Abstract

Building hybrid quantum systems is a crucial step for realizing multifunctional quantum technologies, quantum information processing, and hybrid quantum networks. A functional hybrid quantum system requires strong coupling among its components, however, couplings between distinct physical systems are typically very weak. Here we demonstrate the realization of triple strong coupling in a polaromechanical hybrid system where polaritons, formed by strongly coupled ferromagnetic magnons and microwave photons, are further strongly coupled to phonons. We observe the corresponding polaromechanical normal-mode splitting. By significantly reducing the polariton decay rate via realizing coherent perfect absorption, we achieve a high polaromechanical cooperativity of 9.4 × 103. A quantum cooperativity much greater than unity is achievable at cryogenic temperatures, which would enable various quantum applications. Our results pave the way towards coherent quantum control of photons, magnons and phonons, and are a crucial step for building functional hybrid quantum systems based on magnons.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Quantum information processing, quantum technologies, and the building of hybrid quantum networks require hybrid quantum systems (HQSs), which combine different physical systems with their individual strengths and complementary functionalities, to store, process, and transmit quantum information1,2,3,4. A prerequisite for realizing a functional HQS is the ability to exchange quantum states between its components with high fidelity, which requires strong coupling, where reversible energy exchange between interacting systems is faster than their energy dissipation to the environment. To date, strong coupling has been realized in a variety of quantum systems, such as atoms and optical photons5, superconducting qubits and microwave photons6, excitons and microcavity photons7, among others. In terms of mechanical systems, promising components for HQSs given their ability to couple with various quantum systems and high quality factors, strong coupling has been achieved with optical or microwave photons8,9,10, a superconducting qubit11,12,13,14,15, a quantum dot16, atomic spins17, etc. This enables not only the function of a mechanical “quantum bus” for interfacing and communicating between different quantum systems, but also the preparation and control of quantum states of mechanical oscillators, which has been a subject of long-standing interest18.

Of particular interest is to build HQSs composed of more than two components, ranging from photons, atoms, and spins to superconducting and nanomechanical structures, especially when they are of different nature, where hybridization is maximized to integrate complementary functionalities. Over the past few years, collective spin excitations (magnons) in magnetic materials, e.g., yttrium iron garnet (YIG), have been demonstrated as possible building blocks for quantum technologies19,20, quantum information processing21, quantum networks22, and quantum computing23. Their unique feature is that they can coherently interact with a variety of quantum systems including microwave or optical photons, superconducting qubits, acoustical phonons, etc24,25,26. However, couplings between excitations of distinct physical systems are typically very weak, and this is particularly the case when the excitation frequencies differ greatly2. Impressively, the quasiparticles termed phonoritons – arising from the strong coupling between photons, phonons, and excitons, have been predicted27 and recently observed28 in a microcavity. However, up to now, the realization of such a triple strong coupling in a hybrid magnonic system remains challenging and one of the goals of this hybrid system.

Here, we report an experimental realization of strong coupling in a polaromechanical system29 involving three different quanta, namely, ferromagnetic magnons, microwave photons, and long-lived phonons. In the experiment, magnon polaritons (MPs)30, formed by strong interaction between magnons and microwave cavity photons, are further strongly coupled with vibrational phonons that are induced by the magnetostriction of a YIG sphere. The decay rate of the MP can be significantly reduced by operating the system at the conditions of coherent perfect absorption (CPA)31,32,33,34, under which the microwave cavity mode achieves an effective gain35. By further operating the system at the (cavity) gain-(magnon) loss balance, the decay rate of the MP is reduced to nearly zero. This, together with the small mechanical damping rate, leads to the strong coupling between the mechanical mode and the driven MP, as witnessed by an evident normal-mode splitting (NMS) at the mechanical sideband. The normal modes of the system are then the hybridization of photons, magnons and phonons, which explicitly indicates that the system is in the triple strong-coupling regime. A remarkably high polaromechanical cooperativity ~ 9.4 × 103 is accordingly achieved.

Results

The polaromechanical system

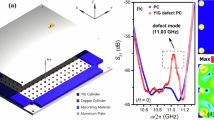

The polaromechanical system is schematically shown in Fig. 1a, which consists of a 3D microwave cavity and a YIG sphere supporting both a magnon mode and a deformation vibration mode. The magnon mode couples to the microwave cavity mode via the magnetic dipole interaction36,37,38, and to the mechanical vibration mode via the magnetostrictive interaction39,40,41,42 (Fig. 1b). The cavity TE102 mode has a resonance frequency ωa/2π = 7.213 GHz and a total decay rate κa, which is contributed by three dissipation channels, i.e., κa = κint + κ1 + κ2, with the intrinsic decay rate κint/2π = 1.98 MHz, and the external decay rate κ1(2) due to the connection to the cavity port 1(2). To implement the CPA, κ1(2) is set to be tunable by adjusting the length δl1(2) of the SMA adaptor’s pin into the cavity. The frequency of the magnon mode can be continuously adjusted by varying the external bias magnetic field B0 via ωm = γB0, with the gyromagnetic ratio γ/2π = 28 GHz/T. The magnon decay rate κm/2π = 0.49 MHz, and the magnon-cavity coupling strength gma/2π = 6.63 MHz. The magnon mode is driven by a microwave field loaded via a loop antenna, which further drives the mechanical mode through the magnomechanical coupling. In the experiment, we observe three mechanical modes with close resonance frequencies (see the Supplementary Information (SI) for details), and we focus on the mode of frequency ωb/2π = 10.9565 MHz, which exhibits the strongest bare magnomechanical coupling rate gmb/2π = 1.40 mHz and the lowest damping rate κb/2π = 155 Hz.

a The microwave signal generated by a vector network analyzer (VNA) is equally divided into two beams through a power splitter (PS). The amplitude and phase of each beam can be independently tuned by a variable attenuator (VA) and variable phase shifter (VPS). The two microwave fields are injected into the cavity after through two directional couplers (DCs) connected to the two ports, and the output fields are measured by the VNA after the DCs. The microwave cavity is a 3D oxygen-free copper cavity with dimensions of 60 × 25 × 6 mm3, and a 0.25-mm-diameter YIG sphere is placed at the antinode of the magnetic field of the cavity TE102 mode. The YIG sphere is supported by a horizontal glass capillary and can move freely to reduce the mechanical damping. At the top of the cavity, a coil connected with a microwave source is used to directly drive the YIG sphere. Each cavity port is fixed with a SMA adaptor, and the length of the SMA adaptor’s pin entering the cavity δl1(2) can be tuned. The external magnetic field B0 (in the z direction) is applied to set the frequency of the magnon mode. The experiment is performed at room temperature. b Three interacting modes of the system, including a cavity mode, a magnon mode, and a vibration mode. At the top is the magnetic field distribution of the cavity TE102 mode.

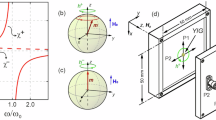

Thanks to the high spin density of the YIG, the magnon mode and the cavity are strongly coupled, gma > κa, κm, leading to two hybridized MPs36,37,38. The corresponding frequencies ω± and decay rates κ± of the two polariton modes are given by \({\omega }_{\pm }-i{\kappa }_{\pm }=\frac{1}{2}[({\omega }_{{{{\rm{a}}}}}+{\omega }_{{{{\rm{m}}}}})-i({\kappa }_{{{{\rm{a}}}}}+{\kappa }_{{{{\rm{m}}}}})\pm {\xi }^{\frac{1}{2}}]\), where \(\xi=4{g}_{{{{\rm{ma}}}}}^{2}+{\left[\left({\omega }_{{{{\rm{a}}}}}-{\omega }_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}\right)-i\left({\kappa }_{{{{\rm{a}}}}}-{\kappa }_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}\right)\right]}^{2}\). The linearized Hamiltonian of the system in terms of two polariton modes reads (see SI)

where \({p}_{+}=a\cos \theta+m\sin \theta\) and \({p}_{-}=-a\sin \theta+m\cos \theta\) denote the annihilation operators of the upper- and lower-branch polaritons, respectively, satisfying the bosonic commutation relation \([{p}_{\pm },{p}_{\pm }^{{{\dagger}} }]=1\), and \(\theta=\frac{1}{2}\arctan (\frac{2{g}_{{{{\rm{ma}}}}}}{{\omega }_{{{{\rm{a}}}}}-{\omega }_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}})\) determines the proportion of the magnon (cavity) mode in the two polaritons; a, m, and b (a†, m†, and b†) are the annihilation (creation) operators of the cavity, magnon and mechanical modes, respectively, and \(x=(b+{b}^{{{\dagger}} })/\sqrt{2}\) denotes the mechanical displacement by magnetostriction; G+(−) is the effective coupling strength between the upper (lower)-branch polariton and the mechanical mode, and their expressions are

where M ≡ 〈m〉 is the steady-state average of the magnon mode and nmag = ∣M∣2 is the number of magnon excitations. A similar polaromechanical coupling exists in an exciton-photon-phonon system43. Equation (2) indicates that the polaromechanical coupling G+(−) can be significantly enhanced by strongly driving the magnon mode. When the coupling rate exceeds the dissipation rates of the polariton and mechanical modes, i.e., G+(−) > κ+(−), κb, the system enters the polaromechanical strong-coupling regime, in which the normal modes are the hybridization of photons, magnons and phonons. Previous experiments have demonstrated relatively weak couplings, i.e., G± up to tens of kHz39,41,42, due to the intrinsically small bare coupling gmb < 10 mHz, which is much smaller than the polariton decay rates κ± ~ 1 MHz (limited by the magnon intrinsic loss). The enhancement of the coupling strength G± by further increasing the drive power is restricted by strong nonlinear effects of the YIG sphere42,44. Therefore, the polaromechanical strong coupling of the system is yet to be achieved.

Polariton decay rate reduction via CPA

A natural idea to achieve the polaromechanical strong coupling is to reduce the dissipation rate of the polariton mode. To this end, we exploit the CPA to achieve an effective gain of the cavity mode. The CPA refers to the fact that, due to the destructive interference between the input and output fields at the cavity port, the amplitude of the cavity output field turns out to be zero31,32,33,34. This approach has been adopted to realize the exceptional point associated with the parity-time symmetry in cavity magnonics35 and optical microcavities34. Under the CPA conditions, the output field of the cavity \({A}_{1(2)}^{{{{\rm{out}}}}}=0\). The input-output relation \({A}_{1(2)}^{{{{\rm{out}}}}}=\sqrt{2{\kappa }_{1(2)}}A-{a}_{1(2)}^{{{{\rm{in}}}}}\)45 thus leads to the input field \({a}_{1(2)}^{{{{\rm{in}}}}}=\sqrt{2{\kappa }_{1(2)}}A\), which provides a gain for the cavity mode (see SI). The cavity mode is then compensated to be a gain mode with an effective gain rate35: \({\kappa }_{{{{\rm{a}}}}}^{{\prime} }\equiv {\kappa }_{1}+{\kappa }_{2}-{\kappa }_{{{{\rm{int}}}}}\). The CPA requires that the cavity gain and the magnon loss are balanced, i.e., \({\kappa }_{{{{\rm{a}}}}}^{{\prime} }={\kappa }_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}\), for the resonant case of ωm = ωa, which leads to the vanishing of the polariton decay rates, i.e., \({\kappa }_{\pm }=\frac{-{\kappa }_{{{{\rm{a}}}}}^{{\prime} }+{\kappa }_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}}{2}=0\) (see SI for derivation). The significantly reduced polariton decay rates, together with the intrinsically small mechanical damping rate, offers the possibility to observe the polaromechanical strong coupling.

In the experiment, accurate realization of the gain-loss balance is vital to obtain vanishing polariton decay rates. To this end, we alter the length of the pins δl1(2) to vary κ1(2) in order to meet \({\kappa }_{{{{\rm{a}}}}}^{{\prime} }={\kappa }_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}\). Figure 2a shows the output spectrum with κ1/2π = 1.22 MHz and κ2/2π = 1.24 MHz. The two input fields are adjusted to have a zero phase difference Δϕ = 0 and a power ratio q = κ2/κ1 ≈ 1 (see SI). The phase difference and power ratio are tuned via the VPS and VA connected to each port (Fig. 1a). As shown in Fig. 2a, when the frequency of the magnon mode approaches the cavity resonance, the output spectrum exhibits remarkable dips. Due to the monochromaticity of the CPA31,33,46, the output spectrum is nearly zero at the CPA frequency ωCPA. Consequently, we obtain the smallest symmetric decay rates of the two MPs κ±/2π = 7.75 kHz, limited by the regulation precision.

a Output spectrum of the CPA with κ1/2π = 1.22 MHz, κ2/2π = 1.24 MHz, Δϕ = 0, and q ≈ 1. The output spectrum ∣Stot∣2 = ∣ri + tj∣2 (i ≠ j = 1, 2) contains the reflection (transmission) field of the input field loaded at port i (j). ωp is the frequency of the input field. The frequency of the magnon mode is tuned by varying the bias magnetic field B0. b Output spectra of the upper-branch polariton with different magnon frequencies. As the frequency of the polariton approaches the CPA frequency ωCPA, via tuning the magnon frequency (which is tuned from 7.2116 to 7.2104 GHz by reducing B0 from 257.55 to 257.51 mT, as indicated by the red arrow), the polariton decay rate decreases manifesting as a rapid reduction of the output field. The smallest decay rate of the polariton is achieved at the CPA frequency. Black curves are fitting results. c The Wigner time delay \({{{\rm{Re}}}}[\tau (\omega )]\) corresponding to the output spectra in (b). The long time delay ~ 0.2 ms signifies the significantly reduced decay rate of the polariton at the CPA frequency.

To further reduce the decay rate of the polariton, we tune the magnon frequency by varying the bias magnetic field while keeping the cavity frequency fixed. This further reduces the decay rate of one polariton at the price of increasing that of the other (see SI for details)47. In this way, by red-shifting the magnon frequency we achieve the decay rate of the upper-branch polariton κ+/2π = 0.78 kHz, corresponding to an output of − 100.4 dB (Fig. 2b).

The significantly reduced polariton decay rate can be substantiated by calculating the Wigner time delay (WTD)46,48, which characterizes the trapped time of the input field in the resonator (i.e., the MP). The CPA corresponds to the input field being infinitely trapped in the resonator, which can be translated into a diverging WTD. The exact CPA is unmeasurable in the experiment: one can only achieve nearly perfect absorption by improving the control accuracy. This corresponds to a finite WTD, which can be used to estimate the decay rate of the polariton. The WTD is defined as the real part of the complex-valued τ(ω)46,48, i.e.,

where S(ω) is the scattering matrix (see SI for details) and \({\psi }_{{{{\rm{in}}}}}={\left({a}_{1}^{{{{\rm{in}}}}},{a}_{2}^{{{{\rm{in}}}}}\right)}^{{{{\rm{T}}}}}\) is the vector of input fields. In Fig. 2c, we calculate the WTD associated with the output spectra in Fig. 2b. Note that there is a one-to-one correspondence between the spectra in Fig. 2b and the WTD in Fig. 2c at each frequency, and a phase transition of \({{{\rm{Re}}}}[\tau ]\) occurs at the singularity point, i.e., the exact CPA46. At the CPA frequency, we obtain a maximum WTD \(| {{{\rm{Re}}}}\left[\tau ({\omega }_{{{{\rm{CPA}}}}})\right]|=0.2\,{{{\rm{ms}}}}\), corresponding to the decay rate of the polariton \({\kappa }_{+}=1/{{{\rm{Re}}}}[\tau ({\omega }_{{{{\rm{CPA}}}}})]=2\pi \times 0.79\,{{{\rm{kHz}}}}\). This agrees well with the value κ+/2π = 0.78 kHz evaluated using the theory provided in the SI.

Polaromechanical normal-mode splitting

The coupling between the MPs and the mechanical mode essentially originates from the dispersive magnetostrictive (magnon-phonon) interaction, which leads to the linearized Hamiltonian in equation (1). It reveals that the interaction between each polariton and the mechanical mode is analogous to the linearized opto-49 and magnomechanical40 Hamiltonian. This promises similar polaromechanical backaction as the opto- and magnomechanical ones, such as mechanical cooling and amplification41,50. Equation (2) indicates that the effective polaromechanical coupling G± can be enhanced by increasing the magnon excitation number nmag. In the experiment, we adopt a red-detuned microwave field to drive the upper-branch polariton and to keep the scattered mechanical sideband in resonance with the polariton (Fig. 3a). This enhances the magnomechanical anti-Stokes scattering, which cools the mechanical motion, yielding an increased mechanical damping rate41.

a Frequency schematic diagram associated with the measurement. A red-detuned microwave field (red arrow) is used to drive the upper-branch polariton. The detuning is equal to the mechanical frequency, such that the scattered anti-Stokes mechanical sideband is in resonance with the polariton. b Output spectra of the polaromechanical normal modes for different drive powers, with Δpd = ωp − ωd. The corresponding decay rates of the upper-branch polariton κ+/2π are 6.99, 0.25, 1.26, 1.45, 1.42, 1.50 and 0.45 kHz, respectively. We observe three adjacent mechanical modes and focus on the normal-mode splitting associated with the mode of frequency ωb1/2π = 10.9565 MHz (see SI for more details). The other two modes of frequencies ωb2 and ωb3 are identified in the figure. Black solid curves are fitting results. c The pump-enhanced effective polaromechanical coupling strength ∣G+∣ versus drive power. d Effective mechanical damping rate κb,eff versus drive power.

In the first graph of Fig. 3b, a low drive power of − 6.8 dBm leads to a weak coupling ∣G+∣/2π = 3.06 kHz, and the system is in the weak-coupling regime because ∣G+∣ < κ+ = 2π × 6.99 kHz. The anti-Stokes sideband is manifested as the magnomechanically induced transparency39, and the mechanical damping rate is increased from κb/2π = 155 Hz to κb,eff/2π = 250 Hz. By further increasing the drive power, G+ becomes greater than both κ+ and κb,eff. For example in the second graph, ∣G+∣/2π = 5.40 kHz at the power of 2.4 dBm, which is greater than κ+/2π = 0.25 kHz and κb,eff/2π = 255 Hz. The system then enters the polaromechanical strong-coupling regime. From the top to the bottom graph of Fig. 3b, as the power increases from − 6.8 dBm to 16.53 dBm, ∣G+∣ gradually increases to 25.71 kHz (corresponding to a maximum polaromechanical cooperativity C+,b ≡ ∣G+∣2/(κ+κb) ≈ 9.40 × 103), which exhibits a more evident feature of the NMS with the splitting of 2∣G+∣ in the spectra. Similar strong coupling induced NMS has been observed in cavity optomechanics8,9,10. Note that in Fig. 3b, the frequency of the mechanical mode slightly decreases when increasing the power, which is due to the magnon-phonon cross-Kerr effect42 (see SI for more details). In addition, in the graphs under the drive power of 10.4 and 12.28 dBm, we observe the emergence of another weaker, yet distinct normal-mode splitting, which occurs when the polaromechanical strong coupling (associated with the mechanical mode of frequency ωb1) induced normal mode resonates with the mechanical sideband associated with the mechanical mode of frequency ωb3. Figure 3c and d show the corresponding coupling strength ∣G+∣ and the effective mechanical damping rate κb,eff for the drive powers used in Fig. 3b.

Another typical characteristics of the strong coupling is the anti-crossing, i.e., the level repulsion, in the frequency spectrum. In Fig. 4a, we fix the drive frequency at ωd/2π = 7.205365 GHz, and thereby the scattered mechanical sideband is at ωd + ωb = 2π × 7.216313 GHz. By varying the drive power and utilizing the magnon self-Kerr effect, the frequency of the upper-branch polariton can be continuously adjusted. When the polariton frequency is approaching and then passing across the mechanical sideband, the normal-mode spectrum shows an anti-crossing feature due to the polaromechanical strong coupling. It is worth noting that the mechanical sideband is set at the CPA frequency ωCPA, at which the polariton has the smallest decay rate. In addition, we observe a weaker anti-crossing signal beside the main one in Fig. 4a, which results from the strong coupling with the adjacent mechanical mode. Figure 4b shows a significant enhancement of the polaromechanical cooperativity as the frequency of the upper-branch polariton approaches the CPA frequency.

a Output spectrum of the coupled upper-branch polariton and the mechanical mode versus the drive power. Due to the magnon self-Kerr effect, the frequency of the polariton shifts by increasing the drive power (black dashed line). The scattered mechanical sideband is fixed at 7.216313 GHz (white dashed line). During the process of varying the drive power, the cross-Kerr effect causes a 1-kHz mechanical frequency shift, which has a negligible impact. b Polaromechanical cooperativity C+,b versus the frequency of the upper-branch polariton ω+. The cooperativity gets significantly improved when the polariton resonates with the mechanical sideband at the CPA frequency.

Discussion

We have demonstrated strong coupling in a polaromechanical hybrid system, where the mechanical vibration mode is strongly coupled to the driven magnon polariton, whose decay rate is significantly reduced via realizing the coherent perfect absorption. We have measured the corresponding normal-mode splitting at the mechanical sideband, and a high polaromechanical cooperativity C+,b = 9.40 × 103, which is three orders of magnitude higher than the previous experiments39,41,42. This will significantly boost the mechanical cooling efficiency and lower the threshold for achieving phonon lasers in cavity magnomechanics41.

A quantum cooperativity \({C}_{+,{{{\rm{b}}}}}^{Q} \equiv {C} _{+,{{{\rm{b}}}}}/{\bar{n}}_{b} \gg 1\) (\({\bar{n}}_{b}\), the mean thermal phonon number51) can be reached if placing the system at cryogenic temperatures (see SI for estimation). This would enable various quantum applications, e.g., the protocols for preparing macroscopic quantum states of magnons and phonons40,52,53, which are useful in testing the limits of quantum mechanics, and quantum entangled or squeezed states of microwave fields54,55. The strong coupling that we report here can act as a foundation for building multifunctional HQSs involving more different quanta, e.g., by coupling the microwave cavity to superconducting qubits19 and the mechanical vibration to optical photons50. Our results can also be applied to YIG nano-structures56 or planar configurations57,58,59, which would enable the integration of magnonic devices on a chip and thus improve the functionality of the HQS to be used in quantum information processing or quantum sensing.

Methods

The magnonic system shows an excellent tunability in its resonance frequency. In this work, we utilize two methods to adjust the frequency of the magnon mode. One is to adjust the external bias magnetic field via ωm = γB0; the other is to use the magnon self-Kerr effect, reflected in the frequency of the driven magnon mode \({\tilde{\omega }}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}\approx {\omega }_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}+2{K}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}| M{| }^{2}\) (see SI for details). Both methods can achieve the same effect. When the strong drive field is absent, we alter the external bias magnetic field to adjust the magnon frequency, as done in Fig. 2a. When the drive field is applied, we alter the power of the drive field to change the magnon excitation number, which adjusts the magnon frequency due to the self-Kerr effect, as done in Fig. 4a.

In the experiment, we measure a negative self-Kerr coefficient Km/2π = − 7.4 nHz. The magnon mode experiences a negative frequency shift by increasing the drive power. To compensate for this effect, Fig. 3b is measured under different initial frequencies of the upper-branch polariton. From the top to the bottom graph, we increase the external magnetic field B0 to have a higher initial magnon frequency (without applying the drive), and thus a higher initial frequency of the upper-branch polariton. This compensates the negative frequency shift of the magnon mode when the drive is applied. On the other hand, the cross-Kerr effect results in a frequency shift of the mechanical mode, and the magnomechanical coupling also leads to the modification of the CPA conditions, i.e., a shift of the CPA frequency (see Secs. IV and VI of SI). In the measurements of Fig. 3b, we adjust the drive frequency considering the combined effect of the above two factors to ensure that, in the process of measuring the output spectrum at various drive powers, the anti-Stokes mechanical sideband always resonates with the polariton at the CPA frequency.

Data availability

The datasets used to generate the plots in the paper are available on Zenodo (https://zenodo.org/records/12732420). All other data that support the plots within this paper and other findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Xiang, Z.-L., Ashhab, S., You, J. Q. & Nori, F. Hybrid quantum circuits: Superconducting circuits interacting with other quantum systems. Rev. Mod. Phys. 85, 623 (2013).

Kurizki, G. et al. Quantum technologies with hybrid systems. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 3866 (2015).

Clerk, A. A., Lehnert, K. W., Bertet, P., Petta, J. R. & Nakamura, Y. Hybrid quantum systems with circuit quantum electrodynamics. Nat. Phys. 16, 257 (2020).

Schleier-Smith, M. Editorial: Hybridizing Quantum Physics and Engineering. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 100001 (2016).

Thompson, R. J., Rempe, G. & Kimble, H. J. Observation of normal-mode splitting for an atom in an optical cavity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 68, 1132 (1992).

Wallraff, A. et al. Strong coupling of a single photon to a superconducting qubit using circuit quantum electrodynamics. Nature 431, 162 (2004).

Weisbuch, C., Nishioka, M., Ishikawa, A. & Arakawa, Y. Observation of the coupled exciton-photon mode splitting in a semiconductor quantum microcavity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 69, 3314 (1992).

Gröblacher, S., Hammerer, K., Vanner, M. R. & Aspelmeyer, M. Observation of strong coupling between a micromechanical resonator and an optical cavity field. Nature 460, 724 (2009).

Teufel, J. D. et al. Circuit cavity electromechanics in the strong-coupling regime. Nature 471, 204 (2011).

Verhagen, E., Deléglise, S., Weis, S., Schliesser, A. & Kippenberg, T. J. Quantum-coherent coupling of a mechanical oscillator to an optical cavity mode. Nature 482, 63 (2012).

O’Connell, A. D. et al. Quantum ground state and single-phonon control of a mechanical resonator. Nature 464, 697 (2010).

Chu, Y. et al. Quantum acoustics with superconducting qubits. Science 358, 199 (2017).

Satzinger, K. J. et al. Quantum control of surface acoustic wave phonons. Nature 563, 661 (2018).

Chu, Y. et al. Creation and control of multi-phonon Fock states in a bulk acoustic-wave resonator. Nature 563, 666 (2018).

Mirhosseini, M., Sipahigil, A., Kalaee, M. & Painter, O. Superconducting qubit to optical photon transduction. Nature 588, 599 (2020).

Bennett, S. D., Cockins, L., Miyahara, Y., Grütter, P. & Clerk, A. A. Strong electromechanical coupling of an atomic force microscope cantilever to a quantum dot. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 017203 (2010).

Karg, T. M. et al. Light-mediated strong coupling between a mechanical oscillator and atomic spins 1 meter apart. Science 369, 174 (2020).

Schwab, K. C. & Roukes, M. L. Putting mechanics into quantum mechanics. Phys. Today 58, 36 (2005).

Lachance-Quirion, D., Tabuchi, Y., Gloppe, A., Usami, K. & Nakamura, Y. Hybrid quantum systems based on magnonics. Appl. Phys. Exp. 12, 070101 (2019).

Awschalom, D. D. et al. Quantum engineering with hybrid magnonic systems and materials. IEEE Trans. Quantum Eng. 2, 1 (2021).

Li, Y. et al. Hybrid magnonics: physics, circuits and applications for coherent information processing. J. Appl. Phys. 128, 130902 (2020).

Li, J., Wang, Y.-P., Wu, W.-J., Zhu, S.-Y. & You, J. Q. Quantum Network with Magnonic and Mechanical Nodes. PRX Quantum 2, 040344 (2021).

Chumak, A. V. et al. Advances in magnetics roadmap on spin-wave computing. IEEE Trans. Magn. 58, 1 (2022).

Yuan, H. Y., Cao, Y., Kamra, A., Duine, R. A. & Yan, P. Quantum magnonics: When magnon spintronics meets quantum information science. Phys. Rep. 965, 1 (2022).

Rameshti, B. Z. et al. Cavity magnonics. Phys. Rep. 979, 1 (2022).

Pirro, P., Vasyuchka, V. I., Serga, A. A. & Hillebrands, B. Advances in coherent magnonics. Nat. Rev. Mater. 6, 1114 (2021).

Latini, S. et al. Phonoritons as hybridized exciton-photon-phonon excitations in a monolayer h-BN optical cavity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 227401 (2021).

Kuznetsov, A. S. et al. Microcavity phonoritons a coherent optical to microwave interface. Nat. Commun. 14, 5470 (2023).

Santos, P. V. & Fainstein, A. Polaromechanics: polaritonics meets optomechanics. Opt. Mater. Exp. 13, 1974 (2023).

Basov, D. N., Asenjo-Garcia, A., Schuck, P. J., Zhu, X. & Rubio, A. Polariton panorama. Nanophotonics 10, 549 (2021).

Chong, Y. D., Ge, L., Cao, H. & Stone, A. D. Coherent perfect absorbers: time-reversed lasers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 053901 (2010).

Wan, W. et al. Time-reversed lasing and interferometric control of absorption. Science 331, 889 (2011).

Noh, H., Chong, Y. D., Stone, A. D. & Cao, H. Perfect coupling of light to surface plasmons by coherent absorption. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 186805 (2012).

Wang, C., Sweeney, W. R., Stone, A. D. & Yang, L. Coherent perfect absorption at an exceptional point. Science 373, 1261 (2021).

Zhang, D., Luo, X. Q., Wang, Y.-P., Li, T. F. & You, J. Q. Observation of the exceptional point in cavity magnon-polaritons. Nat. Commun. 8, 1368 (2017).

Huebl, H. et al. High cooperativity in coupled microwave resonator ferrimagnetic insulator hybrids. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 127003 (2013).

Tabuchi, Y. et al. Hybridizing ferromagnetic magnons and microwave photons in the quantum limit. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 083603 (2014).

Zhang, X., Zou, C. L., Jiang, L. & Tang, H. X. Strongly coupled magnons and cavity microwave photons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 156401 (2014).

Zhang, X., Zou, C.-L., Jiang, L. & Tang, H. X. Cavity magnomechanics. Sci. Adv. 2, e1501286 (2016).

Li, J., Zhu, S.-Y. & Agarwal, G. S. Magnon-photon-phonon entanglement in cavity magnomechanics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 203601 (2018).

Potts, C. A., Varga, E., Bittencourt, V., Kusminskiy, S. V. & Davis, J. P. Dynamical backaction magnomechanics. Phys. Rev. X 11, 031053 (2021).

Shen, R.-C., Li, J., Fan, Z.-Y., Wang, Y.-P. & You, J. Q. Mechanical Bistability in Kerr-modified Cavity Magnomechanics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 129, 1123601 (2022).

Sesin, P. et al. Giant optomechanical coupling and dephasing protection with cavity exciton-polaritons. Phys. Rev. Res. 5, L042035 (2023).

Anderson, P. W. & Suhl, H. Instability in the motion of ferromagnets at high microwave power levels. Phys. Rev. 100, 1788 (1955).

Gardiner, C. W. & Collett, M. J. Input and output in damped quantum systems: Quantum stochastic differential equations and the master equation. Phys. Rev. A 31, 3761 (1985).

del Hougne, P., Yeo, K. B., Besnier, P. & Davy, M. On-demand coherent perfect absorption in complex scattering systems: Time delay divergence and enhanced sensitivity to perturbations. Laser Photonics Rev. 15, 2000471 (2021).

Sermage, B. et al. Time-resolved spontaneous emission of excitons in a microcavity: Behavior of the individual exciton-photon mixed states. Phys. Rev. B 53, 16516 (1996).

Chen, L., Anlage, S. M. & Fyodorov, Y. V. Generalization of Wigner time delay to subunitary scattering systems. Phys. Rev. E 103, L050203 (2021).

Aspelmeyer, M., Gröblacher, S., Hammerer, K. & Kiesel, N. Quantum optomechanics—throwing a glance. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 27, A189 (2010).

Aspelmeyer, M., Kippenberg, T. J. & Marquardt, F. Cavity optomechanics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 86, 1391 (2014).

Ren, H. et al. Two-dimensional optomechanical crystal cavity with high quantum cooperativity. Nat. Commun. 11, 3373 (2020).

Li, J., Zhu, S.-Y. & Agarwal, G. S. Squeezed states of magnons and phonons in cavity magnomechanics. Phys. Rev. A 99, 021801(R) (2019).

Li, J. & Zhu, S.-Y. Entangling two magnon modes via magnetostrictive interaction. N. J. Phys. 21, 085001 (2019).

Yu, M., Shen, H. & Li, J. Magnetostrictively induced stationary entanglement between two microwave fields. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 213604 (2020).

Li, J., Wang, Y.-P., You, J. Q. & Zhu, S.-Y. Squeezing microwaves by magnetostriction. Natl Sci. Rev. 10, nwac247 (2023).

Heyroth, F. et al. Monocrystalline freestanding three-dimensional yttrium-iron-garnet magnon nanoresonators. Phys. Rev. Appl. 12, 054031 (2019).

Xu, J. et al. Coherent pulse echo in hybrid magnonics with multimode phonons. Phys. Rev. Appl. 16, 024009 (2021).

Li, Y. et al. Strong coupling between magnons and microwave photons in on-chip ferromagnet-superconductor thin-film devices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 107701 (2019).

Hatanaka, D. et al. On-chip coherent transduction between magnons and acoustic phonons in cavity magnomechanics. Phys. Rev. Appl. 17, 034024 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Liu Qiu and Yanhao Tang for useful discussions. This work was supported by National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFA1405200 to J.Q.Y., 2024YFA1408900 to J.L., 2023YFA1406703 to Y.P.W.), National Natural Science Foundation of China (92265202, 11934010 to J.Q.Y., 12474365 to J.L., 12174329 to Y.P.W.), the Innovation Program for Quantum Science and Technology (2021ZD0300200 to S.Y.Z.), and Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (LR25A050001 to J.L.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.C.S. performed the measurements and R.C.S. and X.Z. developed the theory. The measurement and theory related to the polariton-mechanics coupling is under the supervision of J.L. Y.M.S. and W.J.W. provided experimental support. R.C.S., J.L., Y.P.W., S.Y.Z. and J.Q.Y. analyzed the data. R.C.S., J.L. and J.Q.Y. wrote the manuscript with the input and comment from all co-authors. J.Q.Y. supervised the project.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Ryo Sasaki, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shen, RC., Li, J., Sun, YM. et al. Cavity-magnon polaritons strongly coupled to phonons. Nat Commun 16, 5652 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60799-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60799-x

This article is cited by

-

Magnon-polaron control in a surface magnetoacoustic wave resonator

Nature Communications (2025)