Abstract

The E2F transcription factors constitute a core transcriptional network that governs cell division and oncogenesis in multi-cellular organisms, although their molecular mechanisms remain incompletely understood. Here, we show that elevated expression of the transcription factor FOXK1 promotes transcription of E2F target genes and cellular transformation. High expression of FOXK1 in patient tumors is also strongly correlated with E2F gene expression. Mechanistically, we demonstrate that FOXK1 is O-GlcNAcylated, and loss of this modification impairs FOXK1 ability to promote cell proliferation and tumor growth. We also show that expression of FOXK1 O-GlcNAcylation-defective mutants results in reduced recruitment of the H2AK119 deubiquitinase and tumor suppressor BAP1 to E2F target genes. This event is associated with a transcriptional repressive chromatin environment and reduced cell proliferation. Our results define an essential role of FOXK1 O-GlcNAcylation in co-opting the tumor suppressor BAP1 to promote cancer cell progression through orchestration of the E2F pathway.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The E2F pathway controls a transcriptional network that constitutes a cardinal point of cell division and is essential to life in higher eukaryotes. The E2F gene expression program, often referred to as E2F target genes, is highly conserved during evolution and act at the crossroads of cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis and stress responses1. A family of eight E2F transcription factors work cooperatively or antagonistically to orchestrate the expression of genes necessary for DNA replication and cell cycle progression2. Hence, an intricate balance between positive and negative regulators and feedback loops governs the E2F pathway and the cell proliferative capacity3,4. The E2F circuitry become perverted upon loss of tumor suppressors or activation/overexpression of oncogenes, both of which underlie tumor initiation and progression3,4.

FOXK1 and FOXK2, members of the Forkhead box (FOX) family of transcription factors, are highly conserved and ubiquitously expressed in vertebrates. These factors exhibit high sequence homology and a similar domain structure5. They can be notably distinguished by the presence in their structure of both a DNA-binding Forkhead (FH) and a phospho-threonine binding Forkhead-associated (FHA) domains5. Although their mechanisms of action are not fully established, FOXK1 and FOXK2 appear to play critical roles in cell proliferation, stem cell function, cell migration and differentiation6,7. These factors have also recently emerged as important regulators of cell metabolism, through transcriptional regulation of gene expression programs that orchestrate autophagy8, aerobic glycolysis9, insulin response10 and mTOR signaling11.

While FOXK1 and FOXK2 share several overlapping roles in normal biological processes, their distinct functions and the consequences of their deregulated transcriptional activity in diseases, particularly cancer, remain incompletely understood12,13,14,15,16,17,18. Emerging evidence, however, suggests that these factors might exert specific functions during cancer development and progression19,20,21,22,23,24,25. For instance, amplification of FOXK1 correlates with increased cell proliferation, as well as cancer progression26. In contrast, confounding results have been obtained on FOXK2 dysregulation in cancer, and this factor might have both oncogenic and tumor suppressor properties12. It is currently unclear how the functions of FOXK1 and FOXK2 can be separated at the molecular level. Both FOXK1 and FOXK2 use their FHA domain to interact with the histone H2AK119ub deubiquitinase BAP1, through a single phosphorylated threonine located in the intrinsically disordered region of BAP127,28. FOXK1 and FOXK2 are responsible, at least partly, for BAP1 recruitment to chromatin, and a phosphorylation-defective mutant of this deubiquitinase (BAP1T493A) loses its interaction with FOXK1 and FOXK2. Of note, while FOXK1 and FOXK2 are components of the BAP1 complexes, they can also interact with repressors such as SIN3A and HDAC3 or activators such as AP1, although the exact molecular dynamics of their interactions remain to be fully elucidated8,24,29.

A long-standing question regarding FOXK1 and FOXK2 is how these factors dynamically interact with other chromatin-associated factors to exert their shared or distinct functions in coordinating transcriptional events and downstream biological processes. Here, we describe an important link between FOXK1 and the E2F pathway and reveal O-GlcNAcylation of FOXK1, but not FOXK2, as a molecular switch that distinctly promotes cell proliferation and oncogenesis. We demonstrate that FOXK1, but not FOXK2, activates E2F target genes transcription, enhancing proliferation and delaying cellular senescence in normal cells. Elevated FOXK1 expression promotes cellular transformation and tumor progression. We also demonstrate that high FOXK1 expression levels in tumors are associated with increased expression of E2F target genes and poor patient prognosis. We identify FOXK1, but not FOXK2, as a target of O-GlcNAcylation, with its modification reaching the highest levels at the G1/S transition, coinciding with E2F pathway activation. Moreover, this modification is dynamically regulated in response to fluctuations in extracellular glucose concentration, linking FOXK1 activity to nutrient sensing and metabolic pathways. Loss of FOXK1 O-GlcNAcylation impairs its ability to drive proliferation, transformation, and tumor growth. Finally, we show that FOXK1 O-GlcNAcylation promotes its interaction with BAP1 and recruitment to E2F target genes to regulate their expression and cell proliferation. These findings highlight O-GlcNAcylation as a critical regulator of FOXK1 function in controlling cell cycle and tumor progression.

Results

FOXK1, but not FOXK2, promotes cell proliferation and displays potent oncogenic promoting activities

We first examined FOXK1 and FOXK2 mRNA levels in normal and cancer tissues, noting a general trend towards higher expression in tumors for both transcription factors (Supplementary Fig. 1a, b). Interestingly, the expression of FOXK1 closely correlated with that of FOXK2 in normal tissues when compared to other related FOX genes (Supplementary Fig. 1c). Moreover, the correlation between FOXK1 and FOXK2 becomes considerably weaker in cancer tissues (Supplementary Fig. 1c). High levels of FOXK1 mRNA expression are associated with poor patient survival for both female and male patients. In contrast, FOXK2 expression levels showed no association with survival outcomes in females. However, male patients exhibited a slight, but statistically significant reduction in survival under conditions of high FOXK2 expression (Supplementary Fig. 1d).

To investigate the potential oncogenic properties of FOXK1 and FOXK2, we first sought to explore the impact of their enforced expression in the context of normal human cell cycle progression. IMR90 normal diploid fibroblasts expressing FOXK1 or FOXK2 show approximately a four-fold or a ten-fold increase, respectively, of their protein levels relative to their endogenous counterparts (Supplementary Fig. 2a). Moreover, detection of the FOXK1 and FOXK2 tagged forms with the anti-Flag antibody indicated that the expression of FOXK1 is about 1.5-fold higher than that of FOXK2 (Supplementary Fig. 2a). Notably, IMR90 primary fibroblasts expressing FOXK1 become smaller and grow faster than control vector or FOXK2 conditions (Fig. 1a–c). Of note, viral titration experiments indicated that the effect of FOXK1 on cell proliferation was maintained even when half the amount of FOXK1 virus preparation, FOXK11/2, was used to achieve similar expression levels as FOXK2 (Supplementary Fig. 2b). We then synchronized IMR90 cells expressing FOXK1 or FOXK2, with a combination of contact inhibition and serum deprivation to induce cell cycle exit, then followed cell cycle re-entry by re-plating the arrested cells at low density. FACS analysis showed that cells overexpressing FOXK1, but not FOXK2 or empty vector, can rapidly progress into S phase (Fig. 1d), consistent with an increased number of EdU- positive cells (Fig. 1e). Moreover, following three to four weeks of culture post-viral transduction, we observed a lower number of senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-gal)-positive cells in FOXK1 expression conditions comparatively to those of FOXK2 or control vector (Fig. 1f), suggesting an extended replicative capacity of normal cells upon expression of FOXK1. Furthermore, immunostaining for PML bodies, known to be associated with cellular senescence30,31, indicated that FOXK1-expressing cells display fewer number of senescence–associated PML bodies compared to FOXK2 or control vector conditions (Fig. 1g). When we computed the numbers of IMR90 cells based on FOXK1 and FOXK2 expression levels (low versus high immunofluorescence signal intensity), we noticed that cells with higher FOXK1 expression (by signal intensity) contains fewer numbers of PML foci per cell, consistent with our results indicating that elevated expression of FOXK1 delays the induction of cellular senescence (Fig. 1h). In contrast, higher number of PML bodies per cell correlated with higher FOXK2 expression levels (Fig. 1h). Of note, we also observed an increase in cellular proliferation following expression of FOXK1, but not FOXK2, in various cancer cells including osteosarcoma (U2OS) and colorectal carcinoma (HCT116) (Supplementary Fig. 2c).

a, b Phase contrast imaging and cell size of IMR90 cells stably expressing empty vector, FOXK1 or FOXK2. The results are representative of four experiments. Box plots display the distribution of individual cell surface area (μm²) for each condition. The number of cells quantified for each condition is: Vector = 343, FOXK1 = 1252, FOXK2 = 417. The center line represents the median. The box extends from the 25th to the 75th percentile (interquartile range, IQR). The whiskers extend to the most extreme non-outlier values within 1.5×IQR. Outliers are not shown. Representative of three independent experiments. c Cell counts of IMR90 cells expressing empty vector, FOXK1 or FOXK2. Data points are represented as a cumulative count (n = 3 independent experiments). d FACS analysis of DNA content following synchronization and release of IMR90 cells expressing FOXK1 or FOXK2. The arrow indicates the emerging S phase peak. The percentage indicates the number of cells moving towards S/G2. The results are representative of three independent experiments. At the end of the experiments (c), cells were used for further characterization shown in (e–h). e Analysis of EdU incorporation by immunofluorescence and cell counting of EdU positive IMR90 control cells or cells expressing FOXK1 or FOXK2 (n = 3 independent experiments). f Senescence-associated β-galactosidase staining of IMR90 control cells or expressing FOXK1 or FOXK2. Cells stained in blue were counted and used to calculate the percentage of senescent cells (n = 3 independent experiments). g IMR90 cells expressing FOXK1 or FOXK2 were fixed for immunofluorescence staining of PML bodies (n = 3 independent experiments). Control and FOXK1 expressing cells were stained with anti-FOXK1 antibody, FOXK2 expressing cells were stained with anti-FOXK2 antibody. Cells displaying PML bodies in each condition were counted and plotted in the right panel. h Quantification of the number of PML bodies in cells with high or low expression of FOXK1 or FOXK2 (n = 75 total nuclei counted for PML bodies from three independent experiments). Data are represented as a scatter plot. i Cell colony counting of control IMR90 cells or overexpressing FOXK1 or FOXK2 along with different combinations of oncogenes (n = 4 independent experiments, except for FOXK2: n = 3 independent experiments). j Representative images of normal versus transformed cells. k Tumor penetrance of IMR90 cells expressing RASG12V and E1A and either empty vector, FOXK1 or FOXK2. The same number of cells were injected into the flank of nude mice. The experiment was terminated when the tumors reached the limit point (n = 4 injected mice). l Tumor latency representing the time between cell engraftment and appearance of tumors that reached at least 0.1 cm3 from IMR90 cells expressing RASG12V and E1A, and either empty vector, FOXK1 or FOXK2 (n = 4 injected mice, only penetrant tumors are represented by dots. By the end of the experiment, only three tumors out of four injections grew in empty vector condition). m Tumor volume of IMR90 cells expressing RASG12V and E1A and either empty vector, FOXK1 or FOXK2 at the end of the experiment (n = 4 injected mice). n Representative images of the tumors before and after extraction for final size measurement. Statistics: Data are represented as mean ± SEM (c, e, f, g, i, l, m). One-way or Two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons (c, f, g, h, i) or Dunnett’s (e, l, m). All tests were two-sided, and adjustments were made for multiple comparisons. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001, ns non-significant. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To better define FOXK1 oncogenic properties, IMR90 cells were transformed by co-expressing different oncogenes in combination with FOXK1 or FOXK2. As a positive control of transformation, we co-expressed RASG12V, HDM2, and E1A, which is a classical combination of oncogenes known to transform normal human diploid fibroblasts32,33,34. Expression of FOXK1 or FOXK2, along with RASG12V, was not sufficient to induce colony formation (Fig. 1i). RASG12V induces premature senescence in IMR90 cells, a phenomenon known as oncogene-induced senescence (OIS) that results from increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and DNA damage, as a consequence of sustained growth signaling35,36. RASG12V-induced cellular senescence can be bypassed by specific oncogene combinations37. Accordingly, overexpressing FOXK1 with RASG12V, HDM2, and E1A lead to a greater number of colonies compared to FOXK2 or empty vector conditions (Fig. 1i). These colonies acquire a rounded cell shape, in contrast to the fibroblast-like shape (Fig. 1j), and can be expanded indefinitely. These results indicate that FOXK1 could further enhance the transformation potential of an otherwise potent oncogenic combination. In addition, expressing FOXK1 in cells with minimal combinations of oncogenes, such as HDM2 only, E1A only, HDM2 + E1A, or E1A + RASG12V, increased the number of colonies compared to their respective controls (Fig. 1i). Of note, while HDM2 and FOXK1 combination can give rise to colonies, the addition of RASG12V supresses this effect, likely due to its potent OIS effect on primary cells. Next, we investigated whether the formation of cell colonies conferred tumorigenic potential, enabling them to generate tumors when injected into immunodeficient mice. Notably, co-expressing FOXK1 with E1A and RASG12V could rapidly generate tumors with a high penetrance and a lower tumor latency than control cells or cells overexpressing FOXK2 with E1A and RASG12V (Fig. 1k–n). Moreover, cells expressing FOXK1 give rise to bigger tumors than those expressing FOXK2 or control vector (Fig. 1m, n). Altogether, these results indicate that elevated expression of FOXK1 is observed in cancer and that this transcription factor has potent cell proliferation and transformation promoting activities.

FOXK1 is a major positive regulator of the E2F pathway

To define the mechanism underlying FOXK1-dependent oncogenic properties, transcriptomic (RNA-seq) analyses were conducted on IMR90 cells expressing either control vector, FOXK1 or FOXK2. Viral transduction conditions were performed to ensure equivalent protein levels between the different Flag-tagged constructs at the time of harvest (Supplementary Fig. 3a). In these conditions, FOXK1 and FOXK2 transcripts were overexpressed approximately 4.7-fold and 14.5-fold respectively, compared to the control vector condition (Supplementary Fig. 3b). Furthermore, we analyzed samples from TCGA cancer datasets, comparing those with the highest (top 10%) and lowest (bottom 10%) levels of FOXK1 or FOXK2 expression. We observed that, on average, FOXK1 transcript counts varied about 8-fold between the two groups (high versus low), while FOXK2 transcript could vary by around 7-fold (Supplementary Fig. 3c). These findings indicate that FOXK1 overexpression levels, observed in IMR90 cells, are reflective of the variations found in cancer contexts. Importantly, FOXK1 expression in IMR90 cells lead to differential expression of more than 2000 genes with 902 upregulated and 1112 downregulated compared to control, as well as about 475 genes with 286 upregulated and 189 downregulated when comparing FOXK1 to FOXK2 (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 3d). Gene ontology (GO) analysis revealed that FOXK1-associated transcriptional program is linked to several pathways regulating DNA replication and cell cycle progression (Fig. 2b). Notably, gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) revealed that FOXK1 expression results in the activation of the E2F pathway (Fig. 2b, c). Of the 200 E2F-regulated genes, we observed that 60 (30%) were increased in FOXK1-expressing cells, thus linking the observed enhanced cell proliferation to the upregulation of E2F target genes (Fig. 2d). In contrast, genes upregulated in FOXK2-overexpressing cells, compared to FOXK1, were associated with developmental processes and cellular differentiation (Supplementary Fig. 3d, cluster 4). Moreover, genes differentially regulated in FOXK2-overexpressing cells, compared to control condition, were associated with cell differentiation, migration, and adhesion (Supplementary Fig. 3e, f). FOXK1 and FOXK2 were previously shown to repress the autophagy pathway8 and, accordingly, we observed that genes associated with the regulation of autophagy were enriched in control cells compared to FOXK1 and FOXK2 (Supplementary Fig. 3g). Thus, FOXK1 and FOXK2 control overlapping and specific transcriptional programs in cells. In keeping with FOXK1 regulation of the E2F pathway, our transcriptomic analysis showed upregulation of E2F1 itself, as well as several E2Fs target genes such as FOXM1, cyclin A, cyclin B1/2, CDC25C and MCM3 in FOXK1-overexpressing cells compared to FOXK2. We validated that FOXK1 promotes the expression of E2F1 and some of its known targets such as cyclin A, MCM3 and CDC6 (Fig. 2e), which was also observed at the protein levels (Fig. 2f). Of note, FOXK2 overexpression unlike FOXK1, results in a consistent induction of mRNA and protein levels of p21, a negative regulator of the cell cycle (Fig. 2e, f). We then exposed FOXK1-expressing IMR90 cells to the CDK4/CDK6 inhibitor Palbociclib38, which markedly suppressed cell proliferation, reducing it to levels comparable to those of vector-expressing cells (Fig. 2g). This result indicates that the observed proliferative enhancement induced by FOXK1 expression is primarily driven by the E2F pathway.

a MA Plot representing the mean expression against the fold change of genes when comparing FOXK1 with empty vector or FOXK1 with FOXK2 conditions. For each graph, genes in red are up-regulated in FOXK1 condition. b Gene ontology (GO) analysis using Enrichr (MSigDB and GO:BP databases) was performed on genes differentially regulated between FOXK1 and FOXK2 conditions. c Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) performed on genes deregulated in FOXK1 compared to FOXK2 condition. d Heatmap representing the transcript count in IMR90 cells from control, FOXK1 and FOXK2 conditions on all the E2F target genes defined by the hallmark of molecular signatures database (200 genes). Among the 200 E2F genes, FOXK1 upregulates 60 of them. Transcript counts were normalized using z-score and presented as heatmap. e Validation of RNA-seq data by quantifying mRNA of genes differentially regulated by qRT-PCR (n = 4 independent experiments). f Western blotting showing increased expression of some E2F targets following FOXK1 or FOXK2 overexpression (representative of three independent experiments). g IMR90 cells expressing FOXK1 or control cells were treated with the CDK4/6 inhibitor Palbociclib (5 µM) and monitored for growth using Incucyte imaging (n = 3 independent experiments). h Kaplan–Meier survival curve of TCGA cancer patients with or without FOXK1 amplification (based on GISTIC score) with separate analysis for male (number of patients without amplification = 3043, and with amplification = 49) and female patients (number of patients without amplification = 2500, and with amplification = 67) (data sourced from cBioportal). i Heat map showing z-scores of transcript counts for 200 E2F target genes, categorized into samples with the highest (top 10%) and lowest (bottom 10%) FOXK1 expression levels from TCGA cancer patients with separate analysis for male and female patients. j GSEA analysis conducted on differentially expressed genes when comparing TCGA samples with the highest and lowest FOXK1 expression levels. Statistics: Data are represented as mean ± SEM (e, g). Two-way ANOVA with two-sided tests followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test for adjustment (e, g). Normalized enrichment score (NES) and p value were computed using GSEA software (c, j). A two-sided log-rank test was performed for survival analysis (h). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.001, ns non-significant. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

FOXK1 amplification is observed in many solid cancers and its amplification is associated with decreased survival of patients in both females and males (Fig. 2h). Next, we extracted mRNA expression from TCGA database, segregating it into two groups: the top 10% displaying the highest FOXK1 levels and the bottom 10% with the lowest FOXK1 expression. Samples with elevated FOXK1 mRNA showed pronounced expression of the 200 E2F target genes in both female and male patients (Fig. 2i). Moreover, our differential gene expression analysis revealed a strong association between FOXK1 expression and the E2F pathway in cancer (Fig. 2j).

Our results indicate that FOXK1 expression is associated with the induction of the E2F pathway and could explain why cells grow faster and are more susceptible to oncogenic transformation upon enforced expression of this transcription factor. This association is further mirrored in cancer tissues, where samples with the highest levels of FOXK1 transcripts exhibit a pronounced activation of the E2F pathway, reinforcing the link between FOXK1 expression and oncogenesis.

Pervasive occupancy of FOXK1 and FOXK2 in the E2F genomic circuit

To gain further insights into how FOXK1 and FOXK2 regulate gene expression, by notably discerning their common and specific target genes, we analyzed their genome occupancy in several cell lines using ChIP-seq. Remarkably, endogenous FOXK1 and FOXK2 exhibited similar chromatin recruitment patterns in IMR90 cells, co-localizing predominantly at the same promoters (Fig. 3a, b). FOXK1 and FOXK2 antibody specificity was rigorously validated by protein depletion and overexpression (Supplementary Fig. 4a, b, c). Our data indicate that no cross-reactivity was observed between the antibodies used to target endogenous FOXK1 or FOXK2 proteins.

a Heatmap and profile representing the occupancy of endogenous FOXK1 and FOXK2 on gene promoter regions. Promoter regions were obtained from HOMER (31713), and peaks were centered within 6Kb (±3 kb) distance and oriented based on RefSeq direction (n = 1). b Venn diagram representing overlapping peaks in promoters and distal regions between endogenous FOXK1 and FOXK2 in IMR90 cells. c Gene ontology (GO) analysis performed on promoters containing FOXK1. d Bar-plot representing the repartition of endogenous (endo) and exogenous (3 Flag tagged) FOXK1 and FOXK2 ChIP-seq peaks on the genome of K562 (n = 1), IMR90 (n = 1 for endogenous and n = 1 for exogenous), or U2OS (n = 1) cells. e Venn diagram showing intersecting FOXK1 (Flag ChIP-seq) peaks found in promoters in IMR90, K562 and U2OS cells. f GO analysis performed on common 7312 promoters containing FOXK1 in IMR90, K562, and U2OS cells. g Diagram explaining Re-ChIP performed in U2OS cells. h Re-ChIP-qPCR analysis of sequential FOXK1 and FOXK2 chromatin immunoprecipitation (FOXK1 followed by IgG or FOXK2, and FOXK2 followed by IgG or FOXK1) on the promoters of E2F1, MCM6, and Cyclin A (n = 2 independent experiments). i Heatmap and profile of FOXK1 and FOXK2 recruitment to promoters (from HOMER) in blocked G0 cells and 18 h following release (n = 1). j Comparison of FOXK1 (y axis) and FOXK2 (x axis) spike-in normalized read count at common peaks from Cut&Run experiment performed in IMR90 cells blocked in G0 and 18 hours following the release of cells in the cell cycle. The dashed line splits the scatter plot into two regions. Points above the line indicate higher values for FOXK1 peaks, and points below higher values for FOXK2. The box plots in the right panel show spike-in normalized read count signal quantification at common FOXK1 and FOXK2 peaks in both cell cycle phases (two technical replicates were merged). Box plots display the normalized read counts for each condition. The center line represents the median. The box extends from the 25th to the 75th percentile (interquartile range, IQR). The whiskers extend to the most extreme non-outlier values within 1.5×IQR. Outliers are not shown. Statistics: Data are represented as mean ± SEM (h). Two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons (j). GO enrichment analysis was performed using Enrichr. Statistical significance was assessed using Fisher’s exact test, and odds ratios (OR) were computed (c, f). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

ChIP-seq performed on IMR90 cells overexpressing Flag-tagged forms of FOXK1 and FOXK2 showed similar enrichment patterns as the corresponding endogenous proteins (Supplementary Fig. 4d, e). Next, GO analysis of FOXK1 and FOXK2-occupied promoters in these cells revealed several cellular processes linked to FOXK1 or FOXK2 functions, including the E2F pathway (Fig. 3c). Further analysis of FOXK1 and FOXK2 genome occupancy across additional model cell lines indicated a consistent proportion of binding events in promoter regions with no redistribution of FOXK1 or FOXK2 binding sites upon their overexpression (Fig. 3d). Promoters commonly targeted by FOXK1 in U2OS, K562, and IMR90 (7312 in total) were also associated with E2F and cell cycle regulation, hinting at a conserved role across different cell types (Fig. 3e, f and Supplementary Fig. 4f). To better understand the dynamics of chromatin recruitment between FOXK1 and FOXK2, we performed a tandem ChIP analysis (Re-ChIP) for these factors to analyze their simultaneous co-occupancy at gene regulatory regions (Fig. 3g). Our results suggest a competitive interaction between FOXK1 and FOXK2 at E2F target genes. Specifically, FOXK1 was enriched at E2F1, MCM6, and cyclin A promoters, while no enrichment of FOXK2 was detected in FOXK1 ChIP material (Fig. 3h). Similarly, FOXK2 ChIP did not show any FOXK1 enrichment, suggesting that FOXK1 and FOXK2 recruitment to chromatin is temporally regulated. We further analyzed FOXK1 and FOXK2 recruitment to specific promoters in IMR90 cells blocked in G0 and upon release into the cell cycle. Regions bound by both FOXK1 and FOXK2 in G0-arrested cells displayed relatively higher signal for FOXK2, whereas a marked increase in FOXK1 binding was observed 18 h post release, suggesting that FOXK1 is predominantly recruited to chromatin as cells re-enter the cell cycle (Fig. 3i, j). We also examined FOXK1 and FOXK2 chromatin recruitment in U2OS cells synchronized by a thymidine double block or nocodazole treatment (Supplementary Fig. 4g). We found that while the recruitment of both FOXK1 and FOXK2 increased when cells engage S phase, FOXK1 showed a higher chromatin enrichment compared to FOXK2 (Supplementary Fig. 4g). Of note, both proteins show a sharp decrease of their chromatin association during M phase, suggesting that they might be excluded from chromatin when cells enter mitosis. We concluded that FOXK1 and FOXK2 compete for binding to their target genes and that their residence time on chromatin is governed, at least partly, by cell cycle regulation.

To further examine the role of FOXK1 and FOXK2 in E2F regulation, we integrated our gene expression data and found that E2F target genes upregulated by FOXK1 in IMR90 cells were associated with the binding of FOXK1 and FOXK2 on their promoters (273/289) (Fig. 4a, b and Supplementary Fig. 5). We also analyzed distal regions (more than 1 kb away, upstream and downstream the TSS) around these promoters and identified 1193 regions occupied by FOXK1 or FOXK2. Further, FOXK1 or FOXK2 were found to co-localize with BRD4 and H3K27Ac in IMR9039, suggesting that these distal regions are enhancers (Fig. 4b). Interestingly, FOXK1 or FOXK2-bound promoters were enriched in E2F DNA binding motifs, while distal regions bound by FOXK1 or FOXK2 were associated with other types of motifs such as Fra1/ATF3/AP-1 and CTCF, in addition to FOXK1 DNA binding motifs (Fig. 4c). Since transcriptional regulation is coordinated by promoter-enhancer interactions40, we analyzed the chromatin 3D conformation in IMR90 cells to determine potential interactions between FOXK1-bound promoters and enhancers using public Hi-C data41. We found that FOXK1-bound promoters of differentially expressed E2F target genes made more contacts with upstream FOXK1-bound enhancers compared to FOXK1-bound promoters of non-differentially-expressed genes (Fig. 4d). For example, a FOXK1-bound promoter in E2F1 gene was contacted with upstream distal FOXK1-bound regulatory sites, due to the formation of topologically associating domain (TAD). Whereas non-differentially expressed genes, such as COL4A6, present lower chromatin contacts (Fig. 4e). These results reveal that E2F target genes are regulated by FOXK1 via physical contacts between their promoters and enhancers.

a Visualization of FOXK1 and FOXK2 occupancy on promoters of E2Fs and some of their target genes. Peaks p value, called using MACS2, are shown under the gene body (Refseq) track. Peaks signal intensity is shown on the y-axis. b Occupancy of FOXK1 at promoters of 273 genes identified being differentially expressed in RNA-seq in IMR90 cells overexpressing (OE) FOXK1 compared to FOXK2. The 1193 distal regions were identified by considering peaks upstream or downstream promoters at a distance greater than 1 kb away from TSS. These regions are enriched for H3K27Ac and BRD4 and were qualified as enhancers. c Motif analysis was performed on promoters or distal regions indicated in (b). d To analyze promoter and enhancers contacts involving FOXK1-enriched regions, we used publicly available chromatin capture (Hi-C) data from IMR90 cells. Differentially expressed genes of FOXK1 compared to FOXK2 from the E2F pathway made more contacts between promoters and distal regions compared to non-differentially enriched genes. e Visualization of topological associated domains (TADs) containing high chromatin contacts in addition to numerous FOXK1 and FOXK2 peaks visualized by ChIP-seq track at E2F1 loci. For comparison, COL4A6 is a non-differentially expressed gene containing FOXK1 or FOXK2 in gene body but present low number of chromatin contacts in the TAD. Statistical significance was assessed using a Poisson distribution model (a). Motif enrichment analysis was performed using HOMER. Statistical significance was assessed using the hypergeometric test (c). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Based on these results altogether, we concluded that FOXK1 and FOXK2 link enhancers to promoter regions to orchestrate E2F gene expression programs. Importantly, while FOXK1 and FOXK2 can occupy the same gene regulatory regions, only FOXK1 expression is associated with the induction of the E2F pathway, indicating differential regulation between these transcription factors at these genomic loci.

FOXK1, but not FOXK2, is modified by O-GlcNAcylation

FOXK1 and FOXK2 are mutually exclusive partners of the BAP1 epigenetic complexes containing multiple co-factors and enzymes, including the O-linked β-N-Acetylglucosamine transferase (OGT), which mediates protein O-GlcNAcylation, a post-translational modification regulating cellular metabolism and cell proliferation28,42,43,44,45,46,47. Protein O-GlcNAcylation is reversed by O-GlcNAcase (OGA), thus positioning this modification as a dynamic regulator of cellular processes. First, we tested whether FOXK1 or FOXK2 could be O-GlcNAcylated. Transient expression of FOXK1 or FOXK2 in the presence of OGT leads to the detection of a O-GlcNAcylation signal on immunoprecipitated FOXK1, but not FOXK2 (Fig. 5a). This signal is not observed following the expression of a catalytic dead (CD) form of OGT (D925A). Depletion of OGT expression using siRNA resulted in the ablation of the O-GlcNAcylation signal of endogenous FOXK1 (Fig. 5b). FOXK1 O-GlcNAc levels could be reliably increased by treatment with the OGA inhibitor PUGNAc, or decreased with the OGT inhibitor, OSMI-4 in IMR90 and other cell types (Fig. 5c and Supplementary Fig. 6a). Of note, modulation of cellular O-GlcNAc levels did not alter FOXK1 subcellular localization (Supplementary Fig. 6b). FOXK1 O-GlcNAcylation signal is directly linked to glucose availability, since it decreases upon glucose deprivation, and increases upon gradual addition of glucose (Fig. 5d). Moreover, as FOXK1 regulates E2Fs target genes expression, we sought to determine whether FOXK1 O-GlcNAcylation is modulated during the cell cycle. U2OS cells were synchronized by serum deprivation (Supplementary Fig. 6c), while primary human lung fibroblasts (HLF) and IMR90 were arrested through contact inhibition (Fig. 5e and Supplementary Fig. 6d). Endogenous FOXK1 was then immunoprecipitated at different times following release from cell cycle arrest. Interestingly, FOXK1 O-GlcNAcylation and CDC6 expression reached their maximum levels at the same time point, suggesting that activation of E2F-dependent transcription is concomitant with FOXK1 O-GlcNAcylation (Fig. 5e and Supplementary Fig. 6c, d), and highlighting a potential role of O-GlcNAcylation in regulating FOXK1 activity during the cell cycle. Of note, FOXK1 O-GlcNAcylation is decreased during differentiation of 3T3L1 adipocytes, supporting the notion that this post-translational modification is associated with FOXK1-dependent stimulation of cell proliferation (Supplementary Fig. 6e).

a HEK293T cells were transfected with constructs expressing Myc-FOXK1 or Myc-FOXK2 in the presence of OGT WT or OGT catalytically dead (CD) mutant (D925A). Myc immunoprecipitation was performed, and levels of O-GlcNAcylation were detected using an anti-O-GlcNAc specific antibody (n = 2 independent experiments). b Immunoprecipitation of endogenous FOXK1 was performed on U2OS cell extracts following transfection with siRNA targeting OGT (siOGT) or non-target siRNA as a control (siNT) (n = 3 independent experiments). c Immunoprecipitation of endogenous FOXK1 and analysis of O-GlcNAcylation in IMR90 cells treated with either; OGA inhibitors (PUGNAc, Thiamet G (ThG)) or OGT inhibitors (OSMI-4) (n = 3 independent experiments). d Immunoprecipitation and analysis of endogenous FOXK1 O-GlcNAcylation in IMR90 cells treated with glucose free media or gradually supplemented with increasing concentrations of glucose (n = 3 independent experiments). e Immunoprecipitation and analysis of endogenous FOXK1 O-GlcNAcylation in IMR90 cells synchronized by contact inhibition and released at low density in fresh medium (n = 3 independent experiments). f Immuno-depletion and analysis of endogenous FOXK1 O-GlcNAcylation in IMR90 cells. Cellular extracts from IMR90 were used for FOXK1 immunoprecipitation. Eluted proteins were then incubated with WGA bound beads, and FOXK1 O-GlcNAcylation levels were analyzed by western-blotting (n = 3 independent experiments). g In vitro O-GlcNAcylation was performed on recombinant GST-FOXK1 or GST-FOXK2 with recombinant His-OGT-Flag. The reaction was stopped at different time points to detect protein O-GlcNAcylation levels (n = 3 independent experiments). h Left: recombinant FOXK1 fragments are schematically represented and numbered. Right: in vitro O-GlcNAcylation was performed on recombinant FOXK1 fragments to map the region containing residues modified by O-GlcNAc (n = 3 independent experiments). i Top; schematic representing the identification of O-GlcNAc sites on FOXK1 as determined by mass spectrometry (MS) analysis. Mutant FOXK17A contains seven threonine mutated to alanine, whereas mutant FOXK111A contains all the eleven sites mutated to alanine. Bottom; FOXK1 structure predicted by Alphafold. The region highlighted is expected to be unstructured. Right; Visual representation of this region with the position of residues targeted by O-GlcNAcylation are shown on the predicted protein structure. j Immunoprecipitation of Flag-tagged versions of FOXK1, FOXK17A, or FOXK111A from IMR90 cell extracts and detection of O-GlcNAcylation levels (n = 3 independent experiments). For (a–h, j), the western blots are representative of one of the three independent experiments. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Our results indicate that FOXK1 O-GlcNAcylation is dependent on the metabolic state of the cell as well as its cell cycle state, and that its extent of modification might regulate its function. Thus, we reasoned that FOXK1 molecules might exist under two major states, as either O-GlcNAcylated or non-O-GlcNAcylated, and that the switch from one form to another orchestrates functional outcomes. Alternatively, FOXK1 molecules might be O-GlcNAcylated on multiple sites, but with different degrees of modifications, defining hypo- or hyper-O-GlcNAcylated FOXK1. To further determine the extent of FOXK1 O-GlcNAcylation in proliferating cells, we first immunodepleted endogenous FOXK1 from IMR90 cell extracts and subsequently incubated the immunopurified FOXK1 on wheat germ agglutinin (WGA) coated beads to capture the fraction of O-GlcNAcylated FOXK1. Fractions were collected at all steps, including the flow through, and probed for O-GlcNAc and FOXK1 (Fig. 5f). Interestingly, we observed that nearly all endogenous FOXK1 is O-GlcNAcylated. Taking into account that FOXK1 O-GlcNAcylation can still increase or decrease upon treatments, it is likely that this factor contains multiple sites whose extent of O-GlcNAcylation (hypo versus hyper) varies depending on cellular states.

To further identify FOXK1 O-GlcNAcylation region and sites, in vitro O-GlcNAcylation assays were performed using recombinant GST-FOXK1 or GST-FOXK2, OGT, and UDP-GlcNAc. First, we confirmed that FOXK1, but not FOXK2, is O-GlcNAcylated by OGT in vitro (Fig. 5g). In addition, in vitro O-GlcNAcylation on recombinant fragments of FOXK1 showed that O-GlcNAcylation occurs at the C-terminal region of the protein, with FOXK1 fragment 1 to 455 amino acids losing its ability to be modified by OGT (Fig. 5h). Interestingly, while the O-GlcNAcylation of FOXK1 occurs at the C-terminus, the OGT-FOXK1 interaction also involves the N-terminal part of the protein (Fig. 5h and Supplementary Fig. 7a). Next, we sought to identify the FOXK1 amino acid residues modified by O-GlcNAcylation. Large-scale immunopurification of exogenous FOXK1 transfected in OGT-expressing HEK293T followed by mass spectrometry allowed the identification of seven residues within the C-terminal region of FOXK1 (Supplementary Fig. 7b). We expressed a FOXK17A mutant, replacing the seven residues targeted by O-GlcNAcylation to alanine, in IMR90, as well as in other cell types, and noticed that this mutant has significantly reduced O-GlcNAcylation signal, but a residual modification signal is still observed (Fig. 5i, j and Supplementary Fig. 8a–c). We then purified FOXK17A and identified four additional residues that are modified by O-GlcNAc. All sites were found in an unstructured region of the C-terminal of the protein (Fig. 5i). We therefore produced an additional mutant, FOXK111A, where the remaining four serine or threonine were mutated to alanine (Fig. 5i). FOXK111A showed a more pronounced decrease of O-GlcNAcylation compared to the FOXK17A mutant in IMR90 and other cell lines (Fig. 5j and Supplementary Fig. 8a–c). Of note, we observed only marginal changes of FOXK1 O-GlcNAcylation levels when mutating individual residues (Supplementary Fig. 8d). FOXK1 O-GlcNAcylation levels decrease only upon mutation of multiple sites, and the strongest decrease observed when mutating all eleven residues identified (Supplementary Fig. 8a–c and Supplementary Fig. 8e). Loss of FOXK1 O-GlcNAcylation had no effect on protein stability and protein subcellular localization (Supplementary Fig. 8f, g, h). Taken together, O-GlcNAcylation specifically targets FOXK1, but not FOXK2, which could constitute a molecular switch underlying their differential functions.

FOXK1 O-GlcNAcylation is required for cell proliferation and tumor progression

We sought to determine the potential contribution of O-GlcNAcylation to FOXK1 oncogenic properties. Expression of FOXK17A and FOXK111A in IMR90 cells led to reduced cell proliferation comparatively to FOXK1 (Fig. 6a, b). In addition, synchronized cells expressing FOXK17A and FOXK111A progressed more slowly into S phase compared to FOXK1 (Fig. 6c). FOXK1 mutants with impaired O-GlcNAcylation failed to induce E2F1, Cyclin A, Cyclin E and MCM3 expression as efficiently as the wild type form, indicating that O-GlcNAcylation modulates the ability of FOXK1 to stimulate E2F target genes (Fig. 6d). To further determine whether the loss of O-GlcNAcylation can also impact FOXK1 oncogenic properties, we performed oncogenic transformation assay using IMR90 cells expressing RASG12V with E1A in combination with either FOXK1, FOXK17A or FOXK111A (Supplementary Fig. 9a). A delayed onset of tumor appearance was noted in mice engrafted with cells expressing FOXK17A or FOXK111A compared to those engrafted with cells expressing FOXK1 (Fig. 6e, f). Cells overexpressing FOXK1 developed tumors that reached the limit point faster than cells overexpressing FOXK17A, FOXK111A (Fig. 6g, h). This oncogenic effect of FOXK1 O-GlcNAcylation was also observed with the minimal transforming combinations of co-expressing FOXK1 with E1A only, which could also lead to tumor formation in mice (Fig. 1i and Supplementary Fig. 9b). Interestingly, even FOXK1 combination with HDM2 and RASG12V, which give rise to very few colonies (Fig. 1i), can transform IMR90, when these colonies are expanded and similar numbers of cells as the HDM2 + E1A + RASG12V combination are injected in mice (Supplementary Fig. 9c). This transformation promoting ability of FOXK1 is higher than that of the O-GlcNAcylation-defective mutant.

a Phase contrast and immunoblotting of IMR90 cells overexpressing FOXK1, FOXK17A or FOXK111A. (representative of at least n = 3 independent experiments). b IMR90 cells overexpressing FOXK1, FOXK17A or FOXK111A were counted over 15 days. Data are represented as a cumulative cell doubling plot (n = 5 independent experiments at day 1, day 5, day 10, and n = 3 independent experiments extended to day 15). c IMR90 cells stably expressing FOXK1, FOXK17A, FOXK111A, or empty vector, were blocked in G0 by contact inhibition and released by plating at low density in fresh medium to monitor cell cycle progression by FACS analysis. Results are representative of three independent experiments. d E2F1, Cyclin A, Cyclin E, MCM3 mRNA quantification by RT-qPCR in IMR90 cells overexpressing empty vector, FOXK1, FOXK17A or FOXK111A (n = 4 independent experiments for empty vector and FOXK1, n = 3 independent experiments for FOXK17A and FOXK111A). e Tumor penetrance of xenografts performed with IMR90 cells expressing RASG12V with E1A in combination with either empty vector, FOXK1, FOXK17A or FOXK111A (n = 4 injected mice, except for FOXK1 n = 5). f Tumor latency representing the time between cell engraftment and appearance of tumors that reached at least 0.1 cm3 (n = 4 injected mice, except for FOXK1 n = 5). Only penetrant tumors are represented by dots. g Tumor volume was calculated at the end of the experiment. All tumors were harvested at the same time when the fastest growing tumors reached 1.7 cm3 (n = 4 injected mice, except for FOXK1 n = 5). h Representative images of tumors before and after isolation. i Immunoprecipitation of endogenous FOXK1 from normal or transformed IMR90 (combination of RASG12V with E1A and HDM2) to evaluate FOXK1 O-GlcNAcylation levels (Representative of three independent experiments). Statistics: Data are represented as mean ± SEM (b, d, f, g). Two-way ANOVA (b, d) or one-way ANOVA (f, g) with two-sided tests followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test for adjustment. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.001. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

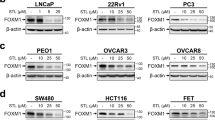

Previous studies reported that elevated protein O-GlcNAcylation in cancer can sustain tumor cell proliferation and progression48,49,50. This raises the possibility that increased O-GlcNAcylation can further sustain the oncogenic effect associated with high FOXK1 expression. Consistent with this, transformed IMR90 cells (E1A + RASG12V + HDM2) displayed increased levels of global protein O-GlcNAcylation and FOXK1 O-GlcNAcylation compared to corresponding normal cells (Fig. 6i). In addition, FOXK1 protein levels are also increased during oncogenic transformation. To further determine the impact of FOXK1 O-GlcNAcylation on cancer cell proliferation and tumor progression, we first depleted endogenous FOXK1 in U2OS osteosarcoma cells using siRNA, which resulted in decreased cell proliferation (Supplementary Fig. 9d). This effect was rescued by expression of FOXK1 but not FOXK17A siRNA-resistant constructs, and is associated with decreased mRNA levels of the E2F target gene, cyclin A (Supplementary Fig. 9d, e). To further assess if loss of FOXK1 O-GlcNAcylation could impact on tumor progression in vivo, we performed xenograft experiments using the prostate cancer cell line PC3, previously shown to exhibit high O-GlcNAc levels51. We first confirmed that overexpressing FOXK17A or FOXK111A in PC3 reduced cell proliferation compared to FOXK1 (Supplementary Fig. 9f). We then engrafted FOXK1-expressing cells in the flank of nude mice and observed reduced tumor growth with FOXK1 mutants impaired for O-GlcNAcylation (Supplementary Fig. 9g, h). In addition, expression of the FOXK17A and FOXK111A O-GlcNAcylation-defective mutants resulted in decreased E2F1 protein levels compared to FOXK1 (Supplementary Fig. 9i). Altogether, these findings illustrate that O-GlcNAcylation supports FOXK1 pro-oncogenic functions in promoting cellular transformation and tumor growth.

FOXK1 O-GlcNAcylation promotes BAP1 recruitment to E2F target gene promoters

To investigate whether O-GlcNAcylation regulates FOXK1 recruitment to chromatin, we performed ChIP-seq in IMR90 cells, which revealed conserved peaks near promoters and distal regions among FOXK1, FOXK17A, and FOXK111A (Fig. 7a–d and Supplementary Fig. 10a, b). ATAC-seq confirmed FOXK1 association with open chromatin, which remained unaffected following expression of its O-GlcNAcylation defective mutant (Supplementary Fig. 10c). These results suggest that FOXK1 O-GlcNAcylation might act downstream its binding to gene regulatory regions. FOXK1 and FOXK2 were previously shown to recruit the histone H2AK119ub deubiquitinase BAP1 to chromatin and mediate transcriptional activities28. To further examine the potential role of BAP1 in FOXK1-mediated transcriptional regulation, we first performed pulldown assays using recombinant FOXK1 and its O-GlcNAcylated form with nuclear extracts. Interestingly, while interactions of O-GlcNAcylated FOXK1 with SIN3A, NCOR1, and HDACs remained unchanged compared to non-O-GlcNAcylated FOXK1, a pronounced increase in BAP1 binding was observed upon FOXK1 O-GlcNAcylation (Fig. 7e). Next, by comparing BAP1 recruitment in IMR90 cells expressing FOXK1 with those expressing FOXK111A, we identified 2130 regions showing reduced recruitment of BAP1 in FOXK111A (Fig. 7f). GO analysis on promoters (249) contained in these differentially enriched regions (2130) revealed a strong association with E2Fs target genes (Fig. 7g). Moreover, we questioned how BAP1 recruitment was affected on promoters/enhancers of E2F target genes whose expression was induced by FOXK1 (Fig. 2d). Notably, despite the constant occupancy of FOXK1 regardless of its O-GlcNAcylation status, we observed decreased association of BAP1 with enhancer regions for FOXK17A and FOXK111A comparatively to FOXK1 (Supplementary Fig. 10d, e). We also observed an increased BAP1 association with the same enhancers in U2OS cells following the expression of wild type FOXK1, but not with its O-GlcNAcylation-defective mutant (Supplementary Fig. 11a). Thus, in both normal and cancer cells, FOXK1 O-GlcNAcylation promotes BAP1 recruitment to E2F enhancers. We also note that no difference of SIN3A association with these enhancers is observed between FOXK1 and its O-GlcNAcylation-defective mutant (Supplementary Fig. 11b).

a Chromatin occupancy of Flag-tagged FOXK1, FOXK17A and FOXK111A on all human promoters in IMR90 cells. b Bar-plot representing the repartition of endogenous FOXK1 and exogenous (3 Flag-tagged) FOXK1, FOXK17A and FOXK111A on the genome of IMR90 cells assessed by ChIP-seq. c, d Venn diagram depicting the overlap in chromatin occupancy between FOXK1, FOXK17A, and FOXK111A at promoters and at distal regions in IMR90 cells. e Top: Pulldown assay using HeLa nuclear extracts incubated with recombinant GST-FOXK1, which was either pre-modified by in vitro O-GlcNAcylation or incubated with OGT without UDP-GlcNAc (Representative of three independent experiments). Bottom: Quantification of BAP1 band signal intensity in pulldown conditions with or without FOXK1 O-GlcNAcylation in vitro (n = 4 independent experiments). f Differential recruitment of BAP1 in IMR90 cells overexpressing FOXK1, FOXK17A or FOXK111A. Regions were identified by comparing the list of BAP1 peaks from the FOXK1 expressing condition to those from the FOXK111A condition. Technical replicates were merged for visualization. Boxplot representing BAP1 spike-in normalized read counts. Endogenous FOXK1 was depleted by siRNA in conditions expressing FOXK1 and O-GlcNAc mutants. Two technical replicates were merged. g GO analysis performed on promoters (249) differentially enriched for BAP1 between FOXK1 and FOXK111A. h Boxplot representing H3K4me1 and H2AK119ub spike-in normalized reads in IMR90 cells expressing FOXK1, FOXK17A or FOXK111A on regions with differential BAP1 recruitment. Two technical replicates were merged. Statistics: Data are represented as mean ± SEM (e). One-way ANOVA with two-sided tests followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test for adjustment (f, h). Two-tailed Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare the two groups P = 0.0286 (e). GO enrichment analysis was performed using Enrichr. Statistical significance was assessed using Fisher’s exact test, and odds ratios (OR) were computed (g). Box plots display the normalized read counts for each condition. The center line represents the median. The box extends from the 25th to the 75th percentile (interquartile range, IQR). The whiskers extend to the most extreme non-outlier values within 1.5 × IQR. Outliers are not shown (f, h). *P < 0.05. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

BAP1 was previously found to interact with and recruit the methyl-transferase MLL3, which is responsible for the deposition H3K4me1 at enhancers52,53. Interestingly, IMR90 cells expressing FOXK17A or FOXK111A exhibited reduced levels of H3K4me1 on regions with reduced BAP1 recruitment (Fig. 7h and Supplementary Fig. 11c). Conversely, H2AK119ub levels were increased in FOXK17A or FOXK111A, correlating with the reduction of BAP1 recruitment in these conditions (Fig. 7h and Supplementary Fig. 11c). Additionally, we also observed reduced levels of H3K4me1 and increased levels of H2AK119ub at both promoters and enhancers (Supplementary Fig. 11c). These results suggest that loss of O-GlcNAcylation on FOXK1 alters the optimal chromatin configuration and hint to a potential mechanism for how O-GlcNAcylation of FOXK1 regulates transcription.

To further examine the functional link between BAP1 and FOXK1, we first analyzed the data of CRISPR/Cas9 knockout screens from DepMap54, which showed that cell lines with a BAP1 dependency score ≤ −0.5 were closely associated with FOXK1 dependency but distinctly segregated from FOXK2 dependency (Fig. 8a). Next, we expressed FOXK1 mutants lacking either the FHA domain, responsible for its interaction with BAP1 (FOXK1ΔFHA), or harboring an inactivating mutation in the DNA-binding domain (FOXK1H355A), to assess their contributions to cell proliferation. Our results revealed that both domains are essential for the ability of FOXK1 to promote cell proliferation (Fig. 8b). Of note, even when cells were infected with half amounts of the viral preparation (FOXK11/2), ensuring that FOXK1 expression levels are lower than that of its corresponding mutants, this factor maintains its ability to promote cell proliferation (Fig. 8b). Next, we overexpressed FOXK1 and FOXK2 (as a control), in U2OS cells stably depleted of BAP1 using shRNA. As expected, BAP1-depleted cells exhibited reduced proliferation (Fig. 8c, d)43,55. We found that FOXK1 expression failed to rescue or promote cell proliferation in the absence of BAP1. Next, we integrated our previous microarray data reporting differential gene expression following BAP1 depletion in U2OS cells42, with FOXK1 ChIP-seq data, and found that downregulated genes following BAP1 depletion are significantly enriched for FOXK1 chromatin binding (Fig. 8e). Moreover, we identified 43 E2F target genes that were strongly reduced upon BAP1 knockdown (Fig. 8f). Notably, FOXK1 occupies the promoters and corresponding distal regions of 33 (76%) of these genes (Fig. 8g).

a FOXK1, FOXK2, and BAP1 dependency scores in cancer cells extracted from Depmap. Cell lines with FOXK1 dependency scores ≤ −0.5 (CRISPR/Cas9 screens) were selected, and FOXK2 and BAP1 dependency scores were plotted. b Deletion of the forkhead-associated (FHA) domain or mutation of histidine 355 in the forkhead domain (impairing DNA binding) reduces FOXK1-induced cell proliferation in IMR90 cells. FOXK1 has been transduced in IMR90 at similar virus titers or half virus titers to obtain comparable protein expression levels with FOXK1 lacking the FHA domain. Left panel: pictures of cell culture dishes following crystal violet staining. Middle panel: quantification of crystal violet staining (n = 3 independent experiments). Right panel: western blot showing expression of FOXK1 and corresponding mutants. Representative of three independent experiments. c BAP1 depletion impairs FOXK1-induced cell proliferation. U2OS were transfected with shRNA targeting BAP1, and cells with stable knockdown were selected with puromycin. These cells were then transduced with lentivirus expressing FOXK1 or FOXK2. Cell growth was assessed by crystal violet staining (left panel). The crystal violet was extracted and quantified (right panel) (n = 3 independent experiments). d Western blotting detection of BAP1, Flag-FOXK1, and Flag-FOXK2. Flag-FOXK1 and Flag-FOXK2 expression was quantified and shown in the right panel. Representative of three independent experiments. e–g FOXK1 is enriched at promoters and distal regions of E2F target genes dependent on BAP1 expression in U2OS cells. e FOXK1 is significantly enriched on promoters of genes that are regulated by BAP1. f Heatmap showing E2F target genes downregulated in U2OS cells after BAP1 knockdown. g FOXK1 is recruited at promoters and distal regions of E2F target genes that are regulated by BAP1. h Quantification of crystal violet staining from pleural mesothelioma and lung cancer cell lines expressing either control vector, FOXK1, or FOXK111A constructs. The cell lines on the left (H2373, MESO22, H290, MESO28, MESO1, H2052) express wild-type BAP1, while the cell lines on the right (H2452, H226, MESO25, H28, MESO14, MESO61) have truncated or deleted BAP1 (n = 3 independent experiments). Statistics: Data are represented as mean ± SEM (b–d, h) One-way ANOVA (b) or two-way ANOVA (c, h) with two-sided tests followed by Dunnett’s or Tukey’s multiple comparisons test for adjustment. Two-sided unpaired t-test (d). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.001, ns non-significant. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To provide further insight into the relevance of FOXK1-BAP1 interaction in the context of cancer, we transduced pleural mesothelioma and lung cancer cell lines, that are BAP1-proficient or BAP1-deficient56, with either FOXK1 or its O-GlcNAcylation-defective mutant. Our findings revealed that FOXK1 expression significantly promotes cell proliferation, predominantly in BAP1-expressing cancer cells, while it had no impact on BAP1-deficient cells (Fig. 8h and Supplementary Fig. 12). In contrast, the FOXK1 O-GlcNAcylation-defective mutant failed to enhance cell proliferation in either cell types. These results underscore the importance of FOXK1 O-GlcNAcylation in mediating its pro-proliferative effects, particularly in the context of BAP1 expression.

Taken together, our data indicate that O-GlcNAcylation of FOXK1 regulates the optimal recruitment of BAP1 to chromatin. Abolishing O-GlcNAcylation leads to decreased BAP1 recruitment at promoters and surrounding enhancers of E2F target genes. This event is associated with a corresponding decrease of H3K4me1 and increase of H2AK119ub, explaining the switch from transcriptional active to inactive chromatin states. Thus, O-GlcNAcylated FOXK1 associates with BAP1 and promotes E2F pathway and oncogenesis.

Discussion

Our findings indicate that FOXK1 possesses potent oncogenic promoting activities and is a major regulator of the E2F pathway. Using primary human fibroblasts, we show that the process of oncogenic transformation is accompanied by increased (i) global O-GlcNAcylation, (ii) FOXK1 protein levels, and (iii) FOXK1 O-GlcNAcylation levels. We also revealed that FOXK1 oncogenic functions require its O-GlcNAcylation, which could be an important general mechanism of tumorigenesis in human malignancies. Cancer cells are known to have increased activity of the glycolytic pathway, which is thought to be a quick way to provide energy and building blocks required during fast cellular growth57. Perturbation of O-GlcNAcylation levels are also observed in cancer, and different mechanisms were proposed to explain how increased protein O-GlcNAcylation is favorable for cancer development48,49,50,58.

Previous studies demonstrated that FOXK1 regulates the glycolytic pathway, and its overexpression promotes glucose consumption and reprogramming of cell metabolism to favor glycolysis9,10. FOXK1 could therefore increase glucose uptake to fuel the hexosamine biosynthetic pathway and promote the synthesis of UDP-GlcNAc and, as a result, further enhance FOXK1 O-GlcNAcylation. Because O-GlcNAcylation is dependent on glucose availability in cells, O-GlcNAcylation might be a mechanism to regulate FOXK1 activity depending on the state of cellular metabolism and cell microenvironment. We propose that, depending on glucose availability and cellular metabolism, the extent of FOXK1 O-GlcNAcylation on its multiple sites might serve as a rheostat to regulate its transcriptional activity on the E2F pathway and orchestrate cell proliferation.

While several studies suggest that FOXK1 and FOXK2 may share redundant roles, particularly in aerobic glycolysis, autophagy, and insulin metabolism8,9,10,11, other experimental evidence distinguishes FOXK1 and FOXK2, as potential oncogene and tumor suppressor, respectively13,20,24,26. Our findings, highlighting the distinct functions of FOXK1, are consistent with previous studies showing that this transcription factor promotes cell cycle progression. For instance, FOXK1 regulates myogenic progenitor cell proliferation through recruitment of chromatin-modifying complexes such as SIN3A-HDAC to ensure repression of the CDK inhibitor p2159. Additionally, the ability of FOXK1 to repress differentiation-associated factors, such as MEF2 and FOXO4, highlights its dual role in promoting proliferation while antagonizing lineage-specific differentiation6. In contrast, our studies revealed that elevated expression of FOXK2, while having a modest negative effect on cell proliferation, results in increased mRNA and protein expression of p21. This is consistent with other studies showing that FOXK2 functions as an activator of p21, to arrest cellular proliferation60. Thus, based on our data and others, FOXK1 and FOXK2 might exert opposing roles in regulating genes involved in cell cycle progression by repressing p21, and regulating, directly as well as indirectly, the expression of E2F target genes. On the other hand, both FOXK1 and FOXK2 have been associated with stress responses. FOXK1 was shown to interact with the DNA double strand break signaling factor 53BP1 during S phase following genotoxic stress, and this function promotes DNA repair and survival61. Whether O-GlcNAcylation of FOXK1 is also critical for DNA damage repair remains an interesting question for future studies. In contrast, during hypoxic stress, FOXK2 interacts with transcriptional corepressors, including NCoR/SMRT and SIN3A, and inactivate the expression of both HIF1β and EZH2, thus modulating the hypoxic response and blocking tumor cell progression and metastasis13. Altogether, our findings and others support the idea that FOXK1 and FOXK2 transcription factors have evolved to fulfill specific and non-overlapping functions, but they also kept redundant functions in gene regulation of specific processes, notably cell metabolism.

We also found that FOXK1 and FOXK2 are recruited to the same genomic loci, but only FOXK1 was able to induce genes associated with the positive regulation of cell cycle. We showed that O-GlcNAcylation acts as a mechanism to specifically regulate FOXK1 transcriptional activities by targeting BAP1 recruitment to chromatin. Loss of FOXK1 O-GlcNAcylation reduced BAP1 recruitment to promoters and enhancers and is associated with an increased level of H2AK119ub, a mark associated with the negative regulation of transcription. In addition, H3K4me1 was decreased at a subset of promoters and enhancers associated with E2F targets. Thus, we propose that O-GlcNAcylation fine tune FOXK1 transcriptional activities by allowing optimal recruitment of BAP1.

The mutually exclusive interaction between BAP1 and FOXK1 or FOXK2 via phosphorylated threonine 493 (T493, T492 in mice) underlines a dynamic regulatory mechanism in chromatin function and transcriptional regulation. Both FOXK1 and FOXK2 use their FHA domains to bind phosphorylated T493 in BAP1, forming a core interaction module. However, our findings reveal that FOXK1 undergoes O-GlcNAcylation, which significantly enhances its affinity for BAP1. This post-translational modification introduces a second interaction module, stabilizing the overall interaction of BAP1 with FOXK1. The interplay between BAP1 T493 phosphorylation and FOXK1 O-GlcNAcylation suggests a dual-modulation system that dynamically orchestrates BAP1 recruitment to chromatin depending on the cellular context. For instance, during the G1/S transition, time at which the transcriptional activation of E2F target genes is critical, increased O-GlcNAcylation of FOXK1 might favor BAP1-FOXK1 complexes at the expense of BAP1-FOXK2 complexes. This dynamic coupling might ensure that gene regulation is aligned with cell cycle and metabolic demands, enabling adaptive responses to external stimuli such as nutrient availability.

An interesting finding of our study is the dependence of O-GlcNAcylated FOXK1 on BAP1 in promoting cell proliferation and tumor progression. It appears counterintuitive that the oncogenic functions of FOXK1 rely on BAP1, which is a well-established tumor suppressor62,63. Previous studies have indicated that BAP1 can promote the expression of E2F targets, and moreover, the oncogenic properties of KLF transcription factor 5 (KLF5) also appear to be mediated through BAP1 function64. On the other hand, gain of function of BAP1 was also documented in hematological malignancies following truncating mutations of ASXL proteins that preserve their DEUBAD, the domain responsible for interaction with, and activation of, BAP165,66. These mutations are associated with enhanced deubiquitinase activity towards histone H2AK119ub, and is associated with increased proliferation of cancer cells. Moreover, we showed that BAP1 becomes co-opted by FOXK1 to drive mesothelioma cell proliferation in tumor cells expressing wild-type BAP1. Mesothelioma, a highly aggressive cancer, shows BAP1 mutations in 40–50% of cases and normal BAP1 expression correlates with worse prognosis and reduced patient survival67,68. Thus, BAP1-FOXK1 interaction might constitute a therapeutic opportunity in BAP1 positive mesothelioma tumors.

In conclusion, while our studies provided important insights into the role of O-GlcNAcylation in the regulation of FOXK1-BAP1 interaction and the E2F pathway, it remains to be determined how the interplay between these factors impacts transcription and balances BAP1 deubiquitinase activity during tumor development or suppression.

Methods

No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample size, and the investigators were not blinded to allocation during experiments and outcome assessment.

Ethical statement

All animal studies were approved by the Animal Care Committee of the research center of the Maisonneuve-Rosemont Hospital and in agreement with the guidelines of the Canadian Council on Animal Care under protocol number 2024-3365. All animals were maintained in large group houses of 4–5 members under 12-h dark and light cycles and were given access to food and water ad libitum.

Molecular DNA cloning and mutagenesis

Plasmids for expression of human Myc-OGT and Myc-OGT D925A catalytic inactive mutant (Myc-OGT CD) were previously described69. His-OGT-Flag was generated by subcloning the OGT cDNA into pET30a+ vector (Novagen®). siRNA-resistant human FOXK1 and FOXK2 cDNAs were synthesized into a pBluescript plasmid (Biobasic®) and subcloned into pENTR (Life technologies®). GST-, FLAG-, and MYC-tagged, retroviral pMSCV-Flag/HA (Addgene, #41033) and pMSCV-3Flag (generated for this study) constructs were generated using the Gateway recombination system (Life Technologies). GST-FOXK1 fragments were generated by PCR and subcloned into pENTR. FOXK1 single and multiple O-GlcNAc sites mutants, including FOXK17A and FOXK111A mutants, were generated with site directed mutagenesis or gene synthesis and subcloned in appropriate bacteria or mammalian expression vectors. We used pCMV-VSVG (#8454, Addgene) and HELPER to generate retroviral particles. The following retroviral vectors were used for cellular transformation: pWZL-hygro E1A (#18748, Addgene), pWZL-Blast RASGV12 (#12277, Addgene), and pWZL-neo HDM270. All DNA constructs were sequenced.

Alphafold structure prediction

The AlphaFold Protein Structure Database was used to retrieve human FOXK1 structural model (Uniprot: P85037-F1)71,72. Visualization of the structural model and the corresponding amino acids was generated using ChimeraX73. The side chains of the corresponding amino acid are shown as sticks. The O-GlcNAcylation sites are located within a C-terminal region with a per-residue model confidence score (pLDDT) below 50, likely corresponding to an unstructured region.

Cell culture and treatments

Human lung fibroblasts (IMR90, CL-173), transformed human embryonic kidney cells (HEK293T, CRL32-16), transformed human embryonic kidney cells (Phoenix-AMPHO, CRL-3213), human osteosarcoma cells (U2OS, HTB96), chronic myelogenous leukemia (K562, CCL-243), prostate adenocarcinoma (PC-3, CRL-1435), murine preadipocyte (3T3-L1, CL-173), human colon cancer (HCT116, CCL-247) and cervical carcinoma cells (HeLa, CCL-2) were purchased from ATCC®. Primary lung fibroblasts (HLFs) were obtained from Dr. Elliot Drobetsky (Montreal University). Cells were cultured at 37 °C and 5% CO2, in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, Wisent®, 319-005-CL) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Wisent, 098150) or in 5% new-born calf serum (NBS, Sigma®, N4637) with 2% FBS. K562 cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 5% NBS. Pleural mesothelioma cell lines that are proficient (MESO1, MESO22, MESO28, H2052, H2373, H290) for BAP1 or deficient for BAP1 (MESO14, MESO25, MESO61, H28, H2452) as well as the non-small cell lung carcinoma (H226), kindly provided by Dr. Yoshitaka Sekido56, were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS. The sex of the cell lines is specified in the reporting summary.

Media were supplemented with 4 mM L-Glutamine (Bioshop®, GLU02.500), 100 U/ml Penicillin (Biobasic, PB-0135), and 100 µg/ml Streptomycin (Bioshop, STP101.100). Cells were regularly tested for mycoplasma contamination by PCR and DAPI staining. For modulation of FOXK1 O-GlcNAcylation levels, cells were treated, in the complete culture medium, with 10 µM of the OGT inhibitor OSMI-4, or with 50 µM of the OGA inhibitor PUGNAc or Thiamet G, and harvested at the indicated times for immunoprecipitation or immunofluorescence. Cells were also incubated in a modified Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) containing no glucose or amino acids. For experiments with increasing glucose concentration, cells were incubated in glucose-free culture medium completed with 0 g/L, 0.2 g/L, 1 g/L, or 4.5 g/L of glucose for the indicated times and harvested for immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting. For analysis of FOXK1 stability, cells were treated with 20 µM of MG132 (Sigma, C221) or 20 µg/ml of cycloheximide (Bioshop, CYC003.1) and harvested at the indicated times for immunoprecipitation or immunoblotting. For Palbociclib treatment, IMR90 cells were seeded in 24 well plates at a density of 20,000 cells per well. Cells were treated with Palbociclib (MedChemExpress, PD 0332991) at 5 µM concentration and followed for growth using the Incucyte system (Sartorius) for 96 h.

Cell cycle synchronization and flow cytometry Analysis

U2OS cells were grown to confluence and then serum starved for 24 h. Cells were subsequently incubated in fresh media containing 20% FBS for the indicated times before being harvested for immunoprecipitation and flow cytometry analysis. Primary human fibroblasts were grown to confluence and further cultured for 3 days. The cells were then serum starved for two days, trypsinized, and replated in fresh medium before being harvested at the indicated times for immunoprecipitation and flow cytometry analysis. For flow cytometry analysis, the cells were harvested by trypsinization and fixed with 75% ethanol. Following centrifugation, cells were incubated for 30 min at 37 °C in PBS containing 100 µg/ml RNase A (Biobasic, RB0473) before DNA staining with 50 µg/ml propidium iodide. Cell DNA content was determined with a FACSCalibur™ flow cytometer (BD Biosciences®) and analyzed with the CellQuest™ Pro software (BD Biosciences). U2OS cells were synchronized at the G1-S phase transition by treatment with 2 mM thymidine (Sigma, T9250) for 12 h. After washing, the cells were released for 12 h and then treated again with 2 mM thymidine for another 12 h. The blocked cells, corresponding to the G1-S transition, were harvested. For the S phase, cells were washed and released into complete media for 6 h. U2OS cells were also synchronized in M phase by treatment with 200 ng/mL nocodazole (Sigma, 487928) for 18 h. Mitotic cells were obtained by mitotic shake-off, while the remaining adherent cells were harvested and analyzed for the G2 phase. Early G1 phase cells were obtained by replating M phase cells from the mitotic shake-off into complete media for 3 h.

Cell differentiation

3T3L1 differentiation was done essentially as described before44. Exponentially proliferating cells were grown to confluence and then left at confluence for 48 h before incubation in differentiation media (DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 4 mM L-Glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin/streptomycin, 1 μM dexamethasone (Sigma, D-2915), 1 μg/ml insulin (Sigma, I5500) and 500 μM isobutylmethylxanthine (Sigma, I5879). Two days post-induction, the differentiation medium was changed for complete DMEM medium supplemented with 1 μg/ml insulin. Media were changed every 48 hours, and cells were harvested at the indicated time points for immunoprecipitation or immunoblotting.

Colony forming assay (CFA)

Similar numbers of U2OS, HCT116, or PC3 cells stably expressing the different constructs of FOXK1 or FOXK2 were seeded on 6 cm or 10 cm plates. Following 3 to 10 days of culture, the surviving colonies were washed with PBS and fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 20 min. Cells were then washed with PBS once and stained with 0.2% crystal violet for 10 min. Following several washes with water, the plates were imaged and colonies counted. Where indicated, CFA were quantified using the Fiji software74 or crystal violet was extracted with 10% acetic acid, and optical density (OD) determined at 570 nm.

SA-β-gal activity assay

Senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-gal) activity assay was performed as previously described in refs. 35,75. Briefly, cells were fixed with 0.5% glutaraldehyde (Sigma, G5882) in PBS for 15 min, then washed and kept in PBS (pH 6.0) containing 1 mM of MgCl2, for at least 24 h. SA-β-gal staining was performed at 37 °C using a solution containing X-Gal, potassium ferricyanide, and MgCl2 in PBS (pH 6.0). Images were taken with an inverted microscope and the percentage of SA-β-gal positive cells was quantified in each condition.

Antibodies

A rabbit polyclonal anti-FOXK2 antibody was generated and validated by RNAi. Mouse monoclonal anti-FOXK1 (G4, sc-373810), mouse monoclonal anti-BAP1 (C4, sc-28383), rabbit polyclonal anti-OGT (H300, sc-32921), mouse monoclonal anti-tubulin (B-5-1-2, sc-SC-23948), mouse monoclonal anti-CDC6 (180.2 sc-9964), rabbit polyclonal anti-FOXK1 (H140, sc-134550), mouse monoclonal anti-E2F1 (KH95, sc251), mouse monoclonal anti-cyclin A2 (6E6, sc-56299), mouse monoclonal anti-HSP90α/β (F8, sc-13119), mouse monoclonal anti-PML (PG-M3, sc-966), mouse monoclonal anti-HRAS (C-20, sc-520) were from Santa Cruz Biotechnologies®. Rabbit polyclonal anti-HCF-1 (A301-400A) was from Bethyl Laboratories®. Mouse monoclonal anti-Flag (M2), mouse monoclonal anti-Actin (MAB1501, clone C4), and rabbit polyclonal anti-GST (G7781) were from Sigma-Aldrich. Rabbit polyclonal anti-FOXK1 (MNF, ab-18196), monoclonal anti-O-Linked N-acetylglucosamine (RL2, ab2739), rabbit polyclonal anti-H3 (ab1791) were from Abcam®. Mouse monoclonal anti-Rb (4H1, 9309S), rabbit polyclonal anti-phospho Rb (S807/811, 9308), rabbit mono anti-USP10 (D7A5, 8501), rabbit polyclonal anti-Perilipin (D1D8, 9349) were from Cell Signaling®. Rabbit polyclonal anti-FABP4 (10004944) was from Cayman Chemical®. Rabbit anti-E1A and mouse anti-MYC are homemade antibodies. Mouse monoclonal anti-P21 was from Pharmingem™ (SX118).

Xenograft

Prostate cancer cells PC3 or primary fibroblasts IMR90 expressing FOXK1, FOXK2 or FOXK1 mutants were used for xenograft experiments. Primary IMR90 cells were transduced with different combinations of oncogenes by retroviral transduction to evaluate their oncogenic transformation ability. PC3 or transformed IMR90 cells were trypsinized, counted, and then resuspended in culture media supplemented with an equivalent volume of Matrigel® (Corning™, 356237). About 2 × 106 cells were subcutaneously injected (0.1 ml) using a 21-gauge needle in the right and left flanks of each 6-week aged athymic nude mice (JAX002019, Jackson Laboratory®). Tumor size was followed at several points post injection by measuring the length and width of the tumor using a caliper. Tumor volume was calculated with the following formula (4/3*(3.14159)*(Length/2)*(Width/2)^2). All xenograft experiments were performed on both male and female animals except for PC3 prostate cancer cells which were performed on male mice only. Tumor penetrance was calculated as a percentage of tumors observed compared to the total number of engraftments. Tumor presence was defined when a tumor size of at least 0.1 cm3 is observed. Tumor latency was defined as the mean time until tumor reached 0.1 cm3. No significant dis-comfort was noticed in the tumor bearing mice in the time frame of completing the experiment. General check-up was performed every day and mice body weights were measured every week. Criteria for interventions were set when the tumor reaches 1.7 cm3 or if the tumoral mass of both flanks exceed 10% of the animal body weight. At the end of the experiment, animals were euthanized with CO2/isoflurane influx followed by cervical dislocation.

Retroviral and lentiviral transduction

Retroviruses were produced in Phoenix-Ampho. Cells were plated in 15 cm tissue culture dishes, and the next day, cells were transfected at 70–80% confluence. For one dish, 30 µg of plasmid, 10 µg of pCMV-VSVG, and 10 µg HELPER were mixed with 143 µl of 1 mg/ml polyethylenimine (PEI) (Sigma, 408727), incubated for 45 min, and then added to the cells. The cell media was changed 16 h post-transfection, and retrovirus containing supernatants were collected at 48, 72, and 96 h post-transfection. The viral supernatant was filtered through 0.45 µm filter and added to the target cells along with 8 µg/ml polybrene (Sigma, H9268). Following one to three infections, 16 h each, the cells were selected with 2 µg/ml puromycin (Bioshop, PUR333) for 48 h. Lentiviruses were produced in H293FT with PEI transfection by combining lentiviral pLenti-CMV expression vector (Addgene #17452) coding for FOXK1, FOXK2, or pLentiCRISPR_V2 vector for gRNA (Addgene #52961) targeting FOXK1 (gRNA-1: CACCGGAACATGGCCGAAGTCGGCG, gRNA-2: CACCGCGGCAAGAACGGCGTCTTCG) or control gRNA targeting GFP (CACCGGGGCGAGGAGCTGTTCACCG) with packaging vectors PAX2 (Addgene #35002) and PMD2G (Addgene #12259) using the same ratios as retroviral viruses productions.

Mass spectrometry