Abstract

The oxygen isotope composition of seawater (δ18Oseawater) is shaped by high- and low-temperature rock-water interactions, reflecting Earth system’s dynamics and evolution. The history of δ18Oseawater remains debated due partly to post-depositional imprints to all current mineral proxies. The oxygen atoms in sulfate minerals are among the most inaccessible to later exchange but often not in isotope equilibrium with ambient water. However, the δ18Osulfate may reach a plateau or approach equilibrium with the δ18Oseawater as the corresponding δ34Ssulfate increases during microbial sulfate reduction. Here we show 289 paired δ18O-δ34S values for sedimentary barite spanning six periods of the Phanerozoic Eon. The δ18O-δ34S trajectories point to variable equilibrium δ18Obarite values for different periods. A ~ 4‰ lower δ18Oseawater value is evident before the Carboniferous than today if assuming the same formation temperature. Utilizing the barite δ18O-δ34S trajectory approach, we now have a robust proxy to advance the long-debated issue of seawater δ18O history.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The oxygen isotope composition of seawater (δ18Oseawater) is primarily determined by two competing geological processes: high-temperature rock-water interactions within the oceanic crust, which increases the δ18Oseawater value, and low- or surface-temperature interactions on land and oceanic crust, which decreases the value1,2,3. Active plate tectonics may have maintained the δ18Oseawater at its current value of 0‰ because the fluxes of these two processes may have reached steady state over much of Earth’s history based on the investigation of oxygen isotope compositions of ancient oceanic crusts (i.e., ophiolite data)3,4,5,6,7,8. However, this steady-state may be disrupted by changes in the thickness of the oceanic crust or seawater depth2,9,10. An increase of seawater δ18O value throughout the geological history is supported by δ18O proxies of various marine sedimentary minerals (e.g., carbonate minerals11,12, chert13, phosphate14, and iron oxides15,16) and ophiolites17,18,19. Unfortunately, most existing mineral proxies suffer from ambiguities in formation or lock-in temperature as well as post-depositional alteration. A potential solution to the temperature issue is to identify a mineral whose oxygen isotope fractionation is insensitive to the surface formation temperature range. While iron oxides are promising candidates15, their fine-grained nature and intergrowth with other silicates in sediments may introduce significant analytical uncertainties in their δ18O measurements. Additionally, the age of sedimentary iron oxides can be in question, as many are secondary minerals formed via the oxidation of Fe(II) carbonates or Fe(II) silicates in later geological ages20,21. Meanwhile, quantifying post-depositional alteration on δ18Omineral remains largely an intractable problem. Recently, a promising approach has been proposed by combining δ18O and clumped isotope composition (Δ47) of carbonate minerals to identify the extent of alteration based on different water/rock ratios during diagenesis12. However, this approach requires the assumption that the carbonate minerals experienced only a single episode of post-depositional fluid interaction, which contradicts the fact that multiple fluid-rock interaction events and fluid sources often occurred during late diagenesis22,23. Sulfate, an oxygen-bearing mineral group, is nonlabile and chemically stable in its oxygen isotope composition, with no exchange occurring between sulfate and water under most surface temperature conditions24. Moreover, the original δ18O signal of sulfate can be preserved for over a billion years, as evident from the retention of non-mass-dependent 17O signatures in Proterozoic sulfate25. However, the remarkable stability of the δ18Osulfate comes at a “cost”: it is rarely in equilibrium with the δ18O of ambient water. Here, we proposed a new proxy for the δ18Oseawater, namely, the plateau δ18Osulfate value in the δ18O-δ34S trajectory of a set of 34S-variable sulfates, commonly found in sedimentary barite deposits.

During microbial sulfate reduction (MSR), sulfate can effectively exchange its oxygen isotopes with that of ambient water through reversable enzyme-catalyzed steps26,27,28,29,30,31,32 (Fig. 1). These steps include the uptake of extracellular sulfate by cell, its activation to adenosine 5’phosphosulfate (APS) via adenosine-triphosphate (ATP) enzymes, the reduction of APS to intermediate valence state sulfur species (e.g., sulfite), and the eventual reduction to hydrogen sulfide (H2S)27,32,33,34,35,36. In particular, the rapid oxygen exchange between intermediate S(IV) species, e.g., sulfite, and water is a key step in establishing the oxygen isotope equilibrium between sulfate and water, however, it alone does not account for either theoretical or observed fractionation factors (αsulfate-water). Theoretical calculation predicted an αsulfate-water value at approximately 1.023 to 1.026 at temperatures between 10 °C and 25 °C37, whereas an αsulfite-water value ranging from 1.008 to around 1.015 at room temperature within a wide pH range from 2 to 1038,39,40. The enzyme-mediated rate of the backward MSR reaction becomes increasingly significant as sulfate concentration decreases or H2S/HS- concentration increases36,41. This backward rate eventually approaches the forward sulfate reduction rate, thereby achieving oxygen isotope equilibrium between sulfate and water. Although the detailed kinetics warrants further exploration, it is anticipated that an oxygen is added to sulfite via an enzyme to become sulfate and that oxygen must have equilibrated with water. Otherwise, we would not observe a plateauing δ18Osulfate value as the corresponding δ34Ssulfate value increases. Non-equilibrium scenarios would exhibit variable δ18O/δ34S slopes on the δ18O–δ34S trajectories32. Importantly, data from laboratory experiments26,31 and modern sediment porewater sulfate29,32,42,43,44,45,46,47 are consistent with theoretical prediction of the αsulfate-water values.

These steps mainly include the activation of adenosine 5’phosphosulfate (APS) from sulfate, the reduction of APS to intermediate-valence state sulfur species (e.g., sulfite), and reduction of sulfite to hydrogen sulfide (H2S)27,32,33,34,35,36. Sulfur isotope fractionation is controlled by the reduction of APS to sulfite and sulfite to sulfide, and their reversibility36,41, while oxygen isotope fractionation of sulfate occurs during the reversible redox reactions between sulfate and APS, APS and intermediate-valence state sulfur species (e.g., sulfite) as well as sulfite-water exchange26,27,28,29,30,31,32.

Sedimentary barite deposits, both bedded and nodular types, are well-documented in geological records for their association with MSR activities48,49,50,51,52,53,54. These deposits display a wide range of δ34S values, often exceeding 50‰ within individual nodules or beds. If we measure the δ18O-δ34S paired data for a set of barite samples collected for a specific geological time, the plateau δ18Osulfate value in a δ18O-δ34S trajectory should reflect the δ18Oseawater value of that time. Here, we collected six sets of sedimentary bedded and nodular barite deposits from different geological periods of the Phanerozoic Eon. Samples from South China cover the Early Cambrian (Guizhou and Anhui Provinces), Late Ordovician (Yunnan Province), Early Silurian (Chongqing Municipality), and Late Devonian (Guizhou Province and Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region), while Late Carboniferous samples were obtained from northwest Mexico (Sonora) and Mid-Cretaceous ones from southeast France (Nyons) (Supplementary Text 1–3, Table S1). Petrographic examinations of the sedimentary barite deposits by scanning electron microscope were conducted to characterize their mineral assemblage and paragenesis (Figures S1–S6).

Results and discussion

Syngenetic sedimentary barite deposition

Sedimentary bedded barite deposits often occur in organic-rich siliceous clastic rocks, with a significant temporal clustering in the Paleozoic Era. A recent study has integrated the oceanic redox history and seawater sulfate concentrations, proposing that sulfate-limited euxinic conditions in seawater facilitate the scavenging of hydrothermally derived metal ions (Zn2+, Pb2+) and promote the accumulation of Ba2+ ions in the sulfate-free waterbody55. Subsequently, the Ba2+-rich water mass encountered a sulfate-rich one in the ocean, leading to the formation of massive bedded barite ore deposits, referred to as the Sulfate-limited Euxinic Seawater (SLES) model55. All sedimentary bedded barite deposits exhibit a wider δ34S range and higher δ34S values compared to those of the contemporaneous seawater, consistent with sulfate-limited seawater conditions. Sedimentary nodular barite deposits, however, do not exhibit clear temporal clustering and are found throughout the Phanerozoic Eon. Barite nodules formed during early diagenesis, in association with the oxidization of organic matter and microbial sulfate reduction within pore water centimeters to meters below the sediment-water interface48,56,57 and occasionally found in association with bedded barite deposits49,50,58. Evidence supporting their syngenetic origin includes the distortion of external lamination around the barite nodules48,56,57. Similarly high δ34S values are observed in nodular barite deposits48,56,57.

The petrographic results reveal that both bedded and nodular barite types exhibit primary crystal morphologies, with barite grains dispersed within a silica and/or calcium matrix (Figs. 2 and S1–S6). For instance, the Early Cambrian and Late Carboniferous barite deposits contain both bedded and nodular types. The Early Cambrian deposits are characterized by disseminated barite within quartz and calcite, while the Late Carboniferous deposits occur as columnar or globular barite in quartz (Figs. 2 and S1, S5). The Late Ordovician and Late Devonian deposits are predominantly bedded type with massive barite and minor quartz (Figs. 2 and S2, S4). The Early Silurian deposit is of nodular type, with columnar barite grains, similar to those found in the Mid-Cretaceous barite nodules (Figs. 2 and S3, S6). Petrographic examination was conducted to exclude apparent late diagenetic barite, e.g., barite veins. As we emphasized, petrographic examination cannot guarantee that we selected only the unaltered original barite. It is the δ18O-δ34S trajectory that filters out the post-depositional alternated signatures if any.

a, b Tabular and grained barites within calcium-rich matrix in Mid-Cretaceous barite nodules from the Marnes Bleues Formation of the Vocontian Basin, France. c, d Tabular and globular barite within a quartz matrix in Late Carboniferous Mazatán bedded barite deposits from Sonora, Mexico. e Massive barite with minor quartz in Late Devonian bedded barite deposits, South China. f Tabular barite within a quartz matrix in Early Silurian barite nodules, South China. g Barite within a quartz matrix in Late Ordovician bedded barite deposits, South China. h Barite within a quartz matrix in Early Cambrian bedded barite deposits, South China.

The δ18O and δ34S trajectories of barite deposits

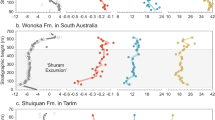

Each of the six barite deposits displays a wide range of δ18O and δ34S values. Importantly, the δ18O values approach a plateau as its corresponding δ34S values increases from ~35‰ to 80‰ for individual periods (Fig. 3). Approximately, the plateau δ18Obarite is at 18‰ during much of the early Paleozoic Era (Fig. 3), but rise to 22‰ during the early Carboniferous and mid-Cretaceous periods (Fig. 3a, 3b). In the early Silurian, barite’s plateau δ18O values approach 20‰ but declines to 18‰ in the late Devonian (Fig. 3c, 3d). In general, the plateau δ18O value of the sedimentary barite increased ~4‰ from the Cambrian to the Cretaceous periods.

a Mid-Cretaceous barite samples from southeast France. b Late Carboniferous samples from northwest Mexico. c Late Devonian samples from South China. d Early Silurian samples from South China. e Late Ordovician samples from South China. f Early Cambrian samples from South China. The maximum δ18Obarite values in the plateau region is chosen to represent the equilibrium δ18Obarite with seawater (see explanation in the main text). Data uncertainty is the external measurement uncertainty, with ±0.3‰ for both δ18Obarite and δ34Sbarite, all smaller than the size of the symbols.

The δ18O and δ34S plateauing trajectory for the six sets of barite samples largely resemble the typical pattern seen in culture experiments26,31 and field observations29,32,42,43,44,45,46,47. Under different MSR rates, the corresponding δ34Sbarite values can vary while the plateau δ18Obarite value is set by the same seawater or pore water. This is seen in the Devonian barite sample set, in which two distinct clusters of the same plateau δ18Obarite region in δ18O-δ34Sbarite space have the δ34Sbarite at approximately 36–38‰ or greater than 55‰, respectively (Fig. 3c). A similar spread of plateau δ18Obarite region is also observed at the δ34Sbarite of 51‰ and 58‰, respectively, in the Silurian data (Fig. 3d). Mixing with any sulfate source of non-equilibrium δ18Osulfate value, being it a pulse of riverine sulfate or sulfate from deep water or an adjacent basin during the barite precipitation should have pulled down the δ18Obarite values, so would any post-depositional alteration. We observed a decrease in the δ18Obarite at the highest δ34Sbarite in the Cretaceous and Cambrian data (Figs. 3a and f), which may or may not be attributed to the mixing of a small amount of seawater sulfates not in equilibrium with seawater or other unknown factors. Further statistical treatment in a plateau region would have to assume certain relationship between the δ18O and δ34S of the barite samples, which is not necessarily true in our sample set. Therefore, for now we selected the maximum δ18Obarite value in a plateau region to represent the equilibrium δ18Obarite with seawater during a particular time period, allowing the trajectory to be enhanced with new data addition in the future. Based on this criterium, the equilibrium δ18Obarite values are 18.2‰ for the Early Cambrian, 17.8‰ for the Late Ordovician, 20.4‰ for the Early Silurian, 18.4‰ for the Late Devonian, 21.5‰ for the Late Carboniferous and 21.2‰ for the Mid-Cretaceous (Fig. 3).

These δ18O-δ34S trajectories allow for independent evaluation of both oxygen isotope equilibrium and diagenetic imprints. This is what sets barite apart from other mineral proxies, such as calcite, quartz, apatite, and iron oxide, that rely on empirical and statistical assessments of optical, textural, and trace element criteria15,59,60,61.

A late Paleozoic rise of the δ18Oseawater?

While our barite δ18O-δ34S trajectory approach can offer a δ18Osulfate value that were in equilibrium with the δ18Oseawater of a particular geological time, translating the δ18Osulfate to δ18Oseawater requires an independent constraint on the barite formation temperature, as the equilibrium fractionation factor (αsulfate-water) is notably temperature-sensitive. However, the below-wave continental shelf depositional settings, constrained by thin beddings and an organic-rich siliceous clastic sequence, and their all low paleolatitude settings support a similar formation temperature for all the six time periods (Supplementary Text 4). If indeed the barite formation temperature for all the six periods are more or less similar, the ~4‰ late Paleozoic rise in the plateau δ18Obarite values indicate a similar degree of δ18O values change in seawater. This 4‰ shift may be taken seriously because similar record was also observed in a group of Devonian-Carboniferous carbonate minerals59,62 and confirmed by a reactive transport model consisting of hydrothermal alteration and continental weathering fluxes18 (Figure S7). A late Paleozoic rise of the δ18Oseawater would require a dramatic increase in the flux of high-temperature relative to surface-temperature rock-water alteration. We can speculate potential causes for the rise: 1) a deepening of ocean depth, which enhanced seawater penetration and hydrothermal fluid circulation2,10, 2) sediment “blanketing” on land and ocean crust, which decreased low-temperature alteration flux2,10, 3) a decrease in the rate of authigenic clay formation16, and 4) the oxidation of the deep ocean as mentioned for the Neoproterozoic oxygenation event15.

The δ18O difference between mineral and water is temperature sensitive for all non-iron-oxide mineral proxies and mineral samples of the same time period could come from different paleolatitudes thus their δ18O were affected by different temperatures. Thus, a secular δ18O trend could be mis-represented by samples’ uneven paleolatitude distribution. Although we argue for an attenuated variation for the formation temperature for all six sets of sedimentary barite deposits, it does not guarantee that all the six sets of barite samples formed under the same temperature. However, unlike other mineral proxies, because our barite δ18O-δ34S trajectory approach guarantees the most likely δ18Obarite value that was in equilibrium with the co-eval seawater δ18O, we now have established a robust methodology so that we can sample barite from different paleolatitudes of a particular time to quantify the paleotemperature difference. What we provide here is not the final result, but a platform for incorporating additional data, thereby enhancing both the temporal and spatial resolution of the current pattern of the plateau δ18Osulfate. This platform holds significant promise for ultimately resolving the longstanding debate surrounding one of the most important issues in Earth’s history: the δ18O and temperature history of Earth’s ocean.

Methods

Petrographic observation

Representative barite samples of each period were first sectioned, polished, and carbon-coated. Petrographic observations were then conducted using a FEI Scios Dualbeam field emission scanning electron microscope equipped with an EDAX spectrometer at the Institute of Geochemistry, Chinese Academy of Sciences (IGCAS). Backscattered electron imaging and energy-dispersive spectrometer analysis was employed for texture analysis and mineral identification.

The δ18O and δ34S measurement on barite

Barite samples were obtained using a micro-drill device and pulverized to a fine powder (< 200 mesh) using an agate mortar. The resulting powders were initially treated with 10 wt% hydrochloric acid to remove possible carbonate minerals. The residual material underwent a diethylenetriaminepentaacetic-acid dissolution and re-precipitation (DDARP) procedure to extract and purify BaSO463. The oxygen (δ18O) and sulfur isotope (δ34S) compositions of purified barite were analyzed using an EA-HT-Delta V plus and an EA-Isolink-Delta V plus, respectively, at the International Center for Isotope Effects Research, Nanjing University. The δ18O value for each barite sample was measured in duplicate, with the average value reported, while δ34S value was measured once (Source Data). Sulfur isotope measurements were calibrated against Vienna Canyon Diablo Troilite (VCDT) using two in-house barium sulfate standards: ICIER-SO-1 (15.05‰) and ICIER-SO-2 (4.05‰), both of which were calibrated against two international barite standards NBS127 (20.3‰) and IAEA-SO-5 (0.49‰). Oxygen isotope measurements were calibrated against Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water (VSMOW) using one in-house barium sulfate standard (ICIER-SO-3, 11.81‰), itself calibrated against two international barium standards NBS127 (8.6‰) and IAEA-SO-6 (−11.35‰). The standard deviation for both δ18O and δ34S measurements was better than 0.3‰ based on the performance of the in-house standards.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its supplementary information files. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Cocker, J. D., Griffin, B. J. & Muehlenbachs, K. Oxygen and carbon isotope evidence for seawater-hydrothermal alteration of the Macquarie Island ophiolite. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 61, 112–122 (1982).

Walker, J. C. & Lohmann, K. C. Why the oxygen isotopic composition of sea water changes with time. Geophys. Res. Lett. 16, 323–326 (1989).

Muehlenbachs, K. The oxygen isotopic composition of the oceans, sediments and the seafloor. Chem. Geol. 145, 263–273 (1998).

Gregory, R. T. Oxygen isotope history of seawater revised: timescales for boundary event changes in the oxygen isotope composition of seawater. Stable isotope geochemistry: A tribute to Samuel Epstein, Edited by Tayor, H. P., O’Neill, J. R. and Kaplan I. R. 3, 65–76 (The Geochemical Society, 1991).

Muehlenbachs, K., Furnes, H., Fonneland, H. C. & Hellevang, B. Ophiolites as faithful records of the oxygen isotope ratio of ancient seawater: the Solund-Stavfjord ophiolite complex as a late Ordovician example. Ophiolites in Earth History, Edited by Dilek, Y. & Robinson, P. T. 218, 401–414 (Geological Society, London, Special Publications, 2003).

Coogan, L. A., Daëron, M. & Gillis, K. M. Seafloor weathering and the oxygen isotope ratio in seawater: insight from whole-rock δ18O and carbonate δ18O and Δ47 from the Troodos ophiolite. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 508, 41–50 (2019).

Peters, S. T. et al. > 2.7 Ga metamorphic peridotites from southeast Greenland record the oxygen isotope composition of Archean seawater. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 544, 116331 (2020).

McGunnigle, J. P. et al. Triple oxygen isotope evidence for a hot Archean ocean. Geology 50, 991–995 (2022).

Lécuyer, C. & Allemand, P. Modelling of the oxygen isotope evolution of seawater: implications for the climate interpretation of the δ18O of marine sediments. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 63, 351–361 (1999).

Kasting, J. F. et al. Paleoclimates, ocean depth, and the oxygen isotopic composition of seawater. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 252, 82–93 (2006).

Veizer, J. & Prokoph, A. Temperatures and oxygen isotopic composition of Phanerozoic oceans. Earth-Sci. Rev. 146, 92–104 (2015).

Thiagarajan, N. et al. Reconstruction of Phanerozoic climate using carbonate clumped isotopes and implications for the oxygen isotopic composition of seawater. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2400434121 (2024).

Hren, M., Tice, M. & Chamberlain, C. Oxygen and hydrogen isotope evidence for a temperate climate 3.42 billion years ago. Nature 462, 205–208 (2009).

Hearing, T. W. et al. An early Cambrian greenhouse climate. Sci. Adv. 4, eaar5690 (2018).

Galili, N. et al. The geologic history of seawater oxygen isotopes from marine iron oxides. Science 365, 469–473 (2019).

Isson, T. & Rauzi, S. Oxygen isotope ensemble reveals Earth’s seawater, temperature, and carbon cycle history. Science 383, 666–670 (2024).

Turchyn, A. V. et al. Reconstructing the oxygen isotope composition of late Cambrian and Cretaceous hydrothermal vent fluid. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 123, 440–458 (2013).

Kanzaki, Y. Interpretation of oxygen isotopes in Phanerozoic ophiolites and sedimentary rocks. Geochem., Geophys. Geosyst. 21, e2020GC009000 (2020).

Kanzaki, Y. & Bindeman, I. N. A possibility of 18O-depleted oceans in the Precambrian inferred from triple oxygen isotope of shales and oceanic crust. Chem. Geol. 604, 120944 (2022).

Rasmussen, B. et al. Prolonged history of episodic fluid flow in giant hematite ore bodies: evidence from in situ U–Pb geochronology of hydrothermal xenotime. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 258, 249–259 (2007).

Rasmussen, B., Krapež, B. & Meier, D. B. Replacement origin for hematite in 2.5 Ga banded iron formation: Evidence for postdepositional oxidation of iron-bearing minerals. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 126, 438–446 (2014).

Banner, J. L. & Hanson, G. N. Calculation of simultaneous isotopic and trace element variations during water-rock interaction with applications to carbonate diagenesis. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 54, 3123–3137 (1990).

Grossman, E. L. et al. Cold low-latitude Ordovician paleotemperatures may be in hot water. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. Usa. 122, e2424291122 (2025).

Rennie, V. C. F. & Turchyn, A. V. Controls on the abiotic exchange between aqueous sulfate and water under laboratory conditions. Limnol. Oceanogr.: Methods 12, 166–173 (2014).

Crockford, P. W. et al. Claypool continued: Extending the isotopic record of sedimentary sulfate. Chem. Geol. 513, 200–225 (2019).

Fritz, P. et al. Oxygen isotope exchange between sulphate and water during bacterial reduction of sulphate. Chem. Geol. 79, 99–105 (1989).

Brunner, B., Bernasconi, S. M., Kleikemper, J. & Schroth, M. H. A model for oxygen and sulfur isotope fractionation in sulfate during bacterial sulfate reduction processes. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 69, 4773–4785 (2005).

Brunner, B. et al. The reversibility of dissimilatory sulphate reduction and the cell-internal multi-step reduction of sulphite to sulphide: insights from the oxygen isotope composition of sulphate. Isotopes Environ. Health Stud. 48, 33–54 (2012).

Wortmann, U. G. et al. Oxygen isotope biogeochemistry of pore water sulfate in the deep biosphere: dominance of isotope exchange reactions with ambient water during microbial sulfate reduction (ODP Site 1130). Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 71, 4221–4232 (2007).

Mangalo, M., Meckenstock, R. U., Stichler, W. & Einsiedl, F. Stable isotope fractionation during bacterial sulfate reduction is controlled by reoxidation of intermediates. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 71, 4161–4171 (2007).

Farquhar, J. et al. Sulfur and oxygen isotope study of sulfate reduction in experiments with natural populations from Faellestrand, Denmark. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 72, 2805–2821 (2008).

Antler, G. et al. Coupled sulfur and oxygen isotope insight into bacterial sulfate reduction in the natural environment. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 118, 98–117 (2013).

Brunner, B. & Bernasconi, S. M. A revised isotope fractionation model for dissimilatory sulfate reduction in sulfate reducing bacteria. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 69, 4759–4771 (2005).

Antler, G. et al. Combined 34S, 33S and 18O isotope fractionations record different intracellular steps of microbial sulfate reduction. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 203, 364–380 (2017).

Sim, M. S. et al. Role of APS reductase in biogeochemical sulfur isotope fractionation. Nat. Commun. 10, 44 (2019).

Sim, M. S. et al. What controls the sulfur isotope fractionation during dissimilatory sulfate reduction?. ACS Environ. Au 3, 76–86 (2023).

Zeebe, R. E. A new value for the stable oxygen isotope fractionation between dissolved sulfate ion and water. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 74, 818–828 (2010).

Müller, I. A., Brunner, B., Breuer, C., Coleman, M. & Bach, W. The oxygen isotope equilibrium fractionation between sulfite species and water. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 120, 562–581 (2013).

Wankel, S. D., Bradley, A. S., Eldridge, D. L. & Johnston, D. T. Determination and application of the equilibrium oxygen isotope effect between water and sulfite. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 125, 694–711 (2014).

Hemingway, J., Goldberg, M. L., Sutherland, K. & Johnston, D. Theoretical estimates of sulfoxyanion triple-oxygen equilibrium isotope effects and their implications. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 336, 353–371 (2022).

Wing, B. A. & Halevy, I. Intracellular metabolite levels shape sulfur isotope fractionation during microbial sulfate respiration. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. Usa. 111, 18116–18125 (2014).

Böttcher, M. E., Bernasconi, S. M. & Hans-Jürgen Brumsack. Carbon, sulfur, and oxygen isotope geochemistry of interstitial waters from the western mediterranean. Proceedings of the Ocean Drilling Program, Scientific Results, Edited by Zahn, R., Comas, M. C. & Klaus, A.. 161, 413–421 (1999).

Aharon, P. & Fu, B. Microbial sulfate reduction rates and sulfur and oxygen isotope fractionations at oil and gas seeps in deepwater Gulf of Mexico. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 64, 233–246 (2000).

Turchyn, A. V., Sivan, O. & Schrag, D. P. Oxygen isotopic composition of sulfate in deep sea pore fluid: evidence for rapid sulfur cycling. Geobiology 4, 191–201 (2006).

Turchyn, A. V., Antler, G., Byrne, D., Miller, M. & Hodell, D. A. Microbial sulfur metabolism evidenced from pore fluid isotope geochemistry at Site U1385. Glob. Planet. Change 141, 82–90 (2016).

Wehrmann, L. M. et al. The imprint of methane seepage on the geochemical record and early diagenetic processes in cold-water coral mounds on Pen Duick Escarpment, Gulf of Cadiz. Mar. Geol. 282, 118–137 (2011).

Feng, D. & Roberts, H. H. Geochemical characteristics of the barite deposits at cold seeps from the northern Gulf of Mexico continental slope. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 309, 89–99 (2011).

Bréhéret, J. G. & Brumsack, H. Barite concretions as evidence of pauses in sedimentation in the Marnes Bleues Formation of the Vocontian Basin (SE France). Sediment. Geol. 130, 205–228 (2000).

Clark, S. H., Poole, F. G. & Wang, Z. Comparison of some sediment-hosted, stratiform barite deposits in China, the United States, and India. Ore Geol. Rev. 24, 85–101 (2004).

Johnson, C. A., Emsbo, P., Poole, F. G. & Rye, R. O. Sulfur-and oxygen-isotopes in sediment-hosted stratiform barite deposits. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 73, 133–147 (2009).

Canet, C. et al. Paleozoic bedded barite deposits from Sonora (NW Mexico): Evidence for a hydrocarbon seep environment of formation. Ore Geol. Rev. 56, 292–300 (2014).

Zhou, X. et al. Diagenetic barite deposits in the Yurtus Formation in Tarim Basin, NW China: Implications for barium and sulfur cycling in the earliest Cambrian. Precam. Res. 263, 79–87 (2015).

Xu, L. et al. Strontium, sulfur, carbon, and oxygen isotope geochemistry of the Early Cambrian strata-bound barite and witherite deposits of the Qinling-Daba Region, Northern Margin of the Yangtze Craton, China. Econ. Geol. 111, 695–718 (2016).

Fernandes, N. A. et al. The origin of Late Devonian (Frasnian) stratiform and stratabound mudstone-hosted barite in the Selwyn Basin, Northwest Territories, Canada. Mar. Petrol. Geol. 85, 1–15 (2017).

Han, T., Peng, Y. & Bao, H. Sulfate-limited euxinic seawater facilitated Paleozoic massively bedded barite deposition. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 582, 117419 (2022).

Goldberg, T., Mazumdar, A., Strauss, H. & Shields, G. Insights from stable S and O isotopes into biogeochemical processes and genesis of Lower Cambrian barite–pyrite concretions of South China. Org. Geochem. 37, 1278–1288 (2006).

Zan, B. et al. Diagenetic barite-calcite-pyrite nodules in the Silurian Longmaxi Formation of the Yangtze Block, South China: A plausible record of sulfate-methane transition zone movements in ancient marine sediments. Chem. Geol. 595, 120789 (2022).

Jewell, P. W. & Stallard, R. F. Geochemistry and paleoceanographic setting of central Nevada bedded barites. J. Geol. 99, 151–170 (1991).

Carpenter, S. J. et al. δ18O values, 87Sr/86Sr and Sr/Mg ratios of Late Devonian abiotic marine calcite: implications for the composition of ancient seawater. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 55, 1991–2010 (1991).

Sharp, Z. D., Atudorei, V. & Furrer, H. The effect of diagenesis on oxygen isotope ratios of biogenic phosphates. Am. J. Sci. 300, 222–237 (2000).

Marin-Carbonne, J., Robert, F. & Chaussidon, M. The silicon and oxygen isotope compositions of Precambrian cherts: A record of oceanic paleo-temperatures?. Precambrian Res 247, 223–234 (2014).

Lohmann, K. C. & Walker, J. C. The δ18O record of Phanerozoic abiotic marine calcite cements. Geophys. Res. Lett. 16, 319–322 (1989).

Bao, H. Purifying barite for oxygen isotope measurement by dissolution and reprecipitation in a chelating solution. Anal. Chem. 78, 304–309 (2006).

Acknowledgements

This work is funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (U23A2027 to T.H. and W2441015 to H.B.), the Geological Exploration Fund of Guizhou Province (2024-2 to T.H.), the CAS “Light of West China” Program and the Institute of Geochemistry, Chinese Academy of Sciences (DHSZZ2023-6 to T.H.), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (0206/14380232 to H.B. and 0206/14380204, 2025-Z01 to Y.P.), and the New Cornerstone Science Foundation through the XPLORER PRIZE (to Y.P.). We thank Dr. Fengtai Tong, Dr. Zhenfei Wang, Dr. Jing Gu for assistance in isotope analysis, Dr. Bing Mo and Ms. Yuanyun Wen for assistance in petrographic imaging using a field emission scanning electron microscope, Dr. Jiafei Xiao (IGCAS) for the barite sampling in South China, Prof. Carles Canet, Dr. Jorge Alberto Miros-Gómez (Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México), and Prof. Jean-G. Bréhéret (Université François Rabelais) for the Carboniferous and Cretaceous barite samplings in Mexico and France, respectively.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T. H., H. B. and Y. P. designed the study. T. H., H. B., Y. P., Z. L. and Y. S. collected samples. T. H., Y. P., Z. L. and Y. S. carried out petrographic and sulfur and oxygen isotopic analysis. T. H. and H. B. wrote the manuscript. All authors analyzed and discussed the data, and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Han, T., Bao, H., Peng, Y. et al. The barite record of the past seawater oxygen isotope composition. Nat Commun 16, 5018 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60309-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60309-z