Abstract

Ongoing cryospheric change has modified sediment export from glacierized catchments substantially, with significant implications for ecosystems and downstream users, notably hydropower companies. Sediment is exported either as finer sediment in suspension or as coarser bedload with intermittent contact between sediment and the bed. To date, the difficulty in observing subglacial bedload transport limits the understanding of the physical processes associated with evacuating bedload compared with suspended load. We elucidate the factors controlling sediment export by inverting a physically-based numerical model of subglacial sediment production and sediment transport with suspended sediment and continuous bedload discharge records from an Alpine glacier. Comparable quantities of suspended sediment and bedload are exported, and model results suggest that both rely on the availability of sediment for transport. Yet, bedload export in subglacial channels also depends on particular hydraulic conditions, notably channel shape and hydraulic roughness. This makes exporting bedload-sized particles inefficient compared to fine-grained sediment. As a result, subglacial hydraulics should be explicitly considered when examining bedload export processes, and suspended and bedload transport should be considered separately. Inefficient bedload evacuation by melt water implies that glacial erosion may only continue when non-fluvial mechanisms evacuate sediment, such as sediment entrainment into the ice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Establishing the processes driving subglacial erosion and sediment export from glaciers is key as glaciers are extremely effective erosive agents as compared with other mechanisms1,2,3, shaping mountain landscapese.g.4,5,6,7 and driving sediment delivery that impacts hydropower and ecosystemse.g.8,9,10. Underneath glaciers, sediment export responds to the availability of sediment, controlled by glacial erosion processes such as abrasion of bedrock by sliding, debris-laden ice and quarrying of bedrock1,2,11,12. Additionally, sediment export responds to subglacial fluvial transport conditions, controlled by the shear stress of water flowing through a subglacial channel with changing size13,14,15,16.

Sediment is exported fluvially either as finer sediment in suspension or as coarser bedload with intermittent contact between sediment clasts and the channel’s bed. These two mechanisms have been extensively evaluated in river systems17,18, where sediment discharge by both processes is a function of sediment supply, sediment size, sediment sorting, and flow conditions. Yet, the sediment supply and transport processes controlling bedload and suspended sediment export in subglacial fluvial systems remain highly uncertain19. Continuous high-resolution records of suspended sediment export from glaciers have been extensively collectede.g.20,21,22,23. Some mechanisms by which glaciers evacuate suspended sediment are reasonably well established from observations.20,24,25,26,27,28,29,30. However, this is not the case for bedload, with the few records available commonly collected some distance downstream from the glacier31,32, where they are impacted by subaerial hydraulic conditions and proglacial processes that modify significantly the glacier export signal33,34. Recent advances in environmental seismologye.g.35 however, allow researchers to measure bedload below glaciers and at their termini, quantifying the role of bedload transport in a glacier’s total sediment export33. This means we can now quantify both suspended load and bedload export continuously from glaciers, isolating subglacial sediment transport processes.

Observations show that bedload can comprise up to 50 % of total sediment export from a glacier during a melt season24,33, and models suggest that glacier quarrying creates bedload-sized material in amounts comparable to the suspended sediment produced by glacier abrasion36. The current assumption is that subglacial rivers have the excess capacity necessary to evacuate most of the sediment produced by erosione.g.2,19. However, research has yet to establish the differing hydraulic and geomorphic conditions leading to the fluvial mobilization of quarried-bedload material and abraded-suspended material. It appears that subglacial water can easily mobilize suspended sediment2,22. As a result, the mobilization of sediment can depend largely on sediment production and access of subglacial meltwater to abraded sediment27,30,37,38. Transporting larger bedload clasts, on the other hand, requires high shear stresses between subglacial water and the conduit bed, and this competence needs to be maintained along the full length of the channel2,19,39. As access to glacier beds is limited, subglacial sediment transport processes remains poorly evaluated, including their variability in time and space40,41. This knowledge gap inhibits a better understanding of landscape evolution and forecasting sediment discharge from glacierized catchments as they respond to changing climate with differing hydrology and glacial conditions.

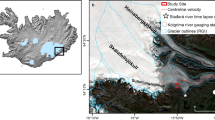

Here, we demonstrate quantitatively that different processes control bedload and suspended load export from glaciers, using records collected directly at the glacier terminus. We apply a lumped-element model of glacial erosion and sediment transport in subglacial pressurized flow conditions to topography and continuous hydrology records from the Otemma glacier in Switzerland for the melt seasons of 2020 and 2021 (Fig. 1; see Methods). Otemma glacier is a 6 km long glacier with unknown hard or soft bed characteristics, in an Alpine climate. The model setup is identical for both suspended load (SSL) and bedload (BL), except for the sediment grain size D50 (SSL: 0.2 cm ; BL: 7.8 cm 33) and sediment transport relationship (SSL: sand-sized sediment transport formula from Engelund and Hansen, 196742 and BL: bedload transport formula Wilcock and Crowe, 200343). Comparing model outputs to observed sediment transport records in a Monte Carlo framework allows us to evaluate the different parameters controlling sediment availability and subglacial sediment transport conditions. The model application first demonstrates that different subglacial sediment availability and hydraulic processes control suspended and bedload export. Using both forward model outputs and the posterior parameter distributions, we then infer the specific processes controlling bedload and suspended load export. Lastly, we discuss the impact of the different sediment transport processes on landscape evolution in glaciated terrain and on sediment export under current climate warming and glacier retreat.

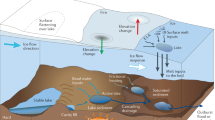

a Cartoon of subglacial processes considered in the model, with inverted parameters noted sediment production rate (\(\dot{\varepsilon }\)), the sediment height initial condition (H0), the channel shape (β), and channel roughness (fi); channel cross section modified from Delaney et al.54 b Bedload and suspended load in a subglacial channel with ice above. c Map of Otemma glacier with the star denoting measurement station location and blue outline of glacier. Image from SwissTopo.

Results

Different hydro-geomorphic processes control bedload and suspended sediment export from glaciers

Model outputs show that different processes control SSL and BL export from Otemma glacier (Fig. 2). As substantial quantities of SSL and BL are exported from the glacier33, this suggests that different parameterizations of the two processes are needed to fully capture subglacial sediment export. The mismatch in processes occurs despite the model being able to successfully represent SSL process interactions consistently in 2020 and 2021, along with capturing SSL and BL variations (Fig. 3).

Cost is defined as relative error or \(\xi (\theta)=\frac{1}{{n}_{r}}\sum \left\vert \right.\frac{\overline{Q}(\theta)-\overline{{Q}_{o}}}{\overline{{Q}_{o}}}\left\vert \right.\), where nr is the number of runs, θ is a parameter set, \(\overline{Q}(\theta)\) is model output and \(\overline{{Q}_{o}}\) is observations. Note that no parameter combinations result in model outputs that perform well for both BL and SSL.

a−j water discharge from the two seasons. b−k Sediment transport capacity (blue) and sediment discharge (red) for the cases, shaded areas represent range of outcomes. c−l Observations (\({\overline{Q_{o}}}\); orange) and range of accepted model outputs (\(\overline{Q}\); blue). Note that parameter inversion for BL in 2020 was not successful, hence the poor model performance.

To evaluate the processes that control SSL and BL, the model was run with a large number of randomly selected parameter values using inversion to identify values that best represented each transport mode. Parameters control the sediment production rate during the model run (\(\dot{\varepsilon }\)), the sediment stored below the glacier before the model initialization (H0), the channel shape (β), and channel roughness (fi; Fig. 1). Both the observations and resultant model outputs were averaged over 5 day periods and compared to the SSL and BL data using their relative error (see Methods; Fig. 2). Following the inversion, no parameter combinations successfully captured the observed variations in both BL and SSL (Fig. 2). The failure of the model to reconcile SSL and BL export together strongly suggests that different physical processes control these two transport modes.

While no single set of parameters accurately represents both SSL and BL simultaneously (Fig. 2), the model adequately represents SSL and BL individually (Fig. 3), with specific parameter combinations. We ran the model 2, 000, 000 times and retained the top performing 0.05% of model runs (1000) for bedload (BL) and suspended load (SSL) over the years 2020 and 2021, resulting in four different parameter sets. Results from the inversion show that, with optimum parameter combinations, the model’s mean relative error is between 8 % and 20 % for both BL and SSL cases. Furthermore, the model captures observed variations in sediment transport from the glacier (Fig. 3).

The variance of the optimum parameter combinations amongst the experiments further highlights the different processes that control BL and SSL export (Fig. 4). These distributions are significantly different across all four experiments. Yet, with the exception of sediment production (\(\dot{\varepsilon }\)) and friction factor (fi) each parameter correlation that is positively or negatively correlated, or insignificant, in SSL 2020 remains so in 2021 (Fig. 4a, c). This trend between years suggests that similar hydro-geomorphic processes controls SSL export. For instance, sediment production (\(\dot{\varepsilon }\)) and initial till thickness condition (H0) are negatively correlated in both years, as are channel shape factor (β) and initial till thickness condition (H0). Fewer such parameter interactions occur amongst the other three cases (Fig. 4). This agreement between 2020 and 2021 highlights consistency in SSL export processes between the 2 years and the model’s ability to represent them.

Note a similar trend in correlations between suspended load in 2020 (a) and 2021 (c). Parameter correlations for bedload experiments given in (b) and (d). Red vertical lines show mean parameter values. Posterior histograms are in purple on diagonal, with the uniform prior distributions denoted by gray histograms. Green (brown) colors denote negative (positive) Pearson’s correlation value of the corresponding scatter plot. Boxes filled with gray denote insignificant correlation at the 95% confidence interval.

In the BL case, the hydraulic parameters channel shape factor (β) and friction factor (fi) are negatively correlated in both 2020 and 2021. However, other similar interactions between the 2 years do not emerge. This absence could be due in part to the relatively short study period in 2020 that reduced the sensitivity of the sediment availability parameters, sediment production (\(\dot{\varepsilon }\)) and initial till thickness condition (H0).

Processes controlling the export of bedload and suspended load

Forward model outputs and inverted parameters demonstrate the different sediment availability and mobilization processes driving SSL and BL export (Figs. 2, 4). To establish the particular processes controlling sediment export, we examine SSL and BL results from both years. However, we note that the 2020 model runs cover a substantially shorter time period, because the model is not able to capture a severe reduction in BL export observed this season33,44 (see Methods; Figs. S4–S5). Forward model outputs show that sediment discharge capacity far exceeds sediment discharge in the SSL cases (Fig. 3b, h). Excess SSL sediment transport capacity (i.e. suspended sediment load sediment transport capacity) suggests that SSL operates in a supply-limited regime. However, a transport-limited regime controls BL export at times, with small differences between sediment discharge capacity and sediment discharge (Fig. 3k). Due to the supply-limited SSL regime, the parameters controlling subglacial sediment availability develop narrow posterior parameter distributions (sediment production rates \(\dot{\varepsilon }\)) and initial sediment thickness conditions (H0; Fig. 4a, c).

A negative correlation occurs between sediment production rate (\(\dot{\varepsilon }\)) and initial sediment thickness condition (H0) for SSL in both years (Fig. 4). The relationship develops as lower erosion rates must compensate for higher initial sediment thickness to produce the observed quantity of SSL45. In the SSL case, the posterior distributions for variables driving sediment transport capacity, β and fi, do not interact with the erosion rate (\(\dot{\varepsilon }\); Fig. 4a). β and fi values span the parameter space, resulting in viable subglacial water pressure and water velocity conditions (see Methods; Fig. 5). As a result, they do not represent particular water velocity and channel growth conditions that control sediment transport capacity, which would control SSL export in a transport-limited regime (Fig. 6).

Relationship between β and fi for SSL and BL for 2020 (a) and 2021 (b). Control points denote model runs with realistic hydraulic conditions and not those selected based on model performance. Selected points are a subset of control points with the top-performing model parameters. Notice that both SSL and BL develop positive correlation in the control points based upon the culling procedure (see Methods). However, a negative relationship emerges in BL for optimizing for sediment transport, pointing to a range of specific hydraulic conditions.

Water velocity, shear stress, channel width, and width-integrated shear stress averaged over both seasons with respect to channel shape (β; a−d, i−l) and friction (fi; e−h, m−p) factors. Light (dark) gray bars denote the range of values for BL (SSL). The percentages in each row denote the range of BL model outputs within the range of SSL conditions.

Sediment availability controls BL export as well in both years, although optimum parameter combinations for BL in 2021 are narrower than in 2020. This suggests less influence on sediment availability in 2020, likely due to the significantly shorter study period that year which limits the influence of sediment availability. Here, sediment production rate (\(\dot{\varepsilon }\)) and initial sediment thickness condition (H0) develop optimum parameter distributions that deviate significantly from their prior ones (Fig. 4a, c). During the longer study period 2021, the negative correlation between sediment production rate (\(\dot{\varepsilon }\)) and initial sediment thickness condition (H0) shows that a specific quantity of sediment must be available for an optimum model run. Despite the dependence on sediment availability, in BL for both 2020 and 2021 a strong negative relationship occurs between the two hydraulic parameters, channel shape (β) and roughness (fi). This relationship lies contrary to the positive relationship between the β and fi parameters in the SSL cases (see Methods, Fig. 5). Here, the optimum hydraulic parameters for BL are a subset of those resulting in feasible subglacial hydraulic conditions for Otemma glacier (Figs. 4d, 5). Therefore, the optimum parameter distributions reflect the specific hydrological conditions to capture the observed BL export, not possible subglacial hydraulic conditions.

Our model parameterizes SSL and BL with different relationships (SSL: Engelund and Hansen, 196742 and BL: Wilcock and Crowe, 200343). In turn, we compare hydraulic factors such as water velocity and shear stress to examine the different hydraulic conditions between the SSL and BL optimum parameter combinations. For 2021, the longer study period with more BL variations (Fig. 3d), the subset of optimum hydraulic parameters for the BL numerical experiments does not result in a specific mean sediment transport capacity over the season. In BL, parameter combinations of channel shapes (β) and roughness (fi) result in mean seasonal shear stress integrated across the channel bed width, spanning 87 % of the viable hydraulic conditions (Fig. 6d, h). Furthermore, the BL parameters result in seasonal mean channel width and water velocities covering a substantial range of viable subglacial hydraulic conditions as well (37 % and 70 % of the viable range, respectively).

The relationship between the channel shape (β) and roughness (fi) parameters in the BL cases for 2021, instead, result in a narrow seasonal mean unit shear stress, encompassing only 11% of the viable subglacial hydraulic conditions (Fig. 6b, f). Increasing channel shear stress would cause both the unit sediment transport capacity to increase and the channel’s growth rate to acceleratee.g.34,46,47,48. Over short timescales (i.e. less than a day), increases in water discharge will result in rapid increases in shear stress and thus sediment transport capacity34,49. However, at longer timescales, increased shear stress has a counteracting effect on sediment transport capacity. At time scales longer than days, elevated shear stress causes the subglacial channel size to grow, reducing water velocity and sediment transport capacity34,49. In turn, these channel size-water velocity adjustments likely filter high BL events in response to high sediment transport conditions. Similar processes occur in subaerial channels50, but likely over longer periods than the continuous channel size evolution here34. Feedbacks between channel growth and sediment transport capacity appear to heavily impact the evolution of sediment discharge in response to water discharge variations and peak discharge events (Fig. 6). As a result, further observations that evaluate subglacial channel shape or water velocity51 might yield more rigorous parameterizations of both subglacial hydrology and bedload transport. The model outputs from 2020 exhibit a similar trend in these hydraulic factors as compared to 2021, with higher sensitivity to shear stress compared to other factors (Fig. 6a–h).

Discussion

The above results demonstrate that different processes control BL and SSL export, with BL being partially controlled by hydraulic factors and SSL fully responding to sediment availability at Otemma glacier. Interplay between hydraulic parameters values for channel shape (β) and roughness (fi) can result in viable subglacial hydraulic conditions for BL export (Fig. 5)51,52. However, results here suggest that only a narrow range of parameter combinations can result in the sediment transport capacity variations needed to capture the observed BL export (Fig. 4). Other glaciers may exhibit different dependence on sediment production rate (\(\dot{\varepsilon }\)) and initial sediment thickness (H0) that impacts their sediment export characteristicse.g.16. For instance, the strong dependence of SSL export on glacier sliding for a relatively steep glacier may suggest reduced sediment storage and greater dependence on sediment production rate (\(\dot{\varepsilon }\))27. Conversely, thick sediment has been observed below the Greenland Ice Sheet53, suggesting greater initial sediment thickness condition (H0) there. Additionally, values of sediment production rate (\(\dot{\varepsilon }\)) and initial sediment thickness condition (H0) could depend on the time period of the inversion. For instance, longer study periods may result in larger initial sediment thickness conditions (H0) to account for the continuity of sediment availability across the inversion period45.

These findings support previously proposed mechanisms for SSL increases under climate warming9,10,28,30,38. SSL model performance responds strongly to sediment availability both through sediment production (\(\dot{\varepsilon }\)) and sediment storage (H0; Fig. 4). The suggested increase occurs as rising melt elevations on glaciers leads to the entrainment of previously inaccessible sediment at high elevations, instead of particular subglacial hydraulic conditions that partially impact BL transport. Furthermore, supply-limited transport conditions in SSL suggest that little suspended sediment persists in the main channels with high sediment transport capacity (Fig. 3) or at lower elevations of glaciers30. Instead, suspended sediment likely originates from higher-order channels with lower water discharge and sediment transport capacity54.

Similarly, sediment availability’s role in representing SSL export could support using empirical “erosion rules” in parameterizing glacier abrasion and suspended sediment exporte.g.6,27,37,55,56. “Erosion rules” could well represent sediment production through abrasion, itself heavily dependent on glacier sliding and particularly abrasive power at the glacier bed2,11,27,37,57. SSL numerical experiments here suggest that sediment is evacuated with relative ease once produced by abrasion and accessed by a subglacial channel, independent of subglacial sediment transport conditions (Fig. 3b,h). Furthermore, “erosion rules” are largely based on suspended sediment measurements7,58 (i.e. turbidity measurements, remote sensing of sediment plumes, or sediment cores). As these relationships represent glacier abrasion and suspended sediment export well, they could be referred to as “abrasion rules.”

BL, on the other hand, is evacuated less efficiently (Fig. 3), potentially leaving substantial sediment available at the glacier bed. BL’s partial dependence on sediment transport availability could be even less than the analysis suggests here (Fig. 4). The model’s lumped nature means it over-estimates sediment access to subglacial channels, and thus evacuation efficiency45. Furthermore, additional subglacial channels underneath the glacier, beyond the single one in this model, could significantly reduce subglacial sediment transport capacity15. As a result, the tendency for bedload sized sediment to be retained or deposited underneath glaciers may cause it to insulate bedrock from glacial erosion by quarrying or abrasion39,41,59,60,61. Therefore, glacial erosion of bedrock may only occur if sediment is evacuated by non-fluvial means such as entrainment by the icee.g.62 or sediment deformatione.g.63.

BL’s response to changing glacio-climatic conditions remains uncertain given its dependence on subglacial hydraulic factors. The evolution of subglacial hydraulics as glaciers thin and melt increases results in competing interactions between changing hydrological regimese.g.64, increasing water discharge variability65 and slowing channel closure rates as ice thins66. Additionally, the especially strong sensitivity of glacial quarrying to subglacial hydrology36,67 makes it challenging to identify conditions of future BL sediment production, whereas the changes to glacier sliding could be more straight forward to identify.68,69,70.

Our analysis demonstrates that different physical processes control SSL and BL export from glaciers, despite significant export quantities of each. These differences mean that bedload and suspended sediment transport types should be considered individually when evaluating sediment export and erosion rates from glaciers, similar to rivers18. As results suggest sediment availability drives suspended sediment export, using empirical “abrasion/erosion rules” to quantify sediment production can work well for suspended sediment export. However, when evaluating bedload export, particular attention should be paid to the subglacial hydraulic conditions that drive the channel growth and water velocity as they respond to water discharge variations, along with sediment availability. While subglacial hydraulic processes can be difficult to evaluate, they drive bedload export through glacierized catchments, impacting downstream fluvial systems. Furthermore, the retention of sediment at the glacier bed may armor it from further erosion, invoking other processes necessary to evacuate sediment and maintain bedrock erosion.

Methods

Datasets

The model requires inputs of water discharge and glacier topography to be compared with bedload and suspended sediment discharge from the glacier.

We use water discharge, bedload discharge, and suspended sediment discharge data collected from Otemma glacier (\(4{5}^{\circ }\,5{7}^{{\prime} }\,3{4}^{{\prime}{\prime} }\) N, \({7}^{\circ }\,2{7}^{{\prime} }\,2{1}^{{\prime}{\prime} }\) E) during summers of 2020 and 2021 at a 2 min resolution33. The continuous record of suspended sediment export was evaluated using turbidity probes calibrated to a turbidity-suspended sediment relationship. The flux of suspended sediment was established by multiplying the suspended sediment concentration by the coincident water discharge, also measured at the site using a stage height-water discharge relationship. Bedload transport flux was monitored using seismic data. To quantify the bedload flux, seismic data was post-processed using a geophysical inversion model71 in the open source R package eseis (version 0.5. 0). Field tests were used to establish model parameters and the model was calibrated using coincident water stage measurements as no direct measurements of bedload transport were available33. We also note, that temporal changes in bedload export also correspond to changing behavior of the proglacial river identified through imagery analysis44. These datasets are introduced to the model using a linear interpolated spline, and timestamps with no data were omitted from the analysis.

Ice thickness in the main trunk of Otemma glacier was estimated to be 150 m using available data72. The glacier is estimated to be 6 km long and on average 1 km wide based upon 2020 aerial photographs from SwissTopo(https://map.geo.admin.ch). Otemma glacier’s terminus is at 2496 ma.s.l., while we consider its maximum elevation of the main glacier at Col de Charmotane 3016 ma.s.l.

Subglacial sediment transport model

We use a lumped-element model that evolves the thickness of a subglacial sediment layer in response to transport and supply-limited sediment transport conditions and erosional processes45. A lumped subglacial hydraulics model was used to establish sediment transport capacity34.

A lumped-element model simulates the evolution of the thickness of a subglacial till layer H 45. Sediment production, or bedrock erosion, adds sediment to the layer. Fluvial sediment transport in supply- and transport-limited regimes mobilizes or deposits sediment, thus removing or adding material to the till layer, respectively16,73. The model uses the Exner Equation74,75,76, a mass conservation relationship, to evolve the till layer height

where H is the till layer height, l (w) is the glaciers’ length (width), \(\dot{m}\) is a sediment production rate. Qs represents fluvial sediment flux underneath the glacier

\(\widehat{Q}\) is the sediment discharge capacity (see equations (9) and (10)), σ is a sigmoidal function, smoothing the transition from transport to supply-limited conditions when H is small, effectively reducing sediment availability16.

The source term \(\dot{m}\) is defined as,

where Hmax denotes the maximum height of till beyond which sediment production ceases and \(\dot{\varepsilon }\) represents the rate of bedrock erosion held steady through the model run (Table S1). In the application here, erosion rate is an explicit parameter45, unlike previous work16,54, where erosion depends on glacier sliding or shear stress.

We leverage a lumped R-channel model34 to parameterize the subglacial hydraulics and sediment transport capacity needed to establish Qs (Equation (1)). This model assumes that water flows through a subglacial channel with length l, underneath a glacier a mean ice thickness of hice. Channel size evolves S with an opening term representing frictional heating from water flow and a closure term from ice creep

where t represents time, \({C}_{1}=(1-{\rho }_{w}{c}_{p}{c}_{t})\frac{{\rho }_{w}g}{{\rho }_{i}L}\) and \({C}_{2}=2A{\left(\frac{{\rho }_{w}g}{n}\right)}^{n}\) are constants (refer to Table S1), g denotes gravitational acceleration, Qw is the water discharge, \(\overline{h}=\frac{1}{2}({h}_{ice}+{h}_{p})\) is the mean hydraulic head, with hp is the proglacial head (0), l, \({h}_{o}=\frac{{\rho }_{i}}{{\rho }_{w}}{h}_{ice}\) indicates the mean ice overburden pressure, ρw and ρi are the densities of water and ice respectively, and n is Glen’s parameter, typically n = 377.

The head drop Δh is

where fi is a friction factor, Dh is the hydraulic diameter, l is the channel or glacier length, and \(v=\frac{{Q}_{w}}{S}\) is the water velocity. Channel area S comes from the hydraulic diameter Dh with

where β is the central angle of the circular segment of the channel boundary (Hooke angle)78. The width of the channel floor w is represented as

Shear stress τ, needed in most sediment transport relationships, is established through the Darcy-Weisbach formulation

where fi is the Darcy-Weisbach friction factor and velocity \(v=\frac{{Q}_{w}}{S}\). In applying the model to measurements of SSL, we implement the total sediment transport relationship of Engelund and Hansen42

where ρb and ρw are the density of the bedrock or sediment, fi is the friction factor above, D50 is median sediment size, τ is the shear stress evaluated in Equation (8), and \(\widehat{w}\) denotes the width of the channel floor that integrates the sediment transport rate across the width of the subglacial channel (Equation (7); Table S1).

To evaluate volumetric bedload transport when comparing model outputs to the BL record, we implement the Wilcock and Crow43 sediment transport relationship

where Rh is the hydraulic radius of the channel (\({R}_{h}=\frac{{D}_{h}}{4}\)), and W * is the dimensionless transport rate, and Ψ is the hydraulic gradient \(\frac{\Delta h}{l}\).

where ψ* is the ratio between the dimensionless bed shear stress and the dimensionless reference bed shear stress, given as

Note that this relationship is valid for values of D50 >4 mm.

Numerical experiments

We apply the model to records of suspended sediment load (SSL) and bedload (BL) discharge from the Otemma glacier (Section), using the respective sediment transport relationship (Eqs. (9) and (10)).

We run the model a large number of times with different parameter values and test model outputs against the observed records of sediment discharge in a Monte Carlo framework45,79. Parameter values are selected randomly so that they do not depend on the model outcomes of a previous set of parameter. We selected parameter ranges such that distributions formed within their boundaries across all four ensembles (SSL and BL with 2020 and 2021; Fig. figu4). This way parameters from all four ensembles were sampled from the same prior distributions.

To implement this scheme, for each model run we create a vector of randomly selected parameter values θ to run in the forward model

\(\dot{\varepsilon }\) is the sediment production rate to produce sediment over the model run used to evaluate the till source \(\dot{m}\) in ref. 45. H0 is the initial till height condition used to evaluate the amount of sediment stored below the glacier before the model initialization. β is the Hooke angle, controlling the shape and thus the width of the subglacial channel 78. fi is the Darcy-Weisbach friction factor used to evaluate the water velocity and hydraulic potential to calculate shear stress and evolution of channel size (see ref. 34). The range of possible values and their sampling distribution are given in Table S1.

When running the model forward, we apply a spin-up to establish the initial channel cross-sectional area by applying maximum water discharge over the first 3 days of the study period until the change in cross-sectional area is negligible.

Model outputs (Q) with different parameters (θ) are compared against the observed sediment discharge records (Qo) from the BL or SSL datasets using relative error (ξ)

nr is the number of data points. \(\overline{Q}\) and \(\overline{{Q}_{o}}\) are values averaged over 5 day periods, to reduce the impact of sediment transport times compared to water discharge within the glacier, which is not accounted for in the model e.g. Ref. 80.

For the year 2020, model runs commenced for on June 26, 2020 and ceased on August 31, 2020. For 2021, model runs commenced on June 15, 2021 and ceased on August 1, 2021. These periods coincides with available bedload and suspended load data. In 2021, data were collected until August 22, 2021. However, a substantial reduction in sediment export from Otemma glacier occurred between August 1 to 3, 2021. The possibility that this resulted from instrument error is minimal as imagery shows that proglacial forefield morphodynamics were tightly coupled to the reduced sediment input44. The lumped element model here does not able to capture this transition to reduced sediment export (Fig. S4–S5). Therefore, we only model the beginning of the season in 2020.

We cull model runs if they experience a flotation fraction of > 1.2 or if their hydraulic head exceeds the maximum glacier elevation for >1% of the study period. Additionally, we remove model runs experiencing water velocity > 1.5 m s−1.

To test the viability of similar processes to capture SSL and BL, the model is first run with 500, 000 identical parameter values for SSL and BL cases over both 2020 and 2021. The comparison is done using Equation (14), with physically infeasible runs being culled.

Additionally, we identify optimum parameter combinations using inversion a Monte Carlo inversion. We run the model with 2 × 106 randomly selected parameter values and quantify the relative error for each viable one (ξ; Equation (14)). For the analysis of both the posterior parameter combinations and their resultant forward model behavior, we utilize the top performing 0.05% (1000) of all runs.

Data availability

Sediment transport data used in this study is available from Mancini et al.33.

Code availability

Running and plotting scripts are available at https://bitbucket.org/IanDelaney/otemma/src/master/. The complete code is available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15227775.

References

Hallet, B., Hunter, L. & Bogen, J. Rates of erosion and sediment evacuation by glaciers: a review of field data and their implications. Glob. Planet. Change 12, 213–235 (1996).

Alley, R. B. et al. How glaciers entrain and transport basal sediment: physical constraints. Quat. Sci. Rev. 16, 1017–1038 (1997).

Wilner, J. et al. Limits to timescale dependence in erosion rates: quantifying glacial and fluvial erosion across timescales. Sci. Adv. 10, eadr2009 (2024).

Harbor, J., Hallet, B. & Raymond, C. A numerical model of landform development by glacial erosion. Nature 333, 347–349 (1988).

Montgomery, D. Valley formation by fluvial and glacial erosion. Geology 30, 1047–1050 (2002).

Egholm, D., Nielsen, S., Pedersen, V. & Lesemann, J.-E. Glacial effects limiting mountain height. Nature 460, 884–887 (2009).

Herman, F., De Doncker, F., Delaney, I., Prasicek, G. & Koppes, M. The impact of glaciers on mountain erosion. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2, 422–435 (2021).

Lane, S. et al. Making stratigraphy in the Anthropocene: climate change impacts and economic conditions controlling the supply of sediment to Lake Geneva. Sci. Rep. 9, 8904 (2019).

Li, D. et al. High Mountain Asia hydropower systems threatened by climate-driven landscape instability. Nat. Geosci. 15, 520–530 (2022).

Zhang, T. et al. Warming-driven erosion and sediment transport in cold regions. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 3, 832–851 (2022).

Hallet, B. A theoretical model of glacial abrasion. J. Glaciol. 23, 39–50 (1979).

Iverson, N. R. A theory of glacial quarrying for landscape evolution models. Geology 40, 679–682 (2012).

Creyts, T. T., Clarke, G. K. C. & Church, M. Evolution of subglacial overdeepenings in response to sediment redistribution and glaciohydraulic supercooling. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. 118, 423–446 (2013).

Beaud, F., Flowers, G. & Venditti, J. G. Modeling sediment transport in ice-walled subglacial channels and its implications for esker formation and pro-glacial sediment yields. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. 123, 1–56 (2018).

Hewitt, I. & Creyts, T. A model for the formation of eskers. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 6673–6680 (2019).

Delaney, I., Werder, M. A. & Farinotti, D. A numerical model for fluvial transport of subglacial sediment. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. 124, 2197–2223 (2019).

Einstein, H., Anderson, A. & Johnson, J. A distinction between bed-load and suspended load in natural streams. Eos, Trans. Am. Geophys. Union 21, 628–633 (1940).

Turowski, J. M., Rickenmann, D. & Dadson, S. The partitioning of the total sediment load of a river into suspended load and bedload: a review of empirical data. Sedimentology 57, 1126–1146 (2010).

Alley, R. B., Cuffey, K. M. & Zoet, L. K. Glacial erosion: status and outlook. Ann. Glaciol. 60, 1–13 (2019).

Collins, D. N. Sediment concentration in melt waters as an indicator of erosion processes beneath an Alpine glacier. J. Glaciol. 23, 247–257 (1979).

Bezinge, A., Clark, M. J., Gurnell, A. M. & Warburton, J. The management of sediment transported by glacial melt-water streams and its significance for the estimation of sediment yield. Ann. Glaciol. 13, 1–5 (1989).

Willis, I. C., Richards, K. S. & Sharp, M. J. Links between proglacial stream suspended sediment dynamics, glacier hydrology and glacier motion at Midtdalsbreen, Norway. Hydrol. Process. 10, 629–648 (1996).

Hodson, A. et al. Suspended sediment yield and transfer processes in a small High-Arctic glacier basin, Svalbard. Hydrol. Process. 12, 73–86 (1998).

Riihimaki, C. A., MacGregor, K. R., Anderson, R. S., Anderson, S. P. & Loso, M. G. Sediment evacuation and glacial erosion rates at a small alpine glacier. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. https://doi.org/10.1029/2004JF000189 (2005).

Orwin, J. F. & Smart, C. C. An inexpensive turbidimeter for monitoring suspended sediment. Geomorphology 68, 3–15 (2005).

Swift, D., Nienow, P. W. & Hoey, T. B. Basal sediment evacuation by subglacial meltwater: suspended sediment transport from Haut Glacier d’Arolla, Switzerland. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 30, 867–883 (2005).

Herman, F. et al. Erosion by an alpine glacier. Science 350, 193–195 (2015).

Li, D. et al. Exceptional increases in fluvial sediment fluxes in a warmer and wetter High Mountain Asia. Science 374, 599–603 (2021).

Lu, X. et al. Proglacial river sediment fluxes in the southeastern Tibetan Plateau: Mingyong Glacier in the upper Mekong River. Hydrol. Process. 36, e14751 (2022).

Vergara, I., Garreaud, R. & Ayala, Á. Sharp increase of extreme turbidity events due to deglaciation in the subtropical Andes. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. 127, e2021JF006584 (2022).

Pearce, J. et al. Bedload component of glacially discharged sediment: insights from the Matanuska Glacier, Alaska. Geology 31, 7–10 (2003).

Mao, L. et al. Bedload hysteresis in a glacier-fed mountain river. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 39, 964–976 (2014).

Mancini, D. et al. Filtering of the signal of sediment export from a glacier by its proglacial forefield. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2023GL106082 (2023).

Delaney, I., Tedstone, A., Werder, M. A. & Farinotti, D. Subglacial and subaerial fluvial sediment transport capacity respond differently to water discharge variations. EGUsphere https://doi.org/10.5194/egusphere-2024-2580 (2024).

Gimbert, F., Tsai, V. C., Amundson, J. M., Bartholomaus, T. C. & Walter, J. I. Subseasonal changes observed in subglacial channel pressure, size, and sediment transport. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 3786–3794 (2016).

Ugelvig, S. V., Egholm, D. L., Anderson, R. S. & Iverson, N. R. Glacial erosion driven by variations in meltwater drainage. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. 123, 2863–2877 (2018).

Koppes, M. et al. Observed latitudinal variations in erosion as a function of glacier dynamics. Nature 526, 100–103 (2015).

Delaney, I. & Adhikari, S. Increased subglacial sediment discharge during century scale glacier retreat: consideration of ice dynamics, glacial erosion and fluvial sediment transport. Geophyis. Res. Lett. 47, e2019GL085672 (2020).

Alley, R. B., Lawson, D. E., Larson, G. J., Evenson, E. B. & Baker, G. S. Stabilizing feedbacks in glacier-bed erosion. Nature 424, 758–760 (2003).

Jenkin, M. et al. Tracking coarse sediment in an Alpine subglacial channel using radio-tagged particles. J. Glaciol. 69, 1992–2006 (2023).

Núñez Ferreira, F. et al. Subglacial hydrology insights from eskers developed atop soft beds of the laurentide ice sheet. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 50, e6037 (2025).

Engelund, F. & Hansen, E. A Monograph on Sediment Transport in Alluvial Streams, Vol. 62 (Academic Publisher, 1967).

Wilcock, P. & Crowe, J. Surface-based transport model for mixed-size sediment. J. Hydraul. Eng. 129, 120–128 (2003).

Mancini, D. et al. Rates of evacuation of bedload sediment from an alpine glacier control proglacial stream morphodynamics. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. 129, e2024JF007727 (2024).

Delaney, I. et al. Controls on sediment transport from a glacierized catchment in the swiss alps established through inverse modeling of geomorphic processes. Water Resour. Res. 60, e2023WR035589 (2024).

Shields, A. Anwendung der Aehnlichkeitsmechanik und der Turbulenzforschung auf die Geschiebebewegung. (PhD Thesis Technical University Berlin, 1936).

Clarke, G. K. C. Lumped-element model for subglacial transport of solute and suspended sediment. Ann. Glaciol. 22, 152–159 (1996).

Clarke, G. K. C. Hydraulics of subglacial outburst floods: new insights from the Spring–Hutter formulation. J. Glaciol. 49, 299–313 (2003).

Werder, M. A., Schuler, T. V. & Funk, M. Short term variations of tracer transit speed on alpine glaciers. Cryosphere 4, 381–396 (2010).

Phillips, C. & Jerolmack, D. Self-organization of river channels as a critical filter on climate signals. Science 352, 694–697 (2016).

Pohle, A., Werder, M. A., Gräff, D. & Farinotti, D. Characterising englacial R-channels using artificial moulins. J. Glaciol. 68, 879–890 (2022).

Werder, M. A. & Funk, M. Dye tracing a jökulhlaup: II. testing a jökulhlaup model against flow speeds inferred from measurements. J. Glaciol. 55, 899–908 (2009).

Walter, F., Chaput, J. & Lüthi, M. Thick sediments beneath Greenland’s ablation zone and their potential role in future ice sheet dynamics. Geology 42, 487–490 (2014).

Delaney, I., Anderson, L. & Herman, F. Modeling the spatially distributed nature of subglacial sediment transport and erosion. Earth Surf. Dyn. 11, 663–680 (2023).

Humphrey, N. & Raymond, C. Hydrology, erosion and sediment production in a surging glacier: Variegated Glacier, Alaska, 1982–83. J. Glaciol. 40, 539–552 (1994).

Herman, F. & Braun, J. Evolution of the glacial landscape of the Southern Alps of New Zealand: Insights from a glacial erosion model. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. https://doi.org/10.1029/2007JF000807 (2008).

Hansen, D. D. et al. A power-based abrasion law for use in landscape evolution models. Geology 51, 273–277 (2023).

Cook, S., Swift, D., Kirkbride, M., Knight, P. & Waller, R. The empirical basis for modelling glacial erosion rates. Nat. Commun. 11, 1–7 (2020).

de Winter, I., Storms, J. & Overeem, I. Numerical modeling of glacial sediment production and transport during deglaciation. Geomorphology 167-168, 102–114 (2012).

Stevens, D. et al. Effects of basal topography and ice-sheet surface slope in a subglacial glaciofluvial deposition model. J. Glaciol. 69, 247 (2022).

Delaney, I. & Anderson, L. S. Debris cover limits subglacial erosion and promotes till accumulation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL099049 (2022).

Iverson, N. R. Regelation of ice through debris at glacier beds: Implications for sediment transport. Geology 21, 559–562 (1993).

Hansen, D. D. & Zoet, L. K. Characterizing sediment flux of deforming glacier beds. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. 127, e2021JF006544 (2022).

Brunner, M. I., Farinotti, D., Zekollari, H., Huss, M. & Zappa, M. Future shifts in extreme flow regimes in Alpine regions. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 23, 4471–4489 (2019).

Lane, S. & Nienow, P. Decadal-scale climate forcing of alpine glacial hydrological systems. Water Resour. Res. 55, 2478–2492 (2019).

Röthlisberger, H. Water pressure in intra– and subglacial channels. J. Glaciol. 11, 177–203 (1972).

Beaud, F., Flowers, G. E. & Pimentel, S. Seasonal-scale abrasion and quarrying patterns from a two-dimensional ice-flow model coupled to distributed and channelized subglacial drainage. Geomorphology 219, 176–191 (2014).

Tedstone, A. et al. Decadal slowdown of a land-terminating sector of the Greenland Ice Sheet despite warming. Nature 526, 692–695 (2015).

Dehecq, A. et al. Twenty-first century glacier slowdown driven by mass loss in High Mountain Asia. Nat. Geosci. 12, 22 (2019).

Polashenski, D., Truffer, M. & Armstrong, W. Reduced basal motion responsible for 50 years of declining ice velocities on athabasca glacier. J. Glaciol. 70, e26 (2024).

Dietze, M., Lagarde, S., Halfi, E., Laronne, J. & Turowski, J. Joint sensing of bedload flux and water depth by seismic data inversion. Water Resour. Res. 55, 9892–9904 (2019).

Grab, M. et al. Ice thickness distribution of all Swiss glaciers based on extended ground-penetrating radar data and glaciological modeling. J. Glaciol. 67, 1074–1092 (2021).

Brinkerhoff, D., Truffer, M. & Aschwanden, A. Sediment transport drives tidewater glacier periodicity. Nat. Commun. 8, 90 (2017).

Exner, F. M. Über die Wechselwirkung zwischen Wasser und Geschiebe in flüssen. Abhandlungen der Akadamie der Wissenschaften Wien. 134, 165–204 (1920).

Exner, F. M. Zur physik der dünen. Abhandlungen der Akadamie der Wissenschaften, Wien. 129, 929–952 (1920).

Paola, C. & Voller, V. R. A generalized exner equation for sediment mass balance. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. https://doi.org/10.1029/2004JF000274 (2005).

Glen, J. The creep of polycrystalline ice. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A. Math. Phys. Sci. 228, 519–538 (1955).

Hooke, R. L., Laumann, T. & Kohler, J. Subglacial water pressures and the shape of subglacial conduits. J. Glaciol. 36, 67–71 (1990).

Beven, K. & Binley, A. GLUE: 20 years on. Hydrol. Process. 28, 5897–5918 (2014).

Williams, G. P. Sediment concentration versus water discharge during single hydrologic events in rivers. J. Hydrol. 111, 89–106 (1989).

Acknowledgements

Funding from Swiss National Science Foundation project 200021-188734/1 (S.N.L.) supported the data collection and supported M.J. Swiss National Science Foundation project PZ00P2_202024 (ID) supported I. Delaney. We are grateful to B. Schaefli for insightful discussions about experiment design. The Swiss Geocomputing Centre, Université de Lausanne, provided computational resources.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The concept of this study was developed by I.D. and S.N.L. F.L. and I.D. carried out the model runs. Observational data were collected by M.J., D.M. and S.N.L. I.D. developed the methodology and model. I.D. led the writing process. I.D., F.L., M.J., D.M. and S.N.L. contributed to investigation and editing/review of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Delaney, I., Lardet, F., Jenkin, M. et al. Different geomorphic processes control suspended sediment and bedload export from glaciers. Nat Commun 16, 6005 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60776-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60776-4