Abstract

An unusual family of bifunctional terpene synthases has been identified in which a prenyltransferase assembles 5-carbon precursors to form C20 geranylgeranyl diphosphate (GGPP), which is then converted into a polycyclic product by a cyclase. Here, we report the cryo-EM structure of a massive, 495-kD bifunctional terpene synthase, variediene synthase from Emericella variecolor (EvVS). The structure reveals a hexameric prenyltransferase core sandwiched between two triads of cyclases. Surprisingly, GGPP is not channeled intramolecularly from the prenyltransferase to the cyclase, but instead is channeled intermolecularly to a non-native cyclase as indicated by substrate competition experiments. These results inform our understanding of carbon management in the greater family of bifunctional terpene synthases, hundreds of which have been identified in fungi. Using sequence similarity networks, we also report the identification of bifunctional terpene synthases in an animal, Adineta steineri, a bdelloid rotifer indigenous to freshwater environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Terpenes represent the largest class of natural products and play many roles in nature, such as the deterrence of herbivores1,2 and the attraction of pollinators3. Terpenes also have myriad industrial and medicinal uses, e.g., in pharmaceuticals4, in flavors and fragrances5, and in biofuels6. The astonishing diversity of hydrocarbon skeletons in the terpenome is rooted in a single 5-carbon metabolite of primary metabolism, isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP)7. IPP can be isomerized to form dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMAPP)8, and then DMAPP can be combined with additional equivalents of IPP in iterative, head-to-tail condensation reactions to yield linear isoprenoids containing 5n carbons (n = 2, 3, 4…)9. These reactions are catalyzed in all domains of life by prenyltransferases that share a common α fold with conserved metal-binding motifs that coordinate to a catalytic Mg2+3 cluster10,11.

Linear isoprenoids serve as substrates for terpene cyclases that generate complex hydrocarbon scaffolds in a single enzymatic reaction with structural and stereochemical precision11,12. A class I terpene cyclase shares the α fold of a prenyltransferase with certain variations in conserved metal-binding motifs. Coordination of the substrate diphosphate group to the Mg2+3 cluster triggers ionization to form inorganic pyrophosphate (PPi) and an allylic carbocation. The initially-formed carbocation then propagates through several intermediates in a mechanistic sequence typically resulting in a product containing multiple rings and stereocenters13,14,15.

While individual prenyltransferases and terpene cyclases are found in animals16,17,18,19,20,21, plants3, fungi22, and bacteria23, hundreds of fungal terpene synthases are unusual in that they contain both a prenyltransferase and a cyclase in a single polypeptide chain24,25,26,27. Given that these enzymes catalyze sequential biosynthetic steps, they have been referred to as assembly-line terpene synthases28. Bifunctional terpene synthases are refractory to crystallization due to the flexibility of the polypeptide linker connecting catalytic domains, but individual domains have yielded X-ray crystal structures29,30. Cryo-EM studies of full-length bifunctional terpene synthases clearly reveal oligomeric prenyltransferase cores, but cyclase domains are not readily visualized – most are characterized by weak, uninterpretable, or nonexistent density31,32,33,34.

For example, negative-stain EM and cryo-EM studies of fusicoccadiene synthase from Phomopsis amygdala (PaFS) reveal that cyclase domains are randomly splayed out around prenyltransferase oligomers; however, some particles are observed with one or two cyclase domains associated with the side of the prenyltransferase oligomer31,32. Of note, the low-resolution cryo-EM structure of a PaFS variant with a spliced-out linker shows all cyclase domains locked in place on the sides of the prenyltransferase oligomer35; moreover, substrate channeling is definitively established in this variant and in wild-type PaFS35,36. In another example, cryo-EM studies of glutaraldehyde-crosslinked macrophomene synthase from Macrophomina phaseolina reveal partial densities at low resolution corresponding to some cyclase domains above and below the prenyltransferase oligomer33. Thus, the complete structure of a bifunctional terpene synthase has been elusive until now.

Here, we report the cryo-EM structure of variediene synthase from Emericella variecolor (EvVS; Fig. 1)37. Importantly, all catalytic domains of the 495-kD bifunctional synthase are visualized: the hexameric prenyltransferase core is sandwiched between triads of cyclase domains, yielding a bollard-like assembly. While the proximity of prenyltransferase and cyclase domains in this assembly might suggest the possibility of geranylgeranyl diphosphate (GGPP) channeling between active sites, we show that no intramolecular substrate channeling occurs. Therefore, GGPP is released from the prenyltransferase to bulk solution before rebinding to the enzyme for cyclization. Intriguingly, however, the individual cyclase domain of fusicoccadiene synthase (PaFSCY) does exhibit channeling when added to EvVS reaction mixtures. In other words, GGPP preferentially transits from the EvVS prenyltransferase to the non-native cyclase PaFSCY rather than being released to solution. Structural comparisons of EvVS and PaFS suggest a molecular rationale for intermolecular substrate channeling.

Results

Catalytic activity and steady-state kinetics

The catalytic activity of EvVS was first confirmed with substrate GGPP, which yields a single product previously established to be variediene37. When incubated with the 5-carbon precursors DMAPP and IPP, variediene is similarly observed, establishing that both domains are catalytically active: the prenyltransferase domain synthesizes GGPP from DMAPP and 3 equivalents of IPP, and the cyclase domain converts GGPP into variediene (Fig. S1A). No other cyclization products are observed. We also purified a separate construct comprising only the EvVS cyclase domain (EvVSCY). When incubated with GGPP, this construct exhibits similar high-fidelity variediene synthase activity, with no substantial generation of alternative diterpene products or any other product from any other isoprenoid substrate (Fig. S1B). When EvVSCY is incubated with GGPP and a range of divalent cations, maximal variediene generation is observed only with Mg2+ (Fig. S1C). Similar results were reported with the initial discovery and characterization of full-length EvVS37. Additionally, steady-state kinetics of full-length EvVS and EvVSCY reported herein show that the turnover number (kcat) of GGPP cyclization by EvVSCY is only reduced by ~50% compared with full-length EvVS (Fig. S2). Steady-state kinetic parameters measured for both constructs are comparable to those previously measured for PaFS35. Cooperativity was not observed for either construct.

To ascertain the possibility of substrate channeling between the prenyltransferase and cyclase domains of EvVS, substrate competition experiments were performed in similar fashion to those reported in our recent study of PaFS35. When an equimolar mixture of EvVS and cyclooctatenol synthase (CotB2) is incubated with GGPP, the variediene:cyclooctatenol product ratio is 1:1.1 (Fig. 2A, Table 1). When the same enzyme mixture is incubated with DMAPP and IPP, such that the only GGPP available for cyclization is that generated by the EvVS prenyltransferase, the variediene:cyclooctatenol product ratio changes only slightly to 1:0.8. While this ratio indicates that more variediene is generated when incubated with DMAPP and IPP, the increase is modest and barely outside the margin of error (Table 1); substrate channeling cannot be reliably concluded. When an equimolar mixture of EvVS and spatadiene synthase is incubated with GGPP, and then in a second experiment with DMAPP and IPP, the variediene:spatadiene product ratio is essentially unchanged at 1:0.6 and 1:0.5, respectively (Fig. 2B, Table 1). If there were GGPP channeling in full-length EvVS, more variediene would be generated in these experiments when incubated with DMAPP and IPP compared with GGPP, i.e., more of the GGPP generated by the EvVS prenyltransferase would remain on the enzyme for cyclization. Therefore, we cannot conclude that GGPP channeling occurs in EvVS. This contrasts with the results of substrate competition experiments with PaFS, where substantial fusicoccadiene enrichment is observed when incubated with DMAPP and IPP compared with GGPP35.

A When an equimolar mixture of variediene synthase (EvVS) and cyclooctatenol synthase (CotB2) is incubated with geranylgeranyl diphosphate (GGPP), variediene (VA) and cyclooctatenol (CO) are generated at a 1:1.1 ratio (trace 1). When incubated with dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMAPP) and isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP) instead, only a small change is observed in the product ratio (trace 2). B When an equimolar mixture of EvVS and spatadiene synthase is incubated with GGPP, variediene (VA) and spatadiene (SP) are generated at a 1:0.6 ratio (trace 1). When incubated with DMAPP and IPP instead, no substantial change is observed in the product ratio (trace 2). C When an equimolar mixture of EvVS and the cyclase domain of fusicoccadiene synthase (PaFSCY) is incubated with GGPP, variediene and fusicoccadiene (FS) are generated at a 1:1.1 ratio. When incubated with DMAPP and IPP instead, the variediene:fusicoccadiene product ratio is 1:5.4. Substantial enrichment of fusicoccadiene indicates that the GGPP generated by the EvVS prenyltransferase preferentially transits to PaFSCY.

When an equimolar mixture of EvVS and the cyclase domain of PaFS (PaFSCY) is incubated with GGPP, a variediene:fusicoccadiene product ratio of 1:1.1 is observed; when incubated with DMAPP and IPP, the variediene:fusicoccadiene ratio is 1:5.4 (Fig. 2C). Surprisingly, the substantial enrichment of fusicoccadiene indicates that GGPP generated by the EvVS prenyltransferase preferentially transits to the non-native PaFSCY cyclase domain rather than being released to bulk solution. Thus, the three-dimensional (3D) structure of EvVS must be able to accommodate transient association of PaFSCY to enable preferential GGPP transfer. Our recent studies of PaFS indicate that transient cyclase-prenyltransferase association supporting GGPP channeling occurs at the side of the prenyltransferase oligomer31,32,35. Accordingly, we hypothesize that PaFSCY similarly associates with the side of the EvVS prenyltransferase oligomer for preferential GGPP transfer.

Cryo-EM structure determination

To ascertain the mode of prenyltranferase-cyclase association in EvVS, we determined the cryo-EM structure of the full-length enzyme. Protein samples were incubated with Mg2+ and the unreactive substrate analogue geranylgeranyl thiolodiphosphate (GGSPP). Following cryo-EM data collection, initial two-dimensional (2D) classification revealed several orientations of a well-defined hexameric assembly with all catalytic domains visualized (Fig. S3). Initial particle sorting and ab initio 3D reconstructions confirmed that cyclase domains associate with the top and bottom of the hexameric prenyltransferase core (Fig. S4). Heterogeneous refinement was used for initial sorting of 637,378 particles. While the majority of particles (398,696; 63%) exhibit densities corresponding to all six cyclase domains, 146,937 particles (23%) are missing density for one cyclase domain and 17,383 particles (3%) are missing densities for two cyclase domains. Weak or absent densities for one or two associated cyclase domains suggest that these domains are randomly splayed-out and hence average out in 3D reconstructions. Of note, particles with two missing cyclase densities align to only 9.9 Å resolution, likely due to the relatively small number of particles.

Overall, cyclase-prenyltransferase association appears to be much more stable in full-length EvVS compared with all other full-length bifunctional terpene synthases previously studied by cryo-EM31,32,33,34. Even so, the observation of EvVS particles containing only 4 or 5 ordered cyclase domains suggests that prenyltransferase-associated cyclase positions are in dynamic equilibrium with splayed-out cyclase positions.

For 3D refinement, all available particles were used first to determine the structure of the hexameric prenyltransferase core with densities for cyclase domains subjected to particle subtraction. Density is visible beginning at L426, and ends at G710 (a portion of the C-terminal helix (P712-V725) was masked out during particle subtraction). After local refinement, prenyltransferase particles aligned to 2.77 Å resolution (Fig. 3A, B). Only one polypeptide loop (E620-D630) lacks density and is judged to be disordered, and therefore not modeled, in each monomer. The hexameric prenyltransferase can be described as a trimer of dimers and aligns closely with the structures of hexameric prenyltransferases from other bifunctional fungal diterpene synthases (Fig. 3C)29,30,34,35. The complete workflow is summarized in Fig. S5 with relevant statistics recorded in Table S1. Data coverage and Gold-Standard Fourier Shell Correlation plots are presented in Fig. S6.

A The overall resolution of the EvVS hexamer is 2.77 Å; interior regions have higher resolutions and external loops have lower resolutions. B The model of the EvVS prenyltransferase is fit into the map with C3 symmetry. C The EvVS prenyltransferase hexamer as well as a single dimer overlay closely with structures of other fungal prenyltransferases determined by X-ray crystallography (left; PDB 5ERO and 6V0K, respectively) and cryo-EM (right; PDB 8EAX and 8V0F, respectively). Copalyl diphosphate synthase from Penicillium verruculosum, PvCPS; copalyl diphosphate synthase from Penicillium fellutanum, PfCPS.

Structures of hexameric prenyltransferase-cyclase assemblies containing six and five cyclases were then determined. Using the particle stacks identified above, 3D classification was used to find the particles in each subset aligning with the highest resolution. The six-cyclase structure is based on 60,587 particles that aligned to 3.52 Å resolution. Phenix confirmed the presence of C3 symmetry and the overall resolution after symmetry-averaging improved to 3.18 Å (Fig. 4A). While density for the prenyltransferase core is sufficiently strong to define orientations for most side chains, densities for cyclase domains are sufficient only to define α-helices. Even so, the orientation of each cyclase domain is unambiguously determined, allowing for the construction of a model of the entire assembly using cyclase coordinates generated with AlphaFold338 (Fig. 4B). In similar fashion, the five-cyclase structure is based on 51,215 particles that aligned to 3.59 Å resolution (Fig. 4C). Here, too, density for the prenyltransferase core is sufficiently strong to define orientations for most side chains, whereas densities for cyclase domains are sufficient only to define α-helices and the orientation of each domain (Fig. 4D). The complete workflow is summarized in Fig. S5, and relevant statistics are recorded in Table S1 and Fig. S6.

The 66-residue flexible linker connecting the prenyltransferase and cyclase domains of EvVS is not visible in cryo-EM maps, but the C-terminus of the cyclase and the N-terminus of the prenyltransferase are sufficiently well defined in the six-cyclase structure to suggest how they are most likely linked together (Fig. 5A). The maximum length of an extended 66-residue linker would be approximately 230 Å; two different prenyltransferase domain N-termini are within this distance from the C-terminus of each cyclase. One of these connections is more direct and the other would require the linker to partially wrap around the cyclase or the interior of the assembly. Accordingly, the more direct connection would seem to be more likely, which would yield a domain-swapped architecture (Fig. 5B).

A The more direct prenyltransferase-cyclase linker connection yields a domain-swapped architecture; each connected domain pair appears as a single color (corresponding linkers are disordered and hence not shown). B Support for domain-swapping derives from the locations of domain termini: the C-terminus of the blue cyclase is gray, the N-terminus of prenyltransferase 1 (PT 1, blue) is dark blue, and the N-terminus of prenyltransferase 2 (PT 2, red) is dark red. The blue dotted line connects the cyclase with prenyltransferase 1, which is a more direct connection. The red dotted line connects the cyclase with prenyltransferase 2, which is a less direct connection that would require the linker to partially wrap around the assembly. The chains shown in (B) are rotated approximately 60° clockwise around a vertical axis from their position in (A) so that both N-termini are visible.

Notably, cyclase resolution drops with increasing distance from the core in both the six-cyclase and five-cyclase structures. However, a single helix of the cyclase always appears with well-defined density as it interacts with the prenyltransferase. Moreover, the densities of more distant helices are distorted, suggesting that the cyclase domain wobbles back and forth with the prenyltransferase-associated helix serving as a pivot point. The application of 3D conformational variability analysis reveals that cyclase wobbling is captured in the dataset (Supplementary movie 1 and Supplementary movie 2 show perpendicular views).

To resolve these conformations and to determine the structure of the cyclase domain with the highest possible resolution, the entire set of 491,079 particles was subjected to symmetry expansion and particle subtraction to remove all cyclases except the one defined by the strongest density in each particle. After local refinement, we used 3D classification with a focus mask over the cyclase domain. Particle subtraction and refinement worked well only if the entire prenyltransferase core was retained along with the single cyclase domain, which yielded a particle of sufficient size to achieve effective alignment. Ultimately, three classes emerged at 3.00 Å, 3.08 Å, and 2.98 Å overall resolution (Maps 1, 2, and 3, respectively), showing the cyclase in slightly different orientations that illustrate the extent of cyclase wobble (Fig. 6). The complete workflow is summarized in Fig. S5; relevant statistics are found in Table S1 and Fig. S7.

A Three different cyclases conformations are illustrated in Maps 1, 2, and 3, the average of which yields the distorted densities observed in the six- and five-cyclase structures. These maps illustrate the extent of cyclase wobble. B Representative cyclase domain map with distorted density. C Cyclase domain map showing substantial resolution improvement resulting from symmetry-expansion and particle subtraction.

In the best map of the EvVS cyclase domain (Map 3, 2.98 Å resolution), the model begins at residue D9 and ends with Q343. While several loops are disordered and not modeled for the cyclase domains in the six- and five-cyclase structures, overall densities in these three models are sufficiently improved such that only one disordered loop is not modeled (V122–R146). This segment contains two helix termini and a loop connecting them adjacent to the active site (Fig. 7A). The overall structure overlays nearly perfectly with the AlphaFold3-predicted structure except for the disordered loop (AlphaFold3 designates this loop as a segment of low prediction confidence (Fig. S8)). The cryo-EM structure of the cyclase domain also displays strong agreement with the structure of GJ1012 synthase from Fusarium graminearum (FgGS), a fungal cyclase exhibiting the highest sequence identity with EvVS (40%) for which a crystal structure is available39.

A Overlay of the cryo-EM structure of the cyclase domain from Map 3 (magenta), the AlphaFold3 structure prediction (purple), and the crystal structure of FgGS (yellow). B Close-up view of the active site of the EvVS cyclase domain. Density for the diphosphate group is shown by a light blue surface for cyclase Map 3 (EMD-47457, contour level 0.090). C The inorganic pyrophosphate anion in the active site of FgGS (PDB 6VYD) binds similarly to the diphosphate group in the EvVS cyclase active site shown in (B). Also bound in the FgGS active site is the benzyl triethylammonium cation (BTAC).

Additional densities are observed in the active sites of all three cyclase conformations, located between conserved metal binding motifs characteristic of terpene cyclases: the DXXXD/E motif (D120 and E124) and the NXXXSXXXE motif (N250, S254, and E258). The strongest density is observed in Map 3 (Fig. 7B, Fig. S9) and is located in a position similar to that of the Mg2+3-PPi cluster in the active site of FgGS (Fig. 7C). However, the density in Map 3 is not sufficient to confidently model Mg2+ ions, so these are omitted from the final model, leaving just the diphosphate group (Fig. 7B, Fig. S9). It is notable, however, that the structures of Mg2+3-diphosphate clusters are essentially identical among all class I terpene cyclases10. Maps 1-3 contain uninterpretable patches of density extending into the hydrophobic active site cavity that may correspond to the 20-carbon isoprenoid tail of GGSPP. However, if GGSPP were hydrolyzed during the time course of sample preparation, these patches of density would be spurious.

The structure of the cyclase-prenyltransferase interface is visualized at approximately 3.8 Å resolution, which is sufficiently high to model side chains involved in domain-domain interactions. Single α-helices from each domain largely mediate these interactions – P712-V725 in the prenyltransferase and R129-S150 in the cyclase (Fig. S10). The total buried surface area at the interface is 1228 Å2, consistent with a stable protein-protein interaction. No obvious hydrogen-bonding interactions are evident to confer stability; instead, helix-helix association appears to be driven mainly by “knobs-into-holes” packing40 and the hydrophobic effect. The three most prominent residues on the prenyltransferase that form the binding surface, W714, L718, and H721 (Fig. S10), are only loosely conserved in other bifunctional terpene synthases (Fig. S11), so it is not clear if a similar, stable domain-domain interaction can form in other systems.

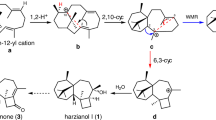

As observed in all terpene cyclases, active site residues are predominantly hydrophobic. The proposed cyclization mechanism of EvVS (Fig. 8A)37 requires an active site base to quench the final carbocation intermediate by deprotonation, and the PPi co-product likely serves this function. A plausible model of the precatalytic enzyme-substrate complex shows that GGPP can bind in the active site with a conformation supporting the two ring closure reactions in the first steps of the cyclization cascade (Fig. 8B). A computational study of variediene formation by Hong and Tantillo shows that after substrate ionization, the C1-C11 and C10-C14 coupling reactions are likely concerted41. The conformation of GGPP (Fig. 8B) corresponds to that calculated by these investigators.

A Mechanism of geranylgeranyl diphosphate (GGPP) cyclization proposed by Abe and colleagues37. Isoprenoid methyl groups are color-coded to better follow the mechanistic sequence. B Model of the precatalytic binding conformation of GGPP in the active site of the EvVS cyclase (atomic coordinates from Map 3) consistent with the ring closure reactions outlined in (A). The atomic coordinates calculated for GGPP by Hong and Tantillo41 were manually docked in the EvVS cyclase active site so as to avoid steric clashes while positioning the diphosphate group in the same location as that observed for the diphosphate group in Map 3 (Fig. 7B). The active site cavity was visualized using the GetCleft tool from the NGRSuite plugin in PyMOL to guide docking, but the surface contour is not shown here for clarity.

To complement the EvVS structure, we identified sequences for other representative class I bifunctional fungal terpene synthases and performed systematic structural predictions using AlphaFold3 (sequences listed in Supporting Information; also see Table S2 and Figs. S12–S22). Each AlphaFold3 prediction yields atomic coordinates for five different models with a predicted template modeling (pTM) score and interface predicted template modeling (ipTM) score based on discrepancies in the five models. A high-confidence prediction generates five very similar models and yields a high ipTM score. We performed an AlphaFold3 prediction for each sequence five times, with six copies of the sequence entered to allow hexamer formation, to generate an average ipTM score from five distinct predictive trials. Scores ranged between 0.69 and 0.43; sequences with high scores generally yield five predictions very similar to each other, whereas sequences with low scores yield multiple predicted domain-domain binding modes. Serendipitously, the two systems we have studied experimentally represent the two limiting cases. EvVS yields the highest ipTM score of 0.69, consistent with the stable interdomain interaction observed in the cryo-EM structure. PaFS yields the lowest ipTM score of 0.43 (tied with three other enzymes), consistent with weaker and transient domain-domain interactions as observed in cryo-EM studies31,32. Thus, AlphaFold3 appears to have useful predictive power in determining whether a bifunctional terpene synthase features stable prenyltransferase-cyclase interactions or not.

Side-on interactions of the cyclase domain with the hexameric prenyltransferase core are very rarely predicted by AlphaFold3: only nine examples are observed in 110 total predictions. Three examples are observed for PaFS, the only system with experimental evidence for a side-on interaction31,32; two examples are observed with deoxyconidiogenol synthase, and one example is observed with talarodiene synthase. In these predicted structures, all cyclases interact with the sides of the prenyltransferase core. The remaining three examples are observed with ophiobolin F synthase, where some but not all cyclase domains are directly or diagonally associated with the sides of the prenyltransferase core. The remaining 101 predictions show cyclases interacting with the top and bottom of the respective hexameric prenyltransferase cores, in a manner similar to that observed in the cryo-EM structure of EvVS. A global alignment of the 22 sequences reveals that while the prenyltransferase domain drives most of the observed sequence identity, systems with high ipTM scores do not exhibit higher identities with each other (Figs. S23 and S24). No clear relationship between sequence identity and predicted interdomain interaction mode is discernible, nor is any relationship evident with the size of the terpene product generated – bifunctional diterpene synthases, sesterterpene synthases, and the triterpene synthase MpMS are distributed randomly in Table S2, where enzymes are ordered by ipTM score. This analysis highlights the emerging power of AlphaFold3 not only in predicting protein tertiary structure, but also in predicting hidden trends in quaternary structure – analysis of sequence identities alone would not have identified other enzymes predicted to adopt EvVS-like interdomain interactions.

Since the discovery of PaFS in 2007 by Toyomasu and colleagues24, the explosion of fungal genomic information has led to the identification and functional assignment of a steadily growing number of bifunctional terpene synthases (Table S2). In 2021, a landmark study cataloged 227 such genes, 74 of which were heterologously expressed to yield 34 enzymes with measurable catalytic activity26. The remaining task is to connect the wealth of sequence and functional information to 3D protein structures. To expand upon this study, we utilized PaFS as a query sequence with the Enzyme Function Initiative (EFI)-Enzyme Similarity Tool42 to assemble a sequence similarity network containing a total of 1016 sequences, with 60 clusters identified containing 3 or more sequences (Fig. 9; all sequence sources are recorded in the associated file Supplementary Data 1). The great majority of these sequences derive from fungi, as expected. Intriguingly, however, 21 sequences derive from the bdelloid rotifer Adineta steineri, a freshwater marine animal. Each rotifer sequence contains conserved metal-binding motifs in the prenyltransferase and cyclase domains as compared with the bifunctional paradigms EvVS and PaFS (Figs. S25–S28).

The distribution of known (functionally identified) bifunctional terpene synthases in the known space of similar sequences was investigated using a sequence similarity network. The 22 sequences used for multiple sequence alignment and AlphaFold3 prediction in this study are shown in red. Copalyl diphosphate synthase from Penicillium verruculosum (PvCPS), a type II bifunctional terpene synthase with αβγ domain architecture, is shown in purple, in a cluster of hitherto-unknown bifunctional terpene synthases with similar domain architecture. All sequences in the network derive from fungi with the exception of the green cluster, which contains 21 sequences from Adineta steineri, a species of bdelloid rotifer. Based on AlphaFold3 prediction of their domain architecture and identification of metal-binding motifs shared with variediene synthase (EvVS) and fusicoccadiene synthase (PaFS) (Figs. S25–S28), these sequences appear to be bifunctional terpene synthases.

Discussion

The cryo-EM structure of EvVS reveals a prenyltransferase hexamer with all six cyclase domains visible and associated at the top and bottom of the hexameric assembly. Catalytic domains are positioned in the oligomer such that domain-swapped architecture is most likely. Given that the prenyltransferase-cyclase active site separation is 30 Å (Fig. S10), it is surprising that intramolecular GGPP channeling is not observed; instead, intermolecular GGPP channeling is observed only with the non-native cyclase, PaFSCY.

Since all six native cyclase domains are locked in place at the top and bottom of the EvVS oligomer, we speculate that PaFSCY associates with the side of the oligomer to enable preferential GGPP transfer (Fig. S29). Such side-on association of the PaFS cyclase domain has been observed in native full-length PaFS31,32, in which GGPP channeling is observed35,36, and channeling efficiency increases if the cyclase domains are locked in place on the sides of the prenyltransferase oligomer by splicing out the flexible linker connecting the catalytic domains35. In view of these results, we suggest that side-on association of the PaFS cyclase domain with EvVS similarly facilitates GGPP channeling, in this case to a non-native cyclase.

It is remarkable that more than 1000 bifunctional terpene synthases are identified through the use of the EFI-Enzyme Similarity Tool (Fig. 9), so bifunctional prenyltransferase-cyclase enzymes represent an important class of fungal enzymes. Intriguingly, however, 21 sequences are identified in a marine animal, the bdelloid rotifer A. steineri. These sequences represent the first bifunctional terpene synthase genes identified in an animal species and they complement the discovery of single-function terpene cyclases in corals and sponges, which are also marine animals16,17,18. Interestingly, many other genes deriving from fungi, bacteria, and plants have been identified in bdelloid rotifers, so it is thought that horizontal gene transfer figures prominently in rotifer evolution43. Thus, structure-function relationships established for EvVS as well as PaFS will inform our understanding of carbon management in the large, growing family of bifunctional terpene synthases in fungi as well as marine animals. These results promise to guide protein engineering approaches aimed at optimizing biosynthetic efficiency in these systems.

Methods

Protein expression and purification

All proteins utilized herein were prepared in similar fashion. Full sequences for the EvVS (Uniprot identifier A0A0P0ZD79) and EvVSCY construct are listed in the Supporting Information. For each protein, BL21-DE3 competent cells (New England Biolabs) were transformed with a plasmid containing the target gene in a pet28A vector fused to an N-terminal His6 tag (twenty additional residues added) acquired from Genscript. Following overnight incubation at 37 °C on agar, a single colony was used to inoculate a 300-mL culture supplemented with 50 µg/mL kanamycin. The culture was then grown overnight at 37 °C with shaking at 150 RPM. Starter culture (50 mL) was then transferred into each of six 2.5-L flasks, each of which contained 1 L Luria-Bertani medium and 50 µg/mL kanamycin. When the OD600 reached 1.0, flasks were cooled on ice for 45 min prior to induction of protein expression by the addition of 0.5 mM isopropyl-β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside. Cultures were then shaken at 16 °C for 18 h at 150 RPM.

The next morning, cells were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in lysis buffer [40 mM sodium phosphate monobasic, 60 mM potassium phosphate dibasic (pH 7.5), 200 mM NaCl, 1 mM tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP), and 10% glycerol]. The suspension was stirred for 2 h at 4 °C. Cell lysis was achieved using a Qsonica sonicator (1 s pulse on and 3 s off at 30% power for 40 min) and the lysate was clarified by centrifugation (19,000 RPM for 35 min). Clarified lysate was applied to a pre-equilibrated Ni-NTA column (Cytiva) and washed with five column volumes of lysis buffer. Protein was then eluted using lysis buffer supplemented with 300 mM imidazole. Fractions containing the target protein were pooled and immediately loaded onto a size-exclusion column (GE Healthcare, Superdex 200 pg) equilibrated with sizing buffer [50 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES) (pH 7.5), 200 mM NaCl, 2 mM TCEP, and 10% glycerol], skipping any concentration or dialysis steps. Fractions containing the target protein were combined and diluted to a total volume of 100 mL with zero-salt sizing buffer (lysis buffer without NaCl). This solution was then applied to an anion-exchange column (Cytiva), washed with five column volumes of zero-salt buffer, and eluted using a 100-mL gradient between zero-salt and high-salt sizing buffer (sizing buffer containing 1 M NaCl). Protein fractions were combined and the glycerol concentration was adjusted to 30% by addition of a solution of 75% glycerol in water (the amount of 75% glycerol solution spiked in was equal to one quarter the volume of the pooled fractions). The solution was then concentrated using an Amicon centrifugal filter (molecular weight cutoff 30,000 kD) until the protein concentration reached approximately 120 µM. The protein was flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C.

Steady-state kinetics

Steady-state kinetic parameters were determined using the EnzChekTM Pyrophosphate Assay Kit (ThermoFisher Scientific). Briefly, assays were performed on a 100-µL scale with the protein concentration at 0.5 µM in lysis buffer. Purine nucleoside phosphorylase, inorganic pyrophosphatase, MgCl2, and 2-amino-6-mercapto-7-methylpurine ribonucleoside were added to final concentrations of 0.1 U, 0.003 U, 2.5 mM, and 200 µM, respectively. Each reaction was individually assembled in a cuvette to a final volume of 90 µL. The desired concentration of GGPP (ranging from 1.0 to 50 µM) was added from the 0.5 mM working dilution (a 1:10 dilution in lysis buffer of the 5 mM stock prepared by reconstitution of solid in 70% methanol, 30% 10 mM NH4HCO3 in water). Addition of 10 µL of enzyme from a 5 µM stock initiated the reaction and the cuvette was immediately placed into a Cary 60 UV/vis spectrometer. The absorbance at 360 nm was measured every 2 s for 2 min. In total, three identical trials for each substrate concentration were performed for each enzyme.

The initial velocity of each reaction was determined by fitting the linear portion of each trace (60–100 s) using linear regression in Prism software. Slopes were converted into rates (rise in AU/s to nM phosphate/s) using a conversion factor (0.0258) determined in a separate control experiment wherein pyrophosphate was added directly to the coupled-enzyme assay. Plotting of the rates over GGPP concentration allowed for analysis in Prism software. Data were fit using the Michaelis-Menten equation.

Substrate competition assay

In a typical substrate competition experiment, both proteins were diluted to 3.0 µM in freshly-prepared lysis buffer with a total volume of 200 µL in a 2-mL glass vial with no insert. MgCl2 was added to a final concentration of 3 mM. To initiate the reaction, 20 µL of substrate was added – either 20 µL GGPP from a 5 mM stock, or 10 µL of DMAPP from a 10 mM stock and 10 µL of IPP from a 30 mM stock. All substrates were resuspended in a mixture of 70% methanol, 30% 10 mM NH4HCO3 in water, and adding substrate in the specified amounts from the specified stock concentrations ensured that each sample contained the same final volume of methanol regardless of which substrates were added. The capped vial was incubated for 4 h on the benchtop at room temperature. Ethyl acetate (200 µL) was then added and the mixture was vortexed for 5 s. The entire mixture was then transferred to a 1.7 mL Eppendorf tube and centrifuged at 6000 RPM for 5 s. The organic layer (200 µL) was then removed using a micro-pipette and transferred to a fresh GC vial with an insert.

Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) was used for the identification and quantification of diterpene cyclization products. Samples were run on an Agilent 8890 GC system coupled to a 5977 C GC/MSD mass spectrometer with a J&W HP-5MS GC column capillary column in EI+ mode. The following temperature program was used: hold at 60 °C for 2 min, ramp to 320 °C at 10 °C/min, and hold at 320 °C for 2 min. A solvent delay of 4 min was used. Variediene eluted at 10.5 min, fusicoccadiene eluted at 10.7 min, spatadiene at 10.9 min, and cyclooctatenol at 11.9 min.

Cryo-EM structure determination

Prior to grid preparation, EvVS was dialyzed into cryo-EM buffer [25 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 100 mM NaCl, 60 mM sodium phosphate monobasic, and 140 mM potassium phosphate dibasic] at 4 °C for 1 h. MgCl2, geranylgeranyl thiodiphosphate (GGSPP), and 3-([3-cholamidopropyl]dimethylammonio)-2-hydroxy-1-propanesulfonate (CHAPSO) protein detergent were then added to final concentrations of 2.5 mM, 20 mM, and 8 mM, respectively. The final protein concentration was ~100 µM. The sample was filtered by centrifugation in a 0.22-µM filtration unit (Millipore). R1.2/1.3 200-mesh copper grids (Quantifoil) were glow-discharged for 2 min (easiGlow, Pelco). A 3 µL protein sample was applied to the grid at 4 °C, the grid was blotted for 3 s with blot force of 3, and another 3 µL of protein sample was applied and blotted (multiple protein application and blotting steps can increase particle density dramatically44). The grid was then flash-frozen in liquid ethane using a Mark IV Vitrobot (ThermoFisher Scientific). Grids were prepared at 100% humidity. Frozen grids were clipped and transferred to a Titan Krios G3i cryogenic transmission electron microscope (Thermo Fischer Scientific) operating at 300 keV at Brookhaven National Laboratory. Images were recorded with a K3 Summit electron detector at 81,000 magnification (1.07 Å/pixel) with a defocus of −1.0 to −3.0 µM. The beam intensity was 15 e-/px/s (13 e-/Å2/s) and the exposure time was 3.84 s. The total dose was 50 e-/Å2/s. 40 frames were taken. A total of 8727 movies was collected from a single grid.

The EvVS dataset was processed using cryoSPARC (version 4.4.1)45 and the workflows of all 3D reconstructions are summarized in Fig. S5. After motion and CTF correction, 106 exposures were rejected during curation to yield 8621 micrographs. Topaz Extract (box size of 384 Å) was used to generate a pool of 844,262 particles that were subjected to 2D classification (150 classes). Selection of all protein-resembling classes yielded a pool of 421,245 particles. After ab initio 3D reconstruction and heterogeneous refinement, the best model (115,628 particles) was used with 983 of the micrographs to train a Topaz model. The model was then used for re-extraction of the entire dataset, yielding a pool of 1,228,533 particles. 2D classification of these particles allowed for selection of 807,870 particles for further processing.

With these particles, we generated ab initio 3D reconstructions of four different classes and subjected them to four rounds of heterogeneous refinement. After the refinement, one class (83,058 particles) contained only junk. The remaining 724,812 were reference motion corrected. Heterogeneous refinement was used to exclude an additional 87,134 junk particles and to sort the remaining 637,678 particles into three stacks: a stack with all six cyclases present (398,696 particles), with only five cyclases present (164,320 particles), and with only four cyclases present (17,383). The four-cyclase class was subjected to homogeneous refinement and then non-uniform refinement to generate the map shown in Fig. S4.

To obtain the structure of the hexameric core, the five-cyclase and six-cyclase particle stacks were combined by homogeneous refinement (491,079 particles) and then subjected to non-uniform refinement (wherein C3 symmetry was applied). The cyclase domains were subjected to particle subtraction and the resulting map was locally refined. The map shown in Fig. 3 was polished with DeepEMhancer46 and has an overall resolution of 2.77 Å.

To determine the six-cyclase structure, the stack of 398,696 particles was subjected to 3D classification with a focus mask covering all six cyclase domains. The best class that emerged had 60,587 particles and a resolution of 3.63 Å after homogeneous refinement. Non-uniform refinement was used to apply C3 symmetry and the resolution improved to 3.18 Å. The map of the six-cyclase structure shown in Fig. 4A was polished with DeepEMhancer46. To determine the five-cyclase structure, the stack of 164,320 particles was subjected to 3D classification with a focus mask covering five cyclase domains. The best class had 51,215 particles and an overall resolution of 3.67 Å. After non-uniform refinement, the resolution improved to 3.59 Å. The map of the five-cyclase structure shown in Fig. 4C was polished with DeepEMhancer46. 3D variability analysis on the same pool of 398,696 particles produced Supplementary movie 1 and Supplementary movie 2, which show perpendicular views. UCSF ChimeraX47 was used to generate movie (.mov) files showing the transition across the set of 20 maps from different orientations. The.mov files were converted to GIFs using a freely available online tool (ezgif.com).

To determine the highest-resolution structure of the cyclase domain, the combined pool of five- and six-cyclase particles with applied C3 symmetry outlined previously was symmetry-expanded and locally refined to give a pool of 1,473,237 particles. Five cyclases were subtracted, leaving the entire hexameric prenyltransferase core and a single cyclase domain. 3D classification into five classes with a focus mask over the cyclase domain produced two lower-resolution classes and a series of three classes with 298,050, 294,185, and 289,027 particles with 3.0, 3.08, and 2.98 Å resolution overall (after local refinement) revealing clear density for the cyclase domain in three slightly different positions relative to the core (designated Map 1, Map 2, and Map 3, respectively). The maps shown in Fig. 6 were polished with DeepEMhancer46.

Model building and refinement

Atomic coordinates generated by AlphaFold3 were used as starting points for all six models38. UCSF ChimeraX 1.3 was initially used to dock the models into the maps47. Iterative rounds of refinement and model building were then performed with Phenix Real Space Refine48 and WinCoot49. Model quality was assessed with MolProbity50.

The final model of the EvVS prenyltransferase hexamer (PDB 9E2H, EMD-47452) contains 6 polypeptide chains and no ligands or water molecules. Chain A contains residues 426-710. Chain B contains residues 425-710. Chain C contains residues 425-709. Chain D contains residues 425-710. Chain E contains residues 426-709. Chain F contains residues 425-710. One loop is disordered and not modeled due to insufficient density, comprising residues 620-630, in all six chains.

The final model of EvVS with six cyclases (PDB 9E2I, EMD-47453) contains 6 polypeptide chains and no ligands or water molecules. Chain A contains residues 28-724. Chain B contains residues 24-724. Chain C contains residues 27-724. Chain D contains residues 25-724. Chain E contains residues 27-724. Chain F contains residues 24-725. Some residues are not modeled due to insufficient cryo-EM density. In chain A, the unmodeled residues are 35-42, 51-57, 122-144, 189-195, 317-320, 361-425, and 620-630. In chain B, the unmodeled residues are 36-41, 123-144, 190-203, and 362-425. In chain C, the unmodeled residues are 36-42, 51-55, 122-139, 186-204, 363-425, and 619-631. In chain D, the unmodeled residues are 37-39, 51-52, 122-144, 190-196, 362-426, and 620-630. In chain E, the unmodeled residues are 36-40, 51-52, 122-144, 189-201, and 361-426. In chain F, the unmodeled residues are 37-39, 51-52, 122-144, 190-196, and 363-425.

The final model of EvVS with five cyclases (PDB 9E2J, EMD-47454) contains 6 polypeptide chains and no ligands or water molecules. Chain A contains residues 27-725. Chain B contains residues 27-725. Chain C contains residues 28-724. Chain D contains residues 27-724. Chain E contains residues 28-724. Chain F contains residues 426-724. Some residues are not modeled due to insufficient cryo-EM density. In chain A, the unmodeled residues are 124-142, 362-426, and 620-630. In chain B, the unmodeled residues are 36-41, 52-53, 57-61, 83-88, 125-146, 189-201, 277-289, 358-425, and 620-630. In chain C, the unmodeled residues are 36-41, 51-55, 125-144, 189-194, 362-425, and 619-630. In chain D, the unmodeled residues are 38-42, 125-143, 190-196, 318-320, 365-425, and 620-627. In chain E, the unmodeled residues are 37-40, 125-146, 190-208, 240-244, 266-270, 275-284, 310-319, 359-425, and 619-628. In chain F, the unmodeled residues are 620-628.

The final model of EvVS with one cyclase designated Map 1 (PDB 9E2K, EMD-47455) contains 6 polypeptide chains, one ligand chain, and no water molecules. Chain A contains residues 426-725. Chain B contains residues 26-698. Chain C contains residues 425-709. Chain D contains residues 425-701. Chain E contains residues 426-709. Chain F contains residues 425-710. Chain G contains the pyrophosphate ion ligand (POP; 1). Some residues are not modeled due to insufficient cryo-EM density. In chain A, the unmodeled residues are 620-630. In chain B, the unmodeled residues are 123-144, 361-424, 452-459, and 620-630. In chain C, the unmodeled residues are 620-630. In chain D, the unmodeled residues are 452-457 and 620-630. In chain E, the unmodeled residues are 620-630. In chain F, the unmodeled residues are 620-630.

The final model of EvVS with one cyclase designated Map 2 (PDB 9E2L, EMD-47456) contains 6 polypeptide chains, one ligand chain, and no water molecules. Chain A contains residues 426-723. Chain B contains residues 26-698. Chain C contains residues 426-709. Chain D contains residues 427-701. Chain E contains residues 427-709. Chain F contains residues 427-709. Chain G contains the pyrophosphate ion ligand (POP; 1). Some residues are not modeled due to insufficient cryo-EM density. In chain A, the unmodeled residues are 620-630. In chain B, the unmodeled residues are 123-145, 361-425, 452-459, and 620-630. In chain C, the unmodeled residues are 620-630. In chain D, the unmodeled residues are 452-457 and 620-630. In chain E, the unmodeled residues are 620-630. In chain F, the unmodeled residues are 620-630.

The final model of EvVS with one cyclase designated Map 3 (PDB 9E2M, EMD-47457) contains 6 polypeptide chains, one ligand chain, and no water molecules. Chain A contains residues 426-723. Chain B contains residues 26-698. Chain C contains residues 426-709. Chain D contains residues 427-701. Chain E contains residues 427-709. Chain F contains residues 27-709. Chain G contains the pyrophosphate ion ligand (POP; 1). Some residues are not modeled due to insufficient cryo-EM density. In chain A, the unmodeled residues are 620-630. In chain B, the unmodeled residues are 124-148, 361-425, 452-459, and 620-630. In chain C, the unmodeled residues are 620-630. In chain D, the unmodeled residues are 452-457 and 620-630. In chain E, the unmodeled residues are 620-630. In chain F, the unmodeled residues are 620-630.

Sequence similarity network

A sequence similarity network was constructed using the EFI Enzyme Similarity Tool (EFI-EST)42. PaFS (UniProt: A2PZA5) was used as the query sequence and 10,000 sequences were requested. Many of the collected sequences were single-domain prenyltransferases or cyclases, so the sequence set was restricted by length: only sequences longer than 600 residues and shorter than 1200 residues were used. The alignment score used to form the network was 225. Several clusters and single nodes containing other types of proteins (such as carcinoma antigens, pre-mRNA splicing factors, and amidohydrolases) were removed. The final network contains 1016 sequences and 60 clusters of at least three sequences. The network was visualized using Cytoscape 3.10.351.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Atomic coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB, www.rcsb.org) and cryo-EM maps have been deposited in the Electron Microscopy Data Bank (EMD) with accession codes as follows: EvVS prenyltransferase hexamer, PDB 9E2H, EMD-47452; EvVS hexamer with six cyclase domains bound, PDB 9E2I, EMD-47453; EvVS hexamer with five cyclase domains bound, PDB 9E2J, EMD-47454; EvVS hexamer with one cyclase domain bound: Map 1, PDB 9E2K, EMD-47455; Map 2, PDB 9E2L, EMD-47456; Map 3, PDB 9E2M, EMD-47457. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Ninkuu, V. et al. Biochemistry of terpenes and recent advances in plant protection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 5710–5732 (2021).

Divekar, P. A. et al. Plant secondary metabolites as defense tools against herbivores for sustainable crop protection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 2690–2714 (2022).

Boncan, D. A. T. et al. Terpenes and terpenoids in plants: interactions with environment and insects. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 7382–7401 (2020).

Cox-Georgian, D., Ramadoss, N., Dona, C. & Basu, C. Theraputic and medicinal uses of terpenes. In Medicinal Plants: From Farm to Pharmacy (eds Joshee, N., Dhekney, S. A. & Parajuli, P.) (Springer Nature Switzerland AG, 2019).

Stepanyuk, A. & Kirschning, A. Synthetic terpenoids in the world of fragrances: Iso E Super® is the showcase. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 15, 2590–2602 (2019).

Mewalal, R. et al. Plant-derived terpenes: a feedstock for specialty biofuels. Trends Biotechnol. 35, 227–240 (2017).

Christianson, D. W. Roots of biosynthetic diversity. Science 316, 60–61 (2007).

Wu, Z., Wouters, J. & Poulter, C. D. Isopentenyl diphosphate isomerase. Mechanism-based inhibition by diene analogues of isopentenyl diphosphate and dimethylallyl diphosphate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 17433–17438 (2005).

Kellogg, B. A. & Poulter, C. D. Chain elongation in the isoprenoid biosynthetic pathway. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 1, 570–578 (1997).

Aaron, J. A. & Christianson, D. W. Trinuclear metal clusters in catalysis by terpenoid synthases. Pure Appl. Chem. 82, 1585–1597 (2010).

Christianson, D. W. Structural and chemical biology of terpenoid cyclases. Chem. Rev. 117, 11570–11648 (2017).

Christianson, D. W. Unearthing the roots of the terpenome. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 12, 141–150 (2008).

Davis, E. M. & Croteau, R. Cyclization enzymes in the biosynthesis of monoterpenes, sesquiterpenes, and diterpenes. In Biosynthesis: Aromatic polyketides, isoprenoids, alkaloids (eds Leeper, F. J. & Vederas, J. C.) (Springer-Verlag, 2000).

Austin, M. B., O’Maille, P. E. & Noel, J. P. Evolving biosynthetic tangos negotiate mechanistic landscapes. Nat. Chem. Biol. 4, 217–222 (2008).

Miller, D. J. & Allemann, R. K. Sesquiterpene synthases: passive catalysts or active players?. Nat. Prod. Rep. 29, 60–71 (2012).

Scesa, P. D., Lin, Z. & Schmidt, E. W. Ancient defensive terpene biosynthetic gene clusters in the soft corals. Nat. Chem. Biol. 18, 659–653 (2022).

Burkhardt, I., de Rond, T., Chen, P. Y.-T. & Moore, B. S. Ancient plant-like terpene biosynthesis in corals. Nat. Chem. Biol. 18, 664–669 (2022).

Wilson, K. et al. Terpene biosynthesis in marine sponge animals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2220934120 (2023).

Park, J., Zielinski, M., Magder, A., Tsantrizos, Y. S. & Berghuis, A. M. Human farnesyl pyrophosphate synthase is allosterically inhibited by its own product. Nat. Commun. 8, 14132 (2017).

Kainou, T., Kawamura, K., Tanaka, K., Matsuda, H. & Kawamukai, M. Identification of the GGPS1 genes encoding geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthases from mouse and human. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1437, 333–340 (1999).

Muehlebach, M. E. & Holstein, S. A. Geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthase: role in human health, disease and potential therapeutic target. Clin. Transl. Med. 13, e1167 (2023).

Trepa, M., Sułkowska-Ziaja, K., Kała, K. & Muszyńska, B. Therapeutic potential of fungal terpenes and terpenoids: application in skin diseases. Molecules 29, 1183 (2024).

Yamada, Y. et al. Terpene synthases are widely distributed in bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112, 857–862 (2015).

Toyomasu, T. et al. Fusicoccins are biosynthesized by an unusual chimera diterpene synthase in fungi. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 3084–3088 (2007).

Mitsuhashi, T., Okada, M. & Abe, I. Identification of chimeric αβγ diterpene synthases possessing both typeII terpene cyclase and prenyltransferase activities. ChemBioChem 18, 2104–2109 (2017).

Chen, R. et al. Systematic mining of fungal chimeric terpene synthases using an efficient precursor-providing yeast chassis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2023247118 (2021).

Jiang, L. et al. Genome-based discovery of enantiomeric pentacyclic sesterterpenes catalyzed by fungal bifunctional terpene synthases. Org. Lett. 23, 4645–4650 (2021).

Faylo, J. L., Ronnebaum, T. A. & Christianson, D. W. Assembly-line catalysis in bifunctional terpene synthases. Acc. Chem. Res. 54, 3780–3791 (2021).

Chen, M., Chou, W. K. W., Toyomasu, T., Cane, D. E. & Christianson, D. W. Structure and function of fusicoccadiene synthase, a hexameric bifunctional diterpene synthase. ACS Chem. Biol. 11, 889–899 (2016).

Ronnebaum, T. A., Gupta, K. & Christianson, D. W. Higher-order oligomerization of a chimeric αβγ bifunctional diterpene synthase with prenyltransferase and class II cyclase activities is concentration-dependent. J. Struct. Biol. 220, 107463 (2020).

Faylo, J. L. et al. Structural insight on assembly-line catalysis in terpene biosynthesis. Nat. Commun. 12, 3487 (2021).

Faylo, J. L., van Eeuwen, T., Gupta, K., Murakami, K. & Christianson, D. W. Transient prenyltransferase–cyclase association in fusicoccadiene synthase, an assembly-line terpene synthase. Biochemistry 61, 2417–2430 (2022).

Tao, H. et al. Discovery of non-squalene triterpenes. Nature 606, 414–419 (2022).

Gaynes, M. N. et al. Structure of the prenyltransferase in bifunctional copalyl diphosphate synthase from Penicillium fellutanum reveals an open hexamer conformation. J. Struct. Biol. 216, 108060 (2024).

Wenger, E. S., Schultz, K., Marmorstein, R. & Christianson, D. W. Engineering substrate channeling in a bifunctional terpene synthase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2408064121 (2024).

Pemberton, T. A. et al. Exploring the influence of domain architecture on the catalytic function of diterpene synthases. Biochemistry 56, 2010–2023 (2017).

Qin, B. et al. An unusual chimeric diterpene synthase from Emericella variecolor and its functional conversion into a sesterterpene synthase by domain swapping. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 1658–1661 (2016).

Abramson, J. et al. Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature 630, 493–500 (2024).

He, H. et al. Discovery of the cryptic function of terpene cyclases as aromatic prenyltransferases. Nat. Commun. 11, 3958 (2020).

Crick, F. H. C. The packing of α-helices: simple coiled coils. Acta Crystallogr. 6, 689–697 (1953).

Hong, Y. J. & Tantillo, D. J. The variediene-forming carbocation cyclization/rearrangement cascade. Aust. J. Chem. 70, 362–366 (2016).

Gerlt, J. A. et al. Enzyme Function Initiative-Enzyme Similarity Tool (EFI-EST): a web tool for generating protein sequence similarity networks. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1854, 1019–1037 (2015).

Gladyshev, E. A., Meselson, M. & Arkhipova, I. R. Massive horizontal gene transfer in bdelloid rotifers. Science 320, 1210–1213 (2008).

Snijder, J. et al. Vitrification after multiple rounds of sample application and blotting improves particle density on cryo-electron microscopy grids. J. Struct. Biol. 189, 38–42 (2017).

Punjani, A., Rubinstein, J. L., Fleet, D. J. & Brubaker, M. A. cryoSPARC: algorithms for rapid unsupervised cryo-EM structure determination. Nat. Methods 14, 290–296 (2017).

Sanchez-Garcia, R. et al. DeepEMhancer: a deep learning solution for cryo-EM volume post-processing. Commun. Biol. 4, 1–8 (2021).

Pettersen, E. F. T. D. et al. UCSF Chimera: a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1605–1612 (2004).

Afonine, P. V. et al. Real-space refinement in PHENIX for cryo-EM and crystallography. Acta Cryst. 74, 531–544 (2018).

Emsley, P., Lohkamp, B., Scott, W. G. & Cowtan, K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Cryst. 66, 486–501 (2010).

Chen, V. B. et al. MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Cryst. 66, 12–21 (2010).

Shannon, P. et al. Cytoscape: A software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 13, 2498–2504 (2004).

Acknowledgements

We thank Kollin Schultz and Ronen Marmorstein for guidance and advice with cryo-EM studies, and we thank the Beckman Center for Cryo-EM (RRID: SCR_022375) at the University of Pennsylvania for instrumentation access in the initial stages of this work. We also thank the Laboratory for BioMolecular Structure (LBMS) at Brookhaven National Laboratory for the use of cryo-EM data collection facilities; the LBMS is supported by the DOE Office of Biological and Environmental Research (KP1607011). Finally, we thank the NIH for grant GM56838 in support of this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.S.W. and D.W.C. conceived the overall study. E.S.W. prepared purified protein samples, conducted activity assays and determined the cryo-EM structures. E.S.W. and D.W.C. analyzed activity data, analyzed cryo-EM structures, and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Thomas Marlovits, who co-reviewed with Rory Hennell James; Joshua Whitehead and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wenger, E.S., Christianson, D.W. Structure of bifunctional variediene synthase yields unique insight on biosynthetic diterpene assembly and cyclization. Nat Commun 16, 5089 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60537-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60537-3