Abstract

Phase transitions are fundamental features of statistical physics. While the well-studied continuous phase transitions are known to be controlled by external global changes affecting the order parameter, the origin of abrupt transitions is not fully clear. Here we show that abrupt phase transitions may occur due to a unique internal random spatial cascading mechanism, arising from dependency interactions. We experimentally unveil the underlying mechanism of the abrupt transition in interdependent superconducting networks to be governed by a unique metastable state of a long-living resistance cascading plateau. This plateau is characterized by spontaneous cascading events that occur at random locations and last for thousands of seconds, followed by a sudden global phase shift of the system. The plateau time length changes with the system size and distance from criticality, obeying scaling laws with critical exponents. Furthermore, like epidemic spreading, these changes are characterized by a branching factor which equals exactly one at the critical point and deviates from one off criticality. Importantly, the branching factor provides an early warning for the closeness of critical catastrophic cascades yielding system collapse.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Phase transitions (PTs) are among the most intriguing phenomena of statistical mechanics and are usually classified by their macroscopic features close to the critical point1,2,3,4. Second-order PTs are characterized by a continuous transition of the order parameter at the critical point, while first-order PTs display an abrupt change between phases5. In contrast to first-order PTs, second-order PTs display critical behavior near the critical point characterized by the scaling laws of different quantities2,3. A unique class of PTs is mixed-order PTs, which display both an abrupt change similar to first-order transitions, and scaling laws and critical exponents near the critical point similar to second-order transitions6,7,8,9,10. Here we present experimental findings on the cascading mechanism origin of interdependent superconducting networks that exhibit a mixed-order phase transition.

The paradigm of physical interdependent networks has recently been introduced by the realization of the first physical manifestation of an experimental setup of interdependent systems - interdependent superconducting networks (ISN)11. This experimental discovery paves the way for a new research avenue of interdependent materials. ISNs have been found to experience an abrupt transition, as predicted by the theory of interdependent networks12, arising from the interplay of two types of interactions in the system: connectivity interactions within each network allowing current to flow, and dependency interactions between the networks in the form of thermal dissipation. Nonetheless, the underlying mechanism of the abrupt transition and its critical behavior remained elusive. Here, we reveal experimentally and theoretically the underlying mechanisms behind the abrupt jump observed in ISNs. We identify and characterize the temporal-spatial scaling of the long-term plateau state, which represents a random cascading mechanism of PTs. The plateau time length changes with the system size and distance from criticality via scaling laws characterized by universal critical exponents. Like epidemic spreading, these cascading changes are governed by a branching ratio that equals one at criticality, falls below one in the stable regime, and exceeds one in the unstable regime. Therefore, as this factor approaches one from below, the risk of a catastrophic cascade increases12. Measuring this observable offers a practical early warning indicator of proximity to system collapse -an insight rarely accessible in real-world settings, which we are able to measure experimentally. We experimentally confirm that the universality class suggested in ref. 13 defines the critical behavior of physical interdependent networks, as found here in our characterization of the critical behavior of ISNs.

Results

Experimental setup

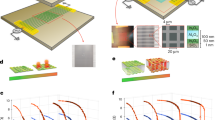

Our ISN system is composed of two coupled amorphous indium oxide (a - InO) disordered 2D superconducting networks, each containing a grid of \({{\mathscr{N}}}=L\times L\) segments with L being the linear size of the system (see Fig. 1a–d). The two layers are separated by an electrically insulating spacer (Al2O3) that has good heat conductance. The interdependent networks paradigm is manifested here by the connectivity links, represented by currents within each network layer, and dependency links realized via heat transfer between the layers. Each connectivity link i is characterized by a Josephson junction I–V characteristics14 with a distinct critical temperature Tc,i and a critical current Ic,i determining its superconductor-normal (S-N) transition threshold15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24. We note that the high disorder of the samples yields a wide distribution of Tc,is and Ic,is, leading to large sample-to-sample fluctuations of the superconducting properties.

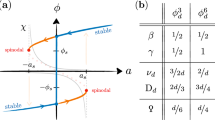

a Experimental systems. b Zooming in on the overlap section of the networks. c Large view of scanning electron microscope images of the superconducting network. d Each network segment is 10 μm long and 2μm wide. For a fixed temperature (T = 1.8K), the network resistance, RN, is measured for increasing current (blue) and decreasing current (red) showing hysteresis in both (e) experiment (for the top layer of an ISN with linear size L = 416) and (f) theory based on numerical solution of the Kirchhoff equations (L = 20, see Methods for simulation parameters). For decreasing current, the critical exponent β = 1/2 (Eq. (1)) is observed near the critical point Ic from N to S in both experiment and numerical solution (insets (e) and (f) respectively), indicating a mixed-order transition and thus belonging to the same universality class as percolation on abstract interdependent networks12.

Resistance versus current measurements

The system is set at a fixed and controllable temperature, and the network resistance, RN, is experimentally measured as we sweep the bias current Ib from high to low and back. During this process, an abrupt jump is observed at a critical point Ic,← from the mutual normal state (N) to the mutual superconducting state (S) as the current decreases, and from the S-state back to the N-state at Ic,→ as the current increases, showing a hysteresis phenomenon, see Fig. 1e. This result can be obtained theoretically by solving the Kirchhoff equations of both networks simultaneously while accounting for the thermal coupling between the layers11 as seen in Fig. 1f. The characteristics of ISNs clearly exhibit an abrupt transition but also a critical exponent β, describing the scaling of RN as the current approaches the critical point Ic from the N-state to the S-state as

where ΔI = Ib − Ic. Both, the experimental and numerical simulation results follow the scaling behavior with the same value of the critical exponent β = 1/2 (Fig. 1e, f insets respectively). The same exponent is observed for fixed current and varied temperature (Fig. S1) and in simulations of other interdependent systems including abstract percolation on interdependent networks25 and interdependent ferromagnetic networks26, confirming that the transition is universal in mixed-order PTs13.

The role of the dependency between the superconducting networks formed by the heat dissipation in ISNs is intrinsic to the critical behavior and can be understood by the I–V curves for different system sizes as shown in Fig. 2a, d. Small systems produce weak heat dissipation, making the coupling weak, thus resulting in a continuous transition similar to the transition observed in single isolated networks11. Large systems, on the other hand, dissipate enough heat for an abrupt transition to emerge, suggesting that the sample size also influences the critical behavior. Furthermore, as seen in Fig. 2b, e, the critical transition points are found to depend on the system size. While for small systems the transition is continuous and Ic,→ = Ic,←, for large systems abrupt transition and hysteresis are observed showing Ic,→ > Ic,← and both critical thresholds increase with the system size as shown in Fig. 2b, e. The hysteresis presents three regimes: N-state for Ib > Ic,→, S-state for Ib < Ic,← and an S/N-state depending on the initial conditions for Ic,← < Ib < Ic,→. The increase of the critical current with the system size allows us to estimate the correlation length critical exponent ν using the scaling relation27,28,29

where ν is the correlation length exponent and Ic(∞) is a fitting parameter (see methods). Figure 2c, f show for both experimental and theoretical results the critical exponent ν = 3/4, as predicted for systemic cascades at mixed-order phase transitions in d = 2 dimension13.

a Experimental results (top networks) for the I--V curves of interdependent superconducting networks for different system sizes taken at T = 1.8K. Small systems experience continuous phase transition like a single layer11, while for large systems abrupt transition is observed. The asymmetry in the characteristics of the I--V curves is the result of the different critical points for increasing and decreasing currents, i.e., the hysteresis. b This behavior is reflected by the critical currents. For small systems, identical critical points are shown for both increasing and decreasing current Ic,→ = Ic,←. Larger systems experience an abrupt transition and hysteresis appears with Ic,→ > Ic,←. c The correlation length exponent ν = 3/4 is evaluated using the scaling of the critical point with the system size (Eq. (2)) as predicted for interdependent systems13. d–f The theory based on numerical results for the iterative solution of the coupled Kirchhoff equations supports the experimental findings shown in (a, b, c), respectively.

Dynamics during the abrupt transition

Identifying the underlying physical mechanisms of a phase transition is essential to understand its nature. To this end, we measure experimentally the dynamics of the system, i.e., the resistance versus time of the system, R(t), during the abrupt transition from the mutual N-state to the mutual S-state at and near the relevant critical threshold Ic, see Fig. 1e, f. The results shown in Fig. 3a are based on the following protocol: (i) The system is controlled and fixed at a temperature T < Tc and the bias current is set at Ib > Ic so the system is tuned to be in the N-state. (ii) At time t = 0 the current is abruptly switched to a value Ib < Ic and R(t) is measured. Remarkably, when the bias current is switched very close to the critical current Ib → Ic, the resistance curves display a semi-saturated resistance for a long time (similar to a ghost attractor found in other systems30,31) before it drops abruptly to zero resistance as the system transits to the S-state (Fig. 3a, c show experimental and numerical results respectively). As seen, the lifetime, τ, of this plateau can last for thousands of seconds. That is, macroscopic times of many orders of magnitudes longer than the timescales of electronic interactions (τe ~ 10−12−10−10s) within each network or phonon between them (τp ~ 10−8 − 10−6s), indicating that the interplay between the layers plays a significant role in the process. This behavior is in marked contrast to the rapid realization observed at the critical point of second-order transition (see Fig. S4). The inset of Fig. 3a zooms in on the plateau regime, showing that the resistance does not monotonically decrease with time but fluctuates. Similar behavior are reproduced by the theory upon introducing thermal fluctuations (Fig. 3c).

a The resistance of an L = 416 ISN is measured experimentally as a function of time (in seconds) during the abrupt transition from the mutual N-state to the mutual S-state for different bias currents Ib ≤ Ic, and a long-term plateau is observed. The time duration of the plateau τ decreases as the current departs from Ic. The inset zooms in on the plateau regime of the top network, showing that the resistance monotonically decreases but is affected by thermal fluctuations. b The plateau timescale τ follows the scaling with the distance from criticality, ΔI = Ib − Ic, in Eq. (3) with ζ = 1/2 and the scaling with the system size in Eq. (4) with ψ = 1/3. Both exponents are similar to those found for percolation on abstract interdependent networks32. c Long-lived plateau is also observed theoretically by solving numerically the Kirchhoff equations of the thermally interdependent superconducting networks. d In the numerical simulations one can also see that the plateau time scale at the critical current Ic increases with the system size according to Eq. (4) with ψ = 1/3 and (e) decreases with the distance from criticality ΔI, according to Eq. (3) with ζ = 1/2, in excellent agreement with experiment shown in (b).

We repeat the above process by deep quenching to slightly lower values of Ib and find that, as Ib decreases, τ decreases as well (Fig. 3a). The measured plateau duration time τ is found to follow a scaling behavior with the distance of the bias current from the critical current as

with an exponent consistent with ζ = 1/2 as seen in Fig. 3b, e for experimental and theoretical results respectively. This value is consistent with the theoretical prediction for percolation on abstract interdependent networks32.

Cascading mechanism origin

The long plateau indicates a mechanism of spontaneous long-term local changes. This long-term plateau suggests that, due to the long-range dependency (heat) in such ISNs, each segment in one network may influence any other segment in the second network. Thus, the interactions become nearly spatially random where, near criticality, phase changes (N-S) of elements are generated anywhere in the system depending on Tci and Ici of the individual segments, see Fig. 4. In this near criticality regime, the phase transition is governed by a spontaneous random-cascading, i.e., a chain of events where one element, that has changed its phase, influences on average one element at a different location with closest Tci and Ici in the other network due to thermal dissipation. This process continues until enough elements undergo a phase change, thus causing an abrupt macroscopic PT. We note that, while the experiment focuses on the transition from N to S, an analogous process is expected to occur for a transition from S to N, as illustrated in Fig. 4.

a An ISN system is stabilized at T < Tc and I < Ic where all segments are superconducting and there is no thermal dissipation in the system. b At time t = 0 the current is switched to Ib > Ic so that one segment switched to the N state and (c) dissipates heat to the entire networks system. d This causes a random segment in the second network to switch to the N phase and to dissipate heat. e–g This feedback process of one segment creating a phase change in a random segment in the other network, continues spontaneously back and forth for a macroscopic time until (h) an abrupt transition occurs and both networks become normal.

Since the changes during the plateau are those of a few network elements, in order to influence the whole system, we expect τ to depend on the sample size. For this, we measure the time duration of the plateau, τ, for different system sizes. Indeed, Fig. 3b, d shows experimental and theoretical (based on numerical solutions) measurements of the dependence of τ on the system size, which follows:

with ψ = 1/3 which satisfies the relation ψ = ζ/(νd) (see Supplementary Information). Note that this exponent has also been observed in percolation on abstract interdependent networks32. This result supports our paradigm that the plateau, during the abrupt transition, represents a cascading process that occurs spontaneously for a macroscopic time. The collapse of all experimental curves in the plot of Fig. 3b is rather striking and further supports the interpretation of the slowing down arising from critical branching.

To further support this cascading paradigm and enhance our understanding on the mechanism, we analyzed the plateau behavior as a branching process to characterize the underlying dynamics33,34,35. Consider the branching factor (branching ratio), \({{\mathscr{R}}}\), which defines the average number of segments in a network that are affected by a single segment in the other network that changes its state e.g, from N to S. This parameter is analogous to the branching factor \({{\mathscr{R}}}\) observed in multitude of systems experiencing a branching process36,37,38. A canonical example of a branching process is an epidemic spreading, such as COVID-1939 or any disease40. In such cases, the branching factor measures how many people, on average, an infected individual will infect before recovery or death. For the mean-field approximation of epidemics spreading, \({{\mathscr{R}}} < 1\) means the disease is being suppressed, while \({{\mathscr{R}}} > 1\) means it spreads exponentially fast41. The case of \({{\mathscr{R}}}=1\) is critical and means that a person with the disease passes it onto only one other person on average, and the population of infected increases linearly over time. Since \({{\mathscr{R}}}\) fluctuates over time and the process may early converge into an absorbing state, one would need to average over many realizations to observe \(\langle {{\mathscr{R}}}\rangle=1\)42.

While basic epidemic spreading models show continuous PTs41, more complex models show first-order PTs43 and, in some cases, present a plateau behavior44. In our ISNs, the PT at criticality is abrupt and characterized by a long-term plateau, while during this abrupt transition, \({{\mathscr{R}}}\) is exactly one along the plateau (Fig. 3a), before the system abruptly changes its phase. This is because the heat dependency interaction range extends over the entire sample (allowing for mean-field to be valid, see Methods) and hence, each segment that changes phase from N to S will affect, on average, exactly one segment in the other network with the closest Tc and Ic. This implies that above Ic it is expected that \({{\mathscr{R}}} < 1\) and below Ic, one can expect \({{\mathscr{R}}} > 1\) while the critical branching occurs at \({{{\mathscr{R}}}}_{c}=1\).

In order to test the above hypothesis, we quantify \({{\mathscr{R}}}\) in our ISNs along the plateau using the following procedure:

for each network. Figure 5 shows both experimentally and theoretically the average branching \(\langle {{\mathscr{R}}}\rangle\) during the plateau for different currents around the critical point. It is seen that above the critical point (ΔI > 0), the average branching factor \(\langle {{\mathscr{R}}}\rangle\) is smaller than one and each segment impacts on average less than one segment, departs from one as ΔI increases, leading to an early stop of the cascading process, and the system remains at the N-state. Below the critical point (ΔI < 0), the average branching factor is larger than one, increases with ΔI, and each segment impacts on average more than one segment, and the cascading process transitions the system into the S-state. Exactly at the critical point (ΔI = 0), a critical branching factor of \({\langle {{\mathscr{R}}}\rangle }_{c}=1\) is observed where each segment impacts on average exactly one segment. This behavior of the branching factor around criticality further supports our hypothesis of the spontaneous cascading during the abrupt mixed-order transition, and we expect similar behavior in other abrupt transitions. The experimental measurements of the plateau used to estimate the branching factor are shown in Fig. S2. Similar behavior for the branching factor is also observed for fixed current and varied temperature (Fig. S3).

a Experimental (top network of an L = 416 ISN) and (b) theoretical measurements of the average branching factor during the cascading near criticality of the abrupt transition. These are extracted from resistance versus time curves shown in Fig. S2. Above the critical point (ΔI > 0), the average branching factor \(\langle {{\mathscr{R}}}\rangle\) is smaller than one, and each segment impacts on average less than one segment. Below the critical point (ΔI < 0), the average branching factor is larger than one, and each segment impacts on average more than one segment, as hypothesized. Note also that \(\langle {{\mathscr{R}}}\rangle\) approaches 1 as I approaches Ic from both directions. Exactly at the critical point (ΔI = 0) a critical branching factor of \({\langle {{\mathscr{R}}}\rangle }_{c}=1\) is observed, where each segment impacts on average exactly one segment.

Discussion

One of the most important aspects of phase transitions is its underlying mechanism, which determines and characterizes its nature. The state-of-the-art underlying mechanism of phase transitions usually involves macroscopic interventions such as changing an external parameter of the entire system for second-order transitions or the spreading of growing nucleating droplets in first-order transitions1,2,3. Here we reveal that an abrupt macroscopic phase transition can occur due to spontaneous long-term cascading changes whose time scale is macroscopically long and depends on the system size. This finding fundamentally alters our understanding of phase transitions. It experimentally confirms that cascading processes are at the origin of the long-lived metastable state close to the spinodal point45,46,47 and is expected to be found in a large class of systems that experience spontaneous cascading phenomena during their transition48,49,50,51,52,53.

The critical branching factor \({\langle {{\mathscr{R}}}\rangle }_{c}=1\) experimentally observed here at the critical point can be used to estimate the resilience of real systems. Since estimating the critical point of real-world systems is a difficult task54, having at hand a metric to estimate the system’s resilience is critical. In a real-world system, ideally, one would gather data, build a model of the system, and measure the branching factor by testing the model. However, while the connectivity links composing the network structure are usually easier to obtain, the dependencies between nodes in different networks are rarely easy to derive from data. Hence, another approach will be needed. Stable real-world systems often experience local failures that do not lead to a total collapse. Hence, these systems are characterized by \(\langle {{\mathscr{R}}}\rangle < 1\). To estimate the system’s resilience, one should track local failures and measure the gap \(\Delta {{\mathscr{R}}}={\langle {{\mathscr{R}}}\rangle }_{c}-\langle {{\mathscr{R}}}\rangle\) as a proxy for resilience, recommending applying mitigation strategies for catastrophic events. The closer \(\Delta {{\mathscr{R}}}\) is to zero, the larger the risk of system collapse.

The features of the transition in our ISNs, characterized by the set of critical exponents (β, ν) = (1/2, 3/4) and (ζ, ψ) = (1/2, 1/3), is similar to that found for abstract percolation on interdependent networks25,32 and for the theoretical model of interdependent ferromagnetic networks9,26 confirming that properties of mixed-order transitions are universal13, suggesting that the cascading mechanism could be the origin of mixed-order transitions observed in a wide range of different systems.

While the network structures in this work are restricted to a 2D lattice, the insights of this work are relevant to non-symmetric topologies for two reasons. First, the disordered compositions (i.e., the critical temperatures and critical currents of the segments) vary between segments, hence breaking the symmetry of the structure. Second, it was already shown in percolation on interdependent networks55 that as long as the dependencies are random between the networks (as in our work), the topology of the network only shows quantitative variation (i.e., changes of the critical points) but the qualitative critical behavior remains the same. Suggesting, as shown in our work, the cascade behavior is controlled by the thermal coupling and not by the network topology.

Methods

Experimental setup and measurements

We performed the experiments for current-voltage characteristics using a Keithley 2410 sourcemeter and a Keithley 2000 multimeter for each network at T = 1.8K. The cryostat temperature was controlled and measured via a LakeShore 330 using a 25Ω heater and a DT-670 thermometer placed inside the cryostat. We tested and confirmed the absence of short-cuts between the layers by measuring the junction resistance between each pair of cross contacts. The cross-layer couplings are created by passing the same current within both layers simultaneously, thus generating dependency links sustained by heat transfer. After determining the critical points Ic,← and Ic,→ of the coupled system for up and down sweeps of the current (Fig. 2a–c), we performed the time-dependent experiments described in the text and presented in Fig. 3a, b.

RSJJ model of disordered superconducting networks

To characterize the SN transitions observed in the experiments, we model each disordered superconductor via a disordered 2D lattice of RSJJs. In the limit of large tunneling conductances (g ≫ 1), isolated networks of RSJJs undergo continuous SN phase transitions at low temperatures that are generally independent of the ratio between the Josephson EJ and the Coulomb EC energies56,57,58. In this regime, each junction’s state can be characterized by the value of its normal state resistance, Rn(T), and by its critical current, Ic(T), which generally depend on the ratio between the temperature T of the cryostat and the junction’s SN activation threshold Tc. The latter quantities satisfy in the Ambegaoakar-Baratoff relation59 \({I}_{c}(T){R}_{n}=\frac{\pi }{2e}\Delta (T)\tanh (\Delta (T)/2{k}_{B}T)\), where the energy gap, Δ(T), follows the Bardeen-Cooper-Schrieffer mean-field spectral relation 2Δ(T) ≈ αkBTc with α ≈ 3.53, kB is the Boltzmann constant and e is the elementary charge. The a:InO samples fabricated in the present work, however, have bulk SN thresholds large enough to ensure that junctions rarely undergo a metal-insulator transition. In light of this, we consider a model of RSJJ with only three electronic states: superconducting (SC), intermediate (IM) and normal metal (N), defined according to the Josephson I-V characteristic14. Hence, the junction’s resistance is defined piecewise as:

where Rϵ is the resistance in the SC state (Rϵ = 10−5Ω in simulations) and Vij is the potential drop measured at the junction’s ends. For the critical currents, we used a local generalization of the de Gennes relation60

where \({I}_{ij}^{c}(0)\) is the junction’s critical current at T = 0. We control the degree of disorder in the arrays by considering a quenched normal distribution \({\chi }_{ij}\in {{\mathcal{N}}}(0,\sigma )\) where variables match the junctions’ labels in each array with zero mean and variance σ = 0.1 as a generator for the other system’s observables. Generating a unique χij distribution for each network allows us to model the sample-to-sample disorder level fluctuations observed in the experiment due to the experimental sample fabrication method. In particular, we define \({I}_{ij}^{c}(0)={I}_{0}^{c}(1+{\chi }_{ij})\), \({T}_{ij}^{c}={T}_{c}(1+{\chi }_{ij})\), and \({R}_{ij}^{n}={R}_{n}(1+{\chi }_{ij})\) where the parameters \({I}_{0}^{c}=48\mu A\), Tc = 2K, and Rn = 6kΩ were used in simulations.

Global thermal coupling

The thermal coupling is controlled by the properties of the thermal medium, which is strong enough to decouple the time scales of heat transmission and electronic equilibration, allowing global thermal coupling to characterize the quasistatic state of the system. Therefore, the updated global effective temperature at the t-th overheating cascade is iteratively given by

Here, γ = 4 × 105 WK−1 is the thermal conductance within each network (self-coupling), \({\gamma }^{{\prime} }=4\times 1{0}^{6}\,{{{\rm{WK}}}}^{-1}\) (parameters used in simulations) is the thermal conductance of the coupling medium, \(\mu \, \ne \, {\mu }^{{\prime} }\), with \(\mu,{\mu }^{{\prime} }=A,B\), T is the global heat bath of the system, and ξ(t) is a weak uncorrelated thermal fluctuations satisfying 〈ξ(t)〉 = 0 and \(\langle \xi (t)\xi ({t}^{{\prime} })\rangle=2D{\delta }_{t,{t}^{{\prime} }}\).

Thermally coupled Kirchhoff equations

To characterize the abrupt SN phase transitions reported in the experiments, we have developed a model of thermally coupled RSJJs networks with thermal couplings sustained by the heat dissipation of single junctions. Alike simulations in interdependent networks12, numerical solutions for the mutual order parameter (here, the global sheet resistance, R) can be obtained recursively by making the layers interact through their isolated behaviors adaptively61. In our model of thermally interdependent RSJJ networks, this is achieved by solving the Kirchhoff equations of each array under the adaptive effect set by the ‘two-interaction’ interplay between Eq. (M1), Eq. (M2), and Eq. (M3). We consider, therefore, two layers, A and B, each being a 2D lattice with linear size L, whose left and right boundaries are connected to an external supernode (source) where the bias current is injected and to the ground, respectively. Each junction has a Josephson I − V characteristic with Rij defined as in Eq. (M1), where we assume Rϵ = 10−5Ω for both the arrays and mean normal resistance Rn = 6kΩ. We initiate the algorithm by randomly assigning two vector potentials Vμ with μ = A, B with the same values for all junctions at the zeroth iteration. When starting from the mutual SC state, the junctions’ resistances in both layers are set as \({R}_{ij}^{A}={R}_{ij}^{B}={R}_{\epsilon }\), whilst \({R}_{ij}^{A}={R}_{ij,A}^{n}\) and \({R}_{ij}^{B}={R}_{ij,B}^{n}\) when the layers start from their mutual N phase. The algorithm evolves iteratively as follows:

-

(i)

at the tth stage (t ≥ 1) of the overheating cascade, the effective temperatures, Eq. (M3), are computed using the resistances and the local currents found at the stage (t − 1);

-

(ii)

the critical currents \({I}_{ij}^{c}(T)\) are updated via Eq. (M2), and their resistive state is determined via Eq. (M1) after computing the potential drop Vij,t from the vector Vt;

-

(iii)

the (symmetric) conductance matrices Gμ with μ = A, B are generated via the junctions’ resistances in Eq. (M1) with entries

$${G}_{ij}=\left\{\begin{array}{ll}0,\hfill \quad &\,{{\mbox{if}}} \,\,(i,j) \, \notin \, E\\ -1/{R}_{ij},\hfill \quad &\,{{\mbox{if}}}\,\,(i,j)\in E\\ {\sum }_{k\in \partial i}1/{R}_{ik},\quad &\,{{\mbox{if}}}\,\,i=j\end{array}\right.$$where E is the set of edges in each array and ∂i is the set of nearest neighbors of node i;

-

(iv)

the potential vectors, Vμ,t+1, are updated by solving numerically the Kirchhoff matrix equations

$$\left\{\begin{array}{l}{{{\bf{G}}}}_{t}^{A}\cdot {{{\bf{V}}}}_{t+1}^{A}={{{\bf{I}}}}_{inj}^{A}\quad \\ {{{\bf{G}}}}_{t}^{B}\cdot {{{\bf{V}}}}_{t+1}^{B}={{{\bf{I}}}}_{inj}^{B}\quad \end{array}\right.$$where (⋅) is the matrix product and \({{{\bf{I}}}}_{inj}^{\mu }\) is the vector of total currents injected into each node at every stage, whose elements are always zeroes except for the first entry (the supernode) which equals the driving current \({I}_{b}^{\mu }\) with μ = A, B;

-

(v)

The global sheet resistances of each array are then calculated as \({R}_{t+1}^{\mu }={{{\bf{V}}}}_{t+1}^{\mu }(N)/{I}_{b}^{\mu }\) with μ = A, B.

Steps (i)-(v) are recursively repeated, yielding a sequence of pairs of vector potentials: \(\{({{{\bf{V}}}}_{0}^{A},{{{\bf{V}}}}_{0}^{B}),\ldots,({{{\bf{V}}}}_{t}^{A},{{{\bf{V}}}}_{t}^{B}),\ldots \}\), whose convergence is verified as soon as the mutual error

becomes smaller than a numerical precision ϵmin. In the simulations carried on in the present work, we used ϵmin = 10−5.

Fitting parameters

The scaling in Eq. (2) describes the deviation of the critical point Ic(L) for finite systems from the critical point of an infinite system Ic(∞) as a function of L. The deviation exhibits a power-law scaling with the critical exponent ν, which can be estimated both experimentally and theoretically from this scaling. Since Ic(∞) is not known in theory and can not be measured by experiments or simulations, we used it as a fitting parameter. The value of Ic(∞) is determined by minimizing the error for a linear line on a log-log scale of Ic(∞) − Ic(L) as a function of L and the slope of the best-fitted line estimates the exponent ν.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The Experimental measurement data generated in this study are provided in the Supplementary Information/Source Data file.

Code availability

Source codes can be freely accessed at the GitHub repository: https://github.com/BnayaGross/Microscopic-mechanism-of-interdependent-SC-networks.

References

Sethna, J. Statistical mechanics: entropy, order parameters, and complexity, vol. 14 (Oxford University Press, 2006).

Stanley, H. E. Phase transitions and critical phenomena, vol. 7 (Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1971).

Domb, C. Phase transitions and critical phenomena (Elsevier, 2000).

Fisher, M. E. Phase transitions and critical phenomena. In Contemporary Physics: Trieste Symposium 1968. Vol. I. Proceedings of the International Symposium on Contemporary Physics (1969).

D’Souza, R. M., Gómez-Gardenes, J., Nagler, J. & Arenas, A. Explosive phenomena in complex networks. Adv. Phys. 68, 123–223 (2019).

Lee, D., Choi, W., Kertész, J. & Kahng, B. Universal mechanism for hybrid percolation transitions. Sci. Rep. 7 (2017).

Mukamel, D. Mixed-order phase transitions. In 50 Years of the Renormalization Group: Dedicated to the Memory of Michael E Fisher, 89–101 (World Scientific, 2024).

Boccaletti, S. et al. Explosive transitions in complex networks’ structure and dynamics: Percolation and synchronization. Phys. Rep. 660, 1–94 (2016).

Gross, B., Bonamassa, I. & Havlin, S. Fractal fluctuations at mixed-order transitions in interdependent networks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 129, 268301 (2022).

Alert, R., Tierno, P. & Casademunt, J. Mixed-order phase transition in a colloidal crystal. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 114, 12906–12909 (2017).

Bonamassa, I. et al. Interdependent superconducting networks. Nat. Phys. 19, 1163–1170 (2023).

Buldyrev, S. V., Parshani, R., Paul, G., Stanley, H. E. & Havlin, S. Catastrophic cascade of failures in interdependent networks. Nature 464, 1025–1028 (2010).

Bonamassa, I., Gross, B., Kertész, J. & Havlin, S. Hybrid universality classes of systemic cascades. Nat. Commun. 16, 1415 (2025).

Josephson, B. D. Possible new effects in superconductive tunnelling. Phys. Lett. 1, 251–253 (1962).

Strongin, M., Thompson, R., Kammerer, O. & Crow, J. Destruction of superconductivity in disordered near-monolayer films. Phys. Rev. B 1, 1078 (1970).

Dynes, R., White, A., Graybeal, J. & Garno, J. Breakdown of eliashberg theory for two-dimensional superconductivity in the presence of disorder. Phys. Rev. Lett. 57, 2195 (1986).

Finkelstein, A. Pis’ ma zhetf 45, 37 (1987). JETP Lett. 45, 46 (1987).

Haviland, D., Liu, Y. & Goldman, A. M. Onset of superconductivity in the two-dimensional limit. Phys. Rev. Lett. 62, 2180 (1989).

Goldman, A. M. & Markovic, N. Superconductor-insulator transitions in the two-dimensional limit. Phys. Today 51, 39–44 (1998).

Sacépé, B. et al. Localization of preformed cooper pairs in disordered superconductors. Nat. Phys. 7, 239–244 (2011).

Sherman, D., Kopnov, G., Shahar, D. & Frydman, A. Measurement of a superconducting energy gap in a homogeneously amorphous insulator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 177006 (2012).

Sherman, D. et al. The higgs mode in disordered superconductors close to a quantum phase transition. Nat. Phys. 11, 188–192 (2015).

Poran, S. et al. Quantum criticality at the superconductor-insulator transition revealed by specific heat measurements. Nat. Commun. 8, 1–8 (2017).

Roy, A., Shimshoni, E. & Frydman, A. Quantum criticality at the superconductor-insulator transition probed by the Nernst effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 047003 (2018).

Parshani, R., Buldyrev, S. V. & Havlin, S. Interdependent networks: Reducing the coupling strength leads to a change from a first to second order percolation transition. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 048701 (2010).

Gross, B., Bonamassa, I. & Havlin, S. Microscopic intervention yields abrupt transition in interdependent ferromagnetic networks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 227401 (2024).

Stanley, H. Introduction to Phase Transitions and Critical Phenomena. International series of monographs on physics (Oxford University Press, 1971).

Stauffer, D. & Aharony, A. Introduction to Percolation Theory (Taylor & Francis, 1994). http://books.google.co.il/books?id=v66plleij5QC

Bunde, A. & Havlin, S. Fractals and disordered systems (Springer-Verlag New York, Inc., 1991).

Baxter, G., Dorogovtsev, S., Lee, K.-E., Mendes, J. & Goltsev, A. Critical dynamics of the k-core pruning process. Phys. Rev. X 5, 031017 (2015).

Hastings, A. et al. Transient phenomena in ecology. Science 361, eaat6412 (2018).

Zhou, D. et al. Simultaneous first- and second-order percolation transitions in interdependent networks. Phys. Rev. E 90, 012803 (2014).

Harris, T. E. et al. The theory of branching processes, vol. 6 (Springer Berlin, 1963).

Harris, T. E. Branching processes. The Annals of Mathematical Statistics 474–494 (1948).

Athreya, K. B., Ney, P. E. & Ney, P. Branching processes (Courier Corporation, 2004).

Allen, L. J. Branching processes. Encyclopaedia of Theoretical Ecology 130 (2012).

Haccou, P., Jagers, P. & Vatutin, V. A. Branching processes: variation, growth, and extinction of populations. 5 (Cambridge University Press, 2005).

Nishi, R. et al. Reply trees in Twitter: data analysis and branching process models. Soc. Netw. Anal. Min. 6, 1–13 (2016).

Atanasov, D., Stoimenova, V. & Yanev, N. M. Statistical modelling of COVID-19 pandemic development applying branching processes. J. Appl. Stat. 50, 2330–2342 (2023).

BARTOSZYŃSKI, R. Branching processes and the theory of epidemics. In Proceedings of the Berkeley Symposium on Mathematical Statistics and Probability, vol. 4, 259 (University of California Press, 1967).

Daley, D. J. & Gani, J. M. Epidemic modelling: an introduction. 15 (Cambridge University Press, 1999).

Hinrichsen, H. Non-equilibrium critical phenomena and phase transitions into absorbing states. Adv. Phys. 49, 815–958 (2000).

Zhang, Y.-J., Wu, Z.-X., Holme, P. & Yang, K.-C. Advantage of being multicomponent and spatial: Multipartite viruses colonize structured populations with lower thresholds. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 138101 (2019).

Radicchi, F. & Bianconi, G. Epidemic plateau in critical susceptible-infected-removed dynamics with nontrivial initial conditions. Phys. Rev. E 102, 052309 (2020).

Binder, K. Theory of first-order phase transitions. Rep. Prog. Phys. 50, 783 (1987).

Binder, K. Time-dependent Ginzburg-Landau theory of nonequilibrium relaxation. Phys. Rev. B 8, 3423 (1973).

Unger, C. & Klein, W. Nucleation theory near the classical spinodal. Phys. Rev. B 29, 2698 (1984).

Zapperi, S., Vespignani, A. & Stanley, H. E. Plasticity and avalanche behaviour in microfracturing phenomena. Nature 388, 658–660 (1997).

Zapperi, S., Lauritsen, K. B. & Stanley, H. E. Self-organized branching processes: mean-field theory for avalanches. Phys. Rev. Lett. 75, 4071 (1995).

Alava, M. J., Nukala, P. K. & Zapperi, S. Statistical models of fracture. Adv. Phys. 55, 349–476 (2006).

Pradhan, S., Hansen, A. & Chakrabarti, B. K. Failure processes in elastic fiber bundles. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 499–555 (2010).

Rundle, J. B., Turcotte, D. L., Shcherbakov, R., Klein, W. & Sammis, C. Statistical physics approach to understanding the multiscale dynamics of earthquake fault systems. Rev. Geophys. 41 (2003).

Zimmers, A. et al. Role of thermal heating on the voltage induced insulator-metal transition in VO2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 056601 (2013).

Radicchi, F. Percolation in real interdependent networks. Nat. Phys. 11, 597–602 (2015).

Lee, D., Choi, S., Stippinger, M., Kertész, J. & Kahng, B. Hybrid phase transition into an absorbing state: Percolation and avalanches. Phys. Rev. E 93, 042109 (2016).

Orr, B., Jaeger, H., Goldman, A. & Kuper, C. Global phase coherence in two-dimensional granular superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 56, 378 (1986).

Chakravarty, S., Ingold, G.-L., Kivelson, S. & Luther, A. Onset of global phase coherence in Josephson-junction arrays: a dissipative phase transition. Phys. Rev. Lett. 56, 2303 (1986).

Chakravarty, S., Ingold, G.-L., Kivelson, S. & Zimanyi, G. Quantum statistical mechanics of an array of resistively shunted Josephson junctions. Phys. Rev. B 37, 3283 (1988).

Ambegaokar, V. & Baratoff, A. Tunneling between superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 10, 486 (1963).

De Gennes, P.-G. On a relation between percolation theory and the elasticity of gels. J. de. Phys. Lett. 37, 1–2 (1976).

Ponta, L., Carbone, A., Gilli, M. & Mazzetti, P. Resistive transition in granular disordered high t c superconductors: A numerical study. Phys. Rev. B—Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 79, 134513 (2009).

Acknowledgements

S.H. acknowledges the support of the Israel Science Foundation (Grant No. 189/19), the Binational Israel-China Science Foundation Grant No. 3132/19, the EU H2020 project RISE (Project No. 821115), the EU H2020 DIT4TRAM, EU H2020 project OMINO (Grant No. 101086321), the Israel VATAT program on Networks for financial support. B.G. acknowledges the support of the Fulbright Postdoctoral Fellowship Program. I.V. Y.S. and A.F. acknowledge support from the Israel Science Foundation (ISF) Grants No. 3053/23 and No. 1499/21. We thank N. Shnerb for helpful discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

I.V. and Y.S. prepared the samples and performed the experiments. B.G., I.B., and N.Y. performed the theoretical calculations and data analysis. AF and SH initiated and supervised the project. B.G., I.B., A.F., and S.H. designed the research. B.G., A.F., and S.H. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

There are no competing interests to declare.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Juan Rocha, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gross, B., Volotsenko, I., Sallem, Y. et al. The random cascading origin of abrupt transitions in interdependent systems. Nat Commun 16, 5869 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-61127-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-61127-z