Abstract

Cystic fibrosis is a monogenetic disease complicated by recurrent bacterial lung infections that require chronic antibiotics. Pseudomonas aeruginosa is an increasingly antibiotic-resistant pathogen associated with cystic fibrosis morbidity and mortality. Here, we describe the development of a three-phage cocktail (BX004-A) designed to target a wide range of P. aeruginosa strains. We evaluated BX004-A in Part 1 of a first-in-human double-blind placebo-controlled phase 1b/2a clinical trial, which included nine adult cystic fibrosis patients chronically infected with P. aeruginosa (NCT05010577). BX004-A met the primary endpoints of safety and tolerability. Exploratory endpoints included pharmacokinetics and Pseudomonas aeruginosa sputum density reduction. Efficient phage delivery to the lower respiratory tract was observed, and a potential reduction in P. aeruginosa sputum burden was noted in the phage arm. However, due to the study’s small sample size, definitive conclusions regarding efficacy are limited. These data pave the way toward further development of novel phage-based therapeutics in antibiotic-resistant pulmonary bacterial infections.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is an autosomal recessive disease, caused by mutations in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene1,2. CFTR is an epithelial anion channel that regulates airway homeostasis by transporting chloride and bicarbonate across the membrane of respiratory epithelial cells. Properly functioning CFTR maintains epithelial surface hydration, thus repelling bacteria and supporting proper unfolding of mucins in the lungs. Various mutations in the CFTR gene alter or completely abolish the activity of this channel, causing buildup of thick mucus layers in the lungs3,4,5,6. The main cause for morbidity and mortality of people with CF (pwCF) is chronic pulmonary infection caused by antibiotic-resistant bacteria that thrive in the conditions of the CF respiratory system7,8,9. The most common pathogen associated with severe CF lung disease is Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa), which infects 28.4%–43.2% of adult pwCF according to the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Patient Registry10,11,12. P. aeruginosa is a potent pathogen which inflicts severe lung damage by secreting an assortment of virulence factors13. Standard of care treatment for P. aeruginosa infections includes cycles of inhaled antibiotic treatments or their continuous use, primarily aztreonam, tobramycin, and colistin. However, over time antibiotic resistant P. aeruginosa strains prevail and impede the effectiveness of treatment, leading to substantial patient morbidity and death7,10,14.

Bacteriophage (phage) are viruses that infect bacteria in a strain specific manner. Lytic phages exploit the bacterial cell resources for propagation and eventually lyse the bacterium to free their progenies for subsequent cycles of infection. Since the mechanism by which phages destroy bacteria is orthogonal to that of antibiotics, they are considered a promising strategy to combat antibiotic resistant bacteria15,16. The results of phage administration to pwCF in the context of compassionate treatments have shown positive signs. There were no reports of severe adverse events related to phage treatment, indicating its overall safety17. In addition, positive clinical outcomes, such as improvement in forced expiratory volume in the first second (FEV1), reduction in bacterial burden, and increase in body mass index were observed for some patients who received phage therapy as a compassionate treatment18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25. While these are important pioneering endeavors, compassionate treatments are inherently limited in scope and interpretability, due to the personalization of the treatment and the lack of a control group.

In this work, we set out to develop a potent anti-P. aeruginosa phage cocktail applicable to a broad patient population. We isolate clinically relevant phages and optimize a three-phage cocktail for nebulized therapy. We evaluate this phage cocktail in a randomized first-in-human trial conducted in a population of pwCF chronically infected with P. aeruginosa.

Results and discussion

Generation of a representative panel of P. aeruginosa clinical isolates from pwCF

To generate a representative panel of clinically relevant strains on which broad spectrum phage can later be screened, we obtained a panel of 143 P. aeruginosa strains, each from a distinct donor (139 of which were isolated from sputum of pwCF, Supplementary Data 1). All strains of this panel were sequenced, assembled, and annotated. To confirm that these genomes indeed represent the species, we downloaded all P. aeruginosa genomes available on RefSeq (n = 6640) and clustered them into 1084 groups using Jaccard index26. Superimposing our clinical isolates on these genomic clusters’ representatives confirmed that our strains represent a wide variety of the P. aeruginosa genotypic space (Fig. 1A). General genomic characteristics, including genome size, GC content, and total number of genes, are also comparable between the two groups (Supplementary Data 2). Finally, since anti-phage defense systems (aPDS) are major determinants of phage host range, we sought to confirm that the set of 143 strains properly represents the space of defense systems encoded by P. aeruginosa. To exclude spurious results due to low quality assemblies, we restricted this analysis to the 335 complete RefSeq genomes (Supplementary Data 3). We applied defenseFinder27 to these genomes as well as to the 143 in-house assembled genomes. Prevalence of aPDS was strongly correlated between our panel and the RefSeq complete genomes set (r = 0.89) (Fig. 1B), with similar prevalence ranking for most systems (Fig. 1C). Taken together, these data confirm that the genomic diversity of aPDS in P. aeruginosa is reflected in our clinical isolate collection.

A Tree visualization of genomic distances between RefSeq P. aeruginosa cluster representatives and 143 clinical isolates in our panel, marked with red lines. B Scatter plot depicting the correlation between aPDS prevalence in our panel and that of 335 complete RefSeq genomes. Spearman correlation was applied, p-value (two-sided)= 4.093e-24 (C) Prevalence of aPDS in our panel by descending order. The color scheme represents the prevalence of aPDS across 335 P. aeruginosa complete RefSeq genomes. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Transcriptomic characterization of Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical isolates

Beyond genetic composition, the physiological condition of the target bacteria, and specifically the genes it expresses, is a predictive determinant for the success of phage infection. For example, some bacterial proteins used by phages as receptors are only expressed under specific growth conditions, and hence phage infection in these specific conditions is more successful28,29,30. To determine an in vitro experimental system in which P. aeruginosa presents similar gene expression profiles as in the lungs of pwCF, we studied fresh sputum meta-transcriptomic data from two cohorts31,32 and compared these data to transcriptomic data of P. aeruginosa grown in vitro on three different types of media: (I) synthetic CF medium (SCFM)32, (II) liquid brain heart infusion-supplemented media (BHIS), and (III) solid BHIS on agar plates (Supplementary Data 4). To avoid batch effects, we evenly rarefied all samples and only analyzed reads that mapped to the P. aeruginosa core genome. To quantitatively measure the effect of the growth conditions on the strains, and to evaluate similarity between conditions, we applied a two-dimensional principal component analysis (PCA) to the analyzed genes (Fig. S1), followed by calculation of Euclidian distances between PCA coordinates within groups and between groups (Fig. 2A). When analyzing all core genes, growth on BHIS (both solid and liquid) was found to induce a closer profile to the meta transcriptomic data from lungs, compared to SCFM (Fig. 2B). Focusing the PCA to transcription profiles of bacterial genes regulating or coding for known phage binding molecules33 revealed a similar trend (Fig. 2C). Additionally, as production of extracellular alginate is a known mechanism by which P. aeruginosa protects itself from phage predation34 and is also a common bacterial adaptation observed in CF respiratory infections35, we examined the transcriptomic profile of the alginate biosynthesis pathway genes. Here we observed that growth on solid BHIS induces a pattern more similar to fresh sputum as compared to other conditions tested (Fig. 2D). Thus, while, as expected, no tested medium exactly mimics the bacterial gene expression patterns observed in the CF lung, we found solid BHIS to induce the closest transcriptional profile, specifically of genes relevant to phage infection. This growth medium was therefore selected for further phage isolation and characterization assays.

A Illustration of distance metric applied in (B, C, and D). B, C, D Each panel depicts Euclidean distances of PCA coordinates within (four left boxes) and between (three right boxes) groups. Each dot represents a distance between two coordinates. The tested groups were BHIS solid (red), BHIS liquid (yellow), SCFM (gray) and fresh sputum (blue). Two sets of p-values are given for each analysis: (I) two sided Mann–Whitney U test (MW) testing the null hypothesis that distance distributions within groups are similar to distances between groups, and a Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance (KW) testing the null hypothesis that distances between all groups are similarly distributed. B PCA conducted for transcriptomic profiles of all P. aeruginosa core genes. C PCA conducted for transcriptomic profiles of all P. aeruginosa genes known to play a role in synthesis of phage binding molecules on the bacterial cell surface. D PCA for transcriptomic profiles of all P. aeruginosa genes involved in the alginate biosynthesis pathway. B–D Each datapoint in the figure represents a distance between two biological repeats. Sample sizes were: human sputum–20, SCFM–27, Solid–8, Liquid–8 (see Supplementary Data 4 for further details). Boxplots represent median (bold horizontal central line), quartiles 0.25 and 0.75 (box edges), minimum and maximum (whiskers). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Phage cocktail development

Equipped with a diverse representative panel of clinical P. aeruginosa strains (Fig. 1) and rationally selected in vitro bacterial growth conditions (Fig. 2), we set out to develop an anti-P. aeruginosa phage cocktail for treatment of pwCF. Phage-rich environmental samples were collected and co-incubated with a mixture of P. aeruginosa strains to enrich for relevant phage. The phage fraction of these samples was isolated by standard spotting plaque assay on a top agar lawn of five genetically distinct P. aeruginosa strains (Fig. S2, inner circle). A total of 164 plaques were collected from all plates and their genomes were sequenced and assembled. Phages were then clustered based on genome similarities into groups representing distinct phages. Subsequently, we annotated the phages and computationally analyzed them, screening for strictly lytic phages with no antibiotic-resistance or toxin-coding genes. This process led to the selection of nine genetically unique candidate phages from five different genera (Table S1). The host range of each of these phages was measured by efficiency of plating (EOP) against thirty-one genetically diverse P. aeruginosa strains (Fig. S2, intermediate circle). Data on individual phages was then considered for selection of an optimal phage cocktail. For this, we computed the cumulative host range of all phage combinations, coverage of different bacterial aPDS, taxonomic diversity, and genomic diversity of the phage combination. We then weighed the marginal benefit of each phage cocktail against the number of phages the candidate cocktail contains. Using this approach, we selected a cocktail of three distinct phages which is henceforth coined BX004-A (Fig. 3).

A Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) image of phage BMX-P1 revealed an icosahedral head (~55 nm x 52 nm) and short tail (estimated 14 nm × 11 nm). B Annotation of phage BMX-P1’s 44,725 base-pairs long circular genome. BMX-P1 belongs to the genus Bruynoghevirus. C TEM image of phage BMX-P2 revealed an icosahedral head (71 nm × 66 nm) and long contractile tail (rough estimation 131 nm × 18 nm). D Annotation of phage BMX-P2’s 65,780 base-pairs long circular genome. BMX-P2 belongs to the genus Pbunavirus. E TEM image of phage BMX-P3 revealed an icosahedral head (70 nm × 64 nm) and rigid contractile 119 nm long tail. F Annotation of phage BMX-P3’s 90,869 base-pairs long circular genome. BMX-P3 belongs to the genus Pakpunavirus. Micrographs are representative images from 10 or more repeats, see “Methods” section for further information.

BX004-A characterization and performance

To investigate the mechanism of action of our phages, we isolated rare spontaneously occurring phage-resistant bacterial mutants arising against each of the three phages individually and applied a variant calling algorithm to detect genetic differences between these mutants and their parental phage-susceptible strains, grown side-by-side as controls. Briefly, our variant calling algorithm searches for genes related to phage life cycle by filtering out gene families with observed mutations in phage-susceptible samples and favoring gene families with observed mutations across multiple phage-resistant samples (Supplementary Data 5). Many of the detected genes coded for cell surface components that are known phage receptors, such as BtuB (vitamin b12 transporter), TolC (efflux pump), and genes involved in lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis (Fig. 4A). To assess the expression of these genes in human sputum, we queried the transcriptomic dataset mentioned above (Supplementary Data 4) and observed that all genes discovered in this analysis were expressed in moderate/high levels in sputum. Taken together this suggests high expression of genes that will confer phage sensitivity in sputum.

A Schematic illustration of P. aeruginosa genes involved in phage life cycle, as discovered by our analysis. Phage are color-coded as depicted on the top right legend. The arrows by the gene names represent the average transcript abundance rank of the gene in sputum of pwCF (→: percentile 0.33–0.66, ↑: percentile > 0.66). This graphic was created in BioRender. Weiner, I. (https://BioRender.com/9qfpmc8). B Tree visualization of genomic distances between RefSeq P. aeruginosa cluster representatives and the 143 clinical isolates in our panel. Strain sensitivity to BX004-A is given in the outer circles. C Subpopulation analysis of BX004-A host range on strains containing each of the prevalent P. aeruginosa aPDS (found in at least 5% of strains). Enrichment tests – using Fisher’s exact test with Benjamini Hochberg correction, returned p > 0.05 in all cases. D, E Antibiofilm efficacy, as measured by ATP quantitation (D) and biomass staining (E). The two different strains used in this experiment are color-coded as depicted on the top right corner of panel D. Data shown for each condition is average ± SE across all available biological repeats. Sample sizes per condition alongside all other source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The BX004-A phage cocktail effectively propagated on 106 out of the 143 clinical strains in our panel of clinical P. aeruginosa strains (Fig. S3). Superimposing the resistant and sensitive strains on our genetic map of P. aeruginosa showed that BX004-A is effective against diverse genotypes with no specific phylogeny-related preferences (Fig. 4B). Enrichment tests for aPDS types in resistant strains suggested no significant weakness of our cocktail against any specific defense system (Fig. 4C, p-values in Source Data). However, we observed that resistant strains had significantly more aPDS than their sensitive counterparts (Fig. S4).

As biofilm generated by P. aeruginosa is a major factor associated with virulence and antibiotic resistance in CF36,37, we tested the antibacterial efficacy of BX004-A in biofilm. To this end, we selected two distinct strains varying in biofilm composition (Fig. S5), incubated them overnight in microtiter plates with TSB medium to allow for biofilm maturation, and treated the biofilms with a range of BX004-A concentrations. Phage anti-biofilm efficacy was quantified using a metabolic dye as well as biomass staining. Under these conditions, we observed that BX004-A significantly reduced both microbial counts (Fig. 4D, p = 10−24), and biofilm biomass (Fig. 4E, p = 10−10) in a dose-dependent manner.

Subsequently, the interaction of BX004-A with antipseudomonal antibiotics (used commonly as inhaled antibiotics in CF) was tested in vitro. Four genetically distinct strains were grown in the presence of BX004-A, antibiotics (aztreonam, colistin, or tobramycin), or both. OD600 was measured in 10-min intervals to generate growth curves. The results show no antagonism between BX004-A and any of the tested antibiotics (Fig. S6).

Development and characterization of a nebulized phage formulation

To administer high concentrations of phages directly to the site of pulmonary infection while minimizing exposure to non-infected organs, we chose to deliver the phage cocktail through inhalation. To assess and refine the formulation composition, we developed an in-house aerosol collection system. This system utilizes a breathing simulator to inhale aerosols containing phages, which are generated by a commonly used mesh nebulizer. Then, we used a respiratory low resistance hydrophobic filter to collect the aerosols generated by the nebulizer and determined the titer of each phage using a selective host plaque assay (Fig. 5A). Utilizing this setup, we screened multiple formulations and finally selected a TRIS-based liquid solution in which the nebulization-related losses were less than an order of magnitude of plaque forming units (PFU) per ml (Table S2).

A Experimental setup of aerosol collection system comprised of a general use mesh nebulizer (right), respiratory low resistance filter (middle), and breathing simulator BRS1100 (left). B Phage relative abundance as measured by quantitative PCR using phage-specific primers and probes, across all stages of a Next Generation Impactor. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To achieve lower respiratory tract delivery, aerosols with mass median aerodynamic diameter <5 µm are required38. Thus, aerosolized BX004-A was tested in a Next Generation Impactor in which the aerosols were passed through a series of progressively smaller filters, and the phage content of each stage was measured by quantitative PCR using phage-specific primers and probes. We observed that the three phages were uniformly distributed among the different aerosol sizes (Fig. 5B), and that 58% of our phage dose was localized to aerosols small enough for lower respiratory tract delivery. Thus, by accounting for nebulization-related losses and losses derived from phage localizing to >5 µm aerosols, we achieve a delivered dose of 2.2 × 109 PFU per dose (Table S3).

The final phage cocktail was subjected to safety experiments in an ex-vivo three-dimensional model of reconstituted CF lung tissue, as well as in a Balb/C mouse model. BX004-A did not cause any toxicity, morbidity, or negative clinical signs in either model (Table S4).

Phase 1b/2a clinical trial

To assess the safety, tolerability, and microbiological efficacy of nebulized BX004-A (termed BX004-A-A in the clinical trial), we conducted a first-in-human randomized clinical trial (this study is part 1 of a phase 1b/2a study). Nine adult volunteers with CF and chronic P. aeruginosa pulmonary infection provided written informed consent and were randomly assigned to receive either BX004-A (7 patients) or a placebo vehicle (2 patients), in addition to their standard of care inhaled antibiotics (tobramycin, aztreonam, or colistin); CONSORT diagram is provided in Fig. S7, and detailed patient baseline characteristics are provided in Table S5. Patients received nebulized BX004-A or placebo for seven days; three days of single and multiple ascending doses in the BX004-A arm (Day 1: all subjects received placebo to ensure they tolerated the excipients; Day 2: low-dose BX004-A 1.4 × 108 PFU once, Day 3: high dose BX004-A 1.4 × 1010 PFU once), followed by four days of high dose (1.4 × 1010 PFU/dose) twice daily. The volume of all doses was 4.8 ml. BX004-A was well tolerated by all patients, with no adverse events related to treatment, no adverse events of special interest (e.g., acute pulmonary exacerbations or pulmonary worsening after study drug administration), no clinically significant abnormalities in laboratory results, vital signs or physical exam, and no premature discontinuations from study drug or from the study (detailed safety data is provided in Table S6).

To assess delivery and stability of BX004-A, we measured phage PFU levels in all sputum samples collected (Fig. 6A). As expected, we observed no phage PFU at baseline in any group, and no PFU in the placebo arm at any timepoint. Phage PFU levels in the BX004-A arm were dose- and time-dependent, demonstrating peak concentrations in sputum collected three hours post-dose, and lower levels in samples collected ten hours post-dose. Nonetheless, two patients still had detectable levels of PFU in their sputum on day 15, indicating non-linearity in phage clearance – potentially due to phage replication on resident bacteria. Interestingly, the absence of notable increment in average PFU between days 4 and 8 suggests little or no PFU accumulation during repeated dosing.

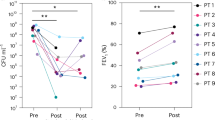

A–D Subjects receiving BX004-A are marked in blue, whereas subjects receiving placebo are marked in orange. Semi-transparent curves represent individual patients, whereas bold lines represent mean ± SE of the group. On day 3, there were two collection timepoints, marked 3a and 3b. Seven patients received BX004-A whereas two patients received placebo. Treatment duration (days 1–8) is indicated by gray shading. A Schematic illustration of the trial design is given above the panel (QD: daily; BID: twice daily), followed by a pharmacokinetics curve. Y-axis values of zero represent no detectable phages in sample. B Pharmacodynamic curves depicting change in P. aeruginosa sputum density over the course of treatment. Y-axis values of zero represent no change in CFU compared to baseline. The p-values (two-sided t-test) are day2:9e-4, day3a:0.045, day3b:0.780, day4:0.035, day8:0.486, day15:0.029. An earlier version of this pharmacodynamic analysis is presented in Table S8. C Relative abundance of P. aeruginosa within the sputum microbiome over time, as measured by 16S rRNA sequencing. The P-values (two-sided t-test) are day1:0.657, day8:0.411, day15:0.207. D Shannon diversity index of sputum microbiome over time, as measured by 16S rRNA sequencing. The p-values (two-sided t-test) are day1:0.940, day8:0.361, day15:0.121. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Significant reductions of P. aeruginosa colony forming units (CFU) in sputum occurred in the treatment arm compared to placebo, on days 4 (1.9 log10 CFU per gram of sputum difference between groups, p = 0.035) and 15 (2.7 log10 CFU per gram of sputum difference between groups, p = 0.029) (Fig. 6B). Interestingly, bacterial reductions were less pronounced on day 8. Monitoring of isolate susceptibility did not show emergence of treatment-related phage or antibiotic resistance at any timepoint (phage susceptibility: Fig. S8, antibiotic susceptibility: Supplementary Data 6), and genomic analysis of P. aeruginosa isolates showed that each patient was consistently colonized with the same strain (as defined by multi-locus sequence typing) throughout the trial (Fig. S9, Table S7), ruling out changes in P. aeruginosa population composition. Additionally, we assessed the impact of two potential confounders in the BX004-A arm: type of inhaled antibiotic and use of a CFTR modulator. Neither subgroup analysis provided conclusive evidence of confounding effects (Fig. S10). However, given the small sample size of Part 1 of this first-in-human study, caution is warranted when interpreting efficacy-related outcomes. Therefore, both statistical significance and the impact of confounders should be monitored in larger studies.

To assess the impact of phage therapy on CF sputum microbiome, we applied 16S rRNA sequencing to the sputum samples collected from patients at baseline, day 8, and day 15. First, we quantified the relative abundance of P. aeruginosa within the sputum microbiome. During treatment we observed opposing trends between the study arms; decrease in P. aeruginosa relative abundance in the BX004-A and increase in the placebo arm (Fig. 6C). In accordance, microbiome alpha diversity rises in the treatment group and declines in the placebo group. (Fig. 6D). Taken together, these data demonstrate the favorable safety profile, feasibility of lower respiratory tract delivery, and preliminary indications of antimicrobial efficacy of the BX004-A phage cocktail. The encouraging outcomes of this study warrant larger-scale trials to delve deeper into the safety and effectiveness of phage therapy. Future research should focus on expanding the cocktail’s host range through the incorporation of novel phages and evaluating the impact of higher phage doses.

Methods

P. aeruginosa sequencing and bioinformatic analysis

Bacterial DNA was extracted using Qiagen DNeasy® UltraClean® Microbial Kit (cat 12224). Library preparation was performed using Illumina’s Tagment DNA Enzyme & Buffer (cat 20034197)39, and libraries were sequenced on an Illumina NextSeq 550 System High or Mid Output Kit PE150 platform, with roughly 3.3 million reads/sample. For nanopore sequencing, library preparation was performed using the ligation based SQK-LSK109 kit by Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) and sequenced on the MinION on a FLO-MIN111 flow cell with ~60x coverage of the expected genome size. Raw nanopore data was base called using guppy 5.0.11 with a high accuracy model matching the library prep kit and flow cell used.

Reads for bacterial genome assembly were trimmed using cutadapt40, subsampled using rasusa41 to 200x of the mean genome size of the species in gtdb42 and assembled using unicycler43. Alternatively, the short reads were trimmed using TrimGalore44 and assembled using spades45.

All P. aeruginosa genomes (n = 6640) were downloaded from Refseq in September 2023. Both in-house and Refseq genomes underwent gene-calling using Prokka v1.14.546, identification of aPDS using DefenseFinder27 and mobile genetic elements using an assortment of relevant tools47,48,49,50,51.

Mash distances

Mash v2.326 was used to calculate the pairwise distances between genomes using sketches of 1000.

Multi-locus sequencing typing

Multi-locus sequencing typing (MLST) characterization was performed on all isolates. Allelic patterns of seven house-keeping genes (acsA, aroE, guaA, mutL, nuoD, ppsA, trpE) were used to determine the sequence type.

Transcriptomics analysis

Dataset

The in vivo sputum meta-transcriptomic samples and isolates grown in the synthetic sputum come from two cohorts31,32. Eight in-house clinical strains were selected based on their genomic diversity. Each in-house clinical strain was grown in two conditions: BHIS liquid (Hy-labs, BP765) or BHIS solid (BD, 237500 with 1.5% agarose and 0.5% Yeast extract). Additional information regarding samples, including links to all raw sequencing data, can be found in Supplementary Table 4.

RNA extraction and preparation of sequencing libraries for RNA-Seq

RNA was extracted using RNeasy(r) Mini (Qiagen, cat# 74106), with a mild modification. Bacterial pellets were lysed using PowerBead Pro tubes (Qiagen, cat#19301) with RLT buffer, on a horizontal vortex adapter for 10 min. The beads were centrifuged for 1 min at 15,000 g, and the resulting supernatant was cleaned following manufacturer’s instructions. RNA was assessed using Tapestation (Agilent), with RIN scores of 8.5 and above. Ribosomal RNA was depleted using Ribo-zero Plus (Illumina, cat#20037135), and sequencing libraires were prepared using NEBNext Ultra II Directional RNA Library Prep Kit (NEB, cat# E7760L). Paired end 150 bp sequencing was carried out on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000, with ≥30 million reads per sample.

Reads pre-processing and mapping

Each sample in the dataset was pre-processed following the same procedure. The adapters were removed using AdapterRemoval software52. Low quality bases and reads shorter than 30 base pairs were discarded using Cutadapt40. Reads were then mapped to the human genome to exclude possible host contamination. The pangenome comprising 341 complete P. aeruginosa strains downloaded from RefSeq was built using roary53 and used as a reference for Salmon reads quantification54. Genes conserved in 99% of the analyzed genomes were defined as species core gene set (n = 5102).

Gene expression analysis

Briefly, reads mapping on each annotated coding sequence of P. aeruginosa reference pangenome were counted using Salmon and counts were normalized using median of ratios in DESeq2 R package55, accounting for library size and gene lengths. Normalized counts were used to evaluate core genes transcriptome similarities using principal component analysis (PCA) as well as heatmap (from the ComplexHeatmap R package) in the biofilm analysis. Additionally, the technical replicates of SCFM were collapsed with DESeq2 function CollapseReplicates.

Phage isolation

Phages were isolated by either direct spotting, or enrichment followed by spotting, of the processed samples on a top agar lawn of multiple selected strains from our collection, using the standard spotting plaque assay. Briefly, 5 µl of processed samples, or 5 µl of processed samples after a 24 h enrichment incubation together with the selected P. aeruginosa strain, were spotted on a top agar layer of the target bacteria and cultured overnight at 37 °C. After incubation, phage plaques were picked from the plate into medium followed by 2 additional rounds of isolation. Lastly, the serially isolated phage was then grown in liquid culture of the selected strain (or one of its isolated mutants) in the logarithmic growth stage.

Efficiency of plating

The sensitivity of P. aeruginosa strains to phages was determined by soft agar plaque assay. Briefly, the tested strains were grown overnight at 37 °C with shaking at 180 rpm to OD600 > 1.5, and 200 μl of culture mixed with 4 ml of soft BHIS agar (0.4%, w/v) supplemented with 1 mM ions was poured onto BHIS agar plate. After 20 min, phages were serially diluted, and 3 μl of the dilutions were dropped on each strain’s lawn. Plates were incubated overnight at 37 °C, and bacterial lysis was assessed. Next, the EOP was calculated by the ratio of plaques produced in the tested strain divided by the number of plaques produced on the host producer strain.

Electron microscope imaging of phages

Samples were prepared for examination with TEM using negative staining method. Samples were mixed gently and applied on freshly glow-discharged copper grids (400 mesh, formvar-carbon coated) for 5 min, washed and stained with one droplet of 1% (w/v) water solution of uranyl acetate (UA). Two grids were prepared for each sample. The grids were observed by transmission electron microscope TALOS L120 (ThermoFisher SCIENTIFIC, The Netherlands), operating at 100 kV. At least 10 grid squares were examined thoroughly, and micrographs (camera Ceta 16 M) were taken randomly at different places on the grid. The same phage morphology was observed in all micrographs of the same phage, as expected. Representative micrographs were selected for Fig. 3.

Phage sequencing and annotation

Phage DNA was extracted by Phage DNA Isolation Kit (cat 46800). Library preparation was performed using Illumina’s Tagment DNA Enzyme & Buffer (cat 20034197)39, and libraries were sequenced on an Illumina Miseq v2 PE250 platform, with roughly 100,000 reads/sample. Reads were assembled into single circular node reference genomes using an in-house assembly tool based on Unicycler43, and phage completeness was verified by CheckV51. Phage annotation was carried out by an in-house computational pipeline developed to gather high confidence functional annotation data from multiple sources. Genes were called with phanotate, a gene caller optimized for phage56. Functional annotation was performed using multiple tools and databases: BlastP and Jackhmmer were used to search NCBI virus protein, PHANTOME57, pVOGs58 and CAZy59 databases, hmmscan to search hmm profiles including large_terminase, small_terminase, pVOGvogs_hmm58 and PHROGs60; InterPro was used to assign domains61; PhANNs62, DeePVP63 and PhageRBPdetection64 (machine learning based predictors) were used to predict structural proteins. Results were manually curated to produce a report of the best informative hits and decide on the final product per protein.

Phage lifestyle

To predict the phage’s lifestyle (lytic/lysogenic), phage DNA sequence was first analyzed using BACPHLIP65 using default parameters. In parallel, the protein sequences encoded by the phage were scanned against an in-house DB of integrase HMMs. Whenever BACPHLIP’s prediction is “lytic” and there were no integrases found, the phage is predicted to be lytic. Otherwise, the phage is predicted to be lysogenic.

Taxonomy

Each phage was assigned with the best aligned International Committee on the Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) reference list #38 on the basis of Blast with -task dc-megablast -evalue 0.1 arguments.

Undesirable gene prediction

Phage protein coding genes were analyzed using AMRfinder v3.11.20 and using HMMER66 against an in-house HMM DB that consists of a set of virulence factors67, a set of toxin genes as defined by the Code of Federal Regulation (https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-40/chapter-I/subchapter-R/part-725/subpart-G/section-725.421) and a PsA specific toxin DB that was built by retrieving all PsA proteins annotated as toxins or proteases from Uniprot68. Annotated genes from the assembly are blasted against the combined database; hits with query coverage of > 70% are globally aligned using Emboss stretcher (http://emboss.sourceforge.net/download/); alignments with identity of > 30% are kept.

Variant calling for phage-resistant mutants

Generation of resistant mutants

The bacterial host was plated from −80 °C glycerol stock on a Cetrimide agar plate and incubated overnight at 37 °C. To isolate rare resistant mutants, two approaches were taken: Approach 1 - WT bacterial overnight culture was plated on a phage lawn and incubated overnight. One colony was grown overnight in 4 ml BHIS at 37 °C with shaking at 180 rpm to OD600 > 1.5. A sample of 100 μl was frozen at −20 °C for later DNA extraction (“pre-infected DNA”). A volume of 100 μl of 10^7 PFU/ml of phage, mixed with 4 ml of soft BHIS agar (0.4%, w/v) and supplemented with 1 mM MMC ions was poured onto a Cetrimide agar plate. After 20 min, the cultured overnight bacteria were streaked on the phage lawn. The same process was repeated without adding phage to the plate. Plates were incubated overnight at 37 °C. Approach 2 - WT bacteria were incubated with phage overnight. One colony was suspended in 500 μl of BHIS medium supplemented with 1 mM MMC ions and divided equally to 100 μl samples. One sample was frozen at −20 °C for later DNA extraction (“pre-infected DNA”). The other samples were combined either with 100 μl of 10^9 PFU/ml of phage or with 100 μl BHIS for WT control. Samples were incubated for 45 min with shaking at 180 rpm at 37 °C to allow phage infection. Then, each culture was plated on a Cetrimide agar plate and incubated overnight at 37 °C. The following day, eight isolated colonies were selected from each plate and resuspended in 100 μl BHIS. Isolated colonies from the WT control plates were frozen at −20 °C for DNA extraction. Mutant colonies were divided, 90 μl of each suspended mutant colony was frozen at −20 °C for DNA extraction, and the rest of the suspension was used for mutant resistant validation. A volume of 90–100 μl from each suspended colony was taken for gDNA extraction. gDNA was extracted using GeneJET Genomic DNA Purification Kit (K0721) according to the manufacturer protocol, and samples were sent to sequencing. Mutants were validated to be resistant to phage by soft agar plaque assay. Briefly, 10 μl from each suspended mutant colony was grown overnight in 4 ml BHIS medium at 37 °C with shaking at 180 rpm to OD600 > 1.5. A volume of 200 μl bacterial culture mixed with 4 ml of soft BHIS agar (0.4%, w/v) supplemented with 1 mM MMC ions was poured onto a BHIS agar plate. After 20 min, phages were serially diluted, and 5 μl of the dilutions were dropped on each strain’s lawn. Plates were incubated overnight at 37 °C, and bacterial lysis was assessed. Bacterial colonies were determined as mutants when no lysis was detected.

Analysis of resistant mutants

Three phage sensitive and genetically distinct P. aeruginosa strains were each co-incubated with each of the BX004-A phages independently for 80 h in 37 °C. The arising phage-resistant mutants were isolated and sequenced side by side with the parental sensitive strain. Breseq69, a variant calling algorithm, was applied to detect genetic differences (insertions, deletions, substitutions) between these resistant mutants and their parental sensitive strains. To detect homologs that mutate across different hosts, proteins encoded by the mutated genes were clustered into protein families using cd-hit 4.8.1 with the following parameters: -n 2 -c 0.4 -s 0.95 -aL 0.95 -g 1. Mutated genes were given a score based on amount of evidence supporting their involvement in phage infection (Supplementary Data 5). Types of supporting evidence considered: protein family mutated in different residues, protein family mutated in multiple independent infection experiments of the same phage-host pair (mutation either occurring in the same residue or not), protein family mutated in response to infection by different phage, protein family mutated in different hosts. Protein sequences were functionally annotated using interProScan 5.48–83.04.

Phage activity in biofilm

Bacterial starters were grown overnight in TSB medium at 37 °C with shaking at 180 rpm to OD600 > 1.5. The cultures were diluted to OD600 = 0.05 in TSB medium (equal to ~4*10^7 CFU/ml), and 150 μl from the diluted culture were dispensed into each well of a white 96 well plate. A total of 150 μl of TSB medium was added to six wells as negative controls. For biofilm formation, the plates were incubated for 16–24 h at 37 °C with shaking at 110 rpm. Following incubation, the supernatant containing the planktonic cells was removed, and the wells with the biofilm were washed using PBS. Then, the biofilm was treated either with: TSB (for NPC control) or BX004-A phage cocktail and incubated for 9 h at 37 °C with shaking at 110 rpm.

Bactiter-Glo quantification

After incubation, the media was removed, and the biofilm was washed twice with PBS and allowed to dry at room temperature for 5 min. Cell viability within the biofilm was assessed using BacTiter-Glo™ Microbial Cell Viability Assay by measuring luminescence (RLU- relative light units). RLU values were converted to CFU values using a strain-specific calibration curve.

Crystal violet quantification

After incubation, the media was removed, and the biofilm was washed twice with PBS. A total of 200 uL Crystal violet (CV) solution (1%) was added to each well and incubated for 10–15 min at room temperature. The CV solution was removed, the wells were washed three times with PBS, and the plate was allowed to dry for several hours. 200 uL of 70% ethanol was added to each well to solubilize the CV and the solution was transferred to a new clear flat bottomed microtiter dish. Quantification was carried out by measuring absorbance in a plate reader at OD600 using 70% ethanol as the blank.

Phage manufacturing, formulation, and characterization of its nebulized aerosol

The manufacturing process of the BX004-A phages was developed to meet regulatory requirements of inhaled drug via nebulization. The phage cocktail used in the clinical trial was manufactured under current good manufacturing practice (cGMP) conditions including upstream bioreactor fermentation and downstream purification including several chromatographic purifications, buffer exchange and sterile filtration. A sterile aqueous liquid TRIS based formulation was developed, supporting phage viability for at least 32 months under refrigerated conditions.

An aerosol collection system was established as presented in Fig. 5A. The system consists of the Breathing Simulator generating a pattern of breathing representative of the adult profile as specified in USP < 1601> and a low resistance inspiratory filter for aerosol collection generated by the evaluated nebulizer. Delivered dose results were determined by two methods–(a) gravimetric analysis (by mass) and (b) viability of the delivered phage in the collected aerosol (by potency). To assure adequate determination of delivered dose by potency, a method for drug recovery from the inspiratory filter was established. The inspiratory filter and the filter holder are washed using TRIS based washing buffer identical to the drug product formulation to minimize the effect of buffer on phage viability. The collected aerosol on the filter is extracted by vigorously shaking the filter with the washing buffer and collection of the recovered sample.

Next generation impactor measurements

The Next Generation Impactor has seven collection cups with different cut-off diameters (5 out of the 7 always between 0.54 and 6.12 microns) which allow the collection of the aerosol produced by the nebulizer. Aerosol is introduced through the induction port of the device and carried as the air flow passes through the impactor in a saw tooth pattern (constants flow at the range of 20–100 L/min). Particle separation and sizing is achieved by successively increasing the velocity of the airstream as it passes through each by forcing it through a series of nozzles containing progressively smaller jet diameters. The collected aerosols are extracted from the caps and further analyzed for potency determination of each size fraction. Fine particles less than a particular aerodynamic diameter (<5 μm) are considered suitable for the treatment.

Safety experiments

Ex-vivo

A 3D model of reconstituted human lung tissue (MucilAir™) derived from primary human airway epithelial cells of a CF patient and developed to simulate human-relevant biological responses was incubated for 24 h with one of three concentrations of BX004-A (5*E5 PFU/mL, 5*E6 PFU/mL, and 5*E7 PFU/mL).

In-vivo

This study was performed in compliance with “The Israel Animal Welfare Act” and following “The Israel Board for Animal Experiments”. The Ethics Committee approved the study on June 4, 2021 under approval number NPC-Ph -IL-21-08-104. The experiment was carried out at Pharmaseed (Ness ziona, Israel). Male Balb/C mice were intranasally administrated with either phage (n = 12) or formulation (n = 8) once a day, for three consecutive days. The phage dose was 1.8 × 108PFU per administration. The experiment also included a naive control group (n = 4). Due to technical reasons, all mice were males. Mice were 7–8 weeks old at study initiation. Animals’ handling was performed according to guidelines of the National Institute of Health (NIH) and the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC). For this study, mice were housed in filtered cages (up to 5 per cage) measuring 36.5 × 20.7 × 13 cm with stainless steel top grill facilitating pelleted food and drinking water in plastic bottle; bedding: steam sterilized clean paddy husk (Envigo, Teklad, Laboratory grade, Sani-chips). Bedding material was changed along with the cage at least twice a week. Animals were fed ad libitum a commercial rodent diet (Teklad Certified Global 18% Protein Diet, Envigo cat# 2018SC). Animals had free access to sterilized and acidified drinking water (pH between 2.5 and 3.5) obtained from the municipality supply and treated according to Pharmaseed’s SOP No. 214: ‘Water system”. The feed arrived from the vendor (Envigo) with a Certificate of Analysis. The water was treated as above. Animals were housed under standard laboratory conditions, air conditioned with adequate fresh air supply (Minimum 15 air changes/hour). Animals were kept in a climate-controlled environment. Temperatures range was 18–24 °C and relative humidity range 30–70% with a 12 h light and 12 h dark cycle (6AM/6PM). Animals were randomly allocated to cages on the day of reception, according to Pharmaseed’s SOP # 027 “Random Allocation of Animals” or if required according to weight. Animals were examined by the Attending Veterinarian (AV) to determine being fit for the study before the experimental phase initiation. Animals were inspected daily for any signs of morbidity or mortality.

Clinical trial

BMX-04-001 was a global study conducted in the USA under Investigational New Drug applications (IND) from the FDA, and in Israel under authorization of the Israeli Ministry of Health. The protocol and informed consent form were approved by the relevant Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) and all patients provided informed consent.

The trial is registered in NIH under the ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT05010577.

This randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter study sought to evaluate the safety and tolerability of BX004-A in CF subjects with chronic P. aeruginosa pulmonary infection. The study was divided into two parts, a single-ascending and multiple-dose phase (Part 1) and a multiple dose phase (Part 2). The results described in this paper pertain to part 1 of this study. The purpose of the study was to evaluate safety and tolerability of BX004-A, and whether BX004-A reduces the PsA burden in the sputum of CF subjects with chronic PsA pulmonary infection.

Enrollment and eligibility

Key inclusion criteria included diagnosed CF patients with chronic P. aeruginosa pulmonary infection (defined as Screening sputum culture and one additional oropharyngeal [throat] or sputum culture with P. aeruginosa isolated within 12 months prior to Screening), in vitro sensitivity of the patient’s P. aeruginosa strain(s) to at least one of the BX004-A phages, at least 105 P. aeruginosa CFU/g of sputum, age ≥18 years, ppFEV1 of 40% or higher, and receiving one of three anti-pseudomonal inhaled standard of care antibiotics: tobramycin, aztreonam, or colistin – throughout the seven days of dosing.

Key exclusion criteria included known hypersensitivity to bacteriophages or excipients in the formulation, receipt of prior bacteriophage therapy within the 6 months prior to screening, recovery of Burkholderia species from respiratory tract within 1 year prior to screening, receipt of systemic (IV or oral) anti-pseudomonal antimicrobials within the 4 weeks prior to Screening (eg, for acute exacerbation), initiation or change in type of CF modulator therapy less than 3 months prior to screening, and pregnant or breastfeeding females.

Trial design

Participants received nebulized BX004-A or placebo for seven days. In the BX004-A arm, patients received a single dose of placebo on day 1, a single dose of 1.4 × 108 PFU on day 2, a single dose of 1.4 × 1010 PFU on day 3, and two daily doses of 1.4 × 1010 PFU on days 4, 5, 6, and 7. On Days 1-4, study drug was administered in clinic (subjects remained in clinic for 3 h post-dose on Days 1-3 and 30 min post-dose on Day 4 to monitor safety parameters); on Days 5-7, study drug was self-administered at home. Sputum samples used for quantification of PFU and CFU were taken at days 1 (baseline), 2, 3 (both pre and post dose), 4, 8, 15. Subjects were all included in a 6-month safety follow-up, with safety monitored by a Data Safety Monitoring Board throughout the study.

Assessment of bacterial counts

Fresh sputum samples were processed at the Center for CF Microbiology (Seattle, Washington, USA) or Hadassah Medical Center Clinical Microbiology Laboratory (Jerusalem, Israel) using established protocols70. Briefly, samples were weighed, and an aliquot was solubilized 1:1 with sputolysin, serially diluted, and plated on MacConkey and DNase agar for quantitative culture of P. aeruginosa. Samples which contained less than 0.3 g of sputum were used for qualitative analysis only. The limit of reliable detection for samples sufficient in volume for quantitative culture is 60 CFU/g. Unique colony morphologies were identified to species level by mass spectrometry and kept frozen in glycerol.

Assessment of susceptibility to BX004-A phages

P. aeruginosa isolates collected from screening and study patients were tested by a solid PFU assay in parallel with control strains. EOP (titer obtained on the patient’s strain/titer obtained on the control strain) was calculated. Patients in screening were considered eligible for the study if all their isolates had an EOP of at least 0.1 to at least one of the cocktail’s phages. Testing was performed at the Microbiological Outcomes Advancement Core (Washington University, Seattle, WA, US).

Assessment of phage counts

Fresh sputum samples were diluted and filtered through a 0.45 µm filter, aliquoted and stored at −80 °C. Filtered samples were tested by PFU assay in duplicates on three hosts, each specific for one bacteriophage of the BX004-A cocktail. Testing was performed at the Microbiological Outcomes Advancement Core (Washington University, Seattle, WA, US). Values were converted to log10 scale. Values of zero were assigned the value of zero in the log10 scale.

16S measurements

DNA extracted from sputum samples was analyzed at the Cystic Fibrosis Microbiome Analysis Center (University of Colorado and Children’s Hospital Colorado, Colorado, US). Total bacterial load was determined by the Nadkarni qPCR assay71,72. Bacterial community profiles were determined by broad-range amplification of V1/V2 and sequence analysis of 16S rRNA genes73,74. Species richness was assessed using the Shannon index.

Research animals

Animal studies described in this manuscript are compliant with all relevant ethical regulations and were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC).

Human research participants

All research involving human participants described in this manuscript has been approved by the relevant ethics committees and regulatory agencies.

Informed consent was obtained from all human participants.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data are available in the main text or the supplementary materials. Bacterial genomic data are available on NCBI (specific accessions are given in Supplementary Data 1, Supplementary Data 2, Supplementary Data 3, Supplementary Data 4). Phage genomic data are available on NCBI (specific accessions are given in Table S1). Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

Custom code used to generate results presented in this manuscript will be shared upon reasonable request.

References

Riordan, J. R. et al. Identification of the cystic fibrosis gene: cloning and characterization of complementary DNA. Science (1979) 245, 1066–1073 (1989).

Rommens, J. M. et al. Identification of the cystic fibrosis gene: chromosome walking and jumping. Science (1979) 245, 1059–1065 (1989).

Bobadilla, J. L., Macek, M., Fine, J. P. & Farrell, P. M. Cystic fibrosis: a worldwide analysis of CFTR mutations - correlation with incidence data and application to screening. Hum. Mutat. 19, 575–606 (2002).

de Boeck, K., Zolin, A., Cuppens, H., Olesen, H. V. & Viviani, L. The relative frequency of CFTR mutation classes in European patients with cystic fibrosis. J. Cyst. Fibros. 13, 403–409 (2014).

Bareil, C. et al. UMD-CFTR: a database dedicated to CF and CFTR-related disorders. Hum. Mutat. 31, 1011–1019 (2010).

Bareil, C. & Bergougnoux, A. CFTR gene variants, epidemiology and molecular pathology. Arch. de. Pediatr. 27, eS8–eS12 (2020).

Durda-Masny, M. et al. The determinants of survival among adults with cystic fibrosis—a cohort study. J. Physiol. Anthropol. 40, 19 (2021).

Pritt, B., O’Brien, L. & Winn, W. Mucoid Pseudomonas in cystic fibrosis. Am. J Clin Pathol 128, 32 (2007).

Malhotra, S., Hayes, D. & Wozniak, D. J. Cystic fibrosis and pseudomonas aeruginosa: the host-microbe interface. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 32, e00138–18 (2019).

Marshall, B. et al. Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Patient Registry 2020 Annual Data Report. https://www.cff.org/sites/default/files/2021-11/Patient-Registry-Annual-Data-Report.pdf (2020).

Marshall, B. C. et al. Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Patient Registry 2021 Annual Data Report. (2021).

CFF. 2022 CF Patient Registry Annual Data Report. https://www.cff.org/media/31216/download (2022).

Qin, S. et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa: pathogenesis, virulence factors, antibiotic resistance, interaction with host, technology advances and emerging therapeutics. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 7, 199 (2022).

Bouvier, N. M. Cystic fibrosis and the war for iron at the host-pathogen battlefront. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, 1480–1402 (2016).

Svoboda, E. Bacteria-eating viruses could provide a route to stability in cystic fibrosis. Nature 583, S8–S9 (2020).

Federici, S. et al. Targeted suppression of human IBD-associated gut microbiota commensals by phage consortia for treatment of intestinal inflammation. Cell 185, 2879–2898.e24 (2022).

Stacey, H. J., de Soir, S. & Jones, J. D. The safety and efficacy of phage therapy: a systematic review of clinical and safety trials. Antibiotics 11, 1340 (2022).

Chan, B. K., Stanley, G., Modak, M., Koff, J. L. & Turner, P. E. Bacteriophage therapy for infections in CF. Pediatric Pulmonol. 56, S4–S9 (2021).

Dedrick, R. M. et al. Engineered bacteriophages for treatment of a patient with a disseminated drug-resistant Mycobacterium abscessus. Nat. Med. 25, 730–733 (2019).

Dedrick, R. M. et al. Phage therapy of mycobacterium infections: compassionate-use of phages in twenty patients with drug-resistant mycobacterial disease. Clin. Infect. Dis. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciac453 (2022).

Aslam, S. et al. Lessons learned from the first 10 consecutive cases of intravenous bacteriophage therapy to treat multidrug-resistant bacterial infections at a single center in the United States. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 7, ofaa389 (2020).

Aslam, S. et al. Early clinical experience of bacteriophage therapy in 3 lung transplant recipients. Am. J. Transplant. 19, 2631–2639 (2019).

Law, N. et al. Successful adjunctive use of bacteriophage therapy for treatment of multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in a cystic fibrosis patient. Infection 47, 665–668 (2019).

Kutateladze, M. & Adamia, R. Phage therapy experience at the Eliava Institute. Med Mal. Infect. 38, 426–430 (2008).

Kvachadze, L. et al. Evaluation of lytic activity of staphylococcal bacteriophage Sb-1 against freshly isolated clinical pathogens. Micro. Biotechnol. 4, 643–650 (2011).

Ondov, B. D. et al. Mash: Fast genome and metagenome distance estimation using MinHash. Genome Biol https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-016-0997-x (2016).

Tesson, F. et al. Systematic and quantitative view of the antiviral arsenal of prokaryotes. Nat. Commun. 13, 2561 (2022).

Charbit, A., Gehring, K., Nikaido, H., Ferenci, T. & Hofnung, M. Maltose transport and starch binding in phage-resistant point mutants of maltoporin. functional and topological implications. J. Mol. Biol. 201, 487-493 (1988).

Biswas, B. et al. Propagation of S. aureus Phage K in Presence of Human Blood. Biomed J Sci Tech Res. 18, 13815–3819 (2019).

Henry, M., Lavigne, R. & Debarbieux, L. Predicting in vivo efficacy of therapeutic bacteriophages used to treat pulmonary infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 57, 5961 (2013).

Rossi, E., Falcone, M., Molin, S. & Johansen, H. K. High-resolution in situ transcriptomics of Pseudomonas aeruginosa unveils genotype independent patho-phenotypes in cystic fibrosis lungs. Nat. Commun. 9, 3459 (2018).

Cornforth, D. M. et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa transcriptome during human infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 115, E5125–E5134(2018).

Vaitekenas, A., Tai, A. S., Ramsay, J. P., Stick, S. M. & Kicic, A. Pseudomonas aeruginosa resistance to bacteriophages and its prevention by strategic therapeutic cocktail formulation. Antibiotics 10, 145 (2021).

Scanlan, P. D. & Buckling, A. Co-evolution with lytic phage selects for the mucoid phenotype of Pseudomonas fluorescens SBW25. ISME J. 6, 1148–58 (2012).

Hogardt, M. & Heesemann, J. Adaptation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa during persistence in the cystic fibrosis lung. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 300, 557–562 (2010).

Li, Z. et al. Longitudinal development of mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection and lung disease progression in children with cystic fibrosis. JAMA 293, 4172–9 (2005).

Aaron, S. D. et al. Single and combination antibiotic susceptibilities of planktonic adherent, and biofilm-grown Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates cultured from sputa of adults with cystic fibrosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40, 4172–9 (2002).

Touw, D. J., Brimicombe, R. W., Hodson, M. E., Heijerman, H. G. M. & Bakker, W. Inhalation of antibiotics in cystic fibrosis. Eur. Respir. J. 8, 1594–1604 (1995).

Baym, M. et al. Inexpensive multiplexed library preparation for megabase-sized genomes. PLoS One 10, 1–15 (2015).

Martin, M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet. J. 17, 10–12 (2011).

Hall, M. B. Rasusa: Randomly subsample sequencing reads to a specified coverage. JOSS, 7, 3941 (2022)

Parks, D. H. et al. A complete domain-to-species taxonomy for Bacteria and Archaea. Nat. Biotechnol. 38, 1079–1086 (2020).

Wick, R. R., Judd, L. M., Gorrie, C. L. & Holt, K. E. Unicycler: resolving bacterial genome assemblies from short and long sequencing reads. PLoS Comput Biol 13, e1005595 (2017).

Krueger, F., James, F., Ewels, P., Afyounian, E. & Schuster-Boeckler, B. FelixKrueger/TrimGalore. Babraham Bioinformatics https://github.com/FelixKrueger/TrimGalore (2021).

Bankevich, A. et al. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J. Comput. Biol. 19, 455–477 (2012).

Seemann, T. et al. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics 30, 2068–2069 (2014).

Xie, Z. & Tang, H. ISEScan: automated identification of insertion sequence elements in prokaryotic genomes. Bioinformatics 33, 3340–3347 (2017).

Robertson, J. & Nash, J. H. E. MOB-suite: software tools for clustering, reconstruction and typing of plasmids from draft assemblies. Microb Genom 4, e000206 (2018).

Bertelli, C. & Brinkman, F. S. L. Improved genomic island predictions with IslandPath-DIMOB. in Bioinformatics 34, 2161–2167 (2018).

Guo, J. et al. VirSorter2: a multi-classifier, expert-guided approach to detect diverse DNA and RNA viruses. Microbiome 9, 37 (2021).

Nayfach, S. et al. CheckV assesses the quality and completeness of metagenome-assembled viral genomes. Nat Biotechnol 39, 578–585 (2021).

Schubert, M., Lindgreen, S. & Orlando, L. AdapterRemoval v2: rapid adapter trimming, identification, and read merging. BMC Res Notes 9, 88 (2016).

Page, A. J. et al. Roary: rapid large-scale prokaryote pan genome analysis. Bioinformatics 31, 3691–3693 (2015).

Patro, R., Duggal, G., Love, M. I., Irizarry, R. A. & Kingsford, C. Salmon: fast and bias-aware quantification of transcript expression using dual-phase inference. Nat Methods 14, (2017).

Love, M. I., Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 15, 550 (2014).

Mcnair, K., Zhou, C., Dinsdale, E. A., Souza, B. & Edwards, R. A. PHANOTATE: a novel approach to gene identification in phage genomes. Bioinformatics 35, 4537–4542 (2019).

McNair, K., Bailey, B. A. & Edwards, R. A. PHACTS, a computational approach to classifying the lifestyle of phages. Bioinformatics 28, 614-8 (2012).

Grazziotin, A. L., Koonin, E. V. & Kristensen, D. M. Prokaryotic virus orthologous groups (pVOGs): a resource for comparative genomics and protein family annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, D491–D498 (2017).

Terrapon, N., Lombard, V., Drula, E., Coutinho, P. M. & Henrissat, B. The CAZy database/the carbohydrate-active enzyme (CAZy) database: principles and usage guidelines. in A Practical Guide to Using Glycomics Databases. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-4-431-56454-6_6 (2017).

Terzian, P. et al. PHROG: Families of prokaryotic virus proteins clustered using remote homology. NAR Genom Bioinform 3, lqab067 (2021).

Blum, M. et al. The InterPro protein families and domains database: 20 years on. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, D344–D354 (2021).

Cantu, V. A. et al. PhANNs, a fast and accurate tool and web server to classify phage structural proteins. PLoS Comput Biol 16, e1007845 (2020).

Fang, Z., Feng, T., Zhou, H. & Chen, M. DeePVP: Identification and classification of phage virion proteins using deep learning. Gigascience 11, giac076 (2022).

Boeckaerts, D., Stock, M., De Baets, B. & Briers, Y. Identification of phage receptor-binding protein sequences with hidden markov models and an extreme gradient boosting classifier. Viruses 14, 1329 (2022).

Hockenberry, A. J. & Wilke, C. O. BACPHLIP: predicting bacteriophage lifestyle from conserved protein domains. PeerJ 9, e11396 (2021).

Finn, R. D., Clements, J. & Eddy, S. R. HMMER web server: Interactive sequence similarity searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, W29–W37 (2011).

Sayers, S. et al. Victors: a web-based knowledge base of virulence factors in human and animal pathogens. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D693–D700 (2019).

Bateman, A. et al. UniProt: the Universal Protein Knowledgebase in 2023. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, D523–D531 (2023).

Deatherage, D. E. & Barrick, J. E. Identification of mutations in laboratory-evolved microbes from next-generation sequencing data using breseq. Methods in Mol. Biol. 1151, 165–88 (2014).

Saiman, L. & Siegel, J. Infection control recommendations for patients with cystic fibrosis: Microbiology, important pathogens, and infection control practices to prevent patient-to-patient transmission. Am. J. Infect. Control 31, S1–S62 (2003).

Nadkarni, M. A., Martin, F. E., Jacques, N. A. & Hunter, N. Determination of bacterial load by real-time PCR using a broad-range (universal) probe and primers set. Microbiology (N Y) 148, 257–266 (2002).

Zemanick, E. T. et al. Reliability of quantitative real-time PCR for bacterial detection in cystic fibrosis airway specimens. PLoS One 5, e15101 (2010).

Zemanick, E. T. et al. Airway microbiota across age and disease spectrum in cystic fibrosis. Eur.Respir. J. 50, 1700832 (2017).

Robertson, C. E. et al. Explicet: graphical user interface software for metadata-driven management, analysis and visualization of microbiome data. Bioinformatics 29, 3100 (2013).

Acknowledgements

We would like to deeply thank the following collaborators for their contribution to the clinical trial detailed in this manuscript: • Center for Cystic Fibrosis Microbiology (CCFM), Seattle Children’s Hospital, Seattle, WA, US. • Microbiological Outcomes Advancement Core (MOAC), Washington University, Seattle, WA, US. • Hadassah Medical Center Clinical Microbiology Laboratory, Jerusalem, Israel. • Cystic Fibrosis Microbiome Analysis Center (CFMAC), University of Colorado and Children’s Hospital Colorado, CO, US. • Rho, Inc (study enrollment and execution). • The Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (CFF) and the Cystic Fibrosis Therapeutics Development Network (TDN). • J.P. - for his excellent clinical operations work. • Prof. A.B. and Prof. J.B.-D. - for productive discussions and consultation. • Actu-Real (statistical analysis). • Members of Data Monitoring Committee (DMC) of the CFF Data Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB): Dr.L.M.Q.l (DMC Chair), Dr N.N. (DMC Member, Infectious Diseases), Dr R.R., (DMC Member, Adult CF, Internal Medicine), Dr R.K. (DMC Biostatistician), Ms.L.K. (DMC Patient Representative Member), K.C.-L. (DMC Study Coordinator), L.H. (DMC Study Coordinator), G.J. (DMC Study Coordinator). • The patients who volunteered to participate in our study and their clinicians. Israel Innovation Authority grant 74353. Israel Innovation Authority grant 77602. Israel Innovation Authority grant 80327. Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (CFF) equity investment.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: A.C., E.K., J.K., L.Z., M.K., M.B., M.G., N.Z., R.Sor., S.P., and X.U. Research: B.B., D.B., E.S., H.S., I.W., I.V., I.S., J.J., J.N., L.Z., M.O., N.Buc., R.M., S.N., T.G., T.A., and Y.E. Development: A.M., E.Kar., E.S., H.N., I.G., I.L., J.G., M.G., N.T., N.B., R.V., S.P., T.C., U.R., X.U., and Y.E. Manufacturing: I.L., R.S., V.L., Y.T., and Y.Z. Supervision: A.C., E.K., I.W., J.K., M.K., M.B., M.G., V.L., and I.G. Writing: H.S., I.W., M.O., N.Z., R.S., and U.R.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

All authors marked as 1 or 2 are current or past employees at BiomX Ltd. R. Sorek and E. Kerem are consultants for BiomX. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Ronald Geskus, Gordon Yung, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Weiner, I., Kahan-Hanum, M., Buchstab, N. et al. Phage therapy with nebulized cocktail BX004-A for chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections in cystic fibrosis: a randomized first-in-human trial. Nat Commun 16, 5579 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60598-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60598-4

This article is cited by

-

Considerations and perspectives on phage therapy from the transatlantic taskforce on antimicrobial resistance

Nature Communications (2025)