed in a coating buffer containing 100 mM NaHCO3 pH 8.2. Washing steps were performed with McIlvaine buffer (100 mM Na2HPO4 and 10 mM citric acid) pH5.4, while 0.4% milk was added to this buffer for the binding step. Several single colonies were picked after each round of phage display selection and sequence analysis was used to classify the resulting Nb clones in sequence families based on their CDR3 sequence.

Nb cloning, expression and purification

After Nb selection, the Nb-coding open reading frames were recloned from the pMESy4 to the pHEN29 vector. Upon expression in an E. coli non-suppressor strain both vectors yield proteins with an N-terminal pelB signal sequence to translocate the recombinant protein to the periplasm. Additionally, pMESy4 provides a C-terminal His6-tag and EPEA-tag ( = CaptureSelect™ C-tag), while pHEN29 provides a C-terminal LPETGG-His6-EPEA-tag that allows site-specific labelling of the proteins using Sortase chemistry81. Expression of Nbs from the former plasmid is used for subsequent structural biology purposes, while the latter is used for labelling of Nbs in BLI experiments.

The Nbs were expressed and purified as previously described82. The Nb expression plasmids were transformed in E. coli WK6 (Su−) cells. Cells were grown at 37 °C in Terrific Broth medium to an OD600 ~ 1.0. Protein expression was induced by adding 1 mM IPTG (isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside) and incubated overnight at 28 °C. After harvesting, cells were lysed by osmotic shock to recover the periplasmic fraction. Nbs are purified via affinity chromatography on Ni2+-NTA Sepharose followed by a dialysis step (50 mM HEPES pH 8.0 and 300 mM NaCl).

Deglycosylation of GCase

Velaglucerase (VRPIV®, Takeda) and Imiglucerase (Cerezyme®, Sanofi) were deglycosylated using PNGase F enzyme (New England Biolabs). The deglycosylation reaction was performed according to the recommendation from the manufacturer, using 0.5 U PNGase F/1 µg glycosylated protein for 72 h at 25 °C. The deglycosylation reaction was confirmed by SDS-PAGE, and deglycosylated proteins were further purified using size exclusion chromatography (S75 10300 increase GL) in 10 mM MES pH6.5, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT and 5% glycerol.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA)

GCase, deglycosylated GCase and the GCase N370S mutant were solid-phase coated on the bottom of a 96-well ELISA plates (Maxisorp Nunc-immuno plate, Thermo Fischer Scientific), using a concentration of 1 µg/mL protein in coating buffer (100 mM NaHCO3 pH8.2). All the washing, binding (0.4% milk) and blocking (4% milk) steps were performed using PBS supplemented with 0.05% tween-20. The binding of the Nbs to the coated protein was detected via their EPEA-tag using a 1:4000 CaptureSelectTM Biotin anti-C-tag conjugate (Thermo Fischer Scientific) in combination with 1:1000 Streptavidin Alkaline Phosphatase (Promega). Colour was developed by adding 100 µL of 3 mg/mL disodium 4-nitrophenyl phosphate solution (DNPP, Sigma Aldrich) dissolved in 100 mM Tris, 100 mM NaCl, and 5 mM MgCl2 pH 9.5, and measured at 405 nm (SpectraMax 340 PC Microplate reader, Molecular Devices).

Biolayer Interferometry (BLI)

Prior to BLI experiments, Nbs expressed and purified from the pHEN29 plasmid (with a C-terminal LPETGG-His6-EPEA tag) were site-specifically labeled at their C-terminus using Sortase-mediated exchange with a biotin-labeled GGGYK peptide (GenicBio). GCase was randomly labeled on lysine residues using the EZ-Link™ Sulfo-NHS-LC-Biotin kit (Thermo Fischer Scientific), according to the manufacturers’ recommendations. BLI measurements were performed at 25 °C using an Octet Red96 (FortéBio, Inc.) system in PBS pH7.5, 0.01% Tween-20 supplemented with 0.1% BSA. Either biotinylated GCase or biotinylated Nbs were loaded onto streptavidin-coated (SA) biosensors at a concentration of 1 µg/mL, and the binding of a concentration gradient of unlabelled Nbs or GCase, respectively, was assessed (using association and dissociation times of 600 s). The association/dissociation traces were fitted with a 1:1 binding model using either the local, partial or global (full) options (implemented in the FortéBio Analysis Software). The resulting Req values were subsequently plotted against the Nb concentration and used to derive the KD values from the corresponding dose-response curves fitted on a Langmuir model (figures were generated using GraphPad Prism10).

Fluorescence anisotropy

Prior to fluorescence anisotropy experiments, Nb16 was site-specifically labeled at its C-terminus using Sortase-mediated exchange with a 5-TAMRA-labeled GGGYK peptide (GenicBio). Fluorescence anisotropy measurements were performed at 25 °C in PBS pH7.5, using a Cary Eclipse fluorescence spectrometer (Agilent) and excitation and emission wavelengths of 555 and 580 nm, respectively. 5-TAMRA-labelled Nb16 at a fixed concentration of 250 nM was incubated with a dilution series of GCase (500–16 µM) before measuring the fluorescence anisotropy signal. Anisotropy values were plotted against the GCase concentration, and the resulting binding isotherm was fitted to a quadratic binding equation using GraphPad Prism 10.

Thermal Shift assays (TSA)

Thermal unfolding of GCase was followed by thermal shift assays using SYPRO orange fluorescence as dye and a CFX connect real-time PCR system (Bio-Rad)48. 0.25 mg/mL (4 µM) GCase was incubated with 20 µM of the different Nbs for 30 min on ice and combined with 5× SYPRO Orange protein Gel Stain (Thermo Fischer Scientific), in Mc Ilvaine buffer pH 5.2 or pH 7.0 consisting of 0.1 M citric acid and 0.2 M dibasic sodium phosphate in a total volume of 25 µL. The temperature was increased from 20 °C to 80 °C at 1 °C/min steps. All measurements were performed in triplicate and the melting temperatures were determined by fitting the first derivatives of the data with a Boltzmann sigmoidal equation (GraphPad Prism). ΔTm (°C) values are the difference in melting temperature between GCase and GCase incubated with different Nbs.

Cathepsin L proteolysis assay

200 ng of GCase was incubated in the presence or absence of Nb1, Nb4 or Nb9 (5X molar excess) for 30 minutes on ice in a total volume of 15 µL of assay buffer consisting of 50 mM MES, 1 mM DTT, 0.005% [w/v] Brij-35 pH 6.0. Next, 150 ng of recombinant human cathepsin L (R&D systems, 952-CY) was added in a total volume of 30 µL. The solution was incubated for 1 h at 37 °C before adding 10 µL of 4× SDS loading buffer to stop the reaction. Samples were then analyzed on SDS-PAGE and gels were stained with Coomassie blue. Gels were scanned using the Amersham ImageQuant 800 (Cytiva), and the bands were quantified using the ImageQuant TL analysis software.

Structure determination and analysis

Imiglucerase (Cerezyme®) was partially deglycosylated prior to crystallization as previously described50. Crystals of this protein in complex with Nb1 were obtained by co-crystallization using the sitting-drop vapor diffusion method at 277 K. GCase (Imiglucerase) and Nb1 proteins were mixed to obtain a concentration of 10 mg/mL and 3.5 mg/mL respectively (1:1.2 molar ratio). Crystals were obtained in a crystallization solution of 1.6 M Magnesium sulfate heptahydrate, 0.1 M MES pH 6.5. Crystals were cryo-protected in mother liquor supplemented with 25% glycerol.

Data were collected at 100 K at the Proxima 2 beamline of the Soleil synchrotron (λ = 0.9801 Å), to a resolution of 1.7 Å. Diffraction data were integrated and scaled with autoPROC83, using the default pipeline including XDS, Truncate, Aimless, and STARANISO. Crystal belonged to the tetragonal space group I422. The structure was solved using the molecular replacement method based on PDB 2J25 for GCase and 7A17 (chain B) for Nb1, and refined with the phenix.refine module (Phenix version 1.20.1)84 alternated with manual building in Coot85. Supplementary Table S1 summarizes data collection, processing and refinement statistics. Structure and structure factors were deposited in the PDB (code 9ENA). All structural figures were produced with PyMOL (The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 2.3.3, Schrödinger, LLC.).

Cell culture, plasmids and transfection

Human embryonic kidney cells (HEK293T, ATCC CRL-3216) and human fibroblast cells (Cell line and DNA biobank from patients affected by genetic diseases” (Istituto G. Gaslini), and “Parkinson Institute Biobank” (Milan, http://www.parkinsonbiobank.com/) members of the Telethon Network of Genetic Biobanks funded by Telethon Italy, (http://www.biobanknetwork.org, project No. GTB12001)86 were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Sigma Aldrich), supplemented with fetal bovine serum (FBS, 10% Sigma Aldrich) and 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Sigma Aldrich) at 37 °C and 5% CO2. For transient transfection, polyethyleneimine (PEI) was used as a transfection reagent and HEK293T cells were incubated with DNA:PEI (1:2) in OPTIMEM (Life Technologies) for two hours, before media change. After 48 h, activity assays, western blotting analyses or imaging experiments were performed.

Mice colony

Gba1−/− hN370S mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratories (https://www.jax.org/strain/032791). Mouse genotyping was performed with WONDER Taq Hot START (Euroclone) using the following primers: 5′-TCCTCACCTCCTCAGATGCT-3′ (mutant forward), 5′-ACCCTCGGGTTTTAAGCTG-3′ (mutant reverse), 5′-CTCTGCAGTTGTGGTCGTGT-3′ (wild-type forward), 5′-GTCCATGCTAAGCCCAGGT-3′ (wild-type reverse), 5′-CTG TCC CTG TAT GCC TCT GG-3′ (Internal Positive Control Forward), 5’-AGATGGAGAAAGGACTAGGCTACA-3′ (Internal Positive Control Reverse), 5′-CAG CCA TGA TGC TTA CCC TAC-3′ (Transgene Reverse), 5′-GCT AAC CAT GTT CAT GCC TTC-3′ (Transgene forward).

Measurement of GCase activity in live cells

A selective lysosomal GCase substrate, 5-(Pentafluorobenzoylamino) Fluorescein Di-β-D-Glucopyranoside (PFB-FDGlu, P11947 ThermoFisher Scientific) was used to evaluate GCase activity in live cells. HEK293T cells were cultured in a 24-well plate (150000 cells/well) and transfected with mCherry plasmids (1 µg DNA/well). After 48 h, PFB-FDGlu (50 µg/mL) was added for 6 h and the nPFB-FDGlu fluorescence was measured by BD FACSAria™ III Cell Sorter (BD Biosciences) (λex 492 nm and λem 516 nm).

The same assay was performed also in HEK293T cells transfected with the different Nbs and treated with the GCase inhibitor CBE (15216 Cayman Chemical, 50 µM) for 24 h to evaluate potential off-target hydrolysis (Supplementary Fig. S12A).

GCase activity was also evaluated in GBA1 knockdown HEK293T (11 F clone) overexpressing the N370S GCase mutant. Briefly, the cells were cultured in 24-well plate (150000 cells/well) and were co-transfected with mCherry plasmids (Mock, Nb1, Nb4, and Nb9) and pCMV3_ N370S_His plasmid encoding the N370S GCase mutant (1 µg DNA/well).

After 48 h, PFB-FDGlu (50 µg/mL) was added for 6 h and the PFB-FDGlu fluorescence was measured by BD FACSAria™ III Cell Sorter (λex 492 nm and λem 516 nm). Non-transfected wild-type and GBA1 knockdown cells were used as controls.

In all experiments we used different control samples to define the gating strategy and set up the instrument for the experiment (Supplementary Fig. S12). In particular: non-transfected cells without PFB-FDGlu treatment to select non fluorescent population (unstained cells); non-transfected cells treated with the PFB-FDGlu substrate were considered to identify the fluorescent population (ctrl); and transfected cells without the PFB-FDGlu substrate treatment to select the population expressing Nanobodies (+mCherry). Concerning the gating strategy, a first dot plot (FSC-A/SSC-A) was used to select the population of interest, a second and third dot plot to select single cells, and a fourth dot plot (FSC-A/PE) to identify transfected cells (mCherry+ with PE fluorescence >103). Finally, a histogram with fluorescence intensity (FITC) on the x-axis and events on the y-axis was used to evaluate PFD-Glu fluorescence, ( = the GCase activity), in transfected cells (mCherry+) (Supplementary Fig. S12B).

Measurement of GCase activity in cell or tissue lysates

GCase activity was measured in HEK293T transfected with different ER- or lysosomal targeting Nbs by using the 4-methylumbelliferyl-β-D-glucopyranoside (4-MU) assay. Cells were cultured in a 12-well plate (300000 cells/well) and transfected with eGFP plasmids (2 µg DNA/well). After 48 h, cells were lysed in RIPA buffer supplemented with protease inhibitors (Roche) and protein was quantified by Pierce® Bicinchoninic acid (BCA) Protein Assay Kit assay.

As for tissues, they were isolated from 8-month-old GBA1−/− hN370S transgenic mice and stored at −80 °C. Then, tissues were lysed in RIPA buffer (ratio 1:4) supplemented with protease inhibitors (Roche) and protein was quantified by BCA Protein Assay Kit assay.

Cell lysate samples were prepared in citrate phosphate buffer pH 4.5 (0.1 M Citric Acid, 0.2 M Na2HPO4) (20 µL, 2 µg of protein) and incubated with the 4-MU substrate (3 mM in citrate phosphate buffer with 0.2% taurocholate) for 90 min at 37 °C. Tissue lysates were prepared in the same manner but they were preincubated with Nbs (2.5 µM) for 30’ at 37 °C before starting the incubation with the substrate. The reaction was stopped by adding 240 µL of stop buffer (0.2 M NaOH, 0.2 M Glycine pH 10). Fluorescence was measured in a fluorescence microplate reader (Victor X3, Perkin Elmer). The assay was performed in triplicate.

Western blot analysis

HEK293T cells were cultured in a 12-well plate (300000 cells/well) and transfected with eGFP plasmids (2 µg DNA/well). After 48 h, cells were lysed in RIPA buffer supplemented with protease inhibitors cocktail (Roche). Lysates were centrifuged at 20,000 × g at 4 °C. Protein concentration was determined using the Pierce® BCA Protein Assay Kit. Equal amounts of protein were loaded on gradient gel 4–20%. Tris-MOPS-SDS gels (GenScript). The resolved proteins were then transferred to PVDF membranes (BioRad), through a semi-dry Trans Blot® TurboTM Transfer System (BioRad). PVDF membranes were blocked in Tris-buffered saline plus 0.1% Tween (TBS-T) and 5% non-fat dry milk for 1 h and then incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies diluted in TBS-T plus 5% non-fat milk. The following primary antibodies were used: mouse anti- β-actin (1:10000, A2066 Sigma-Aldrich), rabbit anti-calnexin (1:1000, ab22595 Abcam), mouse anti-LAMP1(1:400, sc-20011 Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-FLAG HRP (1:1000, A8592 Sigma-Aldrich), rabbit anti-Glucocerebrosidase (C-terminal) (1:1000, G4171 Sigma-Aldrich). After incubation with horse-radish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies (goat anti-rabbit-HRP and goat anti-mouse-HRP, Sigma-Aldrich) at room temperature for 1 h, immunoreactive proteins were visualized using Immobilon® Classico Western HRP Substrate (Millipore) or Immobilon® Forte Western HRP Substrate (Millipore) by Imager CHEMI Premium detector (VWR). The densitometric analysis of the detected bands was performed by using the IMAGE J software.

Lysosomal proteolytic activity