Abstract

Quantifying protein turnover is fundamental to understanding cellular processes and advancing drug discovery. Multiplex-DIA mass spectrometry (MS), combined with dynamic SILAC labeling (pulse-SILAC, or pSILAC) reliably measures protein turnover and degradation kinetics. Previous multiplex-DIA-MS workflows have employed various strategies including leveraging the highest isotopic labeling channels to enhance the detection of isotopic signal pairs. Here we present a robust workflow that integrates a machine learning algorithm and channel-specific statistical filtering, enabling dynamic adaptation to channel ratio changes across multiplexed experiments and enhancing both coverage and accuracy of protein turnover profiling. We also introduce KdeggeR, a data analysis tool optimized for pSILAC-DIA experiments, which determines and visualizes peptide and protein degradation profiles. Our workflow is broadly applicable, as demonstrated on 2-channel and 3-channel DIA datasets and across two MS platforms. Applying this framework to an aneuploid cancer cell model before and after cisplatin resistance, we uncover strong proteome buffering of key protein complex subunits encoded by the aneuploid genome mediated by protein degradation. We identify resistance-associated turnover signatures, including mitochondrial metabolic adaptation via accelerated degradation of respiratory complexes I and IV. Our approach provides a powerful platform for high-throughput, quantitative analysis of proteome dynamics and stability in health and disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Protein turnover, the balance between synthesis and degradation, is a fundamental process that regulates cellular homeostasis, adaptation, and response to environmental stimuli. It plays a crucial role in a variety of biological processes, including cell growth, differentiation, and apoptosis, and is a critical factor in understanding disease progression and therapeutic responses. In cancer biology, for example, altered protein turnover rates are often linked to genomic instability, such as aneuploidy and resistance to chemotherapeutic agents like cisplatin1,2. Measuring protein turnover in these contexts is essential for identifying potential therapeutic targets, biomarkers, and mechanisms of proteostasis in aneuploid cells.

Mass spectrometry (MS)-based approaches have become a key tool for studying protein turnover, with data-independent acquisition (DIA) MS being one of the most robust and reproducible techniques3,4. The multiplex-DIA-MS approach essentially increases the analytical throughput of DIA-MS5,6,7 and, when combined with dynamic stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture (pulse-SILAC, or pSILAC)8,9,10,11, it allows for multi-time-point measurements and precise quantification of protein-specific turnover rates across diverse biological conditions5,12,13,14,15,16,17. The reproducibility of DIA-MS makes it particularly well-suited for complex experimental designs such as time-course experiments in dynamic SILAC design.

Recently, techniques such as BoxCarmax17,18, which enables small isolation windows in combination with multiple sample injections, and instruments like Astral and timsTOF, which support DIA-MS of narrow isolation windows directly19,20,21, are able to significantly improve the peptide detection and quantification of heavy to light (H/L) ratios by separating the H and L versions of SILAC peptides into different MS2 scans. Accordingly, a larger fraction of peptide fragment ions, such as b ions, become eligible for DIA-MS quantification. These advancements will greatly increase the precision and throughput of protein turnover analysis.

In pSILAC experiments, the intensity ratio of the labeled and unlabeled channels reflects the protein turnover rate. This may result in the near absence of one of the channels for a particular protein (or peptide) in the early and very late time points, presenting a challenge in measuring H/L ratios. Previous signal extraction strategies have focused on specific channels: we previously presented an “Inverted Spike-In Workflow” (ISW)5, which utilizes only the light channel for scoring and signal detection in pSILAC-DIA data, increasing the number of H/L pairs quantified by approximately 30% in early pSILAC labeling time points. However, ISW is not ideal for the late pSILAC labeling time points and other multiplex-DIA-MS experiments in which the labeled peptide signals can often be higher than the light ones depending on the specific experimental condition and individual proteins. On the other hand, multiplex-DIA-MS analysis strategies such as plexDIA7 or mDIA6, implemented within DIA-NN22 or RefQuant6, target the best isotopic channel or the reference channel to improve peptide detection. While effective, these approaches still leave room for optimization, such as leveraging all available isotopic channels and peptide transitions for more comprehensive analysis.

Here, we introduce an approach that incorporates machine learning and channel-specific statistical filtering into the peptide detection process for multiplex-DIA datasets, referred to as “Labeled” workflow (LBL). Our method dynamically adapts to systematic changes in isotopic channel ratios, ensuring effective utilization of all channels without requiring pre-selection of the highest-signal channel. We extensively assessed our strategy and found that, together with a subsequent data processing tool, it significantly enhanced the accuracy and robustness of protein turnover measurements in complex pSILAC. To apply our workflow, we focused on a cancer cell model of aneuploidy. Aneuploidy, characterized by an abnormal number of chromosomes, alters the protein homeostasis landscape, leading to unique turnover profiles that may contribute to the development of drug resistance. Our pSILAC-DIA measurement and workflow, applied to aneuploid ovarian cells with divergent cisplatin resistance, successfully uncovered key turnover signatures and regulatory mechanisms that may drive resistance.

Results

Overview of a robust workflow for multiplex-DIA MS data analysis: Enabling large-scale protein turnover quantification and comparative studies

Multiplex-DIA-MS, combined with pSILAC, enables precise quantification of protein turnover across multiple conditions by measuring protein dynamics at different time points (Fig. 1, Upper left). However, the effective detection and quantification of MS signals in these datasets in which the heavy (or labeled) signals are generally low abundant in the early labeling time points remains challenging. To address this, we previously introduced the “Inverted Spike-In Workflow” (ISW)5. ISW relied on an extensive hybrid peptide spectral library generated from the measurements of label-free and multiplexed samples by both DDA-MS and DIA-MS. This spectral library was then used to perform the targeted extraction in the multiplex-DIA-MS files (Fig. 1, Lower left). In ISW, the peak picking and scoring are based exclusively on the light precursors, which was demonstrated to be advantageous in samples with a low relative abundance of heavy signals such as extreme H/L dilutions18 or early labeling time points of a pSILAC experiment5.

Upper left: Protein turnover analysis on a large scale using dynamic stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture (pSILAC), combined with highly robust and reproducible multiplex data-independent acquisition (DIA) mass spectrometry (MS), enables the quantification of thousands of protein turnover rates and facilitates quantitative comparisons between multiple conditions. Datasets from two MS platforms (Orbitrap Fusion Lumos and timsTOF Ultra) were processed. Lower left: In the previously reported “Inverted Spike-In Workflow” (ISW), peak picking and scoring relied solely on the light channel. In the “Labeled” (LBL) workflow, XIC peak picking, elution group scoring, and “Group Qvalue” calculation are performed across all channels (n = 2, 3, …, N) in a combined fashion, facilitated by improved machine learning. Upper middle: In addition to the “Group Qvalue”, our Spectronaut v19 (SN19) solution now offers channel-specific q-value filtering options for more stringent quantification data filtering. In the “Min Qvalue” option, at least one channel needs to be independently identified (q-value < 0.01), while in the “Max Qvalue” option, all channels must be independently identified (q < 0.01) to accept the entire elution group. Lower middle: As part of the workflow, we provide an R package named KdeggeR for the analysis of pulse SILAC DIA-MS data from various raw data processing software, including data formatting, data filtering and quality control (QC), the calculation of precursor-, peptide-, and protein-level turnover rates (kloss), subsequent protein degradation rate (kdeg) transformation, comparative data analysis, and data visualization. Upper right: We evaluated the multichannel analysis implemented in SN19 (and onwards) using 2-channel and 3-channel standard datasets acquired previously and publicly available (Salovska et al., 2021; Bortecen et al., 2024). Lower right: We demonstrated the feasibility of the entire workflow by applying it to the study of protein turnover regulation in a cisplatin resistance model of the highly aneuploid ovarian cancer cell line A2780 and integrated the data with other omic layers. This application highlighted the importance of studying protein turnover to derive biological insights into complex phenomena such as cancer drug-resistance phenotype. Several components were Created in BioRender. Liu, Y. (2025) https://BioRender.com/7y30v3c.

However, recent rapid advancements in library-free DIA-MS data analysis in software such as the directDIA+ algorithm in Spectronaut23 and other software tools like DIA-NN22, or FragPipe24, driven by machine learning and deep learning techniques, have essentially eliminated the need for generating extensive project-specific spectral libraries for routine peptide identification tasks in proteomics, significantly streamlining DIA-MS data analysis. Herein, we reason that performing the XIC peak picking and elution group scoring using the information across all channels (n = 2, 3, …, N) may enable a dynamic scoring of increasingly complex labeling experiments accommodating a wider range of labeled/unlabeled ratios over the entire multiplex-DIA experiment and support additional labeling channels.

Leveraging the directDIA+ algorithm and improved machine learning, we optimized and evaluated a library-free “Labeled” workflow (LBL), which is available in Spectronaut v19 (Fig. 1, Lower left). Notably, during the targeted peak extraction, this workflow performs the XIC peak picking across all channels in a combined fashion. Moreover, in the elution group scoring, all channels along with their specific and cross-channel scores are considered collectively in the machine learning process, leading to the estimation of a “Group Q-value”. Together, these enable dynamic adaptation to systematic changes in channel ratios per sample, resulting in optimal scoring weights for labeled and unlabeled peptide transitions. These scoring weights showed strong consistency with the SILAC ratios in real pSILAC experiments (Fig. 1, Upper Middle). Additionally, the labeled or unlabeled channels can be scored independently using channel-specific metrics, supporting the determination of channel-specific q-values, a feature newly introduced in Spectronaut v19. This further enables channel-specific FDR filtering of the quantification results. In the “Min Q-value” option, at least one channel needs to be independently identified (q-value < 0.01), while in the “Max Q-value” option, all channels must be independently identified to accept the entire elution group for a given peptide (Fig. 1, Upper Middle). To evaluate sensitivity, quantification precision, and accuracy, we applied these integrative data processing steps to a 2-channel standard dilution dataset18 and a 3-channel dataset25 (Fig. 1, Upper Right, see Methods).

To facilitate downstream analysis of the pSILAC data, we also present an open-source R package, KdeggeR, which streamlines the processing and visualization of pSILAC DIA-MS data. KdeggeR performs data formatting, quality control, calculation of peptide and protein turnover rates (kloss), degradation rates (kdeg), comparative analysis, and data visualization (Fig. 1, Lower Middle, see Methods). The package supports data from various raw data processing software, making it a versatile tool for a range of proteomics workflows.

Finally, we applied the complete workflow to investigate protein turnover regulation in a cisplatin-resistant ovarian cancer model, using A2780 and A2780Cis cell lines. By integrating the multiplex-DIA data with other omics, we gained insights into the mechanisms underlying drug resistance and proteome buffering in this highly aneuploid cancer model (Fig. 1, Lower Right).

Improved identification of multiplex-DIA-MS datasets through machine learning-guided dynamic selection of isotopic labeling features

To assess the effectiveness of the LBL and compare it to the ISW, we analyzed the A2780 standard 2-channel SILAC dilution series (H:L: 1:16, 1:8,…, to 8:1, 16:1) as the first benchmarking dataset18 using both LBL and ISW workflows in Spectronaut 19. We found that, in a library-free analysis of the 1:1 sample, LBL identified 142,363 precursors and 7785 protein groups (Fig. 2A, Supplementary Fig. 1A), representing increases of 3.8% and 12%, respectively, compared to the current ISW result. Strikingly, this represents 147.6% and 35.3% more precursors and protein groups than we reported previously in the same samples analyzed using ISW with an extensive, project-specific hybrid library (which contained 188,886 peptide precursors corresponding to 7,457 proteins) with Spectronaut v1418. These results demonstrate improved performance, particularly due to the deep learning features included in the recent DIA data analysis software tools22,23,24. Furthermore, in the A2780 dilution series, LBL outperformed ISW (both in Spectronaut 19) by identifying more precursors and proteins across various mixing conditions (Fig. 2B, Supplementary Fig. 1B). In the light-dominant samples, LBL identified slightly more features (approximately 10% more precursors and 5% more protein groups), indicating that the concurrent consideration of heavy transitions during the machine learning step still improved the peptide pair detection even in these samples. Importantly, LBL dramatically outperformed ISW in the heavy-dominant samples (2–7.5 times more precursors and 1.3–2.7 times more protein groups). In line with this, the LBL workflow successfully assigned scoring weights to both channels in a dynamic manner, which is consistent with the actual SILAC ratios in each sample (Fig. 2C). The LBL workflow also achieved a global FDR below 1% in a 3rd channel decoy experiment (Supplementary Fig. 1F).

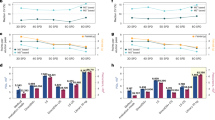

A Improved identification using the “Labeled” workflow (LBL) implemented in SN19 in the A2780 sample with H/L = 1; the numbers of identifications at the precursor (left) and protein (right) levels are shown. B The “Labeled” workflow (LBL) outperformed the “Inverted Spike-In Workflow” (ISW) in the A2780 dilution series analysis; the numbers of identified IDs at the precursor and protein (in brackets) levels are shown. C Scoring weight histogram from the 2-channel A2780 dilution series experiment. Number of precursors (D) and proteins (E) identified in the 3-channel HeLa standard sample experiment; the numbers of IDs identified in experimental replicates are shown. F Scoring weight histogram from the 3-channel HeLa standard sample experiment. The bars represent the average weights per condition/mix. G Protein-level identifications in the pulse SILAC experiment in the A2780 cell line. H Precursor- and protein-level comparison of identifications between samples measured using the timsTOF Ultra and Orbitrap Fusion Lumos platforms. I Protein-level identification in a pSILAC experiment. A, B, D, E Both analyses using the LBL and ISW were performed in the same version of Spectronaut 19. In all figures, the LBL was run with the default GroupQ quantification filtering option (q < 0.01). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

As the second benchmarking dataset, we leveraged a public dataset of HeLa cells with three SILAC labeling states (Light, Medium, and Heavy)25. This dataset consisted of two different compositions, i.e., mix1 (H:M:L = 15:15:70) and mix2 (H:M:L = 40:40:20). In both mixes, we found that LBL identified more precursors and proteins, leading to a greater number of pairwise ratios between the three channels (Fig. 2D, E, Supplementary Fig. 1C). Similar to the 2-channel result, LBL yielded a slight improvement in the light-dominant mix1, with 5.3% and 12.7% more precursors and proteins identified, respectively. In mix2, in which the light peptides accounted for only 20%, LBL showed a dramatic improvement, identifying 115.9% and 28.9% more precursors and proteins, respectively. The number of missing values across the replicates was very low in the results based on the LBL workflow, especially at the protein level (2.73% on average, Fig. 2E). The scoring weight histogram of this 3-channel dataset provided additional compelling evidence supporting LBL (Fig. 2F).

Next, to evaluate LBL performance in real pSILAC experiments, we acquired and analyzed a third dataset from the A2780 cell line measured on an Orbitrap Fusion Lumos MS (see Methods). Herein, LBL consistently identified an average of 6900 proteins across four time points and three experimental replicates (Fig. 2G). To validate the general applicability of LBL, we analyzed another pSILAC experiment conducted in two fibroblast cell lines, with datasets obtained from two independent LC-MS platforms, Orbitrap Fusion Lumos and timsTOF Ultra (Fig. 2H, see Methods). Impressively, with a 2.5-fold shorter gradient and less than 10% of the sample amount (130 ng vs 1.5 µg), using the timsTOF Ultra platform we identified, in total, 227,242 precursors and 9270 protein groups (that is, 30.1% and 31.2% more than using Lumos, respectively, Fig. 2H), and achieved a consistent turnover quantification of 9130 proteins on average (Fig. 2I). The protein degradation rates also showed a decent cross-platform consistency (Supplementary Fig. 2A). Moving beyond pSILAC-DIA applications, we tested a 2- and 3-channel dimethyl-labeling multiplex-DIA (mDIA) sample set from a current study analyzed by both Orbitrap Exploris 480 and timsTOF HT platforms6. In this sample set, LBL (at a channel identification FDR below 1%, Supplementary Fig. 2B) identified and quantified a comparable number of peptide precursors (about ±10%, Supplementary Fig. 2C, D) and a slightly lower number of protein IDs (10% lower in timsTOF data and ~20% less in Orbitrap data, Supplementary Fig. 2E–G) compared to the original report using DIA-NN and spectral libraries predicted by AlphaPeptDeep6,26. Altogether, these analyses demonstrated the versatility and reliability of LBL across instruments from different vendors and various multiplex-DIA-MS experiments.

Channel-specific q-value filtering for quantifying ratios of isotopically labeled peptides

Because LBL performs the elution group scoring across all channels and individually for each channel, the multiplex-DIA quantitative results can be exported with flexible data filtering. This is supported by the following new options in Spectronaut: “Group Q-value” (shown above; GroupQ), “Min Q-value” (MinQ), or “Max Q-value” (MaxQ). In MinQ, only one of the channels needs to independently pass the q-value threshold (q < 0.01) for quantifying ratios of isotopically labeled peptides. In MaxQ, however, all channels present in the sample need to pass the q-value < 0.01 threshold, providing the most conservative filtering option. We evaluated these filtering options using the above 2- and 3-channel SILAC datasets and the A2780 pSILAC-DIA dataset (Fig. 3).

A Comparison of protein-level ratio distribution in the A2780 standard dilution samples after different q-value quantification filtering for multichannel samples (enabled in SN19); the dashed lines and numbers represent the medians of the data distributions, shown using density plots; the points represent individual values. B The histograms indicate the number of protein-level H/L ratios quantified in the samples shown in (A). C Comparison of protein-level ratio distributions in the HeLa 3-channel standard sample after different q-value quantification filtering. Ratios were calculated between channels as indicated and represent average from 3 replicates. The dashed lines indicate expected ratios based on sample composition; the numbers represent observed median values. D Binned protein-level ratio CV based on 3 replicates in the HeLa sample after different q-value quantification filtering. E Comparison of protein-level H/L ratios in the pulse SILAC A2780 samples after different q-value quantification filtering. The protein-level ratios were calculated based on 3 replicates. The numbers represent observed median values. F Binned protein-level ratio CV based on 3 replicates in the A2780 pulse SILAC sample after different q-value quantification filtering. In (A–F) groupQ, minQ, and maxQ refer to “Group Q-value”, “Min Q-value”, and “Max Q-value” filtering, which are the quantification settings in the data analysis in SN19. In (C, E) the boxes indicate Q1–Q3 with the median; whiskers span 1.5 × IQR. Outliers beyond this range are shown as individual points. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

In the 2-channel dilution series, the GroupQ and MinQ options provided a similar quantification result with comparable numbers of quantified protein-level ratios and accuracy. We found that MaxQ led to more conservative filtering results with considerable data loss in the extreme ends of the dilution series, which seemed to be overall intensity dependent (Fig. 3A, B). At the same time, MaxQ provided more stringent filtering that improved quantification precision, as shown by the significantly reduced standard deviations in the H/L ratio distributions, with similar overall median values. At the precursor level, there was a substantial overlap between the quantified precursors between the GroupQ and MinQ filtered results (Supplementary Fig. 1D), with GroupQ consistently identifying slightly more precursors (~3.3% more on average), emphasizing the benefit of considering all channels simultaneously.

The analysis of the 3-channel experiment yielded similar results. While the median protein-level ratio values remained quite consistent across all three filtering options, the MaxQ filtering increased quantitative precision (Fig. 3C) but also resulted in a significant reduction in the number of quantified proteins (on average 29.9% in mix1 and 9% in mix2, Fig. 3D). This reduction also affected proteins with a CV across replicates <20% (14.1% in mix1 and 5.4% in mix2). This result indicated that MaxQ was compromised by a partial loss of high-quality signals.

Next, to benchmark these results against another alternative multiplex-DIA-MS workflow, we applied plexDIA7 workflow in DIA-NN 1.9 with the recommended matrix channel filtering (q < 0.01)25 (Supplementary Fig. 3). Notably, the 2-channel results from the plexDIA workflow most closely matched those of the MaxQ filtering option, with a higher number of quantified protein-level ratios in the MaxQ result (up to 30% in the 1/16 and 16/1 H/L samples). A slightly better precision was observed in the plexDIA results using DIA-NN (Supplementary Fig. 3A). In the 3-channel sample, we observed a similar trend but a slightly better precision of MaxQ (Supplementary Fig. 3C). When we restricted our analysis to the same precursors and proteins, the ratio distributions appeared nearly identical between Spectronaut and DIA-NN workflows (Supplementary Figs. 3B, S3D).

In the pSILAC A2780 dataset, MaxQ filtering significantly reduced the number of quantified protein ratios in the first time point (Figs. 3E, F), and the ratios showed an overall lower median. However, in the overlapping IDs, the distributions were largely identical (Supplementary Fig. 1E). Again, MaxQ reduced noisy data points used for quantification, while also discarding a substantial subset of proteins with a good across replicate CV < 20% (an average of 32.7% and 13.8% at the 1st and 2nd time point, respectively, Fig. 3F).

Together, in all datasets evaluated, both GroupQ and MinQ options retained higher sensitivity, while the MaxQ improved quantification precision at the cost of a considerable reduction in quantified proteins. Of note, identification results per individual channel can be further exported (see Methods and Supplementary Notes 1 and 3) for inspecting the pre-analytical and experimental factors (e.g., channel mislabeling) if needed.

KdeggeR: a comprehensive R package for proteomic turnover analysis

To streamline the analysis of pSILAC-DIA datasets, we present KdeggeR, an integrative R package. KdeggeR offers functions for importing data from multiple common raw data processing tools, ensuring compatibility across MS platforms. It also performs data cleaning and quality control steps to prepare the data for analysis (Fig. 4A). Next, KdeggeR allows for the estimation of kloss at the precursor level using three different published methods5,11,13,27,28,29, which can be then aggregated to the peptide or protein level. By default, the aggregation step is performed using a weighted average of precursor-level kloss values, with weights determined by the precursor-level fit quality and the number of data points, but this step can be customized. KdeggeR also calculates protein degradation rates (kdeg) and half-lives (t1/2) using either user-provided or theoretically estimated cell division rates (kcd). Finally, the package also includes visualization tools to assess precursor- and protein-level fitting and quantification results and to conduct comparative turnover analyses between different conditions (see Methods for more details).

A The KdeggeR package streamlines pSILAC data analysis by providing functions for importing data from several common raw data processing software tools, data cleaning, and quality control. Next, precursor-level kloss can be estimated using three different methods, and protein-level kloss can be calculated by performing a weighted average of the corresponding precursor-level kloss values, considering precursor-level fit quality and/or the number of data points. Protein degradation rates (kdeg) and half-life (t1/2) are calculated using cell division rate (kcd) values provided by the user or by using a theoretical kcd value estimated from the kloss value distribution. Visualization functions enable inspection of the precursor- and protein-level fitting results and comparative analysis between multiple conditions. B Demonstration of precursor-level quality filtering in the dynamic SILAC experiment performed in the A2780 cell line. Data were analyzed using the LBL workflow and exported using the “Group Q-value” (groupQ), “Min Q-value” (minQ), and “Max Q-value” (maxQ) channel quantification filtering. C–E Example analysis of MBNL1, a protein with a significantly slower turnover rate in the A2780Cis (resistant) cell line compared to the parental A2780 cell line. C Protein-level kloss fit to all precursor-level data. D Distribution of precursor-level kloss values (N = 3) corresponding to the MBNL1 protein. The boxes indicate Q1–Q3 with the median; whiskers span 1.5 × IQR. Outliers beyond this range are shown as individual points. E A representative example of precursor-level kloss calculation by performing nonlinear least squares (nls) fitting using the relative isotope abundance of the light peptide (RIA). The plots were visualized using the KdeggeR package. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

We utilized KdeggeR to process the protein turnover datasets from the A2780 (used above) and A2780Cis ovarian cancer cell lines30. The cisplatin-resistant cell line A2780Cis was developed by exposing the parental cisplatin-sensitive cell line A2780 to increasing concentrations of cisplatin31. A triplicate pSILAC experiment was performed with four time points (1, 4, 8, and 12 h) and measured on an Orbitrap Lumos MS (Fig. 1, Lower Right). The raw data were processed using the LBL workflow and filtered using the GroupQ, MinQ, and MaxQ functions, respectively. Figure 4B illustrates the precursor-level quality filtering in KdeggeR, where we applied a series of filtering criteria based on data completeness and assumptions specific to a pSILAC experiment (see Methods). In addition, we included an option considering outlier values in the early time point (i.e., the first data point) by performing a linear regression on the log-transformed H/L ratios (ln (H/L + 1)) and conducting a statistical test to determine if the first time point significantly deviates from the residual distribution (“Outlier filtering”). This is because the first short labeling time point may be critical for precisely determining the turnover rates of short-lived proteins12,15 or modified peptides15. However, due to the lower intensity of heavy-labeled peptides at this initial stage in many pSILAC experiments, the H/L ratios can exhibit substantially higher noise levels compared to later time points, which may impact the accuracy of the turnover rate quantification. As shown in Fig. 4B, applying this data filtering approach effectively reduced the standard deviations of H/L ratio distributions, particularly in the first and second time points, while retaining significantly more values with the GroupQ filter compared to the more conservative MaxQ filter. Thus, the GroupQ-filtered dataset was selected for our downstream analysis of the A2780 experiment. We found that, following linear regression analysis of the log-transformed precursor-level ratios by KdeggeR, most curves had R2 values greater than 0.9 (Supplementary Fig. 4A). We next used the RIA method and a weighted average, both available in KdeggeR, to estimate the precursor and protein-level rates of loss (kloss) values (see Methods). This enabled the estimation of an average of 6866 protein kloss values across the two cell lines and replicates (Supplementary Fig. 4B), which were subsequently transformed into kdeg for the downstream analysis. For example, KdeggeR facilitated the identification of MBNL1, a protein exhibiting significantly slower turnover in the A2780Cis compared to A2780 (Fig. 4C–E), as visualized by the plotting functions available in KdeggeR. Our package further supports a series of plots visualizing the intermediate and final quantification results determining protein turnover (Fig. 4C–E, Supplementary Fig. 4C).

Together, KdeggeR allows for accurate and flexible calculation of protein turnover rates, making it accessible for users without a strong bioinformatic background.

Multi-omics analysis reveals the dual role of protein degradation in proteomic buffering against chromosomal aneuploidy and promoting cisplatin resistance

Cancer development is often linked to genomic instability and the adaptive evolution of malignant clones. This results in potential genomic alterations conferring selective advantages, such as adaptation to chemotherapy. However, it also imposes a substantial burden on cells to maintain proteostasis. Previous studies, including our own, have shown that cells can harness protein degradation systems to buffer the proteomic imbalances resulting from aneuploidy and genomic instability5,14,32,33,34. The A2780 and A2780Cis ovarian cancer cell lines represent a well-established aneuploidy model for studying cisplatin resistance, with well-documented and distinct karyotypic abnormalities in both parental and cisplatin-resistant cells30. These aneuploid abnormalities have been characterized through genomic35,36 and proteomic37 analyses. However, an exploration of protein turnover and its role in responding to chromosomal aneuploidy and driving drug resistance remains underexplored.

To investigate how protein turnover regulates drug resistance associated with genomic imbalance, we conducted an integrative multi-omics analysis of aneuploid A2780 and A2780Cis cells. By combining proteomic data—covering both protein abundance and degradation rates (kdeg)—with transcriptomic data from a previous study35, we firstly confirmed a positive correlation between mRNA and protein log2 fold changes (R = 0.661, Supplementary Fig. 5A), which is as strong as previously reported mRNA-protein correlations among cancer cells38,39. This result indicated a good match between omics datasets. Furthermore, the correlation between mRNA and kdeg was weakly positive (R = 0.145, Supplementary Fig. 5B), consistent with our previous work in HeLa cells5,13. This reinforces the notion that mRNA-kdeg correlation serves as a valuable indicator of finely tuned post-translational buffering by protein turnover. Next, we used the copy number alteration (CNA) information from the same cell lines36 and mapped the protein-coding genes to the integrated dataset (Fig. 5A). As expected, the mRNA levels largely followed the CNA changes, and a similar trend was observed in protein abundance data, although the dosage change appeared attenuated at the proteome level (Fig. 5A).

A Copy number alterations (CNA) in the A2780 paired cell line model were mapped to transcriptomic data, protein abundance data, and protein degradation rate (kdeg) values measured by DIA-MS. The CNA and transcriptomic data were generated by previous studies analyzing the same cell lines (Prasad et al. 2008; Behrman et al. 2021). Relative differences between A2780Cis (resistant) and A2780 (parental) are shown on the y-axis, while the x-axis depicts genes ordered by their chromosome location. Chromosomal regions with CNA are highlighted in red. B Post-translational buffering of protein complex subunits (CORUM 4.0) encoded by genes with reported copy number alterations between the A2780Cis (resistant) and A2780 (parental) cell lines, revealed by mRNA and kdeg fold change correlation analysis. Statistical analysis was performed using a two-sided Fisher’s z-test. Pearson’s correlation coefficients (R) and the number of proteins (N) are shown. The dark red line represents a linear fit to the data with 95% confidence intervals (pink). C Selected examples of protein complexes with significant mRNA-kdeg correlation (P < 0.05; Pearson correlation with two-sided t-test) and at least 3 subunits affected by CNA. N indicates the number of CNA subunits/total number of subunits per complex; the percentage shows the proportion of CNA subunits. The dark red line represents a linear fit to the data. D Gene-level GO Biological Process enrichment analysis performed by Metascape (https://metascape.org). “Gain” and “Loss” indicate the gene copy number change in A2780Cis. “Amplification” and “Buffering” indicate the direction of protein degradation regulation in A2780Cis relative to “Gain” or “Loss”; i.e., “Gain + Amplification” and “Gain + Buffering” indicate that protein degradation tended to be downregulated and upregulated, respectively, and vice versa in the “Loss” cases. The P values were estimated using a hypergeometric test. Protein degradation rates were estimated using our pipeline with GroupQ filtering in SN19. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To further explore post-translational buffering mechanisms associated with aneuploidy, we focused on genes affected by CNA, comparing those that encode protein complex subunits (CORUM 4.040) with those that do not. We examined the correlation between mRNA and kdeg, which may serve as a more sensitive indicator of proteome buffering than the protein-kdeg correlation as we showed previously5. Remarkably, proteins encoded by CNA-affected genes involved in complexes exhibited a significantly stronger mRNA-kdeg correlation (R = 0.537) compared to CNA-affected proteins not participating in protein complexes (R = −0.05, P = 1.83e−9, Fisher’s z-test, Fig. 5B). This difference provides compelling evidence for large-scale proteome buffering in this highly aneuploid system, achieved by stabilizing protein complex stoichiometry through regulated protein turnover between A2780Cis and A2780 cells. We further analyzed the mRNA-kdeg correlation within individual protein complexes (Fig. 5C, Supplementary Fig. 6A, B), revealing an overall preference for protein complex buffering (Supplementary Fig. 6A, B). Our results supported a strong buffering of CNA-affected subunits of key complexes involved in RNA transcription (Mediator complex and RNA polymerase II), splicing (Spliceosome E), or cell division (CEN complex, Fig. 5C).

While degradation acts to buffer the effects of aneuploidy, it may also actively remodel the proteome to support cisplatin resistance. Prolonged low-dose cisplatin exposure in A2780 cells likely imposed selective pressure, driving genomic and proteomic adaptation. Accordingly, changes in gene copy number, protein abundance, and degradation in A2780Cis cells may directly contribute to the resistant phenotype. To evaluate their functional impact, we performed a gene ontology biological process (GOBP) enrichment analysis using Metascape following the genome rearrangement (Fig. 5D). Notably, processes involving large protein complexes, such as “ribosome biogenesis,” “mRNA processing,” “regulation of translation,” “RNA splicing,” and “cell division” were enriched among gained or lost genes that were buffered (or buffered in both directions), indicating that these protein degradation regulations counteracted CNA changes, consistent with the buffering patterns observed in Fig. 5B, C. Strikingly, many biological processes enriched among genes with increased copy number were further amplified at the protein level via decreased degradation, such as “regulation of DNA-binding transcription factor activity”, “mitochondrion organization”, or “ubiquitin-dependent protein catabolic process” — several of which have been previously linked to cisplatin resistance41,42. Furthermore, “DNA repair”, a well-established contributor to cisplatin resistance43,44,45,46, was enriched among both gain and loss groups, particularly among genes whose protein levels were shaped by turnover (“gain + amplified” and “loss + buffered”). This suggests a direct post-translational mechanism contributing to resistance. Among them were MCM8 and RRM2B, two proteins previously shown to enhance cisplatin resistance47,48. Together, our results show that protein degradation in A2780Cis cells not only buffers proteome imbalances caused by aneuploidy but also facilitates adaptive remodeling of key pathways that promote cisplatin resistance.

Cisplatin resistance in A2780Cis cells involves protein degradation-mediated mitochondrial adaptation

Beyond proteome buffering and amplification linked to CNA, we explored the functional role of protein turnover underlying the drug-resistant phenotype. Statistical analysis identified proteins with significantly altered abundance and degradation rates in A2780Cis cells as illustrated in volcano plots (Supplementary Figs. 5D, S5E, Supplementary Data 1). In total, we identified 1961 proteins with significant changes in abundance and 1356 proteins with significantly altered degradation rates; only 407 proteins commonly regulated in both datasets (BH adjusted FDR < 0.05 and |fold change|> 1.5, Fig. 6A). This finding suggests that both protein abundance and protein turnover regulation are important parts of the drug-resistant proteotype, highlighting the value of measuring protein turnover in this system. Further analysis revealed that among proteins with increased kdeg, significantly downregulated proteins were over-represented (N = 75, enrichment factor = 2.42, P = 1.5e−14), while upregulated proteins were not enriched (N = 25, enrichment factor = 0.87, P = 0.06, Fisher’s exact test). Conversely, proteins with decreased degradation rates were enriched for upregulated proteins (N = 188, enrichment factor = 1.32, P = 3.86e−6) and depleted for downregulated ones (N = 125, enrichment factor = 0.81, P = 0.0006, Fisher’s exact test), demonstrating coordinated regulation of protein degradation and abundance (Fig. 6B). To elucidate relevant protein functions, we performed Metascape enrichment analysis49, which revealed a densely interconnected protein cluster significantly enriched in pathways such as “ATP synthesis coupled electron transport” (P = 7.94e−30) and “Oxidative phosphorylation” (P = 3.16e−31), primarily composed of proteins with increased degradation rates and decreased protein abundance underlying drug resistance (Fig. 6E, Supplementary Data 2).

A Number of significantly regulated proteins at the abundance and degradation levels (Benjamini–Hochberg FDR < 0.05, absolute fold change ≥1.5; two-sided moderated t-test). B Significantly up- and downregulated proteins (from A) at abundance and degradation (kdeg) levels, including overlaps (generated using Metascape). C 2D enrichment analysis of gene ontology biological process (GOBP) terms using log2 fold changes at the protein abundance and degradation levels between A2780Cis and A2780 cell lines. Shown are the top 25 terms (P < 0.01, >9 proteins). Circle size indicates protein count; color reflects -log10(P) from two-sided 2D enrichment test (Perseus 1.6.14.0). D 1D enrichment analysis (Perseus 1.6.14.0) of mitochondrial Gene Ontology Cellular Component (GOCC) terms. Enrichment scores are color-coded; asterisks denote significance. The exact two-sided Wilcoxon test P-values and data distributions are shown in Supplementary Fig. 7. The figures were adapted from components Created in BioRender. Liu, Y. (2025) https://BioRender.com/7y30v3c’. E A protein cluster identified using MCODE analysis (performed using Metascape) of the protein-protein interaction (PPI) network of significantly regulated proteins (from B). Node colors indicate up/down-regulation at the abundance and degradation levels. F Genes associated with cisplatin sensitivity identified via correlation analysis in DepMap were mapped to protein abundance and degradation data. Proteins significantly regulated at both levels with opposing trends are highlighted. G Precursor-level H/L ratio scatter plots for NDUFB11 in A2780 (left) and A2780Cis (right). The slope (“a”) of the linear fit estimates the protein-level ratio (generated by Spectronaut). H NDUFB11 mRNA expression negatively correlates with cisplatin IC50 in the GDSC1 dataset, indicating lower expression is associated with increased resistance. Linear fit (dark red) and 95% confidence interval (pink) are shown. Pearson correlation and two-sided t-test were used. Protein degradation rates were estimated using our pipeline with GroupQ filtering in Spectronaut v19. Source data are available in the Source Data file.

Next, we conducted a two-dimensional (2D) GOBP enrichment analysis using relative changes in protein abundance and degradation rates between A2780Cis and A2780 cells (Fig. 6C, Supplementary Data 3). The correlation between median log2 fold changes for significant GOBP terms was weakly negative (R = −0.244), indicating that the cross-layer functional regulation tends to be overall concordant. Several processes, such as the “TCA cycle”, “lipid homeostasis”, “cell redox homeostasis”, and “oxidation-reduction process,” showed increased abundance and reduced turnover. Notably, the latter two align with previously reported cisplatin resistance mechanisms44,50. Conversely, proteins involved in “mitochondrial respiratory chain complex I” or “translation” displayed decreased abundance and increased turnover, consistent with the Metascape results.

Mitochondria are central to cellular energy production and can dynamically adapt to support tumor survival and drug resistance51. Given the degradation-mediated alteration in complex I, we examined other mitochondrial compartments and complexes. GOCC analysis revealed significantly reduced protein abundance in respiratory complexes I, IV, and V, but not complexes II and III (Fig. 6D, Supplementary Figs. 6E, 7B). Moreover, complexes I and IV also showed significantly increased degradation rates (Fig. 6D, Supplementary Figs. 6E, 7B), supported by CORUM complex enrichment analysis (Supplementary Fig. 6C). In contrast, the mitochondrial proteome and mitochondrial matrix proteins exhibited a slight but statistically significant increase in abundance and reduced degradation (Fig. 6D, Supplementary Fig. 7A), suggesting selective metabolic remodeling rather than changes in total mitochondrial mass. Importantly, these findings are consistent with previous reports implicating respiratory chain complexes in drug resistance42,52,53,54 (Supplementary Fig. 6E).

Finally, we investigated the protein and proteostasis profiles of genes associated with cisplatin resistance. We utilized the DepMap portal55 to identify genes significantly associated with cisplatin sensitivity by examining the correlation between transcript abundance and cisplatin response (N = 414, P < 0.01). Notably, 107 of these genes were mapped to our proteomic datasets, and numerous proteins showed significant regulation either at the protein abundance or degradation level (Fig. 6F, Supplementary Data 4). In this list, proteins showing significant regulation at both levels with opposite directions—upregulation in one accompanied by downregulation in the other—are more likely to serve as key mediators of cisplatin drug resistance. Intriguingly, we found that NDUFB11, a mitochondrial complex I protein, was the only protein to display significantly increased degradation alongside decreased protein abundance (Fig. 6G). The DepMap data revealed a negative correlation between NDUFB11 transcript levels and cisplatin sensitivity across 154 cell lines (Fig. 6H), validating that its reduced protein abundance, potentially driven by increased turnover, is associated with, or may contribute to, enhanced drug resistance in the A2780Cis cell line. Moreover, MBNL1 and OXSM, which exhibited increased protein levels and reduced degradation rates in the resistant cells (Supplementary Fig. 5H), showed positive correlation with cisplatin resistance according to DepMap transcript profiles (Supplementary Figs. 5F, G), reinforcing their potential roles in mediating cisplatin resistance as well.

In conclusion, our findings highlight the strong relationship between protein turnover and cisplatin resistance, with key proteins involved in mitochondrial function, redox homeostasis, and oxidative phosphorylation showing significant regulation.

Discussion

Multiplex-DIA-MS, when integrated with pSILAC8,9,10,11, enables high-performance protein turnover analysis across multiple time points under various biological conditions5,12,13,14,16,18,56,57,58. This approach is particularly well-suited for time-course designs in pSILAC experiments, due to the reproducible profiling of large numbers of peptides. Recent advances in library-free DIA-MS data analysis, powered by machine and deep learning22,23,24, have dramatically enhanced the applicability of DIA-MS measurement by removing the necessity of generating extensive project-specific spectral libraries in many scenarios, making DIA-MS workflows more efficient and scalable for complex proteomic studies. Herein, we showed that the LBL workflow in Spectronaut significantly advanced multiplex-DIA-MS data analysis, particularly for pSILAC experiments. Unlike earlier methods that focus on a single channel for signal extraction, LBL takes a flexible approach by integrating data across all labeling channels. During the stages of peak picking and elution group scoring, LBL considers both channel-specific and cross-channel metrics to extract more comprehensive and reliable signals. Moreover, it fully leverages the label-free directDIA+ algorithm in Spectronaut23, eliminating the need for creating a project-specific spectral library. Indeed, we demonstrated that LBL outperformed ISW in the analysis of multiple labeling datasets, significantly and consistently identifying more precursors and protein groups across various conditions and sample compositions. Notably, we demonstrated improved identification with LBL in standard experiments that included two and three labeling channels that could theoretically extend to N channels. This is particularly promising as the interest in multiplexing DIA-MS continues to grow, with new reagents being developed in the future to potentially leverage additional channels for more intricate experiments, such as single-cell proteomics7,59. We also demonstrated the effectiveness of LBL across two MS platforms, suggesting that LBL will remain valuable as mass spectrometry technologies evolve. On the other hand, strategies like ISW or “Spike-in” (with the heavy sample as the reference) may still be suitable for specific experiments such as those using spike-in standards60.

Proper FDR control is critical in multiplex-DIA experiments to ensure reliability and accuracy of the protein quantifications across multiple labeling channels. LBL leverages machine learning to calculate both cross-channel and channel-specific scores. These enable channel-specific FDR filtering of the quantification results with three q-value filtering options available in Spectronaut: GroupQ, MinQ, and MaxQ, which accommodate different user preferences for data filtering. Based on our results, the GroupQ (integrative cross-channel q < 0.01) and MinQ (at least one channel q < 0.01) offered higher sensitivity by retaining more quantification data, while MaxQ (each channel q < 0.01) provided more stringent filtering and improved precision at the cost of reduced sensitivity. This data loss following the MaxQ setting might be especially impactful in studies focusing on low-abundance proteins or peptide-level quantification12,15,56. Thus, for studies that prioritize sensitivity, the GroupQ or MinQ options may be more appropriate, while those aiming for the highest level of precision and confidence in their quantification may benefit from using MaxQ, albeit with reduced overall data retention. However, it is important to note that the GroupQ and MinQ results practically encompass almost all MaxQ results, and that Spectronaut offers flexibility with these filtering options, allowing users to tailor their analyses to specific experimental requirements. For example, certain experiments, such as those using a booster sample channel, might benefit from channel-specific q-value filtering6.

To provide a user-friendly and flexible workflow for analyzing pSILAC data obtained through multiplex-DIA-MS, we developed the R package KdeggeR. A few software tools have been developed previously, among them proturn57, which offers a user-friendly Shiny app and was primarily designed for pSILAC-TMT experiments; JUMPt61, which calculates protein turnover rates using a differential equation-based model to account for amino acid recycling, and is particularly useful in in vivo studies such as mouse models; SPLAT, which enables a more specialized workflow for simultaneous protein localization and turnover analysis (https://lau-lab.github.io/splat/); and turnoveR, which was designed to work with SVM files and Massacre output (https://github.com/KopfLab/turnoveR). While some of these existing packages enable the estimation of protein degradation rates from pSILAC-DIA data, they often require manual data pre-processing. KdeggeR offers an alternative and more streamlined workflow by handling data import and peptide-to-protein processing with various options, as well as providing a series of data visualization functions within a single package. A limitation of KdeggeR is its current inability to account for amino acid recycling, which can be critical in in vivo systems and is already provided by other software tools such as JUMPt, ApplE, and others61,62,63. Nevertheless, the current version of KdeggeR was designed to provide optimal analysis for pSILAC-DIA experiments in cultured cell models, allowing protein lifetime inference using several models and even in the absence of measured cell doubling times.

We applied our full workflow to study the potential contribution of protein turnover to the development of a drug-resistant phenotype in A2780 cells, which exhibit extensive cytogenetic changes31. Our results confirmed large-scale protein complex buffering32 through protein degradation, as previously observed in states of genome imbalance14. We observed that proteins encoded by CNA-affected genes involved in complexes exhibited a much stronger positive mRNA-kdeg correlation compared to those not involved in complexes, underscoring the utility of mRNA-kdeg correlation in aneuploidy research. However, such buffering was not universal to all proteins participating in protein complexes. In our model, cells selectively up- or downregulated specific complexes following cisplatin exposure/aneuploidy to establish new homeostasis and therefore did not buffer all transcript-level variation through protein degradation. In fact, some pathways appeared “amplified” by protein degradation. For instance, we observed that “DNA repair” genes were enriched among the “Gain” regions and at the same time showed reduced protein degradation rates (i.e., the gain genotype was “amplified” by protein degradation), while the opposite was observed for “Loss” genes. These findings align with the role of DNA repair pathways in cisplatin resistance30,43,46,64, supporting a direct link between CNA and resistance and suggesting that protein degradation helps shape CNA-driven pathways toward a resistant phenotype. Furthermore, key pathways such as oxidative phosphorylation and ATP synthesis, and mitochondrial complex I were significantly enriched among proteins with increased degradation rates and reduced abundance, while matrix-localized pathways such as the TCA cycle and fatty acid β-oxidation showed the opposite trend. Previously, both complex I42,52,53 and complex IV54 proteins have been associated with cancer drug resistance and several complex I encoding genes have been proposed to regulate cisplatin resistance in a genome-wide siRNA screening42, supporting our findings. This mitochondrial adaptation in A2780Cis might be attributed to redox regulation57,65,66, as supported by our observation of increased abundance and reduced turnover of proteins involved in redox homeostasis—an axis previously implicated in cisplatin resistance44,50. However, the precise pathways and regulatory networks involved warrant further investigation.

Finally, we employed the DepMap portal55 to identify genes associated with cisplatin sensitivity. Of particular interest was NDUFB11, a mitochondrial electron transport chain protein that exhibited increased degradation and decreased abundance. This further directly supports that altered turnover of mitochondrial proteins may contribute to drug resistance and could present potential therapeutic targets. The DepMap results also strongly supported MBNL1 and OXSM, which showed increased protein levels and reduced degradation rates, potentially contributing to the cisplatin resistance. Further verification experiments are required to establish the functional linkage between these synergistic protein level regulations and cisplatin effects.

In conclusion, our workflow integrating multiplex-DIA-MS with pSILAC significantly enhances protein turnover quantification across multiple labeling channels. These advancements will facilitate similar future studies utilizing widely used DIA tools such as Spectronaut and offer valuable insights into biological mechanisms, such as drug resistance and aneuploidy research.

Methods

Reagents and resources

The chemicals, equipment, instruments, and software tools used in this study, including their catalogue and version numbers, are provided in Supplementary Data 5.

Sample sets

A2780 standard dilution sample set (2-channel SILAC)

This sample set was measured in our previous study18. Ovarian cancer cell line A2780 (93112519, Sigma) was cultured for at least eight passages in media containing 13C615N4-Arg and 13C615N2-Lys to reach >99% labeling efficiency (as evaluated by MS)18. The sample set included the following H/L dilutions: 1:16, 1:8, 1:4, 1:2, 1:1, 2:1, 4:1, 8:1, and 16:1 in one replicate. The detailed sample preparation and LC-DIA-MS protocol can be accessed in the original protocol, and the raw files are provided at ProteomeXchange (PXD021922). In brief, the 4-h LC-MS method consisted of an MS1 survey and 33 MS2 scans of variable windows12 on an Orbitrap Fusion Lumos Tribrid mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific).

HeLa standard dilution sample set (3-channel SILAC)

This sample set included data from a published study25 and downloaded from ProteomeXchange (PXD039578). HeLa cells (CCL-2; ATCC) were grown in high-glucose DMEM with dialyzed fetal bovine serum, supplemented with heavy (13C615N4-Arg, 13C615N2-Lys), intermediate (13C6-Arg, D4-Lys), or light (unlabeled) lysine and arginine for 10 days. The H:M:L composition of the mix 1 sample was 15:15:70, and the composition of the mix 2 sample was 40:40:20. Each sample was analyzed in triplicate using LC-DIA-MS, as described in the original paper (MS2-optimized; see ref. 25 for details). In brief, a 105-min method was used, which included an MS1 survey followed by 26 MS2 DIA scans of equally sized windows of 23.3 m/z on a Q Exactive HF mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific).

Fibroblast pSILAC sample set (2-channel pSILAC)

The skin fibroblast cell lines were purchased from the Coriell Institute for Medical Research (GM06113, GM06170). The two cell lines are referred to as cell line #54 and cell line #55 in the current manuscript. The cells were cultured at 37 °C and humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere in complete MEM medium supplemented with L-glutamine, 15% fetal bovine serum, and penicillin-streptomycin. Cells were seeded on 6-well dishes in complete growth medium at a density of 15,000 cells per cm2. After 24 h, the cells were washed and subjected to pulse SILAC labeling for 1, 4, 8, 12, and 24 h. The SILAC MEM medium was supplemented with 15% dialyzed FBS, penicillin-streptomycin, L-proline (200 mg/L), 13C615N4-Arg, and 13C615N2-Lys. The dishes were washed with PBS, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and the cells were scraped into 100 µL of cell lysis buffer containing 10 M urea, 100 mM ammonium bicarbonate, cOmplete™ protease inhibitor cocktail, and Halt phosphatase inhibitors. The collected samples in one replicate were snap-frozen and stored at −80 °C before further processing.

Parental and cisplatin-resistant A2780 cell sample set (2-channel pSILAC)

The A2780 (parental cell line; 93112519, Sigma) and A2780Cis (cisplatin-resistant cell line; 93112517, Sigma) were cultured in RPMI medium supplemented with 2 mM glutamine, 10% FBS, and penicillin-streptomycin. Additionally, the A2780Cis cell line was cultured in the presence of 1 µM cisplatin. After switching to SILAC heavy medium (13C615N4-Arg and 13C615N2-Lys)18, both cell lines were harvested in biological triplicate at 1, 4, 8, and 12 h of labeling. Additionally, a triplicate sample was harvested at time point 0 to analyze the total proteomes. The dishes were washed with PBS, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and the cells were scraped into 200 µL of cell lysis buffer containing 10 M urea, 100 mM ammonium bicarbonate, cOmplete™ protease inhibitor cocktail, and Halt phosphatase inhibitors. The collected samples were snap-frozen and stored at −80 °C before further processing.

Protein extraction and digestion

Cell pellets in lysis buffer (all A2780 and fibroblast sample sets) were thawed and sonicated at 4 °C twice for 1 min each using a VialTweeter device (Hielscher-Ultrasound Technology)13. Afterward, the samples were centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 1 h to separate insoluble materials. Protein concentrations in the resulting supernatant were measured using the Bio-Rad protein assay. Each protein sample was diluted to a final concentration of 2 μg/μl, reduced with 10 mM DTT at 56 °C for 1 h, and alkylated with 20 mM IAA in the dark at room temperature for 1 h. Reduced and alkylated proteins underwent precipitation-based digestion (for parental and cisplatin-resistant A2780 cell sample set) or in-solution digestion (for fibroblast pSILAC sample set), with respective protocols described previously13,67. For the precipitation-based digestion, five volumes of a cold precipitation solution (50% acetone, 50% ethanol, and 0.1% acetic acid) were added to the protein mixture, and the samples were stored at −20 °C overnight. The precipitated proteins were collected by centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 40 min, washed with cold 100% acetone, and centrifuged again under the same conditions. Following acetone removal, residual acetone was evaporated in a SpeedVac. The proteins were then digested overnight at 37 °C with sequencing-grade porcine trypsin at a 1:20 enzyme-to-substrate ratio in 300 μl of 100 mM ammonium bicarbonate. For the in-solution digestion, the protein samples were diluted five times with 100 mM ammonium bicarbonate prior to the addition of trypsin in a 1:20 enzyme-to-substrate ratio. The final peptide mixture was acidified with formic acid and desalted using C18 columns (MacroSpin Columns, NEST Group Inc.) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The peptide yield was quantified using a NanoDrop (Thermo Scientific).

Mass spectrometry measurements

Orbitrap fusion lumos platform

For LC-MS analysis, 1.5 μg of the peptide mixture (from all the sample sets) was analyzed as previously described13,68. Peptide separation was carried out using an EASY-nLC 1200 system (Thermo Scientific) with a self-packed PicoFrit column (New Objective, Woburn, MA, USA; 75 μm × 50 cm) containing ReproSil-Pur 120 A C18-AQ 1.9 μm resin (Dr. Maisch GmbH, Ammerbuch, Germany). Peptides were eluted over a 150-minute gradient using buffer B (80% acetonitrile, 0.1% formic acid) from 5% to 37%, with buffer A (0.1% formic acid in water) as the corresponding solvent. The flow rate was set to 300 nl/min, and the column was maintained at 60 °C using a column oven (PRSO-V1; Sonation GmbH, Biberach, Germany). The separated peptides were analyzed on an Orbitrap Fusion Lumos Tribrid mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific) equipped with a NanoFlex ion source, with a spray voltage of 2000 V and a capillary temperature of 275 °C. The DIA-MS method included an MS1 survey scan followed by 33 MS2 scans with variable windows, as described previously23,69. The MS1 scan range was 350–1650 m/z with a resolution of 120,000 at m/z 200. The MS1 AGC target was set to 2.0E6, with a maximum injection time of 100 ms. For MS2, the resolution was set to 30,000 at m/z 200, with a normalized HCD collision energy of 28%. The MS2 AGC target was 1.5E6, and the maximum injection time was 50 ms. The default peptide charge state was set to 2. Both MS1 and MS2 spectra were recorded in profile mode.

timsTOF Ultra platform (fibroblast pSILAC dataset)

Peptides (130 ng) from fibroblast pSILAC sample set were separated using a 52-min ACN gradient on a 25 cm × 75 µm column (Ion Opticks) using a nanoElute2 LC. The LC system was connected via a CaptiveSpray Ultra source to trapped ion mobility – quadrupole time-of-flight MS (timsTOF Ultra, Bruker Daltonics). The MS was operated in dia-PASEF mode70 with 3 PASEF mobility scans, each with 20 DIA variable windows (a “20 × 3” method; Bruker Daltonics)71.

Mass spectrometry data processing

Label-free DIA-MS data analysis

The label-free data analysis was performed in Spectronaut v19 using directDIA+23 by searching against the human SwissProt sequence database (N = 20,399 entries, downloaded in September 2022) and the default Spectronaut settings39. Briefly, the Trypsin/P was used as a cleavage rule with up to 2 missed cleavages; “Carbamidomethyl (C)” was set as a fixed modification, and “Acetyl (Protein N-term)” and “Oxidation (M)” were set as variable modifications; Top 3–6 Best N Fragments per peptide were enabled. The precursor q-value and the experiment-wide protein q-value were set to 0.01, and the run-wise protein q-value was set to 0.05. The quantification was performed at the MS2 level, and the cross-run normalization was enabled. The peptide and protein quantification were performed using max Top 3 precursors and max Top 3 stripped peptide sequences, respectively. The “Minimum Log2 Precursor Quantity” was set to 3.

Multiplex-DIA data analysis using the “Labeled” workflow (LBL)

The multiplex-DIA data analysis was performed in Spectronaut v19 using the library-free “Labeled” workflow. The analysis was performed using directDIA+ against a human SwissProt sequence database (N = 20,399 entries, downloaded in September 2022) using the default settings with modifications as described below. The search parameters were kept the same in all datasets across MS platforms.

In the Pulsar Search: Trypsin/P was used as a cleavage rule with up to 2 missed cleavages; the labeling was set to two channels with no labels specified in Channel 1 and “Arg10” and “Lys8” specified in Channel 2; “Carbamidomethyl (C)” was set as a fixed modification, and “Acetyl (Protein N-term)” and “Oxidation (M)” were set as variable modifications; in the Workflow tab, the “In-Silico Generate Missing Channels” option was enabled with “label” as a Workflow; in the Result Filters tab, Top3–6 Best N Fragments per Peptide were used, and the “Overlapping between Channels” was enabled to exclude fragments shared between channels for the accurate estimation of channel-specific FDR. For the analysis of dimethyl-labeling mDIA samples downloaded from a previous study6, most parameters were kept identical, but the labeling was set as follows: “DimethLys0” and “DimethNter0” in Channel 1, “DimethLys4” and “DimethNter4” in Channel 2, and, when applicable, “DimethLys8” and “DimethNter8” in Channel 3 (3-plex experiment).

In the DIA Analysis: in the Identification tab, the precursor q-value and the experiment-wide protein q-value were set to 0.01, the run-wise protein q-value was set to 0.05; in the Quantification tab, the Multi-Channel Q-value filter was either set to “Group Q-value”, “Max Q-value”, or “Min Q-value” to evaluate channel-specific q-value filtering options. For the analysis presented in Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. 1, this parameter was kept as “Group Q-value” (as it is the default option for the LBL in Spectronaut). The quantification was performed at the MS2 level, and the cross-run normalization was enabled. The “Exclude All Multi-Channel Interferences” option was enabled. The peptide and protein quantifications were performed using max Top 3 precursors and Top 3 stripped peptide sequences, respectively. The “Minimum Log2 Precursor Quantity” was set to 3. In the Workflow tab, the “Multi-Channel Workflow Definition” was set to “Labeled”.

Please see Supplementary Note 1 in the supplementary file for a detailed step-by-step protocol.

Multiplex-DIA data analysis using the “Inverted Spike-In” workflow (ISW)

The ISW analysis was performed in the same Spectronaut v19 version by selecting the following parameters: the “Multi-Channel Workflow Definition” was set to “Spike-In”, and both “Inverted” and “Reference-based Identification” were enabled. Other parameters were kept as described in the section above, describing the LBL workflow.

Multi-channel experiment processing and scoring in spectronaut

Spectronaut organizes all channels corresponding to a given peptide into “elution groups,” representing a group of peptide precursors expected to elute simultaneously. Extracted ion chromatograms (XICs) are obtained for each group from the relevant MS2 scans. The peak-picking strategy depends on the specific multi-channel processing mode selected. By default, Spectronaut utilizes the “Labeled” workflow for multi-channel elution groups, in which XIC peak picking is performed across all channels in a combined fashion. Each peak is assigned scores based on both channel-specific and cross-channel features, for both MS1 and MS2 data. Note that the data extraction is always performed per MS2 window, and Spectronaut does not perform any channel-specific quantification correction for peptides that span multiple MS2 windows.

The final score per elution group is determined during the machine learning step, with the strategy being workflow dependent. In the “Labeled” workflow (LBL), all channels, along with their specific and cross-channel scores, are considered collectively in the machine learning process, allowing for dynamic adaptation to systematic changes in channel ratios, which are common in pSILAC experiments. These scores are then used to compute the “Group Q-value” for each elution group. Additionally, channels are scored independently based on channel-specific metrics, which are used to determine channel-specific q-values. However, within Spectronaut and for all post-processing steps, all channels of an elution group are always treated as a unified group. Quantification is always performed for all channels of a group that is considered identified based on their shared RT peak boundaries, and the fragment ion selection is always synchronized across all channels and samples. Therefore, all multi-channel q-value filtering options will always exclude or include the entire group of channels within one run, based on the user’s preferences. Note, since this filtering is performed at the precursor level, the quantification of an elution group (and thus the ratios between the channels) will be identical for those precursors passing the FDR filtering by multiple options. Finally, in an experiment containing more than one sample, the elution groups are scored within individual samples and only accepted/reported if they pass the selected quantification filtering in individual samples. The only exemption from the whole elution group filtering rule is an additional “ChannelQ” filtering option, which performs elution group identification using the elution group scoring and then filters the individual channels based on their channel-specific q-value (Supplementary Fig. 1G). This function is intended as an additional pre- and post-analytical quality control option. Please see Supplementary Note 1 for details.

Furthermore, when enabled in the Quantification settings, a cross-run normalization is performed per elution group based on the assumption that the majority of all signals do not show any systematic trend across measurements, and the normalization is performed according to this assumption. In the case of a multi-channel experiment, the sum over all channels is considered as the group’s quantity that needs to be normalized.

Spectronaut result reporting

Label-free DIA-MS data

For the total proteome analysis, the data were exported using the protein pivot report using “PG.ProteinGroups” as the unique protein ID and the “PG.Quantity” as the quantification column.

Multiplex-DIA-MS data

The precursor/elution group (EG) level pivot report was exported. The “EG.Channel1Quantity” and “EG.Channel2Quantity” (for a 2-channel experiment), and “EG.Channel3Quantity” (for a 3-channel experiment) quantities were used as quantification values, and the “EG.PrecursorId” column was used as the unique precursor ID column. For protein-level quantification of the multiplex-DIA-MS data, the precursor-level ratios were estimated first as the ratios between the channels, and then the protein-level ratios were calculated as the median value of all precursor-level ratios corresponding to a unique protein ID (“PG.ProteinGroups”). In all replicate experiments (HeLa 3-channel, A2780 pSILAC), the replicates were aggregated to obtain an average ratio by calculating the means and CVs of non-transformed ratio values after filtering for precursor values quantified in all 3 replicates. Please refer to Supplementary Note 3 in the supplementary file for details on data reporting.

Multiplex-DIA-MS data analysis using DIA-NN

To benchmark the multiplex-DIA-MS analysis in Spectronaut, we additionally analyzed the data using DIA-NN (version 1.9)22 using the plexDIA recommended workflow7 and largely followed the parameters used previously to analyze the 3-channel HeLa standard sample experiment25. A predicted spectral library was generated using the default settings from the same FASTA file used for Spectronaut searches and the same fixed and variable modifications. For raw data analysis, the default settings were used, along with additional commands necessary to analyze a plexDIA experiment (https://github.com/vdemichev/DiaNN). Specifically, the SILAC channels were registered, depending on the 2- or 3-channel experiment, corresponding to Lysine and Arginine mass shifts: Lys (+4.025107 Da), Lys8 (+8.014199 Da), Arg6 (+6.020129 Da), Arg10 (+10.008269 Da). Retention time translation between peptides within the same elution group was enabled. Both the first 13C-isotopic and monoisotopic peaks were included for quantification, with MS1 deconvolution level set to 2. Peptide lengths ranged from 7 to 30 amino acids, precursor charge states ranged from 1 to 4, and the precursor mass-to-charge (m/z) range was set between 300 and 1800, with a fragment ion m/z range from 200 to 1800. The precursor false discovery rate (FDR) was set to 1%. Precursor matrix output tables were filtered for FDR < 0.01, as well as for channel-specific (“--matrix-ch-qvalue”). The match-between-runs (MBR) function in DIA-NN was enabled. The precursor-level matrices were used for the downstream analyses (“report.pr_matrix_channels.tsv”).

Determination of protein degradation rates from the pSILAC experiments using KdeggeR

Protein degradation rates reported in this manuscript were calculated using the KdeggeR 1.0 package following an algorithm based on the nls fitting in the relative light isotope abundance values (RIALight) at the precursor level as described previously5,11,13,27,28,29 and subsequent averaging to the protein-level rates of loss and degradation. The main steps are described below, together with the description of additional options and functionalities of the package. The package is provided via GitHub (https://github.com/yslproteomics/KdeggeR); see the package documentation for details on the functions and parameters.

Data import, formatting, and filtering

The precursor-level report from, e.g., Spectronaut, was imported, and the channel intensity values were filtered to remove low-intensity signals (e.g., with log2-transformed intensity <8). Note that this filtering significantly improves data quality in our datasets and is recommended performing in the multi-channel data analysis in Spectronaut by default, using the “Minimum Log2 Precursor Quantity” quantification filter. Next, the H/L ratios were calculated and further filtered based on i) valid values (e.g., at least 2 in time points 4, 8, and 12 h for the parental and cisplatin-resistant A2780 cell sample set), ii) increasing trend over the time points, and iii) outlier detection in the first time point based on the identification of significant outliers using linear regression. To do so, we fitted a linear model using log-transformed H/L ratios (ln (H/L + 1)) from time points 4, 8, and 12. We then calculated residuals of the fit for each time point, including the first time point. Grubbs’ test was used to detect significant outliers from the residual distribution at time point 1.

Estimation of precursor-level kloss values using the RIA method

At each time point, the amount of heavy (H) and light (L) precursor was extracted and used to calculate the relative isotopic abundance RIAt.

The value of RIAt changes over time as unlabeled proteins are gradually replaced by heavy-labeled proteins throughout the experiment. This occurs because of cell division, which dilutes the unlabeled proteins, and the natural turnover of intracellular proteins, where the loss rate can be described by an exponential decay process.

Where RIA0 denotes the initial isotopic ratio and kloss the rate of loss of unlabeled protein. We assumed RIA0 = 1, as no heavy isotope was present at t = 0, thus, the value of RIAt will decay exponentially from 1 to 0 after infinite time, and we used nonlinear least‐squares estimation to perform the fit. As discussed previously11, these assumptions may reduce measurement error, especially at the beginning of the experiment, where isotopic ratios are less accurate.

Estimation of precursor-level kloss values using the NLI method

A simpler approach to determine de facto protein degradation rates is to directly calculate the rate of loss from the light peptide intensities. The light peptide intensities need to be normalized using median channel sums to calculate the normalized intensity values (NLI). Then, the light precursor rate of loss can be modeled using the same model and assumptions as in the case of the RIA-based modeling. As we reported previously, the NLI and RIA methods’ results are strongly correlated; however, the NLI method tends to have higher variability5.

Estimation of precursor-level kloss values using the HOL method

The heavy proteins are synthesized over time, leading to an increasing H/L ratio. This process is exponential because the heavy proteins are gradually replacing the unlabeled (light). The H/L ratios are linearized by log-transformation, and the rate of incorporation of the heavy label is then estimated using a linear model.

In the steady-state condition, the rates of protein synthesis and degradation reach equilibrium. This means that the rate at which new heavy-labeled proteins are synthesized must be balanced by the rate at which proteins are degraded (kloss).

Estimation of protein-level kloss values

Protein-level kloss values can be calculated using different options, including performing a weighted average of the selected precursor-level fit (e.g., RIA only) or their combination/complement (e.g., RIA and NLI). The number of data points used to estimate precursor-level kloss, the variance of the fit, or both can be used as weights.

Calculation of protein-level kdeg values

Protein degradation rates are estimated by subtracting the cell division rate (kcd) to correct for the protein pool dilution caused by the exponential cell division.

However, practically, the cell division rates tend to be highly variable between different experiments, and thus, the precision and accuracy tend to be low. Therefore, we enabled the option to use a value derived from the distribution of the kloss values by assuming that most kdeg values should be positive after the correction. We recommend defining kperc so that its subtraction from kloss yields no more than 1% negative kdeg values, allowing robust estimation in cell culture-derived datasets. Note that this transformation will result in the preselected proportion of negative values in the data, and they need to be replaced by NA for further analysis.