Abstract

Embryonic tissues undergo coordinated flows during avian gastrulation to establish the body plan. Here, we elucidate how the interplay between embryonic and extraembryonic tissues affects the chick embryo’s size and shape. These two distinct geometric changes are each associated with dynamic curves across which trajectories separate (kinematic repellers). Through physical modeling and experimental manipulations of both embryonic and extraembryonic tissues, we selectively eliminate either or both repellers in model and experiments, revealing their mechanistic origins. We find that embryo size is affected by the competition between extraembryonic epiboly and embryonic myosin-driven contraction—which persists when mesoderm induction is blocked. Instead, the characteristic shape change from circular to pear-shaped arises from myosin-driven cell intercalations in the mesendoderm, irrespective of epiboly. These findings elucidate modular mechanisms controlling avian gastrulation flows and provide a mechanistic basis for the independent control of embryo size and shape during development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Morphogenesis requires spatiotemporal coordination of hundreds of thousands of cells to sculpt a developing embryo1,2. Elucidating the principles of morphogenesis, spanning mechanisms from molecular to organismal scales, is a grand challenge for developmental biology and the physics of living systems3,4,5,6,7. Tackling this challenge requires experimental advances and theoretical progress on two fronts: i) developing predictive biophysical models to test hypotheses8,9,10,11,12 and ii) devising mathematical methods to extract key insights from experimental data13,14,15,16,17. Progress in i and ii have largely remained independent. Here, we combine mathematical methods characterizing the robust features of cumulative tissue deformation, biophysical modeling and experimental perturbations to elucidate how the avian embryo controls its dynamic geometry during gastrulation.

Recent imaging advances enable tracking single-cell trajectories18,19, or, at the tissue level, spatiotemporal velocities describing the collective motion of cells20,21,22. However, analyzing noisy cell motion data over evolving domains can be overwhelming rather than informative. To this end, it is useful to identify robust kinematic structures. For example, given a measured ocean surface velocity field, one might be interested in understanding where floating objects accumulate or separate without knowing the precise forces generating the flows. This challenge led to the development of Lagrangian Coherent Structures23,24, now widely adopted in science and engineering25,26,27. These are based on Lagrangian trajectories (e.g., cumulative tissue deformations) as opposed to Eulerian (or instantaneous) velocity fields, strain rates etc. (Supplementary Fig. S1 and S2). Given a velocity field over a time interval, Lagrangian Coherent Structures are dynamic curves (in 2D) and surfaces (in 3D) that organize complex trajectories. In morphogenesis, the Dynamic Morphoskeleton (DM) identifies attracting and repelling Lagragian Coherent Structures28 (SI Sec. S1), revealing where cells maximally converge or separate over a developmental time interval of interest—dynamic ‘attractors’ and ‘repellers’ (Supplementary Fig. S1). These are attractors and repellers in the dynamical systems sense, not to be confused with causative factors like chemoattractants. The DM in chick28,29,30, fruit fly28, and zebrafish18 embryos identified early footprints of known morphogenetic features and new ones. Repellers, in particular, were previously undocumented despite their potential relevance in dynamic tissue patterning18,31,32.

We focus on avian gastrulation, a crucial process in early development during which a flat sheet of approximately 60,000 cells breaks symmetry, setting the vertebrate body axes and forming the three germ layers (endoderm, mesoderm, and ectoderm). At the onset of gastrulation (t0, stage HH1), avian embryos consist of a circular monolayer of suspended epithelial cells, the embryo proper (EP), surrounded by an annulus of extraembryonic tissue (EE)33,34,35 (Fig. 1A). Initially, mesendoderm precursor cells are in a sickle-shaped region in the posterior EP. Over the next 15 h, these mesendodermal progenitors converge and extend along the midline, undergoing individual cell ingression and forming the primitive streak (PS). This convergent extension is driven by active intercalation, apical constriction, and ingression36,37,38,39 (Fig. 1A). These processes generate complex, embryo-scale coordinated cell movements and macroscopic vortical flows in the EP. Simultaneously, the EE expands outward (epiboly), powered by the active edge cell crawling on the vitelline membrane (Fig. 1A). The DM provides a concise summary of the complex cell movements during avian gastrulation: one line attractor and two repellers (Fig. 1B,28). The Attractor marks the PS, and its domain of attraction identifies the sickle-shaped region of mesendoderm cells that will ingress into the PS. Repeller 1 (R1) identifies the boundary where EP and EE regions separate. Repeller 2 (R2), bisecting the domain of attraction, identifies where anterior and posterior mesendoderm cells separate. See Supplementary Fig. S2 for Eulerian fields such as velocities and strain rates and their connection with the DM and other Lagrangian quantities.

A Avian morphogenesis involves convergent extension of the presumptive mesendoderm to form the primitive streak (PS), shape change of the embryo proper (EP), and extraembryonic (EE) expansion driven by edge cells (EC) crawling on the vitelline membrane. Myosin activity drives isotropic apical constriction throughout the EP and directs mesendoderm intercalations. Mesendoderm cells actively ingress at the PS, marking the anterior-posterior (A-P) axis. Cyan in insets marks elevated myosin activity. B The Dynamic Morphoskeleton of avian gastrulation. Repellers (R1 and R2) mark initial (t0) locations of cells that maximally separate by final time tf.The Attractor marks final (tf) locations where cells maximally converge during [t0, tf]. The domain of attraction marks the initial cell positions that converge to the Attractor. R1 lies on the EP-EE boundary, R2 bisects the presumptive mesendoderm, and the Attractor marks the PS. C–E Active nematic tensor dynamics (Eq. (1c)). C Flow coupling: Actomyosin cables (cyan nematic elements) reorient and align passively with the local flow (black). Vorticity rotates (left), while shear can rotate and both increase (middle) or decrease (right) nematic order. D Actomyosin cables align active junctions through mechanosensitive myosin redistribution, increasing nematic order. E Nematic order passively relaxes without activity or flow, decreasing nematic order.

We previously developed a minimal 2D continuum model coupling active stresses and tissue motion, finding that avian gastrulation flows arise from a mechanosensitive active stress instability, confirmed by experiments30. This model demonstrated that changing the initial mesendoderm pattern and a parameter associated with active ingression can reshape the Attractor. Model predictions matched experiments, showing that the Attractor of chick gastrulation flows can be altered to recapitulate other vertebrate gastrulation modes, i.e., their tissue flows, attractor geometries and internalization mechanisms29,30,40. This study, instead, investigates the origin of dynamic EP geometry (i.e., the EP-EE boundary)—specifically how the interplay between EP and EE tissues affects embryo size and the long-recognized embryo shape change from circular to pear-shaped35,41, missing a mechanistic explanation in existing models30,42,43. Our previous model30 cannot address questions of size or shape because it enforces a fixed circular EP domain, also limiting prediction and mechanistic investigation of the two associated repellers.

In this work, our model accounts for the motion and distinct myosin dynamics of both EP and EE regions, and allows for the creation and destruction of actomyosin cables. These new features predict force distributions at the EP-EE boundary, resulting in the observed size regulation of the EP region and its characteristic shape change. Combining modeling and novel experiments to symmetrically block epiboly, we find that EP size depends on the balance of myosin-driven apical constriction in the EP and pulling by EE epiboly. Surprisingly, EP size control persists when mesoderm induction is blocked. Embryo shape change, instead, arises from active intercalation driven by myosin cables in the mesoderm—even without epiboly. Our results show that chick embryo size and shape can be independently controlled. These modular tissue-scale mechanisms complement genetic modularity44,45 and the modularity of specific cell behaviors46, helping to rationalize how distinct embryo features emerge from coordinated cell behaviors.

Mathematical Model

During avian gastrulation, embryonic cells frequently exchange neighbors, effectively behaving as a viscoelastic or viscous, compressible fluid deformed by active forces30,42,43,47. Actomyosin cables spanning 6-8 cells generate active stresses39, driving directed cell intercalations36,37,38. We previously quantified the intensity and orientation of myosin activity30 and modeled actomyosin cables as contractile nematic elements. In30, myosin activity generates active stresses that drive tissue flows, altering active stress patterns. This continuum model is computationally fast, interpretable, and uses fewer parameters than more microscopic approaches48,49. Using fixed parameters, the model predicts EP gastrulation flows, specifically their attractors in wild-type (WT) and perturbed embryos30.

This previous model, however, has limitations. First, it enforces a fixed circular EP and no EE tissue. These preclude predictions of embryo shape change35 and repellers, which are prominent in avian morphogenesis (Fig. 1B). Second, it precludes modeling relevant distinct EP-EE dynamics. Third, it assumes that all cables are perfectly aligned with the local average orientation ϕ. Here, we explicitly account for the EE tissue, which immunostaining shows to be largely devoid of myosin activity30. To account for the differing degrees of cable alignment (i.e., the presence or absence of aligned actomyosin cables), we model a nematic order parameter s, which modulates anisotropic active stress ∝ mQ, where \({\bf{Q}}=s/2[\cos 2\phi,\sin 2\phi ;\sin 2\phi,-\cos 2\phi ]\) is the nematic tensor and m is the local fraction of available myosin generating active stress (Sec. S2.1). The s dynamics, absent in the previous model, depend on flow coupling, active cable formation, and passive relaxation, enabling the creation, evolution and destruction of actomyosin cables (Fig. 1C–E, Sec. S2.2), as observed in experiments. Eq. (1) summarizes our model:

where Dd and W are the deviatoric strain rate and vorticity tensors, and pi are non-dimensional parameters (Sec. S2.5). In Eq. (1a), p1 is the ratio of active stress to the characteristic viscous bulk stress and p2 is the ratio of shear to bulk tissue viscosities. Eq. (1b) describes the dynamics of m, the fraction of locally available myosin generating active stresses in (1a) (Sec. S2.1). p3 is the ratio of gastrulation’s characteristic timescale (tc ≈15 h) to the cumulative timescale for converting all available myosin into tissue-scale active stress (Sec. S2.1). p4 is the ratio of myosin tissue-scale activation to deactivation timescales. p5 is the mechanosensitivity of the deactivation rate to cable tension30, which results in an active stress instability and reflects the exponential decrease observed in single-molecule experiments50,51. This active stress instability ensures the divergent behavior of EP and EE regions, consistent with experiments (Fig. 2E, Sec. S2.1, Fig. S3A and Fig. S9). p6 is the ratio of mechanical (or tension-induced) propagation of myosin activity along the cables to transport via advection30. The first three terms in Eq. (1c), standard in active nematics52,53,54, account for transport and flow-induced effects on Q (Fig. 1C). Notably, with only flow coupling and advection, convergent extension invariably destroys initial cable alignment, driving s to 0 in the vicinity of the streak (Fig. S3C, Sec. S2.2), inconsistent with experiments (Fig. 1 of30) and reflecting the loss of aligned high-myosin junctions from executing sequential cable contractions55,56. To sustain convergent extension, an alignment mechanism is needed to counteract order destruction from self-induced flows (Fig. S3D). The active alignment term (p7mQ) models actomyosin cable formation as an active process, conserving myosin but polarizing active stress to represent redistribution of myosin to junctions already under higher tension due to myosin activity38,39,57,58 (Fig. 1D). This agrees with experimental observations that myosin cables favor asymmetric stress propagation and that their formation can be inhibited by myosin inhibitors, as well as the hypothesis that they acquire their super-cellular alignment through a self-organizing stress-dependent mechanism38. It also reflects in the continuum setting a mechanism recently explored in vertex models, with local tension feedback redistributing myosin to increase anisotropy while conserving m49,56,59. By contrast, passive relaxation ( − p7s2Q) reduces s accounting for cell shape rigidity and random intercalations56,59,60 which would bring the tissue to an isotropic state (Fig. 1E). p7 is tc times the activity-induced alignment and passive relaxation rate (Sec. S2.5). Active alignment and passive relaxation terms, introduced in active nematics52,61, are yet unexplored in the context of morphogenesis.

A Initial distribution of myosin activity m with orientation ϕ (white director field). Director lengths increase with s (exponentially to ease visualization). White circle marks the initial EP-EE boundary, updated at later times (B–D, F) by advection with the model v. B, C Final time (tf) distribution of isotropic (B, color bar m) and anisotropic (C, color bar ms with directors as in A) myosin activity. A–C share the color bar. D Predicted model velocity v and divergence ∇ · v at the final time (tf). All model quantities are dimensionless. E Confocal image of a representative section of an HH4 stage WT chick embryo at the position indicated on the left. Staining for actin (phalloidin, red) and doubly phosphorylated myosin light chain (cyan) in the embryo. F, G Deformed Lagrangian grids and final EP-EE boundary in model (F) and experiment (G). G Experimental grid overlaid on a bright-field image of an HH4 embryo, with EP-EE boundary located by drawing an initial polygon around R1 (Sec. S5.4) and advecting it with experimental v. H, I Repellers (R1 and R2) in model (H) and experiment (I), marked by ridges of \({\atop2}{\lambda }_{{t}_{0}}^{{t}_{f}}({{\bf{x}}}_{0})\) normalized by the spatial maximum, and displayed on the initial undeformed configuration (Sec. S1). A, P labels mark the anterior-posterior axis. See Supplementary Movie 1 for the WT model velocity, velocity divergence, isotropic and anisotropic stresses, active forces, repellers, attractors, and Lagrangian grids over time. Movie repellers and attractors colorbars are normalized over their spatiotemporal maxima, achieved at tf = HH4.

As boundary conditions in Eq. (1a), we prescribe an outward normal velocity ve consistent with observed migrating edge cells (Sec. S2.6, Fig. S462). For Eqs. (1b-1c) we impose no flux for m and Q. For the initial condition of Eq. (1b), we use immunostaining data indicating minimal myosin activity in the interior EE throughout gastrulation, while myosin activity increases over time in the EP (Figs. 1E, S10 in30 and Fig. S9), consistent with an m instability (Fig. S3A, Sec. S2.1). To account for the distinct myosin dynamics of EP-EE cells, we set m(xEP, t0) > m* and m(xEE, t0) < m* where m* is the unstable uniform fixed point in the myosin dynamics (1b) (Supplementary Fig. S3A). Additionally, we initialize higher myosin activity in the posterior EP, matching the sickle shape of mesendoderm precursors29,30 (cf. scalar field in Fig. 2A). For the initial condition of Eq. (1c), we set ϕ(x, t0) along the tangential direction, matching experimental observations30, and determine the initial nematic order from m(x, t0):\(s({\bf{x}},{t}_{0})=\sqrt{m({\bf{x}},{t}_{0})}\), the equilibrium of Eq. (1c) before the onset of flows (Sec. S2.2). This reflects the expectation that a mild tangential cable alignment is amplified by active contraction and myosin redistribution in the mesendoderm precursor region (Fig. 2A) in line with experiments30,38. For details on boundary and initial conditions and the numerical scheme, see Sec. S2.6–S2.8.

Results

Model predicts repellers and embryo shape change

Solving Eq. (1), with the above initial and boundary conditions, we recapitulate avian gastrulation flows, including their characteristic Eulerian features: dynamic active stress patterns (Fig. 2A−C), vortices, and convergent-extension flows (Fig. 2D); and Lagrangian features: R1, R2, and EP shape change (Fig. 2F, H). See Supplementary Movie 1 for the time evolution of these fields and Fig. S6 for shape quantification. Figure 2B and C show increased EP myosin activity (m(x, tf)) and increased anisotropic activity along cables (m(x, tf)Q(x, tf)), consistent with experiments30. Figure 2D shows velocity and velocity divergence at final time tf = stage HH4 consistent with observations of sustained vortical flows, negative divergence in the PS (Attractor), lower divergence magnitude in the rest of the EP and positive divergence in the EE region30,38 (Fig. S7). Immunostaining of HH4 embryos confirms high active myosin in the EP and low in the EE (Fig. 2E), consistent with our previous work30.

To assess Lagrangian features, Fig. 2F shows an initially uniform grid and circular EP-EE boundary (Fig. 2A) advected with the model velocity (v), showing lower expansion of the EP relative to the substantial stretching of the EE55. With the EP-EE boundary now free to deform, the model also successfully predicts the EP’s long-recognized geometric transformation from circular to pear-shaped35,63 (also plotted in Fig. 2B–D, F). This nontrivial aspect requires the correct self-organizing dynamics of active forces (Movie 1 and Sec. S3.1) on the EP boundary, internal points of our modeling domain. Figure 2H shows the repellers in the highest Lagrangian stretching field \({\atop2}{\lambda }_{{t}_{0}}^{{t}_{f}}({{\bf{x}}}_{0})\), displayed at the embryo’s initial configuration28. Throughout, \({\atop2}{\lambda }_{{t}_{0}}^{{t}_{f}}({{\bf{x}}}_{0})\) denotes the largest singular value field of the deformation gradient tensor \({{\mathbf{\nabla }}}_{{{\bf{x}}}_{0}}{{\bf{F}}}_{{t}_{0}}^{{t}_{f}}({{\bf{x}}}_{0})\), where \({{\bf{F}}}_{{t}_{0}}^{{t}_{f}}({{\bf{x}}}_{0})\) denotes trajectories from t0 to tf starting at x0 (Sec. S1). High values of \({\atop2}{\lambda }_{{t}_{0}}^{{t}_{f}}({{\bf{x}}}_{0})\) mark initial embryo locations (repellers R1 and R2) where nearby cells maximally separate by tf (Fig. S1). To visualize these repellers (constituting the DM), we normalize \({\atop2}{\lambda }_{{t}_{0}}^{{t}_{f}}({{\bf{x}}}_{0})\) by its maximum. The model reproduces the circular arcs of R1 at the EP-EE boundary and R2 in the posterior28 (c.f. Fig. 1B). Altogether, these results showcase the model’s predictive capability, providing only the initial myosin intensity (m(x, t0)), cables distribution (Q(x, t0)), and epiboly velocity as inputs.

To test our model and explore perturbations, we developed an imaging and analysis pipeline using bright-field microscopy, enabling us to simultaneously track tissue flows in up to ~16 chick embryos without fluorescent labels (Fig. S5). This approach demonstrates the robustness of the DM across several embryos, despite the intrinsic variability of their tissue flows (Fig. S8). Representative Lagrangian deformation (Fig. 2G) and repellers (Fig. 2I) from this pipeline are consistent with model predictions (Fig. 2F, H). Importantly, our goal is not to precisely match the DM between the model and a specific experiment by fitting parameters—this would depend on specific experiments. Instead, we aim to predict the existence and average geometry of repellers, which are robust across experiments (Fig. S8).

Origin and elimination of Repeller 1

We next investigate the mechanisms underlying R1. Edge cells adhering to the vitelline membrane crawl outwards, pulling the EE and EP radially (Fig. 1A). Edge cells crawling rates are nearly constant and robust to several treatments, including excision of the EP64,65,66, justifying our boundary condition for the velocities in the model (Sec. S2.6). Epiboly contributes to global tension62,67,68 that propagates to the EP, as severing the EP-EE boundary causes both regions to contract68. Yet, R1 shows that EP and EE cells separate, implying distinct expansion rates. Tension can arise from passive stretching and active contractility. We hypothesize that the EP resists epiboly-driven expansion with isotropic myosin activity (Figs. 1A, 2A, B, E), which constricts cells’ cortical cytoskeletons (active contractility), allowing them to bear the isotropic tension contributed by epiboly without stretching like EE cells. Isotropic myosin activity can constrict cells via circumferential purse-string contraction69 or medial apical network contraction70,71 (Fig. 1A). Before the onset of motion, apical areas in the EP are already slightly smaller in the embryo and smallest in the posterior38,72, consistent with elevated myosin activity. As gastrulation proceeds, EP tissue thickens, and apical cell areas decrease62,72. Decreasing EP cell areas accompany the marked rise in EP myosin activity, with the greatest shrinkage near the PS where myosin activity grows highest38,72. In contrast, EE cells, devoid of active myosin (Fig. 2E), stretch thin, and their cell areas can increase more than double72,73. These distinct EP-EE dynamics are consistent with the model’s active stress patterns and cumulative deformation (Fig. 2A, B, F).

To test our hypothesis that R1 results from the opposition between EP inward constriction and edge cell outward crawling, we first eliminated epiboly in the model (ve = 0), solving Eq. (1) with the same parameters, initial and boundary conditions as in Fig. 2. Eliminating epiboly dramatically weakens differential EP-EE expansion and effectively eliminates R1 relative to R2 and EP shape change, which are not substantially altered (Figs. 3A, B, E, G). Eliminating isotropic myosin activity or the distinct initial distribution of myosin between the EP and EE (m(x, t0)) is also sufficient to eliminate R1 in the model (Sec. S3), but these perturbations are experimentally infeasible. Additionally, eliminating epiboly may affect the average isotropic tension of the tissue62, reducing the rate of myosin accumulation, but any such effect is beyond the scope of our current model. To experimentally verify our prediction, we restricted epiboly movements. Past approaches to interfering with epiboly have limitations: ablating edge cells blocks epiboly only transiently as new edge cells quickly differentiate and resume epiboly67; removing the EE entirely can compromise development because of its signaling role patterning the early EP68,74; chemical treatments like colchicine also disrupt cell division75,76; and manually wrinkling the vitelline membrane68 or extracting yolk77 to reduce vitelline membrane tension only partially reduce expansion and not always uniformly. To overcome these limitations, we developed a novel technique, cauterizing the inner face of the vitelline membrane surrounding the EE using a soldering iron (Fig. 3F and Sec. S5.2). The edge cells cannot adhere to the cauterized region, creating a fixed boundary that uniformly blocks epiboly.

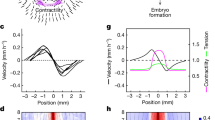

Confining the embryo eliminates R1 but preserves R2. (A, B) Predicted model velocity v and divergence ∇ · v at t0 (A) and tf (B), with ve = 0 reflecting embryo confinement. C Mean and standard deviation of experimental EP and EE areas over 15 h (N = 8 per group). D Doubly phosphorylated myosin light chain (cyan) and actin (phalloidin, red) in a representative section of a confined embryo. E, F Deformed Lagrangian grids and final EP-EE boundary in model (E) and experiment (F). Experimental Lagrangian grid overlaid on the bright-field image of a confined HH4 chick embryo, boundary located as in Fig. 2. Embryo confined in experiments by cauterizing the EP side of the vitelline membrane. G, H Repeller (R2) in model (G) and experiment (H), marked by ridge of \({\atop2}{\lambda }_{{t}_{0}}^{{t}_{f}}({{\bf{x}}}_{0})\), normalized by the spatial maximum, and displayed on the initial undeformed configuration. Compare (G, H) with the corresponding WT Fig. 2H, I. A, P labels mark the anterior-posterior axis. Supplementary Movie 2 shows the time evolution of Lagrangian and Eulerian model fields as in Supplementary Movie 1.

This confinement technique is compatible with our high-throughput live imaging pipeline (Fig. S5). Figure 3C confirms that confinement prevents embryo expansion and that the marked difference in EE-EP expansion observed in the WT embryo (blue curves) has been reduced (orange curves). Immunostaining of phosphorylated (active) myosin verifies persistent active contractility across the EP under confined conditions (Fig. 3D and Fig. S9). A representative Lagrangian deformation grid of the confined embryo (Fig. 3F) shows lesser differential EP-EE stretching than WT (Fig. 2G) and that the embryo still becomes pear-shaped (Fig. 3F, and Suppl. Fig. S6) and forms a PS (Fig. S11B). Figure 3H indicates the presence of R2 but no R1 (compare with Fig. 2I), consistent with model predictions (Fig. 3G). We find that the confined embryos develop well past gastrulation stages in these conditions (Fig. S10), suggesting that epiboly may be unnecessary at gastrulation stages (Discussion and Sec. S4). These results suggest that R1 arises from a tug-of-war between EE epiboly and EP active constriction. Without epiboly, no substantial separation occurs at the EP-EE boundary.

Origin and elimination of Repeller 2

Preserving R2 without R1 suggests that avian gastrulation’s repellers may arise from independent mechanisms. We hypothesize that R2, bisecting the initial crescent-shaped mesendoderm, results from actomyosin cable-directed intercalations in this region38,39, independent of epiboly and EP constriction associated with R1. To test our hypothesis, we eliminated the model mesendoderm, represented by elevated posterior myosin activity and anisotropy, solving Eq. (1) with the same parameters, initial and boundary conditions as in WT. This also eliminates the initially elevated posterior cable anisotropy associated with active alignment (Fig. 2A, Sec. S2.7). With this change, the EP remains circular and retains differential EP-EE expansion (Figs. 4A, B, E). Figure 4G shows the elimination of R2, but R1 remains and becomes circularly symmetric due to the retention of epiboly and uniform isotropic active stress in the EP. Eliminating anisotropic active stress or active cable formation (p7 = 0) is also sufficient to eliminate R2 (Sec. S3).

Blocking mesendoderm induction eliminates R2 but preserves R1. A, B Predicted model velocity v and divergence ∇ · v at t0 (A) and tf (B). Model results obtained solving Eq. (1) with uniform initial EP myosin reflecting the absence of mesendoderm. C Mean and standard deviation experimental EP and EE areas over 15 h (N = 4 per group). D Doubly phosphorylated myosin light chain (cyan) and actin (phalloidin, red) in a representative section of a treated embryo. E, F Deformed Lagrangian grids and final EP-EE boundary in model (E) and experiment (F). Experimental grid overlaid on bright-field image of a treated HH4 chick embryo, boundary located as in Fig. 2. Mesendoderm induction blocked in experiments using 1μM LY2874455, a pan-FGF receptor inhibitor. G, H Repeller (R1) in model (G) and experiment (H), marked by ridge of \({\atop2}{\lambda }_{{t}_{0}}^{{t}_{f}}({{\bf{x}}}_{0})\), normalized by the spatial maximum, and displayed on the initial undeformed configuration. Compare (G, H) with the corresponding WT Fig. 2H, I. Supplementary Movie 3 shows the time evolution of model fields as in Supplementary Movie 1. Movie attractor colorbar is normalized using the WT spatiotemporal maximum to emphasize the relative lack of deformation (see Supplementary Fig. S11 for a full comparison of different treatments). I, J Experimental data for circular mesoderm (FGF treatment) in unconfined (I) and confined (J) conditions. Colorbars as in G, showing \({\atop2}{\lambda }_{{t}_{f}}^{{t}_{0}}({{\bf{x}}}_{f})\) (attractors, left) and \({\atop2}{\lambda }_{{t}_{0}}^{{t}_{f}}({{\bf{x}}}_{0})\) (repellers, right) normalized by the spatial maximum.

We previously showed that oriented cell intercalation and oriented myosin cables are characteristic properties of the mesendoderm cells29. Indeed, using a pan-FGF receptor inhibitor LY287445578 completely blocks mesendoderm formation and the oriented cell intercalation associated with PS formation28,29. To verify our model prediction, we experimentally blocked mesendoderm formation using the same chemical treatment (LY2874455 1μM). Fig. 4C demonstrates that this treatment leaves the EP and EE areal expansions unaltered compared to WT. Further, immunostaining of treated embryos shows that elevated phosphorylated myosin in the EP is not affected by the FGF inhibition (Fig. 4D). Consistent with model results, the embryo retains a circular geometry (Fig. 4F, Supplementary Fig. S6), keeping R1, which becomes circularly symmetric, while eliminating both R2 and the Attractor (Figs. 4H, and Supplementary Fig. S11C). These results suggest that R1 arises from distinct mechanisms, independent of those jointly generating R2 and the Attractor. They also suggest that elevated EP actomyosin activity represents an inherent property of the EP, not requiring mesendoderm induction. Instead, induction is only required to assemble anisotropic cables perpendicular to the midline and execute the directed intercalations that contribute to forming the PS and embryo shape change.

Mesoderm is necessary for both R2 and the Attractor. These co-occur in WT chick development because the crescent-shaped mesoderm’s motion into the PS requires convergent extension, contributing to both R2 and a linear attractor (Sec. S3.2). To test the role of mesoderm geometry, we used FGF to generate a circular mesoderm domain, resulting in circular myosin cables29,79. In the model and experiments, this circular geometry results in convergence towards a circular attractor30, instead of an extending line attractor, reinforcing a symmetric R1 and eliminating R2 (experiments in Fig. 4I and model in Supplementary Fig. S12A). Furthermore, we show that combining FGF addition with confinement, the circular attractor persists, R2 remains absent, and circular contraction recovers a weak R1 (Figs. 4J, Supplementary Fig. S12B). This clarifies the role of mesoderm geometry in jointly generating R2 and the (line) Attractor, associated with embryo shape change.

Finally, combining embryo confinement (ve = 0) with inhibition of mesendoderm induction (uniform EP m(x, t0)), we simultaneously eliminated both repellers in the model and experiments (Fig. 5A, last column). Without epiboly and mesoderm-driven active intercalation, minimal deformation occurs, resulting in no shape change (Fig. S6), differential EP-EE expansion, or Attractor formation (Fig. S11D).

A Repellers R1 and R2 (red) can be controlled combinatorially by confining the chick embryo and inhibiting mesendoderm induction. First three columns adapted from Figs. 2–4, showing \({\atop2}{\lambda }_{{t}_{0}}^{{t}_{f}}({{\bf{x}}}_{0})\) fields normalized by their spatial maxima. Fourth column shows perturbation simultaneously confining the embryo and inhibiting mesendoderm induction in the model and experiments with \({\atop2}{\lambda }_{{t}_{0}}^{{t}_{f}}({{\bf{x}}}_{0})\) normalized by the WT spatial maximum to emphasize the lack of deformation. Supplementary Movie 4 shows time evolution of model fields associated with the fourth column. B Control of attractor shapes (dashed black) in model and experiments by modulating cells' ability to ingress (16 hr treatment with 100 nM of VEGF receptor inhibitor axitinib) and initial mesendoderm shape (50 μg/ml FGF2 on the hypoblast). See29 for experimental details. Fields show \({\atop2}{\lambda }_{{t}_{f}}^{{t}_{0}}({{\bf{x}}}_{f})\), normalized by their spatial maximum. B adapted from previous work30.

Discussion

In this study, we have identified the mechanisms and cellular behaviors underlying multicellular flow repellers during avian gastrulation and how embryos change size and shape, from circular to pear-shaped (Figs. 1, 2). Combining in-vivo experiments, active matter theory and nonlinear dynamics, we find that R1, separating EE from EP, arises from the balance between outward epiboly and active constriction of EP cells (Fig. 4) and is associated with embryo size. In contrast, embryo shape changes, PS-formation (Attractor), and R2—separating anterior and posterior mesoderm—require active intercalations by mesendoderm cells, sustained by active cable formation (Fig. 3). Furthermore, the circular symmetry of R1 in the absence of R2 (Fig. 4, and Supplementary Fig. S11) clarifies their relationship in WT (Fig. 2). With both repellers present, the EP shape change associated with R2 accentuates EP-EE separation at the lateral posterior EP edges, breaking R1’s otherwise circular symmetry. In general, the relative strength (\({\atop2}{\lambda }_{{t}_{0}}^{{t}_{f}}\) ridges) of R1 and R2 depends on the relative timing of epiboly and mesoderm-driven convergent extension (Fig. S13). See Supplementary Table 3 and Supplementary Movies 5–28 for additional model perturbations and sensitivity analysis.

Our findings were guided by the Dynamic Morphoskeleton, which summarizes noisy spatiotemporal tissue flows in discrete kinematic units (attractors and repellers, Fig. 1B)28, robust to intrinsic embryo variability (Fig. S8), owing to their cumulative (Lagrangian) nature that integrates cellular trajectories over time. Previous studies have also used instantaneous (Eulerian) quantities to analyze avian gastrulation flows, such as the strain rates29, vorticity80,81 and the Helmholtz decomposition to decouple flow rotation and compressibility42. Eulerian quantities are suitable for capturing instantaneous patterns of the velocities and their persistence or changes (Figs. 3A, B, 4A, B, and Supplementary Movies 1–4). Lagrangian analysis complements these techniques by quantifying cumulative tissue deformation while losing details of instantaneous flow patterns. The independent manipulability of R1 and R2 (Fig. 5A) and their mechanisms suggest modular properties. This resonates with the notion of morphogenetic modularity: complex systems, like developing embryos, are composed of semi-autonomous modules, modifiable without disrupting the overall system’s functionality46,82. In our recent findings, we also controlled the shape of avian gastrulation’s Attractor (Fig. 1B)29,30, modifying its wild-type line shape (PS) into a circle, dot, or thicker shorter line (Fig. 5B) by independently modulating the shape of the presumptive mesendoderm territory and the capacity of mesendoderm cells to undergo ingression. Altogether, the combinatorial elimination of repellers and alteration of attractors reveal the plasticity of the early embryo, providing insight into the evolvability of gastrulation programs40.

R1 arises from the tug-of-war between EE epibolic movements and the intrinsic active contractility of the EP. Surprisingly, when we confined embryos to eliminate epiboly while maintaining an intact EE (Supplementary Movie 29), embryos still gastrulated and developed proportioned axial structures, despite having shorter body axes (Supplementary Fig. S10). Similarly, a recent report showed that decreasing tension in the vitelline membrane delayed epiboly, resulting in a shorter body axis77. Disrupting epiboly progression in zebrafish does not prevent gastrulation but also produces a shorter body axis83,84. These findings suggest that while epiboly is crucial for nutritive functions later in development85, it is not required for the early stages of avian embryogenesis. The active contractility of the avian embryo may have evolved as a mechanism to resist the influence of epiboly, allowing the embryo to maintain its intrinsic (size-dependent) patterning mechanisms and developmental timeline. Indeed, experiments show that partial EP ablations normally require detachment of the EE from the vitelline membrane to avoid the embryo ripping apart86, suggesting that epiboly forces can pull apart a mechanically compromised EP. In contrast, R2 and the Attractor jointly reflect embryo shape changes and PS formation from an initially crescent-shaped mesoderm. In chick, initially close cells starting on opposite sides of R2 experience large separation during gastrulation (for visualization, see Fig. 3A of28), which may aid compartmentalization along the PS32. The independent origins and modular properties of these repellers provide a new perspective on the robustness and evolvability of avian gastrulation (Sec. S4).

Our non-cell-autonomous model (Eq. (1)) consists of a viscous, compressible, active nematic flow driven by EE epiboly and EP-EE distinct myosin dynamics. m generates isotropic active stress modeling active cell constrictions and ingressions, and anisotropic stresses generating active intercalations. Anisotropic active stresses arise from three key variables: cable orientation ϕ, m and order parameter s, quantifying the presence of aligned actomyosin cables, and whose dynamics involve non-standard activity-induced alignment and passive relaxation terms. These two processes capture the creation and destruction of aligned actomyosin cables, which are ubiquitous in experiments and critical for sustaining gastrulation flows. Using initial observed values of ϕ, m and scalar space- and time-independent parameters, our model accurately predicts 15 h of avian gastrulation flows and embryo shape changes. These shape changes, not explained by existing models30,42,73, are nontrivial as they require prediction of active force distribution on the EP boundary, internal points of our modeling domain (Supplementary Movies 1–4 and Sec. S3.1), dynamically shaping the embryo from a disc to a pear shape. Increasing shear viscosity, reflecting stiffer cell-cell junctions, results in poor EP shape change and disrupts vortical movements (Sec. S3), consistent with theoretical87,88,89 and experimental42,90,91 studies suggesting that division may contribute to tissue fluidity. Our model captures the dynamic tissue flows despite not explicitly modeling cell divisions or ingressions. Incorporation of these processes could enable predictions of cell area dynamics, clarify viscoelastic contributions, including mechanical signals from the rising tension contributed by epiboly, and connections to active solid models11,56,59. Likewise, explicitly modeling multiple cell types and their differentiation will be important to clarify feedback between tissue flows and concurrent dynamic tissue patterning32.

Methods

Our research complies with all relevant ethical regulations. We describe experimental data acquisition and analysis methods in SI Sec. 5. We describe methods for the numerical computation of the Dynamic Morphoskeletons in SI Sec. 1. We describe methods for the numerical simulation of the mathematical model in SI Sec. 2.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

We included lightweight experimental velocity fields describing the tissue flows described in Figures 2–5, as well as the measurements for Figure S10 and statistical analysis in the Source Data file. Additional data used in this paper are available from the corresponding authors upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The code used in this paper is available from the corresponding authors upon request.

References

Collinet, C. & Lecuit, T. Programmed and self-organized flow of information during morphogenesis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 22, 245–265 (2021).

Wolpert, L., Tickle, C. & Arias, A. M. Principles Of Development (Oxford University Press, USA, 2015).

Oates, A. C., Gorfinkiel, N., Gonzalez-Gaitan, M. & Heisenberg, C.-P. Quantitative approaches in developmental biology. Nat. Rev. Genet. 10, 517 (2009).

Lecuit, T. & Lenne, P.-F. Cell surface mechanics and the control of cell shape, tissue patterns and morphogenesis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 633–644 (2007).

Valet, M., Siggia, E. D. & Brivanlou, A. H. Mechanical regulation of early vertebrate embryogenesis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 23, 169–184 (2021).

Hallatschek, O. et al. Proliferating active matter. Nat. Rev. Phys. 5, 407–419 (2023).

Alert, R. & Trepat, X. Physical models of collective cell migration. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 11, 77–101 (2020).

Alt, S., Ganguly, P. & Salbreux, G. Vertex models: from cell mechanics to tissue morphogenesis. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 372, 20150520 (2017).

Gustafson, H. J., Claussen, N., De Renzis, S. & Streichan, S. J. Patterned mechanical feedback establishes a global myosin gradient. Nat. Commun. 13, 1–12 (2022).

Dye, N. A. et al. Self-organized patterning of cell morphology via mechanosensitive feedback. Elife 10, e57964 (2021).

Noll, N., Mani, M., Heemskerk, I., Streichan, S. J. & Shraiman, B. I. Active tension network model suggests an exotic mechanical state realized in epithelial tissues. Nat. Phys. 13, 1221–1226 (2017).

Gehrels, E. W., Chakrabortty, B., Perrin, M.-E., Merkel, M. & Lecuit, T. Curvature gradient drives polarized tissue flow in the Drosophila embryo. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 120, e2214205120 (2023).

Graner, F., Dollet, B., Raufaste, C. & Marmottant, P. Discrete rearranging disordered patterns, part I: robust statistical tools in two or three dimensions. Eur. Phys. J. E 25, 349–369 (2008).

Butler, L. C. et al. Cell shape changes indicate a role for extrinsic tensile forces in Drosophila germ-band extension. Nat. Cell Biol. 11, 859 (2009).

Blanchard, G. et al. Tissue tectonics: morphogenetic strain rates, cell shape change and intercalation. Nat. Methods 6, 458 (2009).

Etournay, R. et al. Interplay of cell dynamics and epithelial tension during morphogenesis of the Drosophila pupal wing. Elife 4, e07090 (2015).

Merkel, M. et al. Triangles bridge the scales: quantifying cellular contributions to tissue deformation. Phys. Rev. E 95, 032401 (2017).

Lange, M. et al. A multimodal zebrafish developmental atlas reveals the state-transition dynamics of late-vertebrate pluripotent axial progenitors. Cell 187, 6742–6759 (2024).

McDole, K. et al. In toto imaging and reconstruction of post-implantation mouse development at the single-cell level. Cell 175, 859–876 (2018).

Keller, P. J., Schmidt, A. D., Wittbrodt, J. & Stelzer, E. H. Reconstruction of zebrafish early embryonic development by scanned light sheet microscopy. Science 322, 1065–1069 (2008).

Krzic, U., Gunther, S., Saunders, T. E., Streichan, S. J. & Hufnagel, L. Multiview light-sheet microscope for rapid in toto imaging. Nat. Methods 9, 730 (2012).

Tomer, R., Khairy, K., Amat, F. & Keller, P. J. Quantitative high-speed imaging of entire developing embryos with simultaneous multiview light-sheet microscopy. Nat. Methods 9, 755 (2012).

Haller, G. Lagrangian coherent structures. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 47, 137–162 (2015).

Hadjighasem, A., Farazmand, M., Blazevski, D., Froyland, G. & Haller, G. A critical comparison of Lagrangian methods for coherent structure detection. Chaos 27, 053104 (2017).

Serra, M. et al. Search and rescue at sea aided by hidden flow structures. Nat. Commun. 11, 2525 (2020).

Serra, M., Sathe, P., Beron-Vera, F. & Haller, G. Uncovering the edge of the polar vortex. J. Atmos. Sci. 74, 3871–3885 (2017).

Serra, M., Lemma, L., Giomi, L., Dogic, Z. & Mahadevan, L. Defect-mediated dynamics of coherent structures in active nematics. Nat. Phys. 19, 1355–1361 (2023).

Serra, M., Streichan, S., Chuai, M., Weijer, C. J. & Mahadevan, L. Dynamic morphoskeletons in development. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 117, 11444–11449 (2020).

Chuai, M., Serrano Nájera, G., Serra, M., Mahadevan, L. & Weijer, C. J. Reconstruction of distinct vertebrate gastrulation modes via modulation of key cell behaviors in the chick embryo. Sci. Adv. 9, eabn5429 (2023).

Serra, M. et al. A mechanochemical model recapitulates distinct vertebrate gastrulation modes. Sci. Adv. 9, eadh8152 (2023).

Guillot, C., Djeffal, Y., Serra, M. & Pourquie, O. Control of epiblast cell fate by mechanical cues. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.06.24.600402 (2024).

Plum, A. M. & Serra, M. Morphogen patterning in dynamic tissues. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2025.01.04.631293 (2025).

Sheng, G. Day-1 chick development. Dev. Dyn. 243, 357–367 (2014).

Serrano Nájera, G. & Weijer, C. J. Cellular processes driving gastrulation in the avian embryo. Mech. Dev. 163, 103624 (2020).

Hamburger, V. & Hamilton, H. L. A series of normal stages in the development of the chick embryo. J. Morphol. 88, 49–92 (1951).

Voiculescu, O., Bertocchini, F., Wolpert, L., Keller, R. E. & Stern, C. D. The amniote primitive streak is defined by epithelial cell intercalation before gastrulation. Nature 449, 1049–1052 (2007).

Voiculescu, O., Bodenstein, L., Lau, I.-J. & Stern, C. D. Local cell interactions and self-amplifying individual cell ingression drive amniote gastrulation. Elife 3, e01817 (2014).

Rozbicki, E. et al. Myosin-II-mediated cell shape changes and cell intercalation contribute to primitive streak formation. Nat. Cell Biol. 17, 397 (2015).

Ferro, V., Chuai, M., McGloin, D. & Weijer, C. J. Measurement of junctional tension in epithelial cells at the onset of primitive streak formation in the chick embryo via non-destructive optical manipulation. Development 147, dev175109 (2020).

Nájera Serrano, G. & Weijer, C. J. The evolution of gastrulation morphologies. Development 150, dev200885 (2023).

Whitman, C. A rare form of the blastoderm of the chick, and its bearing on the question of the formation of the vertebrate embryo. J. Cell Sci. 2, 376–398 (1883).

Saadaoui, M., Rocancourt, D., Roussel, J., Corson, F. & Gros, J. A tensile ring drives tissue flows to shape the gastrulating amniote embryo. Science 367, 453–458 (2020).

Ioratim-Uba, A., Liverpool, T. B. & Henkes, S. Mechanochemical active feedback generates convergence extension in epithelial tissue. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 238301 (2023).

Melo, D., Porto, A., Cheverud, J. M. & Marroig, G. Modularity: genes, development, and evolution. Annu. Rev. Ecol., Evol. Syst. 47, 463–486 (2016).

Hatleberg, W. L. & Hinman, V. F. Modularity and hierarchy in biological systems: using gene regulatory networks to understand evolutionary change. In Current Topics in Dev. Biol. 141, 39–73 (Elsevier, 2021).

Montell, D. J. Morphogenetic cell movements: diversity from modular mechanical properties. Science 322, 1502–1505 (2008).

Streichan, S. J., Lefebvre, M. F., Noll, N., Wieschaus, E. F. & Shraiman, B. I. Global morphogenetic flow is accurately predicted by the spatial distribution of myosin motors. Elife 7, e27454 (2018).

Fletcher, A. G., Cooper, F. & Baker, R. E. Mechanocellular models of epithelial morphogenesis. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 372, 20150519 (2017).

Sknepnek, R., Djafer-Cherif, I., Chuai, M., Weijer, C. & Henkes, S. Generating active t1 transitions through mechanochemical feedback. Elife 12, e79862 (2023).

Veigel, C., Molloy, J. E., Schmitz, S. & Kendrick-Jones, J. Load-dependent kinetics of force production by smooth muscle myosin measured with optical tweezers. Nat. Cell Biol. 5, 980–986 (2003).

Norstrom, M. F., Smithback, P. A. & Rock, R. S. Unconventional processive mechanics of non-muscle myosin IIB. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 26326–26334 (2010).

Giomi, L., Mahadevan, L., Chakraborty, B. & Hagan, M. Banding, excitability and chaos in active nematic suspensions. Nonlinearity 25, 2245 (2012).

Doostmohammadi, A., Ignés-Mullol, J., Yeomans, J. M. & Sagués, F. Active nematics. Nat. Commun. 9, 3246 (2018).

Giomi, L., Bowick, M. J., Ma, X. & Marchetti, M. C. Defect annihilation and proliferation in active nematics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 228101 (2013).

Rozbicki, E. et al. Myosin-ii-mediated cell shape changes and cell intercalation contribute to primitive streak formation. Nat. Cell Biol. 17, 397–408 (2015).

Brauns, F., Claussen, N. H., Wieschaus, E. F. & Shraiman, B. I. The geometric basis of epithelial convergent extension. eLife 13, RP95521 (2024).

Duda, M. et al. Polarization of myosin ii refines tissue material properties to buffer mechanical stress. Dev. Cell 48, 245–260 (2019).

Fernandez-Gonzalez, R., de Matos Simoes, S., Röper, J.-C., Eaton, S. & Zallen, J. A. Myosin II dynamics are regulated by tension in intercalating cells. Dev. Cell 17, 736–743 (2009).

Claussen, N. H., Brauns, F. & Shraiman, B. I. A geometric-tension-dynamics model of epithelial convergent extension. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 121, e2321928121 (2024).

Curran, S. et al. Myosin ii controls junction fluctuations to guide epithelial tissue ordering. Dev. Cell 43, 480–492 (2017).

Ahmadi, A., Marchetti, M. C. & Liverpool, T. B. Hydrodynamics of isotropic and liquid crystalline active polymer solutions. Phys. Rev. E 74, 061913 (2006).

Downie, J. The mechanism of chick blastoderm expansion. Development 35, 559–575 (1976).

Spratt Jr, N. T. Formation of the primitive streak in the explanted chick blastoderm marked with carbon particles. J. Exp. Zool. 103, 259–304 (1946).

Futterman, M. A., García, A. J. & Zamir, E. A. Evidence for partial epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (pemt) and recruitment of motile blastoderm edge cells during avian epiboly. Dev. Dyn. 240, 1502–1511 (2011).

Downie, J. R. & Pegrum, S. M. Organization of the chick blastoderm edge. Development 26, 623–635 (1971).

Lee, H. C., Fadaili, Y. & Stern, C. D. Molecular characteristics of the edge cells responsible for expansion of the chick embryo on the vitelline membrane. Open Biol. 12, 220147 (2022).

New, D. The adhesive properties and expansion of the chick blastoderm. Development 7, 146–164 (1959).

Bellairs, R., Bromham, D. & Wylie, C. The influence of the area opaca on the development of the young chick embryo. Development 17, 195–212 (1967).

Owaribe, K., Kodama, R. & Eguchi, G. Demonstration of contractility of circumferential actin bundles and its morphogenetic significance in pigmented epithelium in vitro and in vivo. J. Cell Biol. 90, 507–514 (1981).

Lecuit, T., Lenne, P.-F. & Munro, E. Force generation, transmission, and integration during cell and tissue morphogenesis. Annu. Rev. Cell Developmental Biol. 27, 157–184 (2011).

Martin, A. C., Kaschube, M. & Wieschaus, E. F. Pulsed contractions of an actin–myosin network drive apical constriction. Nature 457, 495–499 (2009).

Serrano Nájera, G. Analysis and Modulation Of Cell Behaviours Driving Avian Gastrulation. Ph.D. thesis, School of Life Sciences, University of Dundee (2021).

Michaut, A., Chamolly, A., Villedieu, A., Corson, F. & Gros, J. A tension-induced morphological transition shapes the avian extra-embryonic territory. Curr. Biol. 35, 1681–1692.e4 (2025).

Lee, H. C., Hastings, C. & Stern, C. D. The extra-embryonic area opaca plays a role in positioning the primitive streak of the early chick embryo. Development 149, dev200303 (2022).

Downie, J. The role of microtubules in chick blastoderm expansion-a quantitative study using colchicine. Development 34, 265–277 (1975).

Mareel, M., Bellairs, R., Bruyne, G. D. & Van Peteghem, M. C. Effect of microtubule inhibitors on the expansion of hypoblast and margin of overgrowth of chick blastoderms. Development 81, 273–286 (1984).

Kunz, D. et al. Downregulation of extraembryonic tension controls body axis formation in avian embryos. 14, 3266 (2023).

Zhao, G. et al. A novel, selective inhibitor of fibroblast growth factor receptors that shows a potent broad spectrum of antitumor activity in several tumor xenograft models. Mol. Cancer Therapeutics 10, 2200–2210 (2011).

Alev, C., Wu, Y., Nakaya, Y. & Sheng, G. Decoupling of amniote gastrulation and streak formation reveals a morphogenetic unity in vertebrate mesoderm induction. Development 140, 2691–2696 (2013).

Asai, R., Prakash, V. N., Sinha, S., Prakash, M. & Mikawa, T. Coupling and uncoupling of midline morphogenesis and cell flow in amniote gastrulation. Elife 12, RP89948 (2024).

Asai, R., Sinha, S., Prakash, V. N. & Mikawa, T. Bilateral cellular flows display asymmetry prior to left-right organizer formation in amniote gastrulation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 122, e2414860122 (2025).

Klingenberg, C. P. Morphological integration and developmental modularity. Annu. Rev. Ecol., Evolution, Syst. 39, 115–132 (2008).

Solnica-Krezel, L. & Driever, W. Microtubule arrays of the zebrafish yolk cell: organization and function during epiboly. Development 120, 2443–2455 (1994).

Camacho-Macorra, C., Tabanera, N., Sánchez-Bustamante, E., Bovolenta, P. & Cardozo, M. J. Maternal vgll4a regulates zebrafish epiboly through yap1 activity. Front. Cell Developmental Biol. 12, 1362695 (2024).

Starck, J. M., Stewart, J. R. & Blackburn, D. G. Phylogeny and evolutionary history of the amniote egg. J. Morphol. 282, 1080–1122 (2021).

Psychoyos, D. & Stern, C. D. Restoration of the organizer after radical ablation of Hensen’s node and the anterior primitive streak in the chick embryo. Development 122, 3263–3273 (1996).

Ranft, J. et al. Fluidization of tissues by cell division and apoptosis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 20863–20868 (2010).

Basan, M., Prost, J., Joanny, J.-F. & Elgeti, J. Dissipative particle dynamics simulations for biological tissues: rheology and competition. Phys. Biol. 8, 026014 (2011).

Matoz-Fernandez, D., Martens, K., Sknepnek, R., Barrat, J. & Henkes, S. Cell division and death inhibit glassy behaviour of confluent tissues. Soft Matter 13, 3205–3212 (2017).

Cui, C., Yang, X., Chuai, M., Glazier, J. A. & Weijer, C. J. Analysis of tissue flow patterns during primitive streak formation in the chick embryo. Dev. Biol. 284, 37–47 (2005).

Firmino, J., Rocancourt, D., Saadaoui, M., Moreau, C. & Gros, J. Cell division drives epithelial cell rearrangements during gastrulation in chick. Dev. Cell 36, 249–261 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Dillan Saunders for insightful discussions and Alexandra Neaverson, Yuri Takahashi, Apolline Delahaye, Maciej Żurowski and Sreejith Santhosh for their input and experimental support. We also acknowledge Fridtjof Brauns for suggesting Supplementary Fig. S2. GSN acknowledges support from Leverhulme Trust Early Career Fellowship (ECF-2022-474). AP acknowledges support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under training grant number T32-GM127235. CJW acknowledges support from the BBSRC (BB/N009789/1, BB/K00204X/1, BB/R000441/1, BB/T006781/1) and the Wellcome Trust(101468/Z/13/Z). MS acknowledges support from the Hellman Foundation, NSF PHY-2413073 and NSF CAREERPHY-2443851.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.S.N. and M.S. designed the research. G.S.N. designed, performed, and analyzed experiments, with inputs from B.S. A.P. and M.S. formulated the mathematical model. A.P. performed and analyzed numerical simulations. A.P., G.S.N., C.J.W. and M.S. wrote the manuscript. C.J.W. and M.S. supervised the project.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Carl-Philipp Heisenberg and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Serrano Nájera, G., Plum, A.M., Steventon, B. et al. Control of tissue flows and embryo geometry in avian gastrulation. Nat Commun 16, 5174 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60249-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60249-8