Abstract

Lipo-chitooligosaccharides (LCO) and short-chain chitooligosaccharides (CO) are produced by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) and activate the plant symbiosis signalling pathway, which is essential for mycorrhiza formation. High-affinity LCO receptors belonging to the LysM receptor-like kinase (LysM-RLK) phylogenetic group LYR-IA play a role in AM establishment, but it is unclear which proteins are the plant high-affinity short-chain CO receptors. Here we studied members of the uncharacterized LYR-IB group, and found that they show high affinity for LCO, short- and long-chain CO, and play a complementary role with the LYR-IA receptors for AM establishment. While LYR-IB knock out mutants had a reduced AMF colonization in several species, constitutive/ectopic expression in wheat increased AMF colonization. LYR-IB function is conserved in all tested angiosperms, but in most japonica rice a deletion creates a frameshift in the gene, explaining differences in AM phenotypes between rice and other monocot single LYR-IA mutants. In conclusion, we identified a class of LysM-RLK receptors in angiosperms with unique biochemical properties and a role in both LCO and CO perception for AM establishment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Arbuscular mycorrhiza (AM) is an ancient mutualistic symbiosis between Glomeromycotina fungi and most plant species, including crops such as rice and wheat. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) provide plants with nutrients gathered in the soil through an extended extraradical mycelium in exchange for carbohydrates and lipids1. Host root colonization by AMF relies on a signaling pathway called the common symbiosis signaling pathway (CSSP)2. So far, two types of chitinic signal molecules produced by AMF, lipo-chitooligosaccharides (LCO)3 and both short-chain and long-chain chitooligosaccharides (CO)4,5 induce at nM concentrations oscillations in calcium concentration in and around root cell nuclei (calcium spiking)6, a hallmark of CSSP activation. In addition, LCO and short-chain CO stimulate AMF colonization when added exogenously3,7.

During evolution, the CSSP was recruited for nodule organogenesis and colonization by nitrogen-fixing bacteria in nodulating plant species2. In most legumes, including Medicago truncatula, the CSSP is activated by specific LCO structures produced by their nitrogen-fixing rhizobial partner leading to calcium spiking and nodulation.

Both LCO and short-chain CO are composed of 4 to 5 N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) residues. In addition, LCO contain a lipid on the terminal non-reducing sugar. In contrast to LCO and short-chain CO, long-chain CO (mainly those containing 7 or 8 GlcNAc) and peptidoglycan (PGN) fragments (a polymer of N-acetylmuramic acid and GlcNAc), induce defence responses in plants.

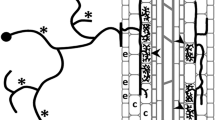

Although inducing different types of responses, all these GlcNAc-containing molecules are perceived by plant specific plasma membrane localized proteins containing three Lysin motifs (LysM) in their extracellular region (ECR). LysM receptor-like kinases (LysM-RLKs) also have a transmembrane domain (TM) and an intracellular region (ICR) with an active kinase domain (LYK type) or an inactive kinase domain (LYR type), while LysM-receptor like proteins (LysM-RLPs) have a GPI anchor site and no ICR (LYM type). LYR and LYM proteins interact with LYK proteins to form receptor complexes in which in most cases the LYR or the LYM has high affinity and specificity for a ligand and the LYK lower affinity and specificity for ligands, but a critical role in signal transduction8, including for AM establishment9. Hence, LYR and LYM are generally involved in specific signaling pathways, while, through interaction with several LYR and LYM, LYK are involved in multiple signaling pathways leading to symbiosis or defence8. LysM-RLK/P numbers vary between species (from 8 to more than 20) but several phylogenetic groups are conserved between angiosperms8.

Several LysM-RLK/Ps have been described as high affinity LCO or long-chain CO binding proteins10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19. Overall, the ligand binding properties of the proteins are conserved between orthologs belonging to conserved phylogenetic groups in angiosperms8, except some exceptions likely resulting from evolutionary processes associated with gain or loss of symbiosis abilities2,19. For example, members of the LYM-II group generally have high affinity for long-chain CO and members of the LYR-IA and LYR-IIIA groups generally have high affinity for LCO. However, no phylogenetic group in which members have conserved high affinity for short-chain CO has yet been identified.

The LYR and LYM proteins with well characterized biochemical properties were also studied for their roles in defence or symbioses. In non-legumes, members of the LYR-IA group plays a role in AM establishment17,20 and LCO signaling21. However, knock out (KO) mutants were not completely deficient in their ability to be colonized by AMF, in contrast to mutants in the downstream CSSP, suggesting that additional receptors are involved. Since LYR-IA proteins are have higher affinity LCO than CO, it is thus expected that yet uncharacterized high affinity short-chain CO receptors play a complementary role in CSSP activation.

AM has been lost in some plant species, such as the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana. This and other non-host plant species have lost some of the key genes required for this association such as genes of the CSSP2. Orthologs of genes missing in non-host plant species are thus likely to be involved in AM in host species.

Here we aimed to identify additional LysM-RLK involved in AM establishment and in particular high affinity short-chain CO receptors.

Results

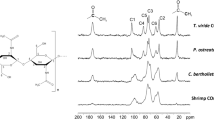

Petunia hybrida and Brachypodium distachyon LYR-IB LysM-RLKs have high affinity for LCO and CO

LYR-IA LysM-RLKs are proteins predominantly with high affinity for LCO, only found in mycotrophic plant species and involved in AM establishment. The LYR-IB phylogenetic group is the closest to the LYR-IA group, and LYR-IB genes are also only present in mycotrophic plant species, generally represented by a single gene except in polyploid species (Supplementary Fig. 1). We hypothesized that members of this group are also involved in symbiotic signal perception and AM establishment.

In order to perform ligand binding assays with symbiotic signals, we used an Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transient expression system to produce PhLYK9-YFP and BdLYR2-YFP in Nicotiana benthamiana leaves. We also expressed PhLYK15-YFP, a P. hybrida LysM-RLK belonging to another phylogenetic group (LYR-IIB), as a control. All proteins were found, by microscopy, in the cell periphery (Fig. 1a) and immunodetected in the membrane fractions extracted from the corresponding N. benthamiana leaves (Fig. 1b). Membrane fractions were used for ligand binding assays using either a radiolabelled LCO (LCO-V(C18:1,NMe,35S)) or a crosslinkable biotinylated CO5 (CO5-biot) and competitions with unlabeled LCO and CO. Binding of the radiolabelled LCO was detected in membrane fractions from leaves expressing PhLYK9-YFP and BdLYR2-YFP but not from leaves expressing PhLYK15-YFP or from untransformed leaves (Fig. 1b). Affinity of PhLYK9 and BdLYR2 for LCO-V(C18:1,NMe,S) was measured by cold saturation experiments. Scatchard plot analysis revealed a single class of binding sites (Fig. 1c) with dissociation constants (Kd) of 2.8 nM ± 0.8 nM (n = 3) and 2.6 nM ± 1.1 (n = 5), respectively. We then determined whether the PhLYK9 and BdLYR2 binding sites are specific for LCO through competition assays between the radiolabelled LCO and 1 µM of unlabeled LCO, CO, chitosan (deacylated chitin) fragments or 10 mg/L of PGN fragments. CO4 and CO8 were efficient competitors of the radiolabelled LCO but not the chitosan or PGN fragments (Fig. 1d). We further characterized the binding site of both proteins by competition assays between the radiolabelled LCO and a range of unlabeled CO4 or CO8 (Fig. 1e) and determined inhibitory constants (Ki) between of 7.5 and 44.6 nM (Fig. 1f).

a Images of epidermal cells from N. benthamiana leaves expressing the indicated proteins tagged with YFP. Scale bars represent 20 µm. b Specific binding of LCO-V(C18:1,NMe,35S) to PhLYK9 and BdLYR2. Bars represent the mean specific LCO-binding/µg membrane proteins. n = two replicates on two independent batches of membrane fractions containing the indicated proteins or from untransformed leaves. Immunodetection with anti YFP antibodies in 10 µg of the indicated membrane fractions. c Affinity of PhLYK9 and BdLYR2 for LCO-V(C18:1,NMe,S). Scatchard plots of cold saturation experiments using membrane fractions containing the indicated proteins and a range of LCO-V(C18:1,NMe,S) concentrations as competitor. The plots are representative of experiments performed with two independent batches of membrane fractions. d Specificity of PhLYK9 and BdLYR2 LCO-binding sites for LCO versus other GlcNAc-containing molecules. Bars represent the mean percentage of specific LCO-V(C18:1,NMe,35S) binding competition in the presence of 2 μM of the indicated competitors, except for PGN fragments which were used at 10 mg/L. n = technical replicates. LCO is LCO-V(C18:1,NMe,S). e Affinity of PhLYK9 and BdLYR2 for CO4 and CO8. Competitive inhibition of the radiolabelled LCO-V(C18:1,NMe,S) binding to membrane fraction containing the indicated proteins, using a range of concentrations of unlabeled CO4 or CO8 as competitors. f Affinities of PhLYK9 and BdLYR2 LCO-binding sites for the indicated ligands, deduced from saturation and competitive inhibition experiments. Statistical differences (p < 0.05) were calculated using a pairwise two-sided Student’s t-test in b, d.

As a complementary approach, we used a crosslinkable biotinylated CO5 (CO5-biot, Fig. 2a, Supplementary Fig. 2a) to measure the ligand binding properties of LYR-IB proteins. CO5-biot can activate Ca2+ spiking in tomato roots in the same concentration range as unmodified CO5 (Supplementary Fig. 2b, c), although with a slightly lower efficacy, showing that CO5-biot is an active signal but that receptor affinity for CO5 may be slightly underestimated in CO5-biot saturation experiments. Binding of CO5-biot, was observed on membrane fractions containing PhLYK9-YFP but not on those containing PhLYK15-YFP (Fig. 2b). To confirm that CO5-biot was crosslinked to PhLYK9-YFP, we immunopurified PhLYK9-YFP and PhLYK15-YFP. CO5-biot was co-purified with PhLYK9 (Fig. 2c). CO5-biot was also detected in membrane fraction containing BdLYR2 (Fig. 2d). Affinity of PhLYK9-YFP and BdLYR2-YFP for CO5-biot was measured by saturation experiments. Saturation was achieved with 50 nM CO5-biot and dissociation constants (Kd) were estimated around 25 nM (Fig. 2e, f, Supplementary Fig. 3a, b). To determine whether CO5 biotinylation affects the determination of protein affinity for CO5, we performed a competition assay between CO5-biot and a range of unlabeled CO5 and found inhibitory constants (Ki) estimated around 10 nM for BdLYR2 (Supplementary Fig. 3c), demonstrating that CO5-biot saturation gives a reliable measure of the affinity for CO5. Finally, we also performed competition assays between CO5-biot and a range of unlabeled LCO and also found inhibitory constants (Ki) estimated around 25 nM (Fig. 2g, h).

a Schematic representation of the cross-linkable biotinylated CO5 (CO5-biot). The triazine group forms a covalent bound with adjacent proteins and the biotin-labeled protein can be detected by Western-blotting (WB). b CO5-biot binding to 10 µg of N. benthamiana membrane proteins containing PhLYK9-YFP or PhLYK15-YFP. Membrane fractions were incubated with or without 10 nM CO5-biot and WB performed using sequentially anti-GFP antibodies and streptavidin on the same membrane. The arrowhead indicates the position of PhLYK9-YFP, whereas * indicates an N. benthamiana endogenously biotinylated protein. c, d CO5-biot binding to immunopurified PhLYK9, PhLYK15 or BdLYR2. 250 µg of membrane proteins containing the indicated proteins were incubated with or without 1 µM CO5-biot, before protein solubilization and purification using anti-GFP beads. Note that the endogenously biotinylated protein detected in membrane fractions (b) was not detected anymore after protein purification. Affinity of PhLYK9 (e) and BdLYR2 (f) for short-chain CO. Saturation experiments on 10 µg of membrane proteins using a range of concentrations of CO5-biot. Specificity of the PhLYK9 (g) and BdLYR2 (h) CO-binding sites for CO versus LCO. Ten µg of membrane proteins were incubated with or without 10 nM CO5-biot and a range of unlabeled LCO-V(C18:1,NMe,S). i, j CO5-biot binding to membrane proteins containing equivalent amounts of the indicated proteins. Membrane fractions were incubated with or without 10 nM CO5-biot. The blots represent data obtained four times in (e, f) and twice in (g, h).

The two LYR-IB proteins, PhLYK9 and BdLYR2, each have at least one binding site with high affinity for both LCO and CO, and possibly a slightly higher affinity for LCO than for CO (maximum 1 log10). In contrast, LYR-IA proteins have a LCO binding site with a much higher affinity for LCO than for CO (about 3 log10)14,17. To exclude that LYR-IA proteins have an additional high affinity short-chain CO binding site, we measured CO5-biot binding to PhLYK10 and BdLYR1, the LYR-IA protein from P. hybrida and B. distachyon, respectively. No binding was detected to these proteins using 10 nM of CO5-biot, in comparison to PhLYK9 and BdLYR2 (Fig. 2i), while PhLYK10 and BdLYR1 are able to bind LCO (Supplementary Fig. 3d). The lack of high affinity for CO5-biot was confirmed for BdLYR1 using a range of CO5-biot concentrations (Supplementary Fig. 3e). LysM-RLK/Ps belonging to other phylogenetic groups are known to have high affinity for long-chain CO9,10,12. We measured CO5-biot binding to the rice OsCEBIP (LYM-II group) and the M. truncatula MtLYR4 (LYR-IIIC group). No signal was detected for OsCEBIP and MtLYR4 using 10 nM of CO5-biot, in comparison to BdLYR2 (Fig. 2j) while the OsCEBIP and MtLYR4 were able to bind CO5-biot and/or CO7-biot at higher concentration (Supplementary Fig. 4a, b). We also tested the affinity of the two other LYR proteins from B. distachyon, BdLYR3 and BdLYR4 (belonging to the LYR-III group) and the OsCEBIP ortholog in B. distachyon, BdLYM2, for CO5-biot and CO7-biot. All these proteins showed lower affinity for short-chain CO than BdLYR2 (Supplementary Fig. 4c).

As an alternative method to produce the proteins, we expressed ECRs of BdLYR2 and BdLYR1 in insect cells and used MicroScale Thermophoresis (MST) to perform ligand binding assays. Pure BdLYR1 and BdLYR2 proteins were obtained by FPLC (Fig. 3a). We labeled the proteins with a red fluorophore and performed MST using a range of concentrations of unlabeled LCO or CO (Fig. 3b). For BdLYR2 ECR, similar ranges of affinity were determined for LCO, CO4, CO5 and CO7 (Fig. 3c, d, Supplementary Fig. 5). For BdLYR1 ECR, affinity for CO4, CO5 and CO7 was much lower than for LCO (Fig. 3e, f, Supplementary Fig. 5). We also performed MST with unlabeled proteins and a fluorescent CO5 (Fig. 3g, Supplementary Fig. 5i) and observed higher affinity of BdLYR2 ECR than BdLYR1 ECR for the CO5-BODIPY (Fig. 3h, i). Finally, to compare affinity of ECRs to those of full-length proteins using the same binding assays, we measured CO5-biot crosslinking to ECRs of BdLYR2 and BdLYR1 (Supplementary Fig. 5j). CO5-biot was detected on BdLYR2 ECR but not on that of BdLYR1 ECR, and BdLYR2 ECR affinity for CO5 was lower than that of full-length BdLYR2. Despite the selectivity of BdLYR1 and BdLYR2 for LCO and CO being the same as those obtained with full-length proteins expressed in N. benthamiana leaves, the affinities found with ECR expressed in insect cells were much lower (µM range versus nM range).

a SDS-PAGE and coomassie blue staining of purified BdLYR2-ECR or BdLYR1-ECR and 400 ng or 200 ng of BSA respectively. b Schematic representation molecules used for MST: Unlabeled ligands and ECR labeled with a red fluorophore. c Curves of LCO and CO binding to BdLYR2-ECR. 20 nM of BdLYR2-ECR were incubated with a range of LCO-V(C18:1,NMe,S), CO4, CO5 or CO7. The plots show the fraction bound (mean ΔFnorm values divided by the curve amplitude), from 2 independent experiments. Plots showing the binding amplitudes (ΔFnorm) are in Supplementary Fig. 5. d Affinity of BdLYR2-ECR for LCO and CO, deduced from the binding curves. e Curves of LCO and CO binding to BdLYR1-ECR. 20 nM of BdLYR1-ECR were incubated with a range of LCO-V(C18:1,NMe,S), CO4, CO5 or CO7. Plots with binding amplitudes are shown in Supplementary Fig. 5. f Affinity of BdLYR1-ECR for LCO and CO, deduced from the binding curves. Note that since the curves of LCO binding are not saturated, the Kd might be overestimated. g Schematic representation molecules used for MST: fluorescent CO5-BODIPY and unlabeled ECR. h Curves of BdLYR1-ECR and BdLYR2-ECR binding to CO5. 100 nM of CO5-BODIPY were incubated with a range of BdLYR1-ECR or BdLYR2-ECR. Because CO5-BODIPY fluorescence changed upon binding to ECRs, fluorescence intensity rather than thermophoresis was analysed. The plots show the fraction bound (fluorescence intensity values divided by the curve amplitude), (f). Affinity of BdLYR1-ECR and BdLYR2-ECR for CO5, deduced from the binding curves. Note that since the curves for BdLYR1-ECR in (h) are not saturated, the Kd might be overestimated.

LYR-IB proteins have conserved biochemical properties in other plants species

We found high affinity of the M. truncatula MtLYR8 for LCO (Kd of 12.3 nM ± 0.3 nM, n = 2) and short-chain CO (Kd of about 25 nM) and complete competition of LCO binding using 2 µM CO4 or CO8 (Supplementary Fig. 6a–d). Similarly, in the hexaploid wheat, the three LYR-IB proteins TaLYR2A, TaLYR2B and TaLYR2D showed LCO binding and complete competition of LCO binding using 2 µM CO4 or CO8 (Supplementary Fig. 6e, f). We then characterized in more detail TaLYR2D and found high affinity for LCO (Kd of 1.5 nM ± 0.4 nM, n = 2) and short-chain CO (Kd of about 25 nM) (Supplementary Figs. 6g–i).

In summary, we found high affinity for short-chain CO only for members of the LYR-IB group and not for members of the LYR-IA, LYR-IIIC and LYM-II groups, which respectively have predominantly high affinity for LCO (LYR-IA)14,15,16 and long-chain CO (LYR-IIIC and LYM-II)8,9,10,11,12.

LYR-IB LysM-RLKs are involved in AM establishment in Petunia hybrida and Brachypodium distachyon

We identified a KO line in the P. hybrida LYR-IB gene (Phlyk9-1, Fig. 4a). Phlyk9-1 homozygous plants displayed a reduced number of AMF colonization sites at early stages of colonization (Fig. 4b) and a reduced root length colonization by AMF at later stages (Fig. 4c, Supplementary Fig. 7a), compared to segregating plants with the wild type (WT) PhLYK9 allele. No obvious differences in arbuscule shape were found between plants bearing WT or Phlyk9-1 alleles (Supplementary Fig. 7b). We also produced a CRISPR/Cas9 KO line in the LYR-IB gene of a closely related species, tomato (Sllyk9-1, Supplementary Fig. 7c, d). A reduced colonization by AMF was also observed in this line with no obvious differences in arbuscule shape (Supplementary Fig. 7e, f). A KO line in the P. hybrida LYR-IA gene (Phlyk10-1) also showed a decrease in AMF colonization in Girardin et al.17. We thus crossed Phlyk9-1 and Phlyk10-1 to test potential redundancy between the genes. We observed a reduced AMF colonization in the double mutant compared to the single Phlyk9-1 mutant (Fig. 4d).

a Position of the dTPh1 transposon insertion in Phlyk9-1. b Number of AMF colonization sites per root system at 3 wpi in segregating plants bearing homozygous Phlyk9-1 or WT PhLYK9 (control) alleles. n = biologically independent plants examined over two independent experiments. c Detailed analysis of AMF structures at 6 wpi in segregating plants bearing homozygous Phlyk9-1 or WT PhLYK9 alleles. n = biologically independent plants examined over two independent experiments. d Root-length colonization at 4 wpi in segregating plants bearing homozygous Phlyk9-1 and Phlyk10-1, Phlyk9-1 and WT PhLYK10 (Phlyk9-1) or WT PhLYK9 and PhLYK10 (control) alleles after the cross of Phlyk9-1 and Phlyk10-1 lines. n = biologically independent plants examined over three independent experiments. e Positions of the nonsense mutations in Bdlyr1-1 and Bdlyr2-1. f Detailed analysis of AMF structures at 4 wpi in segregating plants bearing homozygous Bdlyr1-1 or WT BdLYR1 (BdLYR1 Seg WT), Bdlyr2-1 or WT BdLYR2 (BdLYR2 Seg WT), or Bdlyr1-1 and Bdlyr2-1 (Bdlyr1-1*Bdlyr2-1). n = biologically independent plants examined over two independent experiments. g Number of AMF colonization sites per root system at 3 wpi in segregating plants bearing homozygous Bdlyr2-1 and Bdlyr1-1 (Bdlyr1-1*Bdlyr2-1) or WT BdLYR2 and BdLYR1 (Seg WT) alleles. n = number of biologically independent plants examined over two independent experiments. The box edges represent the 0.25 and 0.75 quantiles, the center line indicates the median value, and the whiskers show the range from the minimum to the maximum values, excluding the outliers in (b–d, f, g). Statistical differences (p < 0.05) were calculated using a Wilcoxon test in (b, g), a pairwise two-sided Student’s t-test in (c, d) and a Van der Waerden test in (f) (for each structure category).

We also identified KO lines in the B. distachyon LYR-IA and LYR-IB genes (Bdlyr1-1 and Bdlyr2-1, respectively, Fig. 4e). In contrast to Phlyk10-1 and Phlyk9-1, neither Bdlyr1-1 nor Bdlyr2-1 homozygous plants showed differences in root length colonization by AMF (Fig. 4f) compared to their segregating WT plants. However, the Bdlyr1-1/Bdlyr2-1 double mutant showed a reduced number of AMF colonization sites at early stages of colonization (Fig. 4g) and a strong decrease in root length colonization by AMF at later stages (Fig. 4f), as found for Phlyk10-1/Phlyk9-1. Arbuscule branching may also be reduced in the Bdlyr1-1/Bdlyr2-1 double mutant compared to WT plants (Supplementary Fig. 8a), but this would require further investigation to be quantified. Finally, we measured the expression of a fungal housekeeping gene and plant AM-induced genes by qRT-PCR. The level of the fungal gene was significantly reduced (Supplementary Fig. 8b), supporting the AM phenotype observed by microscopy. In contrast, the level of expression of the plant AM-induced genes was either not affected or only slightly, suggesting that their expression is either not fully correlated with the level of AMF colonization or is increased in colonized root areas as a compensation mechanism.

The M. truncatula LYR-IB LysM-RLK controls AM and LCO and short-chain CO responses but not nodulation and Nod-LCO responses

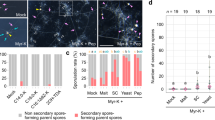

We used the legume M. truncatula to analyse the role of the LYR-IB gene in both AM and nodulation and in activation of root-epidermal calcium responses to LCO and short-chain CO, which have been well characterized in this species4,5. Two KO lines (Mtlyr8-1 and Mtlyr8-2) were produced by CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing and A. tumefaciens transformation (Fig. 5a, Supplementary Fig. 9a, b). A reduced number of AMF colonization sites at early stages of colonization and a reduced root length colonization at later stages were found in the two lines compared to WT plants (Fig. 5b, c; Supplementary Fig. 9c), but no obvious differences in arbuscule shape were observed (Supplementary Fig. 9d). qRT-PCR experiments also showed an average decrease of M. truncatula AM-induced gene expression, but only the level of the fungal gene was significantly reduced (Supplementary Fig. 9e).

a Position of the frameshift deletions in Mtlyr8-1 and Mtlyr8-2. Details are shown in Supplementary Fig. 9b. b Number of AMF colonization sites per root system at 3 wpi in Mtlyr8-1, Mtlyr8-2, 2HA (WT) or a 2HA line transformed with an empty vector (WTL) alleles. n = biologically independent plants examined over two independent experiments. c Detailed analysis of AMF structures at 4 wpi in Mtlyr8-1, Mtlyr8-2, WT or WTL. n = biologically independent plants examined over two independent experiments. d Number and proportion of root atrichoblast cell nuclei showing calcium spiking to all fluorescent nuclei analysed following treatment with 10-7 M CO4 or LCO-V (C18:1,NMe,S). Data are the sum from at least 3 independent plants. Only nuclei with two or more spikes in 20 min were considered as responding cells. e Root-length colonization at 32 dpi in wheat plants expressing BdLYR2 under the control of a strong promoter (pUbi:BdLYR2) or containing the empty vector (Control). n = biologically independent plants from two independent transgenic lines for each construct. f Relative expression of the R. irregularis gene RiGAPDH (reflecting the amount of fungus in the roots), the early AM stage marker genes TaAM3 and the ammonium and phosphate transporters specifically expressed in arbuscule-containing cells (SymAMT2 and symPT respectively) in pUbi:BdLYR2 and control plants at 6 wpi. n = 3 pools of roots from two independent transgenic lines for each construct. g Effect of LCO and CO on root-length colonization in wheat plants expressing BdLYR2 under the control of a strong promoter (pUbi:BdLYR2) or containing the empty vector (Control). Plants were treated with 10-7 M CO4 or LCO-V(C18:1,NMe,S). n = biologically independent plants from two independent transgenic lines for each construct examined over two independent experiments (harvested at 5 or 6 wpi). Relative colonization levels to mean colonization in non-treated control plants in each experiment. h Effect of pUbi:BdLYR2 on root architecture. n = biologically independent plants from two independent transgenic lines for each construct. The box edges represent the 0.25 and 0.75 quantiles, the center line indicates the median value, and the whiskers show the range from the minimum to the maximum values, excluding the outliers in b-c and e-h. Statistical differences (p < 0.05) were calculated using a Van der Waerden test in (b, c) (for each structure category), a Chi-square test in (d), a two-sided Student’s t-test in (e, f) a Kruskal Wallis test in (g) and a Wilcoxon test in (h).

We then used Agrobacterium rhizogenes transformation to introduce the calcium concentration GECO reporter and measured calcium spiking responses in root atrichoblasts following CO4 or LCO treatments. The LCO used (LCO-V(C18:1,NMe,S) as for the ligand binding assays, has a structure different from those produced by Sinorhizobium meliloti (LCO-IV(C16:2,Ac,S)), and thus is expected to produce responses more related to AM than nodulation. Both LCO and short-chain CO induced calcium spiking were strongly reduced in the transgenic roots of the two KO lines compared to the controls (Fig. 5d, Supplementary Fig. 9f), thus clearly showing a role of the LYR-IB receptor in symbiotic LCO and short-chain CO responses.

In contrast, both mutant lines nodulated at least as well as WT with both the WT M. truncatula Rhizobial partner S. meliloti and the nodFE strain (Supplementary Fig. 10a, b), the latter of which produces LCO more similar to the ligand used for binding. Similarly, no differences were observed in the induction level of Rhizobial LCO-responsive genes in the mutant lines compared to WT plants (Supplementary Fig. 10c).

Strong expression of a LYR-IB gene increases AMF colonization in wheat

Since we showed that LYR-IB proteins are involved in symbiotic signal perception and AM establishment, we tested whether expression under the control of a strong constitutive promoter could increase colonization by AMF. We chose Triticum aestivum, as a major crop, for these experiments. We produced transgenic wheat lines expressing BdLYR2 under the control of a strong promoter, leading to a high expression of BdLYR2 with no impact on the level of endogenous TaLYR2 genes (Supplementary Fig. 11a). We found an increase in root colonization by AMF of transgenic plants compared to controls when the colonization level was low (Fig. 5e), but this effect was not observed at higher levels of colonization (Supplementary Fig. 11b). Using molecular markers to quantify AMF colonization, we found a significant increase in the transcript level of the AMF housekeeping gene and a wheat AM marker gene (Supplementary Fig. 11c), in transgenic plants compared to controls (Fig. 5f). However, although their expression was increased, the transcript levels of two transporters specifically expressed in arbuscule-containing cells were not significantly different in transgenic plants compared to controls (Fig. 5f). To further characterize the transgenic plants, we quantified the stimulation of AMF colonization by LCO and CO4 treatments. Treatment with 10−7 M CO4, but not 10−7 M LCO, increased AMF colonization in the control plants. In contrast to the control plants, treatment with 10−7 M LCO was able to increase AMF colonization in the transgenic plants while no further increase was seen compared to control plants with CO4 (Fig. 5g).

Finally, as LysM-RLKs are known to control root development in response to chitinic signals22, we measured root architecture in the transgenic wheat plants grown in axenic conditions, and found that both total root length and number of lateral roots were reduced, in comparison to the control plants (Fig. 5h).

Atypical evolution of the LYR-IB gene in rice

LYR-IB genes were found in all angiosperm species we looked at (Supplementary Fig. 1)8 and had conserved biochemical properties and roles in AM establishment in the species we have studied. However, we found the full coding sequence of the LYR-IB gene in indica rice genomes but not in the two japonica reference genomes, Nipponbare and Kitaake. In these two genomes, there is a one bp deletion in the first exon that creates a frameshift (Fig. 6a), leading to a predicted protein truncated just before the TM. Such a protein would not anchor to the PM, and thus is probably mislocalised and likely non-functional in signal transduction. To determine whether this deletion was specific to these two japonica cultivars, we sequenced an amplicon covering the deletion in 15 japonica and 26 indica cultivars (Supplementary Fig. 12). The deletion was absent in all indica cultivars. In contrast the deletion was present in most japonica cultivars. We verified that the full-length LYR-IB protein from the indica cultivar Xihui18 (OsLYK11) has similar biochemical properties to the other LYR-IB proteins. We found that OsLYK11-YFP, produced in N. benthamiana leaves, has high affinity for both LCO (Kd of 4.7 nM ± 1.7 nM, n = 2) and short-chain CO (Kd of about 25 nM) (Fig. 6b–d). Using 10 nM CO5-biot, binding was detected for OsLYK11 but not for the LYR-IA OsNFR5/OsMYR1 (Fig. 6e). Binding to the later was only found at higher CO5-biot concentrations (Supplementary Fig. 13a). A CRISPR/Cas9 Xihui18 KO line for OsLYK11 (Oslyk11-1, Fig. 6f, Supplementary Fig. 13b, c) showed no difference in root colonization by AMF compared to WT plants (Fig. 6g). Since japonica cultivars are natural OsLYK11 mutants, we introduced the indica Xihui18 OsLYK11 gene under the control of its own promoter in Kitaake and Nipponbare and quantified AMF colonization. Again, no differences were found between the control plants and those containing the indica OsLYK11 allele (Fig. 6h, Supplementary Fig. 13d).

a Partial sequence alignment of OsLYK11 from the indica rice cultivar Xihui18 and the japonica rice cultivars Nipponbare and Kitaake, showing the natural 1 bp deletion in the japonica cultivars. b Image of epidermal cells from a N. benthamiana leaf expressing Xihui18 OsLYK11-YFP (OsLYK11). Scale bar represents 20 µm. c Affinity of OsLYK11 for LCO-V(C18:1,NMe,S). Scatchard plot of a cold saturation experiment using membrane fractions containing OsLYK11 and a range of LCO-V(C18:1,NMe,S) concentrations as competitor. The plot is representative of experiments performed with two independent batches of membrane fractions. d Affinity of OsLYK11 for short-chain CO. Saturation experiments on 10 µg of membrane proteins containing OsLYK11 using a range of concentrations of CO5-biot. WB performed using sequentially anti-GFP antibodies and streptavidin on the same membrane. The arrowhead indicates the position of OsLYK11-YFP, whereas * indicates an N. benthamiana endogenously biotinylated protein. e CO5-biot binding to 10 µg of N. benthamiana membrane proteins containing OsLYK11 or OSNFR5/OsMYR1. f Position of the frameshift insertion in Xihui18 Oslyk11-1. Details are shown in Supplementary Fig. 13b. g Detailed analysis of AMF structures at 5 wpi in Oslyk11-1 or WT Xihui18 plants. n = biologically independent plants examined over two independent experiments. h Detailed analysis of AMF structures at 5 wpi in Nipponbare or Kitaake plants WT, containing the empty vector (WTL) or containing Xihui18 OsLYK11. n = biologically independent plants from two independent transgenic lines and one WT line from one experiment. A second replicate is shown in Supplementary Fig. 13c. The box edges represent the 0.25 and 0.75 quantiles, the center line indicates the median value, and the whiskers show the range from the minimum to the maximum values, excluding the outliers in (g, h). Statistical differences (p < 0.05) were calculated using a Van der Waerden test in (g, h) (for each structure category).

Discussion

Short-chain CO are important signaling molecules produced by AMF that elicit symbiotic responses at nM concentrations. By characterizing members of the LYR-IB phylogenetic group in P. hybrida, M. truncatula, B. distachyon, rice and wheat, we have identified a group of LysM-RLKs which show high affinity for short-chain CO, in addition to LCO and longer CO. Among the LysM-RLK groups characterized to date, the LYR-IB group appears as the only one to have conserved high affinity for short-chain CO. In comparison, LysM-RLPs of the LYM-II group and LysM-RLKs of the LYR-IIIC group, have high affinity for long-chain, but not for short-chain CO (this work and11,12,14,23,24).The rice LYR-IA OsNFR5/OsMYR1 ECR was described to have different degree of affinity (from nM to µM ranges) for short-chain CO20,25, but we found lower affinity for short-chain CO in this protein than in LYR-IB proteins, when expressed as full-length proteins. The LYR-IA LjLYS11 ECR was also found to have affinity for CO5 and LCO (µM range), but we also found higher affinity for LCO than CO for the full-length ortholog in M. truncatula, MtLYR114. This illustrates the difficulty of comparing protein affinity when different protein production systems and ligand binding assays are used.

Indeed, we compared several expression systems and ligand binding assays. We found similar affinities (nM range) with the two ligand binding assays (radiolabelled LCO or crosslinkable CO5) when we used full-length proteins produced in N. benthamiana leaves, but much lower affinities (µM range) when we used the ECRs expressed in insect cells combined with MST. Low affinity (µM range) was also found for OsCEBIP ECR produced in insect cells13 while binding assays on the full-length proteins showed high affinity (nM range)23, coherent with characterized endogenous high affinity (nM range) binding sites26. The discrepancy between the data we obtained with ECRs and full-length proteins might result from the ability of full-length proteins to form homo-oligomers (or hetero-oligomers with N. benthamiana endogenous proteins) leading to increased affinity for the ligand. Despite the discrepancy in affinity, selectivity for the ligand was conserved between the two expression systems tested, and confirmed the ability of LYR-IB proteins to bind both short-chain CO and LCO. It however highlights the caution required to compare data from the literature obtained with various expression systems/ligand binding assays.

The biochemical properties we found for full-length LYR-IB proteins are coherent with an endogenous short-chain CO binding site described in a tomato cell culture and derived membrane fraction using a radiolabelled CO527. In the membrane fractions, this site had a Kd of 22.8 nM for their modified CO5 and did not discriminate CO4, CO5 and a LCO-V(C18:1,Ac). These characteristics were consistent with the concentration of CO4 and CO5 inducing biological activities28 suggesting that it is the major short-chain CO binding site in the tomato cell culture. The function of LYR-IB proteins as major high-affinity short-chain CO and LCO receptors is further shown by the large decrease in short-chain CO and LCO signaling (decrease in calcium spiking) we measured in roots of M. truncatula Mtlyr8 and that has also been found in the barley LYR-IB mutant, Hvrlk2 6.

The low selectivity between CO4/5, CO8, and LCO of LYR-IB raises the question of which structure is recognized by the proteins. It is possible that the binding pocket accommodates 4 GlcNAc that are sufficient for high-affinity binding, and that additional GlcNAc (in longer chain CO) or an acyl chain (in LCO) do not or weakly interfere with the binding affinity.

Various chitinic molecules including short-chain CO and LCO can induce lateral root formation in various plant species including in dicots and monocots22,29,30. This phenomenon was shown to rely on LYR-IA, LYM-II, and LYK-I LysM-RLKs and at least a part of the CSSP22,29. The impact on wheat root architecture of ectopic BdLYR2 expression under a strong promoter, further supports the role of LysM-RLKs in root developmental processes and extends it to the LYR-IB LysM-RLKs. Strong expression of LysM-RLKs might induce signaling in the absence of a ligand, as observed with spontaneous nodulation in legumes17,31 or activation of cell death in N. benthamiana32,33.

We previously showed that Solanaceae (petunia and tomato) mutants in LYR-IA high-affinity LCO receptors have a decreased colonization by AMF. Here, we show that Solanaceae (petunia and tomato) and Fabaceae (M. truncatula) mutants in LYR-IB high affinity CO/LCO receptors also have a decrease in colonization by AMF, and that in petunia the double mutant has a more severe AM phenotype than the single LYR-IB mutant. In B. distachyon (this study) and in barley6, single LYR-IA and LYR-IB mutants do not have AM phenotypes, and only double mutants have severe phenotypes, as in the petunia double mutant, suggesting different levels of LYR-IA and LYR-IB redundancy in monocots compared to dicots. Interestingly both LYR-IA and LYR-IB gene expression were under the control of nitrogen and phosphate deficiency in barley, but not in M. truncatula6. However, in M. truncatula, LYR-IB appears to have retained an ancestral role in AM, and has not evolved a dual role in nodulation with rhizobial bacteria as LYR-IA, which is consistent with poor LYR-IB protein binding to S. meliloti LCO14 compared to the LCO used here.

Because of the absence of a functional LYR-IB gene in the rice cultivar Nipponbare, the AM phenotype found in LYR-IA mutants20 might thus be equivalent to the LYR-IA/LYR-IB double mutants in other Poaceae. However, it should be noted that the AM phenotype of the rice LYR-IA mutants is variable depending on the authors20,22,34. Absence the LYR-IB gene in Nipponbare may also explain the altered short-chain CO responses20 in the LYR-IA gene mutants whereas this was not observed in single mutants of the LYR-IA gene in barley6 and tomato21. We found by knocking out the LYR-IB gene in the indica Xihui18 cultivar and by complementing the natural LYR-IB gene KO in the japonica Nipponbare and Kitaake cultivars, that a single LYR-IB mutant in rice has no AM phenotype, as in other Poaceae. The deletion in the LYR-IB gene in most japonica rice is reminiscent of the situation with OsCERK1 (a LysM-RLK belonging the LYK-I group), for which haplotypes from japonica cultivars show lower efficacy for AM establishment than those from indica cultivars35 suggesting different selection pressures on AM related genes in domestication/breeding of indica and japonica rice.

In conclusion, this work has identified that the LYR-IB LysM-RLKs directly bind short-chain CO and LCO signals and play an important role in signaling and AM establishment.

Methods

Mutant lines

The Phlyk9-1 mutant allele (line LY3182, dTph1 insertion 718 bp from the start codon, W118 genotype) was identified by BLAST search in a Petunia dTPh1 transposon flanking sequence database36 with the full PhLYK19 coding sequence. Phlyk10-1 is described in ref. 17. Progeny genotyping was performed by PCR using the primers listed in Supplementary Data 1.

Induced mutations in Bdlyr1-1 (line 5525) and Bdlyr2-1 (line 5160) were isolated from an sodium azide-mutant population of Brachypodium distachyon Bd21-3 genotype as described37 on the EPITRANS platform38. The mutation detection system used in TILLING is based on NGS sequencing of libraries of PCR fragments, labeled with unique sequences and amplified from pooled samples in several dimensions39. The mutant lines are then identified using the SENTINEL software40.

Progeny genotyping was performed by dCAPS (endogenous HaeIII restriction site (BdLYR1) or site created with the primer (BdLYR2) lost in the mutant alleles) and confirmed by PCR amplicon sequencing with the primers listed in Supplementary Data 1.

Sllyk9-1 was produced by A. tumefaciens transformation of the Ailsa Craig cultivar by CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing using the vector described in ref. 41 and a protospacer described in Supplementary Fig. 7. T2 plants were phenotyped.

Mtlyr8-1 and Mtlyr8-2 are independent lines produced by CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing via A. tumefaciens transformation of the 2HA genotype, using a protospacer described in Supplementary Fig. 9. A transformed non-edited line that segregated out the T-DNA was selected as control (WTL). T1 plants were phenotyped in Fig. 5 and T2 plants in Supplementary Fig. 9.

OsLyk11-1 was produced by CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing via A. tumefaciens transformation of the Xihui18 cultivar with the vector described in ref. 41 and a protospacer described in Supplementary Fig. 13. T1 plants were phenotyped.

Transgenic lines

The rice Nipponbare and Kitaake cultivars were transformed by A. tumefaciens containing the plasmid PTCK303 in which a synthesized DNA fragment with the Xihui18 pOsLYK11:OsLYK11 sequence modified to remove the restriction sites (sequence in Supplementary Data 2) was cloned between the HindIII and BstEII sites and a codon usage optimized NLS-gGECO (sequence in Supplementary Data 2) was cloned under the control of pZmUBI between the KpnI and SacI sites. Lines transformed with the same vector containing only the pZmUBI:NLS-gGECO were used as control. T1 plants were phenotyped.

The wheat Fielder cultivar was transformed by A. tumefaciens carrying the plasmid pBIOS12366 containing the following cassette: pZmUBI:BdLYR2-cmyc, pZmUBI:NLS-gGECO, and pBradi1g20260:GUS (sequences in Supplementary Data 2). Lines transformed with the plasmid pBIOS11613 containing only the pZmUBI:NLS-gGECO and pBradi1g20260:GUS (introduced as reporters for LCO and CO perception) were used as control. Note that the reporters were not detected either in absence or presence of LCO or CO. T0 lines with a single T-DNA insertion were selected by qPCR. T2 plants were phenotyped.

The NLS-gGECO and DsRed constructs42 were introduced by A. rhizogenes in roots of the M. truncatula 2HA lines described above.

In planta expression

For PhLYK9, BdLYR2, TaLYR2A, TaLYR2B, TaLYR2D and BdLYR3 we cloned the coding sequences optimized with N. benthamiana codon usage (sequences in Supplementary Data 2) by gene synthesis, in translational fusion with the sequence coding YFP under the control of Pro35S in pCambia 2200 vector modified for Golden gate cloning43. BdLYR4 was amplified by PCR from genomic DNA (primers listed in Supplementary Data 1) and cloned in translational fusion with the sequences coding YFP under the control of Pro35S in pbin vector modified for gateway cloning44.

We also first cloned PhLYK15, MtLYR8, OsLYK11 as described above (gene synthesis except for PhLYK15 which was amplified by PCR from genomic DNA with primers listed in Supplementary Data 1) but because their expression levels were too low or the proteins were mislocalised, the sequences encoding their ECR were amplified by PCR (primers listed in Supplementary Data 1) and cloned in translational fusion with the sequences coding with the MtNFP TM and ICR, and YFP under the control of Pro35S as described in ref. 43. We previously demonstrated that such chimeras have similar biochemical properties as the full-length proteins14,17,43.

In order to have a tagged OsCEBIP and BdLYM2, the sequence encoding its ECR (optimized sequences in Supplementary Data 2) was also cloned in translational fusion with sequences coding MtNFP TM and ICR, and YFP-HaloTag as described above. Cloning of OsNFR5/OsMYR1, BdLYR1 and MtLYR4 is described in ref. 14.

Leaves of N. benthamiana were infiltrated with the A. tumefaciens LBA4404 virGN54D strains. Leaves were harvested 3 days after infiltration.

Insect cell expression

Synthetic DNA fragments containing coding sequence of the hemolin signal peptide, BdLYR2-ECR or BdLYR1-ECR without signal peptides, 3HA tag, PreScission protease cleavage site and 6HIS tag in translational fusion (sequences in Supplementary Data 2) were cloned in the pGTPb302 plasmid.

BdLYR1 was expressed in High Five cells at 27 °C for 72 h (250 ml of cells (1.106 c/ml) infected with 0.536 µl of baculovirus (1.4 × 109 qpfu/ml)). BdLYR2 was expressed in Sf9 cells at 27 °C for 48 h (250 ml of cells (1.5 × 106 c/ml) infected with 0.625 µl of baculovirus (3.94 × 109 qpfu/ml).

AM phenotyping

Petunia seeds were germinated in sterilized potting soil for 10 days at 21 °C. Tomato seeds were surface-sterilized with 3.2% bleach for 20 min and germinated in vitro for 10 days at 25 °C. Medicago seeds were scarified with sand paper, surface-sterilized with 3.2% bleach for 3 min and germinated in vitro for 5 days at 4 °C and overnight at 25 °C. Rice seeds were surface-sterilized with 70% ethanol for 1 min and 1% bleach for 30 min and germinated in vitro for 4 days at 37 °C. Brachypodium seeds were surface-sterilized with 70% ethanol for 30 s and 2.5% bleach for 20 min and germinated in vitro for 1 week at 4 °C and 3 days at 25 °C. Wheat seeds were surface-sterilized in 70% ethanol for 10 min and 3.2% bleach for 20 min and germinated in vitro for 1 week at 4 °C and 3 days at 25 °C.

Seedlings were transferred into 50 ml of Attapulgite Oil-Dri UK and inoculated with the following number of spores/plant of R. irregularis DAOM 197198 (Medicago: 200; petunia, tomato, Brachypodium and wheat: 500; rice: 1000 and half the spore concentration per plant for Medicago and Brachypodium to estimate the number of AMF colonization sites at the early stages) and watered with 0.5x modified Long Ashton medium (containing 7.5 µM NaH2PO4 for all experiments except qRT-PCR of Brachypodium, where 200 µM NaH2PO4 was used). For experiments including symbiotic signals, stock solutions of 10-4 M CO4 or LCO-V(C18:1,NMe,S) were made in water or 50% acetonitrile respectively. For treatments, 20 ml of 0.5x modified Long Ashton medium supplemented with 10-7 M LCO, 10-7 M CO4 + 0.05% acetonitrile or 0.05% acetonitrile (control) were added to the dry substrate at the beginning of the experiments and 10 ml were added twice 2 weeks and 4 weeks later. After harvest, for microscopy analysis, individual root systems were stained in a 5% ink–vinegar solution after 10% (w/v) KOH treatment or with 0.2 M PBS pH 7.2, Triton X-100 0.01%, 0.2 μg/mL WGA-Alexa488 (ThermoFisher) after 100% ethanol for 4 h and 10% KOH for 3 days at room temperature; and for qRT-PCR, pools of 4 root systems were frozen in liquid-nitrogen.

Nodulation phenotyping

Nodule numbers were counted in individual plants grown in tubes on Fahraeus agar slants supplemented with 0.2 mM NH4NO3 at 28 dpi using 0.5 ml/tube of 0D600 = 0.00025 (about 1 × 105 cfu) of S. meliloti strains 2011 (GMI 6526) and its nodFE mutant (GMI 6528), containing a constitutive pHemA:LacZ fusion.

In vitro culture

For responses to Nod–LCO, M. truncatula plants were grown vertically on 12 × 12 cm plates containing M medium solidified with 4% phytagel for 12 days. A 10−8M Nod-LCO solution was prepared from a 10−4M stock solution (50% acetonitrile) and 100 μl were applied on 1.5 cm of roots from the tips. Treated root fragments were cut after 6 h and frozen in liquid-nitrogen. For calcium spiking measurements in tomato, plantlets were grown on agar supplemented with 25 mg/l kanamycin for 6 weeks. About 2-cm-long root pieces corresponding to the middle parts of the secondary roots were cut and placed between glass slides. They were then treated with the indicated molecules for 30 min before analysis. For calcium spiking measurements in M. truncatula, composite plants were produced by wounding seedlings grown on Farhaeus agar plates at the hypocotyl-root junction and coculturing them with Agrobacterium rhizogenes Arqua1 carrying the same G-GECO-DsRed construct as introduced in tomato. At 2 weeks after, plantlets were transferred to 12 × 12 cm agar plates and grown for 3 weeks at 25 °C.

Calcium spiking measurement

gGECO and DsRed were respectively excited with the 488 nm or the 561 nm argon laser lines, and fluorescent emission (500 to 550 nm or 570 to 650 nm) were imaged for 20 min on a SP8 confocal laser-scanning microscope (Leica) with a fluostar VISIR 25x/0.95 WATER objective. All nuclei in the focal plan were selected as regions of interest using the LAS X software V3.3 and the fluorescence intensities in each region of interest were exported. Total number of cells with visible gGECO basal fluorescence and the number of cells with nuclei spiking more than once were used to calculate the percentage of cells with spiking nuclei.

Root architecture measurement

Plantlets were grown in 20 × 20 cm plates containing Fahraeus agar medium for 2 weeks at 25 °C and root systems were scanned using Expression 10000XL scanner (Epson). Total root length was estimated by using WINRhizo software v2007d and the number of lateral roots was counted manually on the images.

Protein purification from insect cells

The cells were centrifuged at 2000 × g for 20 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was diluted to half with 40 mM BisTris pH 6.8 and loaded onto HiPrep™ Q FF 16/10 anion exchange chromatography column (GE healthcare), washed with 20 mM BisTris pH 6.8 − 100 mM NaCl.

The bound proteins were eluted with 20 mM BisTris pH 6.8, 500 mM NaCl and further purified on histidine-tagged protein columns. HisTrap FF Crude (Cytiva) was used for BdLYR1 that was eluted in 20 mM Na phosphate pH 8, 500 mM NaCl, 40 mM imidazole and HiTrap Excel (GE healthcare) was used for BdLYR2 that was eluted in 50 mM Na phosphate pH8, 300 mM NaCl, 40 mM imidazole.

The purified proteins were concentrated with a Vivaspin 20 PES membrane unit with a 10 kDa cut off, and buffer was exchanged with 50 mM Tris pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, using a spin column A buffer exchange (Monolith NT Protein Labeling Kit RED-NHS) before storage at −80 °C.

Preparation of membrane fractions from N. benthamiana leaves

Approximately 20 g of leaves were homogenized in a blender at 4 °C in the presence of 40 ml of extraction buffer (25 mM Tris, pH 8.5, 0.47 M sucrose, 5 mM EDTA, 10 mM DTT, 0.6% PVPP and protease inhibitors (0.1 mM AEBSF, and 1 mg/ml each of leupeptin, aprotinin, antipain, chymostatin, and pepstatin). The samples were centrifuged for 15 min at 3000 x g, and the resulting supernatant was centrifuged for 30 min at 45,000 x g. The pellet (membrane fraction) was first washed in 5 ml and then resuspended in 2 ml of binding buffer (25 mM NaCacodylate pH 6, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM CaCl2, 250 mM sucrose and protease inhibitors). After each extraction, the amount of fusion proteins was quantified by immunoblotting in 10 µg of membrane fraction proteins.

Radiolabelled LCO and CO-biot binding assays

LCO-V(C18:1,NMe,S) were purified from the rhizobial strain Rhizobium tropici. CO4, CO5, CO7 and CO8 were prepared in ref. 45. Labeling of LCO-V(C18:1,NMe) with 35S was performed by enzymatic sulfation of non-sulfated homologs using the sulfotransferase NodH and radioactive PAPS as sulfate donor. The non-sulfated fraction was then separated by HPLC46. The synthesis of CO7-biot is described in Supplementary Fig. 14, similarly to that of CO5-biot14.

Radiolabelled LCO binding to membrane fractions was performed for 1 h on ice in a total volume of 200 µl of binding buffer, in the presence or absence of the indicated competitors. The membrane fractions were then filtered through glass fiber filters (Filtermats, Skatron) using a Skatron Cell Harvester. Each filter disk was washed with 5 ml of 12.5 mM bis-tris pH 6, 1 mM MgCl2 and 1 mM CaCl2, transferred into scintillation vials, and the radioactivity was measured by scintillation spectrometry. Each LCO binding assay consisted of three technical replicates. Binding data were analysed using RADLIG software V4 (Biosoft). CO5-biot and CO7-biot binding to membrane fractions was performed in binding buffer for 1 h on ice. Samples were then centrifuged for 30 min at 31,000 × g and 4 °C and pellets were washed and resuspended in binding buffer. CO5-Biot binding to ECR was performed in the same buffer. Proteins were then purified using Ni-NTA Agarose beads (Qiagen, 30210). Proteins were then separated by SDS PAGE, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, and revealed using 1:7000 of anti-GFP antibodies (AMSBIO, TP401) or 1:5000 of anti-His-HRP antibodies (Sigma, A7058) and after membrane stripping by 1:10,000 streptavidin-HRP (Sigma, S2438), immunolabeling was detected by enhanced chemiluminescence and visualized with Image Lab software V6.1.0 (BIO-RAD). For protein purification, membrane fractions were resuspended after centrifugation by IP buffer (25 mM Tris pH7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, NaF protease inhibitors and phosphatase inhibitor). Proteins were then solubilised in IP buffer supplemented with 0.2% DDM for 1 h at 4 °C and centrifuged at 100,000 x;g and 4 °C for 15 min. Solubilised proteins in the supernatant were purified using GFP beads (ChromoTek, GFP-TrapMA).

Microscale thermophoresis

Binding experiments were performed with the Monolith NT.115 (Nano Temper Technologies). BdLYR2-ECR and BdLYR1-ECR were labeled with the His-Tag labeling Kit RED-tris-NTA 2nd Generation (Nano Temper Technologies) according to the manufacturer instructions, using a protein:dye ratio 2:1, in PBS buffer with Foscholine 0.175%.

For CO binding experiments, 40 nM of labeled proteins were mixed (1:1 volumes) with a range of CO serial dilutions in PBS buffer, Foscholine 0.175%, in PCR tubes, and incubated at room temperature for 10 min.

Due to the physico-chemical properties of the LCO, the above procedure was modified to avoid sticking problems and insertion into micelles. A range of LCO concentrations was prepared by serial dilution in 50% ethanol in PCR tubes. One µl of each LCO dilution was distributed in a low binding microtiter plate, 100 µl of 20 nM labeled proteins were immediately added and the mix was incubated at room temperature for 10 min.

For binding experiments with Fluorescent CO5, 100 nM of CO5-BODIPY (Supplementary Figs. 5i, 15) in MST buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.05% tween-20) were mixed (1:1 volumes) with a range of unlabeled protein serial dilutions in MST buffer in PCR tubes, and incubated at room temperature for 10 min.

Premium treated capillaries (NanoTemper Technologies, for LCO and CO5-BODIPY) and standard capillaries (NanoTemper Technologies, for CO) were loaded and the measurements were performed at 22 °C with 60% excitation power (CO5-BODIPY) or 100% excitation power (Labeled proteins) and medium MST power. Binding data were analysed using the MO.Affinity Analysis software V2.3 (Nano Temper Technologies).

qRT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated using a NucleoSpin® RNA Plant Mini kit (Macherey-Nagel) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The integrity and quantity of the RNA preparations were checked using Agilent RNA 6000 Nano Chips (Agilent Technologies). The first-strand cDNA synthesis was performed with the Prime Script RT Master Mix kit (TAKRR036A, Takara). Quantitative real-time PCR was performed at 60 °C using Takyon No ROX SYBR 2X MasterMix blue dTTP (UF-NSMT-B0701 Eurogentec) with the primers listed in Supplementary Data 1. Real-time PCR data were collected and analysed using CFX Maestro software V2.3, on a Bio-Rad CFX instrument, with the exception of Supplementary Figs. 11c, 11a and 5f, which were analysed using LightCycler 480 SW software V1.5.1 on a Roche LightCycler 480 II. Gene expression levels were calculated relative to the housekeeping genes listed in Supplementary Data 1. Technical duplicates were made for each biological replicate.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The authors declare that the main data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information files. Unique biological material is available from the authors upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Rich, M. K., Nouri, E., Courty, P. E. & Reinhardt, D. Diet of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi: bread and butter?. Trends Plant Sci. 22, 652–660 (2017).

Delaux, P. et al. Comparative phylogenomics uncovers the impact of symbiotic associations on host genome evolution. Plos Genet. 10, e1004487 (2014).

Maillet, F. et al. Fungal lipochitooligosaccharide symbiotic signals in arbuscular mycorrhiza. Nature 469, 58–63 (2011).

Genre, A. et al. Short-chain chitin oligomers from arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi trigger nuclear Ca2+ spiking in Medicago truncatula roots and their production is enhanced by strigolactone. N. Phytol. 198, 179–189 (2013).

Feng, F. et al. A combination of chitooligosaccharide and lipochitooligosaccharide recognition promotes arbuscular mycorrhizal associations in Medicago truncatula. Nat. Commun. 10, 5047 (2019).

Li, X. R. et al. Nutrient regulation of lipochitooligosaccharide recognition in plants via NSP1 and NSP2. Nat. Commun. 13, 6421 (2022).

Volpe, V. et al. Long-lasting impact of chitooligosaccharide application on strigolactone biosynthesis and fungal accommodation promotes arbuscular mycorrhiza in Medicago truncatula. N. Phytol. 237, 2316–2331 (2023).

Buendia, L., Girardin, A., Wang, T., Cottret, L. & Lefebvre, B. LysM receptor-like kinase and LysM receptor-like protein families: an update on phylogeny and functional characterization. Front. Plant Sci. 9, 1531 (2018).

Zhang, J. et al. A receptor required for chitin perception facilitates arbuscular mycorrhizal associations and distinguishes root symbiosis from immunity. Curr. Biol. 34, 1705–1717.e6 (2024).

Kaku, H. et al. Plant cells recognize chitin fragments for defense signaling through a plasma membrane receptor. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 11086–11091 (2006).

Fliegmann, J. et al. Biochemical and phylogenetic analysis of CEBiP-like LysM domain-containing extracellular proteins in higher plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 49, 709–720 (2011).

Cao, Y. et al. The kinase LYK5 is a major chitin receptor in Arabidopsis and forms a chitin-induced complex with related kinase CERK1. Elife 3, e03766 (2014).

Liu, S. et al. Molecular mechanism for fungal cell wall recognition by rice chitin receptor OsCEBiP. Structure 24, 1192–1200 (2016).

Cullimore, J. et al. Evolution of Lipochitooligosaccharide Binding to a LysM-RLK for Nodulation in Medicago truncatula. Plant Cell Physiol. 64, 746–757 (2023).

Bouchiba, Y. et al. An integrated approach reveals how lipo-chitooligosaccharides interact with the lysin motif receptor-like kinase MtLYR3. Protein Sci. 31, e4327 (2022).

Broghammer, A. et al. Legume receptors perceive the rhizobial lipochitin oligosaccharide signal molecules by direct binding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 13859–13864 (2012).

Girardin, A. et al. LCO receptors involved in arbuscular mycorrhiza are functional for rhizobia perception in legumes. Curr. Biol. 29, 4249–4259 (2019).

Gysel, K. et al. Kinetic proofreading of lipochitooligosaccharides determines signal activation of symbiotic plant receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2111031118 (2021).

Wang, T. et al. LysM receptor-like kinases involved in immunity perceive lipo-chitooligosaccharides in mycotrophic plants. Plant Physiol. 192, 1435–1448 (2023).

He, J. et al. A LysM receptor heteromer mediates perception of arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiotic signal in rice. Mol. Plant 12, 1561–1576 (2019).

Ding, Y. et al. The LysM receptor-like kinase SlLYK10 controls lipochitooligosaccharide signaling in inner cell layers of tomato roots. Plant Cell Physiol. 65, 1149–1159 (2024).

Chiu, C. H., Roszak, P., Orvošová, M. & Paszkowski, U. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi induce lateral root development in angiosperms via a conserved set of MAMP receptors. Curr. Biol. 32, 4428–4437 (2022).

Shinya, T. et al. Functional characterization of CEBiP and CERK1 homologs in arabidopsis and rice reveals the presence of different chitin receptor systems in plants. Plant Cell Physiol. 53, 1696–706 (2012).

Shinya, T. et al. Characterization of receptor proteins using affinity cross-linking with biotinylated ligands. Plant Cell Physiol. 51, 262–270 (2010).

Xu, L., Wang, J., Xiao, Y., Han, Z. & Chai, J. Structural insight into chitin perception by chitin elicitor receptor kinase 1 of Oryza sativa. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 65, 235–248 (2023).

Shibuya, N., Kaku, H., Kuchitsu, K. & Maliarik, M. J. Identification of a novel high-affinity binding site for N-acetylchitooligosaccharide elicitor in the membrane fraction from suspension-cultured rice cells. FEBS Lett. 329, 75–78 (1993).

Baureithel, K., Felix, G. & Boller, T. Specific, high affinity binding of chitin fragments to tomato cells and membranes. Competitive inhibition of binding by derivatives of chitooligosaccharides and a Nod factor of Rhizobium. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 17931–17938 (1994).

Felix, G., Regenass, M. & Boller, T. Specific perception of subnanomolar concentrations of chitin fragments by tomato cells -induction of extracellular alkalinization, changes in protein-phosphorylation, and establishment of a refractory state. Plant J. 4, 307–316 (1993).

Olah, B., Briere, C., Becard, G., Denarie, J. & Gough, C. Nod factors and a diffusible factor from arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi stimulate lateral root formation in Medicago truncatula via the DMI1/DMI2 signalling pathway. Plant J. 44, 195–207 (2005).

Buendia, L. et al. Lipo-chitooligosaccharides promote lateral root formation and modify auxin homeostasis in Brachypodium distachyon. N. Phytol. 221, 2190–2202 (2019).

Ried, M.K., Antolín-Llovera, M. & Parniske, M. Spontaneous symbiotic reprogramming of plant roots triggered by receptor-like kinases. Elife 3, e03891(2014).

Pietraszewska-Bogiel, A. et al. Interaction of Medicago truncatula Lysin Motif Receptor-Like Kinases, NFP and LYK3, Produced in Nicotiana benthamiana Induces Defence- Like Responses. Plos ONE 8, e65055 (2013).

Madsen, E. B. et al. Autophosphorylation is essential for the in vivo function of the Lotus japonicus Nod factor receptor 1 and receptor-mediated signalling in cooperation with Nod factor receptor 5. Plant J. 65, 404–17 (2011).

Miyata, K. et al. Evaluation of the Role of the LysM Receptor-Like Kinase, OsNFR5/OsRLK2 for AM Symbiosis in Rice. Plant Cell Physiol. 57, 2283–2290 (2016).

Huang, R. et al. Natural variation at OsCERK1 regulates arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis in rice. N. Phytol. 225, 1762–1776 (2020).

Vandenbussche, M. et al. Generation of a 3D indexed Petunia insertion database for reverse genetics. Plant J. 54, 1105–14 (2008).

Dalmais, M. et al. A TILLING Platform for Functional Genomics in Brachypodium distachyon. PLoS ONE 8, e65503 (2013).

EpiTrans, EPIgenomics and TRANSlational Research Facility https://doi.org/10.15454/1.5572407597184844E12 (2018).

Magne, K. et al. Roles of BdUNICULME4 and BdLAXATUM-A in the non-domesticated grass Brachypodium distachyon. Plant J. 103, 645–659 (2020).

Rashid, D. et al. Ethylene produced in carpel primordia controls CmHB40 expression to inhibit stamen development. Nature Plants 9, 1675–1687 (2023).

Ma, X. & Liu, Y. G. CRISPR/Cas9-based multiplex genome editing in monocot and dicot plants. Curr. Protoc. Mol. Biol. 115, 31.6.1–31.6.21 (2016).

Cope, K. R. et al. The ectomycorrhizal fungus laccaria bicolor produces lipochitooligosaccharides and uses the common symbiosis pathway to colonize populus roots. Plant Cell 31, 2386–2410 (2019).

Fliegmann, J. et al. Lipo-chitooligosaccharidic symbiotic signals are recognized by LysM receptor-like kinase LYR3 in the legume medicago truncatula. ACS Chem. Biol. 8, 1900–1906 (2013).

Lefebvre, B. et al. A remorin protein interacts with symbiotic receptors and regulates bacterial infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 2343–2348 (2010).

Masselin, A. et al. Optimizing chitin depolymerization by lysozyme to long-chain oligosaccharides. Mar. Drugs 19, 320 (2021).

Gressent, F., Cullimore, J. V., Ranjeva, R. & Bono, J. J. Radiolabeling of lipo-chitooligosaccharides using the NodH sulfotransferase: a two-step enzymatic procedure. BMC Biochem. 5, 4 (2004).

Acknowledgements

We thank Fabienne Maillet (LIPME) for purification of rhizobial LCO, Sébastien Cabanac, Patrice Morel and Noémie Carles for technical help, and Sébastien Antelme for providing the Brachypodium seeds. We thank Clare Gough for critical reading of the manuscript. We thank Wu Xi Shu Guang Agricultural Science and Technology Development Co. Ltd. for a PhD fellowship for Yi Ding. This work was supported by the ANR projects “NICECROPS” (ANR-14-CE18-0008-01), “DUALITY” (ANR- 20-CE20-0017-01) and “WHEATSYM” (ANR-16-CE20-0025-01), the TULIP LABEX project “HOPES“, the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 32100241) and the Foundation for Innovative Research Groups of the Natural Science Foundation of Chongqing (Grant No. cstc2021jcyj-cxttx0004). This study is set within the framework of the “Laboratoires d’Excellences (LABEX)” TULIP (ANR-10-LABX-41), SPS (ANR-10-LABX-40-SPS) and of the “École Universitaire de Recherche (EUR)” TULIP-GS (ANR-18-EURE-0019). “La Fondation pour le développement de la Chimie des substances Naturelles et ses applications” is acknowledged for granting A.M. with a PhD scolarship. S.F. acknowledges ANR for partial support through LABEX ARCANE/CBH-EUR-GS (ANR-17-EURE-0003) as well as NanoBio ICMG (UAR 2607) for providing facilities for mass spectrometry (A. Durand, L. Fort, R. Gueret).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.B., J.J.B., J.C. and B.L. conceived and designed the experiments. Y.D., Z.L., V.G., A.L.F., M.G., L.M., A.R., C.V. and G.R. performed the experiments and analyzed the data. C.R., M.D., C.S., S.M., A.B., R.S., M.V., J.R., T.W., G.H., A.M., S.C. and S.F. provided materials. BL wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ding, Y., Lesterps, Z., Gasciolli, V. et al. Several groups of LysM-RLKs are involved in symbiotic signal perception and arbuscular mycorrhiza establishment. Nat Commun 16, 5999 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60717-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60717-1